Abstract

This paper is a review of the various surgical techniques used in repair or reconstruction of the scapholunate ligament according to the clinical stages and anatomic-pathologic findings. Arthroscopy permits a direct evaluation of the scapholunate injury and the status of the articular surfaces. Specific indications for each type of scapholunate ligament tear are proposed, from the different types of dorsal capsulodesis to bone–ligament–bone techniques and tenodesis procedures. The authors' preferred techniques and literature review of the expected outcomes are presented.

Keywords: SL ligament tear, SL ligament reconstruction, capsulodesis, wrist ligament injury

The recognition and subsequent treatment of scapholunate (SL) ligament tears is not always simple to determine, and there are divergent opinions regarding its global treatment.

In recent years, the advent of arthroscopy has permitted an increase in knowledge regarding the most appropriate form of SL ligament repair.

Clinically we can define four types of instability: (1) predynamic instability; (2) dynamic instability; (3) reducible static instability; (4) nonreducible static instability. Each one of these lesions requires a specific treatment.

Predynamic Scapholunate Dissociation

“Predynamic instability” is an older term coined by Kirk Watson to apply to instability demonstrable on physical examination but not by radiographic studies.1 This corresponds to a Geissler grade I or II instability2,3 or a European Wrist Arthroscopy Society (EWAS) grade 2, 3A, or 3B4 (Table 1). There may be attenuation or a tear of the palmar SL ligament.

Table 1. Arthroscopic classification of SL lesions according to Messina.

| STAGE | Arthroscopic findings |

|---|---|

| I | |

| II, SLIL proximal part lesion | Lesion of central/proximal part of SLIL |

| III A, SLIL partial anterior lesion | Lesion of anterior, proximal part of SLIL, lesion of SC-LRL |

| III B, SLIL partial posterior lesion | Lesion of proximal and posterior part of SLIL, lesion ofDIC |

| III C, SLIL complete lesion reducible | Complete lesion of SLIL (anterior, proximal, posterior), lesion of an extrinsic ligament (DIC or SC/LRL) |

| IV, SLIL complete lesion with gap | Complete lesion of SLIL (anterior, proximal, posterior) + extrinsic ligaments lesion (DIC, SC/LRL) |

In chronic predynamic instability, three different approaches have been proposed: (1) flexor carpi radialis muscle (FCR) proprioceptive reeducation; (2) arthroscopic debridement of the torn ligament; (3) ligament shrinkage.

It is my preference to perform a dorsal capsulodesis, which provides sagittal plane stability and restricts the abnormal scaphoid flexion.

Surgical Technique

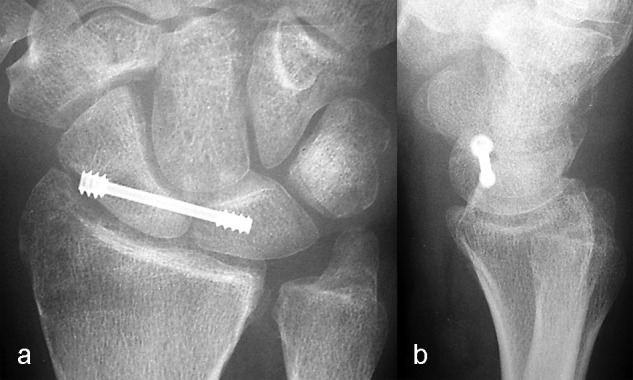

An acute partial SL ligament tear, without carpal malalignment, that can be reduced anatomically can be treated by percutaneous SL joint pinning under fluoroscopic control.5,6,7 The reduction of the carpal bones can be facilitated by placing two percutaneous Kirschner wires (K-wires) in the scaphoid and lunate and using them as “joysticks.” If there is no interposition of tissue, the SL joint can be reduced by levering the scaphoid into extension, supination, and ulnar deviation while levering the lunate into flexion and radial deviation. Two 1.2-mm K-wires are inserted through a small incision made distal to the radial styloid, taking care not to damage the radial sensory nerve branches (Fig. 1). Some authors pin the scaphocapitate (SC) articulation as well.7 The wrist is immobilized with short arm cast. The K-wires are removed at 8–10 weeks, followed by a removable splint for another 4 weeks before initiating mobilization. Rehabilitation of the hands and fingers is initiated immediately postsurgery, but grip strengthening and wrist mobilization are permitted only after 3 months, and heavy labor after 6 months.6

Fig. 1.

Technique of SL joint pinning with K-wires.

Dynamic Scapholunate Instability

A dynamic scapholunate instability is characterized by a complete SL ligament tear, but the secondary scaphoid stabilizers—the scaphotrapezial (ST), scaphocapitate (SC) and radioscaphocapitate (RSC) ligaments—are still preserved.8 The scapholunate instability or gapping can be seen radiographically only under certain loading conditions or in specific wrist positions such as such as the clenched-fist position, or loading the wrist in ulnar deviation. A direct scapholunate ligament repair is indicated when (1) the dorsal SL ligament is reparable, (2)the scapholunate joint is reducible, and (3) there is no articular cartilage damage (traumatic or degenerative).9

Surgical Technique

Various authors advise a dorsal approach to the wrist capsule between the third and fourth extensor compartment.10,11 Berger and Bishop12 have described a ligament-sparing dorsal capsulotomy. The first incision is made along the dorsal rim of the radius to the center of the lunate fossa. The second incision is made from the end of the first incision following the fibers of the dorsal radiocarpal ligament to its distal insertion onto the dorsal ridge of the triquetrum. The third incision is made from the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid (STT) joint progressing medially along the dorsal intercarpal ligament to its insertion onto the dorsum of the triquetrum. By connecting the last two incisions, a radially based capsular flap is created. This flap is carefully elevated by sectioning its connections to the dorsal edge of the three bones of the proximal row. I have recently been using a transversal cutaneous mini-access approach that permits the surgeon to reach the dorsal wrist capsule without sectioning the extensor retinaculum (Fig. 2a–e).

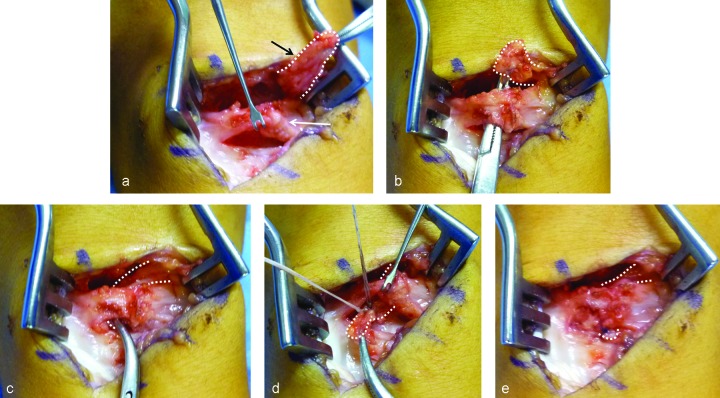

Fig. 2a–e.

Surgical technique of dorsal capsulodesis by using a short skin incision with extensor retinaculun preservation. (a) Capsule exposure with maximum preservation of the capsule itself (white arrow) using a double almost-parallel capsular incision. The proximal incision is on the dorsal radius, and the second one is on the midcarpal joint following the direction of the dorsal intercarpal ligament (DICL) fibers. After synoviectomy, a DICL flap fixed at the scaphoid is elevated (white dotted line). (c) A tunnel space is created under the capsule over the SL ligament level and a curved mosquito is passed to keep the DICL flap. (c) The DICL flap is passed under the capsule through the tunnel and (d) is fixed to the dorsal border of the lunate with a suture anchor. (e) Capsule is sutured at the end.

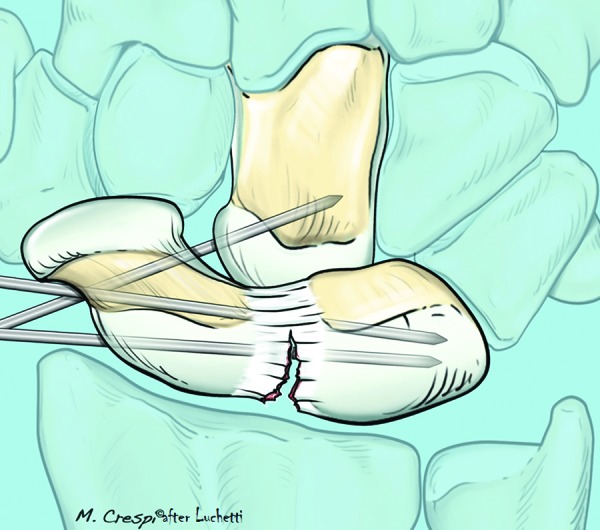

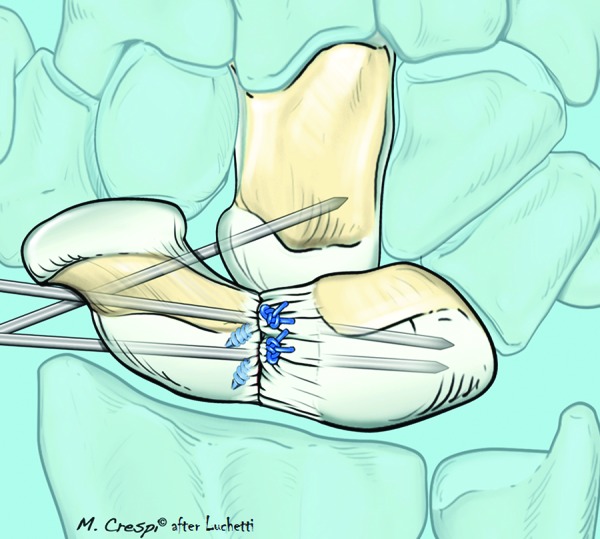

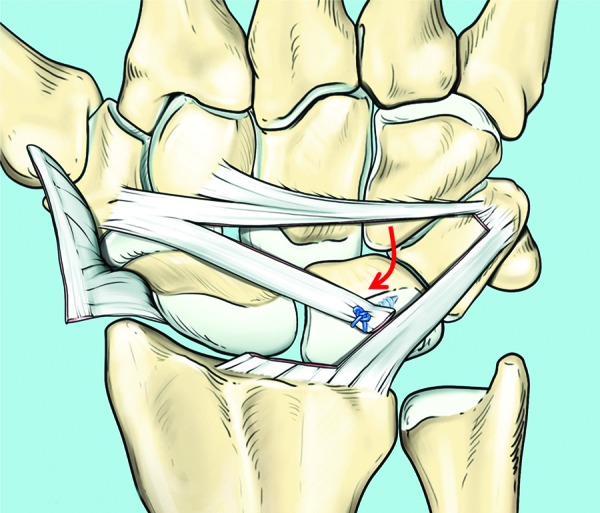

If the ligament is avulsed (often with a little osteochondral fragment), then the repair consists of reinserting the avulsed ligament into the scaphoid crest or onto the lunate with a 2.4- or 2.8-mm suture anchor (Fig. 3),9,13 combined with SL and/or SC pinning as described by Linscheid14 and Lavernia et al.15 When an osseous fragment is attached to the ligament, it can be reattached to its original position or excised if too small. In many cases this technique is augmented with a capsular or dorsal intercarpal ligament (DICL) dorsal capsulodesis.16,17,18 The K-wires are maintained in place for 6–8 weeks, followed by the application of a removable splint for another 4 weeks and protected wrist motion.

Fig. 3.

SL ligament repair with two suture anchors and pinning.

Outcomes

Pomerance reviewed 17 patients following a scapholunate interosseous ligament (SLIL) repair and dorsal capsulodesis at an average follow-up of 66 months (range, 19–120 months).19 The SL gap for a strenous job was 4 mm static and 6 mm with stress, while for a nonstrenous job the SL gap was 2 mm static and 3 mm with stress. The mean Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) score for a strenous job was 37 (range, 22–44), and for a nonstrenous job, 25 (range, 19–35). The Modified Mayo wrist score included 2 good, 10 fair, and 5 poor results. Pomerance noted that, overall, the results of repair degrade over time.

Dorsal Capsulodesis. The dorsal capsulodesis that was popularized by Blatt16,20 as an isolated procedure for scapholunate instability is no longer in vogue. A variety of techniques using all of or part of the DICL to reinforce the dorsal SL ligament have been described (Fig. 4).One of these techniques is to use a portion of the DICL, leaving its insertion into the triquetrum (Fig. 5) and rotating its radial portion to insert into the dorsoulnar corner of the scaphoid. Berger has proposed another technique21 that isolates a portion of the DICL flap at the base of the scaphoid and rotates and fixes it with suture anchors to the lunate (Fig. 6a–f).

Fig. 4.

Technique of SL dorsal capsulodesis proposed by Szabo using the entire DICL.

Fig. 5.

Technique of SL dorsal capsulodesis using part of the DICL detached from the distal scaphoid and trasferred to its proximal part across the SL ligament.

Fig. 6.

Technique of SL dorsal capsulodesis using part of the DICL detached from the triquetrum and transferred to the lunate across the SL ligament (Berger technique).

We reviewed 18 patients with chronic predynamic or dynamic scapholunate instabilitywho were treated by a dorsal intercarpal ligament capsulodesis.17 At an average follow-up of 45 months, a significant decrease in pain (P > 0.05) with improvement in grip strength (P > 0.005) was observed in all cases (Fig. 7a–f). Moran et al21 reviewed 18 with dynamic carpal instability and 13 with static carpal who underwent a dorsal capsulodesis. The average time from injury to surgery was 20 months. The follow-up period averaged 54 months (range, 24–96 months). All patients had a dorsal capsulodesis procedure using either a Blatt or a Mayo technique. There was a 20% decrease in wrist motion after capsulodesis. There was no improvement in grip strength after surgery. Most patients had improvement in pain, but only two patients were completely pain-free. Radiographically the SL gap increased over time from 2.7 mm before surgery to 3.9 mm at the final follow-up evaluation. The SL angle also increased from 56° before surgery to 62° on final follow-up evaluation. There was no statistical difference in overall wrist motion, grip strength, or wrist score between the dynamic and static groups. The time to surgery and age had no significant effect on overall outcome. Although pain was improved, it was not completely resolved in the majority of cases. From a radiographic perspective, dorsal capsulodesis did not provide maintenance of carpal alignment in cases of chronic SL dissociation.

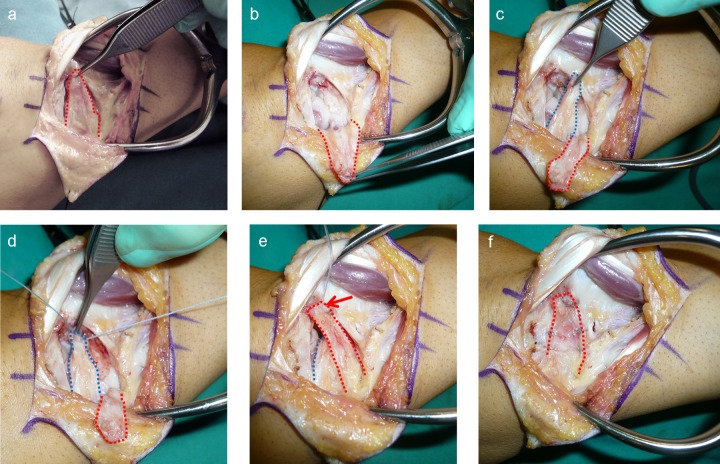

Fig. 7a–f.

Surgical demonstration of the SL dorsal capsulodesis using the Berger technique. (a) Dorsal radio-carpal capsular incision (red dotted line) according to Berger and Bishop (ligament splitting capsulotomy)12; (b) Rotation of the radiocarpal capsule flap (red dotted line), exposing the carpal bones. (c) DICL flap dissection (blue dotted line) from the radiocarpal- capsule flap (red dotted line). (d) Suture of the DICL flap (dorsal capsulodesis) to the lunate with a suture anchor. (e) Coverage of capsulodesis (blue dotted line) with the remnant radiocarpal capsule (red dotted line), in which particular attention is paid to suturing it at the ulnar border (red arrow). (f) Complete suture of the radiocarpal dorsal capsule (red dotted line).

Gajendran et al reviewed 15 patients (16 wrists) with chronic SL instability who were treated with a DICL capsulodesis.22 At an average follow-up of 86 months (range, 70–115 months) the average wrist flexion was 50° ( ± 12) and extension 55° ( ± 15). The average SL gap was 2.7 mm at 25 months and 3.5 mm at 86 months. The average DASH score was 19 (range, 0–66). A modified Mayo score included 6 excellent, 3 good, 5 fair, and 2 poor results. 8 of the 16 wrists developed osteoarthritis (OA).

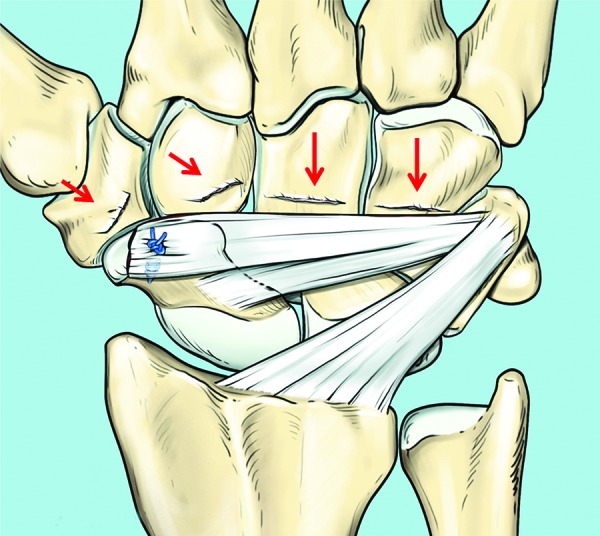

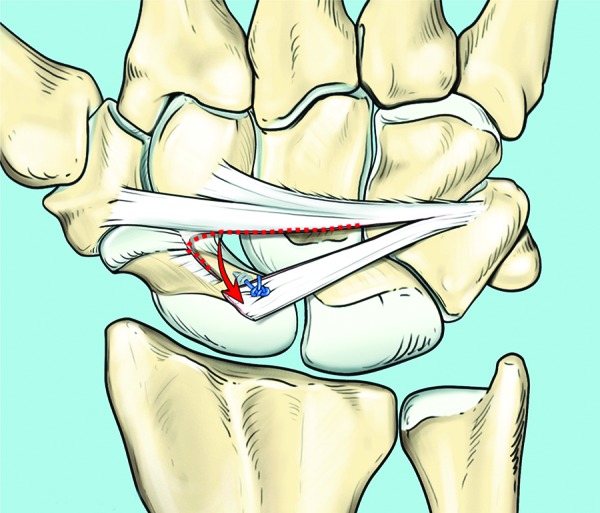

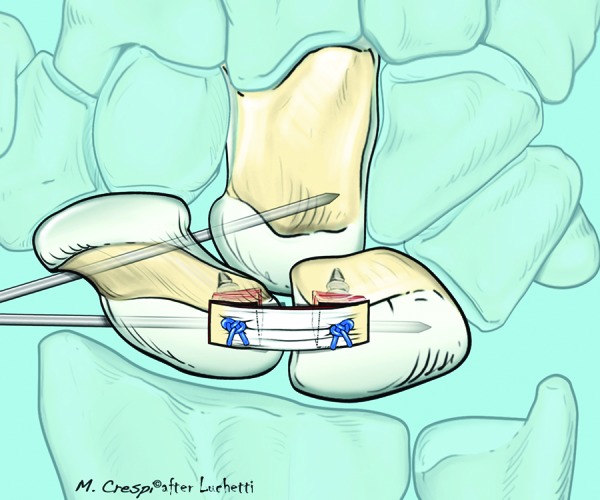

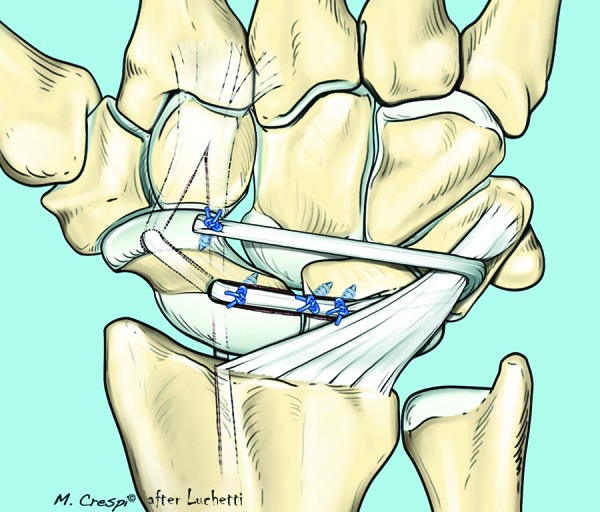

Bone–Ligament–Bone Transplant. The bone–ligament–bone (BLB) graft has been proven to be quite successful in knee ligament surgery, and various authors have studied this technique biomechanically to see whether it can be used to substitute for a nonreparable SL ligament.23,24,25,26,27,28,29 Schuind30 recommended use of a vascularized flap of the interosseous membrane. Weiss31 described the transfer of a BLB graft harvested from the Lister tubercle. This can be supplemented with a dorsal capsulodesis. Harvey and Hanel27 suggested harvesting a BLB from the third metacarpal and the capitate. The surgical approach is the same in cases of direct ligament repair. Once the carpal bones are reduced and stabilized with K-wires, a fossa is created on both bones where the bony portions of the BLB complex will be placed. These can be stabilized with mini-screws or suture anchors that have previously been inserted (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Drawing showing the bone–ligament–bone complex transferred and fixed to the lunate and the scaphoid with suture anchors in association with SL and SC pinning.

Possible potential problems include poor integration of the graft (because the proximal pole of the scaphoid has a tenuous blood supply) as well as deterioration of the mechanical properties of the graft with prolonged immobilization. The preliminary clinical results of Schuind,30 Weiss,31 Harvey,27 and Atzei25 are encouraging in cases where the secondary stabilizers are still functional (dynamic instability).

Our personal experience25 showed excellent results in six of the nine cases at a mean follow-up of 7 years with an average modified Mayo wrist score of using a BLB graft taken from the third metacarpal and the capitate. Wrist motion remained unchanged in eight patients and the pain decreased by an average of 1.7 on Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). Eight patients returned to their previous jobs and recreational activities (Fig. 9a–k). However, there was a poor correlation between the clinical and radiological results: the Glickel score averaged 10.5, and there were 5 good, 2 satisfying, and 2 poor results. Only one case failed (Table 2).

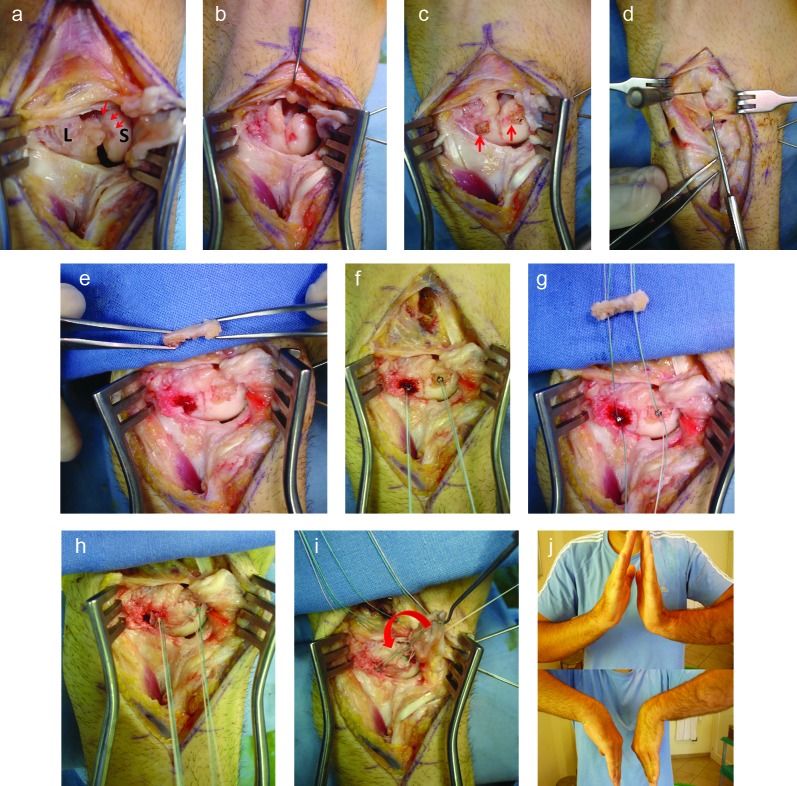

Fig. 9a–k.

Surgical procedure of SL ligament reconstruction with BLB technique. (a) Through a splitting capsulotomy the SL joint (S: scaphoid; L: lunate) is exposed and the SL ligament is completely detached from the lunate (red arrows). (b) Two K-wires are used to temporarily fix the SL and SC bones. (c) Red arrows show the two small fossae created on both scaphoid and lunate bones where the bony portions of the BLB complex will be placed. (d) Third carpometacarpal (CMC) space is localized by a needle. (e) BLB is prepared ready to be transferred to the SL bones. (f) Two suture anchors are positioned into the scaphoid and lunate fossae ready to receive the BLB. (g) Sutures are passed through bone holes previously prepared in each part of the BLB. (h) BLB sutured in situ. (i) Dorsal capsular flap is turned (red arrow) to cover the carpus and some stiches are passed through the capsule to fix it to the BLB. (k) Wrist motility at 3 months of follow-up.

Table 2. Radiologic grading system according to Glickel.

| SCAPHO-LUNATE GAP: < 2 mm (2) | DISI/VISI: absent (2) |

| > 2 mm (0) | borderline (1) |

| present (0) | |

| RING SIGN: absent (2) | |

| present (0) | OSTEOARTHRITIS: absent (3) |

| 1 + (2) | |

| SCAPHOID FLEXION: absent (2) | 2 + (1) |

| present (0) | 3 + (0) |

| C-L ANGLE: 0–10° (2) | |

| 10–20° (1) | FINAL RESULT: excellent 14–15 |

| 20° (0) | good 11–14 |

| sufficient 7–11 | |

| SCAPHO-LUNATE ANGLE: < 70° (DISI). (2) | poor 3–7 |

| 70–80° (DISI). (1) | bad 0–3 |

| >80° (DISI). (0) |

Glickel SZ, Millender LH: Ligamentous reconstruction for chronic intercarpal instability. J Hand Surg 1984, 9A, 514–527.

Static Reducible Scapholunate Dissociation

An SL dissociation is considered to be “static reducible” when (1) the ligament tear is degenerative and irreparable; (2) the secondary stabilizers (i.e., the STT and SC ligaments3,8) are insufficient, which results in a static dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) malalignment; (3) the carpal subluxation is still reducible; (4) there is no degeneration of the articular surfaces. These patients can be treated with a tendon graft reconstruction of the SL ligament3,32,33 and/or a Reduction–Association of the SL articulation (RASL) procedure..14,15,34

Tendon Reconstruction. The use of tendon grafts for reconstructing the SL ligament has evolved considerably from the time of its initial description by Dobyns et al35 in 1975. Brunelli and Brunelli described a tenodesis using a strip of the FCR tendon with encouraging results.32 Most of their patients were able to return to their prior occupations with complete remission of pain and recovery of grip strength, but with an average loss of 45° of wrist flexion in comparison to the contralateral side.36 For this reason the method was modified by Van Den Abbeele et al.37 by anchoring the graft to the lunate rather than to the distal radius (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Technique of surgical reconstruction of the SL ligament by using the FCR tendon strip according to Van Den Abbeele et al. The tendon is fixed to the lunate.

Outcomes

Moran et al examined 29 patients with isolated chronic SL instability.21 Fourteen had a dorsal capsulodesis, and 15 had undergone a modified Brunelli procedure similar to the three-ligament tenodesis described subsequently. At an average follow-up of 36 months (range, 24–84) the capsulodesis group showed an average wrist flexion of 44° (range, 10–55), average extension of 49° (range, 15–70) with an average SL gap of 4.5 mm,2,3,4,5,6 whereas the tenodesis group showed an average wrist flexion 40° (range, 10–60), and extension of 43° (range, 20–65) and an average SL gap of 4.3 mm.2,3,4,5,6,7,8 The modified Mayo wrist score for the capsulodesis group revealed one excellent, five good, six fair, and one poor result as compared with the tenodesis group, which had three excellent, three good, six fair, and three poor results. Chabas et al reviewed 19 patients with chronic SL instability were treated with a modified Brunelli tenodesis at an average follow-up of 37 months.(range, 12–60).38 Fifteen patients had no to mild pain, four had constant pain. The average wrist flexion was 41° (range, 10–60), and extension 50° (range, 20–65). The average static SL gap was 3.2 mm. The average DASH score was 30 (range, 0–91). The Wrightingon score was as follows: nine excellent, six good, three fair, and one poor result. One patient developed SLAC stage II arthritis.

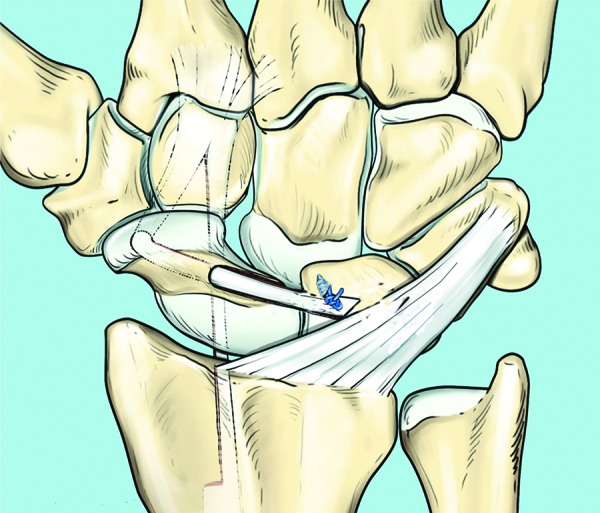

Three-Ligament Tenodesis. Garcia et al3,33 further modified the Brunelli technique and described a three-ligament tenodesis (3LT) (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Technique of surgical reconstruction of the SL ligament by using the FRC tendon strip according to Garcia-Elias.

Surgical Technique

A dorsal ligament-sparing capsulotomy is performed. An oblique tunnel along the longitudinal axis of the scaphoid is created, from dorsal to palmar, entering at the level of the original insertion site of the dorsal SL ligament, and aiming at the palmar tuberosity. A strip of the FCR tendon is then obtained. At the level of the distal pole of the scaphoid, a small, transverse palmar incision is made, and the distal part of the FCR is identified. The tendon is split. The skin is incised at the musculotendinous junction, and a radial strip of the FCR is released at the musculotendinous junction and left attached distally. The FCR tendon strip is passed through the oblique scaphoid tunnel using a wire loop or a tendon passer. A transverse trough or channel is then made over the dorsum of the lunate with a rongeur. A small anchor suture is placed into the floor of the trough. A slit is made in the distal end of the dorsal radiotriquetral (RT) ligament, and the tendon strip is passed through the slit from volar to dorsal. The ligament is used as a pulley to tension the strip. The scaphoid, lunate, and capitate are reduced and stabilized with two 1.5-mm K-wires prior to tensioning the tendon graft. One wire is placed across the SL joint and one across the scaphocapitate joint. The tendon graft is secured tightly down into the cancellous bone channel created in the lunate using the suture anchor. The end of the tendon strip is then sutured to itself and the capsule is closed.

Garcia-Elias et al reviewed 38 patients with a symptomatic SL dissociation who had undergone a 3LT procedure.33 At a mean follow-up of 46 months (range, 7–98 months), pain relief at rest was obtained in 28 patients, with 8 complaining of mild discomfort during strenuous activity and 2 having frequent pain. Twenty-nine resumed their normal occupational-vocational activities. The average ranges of motion at follow-up evaluation were 51° of flexion (74% of contralateral side), 52° of extension (77% of the contralateral side), 15° of radial inclination (78% of the contralateral side), and 28° of ulnar inclination (92% of the contralateral side). There were no signs of scaphoid necrosis. Recurrence of the carpal collapse occurred in two wrists.

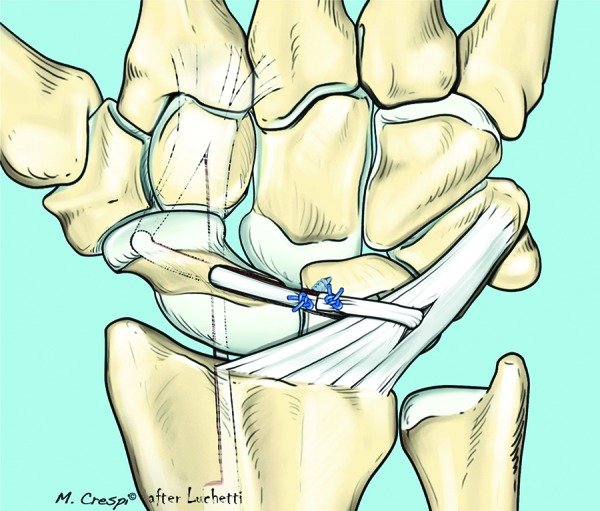

Our experience on 15 cases demonstrates a net reduction in pain under force measured on a VAS of 8 (preoperative) and 1 (postoperative), an increase in grip strength of 26 to 33 kg, and a reduction of wrist flexion and extension by ∼10%. All the patients returned to their sport and prior activities of daily living. The average DASH score was 27 (59 preoperative), and the average patient-rated wrist evaluation (PRWE) score was 18 (39 preoperative). The post-operative X-ray images always demonstrated a persistent SL gap, with an increased wound SL angle even though the Watson test was negative (Fig. 12a-g).

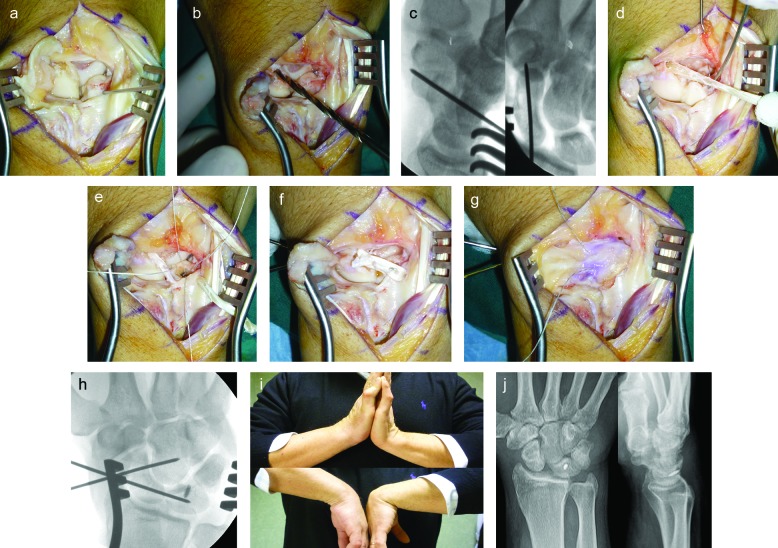

Fig. 12.

Surgical procedure of SL ligament reconstruction with FCR tendon strip according to Garcia-Elias. (a) Through a splitting capsulotomy the SL joint is exposed and the SL ligament is absent. (b) Scaphoid bone tunnel is prepared using a drill starting from the proximal dorsal side of it. (c) X-ray images show the position of the K-wires in lateral and AP views. (d) FCR tendon strip is passed through the tunnel from the palmar to the dorsal side. (e) The tendon strip is prepositioned into the RT ligament, a limited fossa is created in the position of the previously existing SL ligament to the dorsal side of the lunate, and a suture anchor is positioned. (f) The tendon strip is pulled and sutured at the lunate fossa and to itself by separated sutures. SC and SL joints are temporary fixed by two K-wires. (g) Splitting capsule is turned to cover the joint, and suture is used to fixed it to the tendon strip. (h) Intraoperative fluoroscopy showing the correct position of both the K-wires and the suture anchor with anatomical closure of the SL joint. (i) Clinical result at follow-up: good flexion-extension of the wrist. (l) X-ray images at the follow-up that show the recurrence of SL limited dissociation (completely asymptomatic).

Bain39 modified this technique to reinforce the DICL, which is a secondary wrist stabilizer, thus obtaining a quad-ligament tenodesis. The FCR tendon strip is advanced through the scaphoid and stabilizes the volar scaphotrapezial ligament, dorsal SL ligament, RT ligament, and DICL (Fig. 13). The dorsal approach is closed using an ulnar advancement V-Y capsulodesis with the dorsal capsule further reinforcing the DIC and DRC ligament.

Fig. 13.

Technique of quad tendon reconstruction of SL ligament according to Bain.

A more simple alternative to these procedures is a dorsal dynamic tenodesis using the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) as described by Brunelli40 (Fig. 14). It does not directly reconstruct the SL ligament but rather limits scaphoid flexion by attaching the ECRB tendon into the distal dorsal part of the scaphoid, similar to a Blatt capsulodesis.

Fig. 14.

Technique of dynamic tenodesis using the ECRB tendon transferred to the distal part of the scaphoid.

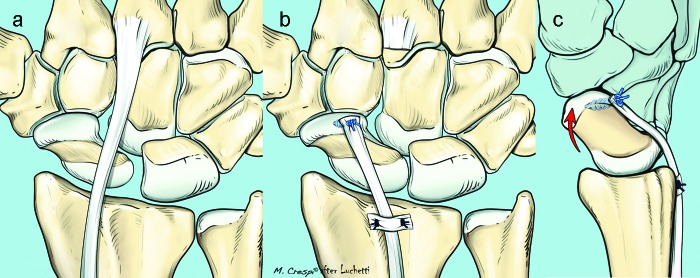

RASL technique. Herbert et al41 described a new approach based on their observation that a failed SL arthrodesis often leads to superior results than those obtained with a fusion. This innovative technique consists of an open reduction, repair of the residual ligament, and protection of the repair by blocking the SL articulation with Herbert screws for 12 months or more. The scope of this technique is to obtain an intercarpal fibrosis that is sufficient to permit full loading of these two bones while using the screw to control the scapholunate diastases (Fig. 15a,b). Rosenwasser et al popularized the reduction and association of the scaphoid and lunate (RASL) procedure using a cannulated Herbert screw.42 He recently reported excellent long-term results in 31 patients with a chronic static SL instability at an average follow-up of 6.4 years (range: 16 months–18.0 years).43 The mean DASH score was 17.0 (range: 0 to 50.8), and the mean VAS was 1.65 (range 0–7.3) with moderate activity.

Fig. 15a,b.

X-ray images of RASL technique (a and b).

Using a screw to stabilize the scapholunate interval, however, is not as successful. Filan and Herbert44 wound and Fernandez45 recommend removing the screws after a few months on account of the technical difficulty and long-term disastrous effects of leaving the screw in place. Cognet et al46 published poor results and focused their attention on the disastrous consequences due to the retained a the screws: in all their cases, the lunate and proximal part of the scaphoid were destroyed with severe secondary degenertion of the radio-carpal articulation. They concluded that this technique should never be used.

Garcia-Elias3 has proposed a treatment algorithm that can be referred to each time we are faced with treating a patient affected by an SL ligament lesion (Table 2).

Conflict of interest None

Note

Work was done at the Rimini Hand Surgery and Rehabilitation Center.

References

- 1.Watson H, Ottoni L, Pitts E C, Handal A G. Rotary subluxation of the scaphoid: a spectrum of instability. J Hand Surg [Br] 1993;18(1):62–64. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(93)90199-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geissler W B, Haley T H. Arthroscopy management of scapholunate instability. Atlas Hand Clin. 2001;6:253–274. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Elias M. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 2011. Carpal instability dissociative. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messina J, Dreant N, Van Overstraeten L, Luchetti R, Mathoulin C. Evolution of arthroscopic classification in scapholunate complex lesions. J Hand Surg [Br] 2012;37:S85–S86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taleisnik J. St Louis: Mosby; 1982. Scapholunate dissociation; pp. 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linscheid R L. Scapholunate ligamentous instabilities (dissociations, subdislocations, dislocations) Ann Chir Main. 1984;3(4):323–330. doi: 10.1016/s0753-9053(84)80008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Brien E T. Acute fractures and dislocations of the carpus. Orthop Clin North Am. 1984;15(2):237–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Short W H, Werner F W, Green J K, Masaoka S. Biomechanical evaluation of ligamentous stabilizers of the scaphoid and lunate. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27(6):991–1002. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.35878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bickert B, Sauerbier M, Germann G. Scapholunate ligament repair using the Mitek bone anchor. J Hand Surg [Br] 2000;25(2):188–192. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1999.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weil C, Ruby L K. The dorsal approach to the wrist revisited. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11(6):911–912. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(86)80251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potts H, Noble J. Surgical approaches to the dorsum of the wrist: brief report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70(2):328–329. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B2.3346318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger R A, Bishop A T, Bettinger P C. New dorsal capsulotomy for the surgical exposure of the wrist. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35(1):54–59. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199507000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wyrick J D, Youse B D, Kiefhaber T R. Scapholunate ligament repair and capsulodesis for the treatment of static scapholunate dissociation. J Hand Surg [Br] 1998;23(6):776–780. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(98)80095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linscheid R L, Dobyns J H. Treatment of scapholunate dissociation. Rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid. Hand Clin. 1992;8(4):645–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavernia C J, Cohen M S, Taleisnik J. Treatment of scapholunate dissociation by ligamentous repair and capsulodesis. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(2):354–359. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(92)90419-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blatt G. Capsulodesis in reconstructive hand surgery. Dorsal capsulodesis for the unstable scaphoid and volar capsulodesis following excision of the distal ulna. Hand Clin. 1987;3(1):81–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luchetti R, Zorli I P, Atzei A, Fairplay T. Dorsal intercarpal ligament capsulodesis for predynamic and dynamic scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2010;35(1):32–37. doi: 10.1177/1753193409347686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slater R R Jr, Szabo R M, Bay B K, Laubach J. Dorsal intercarpal ligament capsulodesis for scapholunate dissociation: biomechanical analysis in a cadaver model. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(2):232–239. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.1999.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pomerance J. Outcome after repair of the scapholunate interosseous ligament and dorsal capsulodesis for dynamic scapholunate instability due to trauma. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(8):1380–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deshmukh S C, Givissis P, Belloso D, Stanley J K, Trail I A. Blatt's capsulodesis for chronic scapholunate dissociation. J Hand Surg [Br] 1999;24(2):215–220. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1998.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran S L, Ford K S, Wulf C A, Cooney W P. Outcomes of dorsal capsulodesis and tenodesis for treatment of scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(9):1438–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gajendran V K, Peterson B, Slater R R Jr, Szabo R M. Long-term outcomes of dorsal intercarpal ligament capsulodesis for chronic scapholunate dissociation. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(9):1323–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuénod P. Osteoligamentoplasty and limited dorsal capsulodesis for chronic scapholunate dissociation. Ann Chir Main Memb Super. 1999;18(1):38–53. doi: 10.1016/s0753-9053(99)80055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuénod P, Charrière E, Papaloïzos M Y. A mechanical comparison of bone-ligament-bone autografts from the wrist for replacement of the scapholunate ligament. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27(6):985–990. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.36514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atzei A Calderara D Pangallo L et al. Long term results of bone-ligament-bone reconstruction of dynamic scapholunate instability J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2010; 35E Supplement 1 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coe M, Spitellie P, Trumble T E, Tencer A F, Kiser P. The scapholunate allograft: a biomechanical feasibility study. J Hand Surg Am. 1995;20(4):590–596. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey E J, Hanel D, Knight J B, Tencer A F. Autograft replacements for the scapholunate ligament: a biomechanical comparison of hand-based autografts. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(5):963–967. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.1999.0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofstede D J, Ritt M J, Bos K E. Tarsal autografts for reconstruction of the scapholunate interosseous ligament: a biomechanical study. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(5):968–976. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.1999.0968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin S S, Moore D C, McGovern R D, Weiss A PC. Scapholunate ligament reconstruction using a bone-retinaculum-bone autograft: a biomechanic and histologic study. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(2):216–221. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuind F A. Scapholunate reconstruction using a vascularized flap of the interosseous membrane. Orthop Surg Tech. 1995;9:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss A PC. Scapholunate ligament reconstruction using a bone-retinaculum-bone autograft. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(2):205–215. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunelli G A, Brunelli G R. Une nouvelle intervention pour la dissociation scapholunaire. Proposition d'une nouvelle technique chirurgicale pour l'instabilité carpienne avec dissociation scapholunaire (11 cas). [in French] Ann Chir Main Memb Super. 1995;14(4-5):207–213. doi: 10.1016/s0753-9053(05)80415-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Elias M, Lluch A L, Stanley J K. Three-ligament tenodesis for the treatment of scapholunate dissociation: indications and surgical technique. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(1):125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldner J L. Treatment of carpal instability without joint fusion—current assessment. J Hand Surg Am. 1982;7(4):325–326. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(82)80138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobyns J H, Linscheid R L, Chao E YS, Weber E R, Swanson G E. Traumatic instability of the wrist. Instr Course Lect. 1975;24:189–199. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunelli G A, Brunelli G R. A new technique to correct carpal instability with scaphoid rotary subluxation: a preliminary report. J Hand Surg Am. 1995;20(3 Pt 2):S82–S85. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(95)80175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Den Abbeele K LS, Loh Y C, Stanley J K, Trail I A. Early results of a modified Brunelli procedure for scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg [Br] 1998;23(2):258–261. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(98)80191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chabas J F, Gay A, Valenti D, Guinard D, Legre R. Results of the modified Brunelli tenodesis for treatment of scapholunate instability: a retrospective study of 19 patients. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33(9):1469–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bain G I, Watts A C, McLean J, Lee Y C, Eng K. Cable-augmented, quad ligament tenodesis scapholunate reconstruction: rationale, surgical technique, and preliminary results. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2013;17(1):13–19. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0b013e31827204ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brunelli F, Spalvieri C, Bremner-Smith A, Papalia I, Pivato G. Dynamique d'une instabilité statique scapholunaire par transfert tendineux actif du muscle court extenseur du carpe: rapport préliminaire [in French] Chir Main. 2004;23(5):249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herbert T J, Hargreaves I C, Clarke A M. A new surgical technique for treating rotatory instability of the scaphoid. Hand Surg. 1996;1:75–77. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenwasser M P, Miyasajsa K C, Strauch R J. The RASL procedure: reduction and association of the scaphoid and lunate using the Herbert screw. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 1997;1(4):263–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White N JRD, Crow S A, Swart E, Rosenwasser M P. Reduction and association of the scaphoid and lunate (RASL): long-term follow-up of a reconstruction technique for chronic scapholunate dissociation. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Filan S L, Herbert T J. Herbert screw fixation for the treatment of scapholunate ligament rupture. Hand Surg. 1998;3:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez D L Scapholunate ligament reconstruction and temporary screw fixation for scapholunate instability. Paper presented at: Eurohand 2008, Federation of European Societies for Surgery of the Hand 13th Congress and European Federation of Societies for Hand Therapy 9th Congress, June 19–24, 2008, Lausanne, Switzerland. [Abstract] http://www.congress-info.ch/eurohand2008/sc_prgr_fessh.php?id=707. Accessed March 17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cognet J M, Levadoux M, Martinache X. The use of screws in the treatment of scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2011;36(8):690–693. doi: 10.1177/1753193411410154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]