Abstract

Objectives. We determined the acceptability, participants' receptivity, and effectiveness of a culturally adapted version of Real Men Are Safe (REMAS-CA), an HIV prevention intervention for men in substance abuse treatment.

Methods. In 2010 and 2011, we compared participants who attended at least 1 (of 5) REMAS-CA session (n = 66) with participants in the original REMAS study (n = 136). Participants completed an assessment battery at baseline and at 3-month follow-up with measures of substance abuse, HIV risk behaviors, perceived condom barriers, and demographics. We conducted postintervention focus groups at each clinic.

Results. Minority REMAS-CA participants were more likely to have attended 3 or more sessions (87.0%), meeting our definition of intervention completion, than were minority participants in the REMAS study (75.1%; odds ratio = 2.1). For REMAS-CA participants with casual partners (n = 25), the number of unprotected sexual occasions in the past 90 days declined (6.2 vs 1.6). Among minority men in the REMAS study (n = 36), the number of unprotected sexual occasions with casual partners changed little (9.4 vs 8.4; relative risk = 4.56).

Conclusions. REMAS-CA was effective across ethnic groups, a benefit for HIV risk reduction programs that serve a diverse clientele.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that African Americans and Hispanics are overrepresented among men with HIV infection in comparison with Whites.1 African Americans and Hispanics each account for 13% of the total population in states monitored by CDC, but account for 43.9% and 19.6%, respectively, of HIV infections among men. Whites make up 72% of the population, but only 34.5% of the HIV infections among men.

DISPARITIES IN AN EFFECTIVE INTERVENTION

The Clinical Trials Network (CTN) of the National Institute on Drug Abuse recently completed a randomized clinical trial evaluating the utility of Real Men Are Safe (REMAS), an HIV prevention intervention for men in substance abuse treatment. Men randomized to the 5-session REMAS groups engaged in fewer unprotected vaginal and anal intercourse occasions during the 90 days prior to the 3- and 6-month postintervention follow-ups than did men randomized to a standard single-session HIV education group.2 Previous research had indicated that most substance abuse treatment programs provide only a 1-hour HIV education intervention.3,4 In addition, men who received REMAS were less likely to have engaged in sexual intercourse under the influence of drugs or alcohol during the most recent sexual encounter prior to the 3-month follow-up than were men who received standard HIV education.5 Thus, REMAS appeared to be effective at reducing unprotected intercourse occasions and sexual intercourse under the influence among treatment-seeking men in both methadone and outpatient psychosocial programs.

The study sample was 30% African American and 12% Hispanic. We subsequently examined the data from an ethnicity perspective. Although the study was not powered to detect ethnic differences in effectiveness of the REMAS intervention, post hoc analyses on a key outcome measure, condom use with casual partners, suggested that Whites benefited more from the intervention than did African Americans. Indeed, the overall percentage of REMAS participants who used condoms for more than 80% of all casual-partner vaginal and anal intercourse occasions increased from baseline to the 3-month follow-up by 34%, but only 21% for the HIV education group.2 From baseline to the 6-month follow-up, the increase in the percentage of participants reporting frequent condom use with casual partners was smaller but also quite different between conditions: 17% for REMAS and 2% for HIV education participants.

However, a closer look at ethnicity revealed that for White REMAS attendees, frequent condom use with casual partners increased from 5.8% at baseline to 38.9% at the 6-month follow-up; the increase among African Americans was a nonsignificant 11.1% to 22.2%.6 Although the sample size was insufficient to evaluate increased condom use with casual partners among Hispanic men, the data indicated that none of the Hispanic REMAS participants who completed the 6-month follow-up were using condoms frequently with their casual sexual partners. These results suggested a differential effect for White and minority men.

CULTURAL ADAPTATION

Bernal and Scharrón-del-Rio7 and Hall8 have noted that a shortcoming of many evidence-based treatments is the failure to demonstrate efficacy with ethnic minorities. The American Psychological Association Division 12 Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures has recommended that more research be conducted to assess the effectiveness of interventions with ethnic minorities that have been found to be effective with White samples.9 Meta-analyses have indicated that HIV prevention efforts can be effective with African American and Hispanic populations.10,11 Some of the interventions associated with increased efficacy for sexual risk reduction are theory driven, conduct ethnographic research to inform intervention development, or are culturally tailored.10 Darbes et al.11 identified the following intervention characteristics to be associated with efficacy: cultural tailoring, influence on social norms to promote safe sex behavior, peer education, skills training on correct use of condoms and negotiation of safer sex, multiple treatment sessions, and opportunities to practice learned skills. Similarly, meta-analyses of studies of HIV risk reduction interventions conducted in drug abuse treatment programs have shown them to be effective, particularly if they contain attitudinal arguments, educational information, behavioral skills arguments, and behavioral skills training.12,13 Of specific interest to the REMAS studies were positive correlations reported for intensity of the intervention (multiple sessions), use of peer group discussion, and conducting separate sessions for men and women.

The REMAS intervention incorporated all of these components (multiple sessions, peer group discussion, and gender-specific education sessions) and had informational, motivational, and behavioral skill components (condom use, safe sex negotiation) consistent with the information–motivation–behavioral skills model of HIV prevention.14 Clearly missing from REMAS, however, were culturally tailored elements designed for African American and Hispanic populations. Because African American and Hispanic men are overrepresented among HIV-positive individuals, and because substance use is an important risk factor for HIV infection, a REMAS revision could exert a large positive impact on HIV sexual risk reduction among African American and Hispanic men attending substance abuse treatment. Improving on REMAS to make it more effective for these men could reduce new HIV and other sexual transmitted infections among them and their sexual partners. Improving REMAS could also reduce HIV infection among the communities in which these men reside because 54% of participants’ sexual partners were not high risk partners (defined as individuals who were injecting drugs or smoking crack cocaine; were exchanging sex for money, drugs, or other financial considerations; or were HIV positive).

We revised REMAS to be more culturally relevant to African American and Hispanic participants.6 Real Men Are Safe–Culturally Adapted (REMAS-CA) is approximately one third new, one third revised to be more culturally relevant, and one third unchanged.

The all-new modules share a stronger focus on understanding how each man’s cultural and socialization experiences contribute to his past and current sexual behavior. The focus on the importance of culture is sufficiently broad in REMAS-CA that each participant can bring into the session the aspects of his culture that are important to his sense of self. Although culture is often viewed in racial or ethnic terms, participants are invited to focus on other aspects of their cultural heritage, which might include religious affiliations, neighborhoods, or other social groups that influence how they currently view themselves. We hoped REMAS-CA could be sensitive to African Americans and Hispanics but not be limited to them; we strove for a culturally sensitive intervention that could be used with any male substance-abusing population. We deleted some modules to make room for the new ones, because the content of the deleted modules was likely to be offered through existing clinic programming or their content appeared in other REMAS-CA modules. A more detailed description of the revisions to REMAS to create REMAS-CA is provided elsewhere.6

We conducted a pilot feasibility trial of REMAS-CA in 4 community treatment programs (CTPs) within the National Institute on Drug Abuse CTN that had traditionally enrolled a high percentage of African American or Hispanic men. The goals of the pilot testing were to (1) determine acceptability of and participants' receptivity to the intervention and (2) assess any change in sexual risk behavior to estimate effect size for a larger clinical trial.

METHODS

To be eligible to participate, a clinic needed to meet the following criteria: (1) have a high percentage of African American or Hispanic men in its patient population; (2) have 2 counselors willing to be trained to deliver REMAS-CA, one of whom must be African American or Hispanic; and (3) be willing to have REMAS-CA serve as the HIV intervention for patients choosing to participate in the study. The opportunity for CTPs to participate in the study was announced during a national CTN steering committee meeting. Twelve CTPs expressed interest and completed an informational questionnaire. We selected 7 CTPs for a conference call interview. We then made in-person visits to 4 sites. After successful site visits, we selected all 4 of these sites for participation. Two sites provided opioid agonist therapy (Matrix Institute, Los Angeles, CA, and Hartford Dispensary, Hartford, CT). The other 2 sites provided psychosocial treatment programs offering a wide variety of treatment options, with most participants recruited from their intensive outpatient treatment programs (Lexington–Richmond Alcohol and Drug Abuse Council, Columbia, SC, and The Life Link, Santa Fe, NM). The study was conducted between April 2010 and June 2011.

Recruitment and Training

We recruited participants with procedures used in the CTP for other CTN studies. These included posting of flyers, announcement in treatment groups, and informational handouts from treatment staff. Inclusion criteria were being (1) male, (2) aged at least 18 years, (3) sexually active in the past 90 days, (4) willing to attend REMAS-CA groups and follow-up focus groups concerning REMAS-CA, and (5) willing to complete baseline and 3-month follow-up assessments. Each site had a recruitment target of 24, ideally with 3 cohorts of 8 men per cohort. Each cohort was to have at least 50% African American or Hispanic men. One site met the initial recruitment target plus 2 additional participants. Two sites recruited 24 participants in 4 cohorts. The final site recruited 21 participants in 4 cohorts. The total sample consisted of 95 men.

We screened participants indicating an interest in the study with the CTN demographic form (with questions added about plans to stay in the local area until the 3-month follow-up date) and the HIV Risk Behavior Scale.15 We administered a shortened version of the Sexual Behavior Inventory used in the original REMAS study to participants meeting eligibility criteria.2 We administered the inventory in an audio computer-assisted structured interview, which we repeated 3 months after participants attended the REMAS-CA sessions. The primary outcome measure obtained from the inventory was the number of unprotected vaginal and anal intercourse occasions in the past 90 days. Secondary measures were number of sexual partners in the past 90 days (both regular and casual partners), percentage of condom use in the past 90 days and during the most recent sexual event, and sexual intercourse under the influence of drugs or alcohol in the past 90 days and during the most recent sexual event. In addition, we administered the Condom Use Scale from CTN0018,16 and the Condom Barriers Scale17 to assess condom use skills and attitudes toward condoms.

Counselors in the CTP chosen to be the REMAS-CA interventionists attended a centralized 2-day training session (conducted by D. A. C. and M. A. H.-M., who also led the interventionist training in the original REMAS study). We used the same counselor certification processes as in the original REMAS study,2 except that certification sessions could be completed upon return to the home clinics. Counselors submitted audio recordings of 1 full session of REMAS-CA and 2 additional modules, which we reviewed for competency according to a standardized rating scale.

Pilot Study

The 5 intervention sessions each ran 90 minutes and took place approximately twice per week over 2 to 3 weeks. All groups were audiotaped, and we followed the fidelity-monitoring procedures from the original study to ensure that counselors delivered the intervention as intended. We rated 20% of the intervention sessions. On the summary rating of overall session fidelity and competence, all sessions received at least a minimum competency rating established a priori of 3 (adequate) on a 1 to 5 scale. We conducted monthly counselor supervision conference calls with all sites.

Our analyses first calculated effect sizes for change from baseline to 3 months for REMAS-CA participants. Effect sizes were changes in proportions for dichotomous outcomes and Cohen’s d for continuous outcomes. We then compared ethnic minority participants from the REMAS-CA and REMAS studies. Regression analysis predicted each follow-up outcome by study (REMAS = 1 vs REMAS-CA = 0), with control for baseline scores on the outcome. We used linear and logistic regressions for continuous and dichotomous outcomes, respectively. Poisson regression adjusted for overdispersion showed good fit to count outcomes, and we therefore applied it in those cases.

Focus Groups

We invited the final cohort at each site to participate in a focus group approximately 2 weeks after completing REMAS-CA, conducted by D. A. C. and either A. K. B. or M. A. H.-M., to elicit feedback about the program. Our approach to conducting the groups was collaborative action research, as described by Miles and Huberman,18 in which researchers and participants work closely together to change the social environment, in this case the REMAS-CA intervention. Open-ended questions focused on both the total REMAS-CA package and specific modules. Questions included

What did you like or not like about REMAS-CA and its specific modules?

Which REMAS-CA modules were the most relevant to your own personal situation or to people whom you know well in treatment?

Which REMAS-CA modules did you find hard to relate to your own personal situation or to the situations of people whom you know well in treatment?

What suggestions do you have for improving REMAS-CA, including module removal or module revision?

What is missing from REMAS-CA?

Immediately after each focus group, the moderators completed a contact summary sheet and reviewed their notes with the rest of the investigative team. We audiotaped all focus groups and reviewed the tapes; we then constructed a list of strengths and concerns expressed in the groups about REMAS-CA.

RESULTS

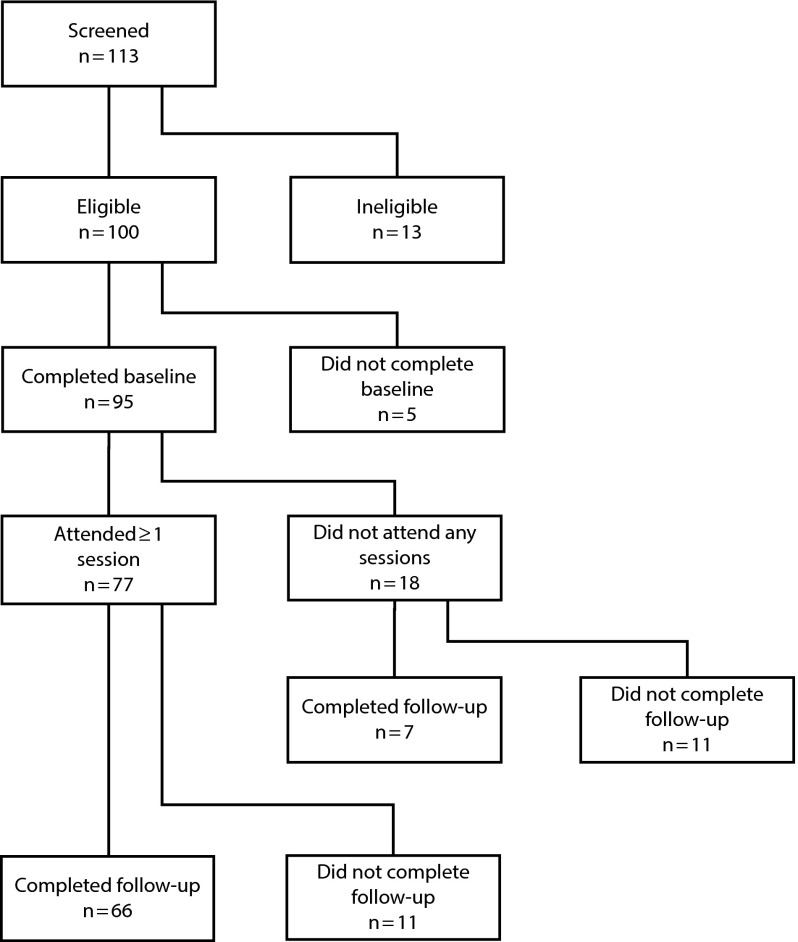

Figure 1 illustrates sample eligibility and retention. Of the 113 men screened, 100 met eligibility requirements. Of these, 66 attended 1 or more sessions and completed both baseline and follow-up assessments; we conducted our main analyses on these participants. Of the remaining 34, 5 did not complete baseline questionnaires, 18 did not attend any sessions, and 11 attended sessions but did not complete a follow-up assessment. The 66 men in the analysis sample were older (mean = 41.1 years; SD = 11.8) than the 34 excluded men (mean = 36.3; SD = 12.9; t = 1.88; df = 98; P = .06). They were also more likely to have had anal or vaginal intercourse with any partner type (93.7% vs 79.3%; χ2 = 4.2; df = 1; P = .04). With casual partners, they reported many more occasions of sexual intercourse (mean = 6.1 and 1.5, SD = 12.1 and 2.7, respectively; t = 2.87; df = 75; P < .01) and of unprotected sexual intercourse (mean = 3.3 and 0.4, SD = 9.8 and 1.4, respectively; t = 2.25; df = 67; P < .01). We found no differences between those included and excluded in the analyses on other demographic characteristics (education, race/ethnicity), methadone versus nonmethadone site, other sexual behavior outcomes, or condom skills and barriers outcomes.

FIGURE 1—

Participant flow chart for Real Men Are Safe–Culturally Adapted trial.

Table 1 shows descriptive information for participants in the original REMAS study and in REMAS-CA. Participants in both samples had a mean age of 41.1 years, with wide variability (range = 18–60 years and 18–64 years for REMAS-CA and REMAS, respectively). The majority in both samples had a high school education or less. Only a small number in the REMAS-CA sample were non-Hispanic Whites (n = 12; 18.2%).

TABLE 1—

Participant Characteristics: Real Men Are Safe–Culturally Adapted, April 2010—June 2011

| Characteristic | REMAS-CA (n = 66), Mean ±SD or No. (%) | REMAS (n = 136), Mean (SD) or No. (%) |

| Age, y | 41.1 ±11.8 | 41.1 ±11.1 |

| Education | ||

| < high school graduate | 28 (42.4) | 31 (22.8) |

| High school graduate | 24 (36.4) | 74 (54.4) |

| Some college | 12 (18.2) | 24 (17.6) |

| ≥ bachelor's degree | 2 (3.0) | 7 (5.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic White | 18 (27.3) | 20 (14.7) |

| African American | 28 (42.4) | 38 (27.9) |

| Non-Hispanic, other or biracial | 5 (7.6) | 5 (3.7) |

| Hispanic, other or biracial | 3 (4.5) | 0 (0) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 12 (18.2) | 73 (53.7) |

| Site type | ||

| Methadone | 33 (50) | 88 (64.7) |

| Nonmethadone | 33 (50) | 48 (35.3) |

Note. REMAS–CA = Real Men Are Safe–Culturally Adapted.

Comparison of Minority Men in 2 Studies

A larger percentage of minority REMAS-CA than minority REMAS participants completed 3 or more sessions (87.0% vs 75.2%). This difference in proportions was nonsignificant (χ2 = 2.24; df = 1; P = .13), with a relatively small effect size midway between small and medium (odds ratio = 2.10). Table 2 shows outcome scores for minority men from the REMAS and REMAS-CA studies. Effect sizes for sexual and protective behaviors suggested that REMAS participants were more likely than REMAS-CA participants to have any sexual intercourse with casual and regular partners at follow-up. However, they had fewer occasions of regular-partner sexual intercourse and more occasions of casual-partner intercourse. Unprotected intercourse occasions followed a similar pattern: REMAS participants had less unprotected intercourse with regular partners but more with casual partners. The largest difference in sexual behavior between studies was in casual-partner condom use: REMAS-CA participants had decreased likelihood of having casual-partner intercourse and greater likelihood of condom use when they did.

TABLE 2—

Change on Sexual Behavior and Cognitive Variables From Baseline to 3-Month Follow-Up Among Minority Participants in Real Men Are Safe and Its Cultural Adaptation: April 2010—June 2011

| REMAS-CA (n = 54) |

REMAS (n = 63) |

Change in REMAS vs REMAS-CA |

||||

| Baseline, % (No.) or Mean ±SD | Follow-Up, No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Baseline, No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Follow-Up, No. (%) or Mean ±SD | OR or RRa (95% CI), Difference in %, or B | P | |

| Had anal/vaginal sexual intercourse | ||||||

| Regular and casual partners | 96 | 83 | 97 | 94 | 2.77 (0.65, 11.80) | .17 |

| Regular partners | 72 | 61 | 71 | 75 | 2.28 (0.87, 5.96) | .09 |

| Casual partners | 40 | 27 | 41 | 43 | 1.98 (0.86, 4.59) | .11 |

| Ever used condomsb | ||||||

| Regular and casual partners | 47 (45) | 54 (41) | 37 (55) | 35 (49) | –9 | |

| Regular partners | 38 (37) | 40 (33) | 27 (41) | 24 (38) | –5 | |

| Casual partners | 61 (18) | 77 (13) | 52 (23) | 42 (24) | –26 | |

| High (80%) condom usec | 28 (18) | 69 (13) | 18 (23) | 25 (24) | –34 | |

| Sexual occasions, no. | ||||||

| All partners | 27.3 ±33.7 | 18.4 ±28.1 | 24.0 ±27.6 | 16.5 ±23.4 | 1.06 (0.69, 1.63) | .79 |

| Regular partners | 19.9 ±29.4 | 15.9 ±27.2 | 16.3 ±23.9 | 10.1 ±14.5 | 0.76 (0.48, 1.20) | .23 |

| Casual partners | 5.9 ±11.8 | 1.9 ±4.2 | 7.8 ±18.9 | 6.4 ±19.7 | 2.95 (1.01, 9.17) | .04 |

| Casual partnersc | 11.8 ±14.5 | 3.8 ±5.4 | 13.6 ±23.5 | 11.2 ±25.2 | 2.81 (0.81, 9.67) | .07 |

| Unprotected sexual occasions, no. | ||||||

| All partners | 19.9 ±30.2 | 16.0 ±27.5 | 20.4 ±26.6 | 13.7 ±20.9 | 0.94 (0.59, 1.51) | .81 |

| Regular partners | 15.2 ±25.3 | 14.4 ±26.0 | 15.0 ±23.9 | 8.9 ±13.8 | 0.64 (0.39, 1.07) | .09 |

| Casual partners | 3.0 ±8.6 | 0.8 ±3.2 | 5.4 ±14.7 | 4.8 ±16.1 | 4.94 (1.06, 23.09) | .02 |

| Casual partnersc | 6.2 ±11.6 | 1.6 ±4.4 | 9.4 ±18.6 | 8.4 ±20.7 | 4.56 (0.84, 24.73) | .04 |

| Condom use skills | ||||||

| Male condom | 4.3 ±1.9 | 5.3 ±1.6 | 3.9 ±1.4 | 5.7 ±1.2 | 0.22 | .01 |

| Female condom | 2.4 ±1.8 | 3.3 ±1.7 | 2.0 ±1.5 | 4.6 ±1.3 | 0.44 | .001 |

| Condom Barriers Scaled | ||||||

| Total | 3.4 ±0.7 | 3.6 ±0.6 | 3.4 ±0.7 | 3.5 ±0.7 | –0.05 | .49 |

| Partner barriers | 3.5 ±0.9 | 3.6 ±0.9 | 3.4 ±1.0 | 3.6 ±1.0 | –0.02 | .79 |

| Effects on sexual experience | 2.9 ±0.9 | 3.3 ±0.8 | 3.1 ±0.9 | 3.2 ±0.9 | –0.12 | .13 |

| Access/availability | 4.0 ±0.8 | 4.0 ±0.6 | 4.0 ±0.7 | 4.2 ±0.6 | 0.11 | .2 |

| Motivational barriers | 3.1 ±0.9 | 3.5 ±0.9 | 2.9 ±0.9 | 3.3 ±1.0 | –0.09 | .25 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; REMAS–CA = Real Men Are Safe–Culturally Adapted; RR = relative risk.

ORs apply to the “Had anal/vaginal sexual intercourse” categories, and RRs apply to the sexual occasions categories.

Among sexually active participants.

Among participants who reported sexual intercourse with casual partners at baseline or follow-up; REMAS-CA, n = 25; and REMAS, n = 36.

Higher scores = fewer perceived barriers.

Also shown in Table 2 are results for condom use skills and barriers. We observed statistically significant improvements (P < .05) for each of these outcomes when we combined the data from the REMAS-CA and REMAS studies (not shown), except for the partner barriers scale (P = .07). However, whether the participants in the 2 studies differed from each other in the amount of change varied by outcome. For male and female condom skills, change was smaller among REMAS-CA than REMAS participants (Table 2). This was partly attributable to the REMAS participants having lower scores at baseline but higher scores at follow-up. For male condoms, the difference was small (Cohen’s d = 0.22). Generally speaking, we observed no appreciable differences between study samples on the Condom Barriers Scale. The largest (although nonsignificant) between-study difference was in that scale's effects on the sexual experience scale, with REMAS participants showing less change (B = −0.12).

Focus Group Themes

Table 3 shows a summary of participant likes, dislikes, and suggested changes expressed during the postintervention focus groups. In general, participants expressed many positive and few negative opinions about REMAS-CA. Likes focused on obtaining new information and skills, experiencing camaraderie and comfort in the groups, and acquiring understanding of the effect on adult behavior of upbringing and personal experiences within a cultural context.

TABLE 3—

Feedback From Postintervention Focus Groups: Real Men Are Safe–Culturally Adapted, April 2010—June 2011

| Positive and Negative Aspects of REMAS-CA | Feedback |

| Participant likes | Getting basic information about STI statistics and safe sex options; some specifically liked myth cards exercise |

| Camaraderie of all-men’s group | |

| Condom practice and female condom information | |

| Group became a safe place to talk about sensitive issues | |

| Able to get in touch with positive values from childhood years | |

| Surprised at how similar values were across cultures/ethnicity | |

| TALK tools (communication skills) helpful, but take practice | |

| Started to think more about own sexual risk taking | |

| Focus on sexual intercourse under the influence led to positive discussions about risk triggers and ways to enhance intercourse without drugs | |

| Participant dislikesa | Unfamiliar language sometimes used |

| Movie clips outdated or did not add much to discussion (although some felt they were a good tool for exploring how they might behave in a similar situation) | |

| Some sessions had ≤ 3 attendees and quality of discussion suffered | |

| Participant suggestions for improvement | Provide TALK tool reminder cards to take home |

| Teach skills to increase comfort when talking with partners about safe sex and subsequent behaviors | |

| Teach how to make sexual intercourse better when dealing with sexual dysfunction without drugs | |

| Provide information on Viagra and natural remedies for sexual dysfunction | |

| Include more on women’s perspective about sexual issues; consider having a woman cotherapist or having women patients attend some groups (other participants disagreed, because presence of women would change what people might be willing to say/discuss in a group) |

Note. REMAS–CA = Real Men Are Safe–Culturally Adapted; STI = sexually transmitted disease; TALK = Tell my partner “I hear you,” Assert what I want in a positive way, List my reasons for wanting to be safe, Know our alternatives and my bottom line.

Or aspects felt to be not very helpful.

Dislikes included unfamiliar language at times, dated movie clips, and limited discussion when attendance was low. Participants said REMAS-CA could be improved with greater focus on how to discuss enhancing sexual intercourse with a partner, how to deal with sexual dysfunction, and women’s perspectives on sexual issues.

DISCUSSION

REMAS, an HIV risk reduction intervention with demonstrated efficacy, does not address cultural aspects of sexual behaviors and did not reduce risky sexual behaviors in African American as much as in White substance-abusing men in a randomized clinical trial in the CTN.6 We therefore assessed the acceptability of and participants' receptivity to REMAS-CA and compared the effectiveness in behavioral change among ethnic minorities of REMAS and REMAS-CA.

Better minority attendance rates in REMAS-CA than in REMAS suggest that REMAS-CA may be more appealing to minorities. REMAS-CA participants also indicated that the additional cultural content in REMAS-CA was appealing and led to useful discussions concerning how culture and life experiences influence adult sexual behavior. The finding that REMAS-CA was appealing across ethnic groups is especially important because many HIV risk reduction programs serve a diverse clientele and lack the resources to target an intervention solely to 1 ethnic group.

Our second question was the extent to which REMAS-CA would improve outcomes for ethnic minority participants. As hypothesized, ethnic minority REMAS-CA participants reported more behavioral change with their casual partners than did ethnic minority REMAS participants. REMAS-CA participants engaged in less sexual intercourse with casual partners and used condoms more than did minority REMAS participants during sexual intercourse with casual partners. By contrast to the ethnic minority response to REMAS, behavioral change among ethnic minority REMAS-CA participants (i.e., fewer unprotected intercourse occasions) was similar to the behavioral change observed in White REMAS participants in the CTN evaluation of REMAS.2

An important strength of REMAS-CA is that it was designed to be appropriate for any ethnic or cultural group. Instead of targeting a specific cultural group, the modules encourage all men to consider the influence of their own cultural background on sexual decision-making. An intervention such as REMAS-CA should be more feasible for clinics to implement because it defines culture broadly and thus can be used with men from all backgrounds. This could be an economical workaround to the problem of lacking resources to target interventions to specific ethnic groups. Moreover, the comments of the focus group participants supported this approach. They not only noted the similarities across ethnic groups, but also reported that listening to men from different cultural groups discuss the role of cultural factors in their decision-making increased their insight about their own lives. Although REMAS-CA was developed with African American and Hispanic men in mind, pilot test results showed that the cultural adaptation in fact produced an intervention that was culturally sensitive to—and thus flexible enough for—all men.

Several theoretical perspectives on reducing health disparities offer potential explanations for the differential effectiveness we observed, such as Wyatt’s sexual health model19 and DePue et al.’s cultural translation framework.20 Both perspectives suggest that adapting generic interventions to incorporate historical and social contextual factors related to sexual behaviors and including strategies to take advantage of key culture-bound protective factors may enhance intervention effectiveness among ethnic minorities. Moreover, the health disparities literature has proposed that a cultural adaptation of an intervention may be warranted when evidence suggests that the generic intervention has limited effectiveness with a target group.21 Our findings advance our theoretical perspectives about reducing risky sexual behaviors. They support Wyatt’s proposition that attending to the role of cultural factors in sexual decision-making will improve intervention effectiveness.19 Our findings also support recommendations by DePue et al. to translate generic interventions to fit the social context of the target group.20

Limitations

Although we conducted our study in a variety of settings and had few exclusion criteria, the limits on generalizability of the findings arising from participant factors such as self-referral to the study, age, type of substance abused, psychiatric and substance abuse diagnosis, and sexual history have not been explored. The counselors who participated in the program received 16 hours of special training in REMAS-CA, monthly consultative conference calls, and feedback on performance via intermittent review of audiotapes. It is not clear whether similar results would be obtained after less intensive training.

Accuracy is also a challenge in any study relying on self-report. We administered the Sexual Behavior Inventory by the audio computer-assisted self-interviewing method. Respondents have been shown to disclose more regarding participation in high-risk behaviors with this method than with in-person, face-to-face interviews.22,23 This method lessens the impact of possible social desirability distortions in self-reports of risk behaviors.

The sample size in this pilot study did not enable us to evaluate REMAS-CA efficacy as rigorously as in a full-scale clinical trial. Nevertheless, evaluating REMAS-CA in a smaller study seemed an appropriate interim step to ensure the intervention’s readiness for a larger clinical trial. The promising results suggest that such a trial is warranted.

Combining ethnic groups for the analyses posed another potential limitation. Previous research suggests that specific ethnocultural and socioeconomic factors may result in meaningful ethnic differences in risky sexual behaviors across and even within racial/ethnic groups.24 Nevertheless, we combined the ethnic groups in this analysis not only because of the sample size, but also because our aim is to develop an effective intervention for clinics serving a diverse clientele rather than a specific group.

Future Directions

Both our data analysis and focus group findings support REMAS-CA’s readiness for a larger-scale clinical trial, which we plan to conduct. Prior to initiating a larger trial we will incorporate suggestions from focus group participants for revisions to REMAS-CA. A larger sample will enable us to examine several issues that the pilot study could not feasibly address, such as the efficacy of REMAS-CA for specific ethnic groups, and mediators and moderators of the response to REMAS-CA. In addition, a larger clinical trial may yield a design capable of increasing the accuracy of self-report with state-of-the-art electronic equipment such as smart phones to prompt participants to report their sexual behaviors perhaps several times a week instead of asking them to recall their sexual behaviors over an extended period.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant RC1 DA028245).

We regret to report that Donald A. Calsyn died Feburary 3, 2013.

Human Participant Protection

Human subjects committee G of the University of Washington approved the study protocol, as did the institutional review board associated with each participating treatment program. Participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Racial/ethnic disparities in diagnoses of HIV/AIDS—33 States, 2001–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(9):189–193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calsyn DA, Hatch-Maillette M, Tross Set al. Motivational and skills training HIV/sexually transmitted infection sexual risk reduction groups for men. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37(2):138–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoptaw S, Tross S, Stephens M, Tai B, NIDA CTN HIV/AIDS Workgroup A snapshot of HIV/AIDS-related services in the clinical treatment providers for NIDA’s Clinical Trials Network. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66(suppl 1):S163 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown LS, Kritz SA, Goldsmith RJ, Robinson J, Alderson D, Rotrosen J. Health services for HIV/AIDS, HCV, and sexually transmitted infections in substance abuse treatment programs. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(4):441–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calsyn DA, Crits-Cristoph P, Hatch-Maillette Met al. Reducing sex under the influence of drugs or alcohol for patients in substance abuse treatment. Addiction. 2010;105(1):100–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calsyn DA, Burlew AK, Hatch-Maillette MA, Wilson J, Beadnell B, Wright L. Real Men Are Safe–Culturally Adapted: utilizing the Delphi process to revise Real Men Are Safe for an ethnically diverse group of men in substance abuse treatment. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(2):117–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernal G, Scharrón-del-Rio MR. Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2001;7(4):328–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall GCN. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):502–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambless DL, Crits-Cristoph P. Evidence-based practices in mental health: debate and dialogue on the fundamental questions. In: Norcross JC, Beutler LE, Levant RF, eds. The Treatment Method. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006:191–199 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crepaz N, Horn AK, Rama SMet al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk sex behaviors and incident sexually transmitted disease in Black and Hispanic sexually transmitted disease clinic patients in the United States: a meta-analytic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(6):319–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles Cet al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1177–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semaan S, Des Jarlais DC, Sogolow Eet al. A meta-analysis of the effect of HIV prevention interventions on the sex behaviors of drug users in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(suppl 1):S73–S93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prendergast ML, Urada D, Podus D. Meta-analysis of HIV risk-reduction interventions within drug abuse treatment programs. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):389–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual level change in HIV risk behavior. In: Peterson JL, DiClemente CC, eds. Handbook of HIV Prevention. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press; 2000:3–55 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petry NM. Reliability of drug users’ self reported HIV risk behaviors using a brief, 11-item scale. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36(12):1731–1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calsyn DA, Hatch-Maillette MA, Doyle SR, Cousins S, Chen T, Godinez M. Teaching condom use skills: practice is superior to observation. Subst Abus. 2010;31(4):231–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyle SR, Calsyn DA, Ball SA. Factor structure of the Condoms Barriers Scale with a sample of men at high risk for HIV. Assessment. 2009;16(1):3–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyatt GE. Enhancing cultural and contextual intervention strategies to reduce HIV/AIDS among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):1941–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DePue JD, Rosen RK, Batts-Turner Met al. Cultural translation of interventions: diabetes care in American Samoa. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2085–2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrera M, Jr, Castro FG. A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2006;13(4):311–316 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metzger DS, Koblin B, Turner Cet al. Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study Protocol Team. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(2):99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross M, Holte SE, Marmor M, Mwatha A, Koblin BA, Mayer KM. Anal sex among HIV-seronegative women at high risk of HIV exposure. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24(4):393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sasaki PY, Kameoka VA. Ethnic variations in prevalence of high-risk sexual behaviors among Asian and Pacific Islander adolescents in Hawaii. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1886–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]