Abstract

Objectives:

We examined the application of an ultrasound-guided combined intermediate and deep cervical plexus nerve block for regional anaesthesia in patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Methods:

A total of 19 patients receiving ultrasound-guided combined intermediate and deep cervical plexus anaesthesia followed by neck surgery were examined prospectively. The sternocleidomastoid and the levator of the scapula muscles as well as the cervical transverse processes were used as easily depicted ultrasound landmarks for the injection of local anaesthetics. Under ultrasound guidance, a needle was advanced in the fascial band between the sternocleidomastoid and the levator of the scapula muscles and 15 ml of ropivacaine 0.75% was injected. Afterwards, the needle was advanced between the levator of the scapula and the hyperechoic contour of the cervical transverse processes and a further 15 ml of ropivacaine 0.75% was injected. The sensory block of the cervical nerve plexus, the analgesic efficacy of the block within 24 h after injection and potential block-related complications were assessed.

Results:

All patients showed a complete cervical plexus nerve block. No patient required analgesics within the first 24 h after anaesthesia. Two cases of blood aspiration were recorded. No further cervical plexus block-related complications were observed.

Conclusions:

Ultrasound-guided combined intermediate and deep cervical plexus block is a feasible, effective and safe method for oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures.

Keywords: cervical plexus, interventional ultrasonography, nerve block

Introduction

To date, several investigations have been conducted to evaluate the usefulness of cervical plexus blocks (CPBs) in a variety of surgical procedures such as carotid endarterectomy, thyroid and parathyroid surgery and vocal cord surgery, as well as in pain control after herniation of the C2–C4 discs.1–5 In the past few years, novel techniques of ultrasound-guided superficial, intermediate and deep CPB have emerged, promising increased efficacy and safety in several disciplines.6–8 However, there are no reports on the application of ultrasound-guided CPB in the field of oral and maxillofacial surgery.

The cervical plexus, formed by the anterior rami of the four upper cervical spinal nerves, lies on the scalenus medius and levator anguli scapulae muscles and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and gives off both superficial and deep branches. The superficial branches provide cutaneous innervation to the head and anterolateral neck, whereas the deep branches innervate the muscles of the anterior neck, the anterior and middle scalene and the diaphragm (phrenic nerve).9

In superficial CPB, the local anaesthetic is given subcutaneously along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, whereas in intermediate CPB it is injected deep to the investing cervical fascia and superficial to the pre-vertebral fascia.10 In deep CPB, after previous identification of the transverse processes of the C2–C4 cervical vertebrae, the local anaesthetic is administered directly into the cervical paravertebral space either as one single or three separate injections.1,9 Although a deep CPB delivers better analgesia than a superficial or intermediate CPB, it is technically more demanding and may be associated with more serious complications, such as intravascular, epidural or subarachnoid injections, as well as respiratory complications related to phrenic nerve paralysis.1,11 A combined method consisting of a superficial (or intermediate) and a deep CPB can also be used to achieve an effective cervical plexus nerve block.12

The aim of this study was to examine a novel ultrasound-guided method of combined intermediate and deep CPB in patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial surgery to provide evidence regarding the implementation, efficacy and safety of this nerve block procedure.

Materials and methods

In our study, 19 patients receiving an ultrasound-guided combined intermediate and deep CPB followed by neck surgery between 2008 and 2011 were investigated after they had given informed written consent. The institutional ethics committee at the Attikon University Hospital of Athens, Greece, approved the study protocol. The cohort comprised 13 patients undergoing elective excision biopsy of neck lymph nodes, 5 patients undergoing incision and drainage for submandibular abscesses and 1 patient operated on for an internal jugular vein tumour. All patients were between the ages of 18 and 85 years, with the exclusion criterion being an allergy to local anaesthetics.

10 min before the block all patients received 0.03–0.05 mg kg–1 midazolam intravenously and were then subjected to an ultrasound-guided CPB. We used an ultrasound machine equipped with a high-resolution linear transducer. For the cervical paravertebral nerve block, two-dimensional images of the cervical region at a depth of 3–5 cm were obtained (Vivid I, GE, Waukesha, WI, and CX50, Philips Inc., Bothell, WA). After obtaining a static sonoanatomic view, the cervical transverse processes (hyperechoic formation with posterior acoustic drop out) were identified at the transverse plane. As the posterior triangle of the neck was scanned, the anatomic level of the levator of the scapula muscle below the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the fascial band between the sternocleidomastoid and the levator of the scapula muscles and the third cervical transverse process were visualized (Figures 1 and 2).6 Colour Doppler was also used to locate the vertebral vessels (Figure 3). Under ultrasound guidance (out-of-plane technique), a needle was advanced in the fascial band between the sternocleidomastoid and the levator of the scapula muscles (Figure 4a) and 15 ml of ropivacaine 0.75% was then injected. Afterwards, the needle was advanced between the levator of the scapula and the hyperechoic contour of the cervical transverse processes, and a further 15 ml of ropivacaine 0.75% was injected (Figure 4b).

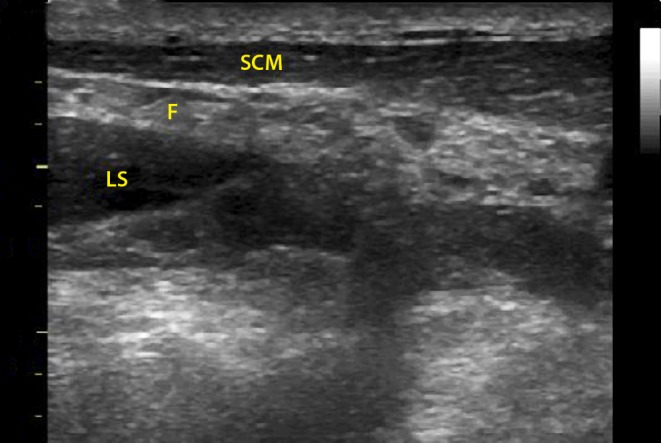

Figure 1.

The levator of the scapula muscle as it runs below the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the fascial band formed by the fusion of the investing and pre-vertebral fascia are clearly visualized with two-dimensional ultrasound imaging. F, fascial band between the levator of the scapula and sternocleidomastoid muscles; LS, levator of the scapula; SCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle

Figure 2.

The third cervical transverse process is depicted in the cervical paravertebral space. F, fascial band between the levator of the scapula and sternocleidomastoid muscles; LS, levator of the scapula; SCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle; TP, C3 cervical transverse process

Figure 3.

Colour Doppler is used for the identification of vertebral vessels. F, fascial band between the levator of the scapula and sternocleidomastoid muscles; LS, levator of the scapula; SCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle; VA, vertebral artery

Figure 4.

(a) Local anaesthetic injection in the fascial band is clearly depicted. (b) Local anaesthetic injection in the cervical paravertebral space is clearly visualized. F, fascial band between the levator of the scapula and sternocleidomastoid muscles; LA, local anaesthetic; LS, levator of the scapula; SCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle; TP, C3 cervical transverse process

All blocks were administered by a single staff anaesthetist skilled in carrying out regional anaesthesia. After block implementation, the sensory block at the surgical incision site (40 min after injection) was tested by the pinprick method using a 25 g hollow needle. The effectiveness of the block was defined either as a score of 1 (blunted sensation) or 2 (loss of sensation) compared with the unblocked contralateral anatomic area graded as 0 (normal sensation). Intraoperatively, local anaesthetic supplementation with lidocaine 2% in 1 ml increments was given by the surgeon if required. A block was considered unsuccessful if the site of surgical incision was not blocked (sensation score = 0 or 1) or an infiltration of more than 5 ml of lidocaine 2% was used intraoperatively. During the procedure all patients were monitored for potential CPB-related complications, such as dyspnoea, neurotoxicity, cardiotoxicity and positive blood aspiration. Paracetamol 1 g was given on arrival in the recovery room, and then every 8 h as standard treatment. The analgesic efficacy of the CPBs was assessed according to the patient's analgesic requirements within 24 h after injection.

Diaphragm function monitoring with a real-time sector-scanning sonographic system (2–5 MHz curved array probe) was performed only in cases where the block was executed on the right side of the neck. Ultrasound monitoring on the left side of the neck was not performed because the left diaphragm cannot be sufficiently visualized, as the stomach or part of the bowel (aerated organs) are inserted in the direction of the ultrasound beam. The probe was placed on the right anterior axillary line, in the subcostal acoustic window, so the ultrasound beam reached almost perpendicularly the posterior part of the vault of the right diaphragm. At this point a two-dimensional view of the diaphragm was obtained and a time–motion (M-mode) analysis was then utilized to display the craniocaudal displacement of the diaphragm during normal and deep inspiration before (Db) and 40 min after (Da) block performance (Figure 5a,b). Differences in the craniocaudal displacement of the right hemidiaphragm were assessed by a paired t-test and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS® statistics 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Figure 5.

Time–motion analysis of diaphragm craniocaudal displacement during (a) normal and (b) deep inspiration

Results

Our study cohort comprised 19 patients with a mean age of 62 ± 21 years and a mean weight of 57 ± 15 kg. The female-to-male ratio was 15:4. The pre-operative American Society of Anesthesiologists score was 1 or 2 for all patients.

In 11 cases, local anaesthetic injections were performed on the right side of the neck and 8 were performed on the left. The CPB proved successful in all studied patients (sensation test = 2 and no infiltration more than 5 ml of lidocaine 2% intraoperatively). During surgery, conversion to general anaesthesia was not necessary in any case. None of the patients requested analgesics within 24 h after CPB. Two cases of blood aspiration were recorded. However, no further CPB-related complications occurred during the hospital stay.

No statistically significant difference was found in the craniocaudal displacement of the right hemidiaphragm either before or after block performance in normal (Db = 2.2 ± 0.8 cm vs Da = 2.30 ± 0.65 cm; p > 0.05) and deep (Db = 4.10 ± 0.38 cm vs Da = 3.90 ± 0.55 cm; p > 0.05) inspiration, respectively.

Discussion

This study shows that combined intermediate and deep CPB guided by ultrasound to monitor anatomical needle placement and spread of local anaesthetics is feasible, effective and safe in patients undergoing surgical interventions in the oral and maxillofacial field. We observed that this nerve block was highly effective in providing regional anaesthesia in the cervical region and controlling pain intraoperatively and within the first 24 h after anaesthesia in all studied patients, with no block-related complications occurring.

In our study, imaging landmarks depicted by ultrasound were used to monitor the accurate injection of local anaesthetics in the cervical region. Although the cervical plexus nerve components were not recognized with the aid of ultrasound, clear visualization of the sternocleidomastoid and the levator of the scapula muscles, the fascial band below the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the vertebral vessels and the cervical transverse processes, as well as the space between the levator of the scapula and the cervical transverse processes was possible.6,13 A double injection technique was used, with the first injection performed in the fascia between the levator of the scapula and the sternocleidomastoid muscles and the second injection administered directly below the levator of the scapula muscle in the cervical paravertebral space. With this combined block, the high success rate and effectiveness of the regional anaesthesia might have been achieved because of entrapment of the local anaesthetics both in the cervical paravertebral space and in the fascial band between the sternocleidomastoid and the levator of the scapula muscles; hence, a direct spread of the local anaesthetics around the cervical nerve plexus at two different anatomical levels was achieved.

Deep CPB is technically demanding because the needle is advanced close to hazardous anatomical structures, such as the spinal canal and the vertebral vessels. With the conventional anatomic landmark-based technique, great care should be taken to ensure that the needle tip is not positioned within the lumen of blood vessels, especially within the vertebral artery.14 In our study, the risk of intravascular injections and local anaesthetic toxicity was significantly minimized through the use of a colour Doppler technique for the visualization of vertebral vessels. Additionally, by combining two-dimensional and colour imaging modalities, we were able to monitor the spread of local anaesthetics in relation to the large vascular structures, further minimizing the risk of accidental intravascular injections.

Over the last few years, the role of ultrasound in the head and neck region has expanded considerably. Ultrasound has been proven to be a useful, safe and cost-effective imaging modality in the diagnosis of various pathologies, such as cervical lymphadenopathy, cysts and haemangiomas. Furthermore, it is used to guide fine-needle aspiration cytology or core biopsy of neck lymph nodes in patients with suspected malignancy, thereby reducing the need for surgical diagnostic biopsy.15 In addition, ultrasound-guided procedures performed by pain physicians, anaesthetists or interventional radiologists are being increasingly used in the care of patients with chronic or acute pain.16 Recently, novel ultrasound-guided cervical plexus nerve blocks have been introduced into a variety of disciplines (e.g. carotid surgery, emergency care); there is however no relevant literature in the oral and maxillofacial fields.7,8 In a recent study, Saranteas et al17 achieved successful deep CPB in patients undergoing thyroid gland surgery using ultrasound landmarks, such as the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the pre-vertebral fascia and the cervical transverse processes identified by ultrasound. Herring et al8 reported the successful application of an ultrasound-guided superficial CPB in an emergency care unit to treat pain related to clavicle fracture and lateral neck injuries. Our study, to the best of our knowledge, reports for the first time on an ultrasound-based combined CPB in oral and maxillofacial surgery.

The findings of our study have important clinical relevance in oral and maxillofacial interventions. Currently, most of the operations in the anterolateral neck or deep cervical spaces are performed under general anaesthesia, mainly because anaesthetists are far more familiar with providing general over regional anaesthesia. However, regional anaesthesia has several advantages compared with general anaesthesia, such as better post-operative analgesia, faster recovery, lower costs, and lower morbidity and mortality rates.18 Moreover, in the last few years ultrasound imaging has become an invaluable aid for regional anaesthesia in terms of direct observation of anatomical structures, monitoring of needle positioning and spread of local anaesthetics, better and longer nerve block quality, and lower nerve block-related complications.19 In this context, our study provides new evidence that in oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures regional anaesthesia consisting of an ultrasound-guided combined CBP may be a suitable alternative whenever general anaesthesia is not indispensable or when patients are at high medical risk or unfit for general anaesthesia.

The main limitation of this study is the small sample size; however, this may be counterbalanced to some extent by the high effectiveness of the examined CPBs. Furthermore, there is still a clear need for randomized trials to compare effectiveness and complication rates between superficial, intermediate, deep and combined CPBs in oral and maxillofacial surgery.

In conclusion, this study shows that the ultrasound-guided intermediate and deep CPB is a feasible, effective and safe method of regional anaesthesia for oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures. Large-scale clinical studies should be performed in order to validate our observations.

References

- 1.Pandit JJ, Satya-Krishna R, Gration P. Superficial or deep cervical plexus block for carotid endarterectomy: a systematic review of complications. Br J Anaesth 2007; 99: 159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aunac S, Carlier M, Singelyn F, De Kock M. The analgesic efficacy of bilateral combined superficial and deep cervical plexus block administered before thyroid surgery under general anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2002; 95: 746–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pintaric TS, Hocevar M, Jereb S, Casati A, Jankovic VN. A prospective, randomized comparison between combined (deep and superficial) and superficial cervical plexus block with levobupivacaine for minimally invasive parathyroidectomy. Anesth Analg 2007; 105: 1160–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suresh S, Templeton L. Superficial cervical plexus block for vocal cord surgery in an awake pediatric patient. Anesth Analg 2004; 98: 1656–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Usui Y, Kobayashi T, Kakinuma H, Watanabe K, Kitajima T, Matsuno K. An anatomical basis for blocking of the deep cervical plexus and cervical sympathetic tract using an ultrasound-guided technique. Anesth Analg 2010; 110: 964–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saranteas T, Paraskeuopoulos T, Anagnostopoulou S, Kanellopoulos I, Mastoris M, Kostopanagiotou G. Ultrasound anatomy of the cervical paravertebral space: a preliminary study. Surg Radiol Anat 2010; 32: 617–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kefalianakis F, Koeppel T, Geldner G, Gahlen J. [Carotid-surgery in ultrasound-guided anesthesia of the regio colli lateralis]. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 2005; 40: 576–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herring AA, Stone MB, Frenkel O, Chipman A, Nagdev AD. The ultrasound-guided superficial cervical plexus block for anesthesia and analgesia in emergency care settings. Am J Emerg Med 2012; 30: 1263–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winnie AP, Ramamurthy S, Durrani Z, Radonjic R. Interscalene cervical plexus block: a single-injection technic. Anesth Analg 1975; 54: 370–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telford RJ, Stoneham MD. Correct nomenclature of superficial cervical plexus blocks. Br J Anaesth 2004; 92: 775–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carling A, Simmonds M. Complications from regional anaesthesia for carotid endarterectomy. Br J Anaesth 2000; 84: 797–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandit JJ, Bree S, Dillon P, Elcock D, McLaren ID, Crider B. A comparison of superficial versus combined (superficial and deep) cervical plexus block for carotid endarterectomy: a prospective, randomized study. Anesth Analg 2000; 91: 781–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinoli C, Bianchi S, Santacroce E, Pugliese F, Graif M, Derchi LE. Brachial plexus sonography: a technique for assessing the root level. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002; 179: 699–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies MJ, Silbert BS, Scott DA, Cook RJ, Mooney PH, Blyth C. Superficial and deep cervical plexus block for carotid artery surgery: a prospective study of 1000 blocks. Reg Anesth 1997; 22: 442–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Screaton NJ, Berman LH, Grant JW. Head and neck lymphadenopathy: evaluation with US-guided cutting-needle biopsy. Radiology 2002; 224: 75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng PW, Narouze S. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures in pain medicine: a review of anatomy, sonoanatomy, and procedures. Part I. Nonaxial structures. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 458–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saranteas T, Kostopanagiotou GG, Anagnostopoulou S, Mourouzis K, Sidiropoulou T. A simple method for blocking the deep cervical nerve plexus using an ultrasound-guided technique. Anaesth Intensive Care 2011; 39: 971–972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin J, Nicholls B. Ultrasound in regional anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2010; 65Suppl. 1:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marhofer P, Harrop-Griffiths W, Kettner SC, Kirchmair L. Fifteen years of ultrasound guidance in regional anaesthesia: part 1. Br J Anaesth 2010; 104: 538–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]