Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the morphological condylar changes following orthognathic surgery by using a rapid and reliable computational method on panoramic radiographs.

Methods:

Digital panoramic radiographs of 45 patients who underwent bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (alone or associated with a Le Fort I osteotomy) between 2007 and 2010 were analysed. Calculation of the area, perimeter and height of 90 condyles was performed by using a specific computational method. Measurements were taken before surgery (m1), 1 day after surgery (m2) and 1 year after surgery (m3). The evolution of each index was analysed using paired t-tests between measures before and 1 day after surgery (m1 − m2) and measures before and 1 year after surgery (m1 − m3). The changes in the condylar area, perimeter and height were examined using the Bland and Altman plotting method.

Results:

There were no statistically significant changes in the mean condylar area, perimeter or height between m1 and m2 or between m1 and m3. The Bland and Altman plots for each index showed that a very limited number of condyles increased or decreased in area, perimeter and/or height outside the boundaries of the measurement error. Given the impossibility for a condyle to increase in size, these results are considered to represent the limits of the computational method used.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrated that there were no significant morphological condylar changes at the 1-year follow-up following surgery and that the range of normality in condylar changes could be influenced by the methodology used.

Keywords: panoramic radiograph, condylar morphology, orthognathic surgery, computer-aided measurements

Introduction

Condylar morphological changes following orthognathic surgery and/or orthodontic treatments have been well documented.1,2 Thus far, two specific entities have been described: condylar remodelling and condylar resorption.1,2 Condylar remodelling represents by far the most common entity encountered and is characterized by the preservation of a stable ramus height.2–5 Although the exact physiopathological mechanism has not yet been fully elucidated, condylar remodelling has been classically related to an adaptive bony physiological process to the functional load imposed on the temporomandibular joints (TMJs).2–5 Condylar resorption is less commonly found and is associated with more severe clinical consequences than remodelling.2,6–8 Different authors have associated it empirically with a decrease of ramus height of >6–10%, leading to an anterior open bite and a mandibular clock-wise rotation.2,9,10 To date, no international consensus on the aetiology and the treatment of the condylar resorption has been reached, and this continues to be a source of debate. A detailed analysis of both entities has been extensively documented in the literature and is beyond the scope of this article. Although several methods for quantitative assessment of condylar morphology have been reported, there is still no unanimous standard technique. Most studies have been based on linear measurements limited to the condylar height and performed manually on lateral and/or panoramic radiographs. Several studies using three-dimensional imaging modalities, such as CT, cone-beam CT scan and MRI, have also recently been reported, showing results similar to those obtained by two-dimensional analysis.11–13 Ideally, the morphological changes of condyles should be detected and quantified using imaging modalities that are routinely taken for follow-up, such as panoramic and lateral radiographs. This would avoid the use of additional imaging modalities that potentially increase the cost and a patient’s radiation dose. For this reason, we previously proposed a new ad hoc fully digital method using digital panoramic radiographs—from the radiographical acquisition to the computer workstation—for assessing three measurements characterizing condylar morphology: condylar height, area and perimeter.14 This method has proven to be rapid and reliable with low measurement error.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate morphological condylar changes following orthognathic surgery by using our specific computational method.

Patients and methods

Study design

Digital panoramic radiographs of 45 patients who underwent bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (alone or associated with a Le Fort I osteotomy) at the Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève, Switzerland, between 2007 and 2010 were analysed. As a chart review, this study was granted exemption by the institution, and it was designed and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. Inclusion criteria were: (1) anteroposterior and/or vertical dentofacial deformity, (2) combined surgical/orthodontic approach, (3) Hunsuck–Epker-type bilateral mandibular split osteotomy (BSSO) together with manual condylar positioning and the placement of two bicortical positioning screws ostheosynthesis alone or associated with a Le Fort I osteotomy, (4) no post-operative maxillomandibular fixation, (5) no previous history of facial surgery and/or trauma, (6) no previous history of TMJ disorders and (7) clinical and radiological follow-up at 3, 6 and 12 months.

Image acquisition

All of the panoramic radiographs were taken with a digital panoramic radiographic system (Gendex Orthoralix® 9200; Gendex, Hatfield, PA; power supply 115–250 V AC ± 10%, frequency 50/60 Hz ± 2 Hz, maximum line power rating 10 A at 250 V, 20 A at 115 V, anode voltage 70–78 kV, in 2 kV steps, anode current 3–15 mA, in 1 mA steps, exposure time 12 s for standard pan, total cycle 24 s, focal spot 0.5 mm, distance spot sensor 505 mm, pixel size 48 μm, resolution 10.4 lp mm, image size 1536 × 2725 pixel, active area sensor 146 × 6 mm, 1.25× magnification, delivered dose 0.325 μGy s−1 at 70 kV 10 mA).

Computer image analysis

The Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine data were processed using OsiriX Imaging Software™ (v. 3.8.1, www.osirix-viewer.com; Geneva, Switzerland) running on a MacOS 10.5 (Apple Computer, Inc., Cupertino, CA, www.apple.com).

The details of the technique used for the condylar head height, perimeter and area calculation in the present series have been extensively described previously by Momjian et al.14

The measurements were made by the same investigator (AM) before surgery (m1), 1 day after surgery (m2) and 1 year after surgery (m3).

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation

Although some studies have argued that surgery may decrease the condylar height, their findings often reported decreases that were below what could be expected by chance owing to measurement error. In our previous study, we found measurement error values, based on the Dahlberg of 0.16 cm2 (approximately 5%) for area, 0.34 cm (approximately 5%) for perimeter and 0.04 cm (approximately 2%) for height.25 Thus, for instance, an individual could have a condylar area underestimated by 0.16 on the pre-surgery radiography and overestimated by 0.16 on the post-surgery radiography, leading to a difference of 0.32 owing only to measurement error. Note that these computations do not imply that individuals may not decrease below this threshold, but the mean decrease should not be greater than these values.

The sample size necessary to determine equivalence in area, perimeter and height with a power of 0.80 and an alpha of 0.5, assuming a mean of 2.9 (7.4 for perimeter and 2.4 for height) and a standard deviation of 1 (1.5 for perimeter and 0.6 for height), with a maximum permitted difference of twice the measurement error (i.e. 0.32 for area, 0.68 for perimeter and 0.08 for height) is 121 (61 for perimeter and 696 for height). Thus, our sample size was large enough to detect statistically meaningful equivalence for mean perimeter but not for area and height.

The mean values of each parameter were analysed using paired t-tests between measures before and 1 day after surgery (m1 − m2) and measures before and 1 year after surgery (m1 − m3).

The individual changes in condylar area, perimeter and height were examined using the Bland–Altman plotting method, which indicates the smallest detectable difference (i.e. the amount of detectable change above the random measurement error). The use of the Bland and Altman plots technique resulted in three advantages. First, all data, and not only summary measures, are visually represented. This allows readers to determine for themselves the pattern in the data. In particular, readers can see that some condyles seem to increase in size. Second, the impact of surgery could be more important for larger condylar sizes (in terms of area, perimeter or height), and these plots allow evaluation of this hypothesis. Third, the limits of agreement provide a clear threshold for random changes in condylar area/perimeter/height. Thus, individuals with a larger decrease are clearly visible. The 95% limits of agreement were calculated by the Bland and Altman method defined by the mean of the difference between the two measures ±1.96 standard deviation of this difference, providing a clear threshold for random change in condylar indices.15

Results

Of the 45 patients (43 Caucasians and 2 Africans), 28 underwent a BSSO associated with a Le Fort I osteotomy and 17 underwent an isolated BSSO for mandibular advancement. The mean age of the patients at the time of surgery was 29.8 years (range 17–55 years) and 23 patients were female.

None of the patients presented a clinical occlusal relapse nor developed signs and/or symptoms of TMJ dysfunction.

Test–retest precision of the parameters

Based on mean data, condylar area, perimeter and height remained stable either just after or 1 year after surgery (p > 0.01; Table 1). The changes in the three parameters analysed were all similar across age, sex and type of surgery.

Table 1.

Evolution of mean (standard deviation) condylar area, perimeter and height in patients undergoing surgery

| Indices | Before (m1) | After (m2) | p (m1 − m2) | 1-year follow-up (m3) | p (m1 − m3) |

| Area (cm2) | 2.89 (1.05) | 2.96 (1.01) | 0.66 | 2.96 (1.00) | 0.68 |

| Perimeter (cm) | 7.44 (1.52) | 7.51 (1.44) | 0.74 | 7.47 (1.40) | 0.87 |

| Height (cm) | 2.34 (0.56) | 2.37 (0.54) | 0.73 | 2.38 (0.56) | 0.62 |

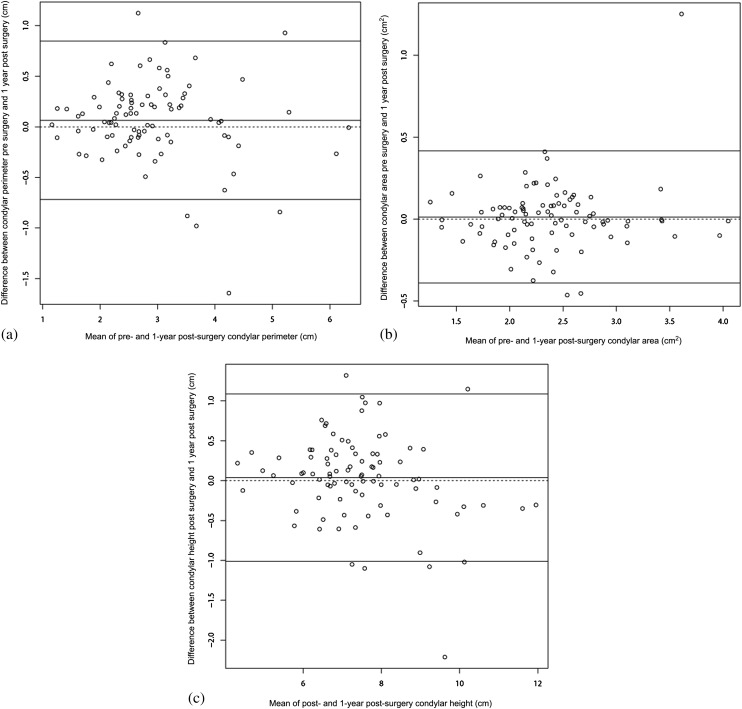

The Bland and Altman plots for each index showed that approximately the same number of individual condyles increased or decreased in area, perimeter and height (Figure 1). Moreover, based on measurement error estimation, the decreases were not more frequent when area, perimeter and height were particularly high, contrary to what one might expect. Thus, given the impossibility for a condyle to increase in size, these results have been considered to represent the limits of the computational method used.

Figure 1.

Bland and Altman figures of difference in condylar area (a), height (b), and perimeter (c) before and 1 year after surgery as a function of mean condylar area, height and perimeter over the two measures. Lines indicate the limits of agreement, so that variation within these lines is probably because of the measurement error

Discussion

Our results showed no significant morphological alterations of the mean values for condylar area, perimeter and height at 1-year follow-up. This outcome could be explained both by the surgical technique and/or by the methodology used. Unfortunately, the comparison of our findings with analogous data in the literature was purely conjectural, given the absence of studies that reported on the same procedure presented here. Concerning the surgical technique, it has been demonstrated that the use of rigid internal fixation with no postoperative maxillomandibular fixation results in a lower rate of condylar changes, compared with the semi-rigid fixation with intraosseous wires.1,2,16 Moreover, studies have reported similar results irrespective of the rigid technique used—either miniplates or positional screws in BSSO.2 Unfortunately, more specific details such as the type of osteotomy (e.g. Hunsuck–Epker, Obwegeser, vertical transoral osteotomy), the number of positional screws, the possible association of positional screws and miniplates, the method of condylar repositioning and the eventual use of post-operative traction elastics (strength and duration)—all factors that could potentially influence the condylar changes—were incomplete or lacking most of the time.

Regarding the methodology, the use of the computational measurement's technique and statistics could have resulted in two limitations, which may have influenced the range of “normality” in condylar changes. One limitation concerned the error variance of the measurements related to potential sources of bias owing to the radiographic procedure. Unfortunately, this limitation could not be overcome given that it was not possible to obtain exactly the same positioning of the patient's head for every radiograph taken at different times, the same positioning of the condyle within the glenoid fossa and the same orientation of the X-rays with the same magnification and distortion of the anatomical structures. This limitation in the methodology is common to all radiological studies that evaluate measurements irrespective of the examination used (e.g. conventional X-ray, CT scan, MRI).

Nevertheless, as previously demonstrated, our computational measurement's technique remains precise, and the same investigator performed all the measurements.14 We consider this as a strength, given that the goal of the present study was to perform specific measurements and having a single observer limited interobserver bias. It was also more representative of clinical reality since the same person usually makes the measurements on the pre- and post-operative radiograph. Nevertheless, it is also true that having a single observer did not allow an estimation of interobserver reliability.

The second limitation related to statistics. The Bland and Altman plotting method provided a quick and simple interpretation of the results with regard to the measurement error estimation.15 Nevertheless, it resulted in apparent increases in condylar area, perimeter or height, which obviously could not have occurred. We must also account for the negative values outside the boundaries of agreement fixed by the measurement error that were obtained. These positive and negative values in condylar area, perimeter or height could only be explained by the impossibility of the statistics to adjust for the margin of error related to the potential sources of bias (e.g. head positioning, image distortion, magnification and superposition of different anatomical structures). These two methodological limitations resulted in an estimated range of “normality” in condylar changes that could be different from the real morphological changes. According to the literature, the particular problem of the limit of the measurement's method has never been addressed.17–26 For this reason, one might reasonably ask if the occurrence of condylar resorption simply has been overestimated owing to the statistical limit of the methodology used. Moreover, the majority of studies on the specific topic of condylar resorption vs remodelling used the cutoff value of 6%, as described by Habets et al.27,28 This value is misleading, given that it was extrapolated from a study based on an experimental model that has never been validated clearly by clinical studies. Nevertheless, this value has been used routinely as the reference above which one should consider the diagnosis of condylar resorption.

The foremost critique of the present study is that we analysed both BSSO alone or associated with a Le Fort I osteotomy. Although this could be considered a deficiency, the sample of patients for both categories of monomaxillary vs bimaxillary osteotomies was too small to be appropriately powered; yet, there were no differences between the two groups.

In conclusion, the current study has demonstrated that there were no significant morphological condylar changes on digital panoramic radiographs 1 year after orthognathic surgery. The statistical method used has highlighted a limited number of positive or negative changes outside the boundaries of the measurement error fixed by our previous study that have been considered to represent the limits of the computational method used to assess condylar morphology.

References

- 1.De Clercq CA, Neyt LF, Mommaerts MY, Abeloos JV, De Mot BM. Condylar resorption in orthognathic surgery: a retrospective study. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg 1994; 9: 233–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoppenreijs TJ, Freihofer HP, Stoelinga PJ, Tuinzing DB, van’t Hof MA. Condylar remodelling and resorption after Le Fort I and bimaxillary osteotomies in patients with anterior open bite. A clinical and radiological study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 27: 81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mongini F. Condylar remodeling after occlusal therapy. J Prosthet Dent 1980; 43: 568–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckerdal O, Sund G, Astrand P. Skeletal remodelling in the temporomandibular joint after oblique sliding osteotomy of the mandibular rami. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1986; 15: 233–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller RI, McDonald DK. Remodeling of bilateral condylar fractures in a child. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1986; 44: 1008–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnett GW, Tamborello JA. Progressive class II development: female idiopathic condylar resorption. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 1990; 2: 699–716 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnett GW, Milam SB, Gottesman L. Progressive mandibular retrusion—idiopathic condylar resorption. Part I. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996; 110: 8–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnett GW, Milam SB, Gottesman L. Progressive mandibular retrusion—idiopathic condylar resorption. Part II. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996; 110: 117–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katsumata A, Nojiri M, Fujishita M, Ariji Y, Ariji E, Langlais RP. Condylar head remodeling following mandibular setback osteotomy for prognathism: a comparative study of different imaging modalities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006; 101: 505–514 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YI, Cho BH, Jung YH, Son WS, Park SB. Cone-beam computerized tomography evaluation of condylar changes and stability following two-jaw surgery: Le Fort I osteotomy and mandibular setback surgery with rigid fixation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 111: 681–687 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SB, Yang YM, Kim YI, Cho BH, Jung YH, Hwang DS. Effect of bimaxillary surgery on adaptive condylar head remodeling: metric analysis and image interpretation using cone-beam computed tomography volume superimposition. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 70: 1951–1959 10.1016/j.joms.2011.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore K, Gooris P, Stoelinga P. The contributing role of condylar resorption to skeletal relapse following mandibular advancement surgery: report of five cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991; 49: 448–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutbirth M, Van Sickels JE, Thrash WJ. Condylar resorption after bicortical screw fixation of mandibular advancement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 56: 178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Momjian A, Courvoisier D, Kiliaridis S, Scolozzi P. Reliability of computational measurement of the condyles on digital panoramic radiographs. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2011, 40: 444–450 10.1259/dmfr/83507370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986; 327: 307–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouwman JP, Kerstens HC, Tuinzing DB. Condylar resorption in orthognathic surgery. The role of intermaxillary fixation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994; 78: 138–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerstens HC, Tuinzing DB, Golding RP, van der Kwast WA. Condylar atrophy and osteoarthrosis after bimaxillary surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1990; 69: 274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Mol van Otterloo JJ, Dorenbos J, Tuinzing DB, van der Kwast WA. TMJ performance and behaviour in patients more than 6 years after Le Fort I osteotomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993; 31: 83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford JG, Stoelinga PJ, Blijdorp PA, Brouns JJ. Stability after reoperation for progressive condylar resorption after orthognathic surgery: report of seven cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994; 52: 460–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merkx MA, Van Damme PA. Condylar resorption after orthognathic surgery. Evaluation of treatment in 8 patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1994; 22: 53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheerlinck JP, Stoelinga PJ, Blijdorp PA, Brouns JJ, Nijs ML. Sagittal split advancement osteotomies stabilized with miniplates. A 2 to 5-year follow-up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994; 23: 127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang SJ, Haers PE, Zimmermann A, Oechslin C, Seifert B, Sailer HF. Surgical risk factors for condylar resorption after orthognathic surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000; 89: 542–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vidra MA, Rozema FR, Kostense PJ, Tuinzing DB. Observer consistency in radiographic assessment of condylar resorption. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002; 93: 399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolford LM, Reiche-Fischel O, Mehra P. Changes in temporomandibular joint dysfunction after orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 61: 655–660 10.1053/joms.2003.50131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang SJ, Haers PE, Seifert B, Sailer HF. Non-surgical risk factors for condylar resorption after orthognathic surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2004; 32: 103–111 10.1016/j.jcms.2003.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borstlap WA, Stoelinga PJ, Hoppenreijs TJ, van’t Hof MA. Stabilisation of sagittal split advancement osteotomies with miniplates: a prospective, multicentre study with two-year follow-up. Part III—condylar remodelling and resorption. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 33: 649–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habets LL, Bezuur JN, van Ooij CP, Hansson TL. The orthopantomogram, an aid in diagnosis of temporomandibular joint problems. I. The factor of vertical magnification. J Oral Rehabil 1987; 14: 475–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habets LL, Bezuur JN, Naeiji M, Hansson TL. The orthopantomogram, an aid in diagnosis of temporomandibular joint problems. II. The vertical symmetry. J Oral Rehabil 1988; 15: 465–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]