Abstract

Background

Older people are at increased risk of falls after hospital discharge. This study aimed to describe the circumstances of falls in the six months after hospital discharge and to identify factors associated with the time and location of these falls.

Methods

Participants in this randomized controlled study comprised fallers (n = 138) who were part of a prospective observational cohort (n = 343) nested within a randomized controlled trial (n = 1206). The study tested patient education on falls prevention in hospital compared with usual care in older patients who were discharged from hospital and followed for six months after hospital discharge. The outcome measures were number of falls, falls-related injuries, and the circumstances of the falls, measured by use of a diary and a monthly telephone call to each participant.

Results

Participants (mean age 80.3 ± 8.7 years) reported 276 falls, of which 150 (54.3%) were injurious. Of the 255 falls for which there were data available about circumstances, 190 (74.5%) occurred indoors and 65 (25.5%) occurred in the external home environment or wider community. The most frequent time reported for falls was the morning (between 6 am and 10 am) when 79 (28.6%) falls, including 49 (32.7%) injurious falls, occurred. The most frequently reported location for falls (n = 80, 29.0%), including injurious falls (n = 42, 28.0%), was the bedroom. Factors associated with falling in the bedroom included requiring assistance with activities of daily living (adjusted odds ratio 2.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.57–5.60, P = 0.001) and falling in hospital prior to discharge (adjusted odds ratio 2.32, 95% CI 1.21–4.45, P = 0.01). Fallers requiring assistance with activities of daily living were significantly less likely to fall outside (adjusted odds ratio 0.28, 95% CI 0.12–0.69, P = 0.005).

Conclusion

Older patients who have been recently discharged from hospital and receive assistance with activities of daily living are at high risk of injurious falls indoors, most often in the bedroom. These data suggest that targeted interventions may be needed to reduce falls in this population.

Keywords: falls, patient discharge, environment, activities of daily living, accident prevention

Introduction

Falls rates in older people recently discharged from hospital are higher compared with general community-dwelling populations.1–5 Up to 40% of patients fall in the six months after discharge and up to 15% of unplanned hospital readmissions during this period are due to a fall.1,2 Falls after discharge are also more likely to result in physical injury compared with the general community-dwelling population,1,2,6 and there is an increased risk of hip fracture in the post-discharge period.7 Requiring assistance with activities of daily living (ADL), using a walking aid, and a history of falling either in hospital or prior to admission are associated with injurious post-discharge falls.1,2

There are high levels of evidence to recommend effective interventions for falls prevention, including exercise and home safety programs, for community-dwelling older people.8 However, few of the studies included in a recent systematic review of interventions for falls prevention have specifically evaluated reducing falls in the post-discharge period.8 A randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in a hip fracture population demonstrated that an exercise training program that was provided in hospital to be completed after discharge reduced subsequent falls in the home.9 Home visit interventions that include personalized environmental assessment by a trained health professional and targeted modifications to the physical environment have been shown to be effective in reducing falls after discharge among frail older people and older people with a history of falls in the previous year.10–13 These studies were not able to determine the effect of the interventions on fall-related injuries, and it is also not known which component of home visit interventions (ie, the training and advice provided by the health professional, the environmental hazard reduction, or an interaction of both) is the most effective.8,10,14 Studies have also found no significant difference between rates of falls that occur indoors compared with outside where a home environment modification intervention could not have influenced the outcome.11,13 Variable levels of adherence with suggested home modifications by participants also make it difficult to determine the mechanisms of these interventions in reducing falls.15

Given that there is limited evidence for reducing falls after discharge, data describing the circumstances of falls and falls-related injuries, specifically in the period after hospital discharge, would enable researchers to investigate how to design and target interventions for preventing falls in this population more effectively.

Therefore, this study aimed to describe the circumstances of falls and falls-related injuries that occur in older patients in the six months after hospital discharge and identify factors associated with the time and location of falls during this period.

Materials and methods

Design

The study collected data about circumstances of falls from fallers (n = 138) who were part of a prospective observational cohort (n = 343)1 nested within an RCT (n = 1206).16 The RCT tested patient education on falls prevention in hospital compared with usual care and the prospective observational study (n = 343) followed older patients for six months after hospital discharge. The post hoc analyses utilized the observational data collected from participants to answer the research question. The study was approved by the local hospital ethics committee and The University of Queensland medical research ethics committee. The original RCT was registered with the Australian Clinical Trials registry (ACTRN12608000015347).

Participants and setting

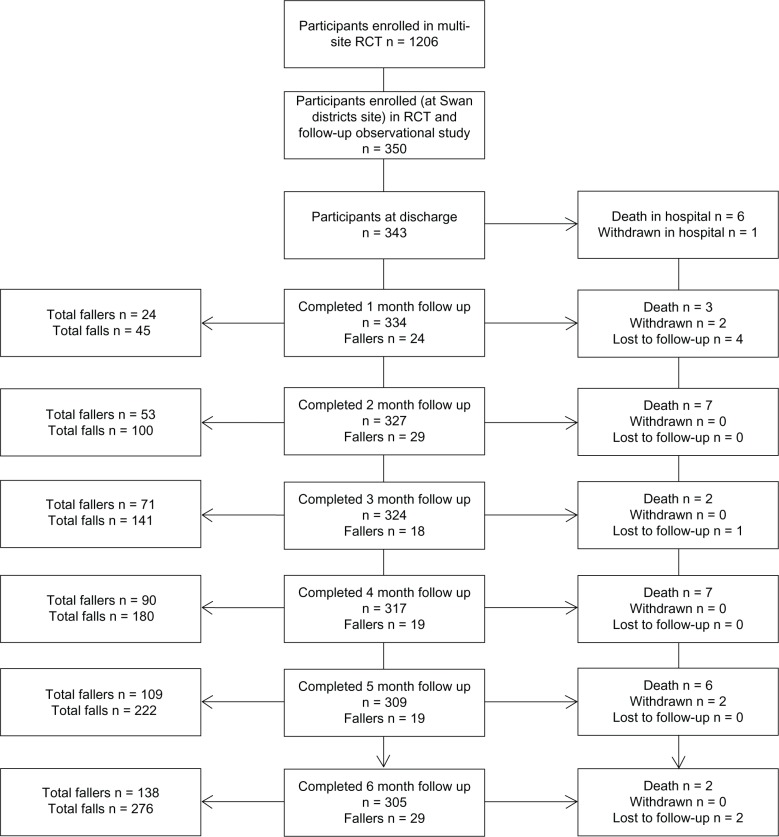

Participants (n = 138) were a cohort of fallers who were part of the observational study (n = 343)1 that was a follow-up to a hospital-based RCT16 (see Figure 1). All participants who fell were included in the cohort for the present study, regardless of group allocation within the RCT. Participants in the larger observational study comprised consecutively admitted patients from acute and rehabilitation wards who were admitted to Swan District Hospital (a 194-bed metropolitan hospital in Perth, Western Australia) between February 2008 and March 2009. The wards admit a broad range of patients from the community with acute diagnoses that include orthopedic conditions, pulmonary conditions, stroke, cardiac conditions, and a range of other diagnoses, such as Parkinson’s disease, and surgical procedures. Patients are also admitted from other hospitals for ongoing rehabilitation. Patients were eligible for inclusion in this trial if they were over 60 years of age, they or their family gave written consent to participate in the larger RCT and in the follow-up phase of the trial, and they were not previously enrolled in the trial. Participants were randomized into one of three groups, ie, a control group which continued with usual care and two groups which received two different versions of an education intervention that aimed to prevent them falling while in hospital in addition to usual care. Both studies are described in detail elsewhere.1,16 Briefly, the results of the RCT demonstrated that one version of the education intervention successfully reduced falls in the hospital setting by over 50% in cognitively intact patients.16 However, the education did not have an ongoing protective effect in reducing falls in either intervention group in the six months following hospital discharge.1

Figure 1.

Participant flow through observational study, including number of falls that occurred during each month of observation.

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were the circumstances of falls that occurred in the six months following discharge. The definition of a fall event used was from the World Health Organization:17 “an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level.” Each fall was recorded as injurious if an injury was reported by participants as following a fall. Injury was classified as none reported, loss of consciousness post-fall, bruising, lacerations, grazes, pain, dislocation, or fracture. The circumstances of the falls were classified by type (dizziness, slip, trip, legs gave way, lost balance), and each type was further classified by whether or not an environment hazard was directly implicated in the fall. Other circumstances recorded were time (24-hour timeline divided into four-hour categories) and location (bedroom, bathroom, kitchen, living, external home environment, outside in broader community). Classifications were determined a priori and based on previous studies conducted in this area.18–20 Participants’ descriptions of the circumstances of the fall, including any medical attention resulting from the fall, were also recorded verbatim. Falls, falls-related injuries, and falls circumstances in the six months after discharge were measured using a falls diary issued to participants and monthly follow-up telephone calls to every participant. These methods of collecting falls data followed recommended guidelines for conducting falls prevention trials.21

Other data collected at discharge included age, diagnosis, discharge destination (community alone, community with partner, community with other, residential facility), length of stay in hospital, whether or not the participant fell during hospital admission, history of falls in the six months prior to hospital admission, mobility status (independently mobile, independently mobile with aid, other), cognitive status using the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire,22 and presence of depressive symptoms using the Geriatric Depression Scale.23 Data were collected six months after discharge by research assistants who conducted a standardized interview during a telephone call to each participant and also if required, to their family or carers. Data collected were a self-reported home visit from the hospital occupational therapist to provide home environment modifications, self-reported use of sleeping medications, and a self-report of receiving assistance with ADL, which was defined as requiring assistance with showering, toileting, or other personal care.

Procedure

Research assistants completed a discharge interview where they provided participants, and if necessary their support person or carers, with information about what constituted a fall based on the World Health Organization definition of a fall event,17 a diary for recording falls in the six months following discharge, and instruction in its use. Participants were contacted monthly by research assistants using the telephone for six months following their discharge to ascertain whether they had sustained any falls, and if so, the circumstances of the fall, including time, location, and any subsequent fall-related injuries. Participants were also asked to record and report the type of fall and any subsequent medical attention they sought for the fall. Participants were able to be assisted by their family or carers to record falls in their diary. Research assistants also scanned all participants’ notes at discharge as a cross-checking procedure, to identify referral to occupational therapy for home environment modifications and personal care services to be implemented at or after discharge.

Statistical analysis

Falls circumstances (type, time, location, and type of injury, subsequent medical attention) were summarized using descriptive statistics. Falls circumstances were also summarized according to whether the fall occurred in the community or in a residential facility setting. This was to allow for the differences between a residential facility setting (such as 24-hour onsite care workers and institutional environment) and a home setting. The participant’s description of the fall was recorded verbatim by the research assistant, and subsequently each fall was coded by the research assistant. Research assistants conferred on any disputed falls classifications, and any that were unable to be resolved were referred to a member of the research team not directly involved in data collection or analysis. Intrinsic participant factors (age, mobility status, history of falls, diagnoses, cognition, presence of depressive symptoms, discharge destination, assistance with ADL) were then entered into univariate logistic regression analyses as independent variables, with the location and time of falls in the six months after discharge being the dependent variable. Each analysis included clustering by participants and use of robust variance estimates to account for multiple observations (falls) by individual participants.24 The results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Multivariate logistic regression using backward stepwise regression25 was subsequently used to identify independent risk factors for location and time of falls. Independent risk factors with a significance of P < 0.20 were entered into a multivariate model. Covariates were then removed from the main model on the basis of having the highest P value until all covariates retained in the model reached P < 0.05. Each variable was then fitted back into the model individually to check for significance, and finally the group variable that remained forced into the model throughout was examined for significance (P = 0.05). Because participants had been randomized into one of three groups as part of the larger RCT, all analyses were undertaken with the interaction of the group as an independent variable of interest forced into the analysis. Results are presented as adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Falls that required hospital admission were also compared with Australian national injury data published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare20 to determine if the proportions of falls-related hospital admissions in specific locations in the post discharge cohort were significantly different from the proportion of falls-related hospital admissions in the general population. These comparisons were done using Fisher’s Exact test. All statistical tests were conducted using Stata SE version 11 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The demographic characteristics of the fallers are presented in Table 1. There were 276 reported falls, of which 150 (54.3%) resulted in fall-related injuries. Of the 138 fallers, 91 (65.9%) sustained an injurious fall. Seventy-six (55.1%) participants fell once, 28 (20.3%) of participants fell twice, 18 (13.0%) participants fell three times, and 16 (11.6%) participants fell four or more times. There were 28 (20.3%) fallers who came from a residential facility, and 36 (24.0%) of the injurious falls occurred in these facilities.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of fallers

| Variable | (n = 138) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 80.3 ± 8.7 |

| Female, n (%) | 78 (56.5) |

| Length of stay in hospital, (days) mean ± SD | 33.2 ± 34.0 |

| Falls during hospital admission, n (%) | 27 (19.6) |

| Previous falls in six months prior to hospital admission, n (%) | 96 (69.6) |

| Discharge destination, n (%) | |

| Community alone | 45 (32.6) |

| Community with partner | 48 (34.8) |

| Community with other | 17 (12.3) |

| Residential facility | 28 (20.3) |

| Mobility, n (%) | |

| Uses no aid | 35 (25.4) |

| Uses walking aid | 89 (64.5) |

| Uses wheelchair to mobilize/mobilizes with assistance | 14 (10.1) |

| Depressive symptoms | |

| GDS,a mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 2.9 |

| GDS, scores ≤4, n (%) | 71 (51.4) |

| GDS, scores 4> n (%) | 67 (48.6) |

| Cognition | |

| SPMSQ mean ± SD | 8.1 ± 2.0 |

| SPMSQ <8, n (%) | 49 (35.5) |

| SPMSQ ≥8, n (%) | 89 (64.5) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Neurological | 19 (13.7) |

| Orthopedic | 24 (17.4) |

| Cardiac | 9 (6.5) |

| Pulmonary | 24 (17.4) |

| Other geriatric managementc | 39 (28.3) |

| Other (surgery, other medical conditions, major trauma) | 23 (16.7) |

| Use of sleeping medication in six months after discharge, n (%) | 32 (23.2) |

| Home visit by occupational therapist after discharge, n (%) | |

| Visit at or immediately after discharge | 55 (39.8) |

| Did not visit participant | 48 (34.8) |

| Did not visit, participant discharged to residential care facility | 28 (20.3) |

| Missing | 7 (5.1) |

| Received assistance with ADLd in the six months following discharge, n (%) | 55 (39.9) |

Notes:

Geriatric Depression Scale, range 1–15, score >4 indicates presence of depressive symptoms; Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, range 1–10, greater score indicates better cognitive function;

diagnoses not otherwise classified, including rehabilitation for functional decline;

defined as requiring assistance with showering, toileting or other personal care.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; SD, standard deviation; SPMSQ, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire.

Falls classified by type are presented in Table 2. Participants or their carers were unable to provide any description of 38 falls, including falls where participants were found on the ground after an unspecified period. Of those participants (or their carers) who were able to describe their fall, 27 falls (9.8%) were directly attributed to the use of a walking aid and 63 (22.8%) directly implicated an environmental hazard. These included uneven paving and garden litter, such as tree nuts and sticks outside, and bedclothes, wet floors, mats, and pets indoors.

Table 2.

Falls classified by type, including whether environmental hazard was implicated

| Type of fall | n = 276 (100%) |

|---|---|

| Tripped | |

| Environment hazard directly implicated | 43 (15.6) |

| Environment hazard not implicated | 19 (6.9) |

| Lost balance | |

| Environmental hazard directly implicated | 5 (1.8) |

| Environmental hazard not implicated | 56 (20.3) |

| Legs gave way | 48 (17.4) |

| Dizziness | 34 (12.3) |

| Slipped | |

| Environment hazard directly implicated | 15 (5.4) |

| Environment hazard not implicated | 18 (6.5) |

| No information | 38 (13.8) |

Of the 255 falls for which there were data available, 190 falls (74.5%) occurred indoors and 65 (25.5%) occurred in the external home environment or wider community. When falls that occurred in residential facilities (n = 52) were removed from the analysis, there were 203 falls occurring in the community. Of these, 139 (68.5%) occurred indoors and 64 (31.5%) outside the home. The number of falls for each month of the study is presented in Figure 1. Participants reported 170 injuries from 137 falls, with no information available for 13 falls and some participants reporting more than one injury from a fall. There were 11 fractures, of which two were hip fractures and two were joint dislocations. Other injuries reported were loss of consciousness post fall (n = 1), bruising (n = 66), lacerations (n = 32), grazes (n = 22), and pain (n = 36). The location and time of falls and injurious falls are presented in Table 3. Of the 80 falls that occurred in the bedroom, the most frequent time of occurrence was between 6 am and 10 am (n = 27, 33.8%).

Table 3.

Location and time of falls and injurious falls

| Falls n = 276 (100%) | Injurious falls n = 150 (100%) | Falls in community n = 203 (100%) | Falls in residential facilities n = 52 (100%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||

| Bedroom | 80 (29.0) | 42 (28.0) | 53 (26.1) | 27 (51.9) |

| Bathroom/toilet | 40 (14.5) | 20 (13.3) | 30 (14.8) | 10 (19.2) |

| Kitchen | 16 (5.8) | 6 (4.0) | 12 (5.9) | 4 (7.7) |

| Living | 54 (19.6) | 26 (17.3) | 44 (21.7) | 10 (19.2) |

| External home environment | 39 (14.1) | 24 (16.0) | 38 (18.7) | 1 (1.9) |

| Outside in community | 26 (9.4) | 19 (12.7) | 26 (12.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 21 (7.6) | 13 (8.7) | ||

| Time | ||||

| 6–10 am | 79 (28.6) | 49 (32.7) | 67 (33.0) | 12 (23.1) |

| 10–2 pm | 38 (13.7) | 14 (9.3) | 29 (14.3) | 9 (17.3) |

| 2–6 pm | 41 (14.9) | 22 (14.7) | 33 (16.3) | 8 (15.4) |

| 6–10 pm | 38 (13.7) | 20 (13.3) | 35 (17.3) | 3 (5.8) |

| 10–2 am | 12 (4.4) | 6 (4) | 9 (4.4) | 3 (5.8) |

| 2–6 am | 9 (3.3) | 5 (3.3) | 7 (3.4) | 2 (3.8) |

| Missing | 59 (21.4) | 34 (22.7) | 23 (11.3) | 15 (28.8) |

Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for falls occurring at specific locations and times that showed significant associations are presented in Table 4. Falls in the external home environment and outside in the wider community were combined and analyzed as one category due to small numbers. There was no significant association between location and time of falls and other factors, including age, other diagnoses, cognition, and discharge destination. There was no association between the circumstances of the falls (type of fall, location, or time) and whether participants had received the inpatient education intervention.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses: Association between location and times of falls at home after discharge and independent variables

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | AOR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Bedroom fall | Assistance with ADLa | 3.9 (2.1–7.1) | <0.001 | 3.0 (1.6–5.6) | 0.001 |

| Hospital faller | 3.6 (1.9–6.7) | <0.001 | 2.3 (1.2–4.4) | 0.01 | |

| Geriatric diagnosis | 2.3 (1.2–4.5) | 0.01 | |||

| Depressed mood at dischargeb | 3.2 (1.8–5.8) | <0.001 | 2.2 (1.2–3.9) | 0.008 | |

| Bathroom fall | Assistance with ADL | 2.4 (1.1–5.4) | 0.03 | ||

| Hospital faller | 3.3 (1.5–7.1) | 0.003 | 2.8 (1.2–6.8) | 0.02 | |

| Kitchen fall | Assistance with ADL | 3.5 (1.3–9.6) | 0.02 | ||

| Outside fall (external home environment or in community) | Assistance with ADL | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 0.005 | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 0.005 |

| Fall between 6 am and 10 am | Uses walking aid at discharge | 2.2 (1.2–4.0) | 0.01 | 2.1 (1.1–3.8) | 0.02 |

| Hospital faller | 1.9 (1.1–3.5) | 0.03 | 1.8 (1.0–3.3) | 0.05 | |

Notes:

Defined as requiring assistance with showering or other personal care;

defined using Geriatric Depression Scale, range 1–15, score >4 indicates presence of depressive symptoms.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ADL, activities of daily living.

In the six months after discharge, there were 41 reported visits to hospital due to a fall. Of the 41 hospital visits, 28 occurred in community-dwelling participants and 13 occurred in participants in residential facilities. The total discharge cohort (n = 343) in the larger RCT consisted of 285 community-dwelling participants and 58 residential facility participants, therefore 22% of residential facility discharges and 9.8% of community discharges resulted in readmission to hospital due to a fall in the six months after discharge.

The relative differences between the proportion of falls that occurred by location and required a hospital visit were compared with the proportion of falls by location requiring a hospital visit as reported in the Australian national dataset.20 These data are reported in Table 5. Falls that occurred in the bedroom in the post discharge period were significantly more likely to result in a visit to hospital in that period than falls in the bedroom recorded in the national dataset20 (odds ratio 3.85, 95% confidence interval 1.76–8.42, P = 0.004).

Table 5.

Hospital admissions by location of fall compared with Australian national dataset of hospital admissions due to fallsa

| Location of fall | Hospital admissions n = 41 (100%) | National dataset hospital admissionsa n = 78,054 | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedroom | 7 (17.1) | 3481 (4.4) | 3.8 (1.7–8.4) | 0.004 |

| Bathroom | 4 (9.8) | 4111 (5.2) | 1.8 (0.6–5.0) | 0.3 |

| Kitchen | 2 (4.9) | 2496 (3.2) | 1.5 (0.0–5.7) | 0.4 |

| Living | 4 (9.7) | 2028 (2.6) | 3.7 (1.4–10.1) | 0.03 |

| Other indoors and not specified | 3 (7.3) | 19,848 (25.2) | ||

| External home environment | 3 (7.3) | 6341 (8.1) | 0.9 (0.2–2.7) | 1.0 |

| Total home and driveway | 23 (56.1) | 38,305 (48.7) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.6 |

| Outside in community | 5 (12.2) | 8950 (11.4) | 1.0 (0.4–2.6) | 0.8 |

| Residential facility | 13 (31.7) | 17,736 (22.6) | 1.4 (0.7–2.5) | 0.3 |

| Unknown | 13,063 (16.6) |

Discussion

This study described the circumstances of falls, including location and time, in a large post-discharge population. Nearly 75% of falls and over 60% of injurious falls occurred indoors, and even when participants residing in residential settings were excluded, nearly 70% of falls occurred indoors. This figure is higher than in previous studies conducted among community-dwelling older people, which have reported that 12%–65% of falls occur indoors.18,26–28 Additionally, patients receiving assistance with ADL were significantly less likely to fall outside, and the number of falls outside remained consistent over the six-month period. In a study conducted in a post-discharge rehabilitation population, falls outside increased over a three-month period while falls indoors decreased,29 but these data might reflect the inclusion of younger people who may have improved more rapidly after discharge. It has also been suggested that compared with people who are able to mobilize outside in the community, older people who fall indoors may have a different set of risk factors, including poorer health and more medical conditions.26,30 Studies in post-discharge populations have reported risk factors for falls, such as requiring assistance with ADL, depressed mood at discharge, and using a gait aid,1,2 which may indicate poorer health, although these risk factors are also present in general community populations.31 Additionally, previous large studies have confirmed that functional decline and medical problems are frequent in this population,32,33 which could explain the high incidence of indoor falls, because older people with these problems are less likely to be able to undertake home activities outside, such as gardening or community-based activities.

In the community-dwelling participants, over one quarter of falls occurred in the bedroom. This is less than the 38% of bedroom falls reported in a study conducted in a frail population,34 but higher than a study conducted in a community-dwelling population which found that 20% of falls occurred in the bedroom.18 Nearly 10% of community-dwelling participants were readmitted to hospital following a fall, and the bedroom was the location where the highest number of injurious falls occurred. While other Australian data also reveal that 10% of older community-dwelling people were admitted to hospital with a fall over a 12-month period,35 in our sample of recently discharged patients, bedroom falls were three times more likely to result in a hospital admission than bedroom falls in the broader community.20 We specifically asked participants to distinguish between falls that occurred in the bedroom as distinct from the bathroom or toilet. Hence our results highlight the bedroom as a high-risk area of the home for older people after discharge, especially those who have fallen in hospital and are receiving assistance with ADL. Falls and injurious falls in this postdischarge population also occurred more frequently in the morning compared with a study conducted in a community-dwelling group where falls were spread over the morning and afternoon.36 Older people may complete some ADL, such as dressing and moving in and out of bed, during the morning period prior to ADL assistance being provided. Previous studies have identified that older people may engage in ADL after discharge even if they are at risk of falls because they do not recognize their current physical limitations or are reluctant to ask for assistance with ADL.37 Alternatively, older people may recognize their current mobility limitations but engage in ADL independently because they wish to preserve their autonomy.38

Older people may also be using fewer falls prevention strategies in their bedroom, such as using their gait aid, compared with other areas indoors or in the external home environment. Previous studies have shown that older people who have been recently discharged from hospital have low levels of knowledge about falls and suitable falls prevention strategies.39 Older people may require suitable education that focuses on the bedroom as a frequent location for falls after discharge. The observational trial from which these falls data were collected found that inpatient education had no sustained effect on reducing falls after discharge.1 These data also demonstrate that the inpatient education intervention did not reduce falls in particular locations or at particular times of day. This most likely indicates that education focusing on the post-discharge period is required for reducing falls in the home setting.

Strong evidence supports recommendations for older community-dwelling people to engage in suitably targeted falls prevention strategies, including exercise and correction of vision.8 However, approximately 40% of our participants were receiving assistance with ADL and these patients may need to be prescribed exercise programs suitable for people with limitations in functional activities.40,41 A recent RCT conducted among community-dwelling people who had fallen previously found that incorporating functional exercises into daily life round the home improved function and reduced falls.41 However, it may also be that there should also be more focus on examining the safety of the bedroom environment and training for activities undertaken within this environment in the post discharge-population. Environmental hazards were implicated in 22% of falls, which is similar to results reported for a large community-dwelling population.35 Studies suggest that therapists should further explore older people’s levels of adherence with environmental interventions.9,15 However, previous studies have not found evidence that hazard reduction alone significantly reduces falls,14 and we suggest that some indoor hazards identified, such as bedclothes, can be difficult to modify or remove. Environmental modification is considered a routine component of therapeutic interventions, but it has been recommended that this be provided in conjunction with training that aims to raise older people’s awareness about how to negotiate their environment and problem-solving solutions.10 Providing assistance with ADL in the post-discharge population may also be a viable intervention to examine for its efficacy in reducing the risk of injurious falls. Studies have suggested that older people be provided with more assistance when first discharged home from hospital,42,43 and an observational study has demonstrated that receiving assistance with ADL in the six months after discharge reduces the risk of injurious falls.1

Conclusion

These data represent a large number of falls that occurred during a prospective study conducted in the six-month period after hospital discharge.1 The results indicate that the bedroom is a high-risk area for injurious falls in this population. The mean age of the cohort was 80 years and it was drawn from one hospital, hence there are limitations in generalizing these results to other post-discharge populations. However, the cohort was representative of a broad acute rehabilitation population, because it included patients with a broad range of diagnoses, cognitive impairment, and those who spoke English as a second language. Given that 28 of the fallers lived in residential facilities, the circumstances of these falls may not be relevant to older people living in community settings. Further research is needed that investigates specific interventions for reducing falls and falls injuries indoors in older people who have recently been discharged from hospital. Interventions that focus on indoor settings in the home, in particular the bedroom, and provide patient education and training or assistance with ADL, could be evaluated for their effect in this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a project grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. A-MH is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship. TPH is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship. TH is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship with funding provided by the Department of Health and Ageing.

Footnotes

Disclosure

TPH is the Director of Hospital Falls Prevention Solutions Pty Ltd, a company that licenses use of and trains health professionals in how they can provide the Safe Recovery Training Program, which is a falls prevention patient education program designed to be delivered to older patients on admission to a hospital to prevent inhospital falls. This company did not have any involvement in the study conception and design or project organization. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hill AM, Hoffmann T, McPhail S, et al. Evaluation of the sustained effect of inpatient falls prevention education and predictors of falls after hospital discharge – follow-up to a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(9):1001–1012. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahoney JE, Palta M, Johnson J, et al. Temporal association between hospitalization and rate of falls after discharge. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(18):2788–2795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd BD, Williamson DA, Singh NA, et al. Recurrent and injurious falls in the year following hip fracture: a prospective study of incidence and risk factors from the Sarcopenia and Hip Fracture study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(5):599–609. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davenport RD, Vaidean GD, Jones CB, et al. Falls following discharge after an in-hospital fall. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-9-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackintosh SF, Hill KD, Dodd KJ, Goldie PA, Culham EG. Balance score and a history of falls in hospital predict recurrent falls in the 6 months following stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2006;87(12):1583–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson W, Clapperton A, Mitchell R. The incidence and cost of falls injury among older people in New South Wales 2006/07. Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2010. SHPN (CHA) 100199. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolinsky FD, Bentler SE, Liu L, et al. Recent hospitalization and the risk of hip fracture among older Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(2):249–255. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Platz A, et al. Effect of high-dosage cholecalciferol and extended physiotherapy on complications after hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(9):813–820. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemson L, Mackenzie L, Ballinger C, Close JC, Cumming RG. Environmental interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older people: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Aging Health. 2008;20(8):954–971. doi: 10.1177/0898264308324672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, La Grow SJ, et al. Randomised controlled trial of prevention of falls in people aged greater than or equal to 75 with severe visual impairment: the VIP trial. BMJ. 2005;331(7520):817–820. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38601.447731.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lord SR, Menz HB, Sherrington C. Home environment risk factors for falls in older people and the efficacy of home modifications. Age Ageing. 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii55, ii59. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikolaus T, Bach M. Preventing falls in community-dwelling frail older people using a home intervention team (HIT): results from the randomized falls-HIT trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(3):300–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.La Grow SJ, Robertson MC, Campbell AJ, Clarke GA, Kerse NM. Reducing hazard related falls in people 75 years and older with significant visual impairment: how did a successful program work? Inj Prev. 2006;12(5):296–301. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.012252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Currin ML, Comans TA, Heathcote K, Haines TP. Staying safe at home. Home environmental audit recommendations and uptake in an older population at high risk of falling. Australas J Ageing. 2012;31(2):90–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2011.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haines TP, Hill AM, Hill KD, et al. Patient education to prevent falls among older hospital inpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;171(6):516–524. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Violence and injury prevention Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/other_injury/falls/en/index.htmlAccessed November 20, 2012

- 18.Carter SE, Campbell EM, Sanson-Fisher RW, Gillespie WJ. Accidents in older people living at home: a community-based study assessing prevalence, type, location and injuries. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(6):633–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2000.tb00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lord SR, Sherrington C, Menz HB, Close JCT. Falls in Older People: Risk Factors and Strategies for Prevention. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley C.Hospitalisations due to falls in older people, Australia 2008–09 Injury research and statistics series no. 62. Cat. no. INJCAT 138 Canberra: AIHW; 2012Available from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737421923Accessed June 5, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamb SE, Jorstad-Stein EC, Hauer K, Becker C. Development of a common outcome data set for fall injury prevention trials: The Prevention of Falls Network Europe consensus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(9):1618–1622. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson MC, Campbell AJ, Herbison P. Statistical analysis of efficacy in falls prevention trials. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(4):530–534. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li W, Keegan TH, Sternfeld B, Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, Kelsey JL. Outdoor falls among middle-aged and older adults: a neglected public health problem. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1192–1200. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kojima S, Furuna T, Ikeda N, Nakamura M, Sawada Y. Falls among community-dwelling elderly people of Hokkaido, Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2008;8(4):272–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2008.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelsey JL, Berry SD, Procter-Gray E, et al. Indoor and outdoor falls in older adults are different: the maintenance of balance, independent living, intellect, and Zest in the Elderly of Boston Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(11):2135–2141. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Worley A, Barras S, Grimmer-Somers K. Falls are a fact of life for some patients after discharge from a rehabilitation programme. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(16):1354–1363. doi: 10.3109/09638280903514754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelsey JL, Procter-Gray E, Berry SD, et al. Reevaluating the implications of recurrent falls in older adults: location changes the inference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(3):517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21(5):658–668. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoogerduijn JG, Buurman BM, Korevaar JC, Grobbee DE, de Rooij SE, Schuurmans MJ. The prediction of functional decline in older hospitalised patients. Age Ageing. 2012;41(3):381–387. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mudge AM, O’Rourke P, Denaro CP. Timing and risk factors for functional changes associated with medical hospitalization in older patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(8):866–872. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vikman I, Nordlund A, Naslund A, Nyberg L. Incidence and seasonality of falls amongst old people receiving home help services in a municipality in northern Sweden. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2011;70(2):195–204. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v70i2.17813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milat AJ, Watson WL, Monger C, Barr M, Giffin M, Reid M. Prevalence, circumstances and consequences of falls among community-dwelling older people: results of the 2009 NSW Falls Prevention Baseline Survey. N S W Public Health Bull. 2011;22(4):43–48. doi: 10.1071/NB10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Garry PJ, Baumgartner RN. A two-year longitudinal study of falls in 482 community-dwelling elderly adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53(4):M264–M274. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.4.m264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haines TP, Lee DC, O’Connell B, McDermott F, Hoffmann T. Why do hospitalized older adults take risks that may lead to falls? Health Expect. 2102 Nov 29; doi: 10.1111/hex.12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Host D, Hendriksen C, Borup I. Older people’s perception of and coping with falling, and their motivation for fall-prevention programmes. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7):742–748. doi: 10.1177/1403494811421639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill AM, Hoffmann T, Beer C, et al. Falls after discharge from hospital: is there a gap between older peoples’ knowledge about falls prevention strategies and the research evidence? Gerontologist. 2011;51(5):653–662. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Resnick B, Orwig D, Wehren L, Zimmerman S, Simpson M, Magaziner J. The Exercise Plus Program for older women post hip fracture: participant perspectives. Gerontologist. 2005;45(4):539–544. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clemson L, Fiatarone Singh MA, Bundy A, et al. Integration of balance and strength training into daily life activity to reduce rate of falls in older people (the LiFE study): randomised parallel trial. BMJ. 2012;345:e4547. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altfeld SJ, Shier GE, Rooney M, et al. Effects of an enhanced discharge planning intervention for hospitalized older adults: a randomized trial. Gerontologist. 2013;53(3):430–440. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fairhall N, Sherrington C, Kurrle SE, et al. Effect of a multifactorial interdisciplinary intervention on mobility-related disability in frail older people: randomised controlled trial. BMC Med. 2012;10:120. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]