Abstract

Folding of newly synthesized polypeptides (NSPs) into functional proteins is a highly regulated process. Rigorous quality control ensures that NSPs attain their native fold during or shortly after completion of translation. Nonetheless, signaling pathways that govern the degradation of NSPs in mammals remain elusive. We demonstrate that the stress-induced c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) is recruited to ribosomes by the receptor for activated protein C kinase 1 (RACK1). RACK1 is an integral component of the 40S ribosome and an adaptor for protein kinases. Ribosome-associated JNK phosphorylates the eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1A isoform 2 (eEF1A2) on serines 205 and 358 to promote degradation of NSPs by the proteasome. These findings establish a role for a RACK1/JNK/eEF1A2 complex in the quality control of NSPs in response to stress.

INTRODUCTION

Folding of nascent polypeptides is essential for optimal protein function (1, 2). Nascent polypeptides that emerge from the ribosome have surface-exposed hydrophobic domains that can interact nonspecifically with other nascent polypeptides or a multitude of proteins present in the cytosolic environment (3, 4). A complex chaperone system facilitates the optimal folding of nascent polypeptides while preventing protein aggregation, which abrogates cell function (5–7). Although some of the components of the mammalian chaperone system have been identified, their detailed organization and function remain largely unknown. The nascent-polypeptide-associated complex (NAC) is a ribosome-coupled heterodimeric complex that binds short nascent chains, thereby shielding them from inappropriate interactions (8). As the nascent chains grow longer, NAC binding can be outcompeted by other ribosome-associated factors, including the eukaryotic elongation factor 1A (eEF1A) (9). eEF1A recruits aminoacylated tRNA to the ribosome during elongation and is thus well positioned to coordinate mRNA translation with quality control of nascent polypeptide folding. Indeed, this function of eEF1A has been suggested in several organisms (10, 11).

Misfolded nascent polypeptides are targeted for degradation by ribosome-associated ubiquitin ligases, thus avoiding the accumulation of damaged proteins and protein aggregation (12, 13). A sizable number of newly synthesized polypeptides (NSPs) are incorrectly folded (i.e., defective ribosomal products [DRiPs] in yeast) and undergo ubiquitin-dependent cotranslational degradation (14, 15). Multimeric complexes containing the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 (eIF3) and proteasomal components have been suggested to regulate degradation of NSPs in yeast (16). However, the mechanism underlying regulation of the stability of NSPs in mammals remains uncharacterized.

Stress-activated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) is a key component in cellular stress response, implicated in the control of cell survival through the spatial and temporal phosphorylation of its cytosolic and nuclear substrates (17, 18). Our earlier studies have demonstrated that JNK is a cotranslational regulator of the stability of the tumor suppressor protein p53 (19). In addition, a recent study pointed to the possibility that JNK has a broader impact on the stability of NSPs (20). Herein, we show that RACK1, which serves as a docking site for kinases on the ribosome (21), recruits JNK to polysomes. Polysome-associated JNK mediates the phosphorylation of eEF1A2 on Ser205 and Ser358, which increases the association of eEF1A2 with NSPs and their degradation by the proteasome. These data establish the existence of a stress-induced quality control mechanism for NSPs in mammals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and antibodies.

HEK293T and HEK293E cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 μg of penicillin and streptomycin/ml (all from Gibco). Where indicated, the cells were treated with 50 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Calbiochem) or exposed to UV irradiation for 90 s using a standard cell culture UV lamp or for 5 min using Stratalinker2400 (254 nm; 100 J/m2; Stratagene). Anti-eEF1A (recognizing both eEF1A1 and eEF1A2), anti-stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK)/JNK, anti-phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr15), and anti-Myc-tag polyclonal antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. Monoclonal antibodies anti-Myc (9E10), anti-Rpn2, and anti-rpS6 were from Santa Cruz; anti-eIF4E and anti-RACK1 from BD Transduction Laboratories; and anti-β-actin and anti-FLAG were from Sigma-Aldrich. Polyclonal mouse anti-eEF1A2 and polyclonal rabbit anti-eEF1A1 were from Abnova. Polyclonal rabbit anti-JNK antibody that was used in coimmunoprecipitation experiments was obtained from Santa Cruz. Antibodies against S358 of eEF1A2 were generated and affinity-purified using corresponding phosphopeptide (Phosphosolution).

Constructs, lentiviral shRNA, RNA interference, and transfection.

The 6×His-tagged ubiquitin, pEF-FLAG JNK2 WT and pEF-FLAG JNK2Thr183Ala/Tyr185Phe, pcDNA4/Myc-RACK1 and Myc-RACK1R38D/K40E constructs were previously described (19, 22, 23). Human pGEX-6-P1/GST-eEF1A1 and pGEX-1/GST-eEF1A2 were a generous gift from Zhao-Qing Luo (Purdue University, Department of Biological Sciences) and Charlotte R. Knudsen (University of Aarhus, Department of Molecular Biology), respectively. Human eEF1A2 was inserted into a pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen) containing an N-terminal FLAG tag using EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites by conventional cloning techniques. Transfection of HEK293T cells was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. shEEF1A2 (sense, 5′-gatccGTGCCCGTTTTACCAATAAttcaagagaTTATTGGTAAAACGGGCACtttttg-3′; antisense, 5′-aattcaaaaaGTGCCCGTTTTACCAATAAtctcttgaaTTATTGGTAAAACGGGCACg-3′) and Scrambled (sense, 5′-gatccACTCCTATCGTTCCGCTTAttcaagagaTAAGCGGAACGATAGGAGTtttttg-3′; antisense, 5′-aattcaaaaaACTCCTATCGTTCCGCTTAtctcttgaaTAAGCGGAACGATAGGAGTg-3′) (uppercase, duplex sequences that form the mature small interfering RNA [siRNA], once the short hairpin RNA [shRNA] has been processed; lowercase, loop sequences) were inserted into a pGreenPuro vector. The 293TN producer cell line was transfected with shRNA construct and the pPACKH1 packaging plasmid mix (System Biosciences) using Lipofectamine 2000. shJNK2 lentiviral vector (TRCN0000001012) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. The amphotropic phoenix packaging cell line was transfected with lentiviral shRNA constructs using Lipofectamine 2000. Supernatants were collected 48 and 72 h posttransfection, filtered using a 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filter and applied to HEK293E cells. HEK293T cells were cultured in 100-mm dishes and transfected with 5 μg of pcDNA4/Myc-RACK1 or Myc-RACK1R38D/K40E. These constructs do not contain a 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR). After 24 h, the cells were transfected with DsiRNA duplex (10 nM) targeting the 3′UTR of human RACK1 (IDT; HSC.RNAI.N005806.12.1). As a control, cells were transfected with siRNA control oligonucleotide (10 nM; Dharmacon). Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000, and cells were analyzed 72 h after delivery of DsiRNA.

[35S]methionine-cysteine pulse-chase.

HEK293T cells were grown in DMEM without methionine and cysteine and supplemented with 10% dialyzed serum (both from Gibco) for 2 h. Subconfluent cells were then labeled in the presence of 50 nM PMA with a 10-μCi/ml mixture of [35S]methionine-cysteine (Amersham) for 10 min (0 h time point), washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then chased in six volumes of DMEM plus 50 nM PMA for the indicated periods. For UV treatment, cells were first labeled for 10 min with [35S]methionine-cysteine mixture, washed three times with PBS, and placed under a regular tissue culture UV lamp hood for 90 s. For JNK-Inhibitor VII, TAT-TI-JIP153-163 (Calbiochem) treatment, cells were incubated overnight with 10 μM JNK-Inhibitor VII. The assay was then performed in the presence of 10 μM JNK-Inhibitor VII for the indicated times. Cell lysis was performed as previously described (24), and 10 μl of supernatant was precipitated by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) on a filter paper. Filter papers were soaked in scintillation fluid, and radioactivity was measured using a β-scintillation counter.

His-ubiquitin pulldown of 35S-labeled polypeptides.

Transfection of the His-ubiquitin construct was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's procedure. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were labeled with a 10-μCi/ml mixture of [35S]methionine-cysteine in DMEM without methionine and cysteine and supplemented with 10% dialyzed serum (both from Gibco) for 30 min. His pulldown was performed as previously described (25). Autoradiograms were obtained by exposing dried gels to X-ray film for 16 h.

Polysomal fractionation and immunoprecipitations.

HEK293T cells were cultured in 150-mm plates and transfected with the indicated constructs for 48 h using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). ∼70% confluent cells were treated with 50 nM PMA (Calbiochem) for 30 min alone or in combination with 100 μg of puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich)/ml where indicated, washed twice with cold PBS, and lysed in hypotonic lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM KCl, 100 μg of cycloheximide/ml, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5% Triton X-100, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate. For experiments in which we studied elongation rates (see Fig. 8E), cycloheximide was omitted throughout preparation of polysomes. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C) and layered onto a 10 to 50% sucrose gradient. Gradients were spun using a SW40 rotor (Beckman) at 36,000 rpm for 2 h at 4°C. Then, 500-μl fractions were collected by upward displacement with 60% sucrose, and the absorbance at 254 nm was continuously recorded using ISCO fractionator (Teledyne; ISCO). Fractions were precipitated with 10% TCA according to standard protocols, separated using SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blotting.

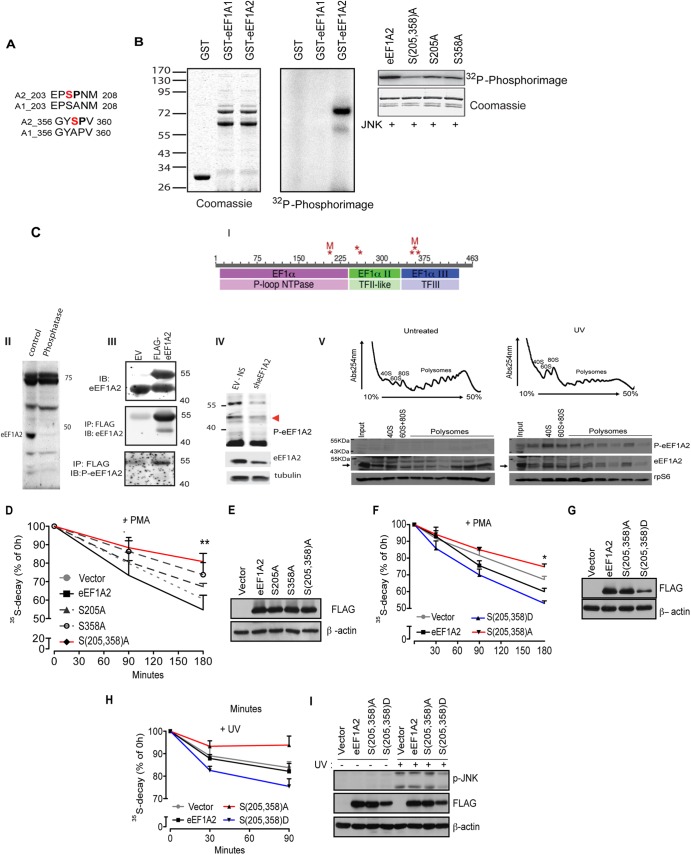

Fig 8.

JNK phosphorylates eEF1A2 at serines 205 and 358 to stimulate the degradation of NSPs (A) Pairwise alignment of regions of human eEF1A isoforms 2 (A2) and 1 (A1) surrounding the putative JNK phosphoacceptor sites (shown in red). (B) In vitro JNK kinase assay. The left panel shows the loading control (Coomassie blue staining) of in vitro phosphorylation assay performed with recombinant bacterially purified active JNK2α2 (30 ng) and glutathione S-transferase (GST)–eEF1A1 or GST-EF1A2 (1 μg each) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. In the middle panel, a 32P-autoradiogram shows that JNK2 preferentially phosphorylates eEF1A2. The right panel shows the results of an in vitro phosphorylation assay using JNK2 and wild-type GST-eEF1A2 or GST-eEF1A2 with alanine substitutions at Ser205 and Ser358 S(205,358)A, Ser205 (S205A), or Ser358 (S358A). After in vitro kinase reactions, eEF1A2 phosphorylation was visualized and quantified using phosphorimager (Fujifilm FLA-5100). Coomassie blue staining was performed to verify accurately equal amounts of all recombinant proteins. (C) Detection of eEF1A2 phosphorylation in cells. (i) Schematic diagram of phosphorylation sites identified on eEF1A2 by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). Phosphorylation sites (S205, Y254, T261, S354, Y357 or S358, and T365) are indicated by asterisk. Sites mutated in the present study (S205, S358) are indicated by “M.” The three domains in eEF1A2 are indicated in the bars with the darker colors, and protein superfamilies to which these domains belong are indicated in the lighter-colored bars below. Phosphorylation site identification was made on each of the three domains, with two clusters of two or three adjacent sites. (II) Protein extracts prepared from hippocampus were subjected to mock (control) or treatment with protein phosphatases (phosphatase) following immunoblot analysis with antibodies to p-eEF1A2. (III) 293T cells were transfected with empty vector (EV) or FLAG-eEF1A2 and proteins were analyzed by Western blotting (lysates; upper panel) or after their immunoprecipitation with FLAG antibodies following immunoblotting with antibodies to eEF1A2 (middle panel) or with antibodies raised against the S358 phosphopeptide (p-eEF1A2) (lower panel). (IV) 293T cells were subjected to control KD (EV-NS) or KD with sh-eEF1A2. Proteins were analyzed by IB with p-eEF1A2 (upper panel) or total eEF1A2 antibodies (middle panel) or control loading tubulin (lower panel). (V) UV stimulates recruitment of phosphorylated eEF1A2 to polysomes. HEK293T cells were left untreated or UV irradiated for 1 min and harvested after 30 min. A total of 10 OD260 units of the corresponding cytoplasmic extracts were sedimented by centrifugation on 10 to 50% sucrose gradients. Polysome profiles were obtained by continuous monitoring of UV absorbance at 254 nm. 40S, 60S, and 80S indicate the positioning of respective ribosomal subunits and monosome on the gradient. The distribution of phosphorylated eEF1A2 was monitored across the gradient using a p-eEF1A2 and is detected on polysomes upon UV irradiation. Ribosomal protein rpS6 and total eEF1A2 were used as loading control. (D and E) HEK293T cells were transfected with an empty vector, FLAG-eEF1A2 (eEF1A2), FLAG-eEF1A2S205A (S205A), FLAG-eEF1A2S358A (S358A), or FLAG-eEF1A2S205A/S358A [S(205,358)A] and treated with 50 nM PMA for the indicated time points. The stability of NSPs was monitored by a [35S]Met-Cys pulse-chase. The effects of a double mutant [S(205,358)A] on degradation of NSPs were significantly lower than those observed for single mutants (S205A and S358A) or WT eEF1A2 (ANOVA, F4,29 = 4.802, P = 0.0052). The data are represented as mean values ± the SEM (n = 3). (F, G, H, and I) HEK293T cells transfected with an empty vector, FLAG-eEF1A2 (eEF1A2), FLAG-eEF1A2S205A/S358A [S(205,358)A], or FLAG-eEF1A2S205D/S358D [S(205,358)D] mutant were treated with PMA for the indicated time points (F and G) or exposed to UV for 90 s (see Materials and Methods) (H and I). Stability of NSPs was monitored by a [35S]Met-Cys pulse-chase at the indicated time points (+PMA [F], 30, 90, and 180 min; +UV [H], 30 and 90 min). The data are represented as mean values ± the SEM (n = 3). The stability of 35S-labeled polypeptides was significantly decreased in cells expressing S(205,358)D mutant compared to control cells and cells expressing S(205,358)A mutant [+PMA, (F), P = 0.0032, S(205,358)A compared to FLAG-S(205,358)D (180 min), ANOVA, F3,15 = 55.67, P < 0.0001; +UV (H), P = 0.050, S(205,358)A compared to vector (90 min), ANOVA, F3,32 = 4.56, P = 0.0090]. (G and I) Protein extracts (30 μg) were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, and the levels of FLAG-eEF1A2 variants and JNK phosphorylation (I) were monitored by Western blotting. β-Actin served as a loading control.

In cytosolic-ribosomal fractionation experiments, hydrosoluble fractions (i.e., ribosome-free fractions localized on the top of the gradient) and fractions containing polysomes were pooled and used as cytosolic and ribosomal fractions, respectively.

For immunoprecipitations, polysomal extracts were obtained by pooling the fractions corresponding to polysomes and diluting them with 5 volumes of NET-2 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40, 1× Complete protease inhibitor [Roche]). Immunoprecipitations were carried out as previously described (19). In brief, extracts were precleared with protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham) and incubated with protein A-Sepharose beads preincubated with an anti-JNK, anti-Myc-tag antibody (both from cell Signaling) or isotype-matched IgGs (Calbiochem) for 4 h using end-to-end rotation at 4°C. After incubation, the beads were washed six times in NET-2 buffer. Immunoprecipitated material was eluted using nonreducing sample buffer (Pierce) and analyzed by Western blotting.

In Fig. 1E, immunoprecipitation reactions were carried out in the presence of RNase inhibitor (40 U of RNAsin [Invitrogen]/ml). Immunoprecipitates were washed once in NET-2 buffer, incubated in NET-2 buffer supplemented with 50 mM EDTA for 10 min at 4°C, and washed four additional times in NET-2. Immunoprecipitates were split in half, whereby RNA was isolated from one-half by TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, whereas the other half was analyzed by Western blotting.

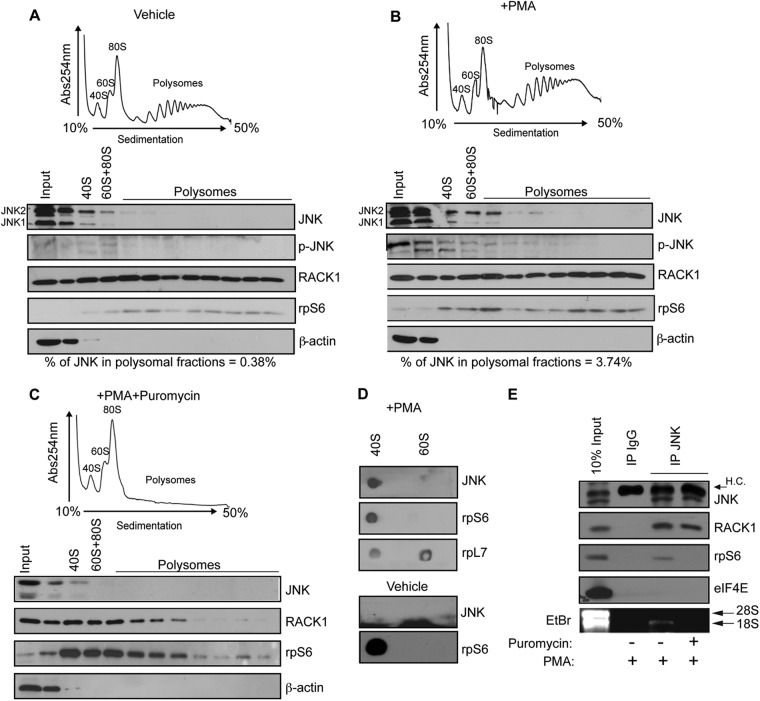

Fig 1.

PMA stimulates binding of JNK to polysomes. (A, B, and C) HEK293T cells were treated with a vehicle (0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) (A), 50 nM PMA (B), or 50 nM PMA in combination with 100 μg of puromycin/ml (C) for 30 min. The corresponding cytoplasmic extracts were sedimented by centrifugation on 10 to 50% sucrose gradients. Polysome profiles were obtained by continuous monitoring of UV absorbance at 254 nm (see Materials and Methods). 40S, 60S, and 80S indicate the positions of the respective ribosomal subunits and the monosome on the gradient. Distributions of JNK and phosphorylated JNK across the gradient were monitored by Western blotting. Ribosomal protein rpS6 was used as a loading control, whereas β-actin served as a cytoplasmic marker. (D) HEK293T cells were treated with 50 nM PMA for 30 min to activate JNK. Association of with 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits was monitored by in vitro filter-binding assay (see Materials and Methods), followed by Western blotting with an anti-JNK antibody. rpS6 and rpL7 were used as markers for 40S and 60S ribosomal subunit, respectively. (E) HEK293T cells treated with PMA (50 nM) or PMA in combination with puromycin (50 nM PMA plus 100 μg of puromycin/ml) for 30 min were immunoprecipitated with an anti-JNK antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies or incubated with EDTA to dissociate the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits, upon which RNA was isolated and analyzed by ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining. Isotype-matched IgG was used as a control. H.C., IgG heavy chains.

In Fig. 1A to C, the percentage of polysome-associated JNK (JNKP%) was calculated using the following equation: JNKP% = 100 × Σ{(OD[JNKPF]/OD[rpS6PF])/(OD[JNKInput]/OD[β-actinInput])}, with the subscript “PF” referring to each of the light polysomal fractions in which JNK was detected and where “OD” refers to the optical density. In Fig. 5A and B, percentage of polysome-associated FLAG-JNK (JNKP%) was calculated using JNKP% = 100 × Σ{(OD[FLAG-JNKPF]/OD[rpS6PF])/(OD[JNKInput]/OD[rpS6Input])}. The same approach was used to calculate the percentage of polysome-associated eEF1A2 in Fig. 8A to C. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ (W. S. Rasband, ImageJ; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

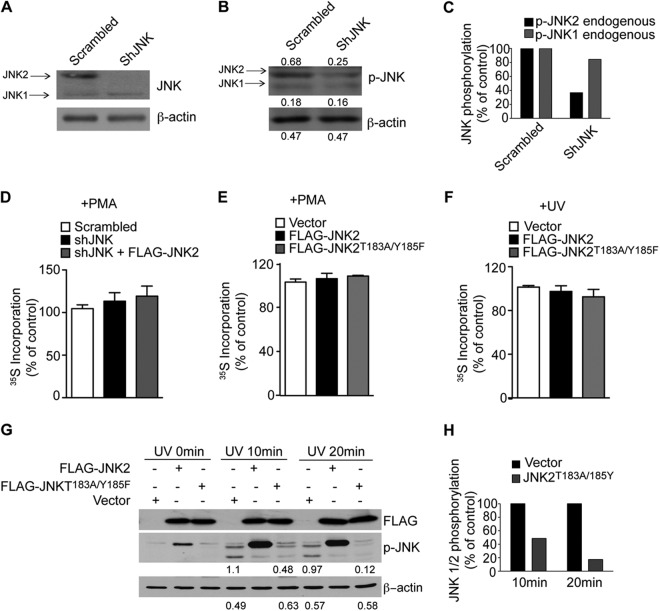

Fig 5.

JNK2 is not required for global translation. (A, B, and C) Levels of endogenous JNK1 and JNK2 expression (A) and activity (B) were monitored by Western blotting in control cells (Scrambled) and cells depleted of endogenous shJNK2 by shRNA (shJNK). Densitometric values are appended to the respective bands. (C) The densitometric values indicated in panel B were normalized to β-actin and are expressed as a percentage of the control (Scrambled). shJNK reduced JNK2 activity by 60%, while only a slight reduction of JNK1 was detected. (D, E, and F) Equal 35S incorporation at the 0-h time point shows that there was no major effect on protein synthesis in the indicated cell lines. Values are represented as mean values ± the SEM (n = 3). (G) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-JNK2 WT or FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F, irradiated with UV, and JNK phosphorylation was monitored by Western blotting at the indicated time points. Portions (30 μg) of the corresponding protein extracts were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels. β-Actin served as a loading control. Densitometric values corresponding to phosphorylation of endogenous JNKs in cells transfected with empty vector or FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F are indicated below the respective lanes and are summarized in panel H. JNK phosphorylation was reduced by 50 and 90% after 10 and 20 min, respectively.

eEF1A2 cross-linking with newly synthesized polypeptides from polysomal fractions.

Subconfluent cells were labeled in the presence of 50 nM PMA with a 10-μCi/ml [35S]methionine-cysteine mixture for 10 min. To analyze the amount of 35S-labeled polypeptides bound to FLAG-eEF1A2 on polysomes, the procedure to extract rRNA was modified to allow the cross-linking reaction between eEF1A2 and newly synthesized polypeptides as follows. Cells were lysed in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 30 mM MgCl2, 0.5% (vol/vol) sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and 1 mM DTT. After fractionation, polysomal fractions were pooled and incubated with or without 1 mM 3,3′-dithiobis[sulfosuccinimidylpropionate] (DTTSP; Pierce) for 30 min at room temperature. Cross-linking was stopped by the addition of Tris-HCl (pH 7.5, 30 mM final concentration), and polysomal fractions were diluted with five volumes of immunoprecipitation buffer (IP buffer; 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 30 mM MgCl2, 0.5% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40). Samples were precleared with 50 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham) for 30 min at 4°C, followed by incubation with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 h using end-over-end rotation at 4°C. After incubation, the beads were washed five times with IP buffer, and the immunoprecipitated material was eluted. DTTSP cross-links were reversed by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol, and the eluted materials were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Fluorographic detection of 35S was enhanced by incubating the gel with 1 M sodium salicylate for 1 h, as previously described (26). The gel was dried, exposed for 5 days on a phosphor screen, and analyzed using a Typhoon PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare).

To quantify the data, we undertook two independent quantification approaches: (i) the densitometric analysis of the 35S-labeled material (Fig. 4I) and (ii) scintillation counting (Fig. 4J). In the first method, the quantification was performed by measuring the OD of the total radioactivity within each lane (excluding the band corresponding to FLAG-eEF1A2; indicated by an arrow in Fig. 4) using ImageJ software (rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). This OD (which we referred to as “total radioactivity”) was then normalized to integrated density of FLAG-eEF1A2 signal. The boundaries of the FLAG-eEF1A2 band were defined in an unbiased way, being detected by the local maxima of a longitudinal profile across the lane. Thus, the resulting ratio accounts for potential interlane variability such as FLAG-eEF1A2 levels. In the second method, 1/10 of the immunoprecipitated material was TCA precipitated on a filter paper, and the radioactivity was measured by using scintillation fluid in a β-counter. The obtained values were then normalized to the integrated OD of FLAG-eEF1A2 signal as in the first method.

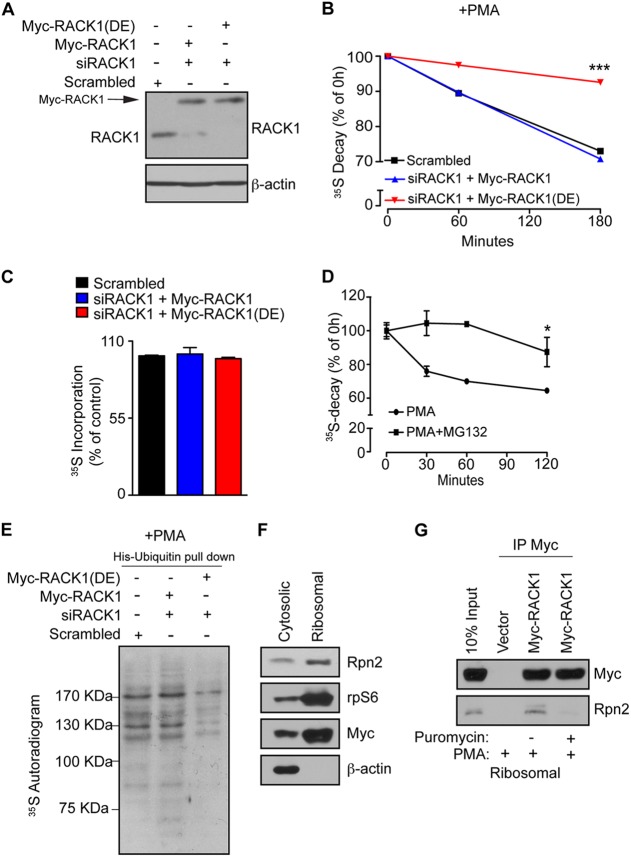

Fig 4.

Association of RACK1 with ribosomes is required for ubiquitination and degradation of NSPs. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with RNAi-insensitive Myc-RACK1 or Myc-RACK1R38D/K40E [Myc-RACK1(DE)], upon which the endogenous RACK1 was depleted using RACK1-specific siRNA (siRACK1). Scrambled siRNA was used as a control. The expression of the indicated constructs and the efficiency of RACK1 depletion were monitored by Western blotting. A total of 30 μg of the indicated cell lysate were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (B) The cells described in panel A were treated with 50 nM PMA for 30 min, and the stability of the NSPs was monitored by 35S pulse-chase (see Materials and Methods) after 1 and 3 h. Values obtained upon transfer of cells to cold media (0-h time point) were set to 100%, and data are represented as a mean values ± the SEM (n = 3). The expression of Myc-RACK1R38D/K40E significantly increased the stability of 35S-labeled polypeptides (P = 0.0006 compared to control cells at the 180-min time point; ANOVA, F3,8 = 62.62, P < 0.0001). (C) In contrast to the degradation of NSPs, protein synthesis was largely unaffected, as demonstrated by the lack of differences in the 35S incorporation after 30 min of labeling with [35S]Met-Cys. The data are represented as mean values ± the SEM (n = 3). (D) HEK293T cells were treated with PMA (50 nM) or PMA in combination with the proteasome inhibitor (50 nM PMA plus 50 μM MG132) for 2 h, and NSP degradation was monitored at 30-min, 60-min, and 2-h time points. Inhibition of the proteasome significantly attenuated the degradation of NSPs compared to untreated cells (Student t test, P = 0.0008 after 120 min). Values are represented as means ± the SEM (n = 3). (E) Cells described in panel A were transfected with His-ubiquitin, treated as in panel B, pulse-labeled with [35S]Met-Cys for 30 min, and subjected to His-ubiquitin pulldown under denaturing conditions (see Materials and Methods). The levels of ubiquitinated 35S-labeled NSPs were monitored by 35S autoradiography. (F) Cells expressing Myc-RACK1 WT (Myc-RACK1) were treated with 50 nM PMA for 30 min and fractionated into cytosolic and polysomal fractions. Portions (30 μg) of protein extracts from each fraction were used to monitor the distribution of the indicated proteins by Western blotting. rpS6 and β-actin served as markers for polysomal and cytoplasmic fraction, respectively. (G) Cells expressing Myc-RACK1 WT (Myc-RACK1) and control cells transfected with an empty vector were treated with a vehicle (0.1% DMSO), 50 nM PMA, or 50 nM PMA in combination with 100 μg of puromycin/ml for 30 min, fractionated as in panel F, and polysomal fractions were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody. Immunoprecipitates and input (10%) were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

Ribosome purification and in vitro binding assay.

40S and 60S ribosomal subunits were purified from nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega) as previously described (27). Briefly, ribosomes were diluted in 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM DTT to a final concentration of 50 OD254 units/ml. Ribosomes were incubated with 1 mM puromycin for 10 min on ice, followed by 10 min at 37°C. A 4 M concentration of KCl was slowly added to the ribosomes (drop by drop) until a final concentration of 0.5 M KCl was reached. Then, 1.7 ml of extract was separated on a 35-ml 10 to 40% sucrose gradient (in 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5 M KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT) using a SW32 rotor at 22,000 rpm for 18 h. Next, 1-ml fractions were collected manually, and the respective 254-nm rRNA absorbances were measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) to identify the fractions corresponding to 40S and 60S. Buffer was exchanged using Microcentricon-100 columns (Amicon) to obtain rRNA in a final buffer containing 0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM EDTA. The same columns were used to concentrate rRNA according to the manufacturer's protocols.

In vitro binding assay of JNK to high-salt washed ribosomal subunits was performed as previously described (28). Next, 5 pmol of purified ribosomal subunits were applied to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad), and the membrane was blocked for 1 h in 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dried skimmed milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. Portions (100 μl) of HEK293T extracts (50 mM HEPES NaOH [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 30 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaF, 100 mM 2-glycerophosphate, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Tween 20) and 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dried skimmed milk were incubated with the membrane for 1 h at room temperature. Unbound material was removed by washing the membrane three times (5 min each time) in PBS–0.5% (vol/vol) Tween 20. Western blot analysis was performed using the indicated antibodies. Since stripping of the nitrocellulose membrane removes the ribosomal subunits, one membrane was used to detect JNK using anti-JNK antibody, and a separate membrane was used to verify the positioning of native 40S and 60S. This latter membrane was probed with anti-rpS6 followed by anti-rpL7 antibody. As a consequence, the 40S subunit was still visible when detecting rpL7.

Protein sample preparation and analysis by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC)-liquid chromatography-(LC) tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis.

Samples were reduced with DTT (Sigma) alkylated with indoleacetamide (Sigma) and digested with modified sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega) according to standard procedures. Peptides were desalted using peptide Microtraps (Bruker-Michrom), dried, and subjected to automated ferric IMAC. The IMAC column (0.3 by 150.0 mm; Bruker-Michrom, Inc., Auburn, CA) contained Poros20MC beads (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). The flow rate of solvent C (0.1% formic acid, 5% acetonitrile [ACN]) through the IMAC column was 50.0 μl/min. All of the solvents and reagents used for auto-IMAC were injected into a 100-μl sample loop, and then a high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) valve was switched so that the solvent C flow drove the reagents out of the sample loop and through the IMAC column. After injection of each reagent into the sample loop and valve switching, the HPLC flow (50.0 μl/min, 100% solvent C) through the IMAC column was maintained for 4.0 min before the next injection. The first injection was 80.0 μl of 48.0 mM disodium dihydrate EDTA (EDTA; Sigma)–5.0% ACN. The second injection was 60.0 μl of 190.0 mM FeCl3 (Sigma)/5.0% ACN. The third injection was 40.0 μl of solvent C. The syringe was filled with 10.0 μl of H2O as pre-sample solvent to facilitate complete sample injection into the loop, followed by filling with the entire sample (40.0 μl in solvent C). The IMAC column effluent was collected for 4.0 min to yield the IMAC flowthrough fraction. A total of 80 μl of IMAC wash solvent (0.01% acetic acid in methanol-ACN-H2O [1:1:1]) was injected, and the IMAC column effluent was collected, yielding the IMAC wash fraction. Next, 20 μl of IMAC eluant (0.32% H3PO4 [Mallinckrodt, Inc.], 5.0% ACN) was injected, and the IMAC column effluent was collected to yield the IMAC elution fraction. IMAC fractions were placed in a SpeedVac (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 35°C for 15 min to deplete the ACN.

Peptides from the IMAC flowthrough, wash and elution fractions were subjected to duplicate reversed-phase (RP) HPLC-MS/MS analyses using a Paradigm MS4 HPLC/HTC-PAL autosampler (Bruker Michrom) and an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., San Jose, CA). The reversed-phase liquid chromatography gradient (solvent A = 0.1% formic acid; solvent B = 100% ACN) was 2% B to 30% B from 0 to 30.0 min, 80% B from 30.1 to 36.0 min, and 2% B from 36.1 to 46.0 min on a C18 Magic column (0.2 by 150 mm; Bruker-Michrom) at a flow rate of 2 μl/min, coupled to an Advance ionization source (Bruker-Michrom) The MS/MS method specified precursor ion scans in the Orbitrap at 60,000 resolution and data-dependent MS/MS scans of the most abundant precursors in the linear ion trap using collision-induced dissociation. Charge state screening and monoisotopic precursor selection was enabled, dynamic exclusion was enabled for 45 s with a repeat count of 2, multistage activation (MSA) was enabled, and the MS/MS threshold was set at 5,000 counts.

Database searches, with Sorcerer-Sequest (SageN Research, Inc., Milpitas, CA), were performed against the international protein index (IPI) ipi.humanV3.63 database specifying a peptide mass tolerance of 10.0 ppm and a monoisotopic fragment ion type differential modification for a maximum of three instances per peptide for oxidation (M) and phosphorylation (STY). Static modification of +57.02146 Da to Cys residues was specified. Filtering was at a predicted false discovery rate <0.02 with ProteinProphet (Trans-Proteomic Pipeline, Seattle, WA).

Statistical analysis.

Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed in triplicates at least three times. The data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc comparisons using Bonferroni's test in cases of significance. Significance was defined as P < 0.05 and indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001; and ***, P < 0.0001. All data are expressed as means ± the standard errors of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

RACK1 recruits JNK to the ribosome.

We have previously observed that overexpression of the JNK-activating kinase MKK7 results in cosedimentation of JNK with polysomes (19). Thus, we treated HEK293T cells with PMA, which activates JNK through MKK7 and PKC signaling (29–31), to determine whether the activation of JNK by external stimuli will also stimulate its association with polysomes. In untreated cells, a small fraction of JNK cosedimented with polysomes (0.38%) (Fig. 1A), which can be attributed to the experimental conditions required to prevent ribosome “runoff” (i.e., cycloheximide is known to stimulate JNK [32], as illustrated by a modest increase in JNK phosphorylation after 5 min of cycloheximide treatment [Fig. 1A]). PMA treatment increased the association of JNK with polysomes by 10-fold (3.74%) (Fig. 1B) and induced phosphorylation of polysome-associated JNK (Fig. 1B). This effect was abolished by puromycin, a translation elongation inhibitor that dissociates polysomes (Fig. 1C). Thus, PMA induces cosedimentation of JNK with polysomes and not with other large RNPs.

Next, we determined whether JNK directly associates with purified ribosomal subunits using a filter-binding assay. JNK associated with the 40S but not 60S ribosomal subunit (Fig. 1D). Consistently, in PMA-treated HEK293T cells JNK coimmunoprecipitated with 18S RNA and 40S ribosomal protein S6 (rpS6) but not with the 5′ mRNA cap-binding protein eIF4E. Puromycin disrupted the binding of JNK to 18S RNA and rpS6 (Fig. 1E). These results demonstrate that JNK interacts with the 40S ribosomal subunit and that this interaction preferentially occurs on the polysomes.

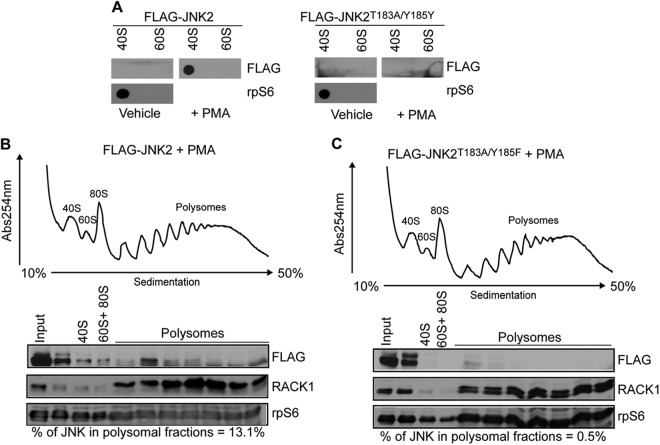

Polysome-associated JNK is phosphorylated (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, JNK:40S complexes were detected in PMA-treated but not in untreated HEK293T cells, thereby suggesting that the activation of JNK is required for its ribosomal association (Fig. 1D). Because JNK2 is preferentially associated with polysomes of PMA treated cells (Fig. 1B) we further investigated the impact of JNK2 activation on its interaction with ribosomes by expressing wild-type (WT) JNK2 and an inactive form of JNK2, mutated on its phosphoacceptor sites (JNK2T183A/Y185F [9, 33]). A filter binding assay revealed that WT JNK2, but not JNK2T183A/Y185F mutant, associates with 40S (Fig. 2A). In addition, a substantial amount of exogenous WT JNK2 cosedimented with the polysomes in PMA treated HEK293T cells (13.1%) (Fig. 2B), whereas this was not the case for JNK2T183A/Y185F (0.5%) (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these findings indicate that activation of JNK stimulates its interaction with ribosomes.

Fig 2.

JNK activity is required for its association with the ribosome. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-JNK2 or FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F and treated with a vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or PMA (50 nM), and the binding of respective proteins to the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits was determined by in vitro filter-binding assay, followed by Western blotting with an anti-FLAG antibody. rpS6 was used as marker for 40S ribosomal subunit. (B and C) HEK293T cells were transfected with WT FLAG-JNK2 (FLAG-JNK2) or FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F and treated with 50 nM PMA for 30 min. The corresponding cytoplasmic extracts were sedimented by centrifugation on 10 to 50% sucrose gradients. 40S, 60S, and 80S indicate the positions of the respective ribosomal subunits and the monosome on the gradient. Distributions of WT FLAG-JNK2 (FLAG-JNK2) or FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F across the gradient were monitored by Western blotting with an anti-FLAG antibody. The percentages of JNK in polysomal fractions relative to the input (quantified as described in Materials and Methods) are indicated below the blots. Ribosomal protein S6 (rpS6) was used as a loading control.

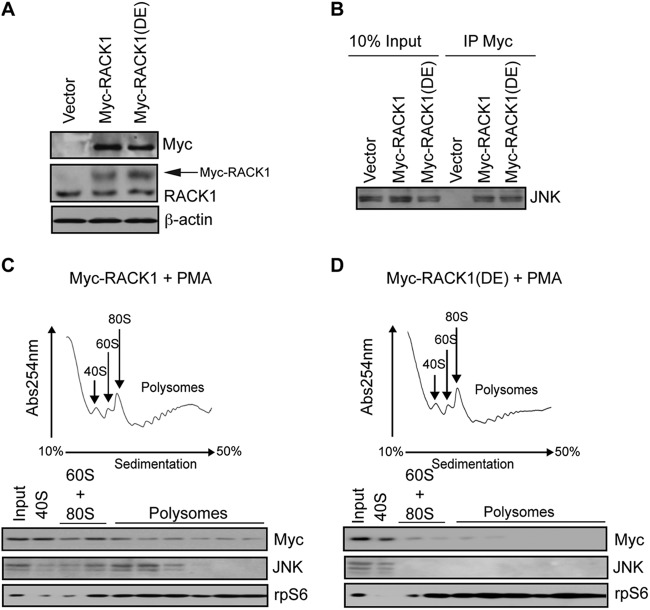

JNK directly interacts with RACK1 (29), which augments canonical activation of JNK by MKK4/7 via PKC phosphorylation (31). In addition to its role as cytosolic adaptor protein for a number of protein kinases, RACK1 is a structural component of the 40S ribosome (34, 35). In PMA-treated cells JNK mainly associates with light polysomes (Fig. 1B). This resembles the pattern of polysome distribution observed for PKCβII, which is recruited to the ribosome via RACK1 (28). Thus, we reasoned that RACK1 recruits JNK to the 40S ribosome. Similarly to 18S RNA and rpS6, RACK1 coimmunoprecipitates with JNK in PMA-treated HEK293T cells (Fig. 1E). However, in contrast to 18S RNA or rpS6, disruption of polysomes by puromycin did not abrogate the association of JNK with RACK1 (Fig. 1E), which is consistent with the notion that JNK/RACK1 complexes reside in other cellular locations (i.e., cytosol [29]), in addition to their presence on the polysomes. Therefore, to directly investigate whether RACK1 recruits JNK to the ribosome, we took advantage of the RACK1R38D/K40E mutant that does not bind the 40S ribosome (34, 36). Although WT RACK1 and RACK1R38D/K40E mutant were expressed in HEK293T cells at comparable levels (Fig. 3A) and exhibited similar binding to JNK (Fig. 3B), JNK associated with the polysomes in PMA treated cells expressing WT RACK1 but not the RACK1R38D/K40E mutant (Fig. 3C and D). Taken together, these data reveal that RACK1 recruits JNK to the ribosome.

Fig 3.

RACK1 recruits JNK to the ribosome. (A) 30 μg of the corresponding cell lysates was loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, and the expression of endogenous RACK1 and exogenous Myc-RACK1 and Myc-RACK1R38D/K40E [Myc-RACK1(DE)] mutant in HEK293T cells was monitored by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Exogenous Myc-RACK1 variants are indicated by an arrow. β-Actin served as a loading control. (B) Portions (1 μg) of total cell extracts from the cells described in panel A were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody (IP Myc), and the amount of JNK associated with Myc-RACK1 and Myc-RACK1R38D/K40E was determined by Western blotting. Inputs (10%) are shown in the left panel. (C and D) Polysome profiles of HEK23T cells transfected with Myc-RACK1 (C) or Myc-RACK1R38D/K40E (D) and treated with 50 nM PMA for 30 min. Then, 10 OD260 units of the corresponding cytoplasmic extracts were sedimented by centrifugation on 10 to 50% sucrose gradients, and the distribution of the indicated proteins across the gradient was monitored by Western blotting. rpS6 was used as a loading control.

A ribosome-bound RACK1/JNK2 complex promotes stress-induced degradation of NSPs.

We next investigated the functional significance of RACK1-mediated recruitment of JNK to the ribosome. We first expressed RNAi-insensitive WT RACK1 or RACK1R38D/K40E mutant in HEK293T cells and then depleted endogenous RACK1 using RNAi (Fig. 4A). Cells were treated with PMA, and the degradation of NSPs was monitored by a short pulse-labeling (10 min) with [35S]Cys-Met and chase in cold media. The stability of 35S-labeled polypeptides was increased ∼20% after 180 min (P < 0.001) in cells expressing the RACK1R38D/K40E mutant compared to those expressing WT RACK1 (Fig. 4B), whereas a comparable amount of 35S was incorporated into proteins in both cell lines (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that ribosome binding of RACK1 has a major effect on the degradation of NSPs but not on global protein synthesis.

Ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis is the major route of protein degradation and has been associated with the cotranslational degradation of NSPs (16). Treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 inhibited the degradation of NSPs in PMA-treated HEK293T cells (∼20%, P = 0.05, a decrease compared to the control after 120 min), which demonstrates that they are degraded by the proteasome (Fig. 4D). Thus, we sought to determine whether ribosomal association of RACK1 is required for the ubiquitination of NSPs by transfecting HEK293T cells with His-tagged ubiquitin, treating them with PMA and performing His-pulldown assays of 35S-labeled proteins. NSPs were ubiquitinated in control cells and in cells expressing WT RACK1 (Fig. 4E). In stark contrast, ubiquitination of 35S-labeled proteins was diminished in cells expressing the RACK1R38D/K40E mutant (Fig. 4E). These results indicate that the ubiquitination of NSPs following PMA treatment requires the association of RACK1 with the ribosome.

To further establish the role of RACK1 in linking ribosome and proteasome function, we monitored the association between RACK1 and the proteasome subunit Rpn2 in the polysomal fractions of PMA-treated HEK293T cells. RACK1 and Rpn2 were coimmunoprecipitated from the polysomal fractions in PMA-treated cells, and this interaction required integrity of polysomes, as demonstrated by its sensitivity to puromycin (Fig. 4F and G). Consistent with these findings, a previous study raised the possibility that RACK1 provides a link between the translational machinery and the proteasome (16). Collectively, these data indicate that ribosomal association of RACK1 is required for proteasome-dependent degradation of NSPs.

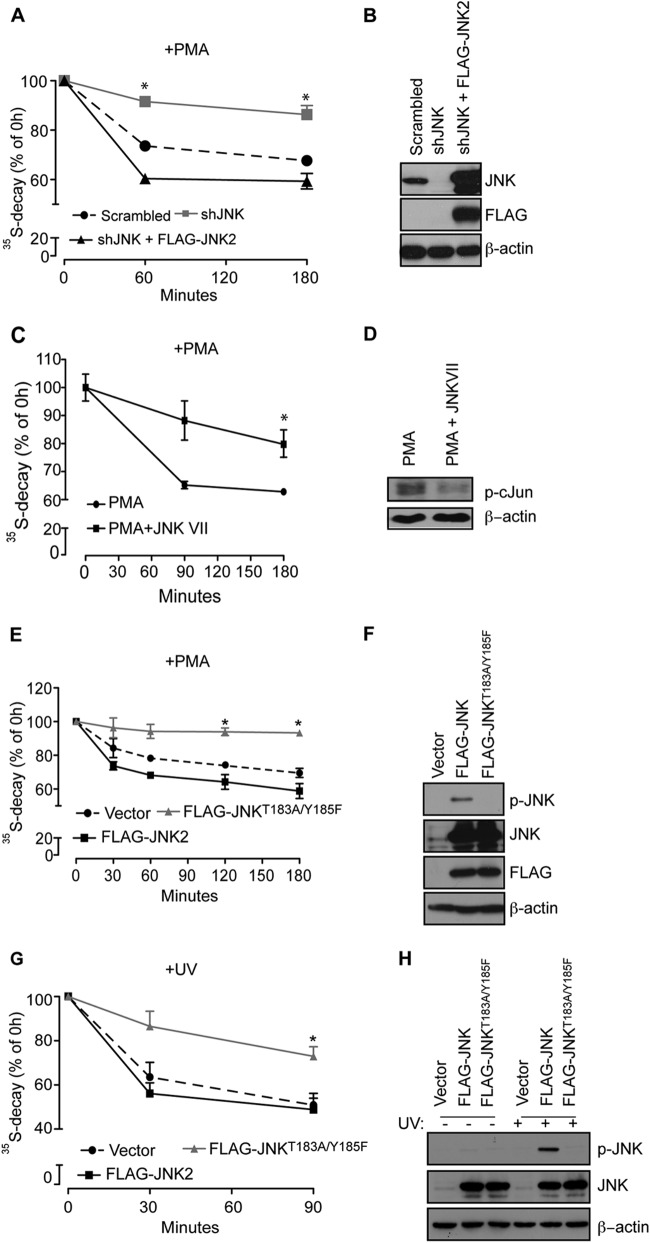

Since JNK is recruited to ribosomes through RACK1, we next determined the role of JNK in the degradation of NSPs by specifically knocking down JNK2 (Fig. 5A). Depletion of JNK2 only marginally affected JNK1 activity (Fig. 5B and C). Similar to expression of RACK1R38D/K40E mutant, JNK2 depletion in HEK293T cells substantially attenuated the PMA-induced degradation of [35S]-labeled polypeptides (∼20%, P = 0.01, decrease compared to control after 180 min), which was restored by the expression of siRNA-insensitive WT JNK2 (Fig. 6A and B). Of note, JNK status in the cell did not exert a major effect on overall protein synthesis (Fig. 5D to 5F), which is consistent with the tenet that selective functions are mediated by distinct subcellular pools of JNK (18). Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of JNK (JNK-Inhibitor VII, TAT-TI-JIP153-163) attenuated degradation of NSPs in PMA-treated HEK293T cells (17%, P = 0.05, after 180 min) (Fig. 6C and D). Time-course experiments revealed that overexpression of WT JNK2 in HEK293T cells increases PMA-induced degradation of NSPs compared to control cells (Fig. 6E and F). In contrast, increased stability of NSPs was observed in HEK293T cells expressing JNK2T183A/Y185F (37, 38) compared to control cells (∼20%, P = 0.01, after 180 min) (Fig. 6E and F). Importantly, JNK2T183A/Y185F effectively inhibits JNK (∼50% to ∼90% at 10- and 20-min time points, respectively) after UV irradiation (Fig. 5G and H) (37, 38). Collectively, these data demonstrate that JNK2 activity is required for degradation of NSPs but not global protein synthesis.

Fig 6.

Kinase activity of JNK is required for degradation of NSPs. (A) The stability of NSPs in PMA-treated HEK293T cells was monitored by a [35S]Met-Cys pulse-chase at the 1- and 3-h time points. Values obtained upon transfer of cells to cold media (0 h time point) were set to 100%, and the data are represented as means ± the SEM (n = 3). Depletion of JNK (shJNK) significantly increased stability of 35S-labeled polypeptides compared to Scrambled control and cells in which expression of JNK was rescued with WT JNK2 (shJNK + FLAG-JNK2; P = 0.0101 compared to the Scrambled control; ANOVA, F2,7 = 20.77, P = 0.0038). (B) Portions (30 μg) of the indicated cell lysates were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, and the expression of exogenous WT JNK2 (FLAG-JNK2) and endogenous JNK was monitored by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. β-Actin served as a loading control. (C) HEK293T cells were treated for 3 h with 50 nM PMA alone or in combination with 10 μM JNK-Inhibitor VII (TAT-TI-JIP153-163; JNKVII), and the degradation of NSPs was monitored after the 90-min and 3-h time points. The degradation of NSPs was significantly suppressed by JNK-Inhibitor VII (PMA plus JNK VII) compared to the control (PMA) (Student t test: P = 0.0063 [at 90 min] and P = 0.05 [at 180 min]). Values are represented as means ± the SEM (n = 3). (D) JNK-Inhibitor VII suppressed JNK activity, as monitored by the phosphorylation of c-Jun on Ser63 by Western blotting. Portions (40 μg) of the indicated cell lysates were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels. β-Actin served as a loading control. (E and H) Degradation of NSPs was monitored by a [35S]Met-Cys pulse-chase in HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG-JNK2 and FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F and treated with 50 nM PMA for the indicated time points (E) or exposed to UV light for 90 s (see Materials and Methods) (G). Cells expressing FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F exhibited a significant increase in the stability of 35S-labeled polypeptides under both conditions compared to cells expressing FLAG-JNK2 (+PMA [E], P = 0.0114 for FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F compared to FLAG-JNK2 [180 min], ANOVA, F2,3 = 60.98, P = 0.0037; +UV [G], P = 0.0086, FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F compared to FLAG-JNK2 [90 min], ANOVA, F2,15 = 9.35, P = 0.0023). (F and H) Portions (30 μg) of the indicated cell lysates were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, and the levels of FLAG-JNK2 and FLAG-JNK2T183A/Y185F and the phosphorylation of JNK in PMA (F)- or UV (I)-treated cells were monitored by Western blotting. β-Actin served as a loading control.

We next investigated whether other types of stress known to activate JNK, such as UV irradiation (38), would also reduce the stability of NSPs in a JNK-dependent manner. Since exposure to UV irradiation inhibits protein synthesis (39), UV treatment was performed immediately after 35S labeling. Under these conditions, we observed reduction in protein degradation in HEK293T cells overexpressing JNK2T183A/Y185F mutant compared to WT JNK2 (12% ± 2.5% after 90 min, P = 0.0086) (Fig. 6G and H). These findings reveal that JNK mediates stress-induced degradation of NSPs.

eEF1A2 is a JNK substrate that associates with—and regulates the stability of—NSPs.

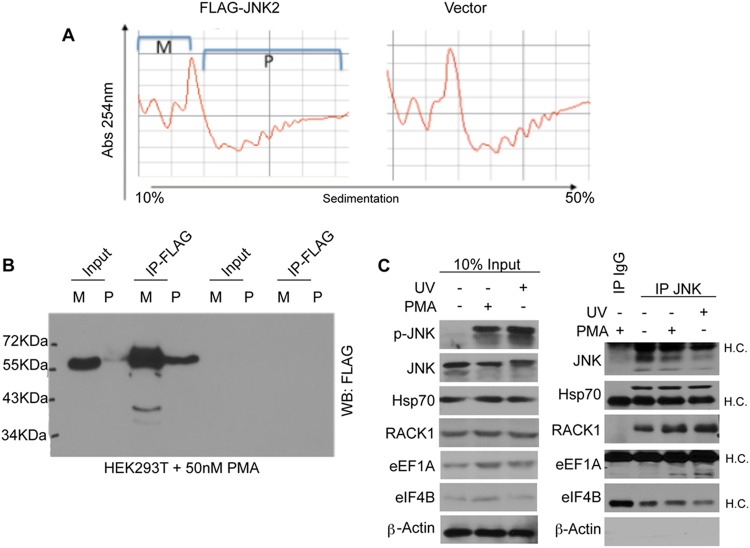

To identify the substrates of ribosome-associated JNK, which play a role in the degradation of NSPs, we expressed FLAG-tagged WT JNK2 in HEK293T cells, which were then treated with PMA to activate JNK and induce its association with polysomes. Polysome fractions were immunoprecipitated with FLAG-antibody (Fig. 7A and B) and subjected to mass spectrometry analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). A series of immunoprecipitation experiments confirmed that endogenous JNK associates with RACK1, Hsp70, and eEF1A, after PMA stimulation or UV irradiation (Fig. 7C). This repertoire of interacting partners of ribosome-associated JNK (e.g., RACK1 and ribosomal proteins rpS3 and rpS16 which associate with RACK1 [40], chaperones [e.g., Hsp70], and factors involved in ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent proteolysis) further supports a role for JNK in the regulation of the stability of NSPs.

Fig 7.

Polysome-associated JNK2 forms complexes containing translation initiation and elongation factors, chaperones, and components of the proteasome. (A) Polysomal profiles were obtained using ∼50 million PMA-treated HEK293T cells transfected with empty vector or FLAG-JNK2. Monosomal (M) and polysomal (P) fractions were pulled together, followed by immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody. (B) 1/10th of the immunoprecipitated material was subjected to Western blotting, and the remaining material was analyzed by mass spectrometry as described in Materials and Methods. (C) HEK293T cells were treated with 50 nM PMA or UV (see Materials and Methods) and immunoprecipitated with an anti-JNK antibody. Isotype-matched IgG was used as a control. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Inputs (10%) are shown in the left panel. H.C., IgG heavy chains.

Whereas yeast has a single eEF1A isoform, mammals express two eEF1A isoforms: eEF1A1 and eEF1A2 (41). eEF1A2 contains a JNK-like docking motif and two putative MAPK phosphorylation sites (Ser205 and Ser358). Strikingly, these serine/proline residues are absent in eEF1A1 (Fig. 8A). JNK coimmunoprecipitates with eEF1A2, but not with eEF1A1, in UV-irradiated or PMA-treated HEK293T cells (Fig. 7C). Moreover, JNK2 phosphorylates eEF1A2 but not eEF1A1 in vitro (Fig. 8B). JNK2-dependent phosphorylation is attenuated in eEF1A2 mutants in which Ser205 and Ser358 are replaced by alanines (eEF1A2S205A or eEF1A2S358A) and is strongly decreased in the double Ser205Ala/Ser358Ala (eEF1A2S205A/S358A) mutant (Fig. 8B). To confirm eEF1A2 phosphorylation by JNK in cells, we performed MS analysis, as well as generated antibodies against a phosphopeptide harboring the S358 phosphoacceptor site (p-eEF1A2). MS/MS analysis of polysome fractions identified S205 and S358 phosphorylated peptides (Fig. 8C-I). Phosphorylation of these peptides was also found in phosphoproteome analysis of embryonic stem cells (I. Singec et al., unpublished data). Notably, the newly developed p-eEF1A2 antibody detected phosphorylated eEF1A2 prior to but not following phosphatase treatment (Fig. 8C-II). The p-eEF1A2 antibodies also detected exogenously expressed FLAG-eEF1A2 after UV irradiation (Fig. 8C-III). Depletion of endogenous eEF1A2 by shRNA reduced the p-eEF1A2 signal (Fig. 8C-IV), thus indicating that p-eEF1A2 antibody is specific. p-eEF1A2 antibody was next used to determine the phosphorylation of polysome-associated endogenous eEF1A2. Strikingly, polysome-associated eEF1A2 was phosphorylated in UV-irradiated but not in untreated HEK293T cells (Fig. 8C-V). Taken together, these data show that JNK2 specifically phosphorylates eEF1A2 on residues Ser205 and Ser358 and that polysome-associated eEF1A2 is phosphorylated at these sites in vivo.

Next, we established the functional role for JNK-mediated phosphorylation of eEF1A2. eEF1A2S205A or eEF1A2S358A mutant decreased the degradation of 35S-labeled polypeptides compared to WT eEF1A2, and this effect was more pronounced in cells expressing the double eEF1A2S205A/S358A mutant (29.5% ± 5.87%, P = 0.0052 reduction compared to WT eEF1A2 after 180 min) (Fig. 8D and E). We further examined the effects of PMA (Fig. 8F and G) or UV (Fig. 8H and I) on NSP degradation in HEK293T cells overexpressing WT eEF1A2 or nonphosphorylatable eEF1A2S205A/S358A or phosphomimetic eEF1A2S205D/S358D mutant. In these experiments, the eEF1A2S205D/S358D mutant increased the degradation of NSPs relative to WT eEF1A2 (PMA after 180 min, 7% ± 1.75%, P = 0.049; UV after 90 min, 6.7% ± 3.4%, P = 0.0023), whereas eEF1A2S205A/S358A increased their stability (PMA after 180 min, 14.8% ± 1.88%, P = 0.0051; UV after 90 min, 11.6% ± 3.78%, P = 0.0029). The more pronounced induction of NSP degradation exerted by eEF1A2S205D/S358D mutant, relative to WT eEF1A2, can be explained by constitutive activation of eEF1A2S205D/S358D mutant compared to the transient stimulation of WT eEF1A2 upon PMA or UV treatment (Fig. 8F to I). Of interest, eEF1A2S205D/S358D mutant reduced JNK phosphorylation, although expressed at a lower level than the WT and the eEF1A2S205A/S358A mutant (Fig. 8I), suggesting the possibility of a negative-feedback loop between phsopho-eEF1A2 and JNK (see Discussion).

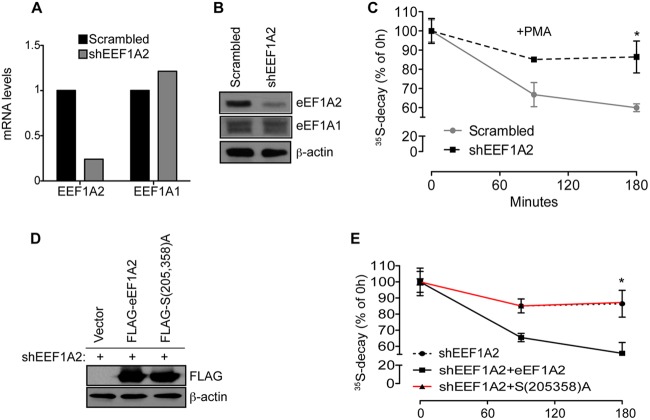

To further establish the role of eEF1A2 in mediating the effects of JNK on the stability of NSPs, we generated eEF1A2-specific shRNA, which was used to selectively deplete eEF1A2 but not eEF1A1 (Fig. 9A and B). Depletion of eEF1A2 strongly attenuated PMA-induced degradation of NSPs in HEK293T cells (∼30%, P = 0.04, compared to a control after 180 min) (Fig. 9C). We next reexpressed shRNA-resistant WT eEF1A2 or eEF1A2S205A/S358a mutant in HEK293T cells, wherein endogenous eEF1A2 was depleted (Fig. 9D). Reexpression of WT eEF1A2 but not eEF1A2S205A/S358A mutant stimulated the degradation of NSPs upon PMA treatment (∼30%, P = 0.02 after 180 min), whereby the kinetics of NSP degradation were comparable to that observed in control cells (Fig. 9E). These data demonstrate that JNK-mediated phosphorylation of eEF1A2 is required for NSP degradation.

Fig 9.

eEF1A2 depletion stabilizes NSPs. (A and B) HEK293T cells were infected with Scrambled or EEF1A2-specific shRNA. Isoform-specific depletion of eEF1A2 but not eEF1A1 was verified by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (A) and Western blotting (B), wherein 15 μg of protein extracts was loaded on SDS-PAGE gels. β-Actin served as a loading control. (C) The stability of the NSPs in the cells described in panels A and B and treated with 50 nM PMA for the indicated time points was monitored by a [35S]Met-Cys pulse-chase. Values obtained upon transfer of cells to cold medium (0-h time point) were set to 100%, and the data are represented as means ± the SEM (n = 3). Depletion of eEF1A2 significantly increased stability of 35S-labeled polypeptides compared to the Scrambled control (P = 0.045 and P = 0.0419 after 90 and 180 min, respectively). (D) Expression of eEF1A2 in cells in which endogenous eEF1A2 was depleted by RNAi was rescued with shRNA-insensitive FLAG-eEF1A2 (shEEF1A2 + eEF1A2) or eEF1A2S205A/S358A [shEEF1A2 + S(205,358)A]. Protein extracts (30 μg) were loaded on SDS-PAGE. The levels of FLAG-eEF1A2 and FLAG-eEF1A2S205A/S358A were monitored by Western blotting with an anti-FLAG antibody. β-Actin served as a loading control. (E) The stability of NSPs in cells described in panel D was monitored was monitored by a [35S]Met-Cys pulse-chase. Whereas reexpression of WT FLAG-eEF1A2 (shEEF1A2 + eEF1A2) resulted in the degradation of NSPs comparable to control cells (shEEF1A2 + vector), this effect was absent in the cells expressing eEF1A2S205A/S358A [shEEF1A2 + S(205,358)A] (P = 0.02 shEEF1A2 compared to shEEF1A2 + eEF1A2 [90 and 180 min], ANOVA, F1,4 = 7.896, P = 0.0483).

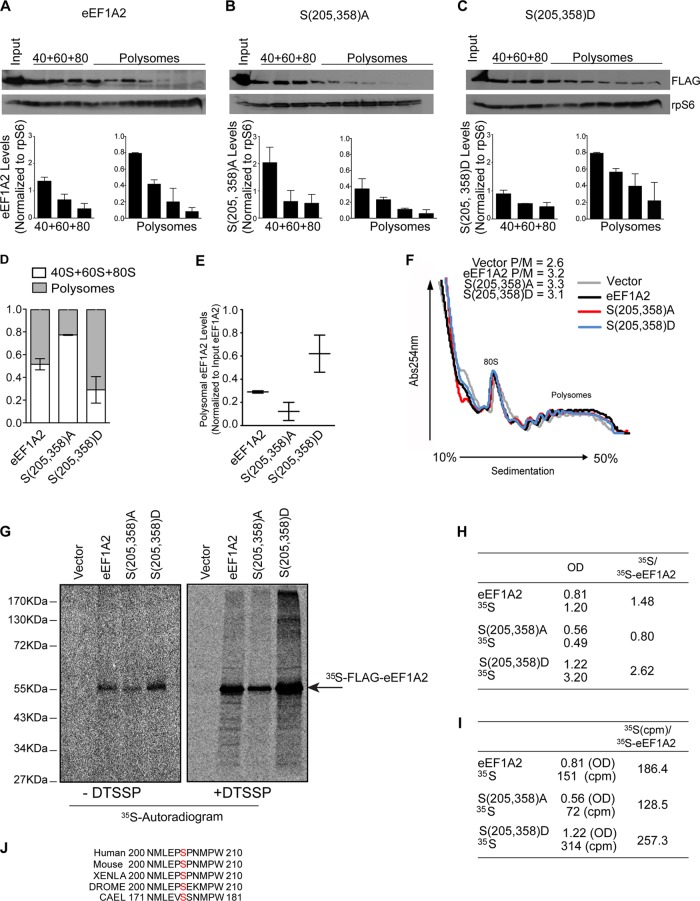

Since polysome integrity is required for association of JNK with 40S ribosome (Fig. 1C and E), we investigated the distribution of eEF1A2 on the polysomes as a function of its phosphorylation status. Compared to WT eEF1A2, eEF1A2S205A/S358A cosedimented with polysomes to a lesser extent (14.5% ± 3.9% compared to 6.1% ± 3.9%) (Fig. 10A, B, D, and E). Conversely, the phosphomimetic eEF1A2S205D/S358D mutant was more abundant in polysomal fractions than WT eEF1A2 (31% ± 8% compared to 14.5% ± 3.9%) (Fig. 10A, C, D and E). These findings indicate that JNK-mediated phosphorylation of eEF1A2 increases its association with polysomes. Since eEF1A recruits the aminoacylated-tRNA during elongation of polypeptide chains and its association with the polysomes appears to be modulated by phosphorylation, we sought to determine whether JNK affects the elongation step of mRNA translation. To this end, ribosomal profiling was carried out in the absence of cycloheximide to allow ribosomal runoff. Defects in translation elongation lead to decelerated ribosome runoff and subsequent retention of polysomes, which results in an increased polysome/monosome ratio (42). No significant differences in the polysome/monosome ratios were observed in cells overexpressing WT eEF1A2 (polysome/monosome ratio = 3.2), eEF1A2S205A/S358A mutant (polysome/monosome ratio = 3.3), or eEF1A2S205D/S358D mutant (polysome/monosome ratio = 3.1) (Fig. 10F). These findings demonstrate that phosphorylation of eEF1A2 by JNK does not impact translation elongation.

Fig 10.

eEF1A2 phosphorylation stimulates its association with polysomes and NSPs, but it is dispensable for translation elongation. (A to C) Cells were transfected with FLAG-eEF1A2 (eEF1A2) (A), FLAG-eEF1A2S205A/S358A [S(205,358)A] (B), or FLAG-eEF1A2S205D/S358D [S(205,358)D] mutant (C) and treated with 50 nM PMA for 30 min. Representative distributions of corresponding proteins were monitored in prepolysomal and polysomal fractions by Western blotting. Ribosomal protein S6 (rpS6) served as a loading control. Bar graphs representing the average densitometric eEF1A2, FLAG-eEF1A2S205A/S358A [S(205,358)A], and FLAG-eEF1A2S205D/S358D [S(205,358)D]/rpS6 densitometric ratios from each fraction are shown below the blots. The distribution of corresponding proteins in 40S, 60S, and 80S and polysomal fractions relative to rpS6 are summarized in panel D (quantification was performed as described in Materials and Methods). (E) In addition, the distribution of eEF1A2, FLAG-eEF1A2S205A/S358A [S(205,358)A], and FLAG-eEF1A2S205D/S358D [S(205,358)D] was also normalized to the amount of eEF1A2 in the input (n = 2). (F) Polysomal profiles obtained in the absence of cycloheximide from HEK293T cells treated as for panel C and overexpressing WT FLAG-eEF1A2 (eEF1A2), FLAG-eEF1A2S205A/S358A [S(205,358)A] mutant, or FLAG-eEF1A2S205D/S358D [S(205,358)D] mutant. A total of 10 OD260 units of corresponding cytoplasmic extracts were sedimented by centrifugation on 10 to 50% sucrose gradients. Polysome/monosome ratios are indicated. (G) HEK293T cells were transfected as for panels A to C, and polysomal fractions were isolated after 15 min of labeling with [35S]Met-Cys with or without DTSSP (see Materials and Methods). A total of 15 OD260 units of the corresponding cytoplasmic extracts were sedimented by centrifugation on 10 to 50% sucrose gradients, and polysomal fractions were immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by autoradiography (G and H) or liquid scintillation counting (I). (H) Densitometric analysis of the autoradiogram in panel G. Ratios between 35S-labeled proteins and [35S]eEF1A2 levels (arbitrary units) are shown. 35S-labeled proteins (35S) refer to the radioactive signal within each lane, excluding the discrete band of eEF1A2 variants (arrow; for details see Materials and Methods). OD, optical density. (I) Radioactivity of immunoprecipitated material normalized to the OD values obtained for 35S-labeled FLAG-eEF1A2 WT (eEF1A2), 35S-labeled FLAG-eEF1A2S205A/S358A [S(205,358)A], and 35S-labeled FLAG-eEF1A2S205D/S358D [S(205,358)D] (discrete bands are depicted in panel G).

Although earlier studies have shown that eEF1A binds nascent polypeptides in vitro (9), the identity of the eEF1A isoform involved remains unknown. NSPs are rapidly released to the cytosol upon completion of their synthesis (43). Therefore, to capture the interaction between eEF1A2 and newly synthesized polypeptides, we labeled HEK293T cells with [35S]Met-Cys and determined whether eEF1A2 can be cross-linked with 35S-labeled proteins in the polysomal fractions. We used a reversible cross-linker DTSSP (see Materials and Methods), which preserves the binding of ribosome-associated proteins with NSPs (44). Since polysomal fractions are enriched in NSPs and largely devoid of cellular proteins other than ribosomal proteins (45), this approach allowed us to directly estimate the amount of NSPs associated with eEF1A2. Consistent with its distribution on the polysomes (Fig. 10A to E), the amount of 35S-labeled eEF1A2S205D/S358D mutant that was pulled down from the polysomal fractions was higher than that observed for WT eEF1A2, whereas the amount of eEF1A2S205A/S358A mutant was the lowest (Fig. 10G). To avoid potential misinterpretation of the results and to account for the differences in the polysomal distribution of WT eEF1A2, eEF1A2S205D/S358D, and eEF1A2S205A/S358A mutant we carried out two independent quantification approaches (see Materials and Methods): densitometric analysis (Fig. 10H) and scintillation counting (Fig. 10I). Both quantification methods indicated that the highest amount of NSPs is cross-linked with eEF1A2S205D/S358D mutant, intermediate with WT eEF1A2, and the lowest with eEF1A2S205A/S358A mutant (Fig. 10G to I). Consistent with the rapid release of NSPs from the polysomes (43), no detectable amounts of NSPs were observed in the absence of DTSSP (Fig. 10G). These results indicate that eEF1A2 associates with NSPs on the polysomes, whereby JNK-mediated phosphorylation of eEF1A2 increases this association. The latter is consistent with the observation that the relative enrichment of eEF1A2 on the polysomes is influenced via its phosphorylation by JNK (Fig. 10A to E and G).

DISCUSSION

As a central component of the cellular stress response, JNK phosphorylates substrates implicated in ROS production, proliferation, survival, or death pathways (46). The present study reveals a previously unrecognized role of JNK in the control of NSP stability, thereby constituting an important stress-induced quality control of NSPs. We have previously shown that JNK and RACK1 form complexes in the cytosol (29). Here, we demonstrate that JNK is recruited to polysomes via RACK1. In nonstressed cells, a minor fraction of phosphorylated JNK is associated with polysomes, and yet the binding of JNK to polysomes increased substantially following stress. The basal pool (minor albeit noticeable) of polysome-bound JNK may be due to the experimental conditions used in our studies (whereby JNK is partially activated by short cycloheximide treatment, which is used to avoid ribosome “runoff”). Alternatively, it is plausible that the small pool of polysome-bound JNK prior to stress represents the basal level of JNK, which contributes to the regulation of NSPs under such conditions. The availability of such a small pool may secure rapid activation of JNK on polysomes to enable timely control of NSP stability. The latter is consistent with the observation that JNK is bound to RACK1 even prior to PMA or UV treatment and that JNKT183A/Y185F could be detected, albeit in limited amount, on polysomes but not on the 40S ribosomal subunit.

In response to stress, polysomal abundance of JNK increases by ∼10-fold to accommodate increased demand for quality control of NSPs. Polysome-associated JNK phosphorylates eEF1A2, which increases its association with NSPs, and the concomitant degradation of NSPs by the proteasome. In agreement with this, eEF1A2 binds the proteasomal subunit Rpn2 (data not shown), which is consistent with the binding of polysome-associated RACK1 to the proteasomes (Fig. 4G) and the observations that mammalian eEF1A2 may be involved in delivering misfolded NSPs to the proteasome (47–49). Importantly, the JNK phosphorylation sites on eEF1A2 at Ser205 and Ser358 are evolutionarily conserved (Fig. 10J), strongly suggesting a phylogenetic conservation of the control of eEF1A2 by JNK phosphorylation and its role in the stress-induced control of NSP stability.

JNK directly interacts with the WD4 domain of RACK1 (29), which is exposed on the surface of 40S ribosome (40), and has been implicated in nascent peptide-dependent translation arrest (50). RACK1 is positioned next to the mRNA exit channel (34), which is located on the opposite side of the ribosome from the polypeptide exit tunnel (51). Thus, it is unlikely that JNK phosphorylated eEF1A2 complex associates directly with the emerging polypeptide chain on the individual ribosomes. In contrast, in polysomes, individual ribosomes are tightly packed and highly organized (3), which is expected to increase the exposure of NSPs to elevated concentrations of JNK-phosphorylated eEF1A2. Indeed, phosphorylation of eEF1A2 by JNK appears to increase abundance of polysomal eEF1A2, whereas puromycin treatment, which disrupts ribosomal architecture characteristic of polysomes leads to dissociation of JNK from the ribosome and disruption of ribosome-associated JNK complexes. These findings raise an intriguing possibility whereby extensive stress induces a switch in JNK function from quality control of NSPs to cell death programs.

What is the physiological significance of stress-induced degradation of nascent polypeptides? First, this may be a global effect that is one aspect of the cellular defense to stress. Nascent polypeptides are more susceptible to misfolding under stress and thus require continuous chaperone surveillance (52). Thus, it is advantageous to eliminate such damaged peptides by accelerating their degradation under stress conditions and therefore decreasing the workload of chaperone machinery. Alternatively, there could be a subset of nascent polypeptides that are selectively affected by JNK-phosphorylated eEF1A2, perhaps including polypeptides that are vulnerable under stress; this aspect merits further investigation. It is noteworthy that eEF1A has been shown to induce ubiquitin-dependent degradation of certain Nα-acetylated proteins (53) that are implicated in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and carcinogenesis (54–56); indeed, both eEF1A2 and JNK have been implicated as important regulators of these cellular processes (18, 33, 57–59). Importantly, eEF1A2 is overexpressed in a variety of tumors, including ovarian and breast cancers (60, 61). The latter may have implications for NPS and global ER stress. By analogy to our own observations, constitutive expression of phosphomimetic eEF1A2S205D/S358D was associated with partial inhibition of JNK activity, pointing to a plausible negative-feedback mechanism set to limit JNK own activity and, in turn, eEF1A2 availability. Tumor cells may escape this feedback regulation through upregulation of eEF1A2 expression, which is expected to endow tumor cells with a higher capacity to degrade misfolded NSPs; a mechanism that would contribute to the notorious resistance of tumor cells to stress.

In addition to regulating the stability of NSPs, JNK may play a role in their folding. Consistent with this possibility, we also found several chaperones, such as Hsp70 and TRiC, associated with polysomal JNK. Hsp70 plays an important role in nascent polypeptide organization, while TRiC is involved in the folding of newly synthesized polypeptides that are aggregation-prone because of their complex topology (62). Given this, it is plausible that the involvement of JNK in controlling NSP stability is part of a greater network, of which eEF1A2 is the first identified component.

In conclusion, the finding that ribosome-associated RACK1/JNK/eEF1A2 complexes govern the stability of NSPs constitutes a previously unrecognized quality control mechanism for NSPs in mammalian cells under stress, which complements well-established effects of stress on protein synthesis via modulation of mRNA translation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Zhao-Qing Luo and Charlotte R. Knudsen for providing pGEX-6-P1/GST-eEF1A1 and pGEX-1/GST-eEF1A2, respectively. The pcDNA4/Myc-RACK1 and Myc-RACK1R38D/K40E constructs were kindly provided by Mutsuhiro Takekawa. We are grateful to Martin Wiedmann, Martin Schmeing, Stefano Biffo, Jonathan M. Lee, and Yuri Svitkin for invaluable advice and Valerie Henderson for help with editing the manuscript. We thank Amy Archuleta and Mike Browning of Phosphosolution for providing the data for the protein phosphatase effect on p-eEF1A2.

V.G. was supported by an EMBO Long-Term fellowship. Support by NCI grant (CA051995) to Z.A.R. is gratefully acknowledged. I.T. is a CIHR Young Investigator and acknowledges support from CIHR and FRSQ. N.S. acknowledges support from CIHR and TFI.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 April 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01362-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kramer G, Boehringer D, Ban N, Bukau B. 2009. The ribosome as a platform for cotranslational processing, folding, and targeting of newly synthesized proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:589–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jha S, Komar AA. 2011. Birth, life, and death of nascent polypeptide chains. Biotechnol. J. 6:623–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brandt F, Carlson LA, Hartl FU, Baumeister W, Grunewald K. 2010. The three-dimensional organization of polyribosomes in intact human cells. Mol. Cell 39:560–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van den Berg B, Ellis RJ, Dobson CM. 1999. Effects of macromolecular crowding on protein folding and aggregation. EMBO J. 18:6927–6933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Netzer WJ, Hartl FU. 1997. Recombination of protein domains facilitated by cotranslational folding in eukaryotes. Nature 388:343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nicola AV, Chen W, Helenius A. 1999. Cotranslational folding of an alphavirus capsid protein in the cytosol of living cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:341–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sherman MY, Goldberg AL. 2001. Cellular defenses against unfolded proteins: a cell biologist thinks about neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron 29:15–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiedmann B, Sakai H, Davis TA, Wiedmann M. 1994. A protein complex required for signal-sequence-specific sorting and translocation. Nature 370:434–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hotokezaka Y, Tobben U, Hotokezaka H, Van Leyen K, Beatrix B, Smith DH, Nakamura T, Wiedmann M. 2002. Interaction of the eukaryotic elongation factor 1A with newly synthesized polypeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18545–18551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saito K, Kobayashi K, Wada M, Kikuno I, Takusagawa A, Mochizuki M, Uchiumi T, Ishitani R, Nureki O, Ito K. 2010. Omnipotent role of archaeal elongation factor 1α (EF1α) in translational elongation and termination, and quality control of protein synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:19242–19247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chuang SM, Chen L, Lambertson D, Anand M, Kinzy TG, Madura K. 2005. Proteasome-mediated degradation of cotranslationally damaged proteins involves translation elongation factor 1A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:403–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dimitrova LN, Kuroha K, Tatematsu T, Inada T. 2009. Nascent peptide-dependent translation arrest leads to Not4p-mediated protein degradation by the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 284:10343–10352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nillegoda NB, Theodoraki MA, Mandal AK, Mayo KJ, Ren HY, Sultana R, Wu K, Johnson J, Cyr DM, Caplan AJ. 2010. Ubr1 and Ubr2 function in a quality control pathway for degradation of unfolded cytosolic proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 21:2102–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schubert U, Anton LC, Gibbs J, Norbury CC, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. 2000. Rapid degradation of a large fraction of newly synthesized proteins by proteasomes. Nature 404:770–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turner GC, Varshavsky A. 2000. Detecting and measuring cotranslational protein degradation in vivo. Science 289:2117–2120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sha Z, Brill LM, Cabrera R, Kleifeld O, Scheliga JS, Glickman MH, Chang EC, Wolf DA. 2009. The eIF3 interactome reveals the translasome, a supercomplex linking protein synthesis and degradation machineries. Mol. Cell 36:141–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karin M. 1998. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades as regulators of stress responses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 851:139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gutierrez GJ, Tsuji T, Chen M, Jiang W, Ronai ZA. 2010. Interplay between Cdh1 and JNK activity during the cell cycle. Nat. Cell Biol. 12:686–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Topisirovic I, Gutierrez GJ, Chen M, Appella E, Borden KL, Ronai ZA. 2009. Control of p53 multimerization by Ubc13 is JNK-regulated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:12676–12681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gandin V, Brina D, Marchisio PC, Biffo S. 2010. JNK inhibition arrests cotranslational degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803:826–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grosso S, Volta V, Vietri M, Gorrini C, Marchisio PC, Biffo S. 2008. Eukaryotic ribosomes host PKC activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 376:65–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bhoumik A, Jones N, Ronai Z. 2004. Transcriptional switch by activating transcription factor 2-derived peptide sensitizes melanoma cells to apoptosis and inhibits their tumorigenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:4222–4227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arimoto K, Fukuda H, Imajoh-Ohmi S, Saito H, Takekawa M. 2008. Formation of stress granules inhibits apoptosis by suppressing stress-responsive MAPK pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 10:1324–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gandin V, Miluzio A, Barbieri AM, Beugnet A, Kiyokawa H, Marchisio PC, Biffo S. 2008. Eukaryotic initiation factor 6 is rate-limiting in translation, growth, and transformation. Nature 455:684–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laine A, Topisirovic I, Zhai D, Reed JC, Borden KL, Ronai Z. 2006. Regulation of p53 localization and activity by Ubc13. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:8901–8913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chamberlain JP. 1979. Fluorographic detection of radioactivity in polyacrylamide gels with the water-soluble fluor, sodium salicylate. Anal. Biochem. 98:132–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kieft JS, Zhou K, Jubin R, Doudna JA. 2001. Mechanism of ribosome recruitment by hepatitis C IRES RNA. RNA 7:194–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grosso S, Volta V, Sala LA, Vietri M, Marchisio PC, Ron D, Biffo S. 2008. PKCβII modulates translation independently from mTOR and through RACK1. Biochem. J. 415:77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lopez-Bergami P, Habelhah H, Bhoumik A, Zhang W, Wang LH, Ronai Z. 2005. RACK1 mediates activation of JNK by protein kinase C. Mol. Cell 19:309–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Werlen G, Jacinto E, Xia Y, Karin M. 1998. Calcineurin preferentially synergizes with PKC-theta to activate JNK and IL-2 promoter in T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 17:3101–3111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lopez-Bergami P, Ronai Z. 2008. Requirements for PKC-augmented JNK activation by MKK4/7. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40:1055–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fuchs SY, Tappin I, Ronai Z. 2000. Stability of the ATF2 transcription factor is regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:12560–12564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu J, Lin A. 2005. Role of JNK activation in apoptosis: a double-edged sword. Cell Res. 15:36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sengupta J, Nilsson J, Gursky R, Spahn CM, Nissen P, Frank J. 2004. Identification of the versatile scaffold protein RACK1 on the eukaryotic ribosome by cryo-EM. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:957–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu Y, Ji H, Doudna JA, Leary JA. 2005. Mass spectrometric analysis of the human 40S ribosomal subunit: native and HCV IRES-bound complexes. Protein Sci. 14:1438–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Coyle SM, Gilbert WV, Doudna JA. 2009. Direct link between RACK1 function and localization at the ribosome in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29:1626–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wojtaszek PA, Heasley LE, Siriwardana G, Berl T. 1998. Dominant-negative c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 2 sensitizes renal inner medullary collecting duct cells to hypertonicity-induced lethality independent of organic osmolyte transport. J. Biol. Chem. 273:800–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Derijard B, Hibi M, Wu IH, Barrett T, Su B, Deng T, Karin M, Davis RJ. 1994. JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell 76:1025–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wu S, Hu Y, Wang JL, Chatterjee M, Shi Y, Kaufman RJ. 2002. Ultraviolet light inhibits translation through activation of the unfolded protein response kinase PERK in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18077–18083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rabl J, Leibundgut M, Ataide SF, Haag A, Ban N. 2011. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic 40S ribosomal subunit in complex with initiation factor 1. Science 331:730–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mateyak MK, Kinzy TG. 2010. eEF1A: thinking outside the ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 285:21209–21213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. 2010. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:113–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Alkalaeva EZ, Pisarev AV, Frolova LY, Kisselev LL, Pestova TV. 2006. In vitro reconstitution of eukaryotic translation reveals cooperativity between release factors eRF1 and eRF3. Cell 125:1125–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eggers DK, Welch WJ, Hansen WJ. 1997. Complexes between nascent polypeptides and their molecular chaperones in the cytosol of mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:1559–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Perry RP, Kelley DE. 1968. Messenger RNA-protein complexes and newly synthesized ribosomal subunits: analysis of free particles and components of polyribosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 35:37–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. 2009. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:537–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rosenzweig R, Osmulski PA, Gaczynska M, Glickman MH. 2008. The central unit within the 19S regulatory particle of the proteasome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:573–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ye Y, Meyer HH, Rapoport TA. 2001. The AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97 and its partners transport proteins from the ER into the cytosol. Nature 414:652–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rabinovich E, Kerem A, Frohlich KU, Diamant N, Bar-Nun S. 2002. AAA-ATPase p97/Cdc48p, a cytosolic chaperone required for endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:626–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kuroha K, Akamatsu M, Dimitrova L, Ito T, Kato Y, Shirahige K, Inada T. 2010. Receptor for activated C kinase 1 stimulates nascent polypeptide-dependent translation arrest. EMBO Rep. 11:956–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Steitz TA. 2008. A structural understanding of the dynamic ribosome machine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:242–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. 2010. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 475:324–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gonen H, Smith CE, Siegel NR, Kahana C, Merrick WC, Chakraburtty K, Schwartz AL, Ciechanover A. 1994. Protein synthesis elongation factor EF-1α is essential for ubiquitin-dependent degradation of certain N alpha-acetylated proteins and may be substituted for by the bacterial elongation factor EF-Tu. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:7648–7652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ametzazurra A, Larrea E, Civeira MP, Prieto J, Aldabe R. 2008. Implication of human N-α-acetyltransferase 5 in cellular proliferation and carcinogenesis. Oncogene 27:7296–7306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]