Abstract

Objective:

This prospective study evaluated the density of the midpalatal and transverse sutures as assessed by low-dose CT before rapid maxillary expansion (T0), at the end of active expansion (T1) and after a retention period of 6 months (T2).

Methods:

The study sample comprised 17 pre-pubertal subjects (mean age 11.2 years) with constricted maxillary arches. Total amount of expansion was 7 mm in all subjects. Multislice low-dose CT scans were taken at T0, T1 and T2. On the axial CT scanned images six regions of interest (ROIs) were placed along the midpalatal and transverse sutures and two in maxillary and palatal bony areas. Density was measured in Hounsfield units. Mann–Whitney U test and Friedman analysis of variance with post hoc tests were used (p < 0.05).

Results:

The three ROIs in the midpalatal suture showed a significant decrease in density from T0 to T1, a significant increase from T1 to T2 and a lack of statistically significant differences from T0 to T2. Both ROIs located in the transverse suture showed a significant decrease in density from T0 to T1, followed by a non-significant increase in density from T1 to T2.

Conclusions:

At the end of the active phase of expansion a significant reduction in density along the midpalatal and transverse sutures was observed in all subjects. The sutural density of the midpalatal suture at T2 indicated reorganization of the midpalatal suture while the density along the transverse suture increased without reaching the pre-treatment values, possibly due to different morphology between midpalatal and transverse sutures.

Keywords: maxillary suture, orthopaedic palatal expansion, rapid maxillary expansion, three-dimensional imaging

Introduction

Numerous investigations on rapid maxillary expansion (RME) have been undertaken in the last 150 years. At present, it is widely accepted that RME causes an opening of the midpalatal suture through the use of forces of large magnitude, and it produces observable changes in the maxillofacial skeleton.1–8 Experimental studies on animals revealed that skeletal remodelling associated with RME was not strictly limited to the midpalatal suture. These histological studies showed that following expansion an increased cellular activity could also be observed in the maxillary, sphenoid and nasal sutures.2,9–12

Renewed interest in the skeletal and sutural effects of RME derived from the introduction of three-dimensional (3D) radiographic techniques such as CT and cone beam CT (CBCT).13–17 By using this advanced technology it is possible to analyse in detail sutural areas involved by orthopaedic expansion in human subjects. Moreover, CT is employed to verify the relative amount and location of remodelling in the bony and sutural structures after therapy. In 1982 Timms used CT to study basal bone changes for the first time.18 More recently, other authors13–17,19–25 have used this method of investigation to evaluate skeletal, dental and periodontal effects of RME. An interesting radiographic technique has been developed in order to quantify the density of the bony and sutural structures using CT scans.26,27

The effects of orthopaedic treatment on sutures neighbouring the midpalatal suture have not been investigated yet, since most studies that employed 3D radiographic techniques focused on skeletal and dental effects in the transverse dimension. The transverse suture of the palate, for instance, has not been evaluated with regard to its possible structural changes following RME. This information could be valuable clinically with respect to the influence of the sutural conditions of the transverse suture of the palate on the effects of maxillary protraction devices (face mask) in combination with RME.

The aim of this prospective study was to investigate the changes in density of both the midpalatal and transverse sutures immediately after RME and at a post-retention observation. This study was carried out by using CT with a low-dose protocol that allows for a quantitative evaluation of bone density using Hounsfield units in selected regions of interest (ROIs).

Subjects and methods

The prospective study sample comprised 17 Caucasian subjects (7 males and 10 females) with a mean age of 11.2 years (range 8–14 years) who sought orthodontic treatment at the Department of Orthodontics of the University of Rome “Tor Vergata”. Criteria for enrolment of the subjects in the study were as follows: constricted maxillary arches, possible presence of uni- or bilateral posterior crossbite, variable degree of crowding, and one or both maxillary canines presenting with intraosseous displacement as assessed by panoramic radiographs and stages in cervical vertebral maturation as assessed on lateral cephalograms ranging from CS1 to CS3 (pre-pubertal).28 This project was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, and informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patients.

Each patient underwent a standardized protocol with RME in the form of the butterfly palatal expander, which followed the basic design of Haas.29 The expansion screw was activated at 2 turns per day (0.25 mm for each turn) for 14 days, thus reaching the total amount of screw expansion of 7 mm in all subjects. Then, the screw was tied off with a ligature wire, and the expander was kept in place as a passive retainer for 6 months.

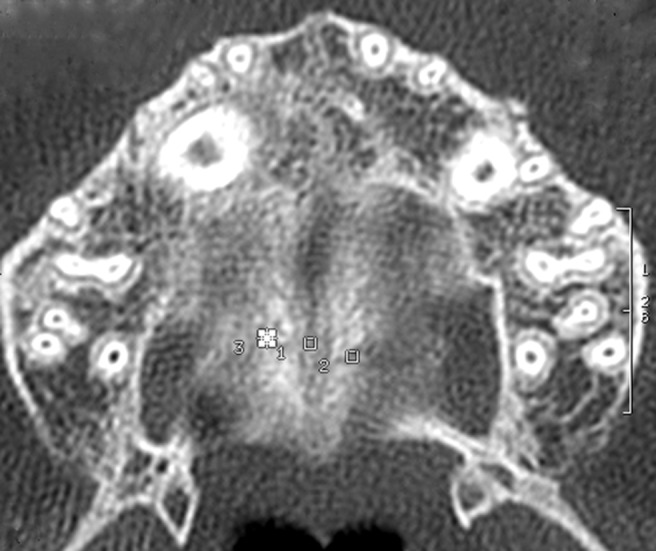

Multislice low-dose CT scans were taken before rapid palatal expansion (T0), at the end of the active expansion phase (T1) and after a retention period of 6 months (T2). The scanner used (Light-Speed 16; General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) is equipped with 16 detector rows and has a minimal rotation time of 0.5 s. The scanning technique consisted in a preliminary scout view performed in the anteroposterior (AP) and laterolateral (LL) projections, with the following acquisition parameters: 80 kV, 10 mA. The subsequent scans were taken with a 1.25 mm slice thickness, 0.6 mm interval, 11.25 mm table speed/rotation, 100 mA, 13.7 cm field of view, 512 × 512 matrix and 0° gantry angle, spiral mode, dose efficacy of 69.83 Sv, mean scan time of 9.04 s. In the low-dose CT scan protocol of 80 kV, a mean dose–length product of 43.1 mGy cm, CT dose index of 6.29 mGy and a total scan time of 19 s were obtained. Data acquisition, planning of examinations and printing of axial images and standardized multiplanar reconstructions were performed by a technologist on a workstation (Advantage Workstation; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). The radiologists had immediate access to visualization and further multiplanar and 3D reformatting on the workstation. Standardized axial CT images parallel to the palatal plane and passing through trifurcation of the right upper first molar were acquired and enlarged by 3× magnification factor with the specific software for the Light-Speed 16. On the enlarged images at three observation times (Figures 1–3) ROIs that extended to an area of 1 mm2 were placed by a single trained operator for the calculation of values of density in Hounsfield units at T0, T1 and T2. The operator was blinded to the case being measured. The ROIs in the palatal region were defined as follows (Figure 1):

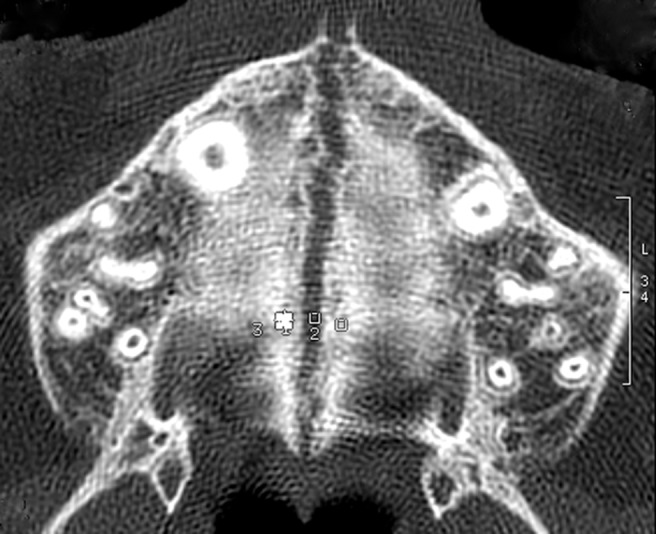

Figure 3.

Axial scans taken after a 6 month retention period, with three regions of interest on transverse suture

Figure 1.

Axial scans taken before rapid maxillary expansion, with all the eight regions of interest where density was recorded. 2D, two dimensional

Midpalatal suture anterior (MpS ant): values of density measured in the ROI located along the midpalatal suture 5 mm in front of the centre of the nasopalatine duct.

Midpalatal suture middle (MpS mid): values of density measured in the ROI located along the midpalatal suture 5 mm posterior to the centre of the nasopalatine duct.

Midpalatal suture posterior (MpS post): values of density measured in the ROI located along the midpalatal suture at the level of the second premolars.

Midpalatal/transverse suture (MpS/TS): values of density measured in the ROI located at the intersection between the midpalatal and the transverse sutures.

Transverse suture left (TS left): values of density measured in the ROI located in the transverse suture 3 mm laterally to the MpS/TS ROI (on the left side).

Transverse suture right (TS right): values of density measured in the ROI located in the transverse suture 3 mm laterally to the MpS/TS ROI (on the right side).

Maxillary bone (MB): values of density measured in the ROI located on the maxillary bone 3 mm laterally (on the left side) to the MpS mid ROI at T0.

Palatine bone (PB): values of density measured in the ROI located on the palatine bone 3 mm posterior to the TS left ROI at T0.

The last two values were used as reference values to compare the densities of the midpalatal and transverse sutures with the density of the bony palate.

Error of the method

A single operator (RL) performed all measurements at the same scanner console, and repeated all measurements after a period of 1 month. Systematic and random errors on the 8 measures repeated on the 17 subjects at all observations periods were calculated with paired t-tests and Dahlberg's formula, respectively.30 No systematic errors for any of the eight density measures at the different observation periods were detected (p > 0.05). Random errors ranged from 15 HU for the density at the MpS mid ROI at T1 to 42 HU for the density at the MpS/TS ROI at T0.

Statistical analysis

Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the density between the MpS mid ROI and the MB ROI, and between the TS left ROI and the PB ROI at T0. The differences in density at T0, T1 and T2 for the six sutural ROIs were analysed by means of analysis of variance on ranks (Kruskal–Wallis test) followed by Tukey's post hoc tests. The changes in density from T0 through T2 were contrasted by means of Friedman repeated measures analysis of variance on ranks followed by Tukey's post hoc tests. All statistical computations were performed with SigmaStat® v. 3.5 statistical software (Systat Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

The power of the study was calculated on the basis of a minimum sample size of the 17 subjects with an effect size equal to 1. The power was 0.81 at an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

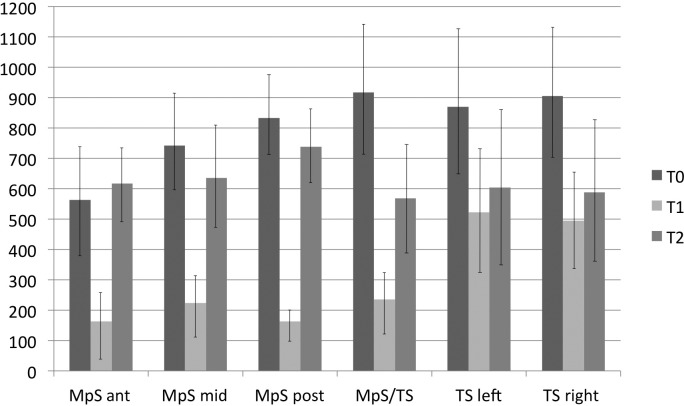

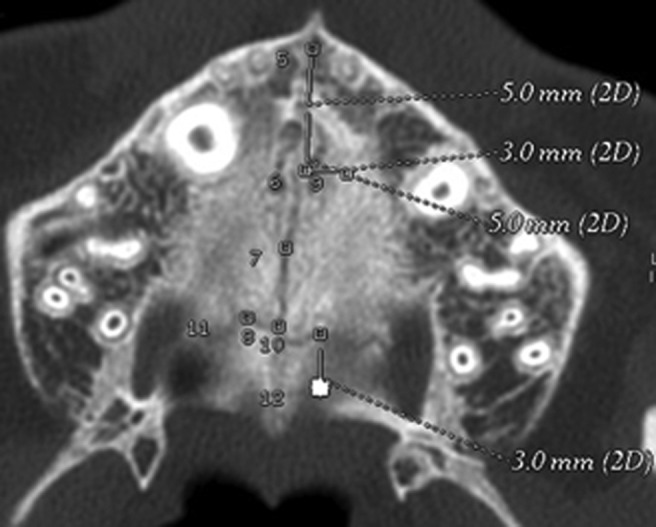

The values of density in the MpS mid ROI and the TS left ROI at T0 (741.7 ± 167.1 HU and 867.0 ± 229.1 HU, respectively) were significantly smaller than those in the MB ROI and the PB ROI at T0 (1102.8 ± 160.9 HU and 1137.5 ± 155.0 HU, respectively). Therefore, sutural density was significantly smaller than bone density at T0, thus indicating that the radiographic technique was sensitive in detecting sutural vs bony structures. The density in the MpS ant ROI was significantly smaller than all the other sutural ROIs at T0, with the exception of the MpS mid ROI (Table 1 and Figure 2). At T1 the ROIs in the midpalatal suture and at the intersection between the midpalatal and transverse sutures showed significantly smaller densities than the ROIs in the transverse suture (TS left and TS right). No significant differences in density were found between the ROIs in the midpalatal and in the transverse sutures at T2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and statistical comparisons of density in the ROIs in the midpalatal suture and in the transverse suture at each observation period (Kruskal–Wallis test with Tukey's post hoc tests), and at T0 vs T1 vs T2 within each sutural ROI (Friedman's test with Tukey's post hoc tests)

| Stage | MpS ant ROI density (HU) (1) |

MpS mid ROI density (HU) (2) |

MpS post ROI density (HU) (3) |

MpS/TS ROI density (HU) (4) |

TS left ROI density (HU) (5) |

TS right ROI density (HU) (6) |

Statistical comparisons (Kruskal–Wallis test with Tukey's post hoc tests) | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| T0 | 563.3 | 183.2 | 741.7 | 167.1 | 832.6 | 125.3 | 918.3 | 213.1 | 870.0 | 229.1 | 905.8 | 214.4 | 1 vs 3a 1 vs 4b 1 vs 5b 1 vs 6b (the other intergroup comparisons are ns) |

| T1 | 163.0 | 111.5 | 222.8 | 103.5 | 162.6 | 53.6 | 235.3 | 102.0 | 522.9 | 194.1 | 494.8 | 163.1 | 1 vs 5b 1 vs 6b 2 vs 5b 2 vs 6b 3 vs 5b 3 vs 6b 4 vs 5b 4 vs 6b (the other intergroup comparisons are ns) |

| T2 | 617.1 | 121.3 | 636.2 | 156.0 | 739.1 | 113.5 | 568.6 | 181.6 | 603.9 | 257.7 | 587.7 | 225.8 | ns |

| Statistical comparisons (Friedman's test with Tukey's post hoc tests) | T0 vs T1b | T0 vs T1b | T0 vs T1b | T0 vs T1b | T0 vs T1b | T0 vs T1b | |||||||

| T1 vs T2 b | T1 vs T2b | T1 vs T2b | T1 vs T2b | T1 vs T2 ns | T1 vs T2 ns | ||||||||

| T0 vs T2 ns | T0 vs T2 ns | T0 vs T2 ns | T0 vs T2 b | T0 vs T2 b | T0 vs T2 b | ||||||||

Ant, anterior; MpS, midpalatal suture; ns, not significant; ROI, region of interest; SD, standard deviation; TS, transverse suture.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Axial scans taken at the end of active phase, with three regions of interest on the transverse suture

The three ROIs in the midpalatal suture showed a significant decrease in density from T0 to T1, a significant increase from T1 to T2, and lack of statistically significant differences from T0 to T2. The MpS/TS ROI also exhibited a significant decrease in density from T0 to T1 followed by a significant increase from T1 to T2. In this ROI, however, the density at T2 was significantly smaller than the density at T0. Both ROIs located in the transverse suture showed a significant decrease in density from T0 to T1, and this was followed by a non-significant increase in density from T1 to T2. The values of densities at T2, therefore, were significantly smaller than those at T0 at both the TS left and TS right ROIs.

Figure 4 summarises the means and standard deviations for the six regions of interest located along sutures.

Figure 4.

Histograms representing the means and standard deviations for the six regions of interest at the three observation periods. Ant, anterior; MpS, midpalatal suture; post, posterior; T0, before rapid maxillary expansion; T1, at the end of active expansion; T2, after a retention period; TS, transverse suture

Discussion

The aim of the present prospective study was the evaluation of the effects of an orthopaedic treatment such as RME on midpalatal suture and transverse suture at the end of active phase (T1) and after a 6 month retention period (T2) by using a 3D densitometric low-dose CT protocol in pre-pubertal patients. All subjects of the sample examined in the current study needed 3D radiographic investigation to visualize the exact position of displaced canines within the maxillary arch. A low-dose spiral protocol was used, obtained by reducing the potential to the lowest possible level of 80 kV. Image quality with the lower potential remains acceptable for both quantitative measurements and the evaluation of bone quality. The dose value obtained was significantly lower than the minimum values reported in the literature, which contains numerous studies on dosimetry in dentomaxillofacial radiology, often with comparisons between conventional CT, CBCT and orthophantomography.31,32 Even when compared with the doses reported for CBCT, with the obvious approximations linked to the different dosimetric techniques, our results were comparable, and the absorbed dose measured in our study was even lower in some anatomical sites.31–33

Densitometric analysis showed that before treatment (T0) the density of both the midpalatal and transverse sutures was much smaller than the density registered in the maxillary and palatal bone. This result is in agreement with the observations on human autopsy material by Melsen in 1975, who found that in the pre-pubertal stages of postnatal development the maxillary sutures are wide, filled with connective tissue, and have high cellular activity.4 The midpalatal sagittal suture before treatment showed a gradient of increasing density from anterior to posterior (MpS ant, 563.3 HU; MpS mid, 741.7 HU; MpS post, 832.6 HU). This is due to the anatomical structure of the suture, which is wider anteriorly than posteriorly.23 Moreover, the smaller density in MpS Ant is due also to the presence of the nasopalatine duct.

After the active expansion phase (T1) a reduction in density of 70–80% was observed along the antero-posterior extension of the midpalatal suture (MpS ant, 163.0 HU; MpS mid, 222.8 HU; MpS ROI post, 162.6 HU). The orthopaedic forces of RME determined lateral displacement of the two hemi-maxillae and a drastic reduction in density.2,6

After the 6 month retention period (T2), the midpalatal suture appeared reorganized with density values similar to pre-treatment data following bone deposition along the midpalatal suture in both the anterior and posterior parts of the maxilla. The reorganization and the increased mineralization of the suture after treatment and retention would seem to produce the favourable response of reducing the amount of skeletal relapse.2,7,8

The transverse suture showed homogeneous density values before treatment (T0) (Mps/TS, 918.3 HU; TS left, 870.0 HU; TS right, 905.8 HU). At T0 the density of the transverse suture was greater than that of the midpalatal suture. This can be explained by the different anatomical characteristics, type of development and function between the two sutures.5 Melsen reported that both the midpalatal and transverse sutures change their morphology during postnatal growth, and they show fundamental morphological differences after puberty.4 In the infantile period the midpalatal suture is broad and Y shaped; it becomes more sinuous in the juvenile period, while during adolescence it is characterized by interdigitation. The transverse suture at birth is broad and slightly sinuous too; however, before puberty it develops into a typical squamous suture in which the palatine part overlaps the maxillary part.4 At the end of the active phase of palatal expansion (T1) a statistically significant reduction in density along the transverse suture was observed. This reduction in density is a consequence of the opening of the midpalatal suture after RME, as pointed out previously in experimental animals and more recently by using CBCT in the study of Leonardi et al.9–12,22 Many investigations regarding RME performed prior to maxillary protraction in patients with Class III malocclusions, thus enhancing the orthopaedic effect of the facial mask, are present in the literature.34,35 However the benefits of RME before maxillary protraction are controversial. Some authors35,36 reported greater forward and downward movement of the maxilla in patients treated with RME and facial mask while other studies37,38 showed no statistically significant differences between groups treated with facial mask with or without RME in any measured cephalometric variable. Moreover, Liou and Tsai hypothesized that, through a repetitive weekly protocol of alternate RME and constrictions, the maxilla could be protracted more effectively than with a single course of RME with stable results at 2 year follow-up.39

By using a 3D X-ray technique the present study demonstrated in a notably large group of pre-pubertal subjects not only the opening of midpalatal suture, but also an effective response to orthopaedic expansion of one of circumaxillary sutures such as the transverse suture. These findings agree with the results of Leonardi et al22, who showed a significant bony displacement by circumaxillary suture opening and a greater influence of RME on sutures that articulate directly with the maxilla when compared with those located further away. Thus the anteroposterior protraction of maxilla with devices such as the facial mask will be more effective at an early age when sutures offer less resistance, and the intervention will be more efficient after a phase of RME when the density of the sutures involved in maxillary protraction is significantly smaller than the pre-treatment value.5,40

After a 6 month retention period (T2) an increase in density along the transverse suture was found. However, the values of density at T2 were significantly smaller than the pre-treatment values at T0, possibly due to the different morphology of midpalatal and transverse sutures described in the histological investigations of Melsen4,5 and to the type of retention. The expander kept in place as a passive retainer avoided the skeletal relapse on the horizontal plane, maintaining the two halves of the maxilla separately, while there was no direct control on the transverse suture.

Conclusions

In pre-pubertal subjects both the midpalatal and transverse sutures are clearly evident on low-dose CT scans, and they present with lower values of density than the maxillary and palatine bones.

At the end of the active phase of expansion a significant reduction in density along the midpalatal and transverse sutures was observed in all subjects. RME is an orthopaedic procedure that opens the midpalatal suture with a direct effect also on other circumaxillary sutures such as the transverse suture.

6 months of retention with the RME as a passive retainer allowed the recovery of midpalatal suture that showed post-treatment values in density similar to pre-treatment values.

At the end of the 6 month retention period the density along transverse suture increased without reaching the pre-treatment values, possibly due to different morphology between midpalatal and transverse sutures, and to the type of retention.

References

- 1.Cameron CG, Franchi L, Baccetti T, McNamara JA., Jr Long-term effects of rapid maxillary expansion: A posteroanterior cephalometric evaluation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2002; 121: 129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas AJ. Rapid expansion of the maxillary dental arch and nasal cavity by opening the midpalatal suture. Angle Orthod 1961; 31: 73–90 [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNamara JA. Maxillary transverse deficiency. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000; 117: 567–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melsen B. Palatal growth studied on human autopsy material. A histologic microradiographic study. Am J Orthod 1975; 68: 42–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melsen B, Melsen F. The postnatal development of the palatomaxillary region studied on human autopsy material. Am J Orthod 1982; 82: 329–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wertz RA. Skeletal and dental changes accompanying rapid mid-palatal suture opening. Am J Orthod 1970; 58: 41–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagravere MO, Major PW, Flores-Mir C. Long-term skeletal changes with rapid maxillary expansion: a systematic review. Angle Orthod 2005; 75: 1046–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagravere MO, Major PW, Flores-Mir C. Long-term dental arch changes after rapid maxillary expansion treatment: a systematic review. Angle Orthod 2005; 75: 155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleall JF, Bayne DI, Posen JM, Subtelny JD. Expansion of the midpalatal suture in the monkey. Angle Orthod 1965; 35: 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner GE, Kronman JH. Cranioskeletal displacements caused by rapid palatal expansion in the rhesus monkey. Am J Orthod 1971; 59: 146–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffer LF, Walters RD. Adaptive changes in the face of the macaca mulatta monkey following orthopedic opening of the midpalatal suture. Angle Orthod 1975; 45: 282–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starnbach H, Bayne D, Cleall JF, Subtelny JD. Facioskeletal and dental changes resulting from rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod 1966; 36: 152–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Rossi M, De Rossi A, Abrao J. Skeletal alterations associated with the use of bonded rapid maxillary expansion appliance. Braz Dent J 2011; 22: 334–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghoneima A, Abdel-Fattah E, Hartsfield J, El-Bedwehi A, Kamel A, Kula K. Effects of rapid maxillary expansion on the cranial and circummaxillary sutures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011; 140: 510–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weissheimer A, de Menezes LM, Mezomo M, Dias DM, Santayana de Lima EM, Deon Rizzatto SM. Am J Orthdo Dentofacial Orthop 2011; 140: 366–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kartalian A, Gohl E, Adamian M, Enciso R. Cone-beam computerized tomography evaluation of the maxillary dentoskeletal complex after rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010; 138: 486–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christie KF, Boucher N, Chung C-H Effects of bonded rapid palatal expansion on the transverse dimensions of the maxilla: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2010; 137: S79–S85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timms DJ, Preston CB, Daly PF. A computed tomographic assessment of maxillary induced by rapid expansion: a pilot study. Eur J Orthod 1982; 4: 123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballanti F, Lione R, Fanucci E, Franchi L, Baccetti T, Cozza P. Immediate and post-retention effects of rapid maxillary expansion investigated by computed tomography in growing patients. Angle Orthod 2009; 79: 24–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.da Silva Filho OG, Lara TS, da Silva HC, Bertoz FA. Post expansion evaluation of the midpalatal suture in children submitted to rapid palatal expansion: a CT study. J Clin Pediatric Dent 2006; 31: 142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garib DG, Henriques JFC, Janson G, Freitas MR, Coehlo MA. Rapid maxillary expansion-tooth tissue-borne versus tooth-borne expanders: a computed tomography evaluation of dentoskeletal effects. Angle Orthod 2005; 75: 548–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leonardi R, Sicurezza E, Cutrera A, Barbato E. Early post-treatment changes of circumaxillary sutures in young patients treated with rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod 2011; 81: 38–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lione R, Ballanti F, Franchi L, Baccetti T, Fanucci E, Cozza P. Treatment and post-treatment skeletal effects of RME investigated by low-dose TC in growing subjects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008; 134: 389–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podesser B, Williams S, Crismani AG, Bantleon HP. Evaluation of the effects of rapid maxillary expansion in growing children using computer tomography scanning: a pilot study. Eur J Orthod 207; 29: 37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rungcharassaeng K, Caruso JM, Kan JYK, Kim J, Taylor G. Factors affecting buccal bone changes of maxillary posterior teeth after rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007; 132: 428.e1–428.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inoue H. Radiographic observation of rapid expansion of human maxilla. Bull Tokyo Med Dent Univ 1970; 17: 219–229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shapurian T, Damoulis PD, Reiser GM, Griffin TJ, Rand WM. Quantitative evaluation of bone density using the Hounsfield index. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Impl 2006; 21: 290–297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara JA. The cervical vertebrae maturation (CVM) method for the assessment of optimal treatment timing in dentofacial orthopedics. Sem Orthod 2005; 11: 119–129 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cozza P, Giancotti A, Petrosino A. Rapid palatal expansion in mixed dentition using a modified expander: a cephalometric investigation. J Clinical Orthod 2001; 28: 129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houston WJ. The analysis of error in orthodontic measurements. Am J Orthod 1983; 83: 382–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lecomber AR, Yoneyama Y, Lovelock DJ. Comparison of patient dose from imaging protocols for dental implant planning using conventional radiography and computed tomography. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol 2001; 30: 255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludlow JB, Davies-Ludlow LE, Brooks SL. Dosimetry of two extraoral direct digital imaging devices: NewTom cone beam CT and Orthophos Plus DS panoramic unit. Dent Maxillofac Radiol 2003; 32: 229–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huda W, Sandison GA. Estimation of mean organ doses in diagnostic radiology from Rando phantom measurements. Health Phys 1984; 47: 463–467 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turley PK. Orthopedic correction of Class III malocclusion with palatal expansion and custom protraction headgear. J Clin Orthod 1988; 22: 314–325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ngan PW, Hagg U, Yiu C, Wei SH. Treatment response and longterm dentofacial adaptations to maxillary expansion and protraction. Semin Orthod 1997; 3: 255–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baik HS. Clinical results of the maxillary protraction in Korean children. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1995; 108: 583–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaughn GA, Mason B, Moon HB, Turley PK. The effects of maxillary protraction therapy with or without rapid palatal expansion: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005; 128: 299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tortop T, Keykubat A, Yuksel S. Facemask therapy with and without expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007; 132: 467–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liou EJ, Tsai WC. A new protocol for maxillary protraction in cleft patients: repetitive weekly protocol of alternate rapid maxillary expansions and constrictions. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2005; 42: 121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franchi L, Baccetti T, McNamara JA. Postpubertal assessment of treatment timing for maxillary expansion and protraction therapy followed by fixed appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004; 126: 555–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]