Abstract

Water is essential in providing nutrients, but contaminated water contributes to poor population health. Water quality and availability can change in unstructured situations, such as war.

To develop a practical strategy to address poor water quality resulting from intermittent wars in Iraq, I reviewed information from academic sources regarding waterborne diseases, conflict and war, water quality treatment, and malnutrition. The prevalence of disease was high in impoverished, malnourished populations exposed to contaminated water sources.

The data aided in developing a strategy to improve water quality in Iraq, which encompasses remineralized water from desalination plants, health care reform, monitoring and evaluation systems, and educational public health interventions.

A LONG HISTORY OF UNSTABLE rule, border disputes, and religious strife has created continuous conflict in Iraq, with wars conducted from the beginning of the 20th century to the present. Iraq took part in World Wars I and II. The Persian Gulf wars had three phases: 1980 to 1988, 1988 to 1991, and 2003 to 2010.1,2 The American involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan represent the most sustained combat in the world since the Vietnam War.3

War causes worker shortages, skill-set imbalances, and unreliable distribution of supplies.4 Unstable leadership, disputed territory, and degradation of land and supplies lead to various public health challenges, which Iraq has experienced throughout the past century.5 Iraq’s geography exposes inhabitants to significant threats of waterborne and infectious diseases because of the construction of cities along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and the proximity to neighboring territories that have frequent disease outbreaks. In the mid-20th century, during a hiatus between World War II and the Persian Gulf wars, Iraqis enjoyed comprehensive health care services, including modern hospitals, throughout the country. By 1992, most hospitals were operating at a fraction of their previous level and faced severe medical and supply shortages. Health care access declined and disease proliferated. Malaria, cholera, gastrointestinal diseases, and typhoid fever became prevalent throughout Iraq.

Another effect of war in Iraq is infrastructure deterioration. The destruction of Iraq’s water supply system caused widespread failure of water purification and sewage systems.5 Public health issues became secondary to fundamental human needs; Iraq has become a developing country whose people suffer decreased access to clean water, increased prevalence of malnutrition, and heightened severity of disease outbreaks.

Research regarding practical strategies to address Iraq’s water crisis is sparse and outdated. The most recent article on the United Nations (UN) Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s Web site concerning water in Iraq was published in August 2010.6 I evaluated water quality issues in Iraq, beginning with a review of historical and current accounts of waterborne disease outbreaks resulting from war. My aim was to amass information on sustainable water quality measures to use in preventing and mitigating disease outbreaks resulting from poor water quality in Iraq. Useful knowledge includes historical and current data on waterborne diseases, best practices for rebuilding war-torn societies, nutritional status of the population, public health infrastructure and awareness, and the country’s overall economic and political state.

REVIEW

I searched multiple search engines (PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect) with the terms “water,” “Iraq,” “war,” “diseases,” “outbreaks,” and “public health” for peer-reviewed journal articles. These articles discussed wars in Iraq, historical accounts of disease outbreaks in Iraq, water in war-torn societies, desalination, and general water nutrition. I excluded studies that primarily focused on public health in the developed world, developed world interventions, and conflict-free zones.

I contacted experts in water quality and pollution, global health interventions, and nutrition to seek opinions on appropriate solutions to water quality problems in Iraq. I carefully reviewed and categorized this information.

I focused solely on disease occurrences from exposure to poor water quality in the war-torn society of Iraq and did not specifically address other environmental exposures or contamination issues, psychosocial responses, additional effects of war, health outcomes, or disease outbreaks that were not attributable to waterborne exposure. I assumed that the public health infrastructure and current economic status of Iraq were operational and stable.

Quantitative and qualitative research in conflict areas is sparse because of the difficulty of collecting data and because more urgent needs often take precedence; information from the media and nonprofit organizations often lacks a scientific basis or is unpublished. For these reasons, the search may have missed some information, limiting my ability to fully analyze this issue.

WATER, NUTRITION, AND DISEASE

Water is the most abundant compound on earth and is essential for life. It exists in liquid, solid, and gaseous states. Water is an essential nutrient for proper maintenance of homeostasis in the human body.7 Humans ingest water through drinking (water and other beverages), eating, and metabolism of food. Water has been referred to as the universal solvent because it can dissolve more substances than any other liquid.8 This solvent nature allows water to contain both harmful and beneficial substances.9

Twenty-one elements in water are known to be essential for human health. These include potentially anionic groups (chlorine, phosphorus, molybdenum, fluorine), cationic forms (calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, ferrous iron, copper, zinc, manganese), nonmetal covalent compounds formed metabolically (iodine, selenium), and ions (boron, chromium, nickel, silicon, vanadium). Fourteen elements are essential for bone and membrane structure, water and electrolyte balance, metabolic catalysis, oxygen binding, and hormone function. Adverse health effects from depletion of these elements include increased morbidity and mortality.9

Although water supplies are highly variable, drinking water supplies usually contain many of these essential minerals, either naturally or deliberately added. The enteric absorption of minerals from drinking water depends on the properties of the minerals and their reactions, the physiological conditions of the gut, the amount of consumption, and additional factors related to diet, including which minerals are ingested.9 Nonnutritional, toxic elements include lead, cadmium, mercury, arsenic, aluminum, lithium, and tin.

The Institute of Medicine recommends approximately 2.7 liters of total daily water for women and 3.7 liters for men. In the developed world, 80% of the population’s total water intake is from potable water and other beverages, and 20% is from food. Increased daily water needs may arise from increased exposure to humidity or aridity, elevated temperatures, or physical activity.10

The effect of water’s nutritional status may be relatively minor in comparison to other burdens of disease, but nutrients in water can significantly affect human health in a variety of ways. Calcium and magnesium are important for bone and cardiovascular health, fluoride prevents dental caries, sodium is needed to maintain electrolyte balance, and copper and selenium are important for antioxidant function. Copper is also a key component for iron utilization and promotes cardiovascular health. Potassium is essential in the control of heart rate, muscle contraction, energy levels, and nerve impulses. Chronic inadequate intake of dietary calcium can result in hypocalcemia, body numbness, tingling in fingers, muscle cramps, convulsions, lethargy, anorexia, abnormal heart rhythms, osteopenia, osteoporosis, increased risk of bone fracture, and rickets.11,12 Magnesium deficiency can manifest as loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, body numbness, tingling, muscle contractions and cramps, seizures, personality changes, abnormal heart rhythm, coronary spasm, hypocalcemia, or hypokalemia.13–17 Fluoride aids in the retention of calcium and strengthens teeth and bones; fluoride use in caries prevention efforts significantly reduces dental carries in the majority of populations.18,19

Because of their major contributions to human health, it is of the utmost importance that these elements be consumed in the daily diet.9 When the average intake of minerals is below recommended levels, they can be added to the water supply.

The ability of water to dissolve substances and redistribute them widely can cause adverse health effects in exposed populations. Water can carry environmental toxins such as mercury, arsenic, lead, cobalt, cadmium, petroleum products, oil, soot from oil fires, and depleted uranium.20,21 Harmful waterborne bacteria include Salmonella typhi, Salmonella paratyphi, and Vibrio cholerae; other infectious agents are the virus hepatitis A and vector diseases transmitted by Plasmodium falciparum and Schistosoma hematobin.

Malnutrition is the most common cause of immunodeficiency worldwide. It may be associated with significant impairment of bone growth, electrolyte balance, antioxidant function, iron utilization, cell-mediated immunity, phagocyte function, the complement system, and cytokine production. Deficiencies of 1 or more nutrients can alter immune responses, even if the deficiencies are relatively mild.22

Water concerns remain among the most significant international public health issues. Approximately 11% of the world’s population (780 million people) lack access to safe or affordable drinking water, and 2.5 billion people have inadequate access to sanitation services.23 In 2001, approximately 4 million people worldwide died from waterborne diseases.24 In 2002, the World Health Organization estimated that 4 million deaths annually were attributable to water-related diseases such as cholera, hepatitis, dengue fever, malaria, and other parasitic diseases.9 Inadequate fruit and vegetable intake, water sanitation, and hygiene are the main factors contributing to mortality in the developing world.25

During wartime or other conflicts, water supply systems are vulnerable to disruption. Destruction of water supply infrastructures (e.g., water mains and treatment facilities), deliberate disconnection of power stations and power lines to water stations, and disruption of the operation and maintenance of water supply systems are among the tactics combatants may use.24 Poorly managed military waste has contributed to the spread of disease and is a major contributor to the contamination of drinking water.15 When access to normal civilian water supplies is disrupted, people may be forced to collect water by unhygienic means, with resultant health consequences.24 During times of social disruption, hazardous pathogens can more easily colonize populations. Historically, devastating plague outbreaks occurred concurrently with cold, wet weather and depressed agriculture production.26

HISTORICAL WATER QUALITY AND DISEASE IN IRAQ

Iraq became a sovereign kingdom in 1932, after fighting for more than 12 years to free itself from British control.27,28 In 1958, a republic was proclaimed, although a single leader did not remain in power for long and the country was continually entangled in territorial disputes and wars.28

Transport of water in Iraq is limited, so historically, potable water was plentiful in townships and scarce in desert regions. Water was obtained from streams, springs, and wells or taken from rivers, canals, or lakes. Well water quality varied by location: wells in mountain regions were high in mineral content, and those in the lower delta were brackish. In rural Iraq, water was of poor quality, highly polluted, and untreated. In the country as a whole, only a small percentage of domestic water supplies were treated by chlorination and sedimentation. The majority of well and waterhole sources were grossly polluted and contaminated.27 By contrast, the city of Basrah took river water from Shatt al Arab, treated it by filtration and chlorination, and piped it to individual houses and community taps.

Government health services performed bacteriologic examinations throughout the country. Construction of the Hindiyah dam, beginning in the late 19th century, allowed irrigation of thousands of acres of newly productive agricultural areas. The country constructed a reservoir for the storage of flood water in 1952.

By 1954, sewage disposal facilities were still generally primitive, and cesspits were common. Modern government buildings and homes employed water carriage systems to dispose of sewage in dumping grounds on the outskirts of towns. Collection of sewage through public facilities did not exist; instead, housetops, courtyards, and other convenient sites often served as latrines. These unsanitary practices encouraged the spread of pollution in soil and water supplies.

Historically, the most commonly reported diseases endemic to the Middle East were diarrhea, hepatitis, schistosomiasis, and leishmaniasis; the majority of the reported diseases were waterborne.29 Throughout Iraq, typhoid, paratyphoid, dysentery (ameobic and bacillary), diarrhea, cholera, enteritis, trichuriasis, enterobiasis, and strongyloidiasis frequently occurred (Table 1).27,30,31

TABLE 1—

Incidence of Waterborne Diseases in Iraq, 1923–2010

| Disease | After World War I, 1923–1931, No. | After World War II, 1944–1950, No. | After Persian Gulf War I/II, 1990–1998, No. | Persian Gulf War III, 2005–2010, No. |

| Typhoid | 559–842 | 36 208 | ||

| Paratyphoid | 97–230 | |||

| Dysentery | 180–1100 | |||

| Diphtheria | 1378 | |||

| Cholera | 1500–2500 | 4697 | ||

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 17 000–30 000 | 584 204 | ||

| Schistosomiasis | 15 800–27 300 | 1500 | ||

| Malaria | 598 800 | 98 705 |

Note. Estimates, not adjusted for population, derived from reported cases.27,30,31

In the early 1950s, contaminated food and water supplies, flies, and other unsanitary conditions caused intestinal diseases in Iraq. Enteric fevers were endemic. Typhoid fever affected about 70% to 80% of the population. Outbreaks peaked in the summer months. Dysentery (amoebic and bacillary) was widespread. Amoebiasis occurred in Basrah, 60% to 70% of the population in Iraq harbored Endamoeba histolytica, and liver abscesses were common. Diarrhea and enteritis were major causes of illness and death in children. Giardiasis was common, as were salmonella food poisoning outbreaks. Cholera outbreaks followed in the wake of human travel, such as along the overland route to Mecca. In 1947, immunizations against cholera were compulsory for all travelers entering the country, as well as for the population along the Syrian frontier.27

Unprotected shallow wells or springs and poorly constructed homes lacking screens or closures for windows exposed vulnerable human populations to vector-borne diseases. Schistosomiasis was a major public health issue in 1954; concern arose that disease might spread throughout the country with expanded irrigation. Unsanitary customs, such as using canals and other convenient bodies of water for religious ablutions and bathing, allowed further spread of schistosomiasis. The disease was prevalent among children and agricultural workers. Malaria broke out sporadically throughout Iraq, with varied severity. Regional rates ranged from 26 to 266 cases per 1000 population. The inhabitants of Basrah had infectious spleen rates of approximately 75% in 1941; the rates decreased to 12% in 1949 after implementation of control programs. Ancylostomiasis was present throughout the population, although the exact distribution and severity of the infection was unknown. Infection rates were believed to be around 40% in the southern regions of the country. Ascariasis, enterobiasis, trichuriasis, and strongyloidiasis were prevalent but randomly distributed, depending on customary food consumption. In 1952, the government of Iraq, along with the World Health Organization, developed a rural health malaria control project.27

Health infrastructure significantly improved from the 1970s into the early 1980s; infant mortality rates decreased from 80 to 40 per 1000 live births, and under-5 mortality rates decreased from 120 to 60 deaths per 1000 population.9 From 1980 to 1988, Iraq was at war with the Islamic Republic of Iran. The war and political and economic sanctions resulted in the deterioration of public health and health system infrastructure and capacity and the health status of the population.

Health indicators revealed the rapid decline among Iraq’s population: in 1997, the prevalence of malnutrition was 24.7%; chronic malnutrition, 27.5%; and acute malnutrition, 8.9% among children younger than 5 years.32,33 Waterborne diseases followed degradation of water purification and sewage treatment plants; more than 1000 cholera deaths were reported in 1972, 1980, 1985, and 1989 and almost yearly from 1991 to 1999.34 The Iraqi Child and Maternal Mortality Survey found that diarrhea was the leading cause of death in infants from 1994 to 1999; it was responsible for 49.8% of infant mortlaity during this time.35 Malaria rates were significant in 1994; rates of schistosomiasis peaked in 1990.34,33

CURRENT WATER QUALITY AND DISEASE IN IRAQ

Poor water quality persists throughout Iraq. Hazardous chemicals, including carbonates, sulfates, chlorides, and nitrates, have been discovered in multiple sources. Much of the drinking water is laden with high levels of toxic minerals, suspended solids, and salinity. Many groundwater sources of drinking water are brackish or contain excess saline. In Basrah, salinity levels are higher than 7000 parts per million; the World Health Organization standard for human consumption is less than 500 parts per million. River water surrounding Basrah contains sewage, pollutants, and harmful bacteria.36

Pollution of the Tigris River is caused by industrial plants located on river banks. It is estimated that 60% of Iraq’s industrial facilities do not have functioning water treatment facilities for wastewater.37 Chlorophenols have been measured in both the river and drinking water reservoirs, demonstrating that water treatment plants are not implementing adequate sterilization or purification processes.38 Petroleum residues and hydrocarbons have been measured in the Shatt al-Arab surface area of the water column. These petroleum residue wastes originate from a variety of crude oil sources.39 Spills and leaks of petroleum products are relatively common, and such incidents may lead to high concentrations of total petroleum hydrocarbons.9 Unrefined and refined petroleum products contain various toxic substances. Aliphatic hydrocarbons containing nitrogen and sulfur, methane, heptane, or other molecules may be dissolved or suspended in the mixture. Large doses of hydrocarbons can be neurotoxic. Aromatic hydrocarbons include benzene, toluene, and benzopyrene; benzene is a known carcinogen.9 Last year, an Iraqi news article reported an oil spill outside Basra where approximately 300 tons of oil drained into 22 kilometers of the Bada’a channel in 2011.40

Wartime encourages a shift in focus from future opportunities to current unstable situations and unmet needs.41 In 2011, UNICEF reported that 20% of the general Iraqi population and 40% of rural citizens did not have access to safe drinking water; 66% of the general population had access to waste collection services, but 92% of rural populations lacked them and 17% of the Iraqi population did not have access to adequate sanitation services.42 The UNICEF report assumed that the majority of adversely affected populations were rural.

Basrah remains the most neglected area in Iraq, with significant rates of diarrhea and infectious disease. However, the health status of the population has improved considerably since 1990, when multiple invasions had disrupted health care. Public health funds were decreased by 90%; 1 in 3 clinics and 1 in 8 hospitals were looted or vandalized. Life expectancy rates fell to below 60 years for both men and women.41 The conflict of 2003 destroyed 12% of Iraq’s hospitals. Collapsed sanitation and water infrastructure led to an increased incidence of cholera, dysentery, and typhoid fever.43

Disease rates continue to increase throughout Iraq (Table 1). Typhoid fever is endemic. In 2005 to 2007, extreme weather and interrupted electricity in water supply units caused significant outbreaks of typhoid fever, with the peak incidence in 2007.31 In the same year, a cholera outbreak spread rapidly throughout 60 percent of the country.

In 2004, substantial international funding provided temporary improvement in Iraq’s public health situation; 240 hospitals and 1200 primary health centers were built and began operating. One year later, sanitary conditions in hospitals were unsatisfactory, trained personnel were absent, medical supplies were unattainable, and rural populations still lacked access. Health declined and disease rates continued to increase.43

FOUNDATIONS FOR CHANGE

War-torn societies face many large-scale economic, social, and political challenges. Deficiencies in accessible health care, public health infrastructure, and awareness contribute to the deteriorating health of the Iraqi population. Infectious diseases increase with poor sanitation, limited access to clean water, and general malnutrition.41 Long-term damage to water treatment facilities remains unrepaired.41 Electrical shortages continue to cause operational inefficiencies, while services to displaced populations are hampered by shortages of equipment and machinery.42 Technical personnel and administrative officials are needed to improve overall regulation and standards of water services, and public health awareness efforts need to reach a larger audience.42

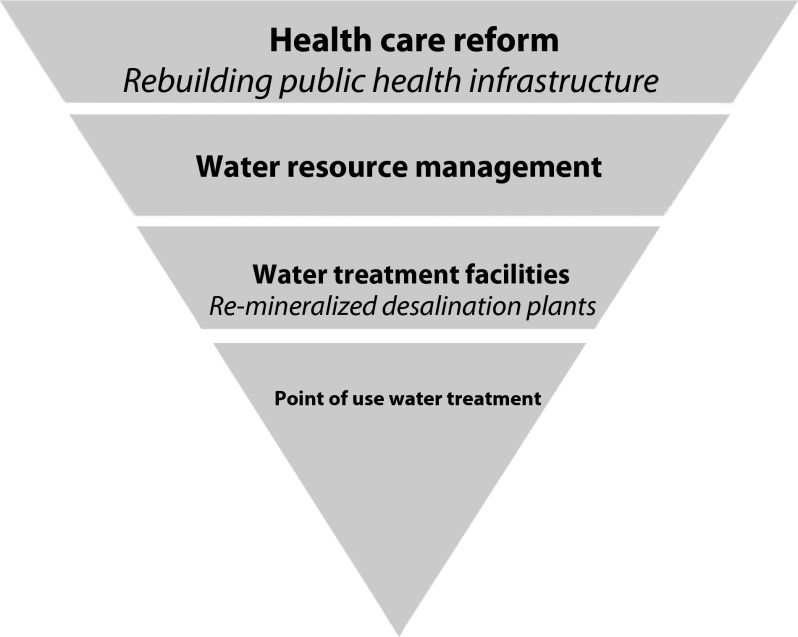

To establish a solid foundation for positive change in Iraq, primary issues of water quality, sanitation, and waste disposal need to be addressed. Standard water treatment requires clarification, filtration, purification, and desalinization, as well as routine maintenance and testing for nutritional value, with supplementation when needed.36 Achievement of a healthier environment in Iraq will require public health reform, infrastructure rebuilding, and sustainable water quality techniques (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Top-down approach to water quality reconstruction in Iraq.

Current programs are addressing water quality throughout Iraq. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization supports the Ministry of Water Resources and the government of Erbil through rebuilding infrastructure. The UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is conducting groundwater surveys that provide data on shortages and management of underwater aquifers. The World Health Organization and UNICEF are working to enhance the quantity and quality of water to underserved residential areas. The UN Settlements Program and UNICEF provide the Iraqi government with water and sanitation functional reviews, along with models for reforming public-sector water and sanitation systems.44 These working models, along with other interventions, have potential for improving Iraq’s water quality and ameliorating its waterborne disease burden.

Health Care Reform and Public Health Interventions

Public health must address not only current issues, but historical and anticipated challenges as well. The recent Brazilian health reform movement proved that rapid progress can be achieved in public health.45 If Iraq adopted the Brazilian health reform model, its health care delivery could significantly improve.

In Brazil, decentralization allowed municipalities to assume greater responsibility for health services management; this system enhanced and formalized social participation in health policymaking and accountability. Health care reform in Brazil led to increased access to health care, universal coverage for vaccinations and prenatal care, enhanced public awareness of health as a right, and expansion of human resources and technology.46 Expansion of health care coverage and universal vaccination and prenatal care, including nutritional supplementation, reduce malnutrition rates and may decrease susceptibility to infectious diseases.

Rebuilding public health infrastructure requires attention to social determinants of historical health deficits, availability of resources and funding, current needs, prevention of disease spread, and mortality rates, among many other factors. Strategies must be flexible, efficient, and innovative to address issues as they arise.47 Private-sector enterprises are often more efficient and innovative than governments and can provide financial aid and encourage environmental and social sustainability.48 Investing in human and social capital may spur sustainable economic growth; income transfers strengthen the coverage and effectiveness of nutrition programs.45 Public–private partnerships are essential to sustaining financial aid to impoverished regions (e.g., employment through public institutions), rebuilding government capacity and medical infrastructure, and supporting the Ministry of Health. Military and humanitarian aid must be coordinated, while quantitative aid impact indicators can be used to measure the quality and effectiveness of programs.48 Examples of important interventions are monitoring water quality, ensuring daily access to clean water, and providing education about waterborne diseases, environmental contaminants and exposures, and boiling water when needed. Media can disseminate water health messages to address acute problems.

Water Quality Development and Monitoring Systems

Basic drinking water treatment comprises filtering particulates and adding chemicals to treat pathogens; multiple processes clarify or remove large particles, aerate to promote oxidation, remove smaller particles through coagulation and sand filtration, and finally treat the water chemically. These processes ultimately provide pathogen-free water, prevent recontamination of the distribution system, and minimize harmful byproducts. Some existing water treatment facilities throughout Iraq have been repaired by nonprofits, including Veterans for Peace and the US Army.49,50 Conclusive evidence about the actual functioning of these water treatment plants remains unavailable.

Another important aspect of waterborne illness prevention is home-based water treatment.51,52 A simple model developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Pan American Health Organization comprises point-of-use water treatment, safe storage of treated water, and community education. The model elements may be adapted to the needs of affected populations.51

Point-of-use water treatment focuses on simple household methods for cleaning water, such as boiling, bleaching, filtering through a cloth, sediment (sand and gravel) filtration, and ultraviolet light disinfection; however, boiling water can be economically and environmentally unsustainable in the developing world, and boiled water can easily be recontaminated during transfer to a container and storage. Chemical disinfectants are expensive and most likely unsuitable for household use. Solar disinfection involves a combination of ultraviolet radiation and thermal treatment, but the water may be recontaminated during transfer. The annual total daily diffuse radiation (70.82 mg/m2) and value of clearness index (KT) percentage of Baghdad (range = 65.9% in August to 48.4% in January) indicates the potential efficacy of solar disinfectant point-of-use water treatment in Iraq.53 Safe water vessels can be used in every process; these vessels store clean water and control recontamination.54 Storage tank openings should be less than 10 centimeters in diameter; this design limits human exposure to the vessel’s contents.54

Integrated water resource management addresses water quality concerns over the long term. Either governmental or nonprofit entities can monitor water quality. An interagency UN program encourages water-related programs and projects through development assessment, management, monitoring, and use of water sources by maximizing systemwide action through support and established targets and goals.55 Program administrators track implementation, develop necessary changes, and support water-related initiatives.55 Data on adaptations of established programs and program impact can inform organizations’ choices about change. Success in water resource management is facilitated by communication between program administrators and beneficiaries; such a working relationship allows parties to learn from one another and to respond effectively to changing conditions.56–58

Nutritional Supplements in Water

In 1989, a nutritional survey conducted in Iraq determined that the distribution of the weight and height of children aged 8 years and younger was similar to that in the international reference population; Iraq had one of the highest levels of food availability per capita in the region.59 Sanctions following the Gulf wars caused decreased food imports and a depressed economy. To this day, a large portion of the Iraqi population relies heavily on subsidized food prices; some foods are rationed, but open markets are unregulated.60,61 Approximately 1 million people in Iraq were classified as food insecure in 2008.62 Current basic rations are largely composed of carbohydrates and are deficient in protein and most vitamins and minerals.61

Food is the principal source of nutrition, but water can also provide beneficial dietary substances. Determining the true effects of water nutrition requires collection of data on composition and intake, nutritional factors under steady-state conditions, and water ingestion rates, all of which may enhance or decrease the importance of minerals in drinking water.9 Relevant health outcomes should be evaluated and compared with the nutritional statuses of vulnerable populations. In developing countries, where the average intake of minerals is below recommended levels, nutritional supplements in water may help close that gap. Young children, pregnant women, older populations, immunocompromised, and malnourished people are more sensitive than the typical healthy adult to inadequate levels of essential dietary nutrients.

Desalination plants run the risk of contributing to malnutrition and increasing susceptibility to infections.9 Desalination removes salt and other minerals from salt water so that it can be used for drinking or irrigation.63 The desalination process reduces virtually all ions in drinking water; populations relying on this water source receive fewer nutrients, which may have a significant impact on health if regular diets do not provide sufficient nutrient supplementation.9 If not properly stabilized, demineralized water can also corrode plumbing, thereby increasing the population’s exposure to metals, including copper and lead.

However, desalination plants can deliver clean water to populations that have low-quality water or limited access to drinking water; the plants can also offer nutrient-rich water. Remineralized water adds beneficial nutrients to drinking water, of particular importance to malnourished populations. Minimum amounts of calcium, magnesium, fluoride, and other essential trace minerals must be specified and heavily regulated within the plants. When desalination plants are contemplated as part of new or reconstructed water treatment facilities, remineralization should also be implemented.

According to an online Iraqi news source, 8 desalination plants opened in Basrah in 2010.64 Monitoring of the effects should report indicators of population well-being and disease rates. Data collection should include changes in population musculoskeletal and cardiovascular health and disease diagnoses and prevalence of dental caries to provide a complete assessment of the effects of nutrients in the water.

CONCLUSIONS

Because of its extraordinary ability to dissolve and transfer innumerable particle types, water plays a large role in providing nutrients or contributing to toxicity and adverse health effects. The quality, nutrient content, and availability of water differ throughout the world; variation depends on many things, including climate, location, and the economic status of the country. Water characteristics can dramatically shift in unstructured situations such as war.

Located in the dry climate of the Middle East, Iraq continually suffers from water scarcity, and a multitude of factors contribute to water pollution. In the past century, the population of Iraq has experienced countless wars, directly and indirectly exacerbating long-standing waterborne disease issues. Throughout the country, outbreaks of cholera, typhoid fever, malaria, and many other diseases followed every war. Alarming numbers of waterborne disease outbreaks continue to be recorded throughout Iraq. Combined governmental reform and public health efforts are urgently needed to implement and maintain long-lasting change.

Significant, long-lasting reduction in waterborne disease will require public health and health care reform; improvements in access to potable water, such as remineralizing desalinated water; monitoring and evaluation systems; and educational interventions. Long-term commitment to change in Iraq could provide individual access to clean water, alleviate interrelated cycles of health disparities, and promote health and well-being throughout the country.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Qatar Foundation for sponsoring the Middle East Environmental Urbanization Project.

Special thanks to the editors and the anonymous reviewer for their comments and critical insight.

Note. The views expressed within the article are my responsibility alone.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was required because no human participants were involved.

References

- 1.Metz HC. Iraq: A Country Study. Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of State. Iraq. Available at: http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/6804.htm. Accessed February 20, 2012.

- 3.Litz B. The Unique Circumstances and Mental Health Impact of the Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Washington, DC: National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Department of Veterans Affairs; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L, Evans T, Apand Set al. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1984–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acheson ED. Health problems in Iraq. BMJ. 1992;304(6825):455–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, Office for Iraq. Iraq’s water in the international press. 2011. Available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/iraq-office/natural-sciences/water-sciences/water-in-iraq. Accessed April 1, 2012.

- 7.Kleiner SM. Water: an essential but overlooked nutrient. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(2):200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States Geological Survey. Water properties: facts and figures about water. 2012. Available at: http://ga.water.usgs.gov/edu/waterproperties.html. Accessed February 4, 2012.

- 9.Nutrients in Drinking Water. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005.

- 10.Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes: water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. 2004. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2004/Dietary-Reference-Intakes-Water-Potassium-Sodium-Chloride-and-Sulfate.aspx. Accessed March 20, 2012.

- 11.Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed]

- 12.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Palermo NJ, Castaneda-Sceppa C, Rasmussen HM, Dallal GE. Treatment with potassium bicarbonate lowers calcium excretion and bone resorption in older men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(1):96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rude RK. Magnesium deficiency: a cause of heterogeneous disease in humans. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(4):749–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saris NE, Mervaala E, Karppanen H, Khawaja JA, Lewenstam A. Magnesium An update on physiological, clinical, and analytical aspects. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;294(1–2):1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Board on the Health of Select Populations, Institute of Medicine. Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

- 16.Shils ME. Magnesium in Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 9th ed. New York, NY: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elisaf M, Milionis H, Siamopoulos KC. Hypomagnesemic hypokalemia and hypocalcemia: clinical and laboratory characteristics. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1997;23(2):105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Encyclopedia Britannica. Fluoride deficiency. 2012. Available at: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/211435/fluoride-deficiency. Accessed April 1, 2012.

- 19.ten Cate JM. Fluorides in caries prevention and control: empiricism or science. Caries Res. 2004;38(3):254–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Depleted uranium—fact sheet. 2003. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs257/en/print.html. Accessed April 1, 2012.

- 21.World Health Organization. Petroleum products in drinking water. 2003. Available at: http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/dwq/chemicals/Petroleum%20Productsrev071105.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2012.

- 22.Chandra RK. Nutrition and the immune system: an introduction. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):460S–463S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation. Progress on Drinking Water and Sanitation: 2012 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suleymanova M. Access to water in developing countries. Available at: http://www.parliament.uk/documents/post/pn178.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Report 2002. Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002.

- 26.Weiss RA, McMichael AJ. Social and environmental risk factors in the emergence of infectious disease. Nat Med. 2004;10(12 suppl):S70–S76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simmons JS, Whayne TF, Anderson GW, Horack HM. Iraq. In: Global Epidemiology: A Geography of Disease and Sanitation. Vol 3. The Near and Middle East Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Company; 1954:21–49. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Central Intelligence Agency. Fact sheet: Iraq. 2012. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/iz.html. Accessed April 9, 2012.

- 29.Oldfield EC, 3rd, Wallace MR, Hyams KC, Yousif AA, Lewis DE, Bourgeois AL. Endemic infectious diseases of the Middle East. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(suppl 3):S199–S217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shamo FJ. Malaria in Iraq. 1999. Available at: http://www.emro.who.int/rbm/malariasituation1999.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Iraq integrated control of communicable diseases. 2007. Available at: http://www.emro.who.int/iraq/pdf/CommunicableDiseases_06_07.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. Health system profile: Iraq. 2006. Available at: http://gis.emro.who.int/HealthSystemObservatory/PDF/Iraq/Full%20Profile.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Potential impact of conflict on health in Iraq. 2003. Available at: http://www.who.int/features/2003/iraq/briefings/iraq_briefing_note/en/index3.html. Accessed September 18, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Cholera country profile: Iraq. 2010. Available at: http://www.who.int/cholera/countries/IraqCountryProfile2010.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Awqati NA, Ali MM, Al-Ward NJet al. Causes and differentials of childhood mortality in Iraq. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Agency for International Development. The bottled water market in Iraq. 2007. Available at: http://www.iajd.org/files/3_1.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. Stories that count: regional office for eastern Mediterranean Iraq representative office. 2009. Available at: http://www.emro.who.int/iraq/pdf/progress_report_2009.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Janabi KWS, Alazawi FN, Mohammed MI, Kadhum AAH, Mohamad AB. Chlorophenols in Tigris River and drinking water of Baghdad, Iraq. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2011;87(2):106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Douabul AAZ, Al-Saad HT. Seasonal variations of oil residues in water of Shatt al-Arab river,Iraq. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1985;24(3):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lando B. Iraq oil report. 2011. Available at: http://www.iraqoilreport.com/oil/production-exports/oil-pipeline-leak-threatening-basra-water-supply-6465. Accessed March 20, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dyer O. Infectious diseases increase in Iraq as public health service deteriorates. BMJ. 2004;329(7472):940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.UNICEF. Environmental survey in Iraq (water sanitation and municipal services). 2011. Available at: http://www.iauiraq.org/documents/1555/Environmental%20Survey%20%20ENGLISH.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Country profile: Iraq. 2006. Available at: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/profiles/Iraq.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inter-Agency Information and Analysis Unit. Water in Iraq fact sheet. 2011. Available at: http://www.iauiraq.org/documents/1319/Water%20Fact%20Sheet%20March%202011.pdf Accessed April 9, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uauy R. The impact of the Brazil experience in Latin America. Lancet. 2011;377(9782):1984–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, Bahia L, Macinko J. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet. 2011;377(11):1778–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Utzinger J, Wyss K, Moto DD, Tanner M, Singer BH. Community health outreach program of the Chad-Cameroon petroleum development and pipeline project. Clin Occup Environ Med. 2004;4(1):9–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morton MJ, Burnham GM. Dilemmas and controversies within civilian and military organization in the execution of humanitarian aid in Iraq: a review. Am J Disaster Med. 2010;5(6):385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.US Army. Iraq, U.S. partner to refurbish water treatment plants. 2009. Available at: http://www.army.mil/article/27055. Accessed April 9, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veterans for Peace. Iraq water project. 2011. Available at: http://www.veteransforpeace.org/our-work/healing-the-wounds-of-war/iraq-water-project. Accessed April 9, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mintz ED, Reiff FR, Tauxe FV. Safe water treatment and storage in the home. A practical new strategy to prevent waterborne diseases. JAMA. 1995;273(12):948–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swerdlow DL, Malanga G, Begokyian G. Epidemic of antimicrobial resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 infections in a refugee camp, Malawi. In: Program and Abstracts of the 31st Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. Abstract 529. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Riahi M, Al-Kayssi A. Some comments on time variation in solar radiation over Baghdad, Iraq. Renewable Energy. 1998;14(1–4):479–484. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koehler JE, Ries A, Tauxe R. Cholera risk assessment in Texas ‘Colonias,’ El Paso County, 1991 [abstract]. In: Program and Abstracts of the 42nd Annual Epidemic Intelligence Service Conference; April 19–23, 1993; Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 55.United Nations Water. Status report on integrated water resources management and water efficiency plans. 2008. Available at: http://www.unwater.org/downloads/UNW_Status_Report_IWRM.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.McLaughlin M. Implementation as mutual adaptation: change in classroom organization. : Williams W, Elomore R, eds. Social Program Evaluation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Welsh WN, Harris PW. Criminal Justice Policy and Planning. Cincinnati, OH: Anderson; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nimmer RT. The Nature of System Change: Reform Impact in the Criminal Courts. Chicago, IL: American Bar Foundation; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 59.National Child Health Survey. Baghdad, Iraq: Ministry of Health; 1990.

- 60.Drèze J, Gazdar H. Hunger and Poverty in Iraq. World Dev. 1992;20(7):921–945. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Center for Economic and Social Rights. The human costs of war in Iraq. 2003. Available at: http://www.cesr.org/downloads/Human%20Costs%20of%20War%20in%20Iraq.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 62.United Nations World Food Programme. Comprehensive food security and vulnerability analysis in Iraq. 2008. Available at: http://www.krso.net/files/articles/220611063309.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Collins English Dictionary. Desalination. 2012. Available at: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/desalination. Accessed February 20, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 64.MENAFN. Aswat al-Iraq [Voices of Iraq]. Iraq—PM opens 8 water desalination stations in Basra. 2010. Available at: http://www.menafn.com/menafn/qn_news_story_s.aspx?storyid=1093306905. Accessed April 10, 2012. [Google Scholar]