Abstract

PGC-1α is a key transcription coactivator regulating energy metabolism in a tissue-specific manner. PGC-1α expression is tightly regulated, it is a highly labile protein, and it interacts with various proteins—the known attributes of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). In this study, we characterize PGC-1α as an IDP and demonstrate that it is susceptible to 20S proteasomal degradation by default. We further demonstrate that PGC-1α degradation is inhibited by NQO1, a 20S gatekeeper protein. NQO1 binds and protects PGC-1α from degradation in an NADH-dependent manner. Using different cellular physiological settings, we also demonstrate that NQO1-mediated PGC-1α protection plays an important role in controlling both basal and physiologically induced PGC-1α protein level and activity. Our findings link NQO1, a cellular redox sensor, to the metabolite-sensing network that tunes PGC-1α expression and activity in regulating energy metabolism.

INTRODUCTION

The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α is a broad and powerful regulator of many metabolic programs, particularly mitochondrial biogenesis, functioning in a tissue-specific manner. In muscles, for instance, PGC-1α coactivates genes that promote glucose clearance and fiber-type switching and improves mitochondrial oxidative capacity (1–3). In hepatocytes, PGC-1α coactivates gluconeogenic genes and genes involved in fatty acid oxidation (4–6). In adipocytes, PGC-1α induces mitochondrial biogenesis and adaptive thermogenesis (7). In neurons and vascular endothelial cells, PGC-1α protects against oxidative damage by activating antioxidant genes (8, 9). Recently, deactivation of the PGC-1α axis was linked to telomerase dysfunction, connecting the nuclear and mitochondrial aging processes with metabolism (10). Indeed, misregulation of PGC-1α levels has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several diseases, including diabetes, obesity, heart diseases, and neurological disorders (11–16). Understanding how cellular PGC-1α levels are regulated is, therefore, of great interest.

PGC-1α responds to diverse nutritional and physiological stimuli, and its expression and activity are dynamically controlled. At the mRNA level, PGC-1α gene expression is induced by CREB, MEF2, and ATF2 and can also be induced by PGC-1α itself, establishing an autoregulatory loop (4, 17, 18). Posttranslational modifications also play an important role in regulating PGC-1α expression and function. These include, for instance, phosphorylation of PGC-1α by AMPK (19), which primes PGC-1α for deacetylation by Sirt1 (20, 21), leading to a more stable and active protein. Another important determinant in controlling PGC-1α steady-state levels is the process of protein degradation. As with many regulatory factors, PGC-1α protein has an extremely short half-life. Recently, several groups demonstrated that PGC-1α is a substrate for degradation by the proteasome, in part through the ubiquitin system (22–26).

We have recently discovered a new process of proteasomal degradation that is ubiquitin independent, which was named “degradation by default,” and can be executed by the 20S proteasome catalytic particle (20S PC) (27, 28). Given the absence of the 19S proteasomal regulatory particle (19S RP), this degradation process has no protein-unfolding activity and therefore is applicable mainly to intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). These proteins in isolation lack any well-defined secondary and/or tertiary structure, either entirely or in parts. IDPs hence have a flexible surface allowing interaction with numerous partners and complexes (29–31).

An important property of PGC-1α is that it is highly versatile. PGC-1α binds a large set of transcription factors and coactivating complexes through distinct regions of the protein, enabling it to regulate various metabolic processes. These include peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARγ), PPARα, nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF-1), estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRα), MEF2C, GCN5, SRC1, and CBP/p300, among others (32–34). The docking interface for these interacting proteins appears to be distributed throughout the length of PGC-1α. Taken together, these properties led us to propose that PGC-1α is an IDP and to examine whether it is regulated by degradation by default.

An important regulator of degradation by default is the flavoprotein NADH quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). Dysregulation of NQO1 expression and activity was previously linked to dysregulated metabolism (35–38). NQO1 is physically associated with the 20S PC, where it plays a gatekeeper function and inhibits degradation (39, 40). NQO1 binds and protects a number of proteins, all predicted to be at least partially disordered. These include p53, c-fos, C/EBPα, p63, p33, p73α, and ODC (41–46). In addition, the yeast orthologue of human NQO1, Lot6, was recently reported to be associated with the yeast 20S PC and to regulate degradation in a redox-dependent manner (47).

In this study, we demonstrate that PGC-1α is an IDP by prediction and by susceptibility to the 20S proteasomal degradation. The 20S PC gatekeeper NQO1 inhibits PGC-1α proteasomal degradation and binds PGC-1α in an NADH-dependent manner. We further show that NQO1 determines PGC-1α basal levels in muscle and PGC-1α-induced levels in liver cells. The requirement of NADH binding to NQO1 for its function in protecting PGC-1α degradation and the direct effect of NQO1 on the redox state of the cell attribute to NQO1 a role in the emerging metabolite-sensing network regulating PGC-1α expression and activity (14).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro experiments.

In vitro translation was performed using the TNT quick coupled transcription-translation system (Promega), using 35S-labeled methionine. In vitro degradation using purified 20S proteasomes was carried out as described previously (39).

Cell culture, plasmids, and transfection.

HEK-293, HEK-293T, and HepG2 cell lines were grown and maintained as previously described (48). C2C12 myoblasts were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 10% CO2. The plasmids employed were as follows: pSV HA-PGC-1α, pCDNA flag-PGC-1α (can be purchased via Addgene), pLenti6 PGC-1α pCDNA3 EGFP, pCDNA3 EGFP-PGC-1α, pEFIRES-NQO1, pCDNA3 NQO1/Y128V/Y128F, and pCDNA3 HA-p73β. Transient transfections were carried out by the calcium phosphate method.

Cycloheximide half-life experiment.

The cycloheximide half-life experiment was performed as described previously (22).

Coimmunoprecipitation and protein analysis.

Coimmunoprecipitation was performed using antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) or anti-Flag-agarose beads (Sigma) or by incubating the extracts with rabbit polyclonal antibody against PGC-1α (H-300; Santa Cruz) for 3 h and then incubating them with protein A/G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz) for an additional 2 h. NADH (1 mM) was added to the extraction buffer. Protein extraction and immunoblotting were done as previously described (48). The antibodies used were as follows: monoclonal mouse antiactin, anti-HA, anti-Flag (Sigma), mouse anti-NQO1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-PGC-1α (Calbiochem), polyclonal goat anti-NQO1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), polyclonal goat anti-NQO1 (ab2346; Abcam), and polyclonal rabbit anti-acetylated-Lys (9441; Cell Signaling).

Primary hepatocyte isolation.

Primary mouse hepatocytes were isolated as described previously (49) by collagen perfusion and Percoll gradient purification. For hormonal treatment, hepatocytes were cultured for 20 h in minimal medium (DMEM with 0.2% bovine serum albumin [BSA] and 2 mM sodium pyruvate) and then treated with 1 mM dexamethasone and 10 mM forskolin or with glucagon for different time points.

Primary muscle isolation.

Primary myoblasts were obtained from C57 black (3- to 4-week-old) mice as previously described (50). In brief, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and gastrocnemius muscles were carefully removed. Myofibers were separated using collagenase I (Sigma-Aldrich). Fibers were grown in proliferation medium (Bio-AMF; Biological Industries, Ltd.) for 3 days on Matrigel (BD Bioscience)-treated plates. Delaminated primary myoblasts were enriched by preplating as follows: cells were removed using trypsin C (Biological Industries) and grown in proliferation medium on untreated plates for 1 h. The medium, containing the nonadherent cells, was transferred to a Matrigel-treated plate. The preplating step was repeated three times. Primary myoblasts were induced to differentiate by replacing the proliferation medium with differentiation medium (DMEM containing 4% horse serum).

Lentivirus infection.

C2C12 myoblasts were infected with an equal titer of lentiviruses expressing nontargeting short hairpin RNA (shRNA) control or NQO1 shRNA. Twenty-four hours postinfection, 3 μg/ml puromycin was added for an additional 4 days to select for the infected cells. Lentivirus-based shRNA clones were purchased from Sigma (Mission shRNA). From five different clones available for targeting NQO1 mRNA, we chose NM_008706.1-416s1c1, which was the most efficient.

Adenovirus infection.

Primary mouse hepatocytes were infected 24 h after plating with adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) or NQO1. Adenoviruses were made based on the AdEasy system (51).

Analysis of gene expression.

Total RNA was isolated from cells by using Tri reagent (Molecular Research Center). RNA was treated with DNase I, and 1 μg was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA kit (Bio-Rad). cDNA was amplified and quantified with the Roche Light Cycler 480 system using Sybr green (Kapa Biosystems). Gene expression levels were normalized to the geometric mean of either three housekeeping genes, TATA binding protein (TBP), hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), or actin and expressed relative to control using the threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method. A table containing the sequence of the primers is available in the supplemental material.

Animal experiments.

The Weizmann Institute Animal Care and Use Committee approved all studies in mice. C57 black male mice, 8 to 10 weeks old, were fasted for different time points which started at zero time = 12 (t = 0, beginning of the dark phase); were sacrificed at t = 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18; and were compared to mice that were fed ad libitum and sacrificed at the end of the experiment (t = 18). Dicoumarol was dissolved in 150 mM NaOH to make a stock solution (16.8 g/liter). An injection solution was made in 0.9% NaCl and was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) (35 mg/kg of body weight). Vehicle alone was used as a control for the injection. Immediately after injection, mice were fed ad libitum or fasted for 7 or 16 h during the night. Blood glucose was measured in tail blood using a standard glucometer. Serum insulin was measured using a kit (ultrasensitive mouse insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] kit; Crystal Chem Inc.) Liver samples were collected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

NADH and NAD+ measurements.

For liver tissue, we used the NAD+/NADH quantification kit from BioVision according to the manufacturer's instructions, including filtering the samples through 10-kDa-molecular-mass-cutoff filters.

For cultured cells, we used a method based on enzymatic cycling reactions, which we developed based on a previously described protocol (52), and on a commercial kit protocol from Cyclex. For NADH measurements, cells were extracted with a basic buffer (50 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA) and vortexing and sonication. Then, they were incubated at 60°C and neutralized with 0.3 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.8). After 10 min on ice, the extract was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was used to determine the NADH concentration. For NAD+ measurements, a parallel cell pellet was extracted using an acidic buffer (0.5 M HClO4) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Then, the extract was neutralized with 0.8 M Na2CO3 and was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was used to determine the NAD+ concentration. The cycling reaction was done in a final reaction volume of 200 μl. The cycling buffer contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, freshly added 120 μM resazurin, and 3 mM sodium lactate. The reaction was initiated using 0.5 units of diaphorase and 3 units of lactate dehydrogenase. Standard curves for NADH and NAD were prepared and measured along with all the samples simultaneously. The increase in the resazurin fluorescence (excitation at 560 nm and emission at 590 nm) was measured continuously using a fluorescent plate reader. Values for both NADH and NAD+ were detected within a linear range (3 biological replicates, with each having 3 technical replicates).

Statistics.

Error bars in the figures correspond to standard deviations (SDs) from at least 3 individual experiments (biological triplicates). Statistical significance was assessed by two-tailed Student's t tests assuming unequal variances.

RESULTS

PGC-1α is an intrinsically disordered protein susceptible to degradation by the 20S PC and protected by NQO1.

We analyzed the primary sequence of PGC-1α by two different IDP prediction programs. Both FoldIndex (Fig. 1A) and PONDR (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material) algorithms scored PGC-1α as an unfolded/disordered protein, whereas as expected, they scored the well-structured protein PCNA (53) as a folded/ordered protein. In addition, charged-hydropathy analysis applied to the PONDR predictions placed PGC-1α to the left of a boundary (see Fig. S1B), indicating that PGC-1α is a putative disordered protein. The fact that PGC-1α migrates slower than expected in SDS-PAGE gels (see Fig. S1C) further supports this prediction. This slow migration is due to the unique amino acid composition that causes IDPs to bind less SDS than do naturally folded proteins (54). In addition, these observations further support a previous report that the N-terminal domain of PGC-1α has limited secondary and no defined tertiary structure (55).

Fig 1.

PGC-1α is an intrinsically disordered protein by prediction, susceptible to in vitro degradation by the 20S PC and protected by NQO1. (A) Analysis of PGC-1α and PCNA amino acid sequences by the FoldIndex prediction program. (B) In vitro-transcribed and -translated [35S]methionine-labeled PGC-1α and PCNA proteins were incubated with or without purified 20S PC for the indicated time points. Immediately after incubation, the mixture was subjected to analysis by SDS-PAGE. (C) In vitro-transcribed and -translated [35S]methionine-labeled PGC-1α was incubated with purified 20S PC with or without recombinant NQO1 protein for the indicated time periods. Immediately after incubation, the extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Disordered regions can be degraded by the latent 20S PC (56), and we further characterized this susceptibility to 20S PC degradation as a more general operational definition for IDPs (57, 58). Therefore, to experimentally validate the IDP nature of PGC-1α, we used the 20S proteasomal degradation assay. To this end, 35S-labeled PGC-1α and the control PCNA proteins were incubated with purified 20S PC. Indeed, PGC-1α was readily degraded, whereas the well-folded PCNA remained intact even after 60 min (Fig. 1B). NQO1 is physically associated with the 20S PC, where it plays a gatekeeper function and inhibits degradation by default (39, 40). To examine whether NQO1 protects PGC-1α degradation by the 20S PC, we added NQO1 to the in vitro degradation reaction. NQO1 inhibited PGC-1α degradation under short incubation times, up to 30 min (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results suggest that PGC-1α is susceptible to 20S PC-mediated degradation and protected by NQO1.

PGC-1α degradation by default is inhibited by NQO1.

IDPs undergo ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation in the cells, degradation by default. In certain cases, however, this process is inhibited by NQO1 (27, 28, 59). To investigate whether PGC-1α undergoes similar processes of degradation and inhibition, we generated a stable cell line expressing Flag-tagged β4, a 20S PC subunit, to immunoprecipitate proteasomes. Under treatment with MG132, a proteasomal inhibitor, PGC-1α was coimmunoprecipitated with the tagged proteasome (Fig. 2A). PGC-1α–proteasome association was also observed under NQO1 overexpression (Fig. 2A). NQO1 was also coimmunoprecipitated with the tagged proteasome, consistent with its role as a 20S PC gatekeeper to inhibit PGC-1α degradation in the cells. MG132 treatment resulted in PGC-1α aggregation and accumulation in the nuclear pellet (Fig. 2B), as has been reported elsewhere (25). Interestingly, IDPs in excess tend to collapse into insoluble aggregates (60). This behavior was recapitulated by NQO1 overexpression (Fig. 2B), supporting the possibility that NQO1 inhibits PGC-1α proteasomal degradation.

Fig 2.

NQO1 inhibits PGC-1α proteasomal degradation and increases its protein half-life. (A) HEK-293T cells and HEK-293T cells stably expressing the Flag-tagged β4 (PSMB2) ring subunit were transiently transfected with untagged PGC-1α- or NQO1-expressing vectors as indicated. Treatment with 25 μM MG132 was done 48 h postinfection, and cells were incubated for 2 h. Then, cells were harvested for immunoprecipitation (IP) using Flag beads. Analysis of the α3 (PSMA4) ring subunit indicates that the intact proteasome chamber was immunoprecipitated. (B) Flag-tagged PGC-1α was overexpressed in HEK-293 cells alone or together with an NQO1 expression vector. Cells were treated 24 h later with 25 μM MG132 for 3 or 6 h as indicated, after which cells from all points were harvested for protein analysis. (C) HEK-293T cells were transfected as indicated. GFP was cotransfected as a transfection and loading control. Cycloheximide (CHX) was added to the cells 48 h posttransfection, and cells were treated for the indicated time periods. MG132 (25 μM) was added together with CHX at the last time point where PGC-1α was expressed alone. S.E, short exposure; L.E, long exposure. The dashed line indicates an area in the final image in which an irrelevant lane was omitted. (D) HEK-293T cells were transfected as indicated. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated using Flag beads and immunoblotted with anti-HA to visualize polyubiquitination. (E) Quantification of the ratio between polyubiquitinated PGC-1α ladder and PGC-1α from 3 independent biological triplicates.

We next examined whether NQO1 is sufficient to increase the PGC-1α protein half-life. To this end, we treated the cells with cycloheximide to inhibit protein translation and followed PGC-1α protein decay. Transfected Flag-tagged PGC-1α had a very short half-life of about 30 min (Fig. 2C), as expected from a highly labile protein (22). Coexpression of NQO1, however, resulted in a robust increase in the PGC-1α half-life (Fig. 2C). However, this should be cautiously treated given the tendency of accumulated PGC-1α under NQO1 overexpression to aggregate to a certain level. Addition of MG132 blocked PGC-1α decay, validating the involvement of proteasomes in this process. PGC-1α mRNA quantification under these conditions showed that the effect of NQO1 was not mediated by increased transcription (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Furthermore, NQO1 had no detectable effect on protein translation because a similar amount of [35S]methionine was incorporated into the total proteins and specifically to PGC-1α protein after a short pulse (see Fig. S2B). These results suggest that NQO1 increases PGC-1α half-life by protecting its 20S PC degradation by default.

To exclude the possibility that NQO1 supports PGC-1α accumulation via inhibition of ubiquitination of PGC-1α, we coexpressed an octameric tandem fusion of HA-tagged ubiquitin together with Flag-tagged PGC-1α with or without NQO1 and analyzed the pattern of the polyubiquitinated PGC-1α ladder. PGC-1α ubiquitination was not inhibited by NQO1 (Fig. 2D). Inhibition of degradation by default by NQO1 increases the basal IDP level (59); however, the accumulated protein is expected to be degraded via the ubiquitination pathway. Indeed, the ratios between the amounts of polyubiquitinated PGC-1α ladder and PGC-1α in the presence and absence of NQO1 remained similar (Fig. 2E). This suggests that the basal PGC-1α level is regulated by NQO1 via inhibiting the process of PGC-1α degradation by default and not degradation via the ubiquitination pathway.

NQO1 binds and protects PGC-1α in an NADH-dependent manner.

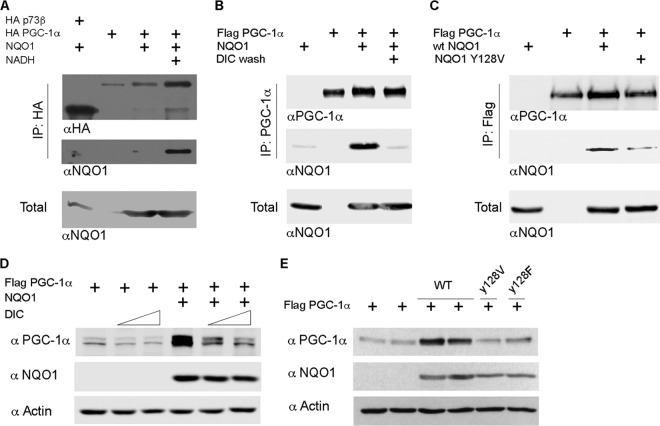

NQO1 binds some of its client proteins in an NADH-dependent manner (39). We therefore asked whether PGC-1α and NQO1 interact and whether this process requires NADH. To this end, we utilized both genetic and pharmacological approaches. Transfection experiments followed by a coimmunoprecipitation assay revealed that PGC-1α and NQO1 formed a complex and that this interaction was markedly augmented in the presence of NADH (Fig. 3A). The p73β isoform known not to bind NQO1 (39) served as a negative control. As a reciprocal approach, we used dicoumarol, a drug that competes with NADH in binding to NQO1 (61). Washing the immunoprecipitated NQO1/PGC-1α complex with dicoumarol resulted in detachment of NQO1 from the complex, as it was no longer detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 3B). Next, we examined the ability of PGC-1α to bind the NQO1-Y128V mutant that has a reduced NADH-binding capacity (62). This mutant only poorly interacted with PGC-1α and failed to support PGC-1a accumulation, compared to wild-type NQO1 (Fig. 3C). These results demonstrate that NQO1 and PGC-1α interact in an NADH-dependent manner.

Fig 3.

NQO1 protects PGC-1α by NADH-dependent interaction. (A) HEK-293 cells were transfected as indicated and harvested for analysis 24 h posttransfection. HA beads were used to immunoprecipitate (IP) HA-tagged PGC-1α, whereas HA-p73β served as a negative control for the binding to NQO1. Where indicated, 1 mM NADH was added to the extraction buffer. (B) HEK-293 cells were transfected as indicated and harvested for analysis 24 h posttransfection. A/G beads conjugated to PGC-1α antibody (H-300) were used to immunoprecipitate Flag–PGC-1α. Dicoumarol (DIC; 150 μM) was added to the last two wash steps. (C) HEK-293T cells were transfected as indicated and harvested 24 h later. Flag beads were used to immunoprecipitate Flag-tagged PGC-1α. wt, wild type. (D) Flag-tagged PGC-1α was expressed in HEK-293 cells alone or together with NQO1. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, the cells were treated with dicoumarol (100 and 150 μM) for an additional 2 h, after which cells were harvested for protein analysis. (E) Flag-tagged PGC-1α was expressed in HEK-293 cells alone (2 individual transfections) or together with either wild-type NQO1 (WT; 2 individual transfections) or 2 different NQO1 mutants (Y128V and Y128F). Protein expression was analyzed 24 h posttransfection.

Treating the cells with dicoumarol inhibited the NQO1-mediated accumulation of PGC-1α in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D). The effect of dicoumarol was specific and NQO1 dependent, since in the absence of NQO1, the PGC-1α level was only marginally affected. Here again, both NQO1 mutants with reduced NADH-binding capacity, Y128F and Y128V, failed to support PGC-1α accumulation (Fig. 3E). These findings suggest that NADH-dependent binding of NQO1 to PGC-1α supported PGC-1α accumulation in the cells.

PGC-1α protein level in muscle cells correlates with NQO1 expression.

To investigate the physiological relevance of accumulation of PGC-1α by NQO1, we used the myoblast C2C12 cell line, which proved useful in studying PGC-1α activity. We followed endogenous NQO1 and PGC-1α protein levels in C2C12 mouse myoblasts through the differentiation to myotubes. Interestingly, the levels of both proteins gradually declined as the cells were differentiated (Fig. 4A). Similar results were obtained with mouse primary satellite myoblasts (Fig. 4B). Bortezomib, a proteasomal inhibitor, led to PGC-1α accumulation in both myoblasts and differentiated myotubes (Fig. 4C), suggesting that PGC-1α is downregulated, at least in part, by proteasomal degradation. Notably, the fold of bortezomib-mediated accumulation was higher at day 3 of differentiation than in myoblasts. These data suggest that at this stage of differentiation, where NQO1 was very low, PGC-1α was intensively degraded.

Fig 4.

NQO1 and PGC-1α steady-state levels in myoblasts and myotubes. (A) Analysis of PGC-1α and NQO1 protein and mRNA levels in C2C12 myoblast (MB) cells and at sequential days after the cells were put in differentiation medium. (B) Same as for panel A, except that the analysis was done in primary mouse muscle cells. (C) Bortezomib (1 μM) was added 12 h before harvesting to primary mouse muscle cells either grown in growth medium as myoblasts (MB) or grown in differentiation medium for 1, 2, or 3 days. Due to the effect of proteasome inhibition on PGC-1α solubility (see above), in order to obtain the total amount of PGC-1α we analyzed the soluble and insoluble fractions together as the total. (Left) Quantification of total PGC-1α from bortezomib-treated cells relative to total PGC-1α from untreated cells. (Right) Western blot analysis. (D) Protein extracts obtained from extensor digitorum longus (EDL), soleus (SOL), and gastrocnemius (GAS) of an 8-week-old male C57 black mouse and subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was used to detect PGC-1α protein. IB, immunoblotting.

We further examined PGC-1α and NQO1 expression levels in slow- and fast-twitch muscle tissues. Although the mRNA levels of PGC-1α were similar in the two types (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material), its protein level was much higher in soleus (SOL), a slow-twitch oxidative muscle, than in extensor digitorum longus (EDL), a fast-twitch glycolytic muscle (Fig. 4D), consistent with previous findings (21). Interestingly, both mRNA and protein levels of NQO1 were much higher in SOL than in EDL and gastrocnemius (Fig. 4D; see Fig. S3B). These results highlight a direct correlation between PGC-1α and NQO1 protein levels in muscle cells under different physiological conditions.

NQO1 knockdown in C2C12 myoblasts results in reduced PGC-1α protein level and activity.

To validate the role of NQO1 in regulating endogenous PGC-1α levels, we knocked down NQO1 in C2C12 myoblasts, and a 2-fold reduction in PGC-1α protein level was obtained (Fig. 5A). Remarkably, however, knocking down NQO1 resulted in increased PGC-1α mRNA levels (Fig. 5B), which in the long run may compensate for the reduction at the protein level. Indeed, several days after the induction of NQO1 knockdown, PGC-1α protein level was resumed (data not shown). Interestingly, this opposite behavior of a decrease in PGC-1α protein level but an increase in its mRNA levels was reminiscent of what was observed during the myotube differentiation, where NQO1 expression was low, both in C2C12 myoblasts (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material) and in mouse primary satellite myoblasts (see Fig. S4B). These data suggest that, at least in muscle cells, NQO1 has an opposite role in regulating PGC-1α protein and mRNA levels.

Fig 5.

NQO1 knockdown in myoblasts reduces steady-state PGC-1α protein levels and activity. (A) NQO1 was knocked down in C2C12 cells using a lentivirus-based approach (3 individual experiments); all were run on the same gel, and cells were analyzed for NQO1 and PGC-1α protein expression. The right panel represents quantification of PGC-1α protein. (B) PGC-1α mRNA expression level was analyzed from C2C12 cells as described for panel A. (C) NADH and NAD+ content measured from basic and acidic extracts obtained from freshly prepared control (Non-targeting) and NQO1 knockdown (KD) C2C12 cells. (D) mRNA expression analysis of different genes from freshly prepared control (Non-targeting) and NQO1 knockdown (KD) C2C12 cells.

The NAD+/NADH ratio decreases as muscle cells differentiate (63). Sirt1 deacetylation of PGC-1α plays an important step in its activation and is driven by NAD+ levels (20). NQO1 is a multifunctional protein that participates directly in NADH redox reaction, converting NADH to NAD+ (64). Interestingly, we observed a significant reduction in the NAD+/NADH ratio in NQO1 knockdown compared to control myoblasts (Fig. 5C). Moreover, overexpression of NQO1 in HEK-293 cells increased the NAD+/NADH ratio in a manner that was dependent on NQO1 integrity, as the NQO1 Y128F mutant, which does not bind NADH, did not affect this ratio (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Under NQO1 depletion, the low PGC-1α level was efficiently acetylated (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material), possibly due to the fact that low NQO1 gives rise to less NADH consumption (low NAD/NADH ratio). The PGC-1α acetylation level under NQO1 depletion was similar to that in control C2C12 cells treated with nicotinamide (NAM), a histone deacetylase inhibitor (65). These data suggest that NQO1 also facilitates PGC-1α activity via increasing the NAD level, which in turn supports the Sirt1 function in deacetylating PGC-1α.

Next, we examined the effect of NQO1 knockdown on the expression level of PGC-1α target genes involved in mitochondrial and energy metabolism. The data revealed that NQO1 knockdown significantly attenuated the expression of cytochrome c (CytoC), cytochrome c oxidase IV (Cox4), carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 muscle isoform (CPT-1β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) genes (Fig. 5D). The expression of the myogenic markers Pax7 and Myf5 was not affected by NQO1 knockdown, and these served as internal controls. These results suggest that NQO1 regulates PGC-1α protein level and activity through inhibiting degradation by default and increasing the NAD/NADH ratio.

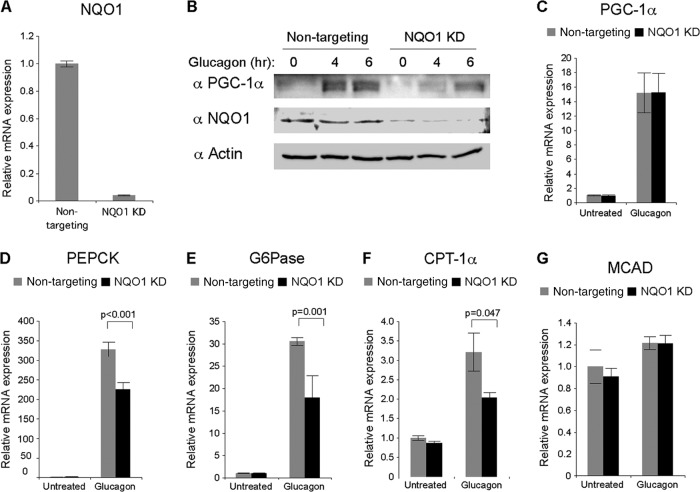

NQO1 supports PGC-1α accumulation and gluconeogenic response in primary hepatocytes.

Treating primary hepatocytes with the fasting-induced hormone glucagon (4, 66, 67) results in accumulation of PGC-1α protein that otherwise is barely detectable (6). We therefore used this approach to investigate the role of NQO1 in the induction of endogenous PGC-1α. We knocked down NQO1 using adenoviruses expressing either NQO1-specific or control shRNAs (Fig. 6A). Under these conditions, PGC-1α failed to accumulate to the levels obtained in the control cells (Fig. 6B). mRNA expression analysis ruled out differences at the PGC-1α mRNA level (Fig. 6C), suggesting that NQO1 is required for a higher level of PGC-1α protein accumulation in mouse primary hepatocytes.

Fig 6.

NQO1 regulates PGC-1α accumulation in response to induction by starvation-mimicking conditions in mouse primary hepatocytes. (A) Primary hepatocytes were infected with either GFP- or NQO1-expressing adenoviruses. Expression levels of NQO1 mRNA were analyzed 48 h postinfection to verify the efficiency of the knockdown. (B) Same as in panel A. Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were treated with 25 nM glucagon for either 4 or 6 h. Protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting. (C) Same as in panel B. Expression levels of PGC-1α mRNA were analyzed 4 h after addition of glucagon. (D to G) Same as in panel B. Expression levels of PEPCK (D), G6Pase (E), CPT-1α (F), and MCAD (G) mRNA were analyzed 4 h after addition of glucagon.

Next, we asked whether the reduced accumulation of PGC-1α protein in NQO1 knockdown cells would attenuate the PGC-1α-mediated gluconeogenic program. Remarkably, PGC-1α-mediated induction of two rate-limiting enzymes of gluconeogenesis, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase), and of a rate-limiting enzyme of β oxidation, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 alpha (CPT-1α), was significantly attenuated in NQO1 knockdown cells (Fig. 6D, E, and F). The mRNA expression of medium-chain acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) dehydrogenase (MCAD) was not induced by glucagon in agreement with a previous report, and this is explained by the lack of induction of some other hormone receptors (68). Notably, NQO1 knockdown did not affect MCAD mRNA levels (Fig. 6G), suggesting the specific impaired induction of genes that are activated by PGC-1α stimulation. Taken together, these results suggest that accumulation of functional PGC-1α is regulated by NQO1 under inducing conditions in primary hepatocytes.

Pharmacologic inhibition of NQO1 attenuates fasting-induced PGC-1α accumulation in mouse liver.

To address the physiological context in which NQO1-mediated regulation of PGC-1α is expected to be important, we examined liver under a fasting regimen. The liver PGC-1α level is relatively low in the fed state but is robustly elevated in response to fasting (5). In addition, the liver exhibits major changes in its redox state during fasting (69). We performed a time course experiment in which we examined changes in liver NQO1 and PGC-1α expression during short intervals of fasting periods starting in the dark phase and compared it to that for mice fed ad libitum and sacrificed during the light phase. The NQO1 protein level did not change much during fasting (see Fig. S7A in the supplemental material), nor did its mRNA levels change (see Fig. S7B). Interestingly, PGC-1α showed two phases of induction, at both the protein (see Fig. S7A) and the mRNA (see Fig. S7B) levels after short-term and during long-term fasting. We quantified the NADH and NAD+ levels and found that the NAD+/NADH ratio increased after long-term fasting (Fig. 7A) in agreement with reported findings (20). Moreover, while NAD+ levels gradually increased over the time of fasting, during short-term fasting there was a peak increase in the NADH levels (Fig. 7A). We hypothesized that, during short-term starvation when NADH levels transiently increase, NQO1 becomes important in protecting PGC-1α. To test this hypothesis, we used a pharmacologic approach and injected mice intraperitoneally with dicoumarol to inhibit NQO1 activity and subjected them to short-term starvation during the night phase. In the control groups that were injected with only the vehicle, an increase in PGC-1α protein was observed 6 h after food deprivation (Fig. 7B). However, the accumulation of PGC-1α protein following starvation was lower in the dicoumarol-injected mice (Fig. 7B). Given the PGC-1α role in glucose homeostasis, we also quantified blood glucose levels. As expected, there was a decrease in the blood glucose level in the control fasting mice (Fig. 7C). The dicoumarol-injected mice, however, developed mild hypoglycemia after 16 h of fasting. The insulin signaling pathway has been shown to negatively regulate PGC-1α induction (70, 71). Insulin measurements revealed that plasma insulin concentration was refractory to dicoumarol treatment (Fig. 7D), ruling out an indirect insulin effect. These results suggest that pharmacologic inhibition of NQO1 can lead to reduced activation of liver PGC-1α in response to fasting.

Fig 7.

A role for NQO1 activity in regulating PGC-1α in fasting liver. (A) Mice were either fed ad libitum or fasted during the indicated time points (starting from the beginning of the night phase) and then sacrificed for hepatic analysis of NADH and NAD+ content. (B) Mice were i.p. injected with either dicoumarol (DIC) or vehicle and were divided into groups of feeding and fasting for 7 h (during the night). Immunoprecipitation was used to detect PGC-1α protein. (C) Mice were i.p. injected with either dicoumarol or vehicle and were divided into groups of feeding and fasting for 14 h (during the night). Blood glucose level was measured (n = 5). (D) Insulin measurements from the experiment described for panel C (n = 5).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide evidence for PGC-1α being an IDP candidate that is highly susceptible to the process of proteasomal degradation by default. NQO1, a 20S PC gatekeeper, inhibits degradation by default (27, 28, 40, 47). Here, we show that NQO1 interacts with PGC-1α and inhibits its proteasomal degradation. NQO1 binds NADH in the process of its quinone oxidoreductase activity (72). Interestingly, NADH binding is required for NQO1 to bind and protect PGC-1α from proteasomal degradation. We further provide evidence for NQO1, via regulating the NAD/NADH ratio, as an important regulator of PGC-1α activity. NQO1, therefore, is a new regulator of PGC-1α under both basal and induced conditions in muscle and liver cells, respectively.

Having numerous or large disordered regions can render a protein highly prone to proteolysis (73). This property is ideal for regulatory proteins such as PGC-1α, because increased protein degradation can speed up the response time (74, 75). The intracellular IDP homeostasis is regulated by two main proteasomal degradation pathways: ubiquitin-dependent degradation and degradation by default, which is not mediated by the ubiquitin system. This phenomenon of two distinct phases of proteolysis and its importance in determining the steady-state level of a protein were recently demonstrated for the p53 protein (76). Programming the PGC-1α level demands not only prompt activation of its transcription but also ensuring its proper accumulation. PGC-1α is accumulated when escaping degradation by default, but it remains susceptible to degradation by the conventional ubiquitin system such as that involving the physical interaction and ubiquitination by the SCFCdc4 and RNF34 E3 ligases (22, 26). Interestingly, Cdc4 knockdown only partially blocks PGC-1α degradation. Similarly, RNF34 knockdown, although resulting in elongation of the PGC-1α protein half-life, has only a minor effect on the high rate of PGC-1α degradation kinetics. These data can be explained by the relative contributions of the two degradation pathways, the ubiquitin-dependent pathway and default degradation, to the steady-state level of PGC-1α.

NQO1 inhibited PGC-1α degradation without affecting PGC-1α ubiquitination, suggesting that NQO1 inhibits the default degradation pathway and not the canonical ubiquitin-mediated pathway. After engaging in a functional complex, PGC-1α is less prone to degradation by default. Many partners were reported to bind PGC-1α, and some behave as “nanny proteins,” namely, interacting proteins that enforce a local transient three-dimensional (3D) structure in a manner that presumably would inhibit degradation by the 20S PC. These PGC-1α fractions, however, are subjected to ubiquitin-dependent degradation.

There are several reports that establish a link between metabolic processes and NQO1 activity; however, understanding the underlined molecular mechanism remained a challenge. For instance, systemic in vivo pharmacological stimulation of NQO1 activates genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis and fatty acid oxidation (35). In addition, mice lacking a functional NQO1 gene (NQO1−/−) exhibit altered glucose and fat metabolic pathways compared with wild-type mice. These mice were also found to be hypoglycemic with increased levels of blood lactic and pyruvic acids, both key substrates of gluconeogenesis (36). Therefore, an excess of NQO1 activity results in activation of pathways that are known to be regulated by PGC-1α, while null activity of NQO1 may result in an opposite effect. We therefore propose that NQO1-mediated protection of PGC-1α may provide a good molecular explanation for these phenotypes.

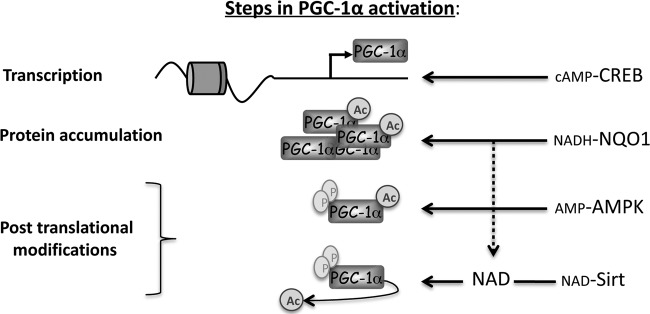

NQO1 can potentially sense a rise in cytosolic NADH and function as a potent stabilizer of PGC-1α, which in turn coactivates genes involved in NADH-consuming metabolic processes, including gluconeogenesis in the cytosol and oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria. The transient rise in NADH that accompanies the initial steps of these processes supports this possibility. During starvation, for instance, in the course of hepatic gluconeogenesis, malate is transported from the mitochondria to the cytosol in order to make oxaloacetate available for the production of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) by cytosolic PEPCK. This process has the effect of moving reducing equivalents in the form of NADH to the cytosol, where they are consumed in proceeding gluconeogenic reactions. During extensive exercise in the course of both fast- and slow-twitch muscle contractions, the availability of oxygen relative to its demand decreases, leading to high glycolytic flux. The increased glycolytic rate is associated with an increase in cytosolic formation of NADH. Therefore, transient formation of NADH can potentiate NQO1 function, which will eventually result in decreasing the NADH/NAD+ ratio, both directly and via activation of NADH-consuming processes through PGC-1α. In support of this model is the finding that NQO1−/− mice have a reduced ratio of NAD+/NADH (36). Furthermore, it was lately shown that an increase in the NAD+/NADH ratio induced by NQO1 results in AMPK activation (77), which subsequently sets the stage for further activation of PGC-1-by the AMPK-Sirt1 axis (21). Overall, our findings provide evidence for an additional layer of complexity in the regulation of PGC-1α expression and activity, which is mediated by NQO1 and the process of degradation by default (Fig. 8).

Fig 8.

Schematic model illustrating the convergent actions of CREB, NQO1, AMPK, and Sirt1 on PGC-1α. The scheme summarizes PGC-1α transcription and posttranslational regulation by different known metabolite-sensing proteins, including NQO1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dina Laznik and Julia Adler for technical assistance.

This study was supported by grant 2007285 from the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation and by grants from the Israel Science Foundation (grant 551/11). Y.S. is the Oscar and Emma Getz Professor. Y.A. was supported by an EMBO short-term fellowship (2009).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 May 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01672-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Baar K, Wende AR, Jones TE, Marison M, Nolte LA, Chen M, Kelly DP, Holloszy JO. 2002. Adaptations of skeletal muscle to exercise: rapid increase in the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. FASEB J. 16:1879–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michael LF, Wu Z, Cheatham RB, Puigserver P, Adelmant G, Lehman JJ, Kelly DP, Spiegelman BM. 2001. Restoration of insulin-sensitive glucose transporter (GLUT4) gene expression in muscle cells by the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:3820–3825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM. 1999. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98:115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herzig S, Long F, Jhala US, Hedrick S, Quinn R, Bauer A, Rudolph D, Schutz G, Yoon C, Puigserver P, Spiegelman B, Montminy M. 2001. CREB regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis through the coactivator PGC-1. Nature 413:179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yoon JC, Puigserver P, Chen G, Donovan J, Wu Z, Rhee J, Adelmant G, Stafford J, Kahn CR, Granner DK, Newgard CB, Spiegelman BM. 2001. Control of hepatic gluconeogenesis through the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Nature 413:131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Estall JL, Kahn M, Cooper MP, Fisher FM, Wu MK, Laznik D, Qu L, Cohen DE, Shulman GI, Spiegelman BM. 2009. Sensitivity of lipid metabolism and insulin signaling to genetic alterations in hepatic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha expression. Diabetes 58:1499–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. 1998. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 92:829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. St-Pierre J, Drori S, Uldry M, Silvaggi JM, Rhee J, Jager S, Handschin C, Zheng K, Lin J, Yang W, Simon DK, Bachoo R, Spiegelman BM. 2006. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and neurodegeneration by the PGC-1 transcriptional coactivators. Cell 127:397–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valle I, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Arza E, Lamas S, Monsalve M. 2005. PGC-1alpha regulates the mitochondrial antioxidant defense system in vascular endothelial cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 66:562–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sahin E, Colla S, Liesa M, Moslehi J, Muller FL, Guo M, Cooper M, Kotton D, Fabian AJ, Walkey C, Maser RS, Tonon G, Foerster F, Xiong R, Wang YA, Shukla SA, Jaskelioff M, Martin ES, Heffernan TP, Protopopov A, Ivanova E, Mahoney JE, Kost-Alimova M, Perry SR, Bronson R, Liao R, Mulligan R, Shirihai OS, Chin L, DePinho RA. 2011. Telomere dysfunction induces metabolic and mitochondrial compromise. Nature 470:359–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finck BN, Kelly DP. 2006. PGC-1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 116:615–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wenz T. 2009. PGC-1alpha activation as a therapeutic approach in mitochondrial disease. IUBMB Life 61:1051–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rona-Voros K, Weydt P. 2010. The role of PGC-1alpha in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Curr. Drug Targets 11:1262–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canto C, Auwerx J. 2009. PGC-1alpha, SIRT1 and AMPK, an energy sensing network that controls energy expenditure. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 20:98–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schilling J, Kelly DP. 2011. The PGC-1 cascade as a therapeutic target for heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 51:578–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qatanani M, Lazar MA. 2007. Mechanisms of obesity-associated insulin resistance: many choices on the menu. Genes Dev. 21:1443–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cao W, Daniel KW, Robidoux J, Puigserver P, Medvedev AV, Bai X, Floering LM, Spiegelman BM, Collins S. 2004. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is the central regulator of cyclic AMP-dependent transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein 1 gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:3057–3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Handschin C, Rhee J, Lin J, Tarr PT, Spiegelman BM. 2003. An autoregulatory loop controls peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha expression in muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:7111–7116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jager S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, Spiegelman BM. 2007. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:12017–12022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. 2005. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature 434:113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, Elliott PJ, Puigserver P, Auwerx J. 2009. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature 458:1056–1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olson BL, Hock MB, Ekholm-Reed S, Wohlschlegel JA, Dev KK, Kralli A, Reed SI. 2008. SCFCdc4 acts antagonistically to the PGC-1alpha transcriptional coactivator by targeting it for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Genes Dev. 22:252–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anderson RM, Barger JL, Edwards MG, Braun KH, O'Connor CE, Prolla TA, Weindruch R. 2008. Dynamic regulation of PGC-1alpha localization and turnover implicates mitochondrial adaptation in calorie restriction and the stress response. Aging Cell 7:101–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trausch-Azar J, Leone TC, Kelly DP, Schwartz AL. 2010. Ubiquitin proteasome dependent degradation of the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha via the N-terminal pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 285:40192–40200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sano M, Tokudome S, Shimizu N, Yoshikawa N, Ogawa C, Shirakawa K, Endo J, Katayama T, Yuasa S, Ieda M, Makino S, Hattori F, Tanaka H, Fukuda K. 2007. Intramolecular control of protein stability, subnuclear compartmentalization, and coactivator function of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 282:25970–25980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wei P, Pan D, Mao C, Wang YX. 2012. RNF34 is a cold-regulated E3 ubiquitin ligase for PGC-1alpha and modulates brown fat cell metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32:266–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Asher G, Reuven N, Shaul Y. 2006. 20S proteasomes and protein degradation “by default.” Bioessays 28:844–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shaul Y, Tsvetkov P, Reuven N. 2010. IDPs and protein degradation in the cell, p 3–36 In Uversky VN, Longhi S. (ed), Instrumental analysis of intrinsically disordered proteins: assessing structure and conformation. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tompa P. 2005. The interplay between structure and function in intrinsically unstructured proteins. FEBS Lett. 579:3346–3354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Uversky VN, Dunker AK. 2010. Understanding protein non-folding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804:1231–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Babu MM, van der Lee R, de Groot NS, Gsponer J. 2011. Intrinsically disordered proteins: regulation and disease. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21:432–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scarpulla RC. 2011. Metabolic control of mitochondrial biogenesis through the PGC-1 family regulatory network. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813:1269–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu C, Lin JD. 2011. PGC-1 coactivators in the control of energy metabolism. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 43:248–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sugden MC, Caton PW, Holness MJ. 2010. PPAR control: it's SIRTainly as easy as PGC. J. Endocrinol. 204:93–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hwang JH, Kim DW, Jo EJ, Kim YK, Jo YS, Park JH, Yoo SK, Park MK, Kwak TH, Kho YL, Han J, Choi HS, Lee SH, Kim JM, Lee I, Kyung T, Jang C, Chung J, Kweon GR, Shong M. 2009. Pharmacological stimulation of NADH oxidation ameliorates obesity and related phenotypes in mice. Diabetes 58:965–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gaikwad A, Long DJ, II, Stringer JL, Jaiswal AK. 2001. In vivo role of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in the regulation of intracellular redox state and accumulation of abdominal adipose tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 276:22559–22564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee JS, Park AH, Lee SH, Kim JH, Yang SJ, Yeom YI, Kwak TH, Lee D, Lee SJ, Lee CH, Kim JM, Kim D. 2012. Beta-lapachone, a modulator of NAD metabolism, prevents health declines in aged mice. PLoS One 7:e47122 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ross D. 2004. Quinone reductases multitasking in the metabolic world. Drug Metab. Rev. 36:639–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Asher G, Tsvetkov P, Kahana C, Shaul Y. 2005. A mechanism of ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation of the tumor suppressors p53 and p73. Genes Dev. 19:316–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moscovitz O, Tsvetkov P, Hazan N, Michaelevski I, Keisar H, Ben-Nissan G, Shaul Y, Sharon M. 2012. A mutually inhibitory feedback loop between the 20S proteasome and its regulator, NQO1. Mol. Cell 47:76–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hershkovitz Rokah O, Shpilberg O, Granot G. 2010. NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase protects TAp63gamma from proteasomal degradation and regulates TAp63gamma-dependent growth arrest. PLoS One 5:e11401 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garate M, Wong RP, Campos EI, Wang Y, Li G. 2008. NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 inhibits the proteasomal degradation of the tumour suppressor p33(ING1b). EMBO Rep. 9:576–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Asher G, Bercovich Z, Tsvetkov P, Shaul Y, Kahana C. 2005. 20S proteasomal degradation of ornithine decarboxylase is regulated by NQO1. Mol. Cell 17:645–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Patrick BA, Gong X, Jaiswal AK. 2011. Disruption of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene in mice leads to 20S proteasomal degradation of p63 resulting in thinning of epithelium and chemical-induced skin cancer. Oncogene 30:1098–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45. Adler J, Reuven N, Kahana C, Shaul Y. 2010. c-Fos proteasomal degradation is activated by a default mechanism, and its regulation by NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 determines c-Fos serum response kinetics. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30:3767–3778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Patrick BA, Jaiswal AK. 2012. Stress-induced NQO1 controls stability of C/EBPalpha against 20S proteasomal degradation to regulate p63 expression with implications in protection against chemical-induced skin cancer. Oncogene 31:4362–4371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 47. Sollner S, Schober M, Wagner A, Prem A, Lorkova L, Palfey BA, Groll M, Macheroux P. 2009. Quinone reductase acts as a redox switch of the 20S yeast proteasome. EMBO Rep. 10:65–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y. 2007. The Yes-associated protein 1 stabilizes p73 by preventing Itch-mediated ubiquitination of p73. Cell Death Differ. 14:743–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin J, Wu PH, Tarr PT, Lindenberg KS, St-Pierre J, Zhang CY, Mootha VK, Jager S, Vianna CR, Reznick RM, Cui L, Manieri M, Donovan MX, Wu Z, Cooper MP, Fan MC, Rohas LM, Zavacki AM, Cinti S, Shulman GI, Lowell BB, Krainc D, Spiegelman BM. 2004. Defects in adaptive energy metabolism with CNS-linked hyperactivity in PGC-1alpha null mice. Cell 119:121–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zammit PS, Relaix F, Nagata Y, Ruiz AP, Collins CA, Partridge TA, Beauchamp JR. 2006. Pax7 and myogenic progression in skeletal muscle satellite cells. J. Cell Sci. 119:1824–1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Luo J, Deng ZL, Luo X, Tang N, Song WX, Chen J, Sharff KA, Luu HH, Haydon RC, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, He TC. 2007. A protocol for rapid generation of recombinant adenoviruses using the AdEasy system. Nat. Protoc. 2:1236–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fulco M, Cen Y, Zhao P, Hoffman EP, McBurney MW, Sauve AA, Sartorelli V. 2008. Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of Nampt. Dev. Cell 14:661–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Krishna TS, Kong XP, Gary S, Burgers PM, Kuriyan J. 1994. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic DNA polymerase processivity factor PCNA. Cell 79:1233–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tompa P. 2002. Intrinsically unstructured proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27:527–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Devarakonda S, Gupta K, Chalmers MJ, Hunt JF, Griffin PR, Van Duyne GD, Spiegelman BM. 2011. Disorder-to-order transition underlies the structural basis for the assembly of a transcriptionally active PGC-1alpha/ERRgamma complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:18678–18683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu CW, Corboy MJ, DeMartino GN, Thomas PJ. 2003. Endoproteolytic activity of the proteasome. Science 299:408–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tsvetkov P, Asher G, Paz A, Reuven N, Sussman JL, Silman I, Shaul Y. 2008. Operational definition of intrinsically unstructured protein sequences based on susceptibility to the 20S proteasome. Proteins 70:1357–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tsvetkov P, Shaul Y. 2012. Determination of IUP based on susceptibility for degradation by default. Methods Mol. Biol. 895:3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tsvetkov P, Reuven N, Shaul Y. 2009. The nanny model for IDPs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5:778–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. 2008. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: introducing the D2 concept. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 37:215–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Asher G, Dym O, Tsvetkov P, Adler J, Shaul Y. 2006. The crystal structure of NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 in complex with its potent inhibitor dicoumarol. Biochemistry 45:6372–6378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ma Q, Cui K, Xiao F, Lu AY, Yang CS. 1992. Identification of a glycine-rich sequence as an NAD(P)H-binding site and tyrosine 128 as a dicumarol-binding site in rat liver NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 267:22298–22304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fulco M, Schiltz RL, Iezzi S, King MT, Zhao P, Kashiwaya Y, Hoffman E, Veech RL, Sartorelli V. 2003. Sir2 regulates skeletal muscle differentiation as a potential sensor of the redox state. Mol. Cell 12:51–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P. 2010. NAD(P)H:quinone acceptor oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), a multifunctional antioxidant enzyme and exceptionally versatile cytoprotector. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 501:116–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bitterman KJ, Anderson RM, Cohen HY, Latorre-Esteves M, Sinclair DA. 2002. Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast sir2 and human SIRT1. J. Biol. Chem. 277:45099–45107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Daitoku H, Yamagata K, Matsuzaki H, Hatta M, Fukamizu A. 2003. Regulation of PGC-1 promoter activity by protein kinase B and the forkhead transcription factor FKHR. Diabetes 52:642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Louet JF, Hayhurst G, Gonzalez FJ, Girard J, Decaux JF. 2002. The coactivator PGC-1 is involved in the regulation of the liver carnitine palmitoyltransferase I gene expression by cAMP in combination with HNF4 alpha and cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB). J. Biol. Chem. 277:37991–38000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cooper MP, Qu L, Rohas LM, Lin J, Yang W, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Spiegelman BM. 2006. Defects in energy homeostasis in Leigh syndrome French Canadian variant through PGC-1alpha/LRP130 complex. Genes Dev. 20:2996–3009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Williamson DH, Lund P, Krebs HA. 1967. The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of rat liver. Biochem. J. 103:514–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Puigserver P, Rhee J, Donovan J, Walkey CJ, Yoon JC, Oriente F, Kitamura Y, Altomonte J, Dong H, Accili D, Spiegelman BM. 2003. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature 423:550–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Li X, Monks B, Ge Q, Birnbaum MJ. 2007. Akt/PKB regulates hepatic metabolism by directly inhibiting PGC-1alpha transcription coactivator. Nature 447:1012–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ross D, Siegel D. 2004. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1, DT-diaphorase), functions and pharmacogenetics. Methods Enzymol. 382:115–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gsponer J, Futschik ME, Teichmann SA, Babu MM. 2008. Tight regulation of unstructured proteins: from transcript synthesis to protein degradation. Science 322:1365–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rosenfeld N, Alon U. 2003. Response delays and the structure of transcription networks. J. Mol. Biol. 329:645–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Belle A, Tanay A, Bitincka L, Shamir R, O'Shea EK. 2006. Quantification of protein half-lives in the budding yeast proteome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:13004–13009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tsvetkov P, Reuven N, Prives C, Shaul Y. 2009. The susceptibility of the p53 unstructured N-terminus to 20S proteasomal degradation programs stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 284:26234–26242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kim SY, Jeoung NH, Oh CJ, Choi YK, Lee HJ, Kim HJ, Kim JY, Hwang JH, Tadi S, Yim YH, Lee KU, Park KG, Huh S, Min KN, Jeong KH, Park MG, Kwak TH, Kweon GR, Inukai K, Shong M, Lee IK. 2009. Activation of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 prevents arterial restenosis by suppressing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ. Res. 104:842–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.