Abstract

The development of natural gas wells is rapidly increasing, yet little is known about associated exposures and potential public health consequences. We used health impact assessment (HIA) to provide decision-makers with information to promote public health at a time of rapid decision making for natural gas development. We have reported that natural gas development may expose local residents to air and water contamination, industrial noise and traffic, and community changes. We have provided more than 90 recommendations for preventing or decreasing health impacts associated with these exposures. We also have reflected on the lessons learned from conducting an HIA in a politically charged environment. Finally, we have demonstrated that despite the challenges, HIA can successfully enhance public health policymaking.

Many regions of the United States hold large natural gas reserves.1 Colorado is one of the states experiencing rapid natural gas development. Applications for permits to drill rose from 1939 in 2003 to 7870 in 20082,3 and natural gas production rose 110% from 2003 to 2010.4 The natural gas development process can be divided into the well development phase—involving well pad construction, pipeline installation, drilling, hydraulic fracturing, and well completion—and the production phase, when natural gas is routed into pipelines, compressed, processed, and distributed to end users. Concerns about potential drinking water contamination from hydraulic fracturing have dominated public discourse on natural gas development and public health.5–10 We conducted a health impact assessment (HIA) to systematically and comprehensively evaluate the possible health effects of natural gas development in a residential community in western Colorado.

BATTLEMENT MESA HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Battlement Mesa is a community of 5000 people in western Colorado. In 2009, a natural gas operator announced plans to develop 200 natural gas wells in the community, some of which would be approximately 500 feet from homes. The well development phase would be 5 years, followed by a 20- to 30-year production phase.

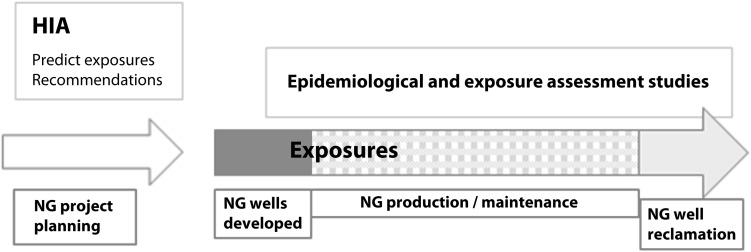

Battlement Mesa residents petitioned their county commissioners for a health assessment to precede the issuing of permits to the natural gas operator.11 The county then contracted us to conduct an HIA, scheduled to be completed in a limited time period related to the anticipated dates of operator permits to drill. An HIA includes both quantitative and qualitative analysis of available data and literature to make reasoned recommendations to prospectively advance public health.12,13 Usually, an HIA is conducted before exposures occur, with the goal of providing public decision makers with insight into the potential health consequences of impending projects, policies, or programs. This contrasts with public health research methods that assess exposures and health outcomes during or after an activity occurs (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Timeline of natural gas impacts evaluation methodologies: Battlement Mesa, CO.

Note. HIA = health impact assessment; NG = natural gas.

We employed a previously described 6-step HIA process.14–16 We included a baseline characterization of the population’s and the community’s health. Using the World Health Organization’s definition of health as a state of “complete physical, mental, and social well-being”17 and understanding that living environment is a determinant of health,18 we addressed a wide range of potential exposures from natural gas development and the subsequent effects these exposures could have on public health. Because we conducted the HIA before the project had begun, site-specific data for exposures were not available; instead we used exposure data from other local sites where natural gas development had occurred and medical literature to describe the known health effects of such exposures. Throughout the HIA process, we worked closely with county public health professionals and received technical guidance and support from experienced HIA practitioners. The full HIA and supporting documents are available on the county Web site.19

Approach and Findings

We invited all interested parties to participate as stakeholders. Stakeholders included 2 citizen groups, individual residents of Battlement Mesa, the company that owns the Battlement Mesa surface rights, the operator proposing the natural gas development, an industry association, and the state health department. At the initial 9 stakeholder meetings, we provided a detailed description of the HIA process, solicited input for health and exposure concerns, discussed use and analysis of data, and provided updates on the HIA’s progress. Four of these meetings were with the natural gas operator, and we focused on developing a clear understanding of natural gas development and extensive reviews of their proposed plans for development. We also discussed in great detail potential public health hazards and the natural gas operator’s plans for mitigating potential exposures.

Following the release of the first draft HIA and a comment period, 4 additional stakeholder meetings were held with the citizen’s groups, the state health department, the natural gas operator, and the industry trade association, which focused on reviewing public comments on the HIA and discussion of our responses to those comments. At each separate stakeholder meeting, we took detailed notes, which we made available to all participants and stakeholders via the county Web site (data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

We also met weekly with the county environmental health manager throughout the HIA process and provided regular updates to the commissioners at public county commission meetings. The county commissioners directed us to limit our assessment to the potential health impacts of the proposed natural gas development on the Battlement Mesa community and not to consider impacts of natural gas development beyond the community boundaries. We determined the site-specific plans for the natural gas development from detailed information the operator provided us, 10 PowerPoint presentations the operator gave to the community, and the surface use agreement between the operator and the community landowner.20,21 The scope of exposures for the HIA to consider included the stakeholders concerns, which we collected during the initial public meetings and information from community surveys and focus group meetings the county health department previously conducted. We systematically reviewed all stakeholder input and determined that there were 8 major areas of public health concern: health effects from air emissions, water contamination, truck traffic, noise and light pollution, accidents and malfunctions, strain on health care systems, psychosocial stress associated with community changes, and housing value depression.

Our baseline assessment of the Battlement Mesa Community demonstrated that 46% of the residents were younger than 18 years or older than 65 years, subgroups known to be more susceptible to a variety of exposures.22–25 We found that the community was as healthy as or healthier than other Coloradans when we compared births, deaths, cancer incidence, and hospitalizations. Baseline assessment of the community indices indicated that crime, school enrollment, and sexually transmitted infection had rapidly increased in the previous 5 years in relation to the natural gas development that had occurred in the county outside the boundaries of their community.

Using quantitative and qualitative assessments of available information, we found that Battlement Mesa residents could potentially experience health effects associated with (1) exposure to chemical air emissions; (2) exposure to industrial operations, including traffic, malfunctions, and noise pollution; and (3) changes to community character and economic impacts. We determined that impacts were most likely to occur during the well development period, with lesser potential impact throughout the production period. Table 1 shows projected exposures and potential associated health effects.

TABLE 1—

Predicted Project Impacts and Potential Health Effects: Battlement Mesa, CO

| Predicted Project Impacts | Potential Health Effects |

| Chemical exposures | |

| Air emissions from well development (likely to occur but concentrations at homes unknown) | Probable: |

| Volatile organic compounds Carbonyls | Short-term health effects (headache and other neurologic symptoms; airway and mucous membrane irritation) |

| Polyaromatic hydrocarbons | Possible: |

| Nitrogen oxides Diesel emissions | Long-term health effects (cancer, birth defects); exacerbation of chronic disease (asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiac disease) |

| Contamination of water sources (low likelihood of occurrence) | Unlikely: |

| Improper well installation or spills resulting in contamination | Short- and long-term health effects owing to contaminants in secondary water supply |

| Industrial operations | |

| Industrial truck traffic on residential roads (likely to occur) | Probable: |

| Disruption of residential road use | Increased risk of traffic accidents |

| Disruption of walking and bicycle routes | Decreased use of walk and bicycle routes |

| Diesel emissions | Possible: |

| Health effects of diesel exhaust | |

| Accidents or malfunctions (minor incidents likely to occur; major incidents unlikely to occur) | Probable: |

| Well pad incidents (spills, fires, explosions) | Stress or anxiety owing to minor or major incidents |

| Pipeline incidents (explosions) | Unlikely: |

| Health or safety effects because of exposure to industrial chemicals, fires, explosions | |

| Noise pollution (likely to occur) | Probable: |

| Drilling and completion operations | Noise-related stress, sleep disturbance |

| Flaring | Possible: |

| Truck traffic | Cardiovascular effects |

| Community changes | |

| Community wellness (likely to occur) | Probable: |

| Perceived decline in community livability | Stress; decline of social cohesion |

| Decreased appeal of outdoor amenities and experience (i.e., well pad on golf course, disruption of bicycle paths by truck traffic) | Barriers to outdoor physical activities Unlikely: |

| Inflow of itinerant workers to Battlement Mesa | Notably increased rates of crime, sexually transmitted infections, and substance abuse |

| Economic: property value loss (likely to occur) | Probable: |

| Stress, anxiety because of property value losses | |

At the county commissioners’ request, we provided them with more than 92 specific recommendations designed to promote the health of Battlement Mesa residents for the duration of the natural gas development project (data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). By the commission’s request, these specific recommendations did not include an assessment of cost or feasibility of implementation. Most recommendations addressed the 3 main categories of projected impacts and outcomes (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Recommended Health Promotion Measures and Targeted Public Health Outcomes: Battlement Mesa, CO

| Recommended Prevention and Monitoring Measures | Targeted Public Health Outcome |

| Reduce potential for chemical exposures | |

| Contaminant control measures | Improved physical health: Short-term health (headaches, upper respiratory irritation); long-term health (cancer, adverse birth outcomes, cardiac disease, pulmonary disease) |

| Pollution prevention: Operator uses all existing technology to decrease emissions and adopt new technology as available | Document levels of air and water contaminants: Provide information for continual process improvement; provide regulators and public health officials with information to maintain healthy environment |

| Air and water monitoring: Operator monitors air and water during all operations; all results publicly available; county continues ambient air monitoring | |

| Public health monitoring | Document physical health: Short-term health (headaches, upper respiratory irritation); long-term health (cancer, adverse birth outcomes, cardiac disease, pulmonary disease) |

| Health monitoring system: County supports a baseline and ongoing monitoring system of selected physical and mental health indicators | |

| Reduce exposure to industrial operations | |

| Public safety measures | Improve traffic safety: Motor vehicle accidents (including bicycle and pedestrian accidents) |

| Traffic control: Operator develops industrial haul routes to remove industrial traffic from residential roads | Improve physical activity: Use of outdoor amenities for physical activity; |

| Industrial safety: Operator and county monitor industrial operations, near misses, and minor incidents; operator develops detailed emergency response plan in conjunction with local emergency responders | Prevent industrial accidents: Early mitigation of safety hazards to reduce acute health outcomes related to fires, explosions, and uncontrolled emissions; injury related to catastrophic incidents |

| Industrial noise: Operator reduces industrial noise using best available technology | Improve physical and mental health: Decreased stress and improved cardiovascular health related to less noise pollution |

| Support residential character of the community | |

| Community wellness measures and monitoring | Improve community cohesion: Social or psychosocial stress and anxiety; community engagement and empowerment |

| Community advisory board: All stakeholders develop and participate in community advisory board meetings to foster interactive communication and problem solving | Document community wellness: Property values, substance abuse, sexually transmitted infection, crime, and educational experience |

| Community wellness monitoring: County fund baseline and ongoing monitoring system of selected community wellness indicators | |

Quantitative Assessment of Chemical Exposures

Because all stages of natural gas development are known to produce a variety of air emissions, air pollutant levels are likely to increase in Battlement Mesa as a result of the natural gas development project.7,26–28 Air emissions from the wells, production tanks, compressors and pipelines, and maintenance operations include volatile organic compounds (VOCs), methane, and other hydrocarbons.28 Emissions from combustion associated with truck traffic, generators used to power drilling rigs, hydraulic fracturing, and flaring include particulate matter, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other hydrocarbons, VOCs, sulfur oxides, and nitrogen oxides.27–29 Local air emission studies conducted in Garfield County, Colorado, indicate that the highest VOC and hydrocarbon emission levels occur during well completion operations, when fluids and gas “flow back” to the surface after hydraulic fracturing.30–32 Emissions inventories indicate that ambient VOC and benzene increases of 40% and 38%, respectively, from 1996 to 2007 are likely associated with the large increase in natural gas development in the county.32,33

The Colorado River is the primary drinking water source for Battlement Mesa. The water intake for the community is upstream of the proposed project, making it unlikely that the project would affect this source. The community’s secondary water source, 4 groundwater wells, has never been used. The risk of contamination of these wells is not known, because the hydrology of the area has not been characterized. Because it was unlikely that Battlement Mesa residents would be exposed to contaminated drinking water as a result of the project, we did not consider it likely that health effects related to this pathway would occur.

We used standard Environmental Protection Agency screening-level human health risk assessment methods to estimate health risks from residential exposures to natural gas development air emissions. On the basis of local county monitoring data and the operator’s air sampling data, our results indicated that those living close to the wells would have an increased risk of noncancer health effects from subchronic exposures (20 months) to trimethylbenzenes, alkanes, and xylenes during the relatively short-term, but high-emission, well completion period. Our findings also indicated that there would be a small increased lifetime excess cancer risk (10 × 10−6) for those living close to wells compared with the risk for those living farther from wells (6 × 10−6), primarily because of benzene and ethylbenzene exposures.34

Residents living within a half mile of well development adjacent to Battlement Mesa have reported short-term symptoms such as headaches, nausea, upper respiratory irritation, and nosebleeds associated with odor events occurring during well completion operations.35 These symptoms are consistent with known health effects of risk drivers in the risk assessment.36–40 We determined that some residents living close to well development sites would probably experience similar short-term effects as a result of the project.

In Colorado, operators are required to place wells 150 feet from occupied buildings in low-density residential areas and 350 feet in high-density areas, such as Battlement Mesa.41 There are no published peer-reviewed studies documenting that these current regulatory set-back distances from wells to residences are sufficient to protect the public from chemical exposures. The unique nature of each well pad would make it difficult to determine 1 protective set-back distance for all residences. Therefore, many of our specific recommendations were directed at the use of best available technology and best management practices to reduce air emissions to lowest possible levels from all sources, especially sources associated with well completion operations.

Many of our specific recommendations also focused on continuing monitoring of air emissions, determination of threshold values at which operations would be required to shut down, and mechanisms for health monitoring. These measures would help protect short-term and long-term health and provide public health officials and regulators information needed to maintain a healthy environment (data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Qualitative Assessment of Industrial Operations

The operator gave us their traffic analysis report, which indicated that expected truck traffic would be 40 to 280 truck trips per day per pad. In addition, an average of 120 to 150 workers per day would commute into the community. Because Battlement Mesa does not house other industrial activities and commercial activities are minimal, this change in traffic patterns would represent a consequential change.

Traffic studies indicate that numbers of injuries and fatalities are directly related to vehicle volume.42–44 Severity of injuries is directly related to vehicle speed and size. Thus, an increase in heavy and light vehicle traffic in Battlement Mesa would present an increased safety risk for the community. Industrial traffic would use the same roads that children use for walking or bicycling to school and bus stops, thus making children a susceptible population. Additionally, traffic could cause some residents to decrease the use of bicycle or walking paths, possibly decreasing fitness levels.45–48

Colorado laws define chemical or waste spills as reportable when they are greater than 5 barrels.41 Review of the Colorado State regulatory database indicated that the natural gas industry reports spills at a rate of 6 per 100 permit applications; therefore, approximately 12 reportable spills would likely occur during the natural gas development project in Battlement Mesa, many of which would be minor and have little community impact.35 We concluded that infrequent industry-related spills were likely to occur.

Significant industrial malfunctions can occur, although they are not common. In Garfield County, there were 21 fires, loss of well control, and explosions reported to the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission from January 1997 to August 2010. This number is small relative to the more than 5000 wells developed in that period. We therefore concluded that catastrophic events were possible, but unlikely.

We determined that anxiety and stress related to the risk of industrial accidents would likely continue throughout the well development period on the basis of residents’ public comments to the HIA. Although unlikely to occur, major malfunctions releasing toxic chemicals into the air could lead to airway compromise and other acute effects, especially in individuals who are at risk because of preexisting pulmonary conditions.49–51 Wildfires and explosions could represent safety hazards to residents as well as workers.

In Colorado, natural gas operators are required to maintain daytime and nighttime noise levels below 55 decibels and 50 decibels, respectively, measured 350 feet from the source.41 The operator gave us noise-monitoring data from another drill site. These data indicate that noise levels associated with drilling operations were 60 decibels at 500 feet in one direction and 69 decibels at 1000 feet in another direction; with noise blankets on the generators, levels were, respectively, 56 and 65 decibels. Noise data from truck traffic, hydraulic fracturing, and flaring were not available, but residents experiencing these activities at other sites reported that noise from these operations can be intrusive. Therefore, we concluded that noise levels were likely to increase during the well development period and that the mitigations tested during drilling were not sufficient to meet Colorado regulatory standards.

Chronic noise in the range of 30 to 70 decibels has been associated with sleep disturbance, fatigue, impaired cognition, mood changes, diminished school performance, hypertension, and heart disease.52–55 We concluded that noise related to drilling, hydraulic fracturing, flaring, and traffic could be in this range, resulting in health impacts.

Because industrial traffic would pose an ongoing safety hazard throughout the development period, 1 of our primary recommendations to the commissioners was that the operator be instructed to build roads to shunt industrial traffic outside the community and off community roads, thus reducing safety hazards, diesel emissions, and noise associated with industrial traffic.

Our other specific recommendations included that the natural gas operator and the county work together to develop robust emergency response plans and systems to monitor and respond to safety concerns, near misses, and minor incidents to support the early mitigation of safety hazards and to decrease the likelihood of injury and acute health effects related to major malfunctions.

We gave further specific recommendations to promote the use of the best available technology to reduce industrial noise from the well pads and to remove trucks from residential areas. These measures would reduce noise-related psychological stress and possible impacts on cardiovascular and mental health (data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Qualitative Assessment of Community Changes

As a result of the previous 6 years’ experience of rapid natural gas development in the county, residents reported concerns about the future livability and character of Battlement Mesa and impacts on crime, substance abuse, sexually transmitted infections, school enrollment, and land values. Changes in several of these measures have been described in small communities associated with natural gas development.56–58 Using state and county databases, we were able to document increases in crime levels, sexually transmitted infections rates, and school enrollment during the years when the county experienced natural gas development growth (2003–2008); however, we determined that this project alone would not likely affect these measures in Battlement Mesa.

Residents reported that the proposed natural gas project in their previously nonindustrial community had already negatively affected their sense of community livability and cohesion; this decline could affect the psychological health of some residents.59 They also anticipated decreased appeal of outdoor recreational opportunities and disrupted use of the community golf course during well pad development on a golf course fairway, potentially affecting the fitness levels of some residents.

A local county study found that properties associated with natural gas development lost an average of 15% of value during well development and did not recover value 2 years after wells were completed.58 Decline of land values was associated with the existence of odors, truck traffic, environmental pollution, visual impacts, and risk perception associated with the uncertainty of the industry use of a particular property. We determined that land values in Battlement Mesa were likely to decline as they had in other parts of the county when natural gas development occurred nearby.

Declining land values could cause residents psychosocial stress, as residents reported in public comments on the HIA. The potential health effects of psychosocial stress should not be discounted: psychosocial stress may be related to cardiovascular health and longevity,60,61 and there is active research in the area of stress-related hormones and heart disease as well as susceptibility to chemical exposures.62–67

Battlement Mesa has been a residential community for several decades, and industrialization will inevitably affect the residential character of the community. Several of our specific recommendations involved the establishment of a community advisory board, consisting of members of the community, the operator, and local officials. This community advisory board would be independent of the industry and would provide a means for frequent and ongoing communication between all parties and a mechanism for developing adaptive management plans. Implementing our recommendations could reduce uncertainty regarding industrial operations, improve communication of newly identified concerns and health impacts, and facilitate timely mitigation. A recent Colorado Oil and Gas Association memo recommending increased engagement of the industry with stakeholder groups supports this recommendation.68 Although a community advisory board would not eliminate all issues stemming from the industrialization of a residential community, strong channels of communication and community empowerment could alleviate some psychological stress and anxiety.

We also made specific recommendations to the county to fund baseline and ongoing monitoring of selected community wellness measures, such as land values, substance abuse, sexually transmitted infections, school climate and enrollment, and the psychosocial status of community members, so that actions to address adverse impacts could be implemented (data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Limited Scope and Possible Impacts Not Assessed

Although the methods of HIA are adaptable to a variety of decision-making scenarios,69 the scope, findings, and recommendations of an HIA are usually situation and site specific. In this case, the Battlement Mesa HIA’s scope was limited to the potential health impacts of a 200-well project on the local community. Because of this limited scope, our HIA did not address other potential impacts of natural gas development on health. A broader scope would have allowed us to address other impacts, such as the following.

Contamination of drinking water source.

Because we found it was unlikely that this particular project would contaminate the Battlement Mesa water sources, we did not fully address potential health effects (and possible preventive measures) associated with drinking water contamination. Reports of thermogenic methane and hydrocarbons in ground water in areas of natural gas development suggest that the potential for ground water contamination exists.5,7,70 In addition, we did not address disposal of wastewater into water treatment facilities, waste injection wells, or waste pits, although potential public health concerns associated with these activities exist.29,71,72

Air pollution in regional air sheds.

We did not address the potential public health impacts of diminished air quality to the regional population. The natural gas industry is the primary source of nonbiogenic VOC and nitrogen oxides in the county.32 County monitoring demonstrates that ozone levels are approaching current national ambient air quality standards of 75 parts per billion.30–33 Elevated wintertime ozone levels reaching 100 to 125 parts per billion have been demonstrated in several rural communities where natural gas development is occurring.73–76 Furthermore, industry contributions to particulate matter, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and heavy metals may also add to negative health impacts, although there has been relatively little research conducted in these areas in regard to natural gas development.

Methane emissions.

We did not address the public health implications of natural gas development contribution to greenhouse gases and climate change. Methane is the primary component of natural gas and a more potent greenhouse gas than is carbon dioxide.27 The release of methane to the atmosphere from natural gas development may offset decreased carbon dioxide emissions on the consumption end.77,78

Positive impacts.

We did not fully evaluate the potential positive impacts of natural gas development on rural communities. Development of the natural gas industry can directly and indirectly support employment, infrastructure, access to health care, and donations to local communities.79–82 The county would likely share positive economic impacts of the project, and therefore these are not likely to be noticeably realized in Battlement Mesa. An HIA of larger scope could more fully assess the possible positive health effects of natural gas development.

CHALLENGES, LESSONS LEARNED, AND UTILITY

Although the Battlement Mesa HIA evaluated the possible health effects of a small natural gas project in a small community in western Colorado, there were many factors that caused an escalation of attention from other parts of the country. Locally, the county government requested that the recommendations of the HIA inform the county commission’s conditions on well permits. The county made this request on the basis of public petitions for public health protection, an action unprecedented in Colorado that caused local media to cover all aspects of the HIA process. These articles were then available nationally via the Internet. The HIA also coincided with increased national attention to public health concerns associated with natural gas development operations in the Marcellus Shale. As a result, our HIA has been cited in numerous citizen actions as well as government and legal proceedings in the eastern United States as an example of a comprehensive approach to addressing public health concerns regarding natural gas development.8,83,84 The discussion of potential air, industrial, and community exposures we identified in our HIA have contributed to expanding public dialogue beyond the initial narrow concerns about water contamination owing to hydraulic fracturing.

Challenges

Political conflicts surrounding the process accentuated several limitations of the Battlement Mesa HIA. There was extensive information available to us describing the operator’s plans for natural gas development in Battlement Mesa. The operator, however, did not submit the available plans for permitting and the commitment to these plans was uncertain. For example, the plan to use electric generators for drilling operations was later determined impracticable. Although this uncertainty was of concern to us, the county instructed us to evaluate all available information in lieu of permits. The operator also submitted additional and modified information throughout the HIA process rather than adhering to set deadlines. For example, the operator submitted modified plans for noise mitigation from diesel generators several months after noise impacts had been analyzed. These and other changes created a moving target for our assessment. Ultimately, the uncertainty of the operational plans resulted in citizen frustration and distrust. Also, the operator requested several delays in the HIA’s completion, and the commissioners approved these delays.85,86

Another limitation of the HIA was the stakeholder selection process, which initially seemed fair but ultimately became imbalanced. It was our intention to include all interested parties as stakeholders; however, a narrower stakeholder group may have enabled us to keep the focus on the HIA. As the first round of public comments indicates,19 stakeholders most directly involved in the Battlement Mesa natural gas development project, namely the residents and the operator, were initially interested in addressing all exposures of concern. The more peripheral stakeholders, the industry trade group and the state health department, submitted extensive and contradictory comments that focused almost exclusively on the human health risk assessment, which was an appendix to the HIA. Subsequently, the citizens felt compelled to hire their own risk assessment expert, and they initiated legal action against the operator. The inclusion of the peripheral stakeholders from outside Battlement Mesa caused the focus of the HIA to shift from addressing possible exposures to parties sparring over risk assessment methods.

At the insistence of the peripheral stakeholders, additional meetings were held that did not include all stakeholders. The Battlement Mesa citizen meetings were open public meetings and included industry and operator representatives, the state health department, and any other interested parties. Conversely, meetings with the industry trade group and the state health department were closed and did not include citizen representatives. These closed-door meetings contributed to a mistrust of the industry and the HIA process.

Finally, elected public officials, who were inevitably subject to political pressures, controlled funding for our HIA. During the course of the HIA process, a county election resulted in a change in the make-up of the commission. A commissioner who had supported public health initiatives was replaced by a commissioner who favored less industry regulation and who repeatedly stated in public meetings that the HIA was “biased.” Operationally, the industry was granted several requests for extension of the HIA process. Because the county commissioners held fiduciary control over the project, we were obliged to extend the process. This allowed time for the industry trade group and the operator’s hired consultants to submit public comments that extensively criticized the HIA. Ultimately, the commissioners instructed us to not “finalize” the HIA, citing rising costs and the politicization of the process. Neutral third-party funding would have permitted us to better control the project and the process. Although political forces in many ways commandeered the HIA process, we consider the HIA conclusions and recommendations to be sound, fair, and balanced.

Lessons Learned

There are many lessons to be learned from our experience with the Battlement Mesa HIA. An impartial third party should fund an HIA that has implications for high-stakes political manipulation. As part of setting the scope of the HIA, all stakeholders should provide the information to be evaluated and adhere to mutually agreed on deadlines.

All stakeholders should agree on procedures for evaluation of new information and the costs of such additional evaluation. Stakeholders should be vetted carefully so that those whose interests are inconsistent with the goals of the HIA are not given a platform from which to undermine the process. Stakeholder meetings should be open to all stakeholders, so that all participants have equal access to the dialogue and to information being exchanged at the meetings.

Utility of the Health Impact Assessment

Despite the missteps of the Battlement Mesa HIA process, we believe we accomplished the important objective of elevating public health into many levels of natural gas policy discussions. Although our report was never finalized, we believe that the current draft of the Battlement Mesa HIA provides substantial and valuable guidance for local decision makers to protect public health. To date, the operator has not submitted permits or initiated natural gas development activities in Battlement Mesa, and the county commissioners have recently approved expanded air monitoring for Battlement Mesa and other natural gas development areas.87

Our HIA has also informed the broader public and state and national policymakers about the spectrum of environmental exposures potentially associated with natural gas development, as news reports, state policy hearings, and recent national conferences evidence.6,8,10,88–91

Conclusions

To fully understand the health impacts associated with natural gas development, extensive research in environmental emissions, community impacts, and health outcomes should be conducted. Regulators, legislators, and planners, however, must make real-time decisions and are often unable to wait for science to catch up. In the absence of good data on the effects of natural gas development on their citizenry, concerned community governments have been invoking temporary moratoriums that may impede even potentially safe natural gas development.92–94 In such circumstances, when definitive scientific data are incomplete, HIA methods can provide guidance to community leaders for the inclusion of health in the decision-making process.95

The methods used in this HIA can serve as a model for public health practitioners evaluating the health impacts of natural gas–related industrialization of residential communities. Public health researchers and practitioners embarking on such an enterprise are encouraged to obtain independent funding and to be cognizant of the social, political, and economic context in which they insert the voice of public health. Adherence to a clear set of goals and objectives and an open and transparent information-gathering and analysis process are crucial for stakeholder involvement and acceptance of the final product.

Acknowledgments

The Battlement Mesa health impact assessment was funded by a contract from the Garfield County Board of County Commissioners. Technical assistance was funded by the Health Impact Project, a collaboration of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Pew Charitable Trusts. In kind support was also provided by the Colorado School of Public Health.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because data were obtained from secondary sources.

References

- 1.US Energy Information Agency. Annual energy review 2010. 2011. Available at: http://www.eia.gov/totalenergy/data/annual. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 2.Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission. December 2003 Staff Report. 2003. Available at: http://cogcc.state.co.us. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 3.Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission. December 2008 Staff Report. 2008. Available at: http://cogcc.state.co.us. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 4.Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission. Annual Production Reports. 2011. Available at: http://cogcc.state.co.us/COGCCReports/production.aspx?id=MonthlyCoalGasProdByCounty. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 5.Osborn SG, Vengosh A, Warner NR, Jackson RB. Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(20):8172–8176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100682108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lustgarten A, Kusnetz N. Science Lags as Health Problems Emerge Near Gas Fields. ProPublica; September 16, 2011. Available at: http://www.propublica.org/article/science-lags-as-health-problems-emerge-near-gas-fields. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 7.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Groundwater Investigation—Pavillion. 2010. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/region8/superfund/wy/pavillion. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 8.New York State Assembly. Hearing on the Potential Public Health Impacts of Hydraulic Fracturing. 2011. Available at: http://www.gasdrillingtechnotes.org/uploads/7/5/7/4/7574658/potential_stressors_human_health_ld__2011.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 9.Clarke CR. Gas well blowout. Frack water gushes into creek; families evacuate. Williamsport SunGazette. April 21, 2011.

- 10.Mouawad J, Kraus C. Dark side of natural gas boon. New York Times. December 8, 2009: B1.

- 11.Garfield County. Battlement Mesa HIA Background. 2012. Available at: http://www.garfield-county.com/environmental-health/battlement-mesa-health-impact-assessment-background.aspx. Accessed May 4, 2012.

- 12.Pew Research Center. Health Impact Assessment: Bringing Public Health Data to Decision Making. 2011. Available at: http://www.healthimpactproject.org/resources/policy/file/health-impact-assessment-bringing-public-health-data-to-decision-making.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 13.Collins J, Koplan JP. Health impact assessment: a step toward health in all policies. JAMA. 2009;302(3):315–317. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wernham A. Inupiat health and proposed Alaskan oil development: results of the first integrated health impact assessment/environmental impact statement for proposed oil development on Alaska’s North Slope. EcoHealth. 2007;4(4):500–513. [Google Scholar]

- 15.enHealth Council. Health Impact Assessment Guidelines. Canberra, Australia: National Public Health Partnership; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Health Impact Assessment Consortium. European Policy Health Impact Assessment—A Guide. Policy HIA for the European Union Project; 2004. Available at: http://www.liv.ac.uk/ihia/IMPACT%20Reports/EPHIA_A_Guide.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 17.World Health Organization. Frequently Asked Questions. Available at: http://www.who.int/suggestions/faq/en. Accessed August 10, 2011.

- 18.World Health Organization. Health Determinants. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/health-topics/health-determinants. Accessed August 10, 2010.

- 19.Witter R, McKenzie L, Stinson K Battlement Mesa Health Impact Assessment; September 2010. Available at: http://www.garfield-county.com/public-health/battlement-mesa-health-impact-assessment-ehms.aspx. Accessed October 20, 2011.

- 20.Battlement Mesa Partners. Surface Use Agreement. Battlement Mesa, CO, Battlement Mesa Partners; January 15, 2009.

- 21.Battlement Mesa Service Association. Oil and Gas Committee; 2012. Available at: http://www.battlementmesacolorado.com/oil-gas. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 22.Witter R, McKenzie L, Towle M Health Impact Assessment for Battlement Mesa, Garfield County Colorado; February 2011. Available at: http://www.garfield-county.com/public-health/battlement-mesa-health-impact-assessment-ehms.aspx. Accessed October 20, 2011.

- 23.Faustman EM, Silbernagel SM, Fenske RA, Burbacher TM, Ponce RA. Mechanism underlying children’s susceptibility to environmental toxicants. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(suppl 1):12–21. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly FJ, Dunster C, Mudway I. Air pollution and the elderly: oxidant/antioxidant issues worth consideration. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(40 suppl):70s–75s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00402903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colais P, Faustini A, Stafoggia M et al. Particulate air pollution and hospital admissions for cardiac disease in potentially sensitive subgroups. Epidemiology. 2012;23(3):473–481. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824d5a85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. United States Environmental Protection Agency Outdoor Air—Industry, Business and Home: Oil and Natural Gas Production. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/oaqps001/community/details/oil-gas_addl_info.htmlNo.activity2. Accessed June 6, 2011.

- 27.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Profile of the Oil and Gas Extraction Industry. 2000. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/oaqps001/community/details/oil-gas_addl_info.htmlNo.activity2. Accessed June 6, 2011.

- 28.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Oil and Natural Gas Sector: New Source Performance Standards and National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants Reviews. 2010. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-08-23/pdf/2011-19899.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2011.

- 29.United States Environmental Protection Agency. An Assessment of the Environmental Implications of Oil and Gas Production. A Regional Case Study. 2008. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/sectors/pdf/oil-gas-report.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2011.

- 30.Garfield County Public Health. Garfield County 2008 Air Quality Monitoring Summary Report. 2009. Available at: http://www.garfieldcountyaq.net/default_new.aspx. Accessed October 20, 2011.

- 31.Garfield County Public Health. Garfield County 2009 Air Quality Monitoring Summary Report. 2010. Available at: http://www.garfieldcountyaq.net/default_new.aspx. Accessed October 20, 2011.

- 32.Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Garfield County Emissions Inventory. 2009. Available at: http://www.garfieldcountyaq.net/default_new.aspx. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- 33.Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. 2008 Air Pollutant Emissions Inventory. 2011. Available at: http://www.colorado.gov/airquality/inv_maps_2008.aspx. Accessed September 1, 2011.

- 34.McKenzie LM, Witter RZ, Newman LS, Adgate JL. Human health risk assessment of air emissions from development of unconventional natural gas resources. Sci Total Environ. 2012;424:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission. Inspection/Incident Database. 2010. Available at: http://cogcc.state.co.us. Accessed August 10, 2010.

- 36.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Benzene. 2007 Available at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/TP.asp?id=40&tid=14. Accessed July 20, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Xylenes. 2007 Available at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/TP.asp?id=296&tid=53. Accessed July 20, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Chemicals in the Environment: 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene (C.A.S. No. 95-63-6) 1994. Available at: http://www.epa.gov/chemfact/f_trimet.txt. Accessed July 20, 2010.

- 39.Carpenter CP, Geary DL, Myers RC, Nachreiner DJ, Sullivan LJ, King JM. Petroleum hydrocarbons toxicity studies XVII. Animal responses to n-nonane vapor. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1978;44(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(78)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galvin J, Marashi F. n-Pentane. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1999;1(58):35–56. doi: 10.1080/009841099157412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission. Colorado Oil and Gas Rules and Regulations. 2008. Available at: http://cogcc.state.co.us. Accessed August 10, 2010.

- 42.Nilsson G. Traffic Safety Dimension and the Power Model to Describe the Effect on Speed Safety; 2004. Available at: http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=21612&fileOId=1693353. Accessed August 10, 2010.

- 43.World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety: Time for Action; 2009. Available at: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/report/cover_and_front_matter_en.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2010.

- 44.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts 2008: Large Trucks. Available at: http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/811158.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2010.

- 45.Carver A, Timperio A, Crawford D. Playing it safe: the influence of neighbourhood safety activity—a review. Health Place. 2008;14(2):217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Timperio A, Ball K, Salmon J et al. Personal, family, social and environmental correlates of active commuting to school. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berkowitz RI, Agras WS, Korner AF, Kraemer HC, Zeanah CH. Physical activity and adiposity: a longitudinal study. J Pediatr. 1985;106(5):734–738. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naukkarinen J, Rissanen A, Kaprio J, Pietilainen KH. Causes and consequences of obesity: the contribution of recent twin studies. Int J Obes. 2012;38(8):1017–1024. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caamano-Isorna F, Figueriras A, Sastre I, Montes-Martinez A, Taracido M, Pineiro-Lamas M. Respiratory and mental health effects of wildfires: an ecological study in Galician municipalities (north-west Spain) Environ Health. 2011;10(1):48–56. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morgan G, Sheppeard V, Khalai B et al. Effects of bushfire smoke on daily mortality and hospital admission in Sydney, Australia. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):47–55. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c15d5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vora C, Renvall MJ, Chao P, Ferguson P, Ramsdell JW. 2007 San Diego wildfires and asthmatics. J Asthma. 2010;48(1):75–78. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2010.535885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Babisch W, Ising H, Gallacher JE, Sharp DS, Baker IA. Traffic noise and cardiovascular risk: the Speedwell study, first phase. Outdoor noise levels and risk factors. Arch Environ Health. 1993;48(6):401–405. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1993.10545961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Passchier-Vermeer W, Passchier WF. Noise exposure and public health. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(suppl 1):123–131. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stansfeld SA, Haines MM, Burr M, Berry B, Lercher P. A review of environmental noise and mental health. Noise Health. 2000;2(8):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stansfeld SA, Matheson MP. Noise pollution: nonauditory effects on health. Br Med Bull. 2003;68(1):243–257. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacquet J. Energy Boomtowns & Natural Gas: Implications for Marcellus Shale Local Governments & Rural Communities. Pennsylvania State University; 2009. Available at: http://nercrd.psu.edu/Publications/rdparticles/rdp43.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2010.

- 57.Goldenberg SM, Shoveller JA, Ostry AC, Koehoorn M. Sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing among young oil and gas workers: the need for innovation, place-based approached to STI control. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(4):350–354. doi: 10.1007/BF03403770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.BBC Research & Consulting. Garfield County Land Values and Solutions Study; 2006. Available at: http://www.garfield-county.com/oil-gas/land-value-study.aspx. Accessed August 10, 2010.

- 59.Hancock T. Indicators of environmental health in the urban setting. Can J Public Health. 2002;93(suppl 1):S45–S51. doi: 10.1007/BF03405118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richman LS, Kubzansky LD, Maselko J, Ackerson LK, Bauer M. The relationship between mental vitality and cardiovascular health. Psychol Health. 2009;24(8):919–932. doi: 10.1080/08870440802108926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ortega FB, Lee DC, Sui X et al. Psychological well-being, cardiorespiratory fitness, and long-term survival. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(5):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kubzansky LD, Mendes WB, Appleton A, Adler GK. Protocol for an experimental investigation of the roles of oxytocin and social support in neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and subjective responses to stress across age and gender. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:481–498. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kubzansky LD, Adler GK. Aldosterone: a forgotten mediator of the relationship between psychological stress and heart disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clougherty JE, Kubzansky LD. A framework for examining social stress and susceptibility to air pollution in respiratory health. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(9):1351–1358. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen E, Schreier H, Strunk R, Brauer M. Chronic traffic related air pollution and stress interact to predict biological and clinical outcomes in asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:970–975. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cloughtery J, Levy J, Kubzansky L et al. Synergistic effects of traffic-related air pollution and exposure to violence on urban asthma etiology. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(8):1140–1146. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peters JL, Kubzansky L, McNeely E et al. Stress as a potential modifier of the impact of lead levels on blood pressure: the Normative Aging Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(8):1154–1159. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Colorado Oil and Gas Association. Are We Listening? Industry Messaging Must Change Dramatically; 2011. Available at: http://www.coga.org/pdf_articles/AreWeListening.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 69.Pew Research Center. Health Impact Project. Case Studies. Available at: http://www.healthimpactproject.org/resourcesNo.case. Accessed June 6, 2011.

- 70.Thyne G. Review of Phase II Hydrogeologic Study. Garfield County; 2008. Available at: http://www.garfield-county.com/oil-gas/phase-II-hydrogeologic-characterization-mamm-creek.aspx. Accessed August 10, 2011.

- 71.United States Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Announces Schedule to Develop Natural Gas Wastewater Standards; 2011. Available at: http://yosemite.epa.gov/opa/admpress.nsf/0/91E7FADB4B114C4A8525792F00542001. Accessed June 6, 2011.

- 72.Urbina I. Regulation lax as gas wells’ tainted water hits rivers. New York Times. February 26, 2011.

- 73.Weinhold B. Ozone nation: EPA standard panned by the people. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(7):A302–A305. doi: 10.1289/ehp.116-a302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality. Ozone Nonattainment Information. Available at: http://deq.state.wy.us/aqd/Ozone%20Nonattainment%20Information.asp. Accessed June 6, 2011.

- 75.Fahys J. Ozone raises its ugly head in rural Utah. Salt Lake Tribune. February 17, 2011.

- 76.Air Resources Specialists, Inc. Sublette County Air Toxics Inhalation Report—Final Data Submittal February 3, 2009–March 31, 2010. Fort Collins, CO; 2010.

- 77.Howarth RW, Santoro R, Ingraffea A. Methane and the greenhouse-gas footprint of natural gas from shale formations. Clim Change. 2011;106(4):679–690. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petron G, Frost G, Miller BR et al. Hydrocarbon emissions characterization in the Colorado Front Range: a pilot study. J Geophys Res. 2012;117:19. [Google Scholar]

- 79.The Perryman Group. Drilling for Dollars: An Assessment of the Ongoing and Expanding Economic Impact of Activity in the Barnett Shale on Fort Worth and the Surrounding Area; 2008. Available at: http://www.bseec.org/sites/all/pdf/report.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2011.

- 80.Considine T, Watson R, Entler R, Sparks J. An Emerging Giant: Prospects and Economic Impacts of Developing Marcellus Shale Natural Gas Play. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University; 2009.

- 81.BBC Research & Consulting. Garfield County Socio-Economic Impact Study; 2007. Available at: http://www.garfield-county.com/oil-gas/socioeconomic-impact-study.aspx. Accessed June 6, 2011.

- 82.Kalleberg AL, Reskin BF, Hudson K. Bad jobs in America: standard and nonstandard employment relations and job quality in the United States. Am Sociol Rev. 2000;65(2):256–278. [Google Scholar]

- 83.DiCosmo B. Colorado Study Emerges as Model for Assessing Health Effects of Drilling. Arlington, VA: Inside EPA; April 27, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shonkoff S. Public Health Dimensions of Horizontal Hydraulic Fracturing: Knowledge, Obstacles, Tactics, and Opportunities. Berkeley, CA: University of California; April 17, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Colson J. Antero requests additional month to review Battlement HIA. Glenwood Springs Post Independent. March 20, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Colson J. Final health impact study won’t be out for 4 months. Glenwood Springs Post Independent. December 21, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stroud J. Monitoring for natural gas pollutants to expand. Glenwood Springs Post Independent. April 4, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Environmental Health Sciences, Research, and Medicine. The Health Impact Assessment of New Energy Sources: Shale Gas Extraction. Environmental Health Meeting; April 30–May 1, 2012; Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Activities/Environment/EnvironmentalHealthRT/2012-APR-30.aspx. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 89.Physicians, Scientists, and Engineers for Healthy Energy. Epidemiologic and Public Health Considerations of Shale Gas Production. The Missing Link. Public Health Conference; January 9, 2012. Available at: http://psehealthyenergy.org/events/view/84. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 90.Long S. Health study of natural gas proposed for region. The River Reporter. June 8, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Catskill Mountainkeeper Health Impact Sign on Letter. Available at: http://org2.democracyinaction.org/o/7037/p/dia/action/public/?action_KEY=8056. Published August 30, 2011. Accessed October 1, 2011

- 92.Aguilar J. Erie passes gas drilling moratorium, goes into effect immediately. Boulder Daily Camera. March 7, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hurdle J. Bans on Natural Gas Fracking Spreading. AOL Energy; 2011. Available at: http://energy.aol.com/2011/08/26/bans-on-natural-gas-fracking-spread. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 94.Navarro MNY. Senate approves fracking moratorium. New York Times. August 4, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 95.National Research Council; National Academies of Science. Improving Health in the United States: The Role of Health Impact Assessment. 2011. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13229. Accessed June 30, 2012. [PubMed]