Abstract

Objective To develop and evaluate a best practice model of general hospital acute medical care for older people with cognitive impairment.

Design Randomised controlled trial, adapted to take account of constraints imposed by a busy acute medical admission system.

Setting Large acute general hospital in the United Kingdom.

Participants 600 patients aged over 65 admitted for acute medical care, identified as “confused” on admission.

Interventions Participants were randomised to a specialist medical and mental health unit, designed to deliver best practice care for people with delirium or dementia, or to standard care (acute geriatric or general medical wards). Features of the specialist unit included joint staffing by medical and mental health professionals; enhanced staff training in delirium, dementia, and person centred dementia care; provision of organised purposeful activity; environmental modification to meet the needs of those with cognitive impairment; delirium prevention; and a proactive and inclusive approach to family carers.

Main outcome measures Primary outcome: number of days spent at home over the 90 days after randomisation. Secondary outcomes: structured non-participant observations to ascertain patients’ experiences; satisfaction of family carers with hospital care. When possible, outcome assessment was blind to allocation.

Results There was no significant difference in days spent at home between the specialist unit and standard care groups (median 51 v 45 days, 95% confidence interval for difference −12 to 24; P=0.3). Median index hospital stay was 11 versus 11 days, mortality 22% versus 25% (−9% to 4%), readmission 32% versus 35% (−10% to 5%), and new admission to care home 20% versus 28% (−16% to 0) for the specialist unit and standard care groups, respectively. Patients returning home spent a median of 70.5 versus 71.0 days at home (−6.0 to 6.5). Patients on the specialist unit spent significantly more time with positive mood or engagement (79% v 68%, 2% to 20%; P=0.03) and experienced more staff interactions that met emotional and psychological needs (median 4 v 1 per observation; P<0.001). More family carers were satisfied with care (overall 91% v 83%, 2% to 15%; P=0.004), and severe dissatisfaction was reduced (5% v 10%, −10% to 0%; P=0.05).

Conclusions Specialist care for people with delirium and dementia improved the experience of patients and satisfaction of carers, but there were no convincing benefits in health status or service use. Patients’ experience and carers’ satisfaction might be more appropriate measures of success for frail older people approaching the end of life.

Trial registration Clinical Trials NCT01136148

Introduction

Older people admitted to hospital with acute physical illness or injury often have cognitive impairment, mostly from dementia, delirium, or both.1 2 3 Outcomes for those with cognitive impairment are worse than for those without.1 4 5 6 Of a series of cognitively impaired older people admitted to hospital, 31% died, 42% were readmitted, and 24% of those initially living in the community moved to a care home within six months.3 Family carers are often stressed.7 They complain that healthcare staff do not recognise or understand dementia, that communication is poor, and that little stimulation is provided in hospital. Hospital staff report lack of training and that they struggle to deal with difficult behaviours and keeping patients safe.8 9 10

Some specialist delirium units or combined medical and mental health units have been established.8 11 12 Recent systematic reviews found that most published reports were descriptive and robust evaluations were lacking.13 14 We developed a specialist medical and mental health unit for older people with suspected dementia or delirium15 as a model of best practice and evaluated it in a randomised controlled trial.16 We hypothesised that the unit would improve outcomes, experience, and satisfaction compared with standard care.

Methods

Study design

We recruited patients admitted for acute medical care to a large British National Health Service hospital providing sole emergency medical services for its local population. Suitable patients were identified on the acute medical admission unit and were randomly allocated between the specialist unit and standard care. Randomised patients were subsequently approached for recruitment to the study. This approach was necessary so that patients could be moved from the admission unit to wards at any time of day or day of the week at the pace required for the efficient operation of the hospital yet allowing sufficient time for patients to be recruited ethically.

Study participants

Participants were aged over 65, and identified by physicians in the admissions unit as being “confused.” We used the term “confused” as there is considerable overlap between delirium and dementia in this population,1 presentation to emergency care is usually with undifferentiated confusion rather than a specific diagnosis,3 dementia is often undiagnosed in the community and hospital,1 6 and skill in mental health diagnosis is sometimes poor in acute medical settings. Patients with a clinical need for another specialist service (such as critical care, surgery, or stroke unit) were excluded. We recruited a family member or carer, if available and willing, to act as an informant. A carer was defined as a non-professional who saw the patient for at least an hour most weeks.

Randomisation and masking

Potentially suitable patients were entered on a computerised screening log and, if a bed was available on the specialist unit, randomised 1:1 between the unit and standard care in a permuted block design, stratified for previous residence in a care home. Readmitted patients were assigned their original allocation. The randomisation sequence was concealed from clinical staff who allocated patients, but as recruitment took place after randomisation, research staff who collected baseline data were not blind to allocation.

Intervention and control

Regardless of allocation, patients had access to standard medical and mental health services, rehabilitation, and intermediate and social care. Physical restraints were never used.

Standard care

“Standard care” wards included five acute geriatric medical wards and six general (internal) medical wards. Practice on geriatric medical wards was based on comprehensive geriatric assessment, and staff had general experience in the management of delirium and dementia. Mental health support was provided, on request, from visiting psychiatrists on a consultation basis.

Medical and mental health unit

The 28 bed specialist unit was an acute geriatric medical ward, with five enhanced components, described in detail elsewhere15:

Specialist mental health staff were employed, including three nurses, an occupational therapist, and regular twice weekly visits from a psychiatrist. There was also additional physiotherapy, speech and language therapy, and geriatrician time. Three healthcare assistants worked as activities coordinators

Staff were trained in recognition and management of delirium and dementia and the delivery of person centered dementia care17 18 19 20 21

There was a programme of organised therapeutic and diversionary activities

The environment was made more appropriate for people with cognitive impairment

A proactive and inclusive approach to family carers was adopted.

The two consultant geriatricians on the ward had a special interest in delirium and dementia and wrote thorough discharge letters to family doctors and other community services for all patients within a week of discharge. Delirium prevention measures included careful diagnostic and drug review; attention to nutrition, hydration, vision, hearing, and re-orientation; avoidance of urinary catheters and psychotropic drugs when possible; and early mobilisation and provision of activity.18

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the number of days spent at home (or in the same care home) in the 90 days after randomisation. This composite outcome took account of death; time spent in hospital, re-admissions, inpatient rehabilitation or intermediate care; or new placement in a care home. We chose 90 days as the time frame over which the consequences of short term hospital intervention might unfold.

Secondary outcomes

We also measured a range of health status outcomes: quality of life (DEMQOL, EuroQol EQ-5D, short London handicap scale22 23 24); behavioural and psychological symptoms (neuropsychiatric inventory25), physical disability (Barthel index26), cognitive impairment (mini-mental state examination27); carer strain (carer strain index28); and carer psychological wellbeing (general health questionnaire, GHQ-1229). Carers’ satisfaction was measured on 10 dimensions of care (overall, admission, car parking, nutrition, medical management, being kept informed, dignity and respect, meeting the needs of a confused patient, discharge arrangements, timing of discharge) with Likert scales (very/mostly satisfied, mostly/very dissatisfied; items taken from an Alzheimer’s Society report on acute hospital care10). Patients’ mood and engagement on the wards were measured by direct observation in a randomly selected subsample of patients.30

Recruitment and data collection

After allocation to a ward, research staff identified patients who had been randomised and assessed them for capacity to give consent to take part in the study. Those with capacity who agreed and gave written consent were asked for permission to allow us to invite a carer to take part. Most potential participants lacked capacity, in which case a carer was asked to agree to participation. If there was no available carer, a nurse was asked to act as a “professional consultee” in accordance with English mental capacity law. We excluded patients admitted to the wards who had not been randomly allocated.

A researcher collected information through interviews with the patient, family members, or other informal or professional carers. Medical and nursing notes were scrutinised for diagnostic, drug, and functional information. Researchers were extensively trained in data collection procedures and underwent periodic co-observation.

Baseline data included social and demographic information; presenting medical problems; recent use of health services; cognitive impairment27; delirium diagnosis and severity31; physical disability before the acute illness and at admission 26; behavioural and psychological symptoms25; quality of life (EuroQol EQ-5D23); medical diagnoses (based on Charlson comorbidity index32), and drugs taken on admission.

Structured non-participant observations of the experience of care on study wards were undertaken by using dementia care mapping.30 Two trained researchers observed the care of 90 randomly subsampled participants. Observations were made every five minutes for six hours per patient. Clinical staff were not aware of which patient was being observed. Quantified mood and engagement scores, activity, noise, and staff interactions that met or disregarded patients’ emotional and psychological needs (“personal enhancers” and “personal detractors”) were recorded, according to strict definitions. Inter-rater reliability was assessed throughout the study and was satisfactory (Cohen’s κ 0.50-0.85).

One of two senior geriatricians assessed process of care on a random sample of 205 sets of case notes and recorded the presence or absence of 132 items of assessment, treatment, communication or planning. Inter-rater reliability was tested and was satisfactory (κ 0.57-0.82).

Research staff who were not involved in recruitment or collection of baseline data and who were blind to allocation carried out outcome assessments. Carers’ satisfaction with hospital care was ascertained through telephone calls one to three weeks after discharge. Health outcomes were ascertained at interview with the patient and carer at home 90 days (± 7 days) after randomisation. Routine health services records were examined for information on service use, mortality, and readmission.

Statistical analysis

We compared baseline characteristics between the two groups and used Mann-Whitney or χ2 tests to test for significance as chance was not the only possible explanation for any differences observed because of the randomisation and recruitment process. Outcome analyses were by intention to treat and compared differences between the specialist unit and standard care on primary and secondary outcomes. Stata version 11.2 was used (Statacorp, College Station, TX). “Days spent at home” is a variable with a large proportion of zeros (those who did not return home). We analysed this using both a Mann-Whitney test and also a two part model to allow adjustment for baseline covariates. The two part model estimated the effect of allocated group on the probability of returning home (with logistic regression) and the amount of time spent at home for those participants who returned home (with β regression33). Other outcomes were analysed with multiple linear, logistic, negative binomial, and Cox regression, as appropriate to the error distribution of each outcome variable. In each case, adjustment was made for prespecified prognostically important variables (age, sex, residence, cognitive impairment, activities of daily living, number of comorbidities) and variables with an imbalance between groups at baseline. We compared data on process, carers’ satisfaction, and patients’ experience using Mann-Whitney and χ2 tests.

Analysis of health status outcomes for surviving participants used multiple imputation for missing data: 50 imputed datasets were created and estimates combined across datasets with Rubin’s rules.34 35 There were no substantial differences between analyses that used imputation and those that used complete cases only.

Potentially different effects in prespecified subgroups were examined by considering interaction terms.

To calculate the sample size we used data on number of days spent at home from a previous cohort study in a similar population.3 Among 245 participants in that study, 24% did not return home after the initial admission, and days at home were negatively skewed for participants who returned home. Our calculation assumed that we would use a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test to explore the overall effect of the intervention on days at home. Three hundred participants in each group gave 80% power to detect a probability of 0.566 or more that a participant from the specialist unit would have more days at home than a participant randomised to standard care. We used simulation to explore how this translated into plausible effects of the specialist unit. It equated to an increase in the proportion of participants returning home from 76% randomised to standard care to 80% randomised to the specialist unit, plus a five day increase in median days at home for those participants returning home from the specialist unit.16

Results

Recruitment

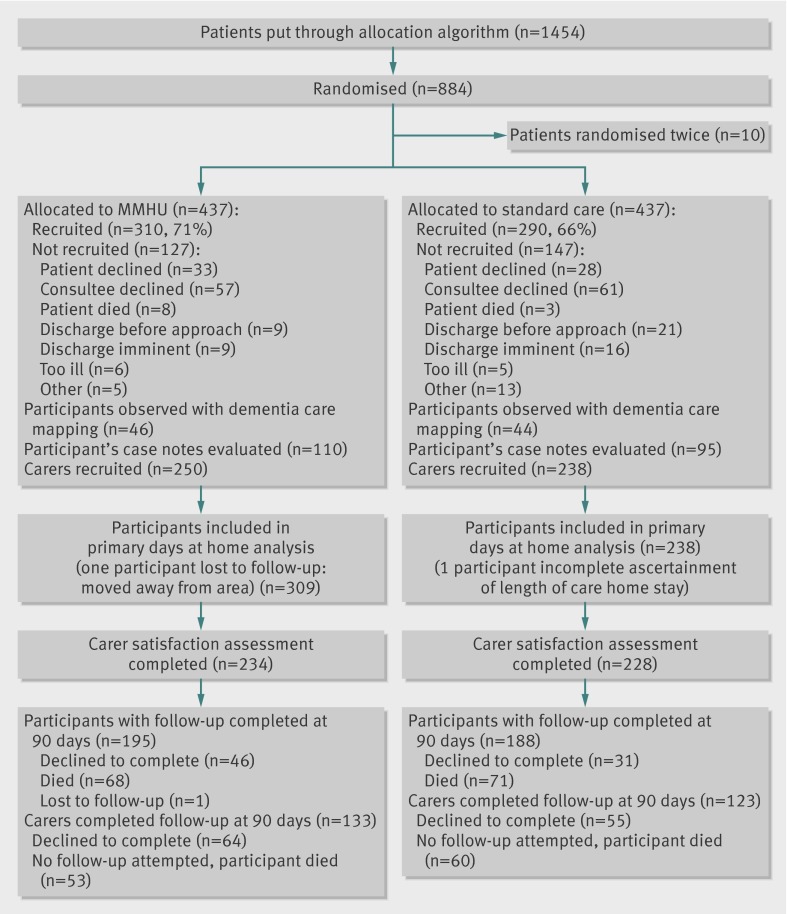

Between July 2010 and December 2011, 310 patients were recruited from the specialist unit and 290 from standard care (fig 1). One hundred and seventy four (29%) were recruited on the day of admission, 354 (59%) the following day, the rest in the next two days. Median time to transfer from the admission unit was one day (interquartile range 0-1) for both groups. Recruitment rate was slightly higher on the specialist unit (71% v 66% of those randomised). Those not recruited were of similar age, sex, and area of residence (postcode), but care home residents assigned to the specialist unit were more likely to be recruited than those assigned to standard care (73% v 56%). Four hundred and sixty two participants lacked mental capacity, 227 (73%) assigned to the specialist unit and 235 (81%) assigned to standard care. Recruitment with a professional consultee was 30 versus 31, respectively. Follow-up was completed in March 2012.

Fig 1 Flow of patients and carers in study of care of patients with cognitive impairment admitted to hospital according to randomisation to specialist medical and mental health unit (MMHU) or standard care

Baseline characteristics

Patients were old (median age 85), a quarter came from care homes, two thirds had previously diagnosed dementia, half had delirium, and behavioural and psychological symptoms were common. Groups were generally well matched, but there were imbalances at baseline in some prognostically important variables (previous residence in care home 28% v 21%, presence of delirium 53% v 62%, history of hip fracture 14% v 7%, or hemiparesis 4% v 10%; table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in older patients with cognitive impairment admitted to hospital according to randomisation to specialist medical and mental health unit (MMHU) or standard care. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Measure (with total score, if applicable) | MMHU (n=310) | Standard care (n=290) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of randomly allocated patients recruited | 71% | 66% | — |

| Median (IQR) age (years) | 85 (80-88) | 85 (80-89) | 0.80 |

| Female | 170 (55) | 142 (49) | 0.15 |

| Care home resident | 88 (28) | 60 (21) | 0.03 |

| Living alone | 119 (38) | 133 (46) | 0.06 |

| Median (IQR) cognition/30 (MMSE) | 14 (6-20) | 13 (6-19) | 0.10 |

| Median (IQR) delirium severity/46 (DRS score) | 19 (11-27) | 20 (14-27) | 0.03 |

| Categorical delirium (DRS >17.75) | 164 (53) | 181 (62) | 0.02 |

| Median (IQR) behavioural and psychological symptoms/144 (NPI) | 26 (13-42) | 25 (14-40) | 0.99 |

| Delusions | 144 (59) | 134 (57) | 0.75 |

| Hallucinations | 91 (37) | 94 (40) | 0.50 |

| Agitation | 169 (69) | 151 (64) | 0.34 |

| Depression | 147 (60) | 130 (55) | 0.18 |

| Apathy | 162 (66) | 160 (68) | 0.58 |

| Motor behaviours | 87 (35) | 89 (38) | 0.59 |

| Sleep problems | 124 (50) | 136 (57) | 0.39 |

| Appetite or feeding problems | 141 (57) | 128 (54) | 0.44 |

| Median (IQR) Barthel index before acute illness/20 | 14 (9-18) | 14 (10-18) | 0.76 |

| Median (IQR) Barthel index at admission/20 | 9 (5-13) | 8 (4-13) | 0.30 |

| Presented with fall | 129 (42) | 128 (44) | 0.53 |

| Presented with reduced mobility | 140 (45) | 135 (47) | 0.73 |

| Presented with worsening cognition | 207 (67) | 198 (68) | 0.70 |

| Vision problem | 83 (27) | 97 (34) | 0.08 |

| Hearing problem | 56 (18) | 54 (19) | 0.88 |

| Previous dementia diagnosis | 206 (67) | 183 (63) | 0.34 |

| Previous depression diagnosis | 56 (18) | 45 (16) | 0.41 |

| Previous paralysis or hemiparesis | 13 (4) | 28 (10) | 0.01 |

| Previous hip fracture | 42 (14) | 21 (7) | 0.01 |

| Median (IQR) No of comorbidities/19 | 4 (3-5) | 4 (3-6) | 0.44 |

| Hospital admission in previous year | 203 (66) | 195 (67) | 0.65 |

| Median (IQR) No of drugs | 7 (4-9) | 6 (4-9) | 0.14 |

IQR=interquartile range; MMSE=mini-mental state examination; DRS=delirium rating scale (DRS-R-98); NPI=neuropsychiatric inventory.

Process of care

The median length of the index stay was 11 days (interquartile range 5-22) in each group. Of the participants randomised to standard care, 204/290 (70%) were managed on geriatric medical wards and 86 (30%) on general medical wards. There were significant (P<0.05) differences between the specialist unit and standard care on 42/132 intervention process items, including more comprehensive assessment of mental state, function, collateral history, statement of a clear medical diagnosis, drug review, rehabilitation therapy, discussion with family carers, and referral to community rehabilitation and mental health services (table 2).

Table 2.

Selected differences between process of care on specialist medical and mental health unit (MMHU) and standard care wards from interventions recorded in medical, nursing, and multidisciplinary records. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients

| MMHU (n=110) | Standard care (n=95) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal cognitive testing* | 57 (52) | 24 (26) | <0.001 |

| Presence/absence delirium recorded | 41 (37) | 27 (28) | 0.2 |

| Collateral cognitive history | 70 (64) | 31 (33) | <0.001 |

| Collateral functional history | 89 (81) | 40 (42) | <0.001 |

| Occupational therapy assessment | 91 (83) | 35 (37) | <0.001 |

| Speech and language therapy assessment | 20 (18) | 2 (2) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatrist assessment | 21 (19) | 8 (8) | <0.001 |

| Personal profile completed† | 50 (45) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Dementia care plan | 63 (57) | 7 (7) | <0.001 |

| Clear medical diagnosis | 101 (92) | 73 (77) | 0.003 |

| Evidence of drug review | 83 (75) | 37 (39) | <0.001 |

| Antipsychotic drug use | 15 (14) | 19 (20) | 0.2 |

| One-to-one care used | 6 (5) | 2 (2) | 0.2 |

| Progress discussed with family | 95 (86) | 71 (75) | 0.03 |

| Community mental health referral | 17 (15) | 6 (6) | 0.04 |

| Intermediate care rehabilitation | 14 (13) | 5 (5) | 0.07 |

OT=occupational therapy.

*Excluding abbreviated mental test score.41

†Personal profile is document describing biography, routine, preferences, and dislikes.

Primary outcomes

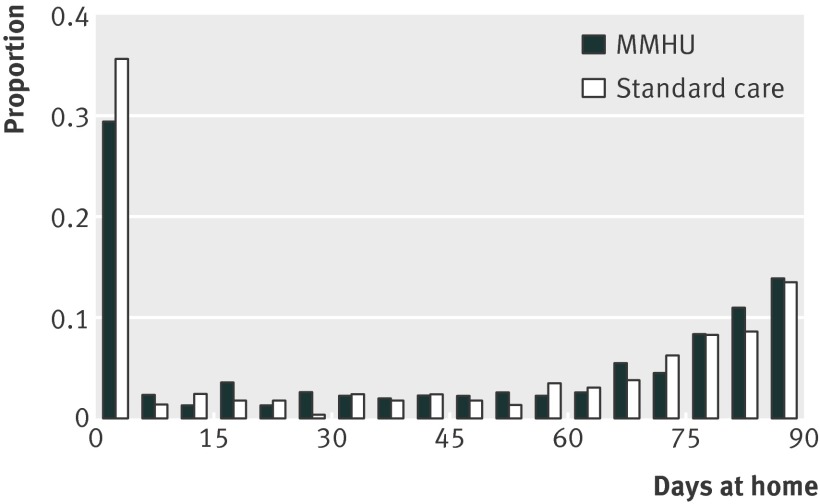

There was no significant difference in days spent at home between the specialist unit and standard care groups (median 51 v 45 days; 95% confidence interval for difference −12 to 24; P=0.3 by Mann Whitney test; P=0.7 from a likelihood ratio test using the two part model after adjustment; fig 2). Specialist unit patients were more likely to return home from hospital (74% v 70%, 95% confidence interval for difference −3% to 11%), but, for those who returned home, the number of days at home was similar (median 70.5 v 71 days, 95% confidence interval for difference −6 to 6.5). Mortality in hospital was 29 (9%) versus 22 (8%). Specialist unit patients were slightly more likely to survive to 90 days (78% v 75%, 95% confidence interval for difference −4% to 9%), less likely to move to a care home (20% v 28%, −16% to 0%), or be readmitted (32% v 35%, −10% to 5%), but none of these differences was significantly after adjustment for baseline variables (table 3).

Fig 2 Distribution of days at home after hospital admission in study of care of patients with cognitive impairment admitted to hospital according to randomisation to specialist medical and mental health unit (MMHU) or standard care

Table 3.

Days at home and hospital and care home outcomes in patients at 90 days in older patients with cognitive impairment admitted to hospital according to randomisation to specialist medical and mental health unit (MMHU) or standard care. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Outcome | MMHU (n=310) | Standard care (n=290) | Effect (95% CI), P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||

| Median (IQR) total days at home/90 days | 51 (0-79) | 45 (0-78) | 6† (−12 to 24), P=0.31 | — |

| Return home from hospital | 228 (74) | 202 (70) | 1.21‡ (0.85 to 1.73), P=0.29 | 0.88‡ (0.59 to 1.32), P=0.54 |

| Median (IQR) days spent at home if >0§ | 70.5 (40-83) | 71 (40-82) | 1.05¶ (0.85 to 1.31), P=0.64 | 0.93¶ (0.75 to 1.15), P=0.51 |

| Overall mortality | 68 (22) | 71 (25) | 0.89** (0.64 to 1.24), P=0.50 | 1.03** (0.72 to 1.45), P=0.89 |

| Median (IQR) length of index hospital stay/days | 11 (5-22) | 11 (5-20) | 1.03†† (0.88 to 1.20), P=0.71 | 1.14†† (0.99 to 1.32), P=0.08 |

| New care home placement from community | 45/222 (20) | 65/230 (28) | 0.65‡ (0.42 to 1.00), P=0.05 | 0.78‡ (0.49 to 1.24), P=0.30 |

| Readmissions | 99 (32) | 101 (35) | 0.88‡ (0.63 to 1.24), P=0.47 | 0.83‡ (0.58 to 1.19), P=0.31 |

| Median (IQR) total days in hospital | 16 (8-30) | 16 (7-30) | 1.00†† (0.87 to 1.16), P=0.96 | 1.07†† (0.93 to 1.23), P=0.32 |

IQR=interquartile range.

*Adjusted for age, sex, residence type, delirium rating scale score, Barthel Index, co-morbidities, and history of hemiparesis, or hip fracture.

†Difference in medians.

‡Odds ratio.

§Ratio for days spent at home if >0 is: days spent at home compared with days spent not at home during follow-up period.

¶Proportional change in ratio.

**Hazard ratio.

††Relative change.

Secondary outcomes

Patients randomised to the specialist unit had a significantly higher quality of hospital experience (table 4). They were more often in a positive mood or engaged (median 79% v 68%, equivalent to an additional 40 minutes per six hour observation), active (82% v 74%), or engaged in social interactions (47% v 39%) and less often in a negative mood (11% v 20%). They experienced more staff interactions that met psychological and emotional needs (“personal enhancers”). Noise levels were lower on the specialist unit, but disruptive vocalisation was more common.

Table 4.

Non-participant observer study in older patients with cognitive impairment admitted to hospital according to randomisation to specialist medical and mental health unit (MMHU) or standard care. Data are proportions (percentages) of five minute observation periods in which the feature occurred. Personal enhancers are actions that meet emotional or psychological needs, detractors are those that disregard them; numbers (medians (IQR)) are per six hour observation

| MMHU (n=46) | Standard care (n=44) | Difference in medians (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive mood or engagement | 79 | 68 | 11 (2 to 20) | 0.03 |

| Negative mood or disengaged | 11 | 20 | −9 (−13 to −2) | 0.05 |

| Active state | 82 | 74 | 8 (−2 to 16) | 0.10 |

| Social interaction | 47 | 39 | 8 (−3 to 19) | 0.06 |

| Personal enhancers | 4 (1-8) | 1 (0-3) | 3 (1 to 5) | <0.001 |

| Personal detractors | 4 (2-7) | 5.5 (3-10.5) | −1.5 (−5 to 1) | 0.08 |

| Visitors present | 38 | 23 | 15 (−28 to 44) | 0.8 |

| Any electronic or distressed noise | 79 | 92 | −13 (−17 to −7) | <0.001 |

| Disruptive vocalisation audible | 21 | 6 | 15 (1 to 23) | 0.04 |

| Electronic alarms sounding | 59 | 74 | −15 (−21 to −9) | <0.001 |

IQR=interquartile range.

Family carers of patients randomised to the specialist unit were significantly more satisfied with overall care, nutrition, dignity and respect, the needs of confused patients being met, and discharge arrangements. Most carers were very or mostly satisfied, but there was a tail of severe dissatisfaction in both groups, which was about twice as frequent in standard care (table 5). Health status outcomes, carer strain, and carers’ psychological wellbeing were no different between groups 90 days after randomisation (table 6).

Table 5.

Satisfaction in family carers of older patients with cognitive impairment admitted to hospital according to patient’s randomisation to specialist medical and mental health unit (MMHU) or standard care. Figures are numbers (percentage) of carers

| MMHU (n=234) | Standard care (n=228) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall care: | |||

| Very satisfied | 113 (48) | 86 (38) | 0.004 |

| Mostly satisfied | 101 (43) | 103 (45) | |

| Mostly unsatisfied | 9 (4) | 17 (8) | |

| Very unsatisfied | 11 (5) | 22 (10) | |

| Feeding and nutrition: | |||

| Very satisfied | 81 (35) | 64 (29) | 0.02 |

| Mostly satisfied | 116 (51) | 105 (48) | |

| Mostly unsatisfied | 19 (8) | 24 (11) | |

| Very unsatisfied | 13 (6) | 27 (12) | |

| Management of medical issues: | |||

| Very satisfied | 87 (37) | 76 (33) | 0.1 |

| Mostly satisfied | 99 (42) | 87 (38) | |

| Mostly unsatisfied | 30 (13) | 35 (15) | |

| Very unsatisfied | 18 (8) | 29 (13) | |

| How well kept informed: | |||

| Very satisfied | 76 (33) | 66 (29) | 0.2 |

| Mostly satisfied | 80 (34) | 79 (35) | |

| Mostly unsatisfied | 50 (22) | 44 (19) | |

| Very unsatisfied | 26 (11) | 37 (17) | |

| Treated with dignity and respect: | |||

| Very satisfied | 136 (58) | 117 (52) | 0.05 |

| Mostly satisfied | 83 (36) | 80 (35) | |

| Mostly unsatisfied | 7 (3) | 12 (5) | |

| Very unsatisfied | 7 (3) | 18 (8) | |

| Ward met needs of patients with confusion: | |||

| Very satisfied | 97 (42) | 64 (28) | <0.001 |

| Mostly satisfied | 98 (42) | 97 (43) | |

| Mostly unsatisfied | 25 (11) | 35 (15) | |

| Very unsatisfied | 11 (5) | 30 (13) | |

| Discharge arrangements: | |||

| Very satisfied | 78 (37) | 62 (30) | 0.005 |

| Mostly satisfied | 86 (41) | 66 (32) | |

| Mostly unsatisfied | 20 (10) | 38 (19) | |

| Very unsatisfied | 25 (12) | 39 (19) | |

| Carer adequately prepared for discharge: | |||

| Yes | 164 (79) | 141 (70) | 0.04 |

| No | 43 (21) | 60 (30) | |

| Timing of discharge: | |||

| Too soon | 35 (17) | 45 (22) | 0.42 |

| About right | 151 (73) | 139 (67) | |

| Delayed | 22 (11) | 22 (11) | |

Table 6.

Outcomes in health status, carer strain, and carers’ psychological wellbeing at 90 days for older patients with cognitive impairment admitted to hospital according to randomisation to specialist medical and mental health unit (MMHU) or standard care. Figures are means (SD) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome(with total score, if applicable) | MMHU | Standard care | Effect size (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | |||

| Median (IQR) MMSE/30† | 16 (9-22), n=163 | 16 (8-23), n=67 | 0‡ (−4 to 2), P=0.83 | — |

| Reversible cognitive impairment (improved >2 MMSE points) | 52 (32%) | 63 (38%) | 0.82§ (0.53 to 1.27), P=0.38 | 0.88§ (0.56 to 1.37), P=0.57 |

| Median (IQR) behavioural and psychological symptoms NPI/144† | 18.5 (8-31), n=154 | 17 (7-34), n=142 | 1.5¶ (−5 to 7.5), P=0.77 | — |

| Barthel index/20 | 11.6 (5.6), n=187 | 11.6 (5.7), n=184 | 0.2‡ (−0.7 to 1.2), P=0.62 | −0.1‡ (−1.1 to 0.8), P=0.78 |

| DEMQOL/108 | 83 (11.9), n=110 | 83 (13.4), n=112 | 0.7‡ (−2.8 to 4.1), P=0.71 | 0.7‡ (−2.8 to 4.1), P=0.70 |

| DEMQOL proxy/124 | 91 (16.0), n=150 | 92 (15.0), n=138 | 0.0‡ (−4.2 to 4.2), P=1.00 | −0.4‡ (−4.6 to 3.8), P=0.84 |

| EQ-5D/1.0 (self completed) | 0.59 (0.31), n=128 | 0.57 (0.31), n=123 | 0.00‡ (−0.08 to 0.08), P=0.98 | 0.00‡ (−0.09 to 0.09), P=0.96 |

| EQ-5D/1.0 (proxy completed) | 0.26 (0.31), n=129 | 0.31 (0.33), n=134 | −0.06‡ (−0.14 to 0.02), P=0.13 | −0.07‡ (−0.15 to 0.00), P=0.06 |

| London handicap/100 | 39 (19.5), n=152 | 41 (19.1), n=140 | 1.7‡ (−4.1 to 7.5), P=0.56 | 0.5‡ (−5.2 to 6.2), P=0.87 |

| Carer strain index/13 | 5.7 (3.4), n=133 | 5.8 (3.6), n=120 | 0.06‡ (−0.76 to 0.82), P=0.87 | 0.27‡ (−0.49 to1.04), P=0.48 |

| Median (IQR) carer psychological wellbeing (GHQ-12)/36 | 12.5 (9-17), n=132 | 12 (10-16), n=121 | 1.07** (0.96 to1.18), P=0.20 | 1.11** (1.0 to 1.23), P=0.05 |

IQR=interquartile range; MMSE=mini-mental state examination; NPI=neuropsychiatric inventory; EQ5D=EuroQol quality of life instrument; DEMQOL=dementia specific quality of life instrument.

*Estimates for health status outcomes from linear regression using multiply imputed data, all adjusted for age, sex, residence. In addition, Barthel index adjusted for previous Barthel index, MMSE, history of hemiparesis or hip fracture; reversible cognitive impairment adjusted for delirium rating scale score; patient DEMQOL adjusted for delirium rating scale score and EQ-5D anxiety/depression; proxy DEMQOL adjusted for baseline Barthel index, delirium rating scale score and NPI; patient completed EQ-5D adjusted for baseline EQ-5D, MMSE, and history of hemiparesis, hip fracture, eyesight problems and arthritis; London handicap scale and proxy EQ-5D adjusted for MMSE, Barthel index, NPI, history of hemiparesis, hip fracture, eyesight problems and arthritis (and baseline EQ-5D for EQ-5D); carer strain index and psychological wellbeing adjusted for baseline score, carer residence (co-resident or not, care home), participant NPI, MMSE. hemiplegia, hip fracture, and arthritis.

†Difference in medians for NPI and MMSE score at follow-up are unadjusted. P values calculated with Mann-Whitney test and 95% CI for difference in medians with bootstrapping

‡Difference in means.

§Odds ratio.

¶Difference in medians.

**Relative change.

Adverse effects

Inpatient falls were more often recorded in medical records on the specialist unit (30/110 (27%) v 17/95 (18%), 95% confidence interval for difference −2 to 20%; P=0.10).

Subgroup analyses

Results were no different for patients with delirium at baseline, those admitted from care homes, those who spent longer than five days in hospital, or if standard care geriatric and general medical wards were considered separately.

Discussion

In this comparison between older patients with cognitive impairment managed on a specialist medical and mental health unit or on standard care wards there were no significant differences in days spent at home or other health status outcomes. Patients’ experiences, however, were better, and family carers were more satisfied with care on the specialist unit.

Strengths and weaknesses

The main strengths of this study were that we tested a realistic intervention that demonstrated good practice and evaluated it in a pragmatic manner, despite the difficulties of undertaking a clinical trial in a pressurised acute medical admissions system. The main weakness was that this required compromises in trial design that could have introduced bias. The hospital had high bed occupancy: keeping beds empty on the specialist unit, or keeping patients waiting for research assessments on the admissions unit, was impossible. The design violated best practice for a randomised trial by recruiting participants after randomisation but was similar to a Zelen design.36 This led to imbalances at baseline for some prognostically important variables, which we adjusted for in the statistical analyses, resulting in differences between unadjusted and adjusted estimates of the intervention effect and the possibility of residual confounding. Collecting follow-up data was not easy for frail participants who frequently moved around the health and social care system, and we relied on proxy reports for much information. Some data were missing, and we used imputation to include all cases when possible. As the first randomised controlled trial in this specialty, the study was powered to detect relatively large effects, and we might have missed moderate sized effects. The observed difference of six extra days at home would be clinically important, as would the 8% observed absolute reduction in new care home placement. The 95% confidence intervals for the primary and many secondary outcomes are compatible with clinically worthwhile benefits. The six day difference in median days at home between the two groups was not significant because the power calculation assumed there would be a small increase in the proportion of participants returning home from the specialist unit (as observed) but also an increase in the median number of days spent at home (location shift) for those returning home (which was not observed). Multiple outcome measures are necessary in the evaluation of complex interventions as services have multiple objectives. This raises the possibility of chance associations, although the direction of differences was consistent and in the expected direction. We did not measure some potentially important outcomes, such as incident delirium. Dementia care mapping observations were unblinded, but observers followed rigid rules to minimise bias at the cost of potentially understating the extent of differences.

Context and interpretation

This is the first randomised trial of a specialist medical and mental health unit for older people.13 Slaets et al described a pseudo-randomised trial, which suggested a reduced length of hospital stay.37 Non-randomised evaluations have supported this, but evidence is limited.11 12 13 14 Other outcomes have not been systematically explored.

The specialist medical and mental health unit was an ambitious and mature intervention, taking 18 months to develop, and successfully implemented best current practice. We assumed that better recognition and management of medical and psychiatric diagnoses, prevention of delirium and other complications, improved wellbeing and communication, more timely planning, and better follow-up arrangements would reduce length of stay, readmissions, and care home placement,1 10 but the benefits we observed were modest and could have occurred by chance. Most “standard care” was on specialist older peoples’ wards delivering comprehensive geriatric assessment,38 although process measures showed that the intervention was different from control. The failure to produce marked improvements in health status outcomes was probably due to frailty and the inexorable progression of dementia and underlying diseases. Our primary outcome, days at home, was also dependent on social care, family choices, and community health services outside the control of the hospital. Mortality was high and not significantly reduced by the intervention, suggesting that many patients were reaching the end of their life, when the objectives of care focus on dignity and positive experience rather than survival and restoration of function. It can be argued that for this population experiences of care and carers’ satisfaction are outcomes of equal importance to more conventional health status,39 making our findings important and residual poor patient experience and carer dissatisfaction worthy of further attention.

Implications and future work

If the improvements in quality of experience and care we found are believed to be worth having, healthcare providers and funders are set a challenge as investment was required to achieve these improvements. A full economic analysis is required, but we found no evidence that increased staffing costs might be offset by reduction in hospital use. The intensity of intervention on the specialist medical and mental health unit was beyond that likely to be provided by older age psychiatry liaison services, which have also been promoted as resource saving,1 14 10 calling into question their ability to improve outcomes markedly or reduce costs.

The findings require replication to determine whether such units have moderate but clinically worthwhile health benefits and because the study was done in a single hospital in a country with well developed but resource constrained health and social care systems, which might not apply elsewhere. Some commentators have suggested that the whole model of acute hospital care is inappropriate for frail older people,40 but we found that most patients’ experience of hospital was positive (or at least neutral), and caregivers were satisfied with hospital care. A minority of patients in both settings, however, experienced predominantly negative mood or disengagement, had unmet psychological needs, or had carers who remained dissatisfied with care. Work is needed to understand these patients. They are likely to be those who persistently vocalise, become agitated or aggressive, are apathetic, are at high risk of falls, or are approaching the end of life. More innovative interventions are required to ensure optimal care for these patients, who are often difficult to look after.

What is already known on this topic

Half of people aged over 70 admitted to general hospital for acute medical care have delirium, dementia, or both

Mortality, readmissions, and care home placement are more common for those with cognitive impairment than for those without, and length of hospital stay is longer

Family carers often complain about the quality of care and poor patient experience

Specialist units and liaison services have been proposed to improve outcomes and reduce health and social services resource use

What this study adds

Best practice acute hospital management of older people with delirium and dementia does not improve health status or reduce use of hospital resources

The experience of patients and satisfaction of family carers, however, are improved

As many of these patients are approaching the ends of their lives, these are important outcomes

Finbarr Martin chaired the Trial Steering Committee. We thank the NIHR Mental Health Research Network, Trent Dementia Research Network and Trent Comprehensive Local Research Network for support in recruitment, especially Clare Litherland, Jo Almeida, Amy Shuttlewood, Nadia Frowd, and Becca Saunders. We thank Nikki King, Gerry Edwards, Simon Hammond, Louise Howe, Sally Howard, John Morrant, and Jonathan Waite for making the specialist medical and mental health unit work. The Medical Crises in Older People study group also included Justine Schneider, Simon Conroy, Anthony Avery, Judi Edmans, Adam Gordon, Bella Robbins, Jane Dyas, Pip Logan, Rachel Elliott, and Matt Franklin.

Contributors: Study conception and design: RH, JG, RJ, DP, SL; literature search RH, SG; intervention design and training: DP, RH, RJ, CR; trial operationalisation and management: SG, RH, PF, JG; service liaison: SG, CR, RH, RJ; recruitment, data collection: SG, CR, KW, PF; process assessment: FK, RH, JM; non-participant observer study: SG, KW, DP; statistical analysis LB, SL, SG, JM; interpretation, paper drafting: RH, SG, LB, JG. All authors contributed to editing and approved the final text. RH is guarantor.

Funding and disclaimer: This independent research was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its programme grants for applied research funding scheme (RP-PG-0407-10147) and research for patient benefit scheme (PB-PG-0110-21229). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Nottingham research ethics committee (10/H0403/16).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;347:f4132

References

- 1.Royal College of Psychiatrists. Who cares wins. RCP, 2005. www.rcpsych.ac.uk/PDF/WhoCaresWins.pdf.

- 2.Rudolph JL, Zanin NM, Jones RN, Marcantonio JL, Fong TG, Yang FM, et al. Hospitalization in community dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease: frequency and causes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1542-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg SE, Whittamore KH, Harwood RH, Bradshaw LE, Gladman JRF, Jones RG. The prevalence of mental health problems amongst older adults admitted as an emergency to a general hospital. Age Ageing 2012;41:80-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong TG, Jones RN, Marcantonio ER, Tommet D, Gross AL, Habtermariam D, et al. Adverse outcomes after hospitalisation and delirium in persons with Alzheimer disease. Ann Int Med 2012;156:848-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes J, House A. Psychiatric illness predicts poor outcome after surgery for hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. Psychol Med 2000;30:921-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sampson EL, Blanchard MR, Jones L, Tookman A, King M. Dementia in the acute hospital: prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195:61-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradshaw LE, Goldberg SE, Schneider JM, Harwood RH. Carers for older people with co-morbid cognitive impairment in general hospital: characteristics and psychological well-being. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013:28:681-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Nichols JN, Heller KS. Windows to the heart: creating an acute care dementia unit. J Palliat Med 2002;5:181-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gladman J, Porock D, Griffiths A, Clissett P, Harwood RH, Knight A, et al. Care for older people with cognitive impairment in general hospitals. NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme, 2012. www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1809-227_V01.pdf.

- 10.Alzheimer’s Society. Counting the cost. Alzheimer’s Society, 2009. www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=787.

- 11.Flaherty JH, Steele DK, Chibnall JT, Vasudevan VN, Bassil N, Vegi S. An ACE Unit with a delirium room may improve function and equalize length of stay among older delirious medical inpatients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010;65A:1387-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Wong Tin Niam DM, Geddes JA, Inderjeeth CA. Delirium unit: our experience. Australas J Ageing 2009;28:206-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George J, Adamson J, Woodford H. Joint geriatric and psychiatric wards: a review of the literature. Age Ageing 2011;40:543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes J, Montana C, Powell G, Hewison J, House A, Mason J, et al. Liaison mental health services for older people: a literature review, service mapping and in-depth evaluation of service models. National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation, 2010. www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1504-100_V01.pdf.

- 15.Harwood RH, Porock D, King N, Edwards G, Hammond S, Howe L, et al. Development of a specialist medical and mental health unit for older people in an acute general hospital. Medical Crises in Older People discussion paper series, issue 5, University of Nottingham, 2010. www.nottingham.ac.uk/mcop/documents/papers/issue5-mcop-issn2044-4230.pdf.

- 16.Harwood RH, Goldberg SE, Whittamore KH, Russell C, Gladman JR, Jones RG, et al. Evaluation of a medical and mental health unit compared with standard care for older people whose emergency admission to an acute general hospital is complicated by concurrent “confusion”: a controlled clinical trial. Trials 2011;12:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooker D. Person centred dementia care: making services better (Bradford Dementia Group Good Practice Guides). Jessica Kingsley, 2006.

- 18.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, Leo-Summers L, Acampora D, Holford TR, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med 1999;340:669-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harwood RH. Dementia for the hospital physician. Clin Med 2012;12:35-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gladman JRF, Jurgens F, Harwood RH, Goldberg S, Logan P. Better mental health in general hospitals (literature review). Medical Crises in Older People Discussion Paper series. Issue 3 September 2010. http://nottingham.ac.uk/mcop/documents/papers/issue3-mcop-issn2044-4230.pdf.

- 21.Worksafe BC. Dementia: understanding risks and preventing violence. Workers’ Compensation Board of British Columbia, 2010. www.worksafebc.com/publications/health_and_safety/by_topic/assets/pdf/bk125.pdf.

- 22.Smith SC, Lamping DL, Banerjee S, Harwood R, Foley B, Smith P, et al. Measurement of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: development of a new instrument (DEMQOL) and an evaluation of current methodology. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:1-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harwood RH, Ebrahim S. The manual of the London handicap scale. University of Nottingham, 1995.

- 25.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wade DT, Collin C. The Barthel activities of daily living index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Dis Studies 1988;10:64-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson BC. Validation of a caregiver strain index. J Gerontol 1983;38:344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg D, Williams P. A user’s guide to the general health questionnaire. NFER-NELSON, 1998.

- 30.Sloane PD, Brooker D, Cohen L, Douglass C, Edelman P, Fulton BR. Dementia care mapping as a research tool. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, Kanary K, Norton J, Jimerson N. Validation of the delirium rating scale-revised-98 comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001;13:229-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buis ML. ZOIB: Stata module to fit a zero-one inflated beta distribution by maximum likelihood. S457156. Boston College Department of Economics, 2010.

- 34.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for non-response in surveys. Wiley, 1987.

- 35.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: further update of ice, with an emphasis on categorical variables. Stata J 2009;9:466-77. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelen M. A new design for randomized clinical trials. N Engl J Med 1979;300:1242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slaets JP, Kaufmann RH, Duivenvoorden HJ, Pelemans W, Schudel WJ. A randomised trial of geriatric liaison intervention in elderly medical inpatients. Psychosom Med 1997;59:585-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellis G, Whitehead MA, Robinson D, O’Neill D, Langhorne P. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.NHS Outcomes Framework 2011/2. Department of Health, 2012.

- 40.Tadd W, Hillman A, Calnan S, Calnan M, Bayer T, Read S. Dignity in practice: an exploration of the care of older adults in acute NHS Trusts. NIHR SDO Programme report. www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_ES_08-1819-218_V01.pdf.

- 41.Hodkinson HM. Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly. Age Ageing 1972;1:233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]