Abstract

We prepared solid dispersions (SDs) of tanshinone IIA (TSIIA) with silica nanoparticles, which function as dispersing carriers, using a spray-drying method and evaluated their in vitro dissolution and in vivo performance. The extent of TSIIA dissolution in the silica nanoparticles/TSIIA system (weight ratio, 5:1) was approximately 92% higher than that of the pure drug after 60 minutes. However, increasing the content of silica nanoparticles from 5:1 to 7:1 in this system did not significantly increase the rate or extent of TSIIA dissolution. The physicochemical properties of SDs were investigated using scanning electron microscopy, differential scanning calorimetry, X-ray powder diffraction, and Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy. Studying the stability of the SDs of TSIIA revealed that the drug content of the formulation and dissolution behavior was unchanged under the applied storage conditions. In vivo tests showed that SDs of the silica nanoparticles/TSIIA had a significantly larger area under the concentration-time curve, which was 1.27 times more than that of TSIIA (P < 0.01). Additionally, the values of maximum plasma concentration and the time to reach maximum plasma concentration of the SDs were higher than those of TSIIA and the physical mixing system. Based on these results, we conclude that the silica nanoparticle based SDs achieved complete dissolution, increased absorption rate, maintained drug stability, and showed improved oral bioavailability compared to TSIIA alone.

Keywords: tanshinone IIA, solid dispersions, silica nanoparticles, in vitro dissolution, stability, oral bioavailability

Introduction

Tanshinone IIA (TSIIA) is one of the major active components extracted from the root of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge and demonstrates various effects on the cardiovascular system, including vasorelaxation and a cardioprotective effect.1–4 However, the oral bioavailability of TSIIA is very low,5,6 likely due to poor water solubility7 and insufficient TSIIA dissolution rate.8–10

Drug release is a crucial and limiting step in oral drug bioavailability11,12 especially for drugs with low gastrointestinal solubility and high permeability.13–15 Previous studies have shown that the formation of solid dispersions (SDs) is a promising strategy for increasing the dissolution rate and solubility of drugs16–20 belonging to class II of the Biopharmaceutical Classification System.21 Dissolution can be improved by reducing the particle size of the drug and increasing the surface area;22,23 drug wettability can be improved by mixing the drug with a high concentration of the carrier in the surrounding solution;24,25 and the drug can be transformed from a crystalline to an amorphous state.26 Currently, the typical carriers widely used for the formulation of SDs consist of organic materials that are highly water soluble and/or polymeric in nature.27–30 In addition to these carriers, inert hydrophilic carriers, such as inorganic silica-based materials31,32 which have relatively large specific surface areas, and thus produce powders in which the drug may be highly dispersed, are receiving increasing attention. Takeuchi et al33–35 reported that SDs with porous silica or colloidal silica prepared using the spray-drying method can improve the dissolution property of tolbutamide and indomethacin. In this system, silica played an important role in controlling the polymorphs and inhibited crystallization of the drug in the SD under severe storage conditions.

Several grades of silica particles with different properties, such as pore structure, degree of hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity, and particle size are available for both porous and nonporous silica.36 The specific functional features of different types of silica can also be exploited to regulate the drug release rate.37–39

Silica nanoparticles are amorphous in nature. The nanoparticles are small in size and have a large specific surface area, which improves drug dispersion in carriers, and significantly decreases the particle size of the drug,40–43 possibly to the molecular level.44 Many silanol groups are present on the surface of silica nanoparticles, which may be able to form hydrogen bonds with the drug molecules during formulation of SDs.45,46 In addition, a high drug dissolution rate can be achieved by improving the wettability of the drug particles. SDs have been successfully prepared using silica nanoparticles as the carrier.47 Further, compared to the crystalline drug, the SD of the drug shows significantly improved oral bioavailability. Formulations prepared by SD with water soluble polymer carriers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG)48 or polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP)49 tend to be sticky or tacky, which results in decreased recovery of the SD during preparation and difficulty in handling subsequent processes. However, silica nanoparticles may reduce the stickiness or tackiness imparted by excipients with low melting points and thus prevent processing problems. The resultant SD particles have free flowability and thus facilitate downstream processing to solid dosage forms. In addition, SD provides greater physical stability, which prevents recrystallization.50

In this study, we prepared SDs of TSIIA using silica nanoparticles as dispersing carriers. The product with a nonporous structure consists of primary particles of about 50 ± 5 nm, which have a very high specific surface area (200 ± 30 m2/g). The SDs were produced using a spray-drying method. The first part of the study consisted of characterizing the SDs. A set of complementary techniques (differential scanning calorimetry [DSC], scanning electron microscopy [SEM], X-ray powder diffraction [XRPD], and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy [FTIR]) was used to monitor the physical changes of TSIIA in the SDs. Subsequently, a drug stability test was performed on freshly prepared SDs and on SDs stored for 6 months at 40°C/75% relative humidity (RH). Finally, we examined the bioavailability of the SDs of silica nanoparticles-TSIIA in rats and compared it to that of TSIIA powders and its physical mixing systems (PMs).

Materials and methods

Instruments and materials

A TSIIA standard was obtained from the National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products (Beijing, People’s Republic of China). TSIIA with purity greater than 98% was supplied by the Nanjing Zelang Medical Technology Co, Ltd (Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China). Silica nanoparticles with a primary particle size of about 50 ± 5 nm were supplied by Hangzhou Wanjing New Material Co, Ltd (Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China). All reagents were analytical grade except methanol, which was chromatographic grade. Healthy male Sprague Dawley® rats were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Jiangsu Provincial Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China).

Preparation of SDs and PMs

The SDs of TSIIA with silica nanoparticles were prepared using the spray-drying method. The drug-to-carrier ratios used in this study were 1:1, 1:3, 1:5, and 1:7 (by weight). TSIIA powder (200 mg) was dissolved in 500 mL of ethanol solution, into which variable amounts of silica nanoparticles (200, 600, 1000, and 1400 mg) were suspended. After ultrasonication for 15 minutes, this suspension was loaded into a spray-dryer (SD-06 Labplant; Labplant UK Limited, North Yorkshire, UK) at a rate of 8 mL/minute. The inlet and outlet temperatures of the drying chamber were maintained at 75°C and 38°C, respectively. The PMs were prepared by mixing TSIIA with silica nanoparticles at ratios of 1:5 (weight by weight) and then grinding them thoroughly using a mortar and pestle until a homogeneous mixture was obtained. All SDs were dried in a desiccator with blue silica gel under reduced pressure for 1 day before testing their physicochemical properties.

High-pressure liquid chromatographic analysis of TSIIA

The concentration of TSIIA in the dissolution medium was determined using a high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a UV detector set at 270 nm. Separation was performed at 30°C on a Diamonsil™ RP-C18 (DIKMA, Lake Forest, CA, USA) column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). The mobile phase of methanol and water (85:15, volume:volume) was used at a flow rate of 1.0 mL · min−1. The samples were filtered through 0.45 μm membrane filters (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) before use, and the injection volume was 20 μL. The linearity range of the calibration curve was within 0.420–8.400 μg · mL−1 with a correlation coefficient of 0.9999. The recovery rates for the TSIIA were in the range of 99%–102%, and the relative standard deviation was less than 2%. The intra-and interday precision values for the TSIIA were below 2%.

In vitro dissolution studies

The pharmaceutical performance of pure TSIIA and its SDs was evaluated using in vitro dissolution tests. The tests were performed according to the USP 24 method 2 (paddle method) in a BCZ-8A intellectualized dissolution apparatus (Tianjin University exact apparatus Co., Ltd., Tianjin, People’s Republic of China). Samples equivalent to 5 mg TSIIA were spread onto the surface of the dissolution medium (900 mL of distilled water containing 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate), which was thermostatically maintained at 37°C ± 0.5°C and stirred at 50 rpm. Samples were collected periodically and replaced with fresh dissolution medium. The samples were filtered by Amicon® Ultra-4 3K Centrifugal Filter Devices (EMD Millipore) and then were analyzed for TSIIA using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described above. Dissolution experiments were performed in triplicate, and the average dissolution profiles and standard deviations were calculated.

DSC

Thermal analysis of TSIIA, silica nanoparticles, PMs, and SDs was performed using a differential scanning calorimeter (204A/G Phoenix® instrument; Netzsch, Selb, Germany). The samples were hermetically sealed in aluminum pans and heated from 25°C to 350°C at a rate of 10°C · min−1. All the DSC measurements were performed in a nitrogen atmosphere, and the flow rate was 50 mL · min−1.

SEM

The shape, surface, and cross-sectional morphology of the powder samples were observed using a scanning electron microscope (S-3000N; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

XRPD

XRPD patterns of TSIIA, silica nanoparticles, PMs, and SDs were determined using an X-ray diffractometer (D8-Advance; Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany), and the data were collected using primary monochromated radiation (Cu Kα1, λ = 1.5406 Å) over a 2θ range of 0°–70° at a step size of 0.04 and a dwell time of 10 seconds per step.

FTIR

FTIR measurements were carried out using an infrared spectrophotometer (Victor22; Bruker) at room temperature. Samples of TSIIA, silica nanoparticles, PMs, and SDs were previously ground and mixed thoroughly with potassium bromide in the sample. The scanning range was 400 to 4000 cm−1 and the resolution was 1 cm−1.

Stability test

Physical stability parameters, such as in vitro drug release and drug content were studied for SDs stored under stability conditions of 40°C/75% RH for 6 months.

Bioavailability study

Eighteen male Sprague Dawley® rats (Experimental Animal Center of Jiangsu Provincial Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine) weighing 180–220 g were housed in an environmentally controlled breeding room (22°C ± 2°C, 60% ± 5% RH, and circulating fresh air) for 1-week before the start of the experiment. The rats were fed standard laboratory chow (Experimental Animal Center of Jiangsu Province Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine) with water and fasted overnight but supplied with water ad libitum before the experiment. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jiangsu Provincial Academy of Chinese Medicine. The rats were randomly divided into three groups. Three formulations (TSIIA and PMs and SDs with TSIIA/silica nanoparticles at a ratio of 1:5) at a dose equivalent to 60 mg/kg of TSIIA were orally administered to the three groups of six rats (eighteen rats total). Plasma samples (0.5 mL) were collected from the ophthalmic venous plexus of the rat at 0 (pretreatment), 0.33, 0.66, 1, 1.33, 1.66, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours after administration. Next, plasma was obtained after centrifugation for 10 minutes at 3000 rpm and stored at −4°C. The plasma (0.2 mL) was mixed with 0.2 mL of mobile solution containing loratadine (500 ng/mL) and used as an internal standard. Then, 600 μL of acetonitrile was added and vortex mixed for 5 minutes to fully precipitate the protein and extract TSIIA from the rat plasma. The sample was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 minutes. Next, the supernatant was transferred to a clean centrifuge tube and dried under a stream of nitrogen in a water bath maintained at 38°C. The residue was resuspended in 200 μL of methanol and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 12,000 rpm. Aliquots (20 μL) of the supernatant were injected into the high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) system for analysis, and the chromatographic conditions were consistent with those used for the HPLC analysis of TSIIA.

Data presentation and analysis

The pharmacokinetic parameters, including maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to reach Cmax (Tmax), half-life (t1/2) area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC0–t), and AUC0–∞, were calculated by compartmental analysis using the DAS software program version 1.0. Data were reported as the arithmetic mean values ± standard deviation (mean ± standard deviation). The P-values were calculated between the different pairs of formulations using two-tailed Student’s t-tests.

Results and discussion

In vitro dissolution study

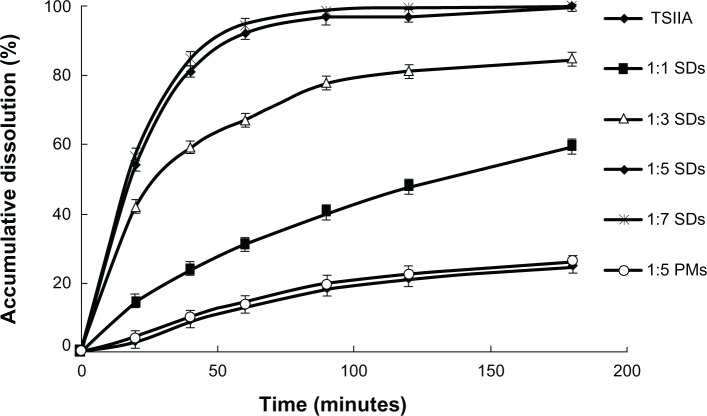

The dissolution profiles of TSIIA from the PMs and SDs are shown in Figure 1. Pure TSIIA had a poor dissolution rate, and less than 30% of the drug dissolved after 120 minutes. The PMs showed a slight improvement in drug dissolution, which was most likely attributed to an increase in the wetting and local solubilization by the excipients in the diffusion layer,51 which prevented drug aggregation,52 and weak hydrogen bond interaction between the drug and carriers.38 Nevertheless, the SDs with silica nanoparticles had a remarkably higher dissolution rate of TSIIA than pure TSIIA and corresponding PMs (Figure 1). In addition, the dissolution rate of TSIIA increased with increasing ratios of TSIIA/silica nanoparticles. At a TSIIA/silica nanoparticles ratio of 1:5, more than 90% of the TSIIA was dissolved within 60 minutes, which was approximately a 7-fold increase compared to pure TSIIA. However, the dissolutions of TSIIA (1-hour) prepared at ratios of 1:5 and 1:7 were very similar, which were 92.1% and 94.3%, respectively. This improvement in the dissolution of the drug by the SDs may be attributed to several factors, including a significant reduction in particle size during the formation of a SD, increased surface area, the presence of an amorphous form of the drug53 (as confirmed by DSC and XRD studies), and absorption of the TSIIA onto a large surface area of carrier nanoparticles to enhance drug dissolution, which has been previously described for silica based excipients since the early 1970s.36

Figure 1.

The dissolution profiles of TSIIA and SDs and PMs prepared using different ratios of TSIIA/silica nanoparticles (1:1, 1:3, 1:5, and 1:7 SDs and 1:5 PMs).

Note: Each point represents the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Abbreviations: PMs, physical mixtures; SDs, solid dispersions; TSIIA, tanshinone IIA.

SEM

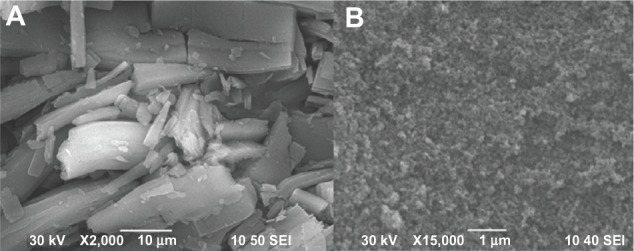

The SEM images of TSIIA and SDs prepared at a 1:5 ratio of TSIIA/silica nanoparticles are shown in Figure 2. Pure TSIIA (Figure 2A) consisted of a mixture of some large crystals with microparticles, which exhibited flat broken needles of different sizes. However, the SDs appeared as irregular-shaped particles, which were smaller than pure TSIIA. Moreover, the original morphology of TSIIA was not visible in the photomicrographs, which suggested that TSIIA dispersed uniformly into the carrier. Thus, the reduced particle size, increased surface area, and close contact between the silica nanoparticles and TSIIA may be responsible for the enhanced drug dissolution of the SDs.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy photomicrographs of (A) TSIIA and (B) SDs prepared using a TSIIA/silica nanoparticles ratio of 1:5.

Abbreviations: SDs, solid dispersions; TSIIA, tanshinone IIA.

DSC

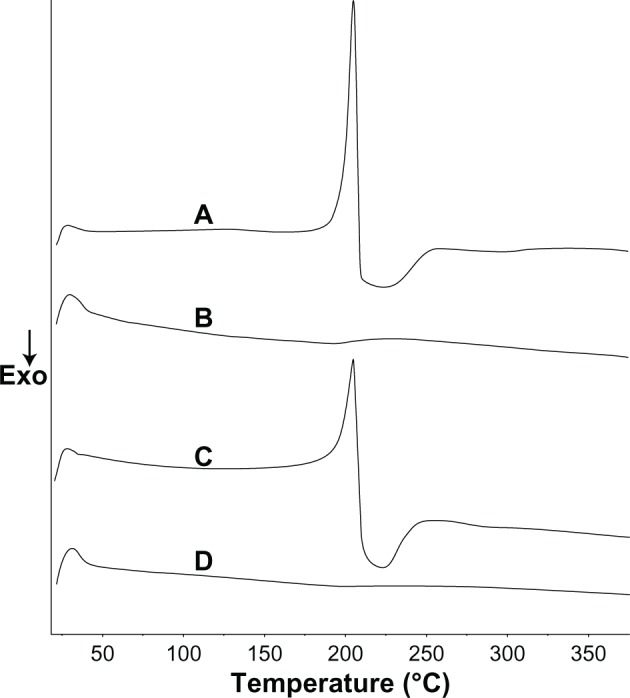

The DSC results of TSIIA, silica nanoparticles, PMs, and SDs consisting of TSIIA/silica nanoparticles at a ratio of 1:5 are shown in Figure 3. Pure TSIIA (Figure 3A) showed a sharp melting peak at an onset temperature of 205.6°C, which indicated its crystalline nature. Observations similar to ours have been reported by Li et al.54 The DSC spectra of PMs (Figure 3C) showed that the endothermic peak of the drug was found at 205.6°C, which indicated no interaction between TSIIA and silica nanoparticles in the PMs and that TSIIA existed in a virgin form in the system. DSC of the SDs prepared at a TSIIA/silica nanoparticle ratio of 1:5 (Figure 3D) showed that the characteristic peak of TSIIA had completely vanished, which suggested that the drug may have been present in the SDs in an amorphous state, and thus was responsible for increasing the dissolution of the drug.

Figure 3.

Differential scanning calorimetry curves of pure TSIIA (A), silica nanoparticles (B), and PMs (C) and SDs prepared at a TSIIA/silica nanoparticles ratio of 1:5 (D).

Abbreviations: Exo, exothermic direction; PMs, physical mixtures; SDs, solid dispersions; TSIIA, tanshi-none IIA.

XRPD

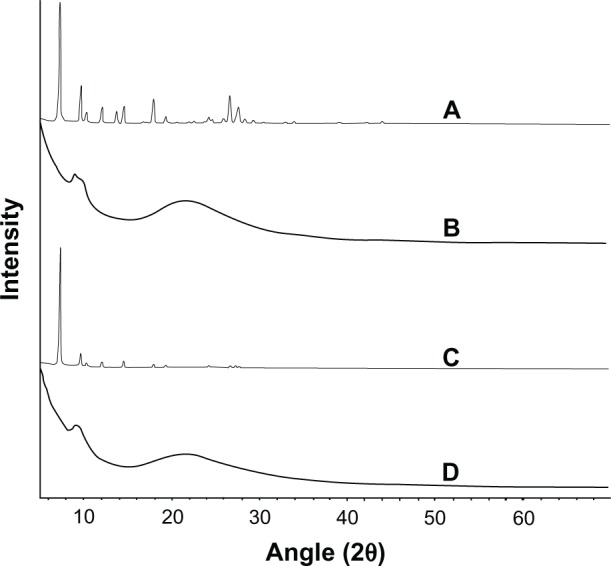

The results of XRPD studies of TSIIA, silica nanoparticles, PMs, and SDs prepared at a TSIIA/silica nanoparticle ratio of 1:5 are shown in Figure 4. Pure TSIIA was characterized by prominent diffraction peaks in the 2θ angle range of 5°–30° in XRPD (Figure 4A). A broad peak centered at the 2θ angle of 22° was observed within the silica nanoparticle spectra due to its amorphous nature (Figure 4B).55 All the major characteristic crystalline peaks of TSIIA were clearly observed in the PMs diffractograms. However, for the SDs, the discriminatory peaks of TSIIA were clearly abolished which indicated that TSIIA might exist in an amorphous state, which is consistent with the DSC results.

Figure 4.

The X-ray powder diffractograms of TSIIA (A), silica nanoparticles (B) and PMs (C) and SDs with a TSIIA/silica nanoparticle ratio of 1:5 (w/w) (D).

Abbreviations: PMs, physical mixtures; SDs, solid dispersions; TSIIA, tanshinone IIA; w/w, weight by weight.

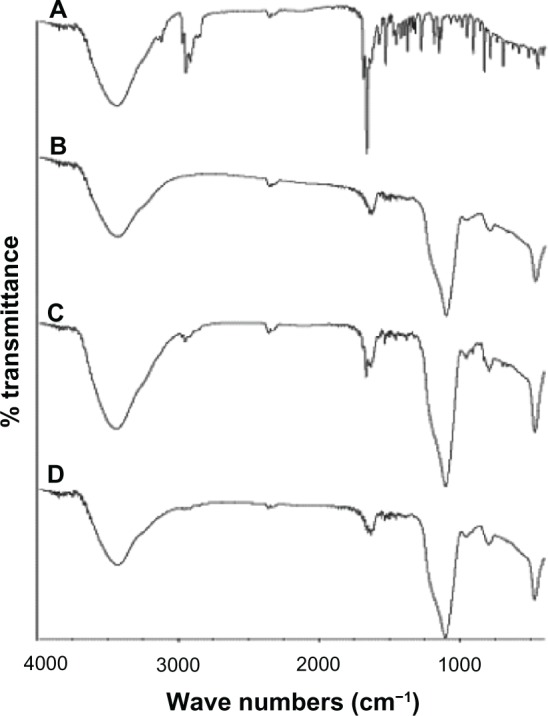

FTIR

Interactions between TSIIA and silica nanoparticles in the SDs were evaluated with FTIR. The spectra of TSIIA, silica nanoparticles, PMs, and SDs are shown in Figure 5. No differences were found between spectra of the PMs and SDs. It can be postulated that only weak van der Waals or hydrogen forces are involved in binding TSIIA onto silica nanoparticles.56

Figure 5.

The IR spectra of TSIIA (A), silica nanoparticles (B) and PMs (C) and SDs with a TSIIA/silica nanoparticle ratio of 1:5 (w/w) (D).

Abbreviations: IR, infrared; PMs, physical mixtures; SDs, solid dispersions; TSIIA, tanshinone IIA; w/w, weight by weight.

Stability test

It is well established that amorphous drugs formulated in the form of SDs tend to recrystallize upon storage. Thus, in the present study, the stability of the SDs was estimated by examining the drug content and in vitro dissolution studies under storage conditions of 75% RH and 40°C for 6 months. The drug content in SDs prepared at a TSIIA/silica nanoparticle ratio of 1:5 was remarkably unchanged (Table 1). The dissolution (60 minutes) of TSIIA from SDs stored for 6 months was slightly reduced compared to that of TSIIA from freshly prepared samples. These results confirmed that silica nanoparticles exhibited a strong stabilization effect on amorphous TSIIA in SDs under severe conditions. This may be because of an interaction between the drug and carriers, and the adsorption on the surface of the amorphous silica nanoparticles, which have been extensively described in the literature.39

Table 1.

Stability test of SDs

| Samples | 0 months

|

6 months

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug content (%) | Dissolution rate (%) (1 h) | Drug content (%) | Dissolution rate (%) (1 h) | |

| 1:5 SDs | 16.52 ± 0.23 | 92.10 ± 1.94 | 16.19 ± 0.73 | 89.64 ± 1.87 |

Abbreviations: h, hours; SDs, solid dispersions.

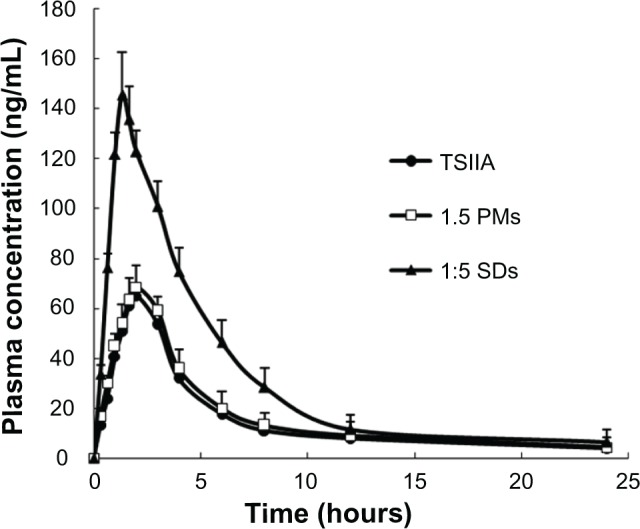

Plasma concentration-time curve and relative bioavailability

Under the analytical conditions, no endogenous peaks that interfered with TSIIA or loratadine (internal standard) were observed. In addition, the TSIIA peaks could be well distinguished from the loratadine peaks without any interference. Linearity was observed in concentrations of TSIIA within the 8–800 ng/mL range with correlation coefficients of over 0.99 (a typical calibration curve: y = 8.4706x + 5.7152, [r = 0.9976, n = 3]). The limit of quantification was 10 ng/mL. Intra- and interday precisions were below 7%, and the extraction recovery of TSIIA from rat plasma (n = 9) was 80.96% ± 3.82%. The plasma concentration-time curves of TSIIA after oral administration are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The mean plasma concentration-time curve of TSIIA in rats after oral administration of SDs, PMs, and TSIIA equivalent to 60 mg kg−1 of TSIIA (n = 6).

Notes: The values are represented as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 6/group/time point).

Abbreviations: PMs, physical mixtures; SDs, solid dispersions; TSIIA tanshi-none IIA.

The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated and are shown in Table 2. The AUC from 0 to 24 hours (AUC0–24h) of pure TSIIA and SDs was 379.50 and 862.47, respectively, which yielded a relative bioavailability of 227.3%. The Cmax of the SDs was 152.34 ng/mL, which was a 2.1-fold greater than that of TSIIA. Compared to TSIIA, the SDs had a significantly lower Tmax (P < 0.01), where SDs < TSIIA. This result shows that the TSIIA in the SDs exhibited a faster absorption rate and higher bioavailability, which may be attributed to several characteristics, including that SDs with silica nanoparticles as carriers can strongly potentiate their dissolution and increase the contact area with the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in an accelerated absorption rate and improved bioavailability.57,58 In addition, coexistence of both the carrier and TSIIA in the PMs by physical mixing showed a slightly faster absorption rate and a higher bioavailability, which is potentially a result of the slight improvement in drug release.

Table 2.

The main pharmacokinetic parameters of TSIIA after oral administration of TSIIA, PMs or SDs in rats (n = 6) at a dose of 60 mg/kg

| Parameters | Pure TSIIA | PMs | SDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax(h) | 2.56 ± 0.447 | 2.39 ± 0.495 | 1.58 ± 0.325* |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 72.78 ± 6.593 | 76.1 ± 8.169 | 152.34 ± 16.281* |

| t1/2(h) | 4.38 ± 0.758 | 4.20 ± 0.726 | 3.75 ± 0.533 |

| AUC0–t (h ng/mL) | 379.50 ± 58.942 | 398.85 ± 66.538 | 862.47 ± 81.594* |

| AUC0–⊥ (h ng/mL) | 416.69 ± 62.439 | 439.63 ± 70.145 | 914.79 ± 94.175* |

| Relative bioavailability(%) | – | 105.1 | 227.3 |

Notes: Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviations (n = 6);

P < 0.01 versus 60 mg/kg TSIIA.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the plasma concentration-time curve; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; h, hours; PMs, physical mixtures; SDs, solid dispersions; t1/2, half-life; Tmax, time to reach Cmax; TSIIA, tanshinone IIA.

In this study, silica nanoparticles, which were used as drug carriers in SDs, showed a high specific surface area and hydrophilic properties, which impart unique advantages that improve their bioavailability. Silica is abundantly distributed in nature, it has good compatibility, and is deemed “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).59 Importantly, the fabrication of silica nanoparticles is simple, scalable, cost-effective, and controllable, and silica nanoparticles have been previously produced on an industrial scale as additives for cosmetics, drugs, printer toners, varnishes, and food. Furthermore, silica nanoparticles are currently being developed for a host of biomedical and biotechnological applications such as DNA transfection, drug delivery, and enzyme immobilization.60–62

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully prepared SDs consisting of TSIIA and silica nanoparticles using the spray-drying method. Both the drug dissolution behavior and oral bioavailability of TSIIA were largely improved by formulating the drug as a SD. In addition, the SDs of TSIIA had excellent stability. Thus, we conclude that silica nanoparticles have practical value as a novel and promising carrier for SDs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Open Fund of Key Laboratory of New Drug Delivery System of Chinese Materia Medica (2011NDDCM01001).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Wang P, Wu X, Bao Y, et al. TSIIA prevents cardiac remodeling through attenuating NAD (P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species production in hypertensive rats. Pharmazie. 2011;66(7):517–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun DD, Wang HC, Wang XB, et al. Tanshinone IIA: a new activator of human cardiac KCNQ1/KCNE1 (I(Ks)) potassium channels. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;590(1–3):317–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao J, Yang G, Pi R, et al. Tanshinone IIA protects neonatal rat cardiomyocytes from adriamycin-induced apoptosis. Transl Res. 2008;151(2):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu J, Huang H, Liu J, Pi R, Chen J, Liu P. TSIIA protects cardiac myocytes against oxidative stress-triggered damage and apoptosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;568(1–3):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hao H, Wang G, Cui N, Li J, Xie L, Ding Z. Pharmacokinetics, absorption and tissue distribution of tanshinone IIA solid dispersion. Planta Med. 2006;72(14):1311–1317. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-951698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Wang G, Li P, Hao H. Simultaneous determination of tanshinone IIA and cryptotanshinone in rat plasma by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;826(1–2):26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu H, Subedi RK, Nepal PR, et al. Enhancement of solubility and dissolution rate of cryptotanshinone, tanshinone I and tanshinone IIA extracted from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Arch Pharm Res. 2012;35(8):1457–1464. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-0816-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu XY, Lin SG, Zhou ZW, et al. Role of P-glycoprotein in the intestinal absorption of tanshinone IIA, a major active ingredient in the root of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge. Curr Drug Metab. 2007;8(4):325–340. doi: 10.2174/138920007780655450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao SJ, Hou SX, Liang Z, et al. Ion-pair reversed-phase HPLC: assay validation of sodium IIA sulfonate in mouse plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2006;831(1–2):163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Jiang X, Xu W, Li C. Complexation of tanshinone IIA with 2- hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin: effect on aqueous solubility, dissolution rate, and intestinal absorption behavior in rats. Int J Pharm. 2007;341(1–2):58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasconcelos T, Sarmento B, Costa P. Solid dispersions as strategy to improve oral bioavailability of poor water soluble drugs. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12(23–24):1068–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lennernäs H, Abrahamsson B. The use of biopharmaceutic classification of drugs in drug discovery and development: current status and future extension. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2005;57(3):273–285. doi: 10.1211/0022357055263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leuner C, Dressman J. Improving drug solubility for oral delivery using solid dispersions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Streubel A, Siepmann J, Bodmeier R. Drug delivery to the upper small intestine window using gastroretentive technologies. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(5):501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka N, Imai K, Okimoto K, et al. Development of novel sustained-release system, disintegration-controlled matrix tablet (DCMT) with solid dispersion granules of nilvadipine (II): in vivo evaluation. J Control Release. 2006;112(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi F, Zhao JH, Liu Y, Wang Z, Zhang YT, Feng NP. Preparation and characterization of solid lipid nanoparticles loaded with frankincense and myrrh oil. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:2033–2043. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S30085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashanian S, Azandaryani AH, Derakhshandeh K. New surface-modified solid lipid nanoparticles using N-glutaryl phosphatidylethanolamine as the outer shell. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2393–2401. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S20849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Liu P, Liu JP, Zhang WL, Yang JK, Fan YQ. Novel Tanshinone IIA ternary solid dispersion pellets prepared by a single-step technique: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;80(2):426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parmar Komal R, Satapara Vijay P, Shah Sunny R, Sheth Navin R. Improvement of dissolution properties of lamotrigine by inclusion complexation and solid dispersion technique. Pharmazie. 2011;66(2):119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim MS, Kim JS, Park HJ, Cho WK, Cha KH, Hwang SJ. Enhanced bioavailability of sirolimus via preparation of solid dispersion nanoparticles using a supercritical antisolvent process. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2997–3009. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S26546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Löbenberg R, Amidon GL. Modern bioavailability, bioequivalence and biopharmaceutics classification system: New scientific approaches to international regulatory standards. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Junghanns JU, Müller RH. Nanocrystal technology, drug delivery and clinical applications. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3(3):295–309. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bikiaris D, Papageorgiou GZ, Stergiou A, et al. Physicochemical studies on solid dispersions of poorly water-soluble drugs: evaluation of capabilities and limitations of thermal analysis techniques. Thermochim Acta. 2005;439(1–2):58–67. [Google Scholar]

- 24.He XQ, Pei LX, Tong HH, Zheng Y. Comparison of spray freeze drying and the solvent evaporation method for preparing solid dispersions of baicalein with Pluronic F68 to improve dissolution and oral bioavailability. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2011;12(1):104–113. doi: 10.1208/s12249-010-9560-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karavas E, Ktistis G, Xenakis A, Georgarakis E. Effect of hydrogen bonding interactions on the release mechanism of felodipine from nanodispersions with polyvinylpyrrolidone. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2006;63(2):103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pokharkar VB, Mandpe LP, Padamwar MN, Ambike AA, Mahadik KR, Paradkar A. Development, characterization and stabilization of amorphous form of a low Tg drug. Powder Technol. 2006;167(1):20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang C, Xu X, Wang J, An Z. Use of the co-grinding method to enhance the dissolution behavior of a poorly water-soluble drug: generation of solvent-free drug-polymer solid dispersions. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2012;60(7):837–845. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c12-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolašinac N, Kachrimanis K, Homšek I, Grujić B, Durić Z, Ibrić S. Solubility enhancement of desloratadine by solid dispersion in poloxamers. Int J Pharm. 2012;436(1–2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bley H, Fussnegger B, Bodmeier R. Characterization and stability of solid dispersions based on PEG/polymer blends. Int J Pharm. 2010;390(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X, Liu X, Gan L, Zhou C, Mo J. Preparation and physicochemical characterizations of tanshinone IIA solid dispersion. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34(6):949–959. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jondhale S, Bhise S, Pore Y. Physicochemical investigations and stability studies of amorphous gliclazide. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2012;13(2):448–459. doi: 10.1208/s12249-012-9760-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellaerts R, Mols R, Jammaer JA, et al. Increasing the oral bioavailability of the poorly water soluble drug itraconazole with ordered mesoporous silica. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;69(1):223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeuchi H, Nagira S, Yamamoto H, Kawashima Y. Solid dispersion particles of amorphous indomethacin with fine porous silica particles by using spray-drying method. Int J Pharm. 2005;293(1–2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeuchi H, Nagira S, Tanimura S, Yamamoto H, Kawashima Y. Tabletting of solid dispersion particles consisting of indomethacin and porous silica particles. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2005;53(5):487–491. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeuchi H, Handa T, Kawashima Y. Spherical solid dispersion containing amorphous tolbutamide embedded in enteric coating polymers or colloidal silica prepared by spray-drying technique. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1987;35(9):3800–3806. doi: 10.1248/cpb.35.3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monkhouse DC, Lach JL. Use of adsorbents in enhancement of drug dissolution. II. J Pharm Sci. 1972;61(9):1435–1441. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600610918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chauhan B, Shimpi S, Paradkar A. Preparation and evaluation of glibenclamide-polyglycolized glycerides solid dispersions with silicon dioxide by spray drying technique. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2005;26(2):219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen B, Wang Z, Quan G, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of ordered mesoporous silica as a novel adsorbent in liquisolid formulation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:199–209. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S26763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du X, He J. Spherical silica micro/nanomaterials with hierarchical structures: synthesis and applications. Nanoscale. 2011;3(10):3984–4002. doi: 10.1039/c1nr10660k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao X, Deng WW, Fu M, et al. In vitro release and in vitro-in vivo correlation for silybin meglumine incorporated into hollow-type mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:753–762. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S28348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galagudza MM, Korolev DV, Sonin DL, et al. Targeted drug delivery into reversibly injured myocardium with silica nanoparticles: surface functionalization, natural biodistribution, and acute toxicity. Int J Nanomedicine. 2010;5:231–237. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s8719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corbalan JJ, Medina C, Jacoby A, Malinski T, Radomski MW. Amorphous silica nanoparticles aggregate human platelets: potential implications for vascular homeostasis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:631–639. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S28293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galagudza M, Korolev D, Postnov V, et al. Passive targeting of ischemic-reperfused myocardium with adenosine-loaded silica nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:1671–1678. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tho I, Liepold B, Rosenberg J, Maegerlein M, Brandl M, Fricker G. Formation of nano/micro-dispersions with improved dissolution properties upon dispersion of ritonavir melt extrudate in aqueous media. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;40(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang L, Cui FD, Sunada H. Preparation and evaluation of solid dispersions of nitrendipine prepared with fine silica particles using the melt-mixing method. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2006;54(1):37–43. doi: 10.1248/cpb.54.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yassin AE, Alanazi FK, El-Badry M, Alsarra IA, Barakat NS, Alanazi FK. Preparation and characterization of spironolactone-loaded gelucire microparticles using spray-drying technique. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2009;35(3):297–304. doi: 10.1080/03639040802302157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Eerdenbrugh B, Van Speybroeck M, Mols R, et al. Itraconazole/TPGS/Aerosil200 solid dispersions: characterization, physical stability and in vivo performance. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2009;38(3):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim MS, Kim JS, Park HJ, Cho WK, Cha KH, Hwang SJ. Enhanced bioavailability of sirolimus via preparation of solid dispersion nanoparticles using a supercritical antisolvent process. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2997–3009. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S26546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guedes FL, de Oliveira BG, Hernandes MZ, et al. Solid dispersions of imidazolidinedione by PEG and PVP polymers with potential antischistosomal activities. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2011;12(1):401–410. doi: 10.1208/s12249-010-9556-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jondhale S, Bhise S, Pore Y. Physicochemical investigations and stability studies of amorphous gliclazide. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2012;13(2):448–459. doi: 10.1208/s12249-012-9760-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vippagunta SR, Maul KA, Tallavajhala S, Grant DJ. Solid state characterization of nifedipine solid dispersions. Int J Pharm. 2002;236(1–2):111–123. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawabata Y, Yamamoto K, Debari K, Onoue S, Yamada S. Novel crystalline solid dispersion of tranilast with high photostability and improved oral bioavailability. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;39(4):256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Junghanns JU, Müller RH. Nanocrystal technology, drug delivery and clinical applications. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3(3):295–309. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li J, Liu P, Liu JP, Zhang WL, Yang JK, Fan YQ. Novel Tanshinone IIA ternary solid dispersion pellets prepared by a single-step technique: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;80(2):426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang L, Lu A, Wang C, Zheng X, Zhao D, Liu R. Nano-fibriform production of silica from natural chrysotile. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2006;295(2):436–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Planinšek O, Kovačič B, Vrečer F. Carvedilol dissolution improvement by preparation of solid dispersions with porous silica. Int J Pharm. 2011;406(1–2):41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leuner C, Dressman J. Improving drug solubility for oral delivery using solid dispersions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu KL, Cao S, Hu FQ, Feng JF. Enhanced oral bioavailability of docetaxel by lecithin nanoparticles: preparation, in vitro, and in vivo evaluation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:3537–3545. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S32880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang F, Li L, Chen D. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: synthesis, biocompatibility and drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2012;24(12):1504–1534. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Falahati M, Saboury AA, Ma’mani L, Shafiee A, Rafieepour HA. The effect of functionalization of mesoporous silica nanoparticles on the interaction and stability of confined enzyme. Int J Biol Macromol. 2012;50(4):1048–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galagudza M, Korolev D, Postnov V, et al. Passive targeting of ischemic-reperfused myocardium with adenosine-loaded silica nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:1671–1678. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheang TY, Tang B, Xu AW, et al. Promising plasmid DNA vector based on APTES-modified silica nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:1061–1067. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S28267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]