Abstract

Enterovirus 71 (EV71) is an important emerging human pathogen with a global distribution and presents a disease pattern resembling poliomyelitis with seasonal epidemics that include cases of severe neurological complications, such as acute flaccid paralysis. EV71 is a member of the Picornaviridae family, which consists of icosahedral, nonenveloped, single-stranded RNA viruses. Here we report structures derived from X-ray crystallography and cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) for the 1095 strain of EV71, including a putative precursor in virus assembly, the procapsid, and the mature virus capsid. The cryo-EM map of the procapsid provides new structural information on portions of the capsid proteins VP0 and VP1 that are disordered in the higher-resolution crystal structures. Our structures solved from virus particles in solution are largely in agreement with those from prior X-ray crystallographic studies; however, we observe small but significant structural differences for the 1095 procapsid compared to a structure solved in a previous study (X. Wang, W. Peng, J. Ren, Z. Hu, J. Xu, Z. Lou, X. Li, W. Yin, X. Shen, C. Porta, T. S. Walter, G. Evans, D. Axford, R. Owen, D. J. Rowlands, J. Wang, D. I. Stuart, E. E. Fry, and Z. Rao, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19:424–429, 2012) for a different strain of EV71. For both EV71 strains, the procapsid is significantly larger in diameter than the mature capsid, unlike in any other picornavirus. Nonetheless, our results demonstrate that picornavirus capsid expansion is possible without RNA encapsidation and that picornavirus assembly may involve an inward radial collapse of the procapsid to yield the native virion.

INTRODUCTION

Enteroviruses are the causative agents of disease in both developed and developing countries. Enterovirus 71 (EV71) was first isolated in California from patients with central nervous system diseases (1) and is responsible for hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), which is a common viral illness of infants and children that causes fever, sore throat, blisters, and skin rash. There is no specific therapy for HFMD, and most patients recover without special treatment. However, EV71 infection may lead to severe neurologic diseases, including meningitis, poliomyelitis-like disease, and fatal cases of encephalitis (3). Since first reported, EV71 has been implicated in an increasing number of outbreaks throughout the world and is now classified as an emerging infectious disease with pandemic potential (4, 5). A thorough structural and mechanistic understanding of the virus and its interactions with host cells will support efforts to develop antiviral therapies, and we focus here on establishing a structural basis for this knowledge.

EV71 is classified as a human enterovirus A (HEV-A) (6), one of four species, A to D, within the genus Enterovirus of the Picornaviridae family. EV71 has been divided into three genogroups, designated A, B, and C, according to nucleotide sequence analysis between different isolates (7). The mature virus has one copy of a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome packaged inside a nonenveloped icosahedral capsid with T=1 (quasi-T=3) symmetry (8, 9). The mature capsid is built of 60 structural subunits or protomers, which are comprised of four structural proteins, VP1 to VP4 (VP1-4). Several key residues that map to the 5-fold symmetry vertex, VP1 98 and 145, have been linked to positive selection, virulence, and receptor binding (4, 10–12).

Five host receptors have been reported for EV71: P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) (13), the scavenger receptor B2 (SCARB2) (14), sialylated glycans (15, 16), annexin II (17), and heparin sulfate (18). Currently, no receptor footprint on the virus capsid is known, but there is evidence that SCARB2 binds into the depression surrounding each 5-fold axis, known as the “canyon” (19). The model for infection of many picornaviruses begins with a specific capsid-receptor interaction that triggers a conformational change in the capsid to form the 135S, or “A,” particle. These changes are necessary for the release of the viral genome into the host cell cytoplasm. The viral RNA is translated into a single polyprotein that is subsequently cleaved to generate the initial structural proteins (VP0, VP1, and VP3). These viral proteins associate into pentamers that self-assemble into empty protein shells, sometimes referred to as procapsids due to the lack of RNA and the presence of uncleaved VP0 (20). Two pathways to the provirion are proposed: (i) packaging of a progeny genome into the preformed procapsid (21–23) or (ii) incorporation of the RNA genome during the self-assembly of 12 pentamers. Either way, the association of RNA with capsid leads to the cleavage of VP0 into VP2 and VP4 (24, 25) by an autocatalytic mechanism (26, 27), yielding the mature virus.

Recently, crystal structures have been reported for the EV71 Fuyang (9) and MY104 (8) strains, representing two different genogroups, C4 and B3, respectively. Here we present structures of EV71 from the 1095 strain that belongs to genogroup C2 (28), including cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) reconstructions of the procapsid and mature virion at resolutions of 8.8 Å and 9.5 Å, respectively, and a 3.9-Å crystal structure of the procapsid. The cryo-EM structures solved from particles in solution agree with the crystal structures. In addition, our cryo-EM reconstruction of the EV71 procapsid shows additional density corresponding to the N terminus of VP1 and the VP4 region of VP0, both of which are disordered in the crystal structure. A detailed comparison between the Fuyang and 1095 crystal structures shows differences at the 5-fold vertex, specifically in residues that determine virulence, antigenicity, and receptor use (10, 11, 18) (H. Lee, J. O. Cifuente, R. E. Ashley, J. F. Conway, A. M. Makhov, Y. Tano, H. Shimizu, Y. Nishimura, and S. Hafenstein, unpublished data; and Y. Nishimura, H. Lee, S. Hafenstein, C. Kataoka, T. Wakita, J. M. Bergelson, and H. Shimizu, unpublished data). Finally, we discuss our new structures in the context of uncoating and genome release (9, 29) and their impact on the current models for capsid assembly and the final stages of EV71 morphogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus propagation and purification.

The EV71 strain 1095 (inoculum kindly provided by Yorihiro Nishimura) that binds receptors PSGL-1 and SCARB2 (13, 14) was propagated by infecting HeLa cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 in culture with Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2.5% fetal bovine serum. After 24 h, cells and media were collected and processed by three cycles of freezing and thawing. The lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm in a Sorvall centrifuge using an SLA1500 rotor at 4°C for 15 min to remove cellular debris. Supernatant was collected and precipitated by incubation overnight with polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 and NaCl to final concentrations of 8% and 0.5 M, respectively. The precipitate was collected by Sorvall centrifugation in an SLA1500 rotor at 4°C at 13,000 rpm for 45 min. The pellets were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, and 50 mM MgCl buffer and incubated with DNase (0.05 mg/ml) while being gently rocked for 30 min at room temperature. Initially, trypsin was added (0.5 mg/ml) and incubated for 10 min at 37°C; however, this step was omitted in later purifications, resulting in more-stable particles. EDTA at 0.1 M, pH 8.0, and n-lauroylsarcosine were added, each to 10% of the total volume. If necessary, pH was adjusted with ammonium hydroxide. A slow-speed centrifugation was used to clear supernatant before pelleting by ultracentrifugation through a 30% sucrose buffer cushion using a 50.2ti rotor at 48,000 rpm at 4°C for 90 min. Pellets were collected, resuspended in the purification buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, and 50 mM MgCl), and loaded onto 10 to 35% tartrate step gradients for ultracentrifugation at 36,000 rpm for 2 h at 4°C in an SW41 rotor. Two distinct bands formed in the gradient, were collected independently by side puncture, and were washed three times with purification buffer in a spin filter (Millipore) to change the buffer. The samples were characterized by SDS-PAGE and electron microscopy. The upper band corresponded to procapsids devoid of genomic material and containing uncleaved VP0 proteins, whereas the lower band contained particles consisting of mature viral capsid proteins with a packaged genome.

Crystal structure determination of the procapsid.

EV71 procapsid crystals were obtained using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at room temperature. Drops consisted of 5 μl of purified EV71 procapsid at a concentration of 10 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 50 mM MgCl2 mixed with 5 μl of well solution. Crystals were obtained from 100 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.6 M NaCl, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.4 M PEG 8000, and 0.4% glycerol. Crystals were frozen using 12% PEG 400 and 19% glycerol as cryoprotectants and transported to the F1 beamline at CHESS (Cornell, Ithaca, NY). Data were collected with an oscillation of 0.2° on an ADSC Quantum 315 detector at a distance of 450 cm.

Data were indexed, processed, scaled, and reduced using the HKL-2000 package (30). The crystal was determined to be in the cubic crystal system and space group P4(2)32 with unit cell parameters of a=b=c = 350.248 Å. The data collection and processing statistics are provided in Table 1. Each crystallographic asymmetric unit contained 5 protomers. The diffraction data were phased using the molecular replacement method in the AMoRe program (31) implemented in the Phenix software suite (32).

Table 1.

X-ray crystallography statistics for scaling and refinementa

| Parameter | Value or description |

|---|---|

| Space group | P4(2)32 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | |

| a=b=c | 350.25 |

| α=β=γ | 90° |

| Resolution limits (high-resolution bin) (Å) | 50.0–3.90 (3.93–3.90) |

| No. of unique reflections | 66,880 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100) |

| Rmerge | 18.9 (73.8) |

| Avg redundancy | 7.1 (6.2) |

| 〈I〉/〈sI〉 | 10.3 (2.4) |

| Rcryst | 26.8 (35.5) |

| Rfree | 28.4 (38.0) |

| Avg B factor | 127 |

| % of Ramachandran plot outliers | 0.5 |

| % of most-favored regions in Ramachandran plot | 70.5 |

| RMSD for bonds | 0.01 |

| RMSD for angles | 1.46 |

Values in parentheses indicate the specific values in the particular highest-resolution shell (3.93–3.90). R = {Σ|F(obs) − F(calc)|}/Σ F(obs). 〈I〉/〈sI〉, average signal/noise ratio after averaging symmetry-related observations.

For phasing purposes, a three-dimensional structure of the EV71 protomer was calculated through the UCSF Chimera interface (33) using MODELLER (34). All four structural proteins, VP1-4, were modeled independently as follows: the protein sequence was acquired from the UniProt database (accession number E5RPG1) for the EV71 strain 1095-LPS1. Using the function Match-Align from Chimera (35), the known crystal structures of nine other picornaviruses from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database were superimposed using atomic coordinates as a reference and aligned using the global alignment algorithm (Needleman-Wunsch) with the BLOSUM 62 matrix. To prevent bias, structures representing as many different enterovirus groups as possible were used: poliovirus 1 (1ASJ) (36), bovine enterovirus 1 (1BEV) (37), coxsackievirus B3 (1COV) (38), coxsackievirus A9 (1D4M) (39), echovirus 1 (1EV1) (40), swine vesicular disease virus (1MQT) (41), coxsackievirus A21 (1Z7S) (42), echovirus 7 (2X5I) (43), and human rhinovirus 14 (4RHV) (44). In addition, individual EV71-1095 structural proteins were aligned to the corresponding picornavirus proteins using the same algorithm. Crystal structures for the individual proteins were used as a template for modeling the aligned sequence of EV71-1095 with MODELLER. Once the independent protein models were calculated, VP1-4 models were combined in a single PDB file using MOLEMAN (45).

This homology model of the protomer was fit into the cryo-EM procapsid reconstruction to generate a pentamer model used as a search model in molecular replacement. The orientation of the pentamer in the crystal unit cell was determined by a cross-rotation search, and its position was determined by a translation search. The pentamer model was positioned accordingly into the crystal unit cell to calculate a set of initial phases. These phases were improved by refinement using the Crystallography and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) System (CNS) package (46). CNS programs for simulated annealing, energy minimization, atomic position, and temperature factor refinement were used with the application of strict noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) operators. After each refinement cycle, a single cycle of electron density Fourier map (2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc, where Fo indicates the observed structure factors and Fc indicates the structure factors calculated from the model) averaging was carried out in CNS, with strict NCS operators, using the experimentally measured amplitudes and the improved phases. The program Coot (47) was used for model building into averaged electron density maps between cycles of the refinement and averaging procedures. During the process of refinement, an X-ray crystal structure was published for an EV71 empty particle of the Fuyang strain, which differed in the identity of seven amino acid residues (PDB accession number 3VBU) (35). Our working model (Rfree of 32.6) superimposed onto 3VBU with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 2.4 Å, with differences mapping almost exclusively to loop tips and termini. Using the newly available 3VBU structure, altered to the EV71-1095 identity at the sites of the seven amino acid differences, two more rounds of refinement were completed, interspersed with manual building, resulting in the final model with an Rfree of 28.4% and an overall RMSD of 1.0 Å compared to 3VBU.

Cryo-EM reconstruction.

A total of 3 μl of purified virus was blotted onto Quantifoil grids (Quantifoil Micro Tools GmbH, Jena, Germany) and plunge-frozen into a liquid ethane/propane mixture (48) by a Vitrobot (FEI, Hillsboro, Oregon). Data were collected under low-dose conditions on Kodak SO-163 film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) in an FEI TF-20 electron microscope operating at 200,000 V and a nominal magnification of 50,000× and equipped with a Gatan 626 cryoholder (Gatan, Pleasonton, CA). Films were scanned using a Nikon Super Coolscan 9000 (Nikon, Melville, NY), giving a final pixel size of 1.27 Å/pixel for both the EV71-1095 procapsid and the mature virus particle. The program suites AUTO3DEM (49) and EMAN2 (50) were used for reconstruction and image processing. Semiautomatic particle selection was performed using e2boxer.py to obtain the particle coordinates, followed by particle boxing, linearization, normalization, and apodization of the images using Robem (49). Defocus and astigmatism values to perform contrast transfer function (CTF) correction were assessed using Robem for the extracted particles (Table 2). The icosahedrally averaged reconstructions were initiated using a random model generated with setup_rmc (51) and reached better than the 10-Å resolution estimated at a Fourier shell correlation (FSC) of 0.5. For the last step of refinement, the final maps were CTF corrected and sharpened with an inverse temperature factor of 1/300 Å2.

Table 2.

Cryo-EM data

| Particle type | No. of films | Defocus range (μ) | Total no. of particles | No. of particles used | Resolution (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procapsid | 20 | 0.79–3.91 | 12,579 | 8,805 | 8.8 |

| Virion | 24 | 2.36–3.94 | 8,812 | 6,168 | 9.5 |

Assessment of cryo-EM map handedness and pixel size.

Using the final 9.5-Å-resolution EV71 mature particle reconstruction, a density map representing the stereo-isomer was generated by mirroring the complex map across the xy plane to “flip” the hand. A map calculated from the crystal structure of EV71, 3VBS (9), was fitted as a rigid body separately into each stereo-isomer map rendered at a density threshold of 1σ (35, 52). Correct handedness was assessed by the quality of fit, by measuring correlation coefficients (cc) using the UCSF Chimera protocol “Fit in Map” (35); for procapsid, the cc was 0.959 (as opposed to 0.935 for the opposite hand), and for native virus, the cc was 0.973 (versus 0.956). In addition, the highest cc fit also allowed calibration of the spatial scale of the cryo-EM reconstruction at 1.25 Å/pixel. A similar procedure was followed for the structure of the final 8.8-Å-resolution EV71 procapsid using the crystal structure of the EV71-1095 strain reported here.

Difference map and volume assessment.

A simulated cryo-EM map was also made from our EV71-1095 procapsid crystal structure using pdb2vol and limiting the resolution to 9.0 Å (53). A difference map was made by subtracting the simulated map of the procapsid from the cryo-EM map using Situs, which applies zero padding to scale the lower-density map (54). The crystal structure of the mature virus (3VBS) (9) was superimposed on the fitted procapsid structure to provide the approximate position for the disordered sections of the procapsid, which are ordered in the mature capsid. The N-terminal 72 residues of VP1 and all of VP4 were used to make a density map that was subsequently surface rendered and measured to compare the volume to that of the difference density map, using Chimera to report the total surface area and enclosed volume (35).

PDB accession numbers.

Newly obtained information was deposited in PDB under the following accession numbers: EMD5557 for the cryo-EM reconstruction of the EV71-1095 procapsid, EMD5558 for the reconstruction of the EV71-1095 native virus, and 4GMP for the crystal structure of the EV71-1095 procapsid.

RESULTS

Purification of two particle types.

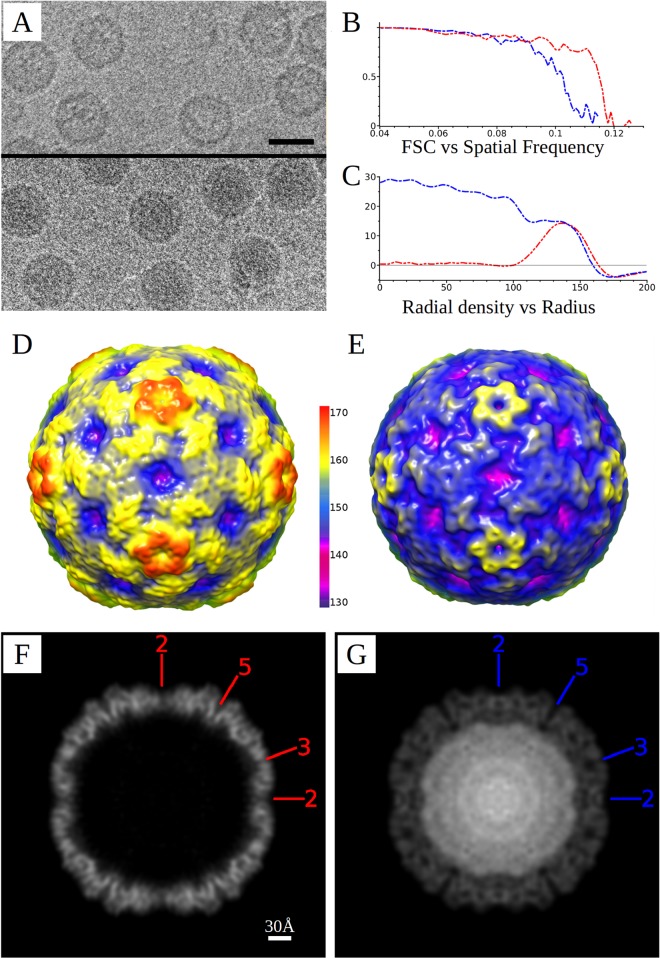

Two distinct bands formed in the final gradient purification of EV71-1095 and were characterized by SDS-PAGE (data not shown) and electron microscopy (Fig. 1A). As seen previously (55, 56), the upper band contained empty, ∼30-nm-diameter spherical particles comprised of intact VP0, VP1, and VP3. These empty particles are characteristic of procapsid (21, 57), a naturally occurring type of empty particle that forms during virus assembly and which contains uncleaved VP0, the precursor of VP2 and VP4. The lower band was comprised of particles with homogeneously dark centers due to the presence of the genome (Fig. 1A) which were consistent with mature viral capsids since they contained all four structural proteins, VP1-4.

Fig 1.

Cryo-EM reconstructions of EV71-9105 procapsid and capsid. (A) Representative areas of cryomicrographs used for the reconstructions with procapsid (top) and mature virion (bottom). Bar = 300 Å. (B) Fourier shell correlation versus spatial frequency. Resolution of the reconstructions is assessed where the FSC curve crosses below a correlation value of 0.5. (C) Radial density profiles revealing that the radius of the procapsid is greater than that of the virion capsid. (D and E) Surface renditions colored by radius of the procapsid and mature capsid density maps, respectively, illustrate the differences in size and angularity between the procapsid and capsid forms. The regions at the 5-fold vertices are distinctly raised in the procapsid by ∼11 Å compared to the mature capsid. (F and G) Corresponding central sections from the cryo-EM maps of the procapsid and the virion, respectively, show the arrangement of the capsid density without and with a packaged RNA genome and before and after cleavage of VP0. Locations of the 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes of symmetry are indicated.

Cryo-EM reconstruction.

The three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions achieved resolutions of 8.8 Å for the procapsid and 9.5 Å for the mature virus, estimated at an FSC of 0.5 (Table 2; Fig. 1). The electron density for the maps clearly indicates that the procapsid consists of an empty protein shell, whereas the mature virus contains density corresponding to a filled genomic core (Fig. 1). Compared to other enteroviruses, the EV71 mature virus has a smoother, nearly featureless exterior, due to shorter loops that decorate the external surface. The overall shape and diameter of the EV71 procapsid are different from those of the virus, as the procapsid is larger and more angular, with protruding 5-fold plateaus. In contrast, the virus appears as a smaller, rounder, and smoother particle, which likely explains the lower resolution achieved for it in our reconstruction.

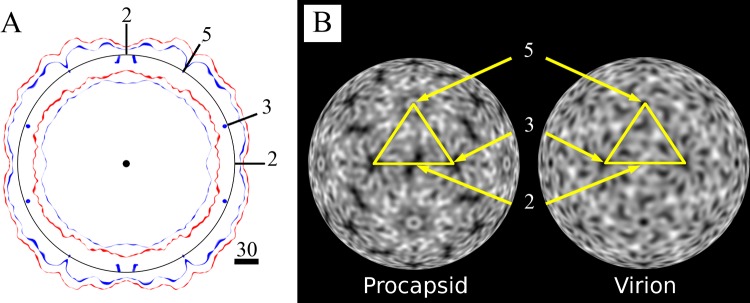

A superimposition of the central sections of the procapsid and capsid maps shows the radial difference at external and internal protein shell surfaces (Fig. 2). The procapsid is larger than the capsid, with the greatest external radial difference of 11 Å observed at the 5-fold axis and smaller differences seen at the 2-fold and 3-fold axes. Conversely, the internal radial surface differences are most significant near the 2-fold axis of symmetry. Differences in the distribution of the structural proteins are also reflected in the capsid shells, with the procapsid walls being thinner at the 2-fold axis and thicker at the 5-fold axis whereas the mature capsid has an evenly packed protein distribution and thickness throughout. The icosahedral radial projections illustrate the specific differences in protein packing in the procapsid and capsid (Fig. 2B). At a spherical shell radius value of 135 Å, the density is packed tighter and is more evenly distributed in the mature capsid. In addition, there is a clear rotation of the density around the 3-fold axis, corresponding to the external changes in the 3-fold plateau (Fig. 2B).

Fig 2.

Central surface projections and radial density projections. (A) Radial plot of a central section in the standard orientation for the capsid surfaces, displayed centered to a circle with an r of 135 Å and labeled positions for 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes of symmetry that cross the section. Red surfaces for the procapsid are rendered at 1 σ. For the virion (blue), the external surface is rendered at 1 σ and the inner surface is depicted at 2.35 σ, which is the level at which the RNA core can be distinguished from the protein capsid shell. The figure shows the rearrangement of both capsid surfaces between procapsid and virion, with notable differences in the width of the capsid wall, which is more regular and has more-densely packed protein in the virion. (B) The radial density projection is a 2D representation of the distribution of density of a spherical shell of the map at a given radius, r, of 135 Å. Density is white, and black represents the absence of density. The asymmetric unit is marked by a yellow line, with the icosahedral axes indicated. Comparison of the densities at the same radii shows intricate rearrangement of the capsid structural proteins in the virion relative to the procapsid. Specifically, at the 3-fold axis, rearrangement introduces directionality and fills the virion capsid density; at the 2-fold axis of the procapsid, there is notably less density in the procapsid; differences around the 5-fold axis are also noted due to the rearrangement of the density from movement of the protomers in the virion compared to the procapsid.

Crystal structure of the procapsid.

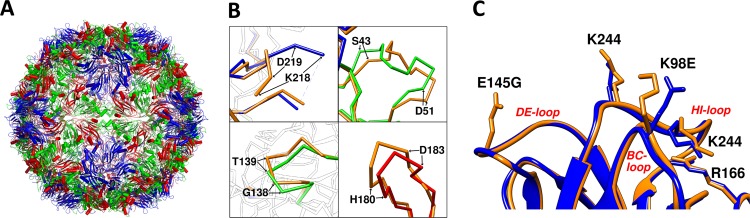

The crystal structure of the EV71-1095 procapsid (Fig. 3A) was solved to 3.9 Å and shows the canonical jelly roll β-barrel fold for each protein, VP0, VP1, and VP3, that is typical for picornaviruses. As seen in other procapsid structures (21, 57), some peptides on the internal surface of the particle are disordered, including the N termini of VP0 (first 81 residues) and VP1 (first 72 residues). The 81 disordered residues of VP0 correspond to all 69 residues of VP4 and the first 12 residues of VP2, the proteolytic products of VP0 found in mature capsids. The GH loop of VP1 (residues 211 to 217) is also disordered.

Fig 3.

(A) EV71-1095 procapsid crystal structure. Peptide chains are colored using the canonical picornavirus coloring scheme, with VP1 in blue, VP0 in green, and VP3 in red. The first 81 N-terminal residues of VP0 are disordered; hence, displayed here is the structure of VP0 residues 82 to 318, which correspond to VP2 residues 13 to 249, after cleavage. (B) Sites where EV71-1095 superimposed over the crystal structure of 3VBU (shown in gold) with an RMSD greater than 2 Å: VP1 residues 218 to 219 (GH loop, including disordered residues 211 to 217), VP0 residues 43 to 51 (η1-η2 loop or AB loop) and 138 to 139 (βE-α2 loop or EF loop), and VP3 residues 180 to 183 (βG-η3 loop or GH loop) (specific nomenclature of loops from Wang et al. [9]). (C) The zoomed view shows the EV71-1095 structure (blue) superimposed with the Fuyang structure, 3VBU (gold), to show the VP1 BC, DE, and HI loops of the 5-fold vertex. Side chains of the specific residues were depicted by sticks and labeled to show the slight but significant differences in residues known to affect virulence and PSGL-1 receptor binding.

Sequence and structural differences between EV71-1095 and the Fuyang strain at the 5-fold vertex.

The previously solved structure from Wang et al. (PDB accession number 3VBU) was of EV71 genotype C4, isolated from Fuyang, Anhui Province, China. Seven amino acids mapping to structural proteins were different between the Fuyang and 1095 strains (Fig. 3C; Table 3), four of which have been linked to the antigenicity of EV71 (58, 59). The crystal structure of the Fuyang strain procapsid superimposed onto our procapsid structure with an overall RMSD of 0.5 Å. The most significant differences in the C-α chains (more than 2 Å apart) were found in the GH loop of VP1, the AB and EF loops of VP0, and the GH loop of VP3 (Fig. 3B). There were no discernible differences between the two structures at the site of VP1-172, a determinant of SCARB2 receptor binding (19, 56).

Table 3.

Differences between EV71 Fuyang and 1095 strains that map to the structural proteins

| Structural protein | Amino acid differencea |

|---|---|

| VP1 | K98E |

| E145G | |

| M225C B | |

| VP0 | V126I A |

| T144S B | |

| VP3 | H29Y A |

| N93N |

We also found differences in the conformations of the 5-fold HI loops and the side chain positions of two lysine residues (Fig. 3C). Specifically, these differences affect the positively charged patches around the 5-fold axes, which have been implicated in the receptor binding and antigenicity of the virus (9, 18). Among the residues contributing to the positively charged patches (8), Lys 98 in the Fuyang strain has been replaced by Glu in the EV71-1095 strain. Thus, in the 1095 strain, Lys 242 and Lys 244 of the VP1 HI loop and Arg 166 of the VP1 DE loop contribute most to forming the positively charged patches around the 5-fold axes. The side chains of VP1 Lys 242 and Lys 244 are exposed to the surface, whereas the side chain of Arg 166 is buried in both procapsid strain structures. Additionally, EV71-1095 has a Gly at residue VP1 145 whereas the Fuyang strain has Glu at this position (Fig. 3D). This region at the 5-fold vertex represents a functional “hot spot,” since these residues have been implicated in receptor binding and have been shown to determine virus virulence and affect positive selection (4, 10–12, 18).

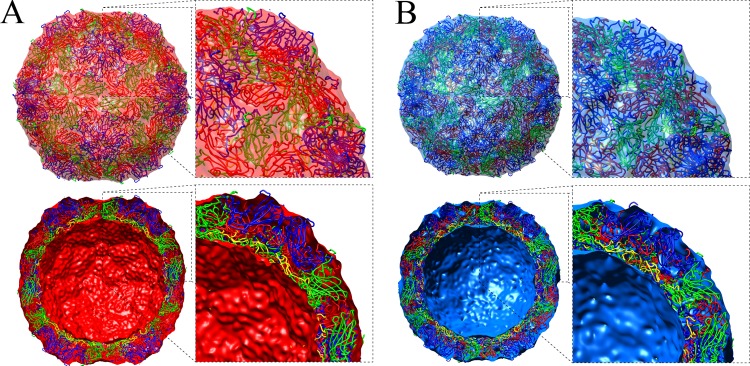

Evaluation of the cryo-EM density maps.

The cryo-EM 3D structures were evaluated by fitting the X-ray structures from our procapsid and the previously reported mature virus (PDB accession number 3VBS) (9) inside the cryo-EM density maps. The crystal structures agreed well with the cryo-EM structural features, and the fitting generated correlation coefficients of 0.96 and 0.98 for procapsid and capsid, respectively (35) (Fig. 4). However, due to disordered density in our procapsid crystal structure, a significant amount of cryo-EM density remained unfilled inside the procapsid. To investigate these densities, a simulated cryo-EM map was calculated from the crystal structure and subtracted from the cryo-EM map. To determine how well the difference density corresponded to the disordered regions of the crystal structure, the VP4 and VP1 structures that are ordered in the mature capsid (PDB accession number 3VBS) (9) were fitted into the difference map together by superimposing 3VBS onto the fitted crystal structure of the procapsid (9). This approximate positioning of VP4 and the N terminus of VP1 is reasonable, since the protomer moves as a rigid body between the expanded capsid and the collapsed virion (9). The combined structures of VP4 and VP1 satisfactorily filled the difference density (Fig. 5).

Fig 4.

Cryo-EM reconstructions of the procapsid (A) (red) and the virion (B) (blue), displayed at 1 σ, showing the fitting of crystal structures depicted as ribbons and colored according the canonical picornavirus coloring: VP1 in blue, VP0 in green, and VP3 in red for the procapsid and VP1 in blue, VP2 in green, VP3 in red, and VP4 in yellow for the virion. Full map and cutaway views are shown for each, with closeup views of the docked crystal structures adjacent. (A) Procapsid reconstruction fitted with the crystal structure of the empty particle (procapsid) 4GMP and VP4 from 3VBS (9). The front hemisphere of the reconstruction is displayed in transparent red, and the back hemisphere of the reconstruction shows the inner and outer surfaces. (B) Same views of the virion reconstruction (less RNA) fitted with the crystal structure 3VBS (9), with the reconstruction density displayed in transparent blue. The outer surface was rendered at 1 σ and the inner surface was rendered at 2.35 σ, as described in Fig. 2.

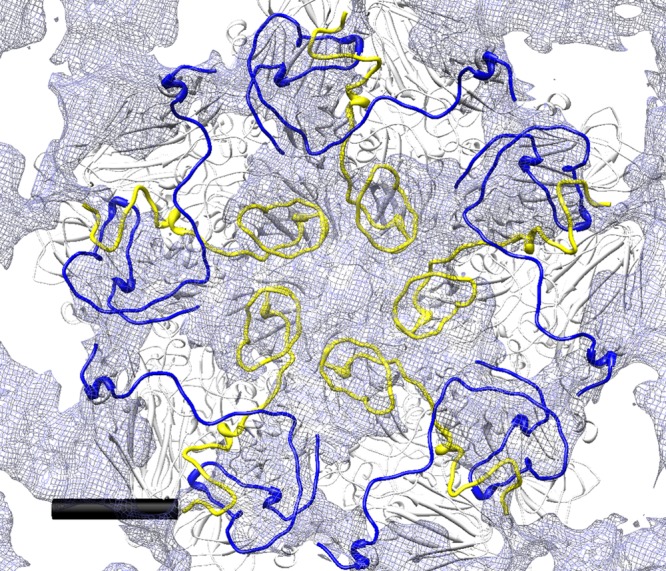

Fig 5.

Detail of the difference map in which the density corresponding to an 8-Å map simulated from the EV71-1095 procapsid X-ray crystal structure was subtracted from the cryo-EM map of the procapsid, resulting in an internal 5-fold plateau of density. The EV71-1095 procapsid structure was fitted with additional VP1 and VP4 portions of mature virus (3VBS) spliced in to provide the structure of those parts that are disordered in the procapsid crystal structure. The first 81 N-terminal residues of VP0 disordered in the procapsid correspond to all of VP4 (yellow ribbon) and five residues of VP2 (data not shown). The N-terminal 72 residues of VP1, which are also disordered in the crystal structure, are shown with a blue ribbon. The view is centered on a 5-fold axis of symmetry and shows the inner portion of the internal difference density map surface in translucent gray (radii, 0 to 140 Å). Noncolored portions of the 3VBS structure appear with a white ribbon. Scale bar = 30 Å.

To quantify this placement for the missing portions of the VP0 and VP1 proteins, we tested how well the volume of the difference map compares to a density volume that would encompass the structures of VP4 and VP1. The N-terminal 72 residues of VP1 and all of VP4 were used to make a model map. This map was surface rendered, and the total surface area and enclosed volume were measured (35). The volume of the VP1-VP4 model density is about 7% smaller than the volume represented by the difference map (Table 4).

Table 4.

Volume and area of the procapsid-procapsid difference map compared to the VP1-VP4 model map

Difference map = (cryo-EM) − (simulated cryo-EM map calculated from crystal structure).

Model map = N-terminal 72 residues of VP1 + all of VP4 (3VBS).

DISCUSSION

Strain-specific structures.

Several structures of EV71 capsids have now been solved, providing opportunities for understanding similarities in assembly and function as well as differences that affect virulence, antigenicity, and receptor use. Our crystal structure of the EV71 genogroup C2 strain 1095 procapsid and cryo-EM map of the mature particle joins crystal structures of a genogroup B3 capsid (8) and the procapsid and mature capsid of the C4 Fuyang strain (9). We observe that fitting the corresponding Fuyang strain crystal structures into our cryo-EM maps confirms the correspondence between particles in solution with those from the crystallized form (Fig. 5), at least to the lower resolution of the EM data. Further, this successful fitting of the Fuyang empty expanded particle into our procapsid map, together with our identification of the uncleaved VP0 to confirm the procapsid state, strongly indicates that the structures represent the same particle, i.e., the Fuyang empty expanded particle is the procapsid form.

The differences between the structures of EV71-1095 and the Fuyang strain are very minor but likely have consequences in virulence, antigenicity, and receptor use. Recent studies revealed that the basic residues at the 5-fold axes are responsible for binding heparin sulfate (18, 60), and we have found a strain-specific neutralizing epitope that maps to this patch of basic residues (Lee et al., unpublished). Changes in this patch, such as the charge difference observed between the two strains for residues occupying the VP1 98 position, may be expected to significantly alter the functional properties of the capsid surface. Also, the effect of the slight conformational differences of the side chains of two basic amino acids and the VP1 HI loop may be enhanced in the native virus since those two residues have significantly different conformations in mature virus compared to those in the procapsid (9). Consequently, it is reasonable to suspect that differences in PSGL-1 receptor interaction and antigenicity are related to the structure and character of the 5-fold loop region.

Peptide locations assigned by cryo-EM complete the transition of procapsid to capsid.

The incomplete visualization of capsid subunits in the procapsid crystal structures was addressed by examining cryo-EM density that was unoccupied by the subunit atomic models. In particular, the N terminus of VP0, which after proteolysis forms VP4, and the N terminus of VP1 were largely accounted for in the unoccupied cryo-EM density. The VP4 residues 14 to 31, observed to form a loose spiral in the X-ray model of the mature capsid (9), fit well into the cryo-EM density on the inside of the procapsid surrounding the 5-fold vertex, whereas the N terminus of VP1 fills unoccupied density around the icosahedral 3-fold axis. Some density directly on the 5-fold axis remains unfilled, although its high level of noise suggests less certainty in its occupancy and reliability. Nonetheless, the positions of these peptides support rigid body movement of an entire protomer as the conformational switch between expanded (procapsid) and nonexpanded (mature capsid) forms of EV71.

The EV71 VP4 subunit in the mature capsid occupies a different position relative to the rest of the protomer than is found in other picornaviruses, lying under the adjacent protomer instead of being directly located under its own biological protomer (9). Our cryo-EM procapsid structure is consistent with this observation, with the VP4 precursor—the N-terminal portion of VP0—occupying the same position within the procapsid as does VP4 in the mature capsid. This unique positioning of VP4 relative to the protomer has unknown consequences, but this may possibly be related to the expanded nature of the procapsid. The typical location of VP4 under the protomer is known for both poliovirus and FMDV, the only other picornaviruses for which a procapsid structure exists and for which the procapsid is the same dimension as the virus.

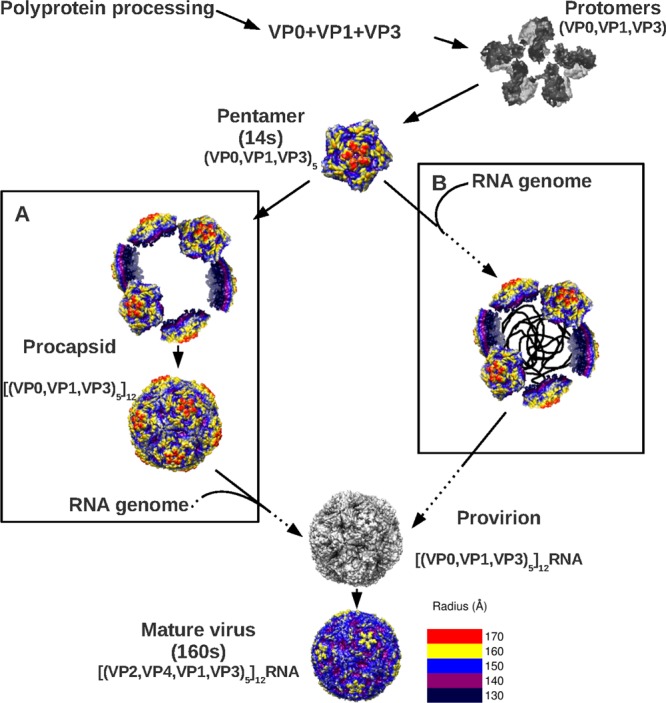

Assembly model.

An expanded procapsid, i.e., an empty, VP0-containing capsid, has not been observed in any other picornaviruses, although few structures have yet been obtained (21, 57). Two alternative pathways have been proposed for genome packaging (21–23) (Fig. 6) during virus morphogenesis. Twelve pentamers may assemble into a “true” procapsid into which the RNA is packaged by an unknown mechanism (25, 61), or alternatively, the genome may recruit pentamers, which subsequently condense into a capsid around the genome (62, 63). In either case, since cleavage of VP0 into VP4 and VP2 occurs after RNA packaging, an expanded particle containing RNA may exist as a provirion that would mature by proteolysis, collapsing upon the packaged genome to form virus. We note that such a maturation step has been established for another small icosahedral virus (64). Such a model also implies that the pentamer assembly intermediate exists in a conformational state similar to that of the procapsid rather than the conformation of the pentamer in the mature virion.

Fig 6.

Picornavirus assembly flowchart incorporating the new EV71 structural information and displaying the structural proteins, intermediates of assembly, and protein stoichiometry. The single RNA transcript is translated into a polypeptide that is proteolysed to produce the structural proteins VP0, VP1, and VP3. These proteins assemble into protomers, five of which self-assemble to form a pentamer. Pentamers (14S) assemble into the provirion either by procapsid self-assembly followed by progeny genome packaging (A) or by capsid condensation around a progeny genome (B). The latter model suggests that the empty procapsids are an off-pathway structure. The final step of maturation involves the cleavage of VP0 to generate VP2 and VP4, a step which is induced by the packaged RNA. In the flowchart, the observed and hypothetical paths are depicted by solid and dashed arrows, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH K22 A179271 and a 2011 C. Max Lang Junior Faculty Research Scholar Award to S.H.

We gratefully acknowledge the use of the Core Facility of the Penn State College of Medicine. X-ray crystallographic data sets were collected at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS), which is supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences under NSF award DMR-0936384, using the Macromolecular Diffraction at CHESS (MacCHESS) facility, which is supported by award GM-103485 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

J.O.C., H.L., and J.D.Y. performed research; M.S.C. and K.L.S. contributed processing support; J.D.Y. and M.S.C. collected crystal data; J.D.Y. processed crystal data; J.L.Y. contributed reagents/virus; R.E.A. performed microscopy; A.M.M. and J.F.C. collected cryo-EM data; J.O.C. processed and analyzed cryo-EM data; J.O.C., H.L., and S.H. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 May 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Schmidt NJ, Lennette EH, Ho HH. 1974. An apparently new enterovirus isolated from patients with disease of the central nervous system. J. Infect. Dis. 129:304–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reference deleted.

- 3. Solomon T, Lewthwaite P, Perera D, Cardosa MJ, McMinn P, Ooi MH. 2010. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10:778–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang SW, Hsu YW, Smith DJ, Kiang D, Tsai HP, Lin KH, Wang SM, Liu CC, Su IJ, Wang JR. 2009. Reemergence of enterovirus 71 in 2008 in Taiwan: dynamics of genetic and antigenic evolution from 1998 to 2008. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3653–3662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tyler KL. 2009. Emerging viral infections of the central nervous system: part 1. Arch. Neurol. 66:939–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Phuektes P, Chua BH, Sanders S, Bek EJ, Kok CC, McMinn PC. 2011. Mapping genetic determinants of the cell-culture growth phenotype of enterovirus 71. J. Gen. Virol. 92:1380–1390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iwai M, Masaki A, Hasegawa S, Obara M, Horimoto E, Nakamura K, Tanaka Y, Endo K, Tanaka K, Ueda J, Shiraki K, Kurata T, Takizawa T. 2009. Genetic changes of coxsackievirus A16 and enterovirus 71 isolated from hand, foot, and mouth disease patients in Toyama, Japan between 1981 and 2007. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 62:254–259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Plevka P, Perera R, Cardosa J, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2012. Crystal structure of human enterovirus 71. Science 336:1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang X, Peng W, Ren J, Hu Z, Xu J, Lou Z, Li X, Yin W, Shen X, Porta C, Walter TS, Evans G, Axford D, Owen R, Rowlands DJ, Wang J, Stuart DI, Fry EE, Rao Z. 2012. A sensor-adaptor mechanism for enterovirus uncoating from structures of EV71. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19:424–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chang SC, Li WC, Chen GW, Tsao KC, Huang CG, Huang YC, Chiu CH, Kuo CY, Tsai KN, Shih SR, Lin TY. 2012. Genetic characterization of enterovirus 71 isolated from patients with severe disease by comparative analysis of complete genomes. J. Med. Virol. 84:931–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li R, Zou Q, Chen L, Zhang H, Wang Y. 2011. Molecular analysis of virulent determinants of enterovirus 71. PLoS One 6:e26237. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tee KK, Lam TT, Chan YF, Bible JM, Kamarulzaman A, Tong CY, Takebe Y, Pybus OG. 2010. Evolutionary genetics of human enterovirus 71: origin, population dynamics, natural selection, and seasonal periodicity of the VP1 gene. J. Virol. 84:3339–3350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nishimura Y, Shimojima M, Tano Y, Miyamura T, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2009. Human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is a functional receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat. Med. 15:794–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yamayoshi S, Yamashita Y, Li J, Hanagata N, Minowa T, Takemura T, Koike S. 2009. Scavenger receptor B2 is a cellular receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat. Med. 15:798–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Su PY, Liu YT, Chang HY, Huang SW, Wang YF, Yu CK, Wang JR, Chang CF. 2012. Cell surface sialylation affects binding of enterovirus 71 to rhabdomyosarcoma and neuroblastoma cells. BMC Microbiol. 12:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang B, Chuang H, Yang KD. 2009. Sialylated glycans as receptor and inhibitor of enterovirus 71 infection to DLD-1 intestinal cells. Virol. J. 6:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang SL, Chou YT, Wu CN, Ho MS. 2011. Annexin II binds to capsid protein VP1 of enterovirus 71 and enhances viral infectivity. J. Virol. 85:11809–11820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tan CW, Poh CL, Sam IC, Chan YF. 2013. Enterovirus 71 uses cell surface heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan as an attachment receptor. J. Virol. 87:611–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen P, Song Z, Qi Y, Feng X, Xu N, Sun Y, Wu X, Yao X, Mao Q, Li X, Dong W, Wan X, Huang N, Shen X, Liang Z, Li W. 2012. Molecular determinants of enterovirus 71 viral entry: cleft around GLN-172 on VP1 protein interacts with variable region on scavenge receptor B 2. J. Biol. Chem. 287:6406–6420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li C, Wang JC, Taylor MW, Zlotnick A. 2012. In vitro assembly of an empty picornavirus capsid follows a dodecahedral path. J. Virol. 86:13062–13069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Basavappa R, Syed R, Flore O, Icenogle JP, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 1994. Role and mechanism of the maturation cleavage of VP0 in poliovirus assembly: structure of the empty capsid assembly intermediate at 2.9 A resolution. Protein Sci. 3:1651–1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fernandez-Tomas CB, Guttman N, Baltimore D. 1973. Morphogenesis of poliovirus 3. Formation of provirion in cell-free extracts. J. Virol. 12:1181–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yin FH. 1977. Involvement of viral procapsid in the RNA synthesis and maturation of poliovirus. Virology 82:299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arnold E, Luo M, Vriend G, Rossmann MG, Palmenberg AC, Parks GD, Nicklin MJ, Wimmer E. 1987. Implications of the picornavirus capsid structure for polyprotein processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84:21–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jacobson MF, Asso J, Baltimore D. 1970. Further evidence on the formation of poliovirus proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 49:657–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bishop NE, Anderson DA. 1993. RNA-dependent cleavage of VP0 capsid protein in provirions of hepatitis A virus. Virology 197:616–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Compton SR, Nelsen B, Kirkegaard K. 1990. Temperature-sensitive poliovirus mutant fails to cleave VP0 and accumulates provirions. J. Virol. 64:4067–4075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miyamura K, Nishimura Y, Abo M, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2011. Adaptive mutations in the genomes of enterovirus 71 strains following infection of mouse cells expressing human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. J. Gen. Virol. 92:287–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hogle JM. 2012. A 3D framework for understanding enterovirus 71. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19:367–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Otwinowski Z, Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Navaza J. 1994. AMoRe: an automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. A 50:157–163 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang Z, Lasker K, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Webb B, Huang CC, Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Meng EC, Sali A, Ferrin TE. 2012. UCSF Chimera, MODELLER, and IMP: an integrated modeling system. J. Struct. Biol. 179:269–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sali A, Blundell TL. 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234:779–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wien MW, Curry S, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 1997. Structural studies of poliovirus mutants that overcome receptor defects. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:666–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smyth M, Tate J, Hoey E, Lyons C, Martin S, Stuart D. 1995. Implications for viral uncoating from the structure of bovine enterovirus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:224–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Muckelbauer JK, Kremer M, Minor I, Diana G, Dutko FJ, Groarke J, Pevear DC, Rossmann MG. 1995. The structure of coxsackievirus B3 at 3.5 Å resolution. Structure 3:653–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hendry E, Hatanaka H, Fry E, Smyth M, Tate J, Stanway G, Santti J, Maaronen M, Hyypia T, Stuart D. 1999. The crystal structure of coxsackievirus A9: new insights into the uncoating mechanisms of enteroviruses. Structure 7:1527–1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Filman DJ, Wien MW, Cunningham JA, Bergelson JM, Hogle JM. 1998. Structure determination of echovirus 1. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54:1261–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Verdaguer N, Jimenez-Clavero MA, Fita I, Ley V. 2003. Structure of swine vesicular disease virus: mapping of changes occurring during adaptation of human coxsackie B5 virus to infect swine. J. Virol. 77:9780–9789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xiao C, Bator-Kelly CM, Rieder E, Chipman PR, Craig A, Kuhn RJ, Wimmer E, Rossmann MG. 2005. The crystal structure of coxsackievirus A21 and its interaction with ICAM-1. Structure 13:1019–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Plevka P, Hafenstein S, Harris KG, Cifuente JO, Zhang Y, Bowman VD, Chipman PR, Bator CM, Lin F, Medof ME, Rossmann MG. 2010. Interaction of decay-accelerating factor with echovirus 7. J. Virol. 84:12665–12674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Arnold E, Rossmann MG. 1988. The use of molecular-replacement phases for the refinement of the human rhinovirus 14 structure. Acta Crystallogr. A 44:270–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kleywegt GJ, Zou JY, Kjeldgaard M, Jones TA. 2001. Around O, p 353–356 In Rossmann MG, Arnold E. (ed), International tables for crystallography, vol F Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. 1998. Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54:905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tivol WF, Briegel A, Jensen GJ. 2008. An improved cryogen for plunge freezing. Microsc. Microanal. 14:375–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yan X, Sinkovits RS, Baker TS. 2007. AUTO3DEM—an automated and high throughput program for image reconstruction of icosahedral particles. J. Struct. Biol. 157:73–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tang G, Peng L, Baldwin PR, Mann DS, Jiang W, Rees I, Ludtke SJ. 2007. EMAN2: an extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 157:38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yan X, Dryden KA, Tang J, Baker TS. 2007. Ab initio random model method facilitates 3D reconstruction of icosahedral particles. J. Struct. Biol. 157:211–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Goddard TD, Huang CC, Ferrin TE. 2007. Visualizing density maps with UCSF Chimera. J. Struct. Biol. 157:281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wriggers W. 2010. Using Situs for the integration of multi-resolution structures. Biophys. Rev. 2:21–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chacon P, Wriggers W. 2002. Multi-resolution contour-based fitting of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Biol. 317:375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liu CC, Guo MS, Lin FH, Hsiao KN, Chang KH, Chou AH, Wang YC, Chen YC, Yang CS, Chong PC. 2011. Purification and characterization of enterovirus 71 viral particles produced from Vero cells grown in a serum-free microcarrier bioreactor system. PLoS One 6:e20005. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yamayoshi S, Ohka S, Fujii K, Koike S. 2013. Functional comparison of SCARB2 and PSGL1 as receptors for enterovirus 71. J. Virol. 87:3335–3347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Curry S, Fry E, Blakemore W, Abu-Ghazaleh R, Jackson T, King A, Lea S, Newman J, Stuart D. 1997. Dissecting the roles of VP0 cleavage and RNA packaging in picornavirus capsid stabilization: the structure of empty capsids of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 71:9743–9752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gao F, Wang YP, Mao QY, Yao X, Liu S, Li FX, Zhu FC, Yang JY, Liang ZL, Lu FM, Wang JZ. 2012. Enterovirus 71 viral capsid protein linear epitopes: identification and characterization. Virol. J. 9:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liu CC, Chou AH, Lien SP, Lin HY, Liu SJ, Chang JY, Guo MS, Chow YH, Yang WS, Chang KH, Sia C, Chong P. 2011. Identification and characterization of a cross-neutralization epitope of enterovirus 71. Vaccine 29:4362–4372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McLeish NJ, Williams CH, Kaloudas D, Roivainen MM, Stanway G. 2012. Symmetry-related clustering of positive charges is a common mechanism for heparan sulfate binding in enteroviruses. J. Virol. 86:11163–11170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jacobson MF, Baltimore D. 1968. Morphogenesis of poliovirus. I. Association of the viral RNA with coat protein. J. Mol. Biol. 33:369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ghendon Y, Yakobson E, Mikhejeva A. 1972. Study of some stages of poliovirus morphogenesis in MiO cells. J. Virol. 10:261–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Marongiu ME, Pani A, Corrias MV, Sau M, La Colla P. 1981. Poliovirus morphogenesis. I. Identification of 80S dissociable particles and evidence for the artifactual production of procapsids. J. Virol. 39:341–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hafenstein S, Fane BA. 2002. ΦX174 genome-capsid interactions influence the biophysical properties of the virion: evidence for a scaffolding-like function for the genome during the final stages of morphogenesis. J. Virol. 76:5350–5356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]