Abstract

Myosin II is important for normal cytokinesis and cell wall maintenance in yeast cells. Myosin II-deficient (myo1) strains of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae are hypersensitive to nikkomycin Z (NZ), a competitive inhibitor of chitin synthase III (Chs3p), a phenotype that is consistent with compromised cell wall integrity in this mutant. To explain this observation, we hypothesized that the absence of myosin type II will alter the normal levels of proteins that regulate cell wall integrity and that this deficiency can be overcome by the overexpression of their corresponding genes. We further hypothesized that such genes would restore normal (wild-type) NZ resistance. A haploid myo1 strain was transformed with a yeast pRS316-GAL1-cDNA expression library and the cells were positively selected with an inhibitory dose of NZ. We found that high expression of the ubiquitin-conjugating protein cDNA, UBC4, restores NZ resistance to myo1 cells. Downregulation of the cell wall stress pathway and changes in cell wall properties in these cells suggested that changes in cell wall architecture were induced by overexpression of UBC4. UBC4-dependent resistance to NZ in myo1 cells was not prevented by the proteasome inhibitor clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone and required the expression of the vacuolar protein sorting gene VPS4, suggesting that rescue of cell wall integrity involves sorting of ubiquitinated proteins to the PVC/LE–vacuole pathway. These results point to Ubc4p as an important enzyme in the process of cell wall remodelling in myo1 cells.

Keywords: yeast, MYO1, UBC4, CHS3, nikkomycin Z, ubiquitin

Introduction

Cell wall composition and architecture in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is significantly altered by Myo1p deficiency (Cruz et al., 2000; Rios Munoz et al., 2003; Rodriguez and Paterson, 1990; Rodriguez-Medina et al., 1998). Absence of the actomyosin ring in yeast caused by a deletion of the MYO1 gene activates a functionally redundant cytokinesis pathway, regulated by a cytoskeletal binding protein Hof1p (Korinek et al., 2000; Vallen et al., 2000). This mechanism requires increased deposition of chitin at the bud neck by chitin synthase III (CSIII) (Schmidt et al., 2002; Tolliday et al., 2003). CSIII (also called Chs3p, for its catalytic subunit) is also required for maintenance of lateral cell wall chitin synthesis and for chitin ring formation at the bud site during G1 phase (Shaw et al., 1991). Consequently, a deletion of CHS3 causes a synthetic growth defect in most myo1 strains (Schmidt et al., 2002) and hypersensitivity to low doses of nikkomycin Z (NZ), an irreversible competitive inhibitor of CSIII (Rivera-Molina et al., 2006).

To better understand this relation between CSIII and cell wall integrity in myo1 strains, a positive screen was conducted to identify cDNAs that could suppress the hypersensitivity to NZ. A total of 14 cDNAs were identified that conferred high levels (80–100%) of NZ resistance (see Table 1). In anticipation that interactions might already be described between myo1 and/or chs3 mutations and genes identified by our screen, we searched in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Genome Database (SGD) (http://www.yeastgenome.org/). We found that a total of 10 synthetic lethal interactions (Breton and Aigle, 1998; Davierwala et al., 2005; Roumanie et al., 2000; Vallen et al., 2000; Wang and Bretscher, 1995) and two synthetic growth interactions (Lillie and Brown, 1998) have been previously described for myo1, while 76 synthetic lethal (Friesen et al., 2006; Goehring et al., 2003; Lesage et al., 2005; Tong et al., 2004) and two synthetic growth interactions (Castrejon et al., 2006; Sobering et al., 2004) have been previously described for chs3. There were no common synthetic lethal or synthetic growth interactions described between myo1 and chs3 in the SGD, although we and others have reported a synthetic growth interaction (Rivera-Molina et al., 2006; Schmidt et al., 2002). Deletions of smi1 or fks1 were found to have synthetic lethal interactions with chs3 and ubc4 (Lesage et al., 2005; Tong et al., 2004). The latter is a gene encoding a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) that was isolated by our genetic screen. No interactions have been previously reported between Myo1p and Ubc4p.

Table 1.

Identification of cDNAs whose overexpression confers NZ-resistance to myo1 cells

| Systematic name | Gene | Redundancy (No. of clones) | NZ resistance (%) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YPL177C | CUP9 | 1 | 84.2 | Homeodomain-containing transcriptional repressor of PTR2, which encodes a major peptide transporter; imported peptides activate ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis, resulting in degradation of Cup9p and de-repression of PTR2 transcription |

| YGR175C | ERG1 | 1 | 81 | Squalene epoxidase, catalyses the epoxidation of squalene to 2,3-oxidosqualene; plays an essential role in the ergosterol-biosynthesis pathway and is the specific target of the antifungal drug terbinafine |

| YMR043W | MCM1; FUN80 | 1 | 92.5 | Transcription factor involved in cell-type-specific transcription and pheromone response; plays a central role in the formation of both repressor and activator complexes |

| YOL126C | MDH2 | 1 | 80 | Cytoplasmic malate dehydrogenase, one of the three isozymes that catalyse interconversion of malate and oxaloacetate; involved in gluconeogenesis during growth on ethanol or acetate as carbon source; interacts with Pck1p and Fbp1p |

| YOL064C | MET22 | 1 | 100 | Bisphosphate-3′-nucleotidase, involved in salt tolerance and methionine biogenesis; dephosphorylates 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate and 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate, intermediates of the sulphate assimilation pathway |

| YDR505C | PSP1; GIN5 | 1 | 91.9 | Asn and gln rich protein of unknown function; high-copy suppressor of POL1 (DNA polymerase-α) and partial suppressor of CDC2 (polymerase delta) and CDC6 (pre-RC loading factor) mutations; overexpression results in growth inhibition |

| YDR382W | RPP2B; RPL45; YPA1 | 3 | 87.9 | Ribosomal protein P2-β, a component of the ribosomal stalk, which is involved in the interaction between translational elongation factors and the ribosome; regulates the accumulation of P1 (Rpp1Ap and Rpp1Bp) in the cytoplasm |

| YHL015W | RPS20; URP2 | 1 | 93 | Protein component of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit; overproduction suppresses mutations affecting RNA polymerase III-dependent transcription; has similarity to E. coli S10 and rat S20 ribosomal proteins |

| YER074W | RPS24A; RPS24EA | 1 | 89.6 | Protein component of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit; identical to Rps24Bp and has similarity to rat S24 ribosomal protein |

| YOR182C | RPS30B | 1 | 83.6 | Protein component of the small (40S) ribosomal subunit; nearly identical to Rps30Ap and has similarity to rat S30 ribosomal protein |

| YPL237W | SUI3 | 2 | 100 | β-subunit of the translation initiation factor eIF2, involved in the identification of the start codon; proposed to be involved in mRNA binding |

| YDR177W | UBC1 | 1 | 81.1 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that mediates selective degradation of short-lived and abnormal proteins; plays a role in vesicle biogenesis and ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD); component of the cellular stress response |

| YBR082C | UBC4 | 4 | 87.9 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that mediates degradation of short-lived and abnormal proteins; interacts with E3-CaM in ubiquitinating calmodulin; interacts with many SCF ubiquitin protein ligases; component of the cellular stress response |

| YDR495C | VPS3; PEP6; VPL3; VPT17 | 1 | 96.6 | Cytoplasmic protein required for the sorting and processing of soluble vacuolar proteins, acidification of the vacuolar lumen, and assembly of the vacuolar H+-ATPase |

The ubiquitin (Ub) pathway has been shown to be involved in targeting of most plasma membrane (PM) proteins for entrance to the endocytic pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Hicke, 1997; Hicke et al., 1997). Yeast cells can employ both poly-Ub and mono-Ub signals to regulate traffic of transmembrane proteins. For example, yeast cells can use mono-ubiquitination to regulate entry of an integral membrane protein at the plasma membrane to the endocytic pathway and, once in the early endosome, it may determine whether the protein will be recycled to the PM or directed to the vacuole for proteolysis (Kolling and Losko, 1997; Strous and Govers, 1999).

Ubc4p has a key function as a stress-related Ub-conjugating enzyme in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Arnason and Ellison, 1994; Chuang and Madura, 2005) by mediating the selective proteasomal degradation of short-lived and abnormal damaged proteins (Chuang and Madura, 2005) and the ubiquitination of multiple vesicular body (MVB) cargoes for degradation in the vacuole (Seufert and Jentsch, 1990). Requirement of Ubc4p for sorting of membrane proteins into multivesicular bodies [named pre-vacuolar compartment/late endosome (PVC/LE) in yeast] is of particular interest because it has been proposed that Chs3p traffic may be deviated from the recycling compartment to the vacuole in myo1 cells (Rivera-Molina, 2005). Ubc4p also interacts with other cell wall-related proteins, such as Fks1p and Smi1p (Tongaonkar et al., 2000), further supporting the involvement of Ubc4p in cell wall biogenesis. Another interesting connection between Ubc4p and cell wall biogenesis is its physical interaction with the E3 ligase UFD4 (Ho et al., 2002). UFD4 has a synthetic interaction with CHS5 (Lesage et al., 2004) that encodes a protein that regulates Chs3p traffic (Santos and Snyder, 1997). Of the proteins identified to have ubiquitination sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Ho et al., 2002), several are related to functions in cell wall biogenesis (Chs3p, Gsc2p, Lsb1p, Sna3p), endocytosis (Akl1p, Rvs167p, Snc1/2p), exocytosis (Ddi1p, Exo84p), ubiquitination (Cue5p, Ubr2p), and vacuolar import of proteins (Ssa2p). This relationship further emphasizes the importance of studying Ubc4p as a central stress-related E2 enzyme that may interact with these and other cell wall stress-related proteins to restore cell wall integrity in myo1 strains.

In this study we investigated the relation of Ubc4p to the restoration of normal resistance to NZ in a hypersensitive myo1 strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We found that Ubc4p overexpression produced a downregulation of the Pkc1p-mediated cell wall integrity pathway (CWIP). However, it did not restore the normal β-1,3-glucanase sensitivity profile or the wild-type pattern of chitin distribution to the myo1 strains, suggesting that the restoration of cell wall integrity involves other changes in the cell wall structure and/or composition not related to chitin synthesis. We demonstrate that these proposed cell wall changes require the VPS4 gene product, suggesting that the PVC-to-vacuole targeting of ubiquitinated proteins is important for this process. These results point to Ubc4p as an important enzyme in the process of cell wall remodelling in myo1 cells.

Materials and methods

Construction of strains, plasmids, media, and drugs

myo1 Δ::HIS5 strain YJR6 was generated from the parental haploid wild-type (wt) strain MGD353-46D by homologous recombination, using a PCR-based method (Longtine et al., 1998). The YJR6 and BY4741 (ATCC #201 388) strains were crossed to generate a heterozygous diploid strain from which wt (YJR12) and myo1 (YJR13) spores were germinated. All strains used in this study (Table 2) were transformed using the LiOAc method (Ito et al., 1983). The vps4 strain (YJR44) was generated by transforming the YJR12 strain with a KANMX4 selectable marker to replace the chromosomal VPS4 gene by homologous recombination (Longtine et al., 1998).

Table 2.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Name | Genotype | Plasmid source |

|---|---|---|---|

| YJR12 | MAT α trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR | ||

| YJR13 | MAT a trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR myo1 Δ::HIS5 | ||

| YJR13pRS316-GAL1-UBC4 | myo1pUBC4 | MAT a trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR myo1 Δ::HIS5 | A. Brestcher |

| YJR13pFR23-MET25-UBC4 | myo1 pMETUBC4 | MAT a trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR myo1 Δ::HIS5 | This study |

| YJR13pRS316blank | myo1 | MAT a trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR myo1 Δ::HIS5 | ATCC #77145 |

| YJR13pRS316-MYO1 | wt | MAT a trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR myo1 Δ::HIS5 | F. Rivera |

| YJR12pRS316-GAL1-UBC4 | wtpUBC4 | MAT α trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR | A. Brestcher |

| YJR12pFR23-MET25-UBC4 | wt pMETUBC4 | MAT α trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR | This study |

| YJR47 | myo1 ubc4 | MAT a trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR myo1 Δ::HIS5 ubc4 Δ::kanMX4 | |

| YJR45 | myo1 vps4 | MAT α trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR myo1 Δ::HIS5 vps4 Δ::kanMX4 | |

| YJR45pRS316-GAL1-UBC4 | myo1 vps4 pUBC4 | MAT α trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR myo1 Δ::HIS5 vps4 Δ::kanMX4 | A. Brestcher |

| ATCC # 4003219 | ubc4 | MAT a his3delta1 leu2delta0 met15delta0 ura3delta0 deltaUBC4 | |

| YJR44 | vps4 | MAT α trp1 ura3 leu2–3, his3delta1 cyhR vps4 Δ::kanMX4 |

To obtain the myo1 vps4 strain (YJR45), the vps4 strain was transformed with a myo1 deletion cassette containing the Schizosaccharomyces pombe HIS5 gene flanked by MYO1 sequences that were obtained, using primers FDMYO1 (5′-GGAAAAATATTCACAGGGTAATG-3′) and RDMYO1 (5′-TGGTTTTGAACAACTTTAGCA-GT-3′). A UBC4 deletion cassette was obtained from ubc4 strain (ATCC 4 003 219), using primers UBC4F (5′-AGGGTAACTGCACTATTCATATG-TC-′) and UBC4R (5′-TTGATTACATATACTAG-CTATGCGT-3′) and used to transform the myo1 strain YJR13pRS316-MYO1. The myo1 ubc4 pRS316-MYO1 strain obtained was incubated on CSM glucose plates with 1 mg/ml 5FOA (Zymo Research), from which the myo1 ubc4 strain was selected and subsequently confirmed by PCR.

Experiments were carried out in complete synthetic media (CSM) or selective media (BIO101) or YPD (yeast extract/peptone/dextrose) (Becton Dickinson and Co.). Culture media were supplemented with 2% glucose (glu) or 2% galactose (gal) (Sigma) and 1× nitrogen base without amino acids (Difco, Becton Dickinson and Co.) at 25 °C. The proteasome inhibitor clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (Calbiochem) was reconstituted in DMSO and used at a concentration of 10 μM. Nikkomycin Z (Sigma) was used at concentrations previously determined for agar (30 μg/ml) and broth (6.25 μM) media (Rivera-Molina et al., 2006).

Positive screen for suppression of NZ-induced lethality in myo1 cells

Haploid myo1 cells transformed with a galactose-inducible expression library (pRS316-GAL1-cDNA; Liu et al., 1992) were positively selected for growth in selective agar plates containing 30 μg/ml NZ. NZ resistance was then verified in a liquid culture assay format in which 1 × 105 cells/ml transformed cells and their controls were incubated in ura− glu, ura− glu NZ (6.25 μM), ura− gal, and ura− gal NZ (6.25 μM) broth medium at 26 °C and 225 r.p.m. The OD600nm was determined at 24 and 48 h. Resistant strains were scored as those with 80% or greater resistance to 6.25 μM NZ, calculated as: (OD600nm treated/OD600nm untreated) × 100. The transformed strains were ‘cured’ of their plasmids by incubation in YPD liquid media for 48 h and then in CSM with 1 mg/ml 5FOA (Zymo Research) agar plates at 26 °C for 3 days, to confirm that NZ resistance was dependent on plasmid expression. To assess the integrity of each cDNA clone, they were isolated from Escherichia coli cultures for identification by DNA sequencing (ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyser, Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA).

Determination of chitin content

Cell wall chitin content of wt, wtpUBC4, myo1, myo1 ubc4 and myo1pUBC4 strains grown in ura− gal medium at 26 °C and 225 r.p.m. for 48 h, was determined through a modified Morgan–Elson assay, as described elsewhere (Wheat, 1966). The UBC4 mutants were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and stained with Calcofluor white (Fluorescent Brightener 28, Sigma) for a qualitative assay of their cell wall chitin distribution compared to myo1 and wt strains grown in ura− gal medium. Microscopic analysis was performed using an Olympus UV fluorescence microscope equipped with a UV filter (Set I. D. 31 001, Ex. D480 nm/30×, Em. D535 nm/40 m; Chroma Technology) and images captured with a Spot RT-cooled CCD camera.

Western blot analysis of phospho-Slt2p and Slt2p

wt, wtpUBC4, myo1, myo1 ubc4 and myo1pUBC4 strains were grown in selective media with 2% glucose or 2% galactose and harvested at OD600nm = 0.5–0.8 absorbance units (AU) for total protein extraction. Aliquots equivalent to 12 AU were centrifuged and washed with ice-cold water, recentrifuged and resuspended with 350 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X100, 0.1% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (50× stock; Roche), 5× PMSF (100× stock; EtOH), 1× Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail I (100× stock; Sigma), and 1× Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail II (100× stock; Sigma). The cells were broken by vortexing three times with acid-washed glass beads for 20 s while maintaining the tubes on ice between intervals. The extracts were centrifuged at 13 000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed to a new microcentrifuge tube and protein concentrations were determined by the DC Protein Assay method (BioRad). Samples containing 75 μg total protein were separated in a 10% SDS–PAGE gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane at 130 mA for 16 h at 4 °C (Bio-Rad Trans-blot). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against human phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase (recognizing Yeast phospho Slt2p) (Cell Signalling Technology) and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Yeast MAP kinase 1 (Slt2p/Mpk1p) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used at a dilution of 1/1000. Alternatively, a mouse monoclonal antibody against Pgk1p (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) was also used at a 1/125 dilution to ascertain equal loading.

β-1,3-glucanase assays

wt (YJR12), wtpMETUBC4, myo1 (YJR13), myo1 ubc4, and myo1pMETUBC4 cells were cultured respectively in selective glucose medium to OD600nm = 0.5–0.8 AU for a modified β-1,3-glucanase sensitivity assay (Yin et al., 2005). Culture aliquots equivalent to 1 × 107 cells/ml were centrifuged at 1800 × g at 4 °C for 5 min and the cell pellets were washed with 1 ml Tris–HCl, 50 mM, pH 7.4. The pelleted cells were gently resuspended in 1 ml Tris–HCl 50 mM, 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.4, and incubated for 1 h at 25 °C. After determining the initial OD600nm (t0), 120 U Quantazyme (Quantum Biotechnologies) were added and the sample was incubated at 25 °C. OD600nm measurements were taken at 15 min intervals for a total of 75 min. Cell lysis was determined by following the decrease in turbidity of the cell sample relative to the untreated control over time. The relative β-1,3-glucanase sensitivity was expressed as (OD600nm after treatment/OD600nm before treatment). The resistance : sensitivity ratio was expressed as (t75 OD600nm/t0 OD600nm).

Zymolyase assay

The same strains as above were incubated in selective glucose medium to OD600nm = 0.5–0.8 AU and culture aliquots equivalent to 1 × 107 cells/ml were used for a zymolyase resistance/sensitivity assay (http://mips.gsf.de/proj/eurofan/eurofan2/n7/protocols.html). The cell pellets were washed and resuspended in 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, and zymolyase 20T (ICN Biochemicals) was added to a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. After an initial OD600nm measurement, samples were incubated at 37 °C and OD600nm measurements were taken every hour for up to 4 h. A strain was considered sensitive to zymolyase when the final OD600nm was 51% or less compared to the initial OD600nm and was considered resistant when this value was 95% or higher. Percentages within this range depicted a strain with intermediate resistance. The resistance : sensitivity ratio was expressed as (t240 OD600nm/t0 OD600nm).

Proteasome inhibition

Preliminary assays determined an IC50 of 10 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (β-lactone) for myo1 and wt cultures. The effectiveness of the 10 μM β-lactone concentration in partially inhibiting the proteasome was assessed by Western blot to determine poly-ubiquitination levels in myo1 and wt total protein extracts (data not shown). Cultures containing 1 × 105 cells/ml of strains wt, wtpUBC4, myo1, myo1 ubc4, and myo1pUBC4 were grown in ura− gal, ura− gal NZ (6.25 μM), ura− gal β-lactone (10 μM), and ura− gal NZ (6.25 μM) plus β-lactone (10 μM) media. Their cell density was determined at OD600nm after 48 h incubation at 26 °C and 225 r.p.m.

NZ resistance/sensitivity assay for a myo1 vps4 pUBC4 strain

A myo1 vps4 pUBC4 strain was subjected to a NZ resistance/sensitivity assay along with strains wt, myo1, myo1pUBC4, myo1 vps4, and vps4. Starting with 1 × 107 cells/ml, aliquots taken from each culture at OD600nm = 0.5–0.8 AU, 5 μl from 1/10 serial dilutions (107 - 102 cells/ml) were inoculated in their respective selective plates and selective plates containing 30 μg/ml NZ. The plates were incubated at 27 °C for 4 days before assessing growth.

Results

Overexpression of UBC4 confers NZ resistance to a myo1 strain

A positive screen for the suppression of NZ-induced lethality in myo1 cells identified a total of 120 cDNA clones, of which 14 conferred high (80–100%) NZ resistance (Table 1). These were identified by DNA sequencing and classified according to function (Comprehensive Yeast Genome Database: http://mips.gsf.de/genre/proj/yeast/index.jsp). Most of the gene products (10/14) were categorized under protein biogenesis functions related to transcription (CUP9, MCM1), protein biosynthesis (RPP2B, RPS20, RPS24A, RPS30), translation (SUI3), protein transport (VPS3) and protein fate (UBC1, UBC4).

Of these 14 cDNAs that conferred high NZ resistance, UBC4 was selected for further studies because of its known interactions with the chitin synthase III and glucan synthase pathways (Firon et al., 2004), two important cell wall components in yeast. Redundant NZ resistance assays for the transformed strain myo1pUBC4 and the ‘cured’ strain (see Materials and methods) confirmed that overexpression of the UBC4 cDNA confers NZ resistance to the myo1 strain (data not shown).

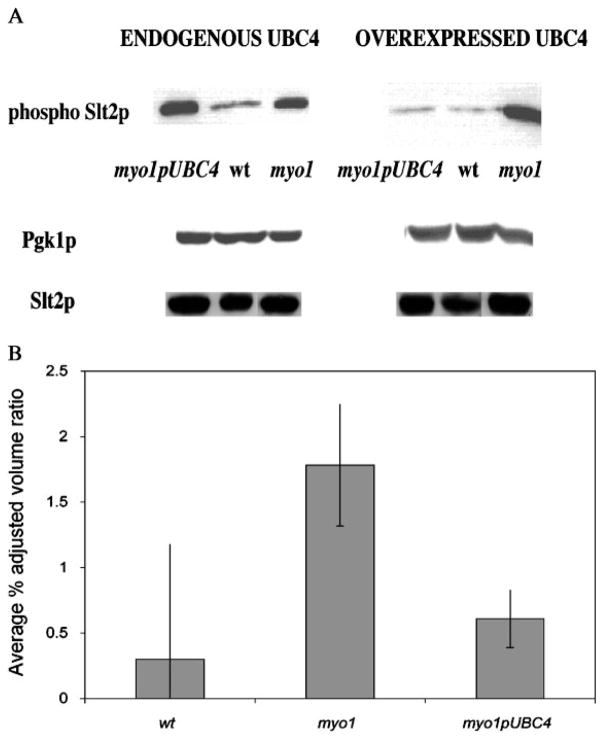

myo1 cells overexpressing UBC4 maintain the delocalized chitin phenotype

To evaluate the effect that UBC4 overexpression may have on chitin deposition and budding pattern, the wt, wtpUBC4, myo1, myo1 ubc4 and myo1pUBC4 strains were assessed for total cell wall chitin content and chitin distribution. We observed that myo1 cells overexpressing UBC4 maintain the same delocalized chitin deposition typical of the myo1 strain (Figure 1). While the wt cells concentrate the Calcofluor white fluorescence discretely in the bud neck, the fluorescence is more widely distributed along the cell wall in both myo1 and myo1pUBC4 cells. These latter strains, as well as the myo1 ubc4 strain, exhibit thicker chitin depositions in their secondary septa.

Figure 1.

Visualization of chitin distribution by staining with Calcofluor white. myo1pUBC4, myo1, myo1 ubc4, wt and wtpUBC4 cells were cultured in ura− gal medium, fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and stained with Calcofluor white. Light microscopy images are presented in the upper panels. Below each bright-field image is the corresponding fluorescence micrograph. Bar = 5 μm

The budding pattern of both myo1 and myo1p-UBC4 strains was also very similar (Table 3), with a larger percentage of cells exhibiting abnormal non-axial (polar and hyper-polar) budding patterns relative to the wt control cells. These results suggest that overexpression of UBC4 did not reduce the activity of CSIII or restore its normal localization at the bud neck in the myo1 mutant. Interestingly, myo1 ubc4 strains exhibited a relatively large number of single-budded cells compared to its wt and myo1 counterparts, suggesting that bud growth or cell separation may also be affected in ubc4 strains. Overexpression of UBC4 did not affect chitin distribution and budding phenotype in the wt strain.

Table 3.

Budding pattern comparison

| Budding pattern | wt | wt pUBC4 | myo1 | myo1 pUBC4 | myo1 ubc4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Single buds | 15 | 9.8 | 16 | 13 | 52.6 |

| % Axial | 0.5 | 0.4 | 5 | 2 | 7.1 |

| % Non-axial | 0 | 0 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 11.9 |

200 budded cells studied from strains cultured in galactose media.

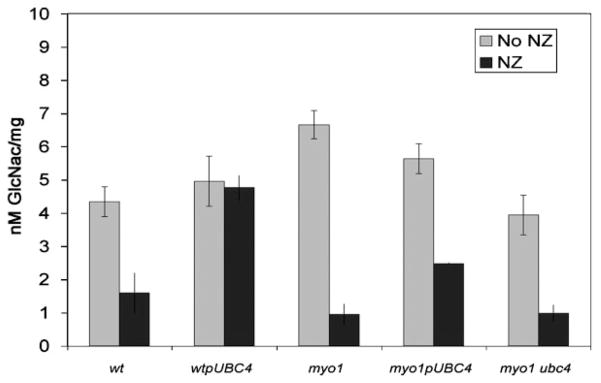

Quantification of total cell wall chitin content in these strains also showed that CSIII activity was relatively unchanged in the myo1pUBC4 strain and myo1 strains but was reduced dramatically in the myo1 ubc4 strain to levels similar to the wild-type controls (Figure 2). Overexpression of UBC4 in the wt strain did not affect the typical wild-type chitin content profile. All but the wtpUBC4 strain exhibited a dramatic reduction in chitin content when treated with NZ 6.25 μM (Figure 2), which demonstrates that NZ can be transported efficiently inside myo1 strains that overexpress UBC4 or that contain a ubc4 deletion.

Figure 2.

Measurement of chitin content in myo1pUBC4 cells. myo1pUBC4, myo1, myo1 ubc4, wt and wtpUBC4 cells were cultured in ura− gal and ura− gal NZ 6.25 μM media at 26 °C and 225 r.p.m. for 48 h before chitin content assessment. The results represent the average of three experiments

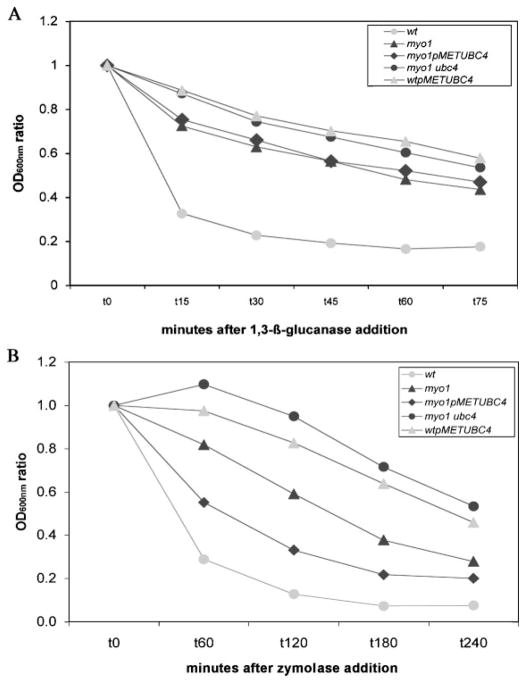

myo1 cells overexpressing UBC4 exhibit a downregulation of the Pkc1p-mediated cell wall integrity signalling pathway

In order to determine the CWIP status of myo1 cells overexpressing UBC4, the relative levels of phospho-Slt2p were assessed by Western blot analysis (Figure 3A). The results show a dramatic increase in the dual-phosphorylated Slt2p signal in myo1 strains when UBC4 is repressed by glucose. When transcription of the UBC4 cDNA was induced by galactose, the myo1pUBC4 strain exhibited a significant (p = 0.003) reduction in the dual phosphorylated Slt2p levels relative to the myo1 cells (Figure 3B). Preliminary results for the myo1 ubc4 and wtpUBC4 strains showed similar dual-phosphorylated Slt2p levels relative to the myo1 and wt strains, respectively (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Analysis of phospho-Slt2p steady-state levels. (A) Equal amounts of protein extracts prepared from myo1pUBC4, wt and myo1 cells cultured in ura− glu (endogenous UBC4) and ura− gal (overexpressed UBC4) media were analysed by Western blot, as described in Materials and methods. The Western blot was probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody against phospho p44/42 MAP kinase (phospho-Slt2p) (first row) and re-probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody against cytoplasmic Pgk1p (middle row) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Slt2p (bottom row) for loading controls. (B) Histograms show the average percentage adjusted volume ratio for blot results of strains cultured in ura− gal (overexpressed UBC4), as determined by densitometry analysis. The results represent the average of three experiments

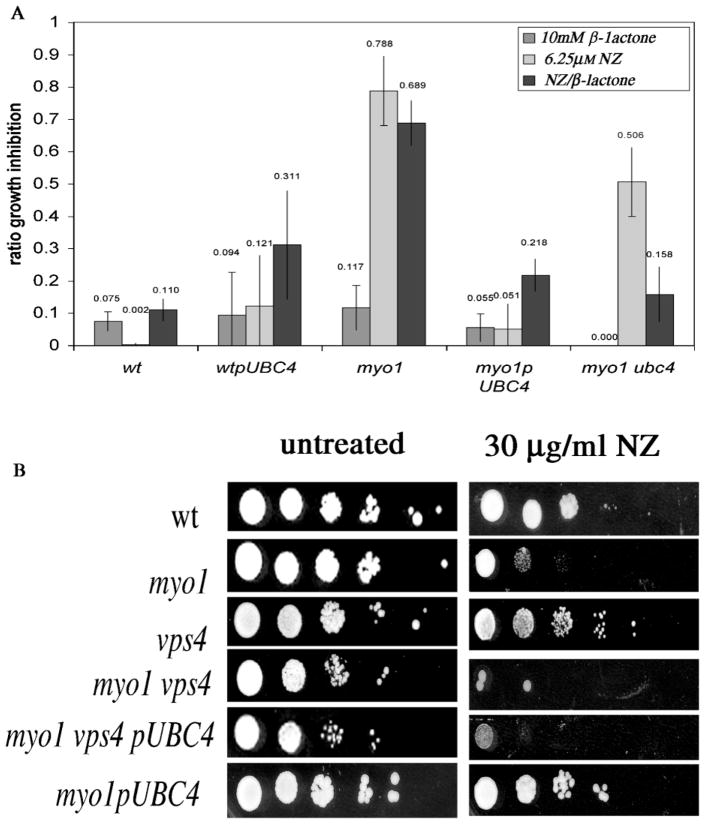

Overexpresssion of UBC4 does not change sensitivity to β-1,3-glucanase and zymolyase enzymes in myo1 strains

wtpMETUBC4, myo1 (YJR13), myo1 ubc4, and myo1pMETUBC4 strains subjected to a β-1,3-glucanase resistance : sensitivity assay (Figure 4A) presented similar levels of sensitivity to the enzyme (ranging from 0.43 to 0.56 resistance : sensitivity ratio), while the control wt exhibited a higher relative sensitivity (0.18). The relative sensitivity of the myo1 strain (0.43 ratio) comes as a surprise because other chitin mutants, such as gas1 and ecm33, have been shown to have much lower sensitivity to β-1,3-glucanase (Yin et al., 2005). This relative sensitivity to β-1,3-glucanase was not changed in either the myo1pUBC4 or myo1 ubc4 strains. Conversely, the relative sensitivity to β-1,3-glucanase was decreased in the wtpMET-UBC4 strain relative to the wt control strain.

Figure 4.

Determination of sensitivity profile to the enzymes β-1,3-glucanase and zymolyase. (A) myo1p-METUBC4, myo1 (YJR13), myo1 ubc4, wt (YJR12) and wtpMETUBC4 cells were incubated with 120 U β-1,3-glucanase at 25 °C for up to 75 min, as described in Materials and methods. To obtain their sensitivity profiles, the OD600nm ratio was determined by dividing the absorbance units at any time point by the absorbance units at t0. Chart presents the average of three experiments. (B) The same strains were incubated with 5 μg/ml zymolyase at 37 °C for up to 4 h, as described in Materials and methods. The OD600nm ratio was determined as decribed above. Chart presents the average data from three experiments

When all strains were subjected to a zymolyase resistance : sensitivity assay, they showed a broad range of resistance : sensitivity ratios, from 0.07 for the wt strain to 0.53 for the myo1 ubc4 strain (Figure 4B). It was noted that the myo1pMETUBC4 strain showed increased sensitivity to the enzyme relative to the myo1 strain, while the wtpMETUBC4 strain showed decreased sensitivity relative to the wt strain.

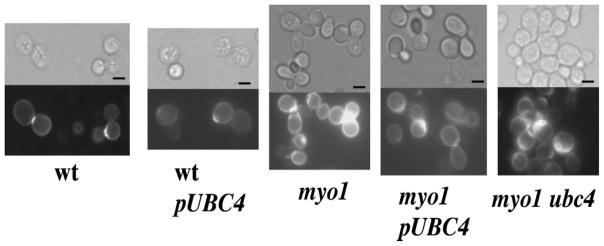

Rescue of NZ resistance by UBC4 requires the PVC-to-vacuole targeting pathway

In order to ascertain the role of the proteasome in the rescue of NZ resistance, the myo1pUBC4 strain was assayed for NZ resistance in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone (β-lactone) (Craiu et al., Fenteany and Schreiber, 1998; Lee and Goldberg, 1996). When wt, wtpUBC4, myo1, myo1 ubc4 and myo1pUBC4 strains were tested for NZ resistance in the presence of 10 μM β-lactone, the β-lactone alone had a mild effect on growth (growth inhibition ratio = 0.068 ± 0.044) in all strains (Figure 5A). The average results for experiments assaying the effects of 10 μM β-lactone on NZ resistance showed that the myo1pUBC4 strain maintained high levels of NZ resistance (0.78 resistance : sensitivity ratio) similar to wt control cells (0.89 resistance : sensitivity ratio) while the myo1 strain continued to exhibit the characteristic hypersensitivity to NZ (0.21 resistance : sensitivity ratio) (Figure 5A). This suggests that partial inhibition of proteasome function by 10 μM β-lactone does not affect the acquired resistance to NZ in myo1 cells overexpressing UBC 4. Surprisingly, resistance to NZ was enhanced by 10 μM β-lactone in the myo1 ubc4 strain.

Figure 5.

Assessment of the role of proteasome and PVC/LE pathways in acquired NZ resistance. (A) Effects of 10 μM β-lactone on NZ resistance of wt, myo1, myo1 cells overexpressing UBC4 (myo1pUBC4), myo1 ubc4 and wt cells overexpressing UBC4 (wtpUBC4). Strains with high NZ resistance show a low growth inhibition ratio and vice versa. The growth inhibition ratio was calculated as follows: OD600nm treated/OD600nm untreated. The chart represents the average of at least three experiments. (B) NZ resistance agar plate assays of the indicated strains were conducted by drop tests (from left to right, 107 – 102 cells/ml serial dilutions) on ura− gal agar plates (untreated) and ura− gal agar plates with 30 μg/ml NZ. NZ-resistant wild-type (wt) and myo1pUBC4 cells and sensitive myo1 cells were included as controls. The plates were incubated at 27 °C for 4 days before assessing growth and photographing

We tested the role of the PVC–LE-to-vacuole trafficking pathway in the restoration of cell wall integrity of myo1 cells by assessing NZ resistance in a myo1 vps4 pUBC4 strain. A VPS4 deletion causes a block in the trans-Golgi network (TGN)-to-pre-vacuolar PVC/LE traffic and therefore prevents the downstream traffic between the PVC/LE and vacuole. The results of NZ resistance assays (Figure 5B) revealed that the myo1 vps4 pUBC4 strain was hypersensitive, as were myo1 vps4 and myo1 strains, while the control vps4 and wt strains exhibited resistance.

Discussion

The overrepresentation of cDNAs coding for proteins participating in protein synthesis and metabolism functional pathways identified by our NZ resistance screen (Table 1) supports our original hypothesis that the absence of myosin II will alter the normal levels of proteins involved in cell wall integrity. To explain the observed results, we speculate that for a myo1 strain, the level of these proteins required for the synthesis and metabolism of all cellular proteins could be depleted to an extent that it also produces a decrease in the synthesis of cell wall proteins. Evidently, the restoration of cell wall integrity by UBC4 dosage rescue (as well as by any of the other proteins listed in Table 1) can produce a compensatory effect at the cell wall level. Indeed, several of these genes that confer 80–100% NZ resistance to the myo1 strain may be involved directly or indirectly in cell wall protein synthesis and/or its regulation. Moreover, the conjugating enzymes UBC1 and UBC4 may also have a regulatory role in restoration of cell wall integrity in the myo1 strain through their involvement in the cellular stress response (Seufert and Jentsch, 1990). However, we observed that the UBC4 gene was not essential for cell viability (data not shown).

MYO1 gene disruption causes cells to lose their haploid-specific budding pattern and exhibit abnormal chitin deposition at the mother–bud neck (Rodriguez and Paterson, 1990). Dosage rescue by UBC4 did not affect the chitin distribution or budding patterns typical of the myo1 strains, suggesting that the chitin synthesis pathway was not directly involved. A block in the uptake of NZ was excluded as a mechanism for resistance but increased clearance of the drug was not excluded in this study.

It is expected that myo1 cells will activate a cell wall integrity signalling mechanism that is induced by abnormal cell wall assembly (Cruz et al., 2000; Kapteyn et al., 1997; Osmond et al., 1999; Popolo et al., 1997, 2001; Ram et al., 1998; Valdivieso et al., 2000). The Pkc1p-mediated cell wall integrity signalling pathway (CWIP) is principally responsible for orchestrating changes in the cell wall periodically throughout the cell cycle, as well as in response to various forms of cell wall stress (Heinisch et al., 1999; Levin, 2005; Martin et al., 2005; Vilella et al., 2005). Cell wall perturbation results in the dual phosphorylation of the Slt2p/Mpk1p MAP kinase (de Nobel et al., 2000) and Slt2p dual-phosphorylation has been previously demonstrated in myo1 cells by Western blot assay (Nishihama et al., 2003; Rivera-Molina, 2005). We observed a decrease in dual-phospho-Slt2 in myo1pUBC4 strains that suggested a restoration of cell wall integrity. Combined with the observed decrease in the requirement for Chs3p activity in these strains, we believe that this reflects new cell wall modification(s), possibly of the glucans or cell wall mannoproteins that can shut down the CWIP. The physical interaction of UBC4 with UFD4 (Ho et al., 2002), a ligase that is physically associated with microtubule subunits TUB1 and TUB2 (Gavin et al., 2006), could also be involved in modifying the secretion dynamics of cell wall proteins in our strains.

It has been previously demonstrated by others that cell wall stress can trigger an increase in cross-linking between cell wall proteins via β-1,6-glucan to chitin (Kapteyn et al., 1997) and that a defective incorporation of β-1,3-glucan can lead to an increase in chitin and mannan content in the cell wall (de Nobel et al., 2000; Kapteyn et al., 2001; Yin et al., 2005). These results highlight the importance of glucans, together with chitin and mannoproteins, in preserving cell wall integrity. To explore possible changes in the structure of the glucan layer that may be induced by overexpression of UBC4, a β-1,3-glucanase resistance/sensitivity assay was conducted. While the myo1 strains were considered sensitive by the established quantitative criteria, they were significantly less sensitive to β-1,3-glucanase than the wild-type control strain UBC4 overexpression did not modify this phenotype in the myo1 strain, yet it was capable of decreasing the level of sensitivity in a wt strain to a level resembling a myo1 strain. Therefore, over-expression of UBC4 can change specific properties of the cell wall that can make the cell wall glucan layer more resistant to β-1,3-glucanase. However, this assay did not resolve whether these changes are related to modification of the glucans themselves or to the limited accessibility of the enzyme to the glucan layer. A greater sensitivity of the myo1pUBC4 strain to zymolyase (Figure 4B) compared to β-1,3-glucanase (Figure 4A) could reflect the susceptibility of cell wall components other than glucan. Because zymolyase is a mixture of β-1,3-glucanase and other enzymes such as mannase, amylase, xylanase, phosphatase and several proteases, these results were less clear but may reflect a greater sensitivity of the outer protein layer in response to UBC4 overexpression.

The yeast 20S proteasome mediates ubiquitin-dependent degradation of short-lived proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Seufert and Jentsch, 1990). An alternative to the proteasomal peptide/protein degradation pathway in yeast involves the PVC/LE-to-vacuole trafficking pathway. A vps4 deletion mutation causes a block in the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to pre-vacuolar compartment/late endosome (PVC/LE) traffic and therefore prevents traffic between the PVC and vacuole. Vps4p is a member of the AAA (ATPase-associated activities) protein superfamily involved in endosomal maturation and exit to the vacuole (Babst et al., 1998; Lemmon and Traub, 2000). Dosage rescue of cell wall integrity in myo1 strains by UBC4 required targeting of ubiquitinated proteins to the PVC/LE–vacuole pathway while remaining insensitive to the inhibitor β-lactone, suggesting that proteasome function was not as important. Because plasma membrane proteins are generally targeted for recycling and/or degradation through the PVC/LE–vacuole pathway (Hicke, 1997; Hicke et al., 1997), this raises the possibility that remodelling of the plasma membrane may be involved in the restoration of cell wall integrity.

Concluding remarks

The notion that ubiquitins can be involved in the expression of resistance to antifungal compounds through the association of ubiquitin to receptor-like components at the cell surface of the yeast cell has been proposed to explain acquired resistance to fluconazole (Kano et al., 2001). Because ubiquitination is a major determinant of endocytosis in yeast (Hicke and Riezman, 1996; Kragt et al., 2005; Terrell et al., 1998), we suggest that the restoration of cell wall integrity by overexpression of the E2-conjugating enzyme UBC4 in myo1 cells may be explained by a modification in the normal targeting of proteins at the level of the PVC/LE compartment. Such a change may ultimately lead to the enrichment of one or more cell wall components. We propose that the implied changes in cell wall properties may involve the remodelling of glucans and/or a glycoprotein component(s) that can reinforce the cell wall structure and contribute to downregulating the CWIP in the myo1 strains. The possible enrichment of alkaline-sensitive linkage (ASL) proteins (Yin et al., 2005) in the outer protein layer is of interest in our current studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs Sahily González for technical assistance and students Glorivee Pagán, Marielis Rivera and Yasdet Maldonado de la Cruz for their support. We are grateful to Anthony Bretscher and Felix Rivera-Molina for providing a cDNA library and plasmids, respectively. Support for this work was provided by a PHS grant from NIGMS-SCORE (S06GM008224), with partial support from NCRR-RCMI (G12RR03051). NLD-B is supported by NIGMS-MARC Grant F34GM69277.

References

- Arnason T, Ellison MJ. Stress resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is strongly correlated with assembly of a novel type of multiubiquitin chain. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7876–7883. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst M, Wendland B, Estepa EJ, Emr SD. The Vps4p AAA ATPase regulates membrane association of a Vps protein complex required for normal endosome function. EMBO J. 1998;17:2982–2993. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton A, Aigle M. Genetic and functional relationship between Rvsp, myosin and actin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1998;34:280–286. doi: 10.1007/s002940050397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrejon F, Gomez A, Sanz M, Duran A, Roncero C. The RIM101 pathway contributes to yeast cell wall assembly and its function becomes essential in the absence of mitogen-activated protein kinase Slt2p. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:507–517. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.3.507-517.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SM, Madura K. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ub-conjugating enzyme Ubc4 binds the proteasome in the presence of translationally damaged proteins. Genetics. 2005;171:1477–1484. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.046888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craiu A, Gaczynska M, Akopian T, et al. Lactacystin and clasto-lactacystin beta-lactone modify multiple proteasome beta-subunits and inhibit intracellular protein degradation and major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13437–13445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JA, Garcia R, Rodriguez-Orengo JF, Rodriguez-Medina JR. Increased chitin synthesis in response to type II myosin deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2000;3:20–25. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.2000.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davierwala AP, Haynes J, Li Z, et al. The synthetic genetic interaction spectrum of essential genes. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1147–1152. doi: 10.1038/ng1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nobel H, Ruiz C, Martin H, et al. Cell wall perturbation in yeast results in dual phosphorylation of the Slt2/Mpk1 MAP kinase and in an Slt2-mediated increase in FKS2-lacZ expression, glucanase resistance and thermotolerance. Microbiology. 2000;146(9):2121–2132. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-9-2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenteany G, Schreiber SL. Lactacystin, proteasome function, and cell fate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8545–8548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firon A, Lesage G, Bussey H. Integrative studies put cell wall synthesis on the yeast functional map. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen H, Humphries C, Ho Y, et al. Characterization of the yeast amphiphysins Rvs161p and Rvs167p reveals roles for the Rvs heterodimer in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1306–1321. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin AC, Aloy P, Grandi P, et al. Proteome survey reveals modularity of the yeast cell machinery. Nature. 2006;440:631–636. doi: 10.1038/nature04532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehring AS, Mitchell DA, Tong AH, et al. Synthetic lethal analysis implicates Ste20p, a p21-activated protein kinase, in polarisome activation. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1501–1516. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinisch JJ, Lorberg A, Schmitz HP, Jacoby JJ. The protein kinase C-mediated MAP kinase pathway involved in the maintenance of cellular integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:671–680. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L. Ubiquitin-dependent internalization and downregulation of plasma membrane proteins. FASEB J. 1997;11:1215–1226. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.14.9409540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L, Riezman H. Ubiquitination of a yeast plasma membrane receptor signals its ligand-stimulated endocytosis. Cell. 1996;84:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80982-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L, Zanolari B, Pypaert M, Rohrer J, Riezman H. Transport through the yeast endocytic pathway occurs through morphologically distinct compartments and requires an active secretory pathway and Sec18p/N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:13–31. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y, Gruhler A, Heilbut A, et al. Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature. 2002;415:180–183. doi: 10.1038/415180a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Fukuda Y, Murata K, Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano R, Okabayashi K, Nakamura Y, Watanabe S, Hasegawa A. Expression of ubiquitin gene in Microsporum canis and Trichophyton mentagrophytes cultured with fluconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2559–2562. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.9.2559-2562.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapteyn JC, Ram AF, Groos EM, et al. Altered extent of cross-linking of beta1,6-glucosylated mannoproteins to chitin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants with reduced cell wall beta1,3-glucan content. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6279–6284. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6279-6284.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapteyn JC, Riet B, Vink E, et al. Low external pH induces HOG1-dependent changes in the organization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:469–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolling R, Losko S. The linker region of the ABC-transporter Ste6 mediates ubiquitination and fast turnover of the protein. EMBO J. 1997;16:2251–2261. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek WS, Bi E, Epp JA, et al. Cyk3, a novel SH3-domain protein, affects cytokinesis in yeast. Curr Biol. 2000;10:947–950. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00626-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragt A, Voorn-Brouwer T, van den Berg M, Distel B. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae peroxisomal import receptor Pex5p is monoubiquitinated in wild-type cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7867–7874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Goldberg AL. Selective inhibitors of the proteasome-dependent and vacuolar pathways of protein degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27280–27284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon SK, Traub LM. Sorting in the endosomal system in yeast and animal cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:457–466. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage G, Sdicu AM, Menard P, et al. Analysis of beta-1,3-glucan assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a synthetic interaction network and altered sensitivity to caspofungin. Genetics. 2004;167:35–49. doi: 10.1534/genetics.167.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage G, Shapiro J, Specht CA, et al. An interactional network of genes involved in chitin synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genet. 2005;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DE. Cell wall integrity signalling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:262–291. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.262-291.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie SH, Brown SS. Smy1p, a kinesin-related protein that does not require microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:873–883. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Krizek J, Bretscher A. Construction of a GAL1-regulated yeast cDNA expression library and its application to the identification of genes whose overexpression causes lethality in yeast. Genetics. 1992;132:665–673. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A, III, Demarini DJ, et al. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin H, Flandez M, Nombela C, Molina M. Protein phosphatases in MAPK signalling: we keep learning from yeast. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihama R, Ko N, Caruso C, Yu I, Pringle J. Septin dependent, actomyosin ring independent cytokinesis in yeast [abstr] Am Soc Cell Biol. 2003;43:L81. [Google Scholar]

- Osmond BC, Specht CA, Robbins PW. Chitin synthase III: synthetic lethal mutants and ‘stress related’ chitin synthesis that bypasses the CSD3/CHS6 localization pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11206–11210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popolo L, Gilardelli D, Bonfante P, Vai M. Increase in chitin as an essential response to defects in assembly of cell wall polymers in the ggp1Δ mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:463–469. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.463-469.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popolo L, Gualtieri T, Ragni E. The yeast cell-wall salvage pathway. Med Mycol. 2001;39(suppl 1):111–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram AF, Kapteyn JC, Montijn RC, et al. Loss of the plasma membrane-bound protein Gas1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in the release of beta1,3-glucan into the medium and induces a compensation mechanism to ensure cell wall integrity. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1418–1424. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1418-1424.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios Munoz W, Irizarry Ramirez M, Rivera Molina F, Gonzalez Crespo S, Rodriguez-Medina JR. Myosin II is important for maintaining regulated secretion and asymmetric localization of chitinase 1 in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;409:411–413. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00614-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Molina F. PhD Thesis. Department of Biochemistry, University of Puerto Rico; 2005. Biochemical and Genetic Analysis of Myosin II Function in the Trafficking of the Chitin Synthase III Catalytic Subunit; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Molina F, Gonzalez-Crespo S, Maldonado-De la Cruz Y, Ortiz-Betancourt J, Rodriguez-Medina J. 2,3-Butanedione monoxime increases sensitivity to nikkomycin Z in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;22:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s11274-005-9028-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez JR, Paterson BM. Yeast myosin heavy chain mutant: maintenance of the cell type specific budding pattern and the normal deposition of chitin and cell wall components requires an intact myosin heavy chain gene. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1990;17:301–308. doi: 10.1002/cm.970170405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Medina JR, Cruz JA, Robbins PW, Bi E, Pringle JR. Elevated expression of chitinase 1 and chitin synthesis in myosin II-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1998;44:919–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumanie O, Peypouquet MF, Bonneu M, et al. Evidence for the genetic interaction between the actin-binding protein Vrp1 and the RhoGAP Rgd1 mediated through Rho3p and Rho4p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:1403–1414. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos B, Snyder M. Targeting of chitin synthase 3 to polarized growth sites in yeast requires Chs5p and Myo2p. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:95–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Bowers B, Varma A, Roh DH, Cabib E. In budding yeast, contraction of the actomyosin ring and formation of the primary septum at cytokinesis depend on each other. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:293–302. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seufert W, Jentsch S. Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes UBC4 and UBC5 mediate selective degradation of short-lived and abnormal proteins. EMBO J. 1990;9:543–550. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw JA, Mol PC, Bowers B, et al. The function of chitin synthases 2 and 3 in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:111–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobering AK, Watanabe R, Romeo MJ, et al. Yeast Ras regulates the complex that catalyzes the first step in GPI-anchor biosynthesis at the ER. Cell. 2004;117:637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strous GJ, Govers R. The ubiquitin–proteasome system and endocytosis. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1417–1423. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.10.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell J, Shih S, Dunn R, Hicke L. A function for mono-ubiquitination in the internalization of a G protein-coupled receptor. Mol Cell. 1998;1:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolliday N, Pitcher M, Li R. Direct evidence for a critical role of myosin II in budding yeast cytokinesis and the evolvability of new cytokinetic mechanisms in the absence of myosin II. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:798–809. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong AH, Lesage G, Bader GD, et al. Global mapping of the yeast genetic interaction network. Science. 2004;303:808–813. doi: 10.1126/science.1091317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tongaonkar P, Chen L, Lambertson D, Ko B, Madura K. Evidence for an interaction between ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and the 26S proteasome. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4691–4698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4691-4698.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivieso MH, Ferrario L, Vai M, Duran A, Popolo L. Chitin synthesis in a gas1 mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4752–4757. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.17.4752-4757.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallen EA, Caviston J, Bi E. Roles of Hof1p, Bni1p, Bnr1p, and myo1p in cytokinesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:593–611. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilella F, Herrero E, Torres J, de la Torre-Ruiz MA. Pkc1 and the upstream elements of the cell integrity pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Rom2 and Mtl1, are required for cellular responses to oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9149–9159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Bretscher A. The rho-GAP encoded by BEM2 regulates cytoskeletal structure in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1011–1024. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.8.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheat RW. The isolation and characterization of glucosamine and muramic acid from the cell-wall mucopeptide of the Gram-negative bacterium, Chromobacterium violaceum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;121:170–172. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(66)90364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin QY, de Groot PW, Dekker HL, et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell walls: identification of proteins covalently attached via glycosylphosphatidylinositol remnants or mild alkali-sensitive linkages. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20894–20901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]