Abstract

Genetic alterations of Ikaros family zinc finger protein 1 (IKZF1), point mutations in Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), and overexpression of cytokine receptor-like factor 2 (CRLF2) were recently reported to be associated with poor outcomes in pediatric B-cell precursor (BCP)-ALL. Herein, we conducted genetic analyses of IKZF1 deletion, point mutation of JAK2 exon 16, 17, and 21, CRLF2 expression, the presence of P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion and F232C mutation in CRLF2 in 202 pediatric BCP-ALL patients newly diagnosed and registered in Japan Childhood Leukemia Study ALL02 protocol to find out if alterations in these genes are determinants of poor outcome. All patients showed good response to initial prednisolone (PSL) treatment. Ph+, infantile, and Down syndrome–associated ALL were excluded. Deletion of IKZF1 occurred in 19/202 patients (9.4%) and CRLF2 overexpression occurred in 16/107 (15.0%), which are similar to previous reports. Patients with IKZF1 deletion had reduced event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to those in patients without IKZF1 deletion (5-year EFS, 62.7% vs. 88.8%, 5-year OS, 71.8% vs. 90.2%). Our data also showed significantly inferior 5-year EFS (48.6% vs. 84.7%, log rank P = 0.0003) and 5-year OS (62.3% vs. 85.4%, log rank P = 0.009) in NCI-HR patients (n = 97). JAK2 mutations and P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion were rarely detected. IKZF1 deletion was identified as adverse prognostic factor even in pediatric BCP-ALL in NCI-HR showing good response to PSL.

Keywords: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, CRLF2, IKZF1 deletion, pediatric

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common pediatric malignancy and is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in children [1, 2]. Despite progress in therapy, approximately 20% of pediatric patients with B-cell precursor (BCP)-ALL with no adverse prognostic factors still experience relapse [3–5]. Recent genome-wide profiling studies of pediatric ALL identified a number of novel genetic alterations that target key cellular pathways for lymphoid growth and differentiation and that are associated with treatment outcome [6]. Using high-resolution single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays and genomic DNA sequencing, Mullighan et al. [7–10] and other groups revealed that alterations in genes encoding transcriptional regulators of B-lymphocyte development and differentiation, including PAX5, EBF1, and IKZF1, were observed in approximately 40% of patients with BCP-ALL. They also found that deletion of IKZF1 was very frequent in BCR-ABL–positive ALL and in the lymphoid blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia [11]. Importantly, they also revealed that IKZF1 deletion or mutation was associated with a very poor outcome, even in BCR-ABL–negative BCP-ALL [12–14]. The prognostic impact of IKZF1 deletion was also confirmed by several other groups studying pediatric BCP-ALL [15–17]. Thus, IKZF1 deletion has recently been considered as a prognostic marker for pediatric BCP-ALL and might be useful for risk stratification [16]. In addition, activating point mutations of JAK2 coexisted with IKZF1 deletion in pediatric BCP-ALL with a BCR-ABL-like gene expression signature and a very poor outcome [18]. Other studies reveal that overexpression of cytokine receptor–like factor 2 (CRLF2) due to IgH@-CRLF2 fusion resulting from immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus (IgH@) translocation or P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion resulting from the interstitial deletion of the pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1) of either of the sex chromosomes (Xp22/Yp11) was significantly associated with JAK2 mutations, IKZF1 alterations, and a poor outcome in BCP-ALL [19–25]. Furthermore, Hertzberg et al. [21] demonstrated that patients with Down syndrome–associated ALL harbored JAK2 mutations in association with altered CRLF2 overexpression, which in some patients was caused by an activating somatic mutation, F232C, in the CRLF2 gene. In this study, we sought to test whether deletion of IKZF1, dysregulation of CRLF2, JAK2 mutations, or deletions in PAX5 or EBF1 are prognostic determinants in Japanese pediatric BCP-ALL patients.

Materials and Methods

Patient cohort and samples

From April 2002 to May 2008, 1139 patients aged 1–18 years with newly diagnosed BCP-ALL (standard risk, SR = 457, high risk, HR = 543, and extremely high risk, ER = 139) (risk factors for classification are described in Table S#1) were enrolled in the JACLS ALL study and assigned to three risk-stratified ALL02 protocols [26, 27]. The diagnosis of BCP-ALL was based on morphological findings on bone marrow aspirates and immunophenotype analyses of leukemic cells by flow cytometry. Conventional cytogenetic analyses using G-banding method were done as part of the routine workup. Molecular studies using quantitative RT-PCR for the detection of BCR-ABL, ETV6-RUNX1, MLL-AF4, MLL-ENL, MLL-AF9, and TCF3(E2A)-PBX1 were performed as part of the routine workup. None of the cases of BCR-ABL-positive ALL and infant ALL was included. Down syndrome–associated ALL was excluded from the genetic analysis. Thus, 542 patients were included in this study. As the study was multi-institutional and the registry of patients was drawn from 93 hospitals, appropriate DNA/RNA specimens at diagnosis could be obtained from only 202 of the 542 patients in this group. A comparison of the clinical characteristics of patients with and without DNA/RNA specimens is shown in Table 1. There was no difference between these two cohorts in age at diagnosis, gender, NCI risk [28], and other variables except for initial WBC count. Informed consent was obtained from the patients' guardians according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocols of treatment, and the genetic study were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating institutes.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics in 543 high-risk BCP-ALL patients depending on whether they were included in the genetic analyses

| Number of patients | 202 | 340 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analyzed | Nonanalyzed | ||

| Gender (male/female) | 106/96 | 186/154 | 0.66 |

| Age (yrs) at diagnosis, median (range) | 5 (1–18) | 6 (1–17) | 0.24 |

| WBC count (cells/μL), median (range) | 21,350 (1300–400,800) | 12,635 (430–26,500) | <0.01 |

| NCI risk group, SR/HR | 108/94 | 189/151 | 0.63 |

| ETV6-RUNX1/hyperdiploid | 0.85 | ||

| Yes | 69 | 113 | |

| No | 133 | 227 | |

| SCT in 1st CR (n) | 0 | 9 | 0.03 |

| Observation period, median (range) | 5.4 (0.5–8.9) | 5.1 (0.1–9.0) | 0.47 |

WBC, white blood cell; NCI, National Cancer Institute; SR, standard risk; HR, high risk; SCT, stem cell transplantation; CR, complete remission.

Determination of abnormalities in IKZF1 and other genes by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

Genomic DNA was isolated from diagnostic bone marrow or peripheral blood samples using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Venio, the Netherlands). DNA was analyzed using the SALSA multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) kit P335-A4 according to the manufacturer's instructions (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). This kit includes probes for IKZF1, CDKN2A, CDKN2B, PAX5, ETV6, RB1, BTG1, EBF1, and the PAR1 region, which includes CRLF2, CSF2RA, and IL3RA. PCR fragments generated with the MLPA kit were separated by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI Prism 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Peak area was measured using GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems). The relative copy number, obtained after normalization against controls, was used to determine genomic copy number of each gene as follows: 0 (<0.6, i.e., biallelic loss), 1 (0.6–1.47, i.e., monoallelic loss), 2 (1.47–2.6, i.e., normal copy number), or 3 or more (>2.6, i.e., gain) [29].

Detection of CRLF2 overexpression by real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from diagnostic bone marrow or peripheral blood samples using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Real-time RT-PCR was conducted using the 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR Green II (Takara Bio, Tokyo, Japan). Relative expression of target mRNA was determined using the comparative threshold (ΔCT) method, in which the CT value of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) internal control mRNA is subtracted from that of the target mRNA. Data are expressed as the ratio of target mRNA to GAPDH mRNA (calculated as 2ΔCT). The primer pairs used in this study are listed in Table S2. Overexpression of CRLF2 was defined as expression tenfold or greater than the median expression value based on a previous report [23]. A total of 107 specimens were available for the CRLF2 study.

Detection of P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion by RT-PCR

The P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion was detected by RT-PCR or MLPA kit P335-A4 in 202 patients. The primers used are listed in Table S2.

CRLF2 mutation analysis

Using cDNA samples with altered CRLF2 expression, the presence of the CRLF2 F232C point mutation was detected by direct sequencing. The primers used are listed in Table S2. Appropriate RNA samples were available from all the 16 patients who overexpressed CRLF2.

JAK2 mutations analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from diagnostic bone marrow or peripheral blood samples of patients harboring an IKZF1 deletion. Primers were used to amplify exons 16, 20, and 21 of JAK2 (accession number NM 004972). The PCR product was analyzed by direct sequencing using a BigDye Terminator sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). The primers used are listed in Table S2. Appropriate DNA samples from all patients with the IKZF1 deletion were available for the JAK2 mutations study.

Statistical analysis

Estimation of event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method and the differences were compared using the log rank test. A P-value <0.05 (two sided) was considered significant. EFS and OS were defined as the times from diagnosis to event (any death, relapse, secondary malignancy, or failure of therapy) and from diagnosis to death from any cause or to the last follow-up. Patients without an event of interest were censored at the date of last contact. The median follow-up times for EFS and OS were 5.22 and 5.34 years, respectively. Hazard ratios for probability of relapse between subgroups were calculated using univariate Cox models. Multivariate analysis was performed using a Cox regression model, which was adjusted for other risk factors: age at diagnosis and initial WBC count. Other comparisons were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate.

Results

Frequency of IKZF1 deletion, CRLF2 overexpression, and JAK2 mutations in patients in the JACLS ALL02 HR cohort

Deletion of the IKZF1 gene was identified in 19/202 patients (9.4%) and CRLF2 overexpression was noted in 16/107 patients (15.0%). The P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion and CRLF2 F232C mutation were very rare (1/202 and 0/16 patients, respectively). A recent study demonstrated that gain of CRLF2 copy number was observed in BCP-ALL with overexpression of CRLF2 [24]. In consistent with this report, 8 (50.0%) of 16 patients with altered CRLF2 expression harbored gain of CRLF2 copy number in our cohort (8/16 vs. 2/91, P < 0.01). In addition, no JAK2 mutations (exons 16, 20, 21) were detected.

Association of clinical and genetic features with IKZF1 deletion and CRLF2 overexpression

The comparison of patient characteristics depending on IKZF1 deletion and CRLF2 overexpression is summarized in Table 2. Gender, initial WBC count, and NCI risk did not differ between patients with these genetic variations. IKZF1 deletion was more frequently observed in older patients (1–9 years vs. 10–18 years, P = 0.008). In terms of concurrent chromosomal/genetic abnormalities, IKZF1 deletion was observed in 1/68 of ETV6-RUNX1–positive + hyperdiploid/trisomy 4, 10, and 17 (triple trisomy [30]) patients compared to 18/134 of patients without those abnormalities (P = 0.0059). These findings suggest that IKZF1 deletion and chromosomal abnormalities with good prognosis are mutually exclusive. Similarly, the status of CRLF2 overexpression did not significantly correlate with gender, age at diagnosis, initial WBC count, or NCI risk. However, CRLF2 overexpression was significantly associated with chromosomal abnormalities with an incidence of normal karyotype + hyperdiploid/triple trisomy of 12/36 compared to 4/71 for other karyotypes (P = 0.014). However, in our cohort, only one P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion and no CRLF2 F232C mutations were detected. In addition, this P2RY8-CRLF2–positive case did not have IKZF1 deletion. JAK2 mutations in exons 16, 20, or 21 were not detected in the 19 patients with IKZF1 deletion. These findings suggest that genetic events in association with IKZF1 deletion in our cohort might be different from those previously reported [21, 24, 25].

Table 2.

Association of clinical and genetic features with IKZF1 deletion and CRLF2 overexpression

| IKZF1 deletion | CRLF2 OE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P-value | Yes | No | P-value | |

| Total | 19 | 183 | 16 | 91 | ||

| Gender | 0.51 | 0.38 | ||||

| Male | 8 | 98 | 11 | 47 | ||

| Female | 11 | 85 | 5 | 44 | ||

| Age (yrs) at diagnosis | ||||||

| Median | 10 | 5 | 0.08 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 0.41 |

| 1–9 | 9 | 143 | 0.009 | 14 | 63 | 0.16 |

| 10–18 | 10 | 40 | 2 | 28 | ||

| WBC count (×103cells/μL) | ||||||

| Median | 23,430 | 20,810 | 0.68 | 22,000 | 24,240 | 0.87 |

| <100 | 17 | 165 | 0.92 | 14 | 78 | 0.31 |

| ≥100 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 13 | ||

| NCI risk group | 0.15 | 0.14 | ||||

| SR | 7 | 101 | 10 | 41 | ||

| HR | 12 | 82 | 6 | 50 | ||

| Karyotype | 0.003 | 0.014 | ||||

| No fusion genes | 16 | 101 | 16 | 50 | ||

| (normal karyotype) | (7) | (32) | (5) | (18) | ||

| (hyperdiploid/ triple trisomy)* | (0) | (28) | (7) | (6) | ||

| (others)** | (8) | (39) | (1) | (25) | ||

| (undetermined) | (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | ||

| Fusion genes | 3 | 82 | 0 | 41 | ||

| (ETV6-RUNX1) | (1) | (40) | (0) | (20) | ||

| (TCF3(E2A)-PBX1) | (2) | (37) | (0) | (18) | ||

| (11q23) | (0) | (5) | (0) | (3) | ||

Triple trisomy indicates trisomy 4, 10, and 17.

Karyotype other than normal karyotype, hyperdiploid, triple trisomy, and 11q23 abnormality, showing a negative result in screening for chimeric fusions, as described in the Materials and Methods.

OE, overexpression; NCI, National Cancer Institute; SR, standard risk; HR, high risk.

IKZF1 deletion, not CRLF2 overexpression, was strongly associated with a poor outcome

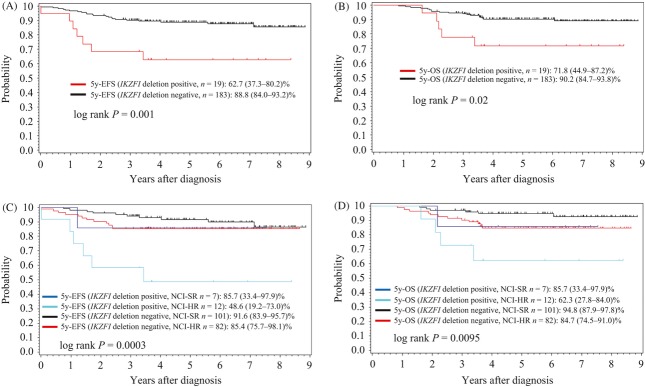

As seen in Figure 1, the 5-year EFS and OS for the patients with IKZF1 deletion were inferior to those without IKZF1 deletion. To compare our data internationally, we assigned patients in our cohort into NCI high risk (NCI-HR) and NCI standard risk (NCI-SR). In NCI-HR group (n = 94), the 5-year EFS and OS for patients with IKZF1 deletion (n = 12) was inferior to those without IKZF1 deletion. However, in NCI-SR patients (n = 108), the 5-year EFS and OS for the patients with IKZF1 deletion (n = 7) was comparable to those without IKZF1 deletion (Fig. 1). As summarized in Table 3, univariate analysis revealed that IKZF1 deletion was associated with a significantly inferior EFS (P < 0.01). IKZF1 deletion was also associated with a significantly inferior EFS by multivariate analysis (P = 0.03, Table 4). However, NCI risk alone did not affect the EFS by univariate (P = 0.06) in our cohort. These findings suggest that IKZF1 deletion is an independent prognostic factor in pediatric patients with BCP-ALL in JACLS-HR and NCI-HR groups in this cohort.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) in BCP-ALL patients enrolled in the JACLS ALL02 HR cohort (n = 202). (A) EFS and (B) OS for patients with or without IKZF1 deletion in this cohort. (C) EFS and (D) OS for patients with or without IKZF1 deletion according to NCI risk group.

Table 3.

Univariate cox model of event-free and overall survival of analyzed patients

| Variable | Hazard ratio | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Event-free survival | |||

| Age (yrs) at diagnosis (1–9 vs. 10–18) | 2.923 | <0.01 | 1.404–6.089 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 1.279 | 0.51 | 0.611–2.679 |

| WBC count (×1000 cells/μL)(≥100 vs. <100) | 2.682 | 0.03 | 1.090–6.600 |

| NCI risk (HR vs. SR) | 2.067 | 0.06 | 0.975–4.381 |

| IKZF1 deletion (Yes vs. No) | 3.701 | <0.01 | 1.579–8.675 |

| Overall survival | |||

| Age (yrs) at diagnosis (1–9 vs. 10–18) | 3.188 | <0.01 | 1.406–6.089 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.819 | 0.63 | 0.361–1.857 |

| WBC count (×1000 cells/μL)(≥100 vs. <100) | 2.678 | 0.05 | 0.994–7.216 |

| NCI risk (HR vs. SR) | 2.787 | 0.02 | 1.146–6.776 |

| IKZF1 deletion (Yes vs. No) | 3.069 | 0.03 | 1.139–8.269 |

NCI, National Cancer Institute; SR, standard risk; HR, high risk.

Table 4.

Multivariate cox model of event-free and overall survival of analyzed patients

| Variable | Hazard ratio | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Event-free survival | |||

| Age (yrs) at diagnosis (1–9 vs. 10–18) | 2.586 | 0.02 | 1.192–5.610 |

| WBC count (×1000 cells/μL)(≥100 vs. <100) | 2.882 | 0.02 | 1.163–7.138 |

| IKZF1 deletion (Yes vs. No) | 2.668 | 0.03 | 1.086–6.553 |

| Overall survival | |||

| Age (yrs) at diagnosis (1–9 vs. 10–18) | 3.016 | 0.01 | 1.281–7.102 |

| WBC count (×1000 cells/μL)(≥100 vs. <100) | 2.866 | 0.04 | 1.049–7.829 |

| IKZF1 deletion (Yes vs. No) | 2.049 | 0.18 | 0.723–5.807 |

On the contrary, 5-year EFS achieved in the patients with CRLF2 overexpression was 100%, suggesting CRLF2 overexpression was not adverse prognostic factor in our current cohort.

Other microdeletions were not associated with a poor outcome

In our cohort, the frequencies of deletions of other genes tested were 81/202 (40%) for CDKN2A, 69/202 (34%) for CDKN2B, 59/202 (29%) for PAX5, 47/202 (23%) for ETV6, 12/202 (5.9%) for RB1, 15/202 (7.4%) for BTG1, and 22/202 (11%) for EBF1. None of these genetic alterations were associated with altered probability of relapse regardless of the presence/absence of IKZF1 deletion (Table S3).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of IKZF1, CRLF2, and JAK2 alterations in pediatric BCP-ALL in Japan. The frequency of IKZF1 deletion in JACLS ALL02 HR patients was 19/202 (9.4%), which is consistent with previous reports [7, 11, 17]. In this study, univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that the IKZF1 deletion was an independent factor for inferior EFS in pediatric BCP-ALL patients. More specifically, IKZF1 deletion was strongly associated with a poor outcome in the NCI-HR patient group. As NCI-HR is defined by age and initial WBC alone, it consisted of patients who showed a good response to initial prednisolone administration, which corresponds to JACLS-HR, and those who did not, which corresponds to JACLS-ER. Nevertheless, the fact that IKZF1 deletion affects outcomes in the NCI-HR group in our cohort indicates that this mutation is an independent prognostic factor irrespective of the initial prednisolone response. Thus, we believe that early risk stratification in pediatric BCP-ALL patients should be based on a new risk stratification system including IKZF1 status [16].

In terms of prognostic value of CRLF2 alteration, our study demonstrated that CRLF2 overexpression was not necessarily associated with a poor prognosis as well as did the previous study [25]. The contradictory results reported by Cario et al. [24], in which CRLF2 overexpression was associated with poor EFS in the ALL-BFM 2000 protocol (6-year EFS 28% vs. 71%, P = 0.001), were thought to be mainly due to the effect of the P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion, and not simply CRLF2 overexpression. The frequency of CRLF2 overexpression was 16/107 (15.0%) in this cohort, which is comparable to previous reports. However, we could not confirm that the activating mutation of JAK2 and CRLF2 overexpression caused by P2RY8-CRLF2 rearrangement was associated with IKZF1 alteration. These findings might explain that CRLF2 overexpression was not associated with a poor prognosis in the current cohort.

In previous reports, excluding patients with Down syndrome, the incidences of point mutations of JAK2 exons 16, 20, and 21 causing gain of function have been associated with IKZF1 deletion and P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion: 87.5% of patients with JAK2 mutations had IKZF1 alterations (P = 0.001) [18] and 30–100% of patients with JAK2 mutations had P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion [21–25]. On the other hand, we detected only one patient with P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion of 202, and this patient did not have point mutations of JAK2 exon 16, 20, or 21 in this analysis. Although the reason for the discrepancy between our data and that of others is not clear, there might be several ones to be in consideration. First, the frequency of genetic alterations might depend on the ethnicity. It is interesting that genetic alterations of JAK and CRLF2 are relatively frequent in Hispanic patients [23]. Although there is no report of the analysis of JAK2 and P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion in pediatric BCP-ALL from other Asian countries, it might be possible that the frequency of JAK2 and P2RY8-CRLF2 fusions are relatively low among Asian patients. Second, our genetic analysis carried out in this study was not comprehensive. For example, we were not able to analyze the IgH@-CRLF2 fusion due to lack of the materials for FISH analysis and the type of CRLF2 genomic aberrations might be varied in studied cohorts [23–25, 31, 32]. We did not analyze JAK1 or JAK3 which may also play roles in leukemogenesis, although the frequency of the alterations in these genes is thought to be considerably lower than those in JAK2 [18]. Third, it is also possible that JACLS ALL02 HR cohort might not include BCP-ALL cases with BCR-ABL like gene expression signature, in which JAK2 activating mutation and CRLF2 genomic aberration are concurrently present with IKZF1 deletion. Thus, we are planning to carry out the genetic analysis of the BCP-ALL cases treated according to JACLS ALL02 ER group which might include more BCP-ALL cases with BCR-ABL like gene expression signature.

In conclusion, IKZF1 deletion should be a valuable prognostic marker to include in future algorithms for early risk stratification in the treatment of pediatric BCP-ALL. Further studies are required to clarify the genetic alterations instead of P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion and/or JAK2 mutations, which may cooperate with IKZF1 deletion in these leukemic patients in Japan.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study and their guardians. The authors also thank staff in the OSCR data center for data management and the physicians who registered patients in JACLS ALL02 clinical trial. This work was supported by grants for Clinical Cancer Research and Research on Measures for Intractable Diseases from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Conflict of Interest

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. Risk stratification in JACLS ALL02 trial.

Table S2. Primer list used in this study.

Table S3. Impact of other genetic alterations on outcome depending on IKZF1 deletion.

References

- 1.Pui CH, Relling MV, Downing JR. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:1535–1548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371:1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, Bowman WP, Sandlund JT, Kaste SC, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2730–2741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pui CH, Pei D, Sandlund JT, Ribeiro RC, Rubnitz JE, Raimondi SC, et al. Long-term results of St Jude total therapy studies 11, 12,13A, 13B, and 14 for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:371–382. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, Camitta BM, Gaynon PS, Winick NJ, et al. Improved survival for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) from 1990–2005: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. 40th Congress of the International Society of Pediaric Oncology, Berlin, Germany. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2008;22:2142–2150. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins-Underwood JR, Mullighan CG. Genomic profiling of high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1676–1685. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, Miller CB, Coustan-Smith E, Dalton JD, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamata N, Ogawa S, Zimmermann M, Kato M, Sanada M, Hemminki K, et al. Molecular allelokaryotyping of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemias by high-resolution single nucleotidepolymorphism oligonucleotide genomic microarray. Blood. 2008;111:776–784. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuiper RP, Schoenmakers EF, Hehir-Kwa SV, van Reijmersdal JY, van Kessel AG, van Leeuwen FN, Hoogerbrugge PM, et al. High-resolution genomic profiling of childhood ALL reveals novel recurrent genetic lesions affecting pathways involved in lymphocyte differentiation and cell cycle progression. Leukemia. 2007;21:1258–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paulsson K, Cazier JB, Macdougall F, Stevens J, Stasevich I, Vrcelj N, et al. Microdeletions are a general feature of adult and adolescent acute lymphoblastic leukemia: unexpected similarities with pediatric disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6708–6713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800408105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullighan CG, Miller CB, Radtke I, Phillips LA, Dalton J, Ma J, et al. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of Ikaros. Nature. 2008;453:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature06866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullighan CG, Su X, Zhang J, Radtke I, Phillips LA, Miller CB, et al. Children's Oncology Group. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:470–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuiper RP, Waanders E, van Reijmersdal VH, van der Velden SV, Venkatachalam R, Scheijen B, et al. IKZF1 deletions predict relapse in uniformly treated pediatric precursor B-ALL. Leukemia. 2010;24:1258–1264. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Den Boer ML, Cheok M, van Slegtenhorst RX, De Menezes MH, Buijs-Gladdines JG, Peters ST, et al. A subtype of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with poor treatment outcome: a genomewide classification study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:125–134. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70339-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinelli G, Iacobucci I, Storlazzi CT, Vignetti M, Paoloni F, Cilloni D, et al. IKZF1 (Ikaros) deletions in BCR-ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia are associated with short disease-free survival and high rate of cumulative incidence of relapse: a GIMEMA AL WP Report. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;27:5202–5207. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waanders E, van Leeuwen VH, van der Velden CE, van der Schoot FN, van Reijmersdal SV, de Hass V, et al. Integrated use of minimal residual disease classification and IKZF1 alteration status accurately predicts 79% of relapses in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:254–258. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang YL, Hung CC, Chen JS, Lin KH, Jou ST, Hsiao CC, et al. IKZF1 deletions predict a poor prognosis in children with B-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a multicenter analysis in Taiwan. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1874–1881. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullighan CG, Zhang J, Harvey RC, Collins-Underwood JR, Schulman BA, Phillips LA, et al. JAK mutations in high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:9414–9418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811761106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell LJ, Capasso M, Vater I, Akasaka T, Bemard OA, Calasanz MJ, et al. Deregulated expression of cytokine receptor gene, CRLF2, is involved in lymphoid transformation in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:2688–2698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullighan CG, Collins-Underwood JR, Phillips LA, Loudin MG, Liu W, Zhang J, et al. Rearrangement of CRLF2 in B-progenitorand Down syndrome-associated acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1243–1246. doi: 10.1038/ng.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hertzberg L, Vendramini E, Ganmore I, Cazzaniga G, Schmitz M, Chalker J, et al. Down syndrome acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a highly heterogeneous disease in which aberrant expression of CRLF2 is associated with mutated JAK2: a report from the iBFM Study Group. Blood. 2010;115:1006–1017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-235408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoda A, Yoda Y, Chiaretti S, Bar-Natan M, Mani K, Rodig SJ, et al. Functional screening identifies CRLF2 in precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:252–257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911726107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Chen IM, Wharton W, Mikhail FM, Carroll AJ, et al. Rearrangement of CRLF2 is associated with mutation of JAK kinases, alteration of IKZF1, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity and a poor outcome in pediatric B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:5312–5321. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-245944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cario G, Zimmermann M, Romey R, Gesk S, Vater I, Harbott J, et al. Presence of the P2RY8-CRLF2 rearrangement is associated with a poor prognosis in non-high-risk precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children treated according to the ALLBFM 2000 protocol. Blood. 2010;115:5393–5297. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-256131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ensor HM, Schwab C, Russell LJ, Richards SM, Morrison H, Masic D, et al. Demographic, clinical and outcome features of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and CRLF2 deregulation: results from the MRC ALL97 clinical trial. Blood. 2011;117:2129–2136. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-297135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki N, Yumura-Yagi K, Yoshida M, Hara J, Nishimura S, Kudoh T, et al. Japan Association of Childhood Leukemia Study (JACLS). Outcome of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia with induction failure treated by the Japan association of childhood leukemia study (JACLS) ALL F-protocol. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2010;54:71–78. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasegawa D, Hara J, Suenobu S, Takahashi Y, Sato A, Suzuki N, et al. Successful abolition of prophylactic cranial irradiation in children with non-T acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in the Japan Association of Childhood Leukemia Study (JACLS) ALL-02 trial. Blood. 2011;118:653. (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith M, Arthur D, Camitta B, Carroll AJ, Crist W, Gaynon P, et al. Uniform approach to risk classification and treatment assignment for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996;14:18–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwab CJ, Jones LR, Morrison H, Ryan SL, Yigittop H, Schouten JP, et al. Evaluation of multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification as a method for the detection of copy number abnormalities in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 2010;49:1104–1113. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutcliffe MJ, Schuster JJ. Sather HNet al. High concordance from independent studies by the Children's Cancer Group (CCG) and Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) associating favorable prognosis with combined trisomies 4, 10, and 17 in children with NCI Standard-Risk B-precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: a Children's Oncology Group (COG) initiative. Leukemia. 2005;19:734–740. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Wang X, Dobbin KK, Davidson GS, Bedrick EJ, et al. Identification of novel cluster groups in pediatric high-risk B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with gene expression profiling: correlation with genome-wide DNA copy numberalterations, clinical characteristics, and outcome. Blood. 2010;116:4874–4884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen IM, Harvey RC, Mulligham CG, Gastier-Foster J, Wharton W, Kang H. Outcome modeling with CRLF2 IKZF1 JAK, and minimal residual disease in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children's Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2012;119:3512–3522. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-394221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.