Abstract

Understanding mental health issues faced by young homeless persons is instrumental to the development of successful targeted interventions. No systematic review of recent published literature on psychopathology in this group has been completed.

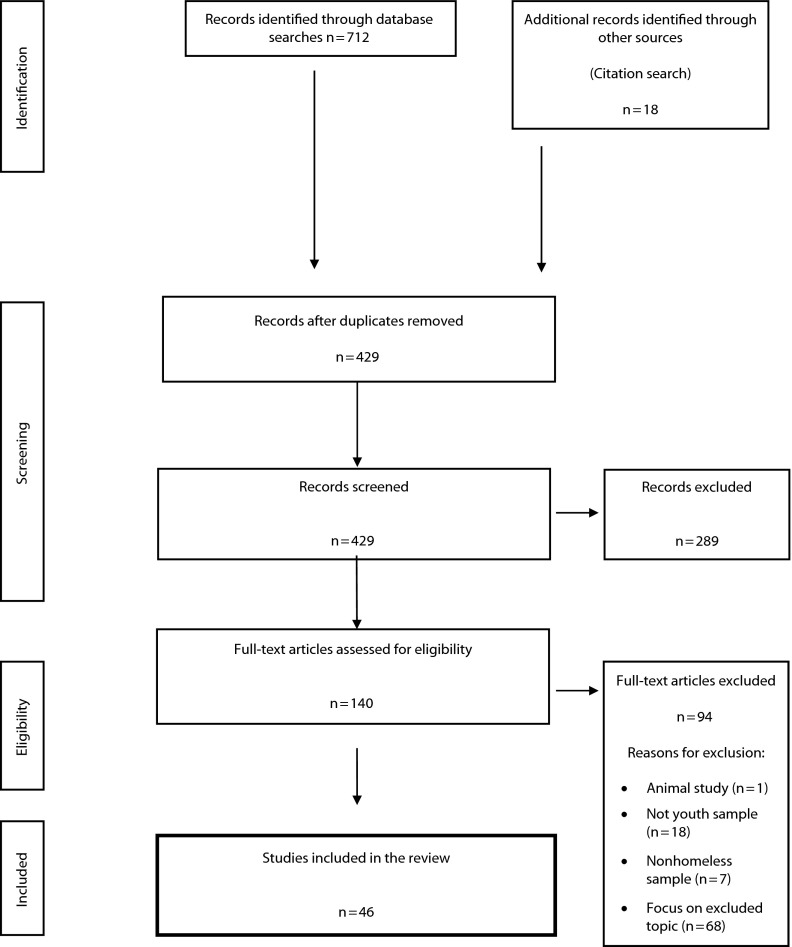

We conducted a systematic review of published research examining the prevalence of psychiatric problems among young homeless people. We examined the temporal relationship between homelessness and psychopathology. We collated 46 articles according to the PRISMA Statement.

All studies that used a full psychiatric assessment consistently reported a prevalence of any psychiatric disorder from 48% to 98%. Although there was a lack of longitudinal studies of the temporal relationship between psychiatric disorders and homelessness, findings suggested a reciprocal link. Supporting young people at risk for homelessness could reduce homelessness incidence and improve mental health.

PREVIOUS ESTIMATES INDICATE that 1% of Americans have experienced homelessness in any single year and as many as 1.35 million of those people are young people or children.1 Exploring mental health difficulties that are found to be highly prevalent among young people with experiences of homelessness is central to understanding the relationship between psychopathology and youth homelessness. Youth homelessness and the characteristics associated with these phenomena have not been well documented. This is partly because of the transient or sometimes hidden nature of homelessness alongside the often chaotic lifestyles of young people living in temporary accommodation or on the streets. Understanding the role of psychopathology in this area may lead to the development of interventions that could reduce the incidence of debilitating psychiatric disorders. It is important that interventions tailored to the needs of young people could also have an impact on the occurrence of homelessness and improve housing outcomes for those who do become homeless.

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among homeless persons has been shown to be high.2,3 However, research has not always distinguished between psychopathology among young people experiencing homelessness and that of older people. This is important because the causes of homelessness and the type and duration of support required by young people in this situation differ from that among adults. For example, family relationship breakdown, a reliance on insecure forms of accommodation, leaving care, and living with a step-parent have each been shown to be related to youth homelessness.4 By contrast, some of the strongest risk factors for adult homelessness are eviction, loss of employment, and breakdown of relationship with a partner.5 We performed a review to address the gap in the literature and distinguish the psychopathology found among young people with experiences of homelessness. This will aid the development of services for young people, enabling more focused targeting of resources to combat issues particular to young homeless people.

The concept of “youth” has been defined by the United Nations as a person aged between 15 and 24 years.6 “Youth” is a period often temporally linked to the age at which a person ceases to be the responsibility of his or her legal guardians, becoming more psychologically and economically autonomous. For some, this period is accompanied by experiences of homelessness.7,8 Periods of homelessness at a young age have been linked to homelessness later in life.9 Mental health difficulties may be central to explaining this link. Mental health can have an impact on the problem-solving skills necessary for coping when homeless, with implications for the ability to move out of homelessness successfully.10

Only a very limited number of systematic reviews examining psychopathology among young homeless people have been completed. These have focused on research from 1 country,11 did not specifically focus on mental health,12 have examined the homeless population in general rather than young people in particular,2 or have been completed more than 10 years ago.13

Furthermore, researchers studying the etiology of youth homelessness have published their findings across a range of disciplines including public health, psychology, psychiatry, social policy, and human geography. Indeed, because research has been published in a range of journals it is difficult for service providers to gain a clear impression of the extent of the association between experiences of homelessness and psychopathology. This systematic review collates findings providing an overview of recent international research focused on psychiatric disorders prevalent among this group. A second aim was to consider evidence in relation to the direction of effects linking experiences of homelessness and psychopathology. Mental health issues may precede homelessness or, alternatively, symptoms may be exacerbated or elicited by homelessness.

METHODS

We designed and reported this systematic review according to the PRISMA statement, an internationally recognized 27-item method ensuring the highest standard in systematic reviewing.14 We undertook an electronic search of articles published between 2000 and 2012 with Web of Science, PubMed, and PsycINFO, using the keywords shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1—

Specification of Search Parameters for Systematic Review of Published Research on Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Among Young Homeless People

| Operator | Definition |

| 1. Keywords | homeless OR roofless OR fixed abode OR bed and breakfast OR hostel OR shelter OR street dwell OR hotel OR sofa surfing OR tramp OR housing benefit OR vagrant OR refuge OR couch surfing OR street |

| 2. Keywords | young people OR youth OR adolescent OR young OR teenage OR young adults OR young men OR young women OR young person |

| 3. Keywords | mental* OR psych* OR depress* OR schizophrenia OR bipolar OR manic OR hypomanic OR mania OR anorexia OR bulimia OR anxiety OR attention deficit hyperactivity disorder OR posttraumatic stress disorder OR trauma OR stress OR psychotic OR anger OR mood OR emotion OR phobia OR panic OR internalizing OR externalizing OR agoraphobia OR suicide OR obsessive OR compulsive OR melancholic OR dysthymia OR disorder OR dysfunction OR behavior OR self-harm OR hyperkinetic OR oppositional defiant |

| 4. Boolean operator | 1 AND 2 AND 3 |

| 5. Limits language | English language |

| 6. Limits date | Years 2000–2012 |

| 7. Limits kind of studies | classical article OR comparative study OR evaluation studies OR journal article OR review |

| 8. Limits subjects of studies | (male OR female) AND (humans) |

| 9. Boolean operator | 4 AND 5 AND 6 AND 7 AND 8 |

| 10. Selection | Removal of duplicates and manual exclusion of articles not conforming to desired criteria |

We derived the search terms via consultation with a psychiatrist, psychologist, and youth homelessness professional. We also used the search criteria of previous relevant review articles. We carried out a citation search and identified additional articles from citations yielded by the electronic search. We postulated exclusion criteria before the search. We excluded articles if titles or abstracts indicated that studies focused on animal research; a study sample exclusively outside the 16- to 25-year age range; exclusively physical health, substance misuse, sexual health, social relationships, sexuality, criminality, or trauma; or nonhomeless or at-risk-for-homelessness samples.

For the purposes of this review, we defined homelessness as being without suitable or permanent accommodation. This included street-dwelling homeless samples, those in shelter accommodation, those in temporary accommodation such as bed and breakfast or supported accommodation, those staying with friends, or those staying in unsuitable accommodation.

Drug and alcohol misuse and dependence in the context of youth homelessness have been extensively researched. For that reason we did not include these behaviors in the search criteria. We refer the reader to relevant research from the United States,15 United Kingdom,16 and Australia.17 However, where research in this review reports on substance and alcohol misuse alongside other psychiatric conditions, we have included it in the analysis.

Two independent researchers screened titles and abstracts of the articles gathered during the search against the exclusion criteria. The first author read the full articles in detail and excluded them if they focused on any excluded topic (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Flow diagram of study selection for systematic review of published research on prevalence of psychiatric disorders among young homeless people.

We read the final articles in full and extracted numeric data detailing prevalence of psychiatric disorder. We collated information on the country where research was conducted, size of the sample, sampling strategy, age range of participants, study design, measures used, diagnostic criteria used, and prevalence information. In addition, we assessed each article for information pertaining to the direction of effects between psychopathology and homelessness. We also recorded where articles contained information on the relationship between mental health and homelessness.

RESULTS

We included 46 articles in the review. The majority of the publications examined homelessness in the United States (n = 34) followed by Canada (n = 8), Australia (n = 6), United Kingdom (n = 2), Switzerland (n = 1), and Sweden (n = 1). These figures include some cross-cultural studies of more than 1 location. Most of the studies used a cross-sectional research design (n = 29), a few were longitudinal (n = 11), and the remainder consisted of literature reviews (n = 4), population studies (n = 1), and retrospective studies (n = 1). Full psychiatric interviews using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition18 or Fourth Edition19 (DSM-III or DSM-IV) or International Classification of Diseases 1020 (ICD-10) criteria were undertaken in 10 studies. Other studies used subscales that were based on DSM or ICD criteria. The remaining studies that involved interviewing participants used scales such as the Brief Symptom Inventory,21 which are not based on diagnostic criteria.

Definition of Homelessness

Homelessness was defined in a number of different ways. Many studies involved interviews with young people who had resided in homeless shelters (n = 17). The duration of homelessness varied considerably across studies, from a few hours since arriving at a shelter or hostel22 to more than 6 months.23 Two studies focused solely on street homelessness and others took a broader definition including young people living in temporary accommodation (supported housing or staying with friends), street homeless, or in a shelter (n = 11). One term frequently referred to in the literature was “runaways” (n = 8). This term was often not clearly defined and was used interchangeably to mean a young person who is homeless or a young person who has run away from home overnight. Our interpretation of the findings from studies using this term in the context of this review was cautious because of this variability; however, they have been included.

We examined the studies according to the aims of the review and have divided them into tables according to our 2 aims, but there is some duplication where articles addressed both topics.

Prevalence of Psychopathology in Homeless Young People

Thirty-eight studies examined the prevalence of psychopathology among young homeless people (Table 2). Ten studies (26.3%) that used a full psychiatric diagnostic interview and reported the total prevalence of psychiatric conditions indicated that psychiatric disorder was present in more than 48.4% of homeless young people.11,26,27,29,41,42 The percentage of DSM and ICD disorders identified by the research reviewed ranged from 48.4%11 to 98%.41 Most studies used DSM criteria but some used ICD. Table 3 presents the findings of 3 population studies of psychiatric disorders among young people in the general population. The prevalences are considerably lower than those found among the young homeless population.

TABLE 2—

Prevalence of Psychopathology in Systematic Review of Published Research on Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Among Young Homeless People, 2000–2012

| Author | Country | Sample Size | Sampling Strategy | Age Range, Years | Design | Measures | Diagnostic Criteria | Prevalence of Mental Health Results |

| Bearsley-Smith et al.24 | Australia | Homeless: 137;At risk for homelessness: 766;Not at risk for homelessness: 4844 | Shelter, school support, health services | Nonhomeless: 14–17;Homeless: 13–19 | Cross-sectional | Self-report questionnaire measure;SMFQ | Depression assessed with DSM-III18 criteria | Depressive symptoms: 16% |

| Beijer and Andreasson25 | Sweden | 1704 | Homeless persons and a housed comparison group | 20–92a | Cross-sectional | Health service information | ICD-1020 | Psychiatric conditions not reported by age group |

| Bender et al.26 | US | 146 | Street dwelling, shelter, drop-in center | 18–24 | Cross-sectional | Full psychiatric assessment: the Mini International Neuropsychiatry Interview | DSM-IV19 | Depression: 28.1%;Hypomanic: 30.1%;Manic: 21.2%;Alcohol addiction: 28.1%;Drug addiction: 36.3%;PTSD: 24% |

| Cauce et al.27 | US | 364 | Street dwelling, shelter, temporary accommodation | 13–21 | Cross-sectional | Full psychiatric assessment: the DISC-R. | DSM-III-R | CD/ODD: 53%;ADD: 32%;MDD: 21%;Mania or hypomania: 21%;PTSD: 12%;Schizophrenia: 10% |

| Coward Bucher23 | US | 422 | Street dwelling without current stable residence who have not lived with parent or guardian > 30 d in past 6 mo | < 21 | Cross-sectional | Not reported | Not reported | NA |

| Craig and Hodson28 | UK | 161 | Shelter | 16–21 | Longitudinal | Full psychiatric assessment: CIDI | DSM-III-R | (1 mo prevalence) substance abuse only: 11%; |

| Substance dependency only: 19%; | ||||||||

| Mental illness only: 13%; | ||||||||

| Mental illness and substance abuse: 1%; | ||||||||

| Mental illness and substance dependency: 11% | ||||||||

| Crawford et al.29 | US | 222 | Street dwelling, shelter, drop-in center young homeless women | 16–19 | Longitudinal | Full psychiatric assessment: CIDI and DISC-R | DSM-IV | MDD: 32.5%;CD: 65.1%;PTSD: 51.8%;Drug abuse: 34.9%;Alcohol abuse: 20.5%;Alcohol dependence: 22.9% |

| Folsom and Jeste2 | US | NA | Systematic review, 33 articles | NA | Systematic review | NA | NA | Not reported |

| Fournier et al.30 | US | 3264 | School students | 14–18 | Cross-sectional | Disordered weight-control behaviors were assessed | NA | Purging: 11.7%;Fasting: 24.9% |

| Frencher et al.31 | US | Homeless: 326 073;Low socioeconomic status: 1 202 622 | Hospitalized homeless and low socioeconomic status persons | 0.1–≥ 65a | Cross-sectional population study | Medical records examined | Not reported | NA |

| Gwadz et al.32 | US | 85 | Street dwelling, shelter, sofa surfing, at risk for homelessness (inadequately housed) | 16–23 | Cross-sectional | Interview Post-Traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale | DSM-IV Post Traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale | PTSD: 8.3% |

| Hadland et al.33 | Canada | 495 | Street dwelling | 14–26 | Cross-sectional | Assessment of suicide attempts and risk of suicide | NA | 9.3% suicide attempt past 6 mo;36.8% lifetime suicidal ideation |

| Hughes et al.7 | Canada | 60 | Shelter | 16–24 | Cross-sectional | Youth self-report measures (Achenbach and Edelbrock34) and adult self-report measures (Achenbach and Rescorla35) ) | NA | In clinical range for internalizing symptom: 22%;In clinical range for externalizing symptoms: 40% |

| Kamieniecki11 | Australia | NA | NA | 12–25 | Comparative review | NA | NA | Studies using full psychiatric assessments found > 48.4% prevalence of psychiatric conditions |

| Kidd36 | Canada and US | 208 | Street dwelling, temporary accommodation | 14–24 | Cross-sectional | Structured interviews | NA | Suicide attempt lifetime: 46% |

| Kidd and Carroll37 | Canada and US | 208 | Street dwelling, temporary accommodation | 14–24 | Cross-sectional | Structured interviews | NA | Same sample as Kidd36 |

| Kirst et al.38,39 | Canada | 150 | Street dwelling, shelter | Unknown | Longitudinal | Full psychiatric assessment | DSM-IV | Comorbid substance use and mental health problems: 25%; |

| Suicidal ideation: 27% | ||||||||

| Kulik et al.12 | Canada | NA | NA | < 25 | Literature review | NA | NA | Not reported |

| McManus and Thompson40 | US | NA | NA | NA | Literature review | NA | NA | Trauma symptom: 18% |

| Merscham et al.41 | US | 182 | Shelter | 16–25 | Retrospective study | Archival assessment of past psychiatric diagnosis | DSM-IV | Psychosis: 21.4%;Bipolar: 26.9%;Depression: 20.3%;PTSD: 8.2%;Polysubstance dependence: 6%;ADHD: 4.4%;Other diagnosis: 11% |

| Milburn et al.42 | US and Australia | American n = 617;Australian n = 673 | Street dwelling, shelter, drop-in center, support services (representative sample) | 12–20 | Cross-sectional cross-cultural | BSI | BSI based on Symptom Checklist 90 | Newly homeless:Recent suicide attempt: 11.5%;Lifetime suicide attempt: 32.1%;Overall mental health issues: 30.9%Experienced homeless:Recent suicide attempt: 8.8%;Lifetime suicide attempt: 40.7%;Overall mental health issues: 32.9% |

| Rohde et al.43 | US | 523 | Street dwelling, shelter | Adolescents < 21 | Longitudinal | Diagnostic interview used to identify major depression and related conditions | DSM-IV | MDD: 12.2%;Dysthymia: 6.5%;Depression: 17.6%;Suicide attempt (lifetime): 38% |

| Rosenthal et al.44 | US and Australia | 358 | Street dwelling, shelter | 12–20 | Longitudinal cross-cultural | Interview measure of substance misuse and BSI | DSM-IV to assess drug dependency. | US:Baseline drug dependence: 11%;Comorbidity: 5% |

| Australia: | ||||||||

| Baseline drug dependence: 20%; | ||||||||

| Comorbidity: 6% | ||||||||

| Ryan et al.45 | US | 329 | Homeless drop-in center | 13–20 | Cross-sectional | Full psychiatric assessment: Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (CDISC) | DSM-III-R | Depression or dysthymia:No abuse group: 14.8%;Physical abuse group: 10.9%; Sexual abuse group: 14.3%; Both types of abuse group: 35.2% |

| History of suicide attempt (lifetime): | ||||||||

| No abuse group: 22.7%; Physical abuse group: 41.3%; Sexual abuse group: 53.6%; | ||||||||

| Both types of abuse group: 68.2% | ||||||||

| Shelton et al.46 | US | 14 888 | High-school students | 11–18 at baseline; | Longitudinal population-based | Structured interview: no diagnostic measure | NA | Self-report depression: 26.4% |

| 18–28 at follow-up | ||||||||

| Slesnick and Prestopnik47 | US | 226 | Shelter (in treatment of substance abuse) | 13–17 | Cross-sectional | Full psychiatric assessment (CDISC) | DSM-IV | Substance use disorders: 40%;Dual substance and mental health diagnosis: 34%; |

| Substance use and 2 or more mental health diagnoses: 26%; | ||||||||

| CD or ODD: 36%; | ||||||||

| Anxiety disorders: 32%; | ||||||||

| Affective disorders: 20% | ||||||||

| Stewart et al.48 | US | 374 | Street dwelling, shelter, drop-in centers | 13–21 | Cross-sectional | Diagnostic measure of PTSD | DSM-IV | PTSD: 14% |

| Taylor et al.49 | UK | 150 | Shelter | 16–25 | Cross-sectional | Interview measured characteristics and types of behavior: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (Wing et al.50) | NA | Depressed mood: 66%;Emotional symptoms associated with trauma: 30%;Alcohol or drug problems: 30%;Panic attacks or anxiety: 23%; |

| Suicidal thoughts or behaviors: 20%; | ||||||||

| Self-harm: 20%; | ||||||||

| Problems with eating: 12%; | ||||||||

| Psychotic symptoms: 14%; | ||||||||

| Personality disorder: 8%; | ||||||||

| Obsessive compulsive: 2%; | ||||||||

| Social phobia: 1% | ||||||||

| Tompsett et al.51 | US | 363 adolescent homeless;157 younger homeless adults | Shelter | Adolescents 13–17;Younger adults 18–34a | Cross-sectional comparative | BSI | NA | Alcohol abuse:Adolescents: 10.9%;Young adults: 47.4% |

| Tyler et al.52 | US | 199 | Street dwelling, shelter, temporary accommodation | 19–26 | Cross-sectional | Structured interview: Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (Gratz, 200153); | Not stated | Repeated self-harm: 19%;PTSD: 61% |

| PTSD Impact of Event Scale (Horowitz et al.54) | ||||||||

| Tyler et al.55 | US | 428 | Street dwelling, shelter (homeless and runaway youths) | 16–19 | Cross-sectional | Diagnostic assessment (CIDI) | DSM-III-R | Self-harm: 69%Other prevalence not reported |

| Votta and Farrell56 | Canada | 174 | Shelter (homeless women) and a housed group | 16–19 | Cross-sectional | BDI | DSM-IV | Suicidal ideation: 31% |

| Votta and Manion57 | Canada | 170 | Shelter (homeless young men) and housed group | 16–19 | Cross-sectional | Youth self-report; Behavioral problems (externalizing and internalizing) based on CBCL;BDI | DSM-III criteria for substance abuse disorders;CBCL uses DSM-orientated scales | Suicide attempt (lifetime): 21%;Suicidal ideation: 43% |

| Whitbeck et al.58 | US | 366 | Street dwelling, shelter (homeless and runaway youths) | 16–19 | Cross-sectional comparative | Diagnostic assessment of conduct disorder, depression, PTSD, alcohol abuse and drug abuse, and suicidal attempts and ideation (CIDI) | DSM-III-R | Homosexual:MDD: 41.3%PTSD: 47.6%;Suicide ideation: 73%;Suicide attempt: 57.1%;CD: 69.8%;Alcohol abuse: 52.4%; |

| Drug abuse: 47.6% | ||||||||

| Heterosexual: | ||||||||

| MDD: 28.5%; | ||||||||

| PTSD: 33.4%; | ||||||||

| Suicide ideation: 53.2%; | ||||||||

| Suicide attempt: 33.7%; | ||||||||

| CD: 76.7%; | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse: 42.2%; | ||||||||

| Drug abuse: 39.2% | ||||||||

| Whitbeck et al.59 | US | 602 | Street dwelling, shelter, drop-in center (homeless and runaway youths) | 12–22 | Cross-sectional | Depression symptom checklist (CES-D60). | DSM-IV | Depression: 23% |

| Whitbeck et al.61 | US | 428 | Street dwelling, shelter (homeless and runaway youths) | 16–19 | Cross-sectional | Diagnostic measure of PTSD (CIDI) | DSM-III-R | PTSD (lifetime): 35.5%;PTSD (12 months): 16.1%;Comorbidity: |

| PTSD and MDE: 48%; | ||||||||

| PTSD and CD: 80.9%; | ||||||||

| PTSD and alcohol abuse: 51.3%; | ||||||||

| PTSD and drug abuse: 48.7% | ||||||||

| Whitbeck et al.62 | US | 428 | Street dwelling, shelter (homeless and runaway youths) | 16–19 | Cross-sectional | Diagnostic assessment of conduct disorder, depression, PTSD, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse (CIDI) | DSM-III-R | Lifetime:MDD: 30.3%;CD: 75.7%;PTSD: 35.5%;Alcohol abuse: 43.7%; |

| Drug abuse: 40.4% | ||||||||

| 12-month prevalence: | ||||||||

| MDD: 23.4%; | ||||||||

| CD: NA; | ||||||||

| PTSD: 16.8%; | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse: 32.7%; | ||||||||

| Drug abuse: 25.7%;Comorbidity:≥ 2 disorders: 67.3% | ||||||||

| Yoder et al.63 | US | 428 | Street dwelling, shelter, temporary accommodation (homeless and runaway youths) | 16–19 | Cross-sectional | Diagnostic interview conduct disorder (DISC-R), depression, PTSD, alcohol abuse, drug abuse (CIDI) | DSM-III-R | MDE: 30.4%;PTSD: 36.0%;CD: 75.7%;Alcohol abuse: 43.7%;Drug abuse: 40.4% |

Note. ADD = attention-deficit disorder; ADHD = attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CD = conduct disorder; CIDI = Composite Diagnostic Interview; DISC-R = Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Revised; MDD = major depressive disorder; MDE = major depressive episode; NA = not applicable; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SMFQ = short mood and feelings questionnaire.

Where sample contained participants outside the age category “youth,” only the results pertaining to the youth element of the sample are presented.

TABLE 3—

Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorder Among General Population in Systematic Review of Published Research on Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Among Young Homeless People, 2000–2012

| Disorder | Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorder in Past Week, Housed 16- to 24-Year-Old People in United Kingdom (n = 560): NHS Information Centre64 | Lifetime Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorder, 18- to 29-Year-Old People in United States (n = 2338): Kessler et al.65 | 3-Month Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorder, 16-Year-Old People in United States (n = 6674): Costello et al.66 |

| Any diagnosis | 32.3% | 52.4% | 12.7% |

| Anxiety | Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder: 10.2%; | Agoraphobia without panic: 1.1%; | 1.6% |

| Generalized anxiety disorder: 3.6% | Generalized anxiety disorder: 4.1% | ||

| Mood disorders | Depressive episode: 2.2% | Major depressive disorder: 15.4%; | Any depression: 3.1% |

| Dysthymia: 1.7%; | |||

| Bipolar I–II disorders: 5.9% | |||

| All phobias | 1.5% | Specific phobia: 13.3%; | … |

| Social phobia: 13.6% | |||

| Panic disorder | 1.1% | 4.4% | … |

| OCD | 2.3% | 12.0% | … |

| PTSD | 4.7% | 6.3% | … |

| Impulse control disorders | … | Conduct disorder: 10.9%; | Conduct disorder: 1.6%; |

| Intermittent explosive disorder: 7.4%; | ODD: 22% | ||

| ODD: 9.5% | |||

| Suicidal thoughts | Past y: 7% | … | … |

| Suicide attempts | Past y: 1.7%; | … | … |

| Lifetime: 6.2% | |||

| Self-harm | Lifetime: 12.4% | … | … |

| Psychosis | 0.2% | … | |

| ADHD | 13.7% (diagnosis did not require childhood ADHD) | 7.8% | 0.3% |

| Eating disorder | 13.1% (when BMI is not taken into account) | … | … |

| Alcohol dependence | Past 6 mo: 11.2% | 6.3% | All substance use disorders: 7.6% |

| Alcohol abuse | Past y: 6.8% (harmful drinking) | 14.3% | |

| Drug dependence | Past y: 10.2% | 3.9% | |

| Drug abuse | … | 10.9% | |

| Comorbidity | 12.4% | ≥ 2 disorders: 33.9%; | … |

| ≥ 3 disorders: 22.3% |

Note. ADHD = attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BMI = body mass index; NHS = National Health Service; OCD = obsessive–compulsive disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Most studies did not consider comorbidity. However, in a review of Australian literature, Kamieniecki11 found levels of comorbidity among young homeless people to be at least twice as high as those for housed counterparts. A handful of other studies have also found very high rates of comorbidity—Slesnick and Prestopnik,47 60%; Whitbeck et al.,58 67.3%; and Thompson et al.,67 40%—of young people with substance abuse disorders had comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The most common comorbidities found by these studies were those involving substance misuse disorders and another psychiatric disorder (particularly PTSD). However, Yoder et al.63 found that clinically high levels of externalizing disorders and internalizing disorders were associated with suicidal ideation indicating links between nonsubstance psychiatric disorders. Research assessing comorbidity within this population is sparse; studies that did examine the phenomenon appeared to reveal rates that were high compared with those in the general population.

Eleven studies did not use full diagnostic interviews to assess psychiatric disorder. These studies provide an indication of the prevalence of mental health issues among young homeless people, but the full picture of psychiatric conditions was not revealed. For example, Hughes et al.7 found clinically high levels of internalizing symptoms (withdrawal, depression or anxiety, and somatic complaints: 20%) and externalizing problems (delinquent and aggressive behaviors: 40%). The co-occurrence of internalizing symptoms and externalizing behavior was found among 48% of shelter-based youths. Fournier et al.30 examined behaviors related to eating disorders and found that youths with experience of homelessness were more likely to have disordered weight-control behaviors compared with housed counterparts. Coward Bucher23 showed evidence of several needs-based groups, including minimal needs (18.5%), focus on addiction (21%), focus on behavioral issues (21.5%), and finally a group with complex comprehensive needs (including addiction, behavioral issues, experiences of abuse, and criminality: 38%). These studies indicated high levels of a range of mental health difficulties.

One study, however, reported low levels of mental health problems in young homeless persons. Rosenthal et al.44 reported a rate of 17% at baseline and 8% of any conditions at follow-up, which is considerably lower than that in the other studies reviewed here. The authors suggested that their finding may be explained by the fact that the young people in their study were newly homeless, and had not yet developed many difficulties. There may have also been a bias in the sample attributable to self-selection into the study. Young people with fewer psychiatric issues may have been more inclined to take part. In comparison with other age groups, Tompsett et al.51 found lower rates of mental health difficulties among young homeless people compared with older homeless groups; this study compared 13- to 17-year-old people with 18- to 34-year-old and 35- to 78-year-old homeless people.

Homelessness and Psychopathology

Fifteen studies explored the relationship between homelessness and psychopathology (11 used a longitudinal design; Table 4). Two studies (1 longitudinal) examined psychiatric inpatient samples and found a strong link between serious psychopathology and homelessness. Of young people admitted to psychiatric hospital in Switzerland, 24.9% were homeless before admission.72 A comparison with the nonpsychiatric population cannot be made as there was no accurate data on the proportion of homeless persons. Embry et al.70 found that 33% of adolescents discharged from psychiatric care experienced homelessness in the subsequent 5 years.

TABLE 4—

Studies Examining the Relationship Between Homelessness and Mental Health in Systematic Review of Published Research on Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Among Young Homeless People, 2000–2012

| Author | Country | Sample Size | Sampling Strategy | Age Range, Years | Design | Key Findings |

| Baker et al.68 | US | 166 | Shelter (runaways) | 12–18 | Longitudinal | Youth emotional problems were associated with recidivism for repeat runaways. |

| Bao et al.69 | US | 602 | Street, shelter, drop-in center (homeless and runaways) | 12–22 | Cross-sectional | Support from friends on the street was associated with reduced depressive symptoms. Association with deviant peers was associated with increased depressive symptoms. |

| Bearsley-Smith et al.24 | Australia | Homeless: 137;At risk for homelessness: 766;Not at risk for homelessness: 4844 | Shelter, school support, health services | Nonhomeless: 14–17;Homeless: 13–19 | Cross-sectional | Adolescents at risk for homelessness showed at least equivalent levels of depressive symptoms to adolescents who were already homeless. Those at risk for homelessness also showed higher levels of depression than those not at risk for homelessness. |

| Craig and Hodson28 | UK | 161 | Shelter | 16–21 | Longitudinal | Two thirds of those with a psychiatric condition at index interview remained symptomatic at follow-up. Persistence of psychiatric disorder was associated with rough sleeping. Persistent substance abuse was associated with poorer housing outcomes at follow-up. |

| Embry et al.70 | US | 83 | Adolescents discharged from psychiatric inpatient facility | Mean = 17 | Longitudinal | One third of youths discharged from a psychiatric inpatient facility experienced at least one episode of homelessness. Having a “thought disorder” such as schizophrenia was inversely related to becoming homeless. |

| Fowler et al.71 | US | 265 | Care leavers | Mean = 20.5 | Longitudinal | Among foster care leavers those with increasingly unstable housing conditions and those with continuously unstable housing conditions after leaving care were more likely to be affected by emotional and behavioral problems. |

| Lauber et al.72 | Switzerland | 16 247 | Psychiatric hospital | 18+ | Cross-sectional population study | Among patients admitted to psychiatric hospital, being of a young age (18–25) increased likelihood of being homeless at admission. |

| Martijn and Sharpe73 | Australia | 35 | Street dwelling, shelter, temporary accommodation, supported accommodation | 14–25 | Cross-sectional | Trauma was a common experience before youths became homeless. Once homeless there was an increase in mental health diagnoses including drug and alcohol issues. |

| Kamieniecki11 | Australia | NA | NA | 12–25 | Comparative review | A number of studies reviewed identified that psychiatric disorder often preceded homelessness particularly PTSD. However, homelessness also appeared to increase risk for development of further mental health difficulties, in particular substance issues and self-injurious behaviors. |

| Rohde et al.43 | US | 523 | Street dwelling, shelter | Adolescents under 21 | Longitudinal | Depression tended to precede rather than follow homelessness (73% reported first episode of depression before homelessness). |

| Rosario et al.74 | US | 156 (75 homeless, 81 never homeless) | Lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths | Mean = 18.3 | Longitudinal | Homelessness was associated with subsequent mental health difficulties. Stressful life events and negative social relationships mediated the relationship between homelessness and symptomatology. |

| Shelton et al.46 | US | 14 888 | High-school students | 11–18 at baseline;18–28 at follow-up | Longitudinal population-based | Mental health difficulties were identified as a potential independent risk factor for homelessness although it is noted that homelessness could also have preceded mental health issues. |

| Stewart et al.48 | US | 374 | Street dwelling, shelter, drop-in centers | 13–21 | Cross-sectional | 83% of homeless adolescents were victimized while homeless. This increased risk for developing PTSD. |

| Van den Bree et al.75 | US | 10 433 | High-school students | 11–18 at baseline;18–28 at follow-up | Longitudinal population-based | Depressive symptoms and substance use predicted homelessness but not independently. Victimization and family dysfunction were independent predictors of homelessness. |

| Whitbeck et al.59 | US | 602 | Street dwelling, shelter, drop-in center (homeless and runaway youths) | 12–22 | Cross-sectional | Street experiences, in particular, victimization, increased risk of depressive symptoms as well as co-occurring problems such as depression, substance use, and conduct disorder. |

Note. NA = not applicable.

Among youths at a shelter, Craig and Hodson28 found that 70% of young people diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder remained symptomatic 12 months later. Experience of rough sleeping, in particular, was linked with persistent disorder. Similarly, substance abuse disorders were also associated with poorer housing outcomes. Fowler et al.71 found in a sample of care leavers that those with emotional or behavioral problems were more likely to have less stable housing trajectories 2 years later and were more likely to have experienced homelessness or to have lived in unsuitable or temporary accommodation. Martijn and Sharpe73 identified that all participants who had psychological disturbances or an addiction before they became homeless had developed further psychological disturbances, addictions, or criminal behavior since they became homeless. Whitbeck et al.59 found that family abuse and street experiences such as victimization and risky street activity predicted adolescent depression. Rohde et al.43 identified depressive symptoms as commonly occurring before first instances of homelessness in 73% of their sample suggesting that this form of psychopathology was liable to precede homelessness.

Bearsley-Smith et al.24 compared psychological profiles of young people experiencing homelessness and young people with risk factors for homelessness. The young people with risk factors for homelessness were shown to have higher levels of depressive symptoms indicating that mental health problems may precede homelessness. However, this study was cross-sectional in design, which limits the ability to make inferences on direction of causality.

Some research has also begun to investigate whether certain types of disorders, such as substance abuse and PTSD, appear to worsen or are triggered by homelessness.48,72,73 These studies showed that young people were vulnerable to trauma once they became homeless and this was associated with PTSD. For example, Stewart et al.48 found that 83% of the youths in their sample were victims of physical or sexual assault after becoming homeless and 18% went on to develop PTSD. Self-harm behavior has also been positively associated with having ever spent time on the street.55

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we examined the role of psychopathology in youth homelessness. Collectively, these findings indicate a reciprocal relationship, whereby psychopathology often precedes homelessness and can prolong episodes of homelessness. Homelessness, in turn, appears to both compound psychological issues and increase the risk of psychopathology occurring. More prospective longitudinal research is required to support this conclusion.

Prevalence of Psychopathology

We found high levels of psychiatric disorder across all studies that used a full psychiatric assessment, indicating a strong link between psychopathology and youth homelessness. We found conduct disorder, major depression, psychosis, mania, hypomania, suicidal thoughts or behaviors, PTSD, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder to be particularly prevalent, indicating types of disorder that may be associated with the condition. The prevalence of some disorders found among homeless youths was greater than those found in community samples (Table 3). These results are supported by studies that used subscale or inventory measures that indicate mental health issues such as internalizing or externalizing symptomology. All but 1 of these studies also found high levels of psychopathology.

Comorbidity was examined in 4 studies. These studies suggested that the presence of multiple disorders is high within this population.11,41,47,58 Comorbidity has most often been examined between alcohol or other substance use disorders and nonsubstance psychiatric conditions. Only 2 studies58,63 looked at comorbidity of other psychiatric disorders, suggesting a link between other forms of psychopathology (Table 2). More research into the presence of multiple diagnoses among young homeless people is important. It will reveal the extent of complicated mental health issues within this group compared with nonhomeless samples, with implications for service use delivery.

Psychopathology and Homelessness

Only 11 studies used a prospective, longitudinal research design. The dearth of research using this approach limits insight on the issue of direction of effects. However, existing research suggests a reciprocal relationship between homelessness and psychopathology. Psychopathology appears to make a young person more vulnerable to becoming homeless.24,64,71 Once a young person has become homeless, the experience appears to compound or trigger psychopathology and, in turn, psychopathology seems to prevent individuals from moving on from homelessness successfully.28,48,55,72,73

For some mental health problems the picture is a little more detailed. Experiences of street homelessness appeared to increase risk of PTSD.48,55,66 The vulnerability of young people who sleep on the street is extreme and these individuals are more likely to experience victimization and serious illness and to feel unsafe. It is interesting that it seems that abuse experiences before leaving home for the first time are also associated with greater risk of revictimization once one becomes homeless.45,55 This indicates that although psychopathology may or may not precede homelessness, traumatic experiences in the home may lead to further traumatic experiences once one is homeless. This leaves the young person with an increased risk of developing psychiatric disorders including PTSD, depression, suicidal ideation, and substance misuse.52,58,67,76

Limitations

The definitions of homelessness used across the range of studies reviewed here limit the generalization of results. Some of the studies reported that young people who had spent time on the street had poorer mental health compared with those who resided only in shelters.76 This indicates that other studies that have included a range of types of homelessness may have masked the extent of psychopathology among street homeless youths.

Another issue of definition is the use of the term “runaway.” Findings from these studies may not be generalizable to the rest of the youth homeless population. However, the levels of psychiatric disorder found among the studies examining runaways are comparable to those examining homeless youths.77,78 The issues of definition prevent the calculation of effect sizes as the samples used across studies cannot be compared systematically.

The length of time a young person has spent homeless also varied considerably among samples. The length of homelessness may have an impact upon the severity of psychopathology. For example, Milburn et al.42 found higher rates of psychiatric disorder and substance misuse among those with longer homelessness experiences. The age of participants is another factor that varies widely across studies (12 years77 to 26 years33), which also makes comparisons more difficult.

A major caveat of the research in this field is the lack of full psychiatric assessments used to profile participants’ mental health. Therefore, the findings of high prevalence of certain types of disorder26,27,29,73,76 by some of the studies is not supported by other studies that used less comprehensive measures. Another key difference between studies is the use of differing diagnostic criteria. Varying use of the DSM-III18 versus DSM-IV19 may also account for some variability between studies.

Implications for Future Research and Practice

This review demonstrates the vulnerability of young homeless people in terms of psychopathology and reveals the need for greater levels of support and prevention work. Intervening before homelessness by identifying those at risk could reduce incidence of homelessness as well as mental health difficulties. Providing support for those who do become homeless is essential because of the almost universally high levels of psychiatric disorder found in this population. However, it is important to note that despite the obvious need for mental health services shown by the review, young homeless people rarely access the support that they require.79,80 Psychiatric screening programs for youths in shelters and other temporary accommodation, followed by availability of targeted services tailored to address potential comorbid psychopathology, may go some way to addressing this issue. Intervention efforts need to be accessible to this underserved population and work around the chaotic nature of their lives and their mental health needs.

A great deal of further research is required for intervention efforts to be successful. More must be done to examine the psychiatric profile of young homeless people to gather an accurate and full overview of the forms of psychiatric disorder that are common among this group, including research to establish patterns of comorbidity. More longitudinal research and examination of those in the general population at risk for homelessness is required to disentangle the temporal relationship between psychopathology and youth homelessness. This systematic review reveals a picture of extensive psychopathology among young people with experiences of homelessness. It also begins to unravel the complex reciprocal relationship between the 2 phenomena and identifies numerous areas for future inquiry.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council, the Technology Strategy Board, and the Welsh Government for funding the project of which this research forms part.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not required because no human participants were involved in the development of the submitted article.

References

- 1.The National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty. 2004 Homelessness in the United States and the human right to housing. Available at: http://www.nlchp.org/content/pubs/homelessnessintheusandrightstohousing.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folsom D, Jeste DV. Schizophrenia in homeless persons: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105(6):404–413. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor KM, Sharpe L. Trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder among homeless adults in Sydney. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42(3):206–213. doi: 10.1080/00048670701827218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pleace N, Fitzpatrick D. Centre Point Youth Homelessness Index: An Estimate of Youth Homelessness for England. York, UK: Centre for Housing Policy, University of York; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundin E. What are the risk factors for becoming and staying homeless? A mixed-methods study of the experience of homelessness among adult people. European Psychiatry. 2012;27(1):1171. [Google Scholar]

- 6. United Nations. Young people’s transitions to adulthood: progress and challenges. In: World Youth Report 2007. Available at: http://social.un.org/index/WorldYouthReport/2007.aspx. Accessed June 1, 2012.

- 7.Hughes JR, Clark SE, Wood W et al. Youth homelessness: the relationships among mental health, hope, and service satisfaction. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(4):274–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quilgars D. Youth homelessness. In: O’Sullivan E, Busch-Geertsema V, Quilgars D, Pleace N, editors. Homeless Research in Europe. Brussels, Belgium: Feantsa; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quilgars D, Johnsen S, Pleace N. Youth Homelessness in the UK. York, UK: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muir-Cochrane E, Fereday J, Jureidini J, Drummond A, Darbyshire P. Self-management of medication for mental health problems by homeless young people. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2006;15(3):163–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamieniecki GW. Prevalence of psychological distress and psychiatric disorders among homeless youth in Australia: a comparative review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(3):352–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulik DM, Gaetz S, Crowe C, Ford-Jones E. Homeless youth’s overwhelming health burden: a review of the literature. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16(6):E43–E47. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.6.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sleegers J, Spijker J, Van Limbeek J, Van Engeland H. Mental health problems among homeless adolescents. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97(4):253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kipke MD, Montgomery SB, Simon TR, Iverson EF. “Substance abuse” disorders among runaway and homeless youth. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32(7-8):969–986. doi: 10.3109/10826089709055866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wincup E, Buckland G, Bayliss R.Youth Homelessness and Substance Use: Report to the Drugs and Alcohol Research Unit London, UK: UK Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson G, Chamberlain C. Homelessness and substance abuse: which comes first? Aust Soc Work. 2008;61(4):342–356. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Classifications of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy M, Thompson S. Predictors of trauma-related symptoms among runaway adolescents. J Loss Trauma. 2010;15:212–227. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coward Bucher CE. Toward a needs-based typology of homeless youth. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(6):549–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bearsley-Smith CA, Bond LM, Littlefield L, Thomas LR. The psychosocial profile of adolescent risk of homelessness. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17(4):226–234. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0657-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beijer U, Andreasson S. Gender, hospitalization and mental disorders among homeless people compared with the general population in Stockholm. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(5):511–516. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bender K, Ferguson K, Thompson S, Komlo C, Pollio D. Factors associated with trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder among homeless youth in three U.S. cities: the importance of transience. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(1):161–168. doi: 10.1002/jts.20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cauce AM, Paradise M, Ginzler JA et al. The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents: age and gender differences. J Emot Behav Disord. 2000;8(4):230–239. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craig TKJ, Hodson S. Homeless youth in London: II. Accommodation, employment and health outcomes at 1 year. Psychol Med. 2000;30(1):187–194. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crawford DM, Trotter EC, Hartshorn KJS, Whitbeck LB. Pregnancy and mental health of young homeless women. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(2):173–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fournier ME, Austin SB, Samples CL, Goodenow CS, Wylie SA, Corliss HL. A comparison of weight-related behaviors among high school students who are homeless and non-homeless. J Sch Health. 2009;79(10):466–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frencher SK, Benedicto CMB, Kendig TD, Herman D, Barlow B, Pressley JC. A comparative analysis of serious injury and illness among homeless and housed low income residents of New York City. J Trauma. 2010;69(4suppl):S191–S199. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f1d31e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gwadz MV, Nish D, Leonard NR, Strauss SM. Gender differences in traumatic events and rates of post-traumatic stress disorder among homeless youth. J Adolesc. 2007;30(1):117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hadland SE, Marshall BDL, Kerr T, Qi JZ, Montaner JS, Wood E. Depressive symptoms and patterns of drug use among street youth. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(6):585–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. The Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Multicultural Supplement to the Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kidd SA. Factors precipitating suicidality among homeless youth: a quantitative follow-up. Youth Soc. 2006;37(4):393–422. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kidd SA, Carroll MR. Coping and suicidality among homeless youth. J Adolesc. 2007;30(2):283–296. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirst M, Frederick T, Erickson PG. Concurrent mental health and substance use problems among street-involved youth. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2011;9(5):543–553. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirst M, Frederick T, Erickson PG. Concurrent mental health and substance use problems among street-involved youth. Erratum. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2011;9(5):554. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McManus HH, Thompson SJ. Trauma among unaccompanied homeless youth: the integration of street culture into a model of intervention. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2008;16(1):92–109. doi: 10.1080/10926770801920818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merscham C, Van Leeuwen JM, McGuire M. Mental health and substance abuse indicators among homeless youth in Denver, Colorado. Child Welfare. 2009;88(2):93–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Rice E, Mallet S, Rosenthal D. Cross-national variations in behavioral profiles among homeless youth. Am J Community Psychol. 2006;37(1-2):63–76. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-9005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rohde P, Noell J, Ochs L, Seeley JR. Depression, suicidal ideation and STD related risk in homeless older adolescents. J Adolesc. 2001;24:447–460. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenthal D, Mallett S, Gurrin L, Milburn N, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Changes over time among homeless young people in drug dependency, mental illness and their co-morbidity. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12(1):70–80. doi: 10.1080/13548500600622758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryan KD, Kilmer RP, Cauce AM, Watanabe H, Hoyt DR. Psychological consequences of child maltreatment in homeless adolescents: untangling the unique effects of maltreatment and family environment. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(3):333–352. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shelton KH, Taylor PJ, Bonner A, van den Bree M. Risk factors for homelessness: evidence from a population-based study. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):465–472. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slesnick N, Prestopnik J. Dual and multiple diagnosis among substance using runaway youth. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2005;31(1):179–201. doi: 10.1081/ADA-200047916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stewart AJ, Steiman M, Cauce A, Cochran BN, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder among homeless adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):325–331. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200403000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor H, Stuttaford M, Broad B, Vostanis P. Why a “roof” is not enough: the characteristics of young homeless people referred to a designated mental health service. J Ment Health. 2006;15(4):491–501. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wing JK, Beevor AS, Curtis RH. Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (Ho NOS). Research and development. Br J Psychiatry.1998. 172:11–18. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tompsett CJ, Fowler PJ, Toro PA. Age differences among homeless individuals: adolescence through adulthood. J Prev Interv Community. 2009;37(2):86–99. doi: 10.1080/10852350902735551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tyler K, Melander L, Almazan E. Self injurious behavior among homeless young adults: a social stress analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(2):269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gratz K. Measurement of deliberate self-harm: preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm inventory. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2001;23(4):253–263. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Johnson KD. Self-mutilation and homeless youth: the role of family abuse, street experiences, and mental disorders. J Res Adolesc. 2003;13(4):457–474. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Votta E, Farrell S. Predictors of psychological adjustment among homeless and housed female youth. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(2):126–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Votta E, Manion I. Suicide, high-risk behaviors, and coping style in homeless adolescent males’ adjustment. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitbeck LB, Chen XJ, Hoyt DR, Tyler KA, Johnson KD. Mental disorder, subsistence strategies, and victimization among gay, lesbian, and bisexual homeless and runaway adolescents. J Sex Res. 2004;41(4):329–342. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Bao WN. Depressive symptoms and co-occurring depressive symptoms, substance abuse, and conduct problems among runaway and homeless adolescents. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):721–732. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychological Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Johnson KD, Chen X. Victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder among runaway and homeless adolescents. Violence Vict. 2007;22(6):721–734. doi: 10.1891/088667007782793165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whitbeck LB, Johnson KD, Hoyt DR, Cauce AM. Mental disorder and comorbidity among runaway and homeless adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(2):132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoder KA, Longley SL, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. A dimensional model of psychopathology among homeless adolescents: suicidality, internalizing, and externalizing disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36(1):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9163-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.National Centre for Social Research, The Department of Health Sciences University of Leicester. Adult Psychiatric Morbidity: Results of a Household Survey. Leeds, UK: NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [corrected in Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(7):768] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thompson SJ, McManus H, Voss T. Posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse among youth who are homeless: treatment issues and implications. Brief Treat Crisis Interv. 2006;6(3):206–217. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baker AJL, McKay MM, Lynn CJ, Schlange H, Auville A. Recidivism at a shelter for adolescents: first-time versus repeat runaways. Soc Work Res. 2003;27(2):84–93. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bao WN, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Abuse, support, and depression among homeless and runaway adolescents. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(4):408–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Embry LE, Vander Stoep A, Evens C, Ryan KD, Pollock A. Risk factors for homelessness in adolescents released from psychiatric residential treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(10):1293–1299. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fowler PJ, Toro PA, Miles BW. Pathways to and from homelessness and associated psychosocial outcomes among adolescents leaving the foster care system. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(8):1453–1458. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.142547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lauber C, Lay B, Rossler W. Homelessness among people with severe mental illness in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135(3-4):50–56. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.10815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martijn C, Sharpe L. Pathways to youth homelessness. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Homelessness among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: implications for subsequent internalizing and externalizing symptoms. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(5):544–560. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9681-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van den Bree MBM, Shelton K, Bonner A, Moss S, Thomas H, Taylor PJ. A longitudinal population-based study of factors in adolescence predicting homelessness in young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(6):571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haber MG, Toro PA. Parent adolescent violence and later behavioural health problems among homeless and housed youth. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(3):305–318. doi: 10.1037/a0017212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Erdem G, Slesnick N. That which does not kill you makes you stronger: runaway youth’s resilience to depression in the family context. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(2):195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leslie MB, Stein JA, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Sex specific predictors of suicidality among runaway youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31(1):27–40. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reilly JJ, Herrman HE, Clarke DM, Neil CC, McNamara CL. Psychiatric disorders in and service use by young homeless people. Med J Aust. 1994;161(7):429–432. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1994.tb127524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bines W. The Health of Single Homeless People. York, UK: Centre for Housing Policy, University of York; 1994. [Google Scholar]