Abstract

Hispanics are the fastest growing racial/ethnic group in the United States, and smoking is the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality among this population. We analyzed tobacco industry documents on R. J. Reynolds’ marketing strategies toward the Hispanic population using tobacco industry document archives from the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu) between February–July 2011 and April–August 2012. Our analysis revealed that by 1980 the company had developed a sophisticated surveillance system to track the market behavior of Hispanic smokers and understand their psychographics, cultural values, and attitudes. This information was translated into targeted marketing campaigns for the Winston and Camel brands. Marketing targeted toward Hispanics appealed to values and sponsored activities that could be perceived as legitimating. Greater understanding of tobacco industry marketing strategies has substantial relevance for addressing tobacco-related health disparities.

Hispanics make up the largest, youngest, and fastest-growing racial/ethnic group in the United States, accounting for 16.3% (50.5 million) of the total population.1 Data from national surveys have suggested that 12.5% of Hispanic adults in the United States are current smokers (15.8% of men and 9% of women), which is lower than the 20% to 21% seen for Black and White non-Hispanics.2 Hispanics are also more likely to be light or intermittent smokers than Whites.3–5 Despite Hispanics’ lower smoking prevalence rates than those of the general population, smoking among Hispanic men and certain Hispanic subgroups approximates or exceeds the national average.6–11 Additionally, Hispanics are less likely to be advised to quit than their White counterparts, and they experience low rates of successful cessation.12–14 Smoking prevalence among Hispanic youths (grades 9–12) is similar to that of White youths and substantially higher than that of African American youths.15 Low socioeconomic status (SES) and poor educational attainment, which are common characteristics of Hispanic youths, are powerful determinants of smoking behavior, including early onset of tobacco use and established smoking patterns in adulthood.5,16–18

Beginning in the 1970s, the major tobacco companies developed increasingly sophisticated segmented marketing plans, targeting advertising to specific demographic or psychographic groups and increasing marketing toward young adult smokers (aged 18–25 years).19 The purpose of segmentation is to identify groups of consumers who share common characteristics and behaviors and who will respond similarly to a marketing approach.20 Studies have found that specific racial and ethnic groups may be exposed to tobacco advertising in different volumes and with distinct content.21–24 Marketing research has also suggested that targeted marketing may be especially effective in generating a positive response from members of minority groups because they may perceive the targeted appeals as group legitimating.25–27 The contribution of targeted marketing to tobacco-related health disparities among various population subgroups has received substantial research attention.28–33 In particular, the marketing of menthol cigarettes to African Americans provides a potent example of an ongoing, long-term targeted marketing effort.34

Evidence has suggested, however, that Hispanics may be more susceptible to tobacco marketing than other ethnic minorities.35,36 Research literature has indicated that the Hispanic population makes for a viable and attractive consumer market for a variety of industries because its demographic and economic profile satisfies the 4 preconditions for market segmentation: the Hispanic population is (1) measurable (of quantifiable size and purchasing power), (2) substantial (large and profitable), (3) accessible (geographically concentrated), and (4) actionable (effective marketing strategies can be designed to attract and serve this population segment).25,37–39 Marketing research efforts have highlighted brand loyalty, retail shopping behaviors, strength of ethnic identification, acculturation levels, cultural values, media, and language preference in advertisement of products to successfully reach this population.37–39

Although previous studies have analyzed internal tobacco industry documents to understand the industry’s targeted marketing efforts, no study has provided a detailed review of these documents in terms of marketing to Hispanics. We used internal tobacco industry documents to conduct a case study of R. J. Reynolds’ (RJR’s) marketing of cigarettes to Hispanics. However, although RJR pursued visible campaigns aimed at the Hispanic market, it was not the only company to do so.19,40–45 We analyzed tobacco industry documents to address 2 questions: (1) what marketing strategies and tactics did RJR use to promote tobacco products among Hispanics, and (2) how did RJR use its research knowledge of Hispanic culture to penetrate and disseminate their products in the Hispanic community? For the purpose of consistency with the tobacco documents, we use the term “Hispanic” rather than “Latino” because the former was the term used by RJR.

METHODS

We searched the tobacco industry document archives from the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu) between February–July 2011 and April–August 2012.

We used search methods and approaches similar to those in other tobacco industry documents studies, starting with broad search terms and then using a snowball strategy to expand from key documents.46–51 Initial search terms included “Hispanic,” “Latino,” “Spanish,” “bilingual,” “marketing,” “advertising,” and “campaigns.” Early searches imposed no date restrictions and were limited to the RJR document collection. On the basis of these initial searches, we developed more specific search strategies around Hispanic market segmentation, psychographics (e.g., lifestyle and personality characteristics), and specific targeted marketing campaigns (Winston and Camel). We reviewed search results sorted by document date to understand the broad timeline of events. We excluded duplicates, documents that were undated, and those in which the context was not identifiable. In addition, we conducted further snowball searches for contextual information on relevant documents using names, project titles, brand names, document locations, dates, and reference (Bates) numbers that were identified in earlier searches.

Both authors reviewed the search results and documents retrieved to determine their relevance to the research questions. We analyzed a final collection of 119 research reports, presentations, memoranda, advertisements, and plans that were deemed relevant. We reviewed the documents, organized them chronologically, and abstracted key information. We identified common themes and resolved additional questions that arose by gathering additional data. Information from documents was triangulated with published literature and independent publications on marketing strategies, targeted marketing, smoking behaviors, and health disparities. We conducted these searches using the Web of Science, Scopus, JSTOR, and PubMed databases. We also searched the Web sites of Reynolds American, Inc., RJR’s parent company, and current Hispanic organizations that tobacco industry documents indicated have had relationships with RJR in the past. In addition, we obtained information on marketing activities and sponsorship in Spanish and English from general search engines (e.g., Google).

RESULTS

RJR conducted its first study on ethnic markets (African Americans, Jews, and Hispanics) in 1969. This study cited marketing successes by other companies (Coca-Cola, Pepsi-Cola, Schaefer Beer) targeting the Hispanic community but concluded that the Spanish-speaking population was not effectively covered by the general English-speaking media. The report went on to state,

Spanish-speaking consumers [are] extremely loyal to brands advertised to them but to win them takes more than simple translations of product labels from English to Spanish. It requires regular advertising in order to build up confidence in the product but once that confidence is gained, they can be expected to be loyal forever.43

Beginning in the mid-1970s52,53 and into the 1980s, RJR and other tobacco companies, such as Philip Morris, Lorillard, and Brown & Williamson, became increasingly interested in developing marketing strategies to target the Hispanic population.54–62 By 1980, tobacco companies had begun using US Census Bureau data and information from the Immigration and Naturalization Service to track population demographic changes and trends in documented and undocumented immigration from Spanish-speaking countries.54,63 At the time, projections indicated that the United States was becoming the fifth largest Spanish-speaking nation in the world, with a Hispanic population that had considerable consumer spending power.64 Data also indicated that Hispanics were concentrated in defined geographical regions of the country and had a narrow scope of media consumption (e.g., Spanish-language newspapers and magazines), which provided opportunities for targeted marketing.65

For RJR, Hispanics represented an important market to develop because they were a young, growing population; geographically clustered; and responsive to RJR’s marketing.66 Various internal reports from the company noted that Hispanics were key to the growth of the company because the Hispanic market was “brand loyal,” “lucrative,” “easy to reach,” and “undermarketed.”67 To augment its understanding of the Hispanic market, RJR had by now developed a system to track the market behavior of Hispanic smokers along with targeted strategies, which we describe in the following section.53,68–70

Tracking the Hispanic Market

In September 1981, RJR began contracting with Burke Marketing Research, a marketing firm specializing in Hispanic consumer research.71,72 Initially, RJR added smoking-related questions to Burke’s ongoing multi-industry marketing survey of 4 major metropolitan areas with high concentrations of Hispanics (Los Angeles, CA; San Antonio, TX; New York, NY; and Miami, FL).73–75 RJR included questions on cigarette use, demographics, preferred brand, and subtype (e.g., “light”).75 The results of the Spanish-Speaking Omnibus Study reported in 1982 showed a lower incidence of smoking in the Hispanic market (20%) than in the general market (33%), suggesting room for growth.73 However, this study did not provide data on Hispanic smokers’ awareness, attitudes, or perceptions of specific major cigarette brands, and RJR worked with Burke to develop a more sophisticated tracking system aimed solely at the Hispanic cigarette market.73,76 The Hispanic Tracking System began with an initial wave of 1000 Spanish-speaking female heads of household in 1981 and grew to include 4200 women and men.75 This system collected information on smoking incidence among specific Hispanic subgroups (Cubans in Miami, Puerto Ricans in New York, Mexican Americans in Texas, Mexican Americans in California) and included information on use, awareness, and purchasing patterns by brand and type. The system also collected information on awareness of product marketing and advertising, attendance at promotional events, and attitudes related to key brands, such as Winston and Marlboro and later Camel, Salem, Kool, and Newport.73,75,77 The system generated a series of annual marketing research reports that were used to inform the company’s Hispanic Market Annual Plans each year.78–80 The estimated annual cost of the Hispanic Tracking System was between $150 000 and $286 000 per year.81 The company also created a Hispanic Task Force in 1987.82,83 One of the main recommendations of the task force was to significantly increase spending for the Hispanic market, from $7.7 to $36.7 million.82 RJR’s Hispanic Tracking System was used throughout the 1980s, but it was eventually superseded in 1990 by a larger national tracking system that incorporated information about different ethnic groups within a brand-focused framework.84

An analysis of selected data from the Hispanic Tracking System prepared by Market Development, Inc., suggested important differences in media usage and purchasing behavior by region.85 For instance, Hispanics from Miami, most of them foreign-born and better educated, were more likely to report feeling comfortable reading Spanish-language publications than Hispanics in San Antonio. At the same time, a close-knit Hispanic community in San Antonio contributed to greater participation in local festivals there, providing an alternative marketing venue. In the Miami and San Antonio Hispanic markets, sales were primarily made in supermarkets, whereas small grocery stores were the leading purchase outlets in New York and Houston, Texas. In Los Angeles, cigarette purchase was more common in liquor stores. Young smokers were more likely than older smokers to purchase cigarettes in stores where Spanish was spoken because they tended to shop in small outlets that were more likely to be owned or staffed by Hispanics. Thus, the data allowed RJR to track purchasing patterns by brand in specific subgroups of the Hispanic population.

R. J. Reynolds’ Strategies to Reach the Hispanic Population

Hispanic ethnic and cultural identification.

In the early 1980s, RJR defined 5 key market segments on the basis of their own Market Segmentation Study (virile, coolness, stylish, moderation, and savings).80,81,84,86,87 The “virile” segment was characterized by a masculine and rugged image, and “coolness” was associated with smooth flavor and menthol products. The virile segment, generally younger and less educated, accounted for more than half of all male smokers. RJR’s marketing research concluded that Marlboro was the leading brand in this segment and its share was growing substantially because of its success in attracting young adult smokers (YAS). Thus, during the 1980s, RJR sought to compete against Marlboro in reaching the younger virile segment.88

A 1982 analysis of RJR’s Market Segmentation Study found that among Hispanics, RJR had a substantial presence in the coolness and virile segments with the Salem and Winston brands, respectively. However, this analysis noted that Marlboro still dominated the Hispanic virile segment, taking 60% of the segment market share compared with Winston’s 36%.89 In addition to market segmentation, the company worked with Mercadotécnica Consulting to characterize the Hispanic market through a set of “common attitudes, [shared] beliefs and values” related to issues of “family, male/female role, masculinity, Hispanic pride, [and] Catholic religion.”64,90

Internal company marketing research reports described strong family bonds and ethnic identification, brand loyalty, and preference for brand goods as central characteristics of Hispanic smokers (see the top box on the next page).91,92 These reports described the Hispanic smoker’s personality as sociable, emotional, pleasure seeking, polite, respectful, and macho (see the bottom box on the next page).93 Thus, although Hispanics were viewed as emotional, they were also portrayed as polite and respectful, suggesting that negative advertising would not appeal to them. Hispanics were also described as more open to positive advertising messages in general, viewing them as a form of education about the product and its use in realistic situations.93,94 RJR also found that Hispanics’ brand choices were influenced by their SES, various psychosocial factors (e.g., discrimination, need for social and personal acceptance), language use, and preference for retail shopping.95,96 Hispanic smokers also exhibited greater brand loyalty, according to industry surveys.90,97

RJR predicted that as Hispanics became more assimilated into mainstream US culture, they would continue to identify with a “dual concept of being an American with Spanish cultural origins and language.”97 The company’s reports containing Hispanic marketing and sales recommendations noted that Hispanics “report being discriminated [against], not feeling wanted and appreciated,” which in turn created “a strong need for recognition.”94,95 Advertisements and promotions that used the Spanish language and referenced Hispanic cultural values would provide that sense of recognition.95 One of these reports with a broader focus on improving RJR’s Hispanic marketing performance described Hispanics as aspiring to fit in and succeed in the United States. “The importance of being an American and succeeding in America cannot be underestimated,” they noted.97 As a result, the company determined that Hispanic smokers would be more likely to prefer established brand names and upscale marketing.97

R. J. Reynolds’ considerations of Hispanic heterogeneity.

During the 1980s, the company became more cognizant of the differences among Hispanics and of a need to consider multiple contextual factors in marketing to Hispanic subgroups, including local, geographic, and cultural factors and level of assimilation or acculturation.93 For instance, RJR noted

the newly arrived are less competent in the English language, less knowledgeable about American brands, and less sophisticated in their reactions to advertising on behalf of those brands.98

Additionally, the process of translating ads into Spanish presented challenges because of differing accents, idiomatic expressions, words, and levels of bilingualism and biculturalism.99 Therefore, the company considered regional Spanish-language and cultural differences when developing language for marketing strategies.97,98

RJR documents also described varying degrees of assimilation or acculturation to US values and behaviors among Hispanic subgroups. For example, a 1984 internal report noted that smoking incidence among Hispanic women was substantially lower than that of women in the general population.100 As Hispanic women became more assimilated, smoking incidence increased, suggesting that the lower prevalence among Hispanic women was “highly related to Hispanic culture.”101 RJR conducted a Hispanic assimilation analysis in 1990 using an assimilation index consisting of “assimilated,” “nonassimilated,” and “fully assimilated.” For nonmenthol brands, ad and promotional awareness increased across brands as assimilation increased. Winston and Camel were found to be less appealing to “more Spanish” Hispanics.102 Similarly, for menthol brands Salem and Newport, awareness, trial, purchase, and promotion increased as assimilation increased. The company apparently considered assimilation and acculturation to be a key part of its marketing strategies to “reverse the trend and level of smoking among younger adult Hispanics.”101

A qualitative study commissioned by RJR to gain insight into the Hispanic smoker’s personality and improve marketing strategies pointed to the importance of generational differences. Although older Hispanics were seen as clinging to old ways, younger adult Hispanics appeared open to US influences, as well as “less conservative, less traditional, more liberated in their values and attitudes, better educated, and more competent in English.”94 Thus, different marketing approaches would be required to reach both older and younger smokers.

In the next sections, we describe how RJR translated its market research into the Hispanic Winston and Camel campaigns.

Hispanic Winston campaigns.

In 1988, RJR developed a new Winston advertising campaign for the general market in response to indications that the brand was seen as “conservative and old-fashioned,” whereas Marlboro was more popular among YAS. Called the “Real People” campaign, its aim was to

rejuvenate the brand’s image and radically change the way smokers think about Winston. It must [make] Winston a relevant brand for young adult smokers who reflexively adopt Marlboro through peer-pressure.103

The company sought to position Winston as a smooth, full-flavored cigarette for smokers who desire to “make conscious, independent, mature adult product and lifestyle choices.”104 The Real People campaign illustrated Winston’s repositioning strategy based on a “platform of mature and independent choice” targeted at working-class smokers “who [are] loyal to their beliefs, families and friends and express admirable, simple, honest, enduring values and emotions.”105,106

Because of the importance of Hispanics to the young adult market, RJR developed a version of the Winston Real People campaign specifically targeted toward this group. The Hispanic Real People campaign targeted 21- to 34-year-old consumers and was intended to “[differentiate] Winston from Marlboro—its competitor—and other Virile brands, and to leverage Winston as an authentic brand.”107

The Winston Hispanic campaign was based on previous findings indicating that high levels of agreement on positive attributes or imagery (such as Hispanic cultural values) tended to increase sales. Thus, the Hispanic campaigns were oriented around 2 main psychographic concepts: (1) young, mature-minded, and independent individuals who retained traditional values but at the same time had the “desire to assimilate mainstream values” and (2) a “genuine and unpretentious personality that admires self-made success and overcoming obstacles.”108

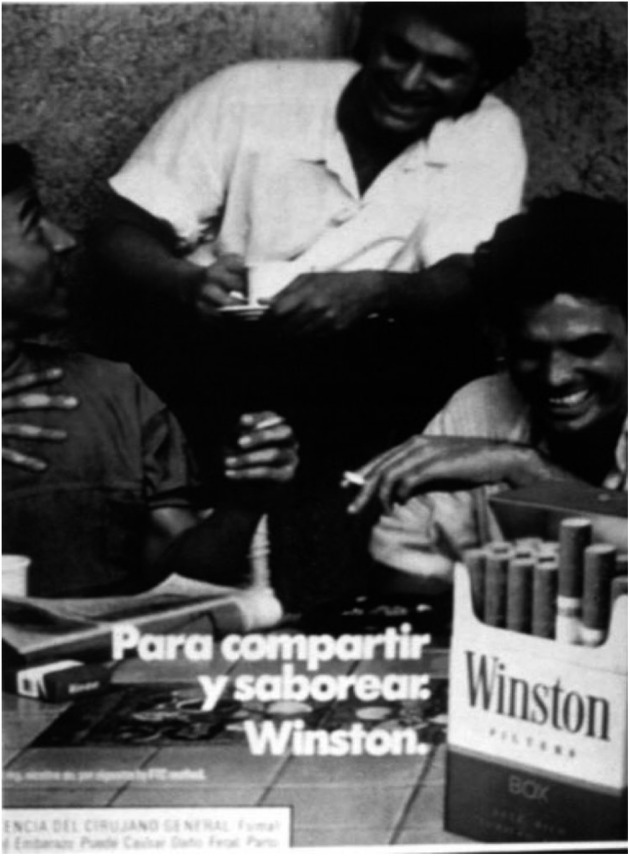

Real People was executed in the Hispanic market as Nuestra Gente (which translates literally as Our People). For the Hispanic campaign, RJR prepared a range of print ads expressing a variety of Hispanic values, such as pride, loyalty, courage, challenge, family, friends, honesty, satisfaction and reward, accomplishment, and aspirations.109 RJR also developed print ad images that incorporated the important Hispanic cultural value of respect into the tone of the campaign, combined with “soft” (e.g., visuals of a barbecue with family and friends), “masculine” (e.g., a shipyard or a climber), and “energetic” (e.g., an airport reunion or rapids) situations.109 RJR noted “smokers preferred this approach [Real People visuals] because it represented the Hispanic community as a whole.”110 Focus groups of the Winston Real People campaign held in Los Angeles and San Antonio indicated that Hispanic smokers identified with situations depicted in the campaign, such as those involving family and friends, or situations that evoked success, respect, pride, or overcoming obstacles.111 Some of the copy lines of the Hispanic Winston advertisements conveyed messages of social attributes, behaviors, and values cherished by Hispanics: “lo tiene todo,” “para compartir y saborear,” and “lo mejor,” translated by RJR into English as “it has it all,” “for sharing and savoring,” and “the best.”112 One campaign ad, shown in Figure 1, depicted a group of Hispanic men having a good time playing cards, which emphasized enjoyment and camaraderie, both concepts that RJR found to be valued by Hispanics,113,114 as well as the sharing and the social aspect of “smoking enjoyment. Figure 1.”111

FIGURE 1—

R. J. Reynolds’ Hispanic Winston campaign “Para Compartir y Saborear” (“For Sharing and Savoring”): 1988.

Source. RJ Reynolds documents.201

In 1987, RJR conducted a series of focus groups to refine the Nuestra Gente campaign.115–117 Hispanic smokers generally responded positively to the ads, with comments such as “Yeah, I can see myself sharing a cigarette with a co-worker” or, for a job promotion scene, “That guy is moving up—he’s a supervisor now. I want to someday be a supervisor.”110 The company also used eye-movement tracking and other techniques to assess the strengths and weaknesses of specific elements of the materials.118 Ultimately, Winston’s presence within both the Hispanic and the general market continued to decline despite the Real People campaign. Nevertheless, the company continued to promote Winston in the Hispanic market, suggesting that ongoing community relationships would continue to benefit the company.100,118–120

Hispanic Camel campaign.

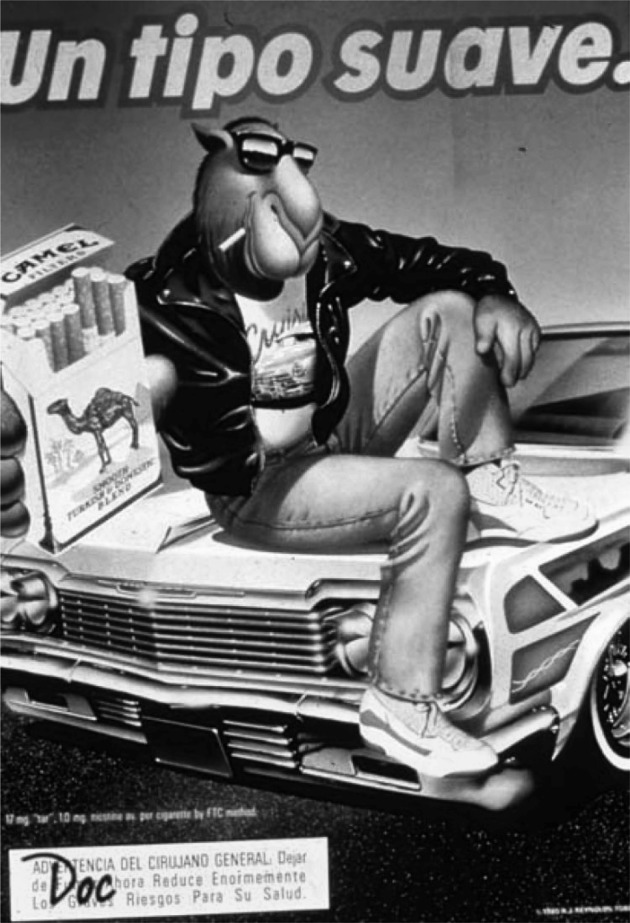

In 1984, RJR began focusing Camel brand marketing around the YAS general market because “YAS [were] the only source of replacement smokers.”83 Data from the 1982–1984 Hispanic Tracking System survey indicated that Camel had a significant base in the virile smoker segment across particular Hispanic subgroups (Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans).121 In 1989, the company developed the Camel Hispanic program and a version of the Camel “Smooth Moves” (“Un Tipo Suave”) campaign for its major Hispanic YAS markets (Figure 2).122–124

FIGURE 2—

R. J. Reynolds’ “Un Tipo Suave” (“Smooth Moves”) campaign: 1989.

Source. RJ Reynolds documents.122

The effects of the Camel Hispanic program were captured by the 1989 Hispanic Tracking System, which reported that among “target 18–24 Hispanic smokers,” Camel trial and purchase levels showed steady improvements in all RJR Hispanic markets.125 Camel advertising and promotion awareness levels also increased. In several lead markets, Camel achieved levels of advertising awareness comparable to those for Marlboro. San Antonio and Houston in particular achieved the highest promotion awareness levels and, overall, the brand showed signs of growth in all of RJR’s lead Hispanic markets.122,125–127

The Smooth Moves Camel character, known as Joe Camel, was referred to as “smooth, self-confident, admired by peers, popular with women and [one that] challenges convention which [was] highly appealing to Hispanic smokers aged 18–24.”98,128 The image shown in Figure 2 intended to convey this conceptualization as well as other Hispanic smoker personality characteristics identified by RJR (Boxes 1 and 2), such as pleasure seeking and maleness, which were embedded in smoking situations relevant for Hispanics, such as driving.98,129

R. J. Reynolds’ Hispanic Psychographics and Purchase Patterns: 1984 Summary and 1987

| Psychographics |

| • Hispanics are very proud people with strong family and cultural ties. |

| • Hispanics want to perpetuate their traditions through future generations, particularly through the use of the Spanish language and traditional religious beliefs. |

| • There is a growing sense of “specialness” and unity among Hispanics. One half of all Hispanic Americans claim to be Hispanic first, American second. |

| • Hispanics are more family oriented than non-Hispanics. |

| • Hispanics share a common language. |

| Purchase patterns |

| Hispanics tend to |

| • Believe that the biggest, most popular brands are the best. |

| • Select name-brand goods over house brands. |

| • Shop at small neighborhood stores. |

| • React favorably to Spanish-oriented advertising, as long as it is executed properly. |

| • Be more concerned with getting value (quality for the price) than Americans as a whole. |

Source. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company documents.91,92

R. J. Reynolds’ Hispanic Smoker Personality Characteristics: 1982

| Characteristic | Definition |

| Sociable | Sharing and enjoying their pleasure with others is an important aspect of the Hispanic smoker’s personality. Hispanics do not lose contact with family, friends, or the Hispanic community. |

| Emotional | Hispanics overall are full of feeling, somatically inclined, easily touched, and sentimental. |

| Pleasure seeking | Hispanic smokers (particularly younger adults) devote considerable time and energy to the pursuit of pleasure, as evidenced by the many drug-, alcohol-, and sex-related anecdotes these respondents were willing to relate. |

| Polite | Being polite and considerate is very much a part of tradition-oriented Hispanic culture. Advertising that puts down or ridicules the competition or that uses boastful superlatives, often earns a negative reaction in this market. |

| Respectful | Hispanics are very respectful of others. There are some situations where smoking is generally seen as disrespectful and thus inappropriate, for instance, in front of parents or grandparents. |

| Macho | A quality with tremendous Hispanic appeal, “macho” is essential maleness. It is toughness, independence, strength, good looks, and sexiness. It is what the male wants to embody and what the female wants in her man. |

Source. Pericas.93

RJR’s 1990 Camel Hispanic program report remarked, “Hispanic consumers will enjoy and appreciate Camel’s identification of ‘their’ culture, specifically music, and will positively acknowledge Camel’s presence within their culture.”130 To convey this identification, the campaign focused on entertaining activities as an “integral portion of the Hispanic lifestyle,”130 including live music and festivals featuring Hispanic entertainers. A 1991 field marketing execution plan recommended delivering Camel activities (entertainment, retail locations, and community festivals) strategically for assimilated and nonassimilated Hispanics.131 Although the activities RJR delivered were the same activities for both groups, the company varied the exposure to these activities according to the level of assimilation. For instance, they assigned more resources to retail locations and community festivals for nonassimilated Hispanics and evenly distributed nightclub and bar activities among assimilated and nonassimilated Hispanics.131 The Smooth Moves Hispanic program executed by Promotional Marketing, Inc., involved a 14-week tour with 98 events in 10 Hispanic markets, costing approximately $796 994, whereas the overall regional initiative for the Hispanic Camel program estimated a budget of $15 508 919.130–132

R. J. Reynolds in Hispanic communities.

The company also sought to establish a presence and a positive image within the Hispanic community by developing close ties to community leaders and civic, cultural, and social organizations (e.g., the US Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, Mexican and American Foundation, Hispanic Scholarship Fund, League of United Latin American Citizens, and Hispanic members of Congress) and sponsoring local events.133–153 The company also looked to aggressively expand its participation in events that were popular with and culturally relevant for the Hispanic community such as Cinco de Mayo or San Juan Fiesta.139,148,154,155

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first substantive review of tobacco industry documents on marketing strategies to target the Hispanic population. The results of our analysis reveal that RJR developed sophisticated marketing campaigns to reach Hispanics that went beyond simple translations of materials and language considerations. The company developed special marketing strategies to reach the Hispanic community based on internal research that demonstrated that cultural values and the Spanish language were important components of Hispanics’ ethnic and cultural identification. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that using Spanish in advertisements serves to legitimize Hispanic culture in the United States156,157 and that when advertising matches cultural norms, it tends to be viewed more favorably and generate higher levels of purchase intent.158,159

RJR’s sophisticated research on Hispanics’ psychographics, cultural values, attitudes, and beliefs were translated into Hispanic marketing campaigns for Winston and Camel. These brand-specific marketing campaigns represent distinct approaches to Hispanic-targeted marketing. The message RJR conveyed in its Winston campaigns was primarily recognition, value, and pride in Hispanic heritage. By contrast, the Camel campaign and the Smooth Moves character focused on themes that were relevant to youths and less specific to Hispanic culture, such as common experiences and characteristics of adolescents and young adults.

The Winston and Camel Hispanic campaigns were executed at the same time that tobacco companies increased their spending and advertised more aggressively to reach Hispanics.160,161 In fact, RJR was among the top 10 advertising companies, and its Winston and Camel brands were among the most advertised in Hispanic markets.161,162 Evidence compiled by the Federal Trade Commission since 1990 also indicated that the Joe Camel campaign had an impact on smokers younger than the legal smoking age, and an increase in smoking incidence was observed in smoking incidence among youths.163–166 A 1993 multiethnic study of tobacco industry advertising and promotions of Joe Camel and Marlboro found that Hispanic adolescents were more likely to experiment with smoking behaviors than White, African American, and Asian adolescents.166 Evidence has shown that smoking initiation rates rose for Hispanic male adolescents between 1983 and 1986, and initiation rates for Hispanic female adolescents increased from 1984 to 1990, catching up with initiation rates among Hispanic male adolescents by 1990.167 The 1982–1984 Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey also reported high smoking rates among Hispanic males and females. Puerto Rican and Cuban males and females were more likely to be heavy smokers (smoking a pack or more a day) than Mexican Americans.6

Even after the Master Settlement Agreement in 1998, tobacco industry marketing to racial/ethnic minority groups did not decrease.168 Tobacco companies continue to try to reach the Hispanic community through corporate donations and sponsorship of cultural and community events.169,170 The Web sites of RJR’s parent company, Reynolds American, Inc., and of Philip Morris USA’s parent company, Altria Group, Inc., document ongoing support for Hispanic community nonprofits, business groups, and scholarship funds.170,171,172 The Hispanic Scholarship Fund and the Hispanic League, both nonprofit organizations, have been involved with tobacco companies for years and continue to receive funds from Reynolds American/RJR and Philip Morris.173,174 The Web site of the Hispanic League mentions that Reynolds American/RJR is represented on their 2012 board of directors. Similarly, the League of United Latin American Citizens, one of the largest Latino organizations in the United States, is a corporate partner of the Altria Group.147 These ongoing connections raise concerns about the industry’s influence on the Hispanic community.

We identified parallels between RJR’s marketing to Hispanics and how tobacco companies used targeted marketing to reach other minority or marginalized groups. Studies of responses to tobacco industry advertising in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community have found that targeted marketing is sometimes perceived as offering legitimacy and validation rather than exploitation.30,31,175 Industry’s marketing of cigarettes to those who are homeless and seriously mentally ill has been executed through developing relationships with homeless shelters and advocacy groups, which generate positive media coverage and political support for the industry.176 Likewise, Philip Morris used ethnic marketing consultants to develop psychographic profiles of African American consumers to market their products in the 1980s.34

In 2005, RJR launched another music-themed marketing campaign, similar to the Hispanic Camel campaign, to target African American and Hispanic youths. This campaign, “Kool Be True,” with the copy line “It’s about pursuing your ambitions and staying connected to your roots,” featured young, hip, multiethnic models, often with musical instruments, and appeared in magazines popular with young African Americans and Hispanics.177 Another promotional and popular music marketing effort targeted toward African Americans was Brown and Williamson’s successful “Kool Mixx” campaign. 32,178

RJR recognized that acculturation was an important concept because Hispanics, particularly new immigrants, tend to be brand loyal and willing to pay for quality products. This finding is consistent with research findings that suggest that a stronger identification with one’s ethnic culture is associated with purchasing prestige brands to convey a higher SES.179 Although brand loyalty among Hispanics may be a way to blend in to a new culture, it could also be a way for Hispanics in the United States to cope with hostility and discrimination.180,181 RJR identified discrimination as a common factor experienced by Hispanics and strategically tailored its campaigns to convey recognition and acceptance of Hispanic culture and values. This strategy was also used by RJR to target socially and economically disadvantaged young African Americans and to create a brand image that valued the African American community, offering “quality products” that were associated with success in life, social and economic status, peer recognition, acceptance, and masculinity.32 Similarly, marketing strategies for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population entailed recognition of this marginalized and discriminated community.29 Discrimination is a risk factor for multiple health outcomes and a contributing factor to health disparities among ethnic/racial groups.182 Despite the growing body of research indicating that racial/ethnic discrimination is one of the best predictors of cigarette smoking among Hispanics and African Americans, smoking cessation interventions have not yet addressed discrimination and cultural rejection in the treatment of minority and immigrant groups.183–186

The impact of targeted marketing on Hispanics is complicated by varying degrees of acculturation exhibited by Hispanics that influence how they respond to ethnic cultural cues in advertising.187 Hispanic acculturation patterns have been found to be associated with variations in media use, response to direct marketing and digital advertising, and purchase behaviors.188,189 Hispanic consumers may respond more effectively to conventional ads targeted toward Whites, to bicultural ads, or to ads targeted toward Hispanics, depending on their acculturation status. At the same time, however, shared Hispanic cultural values have been found to influence smoking behavior. Respeto (respect for authorities) has been associated with a lower risk of cigarette use, whereas fatalismo (fatalism) has been associated with a higher risk of cigarette use and a lower perception of the benefits of quitting smoking.190,191 Familismo (family orientation) and simpatia (harmonious social relationships) have been found to be important predictors for considering quitting smoking (e.g., being a good role model for children, worrying about damaging children’s health, avoiding being criticized by family). 11,192 Additionally, perception of smoking as a socially desirable behavior specifically for male smokers has been found to be an important barrier to quitting smoking for Hispanics.11, 192, 193

In light of the evidence presented, the need to understand the diverse influences on tobacco use behavior among Hispanics continues to pose important questions for researchers and public health professionals. Our analysis suggests that RJR was investigating similar questions decades ago. The public health community has lagged behind the tobacco industry in monitoring smoking behavior among Hispanics. Before 1978, major US government databases and surveys limited race and ethnicity classifications to White and Black.5 In 1998, the National Institutes of Health highlighted the lack of national-level data for specific Hispanic subgroups, and only in the mid-1980s was a large enough national survey sample of Hispanics available so that measuring long-term trends in smoking prevalence could begin.5,194 Today, most national- and state-level cancer statistics are still collected only on Hispanics as an aggregate group.195 By contrast, RJR made use of detailed research information about Hispanics’ country of origin, geographic region, immigration status, education, SES, and acculturation levels. This comparison points to the importance of collecting and analyzing disaggregated data on Hispanics in national population tobacco surveys.196

Today the Hispanic market is one of the fastest growing segments in the multicultural US marketplace, with a projected purchasing power of $1.3 trillion by 2015.197–200 Despite recent economic recessions and a decline in immigration, Hispanics will still account for about 60% of the growth in the US population over the next 5 years.200 Numerous major marketers (e.g., Coca-Cola, Walmart, General Mills) have established marketing divisions dedicated to Hispanic consumers, recognizing that they are a primary driver of growth, essential for the future success of their companies. 169,198–200 Thus, Hispanics’ demographic and economic trends position them as promising current and future market opportunities for tobacco companies.169 Therefore, it is important for tobacco control researchers, public health advocates, and policymakers to closely monitor the evolving sociodemographic and economic characteristics of the Hispanic population in parallel with new tobacco products, strategies, and techniques used by tobacco companies. For up-to-date information on tobacco industry products and marketing strategies, it could be particularly valuable to monitor trends in new technologies and forms of media (e.g., Internet cigarette vendors) as well as models and techniques derived from modern marketing research.

An important lesson derived from this research is the need to keep pace with current marketing initiatives implemented in the corporate world. We found that some of the underpinnings of marketing directed toward Hispanics were not exclusive to tobacco companies but were based on thorough marketing research on Hispanic consumer behaviors that was successfully applied by other industries. Our findings also underline the need to investigate further how tobacco companies are reaching the Hispanic community in the current market environment. Given the importance of the Hispanic population for the future of this nation and the devastating consequences that tobacco companies and their products inflict not only on the health of individuals but on entire communities and countries, efforts by tobacco control researchers and the public health community at large should focus on the young and growing Hispanic population.

Acknowledgments

No funding was obtained for this study. During the work on this study, both authors were affiliated with the Tobacco Control Research Branch of the National Cancer Institute. None of the authors has a conflict with any aspect of the study.

Human Participant Protection

No institutional review board approval was needed because the research did not involve human participants.

References

- 1.US Census Bureau 2010 Census shows America’s diversity. Available at: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb11-cn125.html. Accessed April 10, 2011

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 2005-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(35):1207–1212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trinidad DR, Pérez-Stable EJ, Emery SL, White MM, Grana RA, Messer KS. Intermittent and light daily smoking across racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(2):203–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trinidad DR, Pérez-Stable EJ, White MM, Emery SL, Messer K. A nationwide analysis of US racial/ethnic disparities in smoking behaviors, smoking cessation, and cessation-related factors. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):699–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services Tobacco Use among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haynes SG, Harvey C, Montes H, Nickens H, Cohen BH. Patterns of cigarette smoking among Hispanics in the United States: results from HHANES 1982-84. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(suppl):47–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caraballo RS, Yee SL, Gfroerer J, Mirza SA. Adult tobacco use among racial and ethnic groups living in the United States, 2002-2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(3):A78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pérez-Stable EJ, Ramirez A, Villareal Ret al. Cigarette smoking behavior among US Latino men and women from different countries of origin. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1424–1430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unger JB, Cruz TB, Rohrbach LAet al. English language use as a risk factor for smoking initiation among Latino and Asian American adolescents: evidence for mediation by tobacco-related beliefs and social norms. Health Psychol. 2000;19(5):403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tobacco use among adults: United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(42):1145–1148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter-Pokras OD, Feldman RH, Kanamori Met al. Barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation among Latino adults. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(5):423–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reed MB, Burns DM. A population-based examination of racial and ethnic differences in receiving physicians’ advice to quit smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(9):1487–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Quintero C, Crum RM, Neumark YD. Racial/ethnic disparities in report of physician-provided smoking cessation advice: analysis of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2235–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levinson AH, Pérez-Stable EJ, Espinoza P, Flores ET, Byers TE. Latinos report less use of pharmaceutical aids when trying to quit smoking. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(2):105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Health and Human Services Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. High-risk behaviors associated with early smoking: results from a 5-year follow-up. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(6):465–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly S. The psychological consequences to adolescents of exposure to gang violence in the community: an integrated review of the literature. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;23(2):61–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griesler PC, Kandel DB. Ethnic differences in correlates of adolescent cigarette smoking. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23(3):167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Tobacco Control Monograph no. 19. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2008. Available at: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/tcrb/monographs/19/m19_complete.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tharp M. Marketing and Consumer Identity in Multicultural America. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Primack BA, Bost JE, Land SR, Fine MJ. Volume of tobacco advertising in African American markets: systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(5):607–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Dauphinee AL, Fortmann SP. Targeted advertising, promotion, and price for menthol cigarettes in California high school neighborhoods. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):116–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen EL, Caburnay CA, Rodgers S. Alcohol and tobacco advertising in Black and general audience newspapers: targeting with message cues? J Health Commun. 2011;16(6):566–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez S, Hickman N, Klonoff EAet al. Cigarette advertising in magazines for Latinas, White women, and men, 1998–2002: a preliminary investigation. J Community Health. 2005;30(2):141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grier SA, Kumanyika S. Targeted marketing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31(1):349–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grier SA, Brumbaugh AM. Noticing cultural differences: ad meanings created by target and non-target markets. J Advert. 1999;28(1):79–83 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grier SA, Deshpande R. Social dimensions of consumer distinctiveness: the influence of social status on group identity and advertising persuasion. J Mark Res. 2001;38(2):216–224 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith EA, Malone RE. Tobacco promotion to military personnel: “the plums are here to be plucked.” Mil Med. 2009;174(8):797–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevens P, Carlson LM, Hinman JM. An analysis of tobacco industry marketing to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) populations: strategies for mainstream tobacco control and prevention. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(3 suppl):129S–134S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Washington HA. Burning love: Big Tobacco takes aim at LGBT youths. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(7):1086–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith EA, Malone RE. The outing of Philip Morris: advertising tobacco to gay men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):988–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balbach ED, Gasior RJ, Barbeau EMRJ. Reynolds’ targeting of African Americans: 1988–2000. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):822–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson SJ. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii20–ii28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yerger VB, Przewoznik J, Malone RE. Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(4 suppl):10–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West JH, Romero RA, Trinidad DR. Adolescent receptivity to tobacco marketing by racial/ethnic groups in California. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2):121–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X, Cruz TB, Schuster DV, Unger JB, Johnson CA. Receptivity to protobacco media and its impact on cigarette smoking among ethnic minority youth in California. J Health Commun. 2002;7(2):95–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim J-S, Zalloccoab R, Ghingolde M. Segmenting the Hispanic market based on ethnic origin and identity: an exploratory study. J Segmentation in Marketing. 1997;1(2):17–39 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker BJ. The consumer behavior of Hispanic populations in the United States. J Segmentation in Marketing. 2000;3(2):61–78 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alaniz LP, Gay MC. The Hispanic family-consumer research issues. Psychol Marketing. 1986;3(4):291–304 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmen GR. Winston special marketing effort. August 21, 1969. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 500782890/2894. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wfi69d00. Accessed January 3, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esty W. Winston 1972 media objectives and spending strategy (720000). August 24, 1971. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 500729229/9238. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/amm69d00. Accessed January 3, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42. RJ Reynolds. Statement of business. September 30, 1971. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 500099831/9856. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fsx89d00. Accessed January 3, 2012.

- 43. RJ Reynolds. A study of ethnic markets. September 1969. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 501989230–501989469. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aze37b00. Accessed January 3, 2012.

- 44. Kenneth Hollander, Associates, Inc. Hispanic smoker study. September 1979. Brown & Williamson Tobacco. Bates no. 670651272. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zxb86b00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2012.

- 45.Burnett L. Letter re: the Hispanic market in the United States, to Mr. James Thompson. Philip Morris USA. September 4, 1975. Bates no. 1002485561–1002485562. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lsp76b00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson SJ, McCandless PM, Klausner K, Taketa R, Yerger VB. Tobacco documents research methodology. Tob Control. 2011;20(suppl 2):ii8–ii11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control. 2000;9(3):334–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bero L. Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24(1):267–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balbach ED, Gasior RJ, Barbeau EM. Tobacco industry documents: comparing the Minnesota depository and Internet access. Tob Control. 2002;11(1):68–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirschhorn N. The Tobacco Industry Documents: What They Are, What They Tell Us, and How to Search Them: A Practical Manual. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; Available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/communications/TI_manual_content.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson SJ, Dewhirst T, Ling PM. Every document and picture tells a story: using internal corporate document reviews, semiotics, and content analysis to assess tobacco advertising. Tob Control. 2006;15(3):254–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. RJ Reynolds. Spanish overview. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. February 1, 1975. Bates no. 500765149/5157. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fhk69d00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 53. RJ Reynolds. Spanish market study. 1975. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 502313027/3043. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vhk19d00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 54.Nordine RC, UNK. Hispanic opportunity in the 1980’s (800000). May 5, 1981. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 501972002. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lno29d00. Accessed January 3, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leiber CL. Hispanic marketing. May 1, 1984. Philip Morris USA. Bates no. 2044846510. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hsy76b00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leiber CL. Hispanic marketing action plan. May 29, 1984. Philip Morris USA. Bates no. 2049390065–20493900. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ckx76b00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leiber CL. Hispanic marketing action plan. April 4, 1985. Philip Morris USA. Bates no. 2049000086/0087. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bfj93e00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Donnelly Marketing. Lorillard Hispanic field promotion proposal. December 16, 1983. Lorillard. Bates no. 85280054/0075. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nap44c00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 59. Catli and Associates. Lorillard Newport Green 830000. US Hispanic sales promotion. Hispanic night club recommendation, New York market. March 2, 1983. Lorillard. Bates no. 85280119/0134. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gds00e00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 60. Hispanic marketing fundamentals. 1989. Lorillard. Bates no. 93376305/6308. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xtp60e00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 61. Strategy Research Cooperation. 1985 Hispanic smoker study, Miami. September 17, 2009. Brown & Williamson. Bates no. 465969505–465969621. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fcq76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 62. Tobacco Industry Monitoring Project. Why B&W is entering the Hispanic segment. January 1, 1984. Bates no. 679154329–679154347. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xku76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 63.Harden RJ. Strategic research in-depth-analysis. “The Hispanic market opportunity in the1980’s (800000).” New business research and development report. May 5, 1981. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 501438396/8433. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qnc49d00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mercadotecnia Consulting. Understanding the US Hispanic marketplace. February 1985. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 504616859–6911. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zrz76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 65. Mercadotécnica Consulting. 1987 (870000) US Hispanic market study. General. Understanding the US Hispanic marketplace(s), executive compendium report. February 1985. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507395881/5890. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dry24d00;jsessionid=14551CAEC344E63F5863359B27690E7F. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 66. Field manager’s orientation. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507132879/3024. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/grx62d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 67. Yankelovich Market Development. Hispanic monitor. The first comprehensive understanding of the Hispanic market. March 15, 1988. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507185030/5033. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uhr93a00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 68. William Esty Company. August 21, 1969. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 500782890/2894. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wfi69d00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 69. Hispanic Cigarette Tracking Study: Quality assurance report. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 503504223/4238. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rwc95d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 70. William Esty Company. Letter to WK Neher RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company re: Salem Hispanic agency marketing segment analysis/perspective. Bates no. 505428252/8270. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lnx15d00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 71. SSOS Spanish-speaking omnibus survey. April 1980. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2040340960/0963. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bis31b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 72. Definition and general discussion of segments. January 21, 1982. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 502671478/1549. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uzl78d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 73. Burke Marketing Research. 1982 (820000) Hispanic cigarette tracking study omnibus. 1982. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. Bates no. 503392914/2961. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ttl95d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 74. Spanish-speaking omnibus survey. April 1980. Philip Morris. Bates no. 2042789837/9846. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yaz55e00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 75. Hispanic cigarette tracking study: quality assurance report. July 20, 1983. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Control. Bates no. 503392409/2433. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cem95d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 76.Mabee LP. Black and Hispanic research studies 1982-1984. December 21, 1983. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 502061095/1096. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zng29d00. Accessed January 3, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 77. RJ Reynolds. Consumer tracking user guide table of contents. 1982. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505583751/3885. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rpg15d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 78.Hall LW, Jr, Johnston JW, Lees HJet al. Marketing research proposal (MDD #82-28106). Hispanic consumer tracking study. March 23, 1982. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 503516076/6078. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rwb95d00. Accessed January 3, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pasterczyk RC. Consumer research report. Consumer performance in major Hispanic markets. July 20, 1984. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 502672231/2251. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zam78d00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pasterczyk RC. Consumer research report. Consumer performance in major Hispanic markets. July 20, 1984. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 502224443. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wbr19d00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barnes ML, Mabee LP, Whitlatch WPet al. Consumer tracking proposal (MDD #83-32701) Hispanic consumer tracking study. April 29, 1983. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 501890779/0781. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rlv29d00. Accessed January 3, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 82. Winston information. Business analysis. Analysis of Winston for 1989 plan. March 10, 1989. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507830363/0371. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uqw28c00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 83. Younger adult smokers: strategies and opportunities. February 29, 1984. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 502411168/1262. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aey52d00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 84. M/A/R/C Inc. RJR national brand tracker 1990. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 513890004/0070. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/edn13d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 85. Market Development, Inc. Analysis of selected data from the Hispanic tracking system. February 15, 1990. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507281712/1746. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cag54d00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 86. Agenda. 1970. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 506041026/1057. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bqc05d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 87.McCann R. 1981 market overview: product perspective by segment. 1982. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 500119052–9057. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ebv89d00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barbeau EM, Leavy-Sperounis A, Balbach ED. Smoking, social class, and gender: what can public health learn from the tobacco industry about disparities in smoking? Tob Control. 2004;13(2):115–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pericas J. Analysis of the MDD Segmentation Study Among Hispanic Smokers (MDD #82–21703) Management Summary. February 18, 1982. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 503516112/6113. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/twb95d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 90. Mercadotecnica Consulting. Executive compendium report. Understanding the US Hispanic marketplace(s) (Project code no. 85–449MC). February 1985. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 506600469/0479. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uzz44d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 91. Spanish USA, 1984 summary. 1984. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 504616837/6839. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wnf65d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 92.Jones YM. Previous Hispanic research. December 16, 1987. Mangini, RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507129143/9151. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eqz62d00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 93. [Exploratory market of Hispanic smokers]. Mangini, RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507132498/2425. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tha72d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 94. Research Resources. An exploratory study conducted among US Hispanics. February 1988. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507185495/5529. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/len54d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 95. MRD Pres. to CWF. Hispanic market learning. 1989. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507135127/5159. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wxg34d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 96. Hispanic agency orientation. Mangini, RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507135341/5417. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lzx62d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 97. Marketing general. Hispanic marketing considerations. 1985. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 506600725/0733. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gaa54d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 98. RJ Reynolds. RJ Reynolds research summary. September 1991. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 509219140/9144. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xcw73d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 99. American Tobacco. The Mexican/American Market—Los Angeles. Bates no. 966050899/0908. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fua70a00/pdf. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 100. RJ Reynolds. Hispanic Market Project. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505729020/9053. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mvw05d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 101. RJ Reynolds. Opportunity Assessment Hispanic Market. RJ Reynolds. Bates No. 523611323–1385. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yrk99i00/pdf. Accessed February 25, 2013.

- 102. National Family Opinion. Hispanic assimilation analysis. Hispanic adult smokers, aged 18–24. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 509162818/2868. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/szz73d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 103. RJ Reynolds. Hispanic agency orientation. Mangini, RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 506864316/4317. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kwa72d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 104. RJ Reynolds. Winston (April 29, 1988). Background. Positioning statement. March 14, 1988. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 530559707–9740. Available at: ttp://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kck03h00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 105.Harris TC. Copy strategy. December 3, 1986. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505462668. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ymt15d00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 106. Winston “real people” advertising. 1987. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 506743315/3318. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rod28c00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 107. Winston 1987. Annual marketing plan. 1987. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 509240348/0415. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/krv73d00.

- 108. Winston advertising target. 1985. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 506749165/9169. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hbe28c00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 109. Winston “real people” campaign. December 10, 1986. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507091901/1914. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/irf28c00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 110. RJ Reynolds, Carvajal M. Winston Hispanic focus groups. Advertising research report. October 3, 1986. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505729098/9115 Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qvw05d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 111. RJ Reynolds, Brassel EJ. Marketing research report. Winston “Nuestra Gente” Hispanic focus groups. March 13, 1987. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505729752/9764. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lyw05d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 112. Winston. 1988. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507135329/5340. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iyg34d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 113. Research Resources Hispanic Division. An exploratory study conducted among US Hispanics. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507279132/9171. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iig54d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 114.I MLS, Alcazar DA. Hispanic copy recommendation. April 22, 1987. Bates no. 507093550–3551. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ahd93i00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 115.McCann E, Orci HJ. Recommendations with regard to the six Hispanic focus groups held in Los Angeles and San Antonio, September 16–18. September 25, 1986. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505336550/6554. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lli25d00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Alcazar DA. Hispanic campaign recommendation. March 12, 1987. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 506741224/1225. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tjv56a00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 117. RJ Reynolds, Brassel EJ. Advertising research report. DAR test—final report. Winston “real people” advertising. July 13. 1987. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505729663/9680. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dyw05d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 118. RJ Reynolds, Brassel EJ. Advertising research report. OOH Test—Final report. Winston “Real people” advertising. May 5, 1987. RJ Reynolds. Bates No. 505729611/9629. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/byw05d00. Accessed February 25, 2013.

- 119. Hispanic market 1990 business plan. Bates no. 509034823–509034842. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/icl76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 120. 1990 Planning Hispanic market. Bates no. 507767543–507767613. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dal76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 121. RJ Reynolds, Brassel EJ. Advertising research report. OOH test—final report. Winston “real people” advertising. May 5, 1987. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505729611/9629. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/byw05d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 122. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Un tipo suave [advertisement]. 1990. Available at: http://tobaccodocuments.org/pollay_ads/Came47.08.html. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 123. Camel 1985 annual marketing plan business analysis. 1985. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 502656160/6238. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pnn78d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 124. The Hispanic recommendation. 1989. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507102874–507102952. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qvk76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 125. Promotional Marketing Inc. Camel Hispanic field marketing program. Entertainment concepts. January 25, 1990. Promotional Marketing Inc., RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507358012–507358025. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qxk76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 126. Camel business analysis. Special market analysis—Hispanic smoker market. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 504613146/3157. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wrf65d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 127.Bellis JV. Camel regular growth in Hispanic markets. January 12, 1990. Bates no. 507300389. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kxk76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 128. Contemporary heroic Camel. Mangini. Bates no. 506752773/2778. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xpa72d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 129. Market Development, RJ Reynolds. Qualitative research: Hispanic lifestyles smoking behaviors, and attitudes towards smoking. Bates no. 509162869–509162967. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ucl76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 130. Camel Hispanic program. February 15, 1989. Mangini. Bates no. 507133229/3239. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xrx62d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 131. Promotional Marketing Inc. Regional initiative program 1991(910000) field marketing execution plan. September 25, 1990. Marketing to women. Bates no. 507572753–507572773. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/szk76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 132. Promotional Marketing Inc. Camel Hispanic program. Hispanic “smooth moves” execution recommendation. May 1, 1989. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 506882400–506882413. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lvk76b00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 133. 1984 (840000) corporate Hispanic promotion summary. January 1, 1983. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 503741908/1921. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xnj85d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 134. Candelaria, Hispanic American Chamber of Commerce. The Hispanic-American Chamber of Commerce is an organization of businesses, individuals, and institutions committed to developing the Hispanic market in the Northeast U.S. September 5, 1996. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 503741908/1921. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ddf60d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 135. RJ Reynolds, Annese BJ. It was a distinct pleasure to meet you today at the US Chamber of Commerce luncheon hosted by our company. February 22, 1994. RJ Reynolds. Bates no. 518282092. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qri97c00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 136. US Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, Franci JI. On behalf of the United States Hispanic Chamber of Commerce board of directors and staff, I would like to express the importance with which the USHCC views its partnership with RJ Reynolds. May 16, 1996. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 522523456. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kud60d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 137.Bonilla H. Congress. I want to thank you for taking part in my “San Antonio Fiesta” fundraiser on September 22nd. October 6, 1999. RJ Reynolds. Bates no. 525920682. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zmj60d00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 138. RJ Reynolds. It was very good to see you on my recent trip to New York. February 9, 1982. Bates no. 505469299. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yrs15d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 139. RJ Reynolds. New York—for the sixth consecutive year, Winston cigarettes will sponsor the San Juan Fiesta—the largest Hispanic festival in the United States which draws crowds of more than 200,000 to Central Park. February 18, 1982. Bates no. 500841956/1957. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kpd69d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 140.Breininger LJ, Lindquist WS, RJR Nabisco. Accounts payable voucher. Corporate membership/dues to Mexican and American Foundation, Incorporated. June 13, 1989. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 508761687/1690. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hxd55a00. Accessed January 3, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lewis CE. Weekly report—week of May 10–May 16, 1985. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505476771–6771. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lce93i00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gonzalez CH, Valencia A, Fuentes G. Mexican & American Foundation. We would like to take this opportunity to congratulate you on being elected to the 1991(910000) board of trustees of the Mexican and American Foundation. January 22, 1991. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507763417. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mxv28c00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 143. Reynolds RJ, Gomez H, Suggs ML. ERB—generate accounts payable transactions. external relations a/p vouchers. Artec Hispanic Scholarship Fund. voucher request. June 12, 1996. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 518283269/3270. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ycf60d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 144. RJ Reynolds, RJR Nabisco, Planters, Nabisco. Drive recognizes no limits to learning. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507749337. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tys14d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 145.Gomez H. Voucher request. Event name and description: scholarship contribution to the USHCC Florida director office. March 12, 1996. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 522523439/3442. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/akc92a00. Accessed January 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 146. Ft. Lauderdale field pres. Hispanic recommendation marketing recommendations. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507135202/5235. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zxg34d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 147. League of United Latin American Citizens. Available at: http://lulac.org/. Accessed September 17, 2012.

- 148. Hispanic market field marketing activity. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507133333/3344. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/edh34d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 149. RJR Nabisco. We want women of color to have less. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505478213/8214. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/urr15d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 150. 1983 (83000) Hispanic World’s Fair—New York City. August 2, 1982. RJ Reynolds. Bates no. 503924552. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yvr75d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 151. Young & Rubicam. The Bravo Group. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. Corporate Hispanic program credentials presentation. February 22, 1991. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507785615/5710. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tfp14d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 152. Oglesby MB, RJ Reynolds, Foreman DD. Weekly status report—government relations. November 16, 1990. RJ Reynolds. Bates no. 507628748/8750 Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rve24d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 153.Palumbo B, Palumbo & Cerrell. With respect of my assignment to recommend a public affairs program for RJ Reynolds for the Hispanic community the following market data may be of interest. November 8, 1983. RJ Reynolds. Bates no. 500634889/4895. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mnt69d00. Accessed January 3, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 154. Promotion Resources. 1987 (870000) Winston (Hispanic) Fiesta San Antonio. December 18, 1986. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 505682716/2726. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hlu18c00;jsessionid=705E99A5C0BEC0047F18C61BEA061D8F.tobacco03. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 155. Hispanic recommendation agenda. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. Bates no. 507185425/5465. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hen54d00. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- 156.Peñaloza L. Atravesando fronteras/border crossings: a critical ethnographic exploration of the consumer acculturation of Mexican immigrants. J Consum Res. 1994;21(1):32–54 [Google Scholar]

- 157.Peñaloza L. Immigrant consumers: marketing and public policy considerations in the global economy. J Public Policy Marketing. 1995;14(1):83–94 [Google Scholar]

- 158.Torres IM, Gelb BD. Hispanic-targeted advertising: more sales? J Advert Res. 2002;42(6):69–75 [Google Scholar]

- 159.Gregory GD, Munch JM. Cultural values in international advertising: an examination of familial norms and roles in Mexico. Psychol Marketing. 1997;14(2):99–119 [Google Scholar]