Summary

Septins are conserved, cytoskeletal GTPases that contribute to cytokinesis, exocytosis, cell surface organization, and vesicle fusion by mechanisms that are poorly understood. Roles of septins in morphogenesis and virulence of a human pathogen and basidiomycetous yeast Cryptococcus neoformans were investigated. In contrast to a well established paradigm in S. cerevisiae, Cdc3, and Cdc12 septin homologs are dispensable for growth in C. neoformans yeast cells at 24°C but are essential at 37°C. In a bilateral cross between septin mutants, cells fuse but the resulting hyphae exhibit morphological abnormalities including lack of properly fused specialized clamp cells and failure to produce spores. Interestingly, post-mating hyphae of the septin mutants have a defect in nuclear distribution. Thus, septins are essential for the development of spores, clamp cell fusion and also play a specific role in nuclear dynamics in hyphae. In the post-mating hyphae the septins localize to discrete sites in clamp connections, to the septa, and the bases of the initial emerging spores. Strains lacking CDC3 or CDC12 exhibit significantly reduced virulence in a Galleria mellonella model of infection. Thus, C. neoformans septins are vital to morphology of the hyphae and contribute to virulence.

Keywords: septins, morphogenesis, Cryptococcus

Introduction

Septins are conserved cytoskeletal GTPases that were initially described in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as essential elements during cytokinesis (Hartwell, 1971; Weirich et al., 2008). Septins typically assemble into heterooligomeric complexes that proceed to form higher order filamentous structures, including bundles, gauzes, and rings (Barral and Kinoshita, 2008). Septin complexes often associate with membranes and other cytoskeletal elements, namely actin and microtubules (Kinoshita et al., 2002; Silverman-Gavrila and Silverman-Gavrila, 2008). In S. cerevisiae, the septins Cdc3, Cdc10, Cdc11, Cdc12, and Shs1 form a ring at the presumptive bud site (Gladfelter et al., 2001). During bud emergence, they arrange at the mother-bud neck as an hourglass collar, which splits into two rings during cytokinesis. In S. cerevisiae, septins have been implicated in bud site selection, polarized growth, cell wall synthesis, cytokinesis, and the morphogenesis and spindle position checkpoints (reviewed in (Douglas et al., 2005)).

Although the precise mechanisms by which septins exert their functions remain unknown, two major modes of action include serving as a scaffold and compartmentalizing cell membranes. The scaffolding role has been clearly documented only in budding yeast where septins form a platform for proteins involved in cell cycle regulation, and chitin synthesis (Gladfelter et al., 2001; Weirich et al., 2008). A septin diffusion barrier divides the cortex and the ER of mother and daughter yeast cells into two separate membrane compartments, while during cytokinesis septins compartmentalize the cortex at the site of cleavage (Caudron and Barral, 2009). Septins are important for maintenance of cell morphology although the exact mechanism is unclear. In yeast cells, misorganized septin complexes at the mother-bud neck cause aberrant bud morphology, presumably because septins mediate targeting of secretory vesicles to the base of the bud (Gladfelter et al., 2005).

In mammalian neuronal cells, septins localize at the bases of filopodia and at branch points in developing hippocampal neurons, thereby regulating dendritic branching and dendritic-spine morphology (Xie et al., 2007). Septins have been associated with a number of important diseases including various cancers and neurodegenerative disorders (Hall and Russell, 2004; Ihara et al., 2003; Ihara et al., 2007; Russell and Hall, 2005) but the precise molecular events governing septin contributions to various disease states remain largely unexplored.

Filamentous fungi have emerged as useful model systems to study the biology of septins due to their morphological complexity, genetic tractability, and the existence of well-established cell biology tools (Gladfelter, 2006). Importantly, septins were shown to be necessary for virulence of pathogenic fungi (Boyce et al., 2005; Douglas et al., 2005; Gonzalez-Novo et al., 2006). In most fungal cells, septins localize either at the tips or bases of growing projections or as partitions between cells or membrane compartments (Lindsey and Momany, 2006). In fungal hyphae, the septins assemble into a variety of complexes that differ in topology and presumably fulfill specialized functions (Gladfelter, 2006). Among hyphae-forming fungi, septins have been described in Aspergillus nidulans, Candida albicans, Ashbya gossypii, Ustilago maydis, and Blastomyces dermatitidis (Boyce et al., 2005; Canovas and Perez-Martin, 2009; Demay et al., 2009; Douglas et al., 2005; Krajaejun et al., 2007; Momany et al., 2001). Since each of these organisms possesses unique morphological features, they provide invaluable opportunities to elucidate detailed aspects of septin biology. In this study, we describe novel functional roles for septins in Cryptococcus neoformans.

C. neoformans is an opportunistic human pathogen that causes fatal meningitis in immunocompromized and sometimes immunocompetent individuals (Casadevall, 1998). It is a basidiomycetous yeast ubiquitously present in the environment, frequently found in tree hollows and pigeon guano. During mating two yeast cells of opposite mating type fuse and subsequently undergo a dimorphic morphogenetic transition into heterokaryotic hyphae equipped with specialized clamp cells that mediate nuclear distribution. The hyphae subsequently develop basidial cells decorated with four chains of meiotic spores. Spores and small yeast cells are infectious particles that are inhaled and colonize the lungs of the host (Casadevall, 1998). We present evidence that septins are essential for the proper development of the dikaryotic post-mating hyphae and hyphae resulting from monokaryotic fruiting. We show that septins are needed for the formation of spore chains, fusion of clamp cells, and proper nuclear distribution within hyphae. In addition, septins were found to contribute directly to virulence of cryptococcal yeast cells.

Results

Septins Cdc3, Cdc11, and Cdc12 are essential for growth at 37°C

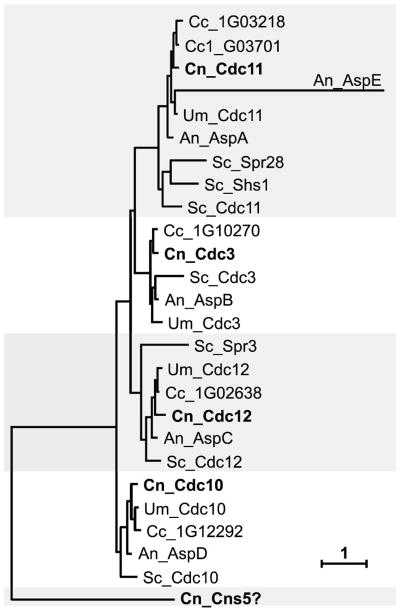

To identify genes essential for growth at 37°C, a collection of 1201 deletion mutants (Liu et al., 2008) was screened for growth on YPD solid medium at 37°C. Among strains that were unable to grow at elevated temperature, three mutants containing deletions of genes encoding homologues of septin proteins were identified (CNAG_05925, CNAG_02196, CNAG_017401). The deletion collection also contained two mutant strains deleted for other septin homologues that grew at 37°C (CNAG_01373, CNAG_04007). Analysis of the C. neoformans serotype A genome (Broad Institute, Cambridge MA) revealed five genes, four of which are close homologues of the septins first identified in S. cerevisiae: CDC3, CDC10, CDC11, and CDC12 (Pan et al., 2007) (Figure 1 and Table 2). Comparison of the fifth gene product to S. cerevisiae septins using ClustalW showed equally weak homology to all septins (10–14% identity). This protein was named Cns5, for Cryptococcus neoformans septin-like protein 5, based on homology to other eukaryotic septins. However, as discussed below, the determination as to whether this is indeed a bona fide septin remains an open question. Figure 1 shows a phylogenetic comparison of the C. neoformans septins with septin proteins from other representative fungi. Not surprisingly, cryptococcal septins show the highest level of homology to septins from two other basidiomycetes, Ustilago maydis and Coprinopsis cinerea.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing septin proteins from C. neoformans and other fungi: Cn – Cryptococcus neoformans (bold), Cc – Coprinopsis cinerea, Um – Ustilago maydis, Sc – Saccharomyces cerevisiae, An – Aspergillus nidulans. Shaded areas divide proteins into four distinct groups represented by Cdc3, Cdc10, Cdc11, and Cdc12 in S. cerevisiae. Currently, there is no strong evidence that Cns5 is a septin. The scale bar indicates a branch length corresponding to 1 amino-acid substitution/site.

Table 2.

Septin homology between Cryptococcus neoformans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae

| C. neoformans septin | % identity with S. cerevisiae septin | % of residues with strong similarity to S. cerevisiae septin |

|---|---|---|

| Cdc3 | 42.31 | 22.12 |

| Cdc10 | 55.96 | 19.57 |

| Cdc11 | 42.11 | 17.85 |

| Cdc12 | 48.91 | 19.85 |

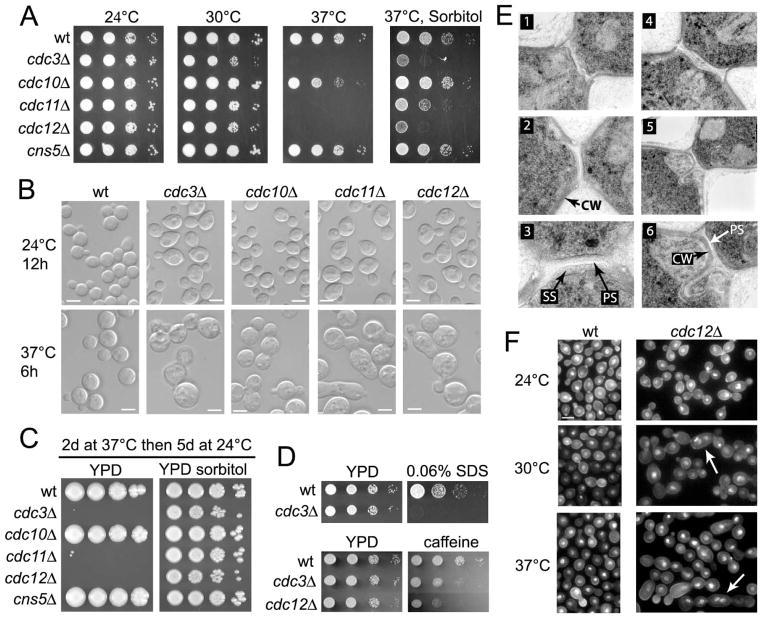

None of the septin deletion mutants showed a growth defect at 24°C based on a growth dilution spot assay (Figure 2A). At 30°C, cdc3Δ, cdc11Δ, and cdc12Δ mutants exhibited a modest growth defect. At 37°C, cdc3Δ, cdc11Δ, and cdc12Δ mutants were inviable, while cdc10Δ exhibited a partial growth defect, and cns5Δ had a wild type growth rate (Figure 2A). Microscopic examination revealed that at 24°C a subpopulation of cdc3Δ, cdc11Δ, and cdc12Δ cells were highly aberrant (~1% of cells), whereas the remaining majority of cells exhibited a wild type morphology except for two apparent differences. First, all of the cells were modestly enlarged compared to wild type, as confirmed by FACS analysis (Figure 2B and data not shown). Second, cdc3Δ, cdc11Δ, and cdc12Δ mutant cells were slightly elongated, whereas the wild type cells were ovoid (Figure 2B). All of the cells of the cdc10Δ and cns5Δ mutants had wild type morphology at 24°C (Figure 2B and data not shown). At the non-permissive temperature all of the cells of the cdc3Δ, cdc11Δ, and cdc12Δ mutants showed highly aberrant morphology, while cdc10Δ cells had a partial morphology defect, and cns5Δ cells were wild type (Figure 2B and data not shown). Addition of 1 M sorbitol to solid YPD media allowed partial growth of the cdc3Δ, cdc11Δ, and cdc12Δ mutants at 37°C (Figure 2A). When YPD plates and 1 M sorbitol YPD plates were incubated at 37°C for two days and then shifted to room temperature and examined over 5 days, cdc3Δ, cdc11Δ, and cdc12Δ did not grow on YPD, whereas all three strains grew on the medium supplemented with sorbitol (Figure 2C). Thus, cell death occurs at 37°C and this may be at least in part due to cell wall damage that can be mitigated in part by osmotic support.

Figure 2.

Septin mutants are not viable at 37°C, possess a defect in septation, and exhibit sensitivity to cell wall damaging agents. (A) Serial dilutions of septin deletion strains (Liu et al., 2008) were spotted on YPD and on YPD with 1 M sorbitol and grown for 2 days at the indicated temperatures. B. Strains from A were grown in YPD liquid medium at either 24°C or 37°C and the morphology was evaluated using DIC microscopy. (C) Strains from A were grown on either an YPD medium or on YPD medium supplemented with 1 M sorbitol at 37°C for two days. Next, the plates were shifted to room temperature and examined over 5 days. (D) Septin deletion strains generated in this study were examined for growth on medium supplemented with 0.06% SDS (cdc3Δ) and on medium supplemented with 0.5 mg/ml caffeine (cdc3Δ and cdc12Δ). Cells were grown at either room temperature or 30°C (SDS medium only). (E) The wild type cells (KN99a, panels 1, 2, 3) and the cdc3Δ cdc12Δ double mutant (panels 4, 5, 6) were examined with TEM. CW, cell wall; PS, primary septum; SS, secondary septum. Panels 3 and 6 are the enlargements of panels 2 and 5, respectively. (F) Nuclei (DAPI) and the chitin (calcofluor white) were examined in the wild type strain (KN99a) and in the cdc12Δ mutant at three temperatures as indicated. Arrows indicate cells with multiple nuclei. See text for details. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

Relatively larger size of cdc3Δ, cdc11Δ, and cdc12Δ septin mutants suggested that these cells might be diploids. FACS analysis revealed diploid-like profiles for all three septin mutants, whereas cdc10Δ cells were haploid (Figure S1). For further studies, cdc3Δ and cdc12Δ septin deletion mutants were generated in the H99α and KN99a congenic strains. Both mutants exhibited similar growth defects, a highly aberrant morphology at 37°C, and a relatively mild growth phenotype at 24°C. FACS analysis of both cdc3Δ and cdc12Δ mutants revealed profiles consistent with a mixed population of haploid and diploid cells (Figure S1). This suggests that a lack of septins may lead to changes in ploidy. Consistent with previous observations, both cdc3Δ and cdc12Δ septin mutants were hypersensitive to the cell wall damaging agents SDS and caffeine (Figure 2D and data not shown). However, cdc3Δ and cdc12Δ septin mutants did not show hypersensitivity to the cell wall disrupting drug caspofungin (data not shown) and the analysis of chitin with the calcofluor white did not show a significant defect in cell wall organization (Figure 2F). The cdc3Δ cdc12Δ double mutant was viable at 24°C with a cellular morphology similar to that of either of the single mutants (data not shown). Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) analysis of the septa from the cdc3Δ cdc12Δ mutant grown at 24°C revealed a defect in the positioning of the primary septum (Figure 2E, panels 5 and 6). Although this was the case, some cells possessed nearly normal septa (Figure 2E, panel 4). In addition, a cell wall-like material penetrated the area within the bud neck in various cells of the septin mutant but never in the wild type cells (Figure 2E, panel 6). Microscopic examination of nuclei stained with DAPI in cultures grown either at 24°C, 30°C, or at 37°C for 5 h showed that all cells had no more than one nucleus at 24°C (Figure 2F). In contrast, at 30°C (n = 200) and at 37°C (n = 400), 8% and 14% of cells, respectively, of the cdc12Δ mutant but not the wild type became multinucleate. All of the multinucleate cells exhibited aberrant morphology (Figure 2F). In summary, none of the septin genes appears essential for growth at room temperature or under non-stress conditions. However, CDC3, CDC11, and CDC12 are essential at 37°C and mutations in these genes lead to a partial defect in septation at 24°C and may result in a defect in cell wall organization.

Septin mutant strains are less virulent in a heterologous host

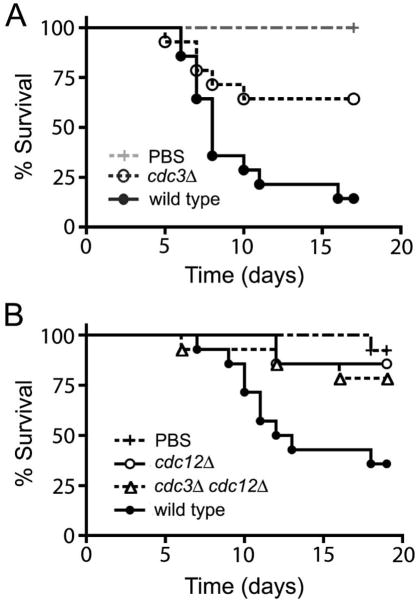

In addition to temperature sensitivity, yeast cells of the septin mutant strains were sensitive to other stresses and cell wall damaging agents. Strains that cannot grow at 37°C are expected to be avirulent in the mammalian host. However, it remained possible that septins contribute to virulence through additional pathways that are independent of high temperature growth. To test whether septin proteins contribute to virulence of C. neoformans at permissive growth temperature, septin mutant strains were injected into larvae of Galleria mellonella (Mylonakis et al., 2005). The larvae were incubated at 24°C. A significant decrease in virulence was observed for the α cdc3Δ mutant strain as compared to the wild type α H99 strain (Figure 3A, p < 0.01). In an independent experiment, the a cdc12Δ mutant and the a cdc3Δ cdc12Δ double mutant were significantly less virulent than the wild type a KN99 strain (p = 0.005, p = 0.023) and not significantly more virulent than the PBS negative control (Figure 3B, p = 0.57, p = 0.3). These studies indicate that septins contribute to virulence through mechanisms that are independent of high temperature growth.

Figure 3.

Septin mutant strains are less virulent in a heterologous host. An α cdc3Δ mutant strain was injected into larvae of Galleria mellonella. The larvae were incubated at 24°C to eliminate the influence of the non-permissive temperature. A significant (p < 0.01) decrease in virulence was observed for the α cdc3Δ mutant strain as compared to wild type (α H99) strain. (B) The a cdc12Δ mutant and the a cdc3Δ cdc12Δ double mutant were significantly less virulent than the wild type a KN99 strain (p = 0.005, p = 0.023) and not virulent when compared to the PBS control (p = 0.57, p = 0.3).

In addition to the ability to grow at high temperature, production of melanin and the polysaccharide capsule, promote virulence of Cryptococcus (Bose et al., 2003; Janbon, 2004; McFadden and Casadevall, 2001). Strains deleted for either CDC3 or CDC12 produced levels of melanin similar to wild type and the capsule size of the septin mutants was also not significantly different from wild type (data not shown). Thus, the septin mutant strains may be less virulent due to a general failure to cope with stress, possibly attributable to compromised cell wall synthesis or integrity.

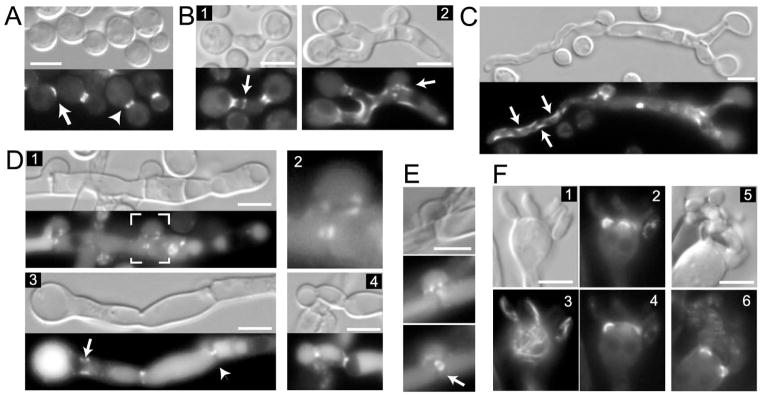

Localization of septins in yeast cells and post-mating hyphae

To address the role of septins in physiology and virulence of C. neoformans, the localization of septin proteins was studied. Cdc10 was tagged with the fluorescent protein mCherry. We reasoned that Cdc10-mCherry would be a good candidate to examine localization of the septin complex since CDC10 is not essential and presumably adding a fluorescent tag to Cdc10 would have a minimal negative impact on the structure of the septin complex. The mCherry-encoding sequence was integrated at the 3′-terminus of the endogenous gene, allowing expression from its native promoter. Subsequently, a Cdc3-mCherry fusion was isolated and its localization compared to Cdc10-mCherry. A Cdc11 chimera with a GFP tag at the N-terminus was also constructed and expressed from the constitutive histone promoter as an ectopic integration. Generating mCherry fusions resulted in viable strains at 37°C without significant morphological abnormalities, indicating that the fusion proteins are functional (data not shown).

Cdc10-mCherry, Cdc3-mCherry, and GFP-Cdc11 localized to the mother-bud neck in yeast cells (Figure 4A and data not shown). In unbudded cells, all three protein chimeras formed a single patch or a ring. In cells with small or medium sized buds, they formed a collar at the neck, whereas cells with large buds displayed a double ring. This localization pattern is similar to the localization previously described in S. cerevisiae (Haarer and Pringle, 1987). Based on these observations and previous studies, we conclude that Cdc3, Cdc10, and Cdc11, most likely together with Cdc12, form a complex at the bud neck of yeast cells.

Figure 4.

(A) Cdc10-mCherry was visualized in yeast cells. An arrow shows a fluorescent patch signal in an unbudded cell, and the arrowhead shows a septin ring that is split during cytokinesis (B–F) Localization of Cdc10-mCherry in dikaryotic post-mating hyphae. A strain expressing Cdc10-mCherry was crossed to a strain of opposite mating type that was wild type or also expressed Cdc10-mCherry. (B) Initial zygotes were examined after 2 days of mating. Cdc10-mCherry was expressed by mating type a (panel 2), or both mating types (panel 1 and C, D, E). (C) Cdc10-mCherry accumulates on the curvatures in the cortex of “pioneer” hypha (indicated by arrows). (D) Cdc10-mCherry localizes to the clamp cell. Panel 1 shows a hypha containing two clamp cells, one of which (indicated by white outline) is magnified in panel 2. Septa formed just beneath the clamp cell and between the clamp cell and the hypha are clearly seen in the DIC image (panel 1). Cdc10-mCherry accumulates on both sides of septa as two puncta in the center. It also outlines the point of fusion between the hypha and the clamp cell (See also Figure 9). Cdc10-mCherry localizes to the base of the basidium (panel 3, arrow), medial point in the septum (panel 3, arrowhead), and to the septa at points of constriction of the hypha (panel 4). (E) Cdc10-mCherry is visible as a ring in the center of the hyphal septum. (F) A strain expressing Cdc10-mCherry was crossed to a strain expressing GFP-βTub. Cdc10-mCherry localizes to the bases of emerging spores on the basidium (panels: 2, 4, 6) but not to the connection points between individual spores (panel 6). Localization of GFP-βTub is shown in panel 3. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

The Cns5 putative septin was also tagged with mCherry but no fluorescent signal was detected in yeast cells. In western blot analysis, no Cns5-mCherry protein was detected in extracts from yeast cells and only a very low level of protein was present in extracts from post-mating hyphae (data not shown). In post-mating hyphae no significant signal or localization of Cns5-mCherry was detected (data not shown). To address the question as to whether Cns5 is indeed a septin, a GFP-Cns5 construct was expressed ectopically from a histone promoter and the localization was examined. GFP-Cns5 was expressed in yeast cells, based on both the cytoplasmic fluorescent signal and western blot analysis (data not shown). However, no characteristic bud neck localization was detected. These data suggest that Cns5 is not a part of the septin complex in yeast cells, and thus may not be a septin protein.

To examine the localization of septins in the dikaryotic hyphae, two strains of opposite mating type and expressing either Cdc10-mCherry or Cdc3-mCherry were co-inoculated on MS mating medium. During mating, two opposite mating type cells of C. neoformans fuse through a projection generated by one or both cells (Hull and Heitman, 2002). Subsequently, the zygote generates projections that grow into hyphae (Figure 4B). One of the landmark features of basidiomycetes is the clamp cell, which is essential for the proper segregation of nuclei in the dikaryotic hyphae (Casselton and Olesnicky, 1998). The clamp cell emerges from the hypha and grows as a bent protrusion that subsequently fuses with the same hypha following septum formation. The septum forms just beneath the clamp cell and divides the hypha into two cells. Following cell fusion, the initial hypha is straight and relatively thick (Figure 4B, panel 2). This initial hypha generates the clamp cell (Figure 4B, panel 2, arrow) and the hyphal tip subsequently grows into a relatively narrow hypha, which has a wandering orientation (Figure 4C). We refer to this type of hypha as the “pioneer” hypha.

Two days after mixing strains of opposite mating type on mating medium, Cdc10-mCherry formed a collar at the base of the mating projection (Figure 4B, panels 1, 2) and accumulated at the site that likely corresponds to the point of fusion between two cells (Figure 4B, panel 1, arrow). Cdc10-mCherry was visible as dot-like spots in the clamp cell (Figure 4B, panel 2, arrow). Cdc10-mCherry also decorated curved surfaces of hyphae, including the “pioneer” hyphae (Figure 4B, panel 2, and Figure 4C, arrows). Several days after mating initiation the majority of hyphae consists of thick branches decorated with clamp cells, whereas the thin “pioneer” hyphae are rarer and grow either from hyphal tips or clamp cells. In most of the clamp cells examined, Cdc10-mCherry localized as two puncta on each side of the septum that is formed between the clamp cell and the main hypha (Figure 4D, panels 1 and 2). Cdc10-mCherry also decorated the cortex of the clamp cell in the region where the clamp cell fuses with the main hypha. At the site corresponding to the septum in the main hypha, Cdc10-mCherry localized as two puncta on either side of the septum (Figure 4D, panel 3, arrowhead), or occasionally as either single puncta in the middle (data not shown), or as a ring in the middle (Figure 4E, arrow). Complete co-localization with the entire septum was observed rarely (Figure 4D, panel 4). In addition to punctate localizations, most hyphal cells showed either general cytoplasmic localization of Cdc10-mCherry with a significantly brighter signal at the cell cortex (Figure S2A), or a localization that likely corresponds to the vacuole filling nearly the entire hyphal cell (Figure 4D, panel 3). Cdc3-mCherry revealed a similar localization in the dikaryotic hyphae (Figure S2C, D, E and data not shown).

Spores of C. neoformans are produced on a specialized oval shaped cell called the basidium, which develops at the apical terminus of the hypha. Prior to the formation of spores, the two parental nuclei fuse and undergo meiosis. At the apical part of the basidium, four bud-like protrusions are formed and subsequent mitotic divisions of the post-meiotic nuclei generate four spore chains. In the basidium, Cdc10-mCherry localized to the bases of all four emerging spores as rings or collars (Figure 4F, panels 2, 4 and 6). Interestingly, 7 days after cells were mixed on MS medium, approximately 41% (12 out of 29 examined) of basidia that carried four budded protrusions or chains of spores showed a Cdc10-mCherry signal at the base of each of the protrusions. In the basidia bearing chains of spores, Cdc10-mCherry was visible only immediately adjacent to the basidium and it was absent from the connection points between individual spores in the chain (Figure 4F, panel 6 and data not shown). 9 days after mixing the cells, ~30% (17 out of 56 examined) of basidia showed Cdc10-mCherry at the base of spores. This percentage decreased to 12% (3 out of 24) by 11 days after mating initiation. 21 days after mating initiation, no basidia with Cdc10-mCherry at the base of budded protrusions were found. Cdc3-mCherry also localized to the bases of the initial protrusions in the subset of the basidia (Figure S2E). Thus, it appears that septins form a complex at the base of the initial buds in the basidium early during development and this complex disassembles at later times. In a small fraction of the basidia, Cdc10-mCherry formed a zone of localization at the base of the basidium, either as a single ring, a diffused collar, or as two puncta on each side of the hypha (Figure 4D, panel 3, arrow, and S2C).

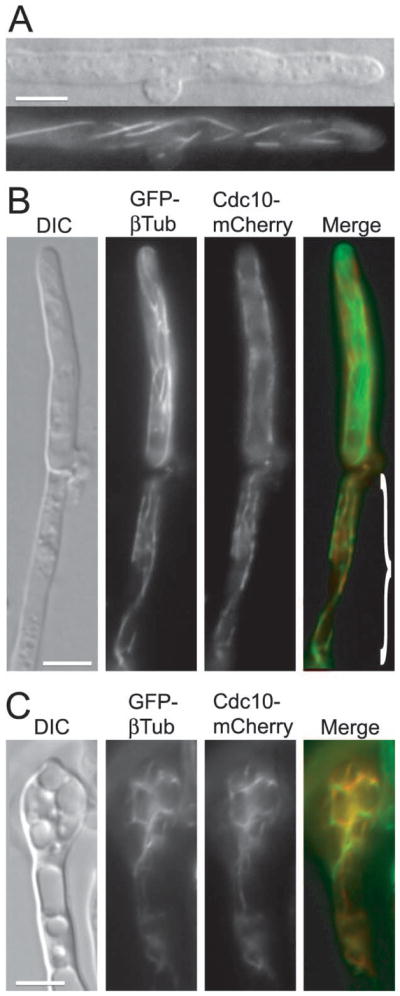

In a small percentage of hyphae (estimated at 4%), Cdc10-mCherry formed filaments along the hyphal cell (Figure 5A, S2A and B and Table 3). This localization is reminiscent of microtubule filaments reported previously in the hyphae of filamentous fungi (Harris, 2006). To test whether Cdc10-mCherry co-localizes with microtubules, a GFP-βTubulin (GFP-βTub) chimera was generated and expressed from the histone promoter. A strain expressing Cdc10-mCherry was crossed to a strain expressing GFP-βTub and the post-mating dikaryotic hyphae were analysed. GFP-βTub defined filaments reminiscent of those observed for Cdc10-mCherry (Figure 5B and Figure S2A). In most cells, Cdc10-mCherry did not co-localize with GFP-βTub. However, in a small fraction of cells (estimated at ~5%) partial co-localization of GFP-βTub and Cdc10-mCherry was detected (Figure 5B, S2A, and Table 3). In most basidia, GFP-βTub formed filaments that spanned the cell or formed a bar, most likely corresponding to the spindle, whereas Cdc10-mCherry decorated the bases of emerging spores (Figure 4F) or filled the entire basidium. However, in a small subset of basidia (~6%), both GFP-βTub and Cdc10-mCherry co-localized as filaments surrounding large vacuoles (Figure 5C, and Table 3). Occasionally, Cdc10-mCherry formed filaments that traversed the hypha and the adjacent basidium (Figure S2B). Filament-like localization of Cdc3-mCherry was also observed, albeit less frequently compared to Cdc10-mCherry (data not shown). Together, these data show that septins persist in the clamp cells and septa, whereas the localization at the bases of emerging spores on the basidium is temporal. In addition, septins localize to the cell cortex or accumulate in the vacuolar compartments in the hyphae. Occasionally, septins may also co-localize with microtubules as filaments.

Figure 5.

Septins occasionally co-localize with microtubules in the dikaryotic hyphae. (A) Two opposite mating type strains expressing Cdc10-mCherry were crossed. Septin filaments spanning the hypha were observed in a small subset of post-mating hyphae. (B and C) A strain expressing Cdc10-mCherry was crossed to a strain expressing GFP-βTub. A rare co-localization of Cdc10-mCherry and GFP-βTub was observed in parts of hyphae (demarcated in B merged image) and in basidia with large vacuoles (C). Scale bars represent 5 μm.

Table 3.

Localization of Cdc 10-mCherry and GFP-βTub in the dikaryotic hyphae

| Type of cells examined | Total number examined (basidia with 4 appendages) | Cells with septin-microtubule colocalization | Cells with Cdc10-mCh dispersed in the whole cell | Cells with Cdc10- mCh filaments | Cells with Cdc10- mCh at cell cortex | Cells with Cdc10-mCh at the base of emerging spores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyphal cells | 173 | 8 (4.6%) | 22 (12.7%) | 7 (4%) | 35 (20.2%) | - |

| Basidia | 53 (19) | 3 (5.7%) | 23 (43.4%) | 2 (3.8%) | 11 (20.8%) | 9 (47.4%) |

Cdc3 and Cdc12 are essential for proper morphology of dikaryotic hyphae

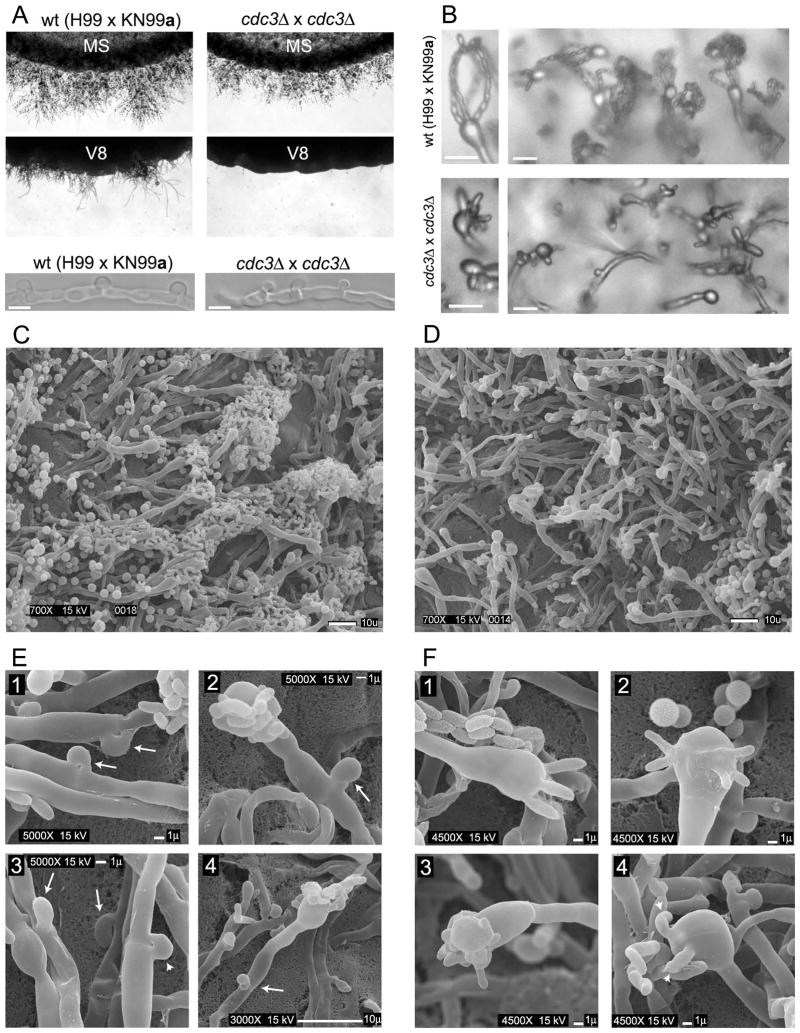

Localization of septins in post-mating hyphae indicated a possible role in the development and morphology of clamp cells and basidia. To test this hypothesis, bilateral crosses of two septin deletion strains (either cdc3Δ or cdc12Δ) were evaluated. Cells of opposite mating type were mixed on either V8 or MS mating medium and incubated in the dark at room temperature. After 2 days, cultures were examined for the formation of zygotes. Initially the number of zygotes was low for both the wild type and the mutants and no difference was observed between the strains (data not shown). After 7 days the control wild type α H99 x a KN99 cross showed, as expected, robust filaments at the edges on MS medium and less abundant filaments on V8 medium (Figure 6A). In contrast neither cdc3Δ nor cdc12Δ bilateral crosses showed efficient filamentation on V8 medium (Figure 6A and data not shown). However, both deletion mutants were able to form filaments on MS medium (Figure 6A and data not shown). Close examination of these filaments by light microscopy and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) revealed two significant differences as compared to the wild type cross. First, most clamp cells on the hyphae formed by septin deletion mutants were not fused (Figure 6A). Out of 100 clamp cells examined from the cross between H99α and KN99a wild type strains, 91 clamp cells were fused. In contrast, in a cdc3Δ x α cdc3Δ and a cdc12Δ x α cdc12Δ crosses only 17 out of 100 and 25 out of 100 clamp cells were fused, respectively. Second, whereas most basidia formed by the wild type cross were decorated with chains of spores, none of the basidia formed by septin mutants bore spore chains (Figure 6B–D). However, basidia from the septin mutants carried budded protrusions. The number of protrusions varied between 1 and 5. In addition, some of these protrusions had an aberrant morphology involving unusually large sizes (Figure 6B and F and Figure S3E). In the wild type, the basidium is formed after the clamp cell has fused. In contrast, in the bilateral septin mutant cross basidia were often found accompanied by unfused clamp cells (Figure 6E, panel 4 and Figure S3A). The spores from the wild type cross of serotype A have a rough surface but the first buds growing immediately from the basidium have a smoother surface (Velagapudi and Heitman, personal communication). In contrast, budded protrusions on the basidia from the septin mutant cross often had a rough surface (Figure S3B). Unilateral crosses between septin deletion mutants and the wild type strain showed no apparent defects in mating or morphology of the hyphae (Figure 6C, E panel 1, F panel 1 and data not shown).

Figure 6.

Cdc3 and Cdc12 are essential for proper morphology of dikaryotic hyphae. (A) A bilateral cross between two cdc3Δ mutant strains was evaluated for filamentation on either MS or V8 media and compared to the H99α x KN99a cross. A severe defect in filamentation of cdc3Δ was observed on V8 medium and only a moderate defect on MS medium. In the cdc3Δ mutant cross, the number of fused clamp cells was reduced in filaments formed on the MS medium (A, bottom 2 panels). (B) Basidia formed by the wild type cross were decorated by chains of spores (B, top), while none of the basidia formed by septin mutants had spore chains (B, bottom). (C–D) Scanning Electron Microscopy was performed to analyze hyphae from bilateral crosses between cdc12Δ mutants and a control cross between cdc12Δ and the wild type H99 strain. Hyphae from cdc12Δ x H99 cross were rich in basidia decorated with chains of spores (C), whereas cdc12Δ x cdc12Δ hyphae lacked spore chains (D). The majority of clamp cells from the cross with the wild type strain were fused (E, panel 1, arrows). In contrast most clamp cells from the cross with the cdc12Δ mutant were not fused (E, panel 3, arrows, fused clamp cell is indicated by an arrowhead) including clamp cells that were formed next to basidia (panels 2 and 4, arrows). Unlike wild type basidia (F, panel 1), most basidia from the cdc12Δ mutant cross had aberrant budded protrusions including atypical numbers (F, panels 2 and 4) and aberrant morphology (F, panel 3). Bars are 5 μm (A, B), or as indicated (C–F).

Cdc3 is essential for proper morphology of hyphae during monokaryotic fruiting

In addition to the a-α sexual cycle, haploid C. neoformans α strains can also undergo a developmental transition involving filamentation and sporulation, known as haploid or monokaryotic fruiting, which is a form of α-α same sex mating (Lin et al., 2005; Wickes et al., 1996). To test whether septins are essential for this developmental process, the CDC3 gene was deleted in strain XL280, a serotype D strain that fruits robustly on MS medium. The cdc3Δ mutant was inviable at 37°C, similar to mutants generated in serotype A strains (data not shown). Both wild type XL280 and the cdc3Δ mutant underwent filamentation on MS and V8 media and no difference was observed after 1 day (Figure S4A). Within 14 days, filaments generated by the wild type on the MS medium were significantly longer as compared to the septin mutant. The length of filaments on V8 medium was similar for both the wild type and the mutant. However, whereas the wild type developed basidia decorated with spore chains, the basidia of the cdc3Δ mutant lacked chains of spores (Figure S4B and C). Additionally, basidia formed by the septin mutant exhibited an aberrant morphology (Figure S4C). This indicates that septins are necessary for the formation of spore chains during both a-α mating and α-α monokaryotic fruiting.

In the absence of Cdc3 or Cdc12, other septins do not form functional complexes

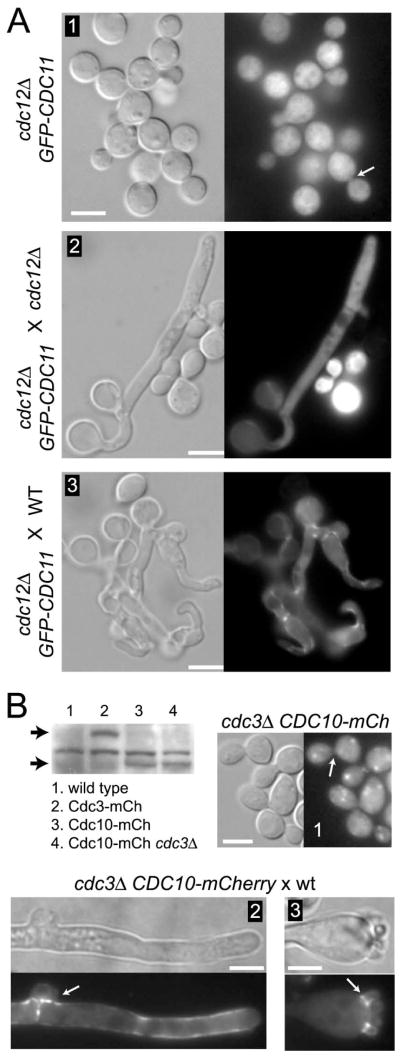

Septins have the propensity to form filaments comprised of several different septin proteins (Barral and Kinoshita, 2008; Versele and Thorner, 2005). According to current models, in organisms that contain more than two septin genes, septins must form a heteromeric complex in order to function (Spiliotis and Nelson, 2006). In the absence of one of the septins, either the structure of the complex is compromised or it fails to form. To test if this is true in C. neoformans, the localization of septins in the absence of Cdc3 or Cdc12 was examined. To this end, Cdc10-mCherry was expressed in a cdc3Δ background and GFP-Cdc11 in a cdc12Δ background. Fluorescent septin chimeras did not localize to the mother-bud neck in yeast cells, even though the proteins were expressed based on PAGE and western blot analysis (Figure 7A, panel 1 and 7B). Neither Cdc10-mCherry nor GFP-Cdc11 showed any specific localization, other than cytoplasmic, in the post-mating hyphae formed by the cross between septin mutants (Figure 7A, panel 2 and data not shown). In contrast, both Cdc10-mCherry and GFP-Cdc11 localized to clamp cells, septa, and bases of the first emergent spores when the septin deletion strains were crossed with a wild-type strain (Figure 7A, panel 3, 7B, panels 2, 3 and data not shown). These data strongly suggest that in the absence of either Cdc3 or Cdc12, other septins do not form functional complexes. In summary, our data support the model that septins assemble into complexes essential for the formation of spore chains on the basidia and for the fusion of clamp cells in post-mating dikaryotic hyphae.

Figure 7.

In the absence of Cdc3 or Cdc12 localization of other septins is disrupted. (A) In the cdc12Δ GFP-CDC11 mutant strain (LK177), GFP-Cdc11 is not localized to the bud neck (panel 1, arrow). When the strain LK177 is crossed to a cdc12Δ mutant, GFP-Cdc11 reveals a diffuse signal throughout the cytoplasm of the dikaryotic hyphae (panel 2). In contrast, when the strain LK177 is crossed to a wild-type, GFP-Cdc11 shows a wild type localization (panel 3). (B) Cdc10-mCherry is expressed in a cdc3Δ mutant strain as shown in the western blot but does not localize to the bud neck (panel 1, arrow). In the western blot, the two arrows indicate Cdc3-mCherry (lane 2) and Cdc10-mCherry (lane 3) proteins migrated near their predicted sizes (~81 kDa and ~64 kDa). The localization of Cdc10-mcherry is “rescued” when the cdc3Δ CDC10-mCherry mutant is crossed to a wild type strain (panel 2 and 3). Scale bars represent 5 μm.

Dikaryotic hyphae from the crosses between septin deletion mutants exhibit aberrant nuclear distribution

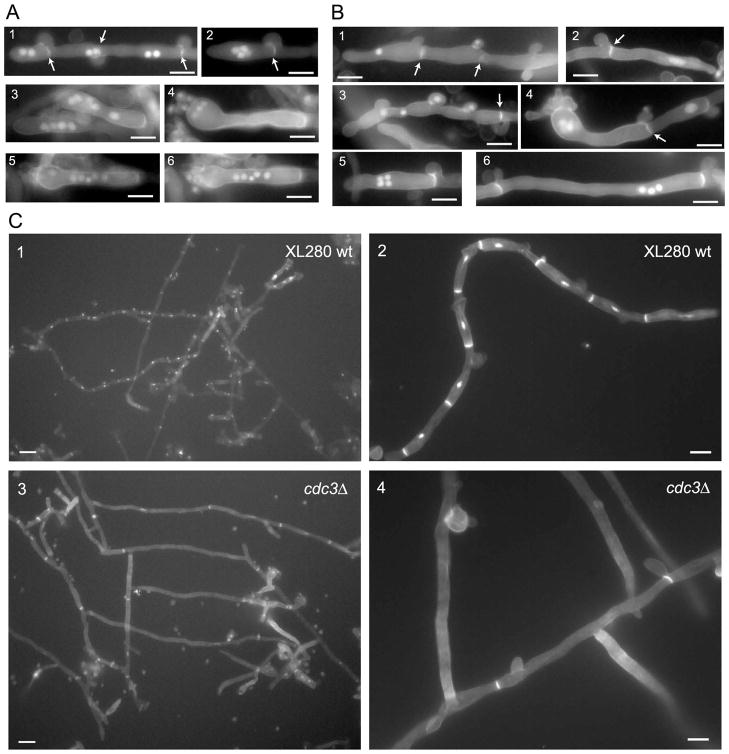

Because clamp cells have been shown to participate in nuclear dynamics in the dikaryotic hyphae, we hypothesized that septin mutations would perturb nuclear distribution. To test this hypothesis, nuclei and septa in the post-mating hyphae formed upon mating of the septin deletion mutants were visualized. Three deletion mutants were evaluated in bilateral crosses: cdc3Δ, cdc12Δ, and the cdc3Δ cdc12Δ double mutant (Figure 8A and B and data not shown). Deletion of septins did not affect septation, as hyphae from both the wild type and the septin mutants were decorated by septa (Figure 8). Hyphae from the cross between wild type strains were typical dikaryons with a pair of nuclei in each hyphal cell demarcated by septa on each side just below the clamp cells (Figure 8A, panel 1, arrows). Notably, in the wild type cross some of the apical cells were modestly enlarged in the middle and contained four nuclei (Figure 8A, panel 2). Apical cells containing four to six nuclei linearly distributed within the cell were also observed (Figure 8A, panel 3). Basidia frequently contained four to six nuclei (Figure 8A, panels 4–6).

Figure 8.

Septins participate in nuclear distribution in hyphae. (A and B) Hyphae from a wild type α H99 x a KN99 cross (A) or from crosses between septin mutant strains (B, α cdc3Δ x a cdc3Δ, panels: 1, 4, and 6; α cdc3Δ cdc12Δ x a cdc3Δ cdc12Δ, panels: 2, 3, and 5) were stained with DAPI and calcofluor white to visualize nuclei and septa. (B) Dikaryotic hyphae from the crosses between septin deletion mutants have aberrant nuclear distribution. (C) Nuclei and septa were examined in hyphae resulting from monokaryotic fruiting of either a reference XL280 strain or a congenic cdc3Δ strain. See text for detailed description. Scale bars represent 5 μm (A, B and C panels 2 and 4) or 10 μm (C panels 1 and 3).

In contrast, distribution of nuclei in hyphae of the septin deletion mutants was more heterogenous (Figure 8B). Hyphal compartments that had fused clamp cells usually contained two nuclei (data not shown). However, most cells that were decorated with unfused clamps contained no nuclei (Figure 8B, panel 1) or had only one (Figure 8B, panels: 1, 2, and 4), or occasionally three nuclei (Figure 8B, panel 6). Nuclei were also observed entrapped in the clamp cells (Figure 8B, panel 1 and 3), a phenomenon also apparent in the wild type hyphae but at a significantly lower frequency (estimated frequencies were 35% for the cdc3Δ mutant, 26% for the cdc12Δ mutant, and 12% for the wild type). Another characteristic of the mutant hyphae was that some septa formed at the wrong position relative to the clamp cell. In the wild type, the septum forms immediately below the clamp cell (Figure 8A, panel 1). In contrast, in the cdc3Δ and cdc12Δ mutant hyphae 13% and 8% of septa formed on the wrong side relative to the direction of clamp cell bending (Figure 8B, panel 2). The majority of the basidia lacked nuclei (data not shown). However, apical cells containing four nuclei (Figure 8B, panel 5) as well as basidia that contained nuclei albeit with an aberrant morphology of the spores were observed (Figure 8B, panel 4). In summary, these data suggest that septin mutants have a partial defect in nuclear distribution in the dikaryotic hyphae, possibly stemming from defects in clamp cell fusion.

Septins are needed for proper nuclear distribution during monokaryotic fruiting

A role for septins in nuclear distribution within post-mating hyphae could be explained by two alternative models. The first possibility is that septins play no direct role in nuclear dynamics but are necessary for efficient clamp cell fusion. In this model the defect in nuclear distribution of septin mutants arises as a consequence of the failure to fuse clamp cells. An alternative model is that septins have a role in maintaining nuclear dynamics that is independent of clamp cell fusion. To differentiate between these models, nuclear distribution was analyzed in the hyphae generated by monokaryotic fruiting of either a wild type XL280 strain or a congenic cdc3Δ strain. Clamp cells of the hyphae resulting from monokaryotic fruiting do not fuse (Lin et al., 2005). Therefore, if nuclear distribution of the cdc3Δ mutant is similar to that of the wild type, this would indicate that a nuclear defect during mating is most likely caused by unfused clamp cells. On the other hand, if the cdc3Δ mutant strain has a defect in nuclear distribution during monokaryotic fruiting, this would suggest that septins play a role in nuclear dynamics that is independent of clamp cell fusion.

Hyphae were stained with DAPI and calcofluor white to visualize nuclei and septa, respectively. Hyphae of the wild type XL280 strain were a typical monokaryon with regularly spaced septa that delineated a single nucleus in each compartment (Figure 8C, panel 1 and 2). Occasionally, a nucleus undergoing mitosis or two nuclei were observed in a single compartment (data not shown). In contrast, in hyphae of the cdc3Δ mutant septa and nuclei were significantly less frequent (Figure 8C, panels 3 and 4). A small percentage of hyphal branches had septa and nuclear distribution similar to the wild type. To compare the wild type and the septin mutant, nuclei in the hyphae were counted in ~4 mm of hyphae of the wild type and ~5 mm of hyphae of the cdc3Δ mutant. Wild type hyphae contained an average of ~40 nuclei in 1 mm length, whereas the cdc3Δ mutant had an average of 14 nuclei per 1 mm length. In addition, hyphae of the septin mutant appeared to contain more long branches that connected neighboring filaments (Figure 8C, panel 3). These data suggest that septins participate in nuclear distribution and this role is not dependent upon clamp cell fusion.

Discussion

C. neoformans possesses all of the vegetative septin proteins first described in S. cerevisiae, with the exception of Shs1. The septins Cdc3 and Cdc12 are essential in S. cerevisiae, most likely because they are crucial for the formation of the septin complex at the mother-bud neck, which is necessary for multiple processes including cell wall biogenesis and cytokinesis. We find that in the C. neoformans cdc3Δ or cdc12Δ mutants, Cdc10-mCherry and GFP-Cdc11 do not localize to the mother-bud neck, respectively. Interestingly, despite the presumed lack of robust septin complexes at the neck, the majority of cdc3Δ and cdc12Δ cells proliferate at 24°C without a significant compromise in morphology. We also find that even the cdc3Δ cdc12Δ mutant strain proliferates at room temperature and the morphology is similar to that of the single septin mutants. Based on the TEM studies, we hypothesize that septin localization at the bud neck in C. neoformans is important for proper positioning of the primary septum. The inability to grow in the presence of SDS, a partial growth rescue at 37°C by sorbitol, and the hypersensitivity to caffeine suggests that septin mutants may have a partial defect in cell wall function. Although a lack of requirement of septins for growth has been described previously in other organisms (Nguyen et al., 2000; An et al., 2004), C. neoformans is the first budding yeast in which the absence of septin complexes confers only relatively modest vegetative growth defects.

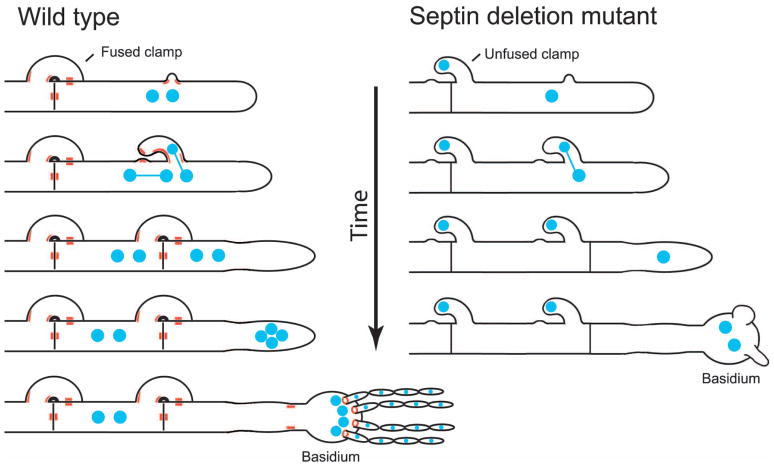

C. neoformans septin complexes are important for the proper morphology of the dikaryotic hyphae although they are not essential for the formation of hyphae. Septin genes are not essential in Ashbya gossypii, but mutants show aberrant branching patterns and wider hyphae (Helfer and Gladfelter, 2006). The morphological consequences of septin deletion seem more severe in Aspergillus nidulans and septins CaCdc3 and CaCdc12 are essential for hyphal growth of C. albicans (Warenda and Konopka, 2002; Westfall and Momany, 2002). Septins in filamentous fungi exhibit a variety of localization patterns presumably associated with distinct roles and regulation mechanisms even within a single cell (Gladfelter, 2006). Similarly, we observe a complex localization of septins in the post-mating hyphae of C. neoformans. Key phases of the development of the dikaryotic hyphae and schematic localizations of septins in C. neoformans based on our observations are illustrated in Figure 9A.

Figure 9.

(A) A model showing localization of septins in the clamp cell and the basidium of the dikaryotic post-mating hyphae. Hypothetically septins mark the initial site of clamp cell formation. Subsequently, septins localize to the base of the outgrowing clamp cell. Possibly septins could also localize to the tip of the clamp cell as well as to the peg, which is a small “bud” growing from the hypha towards the tip of the clamp cell (Badalyan et al., 2004). Septins accumulate on both sides in the middle of the hyphal septum and the septum, which is formed between the hypha and the clamp cell. Septins mark the base of the basidium and form rings at the basal regions of the first set of four budded protrusions that subsequently give rise to four chains of spores. Whereas localizations to the septa and at points of fusion between clamp cells and the hypha appear stable, accumulation of septin complexes at bases of the basidia and initial budded protrusions are transient and likely happen during early stages of the development of the basidium. (B) Hypothetical model showing one possible scenario of defects in nuclear distribution and morphology in post-mating hypae of a septin mutant.

The dikaryotic hyphae of most filamentous basidiomycetes are characterized by fused clamp cells at points of septation that ensure proper distribution of the parental nuclei (Badalyan et al., 2004). We find that clamp cells in hyphae produced by bilateral crosses between cdc3Δ or cdc12Δ mutants often fail to fuse. Also, whereas wild type hyphae are uniformly dikaryotic (except for the apical cells that give rise to the basidia), septin mutant hyphae exhibit significant defects in nuclear distribution and these defects appear to be correlated with the failure in clamp cell fusion. A model illustrating possible defects in morphology and nuclear dynamics due to the lack of septins is depicted in Figure 9B.

The mechanisms underlying clamp cell formation and subsequent fusion are largely unknown (Badalyan et al., 2004). Clamp cell formation and coordinated nuclear divisions are controlled by homeodomain transcription factors, whereas clamp cell fusion is dependent on pheromone and pheromone receptor genes (Casselton and Olesnicky, 1998), and the involvement of the the clampless 1 protein (Clp1) has been decribed (Inada et al., 2001; Scherer et al., 2006; Ekena et al., 2008). We find that septins localize to the base of the clamp cell and close to the point of fusion between the clamp cell and the hypha, indicating that their role in this process could be to facilitate directed exocytosis and growth. On the other hand, in the absence of septins clamp cells are still formed and often exhibit wild-type morphology but fail to fuse frequently.

Why is clamp cell fusion only partially affected in the absence of septins? An intriguing possibility is that septins participate in nuclear movement and/or division in the hyphae. Furthermore, the lack of clamp cell fusion could be a consequence of aberrant nuclear dynamics. Our data showing aberrant nuclear distribution during monokaryotic fruiting of the cdc3Δ mutant suggest that septins play a role in nuclear distribution that is independent of clamp cell fusion. These data, however, do not exclude the possibility that septins also contribute directly to clamp cell fusion. In A. gossypii, septins were shown to provide spatial directions to the mitotic machinery (Helfer and Gladfelter, 2006). The authors hypothesize that septins direct mitosis through the recruitment and local inactivation of AgSwe1p, or alternatively, that the septins influence nuclear dynamics at branches by capturing the ends of astral microtubules. Similar roles of septins are plausible in the hyphae of C. neoformans at the points of clamp cell formation. In support of this model, we observe that septins in C. neoformans often localize to the cortex of hyphal cells where they could mediate microtubule attachment and nucleation. In addition, we observe that septins occasionally co-localize with microtubules as filaments. Also, a role for septins in mediating nuclear movement during cell division has been described previously in budding yeast (Kusch et al., 2002). However, we did not observe a defect in microtubule organization in post-mating hyphae from a bilateral cdc12Δ cross. This conclusion was based on the localization of GFP-βTubulin (data not shown). Clearly, further study is needed to identify the mechanisms by which septins mediate clamp cell fusion and nuclear dynamics. Septins have been shown to co-localize with microtubules under stress conditions (Pablo-Hernando et al., 2008), and nutrient limiting conditions during mating could be responsible for occasional septin-microtubule co-localization.

One of the most striking consequences of the septin deletion was the lack of spore chains decorating the basidia. A similar morphological defect of the aspB-318 septin mutant was described in A. nidulans (Westfall and Momany, 2002). Thus, the role of septins in producing aerial spores seems to be conserved. A. nidulans produces asexual spores on a specialized structure known as the conidiophore, which is analogous to the basidium (reviewed by (Adams et al., 1998)). Interestingly, the localization of the septin AspB to the parts of conidiophore is transient (Westfall and Momany, 2002), which is similar to the temporal accumulation of Cdc10-mCherry at the bases of emerging spores in the basidium. Septins are likely to form a complex at the bases of emerging spores only during early development of the basidium, presumably when the first spores emerge. Alternatively, the septin collar may persist during all subsequent spore formations but disappears soon after the last spore in the chain has emerged.

The most likely explanation for the defect in spore chain formation in the C. neoformans septin mutants is that septins are necessary for the completion of each round of cytokinesis during the formation of subsequent spores. In the absence of septin complexes, the initial appendages form but fail to undergo cytokinesis and the process ceases. Consistent with this model, in the septin mutant we find basidia with appendages that have a rough surface, a feature commonly found on the spores of the wild type strain. This could indicate that the first emerged protrusions develop into spores while the subsequent spores are never formed. Interestingly, we do not find basidia with unusually long buds. This is in striking similarity to the C. neoformans yeast cells lacking septins at the mother-bud neck, which also do not display highly elongated buds in contrast to S. cerevisiae. Moreover, we do not observe basidia with accumulated multiple nuclei, indicating that there must be a checkpoint mechanism which prevents continued nuclear divisions in the presumed absence of cytokinesis. It will be of interest to examine if identical mechanisms operate in the yeast cells and in the basidium that coordinate growth with cell cycle progression in Cryptococcus.

An alternative explanation for the failure to generate spore chains in the septin mutants could be the lack of proper clamp cell fusion and aberrant distribution of nuclei. We find this possibility less parsimonious for two reasons. First, some clamp cells in the septin mutants are fused and some basidia contain the proper number of nuclei, and yet no spore chains were identified. Second, in an XL280 cdc3Δ strain some hyphal cells showed proper nuclear distribution and some basidia contained multiple nuclei but spore chains were absent. Given that strain XL280 is a monokaryon with unfused clamp connections, the lack of sporulation of this septin mutant must result from a defect unrelated to clamp cell fusion.

It is interesting that septins in C. neoformans localized to the medial point in the septa rather than associating with the entire septum, a localization that was shown in other filamentous fungi (Demay et al., 2009; Westfall and Momany, 2002). Moreover septin deletion mutants in C. neoformans do not have an obvious negative effect on the formation of septa. Similar to other basidiomycetes, C. neoformans possesses a specialized channel in the center of the septum called the dolipore (Kwon-Chung and Popkin, 1976), which facilitates communication between individual compartments of the hyphae and whose precise structure remains elusive. It is possible that septins are specifically accumulating at the dolipore structure. It would be of interest to examine whether the dolipore structures are affected in septin mutants.

Septins have been shown to play multiple roles in S. cerevisiae and multicellular eukaryotes. Localization of septins and phenotypic characterization of septin mutants presented here confirm conserved roles of septins in C. neoformans. In addition, our data show novel roles of septins during sexual reproduction and monokaryotic fruiting of C. neoformans. Importantly, septins may contribute to virulence of C. neoformans directly, by being essential for the survival of the yeast cells within the host, and also indirectly by being necessary for the production of spores, which are the presumed infectious propagules. Further analysis of septin biology may aid to elucidate important signaling pathways in C. neoformans and help to treat deadly meningitis caused by this pathogen.

Experimental Procedures

Strains, media and growth conditions

C. neoformans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. V8 medium (pH 5.0 for serotype A and pH 7.0 for serotype D strains) and MS medium were used for mating (Xue et al., 2007). Niger-seed medium was used to test for melanin production and low iron medium was used for evaluation of capsule size. All other media were prepared as described previously (Alspaugh et al., 1997; Bahn et al., 2005; Granger et al., 1985).

Table 1.

List of strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| H99 | α | (Perfect et al., 1993) |

| KN99a | a | (Nielsen et al., 2003) |

| XL280* | α | (Lin et al., 2005) |

| cdc3 | (Liu et al., 2008) | |

| cdc10 | (Liu et al., 2008) | |

| cdc11 | (Liu et al., 2008) | |

| cdc12 | (Liu et al., 2008) | |

| LK64 | α cdc3::NAT | This study |

| LK82 | a cdc3::NAT | This study |

| LK162 | α cdc12::NEO | This study |

| LK174 | a cdc12::NEO | This study |

| LK193 | a cdc3::NAT cdc12::NEO | This study |

| LK197 | α cdc3::NAT cdc12::NEO | This study |

| LK60 | α CDC10-mCherry:NEO | This study |

| LK62 | a CDC10-mCherry:NEO | This study |

| LK130 | α CDC3-mCherry:NEO | This study |

| LK141 | a CDC3-mCherry:NEO | This study |

| LK160 | a cdc3::NAT CDC10-mCherry:NEO | This study |

| LK177 | a cdc12::NEO GFP-CDC11:NAT | This study |

| LK182 | α cdc12::NEO GFP-CDC11:NAT | This study |

| LK128 | a GFP-βTUB:NAT | This study |

| LK101* | α cdc3::NAT | This study |

C. neoformans var. neoformans (serotype D). All other strains are congenic with H99α/KN99a (serotype A).

Melanin production was assayed by spotting C. neoformans overnight cultures on Niger-seed agar medium. The agar plates were incubated at room temperature for 2 days, and pigmentation of fungal colonies was assessed.

To perform mating of C. neoformans, cells of opposite mating type were mixed in water, spotted on V8 or MS agar medium, and cultured at 25°C in the dark. Filamentation was examined by light microscopy.

For analysis of cell viability, 10-fold serial dilutions from overnight liquid cultures were performed and 2 μl of each dilution was spotted on an appropriate medium as indicated in the figure legends. The highest spotted amount of cells was 104 cells.

Disruption of CDC3 and CDC12

The cdc3Δ and cdc12Δ null mutants were generated in the congenic C. neoformans serotype A mating type α (H99) and a (KN99a) and the serotype D XL280 (cdc3Δ only) strains by overlap PCR as previously described (Davidson et al., 2002). Supplementary Table S1 includes primer sequences used for generating deletions and fluorescent protein chimeras. The 5′ and 3′ regions of septin genes were amplified from H99α or KN99a genomic DNA, whereas the dominant selectable markers, NAT (nourseothricin) and Neo (G418), were amplified from plasmid pNATSTM#209 and pJAF1 (Fraser et al., 2003), respectively. The septin gene replacement cassettes were generated by overlap PCR, precipitated onto gold microcarrier beads (0.6 μm; BioRad) and biolistically transformed into strains H99α or KN99a as described previously (Davidson et al., 2000). Stable transformants were selected on YPD medium containing nourseothricin (100 mg/L) or G418 (200 mg/L). To screen for septin mutants, diagnostic PCR was performed. Positive transformants identified by PCR screening were further confirmed by Southern blot. The cdc3Δ cdc12Δ mutant strains were obtained by crossing the single mutants and retrieving the double mutants on double selection NAT/G418 plates.

Generating fluorescent protein chimeras

Primers used to generate fluorescent protein chimeras are listed in Table S1. To make a strain expressing GFP-Cdc11, a plasmid encoding GFP-Cdc11 and containing a NAT-resistant gene was generated. The CDC11 ORF together with 290 bp of 3′UTR sequence (containing the flanking restriction sites for BamHI) was amplified from H99α strain, digested with BamHI and cloned into BamHI-digested and CIP-treated plasmid pCN19 (kindly provided by Connie Nichols from Andrew Alspaugh lab at Duke University). Resulting plasmid pLKB40 expresses GFP-Cdc11 under a constitutive histone promoter. The pLKB40 plasmid was biolistically transformed into strains H99α or KN99a as described previously (Davidson et al., 2000) and positive clones were screened based on the fluorescent signal. Analogous method was used to generate a GFP-βTub-expressing strain. The β-tubulin-encoding sequence (gene CNAG_01840) together with 260 bp of 3′UTR was amplified, digested with BamHI and ligated into BamHI-digested and CIP-treated pCN19, resulting in pLKB37. Positive clones obtained by biolistic transformation were screened microscopically.

Strains expressing mCherry-tagged septins were generated by replacing the STOP codon of the respective septin-encoding gene with the mCherry-encoding sequence through homologous recombination. A method based on the protocol developed for Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Wach et al., 1997) and combined with a modified version of the overlap PCR approach used to delete a gene in C. neoformans (Davidson et al., 2000) was utilized. First, a plasmid containing the mCherry-encoding sequence flanked by a GPD1 terminator and a NEO resistance gene was generated. To this end, a sequence encoding mCherry and GPD1 terminator was amplified from pYH33 (Hsueh et al., 2009) with flanking sequences containing restriction sites for XbaI and XhoI. The PCR product was digested with XbaI/XhoI and ligated into XbaI/XhoI-digested pJAF1 (Fraser et al., 2003) resulting in a plasmid pLKB25. Three DNA fragments that overlap by ~40 bp were generated by PCR: 1.) an ~1 kb region of the sequence immediately upstream of the STOP codon with genomic DNA from the H99α strain as a template, 2.) a sequence containing mCherry and the NEO resistance gene with the pLKB25 as a template and 3). an ~1 kb fragment of the sequence immediately downstream of the STOP codon with genomic DNA from the H99α strain as a template. The three products were combined and used as a template for the overlap PCR. The product of the overlap PCR was introduced into H99α or KN99a strains by biolistic transformation, and the positive transformants were confirmed by PCR and microscopic examination.

Microscopy

For imaging yeast cells, ~0.5 μl of cell suspension was placed on a thin 2% agar patch on the slide and covered with a cover slip. To image the dikaryotic hyphae, small fragments of the mating agar containing mating cells were excised, placed on the slide, and covered by a cover slip.

For filament staining, ~1 cm2 pieces of MS mating medium containing hyphae were excised from the mating plates and moved to small Petri dishes (35 ×10 mm). Samples were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 1 hour, permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and washed three times with PBS. To visualize septa and DNA, samples were incubated in 2 μg/ml DAPI, 1 μg/ml Calcofluor (fluorescent brightener 28 F-3397; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS for 10 min. Analogous staining procedure was used for visualizing nuclei and chitin in yeast cells.

Brightfield, differential interference microscopy (DIC) and fluorescence images were captured with either a Zeiss Axioskop 2 Plus fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with an AxioCam MRm digital camera or with Zeiss Axioscope equipped with an ORCA cooled charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ), and interfaced with MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, Silver Spring, MD). Additional brightfield images were captured with a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope equipped with a Nikon DXM1200F digital camera. Images were processed using Photoshop (Adobe systems, San Jose, CA).

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Sample preparation and imaging was performed with the assistance of Valerie Knowlton at the Center for Electron Microscopy, NC State University, Raleigh, N.C. For TEM the following protocol was used. Yeast cells grown at 24°C to exponential phase were centrifuged and resuspended in 0.1 M Na cacodylate buffer wash, pH 6.8, then centrifuged again and fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Na cacodylate buffer, pH 6.8. Cells were incubated in the fixative at 4°C for several days. The cells were then rinsed with three changes of cold dH2O by centrifugation and further fixed with 4% (aq.) KMnO4 for 2 h on ice and in the dark with occasional shaking. Cells were again rinsed with 6 changes of dH2O as above (beginning cold then bringing to room temperature), until the supernatant was clear. After the last spin, the dH2O was removed and 3 ml of 2% room temperature aqueous uranyl acetate was added to the tubes and the cells resuspended. The tubes were placed in the dark at room temperature for 1 h, followed by two room temperature water washes as above. A small aliquot of cells was removed to pre-embed in 2% agarose for TEM embedding. The agarose pellet containing the cells was cut into 1 mm3 blocks which were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 95%, 100%) for at least 3 h each and then infiltrated with Spurr’s resin (1:1 Spurr’s:ethanol, 3:1 and three changes of 100% Spurr’s resin) for at least 6 h each. Agar blocks were embedded in fresh 100% Spurr’s in BEEM capsules at 70°C for two days. Thin sections were cut with an LKB NOVA Ultrotome III (Leica, Brannockburn IL) and collected on 200-mesh grids, stained 4% with aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 h and Reynold’s lead citrate for 4 min. Grids were viewed using a Philips 400T (FEI Co. Hillsboro OR) TEM.

For SEM, the following protocol was used. Mating was performed on MS medium and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 2 weeks. The mating plate containing mating filaments was fixed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 6.8) containing 3% glutaraldehyde by flooding the entire dish for 24 h at 4°C. The plate was washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 6.8), and areas of interest were excised into 1 mm3 blocks from the cultures, and incubated in the fixation buffer for several weeks at 4°C. Samples were then rinsed in three 30 min changes of cold 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, and post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 2.5 h at 4°C before being viewed by SEM.

Phylogenetic analysis

Homology analysis of septin proteins between Cryptococcus neoformans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae was performed using ClustalW (http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_clustalw.html).

To generate phylogenetic tree comparison of septins in fungi, protein sequences were first aligned using ClustW (http://align.genome.jp/). Next, the aligned sequences were used to generate the phylogenetic tree using PhyML 3.0 aLRT (http://www.phylogeny.fr/version2_cgi/one_task.cgi?task_type=phyml&tab_index=2).

Immunoblotting

Approximately 1 × 107 cells were resuspended in 225 μl of pronase buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1.4 M sorbitol, 20 mM NaN3, and 2 mM MgCl2). TCA (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 17% vol/vol, and samples were stored at −80°C. Cells were homogenized by vortexing with glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C for 10 min. The lysates were collected, and the beads were washed two times with 5% TCA to recover the remaining protein lysates. Precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 4°C. Pellets were dried and resuspended in approximately 30 μl of Thorner buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 8 M urea, 5% SDS, 0.1 mM EDTA, 143 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.4 mg/ml bromphenol blue). Residual TCA was neutralized by the addition of 2 M unbuffered Tris base. Prior to SDS-PAGE, samples were heated for 2 min at 42°C, centrifuged at top speed and supernatants were loaded onto 4–20% polyacrylamide gels.

To detect septin-mCherry chimeras, an anti-DsRed polyclonal antibody (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was used at a 1:1000 dilution. The secondary antibody was an anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated antibody (GE healthcare, UK) used at a 1:10,000 dilution.

Virulence studies

Virulence assays were conducted in Galleria mellonella (wax moth) larvae (Mylonakis et al., 2005). C. neoformans cells were cultured in YPD medium at 24°C to mid-log phase, and the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml. Each G. mellonella larva was injected in the terminal pseudopod with 5 μl of the inoculum. Larvae were incubated at 24°C, and virulence was measured by scoring the survival of the larvae every 24 h.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Andy Alspaugh, Danny Lew, and Raphael Valdivia for critical reading and comments on the manuscript. Thanks to the members of the Heitman lab for their support, especially Robert Bastidas, Yen-Ping Hsueh and Edmond Byrnes for reading and commenting on the manuscript. We thank Valerie Knowlton (Center for Electron Microscopy, NC State University, Raleigh, N.C) for excellent SEM and TEM work and help with imaging. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health AI39115-12 and NIH/NIAID AI42159-09 grants.

References

- Adams TH, Wieser JK, Yu JH. Asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:35–54. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.35-54.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alspaugh JA, Perfect JR, Heitman J. Cryptococcus neoformans mating and virulence are regulated by the G-protein alpha subunit GPA1 and cAMP. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3206–3217. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H, Morrell JL, Jennings JL, Link AJ, Gould KL. Requirements of fission yeast septins for complex formation, localization, and function. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5551–5564. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badalyan SM, Polak E, Hermann R, Aebi M, Kues U. Role of peg formation in clamp cell fusion of homobasidiomycete fungi. J Basic Microbiol. 2004;44:167–177. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200310361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahn YS, Kojima K, Cox GM, Heitman J. Specialization of the HOG pathway and its impact on differentiation and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2285–2300. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral Y, Kinoshita M. Structural insights shed light onto septin assemblies and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose I, Reese AJ, Ory JJ, Janbon G, Doering TL. A yeast under cover: the capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:655–663. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.4.655-663.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce KJ, Chang H, D’Souza CA, Kronstad JW. An Ustilago maydis septin is required for filamentous growth in culture and for full symptom development on maize. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:2044–2056. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.12.2044-2056.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canovas D, Perez-Martin J. Sphingolipid biosynthesis is required for polar growth in the dimorphic phytopathogen Ustilago maydis. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A, Perfect JR. Cryptococcus neoformans. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Casselton LA, Olesnicky NS. Molecular genetics of mating recognition in basidiomycete fungi. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:55–70. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.55-70.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudron F, Barral Y. Septins and the lateral compartmentalization of eukaryotic membranes. Dev Cell. 2009;16:493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RC, Cruz MC, Sia RA, Allen B, Alspaugh JA, Heitman J. Gene disruption by biolistic transformation in serotype D strains of Cryptococcus neoformans. Fungal Genet Biol. 2000;29:38–48. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1999.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RC, Blankenship JR, Kraus PR, de Jesus Berrios M, Hull CM, D’Souza C, Wang P, Heitman J. A PCR-based strategy to generate integrative targeting alleles with large regions of homology. Microbiology. 2002;148:2607–2615. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-8-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demay BS, Meseroll RA, Occhipinti P, Gladfelter AS. Regulation of Distinct Septin Rings in a Single Cell by Elm1p and Gin4p Kinases. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2311–26. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas LM, Alvarez FJ, McCreary C, Konopka JB. Septin function in yeast model systems and pathogenic fungi. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1503–1512. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.9.1503-1512.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekena JL, Stanton BC, Schiebe-Owens JA, Hull CM. Sexual development in Cryptococcus neoformans requires CLP1, a target of the homeodomain transcription factors Sxi1alpha and Sxi2a. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:49–57. doi: 10.1128/EC.00377-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JA, Subaran RL, Nichols CB, Heitman J. Recapitulation of the sexual cycle of the primary fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii: implications for an outbreak on Vancouver Island, Canada. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:1036–1045. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.5.1036-1045.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladfelter AS, Pringle JR, Lew DJ. The septin cortex at the yeast mother-bud neck. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(01)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladfelter AS, Kozubowski L, Zyla TR, Lew DJ. Interplay between septin organization, cell cycle and cell shape in yeast. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1617–1628. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladfelter AS. Control of filamentous fungal cell shape by septins and formins. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:223–229. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Novo A, Labrador L, Jimenez A, Sanchez-Perez M, Jimenez J. Role of the septin Cdc10 in the virulence of Candida albicans. Microbiol Immunol. 2006;50:499–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger DL, Perfect JR, Durack DT. Virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Regulation of capsule synthesis by carbon dioxide. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:508–516. doi: 10.1172/JCI112000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haarer BK, Pringle JR. Immunofluorescence localization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC12 gene product to the vicinity of the 10-nm filaments in the mother-bud neck. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3678–3687. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.10.3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall PA, Russell SE. The pathobiology of the septin gene family. J Pathol. 2004;204:489–505. doi: 10.1002/path.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SD. Cell polarity in filamentous fungi: shaping the mold. Int Rev Cytol. 2006;251:41–77. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)51002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell LH. Genetic control of the cell division cycle in yeast. IV. Genes controlling bud emergence and cytokinesis. Exp Cell Res. 1971;69:265–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(71)90223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfer H, Gladfelter AS. AgSwe1p regulates mitosis in response to morphogenesis and nutrients in multinucleated Ashbya gossypii cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4494–4512. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh YP, Xue C, Heitman J. A constitutively active GPCR governs morphogenic transitions in Cryptococcus neoformans. Embo J. 2009 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull CM, Heitman J. Genetics of Cryptococcus neoformans. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:557–615. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.052402.152652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara M, Tomimoto H, Kitayama H, Morioka Y, Akiguchi I, Shibasaki H, Noda M, Kinoshita M. Association of the cytoskeletal GTP-binding protein Sept4/H5 with cytoplasmic inclusions found in Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24095–24102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara M, Yamasaki N, Hagiwara A, Tanigaki A, Kitano A, Hikawa R, Tomimoto H, Noda M, Takanashi M, Mori H, Hattori N, Miyakawa T, Kinoshita M. Sept4, a component of presynaptic scaffold and Lewy bodies, is required for the suppression of alpha-synuclein neurotoxicity. Neuron. 2007;53:519–533. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada K, Morimoto Y, Arima T, Murata Y, Kamada T. The clp1 gene of the mushroom Coprinus cinereus is essential for A-regulated sexual development. Genetics. 2001;157:133–140. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janbon G. Cryptococcus neoformans capsule biosynthesis and regulation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2004;4:765–771. doi: 10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, Field CM, Coughlin ML, Straight AF, Mitchison TJ. Self- and actin-templated assembly of Mammalian septins. Dev Cell. 2002;3:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajaejun T, Gauthier GM, Rappleye CA, Sullivan TD, Klein BS. Development and application of a green fluorescent protein sentinel system for identification of RNA interference in Blastomyces dermatitidis illuminates the role of septin in morphogenesis and sporulation. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:1299–1309. doi: 10.1128/EC.00401-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusch J, Meyer A, Snyder MP, Barral Y. Microtubule capture by the cleavage apparatus is required for proper spindle positioning in yeast. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1627–1639. doi: 10.1101/gad.222602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Popkin TJ. Ultrastructure of septal complex in Filobasidiella neoformans (Cryptococcus neoformans) J Bacteriol. 1976;126:524–528. doi: 10.1128/jb.126.1.524-528.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Hull CM, Heitman J. Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature. 2005;434:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature03448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey R, Momany M. Septin localization across kingdoms: three themes with variations. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu OW, Chun CD, Chow ED, Chen C, Madhani HD, Noble SM. Systematic genetic analysis of virulence in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell. 2008;135:174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden DC, Casadevall A. Capsule and melanin synthesis in Cryptococcus neoformans. Med Mycol. 2001;39(Suppl 1):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momany M, Zhao J, Lindsey R, Westfall PJ. Characterization of the Aspergillus nidulans septin (asp) gene family. Genetics. 2001;157:969–977. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mylonakis E, Moreno R, El Khoury JB, Idnurm A, Heitman J, Calderwood SB, Ausubel FM, Diener A. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Cryptococcus neoformans pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3842–3850. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3842-3850.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TQ, Sawa H, Okano H, White JG. The C. elegans septin genes, unc-59 and unc-61, are required for normal postembryonic cytokineses and morphogenesis but have no essential function in embryogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 21):3825–3837. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K, Cox GM, Wang P, Toffaletti DL, Perfect JR, Heitman J. Sexual cycle of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii and virulence of congenic a and alpha isolates. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4831–4841. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.4831-4841.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pablo-Hernando ME, Arnaiz-Pita Y, Tachikawa H, del Rey F, Neiman AM, Vazquez de Aldana CR. Septins localize to microtubules during nutritional limitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]