Abstract

Background

Performance measures that reward achieving blood pressure (BP) thresholds may contribute to overtreatment. We developed a tightly-linked clinical action measure designed to encourage appropriate medical management; and a marker of potential overtreatment, designed to monitor overly aggressive treatment in the face of low diastolic BP.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in 879 Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers and smaller community based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). The clinical action measure for hypertension was met if the patient had a passing index BP at the visit or had an appropriate action. We examined the rate of passing the action measure and of potential overtreatment in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) during 2009-2010.

Results

There were 977,282 established VA patients, ages 18 years and older, with diabetes. 713,790 patients were eligible for the action measure. 94% passed the measure: 82% because they had a BP<140/90 at the visit; and an additional 12% with BP>140/90 and appropriate clinical actions. Facility pass rates varied from 77% to 99% (p<0.001). Among all diabetics, 197,291 (20%) had a BP<130/65; of these, 80,903 (8% of all diabetics) had potential overtreatment. Facility rates of potential overtreatment varied from 3% to 20% (p<0.001). Facilities with higher rates of meeting the current threshold measure (<140/90 mm Hg) had higher rates of potential overtreatment (p<0.001).

Conclusions

While 94% of diabetic Veterans met the action measure, rates of potential overtreatment are currently approaching the rate of undertreatment and high rates of achieving current threshold measures are directly associated with overtreatment. Implementing a clinical action measure for hypertension management, as VHA is planning to do, may result in more appropriate care and less overtreatment.

Over the past decade there has been significant improvement in control of cardiovascular risk factors (lipids, blood pressure (BP)) among patients with diabetes.1-4 This improvement has been driven at least partly by performance measurement that focused on attainment of specific risk factor thresholds.5-7 However, current dichotomous threshold measures suggest that the majority of patients should fall below a certain target risk factor level (e.g., BP <140/90 mm Hg), regardless of underlying cardiovascular risk, patient preferences, intensity of treatment, underlying disease severity, or regimen adherence.7-11

Yet, the evidence does not fully support the “treat to target” approach implied in current performance measures. Most RCTs provide causal evidence for the benefit of treatment (e.g., a BP medication, or statin) and not a particular threshold risk factor level achieved in the intervention group; dichotomous threshold measures, however, are silent on the manner of achieving risk factor control.12-15 Consequently, such measures can promote overtreatment and diastolic hypotension,16 which has been shown in multiple studies to be associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes.17-19 ”Tightly linked” clinical action measures, so named because the process specified by the measure is strongly tied to the evidence, have advantages over current dichotomous threshold measures,20-23 because they better capture the complexity of clinical decision making for hypertension.24, 25 Specifically, clinical action measures focus not only on the risk factor level but also give credit when patients are receiving evidence-based treatment even when a risk factor threshold is not achieved. They also diminish the potential for overtreatment and unintended consequences by taking contraindications and variability of measurement into account. Finally, they examine care and risk factor control over time, rather than only on one day.

In May 2006, over 40 scientific and clinical experts in diabetes and quality measurement gathered at a federally-sponsored multidisciplinary conference on diabetes quality measurement.26 Among the conclusions was the promotion of “tightly-linked” clinical action measures to assess whether appropriate action was taken in response to substandard risk factor control, particularly for BP and lipids. Such clinical action measures have also been endorsed recently by other expert panels.7,27

We collaborated with clinical and operations leaders in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to specify a clinical action measure for BP management in diabetes. We further specified a marker of potential hypertension overtreatment, to assess the proportion of patients who may be receiving overly aggressive and thus potentially risky treatment. We then examined performance on the measure and on the marker of potential overtreatment among almost 1 million patients with diabetes receiving primary care in VA during 2009-2010 to assess what proportion of patients are meeting appropriate quality for hypertension, the degree of potential hypertension overtreatment, and the relationship between meeting current threshold measures and potential overtreatment.

Methods

Measure Development

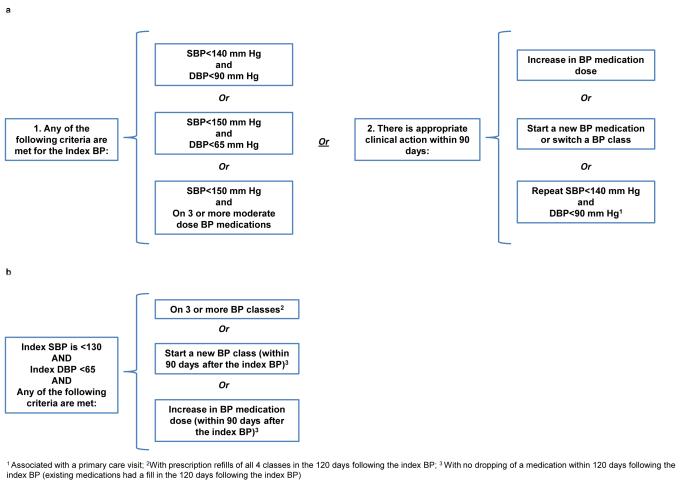

We specified the tightly-linked clinical action measure for hypertension management in diabetes with assistance from experts in diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and measurement construction. The measure was designed to acknowledge several tenets of evidence for BP management in diabetes. First, BP control clearly benefits patients with diabetes but current recommendations about stringent BP targets for diabetes (e.g., BP <130/80) are based on observational analyses of clinical trials,14, 15 and no experimental evidence currently supports a systolic BP (SBP) target of less than 140 mm Hg.28, 29 Even in clinical trials that showed improved macrovascular outcomes with stringent (diastolic BP (DBP) <80 or 85) versus less stringent control,30, 31 the achieved mean DBP was always higher than 80 mm Hg.15 Second, a recent RCT found that randomizing patients with diabetes to stringent control (SBP <120) versus moderate control (SBP <140) achieved no clinical benefit and increased adverse drug events,32 while follow-up of patients from another trial found that those who maintained tight BP control (SBP<130) did not have improved outcomes, and may have had higher mortality, than those who maintained average control (SBP130-140).33 Third, clinical trials have rarely used more than 3-4 antihypertensive medications to achieve control.34 Fourth, several analyses have shown that low DBP levels (e.g., <70) increase cardiovascular events among patients with diabetes or cardiovascular disease, and that those with ischemic heart disease (IHD) may be at greatest risk due to coronary hypoperfusion.17, 19, 28, 35 We therefore specified that appropriate quality for hypertension management among patients with diabetes could be met if the patient’s BP was less than 140/90 mm Hg or if the patient received appropriate care, as defined below and in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Tightly-linked Clinical Action Measure and the Marker of Potential Overtreatment among Patients with Diabetes

a. The clinical action measure is met for patients (18-75 years old) when:

b: The marker of potential overtreament is met for patients (18+ years old) when:

Similarly, with guidance from our workgroup, we specified a marker of potential hypertension overtreatment (Figure 1) that could signal which patients may be getting therapy that is not beneficial to them (and could be costly or even harmful) and therefore could benefit from medication de-escalation. Given that no experimental evidence supports a SBP less than 140 and that in the ACCORD trial patients randomized to intensive SBP control, with a mean antihypertensive medication number of 3.4, had higher likelihood of serious adverse events32, and that diastolic levels of <70 have been associated with harm, the marker of potential overtreatment focused on patients who had both low systolic (<130) and low diastolic (<65) values and were on 3 or more antihypertensive medications and/or were being actively intensified.

Cohort and Measure Construction

We used the VA National Central Data Warehouse to construct the cohort and measures (eMethods 1). The cohort included established active primary care patients 18 or older with a diagnosis of diabetes in the 24 months prior to the eligibility month. The eligibility month was the month during which the index BP (defined as the lowest DBP and lowest SBP measurements from the same day as the patient’s last primary care visit during the measurement period) occurred. The measurement period was from July 1, 2009 to June 30, 2010. All VA clinics where primary care type services are delivered were included.

An eligible patient age 18-75 was determined to have appropriate care if the index SBP was less than 140 and the DBP was less than 90; or if the index SBP was less than 150 and the DBP was less than 65; or if the index SBP was less than 150 and the patient was on 3 or more moderate dose antihypertensive medications (eMethods 2) or if appropriate action occurred within 90 days (Figure 1). Similarly, a patient in the cohort was considered to have received possible overtreatment if their index SBP was less than 130 and DBP was less than 65 and they were receiving 3 or more BP medications and/or active medication intensification (Figure 1).

Analysis

In our population, patients were cared for at 879 different sites of care, ranging from small community based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) to large medical centers and thus our data is clustered hierarchically by site. We used a two level hierarchical multivariate logistic regression to estimate the rate of meeting the clinical action measure. The dependent variable was measured at the patient level as were individual patient characteristics (gender and presence of IHD). An indicator representing each site of care was used to identify the second level in the regression allowing us to estimate the variance of the constant term. This model accounts appropriately for the varying number of patients seen at any given site of care in generating site specific rates and allows us to accurately estimate the variance in rates across sites. The predicted rates are empirical Bayes estimates which account for the instability of the estimates for small sites. 36 All models were estimated using the xtmelogit procedure in Stata 12.0 (Stata, College Station, Texas, 2010).

Similarly, we calculated the proportion of all patients, and those patients over 75, who received potential overtreatment and the reasons for overtreatment. We then examined associations between individual patient characteristics (age, gender, and IHD) and potential overtreatment. Using two level hierarchical logistic regression models, we examined the predicted rates of overtreatment across all sites of care. Finally, we constructed a two level hierarchical multivariate logistic regression model that simultaneously examined 2 risk factors for worse outcomes of overtreatment: age and IHD. We examined predicted rates of overtreatment of younger (age 55) and older (age 80) patients, with and without IHD, for sites at the median rate of overtreatment in order to demonstrate the range and variability in overtreatment by characteristics known to be associated with worse outcomes from diastolic hypotension.

We divided the 879 sites into quartiles based on meeting the current dichotomous threshold performance measure of BP <140/90 mm Hg and examined the association between facility quartile and potential overtreatment using a multilevel logistic model. Finally, we examined what proportion of facilities in each quartile were also in the highest quartile of overtreatment.

We received IRB approval for the study from VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System’s Subcommittee on Human Studies.

Results

Table 1 describes the entire diabetes cohort as well as the cohort limited to ages 18-75, for whom the clinical action measure was applied.

Table1.

Characteristics of diabetes cohorts

| Entire Diabetes Cohort (18+ years old) |

Cohort for Action Measure (18-75 years old only) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Value | Sample, n | Value | Sample, n |

| N | 977,282 | 713,790 | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 67.6 (10.9) | 977,282 | 62.5 (7.8) | 713,790 |

| Male, % | 97 | 946,780 | 96 | 686,528 |

| Index systolic blood pressure, mean (SD)1 | 128.3 (15.1) | 977,282 | 128.2 (14.9) | 713,790 |

| Index diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD)1 | 71.1 (10.6) | 977,282 | 72.8 (10.3) | 713,790 |

| Index diastolic blood pressure<65 (mm Hg), %1 |

28 | 268,392 | 21 | 152,090 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%), mean (SD)2 | 7.2 (1.4) | 876,656 | 7.3 (1.5) | 655,677 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean (SD)2 |

132.3 (14.2) | 899,722 | 131.8 (13.9) | 662,755 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg), mean (SD)2 |

73.2 (9.6) | 899,722 | 75.0 (9.3) | 662,755 |

| Ischemic heart disease diagnosis, %2 | 28 | 274,253 | 25 | 178,565 |

| Classes of antihypertensive medications, mean (SD)3 |

1.7 (1.4) | 977,282 | 1.7 (1.4) | 713,790 |

| On 3 or more hypertension medications, %3 | 28 | 274,409 | 28 | 198,548 |

| On 4 or more hypertension medications, %3 | 11 | 110,113 | 11 | 80,627 |

The index systolic/diastolic blood pressure is the lowest systolic/diastolic blood pressure value measured on the same day as the last primary care visit occurring during the measurement period

Time period examined: 365 days prior to the index BP

Time period examined: 100 days prior to the index BP

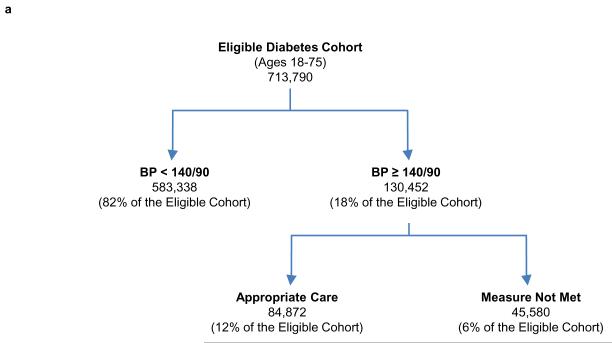

Clinical Action Measure

Among diabetic patients 18-75, 94% passed the measure (Figure 2a). Reasons for passing the measure are detailed in Table 2. 82% had an index BP <140/90. An additional 8% met the measure by having BP medication intensification. Although 21% of patients had BP <150/65, the majority of these patients met the measure on the basis of a BP <140/90. Men were slightly more likely to meet the measure than women (94% vs. 93%; p<.001) as were patients with IHD versus those without (95% vs. 93%; p<.001). There was moderate variation across the 879 facilities in predicted probability of meeting the measure, ranging from 77% (CI:69%-83%) to 99% (CI:97%-99%) (p<0.001).

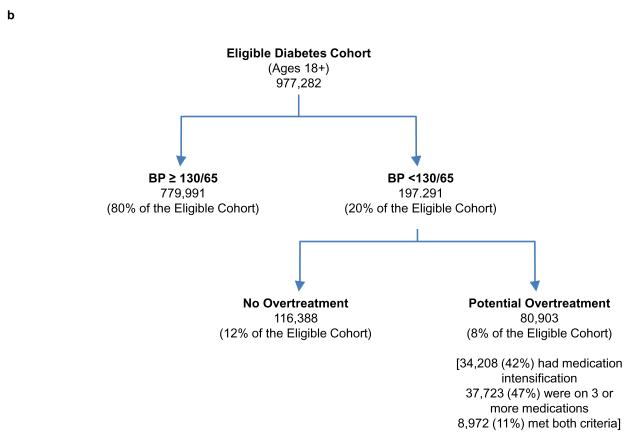

Figure 2.

Patients Meeting the Clinical Action Measure or the Marker of Potential Overtreatment

a. Quality of care by the linked action measure is met in 94% of patients

b. 8% patients with diabetes have potential hypertension overtreatment

Table 2.

Reasons for passing the clinical action measure for hypertension management among diabetic patients age 18-75 (N= 713,790)

| Hierarchical* | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason | % | N | % | N |

| Index SBP<140 and DBP<90 | 82 | 583,338 | 82 | 583,338 |

| Index SBP<150 and DBP<65 | 1 | 5,946 | 21 | 149,497 |

| Index SBP<150 and on ≥3 moderate dose BP medications |

2 | 13,725 | 15 | 105,813 |

| Appropriate clinical action within 90 days | ||||

| Increase dose of existing BP medication, start a new BP medication, or switch BP classes |

8 | 56,985 | 33 | 233,255 |

| Repeat SBP<140 and DBP<90 | 1 | 8,216 | 21 | 149,290 |

| MEETS THE CLINICAL ACTION MEASURE | 94 | 668,210 | 94 | 668,210 |

| DOES NOT MEET THE MEASURE | 6 | 45,580 | 6 | 45,580 |

Patient can meet the measure based on only one reason, in the order listed

Marker of Potential Overtreatment

In the entire cohort age 18 and older, 197,291 (20%) had a BP <130/65; of these, 80,903 (over 8% of the entire cohort) were potentially overtreated (Figure 2b). Among patients who were potentially overtreated, the mean SBP was 114.5 mm Hg and the mean DBP was 57.6 mm Hg. Table 3 shows that patients with potential overtreatment are older, have lower mean index BP, and are more likely to be men and have ischemic heart disease. Indeed, among the 263,492 patients 76 and older, 30% had a BP <130/65 and 40% of those with a BP <130/65 were potentially overtreated (12% of all diabetes patients 76 and older). In multivariate analysis, the effect of age and presence of IHD continued to be independent predictors of overtreatment (data not shown).

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients without overtreatment and with potential overtreatment

| No Overtreatment |

Potential Overtreatment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Medication Intensification |

On 3 or more medications |

Met both criteria |

Overall | |

| Sample, n | 896,379 | 34,208 | 37,723 | 8,972 | 80,903 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 67.2 (10.9) | 72.1 (10.2) | 71.6 (9.4) | 71.5 (9.2) | 71.8 (9.7) |

| Male, % | 97 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 98 |

| Index systolic blood pressure, mean (SD) 1 |

129.6 (14.9) | 114.3 (10.6) | 114.6 (10.5) | 114.8 (10.7) |

114.5 (10.6) |

| Index diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD) 1 |

72.3 (10.1) | 57.9 (5.4) | 57.5 (5.4) | 57.2 (5.7) | 57.6 (5.5) |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%), mean (SD)2 |

7.2 (1.4) | 7.1 (1.3) | 7.1 (1.2) | 7.2 (1.3) | 7.1 (1.3) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD)2 |

132.7 (14.1) | 126.8 (13.8) | 128.0 (13.7) | 129.2 (14.5) |

127.6 (13.9) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD)2 |

73.8 (9.5) | 66.6 (8.6) | 66.1 (8.3) | 66.0 (8.5) | 66.3 (8.4) |

| Ischemic heart disease diagnosis, %2 |

27 | 40 | 46 | 51 | 44 |

The index systolic/diastolic blood pressure is the lowest systolic/diastolic blood pressure value measured on the same day as the last primary care visit occurring during the measurement period

Time period examined: 365 days prior to the index BP

Predicted probability of overtreatment for those 18 and older varied by facility from 3% (CI:2%-5%) to 20% (CI:17%-22%). Predicted probabilities using a 2 level model showed that a 55 year old without IHD had a predicted probability of overtreatment of 3.8% (CI:3.7%-3.9%) while an 80 year old with IHD had a predicted probability of overtreatment of 15.3% (CI:14.9%-15.7%).

Association between current performance measures and overtreatment

Table 4 shows a dose-response relationship between facility quartile of meeting the current dichotomous measure (BP <140/90) and potential overtreatment. Facilities in the lowest quartile of meeting the measure had a predicted overtreatment rate of 6.0% (CI:5.7%-6.3%) while those in the highest quartile had a potential overtreatment rate of 8.6% (CI:8.1%-9.0%). Further, facilities in the highest quartile of meeting the <140/90 mm Hg measure were 3.7 times more likely to be ranked in the top quartile of potential overtreatment relative to facilities in the lowest quartile.

Table 4.

Relationship between the proportion of diabetic patients per facility meeting the current BP <140/90 mm Hg threshold performance measure and potential overtreatment1

| Proportion of patients per facility meeting the BP <140/90 threshold measures, by quartile |

Predicted probability (CI) of potential overtreatment2 |

Proportion (N) of facilities that are in the highest quartile of potential overtreatment3 |

|---|---|---|

| Lowest quartile (53%-78%) | 6% (5.7-6.3) | 12% (26) |

| Second (79%-82%) | 7% (6.7-7.4) | 16% (36) |

| Third (82%-86%) | 8% (7.6-8.4) | 28% (62) |

| Highest quartile (86%-97%) | 9% (8.1-9.0) | 46% (96) |

Potential overtreatment as defined in Figure 1b

Predicted probability of potential overtreatment per quartile of meeting the current threshold measures, based on multilevel logistic regression for sites at the median rate of potential overtreatment (p<0.001).

The proportion in the top quartile of potential overtreatment increases for each successive quartile of meeting the current threshold measure (Kappa 0.29; p<0.0001)

Discussion

Nearly 94% of diabetic patients met the clinical action measure for BP measurement (82% had a BP <140/90 and an additional 12% had BP >= 140/90 but appropriate management). This represents a dramatic improvement in BP control over the past decade6 during which time there has also been an intense focus on performance measures, guidelines and quality improvement initiatives related to BP control.37

However, in the past, performance measures for BP control have been silent as to the manner of achieving control. The described clinical action measure captures not only the rate of control, but, also appropriate treatment and contraindications to further intensification. The measure acknowledges that some patients may never achieve target control despite appropriate treatment and gives credit for using evidence-based therapy. Additionally, the measure states that patients with moderate systolic and low diastolic levels meet the measure without additional therapy. In this way, the clinical action measure promotes appropriate treatment without encouraging overtreatment. Finally, the clinical action measure at least partly takes into account variability in BP measurement38 by giving credit for a lower reading within 90 days.

For reasons stated previously, our measure focused on achieving a BP control level of less than 140/90 mm Hg or appropriate management. While patients with high cardiovascular risk could possibly benefit from tighter control, those at lower cardiovascular risk could be harmed or incur additional cost and inconvenience of polypharmacy without substantial benefit.10, 28 There has been considerable effort in VA to have the majority of patients meet a dichotomous threshold measure of 140/90 since 1999, and in 2010 over 80% did so. Consequently, 31% of those with a BP <140/90 in our cohort had a DBP that is less than 65 and 79% of those patients were on at least one antihypertensive medication. Indeed, our results suggest that over 8% of all diabetic Veterans may be overtreated. Older patients and those with ischemic heart disease, who may be at highest risk from hypotension, impaired coronary perfusion, and polypharmacy are also at greater risk for potential overtreatment.

Rates of potential overtreatment varied widely across facilities. Moreover, facilities that were successful in meeting current dichotomous threshold measures of BP <140/90 were more likely to have higher levels of overtreatment. We posit that these findings are not unique for BP threshold measures and that similar or more stringent dichotomous threshold measures for glycated hemoglobin and for low density lipids may pose similar threats to many patients with diabetes.

Our results show that it is possible to construct a sophisticated, clinically meaningful performance measure using electronic data that includes diagnostic codes, vital signs, and prescription information. VA automated data, including pharmacy and vital signs data, has been shown to be reliable compared to data abstracted from the medical record.39, 40 Not all health care systems have ready access to such reliable data elements, but our findings suggest that continuing to promote only dichotomous threshold measures for BP control is no longer optimal and may, in fact, encourage potentially harmful and wasteful overtreatment. The expansion of meaningful use criteria for electronic health records may rectify the lack of available data. Until then, national standard setting groups must insist on better data availability that facilitates the use of more clinically meaningful measures.

While the action measure captured a robust set of criteria, it may still have underestimated the true rate of appropriate care. For example, we were not able to assess medications prescribed outside of VA nor contraindications to treatment other than low diastolic levels. The new ACCF/AHA performance measurement recommendations suggest a measure that can be met for those above threshold who are on 2 or more antihypertensive medications, rather than the 3 moderate dose medications we specified.27 Had we incorporated these criteria, we would have found even higher rates of meeting clinical action.

Unlike the clinical action measure, the marker of potential overtreatment is not yet intended as a performance measure, but rather as a signal that some patients with low BP may be receiving overly aggressive treatment. As such, it could be used in quality improvement initiatives to give feedback to clinicians about patients may benefit from de-escalation of their medications. Some patients identified as potentially overtreated may be receiving multiple medications to treat other conditions like heart failure, and their treatment may thus be appropriate. Further, lack of benefit and possible harm of aggressive treatment for diastolic and systolic BP has not been incorporated in national guidelines and one would expect the number of potentially overtreated to decline if guidelines are modified. However, the fact that there is substantial site-level variation in potential overtreatment and that sites with higher rates of meeting dichotomous measures are more likely to overtreat signals that the aggressive use of medications among patients with low DBPs need to be further examined. Indeed, the measure we constructed likely underestimates the full extent of potentially hazardous, aggressive and wasteful use of medications because we only considered low DBP as evidence of overtreatment if SBP was also low (<130 mm Hg) and further if there was intensification and/or use of 3 or more BP lowering agents. The patients so identified had mean achieved BP values lower than those in the intensive therapy arm of ACCORD and are thus subject to similar adverse consequences.32 If we relax the criteria for potential overtreatment just slightly, to <135/65, the rate of overtreatment increases to nearly 10%. Although we did not examine the effect of overtreatment on adverse outcomes in this cross-sectional study, given the lack of evidence from stronger randomized trial designs that such aggressive BP lowering improves outcomes, some could view this conservative marker of overtreatment marker as just the tip of the iceberg.

We report our results in one high performing healthcare system, albeit one with nearly 1 million patients with diabetes getting regular primary care across nearly 900 sites of care. This system has a longer history with performance monitoring than many other systems. The drive to improve BP control in VA has been based primarily on motivation from the facility or regional directors to achieve nationally specified goals for meeting measures. Health systems and providers with direct financial incentives to meet measurement goals may have even more incentive to overtreat.

Despite calls by others to stamp out clinical inertia,41, 42 we find little evidence that Veterans are currently being undertreated. We note that other high performing systems, like Kaiser Permanente, have achieved similar results in BP management.43 While recognizing this impressive achievement, it appears that in VA, rates of potential overtreatment are currently approaching, and perhaps even exceeding, the rate of undertreatment and that high rates of achieving current performance measurement targets are directly associated with medication escalation that may increase risk for patients. While there is no doubt that appropriate management of hypertension among diabetic patients is of critical importance, our data suggest that VA and other high performing health systems may have reached the point when threshold measures for BP control have the potential to do more harm than good. Accordingly, VA has made the decision to implement clinical action measures for purposes of internal tracking and accountability. By motivating appropriate care and taking contraindications like low diastolic levels into account, implementing a clinical action measure for hypertension management may result, over time, in more appropriate care and more net benefit for patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge valuable input from Drs. Joseph Francis, Stephan Fihn, Rodney Hayward and Steven Bernstein.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the University of Michigan. This study was funded by VA QUERI RRP 09-111. Additional support was provided by the VA Diabetes Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (DIB 98-001) and the Measurement Core of the Michigan Diabetes Research & Training Center (NIDDK of The National Institutes of Health [P60 DK-20572]).

Footnotes

Members of the Diabetes Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Workgroup on Clinical Action Measures include: Eve Kerr, MD, MPH; Michelle Lucatorto, DNP; David Aron, MD; William Cushman, MD; John R Downs, MD; Leonard Pogach, MD, MBA; and Sandeep Vijan, MD, MS.

References

- 1.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988-2008. JAMA. 2010;303(20):2043–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engelgau MM, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, et al. The evolving diabetes burden in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(11):945–950. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preis SR, Pencina MJ, Hwang SJ, et al. Trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with and without diabetes mellitus in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;120(3):212–220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snow V, Weiss KB, Mottur-Pilson C. The Evidence Base for Tight Blood Pressure Control in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(7):587–592. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-7-200304010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(12):938–945. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerr EA, Gerzoff RB, Krein SL, et al. Diabetes care quality in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System and commercial managed care: the TRIAD study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(4):272–281. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor PJ, Bodkin NL, Fradkin J, et al. Diabetes performance measures: current status and future directions. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1651–1659. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eddy DM. Performance measurement: problems and solutions. Health Aff. 1998;17(4):7–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayward R. All-or-Nothing Treatment Targets Make Bad Performance Measures. Amer J Manag Care. 2007;13(3):126–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timbie JW, Hayward RA, Vijan S. Variation in the net benefit of aggressive cardiovascular risk factor control across the US population of patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1037–1044. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGlynn EA, Asch SM. Developing a Clinical Performance Measure. Amer J Prevent Med. 1998;14(3S):14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayward RA, Hofer TP, Vijan S. Narrative review: lack of evidence for recommended low-density lipoprotein treatment targets: a solvable problem. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):520–530. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-7-200610030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krumholz HM. Informed Consent to Promote Patient-Centered Care. JAMA. 2010;303(12):1190–1191. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turnbull F, Neal B, Algert C, et al. Effects of different blood pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events in individuals with and without diabetes mellitus: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(12):1410–1419. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vijan S, Hayward RA. Treatment of Hypertension in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Blood Pressure Goals, Choice of Agents, and Setting Priorities in Diabetes Care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(7):593–602. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-7-200304010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choe HM, Bernstein SJ, Standiford CJ, Hayward RA. New diabetes HEDIS blood pressure quality measure: potential for overtreatment. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(1):19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Messerli FH, Mancia G, Conti CR, et al. Dogma disputed: can aggressively lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease be dangerous? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(12):884–893. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Somes GW, Pahor M, Shorr RI, Cushman WC, Applegate WB. The role of diastolic blood pressure when treating isolated systolic hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(17):2004–2009. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.17.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson RJ, Bahn GD, Moritz TE, Kaufman D, Abraira C, Duckworth W. Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):34–38. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerr EA, Krein SL, Vijan S, Hofer TP, Hayward RA. Avoiding pitfalls in chronic disease quality measurement: a case for the next generation of technical quality measures. Amer J Manag Care. 2001;7(11):1033–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerr EA, Smith DM, Hogan MH, Hofer TP, Krein SL, Hayward RA. Building a better quality measure: Are some patients with poor intermediate outcomes really getting good quality care? Med Care. 2003;41(10):1173–1182. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000088453.57269.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodondi N, Peng T, Karter AJ, et al. Therapy Modifications in Response to Poorly Controlled Hypertension, Dyslipidemia, and Diabetes Mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(7):475–484. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selby JV, Uratsu CS, Fireman B, et al. Treatment intensification and risk factor control: toward more clinically relevant quality measures. Med Care. 2009;47(4):395–402. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e31818d775c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heisler M, Hogan M, Hofer T, Schmittdiel J, Pladevall M, Kerr E. When More Is Not Better: Treatment Intensification Among Hypertensive Patients with Poor Medication Adherence. Circulation. 2008;117:2884–2892. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.724104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerr EA, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Klamerus ML, Subramanian U, Hogan MM, Hofer TP. The Role of Clinical Uncertainty in Treatment Decisions for Diabetic Patients with Uncontrolled Blood Pressure. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148(10):717–727. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.AHRQ [Accessed July 27, 2011];Assessing Quality of Care for Diabetes - Conference Final Report. 2008 http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/diabetescare/

- 27.Drozda J, Jr., Messer JV, Spertus J, et al. ACCF/AHA/AMA-PCPI 2011 Performance Measures for Adults With Coronary Artery Disease and Hypertension A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the American Medical Association-Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(3):316–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper-DeHoff RM, Egelund EF, Pepine CJ. Blood pressure lowering in patients with diabetes--one level might not fit all. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(1):42–49. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. J Hypertens. 2009;27(11):2121–2158. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328333146d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The ACCORD Study Group Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. NEJM. 2010;362(17):1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper-DeHoff RM, Gong Y, Handberg EM, et al. Tight blood pressure control and cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease. JAMA. 2010;304(1):61–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2008;117(25):e510–526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farnett L, Mulrow CD, Linn WD, Lucey CR, Tuley MR. The J-curve phenomenon and the treatment of hypertension. Is there a point beyond which pressure reduction is dangerous? JAMA. 1991;265(4):489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skrondal A. Generalized Latent Variable Modeling: Multilevel, Longitudinal, and Structural Equation Models. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerr EA, Fleming B. Making performance indicators work: experiences of US Veterans Health Administration. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):971–973. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39358.498889.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powers BJ, Olsen MK, Smith VA, Woolson RF, Bosworth HB, Oddone EZ. Measuring blood pressure for decision making and quality reporting: where and how many measures? Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(12):781–788. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-12-201106210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerr EA, Smith DM, Hogan MM, et al. Comparing clinical automated, medical record, and hybrid data sources for diabetes quality measures. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28(10):555–565. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borzecki AM, Wong AT, Hickey EC, Ash AS, Berlowitz DR. Can we use automated data to assess quality of hypertension care? Amer J Manag Care. 2004;10(7 Pt 2):473–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berlowitz DR, Ash AS, Hickey EC, et al. Inadequate Management of Blood Pressure in a Hypertensive Population. NEJM. 1998;339(27):1957–1963. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812313392701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips LS, Twombly JG. It’s time to overcome clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(10):783–785. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.CCHRI Report on Quality [Accessed January 9, 2012];2010 http://tenfold.biz/report_card.php?group=HMO&report_year=2010.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.