Summary

The relationship between dendritic cells (DCs) and commensal microflora in shaping systemic immune responses is not well understood. Here we report that mice deficient for Fas-associated death domain in DCs developed systemic inflammation associated with elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased myeloid and B cells. These mice exhibited reduced DCs in gut-associated lymphoid tissues due to RIP3-dependent necroptosis, while DC functions remained intact. Induction of systemic inflammation required DC necroptosis and commensal microbiota signals that activated MyD88-dependent pathways in other cell types. Systemic inflammation was abrogated with administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics or complete, but not DC-specific, deletion of MyD88. Thus, we have identified a previously unappreciated role for commensal microbiota in priming immune cells for inflammatory responses against necrotic cells. These studies demonstrate the impact intestinal microflora have on the immune system and their role in eliciting proper immune responses to harmful stimuli.

Introduction

Successful immunity relies on the ability of dendritic cells (DCs) to recognize pathogens, secrete inflammatory cytokines, and present antigens to initiate T cell activation (Banchereau et al., 2000). DCs are present in all tissues and survey their environment to induce protection against infectious agents or tolerance to self-antigens. This is particularly important in the intestinal mucosa where DCs constantly encounter microbes and other foreign antigens. The intestinal microenvironment and commensal microbiota interactions help dictate intestinal DC functions, thereby influencing the functions of other immune cell populations (Coombes and Powrie, 2008; Scott et al., 2011). Thus, the strict regulation of DC activities is important in executing proper immune responses. DC development depends on the cytokine fms-like tyrosine receptor kinase 3 ligand (Flt-3L) (Karsunky et al., 2003; McKenna et al., 2000; Waskow et al., 2008), while cellular homeostasis in the periphery is maintained by processes like apoptosis to prevent disease development (Kushwah and Hu, 2010). DCs commonly undergo apoptosis following antigen presentation to T cells to limit immune responses. Inhibition of apoptosis in DCs triggers the development of systemic autoimmune disease (Chen et al., 2006; Mabrouk et al., 2008; Stranges et al., 2007).

The adaptor protein Fas-associated death domain (FADD) plays a crucial role downstream of all death receptors in the induction of apoptosis (Yeh et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998). The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily of death receptors, including CD95 (Fas), TNF receptor type I (TNF-RI), and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor (TRAIL-R), initiate cell death by recruiting FADD and the protease caspase-8 into a complex, resulting in a cascade of protease activation and eventual cell death (Strasser et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2009). More recent studies, however, have focused on an alternative form of cell death, termed necroptosis or programmed necrosis, that can be initiated by death receptor signaling when apoptosis is blocked (Degterev et al., 2008; Degterev et al., 2005; Moquin and Chan, 2010). Necroptosis requires the kinase activities of the death domain containing kinase RIP1 and its family member RIP3, which interact through their RIP homotypic interaction motif (Cho et al., 2009; He et al., 2009; Sun et al., 1999). Thus, direct inhibition of the RIP1 kinase activity with a small molecule inhibitor, necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) or targeted deletion of RIP3 can block necroptosis (Degterev et al., 2008; Degterev et al., 2005). Recent reports have demonstrated a role for FADD in regulating necroptosis. In the absence of FADD, depending on the tissues being affected, necroptosis occurs and causes detrimental effects including embryonic lethality, lack of T cell proliferation, intestinal and skin inflammation (Bonnet et al., 2011; Ch’en et al., 2011; Osborn et al., 2010; Welz et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011).

Given the critical role of death in regulating DC functions and its subsequent effect in directing immune responses, we sought to examine the function of FADD in DCs. Using DC-specific conditional knockout mice, we found that FADD was essential in limiting DC necroptosis. In the knockout mice, DC numbers were decreased, especially in gut-associated populations, due to uncontrolled DC death. Importantly, the dysregulation of DC death resulted in the appearance of chronic systemic inflammation characterized by increased levels of serum TNF and an expansion in myeloid and B cells. We further identified a critical role for the intestinal microbiota in the development of inflammatory responses to necroptotic DCs that required MyD88-dependent signals in non-DC cells. Our study uncovers an essential connection between the commensal microbiota and necroptosis-induced inflammation.

Results

Decreased Dendritic Cell Numbers in Gut-associated Lymphoid Tissues

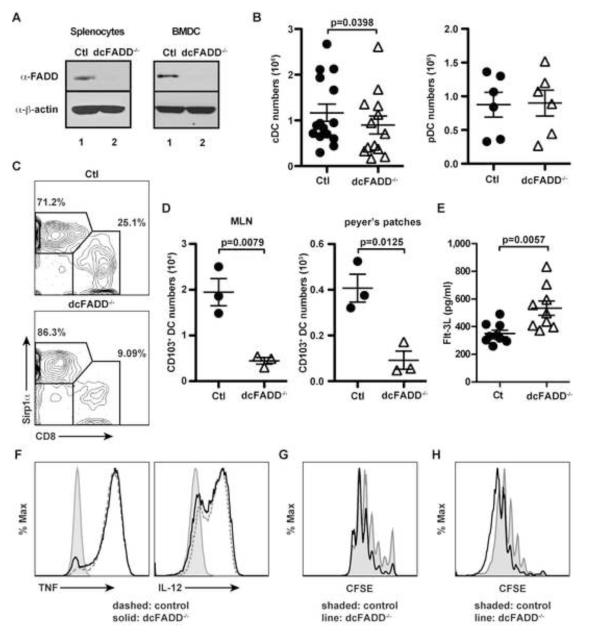

To better understand the role of FADD in DC homeostasis and effector functions, we generated conditional knockout mice by crossing CD11c-Cre transgenic mice to mice containing floxed alleles of FADD (Caton et al., 2007; Osborn et al., 2010). These mice (termed dcFADD−/−) exhibited a specific loss of FADD protein expression in CD11c+-enriched splenocytes and in vitro-generated bone marrow-derived dendritic cell (BMDC) by western blot analysis (Figure 1A). Previous studies have shown that DCs accumulate in the absence of apoptosis, and this subsequently leads to increased lymphocyte activation and autoimmune disease development (Chen et al., 2006; Mabrouk et al., 2008; Stranges et al., 2007). We therefore assessed the DC populations by first examining cell numbers. Unexpectedly, the loss of FADD did not lead to DC accumulation. Instead, a small but significant decrease in the number of CD11chiMHCII+ conventional DCs (cDC) was detected in the spleen of dcFADD−/− mice compared to littermate control mice (Figure 1B), while the number of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC, CD11cloSiglec-H+B220+) in bone marrow was unchanged (Figure 1B). This result is consistent with the restricted expression of Cre recombinase by CD11c-Cre to the cDC but not the pDC population (Birnberg et al., 2008). We further investigated different subsets of splenic cDCs by examining CD8 and Sirp1α expression. Compared to other DC subsets, the CD8+Sirp1a− DC subset has been identified to efficiently cross-present antigens to CD8+ T cells (Shortman and Heath, 2010). In these dcFADD−/− mice, the percentage of CD8+Sirp1a− DCs was diminished, while the CD8−Sirp1α+ subset was increased (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Lower cDC Numbers in dcFADD−/− Mice.

(A) FADD protein expression was assessed in CD11c+-enriched splenocytes and BMDCs by western blotting (Ctl, control). (B) Absolute cell numbers of conventional DCs (cDC: CD11chi) from the spleen, and plasmacytoid DCs (pDC: CD11cloB220+Siglec H+) from the bone marrow were plotted. (C) Splenic cDC (CD11chiMHC II+) subsets were distinguished by CD8 and Sirp1α expression. (D) Intestinal CD103+ DCs in the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and peyer’s patches were isolated, and cell numbers were calculated. (E) Flt-3L amounts in the serum were measured by ELISA. (F) Control (dashed) or dcFADD−/− (solid) BMDCs were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 6 hrs, and intracellular TNF or IL-12 were examined. Histogram plots show cytokine production in CD11c+CD11b+ BMDCs. Shaded, unstimulated; dashed, control; solid, dcFADD−/−. (G) CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were cultured with SIINFEKL-pulsed BMDCs (shaded, control; solid line, dcFADD−/−) for 72 hrs, and OT-I T cell proliferation was measured. (H) CFSE-labeled OT-I cells were adoptively transferred into β2m−/− mice, and SIINFEKL-pulsed BMDCs (shaded, control; solid line, dcFADD−/−) were injected into the footpad 24 h later. 72 h after BMDC injections, the draining popliteal lymph nodes were harvested to examine T cell proliferation. Histograms are representative of duplicate samples and 2 separate experiments (G and H). Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments (A-F). Plots show mean ± SEM and each point represents an individual animal (B, D, E). See also Figure S1.

Since only a modest decrease in the cDC population was detected in the spleen, we investigated changes in DC numbers in other peripheral lymphoid organs, in particular the gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT). The mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and peyer’s patches were examined for CD103+ migratory DCs (Coombes and Powrie, 2008; Scott et al., 2011). Interestingly, we observed a dramatic reduction of CD103+ DCs in the GALT of dcFADD−/− mice compared to the spleen, suggesting that the intestinal microbiota might stimulate DC death (Figure 1D). We subsequently measured the levels of Flt-3L in the serum, since Flt-3L levels have been shown to increase in mice deficient of DCs (Birnberg et al., 2008). We found that Flt-3L was indeed slightly elevated in the sera of dcFADD−/− mice compared to littermate controls (Figure 1E).

The importance of FADD in DC functions was also determined. DCs isolated from the MLNs expressed equivalent levels of MHC and co-stimulatory molecules (Figure S1). Following stimulation with LPS, FADD-deficient BMDCs were capable of inducing TNF and IL-12 similar to that of control BMDCs (Figure 1F). Additionally, the ability to stimulate antigen-specific responses by FADD-deficient DCs was evaluated. Proliferation of ovalbumin-specific CD8 T cells (OT-I T cells) in response to ovalbumin peptide (SIINFEKL)-pulsed BMDC was induced in vitro or in vivo. Both control and FADD-deficient BMDCs stimulated OT-I cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo (Figure 1G and 1H). Taken these data together, the deletion of FADD in DCs does not impair their ability to produce cytokines or to initiate T cell responses. However, dcFADD−/− mice exhibit a striking decrease in the number of gut-associated DCs.

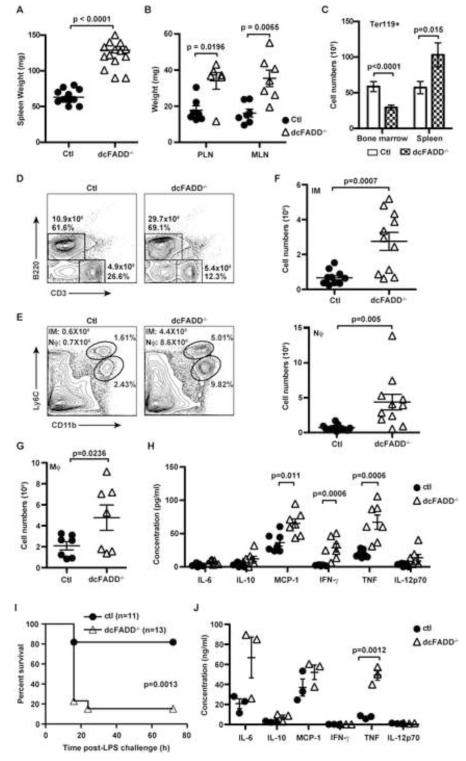

Systemic Inflammation in dcFADD−/− Mice Results in Splenomegaly and Lymphadenopathy

The dcFADD−/− mice at first appeared healthy with no obvious abnormalities. However, by 4- to 8-weeks of age, these mice exhibited splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy compared to littermate controls (Figures 2A and 2B). Increased numbers of Ter119+ erythrocytes contributed to the enlargement of the spleens (Figure 2C). In contrast, erythroid cell numbers in the bone marrow of dcFADD−/− mice were lowered compared to their littermate controls (Figure 2C). We also detected elevated B cell numbers in the spleen and lymph nodes of dcFADD−/− mice (Figure 2D and data not shown). However, the absolute numbers of CD3+ T cells and the proportion of CD4 and CD8 T cells were similar between littermate controls and dcFADD−/− mice (Figure 2D and data not shown). Strikingly, numerous myeloid cell populations were increased in the spleens of dcFADD−/− mice compared to control mice (Figure 2E-2G). Flow cytometric analysis of splenocytes revealed elevated numbers of inflammatory monocytes (Ly6ChiCD11b+) in dcFADD−/− mice compared to control littermates (Figure 2E and 2F). In addition, the neutrophil population (Ly6CloLy6G+CD11b+) in the spleen and blood was also increased (Figure 2E, 2F and S2A). The numbers of F4/80+CD11b+ macrophages were also elevated in dcFADD−/− mice compared to control mice (Figure 2G). Increased numbers of inflammatory monocytes, neutrophils and macrophages were also detected in the lymph nodes (data not shown). These data reveal that the dcFADD−/− mice display signs of systemic inflammation.

Figure 2. dcFADD−/− Mice Exhibit Systemic Inflammation and Increased Sensitivity to LPS Endotoxic Shock.

(A and B) Weights of spleens (A), peripheral (PLN) or mesenteric (MLN) lymph nodes (B) from Ctl or dcFADD−/− mice. (C) Numbers of Ter119+ erythroid in the spleen or bone marrow of Ctl (white bars) or dcFADD−/− (hatched bars) mice (n = 10 for bone marrow, n = 8 for spleen). (D) CD3 and B220 staining to examine splenic B and T lymphocyte populations. Numbers represent total cell numbers and cell percentages. Data are representative of 5 separate experiments. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of inflammatory monocyte (IM: Ly6ChiCD11b+) and neutrophil (Nϕ: Ly6CloLy6G+CD11b+) populations in the spleen. Plots are representative of >5 independent experiments. (F and G) Numbers of IM (F, upper panel), Nϕ (F, lower panel), and macrophages (G, Mϕ: F4/80+CD11b+) in the spleen. (H) Serum cytokine levels (pg/ml) were measured by flow cytometry using Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) (n = 7). (I) Ctl (circles, n = 11) or dcFADD−/− (triangles, n = 13) mice were injected with 100 μg of LPS i.p., and survival was compared. (J) 1 h after LPS injections, the amounts of serum cytokines (ng/ml) were measured by CBA. Bar graph and scatter plots represents mean ± SEM. Each point represents an individual animal and pooled from multiple analyses (A, B, F-H, J). See also Figure S2.

To further assess inflammation in the dcFADD−/− mice, we measured the levels of different pro-inflammatory cytokines in the serum. A significant increase in basal TNF, IFN-γ and MCP-1 amounts was detected in the serum of dcFADD−/− mice compared to control mice (Figure 2H). In contrast, serum levels of IL-1β were undetectable in both dcFADD−/− and control mice (data not shown). To determine the ramifications of having increased inflammation, control or dcFADD−/− mice were given a low dose of LPS (100 μg) without the sensitizing agent D-galactosamine. Under this condition, most wild-type mice survived (Figure 2I). However, dcFADD−/− mice were unable to recover and died of LPS-induced endotoxic shock within 18 hours (Figure 2I). The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF were significantly increased in the sera of dcFADD−/− mice following the injection of LPS (Fig. 2J, 40-60 ng/ml). Elevated IL-1β was also detected (Fig. S2B) but at lower levels (<1 ng/ml). These results indicate that LPS-stimulated death of dcFADD−/− mice is caused by the lethal effects of elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines or by TNF-induced lethal systemic inflammation response syndrome (Duprez et al., 2011). While there are some similarities to mice that completely lack cDCs (Birnberg et al., 2008; Ohnmacht et al., 2009), the dcFADD−/− mice exhibit numerous unique phenotypes. Our data specifically demonstrate that dcFADD−/− mice develop systemic inflammation characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased numbers of inflammatory monocyte, neutrophils, macrophages, and B cells. As a consequence, this increased inflammation enhances sensitivity to LPS-induced endotoxic shock.

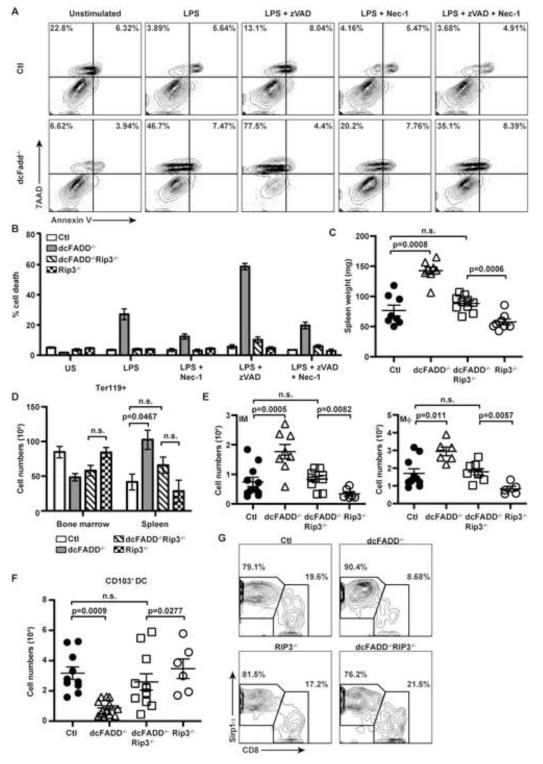

RIP3-dependent Necroptosis is Responsible for DC Death and Systemic Inflammation

We next determined the reason for the reduction in DC numbers, and whether the decrease in DCs was responsible for the systemic inflammation observed in the dcFADD−/− mice.Necroptosis has been described to occur in the absence of apoptosis and requires the kinase activities of RIP1 and RIP3 (Cho et al., 2009; He et al., 2009; Sun et al., 1999). We hypothesized that the lowered DC numbers in dcFADD−/− mice was the result of FADD-deficient DCs dying by necroptosis. Therefore, we first assessed the ability of FADD-deficient DCs to undergo necroptosis in response to TLR stimulation. BMDCs generated from dcFADD−/− or control mice were stimulated with LPS, and cell death was examined by labeling cells with Annexin V and 7AAD. LPS stimulation induced necroptotic cell death (7AAD+/Annexin V−) in FADD-deficient DCs that was not detected in control cells (Figure 3A). Addition of zVAD, a pan-caspase inhibitor, in combination with LPS further increased cell death in both wild-type and FADD-deficient DCs (Figure 3A). Since zVAD blocks apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-8 activity, this result suggested the presence of an alternative caspase-dependent but FADD-independent pathway to death. Interestingly, LPS-induced cell death was only partially rescued by the RIP1 kinase inhibitor Nec-1 implying that LPS stimulated some cells to die by a RIP1-independent manner (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. RIP3 Deletion Prevents DC Necroptosis and Systemic Inflammation.

(A) Control (Ctl, upper panels) and dcFADD−/− (lower panels) BMDCs were pre-treated with either 10 μM zVAD, 30 μM Nec-1, or DMSO and then stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 16 h. Cells were labeled with Annexin V and 7AAD. Data are representative of at least 5 experiments. (B) Ctl (white bars), dcFADD−/− (gray bars), dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− (diagonal bars), and RIP3−/− (hatched bars) BMDCs were stimulated and cell death was measured as in (A, US = unstimulated). Bar graph shows mean percentage of death ± SEM (% 7AAD+/Annexin V−) and representative of at least 3 individual experiments. (C) Spleen weights from Ctl, dcFADD−/−, dcFADD−/−RIP3−/−, or RIP3−/− mice. (D) Ter119+ erythroid cells in the spleen and bone marrow (Ctl (white bars, n = 5); dcFADD−/− (gray bars, n = 3); dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− (diagonal bars, n = 5); or RIP3−/− (hatched bars, n = 4)). (E-F) Number of inflammatory monocyte (IM) and macrophage (Mϕ) in the spleen (E) and CD103+ DCs in the MLN (F). (G) DC subsets in the spleen were assessed by gating on CD11chiMHCII+ cDCs and examining CD8 and Sirp1α expression. Numbers are cell percentages, and plots are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scatter plots represents mean ± SEM (n.s. = not significant). Each point represents an individual animal and pooled from multiple analyses (C-F). See also Figure S3 and S4.

Necrotic cell death was reported to induce IL-1 release and to promote inflammation (Rock et al., 2010). Following LPS stimulation, increased death of dcFADD−/− cells corresponded with elevated levels of mature IL-1β, whereas the induction of TNF was similar between FADD-deficient and control cells (Figure S3A and S3B). Inflammatory contents released by necrotic cells can trigger potassium efflux, resulting in NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1 processing (Petrilli et al., 2007). Inhibition of potassium efflux from cells prevented IL-1β production in dcFADD−/− DCs without altering the amount of cell death (Figure S3D and S3E). These data demonstrate that LPS stimulated dcFADD−/− DCs can undergo necroptosis in vitro and release processed IL-1β.

To further assess necroptosis in DCs, we crossed dcFADD−/− mice to RIP3−/− mice to generate dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− double knockout (DKO) mice. BMDCs were generated from dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− mice, and necroptosis was measured following LPS stimulation. As mentioned above, LPS-stimulated death of FADD-deficient DCs was only partially rescued by Nec-1 (Figure 3A and 3B). However, the deletion of RIP3 completely rescued LPS-induced death (Figure 3B). These data demonstrate that in the absence of FADD, DCs can undergo RIP1-dependent and -independent necroptosis, both of which are dependent on RIP3. In contrast, DC death following TNF treatment was completely rescued by Nec-1, suggesting that programmed necrosis induced by TNF is dependent on both RIP1 and RIP3 (Figure S4A).

We subsequently investigated the role of RIP3-dependent necroptosis in the development of systemic inflammation in dcFADD−/− mice. Strikingly, much of the inflammatory phenotypes detected in the dcFADD−/− mice were abrogated in the dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− mice. The significant increase in spleen weight seen in dcFADD−/− mice was no longer observed in dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− DKO mice, nor was there a difference in the erythrocyte populations (Figure 3C and 3D). Furthermore, the increased numbers of inflammatory monocytes, neutrophils and macrophages observed in the dcFADD−/− mice were not detected in dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− DKO mice (Figure 3E and S4B). While a slight increase in these myeloid populations was detected in the dcFADD−/− RIP3−/− DKO mice compared to RIP3−/− mice, no statistical differences were detected between DKO mice and control mice (Figure 3E and S4B). Normal numbers of myeloid cell populations correlated with decreased levels of inflammatory cytokines in the sera of dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− DKO mice (Figure S4C and data not shown).

Since the deletion of RIP3 in FADD-deficient cells prevented necroptotic death in vitro (Figure 3B), we expected that DC numbers would be rescued in dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− mice. As shown in Figure 3F, similar numbers of CD103+ migratory DCs were detected in the MLNs of dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− DKO and control mice (Figure 3F). Thus, RIP3 deletion prevented FADD-deficient CD103+ DCs from dying. The deletion of RIP3 in dcFADD−/− mice also rescued the proportions of CD8+ and Sirp1α+ DC subsets (Figure 3G). Consequently, Flt-3L levels in the serum of dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− DKO mice were similar to control and RIP3−/− mice (Figure S4D). Furthermore, expression of co-stimulatory molecules was not affected by the absence of RIP3 (Figure S4E). Together these results indicate an obligatory role for RIP3 in dcFADD−/− DC death, and this RIP3-dependent death stimulates the development of systemic inflammation in vivo.

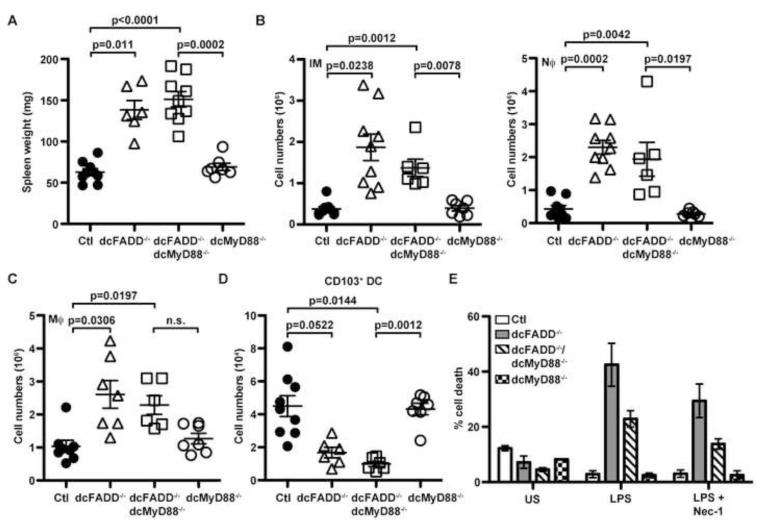

MyD88-dependent Signaling in DCs and Non-DCs is Crucial for Inflammation in dcFADD−/− Mice

In the absence of FADD, DCs died by necroptosis when stimulated with LPS or other TLR ligands as shown above. Therefore, we hypothesized that reduced DC numbers in the GALT of dcFADD−/− mice could be a consequence of necroptosis induced by TLR ligands presented by commensal microflora. Necroptotic DC death may then release DAMPs (Danger Associated Molecular Patterns proteins) capable of activating other innate cells, resulting in inflammation (Kono and Rock, 2008). MyD88 is an adapter molecule for IL-1R and most TLRs (Barton and Medzhitov, 2003; Beutler and Rietschel, 2003). To assess the role MyD88 plays in the dcFADD−/− phenotype, we crossed dcFADD−/− mice to MyD88flox/flox mice to generate dcFADD−/−dcMyD88−/− mice, which specifically deleted both FADD and MyD88 in the DC population. When we examined the dcFADD−/−dcMyD88−/− mice for inflammation, an increase in the spleen weights was still observed (Figure 4A). However, a partial rescue in the numbers of inflammatory monocytes, neutrophils and macrophages was detected, suggesting a reduction in the levels of inflammation (Figure 4B and 4C). These myeloid populations were reduced in dcFADD−/−dcMyD88−/− mice compared to dcFADD−/− mice but slightly increased when compared to control or dcMyD88−/− mice (Figure 4B and 4C). When the CD103+ DC population was examined, cell numbers were significantly decreased in dcFADD−/−dcMyD88−/− mice compared to control or dcMyD88−/− mice (Figure 4D). Despite the dramatic reduction of DCs in the MLNs, cells deficient of FADD and MyD88 were capable of up-regulating MHC and co-stimulatory molecules (Figure S5). LPS stimulation of FADD- and MyD88-double deficient BMDCs still induced death when compared to MyD88-deficient cells, although the percentage of death was slightly lower than in FADD-deficient cells (Figure 4E). These results suggest that MyD88-dependent signaling has a role in the initiation of necroptotic death in FADD-deficient DCs in vitro but is not essential in vivo. Commensal bacteria may still stimulate DC death through the TLR4 adaptor molecule TRIF, which has been previously shown to interact with RIP3 to initiate necroptosis (He et al., 2011).

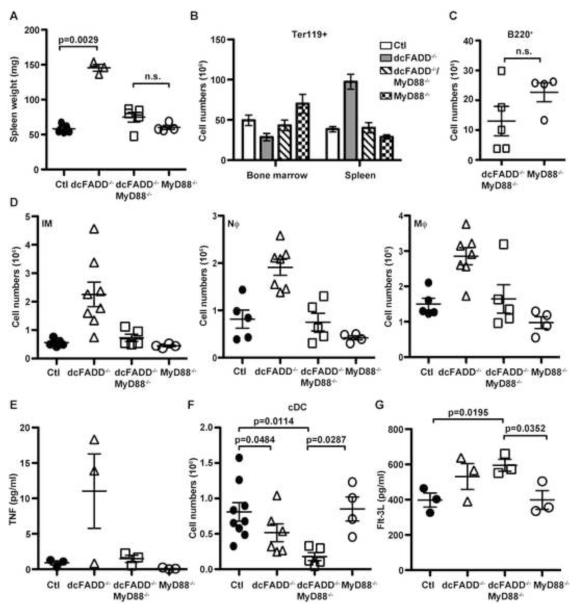

Figure 4. Deletion of MyD88 in DCs Does not Prevent Death but Partially Rescues dcFADD−/− Phenotypes.

(A) Spleen weights from control (Ctl), dcFADD−/−, dcFADD−/−dcMyD88−/−, or dcMyD88−/− mice. (B and C) Numbers of inflammatory monocytes, neutrophils (B, IM and Nϕ), and macrophages (C) in the spleen. (D) CD103+ DC numbers in the MLN. (E) BMDCs generated from control (white bars), dcFADD−/− (gray bars), dcFADD−/−dcMyD88−/− (diagonal bars), and dcMyD88−/− (hatched bars) mice were pre-treated with 30 μM Nec-1, or DMSO, then stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 16 h, and labeled with Annexin V and 7AAD to measure cell death (US = unstimulated). Bar graphs plotted as mean percentage of death ± SEM and are representative of 3 individual experiments. Scatter plots represents mean ± SEM (n.s. = not significant). Each point represents an individual animal and pooled from multiple analyses (A-D). See also Figure S5.

Since we observed a partial rescue of the systemic inflammation in dcFADD−/−dcMyD88−/− mice, we investigated whether MyD88 signaling was necessary in other cells types. Interactions between commensal bacteria and host cells rely on MyD88-dependent signals to elicit innate immune responses and to maintain intestinal homeostasis (Hooper et al., 2012). Therefore, to further examine the importance of MyD88 in the development of inflammation, we crossed dcFADD−/− mice to complete MyD88−/− knockout mice to generate dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− DKO mice. In these mice, MyD88 was deleted from all cell populations. These mice revealed a dramatically marked decrease in spleen size and weight, such that organ weights were similar to control mice (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the erythrocyte population in the spleen was reduced to wild-type numbers in the dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− DKO mice when compared to dcFADD−/− mice (Figure 5B). The B cell population in the DKO mice was also reduced and resembled the numbers observed in MyD88−/− controls (Figure 5C). Additionally, the myeloid cell populations (inflammatory monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages) in the dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− mice also returned to similar cell numbers as control mice (Figure 5D). Accordingly, the elevated levels of TNF in dcFADD−/− mice were lowered to wild-type amounts in dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− mice (Figure 5E). Similar to results with dcFADD−/−dcMyD88−/− mice, complete deletion of MyD88 did not rescue DC numbers (Figure 5F). The DCs in dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− DKO mice were significantly decreased compared to the numbers of DCs detected in control and MyD88−/− mice (Figure 5F). The diminished DC numbers in dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− DKO mice also correlated with elevated Flt-3L amounts (Figure 5G). These results demonstrate that MyD88 is not necessary for the reduction in the cDC population. In the absence of MyD88, DCs still die by necroptosis. However, MyD88 is required for the development of inflammation observed in dcFADD−/− mice. Thus, MyD88-dependent signaling in populations other than DCs is surprisingly crucial for the development of systemic inflammation in response to DC necroptosis.

Figure 5. MyD88-Dependent Signaling is Required for the Development of Inflammation in dcFADD−/− Mice.

(A) Weights of spleens from control (Ctl), dcFADD−/−, dcFADD−/−MyD88−/−, or MyD88−/− mice. (B) Ter119+ erythroid cells in the spleen and bone marrow (Ctl (white bars, n = 5); dcFADD−/− (gray bars, n = 3); dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− (diagonal bars, n = 5); MyD88−/− (hatched bars, n = 4)). (C and D) Absolute numbers of B220+ B cell (C), inflammatory monocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage (D, IM, Nϕ, and Mϕ, respectively) in the spleen. (E) TNF levels (pg/ml) in the serum were measured by ELISA. (F) Splenic DCs (CD11chiMHC II+) numbers were measured and plotted. (G) The levels of serum Flt-3L were measured by ELISA. Scatter plots represents mean ± SEM (n.s. = not significant). Each point represents an individual animal pooled from multiple analyses (A, C-G).

Systemic Inflammation in dcFADD−/− Mice is Abrogated by Antibiotic Treatment

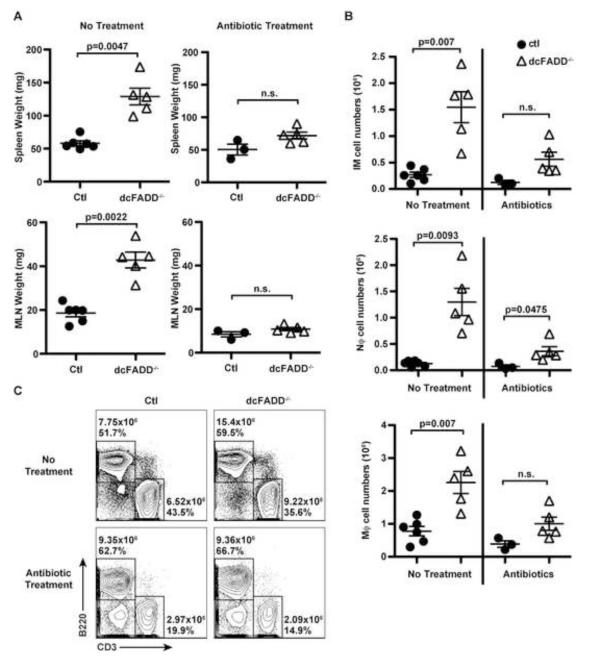

A potential explanation for the requirement of MyD88 in the development of inflammation is that the commensal microflora signals through MyD88-dependent pathways, which “primes” cells for DAMP-induced inflammation. The appreciable decrease of CD103+ migratory DCs in the GALT and the absence of systemic inflammation in dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− mice supported a role for commensal bacteria (Figure 1D and 5). To eliminate most of the commensal microflora, we treated 2-day old mice with a broad-spectrum of antibiotics for 4-5 weeks. Following antibiotic treatment, dcFADD−/− and control mice had similar sized spleens and MLNs (Figure 6A). Furthermore, antibiotic treatment reduced the number of inflammatory monocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, and B cells in dcFADD−/− mice (Figure 6B and 6C). Therefore, the systemic inflammation observed in untreated dcFADD−/− mice was rescued in antibiotic-treated animals. In support of the MyD88 data, results from the antibiotic treatments validate the contribution of intestinal microbiota to the systemic inflammation in dcFADD−/− mice. Thus, the signals generated from necroptotic DCs alone are insufficient to trigger the development of inflammation.

Figure 6. Treatment with Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics Rescues Systemic Inflammation in dcFADD−/− Mice.

(A-C) Mice were treated with a cocktail of antibiotics in the drinking water from day 2 of birth until the time of analysis (at 4-5 weeks of age). Spleen (upper panels) and MLN (lower panels) weights from non-treated (no treatment, left panels) and antibiotic-treated (right panels) mice were measured (A). (B) Absolute numbers of inflammatory monocytes (IM), neutrophils (Nϕ), and macrophages (Mϕ) in the spleen. (C) B220+ and CD3+ lymphocyte populations in the spleen of non-treated (upper panels) or antibiotic-treated (lower panels) mice were analyzed (Ctl mice, left panels; dcFADD−/− mice, right panels). Numbers represent total cell numbers and cell percentages. Scatter plots represents mean ± SEM, and each point represents an individual animal (n.s. = not significant). Data are representative of 3 separate experiments (A-C).

Discussion

The analysis of mice with FADD-deficient DCs has allowed us to investigate the importance of FADD in dendritic cell death, the effect of necroptotic death on the immune response, and the role of commensal bacteria on different immune cell populations. FADD-deficiency sensitized cells to necrotic death leading to decreased DCs in mice. In contrast to FADD-deficient T cells that are non-functional (Osborn et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011), FADD-deficient DCs were able to secrete cytokines and induced antigen-specific T cell responses. Additionally, dcFADD−/− mice had a heightened state of systemic inflammation, which was different from other tissue-specific FADD-deficient mice that exhibited localized inflammation (Bonnet et al., 2011; Welz et al., 2011). It is surprising that death of a proportion of dendritic cells in the GALT was capable of driving system-wide effects. Deletion of RIP3 in dcFADD−/− mice rescued DC death and also decreased systemic inflammation to normal levels, suggesting DC necroptosis is responsible for all the dcFADD−/− mouse phenotype. However, without assessing DC-specific RIP3-deficient mice, we cannot exclude the formal possibility of RIP3 deletion in other cell types playing a role as well. Blocking signals from commensal microbiota with MyD88-deficiency in all cell populations also abrogated systemic inflammation in dcFADD−/− mice. These experiments describe not only a role for FADD in preventing necroptosis in DCs, but also demonstrate a role for commensal bacteria in an inflammatory response against necroptotic cells, which presumably release inflammation-inducing molecules.

Necroptosis is a form of cell death initially described to be downstream of the death receptors requiring RIP1 and RIP3 interaction and their kinase activities (Cho et al., 2009; He et al., 2009). FADD-deficient DCs were more sensitive to cell death in response to TLR stimulation in vitro. In vivo, FADD-deficient DCs presumably died from stimulation by commensal microflora. We found that LPS-induced death of dcFADD−/− cells was only partially inhibited by Nec-1 but completely blocked in the absence of RIP3. Conversely, TNF-stimulated death was completely rescued by Nec-1 treatment. These data suggest that TLR4 can induce both a RIP1/RIP3-dependent death and a RIP3-dependent but RIP1-independent death. The RIP1/RIP3-dependent death can potentially be mediated by up-regulation of TNF by TLR signaling, in turn signaling through the TNF-RI to induce RIP1-dependent necroptosis. RIP1-independent and RIP3-dependent death may be initiated directly downstream of TLR4 as previously described by other groups (He et al., 2011; Upton et al., 2010, 2012). In FADD-deficient DCs, RIP3-dependent necroptosis is likely linked to the adaptor protein TRIF downstream of TLR4. TRIF is a known adaptor protein that can associate with TLR4 or TLR3, receptors for LPS and poly(I:C), respectively (Yamamoto et al., 2002). Indeed, dcFADD−/−dcMyD88−/− BMDCs still died when stimulated with LPS. In this case, FADD may serve as a negative inhibitor of the TRIF-RIP3 complex.

The absence of FADD in other cell types also caused marked sensitivity to necroptosis (Bonnet et al., 2011; Osborn et al., 2010; Welz et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). Similarly, caspase-8-deficiency exhibited the same sensitivity to RIP3-dependent programmed necrosis (Ch’en et al., 2011; Gunther et al., 2011; Kaiser et al., 2011; Oberst et al., 2011). Interestingly, during the writing of this manuscript, a report showed that LPS alone did not stimulate necroptotic death in caspase-8-deficient DCs (Casp8−) (Kang et al., 2012). This is in contrast to FADD-deficient DCs, which exhibit exacerbated death upon LPS stimulation. In addition, ATP release from dying cells likely stimulates IL-1β production by dcFADD−/− cells. Potassium treatment diminished IL-1β levels, implying a role for potassium efflux and the NLRP3 inflammasome (Petrilli et al., 2007). In addition, there are unique phenotypes in the dcFADD−/− mice not observed in Casp8− mice. For instance, fewer DC numbers were observed in dcFADD−/− mice while Casp8− mice exhibited unaltered or increased DC numbers. Increased macrophage and B cell populations with augmented TNF levels were observed in dcFADD−/− but not Casp8− mice. The difference in necroptosis execution in FADD and caspase-8 DC models highlights the critical role FADD plays in cell death. Caspase-8/RIP3 DKO mice suffered from T and B cell autoimmunity at an early age, marked by an increase of the signature CD3+B220+ population and elevated levels of ANA. Preliminary results indicate that six-week-old dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− mice also exhibited elevated number of CD3+B220+ double positive cells, but no anti-nuclear antibodies were detected (data not shown). It remains to be seen whether aged dcFADD−/−RIP3−/− will have an accumulation of cDCs and develop systemic autoimmunity.

Some phenotypes in dcFADD−/− mice, including the expansion of monocytes, neutrophils and erythrocytes in the spleen, as well as decreased red blood cells in the bone marrow, were similar to what was observed in mice lacking cDCs, also known as DC-less mice (Birnberg et al., 2008; Ohnmacht et al., 2009). Flt-3L had been shown to control homeostasis of DCs in the bone marrow and periphery (Hochweller et al., 2009; McKenna et al., 2000) and was thought to be the main culprit for the phenotype of DC-less mice. The receptor kinase Flt-3 is critical in DC development and is expressed on common myeloid progenitors and differentiated DCs (Karsunky et al., 2003; Waskow et al., 2008). In previous reports on DC-less mice, the increased Flt-3L levels compensating for the changes in cell homeostasis led to myeloproliferative disease and erythrocyte imbalance (Birnberg et al., 2008). The decreased DC numbers in the spleen and GALT were sufficient to induce a moderate increase in Flt-3L. The ability of Flt-3L to expand the progenitor population allows for the repopulation of DCs in the periphery (Hochweller et al., 2009; Karsunky et al., 2003; Waskow et al., 2008). Thus, elevated serum levels of Flt-3L in dcFADD−/− mice may continually differentiate progenitor cells into DCs, thereby dampening the reduction in splenic cDC numbers. However, in contrast to DC-less mice, dcFADD−/− mice also exhibited elevated levels of TNF and other cytokines as well as higher numbers of macrophages and B cells. Increased Flt-3L in the serum is not likely to be the main reason for increased myeloid and erythrocyte populations in dcFADD−/− mice. Consistent with this, serum levels of Flt-3L were elevated in dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− mice, but the inflammatory phenotype of dcFADD−/− mice were not exhibited.

The role of MyD88-dependent signals in the induction of inflammation was examined by crossing dcFADD−/− mice with MyD88−/− mice. The absence of MyD88 did not rescue the death of DCs in dcFADD−/− mice. However, the inflammatory phenotype in dcFADD−/− mice was completely absent in dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− mice. On the other hand, specific deletion of MyD88 in the DC population only partially rescued the phenotype exhibited by dcFADD−/− mice. In this case, TLR signaling was defective in only a small proportion of cells, while MyD88-dependent signals remained intact in other cell populations. Although MyD88-dependent signals were not necessary for DC death, these data suggested that signaling through MyD88 was required for most of the inflammatory phenotypes observed in dcFADD−/− mice. MyD88 is an essential adaptor for signaling through TLRs and IL-1/18 receptors (Barton and Medzhitov, 2003; Beutler and Rietschel, 2003). In previous reports, IL-1 signaling was responsible for the inflammation induced by necrotic cells, thus MyD88−/− mice failed to recruit neutrophils in response to dead cells (Rock et al., 2010). Stimulation of FADD-deficient cells produced increased amounts of IL-1β in vitro, which implies that IL-1β could contribute to the inflammation detected in dcFADD−/− mice. However, the levels of IL-1β were undetectable in dcFADD−/− mice. Therefore, IL-1β does not appear to play a significant role in the inflammation in dcFADD−/− mice, and the absence of inflammatory responses in the dcFADD−/−MyD88−/− mice is the outcome of defective TLR signaling.

TLR ligands from commensal microflora are likely the source of “tonic signals” which prime cells to respond to DAMPs. Closer examination of the migratory DCs from the gut revealed a greater decrease in this DC subset suggesting a role for intestinal microbiota. Administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics rescued the inflammatory phenotypes in dcFADD−/− mice. These data supported a role for MyD88-dependent signaling in the development of inflammation. Intestinal DCs constantly survey the gut microbiota in order to maintain intestinal homeostasis. At the same time, the intestinal microflora can influence immune responses by stimulating MyD88 signaling pathways in various cell populations (Hooper et al., 2012). For example, productive antiviral immune responses have been reported to depend on the presence of commensal bacteria (Abt et al., 2012; Ichinohe et al., 2011). One explanation for needing intestinal microflora in immunity is that gut commensals provide signals to prime immune cells for activation, and indeed macrophages isolated from antibiotic-treated mice are less responsive to viral stimulation (Abt et al., 2012). Therefore, a potential model for the dcFADD−/− mice may be that commensal microbiota provide MyD88-dependent signals that prime myeloid and B cells to respond to inflammatory stimuli. Activation of primed myeloid/B cells by necroptotic FADD-deficient DCs then elicits an inflammatory response. In the absence of commensal-generated signals, either by antibiotic treatment or by MyD88 deletion, stimulation from necroptotic DCs alone is not sufficient to induce inflammation. Thus, our studies uncover a critical relationship between commensal microbiota and the ability of innate immune cells and B cells to respond to necroptotic cells. In addition, we found that dysregulation of DC necroptosis at intestinal sites can drive systemic inflammation. More importantly, these data demonstrate that commensal microbiota are necessary for a functional immune system to respond to danger signals coming from pathogens or cellular stress.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

Mice were used at 6-12 weeks of age unless otherwise noted. Littermates or sex- and age-matched (within 10 days) mice were used as controls. dcFADD−/− mice were generated by crossing CD11c-Cre transgenic mice with FADDflox mice. Mice containing FADD alleles floxed with loxP sites were generated in the lab and backcrossed to C57BL/6 for at least 10 generations(Osborn et al., 2010). CD11c-Cre mice have been previously described (Caton et al., 2007). MyD88−/− mice (in C57BL/6 background) were provided by Dr. Shizuo Akira (Adachi et al., 1998) through Dr. Greg Barton, and RIP3−/− mice (back-crossed to C57BL/6 for >8 generations) were from Dr. Xiaodong Wang (He et al., 2009). MyD88flox mice (Hou et al., 2008) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. For antibiotic treatment, mice were fed a cocktail of 1 mg/ml ampicillin, 1 mg/ml neomycin, 0.5 mg/ml ciprofloxacin, and 0.5 mg/ml meropenem in the drinking water flavored with 20 mg/ml grape kool-aid from day 2 of birth. Following weaning, mice maintained on the same antibiotic cocktail except with 0.5 mg/ml vancomycin in place of ciprofloxacin until analysis (Welz et al., 2011). Mice treated with antibiotics were analyzed between 4-5 weeks of age. All experiments utilized co-housed mice. Experimental mice were housed in the animal facility at the University of California, Berkeley, and all procedures involving animals were approved by institutional animal care and use committee.

Dendritic Cell Enrichment

To isolate splenic dendritic cells (DCs), spleens were cut into small pieces, digested with collagenase IV (Gibco) at 37°C for 35 min, and then incubated with 25 mM EDTA for 5 min at room temperature before dissociating and filtering cells through a 100 μm strainer. CD11c+ DCs were enriched using CD11c magnetic particles (Miltenyi Biotec) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Bone marrow was flushed from femurs and tibias using a needle and syringe. RBCs were lysed, and 2 × 106 BM cells were cultured in 10 cm non-tissue culture-treated dishes in complete RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, L-glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin, sodium pyruvate, 2-mercaptoethanol, and GMCSF (collected supernatant from X63-GMCSF cell line (Zal et al., 1994), a generous gift of Dr. Brigitta Stockinger at National Institute for Medical Research, London through Dr. Tomasc Zal at Scripps). Cells were cultured for 8-10 days with fresh media added on days 3, 6 and 8. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were harvested and re-plated in complete RPMI with or without GMCSF for stimulation. Alternatively, CD11c+ BMDCs were purified with magnetic particles.

ELISA and Cytometric Bead Array

Blood was collected from tail vein or cardiac puncture, and different proteins in the serum were analyzed by sandwich ELISA. The levels of Flt3L (R&D Systems), TNFα and IL-1β (ebioscience) were determined using ELISA kits. Additionally, multiple cytokines were quantitated with the mouse inflammation cytometric bead array kit (BD Biosciences). Samples were collected on the LSR II and analyzed with FCAP Array Software (BD Biosciences).

Cell Death Induction

To examine cell death in dendritic cells, cells were pre-treated with 10 μM zVAD-FMK and/or 30 μM necrostatin-1 for 30 min and then stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS or 100 ng/ml recombinant TNFα at 37°C. Following 16-18 hrs of stimulation, BMDCs were harvested in cold PBS and surface stained with anti-CD11c and anti-CD11b in FACS buffer. Cells were then washed in Annexin V binding buffer and labeled with FITC-Annexin V and 7AAD. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was calculated using paired or unpaired Student’s T test. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare survival curves. Statistical analysis was completed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Mice with loss of FADD in dendritic cells (DCs) suffer from systemic inflammation

DCs in gut-associated lymphoid tissues of these mice are greatly reduced

Deletion of RIP3 or antibiotic treatment rescues systemic inflammation

Commensal microbiota are crucial for immunity against harmful stimuli

Acknowledgments

We thank S. He and Xiaodong Wang for the generous gift of RIP3−/− mice. M. Koch, H. Melichar, G. Barton and E. Robey for sharing mice, reagents and helpful discussions. We are grateful to A. Chuang and Y.F. Sun for technical help, Hector Nolla for support with flow cytometry. We thank J. Halkias, J. Coombes, and S. Nandu for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions. This work was funded by the NIH grants PO1 AI065831 (Project 2) and RO1 AI095299 (A.W.); and NIH training grants T32 CA009179-32 and T32 CA009041-35 (J.A.Y.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abt MC, Osborne LC, Monticelli LA, Doering TA, Alenghat T, Sonnenberg GF, Paley MA, Antenus M, Williams KL, Erikson J, et al. Commensal Bacteria Calibrate the Activation Threshold of Innate Antiviral Immunity. Immunity. 2012;37:158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Science. 2003;300:1524–1525. doi: 10.1126/science.1085536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B, Rietschel ET. Innate immune sensing and its roots: the story of endotoxin. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:169–176. doi: 10.1038/nri1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnberg T, Bar-On L, Sapoznikov A, Caton ML, Cervantes-Barragan L, Makia D, Krauthgamer R, Brenner O, Ludewig B, Brockschnieder D, et al. Lack of conventional dendritic cells is compatible with normal development and T cell homeostasis, but causes myeloid proliferative syndrome. Immunity. 2008;29:986–997. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet MC, Preukschat D, Welz PS, van Loo G, Ermolaeva MA, Bloch W, Haase I, Pasparakis M. The Adaptor Protein FADD Protects Epidermal Keratinocytes from Necroptosis In Vivo and Prevents Skin Inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:572–582. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caton ML, Smith-Raska MR, Reizis B. Notch-RBP-J signaling controls the homeostasis of CD8-dendritic cells in the spleen. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1653–1664. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch’en IL, Tsau JS, Molkentin JD, Komatsu M, Hedrick SM. Mechanisms of necroptosis in T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:633–641. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Wang YH, Wang Y, Huang L, Sandoval H, Liu YJ, Wang J. Dendritic cell apoptosis in the maintenance of immune tolerance. Science. 2006;311:1160–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1122545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M, Chan FK. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes JL, Powrie F. Dendritic cells in intestinal immune regulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:435–446. doi: 10.1038/nri2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degterev A, Hitomi J, Germscheid M, Ch’en IL, Korkina O, Teng X, Abbott D, Cuny GD, Yuan C, Wagner G, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:313–321. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Li Y, Jagtap P, Mizushima N, Cuny GD, Mitchison TJ, Moskowitz MA, Yuan J. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duprez L, Takahashi N, Van Hauwermeiren F, Vandendriessche B, Goossens V, Vanden Berghe T, Declercq W, Libert C, Cauwels A, Vandenabeele P. RIP Kinase-Dependent Necrosis Drives Lethal Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. Immunity. 2011;35:908–918. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther C, Martini E, Wittkopf N, Amann K, Weigmann B, Neumann H, Waldner MJ, Hedrick SM, Tenzer S, Neurath MF, et al. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-alpha-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature. 2011;477:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature10400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Liang Y, Shao F, Wang X. Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:20054–20059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116302108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Wang L, Miao L, Wang T, Du F, Zhao L, Wang X. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;137:1100–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochweller K, Miloud T, Striegler J, Naik S, Hammerling GJ, Garbi N. Homeostasis of dendritic cells in lymphoid organs is controlled by regulation of their precursors via a feedback loop. Blood. 2009;114:4411–4421. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-188045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336:1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou B, Reizis B, Defranco AL. Toll-like Receptors Activate Innate and Adaptive Immunity by using Dendritic Cell-Intrinsic and -Extrinsic Mechanisms. Immunity. 2008;29:272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinohe T, Pang IK, Kumamoto Y, Peaper DR, Ho JH, Murray TS, Iwasaki A. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:5354–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019378108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB, Livingston-Rosanoff D, Daley-Bauer LP, Hakem R, Caspary T, Mocarski ES. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;471:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature09857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang TB, Yang SH, Toth B, Kovalenko A, Wallach D. Immunity. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.015. Published online December 20, 2012. 2010.1016/j.immuni.2012.2009.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsunky H, Merad M, Cozzio A, Weissman IL, Manz MG. Flt3 ligand regulates dendritic cell development from Flt3+ lymphoid and myeloid-committed progenitors to Flt3+ dendritic cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:305–313. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono H, Rock KL. How dying cells alert the immune system to danger. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:279–289. doi: 10.1038/nri2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushwah R, Hu J. Dendritic cell apoptosis: regulation of tolerance versus immunity. J. Immunol. 2010;185:795–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabrouk I, Buart S, Hasmim M, Michiels C, Connault E, Opolon P, Chiocchia G, Levi-Strauss M, Chouaib S, Karray S. Prevention of autoimmunity and control of recall response to exogenous antigen by Fas death receptor ligand expression on T cells. Immunity. 2008;29:922–933. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna HJ, Stocking KL, Miller RE, Brasel K, De Smedt T, Maraskovsky E, Maliszewski CR, Lynch DH, Smith J, Pulendran B, et al. Mice lacking flt3 ligand have deficient hematopoiesis affecting hematopoietic progenitor cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells. Blood. 2000;95:3489–3497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moquin D, Chan FK. The molecular regulation of programmed necrotic cell injury. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, McCormick LL, Fitzgerald P, Pop C, Hakem R, Salvesen GS, Green DR. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature. 2011;471:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature09852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnmacht C, Pullner A, King SB, Drexler I, Meier S, Brocker T, Voehringer D. Constitutive ablation of dendritic cells breaks self-tolerance of CD4 T cells and results in spontaneous fatal autoimmunity. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:549–559. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn SL, Diehl GE, Han S-J, Xue L, Kurd N, Hsieh K, Cado D, Robey EA, Winoto A. Fas-associated death domain (FADD) is a negative regulator of T-cell receptor-mediated necroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:13034–13039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005997107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1583–1589. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock KL, Latz E, Ontiveros F, Kono H. The sterile inflammatory response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2010;28:321–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CL, Aumeunier AM, Mowat AM. Intestinal CD103+ dendritic cells: master regulators of tolerance? Trends Immunol. 2011;32:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K, Heath WR. The CD8+ dendritic cell subset. Immunol. Rev. 2010;234:18–31. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranges PB, Watson J, Cooper CJ, Choisy-Rossi CM, Stonebraker AC, Beighton RA, Hartig H, Sundberg JP, Servick S, Kaufmann G, et al. Elimination of antigen-presenting cells and autoreactive T cells by Fas contributes to prevention of autoimmunity. Immunity. 2007;26:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A, Jost PJ, Nagata S. The many roles of FAS receptor signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2009;30:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Lee J, Navas T, Baldwin DT, Stewart TA, Dixit VM. RIP3, a novel apoptosis-inducing kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:16871–16875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. Virus inhibition of RIP3-dependent necrosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waskow C, Liu K, Darrasse-Jeze G, Guermonprez P, Ginhoux F, Merad M, Shengelia T, Yao K, Nussenzweig M. The receptor tyrosine kinase Flt3 is required for dendritic cell development in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:676–683. doi: 10.1038/ni.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welz PS, Wullaert A, Vlantis K, Kondylis V, Fernandez-Majada V, Ermolaeva M, Kirsch P, Sterner-Kock A, van Loo G, Pasparakis M. FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2011;477:330–334. doi: 10.1038/nature10273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NS, Dixit V, Ashkenazi A. Death receptor signal transducers: nodes of coordination in immune signaling networks. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:348–355. doi: 10.1038/ni.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Sato S, Mori K, Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Takeda K, Akira S. Cutting edge: a novel Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adapter that preferentially activates the IFN-beta promoter in the Toll-like receptor signaling. J. Immunol. 2002;169:6668–6672. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh W-C, Pompa JL, McCurrach ME, Shu H-B, Elia AJ, Shahinian A, Ng M, Wakeham A, Khoo W, Mitchell K, et al. FADD: essential for embryo development and signaling from some, but not all, inducers of apoptosis. Science. 1998;279:1954–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zal T, Volkmann A, Stockinger B. Mechanisms of tolerance induction in major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted T cells specific for a blood-borne self-antigen. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:2089–2099. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhou X, McQuade T, Li J, Chan FK, Zhang J. Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in embryos and lymphocytes. Nature. 2011;471:373–376. doi: 10.1038/nature09878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Cado D, Chen A, Kabra NH, Winoto A. Fas-mediated apoptosis and activation-induced T-cell proliferation are defective in mice lacking FADD/Mort1. Nature. 1998;392:296–300. doi: 10.1038/32681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.