Abstract

Purpose.

Mutations in the RP2 gene are associated with 10% to 15% of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP), a debilitating disorder characterized by the degeneration of retinal rod and cone photoreceptors. The molecular mechanism of pathogenesis of photoreceptor degeneration in XLRP-RP2 has not been elucidated, and no treatment is currently available. This study was undertaken to investigate the pathogenesis of RP2-associated retinal degeneration.

Methods.

We introduced loxP sites that flank exon 2, a mutational hotspot in XLRP-RP2, in the mouse Rp2 gene. We then produced Rp2-null allele using transgenic mice that expressed Cre-recombinase under control of the ubiquitous CAG promoter. Electroretinography (ERG), histology, light microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and immunofluorescence microscopy were performed to ascertain the effect of ablation of Rp2 on photoreceptor development, function, and protein trafficking.

Results.

Although no gross abnormalities were detected in the Rp2null mice, photopic (cone) and scotopic (rod) function as measured by ERG showed a gradual decline starting as early as 1 month of age. We also detected slow progressive degeneration of the photoreceptor membrane discs in the mutant retina. These defects were associated with mislocalization of cone opsins to the nuclear and synaptic layers and reduced rhodopsin content in the outer segment of mutant retina prior to the onset of photoreceptor degeneration.

Conclusions.

Our studies suggest that RP2 contributes to the maintenance of photoreceptor function and that cone opsin mislocalization represents an early step in XLRP caused by RP2 mutations. The Rp2null mice should serve as a useful preclinical model for testing gene- and cell-based therapies.

Keywords: Rp2, retina, photoreceptor

This study reports generation and characterization of a mouse model of Rp2-mediated retinal degeneration and shows that cone opsin mislocalization is an early step in the pathogenesis of associated disease.

Introduction

Photoreceptors are highly metabolically active neurons that develop a distinct inner segment and a photosensitive outer segment by stringently regulated protein expression and polarized transport pathways. The outer segment is a modified sensory cilium and consists of membranous discs loaded with photopigment opsin (rhodopsin in rods and cone opsins in cone photoreceptors).1,2 Two types of cone opsins are expressed in mice: short-wavelength (S) opsin and medium-wavelength (M) opsin. In humans, however, an additional long-wavelength opsin is also present.3,4 Differentiation and functional maintenance of photoreceptors require precisely controlled transport of opsins and other phototransduction proteins from the site of synthesis in the inner segment to the outer segment.5 Circadian rhythm–associated daily shedding and renewal of approximately 10% of outer segments introduces additional high metabolic stress to retinal photoreceptors. Altered synthesis or disruption in the trafficking of phototransduction proteins (such as opsin) to the outer segment leads to photoreceptor degeneration.6–9

Retinal and macular degenerative diseases are a common cause of inherited and untreatable blindness.10 Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) constitutes a group of clinically and genetically heterogeneous retinal degeneration that afflicts one in 3500 individuals worldwide.11,12 X-linked RP (XLRP) is among the severe forms of RP, characterized by rod and cone photoreceptor dysfunction, generally in the second decade of life and vision loss in later stages.10,12,13 Although six genetic loci have been associated, mutations in two genes—RPGR and RP2—account for over 80% of XLRP cases.13–17

Approximately 15% of XLRP mutations are detected in the RP2 gene13,18 that encodes a protein of 350 amino acid residues.17,19 The crystal structure of the RP2 protein reveals an amino-terminal β-helix, which is structurally and functionally homologous to the tubulin-specific chaperone, cofactor C; most disease-causing missense mutations are present in this domain.20–22 RP2 is targeted predominantly to the plasma membrane20,23 and interacts with arginine adenosine-5′-diphosphoribosylation (ADP-ribosylation) factor-like 3 (ARL3),20,22 a microtubule-associated small GTPase23 that localizes to the connecting cilium of photoreceptors.22,24 RP2 exhibits ciliary transport in cultured cells and silencing of rp2 in zebrafish results in ciliary anomalies.25–27 Furthermore, RP2 localizes to the inner segment and connecting cilium of photoreceptors and may be involved in Golgi-mediated trafficking of proteins to the cilia.28 However, the effect of RP2 on photoreceptor development and maintenance in higher vertebrates is not clear.

Animal models (large and small) of retinal diseases have emerged as an essential tool for delineating the pathogenesis and function of genes associated with photoreceptor degeneration as well as to test gene- and cell-based treatment modalities.27,29–31 The RP2 gene was cloned in 199817; however, an animal model amenable to therapeutic approaches has not yet been developed. Here we describe the generation and characterization of an Rp2-mutant mouse model that represents the human disease condition. Our studies provide evidence for a role of RP2 in regulating protein trafficking in photoreceptors in vivo and should assist in designing rational therapeutic modalities.

Methods

Mouse Strains

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All mice were maintained in the same conditions of 12-hour light to 12-hour dark, with unrestricted access to food and water. Lighting conditions were kept constant in all cages with illumination of 10 to 15 lux at the level of the cages. The CAG-Cre mice have been previously described32 and were obtained from Jun-ichi Miyazaki, PhD (Osaka, Japan). The targeting construct carrying the loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the mouse Rp2 gene was generated at a commercial laboratory (Vega Biolab, Philadelphia, PA). Embryonic stem (ES) cells for targeting were derived from 129/SvEv mice. Chimeric mice were generated from targeted ES cells at the University of Michigan Transgenic Core Facility (Ann Arbor, MI). Germline transmission was validated by Southern Blotting and genotyping for the presence of loxP sites and a neomycin cassette. The mice were then crossed with FLPe recombinase-expressing mice (University of Michigan) to excise the neomycin cassette. Resulting mice were used to cross with the CAG-Cre transgenic strain, which expresses Cre in all cell types. The CAG-knockout (Rp2CKO) mice were genotyped by PCR using tail genomic DNA and primers spanning one of the loxP sites (for WT) or spanning the deleted region (for null). The Rp2CKO male and female mice were crossed with each other to remove the Cre transgene while carrying the genomic deletion of the Rp2 gene (Rp2null). The Rp2null line was maintained and used in the studies.

RT-PCR

Mouse retinal RNA was extracted using the TRIzol method (Life Technologies Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and used in reverse transcription and PCR analysis of the Rp2 gene to further validate the deletion. Primer sequences are as follows: Sense: 5′-GGG CTG CTG CTT CAC TAA; antisense: 5′-CAA GGC AAT CAC AGG ACC. An 889-bp product is shown in C57 mice, and a 223-bp band is shown in Rp2 mutant mice retina.

Immunoblotting

For immunoblotting, mouse (n = 3) eyes were enucleated and the retina was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored in −80°C. For protein extraction, the retinas were ultrasonicated in 250 μL of lysis buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.15% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktail). Protein concentration was measured by a DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Protein (50 μg) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membrane was blocked in 5% nonfat milk solution in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) followed by overnight incubation at 4°C in primary antibody. The membrane was rinsed in TBST buffer and incubated (2 hours at RT) in horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody in TBST (1:5000) and processed for chemiluminescence reaction.

Electroretinography (ERG)

ERG was performed using a commercial diagnostic technique (Espion; Diagnosys LLC, Cambridge, UK), as described.31 Briefly, mice were dark-adapted overnight and anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine 100 mg/kg and xylazine 10 mg/kg. Tropicamide (0.5%) was applied 10 minutes for pupil dilation. Animals were kept on a warming plate during the entire ERG procedure to maintain the body temperature at 37°C. The dark-adapted ERG protocol consisted of five steps with increasing stimulus strengths from 0.009 to 100 cd.s/m2, with a mixed white light (white 6500 K) produced by a Ganzfeld stimulator (ColorDome; Diagnosys LLC). All flashes were presented without background illumination and constant interstimulus intervals of 5 seconds for dim flashes and up to 30 seconds for bright flashes to maintain dark adaptation. Flash frequency was 0.07 Hz for bright flashes and up to 0.5 Hz for dim flashes. Band-pass filtering was applied from 0.312 to 300 Hz. Averages ranged from 10 trials for dim flashes to five trials for bright flashes. Light-adapted ERGs were recorded after light adaptation with a background illumination of 34 cd/m2 (white 6500 K) for 8 minutes. A stimulus strength of 10 cd.s/m2 was chosen for single flash. Twenty trials were averaged for single-flash responses.

Histology and Immunofluorescence

Mouse eyes were nucleated, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 12 hours at 4°C, dehydrated in serial gradients of ethanol, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (7 μm thick) containing the whole retina, including the optic disk, were cut along the vertical meridian of each eyeball and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For each section, digitized images of the retina were captured using a commercial imaging system (Leica DMI6000B; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The thickness of the outer nuclear layer was plotted versus distance (0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3.0 mm) from the optic nerve head (ONH), as described.33 Five mice from each group were included in this analysis. The thickness of Rp2null ONL was compared with that of same age Rp2flox by Student's t-test (Prism 5.0 software; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

For immunofluorescence staining, mouse eyes were enucleated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 12 hours at 4°C, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose overnight, frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (TissueTek; Sakura Finetek, Torrance CA), and cut into 20-μm cryostat sections. Sections or flat mounts of retinas were rinsed with PBS, permeabilized, and blocked for 1 hour with blocking solution containing 5% normal goat serum with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS in a humidifying chamber at RT. Primary antibodies were prepared in blocking solution and slides were further incubated overnight at 4°C. Sections were then washed three times with PBS and incubated for 1 hour with goat anti-rabbit (or mouse) Alexa Fluor 488 nm or 546 nm secondary antibody (1:500) at RT. Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies Corp.) was diluted with PBS to final 1 μg/mL and used to label the nuclei of the sections. The sections or flat-mount retinas were washed with deionized water and then mounted (Fluoromount; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) under glass coverslips and visualized using a scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP5 II laser; Leica Microsystems).

Antibodies

The mouse monoclonal RP2 antibody (against the N-terminal 34 amino acids; dilution of 1:50) and rabbit polyclonal RP2 antibody (dilution of 1:500) raised against full-length recombinant RP2 protein were generated and characterized previously.25,34 Mouse monoclonal anti-β-tubulin antibody was procured commercially (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and used at a dilution of 1:2000. All other primary antibodies used in this study are described in the Table.

Table.

List of Primary Antibodies Used in This Study

|

Antibodies |

Source |

Host |

Recognize |

Dilution |

| PNA (peanut agglutinin) | Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA | — | Cones | 1:1000 |

| Anti-M-opsin, anti-cone arrestin | Cheryl M. Craft41,42 | Rabbit | M-cone opsin, cone arrestin | 1:5000 |

| Anti-CTα, anti-CTγ | Vadim Y. Arshavsky, Duke University, Durham, NC | Rabbit | Cone transducin alpha subunit, cone transducin gamma subunit | 1:500 |

| Anti-Rhodopsin | Millipore, Billerica, MA | Mouse | Rhodopsin | 1:5000 |

| Anti-RTβ1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX | Rabbit | Rod transducin β1 subunit | 1:500 |

| Anti–Rod Arr | Vsevolod Gurevich, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN | Rabbit | Arrestin | 1:500 |

| Anti-ARL3 | Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL | Rabbit | ARL3 | 1:100 |

| Anti-NPHP3 | Sigma-Aldrich | Rabbit | NPHP3 | 1:50 |

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

For TEM, mouse eyes were enucleated and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 20 minutes at RT. The anterior portion was removed and eyecups were further fixed in the same fixative overnight at 4°C. After three washes with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, the eyecups were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide/0.1 M cacodylate buffer, dehydrated through an ethanol gradient to 100%, and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were cut with an ultramicrotome (Leica Reichart-Jung; Leica Microsystems) and stained with 2% uranyl acetate and 4% lead citrate. Specimens were visualized with a transmission electron microscope (Philips CM-10; Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands), coupled with a charge-coupled device digital camera (Gatan Erlangshen 785; Gatan, Inc., Warrendale, PA).

Results

Generation of Rp2flox Mouse

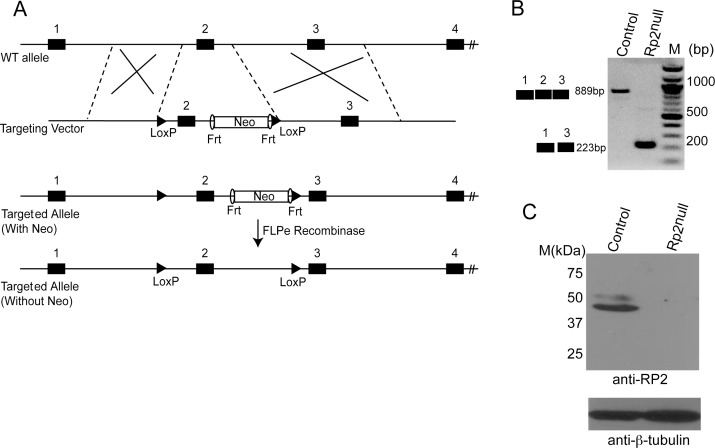

We generated a conditional Rp2 allele (Rp2flox) by introducing two loxP recombination sequences in the intronic regions flanking exon 2 of the mouse Rp2 gene (Fig. 1A). We selected exon 2 for our studies because the homologous exon 2 in humans is a mutational hotspot. Thus, it is hypothesized that deletion of this exon will represent the most commonly observed phenotype in a majority of patients. The targeting construct also contained a gene for neomycin resistance flanked by FRT recombinase sites. This construct was transfected into ES cells and multiple clones with targeted disruption of the Rp2 gene were selected. Southern blotting and sequencing of the genomic DNA confirmed site-specific recombination of the transgene (data not shown). Chimeras from two independent clones were crossed with FLPe-mice to excise the neomycin cassette. The resulting mice were crossed with C57BL/6 to produce homozygous Rp2flox/flox females and Rp2flox males (because males carry a single X-chromosome). All genotypes were obtained in expected Mendelian ratios.

Figure 1.

Generation of conditional allele of Rp2. (A) Schematic of the targeting construct and partial Rp2 genomic DNA showing location of the loxP sites, Frt recombinase, and selectable marker (neomycin [Neo]). The diagram is not drawn to scale. (B) RT-PCR analysis of retinal RNA could detect an expected size band of approximately 889 bp for wild-type (WT) allele in control and a shorter band of approximately 223 bp in Rp2null mice. (C) Immunoblot analysis of retinal protein extracts (50 μg each) using anti-RP2 antibody revealed an expected size band of approximately 40 kDa in control but not in the mutant retina. Immunoblotting using anti-β tubulin antibody (bottom) was used as loading control. Molecular mass marker (M) is shown in kDa.

Analysis of Rp2 Expression

We next performed breeding of the Rp2flox mice with transgenic mice in which the Cre transgene is under the control of cytomegalovirus immediate early enhancer chicken β-actin promoter (CAG-Cre; ubiquitous expression of Cre).32 Because the Cre transgene is expressed in the germline, we mated male (CAG-Cre Rp2flox/Y) and female (CAG-Cre Rp2flox/flox) Rp2 mutant mice to obtain a genotype of CAG-Cre negative Rp2−/− (Rp2null), which were selected for further studies. The use of Rp2null mice assisted in analyzing the phenotype associated with ablation of Rp2 with no effect from the Cre recombinase. However, in initial studies, we used CAG-Cre positive mice and found that the Cre protein had no effect on the development and function of photoreceptors (data not shown). We then went on to analyze the expression of RP2 in mutant retinas. As predicted, reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) assay using RNA from Rp2null mice revealed a deletion of exon 2 of the Rp2 gene (Fig. 1B). We further examined RP2 expression by immunoblot analysis and immunofluorescent staining. Using the anti-RP2 antibody34 we analyzed retinal extract of the Rp2null mice. Although the Rp2flox control mouse retina exhibited a band at the expected apparent molecular weight of 40 kDa, the Rp2null retina did not reveal an RP2-specific band (Fig. 1C). Immunoblotting with β-tubulin served as loading control. Similar results were obtained when an immunoblot was performed using a previously described rabbit polyclonal antibody.25 Immunofluorescence analysis using anti-RP2 antibody further confirmed the immunoblot data. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, we did not detect anti-RP2–specific staining in the Rp2null retinas as compared with control (Rp2flox) retinas.

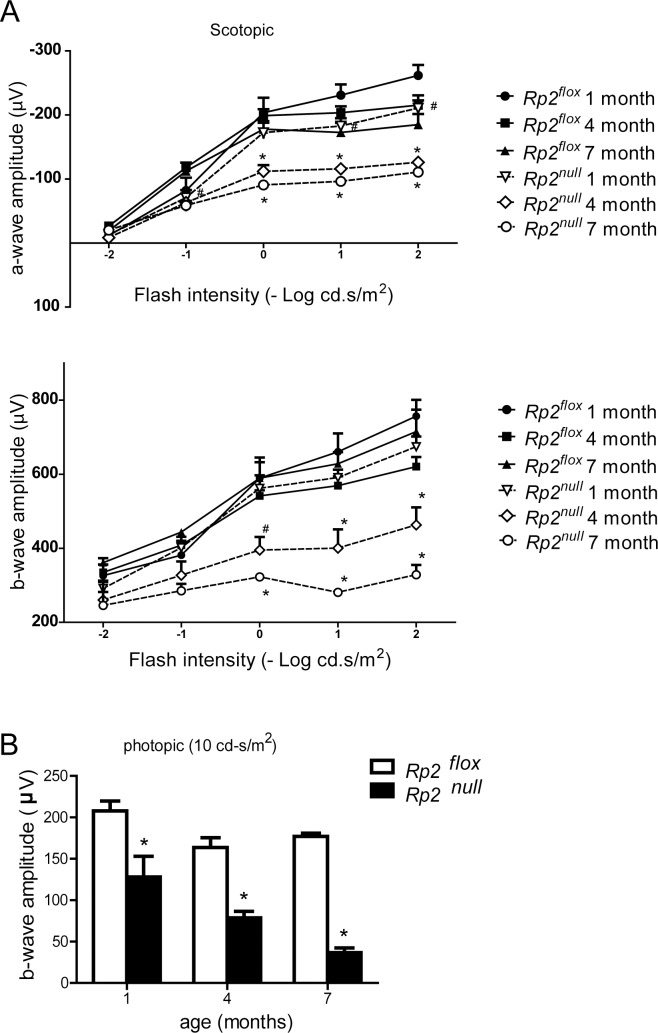

Retinal Pathology of Rp2null Mice

We next performed ERG to evaluate the effect of Rp2 deletion on photoreceptor function. The Rp2null mice exhibited significantly reduced scotopic a-wave (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 at 4 and 7 months, respectively) and b-wave (P < 0.01 at both 4 and 7 months of age) amplitudes as compared with controls (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. S2A). Under photopic conditions, considerable deterioration (≈40%) in b-wave amplitude was detected, starting as early as 1 month of age and declining progressively with age (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. S2B). We consistently detected a relatively more severe effect on photopic response than on the scotopic response.

Figure 2.

Photoreceptor dysfunction in Rp2null mice. Rod (scotopic; dark-adapted, [A] and cone (photopic; light-adapted, [B] function were assessed by ERG analysis at indicated ages (n = 5). All data were statistically analyzed using two-tailed Student's t-test and are shown as mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05 and *P < 0.01.

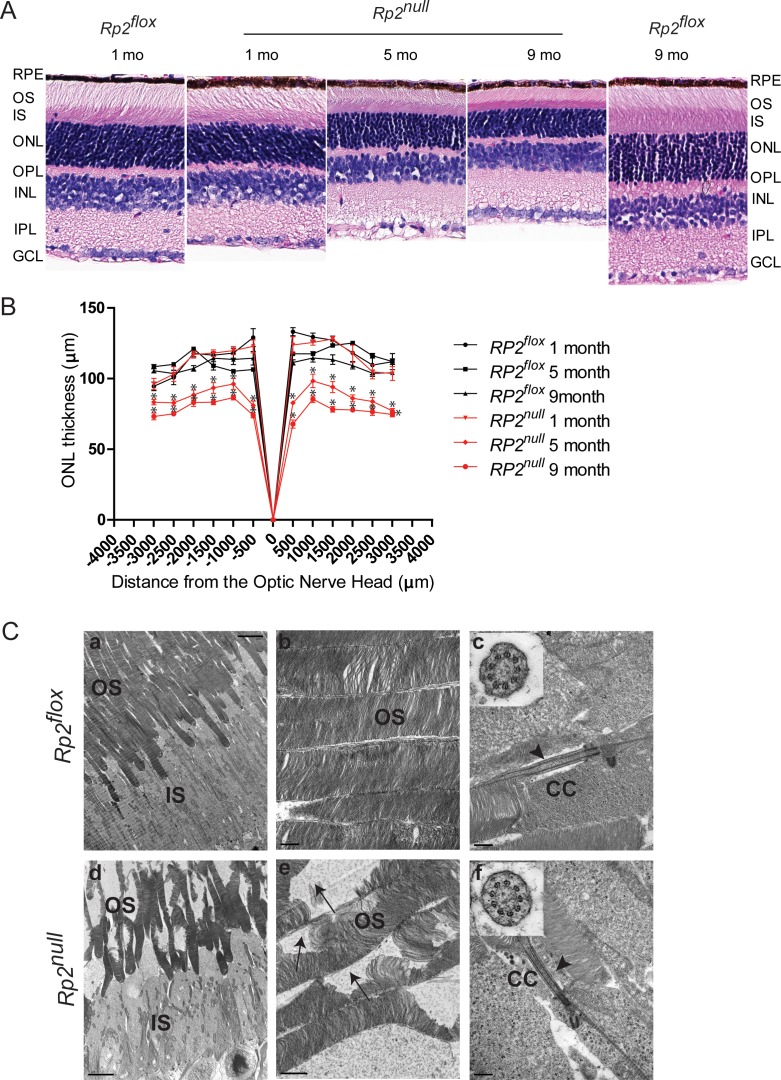

We then assessed the morphology of the retinas of Rp2null and age-matched Rp2flox mice. Analysis of both paraffin- and epoxy-embedded sections of retinas of Rp2null mice revealed a progressive decrease in the thickness of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) as compared with control mice (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. S3). Little to no effect was detected in other layers of the retina. We then assessed the thickness of the ONL using morphometric measurements. Although no statistically significant difference in ONL thickness was detected at 1 month of age in the Rp2null retinas as compared with controls, we found a 9% to 31% reduction in ONL thickness at 5 months and a 22% to 39% decrease in ONL thickness at 9 months of age. We then performed ultrastructural analysis of photoreceptors in mutant retinas. Although control retinas revealed well-maintained outer segments (Figs. 3Ca, 3Cb), Rp2null mice showed disorganized outer segment morphology (Figs. 3Cd, 3Ce). Nonetheless, mutant retinas displayed a normal 9 + 0 arrangement of microtubules in the connecting cilium of photoreceptors (Figs. 3Cc, 3Cf).

Figure 3.

Retinal histology and TEM of Rp2null retina. (A) Histologic analysis of paraffin sections of Rp2flox (control) or Rp2null mouse retina was performed at indicated ages. RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; OS, outer segment; IS, inner segment; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. (B) Morphometric analysis of ONL thickness of 1, 5, and 9 months Rp2flox and Rp2null retinas (n = 5). The ONL thickness was measured in μm along the vertical meridian at each defined distance from the optic nerve head. Data represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01. (C) TEM analysis of control (Rp2flox, top) and mutant (Rp2null, bottom) photoreceptors at 10 months of age show disorganized OS in the mutant retina. Insets (c, f) show cross-sectional view of the connecting cilium (CC) with 9 + 0 array of microtubules in both control and mutant mice. Arrows in (e) indicate degenerated OS discs in the mutant retina; arrowheads in (c, f) show normal morphology of the CC. Scale: (a, d) 5.0 μm; (b, c, f) 0.5 μm; (e): 1 μm.

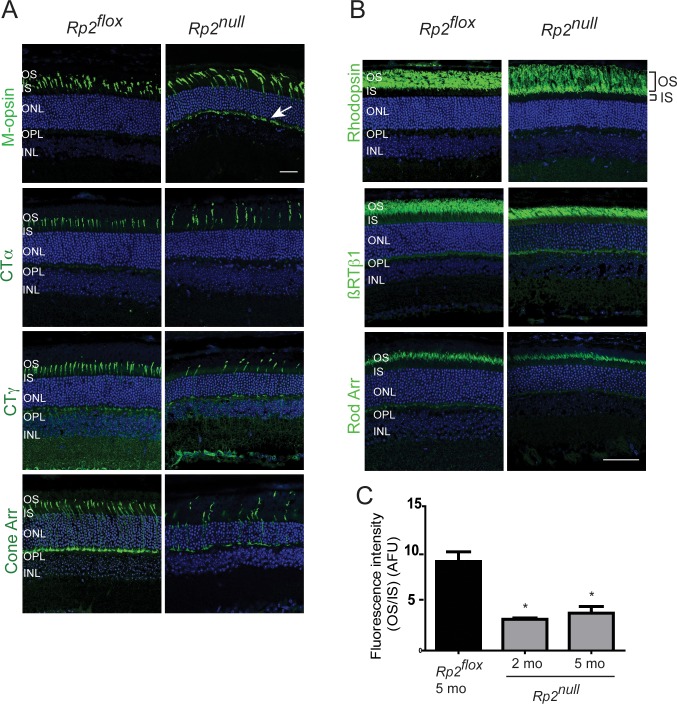

Next, we performed immunofluorescence analysis of the retina using antibodies against cone- and rod-specific proteins. Our analysis revealed that ablation of RP2 results in mislocalization of M-cone opsin in 1- and 2-month-old mice. As shown in Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure S4A, whereas M-opsin staining was detected predominantly in cone OS of control (Rp2flox) mice, it showed mislocalization to inner segment (IS) and outer nuclear layer (ONL) and outer plexiform layer in the Rp2null mouse retina. At late stages of disease (5 months of age), no effect on the trafficking of RP2-associated proteins ARL3 and nephrocystin-3 (NPHP3)20,35 (Supplementary Fig. S4B), or cone arrestin and α-, γ-subunits of cone transducin (CTα, CTγ) was observed in the mutant retinas, although cone photoreceptor loss could be detected (Fig. 4A). We also did not detect an appreciable change in rhodopsin or rod transducin β-1 (RTβ-1) and arrestin localization in the mutant retinas (Fig. 4B). However, quantification of rhodopsin, as determined by the ratio of immunofluorescence staining using rhodopsin 1D4 antibody in the OS to IS, revealed a 3- to 4-fold decrease in Rp2null mice (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescence analysis of Rp2null retinas. Retinal cryosections from 2 (M-opsin) or 5 months (other antibodies) old Rp2flox (control) or Rp2null mice were stained with cone (A) or rod (B) specific proteins, as indicated (green). CTα, cone transducin alpha subunit; CTγ, cone transducin gamma subunit; Cone Arr, cone arrestin; RTβ1, rod transducin beta1 subunit; Rod Arr, rod arrestin. Arrow (in [A]) shows the mislocalization of cone opsin to OPL. (C) Quantitative analysis of rhodopsin signal was performed by analyzing the ratio of fluorescence intensity of rhodopsin 1D4 staining in outer segment to that in the inner segment (OS/IS; the regions are shown in top panel in [B]) of Rp2flox (control) or Rp2null mice. Fluorescence intensity of rhodopsin was at a distance of 1.0 mm from the ONH. The OS/IS ratios from four sections of three mice in each group were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Means ± SEM (error bars) are shown. *P < 0.05. Data are represented in arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU).

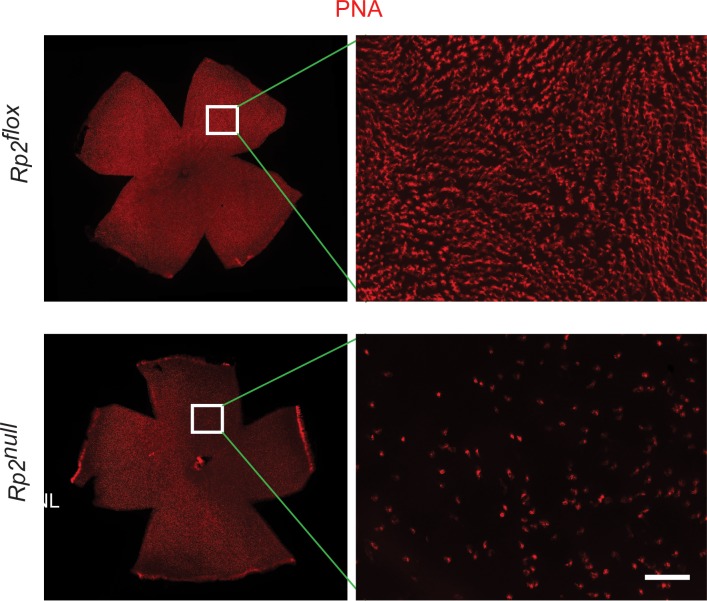

Because cone photoreceptors in mice exhibit a gradient distribution with blue (S) cones predominantly located in the inferior retina and red/green (M) cones in the superior retina, we used retinal sections and whole mounts to specifically delineate the effect of ablation of Rp2 on cone photoreceptors. Our analysis revealed a decline in cone photoreceptor staining and stout appearance of photoreceptors, as determined by staining with peanut agglutinin (PNA), in all retinal quadrants (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Staining of flat-mount retinas. Flat mount of retinas from Rp2flox (control) or Rp2null mice (10 months) were stained with PNA (red). Inset: The magnified image of the marked area. The mutant retina shows reduction of cones compared with Rp2flox. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Discussion

Using the Cre/loxP system, we have developed a mouse model carrying a deletion in the Rp2 gene. A prominent finding of our study is that ablation of Rp2 results in predominant mislocalization of cone opsins and severe cone dysfunction. Although compromised mislocalization of rhodopsin was not observed in rod photoreceptors, there was a decreased amount of rhodopsin in the OS. A similar effect was previously reported in two Rpgr-mutant mouse models.36,37 Notably, ablation of Rp2 results in an early mislocalization of cone opsin when there is little or no loss of cone photoreceptors. Such observations indicate that cone opsin mislocalization is either an early event or occurs concomitantly with cone loss during the pathogenesis of RP2 disease and suggest that cone opsins (specifically M opsin) use a distinct mechanism for transport to OS, which is regulated by RP2.

The observation that RP2 ablation has a differential effect on cones versus rods corroborates our earlier findings of effect of knock down of rp2 in zebrafish embryos.27 Moreover, a preferential dysfunction of cone photoreceptors is in agreement with the reported clinical findings of patients with RP2 mutations. In a large comprehensive clinical analysis of RP2 patients, we recently showed that a majority of RP2 patients exhibit early onset macular atrophy and cone photoreceptor dysfunction. Although rod photoreceptors exhibit dysfunction at an early stage, the progression of rod dysfunction and degeneration is relatively less severe as compared with cones.38 This finding suggests that RP2 knock out spares rod photoreceptors to some extent; however, at later stages, rod photoreceptor degeneration is also evident in the mutant mice.

RP2 does not seem to play a central role in the development of photoreceptor connecting cilium (CC) and OS. However, as photoreceptors mature, the insult due to compromised trafficking of opsins builds up in the cell and may lead to defective OS disc structure and improper maintenance of photoreceptors. RP2's interaction with ARL3 is proposed to regulate membrane trafficking of the Gβ1 subunit of transducin and NPHP3.35,39 However, in our analysis, the trafficking of Gβ1, ARL3, or NPHP3 was unaffected. We propose that in photoreceptors, RP2 may either exert relatively milder effects on the trafficking of these proteins or compensatory mechanisms may, in part, restore the trafficking of these proteins in the absence of RP2. Because photoreceptors undergo immense protein trafficking due to periodic shedding of distal outer segment discs and renewal at the base of the outer segment,40 it is conceivable that additional complementary mechanisms exist to retain the transport of regulatory proteins to the OS. Additional studies, such as the function of GAP activity of RP2 and its association with small GTPases in photoreceptors, are required to delineate the mechanism by which RP2 regulates protein trafficking in photoreceptors.

Overall, the Rp2null mouse provides a platform to assess the function of RP2 in photoreceptors and mode of photoreceptor dysfunction and degeneration due to RP2 mutations. Generation of the Rp2flox mouse serves as an excellent platform to delineate the role of RP2 in specific cell types, using appropriate Cre-transgenic lines. Such mouse models will not only allow thorough analysis of the function of RP2, they are also amenable to testing therapeutic modalities to treat associated disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Thom Saunders and the University of Michigan Transgenic Animal Core Facility for assistance in generating chimeric Rp2flox mice; Manisha Anand for help with retinal sectioning; Stephen Atkins, Shan Ma, and Garrett Grahek for assisting in genotyping and ERG analyses; Gregory Hendricks for TEM analysis; UMASS confocal core for fluorescence imaging; and Claudio Punzo for critical discussions about the manuscript.

Supported by National Eye Institute (NEI)/National Institutes of Health Grant EY022372; Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB); Worcester Foundation; Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)/FFB (CIHR RMF-92101); and the Intramural Research Program at NEI.

Disclosure: L. Li, None; N. Khan, None; T. Hurd, None; A.K. Ghosh, None; C. Cheng, None; R. Molday, None; J.R. Heckenlively, None; A. Swaroop, None; H. Khanna, None

References

- 1. Kennedy B, Malicki J. What drives cell morphogenesis: a look inside the vertebrate photoreceptor. Dev Dyn. 2009; 238: 2115–2138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wright AF, Chakarova CF, Abd El-Aziz MM, Bhattacharya SS. Photoreceptor degeneration: genetic and mechanistic dissection of a complex trait. Nat Rev Genet. 2010; 11: 273–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nathans J, Piantanida TP, Eddy RL, Shows TB, Hogness DS. Molecular genetics of inherited variation in human color vision. Science. 1986; 232: 203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neitz M, Neitz J, Jacobs GH. Spectral tuning of pigments underlying red-green color vision. Science. 1991; 252: 971–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deretic D. Post-Golgi trafficking of rhodopsin in retinal photoreceptors. Eye. 1998; 12: 526–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Besharse JC, Baker SA, Luby-Phelps K, Pazour GJ. Photoreceptor intersegmental transport and retinal degeneration: a conserved pathway common to motile and sensory cilia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003; 533: 157–164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Besharse JC, Hollyfield JG. Renewal of normal and degenerating photoreceptor outer segments in the Ozark cave salamander. J Exp Zool. 1976; 198: 287–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Young RW. The renewal of photoreceptor cell outer segments. J Cell Biol. 1967; 33: 61–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anand M, Khanna H. Ciliary transition zone (TZ) proteins RPGR and CEP290: role in photoreceptor cilia and degenerative diseases. Exp Opin Ther Targets. 2012; 16: 541–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heckenlively JR, Yoser SL, Friedman LH, Oversier JJ. Clinical findings and common symptoms in retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988; 105: 504–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haim M. Epidemiology of retinitis pigmentosa in Denmark. Acta Ophthalmol Scand Suppl. 2002; 233: 1–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Daiger SP, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS. Perspective on genes and mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007; 125: 151–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Breuer DK, Yashar BM, Filippova E, et al. A comprehensive mutation analysis of RP2 and RPGR in a North American cohort of families with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2002; 70: 1545–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Churchill JD, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, et al. Mutations in the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa genes RPGR and RP2 found in 8.5% of families with a provisional diagnosis of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 1411–1416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Webb TR, Parfitt DA, Gardner JC, et al. Deep intronic mutation in OFD1, identified by targeted genomic next-generation sequencing, causes a severe form of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP23). Hum Mol Genet. 2012; 21: 3647–3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shu X, Black GC, Rice JM, et al. RPGR mutation analysis and disease: an update. Hum Mutat. 2007; 28: 322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schwahn U, Lenzner S, Dong J, et al. Positional cloning of the gene for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa 2. Nat Genet. 1998; 19: 327–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Branham K, Othman M, Brumm M, et al. Mutations in RPGR and RP2 account for 15% of males with simplex retinal degenerative disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 8232–8237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chapple JP, Hardcastle AJ, Grayson C, Spackman LA, Willison KR, Cheetham ME. Mutations in the N-terminus of the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa protein RP2 interfere with the normal targeting of the protein to the plasma membrane. Hum Mol Genet. 2000; 9: 1919–1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuhnel K, Veltel S, Schlichting I, Wittinghofer A. Crystal structure of the human retinitis pigmentosa 2 protein and its interaction with Arl3. Structure. 2006; 14: 367–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bartolini F, Bhamidipati A, Thomas S, Schwahn U, Lewis SA, Cowan NJ. Functional overlap between retinitis pigmentosa 2 protein and the tubulin-specific chaperone cofactor C. J Biol Chem. 2002; 277: 14629–14634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grayson C, Bartolini F, Chapple JP, et al. Localization in the human retina of the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa protein RP2, its homologue cofactor C and the RP2 interacting protein Arl3. Hum Mol Genet. 2002; 11: 3065–3074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kahn RA, Volpicelli-Daley L, Bowzard B, et al. Arf family GTPases: roles in membrane traffic and microtubule dynamics. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005; 33: 1269–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schrick JJ, Vogel P, Abuin A, Hampton B, Rice DS. ADP-ribosylation factor-like 3 is involved in kidney and photoreceptor development. Am J Pathol. 2006; 168: 1288–1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hurd T, Zhou W, Jenkins P, et al. The retinitis pigmentosa protein RP2 interacts with polycystin 2 and regulates cilia-mediated vertebrate development. Hum Mol Genet. 2010; 19: 4330–4344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shu X, Zeng Z, Gautier P, et al. Knock-down of the zebrafish orthologue of the retinitis pigmentosa 2 (RP2) gene results in retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 2960–2966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patil SB, Hurd TW, Ghosh AK, Murga-Zamalloa CA, Khanna H. Functional analysis of retinitis pigmentosa 2 (RP2) protein reveals variable pathogenic potential of disease-associated missense variants. PLoS One. 2011; 6: e21379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Evans RJ, Schwarz N, Nagel-Wolfrum K, Wolfrum U, Hardcastle AJ, Cheetham ME. The retinitis pigmentosa protein RP2 links pericentriolar vesicle transport between the Golgi and the primary cilium. Hum Mol Genet. 2010; 19: 1358–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beltran A, Cideciyan AV, Lewin AS, et al. Gene therapy rescues photoreceptor blindness in dogs and paves the way for treating human X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012; 109: 2132–2137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang B, Hawes NL, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Heckenlively JR. Retinal degeneration mutants in the mouse. Vis Res. 2002; 42: 517–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chang B, Khanna H, Hawes N, et al. In-frame deletion in a novel centrosomal/ciliary protein CEP290/NPHP6 perturbs its interaction with RPGR and results in early-onset retinal degeneration in the rd16 mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2006; 15: 1847–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sakai K, Miyazaki J. A transgenic mouse line that retains Cre recombinase activity in mature oocytes irrespective of the cre transgene transmission. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997; 237: 318–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. LaVail MM, Matthes MT, Yasumura D, Steinberg RH. Variability in rate of cone degeneration in the retinal degeneration (rd/rd) mouse. Exp Eye Res. 1997; 65: 45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Holopainen JM, Cheng CL, Molday LL, et al. Interaction and localization of the retinitis pigmentosa protein RP2 and NSF in retinal photoreceptor cells. Biochemistry. 2010; 49: 7439–7447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wright KJ, Baye LM, Olivier-Mason A, et al. An ARL3-UNC119-RP2 GTPase cycle targets myristoylated NPHP3 to the primary cilium. Genes Dev. 2011; 25: 2347–2360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hong DH, Pawlyk BS, Shang J, Sandberg MA, Berson EL, Li T. A retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR)-deficient mouse model for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP3). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000; 97: 3649–3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thompson DA, Khan NW, Othman MI, et al. Rd9 is a naturally occurring mouse model of a common form of retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in RPGR-ORF15. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e35865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jayasundera T, Branham KE, Othman M, et al. RP2 phenotype and pathogenetic correlations in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010; 128: 915–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schwarz N, Novoselova TV, Wait R, Hardcastle AJ, Cheetham ME. The X-linked retinitis pigmentosa protein RP2 facilitates G protein traffic. Hum Mol Genet. 2012; 21: 863–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Besharse JC, Hollyfield JG. Turnover of mouse photoreceptor outer segments in constant light and darkness. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1979; 18: 1019–1024 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nikonov SS, Brown BM, Davis JA, et al. Mouse cones require an arrestin for normal inactivation of phototransduction. Neuron. 2008; 59: 462–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu X, Brown B, Li A, Mears AJ, Swaroop A, Craft CM. GRK1-dependent phosphorylation of S and M opsins and their binding to cone arrestin during cone phototransduction in the mouse retina. J Neurosci. 2003; 23: 6152–6160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.