Abstract

Stigma against mental illness is a complex construct with affective, cognitive, and behavioral components. Beyond its symbolic value, federal law can only directly address one component of stigma: discrimination.

This article reviews three landmark antidiscrimination laws that expanded protections over time for individuals with mental illness. Despite these legislative advances, protections are still not uniform for all subpopulations with mental illness. Furthermore, multiple components of stigma (e.g., prejudice) are beyond the reach of legislation, as demonstrated by the phenomenon of label avoidance; individuals may not seek protection from discrimination because of fear of the stigma that may ensue after disclosing their mental illness.

To yield the greatest improvements, antidiscrimination laws must be coupled with antistigma programs that directly address other components of stigma.

INDIVIDUALS WITH MENTAL illness experience disparities in health care, education, and employment outcomes, and the stigma associated with mental illness is a central contributing factor to these disparities.1–6 Stigma is a complex construct with four social-cognitive processes (i.e., cues, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination) that may be directed by others toward those with mental illness (i.e., public stigma) and may occur within an individual with mental illness (i.e., self-stigma). To examine the role of federal policy in improving disparities resulting from the stigma process, we first provide a brief overview of stigma and highlight how federal legislation only directly addresses one of its components—discrimination resulting from public stigma. Next, we provide an overview of three landmark antidiscrimination laws in health care (Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act [MHPAEA]7 of 2008), education (Education for All Handicapped Children Act [EAHCA]8 of 1975), and employment (Americans with Disabilities Act [ADA]9 of 1990) and highlight three common features they share (1) expanded protections over time for persons with mental illness, (2) differential protections for subgroups with mental illness, and (3) implementation challenges resulting from label avoidance that undermine the ability of these laws to yield better outcomes. Finally, we highlight how antidiscrimination legislation must be complemented by approaches that directly target other components of the stigma process (e.g., prejudice) to yield the greatest improvement in outcomes for this population.

STIGMA COMPONENT TARGETED BY FEDERAL LEGISLATION

According to Corrigan,2 stigma comprises four social-cognitive processes—cues, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination—that can manifest as public stigma and self-stigma; the former comprises stigma processes that occur in the social environment toward those with mental illness, whereas the latter comprises stigma processes that occur within an individual with mental illness. First, cues such as psychiatric symptoms, social-skills deficits, physical appearance, and labels (e.g. clinical diagnoses) may suggest a person has mental illness. Cues may trigger cognitive associations with stereotypes that are negative (i.e., knowledge structures about a marked group) related to mental illness. Commonly held stereotypes against those with mental illness include incompetence and a perception that these individuals are more likely to engage in violence and other criminal behavior.10–12 People (either outsiders or those with mental illness) can believe in these known stereotypes or reject them; if they endorse the stereotypes, they develop prejudice against those with mental illness—a cognitive and affective response. Discrimination is the behavioral manifestation of prejudice that occurs when those with or those believed to have mental illness are differentially treated; discrimination can occur by others toward those with mental illness, or within an individual with mental illness (i.e. self-discrimination).

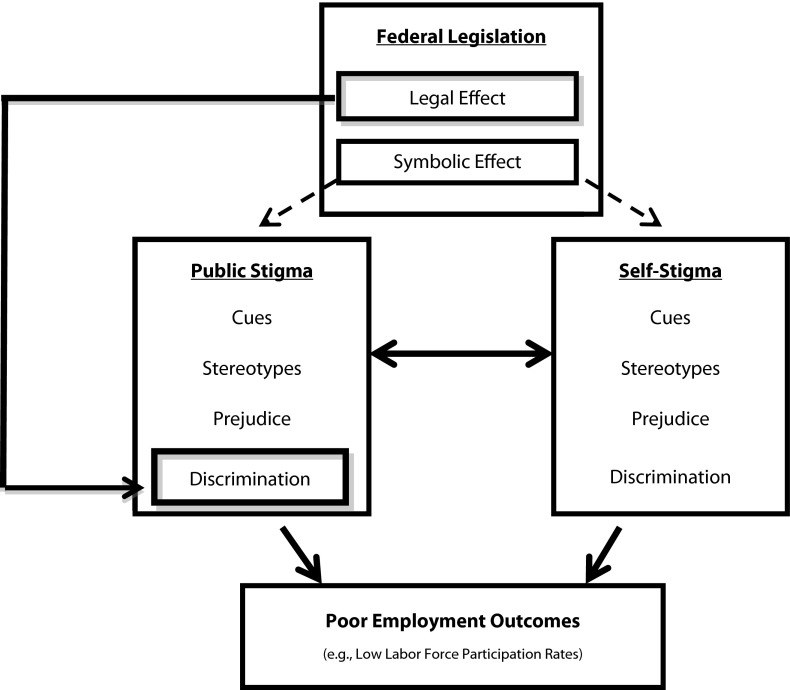

Low labor force participation among those with mental illness provides an illustrative example of how multiple elements of the stigma process contribute to poor outcomes for this population (Figure 1). For example, stigma might lead to low labor force participation if employers discriminate during the hiring process (i.e., discrimination resulting from public stigma), if individuals with mental illness do not apply for a job because they believe they are incompetent (i.e., self-discrimination resulting from self-prejudice), or if individuals with mental illness do not apply because they expect to be stereotyped and rejected by the employer (i.e., self-discrimination resulting from fear of public stigma).2,13 Although federal policies can neither legislate changes in beliefs and attitudes about mental illness nor directly prevent self-discriminatory behaviors, they can directly address discriminatory behaviors by others (e.g., employers) toward those with mental illness (Figure 1).14,15 Moreover, these laws also hold tremendous symbolic value and the potential to indirectly improve other components of public and self-stigma (e.g., stereotypes and prejudice) by affirming that those with mental illness should not face discrimination.15 For these reasons, antidiscrimination legislation comprises an important federal policy mechanism to address poor health care, education, and employment outcomes among those with mental illness resulting from the stigma process.

FIGURE 1—

Role of federal legislation in improving poor employment outcomes resulting from mental health stigma.

LANDMARK LEGISLATION FOR MENTAL ILLNESS DISCRIMINATION

Three landmark laws address discrimination against those with mental illness within the domains of health care, education, and employment. Supporters framed the importance of each law as a civil rights issue before enactment, and the passage of each law was hailed as a civil rights victory with important symbolism for the affected populations. Following enactment, the evolution and implementation of these laws have shared several other common features. First, legislative protections afforded to those with mental illness have been clarified and expanded over time in all three domains. Second, despite these expansions, protections offered to those with mental illness are not uniform for all subgroups with specific types of mental illness. Finally, the effectiveness of each piece of legislation is undermined by label avoidance, in that some individuals do not seek protection under these laws out of fear of becoming publically identified as having mental illness, and consequently, becoming a target of stigma.

Expanded Protections Over Time

Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008.

Health insurance coverage for mental health and substance use disorder treatment has historically been less generous than coverage for medical care,16 and advocates have long contended that these differences in insurance coverage constitute discrimination.17 The Mental Health Parity Act (MHPA)18 of 1996 was the first federal law that addressed parity between mental health and medical services. Yet, it was extremely limited in the protections it offered because it only required parity for annual and lifetime dollar limits in large private group health plans (i.e., plans with at least 50 employees) that already offered mental health benefits. This law was supplanted by the more comprehensive, landmark MHPAEA of 2008,7 which required large private group health plans (i.e., plans with at least 50 employees) that offer mental health or substance use disorder insurance coverage to offer these benefits at parity with medical or surgical benefits in annual and lifetime dollar limits, financial requirements (e.g., deductibles, copayments, coinsurance), and treatment limitations (e.g., number of visits and days of coverage). Although the MHPAEA is still limited in that it only applies to large group health plans and does not require these plans to offer any mental health or substance use disorder coverage, the law provided a foundation for further expansion of mental health and substance use disorder parity by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010. The PPACA contains provisions requiring mental health and substance use disorder coverage to be included in essential benefits packages for insurance plans offered in the state health insurance exchanges and in Medicaid plans serving enrollees who are moving into the program through expanded eligibility criteria. Furthermore, the PPACA requires mental health and substance use disorder coverage offered in these plans to either partially comply (in the case of plans serving new Medicaid enrollees) or fully comply (in the case of state health insurance exchange plans) with existing federal parity regulations established by the MHPAEA.19,20

Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975.

Legislation addressing discrimination against those with disabilities in school settings offers protections to students with mental health–related disabilities. Before the passage of the EAHCA of 1975,8 Congress found that four million children with disabilities were either excluded from public school services or served inappropriately.21 The EAHCA of 1975 granted federal funding for states that provide a “free appropriate public education” for disabled students, including students classified as having a severe emotional disturbance. For students who qualified, the legislation required schools to provide education alongside nondisabled peers to the maximum extent appropriate (i.e., in the least restrictive environment possible), an individualized education program, and any “related services” (e.g., physical therapy and psychological counseling) necessary for the student to benefit from special education.22,23

In 1990, the EAHCA of 1975 was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA), and it has been amended multiple times since then with a trend toward increased protections for children with mental health–related disabilities.21 For example, coverage has been extended to children of younger ages (e.g., toddlers and preschoolers), and to children with types of mental health disorders other than SED; these include autism, traumatic brain injury, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The IDEA of 1990 also expanded the definition of “related services” that schools must provide for eligible students by including social work services and rehabilitative counseling.21

Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990.

Legislation addressing workplace discrimination against those with disabilities also provides protection for those with psychiatric disabilities just as the EAHCA does for school-based discrimination. Title 1 of the ADA of 19909 prohibits employers with at least 15 employees from discriminating against disabled persons in job application procedures, hiring, advancement, discharge, compensation, and other employment-related conditions. The statute defines a disability as a mental or physical impairment that substantially limits one or more “major life activities.” Furthermore, it requires covered entities to make “reasonable accommodations” to persons with disabilities (i.e., changes to the workplace to allow a person to perform their job), unless these accommodations impose “undue hardship” on the employer (i.e., accommodation is too expensive or disruptive for the business).

In 1997, the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) released enforcement guidelines to clarify how the ADA applies to psychiatric disabilities. These guidelines included a description of what constitutes “mental impairment,” examples of major life activities that may be affected by mental impairment, and examples of reasonable accommodations that can be provided to persons with psychiatric disabilities.24 However, ambiguities in these guidelines remained, and researchers documented continued challenges faced by those with psychiatric disabilities when seeking protection under the ADA.25,26 For example, claimants had difficulty convincing courts that cognitive processes, such as concentrating and thinking, constituted major life activities.25 Additionally, the Supreme Court ruled that workers cannot be classified as disabled if their condition is controlled by mitigating measures (e.g., medication),27,28 which directly affected workers with mental illness whose symptoms were controlled by psychotropic medications. The ADA Amendments Act of 200829 sought to clarify these issues by including an expanded list of major life activities that could be affected by disability and a provision that mitigating measures (e.g., medications) should not be considered when assessing whether someone has a disability, thereby overriding the Supreme Court rulings.

Protections Not Uniform for All Subgroups

Although antidiscrimination protections for those with mental illness have become more expansive over time, these protections are not uniform for all subgroups with different types of mental illness because of (1) explicit language about inclusion and exclusion criteria in the statute or implementation rules, (2) vague statutory language that yields variation in the interpretation about which groups qualify for protection, and (3) incentives created by the legislation that affect specific groups differently. The ADA provides an example of how explicit language in the statute yields differential protection for subgroups with mental health or substance use disorders. Although the EEOC guidelines allow individuals with most diagnoses recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition30 to seek protection under the ADA, some diagnoses are explicitly excluded, such as abuse of or dependence on illicit drugs.24

The MHPAEA and the EAHCA both contain statutory language that is open to interpretation as to which groups qualify for protection. For example, the MHPAEA allows insurers to determine which mental health or substance use disorder diagnoses are covered by the health insurance plan. Because this discretion could result in the systematic exclusion of specific diagnoses from health insurance plans, the MHPAEA also requires the Government Accounting Office to monitor trends in mental health and substance use disorder insurance coverage and whether systematic exclusions have occurred. When considering the EAHCA, researchers have noted that there is enormous variation in the interpretation of the severe emotional disturbance criteria across school districts and states.31 Children may qualify for special education services if they meet one or more of five inclusion criteria for severe emotional disturbance laid out in the legislation, such as an inability to learn that cannot be explained by intellectual, sensory, or health factors32; however, the legislation also excludes children who are classified as socially maladjusted, unless they also have an emotional disturbance. Social maladjustment, however, has never been defined in federal guidelines, and the lack of a definition has led to confusion and controversy.33 In some school districts, the social maladjustment clause has been interpreted in a manner that excludes youths from special education services if they have conduct disorder or oppositional defiance disorder.31

Finally, the ADA provides an example of how incentives created by legislation could potentially exacerbate discrimination for some populations with mental illness. Although the ADA prohibits employers from asking about mental illness during the job application process, some employers could attempt to screen out (by using cues such as affect, communication skills, or gaps in work history) those with mental illness because of what must be offered to disabled applicants once they are hired.34 Therefore, the ADA could be more likely to protect to those with less severe types of mental illness who already have a job or who are able to hide their mental illness when applying for a job. This phenomenon also illustrates how stigmatizers may become more careful and perpetuate discriminatory behavior even if antidiscrimination laws have been implemented.

Effectiveness Undermined by Label Avoidance

Each of the previously described laws is limited in its ability to improve disparities resulting from stigma because there are multiple components of the stigma process that are beyond the reach of federal legislation. As an example, label avoidance undermines the effectiveness of antidiscrimination laws because individuals with mental illness might not seek protection from discrimination out of fear of becoming more publically identified as having mental illness and the stigma that may ensue. In health care, research indicates that fear of receiving an official psychiatric diagnosis is a major barrier to seeking help for mental health and substance use disorder treatment.2 Thus, providing insurance parity through the MHPAEA cannot compensate for those who avoid treatment, regardless of whether they have insurance coverage. Similarly, antidiscrimination legislation in education and employment settings cannot protect disabled children whose parents are resistant to having their child labeled with a psychiatric disability, or job applicants and employees who are reluctant to disclose their mental health status to an employer.6,34

Although the extent to which label avoidance occurs is difficult to ascertain, there is reason to believe its impact is of consequence. The MHPAEA took effect for most insurance plans in January 2010 and has not yet been systematically evaluated; however, studies evaluating the implementation of mental health and substance use disorder parity in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program found that parity had little effect on overall mental health or substance use disorder treatment rates and overall spending.35,36 Although this outcome could be caused by several factors, label avoidance provided one possible explanation for why more individuals did not seek services despite having received more generous mental health or substance use disorder insurance coverage. Similarly, data suggested that children with severe emotional disturbance might be underidentified and underserved in special education programs. Approximately one percent of school-age children were identified with severe emotional disturbance for the purposes of receiving special education services, although national estimates of severe emotional disturbance were at least five times higher.4,6,37 Finally, researchers have noted that employment-related outcomes remain suboptimal for those with mental illness as evidenced by the low rate of labor force participation of this population resulting from underemployment, unemployment, or being out of the labor force.26

Although label avoidance might limit the number who seek protection from discrimination, these laws provide a foundation to improve adverse outcomes resulting from the stigma process by offering protection against discrimination that would not otherwise be afforded. These laws might also symbolically help reduce stigma in their shared assertion that those with mental illness should not face discrimination. However, to yield the greatest improvements in outcomes for those with mental illness, antidiscrimination laws must be complemented by other approaches that directly target other components of the stigma process—including stereotypes, prejudice, and self-discriminatory behavior.38,39

As an example, antistigma programs that target attitudes and behavioral intentions toward those with mental illness directly address components of public stigma that are beyond the reach of legislation. The literature concerning these programs is vast and described more in depth elsewhere.40–42 Briefly, however, these programs target the cognitive and affective components of public stigma by implementing one of three strategies at a population level or in specific environments (e.g., employment settings): (1) education that challenges inaccurate stereotypes, (2) increasing interpersonal contact with individuals who have mental illness, and (3) presentation of stigmatizing behavior as a moral injustice.43,44 Notably, a recent meta-analysis found that antistigma programs implementing education or contact strategies significantly improved stigmatizing attitudes and behavioral intentions toward those with mental illness.40 This study provided promising evidence that these programs could complement antidiscrimination legislation when seeking to reduce stigma against mental illness.

CONCLUSIONS

Extant federal laws directly address one component of the complex stigma process—discrimination resulting from public stigma—and provide an important foundation to improve disparities in health care, education, and employment outcomes for those with mental illness that result from the stigma process. The protections offered by these laws against discriminatory behavior have expanded over time, and they may indirectly improve other stigma components (e.g., prejudice) through their symbolic value. However, these protections are not uniform for all subgroups with mental illness, and future research is needed to assess the differential consequences of each law across subpopulations. Furthermore, there are multiple components of the stigma process that are beyond the reach of federal legislation, and individuals may not seek protection from discrimination out of fear of stigma that may ensue once they become identified as having a mental illness. Bolstering these laws with programs that directly target other components of the stigma process (e.g., stereotypes and prejudice) has the potential to improve health care, education, and employment outcomes for this population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant 1K01MH09582301).

We are grateful for the helpful comments and suggestions by Neetu Chawla, Sarah Blake, Lindsay Allen, and three anonymous reviewers.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not required because human participants were not used in this study.

References

- 1.Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A. Discrimination in health care against people with mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):113–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuart H. Mental illness and employment discrimination. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(5):522–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services 30th Annual Report to Congress on Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC: US Department of Education; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner M, Kutash K, Duchnowski AJ, Epstein MH, Sumi WC. The children and youth we serve: a national picture of the characteristics of students with emotional disturbances receiving special education. J Emot Behav Disord. 2005;13(2):79–96 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kauffman JM, Mock DR, Simpson RL. Problems related to underservice of students with behavioral disorders. Behav Disord. 2007;33(1):43–57 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. Pub L No. 110–343 (2008)

- 8. Education for All Handicapped Children Act. Pub L No. 94–142 (1975)

- 9. American With Disabilities Act. Pub L No. 101–336 (1990)

- 10.Phelan JC, Link BG, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness in 1950 and 1996: what is mental illness and is it to be feared? J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(2):188–207 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):467–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parcesepe AM, Cabassa LJ. Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: a systematic literature review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012; Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinel EC. Stigma consciousness: the psychological legacy of social stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(1):114–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burris S. Stigma and the law. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):529–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burris S. Disease stigma in U.S. public health law. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30(2):179–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barry CL, Huskamp HA, Goldman HH. A political history of federal mental health and addiction insurance parity. Milbank Q. 2010;88(3):404–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC. Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(3):481–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mental Health Parity Act. Pub L No. 104–204 (1996)

- 19.Garfield RL, Lave JR, Donohue JM. Health reform and the scope of benefits for mental health and substance use disorder services. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(11):1081–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarata AK. Mental Health Parity and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmaffy T. Evolution of the federal role. In: Finn CE, Jr, Rotherham AJ, Hokanson CR, Jr, eds. Rethinking Special Education for a New Century. Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Foundation and the Progressive Policy Institute; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treppa MS. The education for all handicapped children act: trends and problems with the “related services” provision. Gold Gate Univ Law Rev. 2010;18(2):427–442 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yell ML, Rogers D, Rogers EL. The legal history of special education - what a long, strange trip it’s been! Remedial Spec Educ. 1998;19(4):219–228 [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission EEOC Enforcement Guidance on the Americans with Disabilities Act and Psychiatric Disabilities. Washington, DC: US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission; 1997. Available at: http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/psych.html. Accessed September 1, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paetzold RL. Law and psychiatry: mental illness and reasonable accommodations at work: definition of a mental disability under the ADA. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(10):1188–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook JA. Employment barriers for persons with psychiatric disabilities: update of a report for the President’s Commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1391–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sutton v United Air Lines, 527 U.S. 471 (1999)

- 28. Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Kentucky Inc. v Williams, 000 U.S. 00–1089 (2002) [PubMed]

- 29. American With Disabilities Amendments Act. Pub L No. 110–325 (2008)

- 30.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC; American Psychiatric Association; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olympia D, Farley M, Christiansen E, Pettersson H, Jenson W, Clark E. Social maladjustment and students with behaviroal and emotional disorders: revisiting basic assumptions and assessment issues. Psychol Sch. 2004;41(8):835–847 [Google Scholar]

- 32. 34 Code of Federal Regulations §300.8.

- 33.Merrell KW, Walker HM. Deconstructing a definition: social maladjustment versus emotional disturbance and moving the EBD field forward. Psychol Sch. 2004;41(8):899–910 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mechanic D. Cultural and organizational aspects of application of the Americans with Disabilities Act to persons with psychiatric disabilities. Milbank Q. 1998;76(1):5–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldman HH, Frank RG, Burnam MAet al. Behavioral health insurance parity for federal employees. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1378–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azrin ST, Huskamp HA, Azzone Vet al. Impact of full mental health and substance abuse parity for children in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):e452–e459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A. 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(10):972–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corrigan PW, Shapiro JR. Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(8):907–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corrigan PW. Impact of consumer-operated services on empowerment and recovery of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1493–1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rusch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(10):963–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szeto ACH, Dobson KS. Reducing the stigma of mental disorders at work: a review of current workplace anti-stigma intervention programs. Appl Prev Psychol. 2010;14(1–4):41–56 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rüsch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW. Mental illness stigma: concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(8):529–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corrigan P, Gelb B. Three programs that use mass approaches to challenge the stigma of mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):393–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaebel W, Zaske H, Baumann AEet al. Evaluation of the German WPA “program against stigma and discrimination because of schizophrenia–Open the Doors”: results from representative telephone surveys before and after three years of antistigma interventions. Schizophr Res. 2008;98(1-3):184–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]