Abstract

A serum hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titer of 40 or greater is thought to be associated with reduced influenza virus pathogenesis in humans and is often used as a correlate of protection in influenza vaccine studies. We have previously demonstrated that intramuscular vaccination of guinea pigs with inactivated influenza virus generates HAI titers greater than 300 but does not protect vaccinated animals from becoming infected with influenza virus by transmission from an infected cage mate. Only guinea pigs intranasally inoculated with a live influenza virus or a live attenuated virus vaccine, prior to challenge, were protected from transmission (A. C. Lowen et al., J. Virol. 83:2803–2818, 2009.). Because the serum HAI titer is mostly determined by IgG content, these results led us to speculate that prevention of viral transmission may require IgA antibodies or cellular immune responses. To evaluate this hypothesis, guinea pigs and ferrets were administered a potent, neutralizing mouse IgG monoclonal antibody, 30D1 (Ms 30D1 IgG), against the A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus hemagglutinin and exposed to respiratory droplets from animals infected with this virus. Even though HAI titers were greater than 160 1 day postadministration, Ms 30D1 IgG did not prevent airborne transmission to passively immunized recipient animals. In contrast, intramuscular administration of recombinant 30D1 IgA (Ms 30D1 IgA) prevented transmission to 88% of recipient guinea pigs, and Ms 30D1 IgA was detected in animal nasal washes. Ms 30D1 IgG administered intranasally also prevented transmission, suggesting the importance of mucosal immunity in preventing influenza virus transmission. Collectively, our data indicate that IgG antibodies may prevent pathogenesis associated with influenza virus infection but do not protect from virus infection by airborne transmission, while IgA antibodies are more important for preventing transmission of influenza viruses.

INTRODUCTION

Secretory IgA is thought to be the main mediator of upper respiratory tract adaptive mucosal immunity against respiratory viruses (1, 2), but this hypothesis has been primarily evaluated using experimental virus infections in a mouse model. Secretory IgA antibodies contain a joining (J) chain that binds the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR), upon which IgA can be taken up from the basolateral membrane, transcytosed, and released from the apical surface of epithelial cells in the upper respiratory tract (3). Neutralizing IgAs present in the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract are thought to prevent transmission of respiratory viruses along with innate immunity and natural mucosa barriers. Monoclonally derived IgAs only protect mice from influenza virus when administered prior to infection, unlike IgG antibodies, which protect even when administered after infection (4–7). Thus, secretion of antigen-specific IgA antibodies onto the mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory tract is thought to neutralize virus upon inoculation, effectively reducing the challenge titer and providing protection that is dependent on the timing of IgA antibody administration (1, 4).

Intranasal instillation of specific monoclonal IgAs (8, 9) and passive intravenous injection of secretory IgA (1, 10) protect nonimmune mice against intranasal infection; however, the mouse model is not optimal for assessing the role of specific immunoglobulins in preventing the transmission of influenza viruses. Mice transmit influenza viruses inefficiently, only under special conditions, and viruses typically must be mouse adapted to achieve productive infection (11–13). It is unclear if inoculation of a mouse with a bolus of influenza virus in a liquid suspension is sufficiently similar to respiratory droplet exposure to allow the drawing of conclusions about the ability of IgA to protect against transmission. It has not been extensively studied whether systemically administered IgG, IgA, or the two in combination can passively protect nonimmune animals against transmission of respiratory viruses in a genuine influenza transmission model.

Ferrets (14, 15) and guinea pigs (11) have been established as models of influenza virus transmission in which nonadapted, human isolates have been shown to transmit from an inoculated animal to an exposed animal in close proximity. Human isolates can replicate in the upper respiratory tract of ferrets and guinea pigs with peak nasal wash titers reaching up to 3 logs higher than the initial inoculum. This is distinctly different from the mouse model, in which titers from the upper respiratory tract are much lower than lung titers. We have previously shown that guinea pigs infected with influenza viruses and those vaccinated intranasally with a live attenuated influenza vaccine are protected from reinfection by transmission; however, guinea pigs vaccinated intramuscularly with an inactivated vaccine are not protected (16). From these data, we hypothesized that systemic administration of a neutralizing IgG antibody to guinea pigs would reduce viral lung replication of influenza virus but not prevent its transmission, while mucosal immunity and, presumably, IgA, would play a greater role in preventing influenza virus transmission in this animal model.

To evaluate the role of mucosal immunity in the prevention of influenza virus transmission in guinea pigs, we utilized antibody constructs derived from 30D1, a potent neutralizing mouse IgG2b (Ms 30D1 IgG) antibody raised against the hemagglutinin (HA) globular head of a pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus, A/California/04/2009 (Cal09). This antibody was cloned by hybridoma technology and subsequently sequenced, allowing the generation of recombinant 30D1 IgA (Ms 30D1 IgA) antibody. We sought to test our hypothesis by passively immunizing guinea pigs with Ms 30D1 IgA and subsequently exposing them to infected guinea pigs shedding Cal09 in a respiratory droplet transmission model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human embryonic kidney (293T) and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin. Sf9 (ATCC CRL-1711) insect cells were maintained in TNM-FH medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.1% Pluronic F68 (Sigma), and penicillin-streptomycin (17). BTI-TN-5B1-4 (High Five) cells were grown in SFX serum free medium (Fisher Scientific) supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin (17). Recombinant A/California/04/2009 (Cal09) influenza virus was rescued as previously described (18, 19) and propagated on MDCK cells at 35°C in the presence of 1 μg/ml tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (Sigma). A/Netherlands/602/2009 (Neth09) virus was propagated on MDCK cells at 35°C in the presence of 1 μg/ml TPCK-treated trypsin (Sigma). Cal09 and Neth09 virus hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) segments were sequenced. Mouse-adapted Neth09 (Neth09-ms) was serially passaged in mice, and virus from the lungs in the 5th passage was amplified in embryonated eggs. Cal09 HA-expressing baculovirus was rescued as previously described (17) and propagated on Sf9 insect cells.

Antibody sequencing and expression vectors.

The variable sequences of the heavy and light chains of murine 30D1 IgG2b (Ms 30D1 IgG) were cloned using universal primers (20) (GenBank accession no. KC845536 and KC845537). All synthetic sequences were codon optimized for expression in mammalian cells and synthesized by GENEWIZ (South Plainfield, NJ). A murine J chain was synthesized based on a published sequence (accession no. AAA38674). The Ms 30D1 IgA was synthesized with a murine κ leader sequence (21), the 30D1 variable heavy chain, and the murine α constant chain based on accession no. AAB59662 (Fig. 1A). The 30D1 κ gene was synthesized with a murine κ leader sequence, the 30D1 κ-chain variable region, and a generic murine κ constant chain based on accession no. AAB53776. These constructs were each cloned into pcDNA3.1(+) (Invitrogen). In order to obtain an antibody with a native guinea pig Fc portion, the 30D1 heavy-chain variable region was also synthesized with a guinea pig IgG2 constant chain (GenBank accession no. P01862) and cloned into pcDNA3.1(+). Variable regions from an isotype control monoclonal antibody IG6 (IgG2b) (GenBank accession no. KC845538 and KC845539) were codon optimized and cloned into the guinea pig IgG2 construct as well as the mouse κ-chain construct to generate a control antibody with a guinea pig IgG2 constant chain. IG6 is a mouse monoclonal antibody directed against the PB2 segment of A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) virus. Guinea pig J-chain and IgA constant region sequences (accession no. KC845534 and KC845535) were obtained by using specific end-to-end primers (forward, ATGAAGAACCATATGCTTTTCTGG; reverse, CTAGTCGGGGTAGCAGGAATC) based on a predicted sequence (J chain, accession no. XM_003467555) or degenerate primers based on available mouse, rat, and human sequences (forward, YCYSCRAVMVRBCCCAMSRTCTWCCCRCTGA; reverse, GTAGCARRTGCCRTCYMCCTCYGMCATGA). mRNA sequences were amplified from a guinea pig small bowel cDNA library generated using SuperScript III (Invitrogen) and a poly(T) primer. The murine κ leader sequence and the 30D1 heavy-chain variable region sequence were added to the guinea pig IgA constant region sequence for a complete IgA heavy-chain gene. Both the guinea pig J-chain and the 30D1-based guinea pig IgA sequences were codon optimized for mammalian expression and synthesized by GENEWIZ.

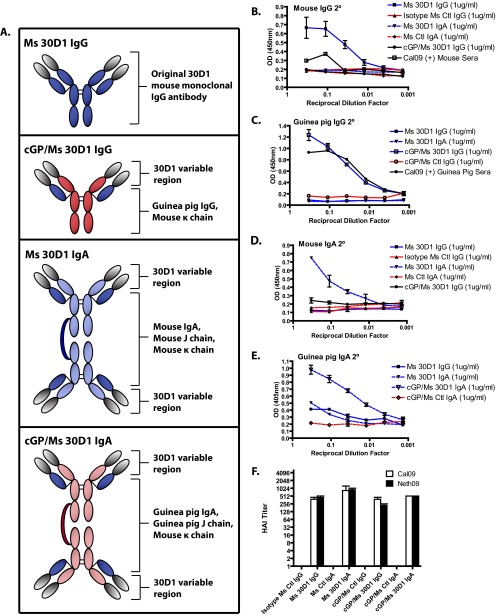

Fig 1.

Purified Ms 30D1 IgG and recombinant 30D1 antibodies react against Cal09 HA by ELISA and show HAI activity. (A) Diagram of 30D1 IgG and the recombinant antibody constructs used in the study. Ms 30D1 IgG (B), cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG (C), Ms 30D1 IgA (D), and cGP/Ms 30D1 IgA (E) are specifically reactive against purified Cal09 HA by ELISA compared to irrelevant control antibodies. (F) Ms 30D1 IgG and recombinant 30D1 antibodies at 50 μg/ml all show similar HAI activities against two H1N1 pandemic viruses: Cal09 virus and A/Netherlands/602/2009 (Neth09).

Protein expression and purification.

Ms 30D1 IgG and a control IgG2b monoclonal antibody, IG6 (Ms Ctl IgG), were obtained by purifying hybridoma supernatant over a protein A gravity flow column (GE Healthcare). All recombinant mouse IgA and guinea pig IgG antibodies (Fig. 1A) were produced by transient transfection of the appropriate plasmids in 293T cells (Invitrogen) using linear polyethyleneimine (PEI) (Fisher Scientific) and by purifying the supernatant over a CaptureSelect LC-kappa (mur) gravity column (BAC B.V.). To express murine 30D1 IgA (Ms 30D1 IgA), the respective α- and κ-chain plasmids were cotransfected together with the murine J-chain plasmid. A control IgA antibody (Ms Ctl IgA) was purchased from Southern Biotech (catalog no. 0106-01). To produce murine 30D1 with a guinea pig IgG2 constant chain (cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG), the chimeric 30D1 guinea pig IgG2 construct was cotransfected with the murine 30D1 κ chain and purified over a CaptureSelect LC-kappa (mur) gravity flow column. A negative-control guinea pig IgG2 (cGP/Ms Ctl IgG) was produced in a similar manner using IG6 variable regions with the appropriate control heavy- and light-chain constructs. After elution of antibodies in a pH 3.0 buffer, the eluate was buffer exchanged across phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on an Amicon column (Millipore). To produce a guinea pig IgA with 30D1 or IG6 variable regions (cGP/Ms 30D1 IgA or cGP/Ms Ctl IgA, respectively), plasmids expressing the appropriate mouse κ chain, chimeric guinea pig heavy chain, and guinea pig J chain were cotransfected into 293T cells and grown for 3 days in serum-free F17 medium (Invitrogen) (Fig. 1A). Guinea pig IgA antibodies were purified from supernatants using Affi-Gel columns (Bio-Rad) coated with specific antigen (Cal09 HA for 30D1 and influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 [PR8] PB2 fragment amino acids 535 to 759 for IG6) and eluted with a pH 3.0 buffer. The eluate was buffer exchanged across PBS on an Amicon column. The purity of the protein preparations was documented by a nonreducing, denaturing SDS-PAGE. The functional activity of the antibodies was assessed by hemagglutinin inhibition (HAI) assay (22).

Cal09 HA was produced by infecting BTI-TN-5B1-4 (High Five) insect cells with a Cal09 HA-expressing baculovirus as previously described (17), and the supernatant was purified on a nickel column (Qiagen) using a hexahistidine tag. Protein was dialyzed across PBS and concentrated on an Amicon column (Millipore).

The IG6 binding region of PR8 PB2 (amino acids 535 to 759) was expressed with a hexahistidine tag using a pET30+ vector in Escherichia coli BL21(DES) cells (Invitrogen). At an optical density (OD) of 0.6 to 0.8, cells were induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 h at 30°C, pelleted, and lysed by sonication in a 6 M urea buffer (6 M urea, 100 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole). Lysates were run over a nickel column (Qiagen), and protein was eluted with a 6 M urea elution buffer (6 M urea, 100 mM Na2HPO4 [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole). Protein was concentrated on an Amicon column (Millipore).

ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates were coated with 10 μg purified Cal09 HA protein in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) (17). Plates were blocked with PBS supplemented with 5% nonfat milk and 0.01% Tween 20. Purified antibodies were diluted to 1 μg/ml and serially diluted 3-fold. Secondary antibodies (anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase [HRP] [Millipore], anti-mouse IgA-HRP [Southern Biotech], anti-guinea pig IgG-HRP [Abcam], and anti-guinea pig IgA [Bethyl Laboratories]) were used at dilutions of 1:5,000, with the exception of anti-guinea pig IgA, which was diluted to 1:100. Anti-guinea pig IgA was raised in rabbits and required a tertiary anti-rabbit antibody made in goat (anti-rabbit Ig-alkaline phosphatase [AP]; Southern Biotech) used at 1:5,000. o-Phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) (Sigma) and p-nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP) (Invitrogen) were used as the substrates and read at optical densities of 450 nm and 405 nm, respectively.

Virus titrations.

Titers of influenza virus stocks, lung homogenates, and nasal washes were determined by incubating 10-fold serial dilutions on MDCK monolayers for 1 h and then replacing the medium with a 0.6% agar overlay supplemented with TPCK trypsin (1 μg/ml), penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.3% bovine albumin (BA) (23). Plaques were quantified after incubating them for 3 days at 37°C.

HAI assay.

Cal09, Neth09, and Neth09-ms viruses were diluted to 3 wells of hemagglutination, and 25 μl of diluted virus was combined with serially diluted antibody in 25 μl PBS or 25 μl of receptor-destroying enzyme (RDE)-treated sera for 1 h (22). PBS supplemented with 0.5% turkey red blood cells (50 μl) was added to each well, and the wells were incubated for an hour before analysis (22).

Mouse experiments.

Six- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice (Jackson laboratories) were intraperitoneally administered 1 mg/kg of body weight of either Ms 30D1 IgG or Ms 30D1 IgA 3 h before infection or 24 h after infection. Mice were challenged with 10 50% lethal doses (LD50s) of Neth09-ms virus under anesthesia and monitored for weight loss for 14 days. Mice losing 25% of their body weight were euthanized as per institutional policy. Separate groups of mice treated with 1 mg/kg of Ms 30D1 IgG or Ms 30D1 IgA prior to challenge were sacrificed 7 days postinfection. Lungs were perfused with PBS and homogenized (Fastprep-24; MP Biomedical) in 1 ml PBS. The samples were clarified by microcentrifugation, and supernatants were quantified by plaque assay.

Guinea pig experiments.

Aerosol transmission experiments using guinea pigs were performed as previously described (24–26). In brief, 4 guinea pigs were inoculated with 1,000 PFU of Cal09 virus and 24 h later moved into an environmental chamber (Caron model 6030) with 4 recipient animals. Each guinea pig was in its own cage and not in physical contact the other guinea pigs, limiting transmission to an aerosol/droplet mechanism. Transmission kinetics were monitored by anesthetizing guinea pigs every other day to perform nasal washes. Calculations of the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) to identify whether a significant delay in transmission occurred were performed as previously described (27).

In this study, we modified the experimental design in two ways. First, guinea pigs were only kept in the environmental chambers for the first 5 days, and then the recipient guinea pigs were removed and caged individually for the duration of the experiment, including seroconversion. Second, recipient guinea pigs were treated either intramuscularly or by intranasal instillation with antibody 24 h prior to movement into the environmental chamber. Treated guinea pigs were not monitored for pathogenesis because infected guinea pigs do not display overt signs of disease, such as weight loss (11). For the intramuscular treatment groups, guinea pigs were injected with 10 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgG, 7 mg/kg cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG, 1 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgA, 5 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgA, or 1 mg/kg cGP/Ms 30D1 IgA at a single time point; control guinea pigs were treated with irrelevant control antibodies at the same doses. In each experiment, the environmental chamber contained 4 inoculated donor guinea pigs shedding virus, 2 recipient guinea pigs treated with a 30D1-derived antibody, and 2 recipient guinea pigs treated with a control antibody. For the intranasal treatment groups, anesthetized guinea pigs were instilled with 900 μg of antibody in 300 μl of buffer every day for the first 5 days. In each experiment, the environmental chamber contained 4 inoculated donor guinea pigs shedding virus, 2 recipient guinea pigs treated with Ms 30D1 IgG, and 2 recipient guinea pigs treated with Ms Ctl IgG. In a separate intranasal treatment experiment, recipient guinea pigs were instilled with a single dose of either 900 μg or 900 ng of Ms 30D1 IgG 24 h prior to movement into the chamber. Control antibody-treated recipient animals were not included in these experiments as 900 μg of control antibody Ms Ctl IgG administered daily had no effect on transmission.

To determine the effect of antibody treatment on guinea pig nasal wash titers and lung titers, 12 guinea pigs in each group were treated with either 10 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgG or a control antibody and 24 h later inoculated with 1,000 PFU of Cal09 virus. Four guinea pigs from each of the Ms 30D1 IgG- and control-treated groups were nasal washed and sacrificed to determine the lung titers on days 1, 3, and 5; the remaining guinea pigs were also nasal washed on the same days. The lungs of sacrificed guinea pigs were perfused with PBS supplemented with 5 mM EDTA, and 0.5 g of tissue was placed in 1 ml of PBS, homogenized, and virus was quantified by plaque assay. Saphenous vein bleeds under anesthesia were performed in most experiments to either monitor the level of antibody in the serum by HAI assay or to collect convalescent-phase sera to determine seroconversion.

Ferret experiments.

Aerosol transmission experiments in ferrets were performed as previously described (24). In brief, ferrets were bled under anesthesia from the superior vena cava or the saphenous vein to determine if they were naive to Cal09 virus by HAI activity. For transmission experiments, one ferret was inoculated with 104 PFU under anesthesia, and 24 h later, two recipient ferrets were moved into the same cage on the opposite side of a perforated Plexiglas barrier that allows for aerosol/droplet transmission but no contact. All ferrets were weighed daily and monitored for signs of pathogenesis. Unique to our experimental design, recipient ferrets were administered either 3 mg/kg of Ms 30D1 IgG or Ms Ctl IgG intravenously 24 h before they were paired with an infected ferret. Differences in disease severity between Ms 30D1 IgG- and Ms Ctl IgG-treated ferrets were monitored by weight loss. In each experimental replicate, one Ms 30D1 IgG-treated ferret and one Ms Ctl IgG-treated ferret were exposed to a single inoculated ferret caged on the opposite side of the Plexiglas barrier. In separate experiments, 12 ferrets were treated intravenously with either 3 mg/kg of Ms 30D1 IgG or Ms Ctl IgG and 24 h later directly inoculated with 106 PFU of Cal09 virus. Six of these ferrets were monitored for weight loss and nasal washed every other day to monitor viral shedding by nasal wash titers. Six separate ferrets were sacrificed on day 3 for tissue analysis. The virus titers in nasal washes, bronchoalveolar washes, and lung homogenates were determined by plaque assay. White blood cells in lung lavages were stained by diluting samples 1:10 in a 2% glacial acetic acid–1% crystal violet solution and quantified using a hemocytometer. Lung lavage samples were analyzed for the presence of Ms 30D1 IgG by Cal09 HA ELISA.

Antibody kinetics.

Kinetic binding analysis for Ms 30D1 IgG and monomeric Ms 30D1 IgA was performed using biolayer interferometry on an Octet Red96 platform (Pall ForteBio Corp., Menlo Park, CA). Briefly, recombinant Cal09 HA was biotinylated in a 1:1 molar ratio (EZ-link Micro NHS-PEG4 biotinylation kit; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and immobilized to saturation onto streptavidin dip-and-read biosensors. Conjugated biosensors were then dipped into various dilutions of monomeric Ms 30D1 IgA or Ms 30D1 IgG, and association/dissociation curves were established over time. Kinetic curves, on/off rates, and Kd (dissociation constant), R2, and X2 values were generated using Octet software following a 1:1 global curve-fitting model. Recombinant monomeric Ms 30D1 IgA was generated by transfecting 293T cells with only the appropriate heavy and light chains (no mouse J chain) and purifying antibody from the supernatant on a CaptureSelect LC-kappa (mur) gravity column. Ms 30D1 IgG was isolated as previously described.

Ethics statement.

All animal procedures performed in this study are in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines and have been approved by the IACUC of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

RESULTS

Neutralizing mouse monoclonal antibody 30D1 can be expressed as an IgA without losing HAI activity.

Neutralizing IgG2b antibody 30D1 (Ms 30D1 IgG), isolated through mouse hybridoma technology, binds the hemagglutinin (HA) protein of A/California/04/2009 influenza virus (Cal09), a 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus. This antibody possesses potent neutralizing specificity for Cal09; 50 μg/ml of antibody generates an HAI titer of 512. The variable regions were cloned from the parent hybridoma cell line and used to generate a mouse IgA (Ms 30D1 IgA) by substituting a mouse IgA heavy chain for the original IgG heavy chain (Fig. 1A). We also cloned chimeric guinea pig IgG and IgA, in which the murine variable region of 30D1 was fused to the Fc portions of either guinea pig IgG (cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG) or guinea pig IgA (cGP/Ms 30D1 IgA). These proteins all reacted with Cal09 HA protein by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and were specifically bound by the appropriate mouse and guinea pig IgG and IgA secondary antibodies (Fig. 1A to E). For comparison, a control IgG2b antibody IG6 was cloned and used to generate controls for the chimeric guinea pig IgG (cGP/Ms Ctl IgG) and for the chimeric guinea pig IgA (cGP/Ms Ctl IgA). Perhaps most importantly for comparison of their efficacies, purified preparations of recombinant 30D1 IgG and IgA antibodies all generate HAI titers against Cal09 virus within 2-fold of the original Ms 30D1 IgG (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, Ms 30D1 IgG and monomeric Ms 30D1 IgA have similar Kd values for recombinant Cal09 HA protein (5.0 nM and 2.4 nM, respectively), suggesting similar affinities with different heavy chains (28).

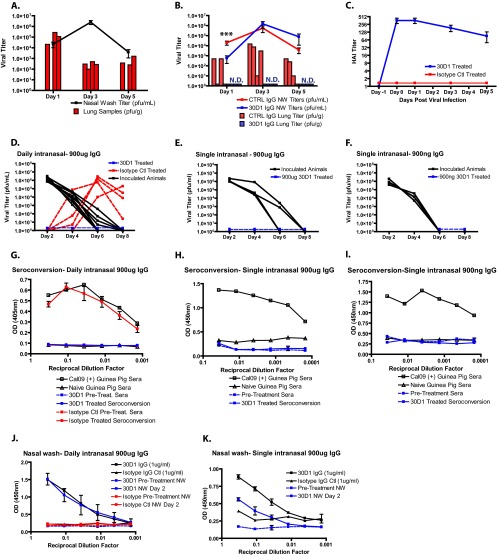

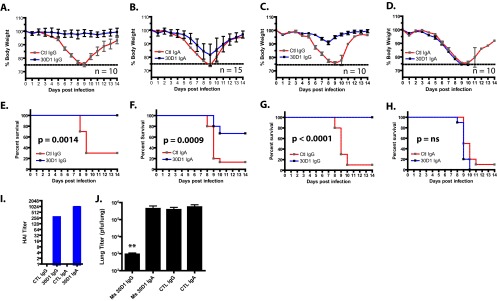

Ms 30D1 IgA only protects mice when administered prior to infection, whereas Ms 30D1 IgG protects when administered before and after infection.

Ms 30D1 IgA (1 mg/kg) and Ms 30D1 IgG (1 mg/kg) were administered to mice intraperitoneally 3 h before infection or 24 h after infection to confirm their ability to neutralize virus in vivo and protect mice from a 10-LD50 challenge with a mouse-adapted A/Netherlands/602/2009 (H1N1) pandemic virus (Neth09-ms). Similar HAI titers were obtained against Neth09-ms virus with 50 μg/ml of antibody, suggesting that the 30D1 epitope remained intact during mouse adaptation (Fig. 2I). Both Ms 30D1 IgA and Ms 30D1 IgG protected mice treated prophylactically; however, there was noticeable weight loss among the Ms 30D1 IgA-treated animals (Fig. 2A, B, E, and F), indicative of increased pathogenesis in the mice treated with Ms 30D1 IgA. In fact, treatment with Ms 30D1 IgA had no significant effect on lung titers 7 days postinfection, even though it conferred a survival benefit (Fig. 2J). Ms 30D1 IgG-treated animals lost no weight over the course of 14 days, and lung titers of animals treated with Ms 30D1 IgG showed a 2.5-log reduction in viral titer (Fig. 2J). When Ms 30D1 IgA and Ms 30D1 IgG were administered to mice therapeutically, only Ms 30D1 IgG protected mice (Fig. 2C, D, G, and H). These results show that Ms 30D1 IgA provides a limited protective benefit and only when given prior to infection. This is consistent with its lack of impact on viral lung titers, which are the main driver of disease. To address whether the antibody treatments impact titers in the upper respiratory tract and in virus transmission, we next evaluated Ms 30D1 IgG in the guinea pig transmission model.

Fig 2.

Both Ms 30D1 IgG and Ms 30D1 IgA show protection when administered prior to infection, but only Ms 30D1 IgG shows protection when administered after infection. Mice were administered Ms 30D1 IgG (A and E) or Ms 30D1 IgA (B and F) 3 h prior to infection and challenged with 10 LD50s of a mouse-adapted A/Netherlands/602/2009 virus (Neth09-ms). The upper panel shows the percentage of weight loss, while the lower panel shows survival curves. Both Ms 30D1 IgG and Ms 30D1 IgA show a survival benefit. Mice were challenged with 10 LD50s Neth09-ms and administered Ms 30D1 IgG (C and G) or Ms 30D1 IgA (D and H) 24 h after infection. The upper panel shows the percentage of weight loss, while the lower panel shows survival curves. Only Ms 30D1 IgG treatment showed a survival benefit. ns, not significant. (I) Both Ms 30D1 IgG and Ms 30D1 IgA show HAI activity against mouse-adapted Neth09 virus (Neth09-ms) at 50 μg/ml. (J) Only prophylactic Ms 30D1 IgG (but not Ms 30D1 IgA) reduces lung viral titers 3 days postinfection. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, and lung titers were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test (**, P < 0.01). Mouse experiments were completed as two independent replicates.

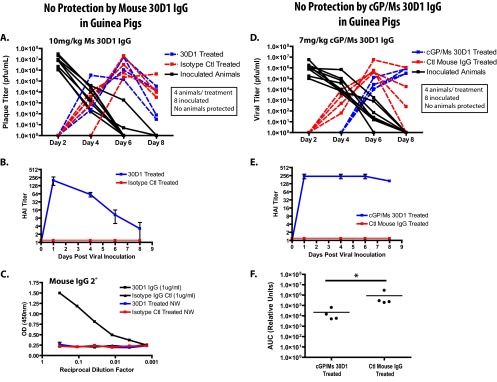

Ms 30D1 IgG and cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG are unable to prevent transmission in the guinea pig model.

Guinea pigs were passively immunized with 10 mg/kg of Ms 30D1 IgG intramuscularly on day 0 and 24 h later exposed to aerosols/droplets from infected guinea pigs caged separately in a climate-controlled environmental chamber. Ms 30D1 IgG elevated the HAI titer of treated guinea pigs to greater than 160 prior to their placement in the environmental chamber, but no protection from transmission was observed (Fig. 3A and B). All 4 animals in each treatment group were shedding Cal09 virus by day 6. Similarly, guinea pigs were treated with 7 mg/kg of cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG intramuscularly, resulting in an HAI titer of 256 prior to exposure to aerosols/droplets from infected guinea pigs (Fig. 3E). The substitution of a guinea pig IgG Fc portion for the mouse Fc noticeably increased the serum half-life of the 30D1 antibody, so substantial quantities of IgG were present throughout the transmission experiment (Fig. 3E compared to B). Still no protection from transmission was observed (Fig. 3D). However, a significant delay in transmission occurred as identified by a decrease in the area under the curve generated by serial nasal wash titers obtained during transmission experiments (Fig. 3F). While the delay in transmission was reproducible, there was no overall decrease in transmission to passively immunized animals.

Fig 3.

Neither Ms 30D1 IgG nor cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG prevents transmission of Cal09 virus in guinea pigs. (A and B) A 10-mg/kg dose of Ms 30D1 IgG administered intramuscularly does not prevent transmission to treated animals and elevates the HAI titer of guinea pigs above 128 by day 1. (C) No Ms 30D1 IgG is detected by Cal09 HA ELISA in the nasal washes (NW) of treated guinea pigs 2 days after administration. (D and E) A 7-mg/kg dose of cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG administered intramuscularly does not prevent transmission to treated guinea pigs and elevates the HAI titer of guinea pigs to 256 by day 1. (F) cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG delays transmission as determined by a significant difference in the nasal wash titer area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) through day 6. The AUC was analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test (*, P < 0.05). All guinea pig experiments were completed as two independent replicates.

Ms 30D1 IgG neutralizes virus replication in the lungs of guinea pigs and prevents transmission when applied intranasally.

Ms 30D1 IgG administered intramuscularly to recipient animals did not prevent transmission, even when present at high HAI titers. To show that the antibody was active in guinea pigs, we confirmed its activity to reduce viral lung titers and prevent transmission when applied intranasally. Influenza viruses replicate primarily in the upper respiratory tract of guinea pigs, with lower replication in the lungs (Fig. 4A). Guinea pigs were treated intramuscularly with 10 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgG, and 24 h later inoculated with Cal09 virus. Ms 30D1 IgG neutralized lung replication in all treated animals (n = 12) to undetectable levels and only reduced nasal wash titers 1 day postinoculation (Fig. 4B). These results are consistent with a limited role for IgG in the upper respiratory tract, where mucosal immunity is considered to be more important. However, as demonstrated in the mouse model, IgG can confer protection from pathogenicity and reduce titers in the lung (Fig. 2A and J and Fig. 4B). To see if an immunoglobulin that was directly administered to the upper respiratory tract could prevent transmission, we treated recipient guinea pigs by instilling 900 μg of Ms 30D1 IgG intranasally before exposing them to aerosols/droplets from infected guinea pigs. On the following 5 days, 900 μg of Ms 30D1 IgG was instilled daily, until the recipient guinea pigs were removed from the environmental chamber (Fig. 4D). All 4 control antibody-treated recipient animals contracted Cal09 virus, as shown by the rising nasal wash titers, but all 4 of the recipient animals treated with Ms 30D1 IgG never shed Cal09 virus. To confirm that the 4 protected animals were never infected, we allowed the animals to seroconvert for 3 weeks and tested for reactivity against recombinant Cal09 HA by ELISA. Only sera from recipient animals treated with the control antibody, which all shed Cal09 virus during the transmission experiment, showed reactivity, indicating that Ms 30D1 IgG-treated animals remained immunologically naive to Cal09 virus despite exposure (Fig. 4G). Perhaps not surprisingly, Ms 30D1 IgG was easily detected by ELISA against Cal09 HA in the day 2 nasal washes of treated animals (Fig. 4J). Guinea pigs were also treated with a single intranasal instillation of 900 μg or 900 ng of Ms 30D1 IgG prior to exposure to aerosols/droplets from infected guinea pigs. Both doses, even as a single instillation, protected guinea pigs treated with Ms 30D1 IgG. Ms 30D1 IgG-treated animals never shed Cal09 virus and did not seroconvert (Fig. 4E, F, H, and I).

Fig 4.

Ms 30D1 IgG neutralizes lung replication in Cal09-inoculated guinea pigs and prevents transmission when instilled intranasally. (A) Cal09 infection (1,000 PFU per animal) generates greater peak nasal wash (NW) titers than lung titers in guinea pigs. (B) A 10-mg/kg intramuscular administration of Ms 30D1 IgG prior to a Cal09 1,000-PFU inoculation limits lung replication and reduces nasal wash titers only 24 h after inoculation. N.D., not determined. (C) HAI titers for antibody-treated guinea pigs inoculated with Cal09 virus in panel B. (D) Daily intranasal administration of 900 μg Ms 30D1 IgG for the first 5 days prevents transmission, while intranasal administration of 900 μg Ms Ctl IgG to 4 guinea pigs did not prevent transmission. (E and F) A single administration of 900 μg Ms 30D1 IgG (E) and a single administration of 900 ng Ms 30D1 IgG (F) both prevent transmission to treated animals. (G to I) Animals that were protected by intranasal administration of antibody did not seroconvert against Cal09 HA by ELISA; all animals treated with 900 μg of control antibody seroconverted. (J and K) Day 2 nasal washes from animals treated with 900 μg Ms 30D1 IgG daily or with a single intranasal dose of 900 μg of Ms 30D1 IgG are reactive to Cal09 HA by ELISA. Nasal wash titers were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney test (***, P < 0.001). Panels A, B, and D are representative of 2 replicates. Panels E and F are single experiments with 4 treated recipient guinea pigs per experiment.

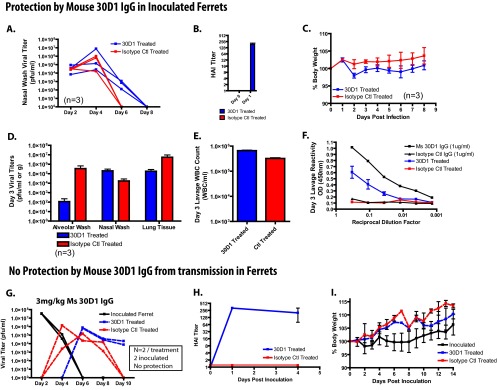

Ferrets passively immunized with Ms 30D1 IgG intravenously are not protected from transmission; however, Ms 30D1 IgG treatment reduces alveolar wash titers and lung titers in ferrets directly inoculated with virus.

The ferret influenza model is used to study both influenza virus pathogenesis as well as transmission; thus, it provided the opportunity to confirm results observed in both the mouse model of pathogenesis and the guinea pig transmission model in which animals were treated with Ms 30D1 IgG and subsequently challenged. As expected, ferrets treated with Ms 30D1 IgG showed a reduction in lung titers, but antibody treatment failed to prevent transmission (Fig. 5). To study the ability of Ms 30D1 IgG to prevent pathogenesis in ferrets, 12 ferrets were treated with 3 mg/kg mouse IgG intravenously (6 with Ms 30D1 IgG and 6 with an unrelated control IgG) and 24 h later inoculated with 106 PFU Cal09 virus to see if treatment could reduce weight loss, intranasal viral shedding, and lung titers. Three of the 6 Ms 30D1 IgG-treated ferrets were monitored for 8 days, showing minimal differences in weight loss, peak nasal wash titers, or the length of virus shedding in comparison to control IgG-treated animals (Fig. 5A to C). There was a trend toward increased weight loss in the Ms 30D1 IgG-treated ferrets compared with control animals; however, no animal lost more than 3% of original body weight. The remaining 3 ferrets that were treated with Ms 30D1 IgG were sacrificed 3 days postinoculation to determine the lung titers. Animals treated with Ms 30D1 IgG showed some reduction in lung tissue titer, but most impressively, animals treated with Ms 30D1 IgG showed a 3.5-log drop in alveolar lavage titer (Fig. 5D). This drop in titer was associated with the presence of Ms 30D1 IgG in the alveolar space (Fig. 5F). No difference was observed in the alveolar wash white blood cell count between treatment groups (Fig. 5E). Although these studies did not show a reduction in pathogenesis conferred by Ms 30D1 IgG as measured by weight loss, they do confirm a reduction in lung titers previously observed in guinea pigs (Fig. 4B) and mice (Fig. 2J) treated with Ms 30D1 IgG.

Fig 5.

Ms 30D1 IgG does not prevent transmission in ferrets but reduces alveolar wash titers. (A to F) Six ferrets were treated with 3 mg/kg of Ms 30D1 IgG intravenously, generating a serum HAI titer of 256 (B) and inoculated with 106 PFU of Cal09 virus. Three animals were monitored for nasal wash titers (A) and weight loss (C), while 3 animals were sacrificed on day 3 for analysis of viral titers (D), lung lavage white blood cell count (E), and Ms 30D1 IgG lung lavage reactivity against Cal09 HA by ELISA (F). (G to I) 3 mg/kg of Ms 30D1 IgG administered intravenously did not prevent transmission to ferrets (G) and generated a serum HAI titer of 256 (H). (I) No difference in weight loss was observed between Ms 30D1 IgG-treated animals and control IgG-treated animals. The experiments in panels A, C, D, E, and F were performed with 3 treated ferrets and 3 control antibody ferrets. The experiment in panel B was performed with 6 treated ferrets and 6 control ferrets. Panels G, H, and I are representative of 2 replicates with 1 inoculated ferret, 1 Ms 30D1 IgG-treated recipient ferret, and 1 control IgG-treated recipient ferret.

To study the ability of Ms 30D1 IgG to prevent transmission, ferrets were also treated intravenously with 3 mg/kg of Ms 30D1 IgG or a control IgG and 24 h later exposed to aerosols/droplets from ferrets shedding influenza virus (Fig. 5G). A 3-mg/kg dose of Ms 30D1 IgG administered intravenously generated HAI titers greater than 256 1 day postadministration, and these high titers remained greater than 40 for at least 4 days after initial administration (Fig. 5H). No protection from transmission was observed in Ms 30D1 IgG-treated recipient ferrets, confirming earlier studies in the guinea pig transmission model in which a similar HAI titer was generated prior to challenge (Fig. 5A versus Fig. 3B and E). As with the prior study in which ferrets were inoculated with influenza virus, neither donor nor recipient ferrets lost significant weight over the course of the experiment (Fig. 5I).

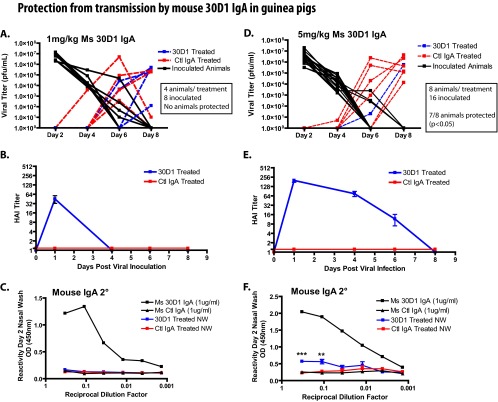

Ms 30D1 IgA administered intramuscularly prevents transmission of Cal09 virus in a dose-dependent manner and is associated with IgA detection in the treated-animal nasal washes.

Ms 30D1 IgA was hypothesized to efficiently transport to mucosal surfaces and potentially provide better protection against airborne influenza virus. Guinea pigs were administered either 1 or 5 mg/kg of Ms 30D1 IgA intramuscularly 24 h prior to exposure to aerosols/droplets from inoculated guinea pigs in an environmental chamber. The nasal washes of animals treated with Ms 30D1 IgA or an irrelevant control IgA were monitored for viral replication, indicating a transmission event. A 1-mg/kg dose of Ms 30D1 IgA appeared to delay transmission, but no Ms 30D1 IgA-treated animals were protected and no Ms 30D1 IgA was detected in the nasal washes (Fig. 6A to C). 30D1 expressed as a guinea pig IgA (cGP/Ms 30D1 IgA) and administered at 1 mg/kg also did not protect guinea pigs from transmission (data not shown), suggesting that matching the species J chain and IgA heavy chain did not greatly improve protection. When the Ms 30D1 IgA intramuscular dose was increased to 5 mg/kg, 7 out of 8 animals were protected from transmission (Fig. 6D). This represents a significant difference (P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test) from control IgA-treated animals (6 out of 8 animals shed virus). Nasal washes from guinea pigs treated with 5 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgA collected 48 h after the IgA was administered intramuscularly (but not 1-mg/kg nasal washes) contained detectable levels of Ms 30D1 IgA, suggesting that transport of immunoglobulin onto mucosal surfaces may be important for preventing transmission (Fig. 6C and F). Similar experiments were not performed with ferrets due to limitations in producing tissue culture-expressed monoclonal antibodies.

Fig 6.

Intramuscular injection of Ms 30D1 IgA prevents transmission of a Cal09 virus in a dose-dependent manner. (A) Guinea pigs treated intramuscularly with 1 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgA were not protected from transmission. (B) Animals treated with 1 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgA reached a peak serum HAI titer of 40 on day 1. (C) No Ms 30D1 IgA was detected in day 2 nasal washes by Cal09 HA ELISA. (D) Guinea pigs treated intramuscularly with 5 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgA were protected from transmission. (E) Animals treated with 5 mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgA reached a peak serum HAI titer of 160 on day 1. (F) Ms 30D1 IgA was detected in day 2 nasal washes by Cal09 HA ELISA. Protection by the 5-mg/kg Ms 30D1 IgA treatment was analyzed by Fisher's exact test. Panels A, B, and C are representative of 2 replicates with 4 inoculated guinea pigs, 2 Ms 30D1 IgA-treated recipient guinea pigs, and 2 control IgA-treated recipient guinea pigs. Panels D, E, and F are representative of 4 replicates with 4 inoculated guinea pigs, 2 Ms 30D1 IgA-treated recipient guinea pigs, and 2 control IgA-treated recipient guinea pigs.

DISCUSSION

Monoclonal antibody Ms 30D1 IgG and a recombinant IgA of the same antibody (Ms 30D1 IgA) are neutralizing antibodies that target the HA of Cal09 influenza virus, providing us with the opportunity to study the ability of IgG and IgA to prevent airborne transmission while controlling for an antibody's affinity and epitope. Prior studies have extensively evaluated the ability of IgG to reduce lung titers (1, 4–6), but there has been poor characterization of the ability of an immunoglobulin to prevent transmission of influenza virus in genuine transmission models, such as the ferret and the guinea pig models. We show that Ms 30D1 IgG reduces pathogenesis without protection from transmission in the mouse, guinea pig, and ferret models; however, the same antibody expressed as an IgA (Ms 30D1 IgA) effectively prevents airborne transmission in the guinea pig model.

The mouse model of influenza virus infection primarily investigates pathogenesis, as mice do not (consistently) transmit influenza virus (11–13). The ability of IgG and IgA antibodies to protect mice from influenza virus is very well characterized (1, 4), providing us with a way to validate that our Ms 30D1 IgG and Ms 30D1 IgA preparations perform as expected in vivo. Consistent with prior reports, we showed that these antibodies protected mice when administered prior to infection, but only Ms 30D1 IgG was able to protect mice when administered after infection. Interestingly, the protection observed by Ms 30D1 IgA appears to be limited to survival, as the majority of treated mice lost more than 15% of their body weight and showed no reduction in lung titers. Thus, Ms 30D1 IgA activity may be limited to the upper respiratory tract, where it partially neutralizes the initial viral inoculum, reducing the viral dose. As Ms 30D1 IgA does not inhibit lung replication, the mice likely recover by generating their own adaptive immune response to the virus after 6 to 7 days, including the production of IgG. Mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), which lack the ability to generate robust adaptive immune responses, are also not protected by the passive transfer of IgA given after infection (even if given repeated doses); however, administration of IgA prophylactically appears to prevent infection of SCID mice, suggesting again that IgA administration is able to neutralize the initial viral inoculum (4, 29). Conversely, IgG administered to SCID mice protects 100% of mice from lethality even when administered after infection, but does not provide sterilizing immunity. Virus in SCID mice treated with IgG is easily detected in the upper respiratory tract up to 14 days postinfection, suggesting the ability of IgG to protect mice is limited to lung replication (29). Thus, the localized activity of IgG and IgA in the mouse model suggests that virus replication in the lung is inhibited by IgG and virus replication in the upper respiratory tract is inhibited by IgA.

Guinea pigs and ferrets can transmit influenza virus through airborne particles, allowing us to evaluate whether IgG is sufficient to prevent transmission. Ms 30D1 IgG was administered to both recipient guinea pigs and ferrets, generating HAI titers in both species of greater than 160; however, no protection from transmission was observed. To confirm that Ms 30D1 IgG was active in both guinea pigs and ferrets, lung titers were determined, which showed a reduction of viral lung replication. Additionally, ELISAs on ferret lung lavage samples showed Ms 30D1 IgG in the alveoli, suggesting that the Ms 30D1 IgG was able to move by transudation into the air space. We tried to improve the stability of Ms 30D1 IgG in guinea pigs by expressing the 30D1 variable regions as a recombinant guinea pig IgG (cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG). cGP/Ms 30D1 IgG had much better serum stability, suggesting that it was able to bind Fc receptors which recycle endocytosed IgG antibodies back to the cell surface. However, increased stability, generating a prolonged high HAI titer, did not enhance protection from viral transmission. Furthermore, in both Ms 30D1 IgG-treated guinea pigs and ferrets, upper respiratory tract replication appeared to be at most minimally impeded by systemic treatment of IgG, suggesting that the localization of IgG in the lung observed in SCID mice is likely conserved in both the wild-type guinea pig and wild-type ferret models. Thus, the inability of systemic Ms 30D1 IgG treatment to protect recipient guinea pigs and ferrets from transmission suggests that the initial site of transmission for influenza viruses is in the upper respiratory tract. Therefore, the focus was shifted to the ability of a recombinant 30D1 IgA (Ms 30D1 IgA) to prevent transmission to recipient guinea pigs.

The systemic treatment of Ms 30D1 IgA was shown to prevent transmission at a dose of 5 mg/kg, generating an HAI titer greater than 160, whereas a 5-fold-lower dose did not show any protection. Interestingly, this dose-dependent relationship was associated with IgA detection only in the nasal washes of guinea pigs treated with the protective dose. The ability of Ms 30D1 IgA to transport to the upper respiratory tract of a guinea pig may be explained by the conserved nature of J chains, which are functionally interchangeable across species (3). We also administered Ms 30D1 IgG directly to the upper respiratory tract to test if IgG in the correct location could also protect. As little as 900 ng of Ms 30D1 IgG applied only once to the upper respiratory tract 24 h prior to exposure was sufficient to prevent transmission to 100% of recipient guinea pigs; thus, the specific activity of IgA in the upper respiratory tract is likely defined by its ability to access the upper respiratory tract and not by other inherent differences between IgA and IgG antibodies. Finally, the ability to prevent transmission in guinea pigs by administering both IgG and IgA to the upper respiratory tract strongly suggests that the initial site of infection for transmission of influenza viruses is in the upper respiratory tract.

Studies have suggested that IgA is not necessary for neutralizing virus in the upper respiratory tract, as neonatal Fc receptors can transport IgG antibodies across mucosal membranes, and if given enough IgG intravenously, mouse infection can be prevented (1, 10, 30–32). While this mechanism may play a role in preventing influenza virus transmission, our data suggest it may only provide complete protection from transmission at an HAI titer greater than what is typically generated by current vaccines. Recently, Tudor et al. showed that changing the Fc portion of an HIV antibody from IgG to IgA enhanced affinity and antiviral activity (28). While this particular antibody is rather unique in its interaction with the lipid membrane and its epitope (33), we have tried to control for differences in affinity between IgG and IgA preparations. IgG antibodies were administered at higher doses than IgA antibodies, and HAI assays showed similar activity on a per microgram basis.

Inactivated influenza virus vaccines have been shown to be effective in humans in many independent studies (34); however, intramuscular vaccinations are not thought to generate a mucosal response or the production of IgA. Thus, in light of our recent findings, vaccination with inactivated influenza virus vaccines may better protect against illness than transmission of influenza virus. In fact, we have previously shown that guinea pigs receiving perfectly matched inactivated virus vaccines intramuscularly are still 100% susceptible to influenza virus transmission (16). We speculate that inactivated virus vaccines may limit illness by limiting lung replication while in many cases allowing upper respiratory replication to persist. Huang et al. showed in a human challenge study that not all individuals who were PCR positive for influenza virus in nasal swabs reported any symptoms (35). Thus, in these cases, individuals were infected without them noticing.

Our data demonstrate that IgA antibodies are sufficient to prevent transmission and are possibly better than IgG antibodies following systemic treatment. In children, the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) appears to be more efficacious than the inactivated trivalent intramuscular vaccination (36, 37). While LAIV-stimulated cellular immunity may be partially responsible for the increase in efficacy, these children likely generated a mucosal response, including the production of IgA in the upper respiratory tract. We speculate based on the current study that some of the enhanced efficacy observed in children receiving the LAIV was due to enhanced protection from transmission mediated by the production of IgA. It would be interesting to see if secretory IgA isolated from humans vaccinated with LAIV also prevents respiratory droplet transmission in the guinea pig model. IgA's ability to neutralize viruses delivered by airborne transmission to the upper respiratory tract and to prevent transmission has long been hypothesized based on mouse studies (1, 2). However, mice do not transmit influenza virus, and the mice in these studies were intranasally inoculated, which is not consistent with the way that community-acquired infections spread. In the present study, we have shown that IgA can prevent transmission in an animal model that is more representative of influenza virus spread among humans while showing a direct comparison with its parent IgG antibody, an IgG antibody which did not prevent transmission at similar HAI titers in both the guinea pig and ferret transmission models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thomas Moran for many helpful discussions. We also acknowledge Chen Wang and Richard Cadagan for excellent technical assistance over the course of the study.

F.K. was supported by an Erwin Schrödinger Fellowship (J 3232) from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF). This work was supported by CRIP, an NIH/NIAID-funded Center of Excellence on Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS) (contract HHSN266200700010C).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Renegar KB, Small PA, Boykins LG, Wright PF. 2004. Role of IgA versus IgG in the control of influenza viral infection in the murine respiratory tract. J. Immunol. 173:1978–1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mazanec MB, Lamm ME, Lyn D, Portner A, Nedrud JG. 1992. Comparison of IgA versus IgG monoclonal antibodies for passive immunization of the murine respiratory tract. Virus Res. 23:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johansen FE, Braathen R, Brandtzaeg P. 2000. Role of J chain in secretory immunoglobulin formation. Scand. J. Immunol. 52:240–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palladino G, Mozdzanowska K, Washko G, Gerhard W. 1995. Virus-neutralizing antibodies of immunoglobulin G (IgG) but not of IgM or IgA isotypes can cure influenza virus pneumonia in SCID mice. J. Virol. 69:2075–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scherle PA, Palladino G, Gerhard W. 1992. Mice can recover from pulmonary influenza virus infection in the absence of class I-restricted cytotoxic T cells. J. Immunol. 148:212–217 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ramphal R, Cogliano RC, Shands JW, Small PA. 1979. Serum antibody prevents lethal murine influenza pneumonitis but not tracheitis. Infect. Immun. 25:992–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Medina RA, Manicassamy B, Stertz S, Seibert CW, Hai R, Belshe RB, Frey SE, Basler CF, Palese P, García-Sastre A. 2010. Pandemic 2009 H1N1 vaccine protects against 1918 Spanish influenza virus. Nat. Comm. 1:28. 10.1038/nacomms1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mazanec MB, Nedrud JG, Lamm ME. 1987. Immunoglobulin A monoclonal antibodies protect against Sendai virus. J. Virol. 61:2624–2626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Renegar KB, Small PA. 1991. Immunoglobulin A mediation of murine nasal anti-influenza virus immunity. J. Virol. 65:2146–2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Renegar K, Small P. 1991. Passive transfer of local immunity to influenza virus infection by IgA antibody. J. Immunol. 146:1972–1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Tumpey TM, García-Sastre A, Palese P. 2006. The guinea pig as a transmission model for human influenza viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:9988–9992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schulman JL, Kilbourne ED. 1963. Experimental transmission of influenza virus infection in mice. II. Some factors affecting the incidence of transmitted infection. J. Exp. Med. 118:267–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schulman JL, Kilbourne ED. 1963. Experimental transmission of influenza virus infection in mice. I. The period of transmissibility. J. Exp. Med. 118:257–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herlocher ML, Elias S, Truscon R, Harrison S, Mindell D, Simon C, Monto AS. 2001. Ferrets as a transmission model for influenza: sequence changes in HA1 of type A (H3N2) virus. J. Infect. Dis. 184:542–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herlocher ML, Truscon R, Elias S, Yen HL, Roberts NA, Ohmit SE, Monto AS. 2004. Influenza viruses resistant to the antiviral drug oseltamivir: transmission studies in ferrets. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1627–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lowen AC, Steel J, Mubareka S, Carnero E, García-Sastre A, Palese P. 2009. Blocking interhost transmission of influenza virus by vaccination in the guinea pig model. J. Virol. 83:2803–2818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krammer F, Margine I, Tan GS, Pica N, Krause JC, Palese P. 2012. A carboxy-terminal trimerization domain stabilizes conformational epitopes on the stalk domain of soluble recombinant hemagglutinin substrates. PLoS One 7:e43603. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hai R, Schmolke M, Varga ZT, Manicassamy B, Wang TT, Belser JA, Pearce MB, García-Sastre A, Tumpey TM, Palese P. 2010. PB1-F2 expression by the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus has minimal impact on virulence in animal models. J. Virol. 84:4442–4450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fodor E, Devenish L, Engelhardt OG, Palese P, Brownlee GG, García-Sastre A. 1999. Rescue of influenza A virus from recombinant DNA. J. Virol. 73:9679–9682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Z, Raifu M, Howard M, Smith L, Hansen D, Goldsby R, Ratner D. 2000. Universal PCR amplification of mouse immunoglobulin gene variable regions: the design of degenerate primers and an assessment of the effect of DNA polymerase 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity. J. Immunol. Methods 233:167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith K, Garman L, Wrammert J, Zheng NY, Capra JD, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. 2009. Rapid generation of fully human monoclonal antibodies specific to a vaccinating antigen. Nat. Protoc. 4:372–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. VIDRL 2012. Reagents for the typing of human influenza isolates for 2012. Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory, Melbourne, Australia: http://www.influenzacentre.org/documents/publications_reports/reagent-kit-2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grossberg S. 1964. Human influenza A viruses: rapid plaque assay in hamster kidney cells. Science 144:1246–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seibert CW, Kaminski M, Philipp J, Rubbenstroth D, Albrecht RA, Schwalm F, Stertz S, Medina RA, Kochs G, García-Sastre A, Staeheli P, Palese P. 2010. Oseltamivir-resistant variants of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus are not attenuated in the guinea pig and ferret transmission models. J. Virol. 84:11219–11226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Seibert CW, Rahmat S, Krammer F, Palese P, Bouvier NM. 2012. Efficient transmission of pandemic H1N1 influenza viruses with high-level oseltamivir resistance. J. Virol. 86:5386–5389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Steel J, Palese P. 2007. Influenza virus transmission is dependent on relative humidity and temperature. PLoS Pathog. 3:e151. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bouvier NM, Rahmat S, Pica N. 2012. Enhanced mammalian transmissibility of seasonal influenza A/H1N1 viruses encoding an oseltamivir-resistant neuraminidase. J. Virol. 86:7268–7279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tudor D, Yu H, Maupetit J, Drillet Bouceba A-ST, Schwartz-Cornil I, Lopalco L, Tuffery P, Bomsel M. 2012. Isotype modulates epitope specificity, affinity, and antiviral activities of anti-HIV-1 human broadly neutralizing 2F5 antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:12680–12685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gerhard W, Mozdzanowska K, Furchner M, Washko G, Maiese K. 1997. Role of the B-cell response in recovery of mice from primary influenza virus infection. Immunol. Rev. 159:95–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dickinson BL, Badizadegan K, Wu Z, Ahouse JC, Zhu X, Simister NE, Blumberg RS, Lencer WI. 1999. Bidirectional FcRn-dependent IgG transport in a polarized human intestinal epithelial cell line. J. Clin. Invest. 104:903–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bai Y, Ye L, Tesar DB, Song H, Zhao D, Bjorkman PJ, Roopenian DC, Zhu X. 2011. Intracellular neutralization of viral infection in polarized epithelial cells by neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)-mediated IgG transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:18406–18411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Spiekermann GM, Finn PW, Ward ES, Dumont J, Dickinson BL, Blumberg RS, Lencer WI. 2002. Receptor-mediated immunoglobulin G transport across mucosal barriers in adult life: functional expression of FcRn in the mammalian lung. J. Exp. Med. 196:303–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ofek G, Tang M, Sambor A, Katinger H, Mascola JR, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. 2004. Structure and mechanistic analysis of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2F5 in complex with its gp41 epitope. J. Virol. 78:10724–10737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wright PF, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. 1997. Orthomyxoviruses, p 1691–1740 Knipe DM, Howley PM. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol II Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang Y, Zaas AK, Rao A, Dobigeon N, Woolf PJ, Veldman T, Oien NC, McClain MT, Varkey JB, Nicholson B, Carin L, Kingsmore S, Woods CW, Ginsburg GS, Hero AO., III 2011. Temporal dynamics of host molecular responses differentiate symptomatic and asymptomatic influenza A infection. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002234. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Belshe RB, Edwards KM, Vesikari T, Black SV, Walker RE, Hultquist M, Kemble G, Connor EM. 2007. Live attenuated versus inactivated influenza vaccine in infants and young children. N. Engl. J. Med. 356:685–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hoft DF, Babusis E, Worku S, Spencer CT, Lottenbach K, Truscott SM, Abate G, Sakala IG, Edwards KM, Creech CB, Gerber MA, Bernstein DI, Newman F, Graham I, Anderson EL, Belshe RB. 2011. Live and inactivated influenza vaccines induce similar humoral responses, but only live vaccines induce diverse T-cell responses in young children. J. Infect. Dis. 204:845–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]