Abstract

Background. Little is known about mortality of opiate users attending methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) clinics. We sought to investigate mortality and its predictors among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive MMT clients.

Methods. Records of 306 786 clients enrolled in China's MMT program from 24 March 2004 to 30 April 2011 were abstracted. Mortality rates were calculated for all HIV-positive antiretroviral treatment (ART)–naive and ART-experienced clients. Risk factors were examined using stratified proportional hazard ratios (HRs).

Results. The observed mortality rate for all clients was 11.8/1000 person-years (PY, 95% confidence interval [CI], 11.5–12.1) and 57.2/1000 PY (CI, 54.9–59.4) for HIV-positive clients (n = 18 193). An increase in average methadone doses to >75 mg/day was associated with a 24% reduction in mortality (HR = 0.76, CI, .70–.82), a 48% reduction for ART-naive HIV-positive clients (HR = 0.52, CI, .42–.65), and a 47% reduction for ART-experienced HIV-positive clients (HR = 0.53, CI, .46–.62). Among ART-experienced clients, initiation of ART when the CD4+ T-cell count was >300 cells/mm3 (HR = 0.64, CI, .43–.94) was also associated with decreased risk of death.

Conclusions. We found high mortality rates among HIV-positive MMT clients, yet decreased risk of death, with earlier ART initiation and higher methadone doses. A higher daily methadone dose was associated with reduced mortality in both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected clients, independent of ART.

Keywords: mortality, HIV, drug users, methadone maintenance treatment, China

(See the editorial commentary by Larney et al on pages 370–2.)

Initially, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS epidemic in China was confined primarily to injecting drug users (IDUs) and their sexual partner network [1]. Today, some 20 years later, both drug use and the HIV epidemic remain serious, intimately related issues in China. Some estimates place the number of drug users in China (most of them IDUs) at 3.5 million [2], the number of people living with HIV/AIDS at 780 000, and the proportion of people with HIV who were infected as a result of drug use and needle sharing at nearly one third of total HIV infections [3]. In response to this growing problem and in recognition of the mounting evidence for the safety and efficacy of methadone replacement therapy, the Chinese government implemented a National Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) program in 2004 [3–5]. The program has expanded rapidly; there are 711 clinics across mainland China that served 306 786 clients cumulatively by the end of April 2011, making it the largest single opioid-replacement treatment system in the world [6, 7].

Whether defined by reductions in the proportion of MMT clients who inject drugs, frequency with which they inject drugs, involvement in drug-related crime, heroin consumption and trade, or HIV incidence, China's MMT program appears to be working [4, 5]. Internationally, studies have shown that opiate-dependent drug users enrolled in treatment have lower mortality than those outside of treatment (14.0/1000 person-years [PY] vs 27.4/1000 PY) [8]. However, these gains may not be fully realized by HIV-positive clients [9, 10], possibly because of low coverage or adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ART). Indeed, among all patients enrolled in China's National Free ART Program (NFATP), IDUs had the lowest ART coverage and the highest mortality rate [11]. Thus, the objective of this nationwide cohort study was to characterize mortality and its predictors among HIV-positive and HIV-negative MMT clients in China and to testing the hypotheses that earlier ART initiation and higher individualized methadone dosing improve survival in this setting.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Inclusion criteria for this nationwide cohort study were the same as MMT program enrollment requirements [4]. Therefore, all clients enrolled in MMT between 24 March 2004 and 30 April 2011 were included in the analysis. Within the national program, clients were encouraged to be tested for HIV, and those who tested positive were referred to the NFATP. Methadone was administered to clients daily under the direct supervision of clinic staff. Clients paid no more than $1.50 per day, and many received their doses for free. Further details describing China's MMT program can be found elsewhere [4, 5].

Sources of Data

The National HIV/AIDS Information System is a Web-based data collection system maintained by the National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention (NCAIDS) [12]. Data used for this study were taken from 3 of its 8 subsystems: the MMT Data System, the HIV/AIDS Case Reporting System, and the ART Patient Data System. Records in each subsystem were linked using national identification numbers. Identification numbers in China are assigned at birth and remain the same throughout life. MMT clients were first identified using the MMT Data System. Information collected from the MMT system included demographic information, HIV status, self-reported baseline drug-use history, and daily methadone dosage. For HIV-positive clients, data were further supplemented from the HIV/AIDS Case Reporting System. As HIV is a notifiable disease in China, all HIV cases are reported in this system. As required by NCAIDS, all HIV-positive individuals are contacted every 6 months if asymptomatic and every 3 months if they have progressed to AIDS. CD4+ T-cell counts are initially assessed once HIV infection is evident, then measured every 6 months if <350 cells/mm3 and every 12 months if ≥350 cells/mm3. Follow-ups are performed by local center for disease control and prevention (CDC) staff, and data are recorded in this system. If eligible and engaged in ART, patient information is also reported in the ART Patient Data System.

Exposures

Enrolled MMT clients are started on methadone at a dose of <40 mg/day for an initial induction period of 1–2 weeks. After this induction period is completed, doctors may increase the dose in consultation with the client. In general, the doctor uses his/her judgment when determining the dose for a client based on the client's heroin use history, current heroin use, and/or comorbid conditions. Exposure to methadone was measured as the average daily methadone dose. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended this exposure indicator [13], and it was calculated as the sum of all methadone doses divided by the number of days treated. Discontinuation of methadone treatment for more than 30 days was defined as a treatment break. Clients were classified as HIV positive if they received a confirmatory HIV-positive test result at any point before or during MMT enrollment. Diagnosis for AIDS in HIV-positive clients was performed by trained local CDC staff in compliance with national standards [14]. The CD4+ T-cell count on the test date closest to the first methadone treatment date was recorded as the baseline value. ART exposure was categorized using an intent-to-treat approach, whereby if subjects had ever initiated ART treatment, then they were classified as ART experienced, regardless of their level of adherence or duration of treatment. ART eligibility is based on having a CD4+ T-cell count <350 cells/mm3 or a diagnosis of AIDS. The ART regimens typically used are lamivudine (3TC) plus zidovudine (ZDV, AZT) or stavudine (D4T) and nevirapine (NVP) or efavirenz (EFV) in China's methadone program.

Death Reporting and Observed Follow-up Time

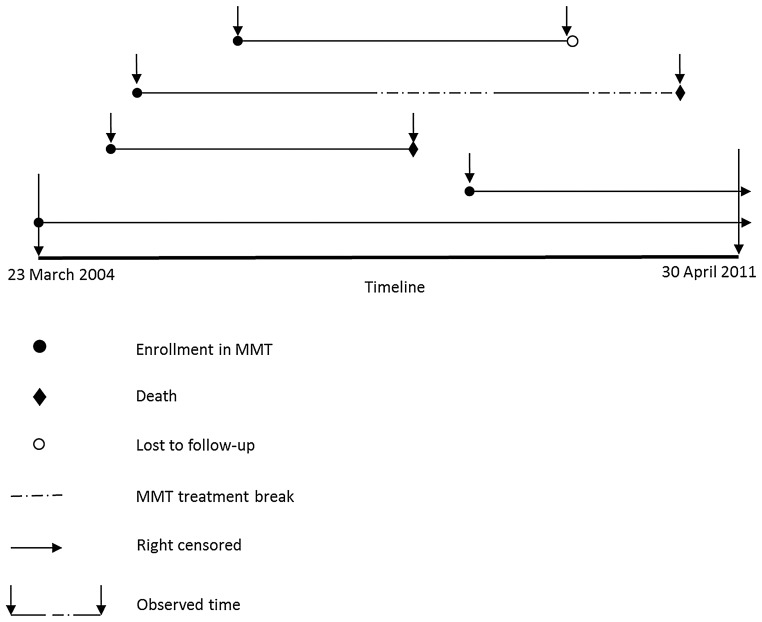

Deaths from all causes and their dates were ascertained through active follow-up by local CDC and methadone clinic staff; this is required as part of the standard of care. Deaths are recorded in each of the 3 data subsystems. The national mortality registration system was not used to independently verify deaths, causes, and dates for the present study because <10% of the nation's population is covered by the system [15]. As shown in Figure 1, clients were followed from the time of enrollment in MMT until death (failures), the end of the study period (censored observations), or the date of last contact with MMT (date of last recorded dose) or CDC staff (losses to follow-up).

Figure 1.

Diagram depicting calculation of survival time. Time is represented horizontally from study start (23 March 2004) to end (30 April 2011). For example, the third line means that a client was treated continuously before he/she died. The second line means that a client dropped out of the methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) program for a period of time (the first break in the line), reenrolled in MMT for a period of time (solid line), and then dropped out again. During the break period (no MMT treatment), the client died. Even if a client dropped out of MMT, he/she was followed so that their status (alive or dead) could be assessed during the study period. In our study, we assumed that death events could happen at any time during the study period. All clients were followed from the date of first methadone treatment until an event occurred.

Statistical Analysis

The observed (or crude) mortality rate was calculated for all eligible clients engaged in MMT and for 2 subgroups of HIV-positive clients: ART-naive and ART experienced. These 2 subgroups were separated due to differences in disease progression between ART-experienced and ART-naive HIV-positive individuals [16] and potential drug interactions between methadone and antiretroviral medicines [17, 18]. A Poisson distribution was assumed for confidence intervals (CIs) of mortality rates. Unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated by a Cox proportional hazards regression model that entered each variable one at a time. Adjusted HRs were calculated using the general multivariable Cox model stratified on covariates for which proportional hazards assumptions were not held and controlling for the remaining covariates. Variable selection of the multivariable model was based on prior knowledge rather than on statistical tests. Clients who were lost to follow-up were treated as randomly right censored in the data analysis. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld's residuals test for each covariate individually and globally. Due to missing CD4+ T-cell counts, sensitivity analyses were performed (see Supplementary Material). Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence plots were generated showing time to event for variables of interest. Log-rank tests were used to compare survival across variables of interest. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.2, SAS Institute) and R statistical package (version 2.13.0, www.r-project.org). All CIs reported are 95% CIs and all P values reported are 2 sided.

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board of NCAIDS, China CDC, reviewed and approved this study. Data used in this study were collected as a routine part of MMT and ART program administration and HIV surveillance; therefore, informed consent for inclusion of patient data in this study was not required.

RESULTS

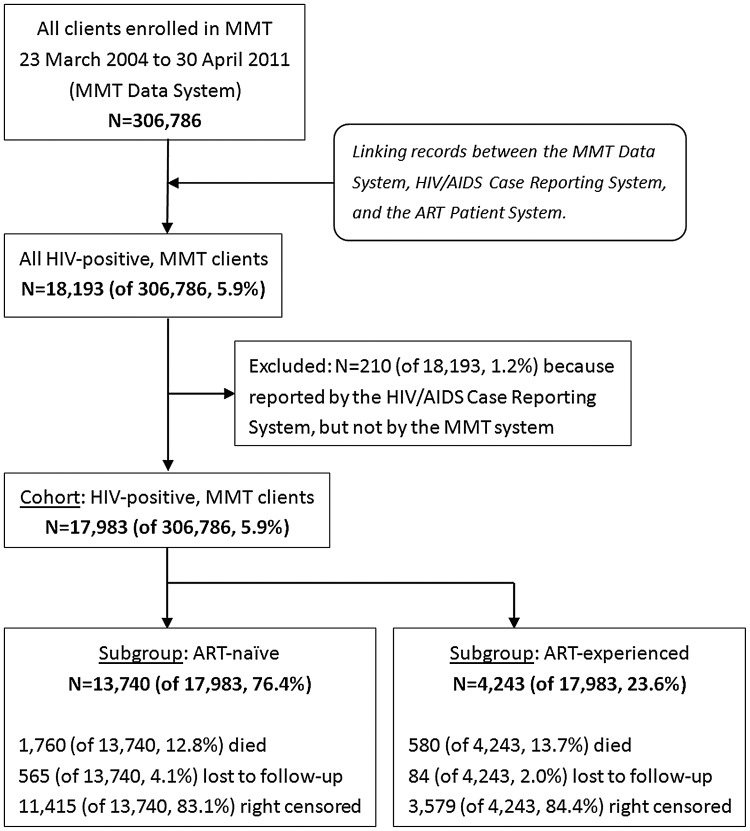

A flow chart describing the cohort is shown in Figure 2. By the end of the follow-up period, there were 306 786 drug users cumulatively enrolled in the 711 MMT clinics. The total follow-up time was 472 705 PY, during which 5573 deaths were reported for an overall mortality rate of 11.8/1000 PY (CI, 11.5–12.1). Table 1 summarizes mortality rates with unadjusted and adjusted HRs. HIV infection was the strongest overall predictor of death (HR = 7.1, CI, 6.6–7.6). Other statistically significant predictors included being male (HR = 1.3, CI, 1.2–1.4), being an ethnic minority other than Hui (HR = 1.3, CI, 1.1–1.4 for Uyghur; HR = 1.4, CI, 1.2–1.6 for Zhuang; HR = 1.4, CI, 1.3–1.6 for others), having a history of sharing needles (HR = 1.25, CI, 1.2–1.3), and having a methadone treatment break (HR = 1.8, CI, 1.7–1.9). Conversely, being married (HR = 0.84, CI, .79–.90), having a higher level of education (HR = 0.60, CI, .55–.65 for senior high or above; HR = 0.77, CI, .72–.82 for junior high), using drugs by noninjection methods (HR = 0.56, CI, .52–.61), and receiving higher methadone doses (HR = 0.72, CI, .66–.78 for >75 mg/day; HR = 0.78, CI, .74–.83 for 50–75 mg/day) were associated with decreased all-cause mortality.

Figure 2.

Flow chart describing the study cohort. All clients enrolled in the Chinese methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) program were included (n = 306 786). The final analysis included 17 983/306 786 (5.9%) human immunodeficiency virus–positive MMT clients, 13 740 (76.4%) of whom were antiretroviral therapy (ART) naive and 4243 (23.6%) were ART experienced.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 306 786 Clients in China's National MMT Program, 2004–2011

| Characteristica | Clients, N (%) | Deaths, N (%) | Observed Time, PY (%) | Mortality Rate per 1000 PY (CI)b | Unadjusted HR (CI)c | Adjusted HR (CI)c | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics at Enrollment | |||||||

| Age (y) | |||||||

| 15–30 | 82 516 (26.9) | 1223 (21.9) | 117 598.3 (24.9) | 10.4 (9.8–11.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| 31–45 | 195 425 (63.7) | 3775 (64.9) | 306 687.0 (64.9) | 12.3 (11.9–12.7) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | <.0001 |

| >45 | 25 565 (8.3) | 511 (7.6) | 35 933.8 (7.6) | 14.2 (13.0–15.5) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | <.0001 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 48 558 (15.8) | 683 (12.3) | 84 375.3 (17.8) | 8.1 (7.5–8.7) | 1 | 1 | |

| Male | 258 223 (84.2) | 4890 (87.7) | 388 317.6 (82.1) | 12.6 (12.2–12.9) | 1.6 (1.4–1.7) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | <.0001 |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Never married | 127 633 (41.6) | 2588 (46.4) | 202 441.7 (42.8) | 12.8 (12.3–13.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Married | 141 725 (46.2) | 2074 (37.2) | 212 668.2 (45.0) | 9.8 (9.3–10.2) | .77 (.73–.81) | .84 (.79–.90) | <.0001 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 36 363 (11.9) | 882 (15.8) | 56 307.6 (11.9) | 15.7 (14.6–16.7) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | <.0001 |

| Education | |||||||

| Primary school or less | 60 823 (19.8) | 1557 (27.9) | 81 516.5 (17.2) | 19.1 (18.2–20.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| Junior high | 177 540 (57.9) | 3108 (55.8) | 274 054.7 (58.0) | 11.3 (10.9–11.7) | .59 (.55–.62) | .77 (.72–.82) | <.0001 |

| Senior high or above | 67 844 (22.1) | 889 (16.0) | 116 602.8 (24.7) | 7.6 (7.1–.8.1) | .39 (.36–.42) | .60 (.55–.65) | <.0001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Han | 265 903 (86.7) | 4319 (77.5) | 416 759.4 (88.2) | 10.4 (10.1–10.7) | 1 | 1 | |

| Uyghur | 6527 (2.1) | 423 (7.6) | 10 316.0 (2.2) | 41.0 (37.1–44.9) | 3.8 (3.4–4.2) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | <.0001 |

| Zhuang | 7801 (2.5) | 220 (3.9) | 10 485.2 (2.2) | 21.0 (18.2–23.8) | 2.1 (1.8–2.4) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | <.0001 |

| Hui | 7464 (2.4) | 130 (2.3) | 11 434.4 (2.4) | 11.4 (9.4–13.3) | 1.1 (.91–1.3) | 1.1 (.89–1.3) | .4943 |

| Other | 19 091 (6.2) | 481 (8.6) | 23 710.2 (5.0) | 20.3 (18.5–22.1) | 2.0 (1.9–2.3) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | <.0001 |

| History of Drug Use at Enrollment and Participation in MMT | |||||||

| Years of drug used | |||||||

| <5 | 88 457 (28.8) | 859 (15.4) | 116 159.3 (24.6) | 7.4 (6.9–7.9) | … | … | … |

| 6–10 | 81 282 (26.5) | 1480 (26.6) | 134 747.0 (28.5) | 11.0 (10.4–11.5) | … | … | … |

| >10 | 133 409 (43.5) | 3159 (56.7) | 207 169.9 (43.8) | 15.2 (14.7–15.8) | … | … | … |

| Drug administration | |||||||

| Injection only | 178 197 (58.1) | 4365 (78.3) | 298 895.6 (63.2) | 14.6 (14.2–15.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| Noninjection | 110 097 (35.9) | 826 (14.8) | 151 752.5 (32.1) | 5.4 (5.1–5.8) | .39 (.36–.42) | .56 (.52–.61) | <.0001 |

| Both | 16 731 (5.5) | 344 (6.2) | 19 722.8 (4.2) | 17.4 (15.6–19.3) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | .0443 |

| Needle sharing | |||||||

| No | 261 747 (85.3) | 3488 (62.6) | 386 519.8 (81.8) | 9.0 (8.7–9.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 45 039 (14.7) | 2085 (37.4) | 86 185.3 (18.2) | 24.2 (23.2–25.2) | 2.6 (2.4–2.7) | 1.25 (1.2–1.3) | <.0001 |

| Average methadone dose (mg/day)e | |||||||

| <50 | 181 581 (59.2) | 3083 (55.3) | 249 878.9 (52.9) | 12.3 (11.9–12.8) | 1 | 1 | |

| 50–75 | 94 828 (30.9) | 1713 (30.7) | 166 179.7 (35.2) | 10.3 (9.8–10.8) | .83 (.78–.88) | .78 (.74–.83) | <.0001 |

| >75 | 30 377 (9.9) | 777 (13.9) | 56 646.4 (12.0) | 13.7 (12.8–14.7) | 1.1 (.99–1.2) | .72 (.66–.78) | <.0001 |

| Methadone treatment break | |||||||

| No | 179 442 (58.5) | 1527 (27.4) | 190 646.4 (40.3) | 8.0 (7.6–8.4) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 127 344 (41.5) | 4046 (72.6) | 282 058.7 (59.7) | 14.3 (13.9–14.8) | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) | <.0001 |

| HIV infection | |||||||

| No | 234 546 (76.5) | 2110 (37.9) | 385 498.0 (81.6) | 5.5 (5.2–5.7) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 18 193 (5.9) | 2386 (42.8) | 41 746.1 (8.8) | 57.2 (54.9–59.4) | 9.5 (8.9–10.0) | 7.1 (6.6–7.6) | <.0001 |

| Unknown | 54 047 (17.6) | 1077 (19.3) | 45 460.9 (9.6) | 23.7 (22.3–25.1) | 4.6 (4.3–5.0) | 4.2 (3.9–4.6) | <.0001 |

| Overall | 306 786 (100) | 5573 (100) | 472 705.1 (100) | 11.8 (11.5–12.1) | … | … | … |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HR, hazard ratio; MMT, methadone maintenance treatment; PY, person-year.

a Some categories do not total to 100% due to missing values.

b CIs were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution.

c HRs, CIs, and P values calculated using stratified multivariable Cox models with all variables included except years of drug use, which was stratified.

d Variable being stratified.

e Trend test for variable average methadone dose (mg/day), P < .0001.

A total of 18 193 (5.9%) of the 306 786 MMT clients were HIV positive. The overall mortality rate for HIV-positive clients was 57.2/1000 PY (CI, 54.9–59.4; Table 1). Of these HIV-positive MMT clients, 13 740 (75.5%) were ART naive and 4243 (23.3%) were ART experienced (Figure 2).

As summarized in Table 2, 1760 deaths were identified among the ART-naive subgroup over 30 225 PY, for a mortality rate of 58.2/1000 PY (CI, 55.5–61.0). Being older (HR = 2.2, CI, 1.7–2.8 for >45 years; HR = 1.4, CI, 1.2–1.5 for 31–45 years) and having an AIDS diagnosis (HR = 2.7, CI, 2.4–3.2) were the main predictors for increased risk of death for ART-naive clients, while higher average methadone dose was strongly protective (HR = 0.52, CI, .45–.60 for >75 mg/day; HR=0.65, CI, .58–.73 for 50–75 mg/day). Other statistically significant predictors included being male (HR = 1.2, CI, 1.0–1.4), having a history of sharing needles (HR = 1.2, CI, 1.1–1.3), having had a methadone treatment break (HR = 1.5, CI, 1.3–1.7), having an unknown baseline CD4+ T-cell count (HR = 1.4, CI, 1.2–1.7), being married (HR = 0.85, CI, .76–.95), and having a higher baseline CD4+ T-cell count (HR = 1.4, CI, 1.2–1.7 for >350 cells/mm3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 13 740 HIV-Positive ART-naive Clients in China's National MMT Program, 2004–2011

| Characteristica | Clients, N (%) | Deaths, N (%) | Observed Time, PY (%) | Mortality Rate per 1000 PY (CI)b | Unadjusted HR (CI)c | Adjusted HR (CI)c | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics at Enrollment | |||||||

| Age (y) | |||||||

| 15–30 | 4044 (29.4) | 419 (23.8) | 9601.1 (31.8) | 43.6 (39.5–47.8) | 1 | 1 | |

| 31–45 | 9058 (65.9) | 1234 (70.1) | 19694.0 (65.2) | 62.7 (59.2–66.2) | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) | 1.4 (1.2–1.5) | <.0001 |

| >45 | 552 (4.0) | 96 (5.5) | 923.6 (3.1) | 103.9 (83.2–124.7) | 2.5 (2.0–3.1) | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | <.0001 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 2087 (15.2) | 198 (11.2) | 4983.2 (16.5) | 39.7 (34.2–45.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Male | 11 653 (84.8) | 1562 (88.8) | 25241.6 (83.5) | 61.9 (58.8–65.0) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | .0104 |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Never married | 6647 (48.4) | 894 (50.8) | 15 402.6 (51.0) | 58.0 (54.2–61.8) | 1 | 1 | |

| Married | 5424 (39.5) | 619 (35.2) | 11 516.0 (38.1) | 53.8 (49.5–58.0) | .94 (.85–1.0) | .85 (.76–.95) | .0040 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 1637 (11.9) | 241 (13.7) | 3241.9 (10.7) | 74·3 (65.0–83.7) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 1.1 (.93–1.2) | .3434 |

| Education | |||||||

| Primary school or less | 4615 (33.6) | 585 (33.2) | 8611.3 (28.5) | 67.9 (62.4–73.4) | 1 | 1 | |

| Junior high | 7173 (52.2) | 973 (55.3) | 16 758.9 (55.4) | 58.1 (54.4–61.7) | .82 (.74–.91) | .83 (.74–.92) | .0004 |

| Senior high or above | 1948 (14.2) | 201 (11.4) | 4850.1 (16.0) | 41.4 (35.7–47.2) | .57 (.48–.67) | .57 (.48–.67) | <.0001 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Han | 9047 (65.8) | 1234 (70.1) | 21 008.0 (69.5) | 58.7 (55.5–62.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| Uyghur | 1959 (14.3) | 262 (14.9) | 4663.8 (15.4) | 56.2 (49.4–63.0) | .99 (.86–1.1) | 1.1 (.97–1.3) | .1339 |

| Zhuang | 600 (4.4) | 83 (4.7) | 1286.8 (4.3) | 64.5 (50.6–78.4) | 1.1 (.92–1.4) | 1.1 (.86–1.4) | .4949 |

| Hui | 344 (2.5) | 47 (2.7) | 741.5 (2.5) | 63.4 (45.3–81.5) | 1.1 (0.81–1.5) | 1.2 (.91–1.6) | .1925 |

| Other | 1790 (13.0) | 134 (7.6) | 2524.6 (8.4) | 53.1 (44.1–62.1) | .95 (.80–1.1) | 1.1 (.90–1.3) | .3520 |

| History of Drug Use at Enrollment and Participation in MMT | |||||||

| Years of drug used | |||||||

| <5 | 2009 (14.6) | 176 (10.0) | 4585.9 (15.2) | 38.4 (32.7–44.0) | … | … | … |

| 6–10 | 3175 (23.1) | 486 (27.6) | 9095.8 (30.1) | 53.4 (48.7–58.2) | … | … | … |

| >10 | 6713 (48.9) | 1086 (61.7) | 16 491.0 (54.6) | 65.9 (61.9–69.8) | … | … | … |

| Drug administration | |||||||

| Injection only | 10 700 (77.9) | 1496 (85.0) | 24 863.2 (82.3) | 60.2 (57.1–63.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Noninjection | 1755 (12.8) | 145 (8.2) | 3232.1 (10.7) | 44.9 (37.6–52.2) | .77 (.65–.92) | .86 (.72–1.0) | .0936 |

| Both | 1212 (8.8) | 114 (6.5) | 1917.7 (6.3) | 59.4 (48.5–70.4) | 1.0 (.87–1.3) | 1.1 (.94–1.4) | .1777 |

| Needle sharing | |||||||

| No | 7434 (54.1) | 831 (47.2) | 16140.0 (53.4) | 51.5 (48.0–55.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 6306 (45.9) | 929 (52.8) | 14 084.9 (46.6) | 66.0 (61.7–70.2) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | .0004 |

| Average methadone dose (mg/day)e | |||||||

| <50 | 6758 (49.2) | 1032 (58.6) | 13 831.2 (45.8) | 74.6 (70.1–79.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| 50–75 | 4602 (33.5) | 500 (28.4) | 10 530.0 (34.8) | 47.5 (43.3–51.6) | .63 (.56–.70) | .65 (.58–.73) | <.0001 |

| >75 | 2380 (17.3) | 228 (13.0) | 5863.6 (19.4) | 38.9 (33.8–43.9) | .50 (.44–.58) | .52 (.45–.60) | <.0001 |

| Methadone treatment break | |||||||

| No | 6746 (49.1) | 512 (29.1) | 12 128.1 (40.1) | 42.2 (38.6–45.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 6994 (50.9) | 1248 (70.9) | 18 096.7 (59.9) | 69.0 (65.1–72.8) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | <.0001 |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||||

| Baseline CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3) | |||||||

| <200 | 660 (4.8) | 202 (11.5) | 1361.7 (4.5) | 148.3 (127.9–168.8) | 1 | 1 | |

| 200–350 | 1284 (9.3) | 186 (10.6) | 3104.0 (10.3) | 59.9 (51.3–68.5) | .40 (.33–.49) | .63 (.51–.77) | <.0001 |

| >350 | 4580 (33.3) | 330 (18.8) | 12 163.7 (40.2) | 27.1 (24.2–30.1) | .18 (.15–.21) | .39 (.32–.48) | <.0001 |

| Unknown | 7216 (52.5) | 1042 (59.2) | 13 595.4 (45.0) | 76.6 (72.0–81.3) | .51 (.44–.60) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | .0008 |

| Time of detection of HIV infection relative to MMT enrollmentd | |||||||

| After MMT enrollment | 4618 (33.6) | 566 (32.2) | 12 201.8 (40.4) | 46.4 (42.6–50.2) | … | … | … |

| Before MMT enrollment | |||||||

| 0–5 y before | 5885 (42.8) | 1014 (57.6) | 15 253.6 (50.5) | 66.5 (62.4–70.6) | … | … | … |

| >5 y before | 1206 (8.8) | 163 (9.3) | 2416.5 (8.0) | 67.5 (57.1–77.8) | … | … | … |

| Diagnosed with AIDS | |||||||

| No | 12 229 (89.0) | 1326 (75.3) | 26 533.6 (87.8) | 50.0 (47.3–52.7) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 1511 (11.0) | 434 (24.7) | 3691.2 (12.2) | 117.6 (106.5–128.6) | 2.3 (2.1–2.6) | 2.7 (2.4–3.2) | <.0001 |

| Overall | 13 740 (100) | 1760 (100) | 30 224.8 (100) | 58.2 (55.5–61.0) | … | … | … |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HR, hazard ratio; MMT, methadone maintenance treatment; PY, person-year.

a Some categories do not total to 100% due to missing values.

b CIs were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution.

c HRs, CIs, and P values calculated using stratified multivariable Cox models with all variables included except years of drug use and time of detection of HIV infection relative to MMT enrollment, which were stratified.

d Variable being stratified.

e Trend test for variable average methadone dose (mg/day), P < .0001.

Table 3.

Characteristics of 4243 HIV-Positive, ART-Experienced Clients in China's National MMT Program, 2004–2011

| Characteristica | Clients, N (%) | Deaths, N (%) | Observed Time, PY (%) | Mortality Rate per 1000 PY (CI)b | Unadjusted HR (CI)c | Adjusted HR (CI)c | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics at Enrollment | |||||||

| Age (y) | |||||||

| 15–30 | 910 (21.4) | 114 (19.7) | 2808.4 (24.9) | 40.6 (33.1–48.0) | 1 | 1 | |

| 31–45 | 3098 (73.0) | 431 (74.3) | 8128.6 (72.0) | 53.0 (48.0–58.0) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.2 (.97–1.5) | .0832 |

| >45 | 192 (4.5) | 28 (4.8) | 356.9 (3.2) | 78.4 (49.4–107.4) | 2.1 (1.4–3.1) | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | .0218 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 609 (14.4) | 57 (9.8) | 1700.7 (15.1) | 33.5 (24.8–42.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Male | 3634 (85.6) | 523 (90.2) | 9593.2 (84.9) | 54.5 (49.8–59.2) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | .0064 |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Never married | 2021 (47.6) | 287 (49.5) | 5583.8 (49.4) | 51.4 (45.5–57.3) | 1 | 1 | |

| Married | 1673 (39.4) | 209 (36.0) | 4384.5 (38.8) | 47.7 (41.2–54.1) | .93 (.77–1.1) | .87 (.72–1.1) | .1615 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 543 (12.8) | 84 (14.5) | 1308.5 (11.6) | 64.2 (50.5–77.9) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.3 (.99–1.6) | .0595 |

| Education | |||||||

| Primary school or less | 1201 (28.3) | 150 (25.9) | 2938.2 (26.0) | 51.1 (42.9–59.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Junior high | 2397 (56.5) | 354 (61.0) | 6563.5 (58.1) | 53.9 (48.3–59.6) | 1.0 (.84–1.2) | .98 (.81–1.2) | .8557 |

| Senior high or above | 644 (15.2) | 76 (13.1) | 1788.1 (15.8) | 42.5 (32.9–52.1) | .83 (.63–1.1) | .84 (.64–1.1) | .2361 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Han | 2954 (69.6) | 415 (71.6) | 7822.9 (69.3) | 53.0 (47.9–58.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Uyghur | 484 (11.4) | 70 (12.1) | 1478.1 (13·1) | 47.4 (36.3–58.5) | .88 (.68–1.1) | .92 (.70–1.2) | .5833 |

| Zhuang | 275 (6.5) | 39 (6.7) | 709.1 (6.3) | 55.0 (37.7–72.3) | 1.1 (.76–1.5) | .89 (.64–1.3) | .5099 |

| Hui | 173 (4.1) | 19 (3.3) | 473.5 (4.2) | 40.1 (22.1–58.2) | .69 (.42–1.1) | .70 (.43–1.1) | .1499 |

| Other | 357 (8.4) | 37 (6.4) | 810.4 (7.2) | 45.7 (30.9–60.4) | .86 (.61–1.2) | .93 (.65–1.3) | .6962 |

| History of Drug Use at Enrollment and Participation in MMT | |||||||

| Years of drug used | |||||||

| <5 | 396 (9.3) | 44 (7.6) | 1147.1 (10.2) | 38.4 (27.0–49.7) | … | … | … |

| 6–10 | 974 (23.0) | 119 (20.5) | 3052.4 (27.0) | 39.0 (32.0–46.0) | … | … | … |

| >10 | 2828 (66.7) | 410 (70.7) | 7074.1 (62.6) | 58.0 (52.3–63.6) | … | … | … |

| Drug administration | |||||||

| Injection only | 3440 (81.1) | 489 (84.3) | 9507.7 (84.2) | 51.4 (46.9–56.0) | 1 | ||

| Noninjection | 521 (12.3) | 49 (8.4) | 1209.4 (10.7) | 40.5 (29.2–51.9) | .77 (.57–1.0) | .86 (.63–1.2) | .3374 |

| Both | 251 (5.9) | 37 (6.4) | 486 (4.3) | 76.1 (51.6–100.7) | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | .0203 |

| Shared needle | |||||||

| No | 1870 (44.1) | 216 (37.2) | 5107.3 (45.2) | 42.3 (36.7–47.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2373 (55.9) | 364 (62.8) | 6186.6 (54.8) | 58.8 (52.8–64.9) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | .0281 |

| Average methadone dose (mg/day)e | |||||||

| <50 | 1604 (37.8) | 271 (46.7) | 4105.2 (36.3) | 66.0 (58.2–73.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| 50–75 | 1404 (33.1) | 187 (32.2) | 3698.4 (32.7) | 50.6 (43.3–57.8) | .77 (.64–.93) | .75 (.62–.91) | .0030 |

| >75 | 1235 (29.1) | 122 (21.0) | 3490.4 (30.9) | 35.0 (28.8–41.2) | .53 (.43–.66) | .52 (.42–.65) | <.0001 |

| Methadone treatment break | |||||||

| No | 1965 (46.3) | 186 (32.1) | 4680.5 (41.4) | 39.7 (34.0–45.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2278 (53.7) | 394 (67.9) | 6613.4 (58.6) | 59.6 (53.7–65.5) | 1.5 (1.2–1.7) | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) | <.0001 |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||||

| Baseline CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3)e | |||||||

| <200 | 1510 (35.6) | 314 (54.1) | 3825.2 (33.9) | 82.1 (73.0–91.2) | 1 | 1 | |

| 200–350 | 1523 (35.9) | 178 (30.7) | 4036.0 (35.7) | 44.1 (37.6–50.6) | .53 (.44–.64) | .62 (.49–.78) | <.0001 |

| >350 | 1208 (28.5) | 88 (15.2) | 3425.7 (30.3) | 25.7 (20.3–31.1) | .30 (.24–.38) | .38 (.29–.50) | <.0001 |

| CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3) when ART initiatedf | |||||||

| <200 | 2287 (53.9) | 397 (68.4) | 5942.5 (52.6) | 66.8 (60.2–73.4) | 1 | 1 | |

| 200–300 | 1333 (31.4) | 142 (24.5) | 3665.0 (32.5) | 38.7 (32.4–45.1) | .57 (.47–.69) | .85 (.67–1.1) | .1800 |

| >300 | 566 (13.3) | 36 (6.2) | 1548.2 (13.7) | 23.3 (15.7–30.8) | .34 (.24–.49) | .64 (.43–.94) | .0233 |

| Time of detection of HIV infection relative to MMT enrollmentd | |||||||

| After MMT enrollment | 659 (15.5) | 80 (13.8) | 2385.9 (21.1) | 33.5 (26.2–40.9) | … | … | … |

| Before MMT enrollment | |||||||

| 0–5 y before | 2753 (64.9) | 389 (67.1) | 7213.7 (63.9) | 53.9 (48.6–59.3) | … | … | … |

| >5 y before | 761 (17.9) | 103 (17.8) | 1631.6 (14.4) | 63.1 (50.9–75.3) | … | … | … |

| Time of ART initiation relative to MMT enrollmentd | |||||||

| After MMT enrollment | |||||||

| >1 y after | 1450 (34.2) | 186 (32.1) | 5462.2 (48.4) | 34.1 (29.2–38.9) | … | … | … |

| ≤1 y after | 1198 (28.2) | 197 (34.0) | 3111.4 (27.5) | 63.3 (54.5–72.2) | … | … | … |

| Before MMT enrollment | |||||||

| 0–3 y before | 1539 (36.3) | 189 (32.6) | 2711.9 (24.0) | 69.7 (59.8–79.6) | … | … | … |

| >3 y before | 13 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 6.7 (0.06) | 148.5 (0–439.5) | … | … | … |

| Diagnosed with AIDS | |||||||

| Yes | 3316 (78.2) | 498 (85.9) | 8964.1 (79.4) | 55.6 (50.7–60.4) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 927 (21.8) | 82 (14.1) | 2329.9 (20.6) | 35.2 (27.6–42.8) | .63 (.50–.83) | .95 (.74–1.2) | .6602 |

| Overall | 4243 (100) | 580 (100) | 11 293.9 (100) | 51.4 (47.2–55.5) | … | … | … |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HR, hazard ratio; MMT, methadone maintenance treatment; PY, person-year.

a Some categories do not total to 100% due to missing values.

b CIs were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution.

c HRs, CIs, and P values calculated using stratified multivariable Cox models with all variables included except years of drug use, time of detection of HIV infection relative to MMT enrollment, and time of ART initiation relative to MMT enrollment, which were stratified.

d Variable being stratified.

e Trend test for variables average methadone dose (mg/day) and baseline CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3), P < .0001.

f Trend test for variable CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3) when ART initiated, P = .0641.

Among the 4243 (23.3%) ART-experienced, HIV-positive clients, 580 deaths were reported over 11 294 PY for a mortality rate of 51.4/1000 PY (CI, 47.2–55.5) (Table 3). Risk of death was lowest for clients with higher baseline CD4+ T-cell counts (HR = 0.38, CI, .29–.50 for >350 cells/mm3; HR = 0.62, CI, .49–.78 for 200–350 cells/mm3) and higher methadone doses (HR = 0.52, CI, .42–.65 for >75 mg/day; HR = 0.75, CI, .62–.91 for 50–75 mg/day). Other statistically significant predictors included higher CD4+ T-cell count when ART was initiated (HR = 0.64, CI, .43–.94), being older (HR = 1.7, CI, 1.1–2.6 for >45 years), being male (HR = 1.5, CI, 1.1–2.0), having a history of sharing needles (HR = 1.2, CI, 1.0–1.5), and having had a methadone treatment break (HR = 1.5, CI, 1.3–1.8).

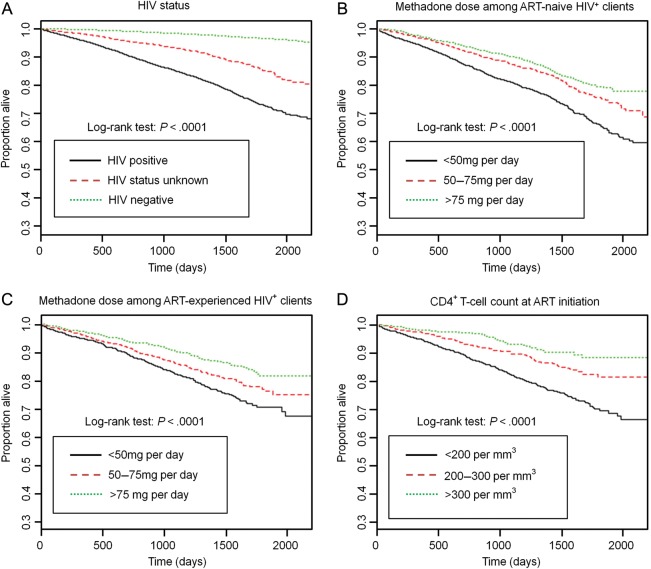

Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence plots are shown in Figure 3. Overall, HIV infection was associated with higher mortality (P < .0001). Among HIV-positive clients, higher methadone dose (P < .0001) was associated with lower cumulative mortality, independent of whether the clients were ART naive or ART experienced. Among ART-experienced, HIV-positive clients, early initial receipt of ART (ie, while CD4+ T-cell counts were higher) was also associated with lower cumulative mortality (P < .0001).

Figure 3.

Factors associated with mortality among China's methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) clients. Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence plots by human immunodeficiency virus status (A), methadone dose among antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naive clients (B), methadone dose among ART-experienced clients (C), and CD4+ T-cell count at ART initiation (D).

DISCUSSION

Although, as measured using a variety of metrics, China's national MMT program appears to be successful [4, 5], evaluations of its effect on mortality, particularly for HIV-positive clients, have not been available to date. Hence, the purpose of this study was to examine mortality and its predictors, especially among HIV-positive MMT clients, testing the hypothesis that earlier initiation of ART and higher individualized methadone dosing may decrease the risk of death.

Although we observed an overall mortality rate of 11.8/1000 PY, the mortality rate for HIV-positive clients was nearly fivefold greater, 57.2/1000 PY. These results were not unexpected, as previous studies have reported high mortality among HIV-positive MMT clients [9, 10]. Additionally, both drug users and HIV-positive individuals have far higher mortality rates than the general population [19–21]. This is almost certainly linked to the health status of clients, an idea that is supported by the strong association of mortality with lower baseline CD4+ T-cell counts and later initiation of ART—factors that are closely related and known to affect the survival of people with HIV [22–24]. Also important in this cohort was the protective effect of higher methadone doses. This has been observed in other studies, with the effect primarily attributed to increases in treatment retention and decreases in heroin overdose–related death [25]. These results suggest that both earlier initiation of ART and higher individualized dosing of methadone are crucial to reduction of the high mortality observed among HIV-positive MMT clients.

The WHO [26], the International AIDS Society USA [27], and the US Department of Health and Human Services [28] have recommended initiating ART in all patients who have a CD4+ T-cell count ≤350 cells/mm3 (irrespective of clinical symptoms) to improve health outcomes and reduce death among people living with HIV. We found mortality to be lowest among patients who began ART when their CD4+ T-cell counts were >300 cells/mm3. Unfortunately, this group of patients was relatively small in our study (13.3% of the 4243 ART-experienced clients), and the majority of ART-experienced clients (53.9%) began therapy after their CD4+ T-cell counts fell below 200 cells/mm3. Furthermore, among HIV-positive, ART-naive clients, 14.1% were in fact eligible, with baseline CD4+ T-cell counts ≤350 cells/mm3, and approximately half had never had their CD4+ T-cell counts measured.

Despite the fact that China's NFATP is 10 years old, it continues to face many barriers to fully covering all eligible patients. These include logistical obstacles related to notifying patients of their confirmed HIV-positive status and their CD4+ T-cell count results and linking them to care, including ART if eligible [29], and successfully navigating China's complex healthcare system [30]. These and other barriers such as ART treatment interruptions, ART failure (defined as HIV viral load >400 copies/mL after at least 12 months on treatment) due to active drug use, and need for clinical management of common comorbidities add to the difficulties faced by HIV-positive drug users in receiving appropriate HIV care [31]. Recent evidence suggests that many of these problems could be avoided if MMT and ART services were integrated [32].

Analysis of the 2 subgroups of HIV-positive clients resulted in similar mortality rates for ART-naive (58.2/1000 PY) and ART-experienced clients (51.4/1000 PY). While this may seem counterintuitive, we believe this is due to confounding by indication. First, ART-experienced clients are, by definition, suffering from more advanced disease because ART eligibility guidelines select patients with low CD4+ T-cell count and/or clinical symptoms. Second, coexisting heroin addiction and opioid replacement therapy and simultaneous HIV infection and antiretroviral treatment make for very complex physiological conditions. Opiates play a cofactor role in the immunopathogenesis of HIV [33], a number of antiretroviral medications are known to affect methadone plasma concentrations, and methadone is known to interact with several antiretroviral drugs [18]. Our understanding of the net effect of these interactions is limited, and more research in this area is needed.

While methadone doses ≥60 mg/day are recommended by the US National Institutes of Health [34], higher doses may be needed for clients who are receiving ART [18], clients who continue to use drugs while in MMT [35], and clients who suffer from psychological comorbidities [36]. Thus, it is probable that HIV-positive clients (whether or not they are receiving ART) may require a higher methadone dose. However, methadone dosing is complex. Providers and clients must work together to find the optimum dose based on the program's dosing guidelines, the provider's professional judgment, and the client's feedback about their experience of both the desirable (eg, withdrawal symptom suppression) and undesirable (eg, side effects) outcomes of their methadone regimen [37].

In this study, we found that an increase in average methadone doses to >75 mg/day is associated with reduced risk of all-cause mortality for HIV-positive clients by approximately 47%–48% when compared with patients whose average methadone dose is <50 mg/day, independent of other prognostic variables including ART. However, presently, nearly 60% of clients receive <50 mg/day, suggesting an urgent need for program-wide increases in individualized methadone dosing. We recognize there are many barriers to this type of change in China, including limited MMT provider and client understanding of the safety of higher doses, long-term nature of treatment goals, effective management of side effects, and need for collaborative communication between provider and client [37]. In Guangzhou, a majority of clients believed that they entered MMT for the purpose of detoxification, which could be achieved within 2–3 months and that methadone replacement is not a long-term treatment because it is regarded as harmful to one's health [38].

Our study had a number of limitations. First, as in all observational studies, the role of confounding variables must be considered. While we minimized this effect by controlling for known prognostic variables, residual confounding may persist due to factors such as coinfection with hepatitis C virus or tuberculosis that could not be controlled in our multivariate analysis. Second, clinical interventions such as provision of MMT and ART were neither randomized nor fully standardized. These interventions are implemented following complex interactions between clients and their practitioners based on general guidelines issued by China's Ministry of Health [39]. Third, it is possible that some degree of misclassification of treatment exposures occurred within our dataset. Fourth, although we identified deaths among our sample population via active follow-up by both MMT clinic and local CDC staff, mortality may be underestimated. Deaths could not be independently verified by the national mortality registration system because <10% of the nation's population is covered by the system [15]. Fifth, because we only examined all-cause mortality, some deaths may be unrelated to HIV infection or drug use. Thus, actual mortality due to HIV/AIDS may be under- or overestimated. Finally, China is a large country, and the findings reported here are general and rates for individual provinces/clinics may differ substantially. However, these differences are still likely to be influenced by access to ART and methadone-dosing practices. For example, a study from Yili prefecture in Xinjiang Autonomous Region in western China found a mortality rate among HIV-positive MMT clients of 68.9/1000 PY, but access to ART and average methadone doses were lower in Yili than in other parts of the country [40].

In summary, our results have uncovered important new findings—HIV-positive MMT clients in China have relatively high mortality rates and earlier access to ART and higher methadone doses are both associated with decreased mortality. We believe these results underscore the urgent need for expansion of ART coverage among eligible MMT clients and adoption of evidence-based, individualized methadone-dosing policies. We also suggest a potential benefit for the colocation of MMT and HIV care services in a “one-stop-shop” model. Further, we believe that the challenges China faces in improving treatment for HIV-positive heroin addicts in MMT are not unique. Rather, the results presented here may be generalized to MMT programs in other countries and should be considered evidence for the life-saving benefits of earlier initiation of ART and higher methadone doses for HIV-positive MMT clients in a broad range of settings.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the staff of the National Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program and the local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who participated in conducting this study. E. L. conceptualized the study and conducted data analysis, interpreted results, drafted the paper, and participated in revisions. K. R., L. P., X. C., C. W., and W. L. contributed to the overall design of the National MMT Program and participated in interpretation of the results. J. M. M., S. S., J. M., M. B., and R. D. contributed to the interpretation of results and development of the manuscript. Z. W. designed the National MMT Program, conceptualized the study design, supervised data analysis, interpreted results, drafted the manuscript, contributed to revisions of the manuscript, and was responsible for the final decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Z. W. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclaimers.. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Chinese National Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program (131110001050). Additional funding was provided by the Fogarty International Center and National Institute on Drug Abuse of the US National Institutes of Health (5U2RTW006918-08) and the Chinese National Science and Technology Major Research Projects on AIDS and Hepatitis (2008ZX10001-016). Funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Li Z, He X, Wang Z, et al. Tracing the origin and history of HIV-1 subtype B’ epidemic by near full-length genome analyses. AIDS. 2012;26:877–84. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328351430d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulsudjarit K. Drug problem in southeast and southwest Asia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1025:446–57. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China, Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization. Beijing, China: 2011. 2011 Estimates for the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in China. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pang L, Hao Y, Mi G, et al. Effectiveness of first eight methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China. AIDS. 2007;21:S103–7. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304704.71917.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin W, Hao Y, Sun X, et al. Scaling up the national methadone maintenance treatment program in China: achievements and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:ii29–37. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzger DS, Zhang Y. Drug treatment as HIV prevention: expanding treatment options. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:220–5. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0059-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Wang C, McGoogan JM, Rou K, Bulterys M, Wu Z. Human resources development and capacity-building during China's rapid scale-up of methadone maintenance treatment services. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:130–5. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.108951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B, et al. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction. 2011;106:32–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brugal MT, Domingo-Salvany A, Puig R, Barrio G, Garcia de Olalla P, de la Fuente L. Evaluating the impact of methadone maintenance programmes on mortality due to overdose and AIDS in a cohort of heroin users in Spain. Addiction. 2005;100:981–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimber J, Copeland L, Hickman M, et al. Survival and cessation in injecting drug users: prospective observational study of outcomes and effect of opiate substitution treatment. BMJ. 2010;341:c3172. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, et al. Effect of earlier initiation of antiretroviral treatment and increased treatment coverage on HIV-related mortality in China: a national observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:516–24. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mao Y, Wu Z, Poundstone K, et al. Development of a unified web-based national HIV/AIDS information system in China. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:ii79–89. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2010. 2009. Oslo. [Google Scholar]

- 14.General Administration of Quality Supervision Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ) of the People's Republic of China. Diagnostic criteria and principles of management of HIV/AIDS, GB16000–1995. Available at http://www.chinacdc.cn/n272442/n272530/n272967/n272997/appendix/24.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang G, Hu J, Rao KQ, Ma J, Rao C, Lopez AD. Mortality registration and surveillance in China: History, current situation and challenges. Popul Health Metr. 2005;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan D, Mahe C, Mayanja B, Okongo JM, Lubega R, Whitworth JA. HIV-1 infection in rural Africa: is there a difference in median time to AIDS and survival compared with that in industrialized countries? AIDS. 2002;16:597–603. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothwell PM. Treating individuals 2. Subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet. 2005;365:176–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruber VA, McCance-Katz EF. Methadone, buprenorphine, and street drug interactions with antiretroviral medications. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:152–60. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darke S, Zador D. Fatal heroin “overdose”: a review. Addiction. 1996;91:1765–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911217652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan OW, Johnson H, Rooney C, Seagroatt V, Griffiths C. Changes to the daily pattern of methadone-related deaths in England and Wales, 1993–2003. J Public Health (Oxf) 2006;28:318–23. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdl059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joe GW, Lehman W, Simpson DD. Addict death rates during a four-year posttreatment follow-up. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:703–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.7.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips AN, Elford J, Sabin C, Bofill M, Janossy G, Lee CA. Immunodeficiency and the risk of death in HIV infection. JAMA. 1992;268:2662–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lodwick RK, Sabin CA, et al. Study Group on Death Rates at High CD4 Count in Antiretroviral Naïve Patients. Death rates in HIV-positive antiretroviral-naive patients with CD4 count greater than 350 cells per microL in Europe and North America: a pooled cohort observational study. Lancet. 2010;376:340–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60932-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcellin F, Lacombe K, Fugon L, et al. Correlates of poor perceived health among individuals living with HIV and HBV chronic infections: a longitudinal assessment. AIDS Care. 2011;23:501–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caplehorn JR, Dalton MS, Cluff MC, Petrenas AM. Retention in methadone maintenance and heroin addicts’ risk of death. Addiction. 1994;89:203–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Cahn P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2010;304:321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. 2011. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. US Department of Health and Human Services Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, Poundstone KE, Montaner J, Wu ZY. New policies and strategies to tackle HIV/AIDS in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012;125:1331–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hougaard JL, Osterdal LP, Yu Y. The Chinese healthcare system: structure, problems and challenges. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2011;9:1–13. doi: 10.2165/11531800-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: a review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet. 2010;376:355–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60832-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uhlmann S, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, et al. Methadone maintenance therapy promotes initiation of antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. Addiction. 2010;105:907–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Zhang T, Ho WZ. Opioids and HIV/HCV infection. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011;6:477–89. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9296-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NIH Consensus Conference. National consensus development panel on effective medical treatment of opiate addiction. JAMA. 1998;280:1936–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fareed A, Casarella J, Amar R, Vayalapalli S, Drexler K. Methadone maintenance dosing guideline for opioid dependence, a literature review. J Addict Dis. 2010;29:1–14. doi: 10.1080/10550880903436010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soyka M, Kranzler HR, van den Brink W, et al. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of substance use and related disorders. Part 2: opioid dependence. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12:160–87. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.561872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin C, Detels R. A qualitative study exploring the reason for low dosage of methadone prescribed in the MMT clinics in China. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu H, Gu J, Lau JT, et al. Misconceptions toward methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) and associated factors among new MMT users in Guangzhou, China. Addict Behav. 2012;37:657–62. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hao Y, Wu Z, Sun X. AIDS Comprehensive Control and Prevention Manual. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu EW, Wang SJ, Liu Y, et al. Mortality of HIV infected clients treated with methadone maintenance treatment in Yili Kazakh autonomous prefecture. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;45:979–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.