Abstract

We provided a synthesis of use, summarized key issues in applying, and highlighted exemplary applications in the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework. We articulated key RE-AIM criteria by reviewing the published literature from 1999 to 2010 in several databases to describe the application and reporting on various RE-AIM dimensions.

After excluding nonempirical articles, case studies, and commentaries, 71 articles were identified. The most frequent publications were on physical activity, obesity, and disease management. Four articles reported solely on 1 dimension compared with 44 articles that reported on all 5 dimensions of the framework.

RE-AIM was broadly applied, but several criteria were not reported consistently.

MANY INTERVENTIONS FOUND to be effective in prevention and disease management research fail to be widely adopted or translated into meaningful outcomes.1–3 Barriers to wide-scale implementation arise at multiple levels: citizens and patients, the practitioner and staff, organizational, and community and policy levels.4 Several evaluation frameworks have been developed to facilitate translation of research findings. Some of these frameworks are intended to help guide both the development and evaluation of an intervention,5 whereas others are designed solely for evaluation.6

The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework is now 14 years old. The first RE-AIM publication was in the American Journal of Public Health in 1999.7 The model grew out of the need for improved reporting on key issues related to implementation and external validity of health promotion and health care research literature.8 RE-AIM was developed partially as a response to trends in research conducted under optimal efficacy conditions instead of in real-world complex settings.9 The concern was not that this type of research was being conducted, but rather that it was and is still often considered the only type of valid research and the “gold standard” for decision-making and guidelines. Although intended to be used at all stages of research from planning through evaluation and reporting, and across different types (e.g., programs, policies, and environmental change interventions),10,11 RE-AIM elements follow a logical sequence, beginning with adoption and reach, followed by implementation and efficacy or effectiveness, and finishing with maintenance.

The dimensions of the framework are defined as follows. Reach is the absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of individuals who are willing to participate in a given initiative. Effectiveness is the impact of an intervention on outcomes, including potential negative effects, quality of life, and economic outcomes. Adoption is the absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of settings and intervention agents who are willing to initiate a program. Implementation refers to the intervention agents’ fidelity to the various elements of an intervention’s protocol. This includes consistency of delivery as intended and the time and cost of the intervention. Maintenance is the extent to which a program or policy becomes institutionalized or part of the routine organizational practices and policies. Maintenance also has referents at the individual level. At the individual level, it is defined as the long-term effects of a program on outcomes 6 or more months after the most recent intervention contact.

RE-AIM has continued to evolve and has been used to report findings from health research in a number of different ways. A brief summary of how the framework has evolved over time would be helpful to place this review in context. RE-AIM was initially designed to help evaluate interventions and public health programs, to produce a more balanced approach to internal and external validity, and to address key issues important for dissemination and generalization.7 Over time, it has expanded to include more diverse content areas,12–15 and is used in planning in addition to reporting and reviews.16,17 More recently, it has been applied to policies18 and community-based multilevel interventions,19 as well as to reduce health disparities.20 Along with these changes there has been increased appreciation for the importance of context and the need for qualitative measures to help understand RE-AIM results. Finally, we and a related recent review of grant applications21 (as opposed to the published literature) found, congruent with earlier reviews, that almost all health promotion and disease management literature underreport on issues such as participation at the setting or staff level, on maintenance or sustainability, and especially costs, so these issues have been emphasized as needing increased attention.

The purposes of this article are to (1) describe criteria for reporting on various dimensions of the RE-AIM framework, (2) review the empirical published literature to describe the application, consistency of use, and reporting on RE-AIM dimensions over time, (3) highlight lessons learned from applying RE-AIM, and (4) make recommendations for future applications.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic literature review to identify studies using the RE-AIM framework. A literature search was conducted using 6 databases (MEDLINE, PubMed, PSYCHinfo, EBSCOhost, Web of Science, and Scopus), using RE-AIM, RE-AIM framework, RE-AIM model, and RE-AIM methods as the search terms. For inclusion, articles had to be published in English, stated the use of any of the 5 RE-AIM dimensions, and been published from 1999 (the publication of the initial article introducing RE-AIM) to December 31, 2010.

The lead author reviewed the abstracts to confirm the use of the RE-AIM framework to report data or evaluate the project. If the abstract was unclear, the full article was assessed. Because this review focused on the application of RE-AIM in the empirical and evaluation literature, articles were excluded if they were commentaries, theoretical papers, published abstracts, dissertations, book chapters, editorials, or did not report on the use of RE-AIM for planning or evaluation of a study, program, or policy. In addition, references for each of the confirmed articles were reviewed to identify additional articles to include. Finally, e-mails were sent to known RE-AIM researchers soliciting articles related to RE-AIM.

An abstraction and coding scheme was developed to guide the review of articles. The scheme was modified from earlier RE-AIM reviews21,22 and included 34 criteria across the 5 dimensions. These criteria, summarized in the left-hand column of Table 1, included the original constructs from the framework (e.g., assessing representativeness, effectiveness, adoption by staff and setting, fidelity to intervention or policy, maintenance of effect at the individual level, and sustainability at the setting level), as well as additional items that represented the evolution of RE-AIM over time (e.g., costs, use of qualitative methods, adaptations). In addition to coding RE-AIM criteria, topic area, publication year, purpose of the article in relation to reporting on RE-AIM dimensions, lessons learned pertinent to RE-AIM, and challenges to using RE-AIM were abstracted.

TABLE 1—

Inclusion of RE-AIM Elements Across All Articles Included in Review by Dimension and Evaluation Criteria: 1999–2010

| RE-AIM Dimension and Evaluation Criteria Reported | Average Inclusion, % |

| Reach (n = 65) all 4 criteria reported | 0.0 |

| Exclusion criteria (% excluded or characteristics) | 61.5 |

| Percentage of individuals who participate, based on valid denominator | 83.1 |

| Characteristics of participants compared with nonparticipants; to local sample | 58.5 |

| Use of qualitative methods to understand recruitment | 12.3 |

| Effectiveness (n = 55) all 6 criteria reported | 1.9 |

| Measure of primary outcome | 89.1 |

| Measure of primary outcome relative to public health goal | 76.4 |

| Measure of broader outcomes or use of multiple criteria (e.g., measure of quality of life or potential negative outcome) | 56.4 |

| Measure of robustness across subgroups (e.g., moderation analyses) | 48.2 |

| Measure of short-term attrition (%) and differential rates by patient characteristics or treatment group | 43.6 |

| Use of qualitative methods/data to understand outcomes | 7.3 |

| Adoption—setting level (n = 58) all 4 criteria reported | 0.0 |

| Setting exclusions (% or reasons or both) | 39.7 |

| Percentage of settings approached that participate (valid denominator) | 56.9 |

| Characteristics of settings participating (both comparison and intervention) compared with either (1) nonparticipants or (2) some relevant resource data | 37.9 |

| Use of qualitative methods to understand setting level adoption | 3.5 |

| Adoption—staff level (n = 53) all 4 criteria reported | 0.0 |

| Staff exclusions (% or reasons or both) | 11.3 |

| Percent of staff offered that participate | 35.9 |

| Characteristics of staff participants vs nonparticipating staff or typical staff | 17.0 |

| Use of qualitative methods to understand staff participation/staff level adoption | 9.4 |

| Implementation (n = 64) all 6 criteria reported | 1.6 |

| Percent of perfect delivery or calls completed (e.g., fidelity) | 76.6 |

| Adaptations made to intervention during study (not fidelity) | 14.1 |

| Cost of intervention—time | 14.1 |

| Cost of intervention—money | 23.4 |

| Consistency of implementation across staff/time/settings/subgroups (not about differential outcomes, but process) | 35.9 |

| Use of qualitative methods to understand implementation | 15.6 |

| Maintenance—individual level (n = 46) all 6 criteria reported | 2.2 |

| Measure of primary outcome (with comparison with a public health goal) at ≥ 6 mo follow-up after final treatment contact | 63.0 |

| Measure of primary outcome ≥ 6 mo follow-up after final treatment contact | 56.5 |

| Measure of broader outcomes (e.g., measure of quality of life or potential negative outcome) or use of multiple criteria at follow-up | 32.6 |

| Robustness data—something about subgroup effects over the long-term | 26.1 |

| Measure of long-term attrition (%) and differential rates by patient characteristics or treatment condition | 28.3 |

| Use of qualitative methods data to understand long-term effects | 4.4 |

| Maintenance—setting level (n = 51) all 4 criteria reported | 0.0 |

| If program is still ongoing at ≥ 6 mo posttreatment follow-up | 41.2 |

| If and how program was adapted long-term (which elements retained after program completed) | 7.8 |

| Some measure/discussion of alignment to organization mission or sustainability of business model | 15.7 |

| Use of qualitative methods data to understand setting level institutionalization | 5.9 |

Note. RE-AIM = Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance.

All articles were independently coded by 2 of the authors (B. G. and J. A. S.). Each article was (1) evaluated to identify stated use of any of the 5 dimensions of the framework, (2) coded on the criteria (Table 1) for RE-AIM dimensions specified, and (3) assessed for appropriate use of the framework. For example, if an article stated it was reporting on reach and effectiveness, it was only evaluated on these 2 dimensions, not all 5 RE-AIM dimensions. Criteria not applicable for the article were coded as NA and excluded from scoring. If a criterion was applied incorrectly, it was coded as inappropriate use for that specific RE-AIM dimension. We calculated a personalized RE-AIM score for each article (maximum score of 34) based on number of dimensions evaluated and the reported criteria within each dimension, and converted this to a percentage of possible score to provide a comparable summary score across studies. In a subanalysis, articles were evaluated against the 21 original RE-AIM criteria. Initial evaluation of 8 randomly selected articles and an additional 16 articles compared at the end of the coding period showed high agreement (87.9%); any discrepancies were discussed and resolved. No one particular criterion proved to be more difficult than the others. Kappa coefficients were not calculated for this study because many categories had true zero cells, and this distribution can be problematic when correcting for chance agreement. Results were reported as percentages of articles that included the various RE-AIM criteria.

RESULTS

Of the 178 citations identified, 107 were excluded at various stages because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Seventy-one articles were included in this review (detailed information related to these articles can be found as data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Article identification and selection process for RE-AIM publications included in systematic review.

Note. RE-AIM = Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance.

Content areas of the articles included 26 on physical activity and obesity, 21 on disease self-management, 7 on tobacco or substance abuse, 5 on health promotion, 1 on mental health and dementia, 1 on cancer prevention, and 10 on other or multiple topics. The research settings in which RE-AIM was applied included 18 for community or policy settings, 16 for primary care, 4 for health care or hospitals, 2 for schools, and 31 for other or nonspecified settings. The journals that most frequently published RE-AIM articles were American Journal of Preventive Medicine (7 articles), Annals of Behavioral Medicine (4 articles), American Journal of Public Health, and Patient Education Counseling (3 articles each).

Use of RE-AIM

Of the 71 articles, there were 14 different combinations of reporting on RE-AIM dimensions; 4 articles reported solely on 1 dimension, 5 reported on 2 dimensions, 7 reported on 3 dimensions, 11 reported on 4 dimensions, and 44 reported on all 5 dimensions of the framework. Reach was the most frequently reported dimension (91.5%), followed by implementation (90.1%), effectiveness (77.5%), adoption at the setting level (75.3%), adoption at the staff level (74.6%), maintenance at the setting level (71.8%), and maintenance at the individual level (64.8%; Table 1).

None of the articles reviewed addressed all 34 criteria across the 5 dimensions. As shown in Table 1, within each of the dimensions there was 1 criterion that was reported more consistently than others. These items were most aligned with the basic definitions originally proposed for each of the RE-AIM dimensions.

Reach.

The most commonly reported reach criterion was the percentage of individuals who participated based on a valid denominator (83.1%). A valid denominator was calculated by enumerating all potential participants in the target population not excluded by eligibility criteria for the study or program. Information to allow for assessment of the representativeness of those who participated in a study was reported less frequently (58.5%). Use of qualitative methods was reported least often, and none of the 65 articles evaluated for reach addressed all 4 criteria.

Effectiveness.

Measurement of the primary identified outcome was the most frequently reported effectiveness element (89.1%). Measurement of the primary outcome relative to a public health goal and measurement of broader outcomes or multiple outcomes were less frequently reported. Short-term attrition, important because it permits comparing characteristics of those who complete the intervention or program to those who do not, was reported in 40% of the articles. There was 1 article23 of the 55 that addressed all 6 of the effectiveness criteria.

Adoption—setting level and staff level.

Similar to the results of reach at the participant level, the percentage of settings and staff approached that participated based on a valid denominator were the most highly reported component of this dimension (56.9% and 35.9%, respectively). A valid denominator was calculated by enumerating all potential settings (and staff within the settings) not excluded by eligibility criteria. Information necessary for evaluation of representativeness of the settings and the staff were reported less frequently (37.9% for setting and 17.0% for staff). Data on adoption at the staff or delivery level were reported less often than at the setting level. None of the articles addressed all criteria for adoption.

Implementation.

Fidelity or the proportion of intervention components that was implemented according to established protocols (e.g., duration and frequency of contact, completion of all content areas as specified in the evidence-based protocol) was the most commonly reported implementation element. Consistency of implementation across staff, time, or setting was reported in only half of the articles, and very few addressed implementation adaptations made. Again, only 1 article24 of the 64 that reported implementation data addressed all 6 components.

Maintenance—individual level.

Measurement of the primary outcome 6 months or longer after the last intervention contact compared with a public health goal was the most frequently reported outcome (63.0%), followed by reporting of long-term outcomes (56.5%). Comparing long-term outcomes to a public health goal helped to understand the impact on the health beyond the study population. Measurement of long-term attrition was reported in approximately 30% of the articles, and the least frequently reported criterion was the use of qualitative methods to understand long-term effects. Only 1 article25 reported all the criteria for this dimension.

Maintenance—setting level.

Maintenance at the setting level was reported less frequently than at the individual level (Table 1). Reporting on the continuation of a program or intervention after 6 or more months following the last intervention contact was the most often reported element (41.2%). The additional 3 criteria were all reported less than 20% of the time.

Qualitative methods were rarely used to understand results for any of the RE-AIM dimensions. Qualitative methods are increasingly being used in evaluation work to provide detail and context (such as understanding facilitators and barriers to delivering the intervention or program) to assist interpretation of quantitative data. Qualitative methods can range from case studies to in-depth interviews or observational field notes.

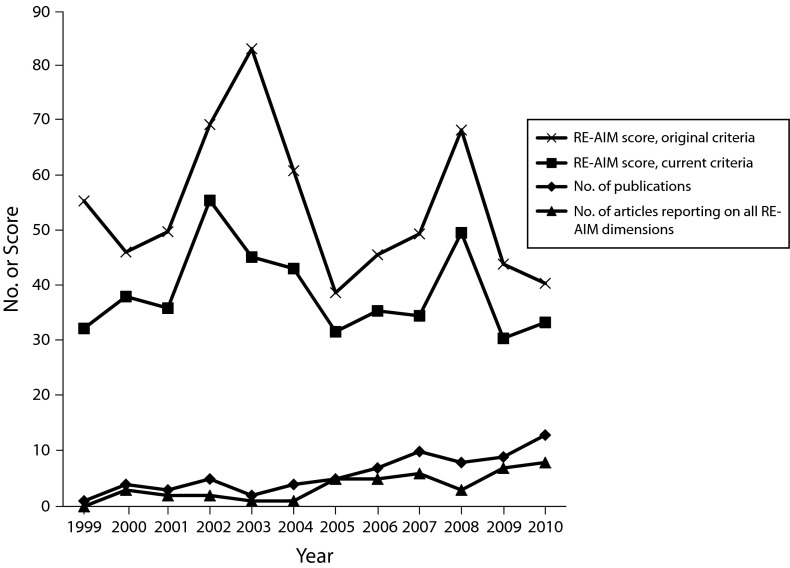

As shown in Figure 2, the number of publications by year and RE-AIM summary scores (using both the original and present criteria) were analyzed for trends regarding quantity and quality over time. No trend was observed in the number of publications that reported on all 5 RE-AIM dimensions over time. There was no increase over time in quality or comprehensiveness of reporting when the personalized RE-AIM scores (adjusted for the number of dimensions addressed) were analyzed for trends.

FIGURE 2—

Mean personalized RE-AIM scores (based on original and current criteria), number of empirical RE-AIM publications included in review (n = 71), and number of publications reporting on all 5 RE-AIM dimensions, by year.

Note. RE-AIM = Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance.

Lessons Learned

We identified common problems in applying the RE-AIM framework highlighted in the following; however, few articles met all reporting criteria for any of the dimensions. Table 2 provides a comprehensive list of problems identified when reporting on RE-AIM criteria, along with recommendations and examples for addressing the most common reporting challenges.

TABLE 2—

Common Problems, Recommendations, and Examples for Reporting RE-AIM Dimensions: 1999–2010

| RE-AIM Dimension | Common Problem(s) | Recommendation | Example |

| Reach | Not reporting characteristics of participants compared with nonparticipants. Not reporting on recruitment methods and implicit “screening/selection.” Not reporting on a “valid denomintaor.” | Report on any criteria you can, even if it is just 1 characteristic. This allows for others to assess the representativeness of participants to some degree. | Haas et al.15 Patient characteristics were associated with different call outcomes. Toll-free opt out after receiving the informational letter declined with age. Patients aged > 66 y were more likely to have an invalid phone number, but were also more likely be contacted by the IVRS server (OR = 1.33; 95% CI = 1.11, 1.59), and were more likely to participate (OR = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.19, 1.81) than those aged 56–65 y. Blacks were more likely to have an invalid phone number than Whites (OR = 1.89; 95% CI = 1.40, 2.55). Hispanics were more likely than Whites to use the toll-free opt out line or have an invalid phone number, and were less likely to participate (OR = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.42 0.76). There were no significant differences in participation by gender. Compared with those who lived in a high-income community, those in a low-income community were less likely to use the toll-free opt out line, less likely to have an invalid phone number, and less likely to participate (OR = 0.69; 95% CI = 0.58, 0.82). |

| Effectiveness | Not reporting measurement of short-term attrition or differential rates by participant characteristic or treatment group. Not reporting on broader effects (e.g., quality of life or unintended consequences). Measure of primary outcome relative to public health goal | Reporting of short-term loss to follow-up can easily be added to CONSORT figures. Use national guidelines (e.g., Healthy People 2020). | Glasgow et al.23 See Figure 1 on page 139. Attrition at 2-mo follow-up reported for both intervention arms in the CONSORT figure. Maxwell, et al.26 One of the goals of Healthy People 2012 is to increase the proportion of women aged 40 y and older who have received a mammogram within the preceding 2 y to 70% … (rates) remain far below this goal among Korean American women… . We partnered with 2 community clinics in Koreatown, Los Angeles County, that offer free mammograms… . with the common goal to increase annual rescreening among Korean American women. |

| Adoption—setting | Not reporting percent of settings approached that participated based on a valid denominator. Not reporting recruitment of setting details and exclusion criteria (e.g., only picking optimal sites). | Use of a valid denominator at the setting level can be challenging. Use any information you can. At minimum, report the sampling frame from which your settings were selected and percentage of participation. | Collard et al.27 All primary schools in the Netherlands were eligible for inclusion in the study. From the 7000 primary schools throughout the Netherlands, 520 primary schools (7%) were randomly selected from a database and invited to participate in the iPlay study by means of an information flyer. The inclusion criteria for the primary schools were (1) they had to be a regular primary school, (2) they had to provide physical exercise lessons twice/wk, and (3) they had to be willing to appoint a contact person for the duration of the study. Of the 520 schools, 370 (71%) did not respond to the invitation, 105 (20%) were unwilling to participate, and 45 (9%) were willing to participate in the study. The main reason why schools were not willing to participate was a lack of time (55%). Other reasons included “already participating in another project” (8%), “injury prevention is not relevant” (10%), or “no interest” (8%). |

| Adoption—staff | Not reporting characteristics of staff participants compared with nonparticipants. Not reporting on recruitment and exclusion of staff characteristics, and experience or expertise. | Report on any criteria you can, even if it is just 1 characteristic. This allows for others to assess to some degree the representativeness of staff who participate. | Toobert et al.28 As shown in Figure 1, a total of 59 practitioners were recruited for this project of 84 approached (70%). These physicians represented 15 practices, of 18 approached (83%). Most physicians specialized in family practice or internal medicine, and about a third were female. Participating (n = 59) and nonparticipating (n = 25) physicians did not differ significantly on any of the characteristics measured (medical specialty, percentage female, and affiliation), as can be seen in Table 1. |

| Implementation | Not reporting adaptations made to interventions during study. Not reporting on costs and resources required. Not reporting differences in implementation or outcomes by different staff. | Report any changes that made the intervention easier to delivery or to fit into real world settings. Remember, this is not fidelity. | Cohen et al.24 Research teams made changes to proposed interventions to accommodate practices’ circumstances. For example, a number of projects intended to have practices administer a health risk assessment as part of the intervention and found that the proposed delivery method (e.g., kiosk) did not fit well with a practice’s routines. The change was to using a tablet PC. |

| Maintenance—individual | Not reporting results of long-term broader outcomes, such as quality of life or unintended outcomes. | Reporting broader outcomes provides a context in which to evaluate the long-term primary outcome results. | Toobert et al.29 As shown in Table 3, despite a pattern of greater improvement for the treatment condition on the main-outcome subscale(s), the overall repeated measures MANCOVA for the quality of life (DDS) regimen-related and interpersonal distress scales did not reach the P < .05 level of significance for the treatment compared with control conditions. |

| Maintenance—setting | Not reporting if program is still ongoing after ≥ 6-mo follow-up. Not reporting on how program or policy was adopted. | Report whatever information you have available in terms of settings continuing to deliver your intervention after the study is completed. | Li30 All participating centers expressed strong interest in continuing the program. Since the completion of the study, 5 centers continued offering a tai chi class, and 1 was waiting on instructor availability. |

Note. CI = confidence interval; CONSORT = Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; DDS = Diabetes Distress Scale; IVRS = interactive voice response system; MANCOVA = multivariate analysis of covariance; OR = odds ratio; RE-AIM = Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance

The most prevalent problems identified were confusing the definitions of reach and adoption, and not reporting on or using a valid denominator for reach or adoption. Reach is the absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of individuals who are willing to participate in a given initiative, intervention, or program. Adoption is the absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of settings and intervention staff willing to initiate a program or policy in their setting. Sometimes identifying the correct denominator can be challenging. The denominator answers the question: how many people are eligible to participate? To calculate a valid denominator, first, enumerate all potential participants in the target population. Then, document reasons for and the number of exclusions by the investigators or program. The remaining individuals are the denominator. For example, the denominator for an intervention in a health care organization targeting individuals with a specific health condition would be all individuals served by the organization diagnosed with the condition of interest. Calculating a valid denominator for policy interventions can be challenging. The denominator is the number of individuals who would ideally be affected by the policy.

Reporting on participation rates and comparing characteristics of participants and nonparticipants at both the individual and setting levels are vital to understanding the context of a study. There are several ways of estimating reach. It is often possible to use either census data, data from national representative surveys, such as National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, or information from public agencies or marketing organizations to provide an estimation of the number of eligible persons or organizations in a given geographic area. Two important recommendations are (1) to report the exclusion rate (and exclusion criteria), and (2) state specifically if the sample was drawn from a “denominator” of some exhaustive list versus approaching only those individuals or settings estimated to be the most interested, motivated, or best able to participate.

DISCUSSION

We reviewed the empirical published literature to report on the extent to which and how the RE-AIM framework was used. We found an increasing number of articles using the RE-AIM framework, but few that reported on all 5 dimensions or all criteria within a RE-AIM dimension. Reach was the most frequently reported on RE-AIM dimension, but also the most incorrectly used (Table 2). This was not surprising, in that describing study participants to some degree is mandated by journals. Within each RE-AIM dimension, a small percentage of articles addressed all reporting criteria. Qualitative methods were rarely used to understand the results for any of the RE-AIM components.

Comparing the results of this review to that conducted by Glasgow et al. in 2004,31 who used RE-AIM criteria to evaluate health behavior intervention publications in select health behavior change journals from 1996 to 2000, revealed noticeable increases in the reporting on RE-AIM dimensions. In the 2004 review, a mean of 14% of the publications reported on representativeness of the participants compared with 58.5% in the present review. Reporting on the representativeness of settings also increased over time (2.0% compared with 37.9%) and maintenance at the setting level (2.0% compared with 41.2%).

We used a comprehensive list of criteria (34 items) to evaluate the articles included in this review. Although some might argue for an abbreviated list of criteria, we felt all the criteria were important and were interrelated for understanding context. With the passage and implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and greater emphasis on comparative effectiveness research, it was not only important to know the percentage of participation, but equally important to know who participated and why they participated to better interpret outcomes. Increased reporting using the RE-AIM framework would allow for results to be interpreted not only in terms of their immediate impact, but also concerning their potential for generalization.3

A recent review of grant proposals assessing the extent to which the RE-AIM framework was fully applied identified similar results in terms of problems with understanding some the definitions of the RE-AIM dimensions and the application of the framework.21 Because similar problems related to reach and adoption appeared consistent from the proposal development and submission stage to reporting study findings, it was apparent that more education and instruction is needed on how to apply some of the dimensions of RE-AIM. Although these 2 areas have room for improvement, there were other more recently promoted and recommended criteria (such as intervention cost and adaptations made to the intervention) that were reported increasingly more often. The shift in emphasis of cost and adaptation criteria might reflect the more recent emphasis on translational research. Correct application of adoption, implementation, and setting-level maintenance criteria is important and relevant to selecting evidence-based interventions with potential for broad public health impact.

Limitations of this report included potential underestimation of the number of articles eligible. We limited our search to those articles that specifically stated use of RE-AIM. From our initial review of the literature, we found 40 articles with our search scheme that were excluded because they did not explicitly mention RE-AIM. Some portion of these articles might have presented their findings in a way that RE-AIM was obvious but not stated. Another limitation was that we evaluated each article using the most current RE-AIM criteria. This could have negatively biased the summary scores for the earlier articles published on RE-AIM. We also only included articles up to the end of 2010. As of this writing, there were at least 56 articles published since then. Strengths included high agreement between reviewers, comprehensive search criteria, clear enumeration of criteria, and recommendations for reporting.

In summary, RE-AIM was used initially by a small group of investigators primarily to evaluate health behavior research. Today, it is used in the planning stages, to assess progress, report results, and review the literature in diverse health areas. The point of this review was not to criticize uses of the framework to date, but to show its evolution and provide guidance and resources for its use (Tables 1 and 2; see also http://www.re-aim.org and http://centertrt.org/?p=training_webtrainings).

We do not propose that all RE-AIM dimensions must be used in all studies, but recommend that investigators be clear on what elements of the framework are used and why these were selected or not. Reviewers and colleagues have raised the issue of how many RE-AIM dimensions should be addressed in a study.21,32 Our position is that, in general, the more comprehensively a study could report on RE-AIM issues, both within and across the 5 dimensions, the better. Reporting across dimensions provides far greater value because results at 1 level (e.g., increasing reach) could have unintended consequences at other levels or on other issues within the same dimension (e.g., decreased effectiveness or implementation). The various dimensions are individually important, but interdependent, and producing results at all levels is necessary to produce public health impact. Having said this, it is not always possible (it is always desirable) to address all dimensions. For example, in 1-year grant funding, it does not make sense to “require” reporting on long-term maintenance.

We hope that the explicit statement of criteria for RE-AIM dimensions, along with the lessons learned, discussion, and examples provided will help future researchers who wish to apply the framework. RE-AIM is a planning and evaluation model that can help address the complex and challenging health care issues we face today. As the health environment continues to change, questions such as “which complex intervention for what type of complex patients, delivered by what type of staff will be most cost effective, under which conditions and for what outcomes” will need to be answered. RE-AIM provides a structured manner to assist in answering these questions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Barbara McCray for assistance in preparing this article.

Human Participant Protection

The study was approved by the Institute for Health Research institutional review board.

References

- 1.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(8):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zerhouni EA. Clinical research at a crossroads: the NIH roadmap. J Investig Med. 2006;54(4):171–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green LW, Glasgow RE. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: issues in external validation and translation methodology. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(1):126–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health Program and Planning: An Educational and Ecolgocial Approach. 4th ed New York, NY: McGraw Hill Higher Education; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaglio B, Glasgow RE. Evaluation approaches for dissemination and implementation research. : Brownson RC, Colditz G, Procter E, Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health. 1st ed New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012:327–358 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glasgow RE, Linnan LA. Evaluation of theory-based interventions. : Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th ed San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008:487–508 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler R, Glasgow RE. A proposal to speed translation of healthcare research into practice: dramatic change is needed. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(6):637–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunton GF, Lagloire R, Robertson T. Using the RE-AIM framework to evaluate the statewide dissemination of a school-based physical activity and nutrition curriculum: “Exercise Your Options.” Am J Health Promot. 2009;23(4):229–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farris RP, Will JC, Khavjou O, Finkelstein EA. Beyond effectiveness: evaluating the public health impact of the WISEWOMAN program. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):641–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eakin EG, Bull SS, Riley K, Reeves MM, Gutierrez S, McLaughlin P. Recruitment and retention of Latinos in a primary care-based physical activity and diet trial: the Resources for Health study. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(3):361–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasgow RE, Gaglio B, France EKet al. Do behavioral smoking reduction approaches reach more or different smokers? Two studies; similar answers. Addict Behav. 2006;31(3):509–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toobert DJ, Strycker LA, Glasgow RE, Barrera M, Jr, Angell K. Effects of the Mediterranean lifestyle program on multiple risk behaviors and psychosocial outcomes among women at risk for heart disease. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29(2):128–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas JS, Iyer A, Orav EJ, Schiff GD, Bates DW. Participation in an ambulatory e-pharmacovigilance system. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(9):961–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King DK, Glasgow RE, Leeman-Castillo B. Reaiming RE-AIM: using the model to plan, implement, and evaluate the effects of environmental change approaches to enhancing population health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2076–2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klesges LM, Estabrooks PA, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Glasgow RE. Beginning with the application in mind: designing and planning health behavior change interventions to enhance dissemination. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29(suppl):66–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jilcott S, Ammerman A, Sommers J, Glasgow RE. Applying the RE-AIM framework to assess the public health impact of policy change. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(2):105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasgow RE, Dickinson P, Fisher Let al. Use of RE-AIM to develop a multi-media facilitation tool for the patient-centered medical home. Implement Sci. 2011;6(10):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glasgow RE, Askew S, Purcell Pet al. Use of RE-AIM to address health inequities: application in a low-income community health center based weight loss and hypertension self-management program. Transl Behav Med. Epub ahead of print February 13, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RS, Purcell EP, Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Benkeser RM, Peek CJ. What does it mean to “employ” the RE-AIM model? Eval Health Prof. 2013;36(1):44–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akers JD, Estabrooks PA, Davy BM. Translational research: bridging the gap between long-term weight loss maintenance research and practice. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(10):1511–1522, e1–e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, King DKet al. Robustness of a computer-assisted diabetes self-management intervention across patient characteristics, healthcare settings, and intervention staff. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(3):137–145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF, Etz RSet al. Fidelity versus flexibility: translating evidence-based research into practice. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(5 suppl):S381–S389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Strycker LA. Implementation, generalization and long-term results of the “choosing well” diabetes self-management intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maxwell AE, Jo AM, Chin SY, Lee KS, Bastani R. Impact of print intervention to increase annual mammography screening among Korean American women enrolled in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. Cancer Detect Prev. 2008;32(3):229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collard DC, Chinapaw MJ, Verhagen EA, van MW. Process evaluation of a school based physical activity related injury prevention programme using the RE-AIM framework. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10(11):86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toobert DJ, Strycker LA, Glasgow RE, Bagdade JD. If you build it, will they come? Reach and adoption associated with a comprehensive lifestyle management program for women with type 2 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Barrera M, Jr, Ritzwoller DP, Weidner G. Long-term effects of the Mediterranean lifestyle program: a randomized clinical trial for postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li F, Harmer P, Glasgow Ret al. Translation of an effective tai chi intervention into a community-based falls-prevention program. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(7):1195–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Estabrooks P. The future of health behavior change research: what is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(1):3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Estabrooks PA, Allen KC. Updating, employing, and adapting: a commentary on what does it mean to “employ’’ the RE-AIM model. Eval Health Prof. 2013;36(1):67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]