Abstract

Shoulder ultrasound is consistently used in the assessment of rotator cuff and is as accurate as magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of rotator cuff tear. It can be used as a focused examination providing rapid, real-time diagnosis, and treatment in desired clinical situations. This article presents a simplified approach to scanning and image-guided intervention, and discusses common sonographically apparent shoulder pathologies.

Keywords: Shoulder, ultrasound, technique, pathology

Introduction

Shoulder ultrasound has been in use for quite some time is considered operator-dependent, and has a proven accuracy in rotator cuff assessment.[1,2,3,4,5] Scanning the shoulder can be challenging and time-consuming in the beginning. The use of a protocol-driven examination, understanding of pertinent anatomy, tendon orientation, and familiarity with imaging pitfalls, can improve individual performance.[6,7,8] This essay presents a simplified approach to scanning the shoulder, and also illustrates the pathological findings.

Technique

There are various techniques for scanning the shoulder,[6,7,9] some operators prefer to face the patient, and others prefer to stand behind, scanning over the patient's shoulder. The author prefers to scan standing behind the patient and recommends following a protocol that the user is comfortable with. The probe should be held at its end with the edge of the hand resting on the patient's shoulder, in order to reduce stress and allow fine motor control. Obtaining a brief history at the beginning of the examination can provide clues to the underlying pathology. Good-quality ultrasound equipment and a high-frequency (12-15 MHz) linear-array (with a flat surface) probe is required. The more the transducer frequency, which improves the resolution, the less is the depth penetration. Probe frequency selection depends on the patients build. Lower for obese patient and higher for thin patient. Tissue harmonic imaging can increase the conspicuity of tears, although, no difference in the diagnostic accuracy has been found.[10] How much you adjust the machine controls and settings as you scan is very much a matter of taste. Some familiarity and understanding of the controls is an essential especially, if you are not the only one who uses the scanner. The author recommends following a systematic approach for scanning the shoulder [Table 1].

Table 1.

Shoulder ultrasound examination techniques

Shoulder Evaluation-Technique and Abnormalities

Biceps tendon

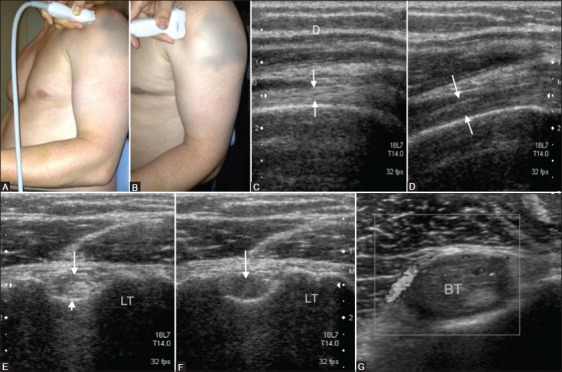

The tendon can be readily identified in the intertubercular groove on the anterolateral aspect of the humerus with the arm in a neutral position and is examined in both transverse and longitudinal planes [Figure 1A and B]. It is important not to confuse anisotropy due to probe angulation [Figure 1C-F] with tendinopathy [Figure 1G]. Small amounts of fluid can normally be seen surrounding the tendon. This can easily be differentiated from tenosynovitis where there are internal echoes within the fluid with areas of increased Doppler flow.

Figure 1.

(A-G): Biceps tendon. Probe placement to examine long head of the biceps tendon in transverse plane (A) and longitudinal plane (B). Long head of biceps tendon (arrows) in longitudinal (C) and transverse plane (E) appears hypoechoic (D and F) (arrows) due to anisotrophy when not imaged perpendicular to the sound beam. Hypoechoic appearance (G) of biceps tendon with areas of increased Doppler signal as a result of tendinopathy. LT: Lesser tuberosity

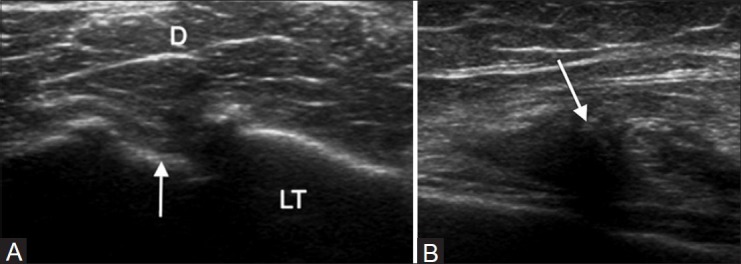

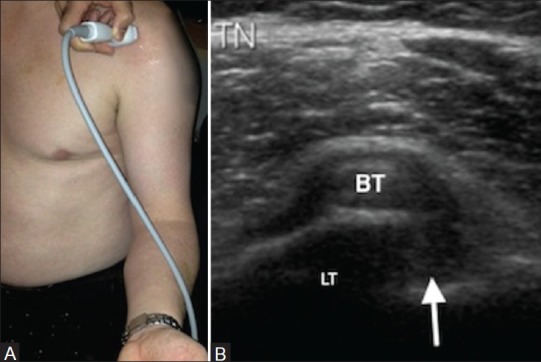

Biceps tendon can rupture in either an acute or chronic setting. Acute rupture results in non-visualization of the tendon within the bicipital groove [Figure 2A] and biceps muscle contraction with bulbous appearance/popeye sign [Figure 2B]. In chronic rupture there is partial non-visualization of the upper portion of the tendon. An empty bicipital groove becomes filled with echogenic scar tissue that simulates a normal Long head of biceps tendon [Figure 3], although the characteristic fibrillar pattern of the tendon is not seen.[11] The patient then externally rotates the arm [Figure 4A] and the long head of the biceps is again examined for any subluxation [Figure 4B] from its position in the groove.

Figure 2.

(A, B): (A) Transverse scan of torn long head of biceps tendon with an empty bicipital groove (arrow). (B) Longitudinal scan shows the convex superior margin (arrow) of the retracted muscle belly (popeye sign). LT: Lesser tuberosity, D: Deltoid

Figure 3.

Short-axis view of the long head of the biceps tendon with bicipital groove (arrow) filled with scar tissue simulating an attenuated biceps tendon. LT: Lesser tuberosity

Figure 4.

(A, B): (A) Transducer position for evaluating long head of biceps tendon stability and the subscapularis tendon in a longitudinal plane. Note the arm externally rotated and elbow flexed at 90°. (B) Medial subluxation of the biceps tendon with an empty intertubercular groove (arrow) suggestive of biceps instability. LT: Lesser tuberosity

Subscapularis tendon

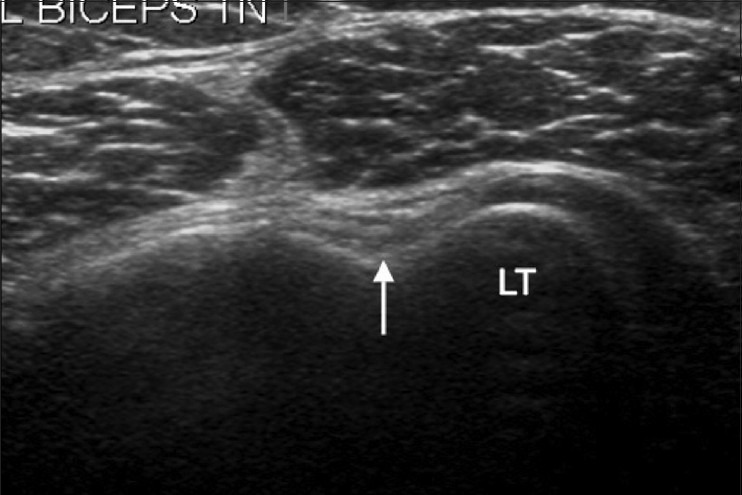

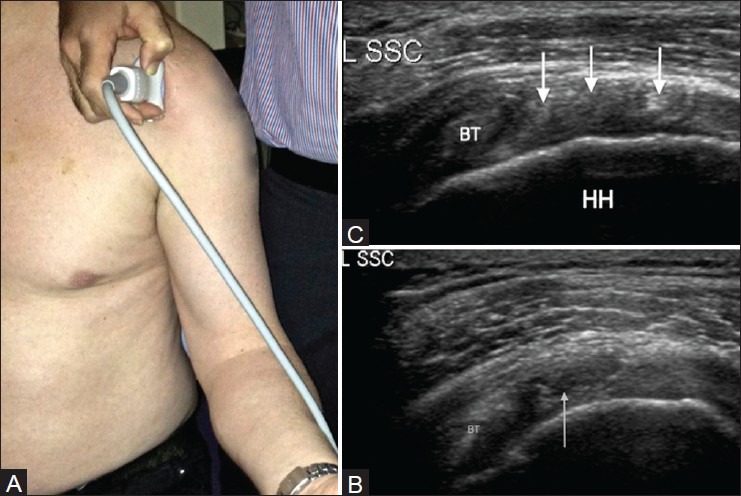

While the arm is passively externally rotated the subscapularis can be examined in orthogonal planes from its insertion into the lesser tuberosity to the point at which it becomes hidden to ultrasound by the coracoid process medially. Diagnosing subscapularis injury is clinically difficult and assessment of subscapularis integrity may be limited during arthroscopy or open surgery.[12] It is important to assess the superior portion of the tendon, close to the biceps tendon, on the transverse view [Figure 5] for any tears.

Figure 5.

(A-C): (A) Transducer position for a transverse image of the subscapularis tendon. (B) Corresponding transverse image of the subcapularis tendon. Note the hyperechoic tendon slips (arrows) between the hypoechoic muscle fibers. (C) Short-axis view of the subscapularis tendon with a partial-thickness articular surface tear in its superior part (arrow). Biceps tendon seen on the left of the image. L SSC: Left subscapularis, BT: Biceps tendon, HH: Humeral head

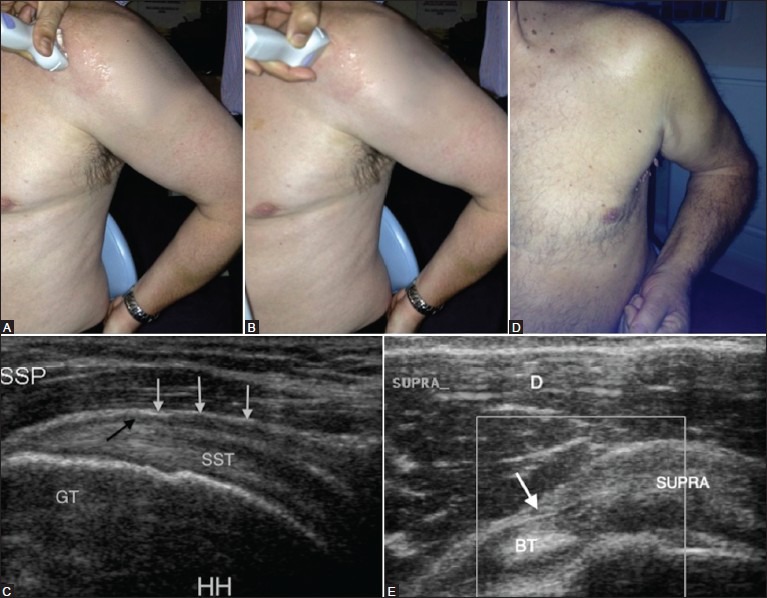

Supraspinatus tendon (SST)

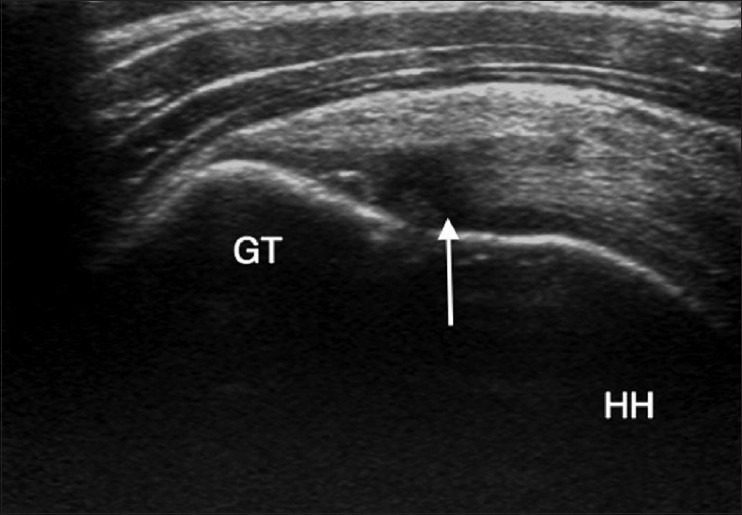

In order to visualize the SST the patients are asked to place their hand on their back pocket [Figure 6A and B]. In the longitudinal plane [Figure 6C] the tendon has a beak-shaped configuration. It is important to be able to see the anterior border of the supraspinatus, a common site for tear, in the short axis/transverse plane and this may sometimes require scanning with the elbow drawn backward [Figure 6D]. This makes the arm a less internally rotated (than with the hand on the back pocket) and brings the rotator interval [Figure 6E] out. At the insertion of the supraspinatus into the humerus the tendon fibrils turn to insert perpendicular to the bone cortex. This means that an area of low reflectivity due to anisotropy may be seen within the tendon at its insertion [Figure 7] and the probe will need to be angled to avoid confusing this for a tear. Various patterns of supraspinatus tears occur [Table 2].

Figure 6.

(A-E): Supraspinatus tendon (SST). Transducer placement for supraspinatus tendon in long-axis (A) and short-axis (B) with the hand on the back pocket. Longitudinal view of the SST (C) with overlying thin hypoechoic line (black arrow) representing subacromial subdeltoid bursa and the overlying subdeltoid fat (white arrows). Elbow backward position (F) to see the anterior border of supraspinatus tendon in transverse plane (E) with the echogenic component of biceps tendon sling, coracohumeral ligament (arrow). GT: Greater tuberosity, HH: humeral head, D: Deltoid muscle

Figure 7.

Longitudinal view of the supraspinatus tendon with an area of reduced echogenicity due to anisotrophy, at the site of tendon insertion over the greater tuberosity, which is not to be confused with a tear. HH: Humeral head

Table 2.

Various patterns of supraspinatus tear

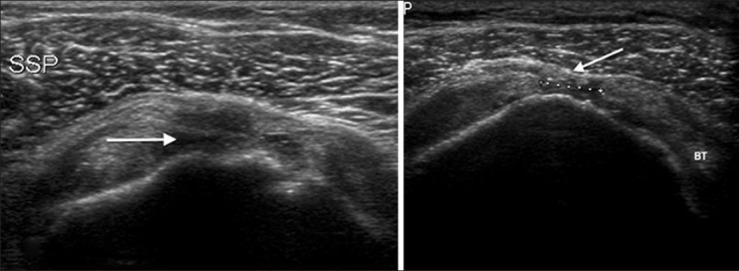

Full-thickness tear

A full-thickness rotator cuff tear is a defect in the tendon that reaches from the bursal to the articular margin.[13] Typically, these tears occur at the footprint of the greater tuberosity where the tendon fibers insert, and then propagate proximally. Full-thickness rotator cuff tears are quantified as small (<1 cm), medium (1-3 cm), large (3-5 cm) and massive (>5 cm) according to DeOrio and Cofield classification,[14] measured in its longest dimension. The normal tendon echogenicity is replaced by a hypoechoic or anechoic defect and the length or degree of retraction of a full-thickness tear (measured on longitudinal views oriented parallel to the long axis of the cuff) and width (measured on transverse views oriented perpendicular to the long axis of the cuff) is assessed, since this information is needed by orthopedic surgeon for deciding management and to prognosticale outcome of therapy.[15] Secondary or indirect signs are reliable criteria for the detection of rotator cuff tears.[16] When fluid is present in the subacromial/subdeltoid bursa and in the glenohumeral joint, the probability of a rotator cuff tear is 95%. Other indirect signs of partial or full-thickness rotator cuff tears are the sagging of bursa [Figure 8A] and a bright aspect of the humeral cartilage (cartilage interface sign or uncovered cartilage sign), which is caused by enhancement of the ultrasound signal due to fluid and loss of cuff tissue above the cartilage [Figure 8B].

Figure 8(A, B).

(A) Longitudinal view of supraspinatus tendon (SSP). Full-thickness tear of the tendon (long arrow) that reaches from the bursal to the articular margin with sagging of the overlying bursa (short arrow). (B) Long-axis view of the right SSP. Partial thickness articular surface tear (black arrow) and a bright anterior aspect of humeral cartilage (white arrow) – Cartilage interface sign

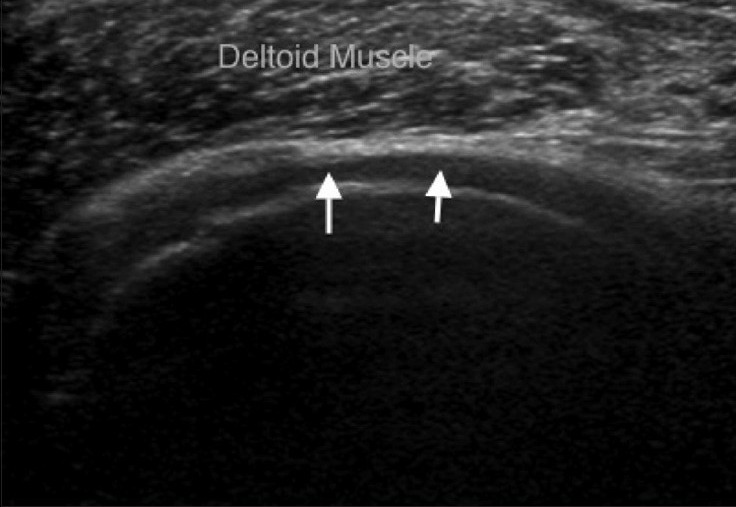

A complete tear of the tendon involves the whole width of the tendon. A full-thickness tear may be complete or may only involve the anterior free edge [Figure 9A] or mid substance [Figure 9B]. A massive cuff tear [Figure 10] occurs when the entire attachment of SST to the greater tuberosity is disrupted, allowing the tendon to retract proximally beneath the acromion. These tears may extend to involve the infraspinatus (IST), subscapularis and the long head of the biceps.

Figure 9 (A, B).

(A) Full-thickness tear (arrow) in anterior free edge of supraspinatus tendon. Tiny echogenic shadows due to blood particles (thin arrow) are seen to move on dynamic compression. Note irregularity over the greater tuberosity (arrowhead). (B) Short-axis view of left supraspinatus tendon. There is a full-thickness tear in the mid-portion of the tendon (between the markers) with sagging of the overlying bursa (arrow). BT: Biceps tendon

Figure 10.

Short-axis view of supraspinatus tendon. There is a massive tear of the tendon with the deltoid muscle lying directly on the humeral head cartilage (arrows)

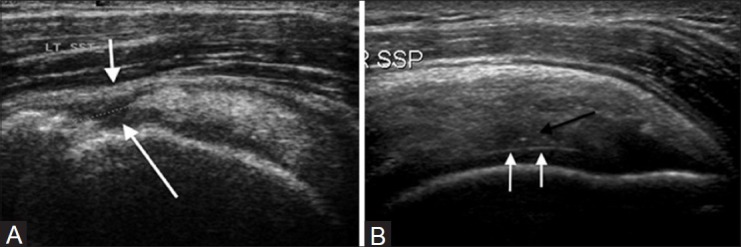

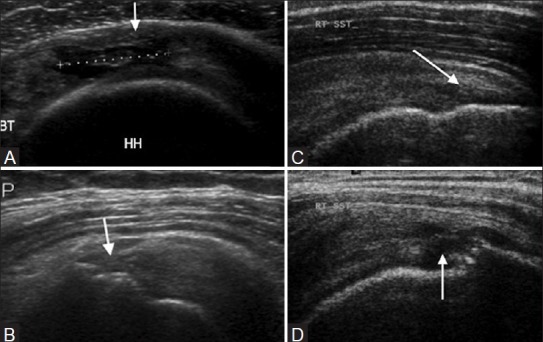

Partial-thickness cuff tear

Partial-thickness tear is a focal discontinuation, which is limited to tears affecting either the articular surface [Figure 11A] (common) or the bursal surface [Figure 11B] (uncommon) of the tendon, but without communication of the tear to the opposing tendon surface. Partial-thickness tears have been classified by Ellman[17] by the depth of the tear, as Grade 1 for tears less than 3 mm; grade 2 for tears 3-6 mm; and grade 3 for those greater than 6 mm. These can also be divided into “high-grade” (greater than 50% thickness) or “low-grade” (less than 50% thickness). A cortical bone irregularity of the greater tuberosity is a sensitive sign of an articular-side partial-thickness tear.[16] Occasionally, a partial tear may propagate proximally within the tendon substance [Figure 11C] causing a “de-laminating tear.” A rim rent tear [Figure 11D] is an articular surface tear near the footplate of the tendon.

Figure 11 (A-D).

Partial-thickness tear of supraspinatus tendon. (A) Short-axis view. There is a partial-thickness articular surface tear in the mid-substance of the tendon (between markers) with a few intact fibers overlying (arrow). (B) Partial-thickness bursal surface tear (arrow) of the supraspinatus tendon. (C) Partial-thickness intrasubstance tear (arrow). (D) Partial tear (rim rent) of supraspinatus tendon at greater tuberosity (arrow). BT: Biceps tendon, HH: Humeral head

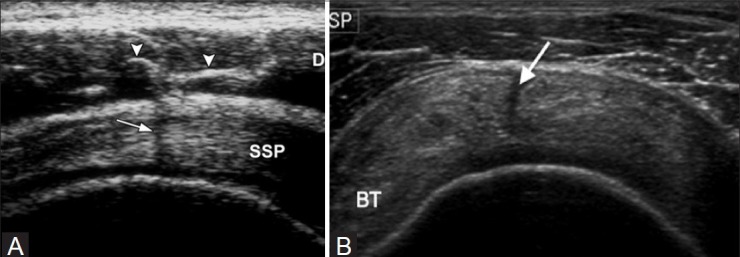

The deltoid tendinous intersections cause an acoustic shadow (i.e., a refractile shadow) when they are relatively thick or scanned tangentially. This causes a hypoechoic area within the tendon [Figure 12A], which can simulate a rotator cuff tear.[18] This needs to be distinguished from a true tear [Figure 12B] through the tendon substance, which does not extend into the echogenic superficial layer of the subacromial-subdeltoid (SASD) bursa.

Figure 12 (A, B).

(A) Deltoid septum. Short-axis US scan of the supraspinatus tendon in a normal volunteer shows hyperechoic lines (arrowheads) in the deltoid muscle (D), which represent septa of connective tissue. A posterior acoustic shadow (arrow) may appear when the insonating beam is perpendicular to the septa. (Reprinted by permission: Figure 5, Rutten M JCM, Jager G J, Blickman J G: US of the rotator cuff: pitfalls, limitations, and artifacts. Radiographics 2006;26:589-604). (B) Tear (arrow) through the supraspinatus tendon substance

Tendon inhomogeneity

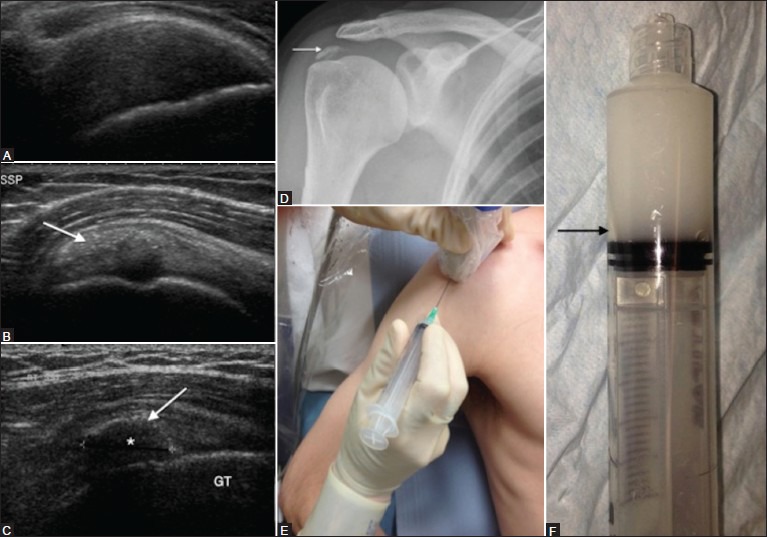

Inhomogeneities of the tendon are frequently encountered with degenerative changes of the tendon (i.e., tendinosis).[19] In tendinosis, a tendon can appear hypoechoic [Figure 13A] due to an increased amount of fluid and/or amyloid deposits in and between the tendon fibers.[20] Tendinosis is often coexistent with partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. These may be difficult to detect when they are located in an area of tendinosis. With long-standing impingement (i.e., chronic tendinosis), calcium may be deposited in the rotator cuff tendons and/or the SASD bursa. Because of its structure (e.g., milk of calcium) or size, calcification may have a fluffy appearance, with echogenic foci without posterior shadowing [Figure 13B], or may appear as typical discrete, well-circumscribed calcifications with posterior shadowing [Figure 13C]. Correlation with plain radiographs [Figure 13D] is necessary. It is believed that the calcifications become symptomatic when the calcium undergoes resorption.[21] Ultrasound guided fine-needle puncture [Figure 13E], and lavage has been proposed as an effective treatment prior to possible surgery.[22,23] The technique involves successive propulsion and aspiration of the calcium, which can be readily identified in the syringe as a white cloud-like substance mixing with the lidocaine that would then deposit in the dependent portion of the syringe [Figure 13F] and then 40 mg of triamcinolone is injected into the bursa.

Figure 13 (A-F).

Tendon inhomogeneity. Supraspinatus tendinosis (A). The tendon is thickened and has reduced echogenicity. Long-axis view of SST showing soft (B) and hard (C) calcification (arrow) without posterior shadowing. Note the shadow (*) behind the hard calcification. Right shoulder Anteroposterior (AP) radiograph (D) with dense supraspinatus calcification (arrow). Probe placement for ultrasound-guided aspiration (E) and lavage of tendon calcification. Patient in semi-inclined position with arm behind the back. Calcium aspirate mixed with lignocaine (F) with a layer of calcium deposit (black arrow)

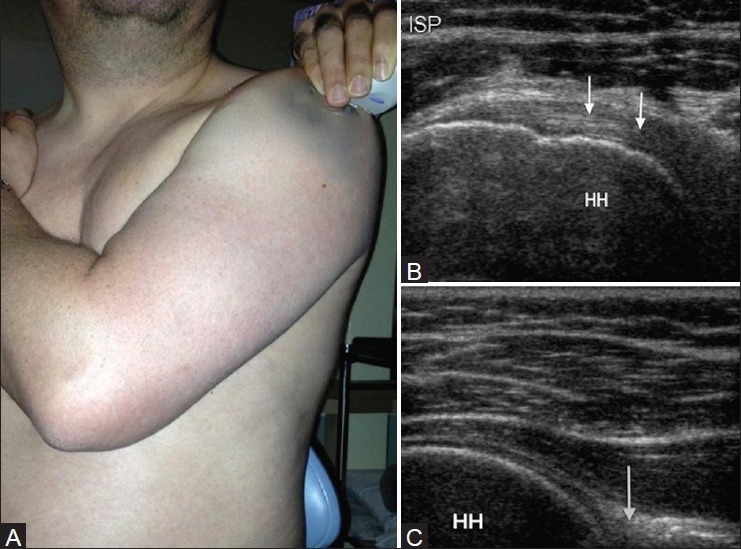

Infraspinatous (IST) and teres minor tendons

The IST and teres minor tendons lies more posteriorly and can be well visualized with the arm in a flexed and adducted position. This can be done by asking the patient to places their arm across the front of their body [Figure 14A]. The IST is demonstrated in longitudinal section as a beak-shaped soft-tissue structure [Figure 14B]. In this position, the scan depth can be increased to visualize the posterior aspect of the gleno-humeral joint [Figure 14C]. This presents a further opportunity to look for joint effusion. Isolated IST tears are uncommon but may be encountered in association with internal (postero-superior) impingement in individuals involved with over-arm throwing activities. The teres minor tendon may be visualized as a trapezoid structure and can be differentiated from the IST by its oblique internal echoes. Teres minor is found to be normal in most rotator cuff tears[24] and may not be scanned routinely. Isolated Teres minor atrophy, caused by compression of the posterior humeral circumflex artery and axillary nerve in the quadrilateral space, may be identified on ultrasound.

Figure 14(A-C).

Infraspinatous tendon. (A) Probe placement over the posterior aspect of the shoulder for examination of infraspinatous tendon (long-axis), posterior glenohumeral joint and spinoglenoid notch. (B) Corresponding US image shows characteristic contour of the humeral head with adjacent infraspinatous tendon (arrow). (C) US image showing glenoid labrum (black arrow) and the posterior aspect of the glenohumeral joint

Accuracy

Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are comparable in both sensitivity and specificity. Ultrasound has 92.3% sensitivity and 94.4% specificity for full-thickness and 66.7% sensitivity and 93.5% specificity for partial-thickness tear. MR arthrography is the most sensitive and specific technique for diagnosing both full-and partial-thickness rotator cuff tears.[25]

Non-rotator cuff abnormalities

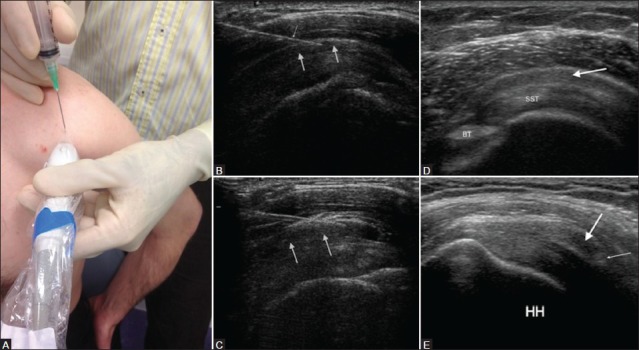

There is a spectrum of non-rotator cuff abnormalities that are amenable to US examination. Once adequate radiographs have been obtained to exclude apparent bone disorders, high-resolution US should be the first-line imaging modality in the assessment of non–rotator cuff disorders of the shoulder, assuming the study is performed with high-end equipment by an experienced examiner.[26] Subacromial impingement syndrome[27] is the result of chronic irritation of the SST against the undersurface of the anterior one-third of the acromion, the coracoacromial ligament, and the acromioclavicular joint. This process leads to tendinopathy and tears of the rotator cuff as well as SASD bursitis. While shoulder impingement is a clinical diagnosis, ultrasound is routinely used to help evaluate the condition by demonstrating supportive findings, discovering alternative causes of shoulder pain, and directing therapeutic injections [Figure 15A-C]. The SASD bursitis is demonstrated by the presence of increased fluid in the bursa and/or thickening of the wall of the bursa [Figure 15D]. Gathering of the SASD bursa [Figure 15E] demonstrated during dynamic ultrasound, which has been reported as a useful feature in diagnosing impingement by some authors[28,29,30] does not necessarily indicate painful impingement of the bursa as it is found to a similar degree in patients with a clinical diagnosis of impingement, and healthy volunteers.[31]

Figure 15 (A-E).

Subacromial impingement. (A) Probe placement for injecting subacromial subdeltoid bursa. Patient sitting on stool with hand on back pocket position. (B) Long-axis view of supraspinatus tendon (SST) showing needle (thin arrow) in the subacromial subdeltoid bursa (arrows) prior to injecting steroid and lignocaine mixture. (C) Expansion of the bursa (arrows) following injection. (D) Subacromial subdeltoid bursitis with thickened bursa (arrow) overlying the SST. (E) Thickening or gathering of the bursa (thick arrow) under coracoacromial ligament (thin arrow). HH: Humeral head

Fatty atrophy of the rotator cuff muscles is an important consideration in assessing the prognosis in-patients being considered for rotator cuff surgery. Sonographic assessment of fatty atrophy is by calculating the occupation ratio, measured by dividing the cross-sectional surface area of the supraspinatus muscle by that of its fossa.[32] The ultrasound features and grading of fatty atrophy are relatively subjective but they correlate well with MRI findings.[7,32] Fatty infiltration causes loss of normal muscle pennate pattern, loss of conspicuity of the central tendon and increased echogenicity of the muscle and is measured by comparing it echogenicity with that of trapezius muscle. US has been found to be moderately accurate in the diagnosis of substantial fatty atrophy of the supraspinatus or IST muscle.[33] It has been documented that extended field of view sonography results in greater interrater reliability than conventional sonography for the detection of rotator cuff muscle atrophy.[34] In our practice we use MRI for the assessment of fatty infiltration and rotator cuff muscle atrophy inpatients being considered for cuff repair.

US is helpful in evaluating the superior aspect of the acromio-clavicular joint. Bone erosion, fluid, cysts, and hypertrophic changes represent degeneration. An acromio-clavicular joint cysts may present as a tumor mass. They are associated with extensive rotator cuff tears and there is usually communication of the cyst with the joint space.[35,36,37]

Conclusion

The ultrasound image quality has substantially improved with technological advancement, producing spatial resolution exceeding that obtained with MRI. Ultrasound gives the ability to provide direct correlation of the imaging findings with the symptoms of the patient, and helps with guided interventional procedures.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Kettering General Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Northants, UK

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Smith TO, Back T, Toms AP, Hing CB. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound for rotator cuff tears in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:1036–48. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Middleton WD, Teefey SA, Yamaguchi K. Sonography of the rotator cuff: Analysis of interobserver variability. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1465–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.5.1831465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Connor PJ, Rankine J, Gibbon WW, Richardson A, Winter F, Miller JH. Interobserver variation in sonography of the painful shoulder. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005;33:53–6. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNally EG, Rees JL. Imaging in shoulder disorders. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:1013–6. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moosikasuwan JB, Miller TT, Burke BJ. Rotator cuff tears: Clinical, radiographic, and US findings. Radiographics. 2005;25:1591–607. doi: 10.1148/rg.256045203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson JA. Shoulder US: Anatomy, technique, and scanning pitfalls. Radiology. 2011;260:6–16. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beggs I. Shoulder ultrasound. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2011;32:101–13. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moosikasuwan JB, Miller TT, Burke BJ. Rotator cuff tears: Clinical, radiographic, and US findings. Radiographics. 2005;25:1591–607. doi: 10.1148/rg.256045203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finnoff JT, Smith J, Peck ER. Ultrasonography of the shoulder. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21:481–507. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strobel K, Zanetti M, Nagy L, Hodler J. Suspected rotator cuff lesions: Tissue harmonic imaging versus conventional US of the shoulder. Radiology. 2004;230:243–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2301021517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teefey SA, Middleton WD, Yamaguchi K. Shoulder sonography. State of the art. (ix).Radiol Clin North Am. 1999;37:767–85. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morag Y, Jamadar DA, Miller B, Dong Q, Jacobson JA. The subscapularis: Anatomy, injury, and imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:255–69. doi: 10.1007/s00256-009-0845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandt TD, Cardone BW, Grant TH, Post M, Weiss CA. Rotator cuff sonography: A reassessment. Radiology. 1989;173:323–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.173.2.2678248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeOrio JK, Cofield RH. Results of a second attempt at surgical repair of a failed initial rotator-cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:563–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morag Y, Jacobson JA, Miller B, De Maeseneer M, Girish G, Jamadar D. MR imaging of rotator cuff injury: What the clinician needs to know. Radiographics. 2006;26:1045–65. doi: 10.1148/rg.264055087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson JA, Lancaster S, Prasad A, van Holsbeeck MT, Craig JG, Kolowich P. Full-thickness and partial-thickness supraspinatus tendon tears: Value of US signs in diagnosis. Radiology. 2004;230:234–42. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2301020418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellman H. Diagnosis and treatment of incomplete rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:64–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutten MJ, Jager GJ, Blickman JG. From the RSNA refresher courses: US of the rotator cuff: Pitfalls, limitations, and artifacts. Radiographics. 2006;26:589–604. doi: 10.1148/rg.262045719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan PA, Bryans KC, Davick JP, Otte M, Stinson WW, Dussault RG. MR imaging of the normal shoulder: Variants and pitfalls. Radiology. 1992;184:519–24. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.2.1620858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole AS, Cordiner-Lawrie S, Carr AJ, Athanasou NA. Localised deposition of amyloid in tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:561–4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b4.11547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farin PU, Jaroma H. Sonographic findings of rotator cuff calcifications. JUltrasound Med. 1995;14:7–14. doi: 10.7863/jum.1995.14.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurt G, Baker CL., Jr Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:567–75. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(03)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aina R, Cardinal E, Bureau NJ, Aubin B, Brassard P. Calcific shoulder tendinitis: Treatment with modified US-guided fine-needle technique. Radiology. 2001;221:455–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2212000830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melis B, DeFranco MJ, Lädermann A, Barthelemy R, Walch G. The teres minor muscle in rotator cuff tendon tears. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:1335–44. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Jesus JO, Parker L, Frangos AJ, Nazarian LN. Accuracy of MRI, MR arthrography, and ultrasound in the diagnosis of rotator cuff tears: A meta-analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1701–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papatheodorou A, Ellinas P, Takis F, Tsanis A, Maris I, Batakis N. US of the shoulder: Rotator cuff and non-rotator cuff disorders. Radiographics. 2006;26:e23. doi: 10.1148/rg.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neer CS., 2nd Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farin PU, Jaroma H, Harju A, Soimakallio S. Shoulder impingement syndrome: Sonographic evaluation. Radiology. 1990;176:845–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.176.3.2202014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins RA, Gristina AG, Carter RE, Webb LX, Voytek A. Ultrasonography of the shoulder. Static and dynamic imaging. Orthop Clin North Am. 1987;18:351–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bureau NJ, Beauchamp M, Cardinal E, Brassard P. Dynamic sonography evaluation of shoulder impingement syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:216–20. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daghir AA, Sookur PA, Shah S, Watson M. Dynamic ultrasound of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa in patients with shoulder impingement: A comparison with normal volunteers. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41:1047–53. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khoury V, Cardinal E, Brassard P. Atrophy and fatty infiltration of the supraspinatus muscle: Sonography versus MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1105–11. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strobel K, Hodler J, Meyer DC, Pfirrmann CW, Pirkl C, Zanetti M. Fatty atrophy of supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles: Accuracy of US. Radiology. 2005;237:584–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kavanagh EC, Koulouris G, Parker L, Morrison WB, Bergin D, Zoga AC, et al. Does extended-field-of-view sonography improve interrater reliability for the detection of rotator cuff muscle atrophy? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:27–31. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craig EV. The acromioclavicular joint cyst. An unusual presentation of a rotator cuff tear. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;202:189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marino AJ, Tyrrell PN, el-Houdiri YA, Kelly CP. Acromioclavicular joint cyst and rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:435–7. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(98)90040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tshering Vogel DW, Steinbach LS, Hertel R, Bernhard J, Stauffer E, Anderson SE. Acromioclavicular joint cyst: Nine cases of a pseudotumor of the shoulder. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:260–5. doi: 10.1007/s00256-004-0883-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]