Abstract

Severe dengue (SD) is a life-threatening complication of dengue that includes vascular permeability syndrome (VPS) and respiratory distress. Secondary infections are considered a risk factor for developing SD, presumably through a mechanism called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). Despite extensive studies, the molecular bases of how ADE contributes to SD and VPS are largely unknown. This work compares the cytokine responses of differentiated U937 human monocytic cells infected directly with dengue virus (DENV) or in the presence of enhancing concentrations of a humanized monoclonal antibody recognizing protein E (ADE-DENV infection). Using a cytometric bead assay, ADE-DENV-infected cells were found to produce significantly higher levels of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-12p70, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), as well as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), than cells directly infected. The capacity of conditioned supernatants (conditioned medium [CM]) to disrupt tight junctions (TJs) in MDCK cell cultures was evaluated. Exposure of MDCK cell monolayers to CM collected from ADE-DENV-infected cells (ADE-CM) but not from cells infected directly led to a rapid loss of transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) and to delocalization and degradation of apical-junction complex proteins. Depletion of either TNF-α, IL-6, or IL-12p70 from CM from ADE-DENV-infected cells fully reverted the disrupting effect on TJs. Remarkably, mice injected intraperitoneally with ADE-CM showed increased vascular permeability in sera and lungs, as indicated by an Evans blue quantification assay. These results indicate that the cytokine response of U937-derived macrophages to ADE-DENV infection shows an increased capacity to disturb TJs, while results obtained with the mouse model suggest that such a response may be related to the vascular plasma leakage characteristic of SD.

INTRODUCTION

Dengue is the most prevalent human viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes. Each year, an estimated more than 50 million cases take place, associated with more than 25,000 fatalities, especially in children (1). Dengue is endemic in more than 100 countries, and nearly one-third of the world population lives in areas of risk, which are the tropical and subtropical regions of the planet. Due to the great disease burden associated with dengue, the World Health Organization considers dengue a major public health problem and has issued a mandate to develop strategies to prevent and treat this disease. Still, there is currently neither a licensed vaccine nor a specific treatment for dengue (1).

Dengue virus (DENV) belongs to the genus Flavivirus within the family Flaviviridae and shows 4 serotypes (DENV1 to DENV4). The mature virion is approximately 50 nm in diameter and is composed of three structural proteins: C, which forms the nucleocapsid, containing the viral genome, and M and E, which are inserted in the lipid membrane that surrounds the nucleocapsid. Protein E is exposed on the virion surface and is responsible for binding and entry of the virus into the cell, for the genetic variability that gives rise to the 4 serotypes, and for the induction of neutralizing antibodies (2, 3). The DENV genome consists of a single-stranded RNA of positive polarity of approximately 11 kb in size. It encodes 7 nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5), which, together with the 3 structural proteins, are all derived from the proteolytic processing of a single polyprotein (4). Replication of DENV occurs in close association with rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and is presumed to require the assistance of cellular proteins, both for replication/translation of the genome and for the correct folding of viral proteins (5, 6). Nucleocapsids acquire their envelope by budding into the RER. Immature virions travel from the Golgi apparatus to the cell surface in secretory vesicles, where the host protease furin cleaves the prM protein into M protein to generate mature virions, which are finally released at the cell surface (7).

DENV infection can develop into 2 different clinical forms: dengue fever (DF) and severe dengue (SD). DF symptoms range from a mild fever to a high-degree fever including headache, myalgia and arthralgia, rash, and retro-orbital pain. SD is a life-threatening clinical complication of DF, characterized by plasma leakage and extensive pleural effusion, severe hemorrhages, respiratory distress, and organ failure that affect both children and adults (1). Plasma leakage is the hallmark of SD. The increased vascular dysfunction observed in patients suffering from SD suggests important changes in epithelial and endothelial tissue integrity. However, since vascular leakage occurs without noticeable morphological damage of the endothelium or cell destruction, plasma leakage appears to be associated more with functional than with anatomical damage of the capillary endothelial cells (8). As the primary fluid barrier of the vasculature, the endothelium plays a central role in regulating fluid and cellular efflux from capillaries. This barrier function and the capacity to keep fluids inside the vessels of the endothelium depend on the integrity of tight junctions (TJs) (9). Thus, vascular permeability syndrome (VPS) is presumed to be a TJ endothelial pathological disease (8).

DENV infection confers lifelong immunity against the infecting serotype (1). However, a risk factor for SD is the suffering of secondary infections with a viral serotype different from that of the primary infection. It has been postulated that subneutralizing antibody concentrations, remnants of previous infection, facilitate viral infection of macrophages and other Fc receptor-bearing cells, promoting virus replication (10). This mechanism, known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of infection, leads to an increase in the number of infected cells and an increase in virus yield per cell (11–16). In addition, ADE of infection has been associated with a massive release of cytokines from infected macrophages, a phenomenon referred to as a “cytokine storm” (17, 18). This aberrant response has been deemed responsible for the increased cytokine plasma levels reported in patients with VPS occurring during primary or secondary infections (18–20). The association between ADE of infection and SD was originally supported by epidemiological data (10, 14). However, more recently, experimental evidence of the occurrence of ADE of infection in vivo has been obtained (12, 21).

Despite extensive studies, the molecular bases of how ADE may contribute to VPS are largely unknown. Studies making direct comparisons of the cytokine response between Fcγ receptor (FcγR)-bearing cells infected directly or in the presence of enhancing antibody concentrations are scarce (22–25). Furthermore, the relationship between ADE and VPS is based mainly on the temporal association between clinical signs and immunologic markers, but mechanistic association between the two phenomena is lacking (26). Thus, the aim of this work has been to compare the cytokine responses of differentiated U937 cells infected with DENV in the presence (ADE-DENV infection) or absence of enhancing antibodies and, since plasma leakage may be a consequence of a disrupted barrier function, to compare the capacities of the conditioned media (CM) to disrupt the apical-junction complex (AJC) in MDCK cell cultures. Finally, in an attempt to associate the cytokine response with plasma leakage, the capacity of the CM to induce permeability alterations in an in vivo mouse model was also evaluated. The results indicate that the cytokine response of U937-derived macrophages to ADE infection is not a “storm” but rather is a modulated response, with a proinflammatory profile, which nonetheless shows a great capacity to disturb AJCs in vitro. In turn, the results obtained with the mouse model suggest that such a response may actually be related to the VPS observed in patients with SD. Taken together, these results provide experimental evidence that mechanistically associates ADE of infection, cytokine response, and AJC destabilization with DENV plasma leakage syndrome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents.

Humanized monoclonal antibodies, here identified as monoclonal antibody (MAb) IgGWt (IgG 1A5 wild type [Wt]) and its mutated (Mut) form, MAb IgGMut (IgG 1A5 ΔD), were kindly donated by Ana Paula Goncalvez from the National Institutes of Health. These antibodies are directed to the E protein and are capable of neutralizing more than one DENV serotype (12). A deletion in the Fc region of MAb IgG 1A5 ΔD affects Fc receptor recognition and abrogates ADE-DENV infection (12).

Evans blue dye (EVD) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) at a concentration of 2 mg/ml by continuous mixing and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22-μm filter (Millipore, Carrigtwohill, Ireland).

The following primary antibodies were used: anti-E monoclonal antibody 4G2; anti-zonula occludens 2 (ZO-2) (catalog no. 71-1400; Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA), antioccludin (catalog no. 71-1500; Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA), anti-E-cadherin (catalog no. U3254; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), anti-phospho-myosin light chain 2 (Ser19) (ab2480; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and antiactin (kindly donated by Manuel Hernández, Department of Cellular Biology, CINVESTAV-IPN). For immunofluorescence assay, the following secondary antibodies were used: anti-rabbit IgG fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated (Invitrogen Eugene), anti-mouse IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (A-21202; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and anti-rabbit IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 594 (A-21442; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR). For Western blot (WB) assays, anti-mouse IgG (catalog no. 62-6420; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), anti-rabbit IgG (catalog no. A9169; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and anti-rat IgG (catalog no. 81-9520; Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were employed.

Cell cultures and viral strains.

The human myelomonocytic cell line U937 (ATCC CRL-1593.2) was grown in RPMI 1640 reduced serum medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with nonessential amino acids, 110 mg/liter sodium pyruvate, 4 mM l-glutamine, 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen), 5 U/ml penicillin, and 5 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. For all experiments, the U937 cells were differentiated to macrophages by the addition of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 160 nM, 48 h prior to infection. Cells were used unsorted, since PMA treatment resulted in the differentiation of more than 80% of U937 cells, as determined by amount of CD14+ cells by flow cytometry (fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS]) assay (16). Depending on the experimental needs, U937 cells were either grown in 24-well plates or as scale-up cultures in P-100 petri dishes. Epithelial Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were grown as previously described (27). MDCK cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA and plated on 1.12-cm2 polyester membrane Transwell clear inserts (0.4-μm pore size; Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. Propagation of the prototype DENV serotype 4 (DENV-4) H241 strain was done in BALB/c suckling mouse brains, and viral titers were determined by plaque assay in BHK-21 cells, as described previously (28).

ADE-DENV infection of U937-derived macrophages.

Virus/antibody complexes were preformed by mixing 5-fold dilutions of the stock antibodies (IgG 1A5Wt and IgG 1A5 ΔD at 5 μg/ml) with DENV-4 (multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 1) during 1 h at 37°C with gentle oscillation. Then, cells were incubated with virus alone or with virus/antibody complexes for 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After infection, cell cultures (∼5 × 105 cells per well) were washed with Hanks medium 3 times and incubated with maintenance medium. The number of infected cells was quantified 72 h postinfection by flow cytometry (10,000 events) using an antibody against the envelope protein (anti-E, 4G2) and an anti-mouse IgG FITC-conjugated antibody (Invitrogen) as described before (16).

ADE-DENV infection and innate response by U937-derived macrophages.

The cytokine response of infected U937 cells in the absence (DENV) or presence (ADE-DENV) of enhancing antibodies was measured using a BD cytometric bead array (CBA) with human soluble protein flex sets and human soluble protein master buffer kits including particles with discrete fluorescence intensities to detect soluble analytes (BD CBA flex set; BD Biosciences). The flex set included seven cytokines with detection limits (expressed in pg/ml) as follows: interleukin 8 (IL-8), 1.2; IL-1β, 2.3; tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), 0.7; IL-12p70, 0.6; IL-10, 0.13; and IL-6, 1.6. Briefly, cell CM obtained 48 h postinfection were simultaneously immunoprecipitated by using a captured-bead array coated with specific antibodies against each cytokine evaluated. Then, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated detection reagents were added, and quantification was carried out by flow cytometry assay. Data acquisition and analyses were done by using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer using BD CellQuestPro software (BD Biosciences). Supplied standards were used to construct standard curves for each cytokine (R2 > 0.9957) (BD CBA flex set; BD Biosciences). The resulting mean fluorescence intensity (MIF) allowed sample analysis and soluble protein quantification by using the FCAP Array software program, version 3.0 (BD Biosciences, California, USA). In addition, prostaglandin E2 levels were determined from U937 CM by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (prostaglandin E2 [PGE2] EIA kit; Enzolife Sciences), following the manufacturer's procedure. The concentration of PGE2 (pg/ml) from unknown samples was determined from a standard curve constructed using a PGE2 standard supplied by the manufacturer and utilizing a 4-parameter logistic curve fit (R2 = 0.9980). CM were stored at −70°C until further use.

Measurement of TER in MDCK monolayers.

MDCK cells were grown on 1.12-cm2 polyester membranes Transwell clear inserts (pore size, 0.4; Corning Inc., Corning, NY) and monitored continuously until stabilization of transepithelial electrical resistance (TER). At this moment, half (250 μl) of the MDCK culture medium from the apical side was removed and replaced with an equal volume of U937 CM collected 48 h postinfection and cultured under standard conditions. CM used for TER analysis were collected from U937 cells grown in petri dishes in order to obtain the larger volumes required by the Transwell system. TER was continuously measured during a 24-h period from each insert by using an automated cell monitoring system, cellZscope (nanoAnalytics GmbH, Munster, Germany). TER values were obtained by using CellzScope software, version 1.5.0, and expressed as normalized TER (%) per hours postexposure.

Subtraction of selected cytokines from conditioned medium.

CM was incubated along with bead-coupled antibodies against TNF-α, IL-12, IL-6, and IL-10 (provided by Bender Medsystems). After 1 h of incubation at 4°C in gentle oscillation, the beads were removed by low-speed centrifugation and the supernatants were recovered. MDCK monolayers grown in Transwell inserts (Corning, NY) were treated with the depleted CM for 24 h, and TER was measured as described above.

Immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis of apical-junction complex proteins.

For evaluating the distribution and expression of cell surface proteins involved in the formation of AJCs, immunofluorescence and WB analysis were carried out. For immunofluorescence staining, MDCK cells treated or not with CM were fixed after 24 h with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C and then permeabilized with PBS–Triton X-100 (0.5%) for 15 min at room temperature. Monolayers were then washed with PBS, blocked with 3.0% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS–Triton X-100 (0.25%) for 1 h, and incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-ZO-2 antibodies (dilution, 1:100) or mouse antioccludin monoclonal antibody (dilution, 1:100). As secondary antibodies, a donkey polyclonal antibody against mouse IgG (dilution, 1:100) coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 and a chicken polyclonal antibody against rabbit IgG (1:200) coupled to Alexa Fluor 594 were used. Finally, Transwell membranes were withdrawn from the inserts and mounted on microscope slides using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, USA) and viewed with a Leica sp2 LSC Lite confocal microscope. Captured images were processed using Leica software.

In addition, the expression of AJC proteins was evaluated by WB assay. Briefly, MDCK cultures previously treated with the different CM were washed twice in ice-cold PBS and lysed in 0.25 ml of a lysis buffer (62.5 nM Tris, 10% glycerol, and 2% SDS) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The protein concentration was measured using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Thirty micrograms of total lysate diluted in sample buffer (0.16 M beta-mercaptoethanol, 0.05 M Tris base, 1.6% SDS, 8% glycerol, and 0.2% bromophenol blue) was heated to 95°C for 3 min and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Gels were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) Immobilon membranes (catalog no. IPVH00010; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and then blocked in a solution of PBS and 20% dry milk powder for 1 h. Afterward, membranes were incubated with specific primary antibodies and appropriate species-specific secondary antibodies coupled to HRP. Signal intensity was detected by using the Immobilon Western chemiluminescent HRP substrate system (catalog no. WBKLS0100; Millipore, Billerica, MA). To evaluate the phosphorylation level of myosin light chain 2 (Ser19), protein extracts were obtained by lysing cultures in the presence of lysis buffer supplemented with 1 mM sodium orthovanadate and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), pH 7.6.

Transmission electron microscopy analysis of TJs.

MDCK cells grown in Transwell inserts previously treated or not with CM were first fixed with 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, and postfixed for 60 min with 1% (wt/vol) osmium tetroxide added with 0.05 mg/ml of the electron-dense dye ruthenium red in the same buffer. After dehydration with increasing concentrations of ethanol and propylene oxide, samples were embedded in Polybed epoxy resins and polymerized at 60°C for 24 h. Thin sections (60 nm) were obtained and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for examination in a Jeol JEM 1011 electron microscope.

Vascular permeability assay.

Six- to seven-week-old mice ranging from 18 to 20 g in weight (CD-1 mice, Crl:CD1 [ICR]; Charles River) were injected intraperitoneally with 2 doses (100 μl each) of CM collected 48 h postinfection, 24 h apart. Together with the second dose, mice were also injected intraperitoneally (4 ml/kg of body weight) with a 1% solution of Evans blue dye (EVD) (wt/vol in PBS), and the stain allowed to circulate for 24 h (29). Although plasma leakage is usually evaluated when EVD is injected intravenously, no statistical differences in the amount of EVD stain remaining in the blood of mice after 3 h of circulation time were observed when comparing intraperitoneal and intravenous administration routes (29). Thus, for this work, the intraperitoneal route was used. A total of 24 mice divided into six groups (4 mice per group) were used, corresponding to the following CM: mock, DENV (DENV-CM), IgGWt (1 μg/ml), IgGWt (0.04 μg/ml), and IgGMut (0.04 μg/ml), plus TNF-α (4 ng/ml), used as a positive control. After final anesthesia (ketamine [70 mg/kg] and xylazine [6 mg/kg]), blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture and immediately put into EDTA-containing tubes (Microtainer; BD, USA). Samples were diluted 1/2 in PBS for plasma extraction by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 8 min. The amount of EVD present in plasma was measured by using a spectrophotometer (ELx808 absorbance microplate reader; BioTek Instruments, Inc.) at 630 nm and quantified according to a standard curve (range, 400 to 3 ng/ml; R2 = 0.999). The amount of EVD in lungs was also evaluated in the same animals transcardially perfused free of blood with 50 ml of PBS followed by 20 ml of formalin solution (Sigma) for tissue fixation. Lung tissues were removed and preserved in formalin solution at 4°C until further analysis. Finally, the right lung was vacuum dried, weighed, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to EVD extraction using formamide (2 ml/g of tissue; Sigma) and incubation at 65°C overnight (30). After centrifugation (12,000 × g for 30 min), supernatants were collected and the amount of EVD extracted was determined by reading the absorbance at 630 nm. The EVD concentration was calculated against a standard curve (range, 12 to 0.09 ng/ml; R = 0.998) and expressed as the fold increase for lung tissue in relation to the effect observed with the mock CM. This study was conducted in accordance with the Official Mexican Standard Guidelines for Production, Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NOM-062-ZOO-1999) and was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (UPEAL) at CINVESTAV-IPN, Mexico.

Viability assay.

In order to identify whether CM have any effect on MDCK cell integrity, two cell viability assays were performed. Briefly, MDCK cells cultured in 96-well plates were treated or not with the different CM during 24 h. Cell viability was determined using a colorimetric method based on a tetrazolium compound (MTS) for adherent cells (CellTiter 96 Aqueous One solution cell proliferation; Promega, USA) and an LDH assay using the cell supernatants (cytotoxicity detection kit [lactate dehydrogenase {LDH}]; Roche Applied Science, USA), by following the manufacturer's recommendations. Viability in cells treated with CM from mock-infected cells was taken to be 100%.

Statistical analysis.

SigmaPlot 11 software was used for graphical representations and statistical data analyses. Values were presented as the arithmetic means ± error values. Analysis conditions were compared by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Humanized antibodies enhance DENV infection in U937-derived macrophages.

As described by Goncálvez et al. (12), a humanized monoclonal antibody (IgG 1A5) that recognizes the E protein mediates ADE-DENV infection in monocyte-derived cell lines and in vivo, but mutations introduced in its Fc structure (IgG 1A5 ΔD) abrogate this mechanism (12). Here, the percentage of infected U937-derived macrophages determined by FACS assay was enhanced up to ≈10% at the concentration of 0.04 μg/ml (24.35% ± 1.5%) using IgGWt, compared to results with direct infection (absence of antibodies; 14.65% ± 0.63%). Infection in the presence of the same concentration of the mutated form of the antibody (IgGMut) resulted in infectivity levels (10.35% ± 1.1%) below those obtained with direct infection (Fig. 1). When Wt and Mut antibodies were used at higher concentrations (1 μg/ml), DENV infection was reduced to percentages significantly lower than those observed in direct infections, indicating neutralization. On the other hand, lower antibody concentrations resulted in infection levels similar to those obtained by direct infection. Of note, the antibody concentration (0.04 μg/ml) that resulted in enhanced infection in the FcγR-bearing U937 cells resulted in 50% plaque reduction in a neutralization test (PRNT50) carried out in BHK-21 cells with DENV-4 (data not shown). These results indicate the IgG 1A5-dependent enhancement of DENV infection in human U937-derived macrophages and confirm the significance of the Fc region in mediating this mechanism (12).

Fig 1.

Antibody-dependent enhancement of DENV-4 infection of U937-derived macrophages. Differentiated U937 cells were infected in the presence or absence of 5-fold concentrations of a humanized monoclonal antibody against the DENV E protein. The number of infected cells was determined by flow cytometry. IgG Wt, wild-type 1A5 antibody; IgG Mut, 1A5 antibody with a mutation in the Fc region. The dotted line represents the level of infection with 1 MOI in the absence of antibodies.

Antibody-dependent enhancement of DENV infection induces selective and increased secretion of soluble mediators in U937-derived macrophages.

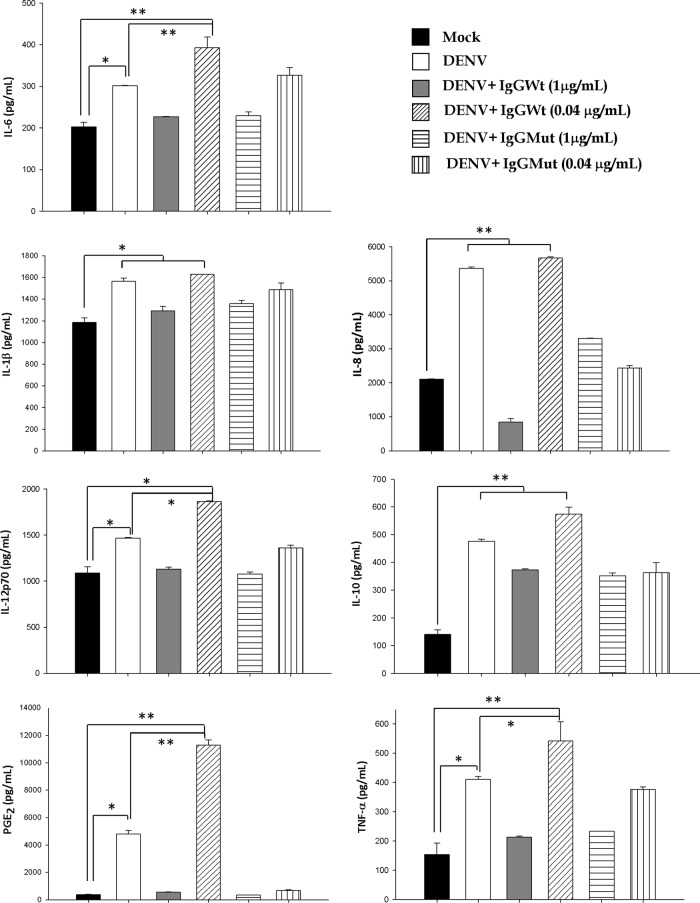

Next, we evaluated if a different cytokine response is observed in U937-derived macrophages infected in the presence of enhancing antibodies versus results for U937-derived macrophages infected directly. Figure 2 and Table 1 show that U937-derived macrophages infected directly show significant production of the proinflammatory mediators IL-6, -8, -1β, -12p70, TNF-α, and PGE2 (P < 0.05) in comparison to results for mock-infected cells. Interestingly, when infection was done in the presence of enhancing concentrations of IgGWt (0.04 μg/ml), significantly higher levels of secretion were observed for the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, -12p70, and TNF-α, as well as PGE2 (P < 0.001). This secretory pattern was not detected in supernatants obtained from U937-derived macrophages infected with DENV under neutralizing conditions employing IgGMut or IgGWt (1 μg/ml) or IgGMut at 0.04 μg/ml. A tendency toward higher levels of IL-10 production was also observed in ADE-DENV infection versus direct infection of cells, although it did not reach significance. No differences were observed between U937-derived macrophages infected with DENV directly and those infected under enhancing conditions for the cytokines IL-8 and IL-1β. U937-derived macrophages stimulated only with antibodies included as controls showed no significant changes in the production of cytokines compared to results under the mock condition (data not shown). These results indicate that infection of U937-derived macrophages with DENV induces the secretion of several soluble factors but that if the infection is carried out in the presence of enhancing antibodies, there is a further increase in the secretion of factors with a proinflammatory profile.

Fig 2.

Cytokine and PGE2 responses of U937-derived macrophages infected with DENV-4 in the presence or absence of facilitating antibodies. Differentiated U937 cells were infected with 1 MOI of DENV-4 in the absence (DENV) or presence of selected concentrations (μg/ml) of wild-type (IgGWt) or mutated (IgGMut) 1A5 humanized monoclonal antibody. Mock-infected cells were also included (Mock). Forty-eight hours postinfection, cell-free supernatants were collected and processed for cytokine quantification by using a BD cytometric bead array (CBA) flex set (BD Biosciences). Simultaneously, PGE2 was determined by using an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kit (EnzoLife Sciences). Each bar represents the mean ± standard error of data from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Cytokine response in scale-up (petri dish) macrophage cultures to evaluate TERa

| Culture condition | Cytokine concn in cell supernatants (pg/ml) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | IL-8a | IL-1β | IL12p70 | IL-10 | TNF-α | |

| Mock | 1,047 ± 77 | 9,295 ± 17 | 347 ± 14 | 1,002 ± 26 | 961 ± 48 | 110 ± 32 |

| DENV | 4,427 ± 41† | 23,650 ± 03† | 1,263 ± 46† | 1,362 ± 11† | 1,372 ± 78† | 1,272 ± 53† |

| IgGWt (1 μg/ml) | 353 ± 67 | 2,410 ± 16 | 198 ± 38 | 1,242 ± 20 | 911 ± 63 | 253 ± 38 |

| IgGWt (0.04 μg/ml) | 6,612 ± 41‡ | 24,999d ± 94 | 3,122 ± 75‡ | 2,755 ± 57‡ | 2,178 ± 77‡ | 4,349 ± 45‡ |

| IgGMut (1 μg/ml) | 1,182 ± 88 | 14,557 ± 57 | 570 ± 09 | 1,362 ± 31 | 870 ± 08 | 256 ± 64 |

| IgGMut (0.04 μg/ml) | 1,782 ± 31 | 10,717 ± 79 | 512 ± 43 | 980 ± 12 | 1,032 ± 11 | 244 ± 10 |

Cell supernatants for each condition were diluted 10-fold in order to estimate the cytokine concentration by CBA (see Materials and Methods). Each value represents the mean ± SD of data from two infection assays. Statistical differences were established as P < 0.05, comparing mock/DENV (†) or DENV/IgGWt (0.04 μg/ml) (‡). The estimated cell amount per culture plate was 10 × 106.

ADE-DENV infection of U937-derived macrophages induces loss of TER.

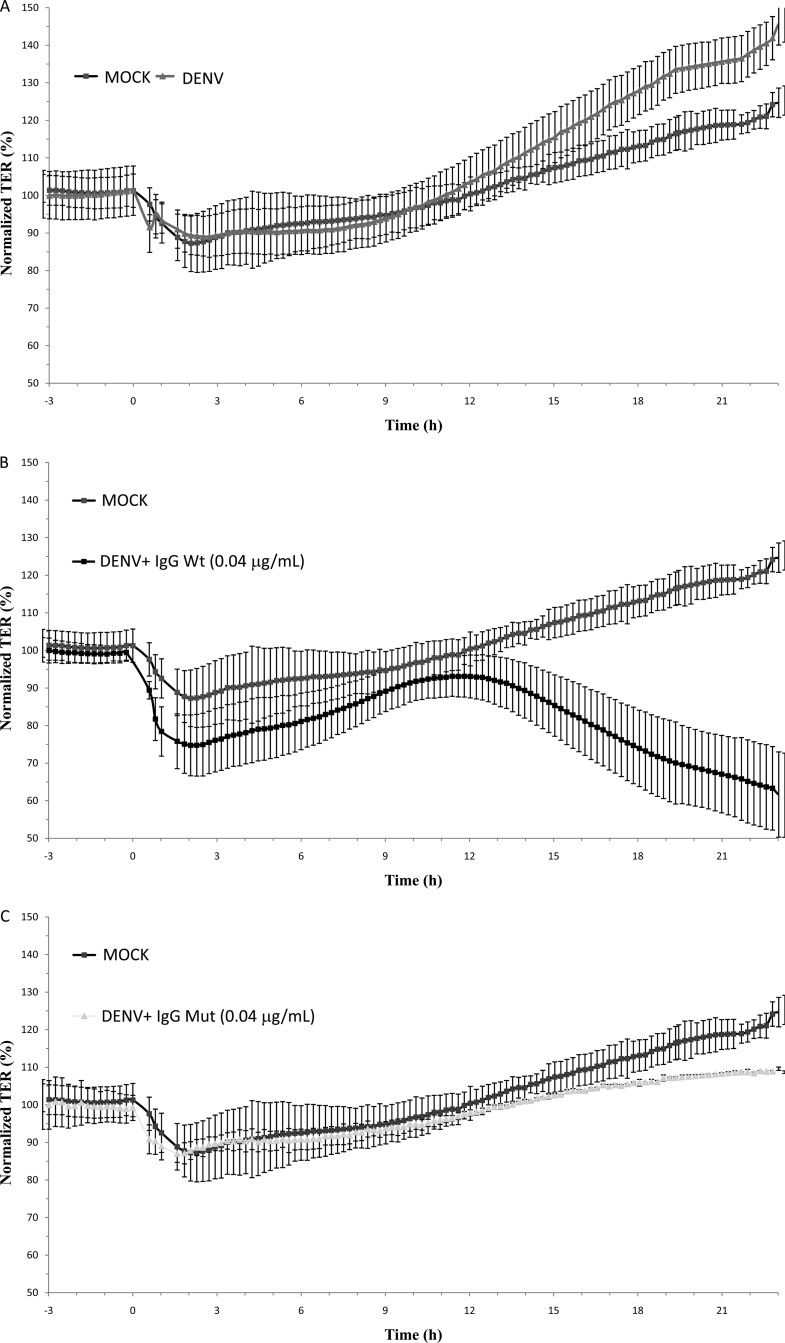

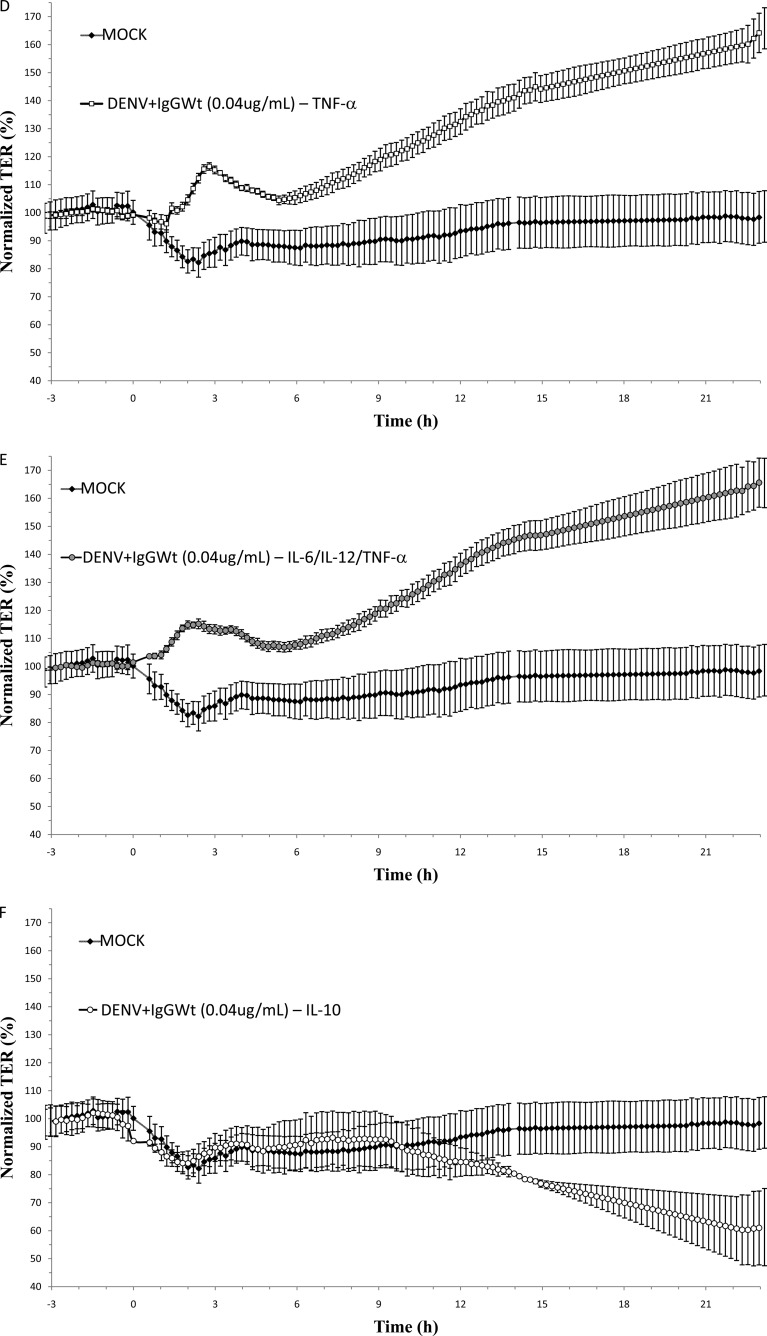

To study the effect of the cytokine response after ADE-DENV infection on the integrity of AJCs, a kinetic analysis of the effect of CM on TER was done with MDCK cell cultures. MDCK cells were chosen since they are a well-established model for studying TJ integrity in vitro (27). As shown in Fig. 3A, CM collected from U937-derived macrophages directly infected with DENV exerted no significant short-term effect on TER of epithelial monolayers compared with results for CM collected from mock-infected cells (average TER, mock infection, 92.6% ± 5.1%, versus DENV, 93.1% ± 4.4%). In contrast, CM derived from U937-derived macrophages infected under ADE conditions (IgGWt, 0.04 1 μg/ml) (ADE-CM) triggered a biphasic response (Fig. 3B), inducing an initial abrupt decrease in TER (average TER, 74.7% ± 8.2%), which shortly after showed a tendency toward recovery (average TER, 91.6% ± 5.9%), but after 13 h of incubation provoked a persistent loss of barrier function to levels of approximately 65%. No loss of barrier function was observed in monolayers treated with CM collected from cells infected in the presence of neutralizing concentrations of both antibodies used at 1 μg/ml or in the presence of Mut antibody used at 0.04 μg/ml (Fig. 3C, D, and E). To discard any effect of CM on the viability of the MDCK monolayers, two independent cell viability tests were carried out. Cell monolayers showed no significant loss in cell viability upon exposure to CM (data not shown), indicating that the loss in TER observed in cells exposed to ADE-DENV CM is a consequence not of a reduction in cell viability but of alterations in the AJCs.

Fig 3.

Effect of U937-derived macrophage conditioned media on the transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) of MDCK cell monolayers cells grown on the Transwell system. Conditioned media collected 48 h postinfection were added to the apical side of MDCK monolayers, and the TER was continuously measured for 24 h by using the cellZscope system (A to E). Values are expressed as normalized TER (%) per hours postexposure. Infection conditions were as indicated in the legend to Fig. 2. Each graph represents the mean ± SD of data from 3 independent experiments.

ADE-DENV-induced barrier dysfunction is prevented by IL-6, IL12p70, and TNF-α depletion.

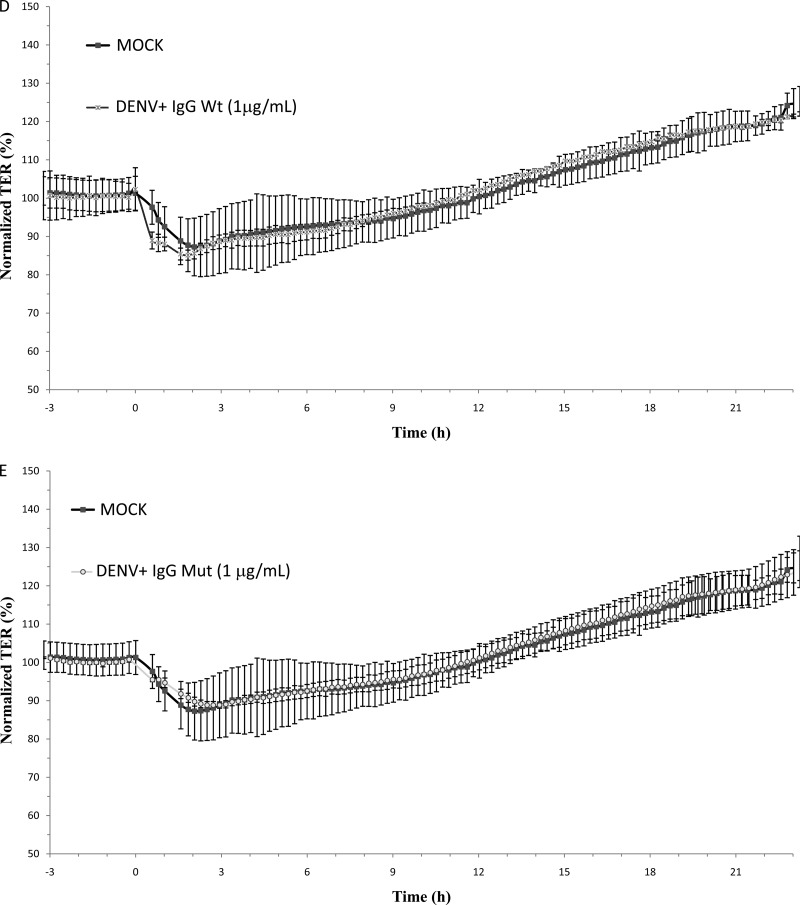

In order to test if IL-6, IL-12p70, and TNF-α are involved in the loss of TER, a subtraction assay was done by immunoprecipitation, using the same beads conjugated to specific antibodies provided by the CBA kit. As a negative control, IL-10 was also depleted from the CM. After immunoprecipitation, a significant reduction in the concentrations of the targeted cytokines but not in the concentration of any of the nontargeted cytokines was observed (data not shown). CM depleted of IL-6, IL-12p70, or TNF-α or all 3 cytokines together lost the capacity to disrupt TER (Fig. 4B, C, D, and E, respectively). In contrast, the depletion of IL-10 did not prevent the decrease in TER (Fig. 4F). It is interesting to note that the absence of any of the 3 cytokines alone was as effective in preventing TER disruption as the absence of all 3 cytokines together. Thus, these results suggest that the increased secretion of IL-6, IL-12p70, and TNF-α by U937-derived macrophages due to ADE-DENV infection is responsible for opening TJs in MDCK monolayers.

Fig 4.

Effect of ADE-depleted supernatant on the transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) of MDCK cell monolayers cells grown on Transwell inserts. Conditioned media collected 48 h postinfection from U937-derived macrophages infected under ADE conditions were used intact (A) or depleted of IL-6 (B), IL-12 (C), TNF-α (D), all 3 cytokines together (E), or IL-10 (F) and added to the apical side of MDCK monolayers. Medium collected from mock-infected cells was used as a control in all experiments. TER was continuously measured for 24 h by using the cellZscope system, and values were expressed as normalized TER (%) per hours postexposure. Each graph represents the mean ± SD of data from 3 independent experiments.

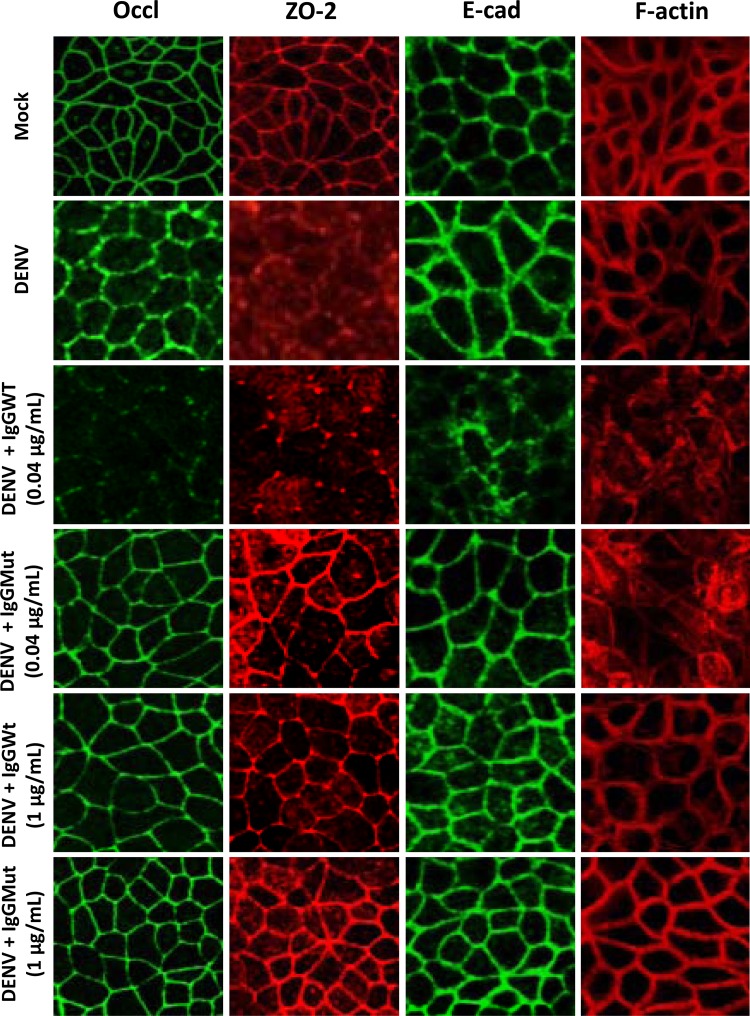

ADE-DENV CM disrupts epithelial barrier function by inducing relocalization and degradation of AJC proteins and cytoskeletal disarrangement.

We next explored if the above-mentioned CM alter the localization of proteins present in the AJC. Figure 5 shows that when MDCK cells were incubated for 24 h with CM derived from mock-infected U937-derived macrophages, the AJ protein E-cadherin and the TJ proteins ZO-2 and occludin localized at the cell borders, forming the typical chicken-fence pattern, and the actin cytoskeleton organized as a perijunctional ring. Instead, when the added CM was collected from U937-derived macrophages directly infected with DENV, ZO-2 delocalized from the cell borders and gave a diffuse staining, while actin surrounded the cell periphery and E-cadherin and occludin displayed a thicker staining at the cell borders. However, when CM was collected from U937-derived macrophages infected with DENV under neutralizing conditions, the distribution of E-cadherin, ZO-2, occludin, and F-actin resembled that of monolayers treated with CM derived from mock-infected U937-derived macrophages, thus indicating that CM derived from DENV-infected cells is responsible for the delocalization of ZO-2. Instead, incubation of the epithelial monolayers with CM derived from U937-derived macrophages infected under ADE conditions disarrayed the peripheral localization of E-cadherin, ZO-2, occludin, and actin. Since these effects were not observed with the CM derived from U937-derived macrophages infected with DENV in the presence of mutant antibodies, we conclude that the response induced under ADE conditions is responsible for the delocalization of E-cadherin, occludin, and F-actin that leads to the decrease in TER.

Fig 5.

Localization of apical-junction complex (AJC) proteins on epithelial monolayers exposed to conditioned media by immunofluorescence assay. MDCK cells grown on the Transwell system were exposed to U937-derived macrophage-conditioned supernatants. After 24 h, the presence and distribution of the tight-junction proteins ZO-2 and occludin (Occl), the adherent junction protein E-cadherin (E-cad), and polymerized actin (F-actin) were evaluated by immunofluorescence assay. Infection conditions were as indicated in the legend to Fig. 2.

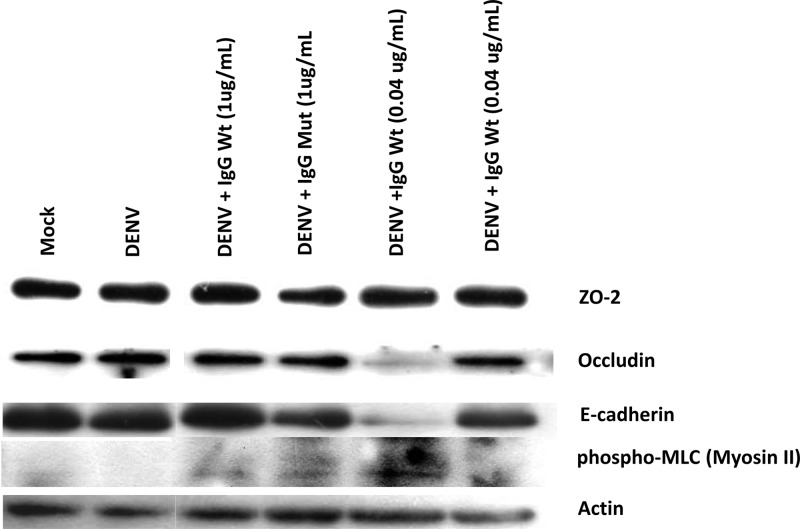

To further study the effect of ADE on the AJC, we analyzed by WB the expression of ZO-2, occludin, and E-cadherin in MDCK monolayers incubated with the U937-derived macrophage CM (Fig. 6). We also analyzed phosphorylated (Ser19) myosin light chain (p-MLC), since accumulating evidence indicates that the phosphorylation of this protein, predominantly dependent on myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), triggers the contraction of the perijunctional actinomyosin ring and TJ opening (15). Figure 6 shows that CM derived from U937-derived macrophages infected with DENV under ADE conditions decreased in a significant manner the amount of occludin and E-cadherin and augmented the expression of p-MLC in comparison to the content of these proteins present in monolayers treated with CM from mock-infected U937-derived macrophages or infected directly with DENV. No effects were observed when mutant antibodies were employed, therefore suggesting that the CM generated by ADE is responsible for inducing the contraction of the perijunctional actinomyosin ring, the decreased expression of proteins of the AJC, and the opening of the TJ.

Fig 6.

Apical-junction complex proteins expression from MDCK epithelial monolayers after treatment with conditioned medium. Cell lysates from MDCK cultures exposed for 24 h to U937-derived macrophage-conditioned supernatants were analyzed by Western blotting to evaluate ZO-2, occludin, E-cadherin, and the phosphorylated form of myosin light chain 2 (p-MLC). Protein concentrations were determined using film densitometry and signal comparison to beta-actin expression, included as a loading control.

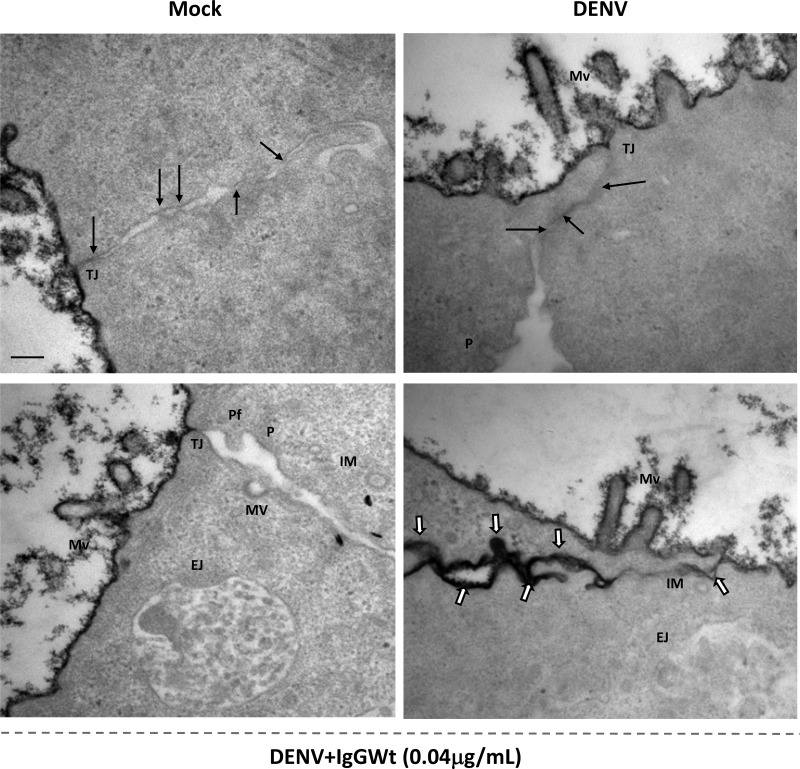

Ultrastructural analysis of epithelial monolayers revealed leaky TJs. To further characterize the effect of CM on TJ integrity, MDCK cells grown on Transwell inserts were exposed to U937-derived macrophage CM for 24 h and processed for TEM. Ruthenium red was added to mark the apical surface and the paracellular pathways of leaky monolayers. In the presence of CM from mock- and DENV-infected cells, ruthenium red stained only the apical surface of MDCK cells and did not penetrate the lateral membrane, indicating that TJs are sealed. In contrast, in cells incubated with CM from ADE-DENV-infected U937-derived macrophages, the stain penetrated the paracellular pathway, indicating the presence of leaky TJs (Fig. 7). Furthermore, in the cells exposed to the CM from ADE-DENV, the formation of membrane vesicles, protrusions, endocytosed junction, and protruding fingers was observed (Fig. 7).

Fig 7.

Changes in intercellular junctions of epithelial monolayers after treatment with conditioned media. MDCK cells grown on the Transwell system were exposed to U937-derived macrophage-conditioned supernatants for 24 h and processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM), following standard protocols (see Materials and Methods). Samples were incubated with ruthenium red to determine the integrity of TJs. Infection conditions were as indicated in the legend to Fig. 2. Mv, microvilli; TJ, tight junction; MV, membrane vesicles; P, protrusions; EJ, endocytosed junctions; Pf, protruding fingers; IM, internal membranes. Arrows indicate electron-dense zones characteristic of membrane kisses of TJs. White arrows show infiltrated ruthenium red. Scale bar = 0.2 μm.

ADE-DENV CM increase vascular permeability in vivo.

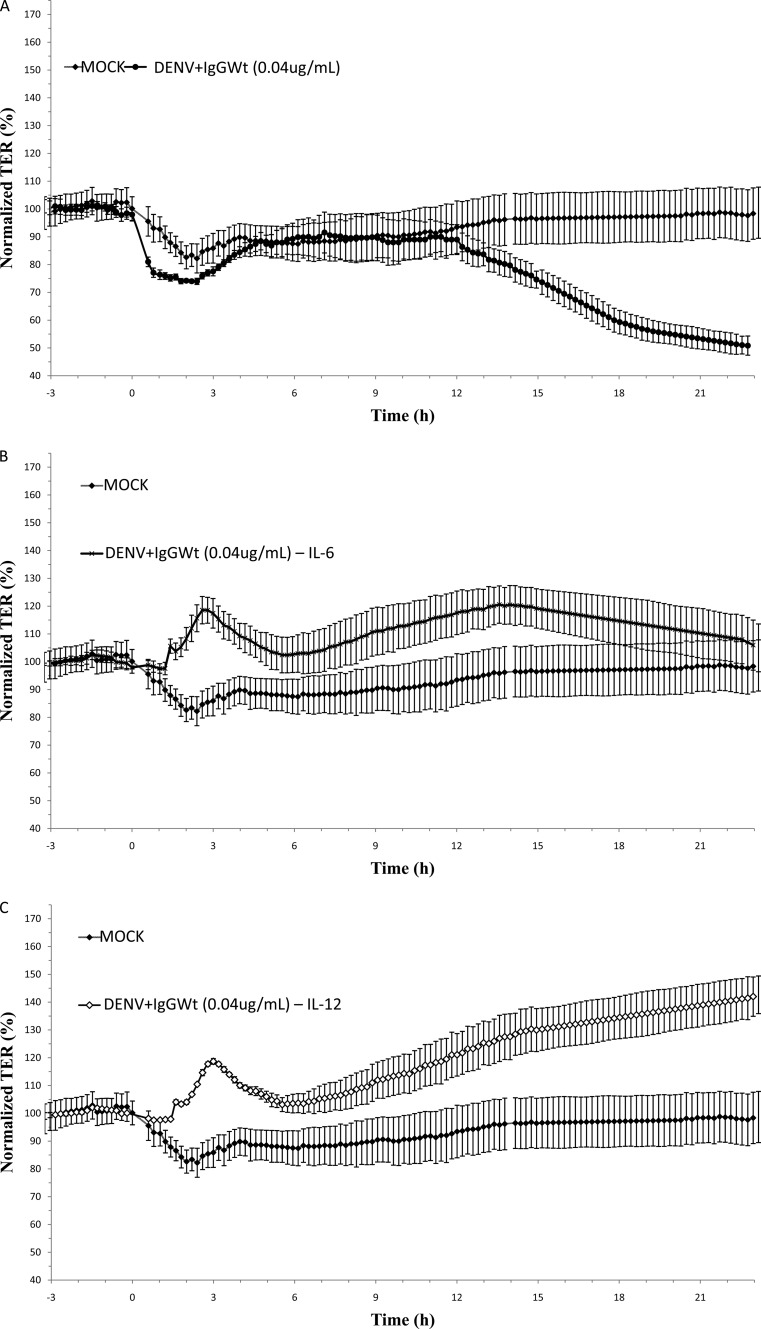

To associate cytokine production, AJC dysfunction, and plasma leakage, we evaluated whether CM from ADE-DENV-infected U937-derived macrophages that caused epithelial barrier dysfunction could also increase vascular permeability. For this purpose, we evaluated in a mouse model the concentration of EVD in the bloodstream and in lungs after intraperitoneal injections of CM. An increase in the circulation of EVD was observed in the bloodstream of mice injected with DENV-CM (14 ng/ml) and even a significantly higher increase was observed in mice injected with ADECM (32 ng/ml) (Fig. 8, top). When EVD staining in lung tissue extracts was evaluated, only the ADE-CM induced a significant increase (Fig. 8, bottom). These results suggest that the VPS and the pleural effusion present during SD may be a consequence of the AJC disruption observed in our in vitro assays.

Fig 8.

Effect of U937-derived macrophage conditioned media on vascular permeability in vivo. Six- to eight-week-old mice (CD1 strain) were twice injected intraperitoneally, along with a solution of 1% Evans blue dye (EVD). Twenty-four hours later, EVD was extracted from plasma and lungs and quantified against a standard curve. Values are expressed as ng/ml. Four mice were included per condition. Statistical significance was as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

SD is the most complicated and life-threatening manifestation of the DENV infection, characterized by increased capillary permeability, severe plasma leakage, respiratory distress, and extensive pleural effusion (1). Preexisting antibodies and increased cytokine levels in patients play an important role in the pathogenesis of SD during secondary DENV infection (10). However, the ultimate mechanisms leading to the pathogenesis of the SD are not fully understood. In this work, we present evidence linking the infection of U937-derived macrophages under ADE conditions with the capacity to disrupt TJ in vitro and to induce plasma leakage in vivo. Goncálvez et al. (12) designed two humanized antibodies for studying the ADE-DENV infection in different Fcγ receptor (FcγR)-bearing cells that were used in this study. In accordance with the work of Goncalvez et al. (12), our results showed that the wild-type (IgGWt) but not the Fc-mutated antibody induced an enhanced number of DENV-infected U937-derived macrophages when used at subneutralizing concentrations (Fig. 1). Moreover, no enhancement of infection was observed when virus-antibody complexes, formed at different antibody dilutions, were used to infect non-FcγR-bearing cells (data not shown). These results indicate that the observed increase in the number of U937 infected cells was due only to ADE of infection and allowed us to determine the specific cytokine response induced under these circumstances.

The presence of enhancing antibodies in DENV infection not only facilitates virus entry but also regulates several cell signaling pathways (31). The effect of direct or ADE-DENV infection on the production of soluble factors from U937-derived macrophages is only partially understood. The direct comparison of the cytokine response of U937-derived macrophages infected directly or in the presence of facilitating antibodies showed that the cytokine response of the latter is biased toward a proinflammatory profile. TNF-α, IL-12p70, IL-6, and PGE2 secretion was significantly increased, while other cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-10, were secreted at equal levels under the two conditions (Fig. 2). These results indicate that ADE-DENV infection induces a typical but substantially higher proinflammatory response than direct DENV infection in U937-derived macrophages. The fact that the secretion of all cytokines under ADE conditions is not equally exacerbated suggests an immune regulation role of the antibody-mediated infection toward the secretion of proinflammatory factors. These findings are in agreement with those of other ADE-DENV studies carried out in vitro for which a high production of these soluble factors from monocytic cell lines, resulting in evasion of antiviral responses, such as type I interferon (IFN-β) and the nitric oxide production (32), was reported. In line with this notion, our data provide new evidence that ADE-DENV infection induces selective production of several proinflammatory factors that may promote synergistic interactions with intracellular signaling pathways to facilitate the enhancing of infection and virus production. Future studies aiming to dissect the signal transduction pathways activated in macrophages infected directly or under ADE conditions are necessary to fully understand the ADE process and the profile of cytokines induced by it (31). Our results are also in agreement with those of studies that have found increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines in sera of patients with SD, in which, among other cytokines, increased levels of TNF-α, IL-12p70, and IL-6 have been reported (33–37). The “cytokine storm” described years ago as the excessive release of proinflammatory cytokines in several infectious diseases has been associated to SD (38). This phenomenon is supported by several clinical and in vitro studies in which increased concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-12p70, IL-10, and PGE2 were connected to hemorrhage and to the immune response observed in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from patients with SD (39–49). Our data suggest a cytokine secretion profiles that is more specific than a “storm” in macrophages infected under ADE conditions that may play a leading role in the pathogenesis of VPS by inducing a bias toward a T-helper-2 response (50).

The mechanisms associated with the development of vascular permeability and increased plasma leakage observed in patients with VPS remain unclear (1, 26). Our results showed that only CM that originated with U937-derived macrophages infected under ADE conditions was able to induce a significant and irreversible disruption of TER, indicating that the epithelial barrier function was altered (Fig. 3B). Unexpectedly, this effect was shown to be specific to ADE-CM, since no other condition of infection was able to modify TER values (Fig. 3A and C to E). Previous studies aiming to understand the role of DENV infection in increased vascular permeability have also reported important changes in either epithelial or endothelial barrier permeability after interaction with CM from DENV-infected cells (51, 52).

Few articles have associated the increased vascular permeability observed in primary endothelial cells with the presence of particular mediators, like the high-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) (53), the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MMIF) (54), IL-8 (55), matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) (56), and the nonstructural protein 4 (NS4B) of DENV (57). Regarding DENV infection and cytokines, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12 are thought to be associated with potentially fatal plasma leakage (17), and some of these soluble factors are known to alter barrier permeability in epithelial or endothelial cells in vitro (58–60). Our results showed that CM depleted of IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α alone lost the capacity to disrupt the barrier function (Fig. 4B to E). These results suggest that alterations in the barrier function after interaction with ADE-CM are not due to any particular cytokine but rather are a consequence of the concerted action of vasoactive and proinflammatory molecules, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and immunoregulators like IL-12p70 (61, 62). This evidence indicates that the epithelial barrier dysfunction observed as a reduction in TER is a consequence of circulating soluble factors present in the ADE-CM. Interestingly, a recent report suggests that cytokine factors present in serum samples collected from patients with SD induced morphological alterations in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) with perturbations in the ZO-1 and VE-cadherin proteins (63). Thus, a risk connection between the proinflammatory immune response of ADE-DENV-infected macrophages and the phenomenon of barrier dysfunction observed in patients with VPS can now be proposed.

TJs and AJs are multiprotein complexes composed of peripheral and integral proteins, such as the ZO protein family, occludin, claudins, the junctional adhesion molecule (JAM), and E-cadherin, that along with the actin cytoskeleton encircle each epithelial/endothelial cell (64). Exposure of monolayers to ADE-CM induced a significant disarrangement of occludin, ZO-2, and E-cadherin (Fig. 5), which was not observed when control CM was used. A certain disarrangement in the localization of occludin and ZO-2 but not E-cadherin was observed in cells exposed to CM derived from cells directly infected with DENV, but the induced damage did not appear to be sufficient to cause a drop in the TER or a leakiness to ruthenium red (Fig. 4A and 7). In addition, the structural and functional integrity of the TJ depends on the presence of a perijunctional ring of actin and myosin, which can also contribute to the regulation of paracellular permeability (64, 65). Our data showed no actin cytoskeleton disruption in cell monolayers exposed to mock or neutralizing conditions as well as DENV-CM (Fig. 5). In contrast, treatment with ADE-CM showed an increased amount of stress fibers and focal adhesion structures widely associated with actin depolymerization processes (Fig. 5). The actin cytoskeleton regulates barrier function by retracting microfilaments from the plasma membrane via myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation (65–67). Our results showed phosphorylation of MLC in epithelial monolayers treated with ADE-CM, suggesting that the increased cytoskeletal disarrangement induce by ADE-CM might result from MLC phosphorylation (Fig. 6).

The degradation of several AJC components has also been associated with barrier dysfunction (68–72). We observed that exposure to ADE-CM decreased the amount of occludin and E-cadherin, although no changes in the concentration of ZO-2 were detected (Fig. 6). The ultrastructural studies show the formation of internal double membranes and small vesicles with electron-dense materials inside, as well as invagination protrusions in these cells, suggesting that endocytosis processes (Fig. 7), a well-known mechanism of turnover or disruption of TJs in polarized cells (72, 73), are taking place. Taken together, these results demonstrate that ADE-CM reduces TER in epithelial monolayers by reducing the expression of AJC proteins via endocytosis-mediated degradation probably triggered by actin contraction after MLC phosphorylation. For DENV infection, Talavera et al. (55) suggested that the transendothelial permeability observed in human dermal microvascular endothelial cell (HMEC-1) cultures was due to changes in actin cytoskeleton and TJs associated with IL-8 production by DENV-infected monolayers.

Disruption of TJs has been associated with the pathogenicity of West Nile virus (WNV) (74, 75). Recently, Xu et al. (75) reported that WNV, a related flavivirus, induces the endocytosis of TJ membrane proteins, including claudin 1 and JAM-1, in infected epithelial and endothelial cells. However, DENV infection of those cells did not affect TJs. Previous reports have also shown that epithelial and endothelial barrier function is not significantly affected after direct infection (51, 52, 76). In our hands, direct apical infection of MDCK cells with DENV did not show any significant change in TER (C. Mosso, J. E. Ludert, and R. M. Del Angel, unpublished data). These data, together with the subtraction data, suggest that direct infection of MDCK cells by virions present in the cell supernatants is not responsible for the TER reduction observed in this study and support the role of soluble factors in barrier dysfunction occurring with ADE-DENV supernatants. In addition, the integrity of the monolayers observed in the fluorescence studies, plus the results obtained with the cytotoxicity assays, indicates that the observed TER disruption is not due to cell cytotoxicity or to a disruption of the monolayers.

One limitation of this study is the use of epithelial MDCK cells to evaluate barrier dysfunctions. In order to circumvent, at least partially, this limitation, a mouse model was used to evaluate the effect of CM in barrier dysfunction in vivo. The results obtained after EVD quantification in plasma and lung extracts suggest that only ADE-CM was able to induce a significant increase in vascular permeability in vivo (Fig. 8). Thus, our data strongly suggest that the alterations in TJs observed in vitro might also be taking place in vivo.

Endothelial cells separate the blood from underlying tissues and control the movement of solutes and fluid from the vascular space to the tissue (77). In this process, the AJC, constituted by TJs and AJs, is crucial (64, 78). The results of this study link ADE infection by DENV with the increased vascular permeability associated with plasma leakage in patients affected by SD and expand knowledge about the crucial role played by cytokines in relation to TJs in this process.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by grants 103783 to and 127447 from The Mexican Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT) to J.E.L. and R.M.D.A., respectively. H.P.-G. and A.R.S. are recipients of CONACYT (Mexico) scholarships.

We thank Lizbeth Salazar Villatoro for her technical assistance with the EM processes and Patricia Carvajal for her assistance with the figures.

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO 2009. Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. Fact sheet no. 117. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/ Accessed 16 October 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. 2003. A ligand-binding pocket in the dengue virus envelope glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:6986–6991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Y, Corver J, Chipman PR, Zhang W, Pletnev SV, Sedlak D, Baker TS, Strauss JH, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2003. Structures of immature flavivirus particles. EMBO J. 22:2604–2613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martina BE, Koraka P, Osterhaus AD. 2009. Dengue virus pathogenesis: an integrated view. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22:564–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alcaraz-Estrada SL, Yocupicio-Monroy M, del Angel RM. 2010. Insights into dengue virus genome replication. Future Virol. 5:575–592 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Welsch S, Miller S, Romero-Brey I, Merz A, Bleck CK, Walther P, Fuller SD, Antony C, Krijnse-Locker J, Bartenschlager R. 2009. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe 23:365–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stiasny K, Heinz FX. 2006. Flavivirus membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 87:2755–2766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Basu A, Chaturvedi UC. 2008. Vascular endothelium: the battle field of dengue viruses. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 53:287–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walleza B, Huber P. 2008. Endothelial adherens and tight junctions in vascular homeostasis, inflammation and angiogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778:794–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Halstead SB, O'Rourke E. 1977. Antibody-enhanced dengue virus infection in primate leukocytes. Nature 265:739–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ubol S, Halstead SB. 2010. How innate immune mechanisms contribute to antibody-enhanced viral infections. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:1829–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goncálvez AP, Engle RE, Claire MS, Purcell RH, Lai CJ. 2007. Monoclonal antibody-mediated enhancement of dengue virus infection in vitro and in vivo and strategies for prevention. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:9422–9427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morens D, Halstead SB. 1990. Measurement of antibody-dependent infection enhancement of four dengue virus serotypes by monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 71:2909–2914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Halstead SB, O'Rourke EJ. 1977. Dengue viruses and mononuclear phagocytes. I. Infection enhancement by non-neutralizing antibody. J. Exp. Med. 146:201–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kliks SC, Nisalak A, Brandt WE, Wahl L, Burke DS. 1989. Antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus growth in human monocytes as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 40:444–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Puerta-Guardo H, Mosso C, Medina F, Liprandi F, Ludert JE, del Angel RM. 2010. Antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection in U937 cells requires cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains. J. Gen. Virol. 91:394–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaturvedi UC, Agarwal R, Elbishbishi EA, Mustafa AS. 2000. Cytokine cascade in dengue hemorrhagic fever: implications for pathogenesis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 28:183–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Green S, Rothman A. 2006. Immunopathological mechanisms in dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 19:429–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Halstead S. 1989. Antibody, macrophages, dengue virus infection, shock and hemorrhage: a pathogenic cascade. Rev. Infect. Dis. 11:S830–S839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rothman AL. 2011. Immunity to dengue virus: a tale of original antigenic sin and tropical cytokine storms. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11:532–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Balsitis SJ, Williams KL, Lachica R, Flores D, Kyle JL, Mehlhop E, Johnson S, Diamond MS, Beatty PR, Harris E. 2010. Lethal antibody enhancement of dengue disease in mice is prevented by Fc modification. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000790. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chareonsirisuthigul T, Kalayanarooj S, Ubol S. 2007. Dengue virus (DENV) antibody-dependent enhancement of infection upregulates the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, but suppresses anti-DENV free radical and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, in THP-1 cells. J. Gen. Virol. 88:365–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ubol S, Phuklia W, Kalayanarooj S, Modhiran N. 2010. Mechanisms of immune evasion induced by a complex of dengue virus and preexisting enhancing antibodies. J. Infect. Dis. 201:923–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boonnak K, Slike BM, Burgess TH, Mason RM, Wu SJ, Sun P, Porter K, Rudiman IF, Yuwono D, Puthavathana P, Marovich MA. 2008. Role of dendritic cells in antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection. J. Virol. 82:3939–3951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boonnak K, Dambach KM, Donofrio GC, Tassaneetrithep B. 2011. Cell type specific and host polymorphisms influence antibody dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection. J. Virol. 85:1671–1683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Simmons CP, Farrar JJ, van Vinh Chau N, Wills B. 2012. Dengue. N. Engl. J. Med. 366:1423–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gonzalez-Mariscal L, Chávez de Ramírez B, Cereijido M. 1985. Tight junction formation in cultured epithelial cells (MDCK). J. Membr. Biol. 86:113–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mosso C, Galván-Mendoza IJ, Ludert JE, del Angel RM. 2008. Endocytic pathway followed by dengue virus to infect the mosquito cell line C6/36 HT. Virology 378:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Manaenkoa A, Chena H, Kammerd J, Zhanga JH, Tanga J. 2011. Comparison Evans Blue injection routes: intravenous versus intraperitoneal, for measurement of blood-brain barrier in a mice hemorrhage model. J. Neurosci. Methods 195:206–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, McVerry BJ, Burne MJ, Rabb H, Pearse D, Tuder RM, Garcia JGN. 2004. Protective effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate in murine endotoxin-induced inflammatory lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169:1245–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Flipse J, Wilschut J, Smit JM. 2012. Molecular mechanisms involved in antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection in humans. Traffic. 10.1111/tra.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Modhiran N, Kalayanarooj S, Ubol S. 2010. Subversion of innate defenses by the interplay between DENV and pre-existing enhancing antibodies: TLRs signaling collapse. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4:e924. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nguyen TH, Lei HY, Nguyen TL, Lin YS, Huang KJ, Lien LB, Lin CF, Yeh TM, Do QH, Vu TQ, Chen LC, Huang JH, Lam TM, Liu CC, Halstead SB. 2004. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in infants: a study of clinical and cytokine profiles. J. Infect. Dis. 189:221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Green S, Vaughn DW, Kalayanarooj S, Nimmannitya S, Suntayakorn S, Nisalak A, Lew R, Innis BL, Kurane I, Rothman AL, Ennis FA. 1999. Early immune activation in acute dengue illness is related to development of plasma leakage and disease severity. J. Infect. Dis. 179:755–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ubol S, Masrinoul P, Chaijaruwanich J, Kalayanarooj S, Charoensirisuthikul T, Kasisith J. 2008. Differences in global gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells indicate a significant role of the innate responses in progression of dengue fever but not dengue hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1459–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bozza FA, Cruz OG, Zagne S, Azeredo E, Nogueira R, Assis EF, Bozza PT, Kubelka CF. 2008. Multiplex cytokine profile from dengue patients: MIP-1beta and IFN-gamma as predictive factors for severity. BMC Infect. Dis. 8:86. 10.1186/1471-2334-8-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Restrepo BN, Ramirez RE, Arboleda M, Alvarez G, Ospina M, Diaz FJ. 2008. Serum levels of cytokines in two ethnic groups with dengue virus infection. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79:673–677 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Clark IA. 2007. The advent of the cytokine storm. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:271–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hober D, Poli L, Roblin B, Gestas P, Chungue E, Granic G, Imbert P, Pecarere JL, Vergez-Pascal R, Wattre P, Maniez-Montreuil M. 1993. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta) in dengue-infected patients. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 48:324–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chakravarti A, Kumaria R. 2006. Circulating levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha & interferon-gamma in patients with dengue & dengue haemorrhagic fever during an outbreak. Indian J. Med. Res. 123:25–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pérez AB, García G, Sierra B, Alvarez M, Vázquez S, Cabrera MV, Rodríguez R, Rosario D, Martínez E, Denny T, Guzmán MG. 2004. IL-10 levels in dengue patients: some findings from the exceptional epidemiological conditions in Cuba. J. Med. Virol. 73:230–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bethell DB, Flobbe K, Cao XT, Day NP, Pham TP, Buurman WA, Cardosa WJ, White NJ, Kwiatkowski D. 1998. Pathophysiologic and prognostic role of cytokines in dengue hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 177:778–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fernandez-Mestre MT, Gendzekhadze K, Rivas-Vetencourt P, Layrisse Z. 2004. TNF-alpha-308A allele, a possible severity risk factor of hemorrhagic manifestation in dengue fever patients. Tissue Antigens 64:469–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Perez AB, Sierra B, Garcia G, Aguirre E, Babel N, Alvarez M, Sanchez L, Valdés L, Volk H, Guzman MG. 2010. TNF-alpha, TGF-beta 1 and IL-10 gene polymorphisms: implication in protection or susceptibility to dengue hemorrhagic fever. Hum. Immunol. 71:1135–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Raghupathy R, Chaturvedi UC, Al-Sayer H, Elbishbishi EA, Agarwal R, Nagar R, Kapoor RS, Misra A, Mathur A, Nusrat H, Azizieh F, Khan MAY, Mustafa AS. 1998. Elevated levels of IL-8 in dengue hemorrhagic fever. J. Med. Virol. 56:280–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bosch I, Xhaja K, Estevez L, Raines G, Melichar H, Warke RV, Fournier MV, Ennis FA, Rothman AI. 2002. Increased production of interleukin-8 in primary human monocytes and in human epithelial and endothelial cell lines after dengue virus challenge. J. Virol. 76:5588–5597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pacsa AS, Agarwal R, Elbishbishi EA, Chaturvedi UC, Nagar R, Mustafa AS. 2000. Role of interleukin-12 in patients with dengue hemorrhagic fever. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 28:151–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cardier JE, Mariño E, Romano E, Taylor P, Liprandi F, Bosch N, Rothman AI. 2005. Proinflammatory factors present in sera from patients with acute dengue infection induce activation and apoptosis of human microvascular endothelial cells: possible role of TNF-α in endothelial cell damage in dengue. Cytokine 30:359–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wu WL, Ho LJ, Chang DM, Chen CH, Lail JH. 2009. Triggering of DC migration by dengue virus stimulation of COX-2-dependent signaling cascades in vitro highlights the significance of these cascades beyond inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 39:3413–3422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chaturvedi UC. 2009. Shift to Th2 cytokine response in dengue haemorrhagic fever. Indian J. Med. Res. 129:1–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carr JM, Hocking H, Bunting K, Wright PJ, Davidson A, Gamble J, Burrell CJ, Li P. 2003. Supernatants from dengue virus type-2 infected macrophages induce permeability changes in endothelial cell monolayers. J. Med. Virol. 69:521–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dewi BE, Takasaki T, Kurane I. 2008. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells increase the permeability of dengue virus-infected endothelial cells in association with down-regulation of vascular endothelial cadherin. J. Gen. Virol. 89:642–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ong SP, Lee LM, Leong YFI, Ng ML, Chu JJH. 2012. Dengue virus infection mediates HMGB1 release from monocytes involving PCAF acetylase complex and induces vascular leakage in endothelial cells. PLoS One 7:e41932. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chuang YC, Lei HY, Liu HS, Lin YS, Fu TF, Yeh TM. 2011. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor induced by dengue virus infection increases vascular permeability. Cytokine 54:222–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Talavera D, Castillo AM, Dominguez MC, Escobar-Gutierrez A, Meza I. 2004. IL8 release, tight junction and cytoskeleton dynamic reorganization conducive to permeability increase are induced by dengue virus infection of microvascular endothelial monolayers. J. Gen. Virol. 85:1801–1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Luplertlop N, Missé D, Bray D, Deleuze V, Gonzalez JP, Leardkamolkarn V, Yssel H, Veas F. 2006. Dengue-virus-infected dendritic cells trigger vascular leakage through metalloproteinase overproduction. EMBO Rep. 7:1176–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kelley JF, Kaufusi PH, Nerurkar VR. 2012. Dengue hemorrhagic fever-associated immunomediators induced via maturation of dengue virus nonstructural 4B protein in monocytes modulate endothelial cell adhesion molecules and human microvascular endothelial cells permeability. Virology 422:326–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dewi BE, Takasaki T, Kurane I. 2004. In vitro assessment of human endothelial cell permeability: effects of inflammatory cytokines and dengue virus infection. J. Virol. Methods 121:171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jacobs M, Levin M. 2002. An improved endothelial barrier model to investigate dengue haemorrhagic fever. J. Virol. Methods 104:173–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bonner SM, O'Sullivan MA. 1998. Endothelial cell monolayers as a model system to investigate dengue shock syndrome. J. Virol. Methods 71:159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Montesano R, Soulie P, Eble JA, Carrozzino F. 2005. Tumor necrosis factor alpha confers an invasive, transformed phenotype in mammalian epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 118:3487–3500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jones SA, Horiuchi S, Topley N, Yamamoto N, Fuller GM. 2001. The soluble interleukin 6 receptor: mechanisms of production and implications in disease. FASEB J. 15:43–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Appanna R, Wang SM, Ponnampalavanar SA, Lum LC, Sekaran SD. 2012. Cytokine factors present in dengue patient sera induces alterations of junctional proteins in human endothelial cells. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 87:936–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. González-Mariscal L, Tapia R, Chamorro D. 2008. Crosstalk of tight junction components with signaling pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778:729–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Meza I, Sabanero M, Stefani E, Cereijido M. 1982. Occluding junctions in MDCK cells: modulation of transepithelial permeability by the cytoskeleton. J. Cell. Biochem. 18:407–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Clayburgh DR, Barrett TA, Tang Y, Meddings JB, Van Eldik LJ, Watterson DM, Clarke LL, Mrsny RJ, Turner JR. 2005. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase-dependent barrier dysfunction mediates T cell activation-induced diarrhea in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 115:2702–2715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Blair SA, Kane SV, Clayburgh DR, Turner JR. 2006. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase expression and activity are upregulated in inflammatory bowel disease. Lab. Invest. 86:191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Matsuda M, Kubo A, Furuse M, Tsukita S. 2004. A peculiar internalization of claudins, tight junction specific adhesion molecules, during the intercellular movement of epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 117:1247–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Utech M, Mennigen R, Bruewer M. 2010. Endocytosis and recycling of tight junction proteins in inflammation. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010:484987. 10.1155/2010/484987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ivanov AI, Nusrat A, Parkos CA. 2004. Endocytosis of epithelial apical junctional proteins by a clathrin-mediated pathway into a unique storage compartment. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:176–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Marchiando AM, Shen L, Graham WV, Weber CR, Schwarz BT, Austin JR. 2010. Caveolin-1-dependent occludin endocytosis is required for TNF-induced tight junction regulation in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 189:111–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Shen L, Turner JR. 2005. Actin depolymerization disrupts tight junctions via caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:3919–3936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bojarski C, Weiske J, Schöneberg T, Schröder W, Mankertz J, Schulzke JD, Florian P, Fromm M, Tauber R, Huber T. 2004. The specific fates of tight junction proteins in apoptotic epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 117:2097–2107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Medigeshi GR, Hirsch AJ, Brien JD, Uhrlaub JL, Mason PW, Wiley C, Nikolich-Zugish J, Nelson JA. 2009. West Nile virus capsid degradation of claudin proteins disrupts epithelial barrier function. J. Virol. 83:6125–6134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Xu Z, Waeckerlin R, Urbanowski MD, van Marle G, Hobman TC. 2012. West Nile virus infection causes endocytosis of a specific subset of tight junction membrane proteins. PLoS One 7:e37886. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Patkar C, Giaya K, Libraty DH. 2013. Dengue virus type 2 modulates endothelial barrier function through CD73. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 88:89–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dejana E. 2004. Endothelial cell-cell junctions: happy together. Nat. Rev. 5:261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Niessen CM. 2007. Tight junctions/adherens junctions: basic structure and function. J. Investig. Dermatol. 127:2525–2532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]