Abstract

Bone repair is a complicated process that includes many types of cells, signaling molecules, and growth factors. Fracture healing involves a temporally and spatially regulated biologic process that involves recruitment of stem cells to the injury site, tissue specific differentiation, angiogenesis, and remodeling. In light of its proximity to bone and abundant vascularity, muscle is an important potential source of cells and signals for bone healing. More complete understanding of the role of muscle in bone formation and repair will provide new therapeutic approaches to enhance fracture healing. Recent studies establish that muscle-derived stem cells are able to differentiate into cartilage and bone and can directly participate in fracture healing. The role of muscle-derived stem cells is particularly important in fractures associated with more severe injury to the periosteum. Sarcopenia is a serious consequence of aging, and studies show a strong association between bone mass and lean muscle mass. Muscle anabolic agents may improve function and reduce the incidence of fracture with aging.

Keywords: muscle, bone repair, osteoprogenitors, muscle derived stem cells, fracture, periosteum

Introduction

Bone regeneration is critical for the maintenance of mobility since injury to the skeleton occurs in the majority of people at some point during their lives. Additionally, many current treatments for degenerative diseases of the musculoskeletal system, including spine fusions and total joint arthroplasty, require regeneration of bone tissue. Although scar is a common aspect of the healing of many tissues, the unique mechanical properties of bone make it essential that the process of bone formation is faithfully completed for the reconstitution of skeletal integrity. The incidence of fractures in increasing worldwide due to increasing urbanization of the population, increased numbers of motor vehicles, and aging of the population. Approximate 4.1% of the UK population has a bone fracture each year (1). By middle age 50% of men in the UK population have experienced a bone fracture. By age 75, 40% of the women in the UK experience a fracture (1). In the French population the lifetime risk of sustaining a hip fracture in the population over 50 years of age in 10% for men and 30% for women (2). A recent examination of childhood cancer survivors and siblings in the United States estimated that 40% of the U.S. population sustains one or more fractures during their lifetimes (3).

While most bone fractures heal, approximately 10–15% have delayed union or non-union. Impaired healing is associated with aging, certain diseases (diabetes, obesity), environmental factors (smoking), and yet to be defined genetic factors (4–6). Local factors are also critically important. Fracture healing is more often compromised at skeletal sites with a reduced soft tissue envelope (7, 8). Increasing severity of injury to the surrounding muscle and soft tissues is highly associated with the development of non-union (8, 9). Given the clear importance of the soft tissue envelope, it is essential that improved understanding of the role of muscle tissues in skeletal regeneration be gained.

The process of fracture healing

Fracture healing depends upon a highly coordinated series of molecular, cellular and tissue events (10). In addition to injury to the skeleton, the energy transfer that results in bone fracture also involves injury to surrounding muscle, tendon, vascular structures, nerves and other soft tissues. The initial events involve formation of a hematoma and local inflammation. An early and essential aspect is the recruitment, proliferation, and accumulation of stem cells with development of a soft callus (11, 12). During the hard callus phase of fracture healing the tissues become vascularized with calcification of cartilage and ossification of newly formed bone. The final phase of fracture healing involves remodeling. In fracture healing the rapidly formed fracture callus and bone that restores skeletal integrity is disorganized (10). During the remodeling process, the disorganized bone is removed and replaced by mature lamellar bone.

Fracture healing occurs through both endochondral ossification and intramembranous ossification (11). In endochondral ossification, stem cells undergo chondrogenesis and form a cartilage intermediate. Chondrocytes in the cartilage callus differentiate into mature, calcified cartilage that acts as a template for bone formation and stimulates angiogenesis. In intramembranous ossification, osteoblasts differentiate directly from stem cell precursors and bone forms primarily in the absence of a cartilage template (11). While occurring simultaneously in fracture healing, intramembranous ossification localizes along the periosteal surface adjacent to the fracture site in areas with less vascular compromise (12). In contrast endochondral ossification occurs directly over the fracture site where blood supply is most compromised and where hypoxia is maximal (11). In bones that are rigidly fixed with plates and screws, fractures heal primarily through intramembranous ossification and have an overall reduction in fracture callus volume (13).

Molecular, cellular and tissue events in fracture healing

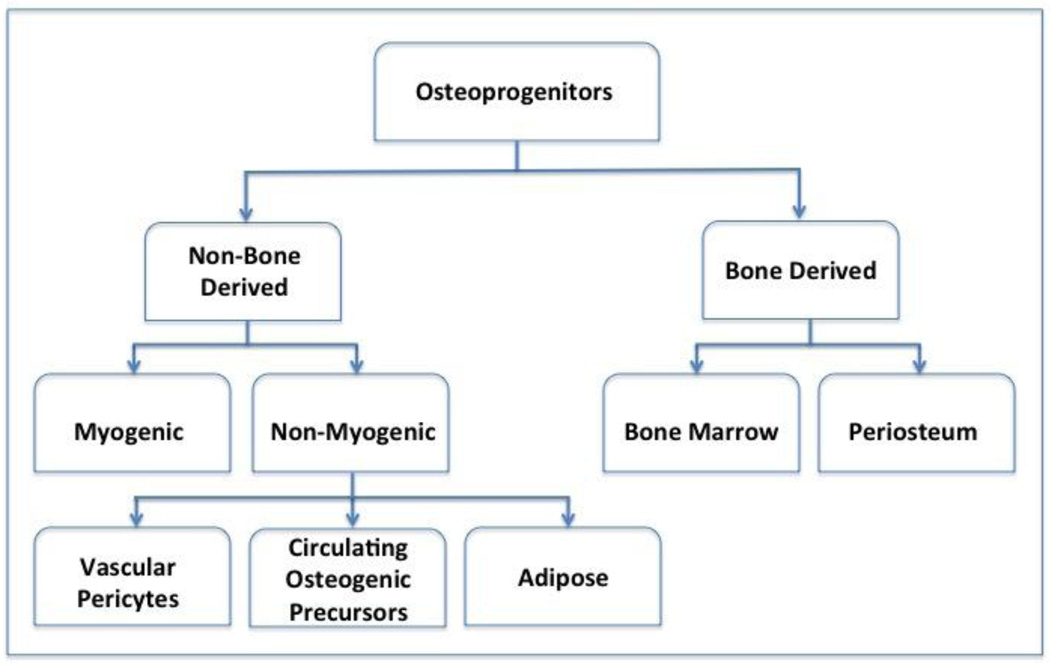

The primary event in the process of bone repair involves stem cell recruitment, proliferation, expansion and accumulation at the fracture site (11, 12). Given the importance of these initial events, an active area of ongoing research involves defining the sources of stem cells, their relative contributions, and the signals regulating their expansion and differentiation in fracture healing (11). Potential sources of stem cell progenitors include bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs), periosteum-derived stem cells (PDSCs), systemic circulation-derived stem cells (CDSCs), Vascular endothelium-derived pericytes (VEDPs), and muscle-derived stem cells (MDSCs), (Figure 1) (14–19).

Figure 1. Populations of stem cells involved in fracture repair.

Osteoprogenitor cells are derived from both skeletal and non-skeletal sites. Periosteum is a major source of cells in bone repair. Secondary bone remodeling requires angiogenesis and involves the participation of vascular-derived stem cell populations (pericytes). Muscle-derived stem cells have an increased role in the setting of extensive soft tissue damage.

While evidence suggests that stem cells from all of these sources contribute to repair, periosteal tissues appear to be the primary source of cells (11, 19). Injury to the periosteum results in non-union in pre-clinical models of fracture healing. Furthermore, cell lineage tracing studies demonstrate an essential role for PDSCs, or bone lining cells in the initial accumulation of the precursor cell pool necessary to initiate the healing response (14, 19). The periosteum has two anatomic layers, the cambium layer and the fibrous layer (12, 20). The cambium layer is directly opposed to the bone and is a rich repository of mesenchymal progenitor cells (12, 20). Cells in the cambium layer undergo both chondrocyte and osteoblast differentiation (14). Children have a thick periosteum with an enriched population of mesenchymal stem cells (12). Children rarely have fracture non-union, even in cases of severe soft tissue injury (21).

Bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) appear to have a lesser role in the development of the external callus tissue, but are likely involved in the endosteal repair process (22). Systemic-derived stem cells (SDSCs) are recruited to sites of injury but represent a relatively small population of cells (23). SDSCs likely influence bone repair by secretion of paracrine factors, rather than by direct contribution of cells to the tissue healing response (23). Vascular endothelium-derived progenitors (VEDPs) are likely highly involved in the more organized bone formation that secondarily occurs during the remodeling process (24). While less is known about the direct role of muscle-derived stem cells (MDSCs) in bone repair, recent advances provide additional insight.

Muscle as a component of fracture healing

Adults with extensive soft tissue injury have reduced healing potential. While this could be secondary to increased periosteal injury, it is clear that muscle tissues themselves have a role in promoting healing. A recent study reviewed 16 prior publications involving tibia fractures and found that the delayed/non-union rate was 55% in patients that had an associated compartment syndrome in contrast to an 18% rate in tibia fractures without compartment syndrome (25).

Muscle influences fracture healing by promoting revascularization, by providing a source of osteogenic growth factors, and as a potential source of stem cells (26). A rat model of open tibia fracture healing used a Polytetra-fluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane to selectively block contact with either muscle tissues or fasciocutaneous tissues at the bone fracture site. Selectively blocking the fasciocutaneous tissues that are located in the anterior aspect of the leg resulted in essentially normal fracture healing. However, when the PTFE membrane barrier prevented contact of bone with adjacent muscle tissues located in the posterior aspect of the leg, fracture healing was markedly compromised (27). A recent publication showed that short-term atrophy of the quadriceps muscle secondary to botulinum toxin A toxin results in impaired healing of femur fractures in rats (28). In patients with fractures and severe soft tissue injury, muscle flaps have prevented serious infections and reduced non-union, and have made limb salvage possible in many cases (29–31).

Muscle as a source of stem cells for bone healing

Clinical observations have demonstrated the potential of muscle tissue to participate directly in bone formation. Soft tissue Injury sometimes results in ectopic bone formation within muscle (17, 32). During ectopic ossification stem cells in muscle proliferate and differentiate into cartilage and bone cells (15). The bone formation results in angiogenesis, bone remodeling, and the formation of marrow elements within the ectopic bone. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva is a rare disorder in which mild trauma leads to progressive ectopic bone formation in muscle (33). Genetic approaches have defined an activating mutation of the BMP-receptor (ALK2; activin type I receptor) as the somatic gene mutation responsible for this condition (33). One of the characteristic features of the BMP proteins that aided in their early discovery and identification is their ability to induce bone formation in muscle tissue (34). Thus, cells in muscle clearly have the potential to undergo differentiation into bone cells under the appropriate conditions and signals.

While study of lineage tracing of muscle derived stem cells is limited, available data suggest that MDSC populations are not typically involved in the bone repair except in the setting of extensive injury to the periosteum where they may become an important, or possibly a primary source of progenitor cells. A recent study in mice used an elegant cell lineage tracing approach to define the participation of muscle cells in healing fracture callus (16). The MyoD-Cre+; Z/AP+ reporter identifies muscle cells. In the absence of Cre-recombinase the Z/AP+ reporter constitutively expresses the LacZ transgene; upon exposure to Cre, the transgene recombines to express human placental alkaline phosphatase. Using the MyoD-Cre recombination, muscle cells in vivo can be lineage-traced by their expression of placental alkaline phosphatase. In closed tibia fractures there was negligible contribution of muscle cells to the healing callus tissues (16). Similarly, MyoD expressing cells were also absent in the new bone formed in a cortical defect in the tibia (16). In contrast, in mice with open fractures with periosteal stripping and muscle injury, muscle precursor cells were abundant in the callus tissues. Human alkaline phosphatase expressing cells were observed embedded in both bone and cartilage matrix (16). Muscle derived cells were approximately 35–40% of the cells in fracture callus at 3 weeks and approximately 15–20% of the cells at 3 weeks (16).

A related study further demonstrated that the muscle derived cells present in fracture callus shifted gene expression from the muscle marker Pax3 to the chondrogenic markers, Sox9 and Nkx3.2 (35). Furthermore, while muscle satellite cells in cell culture normally express the muscle marker Pax3, when placed in chondrogenic medium with either TGF-beta or BMP-2, Pax3 expression is inhibited and the cells instead express the chondrogenic genes Sox9 and Nkx3.2 (35). These lineage tracing studies provide further evidence that while periosteum and bone associated cells are the primary source of stem cells in fracture healing, in instances in which the periosteum is compromised, muscle stem cells express chondrocyte and osteoblast markers and become an important component of fracture callus tissue (16, 35).

It has recently been established that signals generated from injured bone act as paracrine factors to stimulate muscle stem cells to undergo osteoblast differentiation (36). These studies also used a murine model of fracture healing with injury to the periosteum. Muscle cells isolated from the region of the fracture after 3 days undergo spontaneous osteoblast differentiation and form bone nodules in cell culture. In contrast fasciocutaneous cells and muscle stem cells isolated from periosteum stripped bone without fracture do not undergo osteoblast differentiation (36). Subsequent experiments showed that 1) human bone fracture fragments in organ culture stimulate muscle stem cells to undergo osteoblast differentiation; 2) release the growth factors BMP-2, -4, and -7 and TGF-beta and the cytokines TNF-alpha, IL-1, and IL-6 into organ culture medium; and 3) that while inhibition of the BMPs and TGF-beta has no effect, neutralizing antibodies to both TNF-alpha and IL-6 block muscle stem cells osteogenesis in human bone fracture fragment organ culture (36). Finally, the authors showed that delivery of TNF-alpha to bone fractures with periosteal injury promoted healing. In contrast, anti-TNF-alpha treatment prevented fracture healing in mice with periosteal injury (36).

Lean muscle mass and bone health

Sarcopenia, or muscle wasting, is an important consequence of the aging process. The gradual loss of muscle mass and decrease in strength results in a functional decline and increased likelihood of accidents and falls (37). Bone densitometry studies show that the risk of low bone mass is increased with sarcopenia (38, 39). Recent gene wide association studies suggest that the phenotypic features of appendicular lean muscle mass and bone size phenotypes are co-regulated by multiple genes (40).

Because of the importance of lean muscle mass and its association with bone metabolism, anabolic agents to reduce sarcopenia and to increase bone mass are being considered as potential therapies (41, 42). With aging there is a reduction in the systemic levels of growth hormone and reduced localized IGF-I production in muscle tissues (43). Similarly, there is a reduction in testosterone production and estrogens in women with aging (43, 44). Hemodialysis patients develop sarcopenia and have reduced bone mass. In a placebo-controlled clinical trial the administration of the anabolic steroid oxymetholone to hemodialysis patients was associated with a reduction in fat and an increase in lean muscle mass, handgrip strength, and the expression of muscle related genes (42). A double-blinded placebo-controlled study showed that administration of a non-steroidal selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM) with tissue-selective anabolic effects in muscle and bone (GTx-024; enobosarm) resulted in significant increases in lean muscle mass and physical function in both men and women (41).

Summary and Conclusions

Muscle and the skeleton are intimately linked and both are necessary for locomotion and normal physical function. Injury to either tissue compromises physical function. Each tissue contains stem cell populations that participate in tissue repair and regeneration. Recent studies demonstrate that muscle-derived stem cells participate in bone repair, particularly in cases in which there is extensive periosteal injury. Similarly, bone fractures secrete cytokines and growth factors that influence muscle-derived stem cells and stimulate their differentiation into bone and cartilage tissues. There is a strong association between lean muscle mass and bone mass, and GWAS studies suggest that multiple genes co-regulate both muscle and bone mass. Preliminary studies suggest that anabolic agents for muscle improve physical function in the elderly and reduce the risk of fracture. More complete understanding of muscle-bone interactions will enable new therapies to reduce the morbidity of aging.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported in part by PHS awards RO1AR048861 (RJO) and P50AR954041 (RJO)

Footnotes

Disclosure

K Shah

Z Majeed

J Jonason

RJ O’Keefe declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Donaldson LJ, Reckless IP, Scholes S, Mindell JS, Shelton NJ. The epidemiology of fractures in England. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:174–180. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.056622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couris CM, Chapurlat RD, Kanis JA, Johansson H, Burlet N, Delmas PD, Schott AM. FRAX(R) probabilities and risk of major osteoporotic fracture in France. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:2321–2327. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson CL, Dilley K, Ness KK, Leisenring WL, Sklar CA, Kaste SC, Stovall M, Green DM, Armstrong GT, Robison LL, Kadan-Lottick NS. Fractures among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2012;118:5920–5928. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wukich DK, Kline AJ. The management of ankle fractures in patients with diabetes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1570–1578. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moghaddam A, Zimmermann G, Hammer K, Bruckner T, Grutzner PA, von Recum J. Cigarette smoking influences the clinical and occupational outcome of patients with tibial shaft fractures. Injury. 2011;42:1435–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sloan A, Hussain I, Maqsood M, Eremin O, El-Sheemy M. The effects of smoking on fracture healing. Surgeon. 2010;8:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alshryda S, Shah A, Odak S, Al-Shryda J, Ilango B, Murali SR. Acute fractures of the scaphoid bone: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2012;10:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedrich JB, Katolik LI, Hanel DP. Reconstruction of soft-tissue injury associated with lower extremity fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:81–90. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papakostidis C, Kanakaris NK, Pretel J, Faour O, Morell DJ, Giannoudis PV. Prevalence of complications of open tibial shaft fractures stratified as per the Gustilo-Anderson classification. Injury. 2011;42:1408–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claes L, Recknagel S, Ignatius A. Fracture healing under healthy and inflammatory conditions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:133–143. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colnot C, Zhang X, Knothe Tate ML. Current insights on the regenerative potential of the periosteum: molecular, cellular, and endogenous engineering approaches. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:1869–1878. doi: 10.1002/jor.22181. The current fracture healing paradigm regards the activation, expansion, and differentiation of periosteal stem/progenitor cells as an essential step in building a template for subsequent neovascularization, bone formation, and remodeling. Periosteal cells contribute more to cartilage and bone formation within the callus during fracture healing than do cells of the bone marrow or endosteum, which do not migrate out of the marrow compartment.

- 12.Zuscik MJ, Hilton MJ, Zhang X, Chen D, O'Keefe RJ. Regulation of chondrogenesis and chondrocyte differentiation by stress. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:429–438. doi: 10.1172/JCI34174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Histing T, Garcia P, Matthys R, Leidinger M, Holstein JH, Kristen A, Pohlemann T, Menger MD. An internal locking plate to study intramembranous bone healing in a mouse femur fracture model. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:397–402. doi: 10.1002/jor.21008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colnot C. Skeletal cell fate decisions within periosteum and bone marrow during bone regeneration. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:274–282. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081003. Periosteal injuries heal by endochondral ossification, whereas bone marrow injuries heal by intramembranous ossification, indicating that distinct cellular responses occur within these tissues during repair.

- 15.Lounev VY, Ramachandran R, Wosczyna MN, Yamamoto M, Maidment AD, Shore EM, Glaser DL, Goldhamer DJ, Kaplan FS. Identification of progenitor cells that contribute to heterotopic skeletogenesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:652–663. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu R, Birke O, Morse A, Peacock L, Mikulec K, Little DG, Schindeler A. Myogenic progenitors contribute to open but not closed fracture repair. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:288. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-288. Muscle lineage cells were genetically traced in a mouse. In a closed tibial fracture model, there was no significant contribution of muscle cells to the healing callus. In contrast, open tibial fractures featuring periosteal stripping and muscle fenestration had up to 50% of muscle derived stem cells detected in the open fracture callus.

- 17.Wosczyna MN, Biswas AA, Cogswell CA, Goldhamer DJ. Multipotent progenitors resident in the skeletal muscle interstitium exhibit robust BMP-dependent osteogenic activity and mediate heterotopic ossification. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1004–1017. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khosla S, Westendorf JJ, Modder UI. Concise review: Insights from normal bone remodeling and stem cell-based therapies for bone repair. Stem Cells. 2010;28:2124–2128. doi: 10.1002/stem.546. A number of animal and human studies have now shown the potential benefit of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in enhancing bone repair. However, the effect of marrow-derived cells is more likely due to induction of angiogenesis and recruitment of host progenitor cells rather than direct differentiation into osteoblasts.

- 19.Zhang X, Xie C, Lin AS, Ito H, Awad H, Lieberman JR, Rubery PT, Schwarz EM, O'Keefe RJ, Guldberg RE. Periosteal progenitor cell fate in segmental cortical bone graft transplantations: implications for functional tissue engineering. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2124–2137. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Augustin G, Antabak A, Davila S. The periosteum. Part 1: Anatomy, histology and molecular biology. Injury. 2007;38:1115–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cullen MC, Roy DR, Crawford AH, Assenmacher J, Levy MS, Wen D. Open fracture of the tibia in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1039–1047. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colnot C, Huang S, Helms J. Analyzing the cellular contribution of bone marrow to fracture healing using bone marrow transplantation in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:557–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumagai K, Vasanji A, Drazba JA, Butler RS, Muschler GF. Circulating cells with osteogenic potential are physiologically mobilized into the fracture healing site in the parabiotic mice model. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:165–175. doi: 10.1002/jor.20477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maes C, Kobayashi T, Selig MK, Torrekens S, Roth SI, Mackem S, Carmeliet G, Kronenberg HM. Osteoblast precursors, but not mature osteoblasts, move into developing and fractured bones along with invading blood vessels. Dev Cell. 2010;19:329–344. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.010. Osteoblast precursors were found to intimately associate with invading blood vessels, in pericyte-like fashion during bone development and fracture healing.

- 25.Reverte MM, Dimitriou R, Kanakaris NK, Giannoudis PV. What is the effect of compartment syndrome and fasciotomies on fracture healing in tibial fractures? Injury. 2011;42:1402–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu R, Schindeler A, Little DG. The potential role of muscle in bone repair. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2010;10:71–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harry LE, Sandison A, Paleolog EM, Hansen U, Pearse MF, Nanchahal J. Comparison of the healing of open tibial fractures covered with either muscle or fasciocutaneous tissue in a murine model. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1238–1244. doi: 10.1002/jor.20649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hao Y, Ma Y, Wang X, Jin F, Ge S. Short-term muscle atrophy caused by botulinum toxin-A local injection impairs fracture healing in the rat femur. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:574–580. doi: 10.1002/jor.21553. The injection of botulinum toxin-A (BXTA) with induction of muscle paralysis results in marked reduction in fracture healing compared with fracture healing in the contralateral femur.

- 29.Hou Z, Irgit K, Strohecker KA, Matzko ME, Wingert NC, DeSantis JG, Smith WR. Delayed flap reconstruction with vacuum-assisted closure management of the open IIIB tibial fracture. J Trauma. 2011;71:1705–1708. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31822e2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleming ME, Watson JT, Gaines RJ, O'Toole RV. Evolution of orthopaedic reconstructive care. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(Suppl 1):S74–S79. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollak AN, McCarthy ML, Burgess AR. Short-term wound complications after application of flaps for coverage of traumatic soft-tissue defects about the tibia. The Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP) Study Group. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A:1681–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis TA, O'Brien FP, Anam K, Grijalva S, Potter BK, Elster EA. Heterotopic ossification in complex orthopaedic combat wounds: quantification and characterization of osteogenic precursor cell activity in traumatized muscle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:1122–1131. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan FS, Lounev VY, Wang H, Pignolo RJ, Shore EM. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: a blueprint for metamorphosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1237:5–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tachi K, Takami M, Sato H, Mochizuki A, Zhao B, Miyamoto Y, Tsukasaki H, Inoue T, Shintani S, Koike T, Honda Y, Suzuki O, Baba K, Kamijo R. Enhancement of bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced ectopic bone formation by transforming growth factor-beta1. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:597–606. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cairns DM, Liu R, Sen M, Canner JP, Schindeler A, Little DG, Zeng L. Interplay of Nkx3.2, Sox9 and Pax3 regulates chondrogenic differentiation of muscle progenitor cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039642. The balance of Pax3, Nkx3.2 and Sox9 may act as a molecular switch during the chondrogenic differentiation of muscle progenitor cells, which may be important for fracture healing.

- 36. Glass GE, Chan JK, Freidin A, Feldmann M, Horwood NJ, Nanchahal J. TNF-alpha promotes fracture repair by augmenting the recruitment and differentiation of muscle-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1585–1590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018501108. Bone injury results in increased local TNF-alpha, which promotes MDSC migration followed by osteogenic differentiation.

- 37.Mithal A, Bonjour JP, Boonen S, Burckhardt P, Degens H, El Hajj Fuleihan G, Josse R, Lips P, Morales Torres J, Rizzoli R, Yoshimura N, Wahl DA, Cooper C, Dawson-Hughes B. Impact of nutrition on muscle mass, strength, and performance in older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2236-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu CH, Yang KC, Chang HH, Yen JF, Tsai KS, Huang KC. Sarcopenia is Related to Increased Risk for Low Bone Mineral Density. J Clin Densitom. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2012.07.010. Sarcopenia is a risk factor for low BMD.

- 39. Verschueren S, Gielen E, O'Neill TW, Pye SR, Adams JE, Ward KA, Wu FC, Szulc P, Laurent M, Claessens F, Vanderschueren D, Boonen S. Sarcopenia and its relationship with bone mineral density in middle-aged and elderly European men. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2057-z. Sarcopenia is associated with low BMD and osteoporosis in middle-aged and elderly men.

- 40.Guo YF, Zhang LS, Liu YJ, Hu HG, Li J, Tian Q, Yu P, Zhang F, Yang TL, Guo Y, Peng XL, Dai M, Chen W, Deng HW. Suggestion of GLYAT gene underlying variation of bone size and body lean mass as revealed by a bivariate genome-wide association study. Hum Genet. 2013;132:189–199. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1236-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalton JT, Barnette KG, Bohl CE, Hancock ML, Rodriguez D, Dodson ST, Morton RA, Steiner MS. The selective androgen receptor modulator GTx-024 (enobosarm) improves lean body mass and physical function in healthy elderly men and postmenopausal women: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2011;2:153–161. doi: 10.1007/s13539-011-0034-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Supasyndh O, Satirapoj B, Aramwit P, Viroonudomphol D, Chaiprasert A, Thanachatwej V, Vanichakarn S, Kopple JD. Effect of Oral Anabolic Steroid on Muscle Strength and Muscle Growth in Hemodialysis Patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 doi: 10.2215/CJN.00380112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giannoulis MG, Martin FC, Nair KS, Umpleby AM, Sonksen P. Hormone replacement therapy and physical function in healthy older men. Time to talk hormones? Endocr Rev. 2012;33:314–377. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horstman AM, Dillon EL, Urban RJ, Sheffield-Moore M. The role of androgens and estrogens on healthy aging and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:1140–1152. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]