Abstract

Upon infection with Bluetongue virus (BTV), an arthropod-borne virus, type I interferon (IFN-I) is produced in vivo and in vitro. IFN-I is essential for the establishment of an antiviral cellular response, and most if not all viruses have elaborated strategies to counteract its action. In this study, we assessed the ability of BTV to interfere with IFN-I synthesis and identified the nonstructural viral protein NS3 as an antagonist of the IFN-I system.

TEXT

Bluetongue virus (BTV) belongs to the Orbivirus genus of the Reoviridae family. It is a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus transmitted by blood-feeding midges of the genus Culicoides (1, 2). Ten segments of dsRNA constitute the viral genome, which encodes seven structural proteins (VP1 to -7) and five nonstructural proteins (NS1 to NS4 and NS3A) (3–5). BTV can infect a broad spectrum of wild and domestic ruminants and causes an economically important livestock disease that has spread across Europe in recent decades (6–10).

The innate immune response is the first line of defense against viruses. It involves the recognition of microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) by host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (11–14). The two major MAMPS that trigger an antiviral response during infection with RNA viruses are dsRNA and single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) molecules present in viral genomes or generated during viral replication. These MAMPs are mostly detected by membrane-bound Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and TLR7 or by RIG-I and MDA5, members of the RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) family (11, 15). Upon recognition, these PRRs recruit different adaptor proteins. TLR7 and TLR3 recruit MyD88 and TRIF, respectively (16), whereas RIG-I and MDA-5 recruit the mitochondrial adaptor MAVS protein (mitochrondrial activating signaling protein) via their caspase recruitment domains (CARDs) (17–19). A signal is then transduced to downstream kinases, including TBK1, IKKε, and the IKK complex, and transcription factors, such as interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) and IRF-7 or nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), are activated (20–24). These factors bind to specific promoters, initiating the production of type I IFN (IFN-I) and other proinflammatory cytokines (25). The secretion of IFN-I, composed mainly of IFN-α and -β, induces the expression of many gene products that are essential for the establishment of an antiviral state within infected cells and neighboring noninfected cells (25).

BTV is a strong inducer of IFN-I both in vivo and in vitro in multiple cell types derived from various tissues and species (26–35). Recently, we identified RIG-I and MDA5 helicases as sensors of BTV infection in nonhematopoietic cells and showed that these molecules displayed antiviral activities against the virus (26). Other PRRs are also able to sense BTV infection; it was shown that an MyD88-dependent TLR-independent pathway is preferentially used in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) (34). As IFN-I is detrimental for viral replication, most viruses have evolved mechanisms to counteract the host antiviral response triggered by infection. However, little is known about the ability of BTV to control these cellular defense mechanisms. In this study, we aimed to determine the ability of BTV and proteins encoded by the virus to interfere with the RLR signaling pathway that leads to IFN-I synthesis.

A luciferase reporter assay was first used to assess the effect of BTV infection on the activation of the IFN-β promoter. Human 293T cells were used to perform this assay, as reliable ovine and bovine cell culture systems that can be transfected efficiently are lacking.

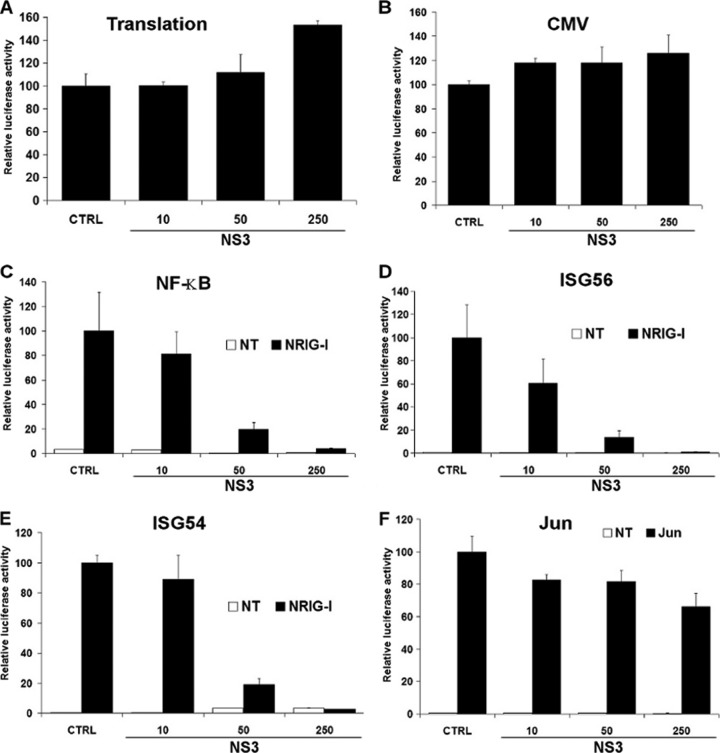

293T cells were infected with various amounts of a BTV-8 strain (isolated in France in Ardennes in 2006) and transfected 8 h postinfection (hpi) with an IFN-β reporter plasmid (pIFNβ-Luc), a control vector (pRSV-βGal) to normalize for transfection efficiency, and an expression vector (pNRIG-I) carrying genes for the constitutively active N-terminal CARDs of RIG-I (NRIG-I) fused to a FLAG tag. The transient expression of NRIG-I induced the activation of the IFN-β promoter in mock-infected cells, as expected, whereas this activation was greatly reduced in cells infected with BTV-8 (Fig. 1A). This result showed that BTV-8 is able to interfere with the activation of the IFN-β promoter after stimulation of the RLR pathway.

Fig 1.

Activation of the IFN-β promoter in cells infected with BTV or expressing different BTV ORFs. (A) 293T cells were infected with different amounts of BTV-8 (0.001 to 0.1 50% tissue culture infective dose/cell) as described previously (26) and transfected 8 hpi with 50 or 100 ng of the reporter plasmids pRSV-βGal and pIFNβ-Luc, respectively, and 200 ng of pNRIG-I. NI, noninfected (mock infected). (B) 293T cells were transfected as described for panel A, together with 250 ng of empty plasmid (CTRL) or a plasmid carrying the genes for Plk1-PBD or either 50 or 250 ng of plasmid carrying genes for each of the BTV-8 ORFs fused to a FLAG tag at their N-terminal end. In all the experiments presented in this report, the empty plasmid (CTRL) was added when required to transfect an equal amount of DNA under each condition. (C) 293T cells were transfected as for panel A together with an empty plasmid (CTRL) or a plasmid carrying genes for FLAG-NS3 from BTV-8 WT, BTV-1 WT, BTV-4 WT, BTV-4 VAC, BTV-2 WT, or BTV-2 VAC. For experiments in all three panels, cell lysates were harvested 16 h posttransfection and used to determine β-galactosidase and luciferase activities. Mean ratios between luciferase and β-galactosidase of triplicate samples (± standard deviations) are represented. Results are representative of one experiment and were reproduced in 2 to 3 independent experiments. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001 compared to NI (A), CTRL (B), or WT BTV-8 NS3 (C) (unpaired t tests with Welch's correction).

To determine whether one or several viral protein(s) are responsible for this inhibitory effect, we assessed the effect of BTV-8 open reading frames (ORFs) fused to a FLAG tag on the activity of the IFN-β promoter using the same reporter assay. As a control, we expressed the Polo-like kinase 1 Polo-box domain (Plk1-PBD), an antagonist of the RLR pathway (36). As shown in Fig. 1B, IFN-β promoter activation was impaired in cells overexpressing Plk1-PBD after stimulation with NRIG-I, as expected. A drastic inhibition of IFN-β promoter activity was observed in cells expressing the viral protein NS3 when either 50 or 250 ng of plasmids was used. VP3 and VP4 were also able to interfere with the action of NRIG-I, but only when 250 ng of plasmid was used for transfection. As differences in the levels of expression of the BTV ORFs were observed by Western blotting (data not shown), it is difficult to compare the respective antagonist activities of the different viral proteins, and we cannot exclude that other BTV proteins are strong inhibitors of IFN-β promoter activity.

Since we identified NS3 as a potent inhibitor of IFN-β promoter activation, we decided to assess further its inhibitory effect. First, we determined the ability of FLAG-tagged NS3s from other BTV serotypes to inhibit IFN-β promoter activity. NS3s from field/wild-type (WT) strains of BTV-1 (isolated in southwest France in 2007), BTV-2 (isolated in Corsica in 2000), and BTV-4 (isolated in Corsica in 2003) were also able to efficiently inhibit the activation of the IFN-β promoter after stimulation with NRIG-I (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, live vaccine strains (VAC) of BTV-2 and -4 (isolated in South Africa and passaged 50 to 60 times on BHK-21 cells) were also able to block this activation. Thus, the ability of NS3 to inhibit the IFN-β synthesis pathway is conserved between serotypes and strains of BTV.

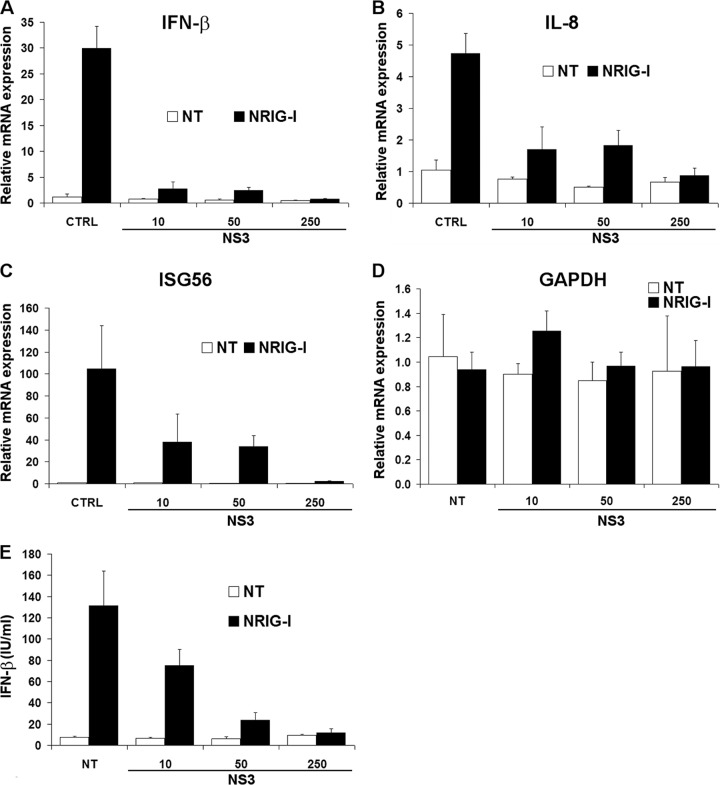

Since a reporter assay was used to assess the effect of NS3 on IFN-β promoter activity, we cannot exclude that the viral protein modulates translation. To determine whether NS3 affects this step, we transfected cells with in vitro-transcribed and purified mRNAs encoding the luciferase protein prepared as described in reference37. As shown in Fig. 2A, the expression of increasing amounts of NS3 did not block luciferase activity, showing that NS3 does not interfere with translation. To determine whether NS3 has a global effect on transcription, we assessed the effect of its expression on the activity of other promoters. Cytomegalovirus (CMV)-dependent transcription was not inhibited by NS3 (Fig. 2B), showing that NS3 does not induce a complete transcriptional shutoff and is not cytotoxic for the cells. Using a pUAS-Gal4-Luc construct (37), we also assessed the effect of NS3 on transcription driven by c-Jun, a transcription factor involved in the expression of multiple genes. No inhibition in Jun-dependent transcription was observed in the presence of FLAG-NS3 (Fig. 2F), confirming that NS3 does not affect global transcription or a broad range of promoters. Upon stimulation with NRIG-I, NS3 repressed the activation of the luciferase reporter gene under the control of NF-κB elements (Fig. 2C) or natural promoters from IFN-stimulated genes ISG54 and ISG56 (Fig. 2D and E). These results showed that NS3 modulates the activation of specific promoters induced upon activation of the RLR pathway.

Fig 2.

Effects of NS3 on translation and activity of different promoters. (A) 293T cells were transfected with 50 ng of pRSV-βGal, 1 μg of luciferase transcripts, and 250 ng of empty plasmid (CTRL) or 10, 50, or 250 ng of a plasmid carrying genes for FLAG-NS3 of BTV-8. (B to F) 293T cells were transfected with 50 ng of pRSV-βGal and 250 ng of empty plasmid (CTRL) or 10, 50, or 250 ng of a plasmid carrying genes for FLAG-NS3 of BTV-8 together with 100 ng of the luciferase reporter plasmids pCMV-Luc (B), pNF-κB-Luc (C), pISG56-Luc (D), pISG54-Luc (E), or pUAS-Gal4-Luc (F). In addition, 200 ng of pNRIG-I (C to E) or 300 ng of pMT-Jun (F), carrying genes for the Jun protein fused to the ADN binding domain of Gal4, was transfected simultaneously to activate the corresponding promoters. For the experiments in all the panels (A to F), cell lysates were harvested 16 h posttransfection and used to determine β-galactosidase and luciferase activities. Mean ratios between luciferase and β-galactosidase activities of triplicate samples were calculated and are presented as percentages of the control (A and B) or stimulated control (C to F) (± standard deviations). Results are representative of one experiment and were reproduced in two to three independent experiments.

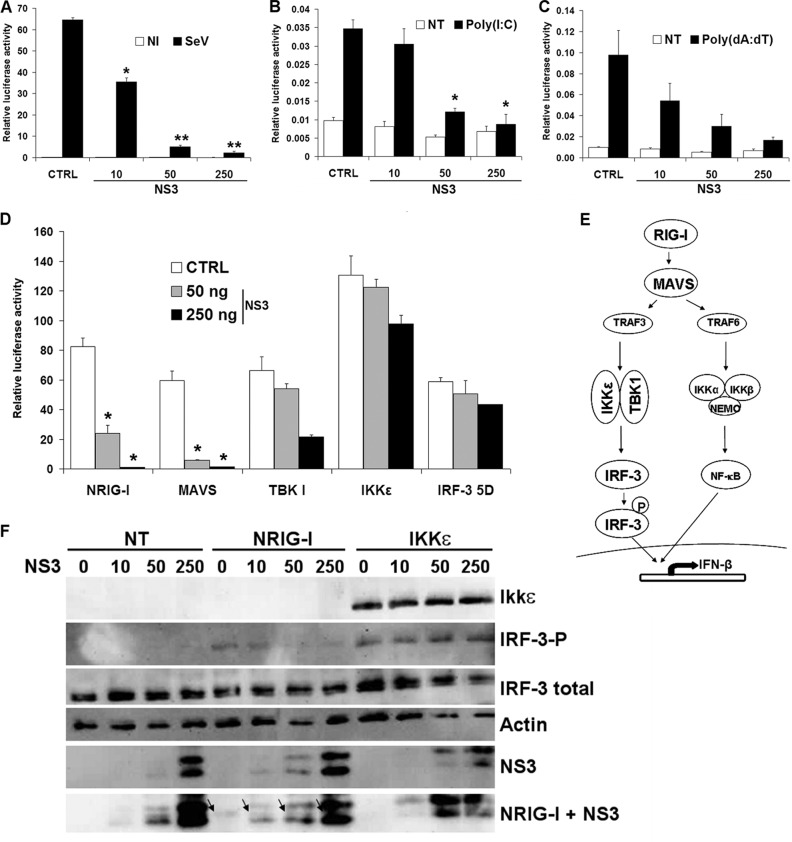

To confirm that NS3 affects the transcription of the IFN-β gene at an endogenous level, we performed reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR). Upon activation with NRIG-I, the level of IFN-β mRNA transcripts was dramatically reduced in the presence of NS3 (Fig. 3A), confirming that NS3 interferes with the expression of IFN-β. We also found that NS3 inhibited the expression of the NF-κB-dependent gene IL-8 and the IFN-stimulated gene ISG56 (Fig. 3B and C). However, NS3 did not affect the level of expression of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Fig. 3D). Additionally, we performed an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and found that the quantity of IFN-β protein secreted after stimulation by NRIG-I was decreased in cells expressing FLAG-NS3 (Fig. 3E). These results showed that NS3 is able to inhibit the production of IFN-β and to modulate the expression of genes activated by the RLR pathway.

Fig 3.

Effects of NS3 on the expression of genes involved in the antiviral response. 293T cells were cotransfected with 250 ng of an empty plasmid (CTRL) or 10 to 250 ng of plasmid carrying the genes for FLAG-NS3 of BTV-8 and stimulated with 200 ng of pNRIG-I or left untreated (NT). Total RNA was extracted from cells, and the level of expression of IFN-β (A), interleukin-8 (IL-8) (B), ISG56 (C), and GAPDH (D) mRNAs were determined by RT-qPCR and normalized against the level of expression of actin mRNA, as described previously (26). (E) Supernatants were collected to determine IFN-β secretion (in IU/ml) by using the HuIFN-β ELISA kit (Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan). Results shown are means (± standard deviations) from triplicate samples and were reproduced in 2 independent experiments.

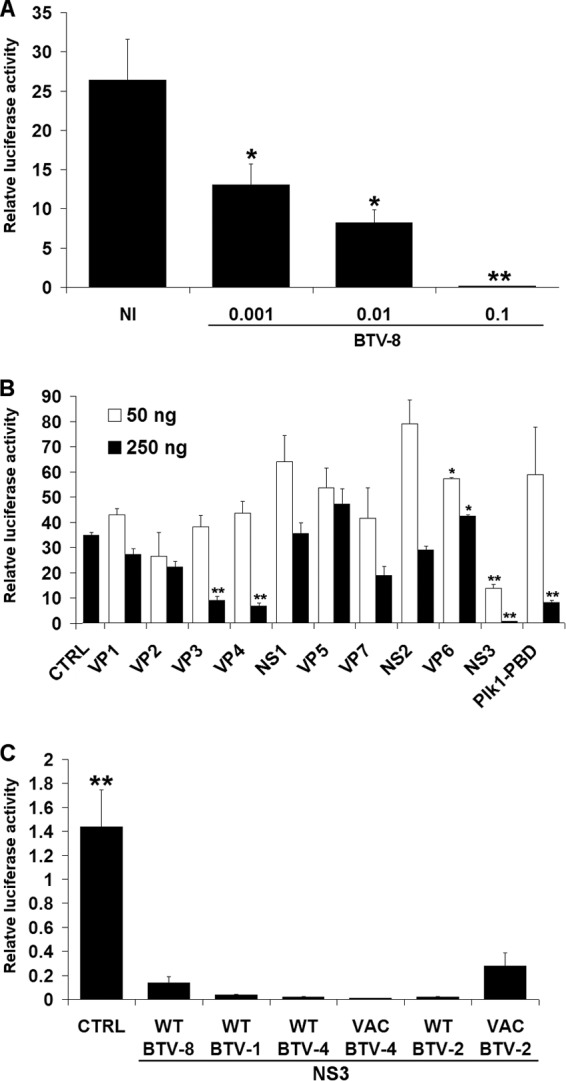

To confirm that NS3 blocks the activation of the IFN-β promoter after stimulation of the RLR pathway, we stimulated cells expressing different amounts of FLAG-NS3 with other agonists of this signaling pathway: Sendai virus (SeV; an RNA virus), poly(I·C) (synthetic dsRNA), and poly(dA-dT) (transcribed to dsRNA by RNA polymerase III) (Fig. 4A to C). NS3 was able to block the activation of the IFN-β promoter induced by these three stimuli, confirming the results obtained with NRIG-I. To understand better at which stage of the RLR pathway (Fig. 4E) NS3 acts, we overexpressed MAVS, TBK1, IKKε, and IRF-3 5D (a constitutively active form of IRF-3) for activation of the IFN-β promoter. As shown in Fig. 4D, NS3 was able to inhibit dramatically the stimulating effect of MAVS. However, this inhibitory effect was considerably reduced or absent after overexpression of TBK1, IKKε, or IRF-3 5D. This suggests that NS3 interferes at least with signal transduction to the TBK-1/IKKε complex after activation of RIG-I and MAVS. To confirm these results, Western blot analysis was used to assess IRF-3 phosphorylation in cells expressing NS3 and NRIG-I or IKKε (Fig. 4F). The phosphorylated form of IRF-3 was detected in cells expressing NS3 after stimulation with IKKε but not NRIG-I. This result is in accordance with the data obtained in the reporter assay, confirming that NS3 is able to interfere with the IFN synthesis pathway downstream of RIG-I and upstream of IKKε activation. More work is in progress to determine more precisely the mode of action of NS3 and the cellular proteins involved.

Fig 4.

Effects of NS3 on IFN-β promoter activation and IRF-3 phosphorylation after stimulation with different agonists of the RLR signaling pathway. 293T cells were transfected with 50 ng of pRSV-βGal, 100 ng of pIFNβ-Luc, and 250 ng of empty plasmid (CTRL) or 10 to 250 ng of a plasmid carrying genes for BTV-8 FLAG-NS3. The IFN-β promoter was activated by infection with 20 hemagglutinating units/ml of SeV H4 for 8 h (A) or by transfection of 2 μg of poly(I·C) (B) or 2 μg of poly(dA-dT) (C), or by transfection of plasmids carrying genes for NRIG-I (200 ng), MAVS (10 ng), TBK1 (200 ng), IKKε (100 ng), or IRF-3 5D (300 ng) (D) for 16 h. Cells were harvested and used to determine β-galactosidase and luciferase activities. Mean ratios between luciferase and β-galactosidase activities of triplicate samples (± standard deviations) are shown (A to C), or the results are presented as the of the ratio obtained for cells transfected with the reporter and inducer plasmids only (D). Results are representative of one experiment and were reproduced in two to three independent experiments. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001 (compared to CTRL, using unpaired t tests with Welch's correction). (E) Overview of the RLR signaling pathway. After activation of RIG-I, MAVS is recruited and initiates different signaling cascades, leading to the activation of the transcription factors IRF-3 and NF-κB and the subsequent expression of IFN-β. (F) 293T cells were transfected with 250 ng of empty plasmid (lane 0) or 10 to 250 ng of a plasmid carrying genes for FLAG-NS3 of BTV-8 and a plasmid carrying genes for NRIG-I or IKKε fused to a FLAG tag. Cells were lysed 16 h posttransfection, and equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE as described previously (26). Total (FL-425 antibody; sc9082; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and phosphorylated (4D4G; Cell Signaling) IRF-3 were detected by immunoblotting. The expression of NS3 was detected by using a polyclonal rabbit antibody (38), FLAG-IKKε and FLAG-NRIG-I were visualized using an anti-FLAG antibody (clone M2; Sigma-Aldrich), and the level of actin (clone AC-40; Sigma-Aldrich) was determined to control for equal loading. The bands corresponding to NRIG-I are marked by black arrows and are surrounded by bands corresponding to FLAG-tagged NS3, as the two proteins have a similar molecular weight.

In conclusion, our data provide evidence that NS3 of BTV interferes with the induction of the innate immune response in nonhematopoietic cells by inhibiting the RLR-dependent signaling pathway. Thus, BTV has evolved at least one strategy to interfere with the production of IFN-I. A balance most likely exists between the ability of the host to trigger the production of IFN-I and respond to it versus the ability of viruses to block this antiviral signaling pathway. It is then possible that without the inhibitory activity of NS3, a virus would induce the synthesis of even more IFN-I. As BTV is recognized by different PRRs depending on the cell type (26, 34), it is possible that its ability to block the production of IFN-I is cell type specific. Different viral proteins might be required, depending on the signaling pathways triggered by the viral infection. It will be interesting to determine in further studies how broadly NS3 acts as a repressor of IFN-I production and assess its antagonist activity in different types of cells, after the stimulation of different signaling pathways. A better understanding of the mode of action of NS3 and other mechanisms that have evolved in BTV to counteract the host cellular response will give essential insights into the pathogenesis associated with BTV infection and will help to generate better prophylactic tools to control the virus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by ANSES, INRA, ENVA, and the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche through the EMIDA ORBINET consortium (K1303206). Emilie Chauveau received a Ph.D. grant from ANSES and INRA.

We thank Frederick Arnaud, John Hiscott, Frédéric Tangy, Yves Jacob, and Benoît Durand for providing reagents and for useful discussions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Mellor PS, Boorman J, Baylis M. 2000. Culicoides biting midges: their role as arbovirus vectors. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 45:307–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tabachnick WJ. 2004. Culicoides and the global epidemiology of bluetongue virus infection. Vet. Ital. 40:144–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Belhouchet M, Mohd Jaafar F, Firth AE, Grimes JM, Mertens PP, Attoui H. 2011. Detection of a fourth orbivirus non-structural protein. PLoS One 6:e25697. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ratinier M, Caporale M, Golder M, Franzoni G, Allan K, Nunes SF, Armezzani A, Bayoumy A, Rixon F, Shaw A, Palmarini M. 2011. Identification and characterization of a novel non-structural protein of bluetongue virus. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002477. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roy P. 2005. Bluetongue virus proteins and particles and their role in virus entry, assembly, and release. Adv. Virus Res. 64:69–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maclachlan NJ. 2011. Bluetongue: history, global epidemiology, and pathogenesis. Prev. Vet. Med. 102:107–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Purse BV, Mellor PS, Rogers DJ, Samuel AR, Mertens PP, Baylis M. 2005. Climate change and the recent emergence of bluetongue in Europe. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saegerman C, Mellor P, Uyttenhoef A, Hanon JB, Kirschvink N, Haubruge E, Delcroix P, Houtain JY, Pourquier P, Vandenbussche F, Verheyden B, De Clercq K, Czaplicki G. 2010. The most likely time and place of introduction of BTV8 into Belgian ruminants. PLoS One 5:e9405. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schwartz-Cornil I, Mertens PP, Contreras V, Hemati B, Pascale F, Breard E, Mellor PS, MacLachlan NJ, Zientara S. 2008. Bluetongue virus: virology, pathogenesis and immunity. Vet. Res. 39:46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walton TE. 2004. The history of bluetongue and a current global overview. Vet. Ital. 40:31–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124:783–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kawai T, Akira S. 2008. Toll-like receptor and RIG-I-like receptor signaling. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1143:1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, Moradpour D, Binder M, Bartenschlager R, Tschopp J. 2005. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature 437:1167–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoneyama M, Fujita T. 2009. RNA recognition and signal transduction by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunol. Rev. 227:54–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beutler B, Eidenschenk C, Crozat K, Imler JL, Takeuchi O, Hoffmann JA, Akira S. 2007. Genetic analysis of resistance to viral infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7:753–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, Akira S. 2003. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science 301:640–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, Coban C, Kumar H, Kato H, Ishii KJ, Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2005. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat. Immunol. 6:981–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Chen ZJ. 2005. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-κB and IRF 3. Cell 122:669–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu LG, Wang YY, Han KJ, Li LY, Zhai Z, Shu HB. 2005. VISA is an adapter protein required for virus-triggered IFN-beta signaling. Mol. Cell 19:727–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, Rowe DC, Latz E, Golenbock DT, Coyle AJ, Liao SM, Maniatis T. 2003. IKKε and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 4:491–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yamamoto M, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Kawai T, Hoshino K, Takeda K, Akira S. 2004. The roles of two IκB kinase-related kinases in lipopolysaccharide and double stranded RNA signaling and viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 199:1641–1650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McWhirter SM, Fitzgerald KA, Rosains J, Rowe DC, Golenbock DT, Maniatis T. 2004. IFN-regulatory factor 3-dependent gene expression is defective in Tbk1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:233–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sasai M, Matsumoto M, Seya T. 2006. The kinase complex responsible for IRF-3-mediated IFN-beta production in myeloid dendritic cells (mDC). J. Biochem. 139:171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sharma S, tenOever BR, Grandvaux N, Zhou GP, Lin R, Hiscott J. 2003. Triggering the interferon antiviral response through an IKK-related pathway. Science 300:1148–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Randall RE, Goodbourn S. 2008. Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 89:1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chauveau E, Doceul V, Lara E, Adam M, Breard E, Sailleau C, Viarouge C, Desprat A, Meyer G, Schwartz-Cornil I, Ruscanu S, Charley B, Zientara S, Vitour D. 2012. Sensing and control of bluetongue virus infection in epithelial cells via RIG-I and MDA5 helicases. J. Virol. 86:11789–11799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Foster NM, Luedke AJ, Parsonson IM, Walton TE. 1991. Temporal relationships of viremia, interferon activity, and antibody responses of sheep infected with several bluetongue virus strains. Am. J. Vet. Res. 52:192–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fulton RW, Pearson NJ. 1982. Interferon induction in bovine and feline monolayer cultures by four bluetongue virus serotypes. Can. J. Comp. Med. 46:100–102 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hemati B, Contreras V, Urien C, Bonneau M, Takamatsu HH, Mertens PP, Breard E, Sailleau C, Zientara S, Schwartz-Cornil I. 2009. Bluetongue virus targets conventional dendritic cells in skin lymph. J. Virol. 83:8789–8799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huismans H. 1969. Bluetongue virus-induced interferon synthesis. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 36:181–185 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jameson P, Grossberg SE. 1979. Production of interferon by human tumor cell lines. Arch. Virol. 62:209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jameson P, Schoenherr CK, Grossberg SE. 1978. Bluetongue virus, an exceptionally potent interferon inducer in mice. Infect. Immun. 20:321–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacLachlan NJ, Thompson J. 1985. Bluetongue virus-induced interferon in cattle. Am. J. Vet. Res. 46:1238–1241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ruscanu S, Pascale F, Bourge M, Hemati B, Elhmouzi-Younes J, Urien C, Bonneau M, Takamatsu H, Hope J, Mertens P, Meyer G, Stewart M, Roy P, Meurs EF, Dabo S, Zientara S, Breard E, Sailleau C, Chauveau E, Vitour D, Charley B, Schwartz-Cornil I. 2012. The double-stranded RNA Bluetongue virus induces type I interferon in plasmacytoid dendritic cells via a MYD88-dependent TLR7/8-independent signaling pathway. J. Virol. 86:5817–5828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Russell H, O'Toole DT, Bardsley K, Davis WC, Ellis JA. 1996. Comparative effects of bluetongue virus infection of ovine and bovine endothelial cells. Vet. Pathol. 33:319–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vitour D, Dabo S, Ahmadi Pour M, Vilasco M, Vidalain PO, Jacob Y, Mezel-Lemoine M, Paz S, Arguello M, Lin R, Tangy F, Hiscott J, Meurs EF. 2009. Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) regulates interferon (IFN) induction by MAVS. J. Biol. Chem. 284:21797–21809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bourai M, Lucas-Hourani M, Gad HH, Drosten C, Jacob Y, Tafforeau L, Cassonnet P, Jones LM, Judith D, Couderc T, Lecuit M, Andre P, Kummerer BM, Lotteau V, Despres P, Tangy F, Vidalain PO. 2012. Mapping of Chikungunya virus interactions with host proteins identified nsP2 as a highly connected viral component. J. Virol. 86:3121–3134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shaw AE, Veronesi E, Maurin G, Ftaich N, Guiguen F, Rixon F, Ratinier M, Mertens P, Carpenter S, Palmarini M, Terzian C, Arnaud F. 2012. Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism for bluetongue virus replication and tropism. J. Virol. 86:9015–9024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]