Abstract

Phage viruses that infect prokaryotes integrate their genome into the host chromosome; thus, microbial genomes typically contain genetic remnants of both recent and ancient phage infections. Often phage genes occur in clusters of atypical G+C content that reflect integration of the foreign DNA. However, some phage genes occur in isolation without other phage gene neighbors, probably resulting from horizontal gene transfer. In these cases, the phage gene product is unlikely to function as a component of a mature phage particle, and instead may have been co-opted by the host for its own benefit. The product of one such gene from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, STM3605, encodes a protein with modest sequence similarity to phage-like lysozyme (N-acetylmuramidase) but appears to lack essential catalytic residues that are strictly conserved in all lysozymes. Close homologs in other bacteria share this characteristic. The structure of the STM3605 protein was characterized by X-ray crystallography, and functional assays showed that it is a stable, folded protein whose structure closely resembles lysozyme. However, this protein is unlikely to hydrolyze peptidoglycan. Instead, STM3605 is presumed to have evolved an alternative function because it shows some lytic activity and partitions to micelles.

Keywords: Crystal structure, mutagenesis, oligomeric state, phage-like lysozyme, Salmonella

INTRODUCTION

Bacteriophage containing large double-stranded DNA genomes induce lysis of susceptible host cells for the release of progeny virions using endolysins that degrade the bacterial cell wall (reviewed in [1]). Jacob and Fuerst [2] demonstrated as early as 1958 that a phage enzyme(s) induced lysis of Escherichia coli K-12 and coined the term “endolysin.” Endolysins form a group of proteins that is distinct from other lytic enzymes that disrupt bacterial cell from the outside during phage infection. The latter subset is represented for example by T4 lysozyme [3]. Endolysins can be divided into five main classes based on enzymatic specificity: the first three, N-acetylmuramidases (lysozymes), endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidases, and lytic transglycosylases cleave the sugar moiety of peptidoglycan; endopeptidases cleave the peptide moiety; and N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidases cleave the amide bond between the sugar and peptide moieties [1, 4]. The unique ability of endolysins to rapidly degrade bacterial cell walls in a generally species-specific manner makes them attractive antibacterial agents [4, 5].

The phage-like lysozyme encoded by STM3605 of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is highly conserved in Salmonella and has homologs of approximately 60% sequence identity in other enterobacteria. While the exact origin of this gene is unknown, it is likely derived from horizontal transfer following an ancestral phage infection. Indeed, sequencing projects have revealed several bacteriophages in Salmonella [6]. Supporting the possibility of horizontal transfer, the GC content of STM3605 (48.9%) is lower than the genomic average of 52.2%, whereas the average for the 20 genes surrounding STM3605 on the chromosome is 53.3%, closer to the genomic average. This suggests that STM3605 had a different origin than its genomic neighbors.

STM3605 encodes a small (13.5 kDa) protein with no predicted sec-dependent secretion signal or transmembrane helices [7, 8] indicating that it is likely a cytoplasmic protein. Interestingly, this protein has been predicted to be secreted via the type 3 secretion system (T3SS), a needle-like nanomachine that injects proteins from Salmonella directly into the cytoplasm of infected host cells [9]. Using the SVM-based Identification and Evaluation of Virulence Effectors (SIEVE) method [10][11](http://www.sysbep.org/sieve/), STM3605 has the 11th highest probability among all Salmonella proteins of being secreted via T3SS, excluding known secreted effectors. Similarly, using the T3SS prediction method “Effective” [12], STM3605 scores higher than several known T3SS effectors: 0.99959 vs. 0.38541 for SrfH, 0.99097 for SseL, and 0.07148 for SptP (http://effectors.org/index.jsp). Secretion via the T3SS has been tested in RAW 264.7 cells, but no secretion was observed (Niemann and Heffron unpublished result). However, secretion may still occur under conditions specific for STM3605 that were not tested, or by a mechanism distinct from T3SS, such as outer membrane vesicles. While the function(s) of the Salmonella phage-like lysozyme during growth or host infection remain unknown, it is important to keep in mind that other multi-functional endolysins have been identified, including T7 lysozyme that binds RNA polymerase and inhibits T7 transcription during infection of the bacterial host cell [13]. Thus, further characterization of this Salmonella protein may reveal new roles. We have cloned, purified, crystallized, determined its structure and tested the enzymatic activity of the STM3605 protein from S. Typhimurium LT2 in order to facilitate a functional and structural investigation of the protein. Here we report the X-ray structure of STM3605 and its functional analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, analysis of expression and solubility

The gene cloning was performed according to Kim et al. [14]. Briefly, the STM3605 gene fragment coding for residues 5-107 (STM3605t) was PCR-amplified using the following set of primers: 5’-TACTTCCAATCCAATGCCTCATCTCGCTTTAGCTCCGCCT and 5’-TTATCCACTTCCAATGTTAATCACCCGTATTGATTAATGATAAAAAACGCTGA. The purified PCR product was treated with T4 polymerase in the presence of dCTP according to vendor specification (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA). The protruded DNA fragment was mixed with the Ligation-Independent Cloning (LIC)-ready vector pMCSG7 and transformed to the E. coli BL21(DE3) Magic strain. A single colony was picked, grown and induced with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG). The cell lysate was analyzed for presence of the protein with the right molecular weight. The solubility was analyzed via small scale Ni2+ affinity purification and overnight TEV protease cleavage followed by 0.22 μm filtration of digested sample. The cloning of the full length STM3605 (STM3605f) was performed identically to the above with the following primers used: 5’-TACTTCCAATCCAATGCCATGCCGCACATTTCATCTCGCTTTAG and 5’ TTATCCACTTCCAATGTTAAATTCGCAGTCCGCTTATTTCTGGCT.

Point mutations were introduced at positions Q20E and V35T using a procedure based on the Polymerase Incomplete Primer Extension (PIPE) cloning [15] to generate Q20E_STM3605f and Q20E/V35T_STM3605f protein variants. The efficiency of cohesive ends creation was enhanced by T4 polymerase treatment of the amplified plasmid. Briefly, a plasmid carrying the STM3605 coding sequence was PCR-amplified by KOD Hot Start polymerase in presence of 1 M betaine and the following primers; 5’-AAACAGTGGGAGGGTCTGTCGCTGGAAAAGTATCG and 5’-GACAGACCCTCCCACTGTTTAATAAACGCGATGCAGG for Q20E, 5’-GGTAACTGGACGATTGGTTACGGGCATATGTTGACG and 5’-GTAACCAATCGTCCAGTTACCCTGCCGATCGC for V35T. The unpurified PCR product was digested with T4 polymerase without any dNTPs according to Dieckman et al. [16]. The T4 polymerase-treated mixture was transformed to the E. coli BL21(DE3) Magic strain. Plasmids purified from single colonies were sequenced at University of Chicago Cancer Research DNA Sequencing Facility.

Protein expression and purification

The starter cultures were grown at 37° C overnight in 500 mL polyethylene terephthalate beverage bottles containing 25 mL of non-sterile modified M9 salts “pink” medium [17]. It was then transferred to a 2 L polyethylene terephthalate beverage bottle containing 1L of M9 “pink” media. Cells were allowed to grow until OD600 reached 1.4. They were cooled down to 18° C before inhibitory amino acids (25 mg each of L-valine, L-isoleucine, L-leucine, L-lysine, L-threonine, L-phenylalanine), 15 mg selenomethionine (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, catalog number MD045004D), and IPTG to final concentration 1 mM were added to the culture. Cells were then grown overnight at 18° C and harvested the next morning. 15 g of cells were harvested from 2 L of culture. The cells were re-suspended in 60 ml of lysis buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, plus two protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (cOmplete ULTRA, Roche, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA). Re-suspended cells were stored at -80° C before processing. Frozen cells were thawed and lysed on ice. Lysates were sonicated for 5 min and centrifuged at 30,000 g for 60 min followed by filtration through 0.45 μm syringe filters. Clarified lysates were loaded on an ÄKTAxpress (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA) for automated purification using affinity chromatography (IMAC) followed by size exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad 26/60, Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). A single peak containing 30 mg purified protein was collected from the size exclusion chromatography column. Purified protein was digested with 0.3 mg of recombinant His-tagged TEV protease for 48 h to remove the His-tag from the protein. The digestion was verified by SDS-PAGE and showed complete removal of the His-tag. A second IMAC was performed on the ÄKTAxpress to remove the free His-tag and TEV protease. The protein was then concentrated to 17 mg/ml in crystallization buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT.

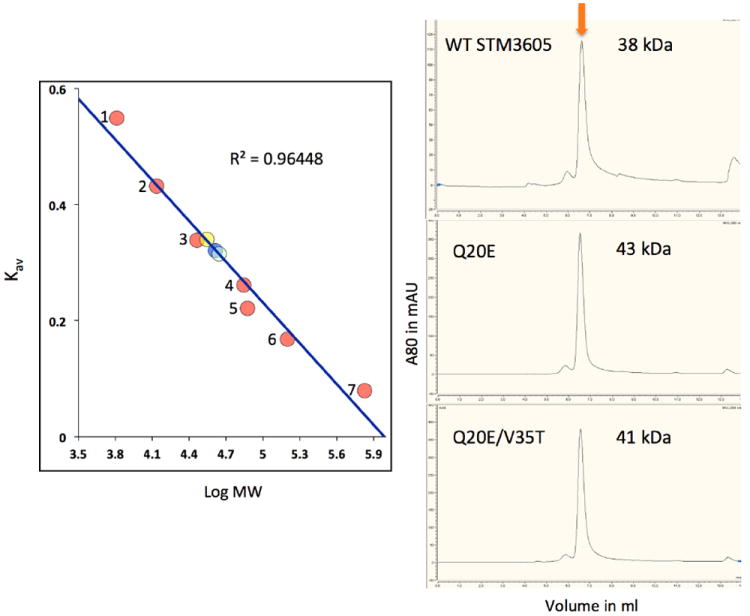

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC)

The molecular weight of wild type (wt) and mutated STM3605f protein in solution was analyzed by HPLC SEC using a SRT SEC-150 (7.8 × 250 mm) column (Sepax Tech. Inc, Delaware, Newark, USA) in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES/NaOH pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl and 2 mM DTT according to the method described previously. The column was equilibrated and calibrated using standard proteins from the HMW Gel Filtration Calibration Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The chromatography was carried out at 22° C at a flow rate of 1.2 ml/min The following proteins were prepared in running buffer at a concentration of 5 mg/ml: aprotinin (6.5 kDa), ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), conalbumin (75 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa) and thyroglobulin (669 kDa) to determine a calibration profile. The calibration curve of Kav versus log molecular weight was prepared using the equation Kav = Ve−Vo/Vt−Vo, where Ve = elution volume for the protein, Vo = column void volume, and Vt = total bed volume. Elution volumes were noted and a linear regression analysis was applied to the standards. The STM3605f protein (~5 mg/ml) was re-suspended in the running buffer and analyzed under the same conditions as the standards.

Protein reductive methylation

To produce crystals suitable for diffraction, the concentrated protein was subjected to reductive methylation of lysine residues [18]. After reductive methylation, the protein was exchanged with crystallization buffer. Protein was concentrated to 37 mg/ml.

Cell lysis assay

The bacterial strains Micrococcus luteus ATCC No. 4698 and Bacillus pumilus ATCC 27142 were grown in aerobic cultures in BHI media containing agar, at 28° C overnight. The E. coli K12 strain was grown in Luria-Bertani medium. A small amount of the culture was then allowed to grow in liquid BHI media overnight. 100 μl of the cells were then transferred to each well of a 96-well plate. Final concentration of STM3605 wt or mutant proteins were added to each well. The change in OD at 600 nm (OD600) was recorded using the plate reader every minute for 1 hour. All assays were done in triplicates.

Micelles assay

50 μl samples of each protein (80 mg/ml) were mixed well with ice-cold 100 μl of 10% (v/v) Triton X-114 and 350 μl of a buffer MA containing 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, and 2 mM DTT. Samples were first incubated on ice for 10 min and then 10 min at 30° C. They were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 30° C. The detergent phase was washed with 400 μl of a buffer MA at 30° C; the buffer phase was washed with 100 μl of 10% Triton X-114 at 30° C. They were centrifuged again at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 30° C. They were washed twice to ensure clear separation of the two phases. The detergent phase was washed with 15 ml of the buffer to remove extra detergent and concentrated down to 100 μl. 10 μl of each of the samples were loaded on SDS-PAGE.

Crystallization

STM3605t SeMet-labeled and methylated protein at 37 mg/ml was used to set up crystallization screen using Mosquito liquid dispenser (TTP LabTech, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). MCSG1, MCSG2, MCSG3, and MCSG4 screens (Microlytic Inc, Woburn, Massachusetts, USA) were used for the screening in 96-well CrystalQuick plates (Greiner Bio-one, Monroe, North Carolina, USA). 500 nl of protein were mixed with 500 nl of each crystallization reagent and the plates were allowed to equilibrate at 16° C. X-ray quality crystals appeared in the MCSG D3 conditions, containing 0.14 M CaCl2, 0.07 Na acetate/HCl pH 4.6, 14% (v/v) 2-propanol.

Data collection and structure solution

Prior to data collection, the crystals were soaked in mother liquor supplemented with 30% (v/v) glycerol and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. The X-ray diffraction dataset extending to 1.7 Å was collected at the Structural Biology Center beamline ID-19 at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. The single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) dataset was collected at 100K near the selenium K-absorption edge. The diffraction images were processed with the HKL3000 suite [19]. Intensities were converted to structure factor amplitudes in the Truncate program [20] from the CCP4 package [21]. The structure was solved by SAD method using selenium peak data and the HKL3000 software pipeline. The initial protein models were built in ARP/wARP [22]. Manual model rebuilding was carried in COOT [23] and crystallographic refinement was performed in Buster [24]. The processing and refinement statistics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of crystallographic data.

| Data collection statistics | |

|---|---|

| Radiation source | APS, ID-19 |

| Space group | P6122 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a=54.4 c= 260.7 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9793 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 35.00-1.70 (1.73 – 1.70) |

| Unique reflections | 26,172 (1263) |

| Rmerge (%)b | 0.074 (0.667) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.7 (100) |

| Redundancy | 6.6 (6.1) |

| <I>/<σI> | 23.2 (2.43) |

|

| |

|

Refinement

| |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20.07 – 1.70 |

| Number of reflections work/test set | 24,767/1,314 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.7 |

| Rcryst/Rfreec | 0.195/0.215 |

| Number of atoms | |

| Protein/water | 3046/96 |

| RMSD bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 |

| RMSD bond angles (deg) | 1.20 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein/water | 39.9/44.5 |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 31.66 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Outliers | 0 |

| Favored | 99.45 |

| PDB ID | 4EVX |

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell.

Rmerge = ΣhΣj|Ihj–<Ih>|/ΣhΣjIhj, where Ihj is the intensity of observation j of reflection h.

R = Σh|Fo|–|Fc|/Σh|Fo| for all reflections, where Fo and Fc are observed and calculated structure factors, respectively. Rfree is calculated analogously for the test reflections, randomly selected and excluded from the refinement.

RESULTS

Protein constructs

The wild type STM3605f protein consists of 118 residues. For crystallographic and functional assays we have expressed and purified four protein variants. STM3605t construct consists of residues 5-107 and includes two methionine residues. This protein has been expressed in the presence of SeMet to enable SAD-based crystal structure solution. In addition, STM3605t has been subjected to reductive methylation to facilitate the crystallization process. Simultaneously we also expressed and attempted to crystallize a full-length Se-labeled non-methylated variant (STM3605f), but those efforts were only partially successful. Namely, the obtained crystals allowed us to solve the structure (~2.4 Å resolution) but we could not complete satisfactory refinement due to high anisotropy. Therefore, we will base our structure description and comparisons on the truncated STM3605t protein refined to 1.7 Å resolution.

For functional analysis we have used the native full-length STM3605f and designed, based on structural comparisons of the active sites, two full-length mutants, Q20E_STM3605f and Q20E/V35T_STM3605f, which were also produced as native proteins (i.e. no Se-Met).

Sequence and structure analysis

STM3605t crystallizes in the hexagonal space group, P6122, with two protein chains in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 1) and 96 water molecules. Neither of the two independent polypeptides is fully visible in the electron density map. The longer one has been modeled from Arg7 up to Ile103. The experimental data confirm successful protein methylation as the methyl groups are clearly visible in the electron density maps at Lys17 and Lys26 in both protein molecules (Fig. 1). In addition, there is evidence that the protein suffered from oxidation manifesting in Cys12 modification into hydroxycysteine (not shown). Moreover, the two molecules are covalently linked via two disulfide bonds involving Cys74A-Cys67B and vice versa (Fig. 1), possibly also as a result of oxidative process.

Fig. 1. Structure of STM3605.

(a). Superposition of molecule A (purple) and B (pink). (b). Covalent dimer created through two disulfide bonds shown in 2mFo-DFc electron density map contoured at 1σ level. (c). Dimethylated lysine residue (Lys26) shown in 2mFo-DFc electron density map contoured at 1σ level.

STM3605 is a single-domain protein with the following topology: α1β1β2α2α3. Analysis of the protein sequence and structure reveals similarity to numerous phage and bacterial phage-like lysozyme (N-acetylmuramidase) proteins. The results from InterProScan [25] suggest that STM3605 belongs to the lysozyme-like superfamily (SSF53955), while CATH3d [26] recognizes a lysozyme domain belonging to the CATH family 1.10.530.40. A structure similarity search using Dali [27] identifies several lysozyme structures. The closest match is p22 lysozyme (PDB entry 2ANV, Z-score 8.5, rmsd 2.7 Å over 88 residues, sequence identity 25%), while the next hit corresponds to T4 lysozyme (PDB entry 151L, Z-score 7.9, rmsd 2.1 Å over 86 residues, sequence identity 28%). Profunc analysis [28] also indicates sequence similarity to lysozymes, but the program did not find similarity to any enzyme active site template or ligand-binding site template.

T4 lysozyme is longer than STM3605 and contains 164 residues folded into N- and C-terminal domains. Superposition of STM3605 and T4 lysozyme shows good agreement within the N-terminal portion (Fig. 2), but from the C-terminal domain only the equivalent of helix H5 is present in STM3605t (α3). The wild type protein is long enough to also create helix H6, but in the STM3605f variant we do not see such an element. Theoretically, our truncated variant could also form part of the H6 helix, but instead, we observe C-termini of both molecules oriented towards the putative active site. We do not know if the observed conformation of the C-terminus represents a native state of the protein, especially because in the STM3605f crystal the tail too enters the “active site” but it is oriented in the opposite direction compared to the STM3605t variant. It is notable, however, that the T4 lysozyme fold is to some extent reconstructed within the STM3605t dimer created by molecule A and a symmetry related molecule B’ occupying position x, x-y, -z+1/6 (Fig. 2B). Specifically, helix α3 from B’ overlaps with the H10 helix from T4 lysozyme within the dimeric assembly.

Fig. 2. Comparison between STM3605t and T4 lysozyme.

(a). Superposition of STM3605t (molecule A, purple) with T4 lysozyme (grey, PDB code 151L). H and S labels refer to T4 lysozyme, while α and β correspond to STM3605t. (b). Superposition of the STM3605t noncovalent dimer (molecule A – purple, molecule B’ – pink) with T4 lysozyme. (c). Superposition of T4 lysozyme (grey surface) with STM3605t (purple) showing the C-terminal tail (in 2mFo-DFc electron density map contoured at 1σ level) of STM3605 going through the enzyme active site.

According to the PISA prediction [29], the protein can form two types of tetramers (not shown), each a dimer of dimers. These tetramers are created by two different sets of identical dimers. Within one of these dimers, the molecules are cross-linked by two disulfide bonds (see above, Fig. 1). It has to be noted though, that in STM3605f we do not observe a tetrameric assembly structure or a covalently-bound dimer. We do notice, however, a dimer analogous to the one created through symmetry operation between STM3605t molecule A and B’ (x, x-y, -z+1/6; Fig. 2). Therefore, it seems that a tetramer is a crystallographic artifact caused by formation of disulfide bonds. Most likely, the biologically relevant oligomer is the aforementioned noncovalent dimer, although results from SEC indicate species with molecular weight corresponding to a trimer (~40 kDa) for the wt protein and active site mutants (Fig. 3). It is also possible that the dimer migrates anomalously on the SEC column.

Fig. 3. HPLC size exclusion chromatography of native STM3605 protein and its mutants.

WT SMT3605f is shown as yellow circle, double mutant Q20E/V35T is blue and single mutant Q20E is light blue, standards (pink circles) are 1. aprotinin (6.5 kDa), 2. ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), 3. carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), 4. ovalbumin (43 kDa), 5. conalbumin (75 kDa), 6. aldolase (158 kDa) and 7. thyroglobulin (669 kDa).

Potential active site and lytic activity

In lysozymes, the residues involved in catalysis are Glu (acid catalyst) and Asp (general base) [30, 31]. The latter residue is not essential, for example goose lysozyme does not have it [32]. On the other hand, Glu has been shown to be indispensable [33]. STM3605 contains Gln20 and Asp29 in equivalent positions (Fig. 4), therefore it appears to be missing the key catalytic residue that protonates the scissile glycosidic bond. Also in T4 lysozyme Thr26 involved in positioning of the key catalytic water molecule [34] is replaced by Val35 in STM3605. In addition, the C-terminus of the molecule is oriented toward the putative active site leaving no space for a ligand to bind. As mentioned earlier, we do not know if this conformation is biologically relevant. Based on structural alignment with other functionally active lysozymes, we designed two active site mutations Q20E (introducing acid catalyst) and a double mutant Q20E/V35T (introducing acid catalyst and Thr involved in orienting the catalytic water molecule) in order to restore enzymatic function. We generated both mutants and confirmed their gene DNA sequences and both proteins were purified.

Fig. 4. Comparison of the putative “active site” of STM3605 with T4 lysozyme.

(a). Superposition of the STM3605t (purple and pink) with T4 lysozyme (grey, PDB code 151L) with residues important for catalysis in T4 lysozyme and their STM3605 counterparts (labeled) shown in a stick representation. (b). The same as in A with active site cavities calculated in SURFNET [43] shown as purple surface (STM3605, calculated for a protein with residues Gly95 – Ile103 excluded) and grey mesh (T4 lysozyme).

We have tested wt STM3605f and mutated proteins for cell lysis activity using Gram-positive M. luteus cultures, a standard strain used for testing lysozyme activity. We have shown that the wt protein appears to have cell lysing function and inhibits M. luteus growth (Fig. 5). Both active site mutants seem to be less effective than wt protein with double mutant Q20E/V35T being worse than Q20E. However, similar assay performed with B. pumilus (Gram-positive) and E. coli (Gram-negative) cultures show no cell lysis inhibitory effect (data not shown) even at high protein concentration. These results suggest that the cell disrupting function of STM3605 appears not to be directly linked to its hydrolytic activity. It has been reported previously that lysozymes can damage bacterial cells by inserting into cell membrane [35, 36]. To test this hypothesis we evaluated whether SMT3605 can partition into micelles formed by detergent Triton X-114 [37]. Fig. 6 indeed shows that wt STM3605 and its mutants can partly be inserted into the micelles (lines 8, 11 and 14). This process is much less efficient compared to a true transmembrane protein (photoreaction center in line 2) but is significantly better than the hen egg-white lysozyme.

Fig. 5. Cell lysis assay with M. luteus ATCC No. 4698 strain of native STM3605 protein and its mutants.

WT SMT3605f is shown as red circles, single mutant Q20E is green, and double mutant Q20E/V35T is blue. Yellow circles correspond to the control with no protein added.

Fig. 6. Micelle assay of native STM3605 protein and its mutants.

Lines 1-3 are controls with photoreaction center proteins (3 bands) - 1. Control, 2. detergent phase, 3. water phase. Lines 4-6 are for HEWL lysozyme - 4. Lysozyme control, 5. detergent phase, 6. water phase, lines 7-9 are for WT STM3605 - 7. WT STM3605 control, 8. detergent phase, 9. water phase, lines 10-12 are for STM3605 Q20E single mutant – 10. Q20E control, 11. detergent phase, 12. water phase and lines 13-15 are for STM3605 Q20E/V35T double mutant – 13. Q20E/V35T control, 14. detergent phase, 15. water phase.

DISCUSSION

The genome of S. Typhimurium strain LT2 contains three lysozyme-like proteins, including STM3605. The other two proteins are encoded on prophages Gifsy-2 (STM1028) and Fels-2 (STM2715), while the STM3605 gene is not near other phage genes. There is 44% similarity between STM3605 and STM1028 (E value 1e-05) and 47% similarity between STM3605 and STM2715 across a stretch of 85 amino acids (E value 1e-05). While there is some similarity between the N-termini, it is noteworthy that Gln20 of STM3605 is replaced with Glu20 that is the expected residue for the active form of the enzyme in the other two proteins. Multiple sequence alignments of STM3605 sequence neighbors from other enterobacteria as well as more distant homologs from Salmonella and phage highlight these distinctions (Fig. 7). Furthermore, while STM3605 appears to be an orphan phage enzyme relative to its genomic neighborhood, STM1028 and STM2715 are surrounded by numerous (15-25) phage-related genes, including, in both cases, a holin gene immediately adjacent to the lysozyme gene. Holins are phage-encoded small membrane proteins that permeabilize the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane to allow cytoplasmic endolysin to gain access to the peptidoglycan layer [38, 39]. The presence of both endolysin and holin in both cases suggests that these proteins may, indeed, function as peptidoglycan hydrolases. In contrast, STM3605 is surrounded by trehalase, a putative 60 kDa inner membrane protein, and transcriptional regulators. No phage-related genes occur in the vicinity. This genomic proximity is maintained not only for closely-related S. Typhimurium genomes containing proteins identical to STM3605 (e.g. S. Dublin, S. Newport, S. Paratyphi), but also for S. bongori that has a 90% similar protein. Among more divergent enterobacteria e.g. Enterobacter spp., there are homologs with ~60% amino acid similarity, and the gene synteny is similar but not identical. Interestingly, for these proteins, residue 20 is consistently glutamine (i.e., it is likely to be catalytically inactive), and no putative holin could be found in the vicinity. Therefore it is suggestive that STM3605 function does not require hydrolytic activity. In fact, within the lysozyme family nonenzymatic functions have already been reported. For example, it has been demonstrated that T4 lysozyme, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens phage endolysin as well as hen egg white lysozyme with abolished hydrolytic activity preserve their antimicrobial function due to membrane disrupting ability [35, 36]. Bactericidal action of partially unfolded proteins relies on the insertion of the C-terminal amphipathic helix H10 (in T4) into the cell membrane leading to its subsequent disintegration. This strategy resembles the mechanism by which many antimicrobial peptides operate (reviewed in [40]).

Fig. 7.

Multiple sequence alignment of STM3605 and its homologs: the other two lysozyme-like proteins in S. Typhimurium as well as T4 and P22 phage lysozymes. Sequence identity between STM3605 and the other sequences in this alignment is less than 30%.

Nonetheless, STM3605 is expressed in Salmonella under multiple growth conditions in vitro (unpublished microarray results) and during infection of macrophages and HeLa cells. Expression does not appear to be significantly altered under these conditions, relative to growth in LB medium to exponential phase [41]. While determined to be expressed by mRNA presence, demonstration of translation remains to be determined. Hence, the role of this protein in Salmonella remains to be deduced, but we conclude that its function is not hydrolytic. Our data suggest that STM3605 can partition into micelles, suggesting that its function may possibly involve association with some subcellular membrane structures. Beyond this, STM3605 inhibited the growth of M. luteus, leading us to speculate that STM3605 may be deployed as a potential deterrent to other bacterial flora during infection of its mammalian host. Efforts to restore enzyme function by introduction mutations into active were unsuccessful but resulted in reduced partitioning into micelles and less effective inhibition of M. luteus growth.

Despite our inability to define a specific functional role of STM3605, from the observed sequence conservation, gene synteny, stable folded structure, and biochemical results we suggest STM3605 is not simply a relic of an ancient phage infection, but rather has been adopted by and indeed is now beneficial to descendants of the original host species. Other examples of proteins lacking conserved residues known to be required for activity in the great majority of their homologs have been noted [42]; presumably these proteins retain an additional or alternate function that is unrelated to the missing conserved residues and, in the case of STM3605 intriguingly may be speculated as being protective during infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the Midwest Center for Structural Biology and Structural Biology Center for their support. This research has been funded in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health GM094585 (AJ), GM094623 (JNA), and by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. The authors wish to thank Gekleng Chhor for proofreading of this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Rmsd

root-mean-square deviation

- SAD

single-wavelength anomalous diffraction

- SVM

support vector machine

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The submitted manuscript has been created by UChicago Argonne, LLC, Operator of Argonne National Laboratory (“Argonne”). Argonne, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, is operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The U.S. Government retains for itself, and others acting on its behalf, a paid-up nonexclusive, irrevocable worldwide license in said article to reproduce, prepare derivative works, distribute copies to the public, and perform publicly and display publicly, by or on behalf of the Government.

References

- 1.Young I, Wang I, Roof WD. Phages will out: strategies of host cell lysis. Trends in microbiology. 2000;8(3):120–128. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacob F, Fuerst CR. The mechanism of lysis by phage studied with defective lysogenic bacteria. Journal of general microbiology. 1958;18(2):518–526. doi: 10.1099/00221287-18-2-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanamaru S, Ishiwata Y, Suzuki T, Rossmann MG, Arisaka F. Control of bacteriophage T4 tail lysozyme activity during the infection process. Journal of molecular biology. 2005;346(4):1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loessner MJ. Bacteriophage endolysins--current state of research and applications. Current opinion in microbiology. 2005;8(4):480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borysowski J, Weber-Dabrowska B, Gorski A. Bacteriophage endolysins as a novel class of antibacterial agents. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231(4):366–377. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClelland M, Sanderson KE, Spieth J, Clifton SW, Latreille P, Courtney L, Porwollik S, Ali J, Dante M, Du F, et al. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature. 2001;413(6858):852–856. doi: 10.1038/35101614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nature methods. 2011;8(10):785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. Journal of molecular biology. 2004;338(5):1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galan JE, Wolf-Watz H. Protein delivery into eukaryotic cells by type III secretion machines. Nature. 2006;444(7119):567–573. doi: 10.1038/nature05272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samudrala R, Heffron F, McDermott JE. Accurate prediction of secreted substrates and identification of a conserved putative secretion signal for type III secretion systems. PLoS pathogens. 2009;5(4):e1000375. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott JE, Corrigan A, Peterson E, Oehmen C, Niemann G, Cambronne ED, Sharp D, Adkins JN, Samudrala R, Heffron F. Computational prediction of type III and IV secreted effectors in gram-negative bacteria. Infection and immunity. 2011;79(1):23–32. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00537-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jehl MA, Arnold R, Rattei T. Effective--a database of predicted secreted bacterial proteins. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(Database issue):D591–595. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X, Studier FW. Multiple roles of T7 RNA polymerase and T7 lysozyme during bacteriophage T7 infection. Journal of molecular biology. 2004;340(4):707–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim Y, Babnigg G, Jedrzejczak R, Eschenfeldt WH, Li H, Maltseva N, Hatzos-Skintges C, Gu M, Makowska-Grzyska M, Wu R, et al. High-throughput protein purification and quality assessment for crystallization. Methods. 2011;55(1):12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klock HE, Lesley SA. The Polymerase Incomplete Primer Extension (PIPE) method applied to high-throughput cloning and site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;498:91–103. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-196-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dieckman L, Gu M, Stols L, Donnelly MI, Collart FR. High throughput methods for gene cloning and expression. Protein expression and purification. 2002;25(1):1–7. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnelly MI, Zhou M, Millard CS, Clancy S, Stols L, Eschenfeldt WH, Collart FR, Joachimiak A. An expression vector tailored for large-scale, high-throughput purification of recombinant proteins. Protein expression and purification. 2006;47(2):446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y, Quartey P, Li H, Volkart L, Hatzos C, Chang C, Nocek B, Cuff M, Osipiuk J, Tan K, et al. Large-scale evaluation of protein reductive methylation for improving protein crystallization. Nature methods. 2008;5(10):853–854. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1008-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution--from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2006;62(Pt 8):859–866. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.French S, Wilson K. Treatment of Negative Intensity Observations. Acta Crystallographica Section A. 1978 Jul;34:517–525. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer G, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nature protocols. 2008;3(7):1171–1179. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bricogne G, Blanc E, Brandl M, Flensburg C, Keller P, Paciorek W, Roversi P, Sharff A, Smart OS, Vonrhein C, et al. BUSTER version 2.10.0. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Global Phasing Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, Lopez R. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W116–120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuff AL, Sillitoe I, Lewis T, Clegg AB, Rentzsch R, Furnham N, Pellegrini-Calace M, Jones D, Thornton J, Orengo CA. Extending CATH: increasing coverage of the protein structure universe and linking structure with function. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(Database issue):D420–426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holm L, Rosenstrom P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W545–549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laskowski RA, Watson JD, Thornton JM. ProFunc: a server for predicting protein function from 3D structure. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W89–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. Journal of molecular biology. 2007;372(3):774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anand NN, Stephen ER, Narang SA. Mutation of Active-Site Residues in Synthetic T4-Lysozyme Gene and Their Effect on Lytic Activity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1988;153(2):862–868. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malcolm BA, Rosenberg S, Corey MJ, Allen JS, de Baetselier A, Kirsch JF. Site-directed mutagenesis of the catalytic residues Asp-52 and Glu-35 of chicken egg white lysozyme. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86(1):133–137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weaver LH, Grutter MG, Matthews BW. The refined structures of goose lysozyme and its complex with a bound trisaccharide show that the “goose-type” lysozymes lack a catalytic aspartate residue. Journal of molecular biology. 1995;245(1):54–68. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(95)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rennell D, Bouvier SE, Hardy LW, Poteete AR. Systematic Mutation of Bacteriophage-T4 Lysozyme. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1991;222(1):67–87. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90738-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuroki R, Weaver LH, Matthews BW. A covalent enzyme-substrate intermediate with saccharide distortion in a mutant T4 lysozyme. Science. 1993;262(5142):2030–2033. doi: 10.1126/science.8266098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.During K, Porsch P, Mahn A, Brinkmann O, Gieffers W. The non-enzymatic microbicidal activity of lysozymes. FEBS letters. 1999;449(2-3):93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orito Y, Morita M, Hori K, Unno H, Tanji Y. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens phage endolysin can enhance permeability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane and induce cell lysis. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2004;65(1):105–109. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de la Vara LEG, Alfaro BL. Separation of membrane proteins according to their hydropathy by serial phase partitioning with Triton X-114. Analytical Biochemistry. 2009;387(2):280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young R, Blasi U. Holins: form and function in bacteriophage lysis. FEMS microbiology reviews. 1995;17(1-2):191–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang IN, Smith DL, Young R. Holins: the protein clocks of bacteriophage infections. Annual review of microbiology. 2000;54:799–825. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeaman MR, Yount NY. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacological reviews. 2003;55(1):27–55. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hautefort I, Thompson A, Eriksson-Ygberg S, Parker ML, Lucchini S, Danino V, Bongaerts RJ, Ahmad N, Rhen M, Hinton JC. During infection of epithelial cells Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium undergoes a time-dependent transcriptional adaptation that results in simultaneous expression of three type 3 secretion systems. Cellular microbiology. 2008;10(4):958–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grimm F, Cort JR, Dahl C. DsrR, a novel IscA-like protein lacking iron- and Fe-S-binding functions, involved in the regulation of sulfur oxidation in Allochromatium vinosum. Journal of bacteriology. 2010;192(6):1652–1661. doi: 10.1128/JB.01269-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laskowski RA. SURFNET: a program for visualizing molecular surfaces, cavities, and intermolecular interactions. Journal of molecular graphics. 1995;13(5):323–330. 307–328. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(95)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]