Abstract

Cystic masses of neck consist of a variety of pathologic entities. The age of presentation and clinical examination narrow down the differential diagnosis; however, imaging is essential for accurate diagnosis and pretreatment planning. Ultrasound is often used for initial evaluation. Computed tomography (CT) provides additional information with regard to the extent and internal composition of the mass. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) has a supplementary role for confirmation of diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging may be needed in some cases for preoperative assessment.

Keywords: Cystic masses, imaging, neck

Introduction

Cystic masses of neck are frequently encountered on imaging. Although clinical history and examination may suggest the diagnosis, imaging is required to confirm the clinical diagnosis and assess the anatomical extent of the lesion before treatment. Cystic masses of neck include a wide range of congenital and acquired lesions. The latter include various inflammatory and neoplastic diseases. High-resolution ultrasound (US) is an ideal initial imaging investigation for neck masses as it reveals the cystic nature in most cases and localizes the mass in relationship to the surrounding structures. Development of three-dimensional technology, color, and power Doppler applications has led to great improvement in its diagnostic utility. Computed tomography (CT) is superior as it confirms the findings of US, determines the extent of lesion, and is especially useful in demonstration of calcification or fat within the lesion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a supplementary role in work-up of cystic neck masses. Its multi-planar capability and superior contrast resolution allow precise preoperative anatomical localization, particularly for more deep-seated and locally extensive lesions. T2-weighted MRI particularly helps to distinguish cystic from solid components. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) may be required for confirmation of diagnosis in some cases.

This pictorial review presents the clinical and radiologic features of the cystic and cyst-like masses of the neck. For convenience, these have been classified into cystic masses, which are commonly congenital and cyst-like masses.

Cystic Masses

Thyroglossal duct cyst

Thyroglossal duct cyst (TDC) is the most common midline congenital neck mass accounting for 70% of the congenital neck anomalies.[1] The cyst occurs along the residual tract left by the thyroid gland after descent from the foramen cecum at the tongue base to its final position in the visceral space. About 90% of the patients present before 10 years of age, with a second group of patients presenting in young adulthood.[2,3] No gender predilection has been reported.[1]

The cyst is located at the level of hyoid bone (15-50%), below it (25-65 %), or in suprahyoid location (20-25 %). The typical cyst is deep to or embedded in the infrahyoid strap muscles.[4] The more inferior the cyst, the more likely it is to be off the midline.

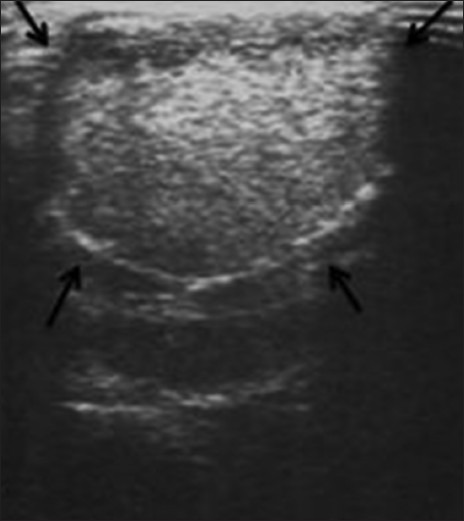

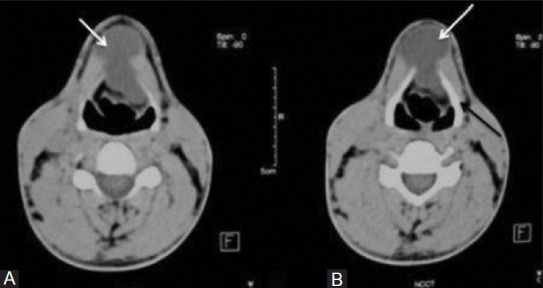

On US, a typical thyroglossal duct cysts appears as a smooth, well-circumscribed anechoic lesion with posterior enhancement in the anterior neck. However, this appearance is seen in 42% cases only.[5] The rest of the lesions show a hypo-echoic echo pattern, with internal echoes, either homogenous or heterogeneous, due to repeated infections, hemorrhage, or proteinaceous content. An echogenic pseudo solid appearance may also be seen [Figure 1]. On CT, a thyroglossal cyst is seen as a well-circumscribed, thin-walled fluid attenuation mass [Figure 2]. It may have higher attenuation or show peripheral enhancement following intravenous contrast administration. On MRI, it is invariably hyper-intense on T2-weighted sequences. Signal intensity on T1-weighted images is highly variable due to difference in cystic content, with T1hyper-intensity seen in lesions with high proteinaceous cystic content.

Figure 1.

US image showingpseudosolid appearance of a thyroglossal duct cyst in the infrahyoid location

Figure 2 (A, B).

Thyroglossal duct cyst: Axial non-contrast CT images show midline cystic (white arrows) mass (A) just above and (B) at the level of hyoid bone (black arrow)

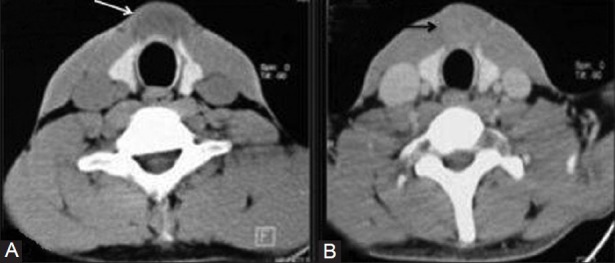

In adults, thyroid carcinoma can develop in a TDC, with an incidence of 1%, the most common being the papillary subtype. Presence of solid soft tissue elements, often nodular, within a thyroglossal cyst is highly suspicious of malignancy [Figure 3]. Calcification within the cyst is thought to be a specific finding of carcinoma within TDC.[3] The presence of carcinoma in a TDC indicates the need for an additional thyroidectomy,[6] as up to 14% of patients will have a coincident microscopic focus of papillary carcinoma within the thyroid gland.[7] Carcinomas may also be seen as purely solid masses along the course of the thyroglossal duct. In contrast to their traditional counterparts in the thyroid gland, carcinomas arising within these cysts rarely metastasize to cervical lymph nodes.[1,8]

Figure 3 (A, B).

Thyroglossal duct cyst with papillary thyroid carcinoma: (A) Axial plain and (B) contrast-enhanced CT images show anterior midline cystic lesion (white arrow) in infrahyoid location with enhancing solid component (black arrow)

Branchial cleft cysts

Branchial cleft anomalies arise from incomplete obliteration of any branchial tract, resulting in either a cyst (75%) or a sinus or fistulous tract (25%).[9]

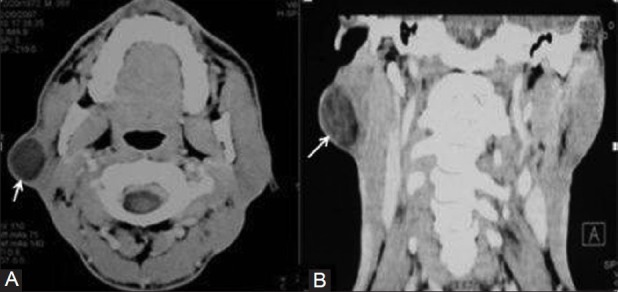

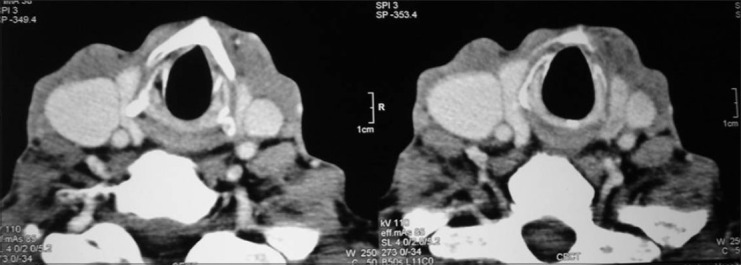

First branchial cleft anomalies are relatively less common and typically closely related to the parotid gland. These commonly present as fistula and sinus, whereas cysts are least common. The usual appearance is an oval or round cystic mass within, superficial to, or deep to the parotid gland or along the external auditory canal [Figure 4]. It should always be included in the differential diagnosis of cystic lesion in the parotid or peri-parotid region.

Figure 4 (A, B).

First branchial cleft cyst: (A) Axial and (B) coronal contrast enhanced CT images show a well defined hypodense mass (arrows) within the right parotid gland

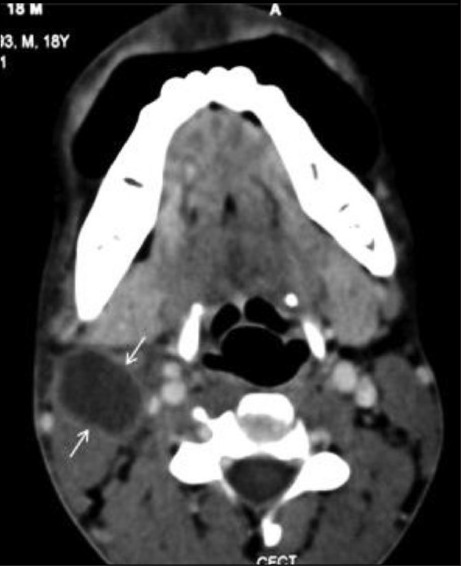

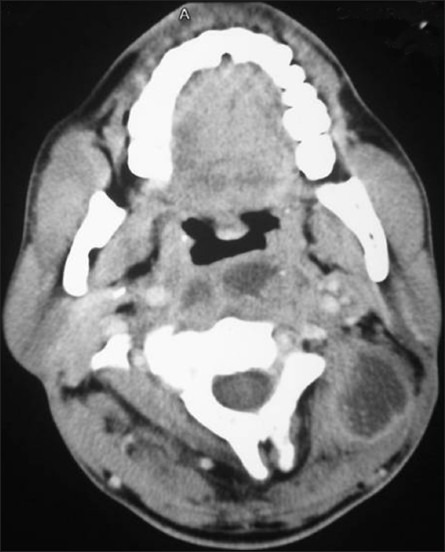

Second branchial anomalies comprise 95% of all branchial cleft lesions, most commonly presenting as cystic masses rather than sinuses or fistulas.[5] Bailey[10] has classified second branchial cleft cysts (BCCs) into four types—Type-I occurs anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle just deep to the platysma muscle; type-II is the commonest type and occurs deep to the sternocleidomastoid and lateral to the carotid space; type-III extends medially between the bifurcation of internal and external carotid arteries to the lateral pharyngeal wall; and type-IV occurs in the pharyngeal mucosal space medial to the carotid sheath. A second BCC can occur anywhere in the lateral aspect of neck, but is classically seen as a well-marginated anechoic mass with a thin, well-defined wall at the anteromedial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the junction of its upper and middle third, lateral to the carotid space and at the posterior margin of the sub-mandibular gland [Figure 5]. It may show thick walls or internal septations or echoes. On CT it is seen as a well-circumscribed, non-enhancing mass of homogenous low attenuation [Figure 6]. Sometimes a beak sign may be seen as a curved rim of the lesion pointing medially between the internal and external carotid. Wall thickening and enhancement may occur due to associated inflammation. When a sinus or fistula is present, the external opening is typically along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the junction of its middle and lower thirds, its internal opening being in the region of the palatine tonsillar fossa.

Figure 5.

Second branchial cleft cyst: Contrast enhanced CT scan reveals a cystic lesion (arrows) in the right neck lateral to the carotid sheath, behind the submandibular gland and along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle

Figure 6.

Beak sign in second branchial cleft cyst: Contrast enhanced CT image demonstrates a curved rim of hypodense mass (arrows) pointing between left internal and external carotid arteries

Third and fourth branchial cleft anomalies are exceedingly rare and typically present with a long history of neck infections. Both are related to the pyriform sinus with those of the third cleft being above the superior laryngeal nerve and those of the fourth being below the nerve. Third BCCs are located in the posterior cervical space posterior to the common or internal carotid artery and the sternocleidomastoid muscle. They may present as a fistula opening along the anterior border of sternocleidomastoid. Its tract passes posterior to the common carotid artery, and enters the thyroid membrane to reach the pharynx at the pyriform sinus.

Fourth branchial cleft anomalies are generally sinus tracts or fistulae and arise from the pyriform sinus, pierce the thyrohyoid membrane, and descend along the tracheoesophageal groove.

Lymphangioma

Lymphangiomas arise from early sequestration of embryonic lymphatic channels,[11] most commonly developing along the jugular chain.

Four types of lymphangioma are described based on microscopicsize of dilated lymphatic channels-cystic hygroma, cavernous lymphangioma, capillary lymphangioma, and vasculolymphatic malformation.[12]

Cystic hygromas are the most common form of lymphangioma; 75% of these occur in the neck, usually centered in the posterior triangle or the sub-mandibular space. These lesions are characteristically infiltrative in nature and do not respect facial planes. The mediastinum and axilla are common sites of their extension.[13] Sudden enlargement may occur due to hemorrhage or infection. On US, these appear as multi-locular cystic masses, with septations of variable thickness. Fluid-fluid levels may be present when the lesions are complicated by hemorrhage. CT shows these as poorly circumscribed, multi-loculated, hypodense masses with fluid attenuation [Figure 7]. Higher density may be observed in infected or hemorrhagic lesions. MRI typically demonstrates low or intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and hyper-intensity on T2-weighted images. T1 hyper-intensity may be seen with hemorrhage or lipid content. Fluid level may also be seen.

Figure 7.

Cystic hygroma: Axial contrast-enhanced CT images show low-attenuation insinuating cystic mass (arrows) in the posterior triangle of left side of neck in a 3 month old child

Dermoid and epidermoid cysts

Dermoid and epidermoid cysts may occur anywhere in the body, with 7% presenting as head-and-neck lesions, most commonly lateral to the eyebrow.[5] Dermoid cysts are lined by the epithelium and differ from epidermoid cysts in that they contain skin appendages such as sebaceous glands and hair follicles within the cyst wall. Complex dermoid cysts contain mesodermal elements like cartilage, bone, and fat. Dermoid cysts usually manifest during the second and third decades of life as slow-growing mass in the sub-mandibular or sublingual space. Epidermoid cysts manifest earlier in life, with most lesions evident during infancy. These are usually seen as well-defined anechoic masses with posterior enhancement in the midline of neck. These may show homogenous internal echoes. Heterogeneous appearance may be seen due to the presence of echogenic fat, osseous, or dental elements [Figure 8]. The floor-of-the-mouth lesions typically present as thin-walled, unilocular masses located in the sub-mandibular or sublingual space. The rim of the cyst may show contrast enhancement. On non-contrast CT, dermoid cyst usually appears as a low-density, unilocular, well-circumscribed mass. Fat, mixed-density fluid, and calcification (<50%) may also be seen There may be coalescence of fat into small nodules within the cystic lesion, giving a “sac-of-marbles” appearance [Figure 9]. The presence of calcifications and cystic spaces in these lesions aids in their differentiation from lipomas.

Figure 8.

Dermoid cyst. A sonogram of the floor of mouth showing a well-defined cyst with posterior acoustic enhancement and a heterogeneous echopattern due to fat globules

Figure 9.

Dermoid cyst. The axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a cystic lesion in the midline in the floor of the mouth, with small discrete areas of fatty attenuation characteristically giving a “sac-of-marbles” appearance

Epidermoid cysts usually show fluid-density material [Figure 10]. Post contrast, the lesion wall may be imperceptible or may show subtle rim enhancement. Malignant degeneration into squamous cell carcinoma is seen in upto 5% of lesions.[14]

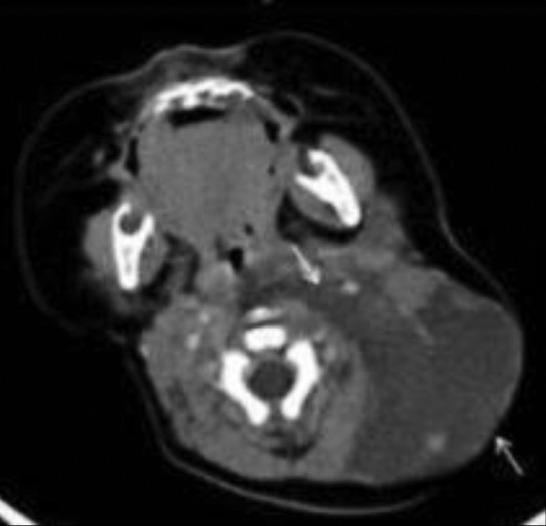

Figure 10(A-C).

Epidermoid cyst. (A) The axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a cystic attenuation lesion centered in the floor of the mouth. (B) The axial and (C) Sagittal MR T2-weighted image reveals a well-defined T2 hyper-intense lesion in the floor of the mouth in the same patient

Thymic cyst

Thymic cysts are uncommon lesions that arise from persistence of the thymopharyngeal duct.[15] These occur adjacent to the carotid sheath anywhere from the hyoid bone to the anterior mediastinum.[16] The common age of presentation is 2-15 years, with slight male predilection. The thymic cysts may have a similar appearance to third and fourth BCCs, being differentiated only by the presence of thymic tissue within thymic cysts. The cysts usually present as a unilocular cystic mass extending inferiorly within the neck, paralleling the sternocleidomastoid muscle, or as a dumbbell-shaped left cervicothoracic cystic mass [Figure 11].

Figure 11(A, B).

Thymic cyst. (A) The axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a cystic lesion in the right side of the neck caudal to the thyroid gland displacing the trachea to the left. (B) The coronal reformatted image shows the lesion is parallel to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, extending into the upper mediastinum

Laryngocele

A laryngocele is considered to have a congenital derivation, although it usually manifests in adults.[5] It is dilatation of the laryngeal saccule, a small pouch arising from the roof of the ventricle.[17] The laryngeal ventricle is a slit-like cavity, with the orifice located between the true and false cords. Laryngoceles are of three types—internal, external, and mixed. Those confined to the larynx are known as internal laryngoceles. Those that extend through the thyrohyoid membrane, but with dilation of only the extra-laryngeal component, are termed external. Mixedlaryngoceles have dilatation of the saccule on both sides of the thyrohyoid membrane. Fifteen percent of laryngoceles are associated with carcinoma,[18] with tumor occluding the orifice of the laryngeal ventricle. A laryngocele may become infected and is then called a laryngopyocele.

A sharply defined oval or round lucent area in the para-laryngeal soft tissues on a radiograph is diagnostic of laryngocele. On CT, a laryngocele may is seen as a well-defined fluid, with anair or soft tissue attenuation mass in the lateral aspect of the superior para-laryngeal space [Figure 12]. Demonstration of a connection between the air sac and the airway confirms the diagnosis. It may contain an air-fluid level. The presence of soft tissue within it suggests an underlying laryngeal neoplasm.

Figure 12.

Laryngocele: Axial contrast-enhanced CT image shows air filled internal laryngocele (arrow) on the right and mixed laryngocele (arrowhead) on the left side

Cervical bronchogenic cysts

Cervical bronchogenic cysts are extremely rare, which result from an anomalous foregut development. They are usually located in the thyroid or para-tracheal region, rarely in the suprasternal or supraclavicular location. Definitive diagnosis of bronchogenic cyst requires histopathological confirmation.

Ranulas

Ranulas represent cystic lesions of the floor of the mouth, usually occurring secondary to obstruction of the sublingual duct. Therefore these are also called sublingual gland mucocele or mucous retention cyst. Ranulas may be either “simple” and confined to the sublingual space or “plunging/diving,” which extend posteriorly into the sub-mandibular space or through a mylohyoid defect.[19] Rarely ranulas can dissect across the midline between the mylohyoid and geniohyoid muscles to present as a bilateral mass. Giant ranulas have also been described, which extend into the para-pharyngeal space and have a narrower tail that extends through the sublingual space.

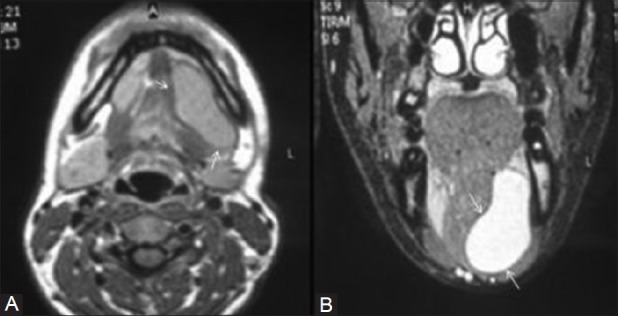

On US, a ranula appears as a unilocular, well-defined, cystic lesion in the sub-mental region deep to the mylohyoid muscle. It may contain fine internal echoes, usually due to presence of debris from previous episodes of inflammation. For a diving ranula, the bulk of the cystic collection is in the sub-mandibular region, but a small beak may be seen within the sublingual space. CT shows a simple ranulaas an ovoid shaped cyst with a homogeneous central attenuation region of 10-20 HU, which lies lateral to the genioglossal muscles deep to the mylohyoid muscle [Figure 13]. Ranulas may become infected and show a thick, irregular rim of enhancement, with surrounding inflammatory change. On MRI, a ranula usually shows low signal intensity on the T1-weighted sequence and high signal intensity on T2-weighted sequence [Figure 14]. Occasionally when the protein content of the cystic fluid is high, the lesion will appear hyper-intense on the T1-weighted sequence.

Figure 13.

Plunging ranula: Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a cystic attenuation lesion (arrows) in the floor of the mouth with a characteristic ‘tail sign’ extending into the submandibular space

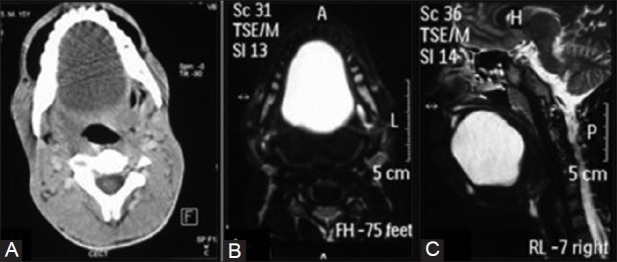

Figure 14(A, B).

Plunging ranula. The (A) Axial MR T1-weightedimages and the (B) Coronal T2-weightedimages show a cystic lesion having a fluid signal in the floor of the mouth

Cyst-like Masses

Cystic metastatic lymph node

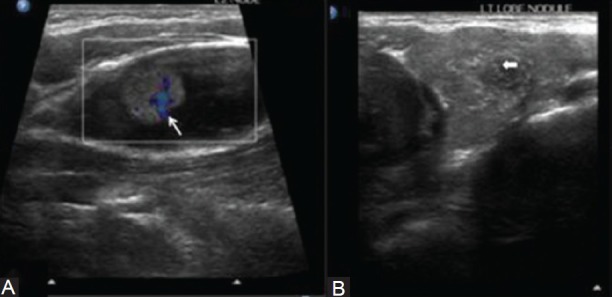

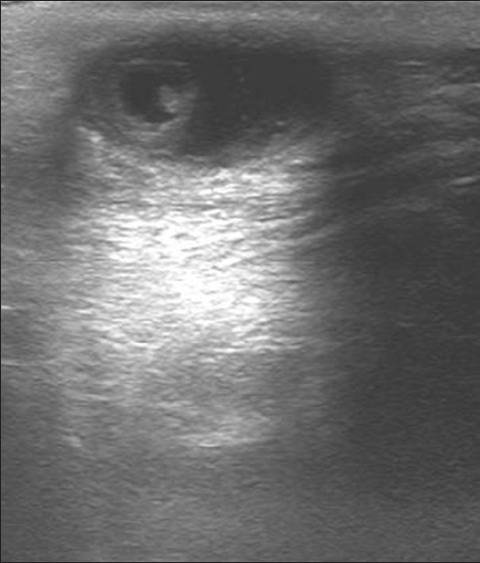

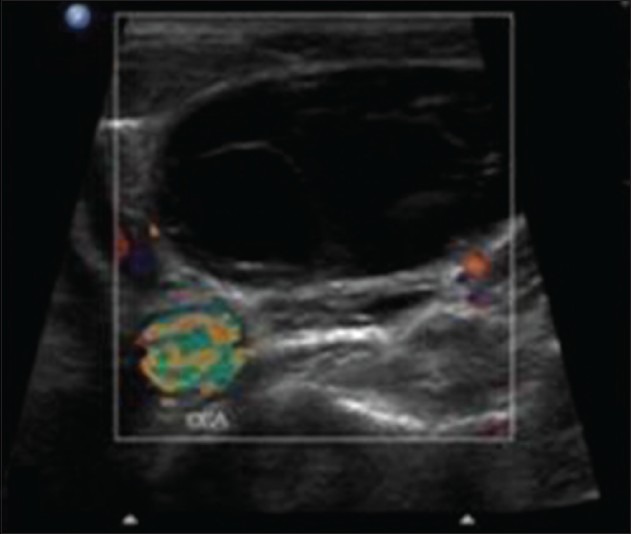

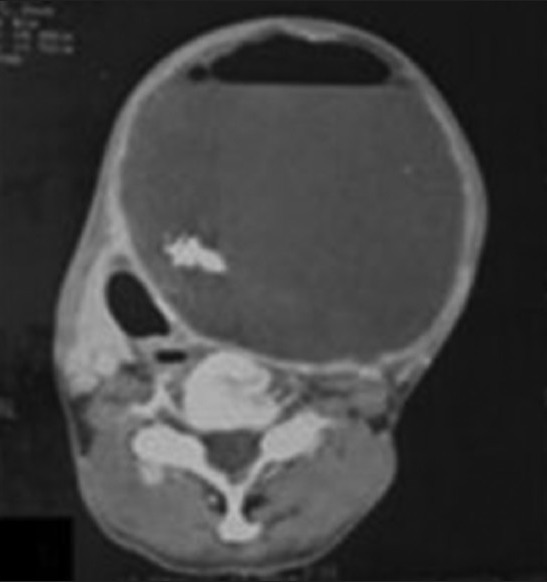

Metastatic nodes from head-and-neck malignancy, especially papillary carcinoma of the thyroid, are the most common types of nodal metastases presenting as cystic masses in the neck. Eighty percent of the cystic masses in patients over 40 years of age are due to necrotic lymph nodes.[20] On US, a central cystic area with thick irregular walls or an eccentric solid component may be seen. These solid areas usually demonstrate increased peripheral and intra-lesional vascularity on Doppler [Figure 15]. Presence of punctate calcification within the solid component of the cystic node warrants careful search for primary papillary carcinoma in the thyroid gland. Occasionally necrosis within a metastatic lymph node may be very florid, mimicking a congenital cyst, such as a second BCC. CT shows cystic nodal necrosis as a focal area of low attenuation with or without a surrounding rim of soft-tissue enhancement. On MRI, it shows high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and low signal intensity on T1-weighted images.

Figure 15(A, B).

A metastatic node in a papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. (A) US showinga cystic node with a solid component, which has internal vascularity and micro-calcification, and (B) A poorly defined nodule with micro-calcification in the left lobe of the thyroid

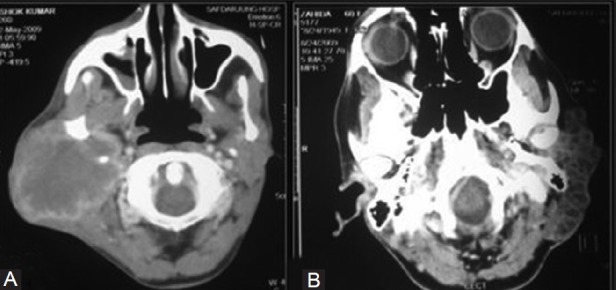

Neurogenic tumors

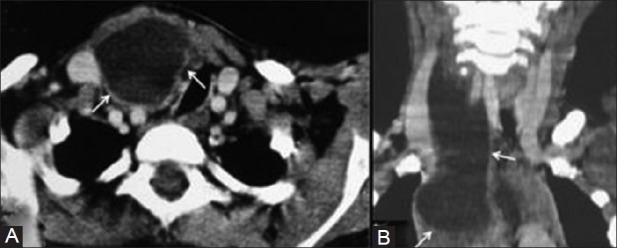

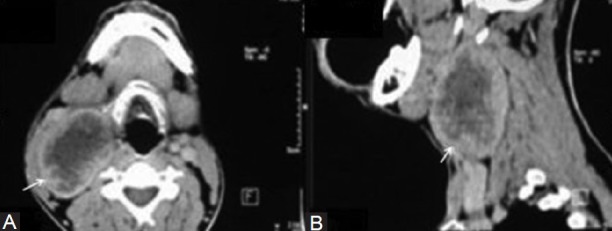

Neurogenic tumors are well known in the head-and-neck region in the carotid space (vagus nerve or sympathetic chain) or in the posterior cervical space (spinal nerve or brachial plexus). It is not uncommon for cystic areas to develop within intracranial and extra-cranial schwannomas, and neurofibromas, either due to mucinous degeneration, hemorrhage, or necrosis. The imaging features of these benign masses include non-infiltrative smooth margins, long-axis fusiform shape, bone remodeling, non-homogeneous MR signal intensities, and presence of fluid-fluid levels.[21] Characteristically, neurogenic tumors around the carotid sheath are located posterior to the neck vessels [Figure 16], whereas paragangliomas cause splaying and are located between the external and internal carotid arteries. A benign cystic schwannoma or neurofibroma should be considered high in the differential diagnosis of a mass that occurs along a nerve distribution, is relatively silent clinically, and there is no associated lymphadenopathy,

Figure 16(A, B).

Neurogenic tumor. The (A) Axial and (B) Sagittal contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a heterogeneously enhancing lesion with cystic necrosis in the right side of the neck characteristically located posterior to the great vessels of the neck

Vascular

Rarely vascular lesions (pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula/malformation, venous vascular malformation, and phlebectasia) may appear as cystic masses in the neck.

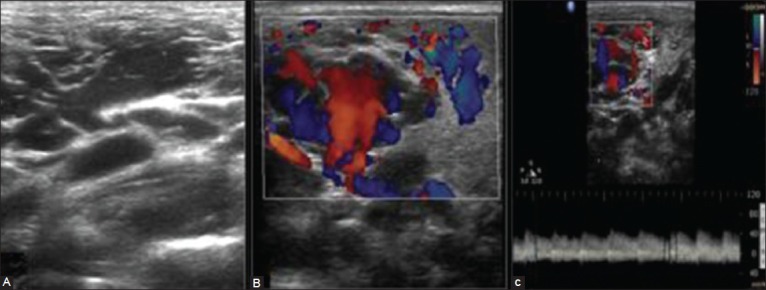

Venous malformations are low-flow vascular malformations that consist of dysplastic, endothelium-lined venous channels. When there are lymphatic elements present, then it is known as mixed lymphaticovenous malformation. The characteristic imaging finding is presence of phleboliths. On US, a heterogeneousecho pattern with a compressible collection of variably sized vascular channels is seen. On Doppler evaluation, the lesion shows monophasic, low-velocity venous flow.

Arteriovenous fistula or malformations are high-flow lesions seen as heterogeneous, hypo-echoic masses of multiple tortuous channels, which show intense color filling on Doppler examination [Figure 17].

Figure 17(A-C).

Arterio-venous malformation. (A) A US of a young female with a swelling right side of the neck revealing multiple anechoic tortuous channels. (B) Color Doppler US revealing intense color filling and (C) Arterial waveforms within the lesion with a Peak Systolic Velocity (PSV) of 40 cm/s

MRI is the best imaging technique to depict the exact anatomical location and extent, especially for large and deep-seated lesions.

Phlebectasia is dilatation of an isolated vein. The most commonly affected vein in the neck is the internal jugular vein [Figure 18]. Clinically, it presents as a cervical swelling that expands with increased intra-thoracic pressure. Doppler US examination identifies the dilated internal jugular vein and venous blood flow on the Valsalva maneuver.

Figure 18.

Phlebectasia. The axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows phlebectasia of the right internal jugular vein

Infections/inflammatory lesions

Various infections and inflammatory lesions in the neck region manifesting as cyst-like masses are adenitis, abscesses, acute suppurative thyroiditis, and cellulitis.

Tuberculous lymphadenitis has a predilection for the posterior triangle of the neck. On imaging, a necrotic discrete or conglomerate lymph nodal mass with surrounding soft-tissue edema is seen [Figure 19].[22]

Figure 19.

Tubercular lymph node. US revealing a large necrotic lymph node in the posterior triangle of the neck

Abscesses may occur anywhere in the neck, but common locations are the sub-mandibular, retropharyngeal, and parotid space. On US, an abscess appears as a hypo- to anechoic mass, with peripheral thick, shaggy margins. On CT, an abscess usually appears as a single or multi-loculated low-density area with rim enhancement [Figure 20]. Internal gas collections may be present.[23]

Figure 20.

Abscess. The axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a low-attenuation lesion in the retropharyngeal and posterior triangle in the left side of neck with thick peripheral enhancement

Cystic lesions of salivary glands

Salivary gland cysts may be classified into congenital and acquired types. Congenital cysts may be present at birth but do not become evident clinically until adulthood. Various types of congenital/developmental cysts are lymphoepithelial cysts, BCCs, epidermoid cysts, polycystic disease, congenital sialectasis, and Merkel's cyst. Acquired cysts are sialocysts, pneumoceles, AIDS-related parotid cysts, ranula, and cystic tumors of the salivary gland.[24]

Sialocystsare acquired cysts, which occur as a result obstruction of the duct due to inflammation, calculus, trauma, postsurgical complication, or a mass. These are true cysts with epithelial linings. Patients most commonly present in the fifth decade and the most common site is the sub-mandibular gland. Needle aspiration of saliva from the cyst confirms diagnosis.[25]

Cystic tumors of salivary gland: Low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, papillary-cystic variant of acinic cell carcinoma [Figure 21], and papillary adenocarcinoma are the three low-grade lesions that may present as cystic tumors most commonly affecting the parotid gland.[24]

Figure 21(A, B).

Parotid masses. The (A) Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a heterogeneously enhancing lesion in the right the parotid gland in a case of mucoepidemoid carcinoma. The (B) Axial CT scan in an adenoidocystic carcinoma showsa multi-cystic infiltrating lesion in the left parotid region

Cystic lesions of thyroid

True epithelial thyroid cysts are rare. Most cystic lesions are due to hemorrhage or degeneration within a hyper-plastic nodule of multi-nodular goiter. On US, these appear as well-defined cystic or predominantly cystic lesions with internal septae [Figure 22]. The comet tail sign suggestive of colloid may also be seen.

Figure 22.

Thyroid lesions. US showing a cystic lesion with internal septae within the right lobe of the thyroid gland characteristic of colloid degeneration

Rarely acute suppurative thyroiditis and associated abscess are seen especially in children [Figure 23]. On US, this manifests as an ill-defined hypo-echoic heterogeneous mass with internal debris. There is obliteration of peri-thyroidal fat planes along with reactive lymphadenopathy in the neck. CT shows a single or multi-loculated low-density area with rim enhancement within an enlarged thyroid. Internal gas bubbles may also be seen.

Figure 23.

The axial contrast-enhanced CT scan showsa cystic lesion within the left lobe of the thyroid gland, with calcification and air-fluid level suggestive of abscess formation

Summary

Cystic lesions of the neck are commonly encountered on imaging studies. Clinical presentation along with imaging features such as anatomical location, extent, internal composition, vascularity as assessed by Doppler US, or contrast enhancement on CT help in accurate diagnosis. These imaging modalities also aid in optimal pre-operative planning.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Allard R. The thyroglossal cyst. Head Neck Surg. 1982;5:134–46. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harnsberger H. 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby-Yearbook; 1992. Handbook of Head and Neck Imaging; pp. 1184–243. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Telander R, Deane S. Thyroglossal and branchial cleft cysts and sinuses. Surg Clin North Am. 1977;57:779–91. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pound LA. Neck masses of congenital origin. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1981;28:841–4. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koeller KK, Alamo L, Adair CF, Smirniotopoulos JG. Congenital cystic masses of the neck: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radio Graphics. 1999;19:121–46. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.1.g99ja06121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller EW. Origins and treatment of cystic lesions in the head and neck region. Available from: http://web.up.ac.za/sitefiles/File/45/1335/4101/Microsoft%20Word%20%20Origins%20and%20treatment%20of%20cystic%20lesions%20in%20the%20HN%20region%20DR%20MULLERS.pdf .

- 7.Ward P, Strahan R, Acquarelli M, Harris P. The many faces of cysts of the thyroglossal duct. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1970;74:310–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez JF, Ordonez NG, Schultz PN, Saman NA, Hickey S. Thyroglossal duct carcinoma. Surgery. 2001;110:928–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deane SA, Telander RL. Surgery for thyroglossal duct and branchial cleft anomalies. Am J Surg. 1978;136:348–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey H. London, England: Lewis; 1929. Branchial Cysts and Other Essays on Surgical Subjects in the Facio-Cervical Region. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith D. Genetic, Embryologic, and Clinical Aspects. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1982. Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformation; pp. 472–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harnsberger HR, Wiggins RH, Hudgins PA, Davidson HC, Macdonald AJ, Glastonbury CM, et al. 1st ed. Altona: Amirsys; 2004. Diagnostic Imaging Head and Neck; pp. 30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emery PJ, Bailey CM, Evans JN. Cystic hygroma of the head and neck. J Laryngol Otol. 1984;98:613–9. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100147176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Som P. Cystic lesions of the neck. Postgrad Radiol. 1987;7:211–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarbo RJ, McClatchey KD, Areen RG, Baker SB. Thymopharyngeal duct cyst: A form of cervical thymus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1983;92:284–9. doi: 10.1177/000348948309200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrahim M, Hammoud K, Maheshwari M, Pandya A. Congenital cystic lesions of thehead and neck. Neuroimag Clin North Am. 2011;21:621–39. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delahunty JE, Cherry J. The laryngeal saccule. J Laryngol Otol. 1969;83:803–15. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100070985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canalis RF, Maxwell DS, Hemenway WG. Laryngocele-an updated review. J Otolaryngol. 1977;6:191–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La’Porte SJ, Juttla JK, Ravi K, Lingam RK. Imaging the floor of the mouth and the sublingual space. Radiographics. 2011;31:1215–30. doi: 10.1148/rg.315105062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Granstrom G, Edstrom S. The relationship between cervical cysts and tonsillar carcinoma in adults. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:16–20. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catalano P, Fang-Hui E, Som PM. Fluid-fluid levels in benign neurogenic tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:385–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman ER, John SD. Imaging ofpediatric neck masses. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49:617–32. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong KT, Lee YY, King AD, Ahuja AT. Imaging of cystic or cyst-like neck masses. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:613–22. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Som P, Curtin HD. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002. Head and Neck Imaging; pp. 2006–133. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Som P, Shugar J, Biller H. Parotid gland sarcoidosis and the CT-sialogram. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1981;5:674–7. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198110000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]