Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) are currently a promising treatment strategy against Ebola virus infection. This study combined MAbs with an adenovirus-vectored interferon (DEF201) to evaluate the efficacy in guinea pigs and extend the treatment window obtained with MAbs alone. Initiating the combination therapy at 3 days postinfection (d.p.i.) provided 100% survival, a significant improvement over survival with either treatment alone. The administration of DEF201 within 2 d.p.i. permits later MAb use, with protective efficacy observed up to 8 d.p.i.

TEXT

Ebola virus is one of the most virulent human pathogens, and infection with the Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV) species results in up to 90% mortality (1). Ebola outbreaks are mostly concentrated in remote areas of sub-Saharan Africa (2), but evidence of prior Ebola infection of swine in the Philippines (3), the presence of Ebola virus antibodies among orangutans in Indonesia (4) and bats in China (5), and the existence of an Ebola virus-like filovirus among European insectivorous bats (6) indicates that Ebola virus may be more widespread than previously thought. Since pigs have been established as a new intermediate host for Ebola (3), with effective transmission to nonhuman primates (NHPs) (7), there is the potential for Ebola to overwhelm larger populations should the virus be introduced in more-populous areas. Therefore, preventative and therapeutic strategies need to be developed to protect the population at large.

While several prophylactic vaccine candidates against EBOV have shown preclinical promise in NHPs (8), the options for postexposure intervention are limited. A major reason is that EBOV typically kills its host within 6 to 10 days after the onset of symptoms (8), thereby providing a very small window for intervention before death from multiple organ failure. A recent promising treatment is a combination of three Ebola virus glycoprotein-specific murine monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), 1H3, 2G4, and 4G7, that protects 100% and 50% of NHPs when administered 24 and 48 h, respectively, after lethal EBOV infection (9–11). Another combination of chimeric humanized MAbs produced in plants was also able to save lethally infected NHPs, with 2 of 3 infected animals surviving when the MAbs were administered either 24 or 48 h after EBOV challenge (12). These findings constitute a substantial improvement in the length of the therapeutic window over previous postexposure strategies, which required administration within 60 min of exposure to EBOV in order to result in at least partial survival of NHPs. Ideally, an optimized treatment would be capable of saving infected individuals even when given hours before death.

DEF201 is a replication-defective recombinant human adenovirus of serotype 5 (AdHu5) expressing consensus human alpha interferon (IFN-α) (13). It was previously investigated as a broad-spectrum antiviral and shown to be effective against several viral pathogens (14–18). While IFN-α treatment has been associated with various amounts of toxicity in the past, these adverse effects are mostly due to the short half-life of the protein, thereby necessitating extremely high doses in order to have a biologically relevant impact. Adenovirus-vectored administration of the IFN-α gene allows for steady delivery of the protein, which avoids the bolus dose effect of recombinant IFN-α. Safety and toxicity studies on DEF201 in rodents indicate tolerability meeting regulatory requirements. Furthermore, combination studies to increase the effectiveness of an adenovirus-based EBOV vaccine showed that DEF201 was superior to all other interventions tested in improving survival, due to its ability to enhance the EBOV-specific adaptive immune response, hamper EBOV replication, and produce high levels of IFN-α for days in a cost-effective manner (19). Combining a broad-spectrum intervention with an EBOV-specific therapy may extend the treatment window while enhancing survival beyond the current limits. The main goal of this study was to evaluate the combination of MAbs (9–11) with DEF201 against EBOV in guinea pigs and establish a number of relevant parameters, such as the optimal dosage and timing of treatments, in order to develop a similarly effective therapy for NHPs and humans.

The two treatments were first tested separately to generate the baseline levels of protection. After lethal intraperitoneal (i.p.) challenge with 1,000 times the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of guinea pig-adapted Zaire ebolavirus (GA-ZEBOV), strain Mayinga (20), guinea pigs were treated either intramuscularly (i.m.) with 2 × 108 PFU DEF201 per animal 1 day postinfection (d.p.i.) or i.p. with equal amounts of 1H3, 2G4, and 4G7 MAbs totaling 10 mg per animal 3 d.p.i. (Table 1). The phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-treated controls suffered rapid weight loss and decreased activity, resulting in uniform lethality between 6 and 9 d.p.i. While the mean time to death was significantly extended by DEF201 alone, it failed to provide survival to the animals. MAbs were partially protective, with 33% of animals surviving infection, which was lower than the rate in previously published data (11), possibly due to the use of a different MAb preparation for these studies or to the inherent genetic variation among outbred Hartley guinea pigs. The difference between the two studies (33% and 67%) is not statistically significant (P value = 2.01E−01). The results suggest that each strategy interferes with EBOV-induced mortality but is insufficient for complete survival under these conditions. The protective effects of these two strategies were then evaluated in combination. Guinea pigs were given DEF201 and 10 mg of MAbs per animal as separate injections either 3 or 4 d.p.i., resulting in significantly improved survival, to 100% and 50%, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). Replacing DEF201 with AdHu5 expressing lacZ (AdHu5-lacZ) failed to significantly improve the MAb-based protection, highlighting the added specific contribution of IFN-α to survival as opposed to an unspecific effect from an innate immune response triggered by the AdHu5 vector (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Increased survival and extended postexposure treatment window in guinea pigs

| Expt | Treatment (amt in mg) | Time of treatment (d.p.i.) with: |

Mean time to death ± SD (no. of animals that died) | No. of survivors/total no. in groupc | P valued | Avg wt loss (%)e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEF201a | MAbsb | ||||||

| 1 | PBS | 7.17 ± 0.75 (6) | 0/6 | NAf | 18 | ||

| MAbs only (10) | 3 | 9.75 ± 0.96 (4) | 2/6 | 8.00E−04 | 8 | ||

| DEF201 only | 1 | 10.33 ± 1.03 (6) | 0/6 | 8.00E−04 | 25 | ||

| AdHu5-lacZ+MAbs (10) | 3 | 3 | 11.50 ± 3.70 (4) | 2/6 | 8.00E−04 | <5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 3 | 3 | NA | 6/6 | 8.00E−04 | <5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 4 | 4 | 14.33 ± 2.08 (3) | 3/6 | 8.00E−04 | 10 | |

| 2 | PBS | 7.33 ± 0.82 (6) | 0/6 | NA | 16 | ||

| AdHu5-lacZ+MAbs (10) | 1 | 6 | 7.50 ± 0.84 (6) | 0/6 | 7.37E−01 | 22 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 1 | 4 | NA | 6/6 | 1.00E−03 | <5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 1 | 5 | NA | 6/6 | 1.00E−03 | <5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 1 | 6 | NA | 6/6 | 1.00E−03 | 8 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 1 | 7 | NA | 6/6 | 1.00E−03 | 16 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 1 | 8 | 14 (1) | 5/6 | 1.00E−03 | 21 | |

| 3 | PBS | 7.33 ± 1.21 (6) | 0/6 | NA | 15 | ||

| DEF201 only | 2 | 10.17 ± 0.75 (6) | 0/6 | 1.30E−03 | 30 | ||

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 2 | 4 | NA | 6/6 | 6.00E−04 | <5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 2 | 5 | NA | 6/6 | 6.00E−04 | 7 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 2 | 6 | 10.25 ± 1.71 (4) | 2/6 | 2.90E−03 | 23 | |

| 4 | PBS | 7.50 ± 0.55 (6) | 0/6 | NA | 16 | ||

| MAbs only (5) | 3 | 9.17 ± 2.14 (6) | 0/6 | 5.53E−02 | 31 | ||

| DEF201+MAbs (5) | 3 | 3 | 11.60 ± 2.19 (5) | 1/6 | 9.00E−04 | 21 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (5) | 2 | 3 | 8 (1) | 5/6 | 3.40E−03 | 5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (5) | 1 | 3 | NA | 6/6 | 9.00E−04 | <5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (5) | 1 | 4 | NA | 6/6 | 9.00E−04 | <5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (5) | 1 | 5 | NA | 6/6 | 9.00E−04 | <5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (5) | 1 | 6 | 14 (1) | 5/6 | 9.00E−04 | 9 | |

Guinea pigs were treated intramuscularly with DEF201 or AdHu5-lacZ (2 × 108 PFU) at the indicated number of days postinfection (d.p.i.) with 1,000× LD50 of GA-ZEBOV.

Guinea pigs were treated intraperitoneally with 5 or 10 mg total MAbs at the indicated d.p.i.

Survival rates on day 28 after challenge.

The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to calculate the P values. All treatment groups were compared to the corresponding PBS control group.

Average of the maximum weight loss from the original weights on the challenge date.

NA, not applicable.

Table 2.

Statistical comparison of DEF201 and AdHu5-lacZ treatments

| Expt | Reference treatment (amt in mg) | Time of treatment (d.p.i.) |

Test treatment (amt in mg) | Time of treatment (d.p.i.) |

P valuec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEF201a | MAbsb | DEF201a | MAbsb | ||||

| 1 | MAbs only (10) | 3 | AdHu5-lacZ+MAbs (10) | 3 | 3 | 8.36E−01 | |

| MAbs only (10) | 3 | DEF201+MAbs (10) | 3 | 3 | 1.79E−02 | ||

| AdHu5-lacZ+MAbs (10) | 3 | 3 | DEF201+MAbs (10) | 3 | 3 | 1.85E−02 | |

| 2 | AdHu5-lacZ+MAbs (10) | 1 | 6 | DEF201+MAbs (10) | 1 | 6 | 4.00E−04 |

Guinea pigs were treated intramuscularly with DEF201 or AdHu5-lacZ (2 × 108 PFU) at the indicated number of days postinfection (d.p.i.) with 1,000× LD50 of GA-ZEBOV.

Guinea pigs were treated intraperitoneally with 10 mg total MAbs at the indicated d.p.i.

The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to calculate the P values.

Earlier administration of DEF201 allows for significant delays in the timing of MAb treatment. Animals were given DEF201 either 1 or 2 d.p.i., followed by a single treatment of 10 mg of MAbs per animal at up to 8 d.p.i. (Table 1). Complete survival was observed for animals given MAbs within 7 and 5 d.p.i. if DEF201 was administered 1 and 2 d.p.i., respectively. Dose sparing of MAbs was also protective, with complete survival observed when guinea pigs were given equal amounts of 1H3, 2G4, and 4G7 MAbs totaling 5 mg per animal within 5 d.p.i. after DEF201 administration at 1 d.p.i. As expected, early AdHu5-lacZ administration in place of DEF201 did not significantly extend the treatment window (Tables 1 and 2).

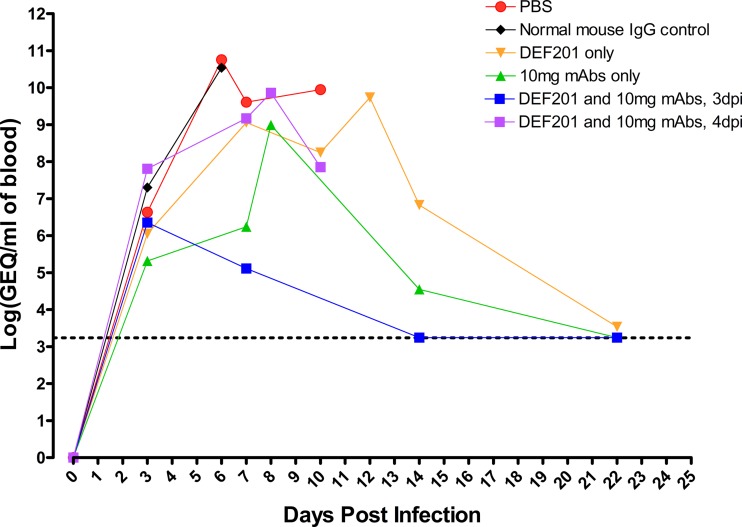

EBOV was detected by real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR of the blood of infected animals in selected treatment groups at 0, 3, 7, 14, and 22 d.p.i., in addition to terminal bleed samples on moribund animals (Fig. 1), and the level of viremia was found to correlate with survival (Table 3). PBS and IgG controls demonstrated peak average viremia levels of ∼1011 genome equivalents (GEQ)/ml of blood 6 d.p.i. Single DEF201 and 10-mg-MAb treatments were both able to delay and suppress viremia, with a 0.5- and a 3.5-log decrease, respectively, at 7 d.p.i. and peak average viremia reaching ∼1010 and ∼109 GEQ/ml, respectively. Combined DEF201 and MAb treatment at 3 d.p.i. strongly suppressed viral replication, as measured by a 4.5-log decrease in viremia at 7 d.p.i. and peak average viremia reaching ∼106 GEQ/ml. Surviving animals recovered fully from the disease, with undetectable viremia by 22 d.p.i. It is notable that the single-MAb-treatment group of 4 animals yielded 3 survivors, which is higher than previously described; however, this difference was not found to be statistically significant (P value = 3.48E−01).

Fig 1.

EBOV viremia at various times postchallenge as measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Average viremia levels for guinea pigs from various treatment groups, summarized in Table 3, at different time points after Ebola virus infection are shown. The dotted line represents the limit of detection (1,750 GEQ/ml of blood). Error bars are omitted for figure clarity. Averages were calculated from log-transformed data.

Table 3.

Survival of guinea pigs tested for viremia levels

| Treatment (amt in mg) | Time of treatment (d.p.i.) |

Mean time to death ± SD (no. of animals that died) | No. of survivors/total no. in groupc | P valued | Avg wt loss (%)e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEF201a | MAbsb | |||||

| PBS | 7.75 ± 0.96 (4) | 0/4 | NAf | 13 | ||

| Normal mouse IgG control | 3 | 7.00 ± 0.00 (4) | 0/4 | 1.27E−01 | 18 | |

| DEF201 only | 1 | 11.00 ± 1.00 (3) | 1/4 | 6.20E−03 | 16 | |

| MAbs only (10) | 3 | 8 (1) | 3/4 | 3.46E−02 | <5 | |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 3 | 3 | NA | 4/4 | 6.20E−03 | <5 |

| DEF201+MAbs (10) | 4 | 4 | 9.00 ± 1.15 (4) | 0/4 | 1.04E−01 | 22 |

Guinea pigs were treated intramuscularly with DEF201 or AdHu5-lacZ (2 × 108 PFU) at the indicated number of days postinfection (d.p.i.) with 1,000× LD50 of GA-ZEBOV.

Guinea pigs were treated intraperitoneally with 5 or 10 mg total MAbs at the indicated d.p.i.

Survival rates on day 28 after challenge.

The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to calculate the P values. All treatment groups were compared to the corresponding PBS control group.

Average of the maximum weight loss from the original weights on the challenge date.

NA, not applicable.

The general symptoms of early EBOV infection resemble those of more-common pathogenic diseases, such as malaria, cholera, typhoid, or even other African hemorrhagic fevers, including Marburg, Rift Valley fever, and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (21), making differential diagnosis difficult. By the time positive cases are confirmed via quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) or serology (22, 23), it is already too late to intervene with previously described experimental treatment options, with the exception of MAbs. The results reported here demonstrate for the first time complete protection against lethal EBOV infection when treatment is initiated as late as 3 d.p.i. in guinea pigs, when EBOV was detectable by qRT-PCR. Interestingly, rapid administration of DEF201 resulted in complete survival provided that specific MAbs were administered within 7 d.p.i., with partial survival observed for treatment at 8 d.p.i. Since DEF201 may be cost effective to use as a broad-spectrum antiviral, this treatment protocol could offer an additional tool to successfully manage suspected infections due to a presumed accidental exposure in a laboratory or treatment center, as well as close contacts of confirmed cases in outbreak situations. Confirmed EBOV infection could then be treated with specific MAbs at later time points, presumably as late as 2 days preceding death. This combination therapy holds promise for the treatment of EBOV infection in NHPs and humans and can likely be adapted against other filoviruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jason Gren for his excellent technical assistance.

This research was funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and a grant from the Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) Research and Technology Initiative (CRTI) to G.P.K. G.W. is the recipient of a doctoral research award from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR).

Competing interests include the following: Her Majesty the Queen in right of Canada holds a patent on the monoclonal antibodies 1H3, 2G4, and 4G7, patent no. PCT/CA2009/000070, “Monoclonal antibodies for Ebola and Marburg viruses,” and J.E. and J.D.T. hold a patent on the antiviral DEF201, U.S. patent no. 8,309,531, “Administration of Interferon for prophylaxis against or treatment of pathogenic infection.”

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Wilson JA, Bosio CM, Hart MK. 2001. Ebola virus: the search for vaccines and treatments. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58:1826–1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Falzarano D, Geisbert TW, Feldmann H. 2011. Progress in filovirus vaccine development: evaluating the potential for clinical use. Expert Rev. Vaccines 10:63–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barrette RW, Metwally SA, Rowland JM, Xu L, Zaki SR, Nichol ST, Rollin PE, Towner JS, Shieh WJ, Batten B, Sealy TK, Carrillo C, Moran KE, Bracht AJ, Mayr GA, Sirios-Cruz M, Catbagan DP, Lautner EA, Ksiazek TG, White WR, McIntosh MT. 2009. Discovery of swine as a host for the Reston Ebolavirus. Science 325:204–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nidom CA, Nakayama E, Nidom RV, Alamudi MY, Daulay S, Dharmayanti IN, Dachlan YP, Amin M, Igarashi M, Miyamoto H, Yoshida R, Takada A. 2012. Serological evidence of Ebola virus infection in Indonesian orangutans. PLoS One 7:e40740. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yuan J, Zhang Y, Li J, Wang LF, Shi Z. 2012. Serological evidence of Ebolavirus infection in bats, China. Virol. J. 9:236. 10.1186/1743-422X-9-236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Negredo A, Palacios G, Vazquez-Moron S, Gonzalez F, Dopazo H, Molero F, Juste J, Quetglas J, Savji N, de la Cruz Martinez M, Herrera JE, Pizarro M, Hutchison SK, Echevarria JE, Lipkin WI, Tenorio A. 2011. Discovery of an Ebolavirus-like filovirus in europe. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002304. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weingartl HM, Embury-Hyatt C, Nfon C, Leung A, Smith G, Kobinger G. 2012. Transmission of Ebola virus from pigs to non-human primates. Sci. Rep. 2:811. 10.1038/srep00811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoenen T, Groseth A, Feldmann H. 2012. Current Ebola vaccines. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 12:859–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Qiu X, Alimonti JB, Melito PL, Fernando L, Stroher U, Jones SM. 2011. Characterization of Zaire Ebolavirus glycoprotein-specific monoclonal antibodies. Clin. Immunol. 141:218–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qiu X, Audet J, Wong G, Pillet S, Bello A, Cabral T, Strong JE, Plummer F, Corbett CR, Alimonti JB, Kobinger GP. 2012. Successful treatment of Ebola virus-infected cynomolgus macaques with monoclonal antibodies. Sci. Transl. Med. 4:138ra181. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qiu X, Fernando L, Melito PL, Audet J, Feldmann H, Kobinger G, Alimonti JB, Jones SM. 2012. Ebola GP-specific monoclonal antibodies protect mice and guinea pigs from lethal Ebola virus infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6:e1575. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Olinger GG, Jr, Pettitt J, Kim D, Working C, Bohorov O, Bratcher B, Hiatt E, Hume SD, Johnson AK, Morton J, Pauly M, Whaley KJ, Lear CM, Biggins JE, Scully C, Hensley L, Zeitlin L. 2012. Delayed treatment of Ebola virus infection with plant-derived monoclonal antibodies provides protection in rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:18030–18035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu JQ, Barabe ND, Huang YM, Rayner GA, Christopher ME, Schmaltz FL. 2007. Pre- and post-exposure protection against Western equine encephalitis virus after single inoculation with adenovirus vector expressing interferon alpha. Virology 369:206–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gowen BB, Ennis J, Russell A, Sefing EJ, Wong MH, Turner J. 2011. Use of recombinant adenovirus vectored consensus IFN-alpha to avert severe arenavirus infection. PLoS One 6:e26072. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gowen BB, Ennis J, Sefing EJ, Wong MH, Jung KH, Turner JD. 2012. Extended protection against phlebovirus infection conferred by recombinant adenovirus expressing consensus interferon (DEF201). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4168–4174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Julander JG, Ennis J, Turner J, Morrey JD. 2011. Treatment of yellow fever virus with an adenovirus-vectored interferon, DEF201, in a hamster model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2067–2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kumaki Y, Ennis J, Rahbar R, Turner JD, Wandersee MK, Smith AJ, Bailey KW, Vest ZG, Madsen JR, Li JK, Barnard DL. 2011. Single-dose intranasal administration with mDEF201 (adenovirus vectored mouse interferon-alpha) confers protection from mortality in a lethal SARS-CoV BALB/c mouse model. Antiviral Res. 89:75–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smee DF, Wong MH, Russell A, Ennis J, Turner JD. 2011. Therapy and long-term prophylaxis of vaccinia virus respiratory infections in mice with an adenovirus-vectored interferon alpha (mDEF201). PLoS One 6:e26330. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Richardson JS, Wong G, Pillet S, Schindle S, Ennis J, Turner J, Strong JE, Kobinger GP. 2011. Evaluation of different strategies for post-exposure treatment of Ebola virus infection in rodents. J. Bioterror Biodef. S1:007. 10.4172/2157-2526.S1-007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Connolly BM, Steele KE, Davis KJ, Geisbert TW, Kell WM, Jaax NK, Jahrling PB. 1999. Pathogenesis of experimental Ebola virus infection in guinea pigs. J. Infect. Dis. 179(Suppl 1):S203–S217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gear JH. 1989. Clinical aspects of African viral hemorrhagic fevers. Rev. Infect. Dis. 11(Suppl 4):S777–S782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Jahrling PB, Johnson E, Dalgard DW, Peters CJ. 1992. Enzyme immunosorbent assay for Ebola virus antigens in tissues of infected primates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:947–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leroy EM, Baize S, Lu CY, McCormick JB, Georges AJ, Georges-Courbot MC, Lansoud-Soukate J, Fisher-Hoch SP. 2000. Diagnosis of Ebola haemorrhagic fever by RT-PCR in an epidemic setting. J. Med. Virol. 60:463–467 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]