Abstract

Infectious diseases such as HIV and Hepatitis B infection pose an omnipresent threat to global health. Reliable, fast, accurate and sensitive platforms that can be deployed at the point-of-care (POC) in multiple settings, such as airports and offices for detection of infectious pathogens are essential for the management of epidemics and possible biological attacks. To the best of our knowledge, no viral load technology adaptable to the POC settings exists today due to critical technical and biological challenges. Here, we present for the first time a broadly applicable technology for quantitative, nanoplasmonic-based intact virus detection at clinically relevant concentrations. The sensing platform is based on unique nanoplasmonic properties of nanoparticles utilizing immobilized antibodies to selectively capture rapidly evolving viral subtypes. We demonstrate the capture, detection and quantification of multiple HIV subtypes (A, B, C, D, E, G, and subtype panel) with high repeatability, sensitivity and specificity down to 98 ± 39 copies/mL (i.e., subtype D) using spiked whole blood samples and clinical discarded HIV-infected patient whole blood samples validated by the gold standard, i.e., RT-qPCR. This platform technology offers an assay time of 1 hour and 10 minutes (1 hour for capture, 10 minutes for detection and data analysis). The presented platform is also able to capture intact viruses at high efficiency using immuno-surface chemistry approaches directly from whole blood samples without any sample preprocessing steps such as spin-down or sorting. Evidence is presented showing the system to be accurate, repeatable and reliable. Additionally, the presented platform technology can be broadly adapted to detect other pathogens having reasonably well-described biomarkers by adapting the surface chemistry. Thus, this broadly applicable detection platform holds great promise to be implemented potentially at POC settings, hospital and primary care settings.

Keywords: Nanoplasmonic, HIV, AIDS, viral load, point-of-care

Detection of infectious agents (e.g., virus and bacteria) is critical for homeland security, public and military health. In recent years, infectious diseases, especially viral outbreaks such as HIV, have a tremendous global healthcare impact, since such viruses could rapidly evolve, spread and turn into pandemics. For instance, HIV/AIDS has had a devastating global impact causing over 25 million deaths.1, 2 The identification and control of forthcoming epidemics will be only be possible by developing reliable, accurate, and sensitive diagnostic technologies that have ability to be tailored to multiple settings. Detection of these viruses still poses significant biological and engineering challenges. Biological challenges arise due to the presence of multiple subtypes of viruses that makes it difficult to achieve repeatable and reliable capture efficiency from clinical specimens without demanding lengthy sample preparation steps. For instance, monitoring viral load for HIV at the point-of-care (POC) is still an unaddressed challenge. Traditional detection techniques such as culturing, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cannot be implemented at POC settings without well-equipped laboratories.3 Cell culture is a time-consuming, costly, and technically demanding method that requires skilled technicians. Adding to this problem, some viruses cannot be cultured.4 In ELISA-based methods, multiple sampling steps and reagents are required. Although PCR technology offers a versatile powerful detection platform in clinical samples,5, 6 for common viral subtypes, it requires parallel testing of external standards, complex multi-step manipulations such as labor-intensive sample preparation (plasma separation and RNA extraction), amplification (expensive reagents) and detection.3 Thus, simple, specific, accurate and reliable viral load assays are necessary to avoid further viral propagation and to initiate treatment.

Label-free biodetection platforms such as electrical, mechanical and optical mechanisms have been recently used for detection of infectious agents.7–9 These biosensing technologies offer multiple pathogen and disease detection applications ranging from laboratory research to medical diagnostics including drug development/treatment and engaging biologic threats for military applications. These platforms eliminate the requirements for fluorescent/radioactive labeling and/or enzymatic detection and enable easy-to-use, inexpensive POC tests. Additionally, silicon nanowires10, 11 and nanotubes12 have been used to detect biological materials such as viruses from human samples.13, 14 In fact, optical biosensing platforms hold great promise to monitor biomolecular binding signals and detect the relevant biological interactions in a small sample volume without any physical connection between the light source and the biosensing area. These aspects offer advantages in both sensitivity and detection limit.

Metal nanoparticles have been recently used in drug delivery15 and clinical diagnostics,16 and their nanoplasmonic properties present an advantage to monitor changes in light coupling on sensing surface. Association and/or dissociation of bioagents/molecules onto metal nanoparticles lead to changes in the wavelength. Each modification on the metal nanoparticle surface causes a peak shift at the maximum extinction wavelength and enables a broad window for spectral measurements with a high signal-to-noise ratio.17 Thus, these biosensing approaches have been used in various biochemical sensing platforms and spectroscopies allowing picomolar sensitivity to detect protein and nucleic acid interactions.18–20 However, there are a number of engineering and sampling challenges in both production and clinical testing of metal nanoparticle-based detection methods. First, typical chemical and physical modifications of nanoparticles (e.g., plasma treatment and exposure to highly acidic conditions) can lead to irreversible aggregation, resulting in degradation of optical characteristics.21 Also, existing nanoparticle-based pathogen detection methods have suffered from challenges associated with direct exposure to unprocessed whole blood, including non-specific binding and requirement for extensive sample preparation, thus reducing clinical relevance for POC applications. Currently, diagnostic tests (e.g., PCR and ELISA) require sample preprocessing including plasma separation to prevent inaccuracies in signal amplification and quantification steps. It is also a significant challenge to develop biosensing platforms to detect multiple subtypes/pathogens from clinical patient samples.

Although plasmon resonance principles have been utilized by others for protein and nucleic acid detection applications,22, 23 intact viral detection and viral load quantification has not been performed from unprocessed whole blood. Here, we demonstrate for the first time a reliable, label-free, fluorescence-free and repeatable HIV viral load quantification platform using a nanoplasmonic optical detection system for multiple viral subtypes and HIV-infected patient samples from unprocessed whole blood.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

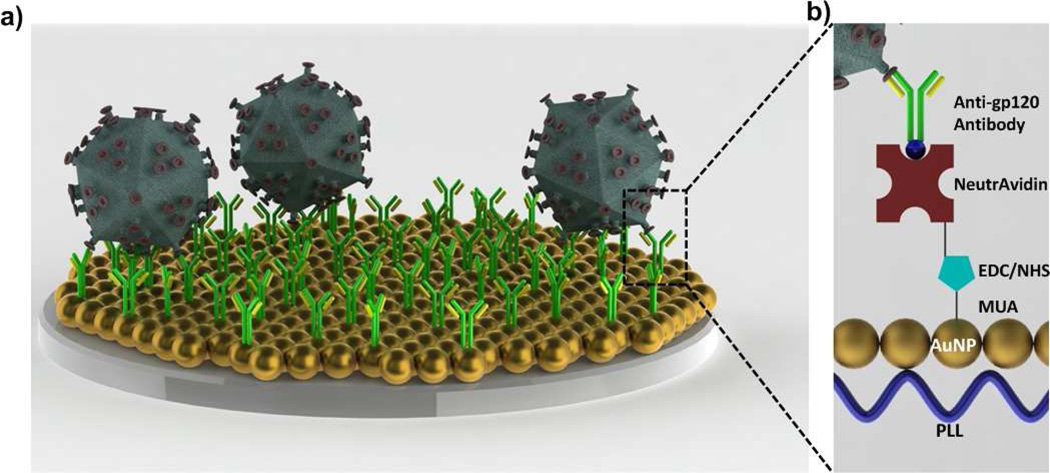

HIV is captured on the biosensing surface (Figure 1a), which is modified layer-by-layer for antibody immobilization (Figure 1b). To evaluate gold nanoparticle binding and seeding on polystyrene surface, a range of poly-l-lysine (PLL) concentrations (0.01 to 0.1 mg/mL) were evaluated and a linear concentration-dependent wavelength shift was observed (Figure S1). The individual wavelength peak of bare gold nanoparticles was observed as 518 nm. When PLL concentration was increased to 0.1 mg/mL, the wavelength peak was observed to be 550.2 ± 1.9 nm, due to an increase in the number of amine-terminated groups of the polymer (Figure S1a). Using a curve fitting method described in the Materials and Method section (spectral measurements and data analysis section), wavelengths corresponding to the extinction peaks were calculated from each wavelength spectrum. For the experiments, 0.05 mg/mL PLL concentration was chosen to avoid excessive dilution steps reducing possible variations in surface chemistry. This concentration resulted in a high extinction coefficient due to the highest gold nanoparticle binding onto the PLL treated surfaces (Figure S1b). Corresponding wavelength data for each PLL concentration and incubation time is presented in Table S1. Following each modification step, surfaces were rinsed with 1x PBS three times to minimize variations in the wavelength and intensity measurements. Metal nanoparticles varying in size, shape, and material present different maximum wavelength points.24 These properties allow to tune the nanoplasmonic wavelength point throughout the visible, near-infrared, and into the infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum offering flexibility.17 To avoid batch-to-batch variation25, 26 and to create a reproducible platform, we used a single batch of gold nanoparticle solution for this study.

FIGURE 1.

Nanoplasmonic viral load detection platform. a) HIV was captured on the antibody immobilized biosensing surface. b) To capture HIV on the biosensing surface, polystyrene surfaces were first modified by poly-l-lysine (PLL) generating amine groups. Then, gold nanoparticles (AuNP) were immobilized on the amine terminated surface. Layer-by-layer modifications were performed by 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA), N-Ethyl-N’-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (NHS) coupling, NeutrAvidin and biotinylated anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody. To prevent nonspecific binding, bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a blocking agent. At each surface modification and after HIV capture step, spectral analysis was monitored, and the peak shifts at the maximum extinction wavelength were recorded.

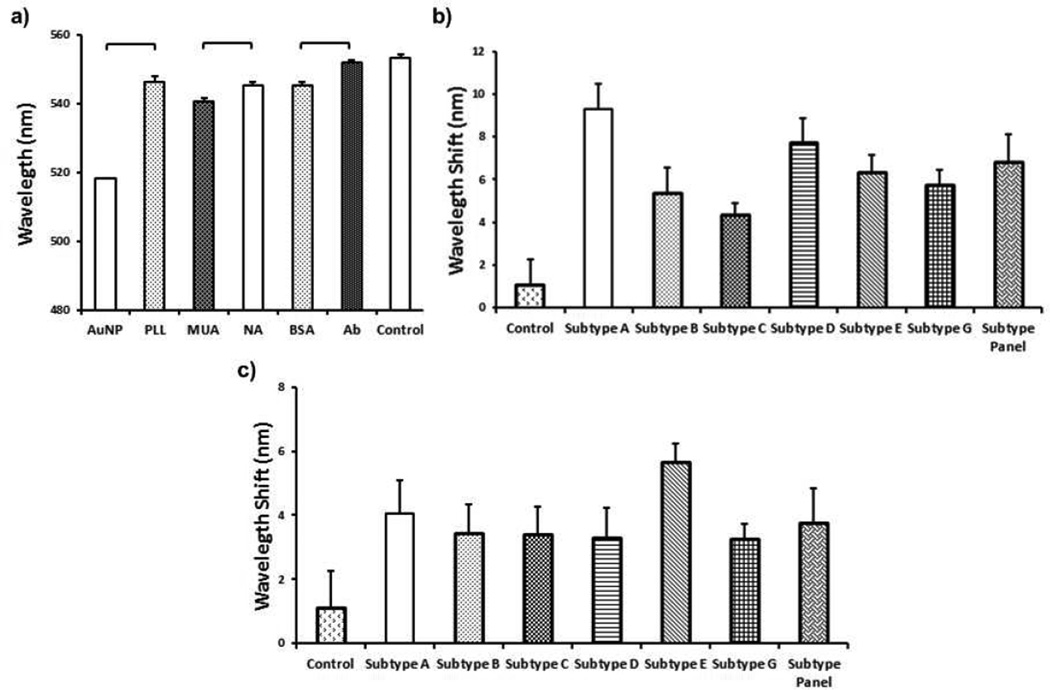

To evaluate the surface chemistry, a control group of unmodified 10 nm diameter gold nanoparticles were utilized. An individual wavelength peak of gold nanoparticles was reproducibly observed at 518 nm (n=6, p<0.05) (Figure 2a). The corresponding peak shift after PLL modification was measured as 546.7 ± 1.8 nm, which represents a statistically significant (n=6, p<0.05) difference from the gold-coated surface (Figure 2a). Following gold nanoparticle coating of the PLL modified surface, 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA) was self-assembled as a monolayer onto the gold nanoparticle layer and generated carboxyl groups on the surface of the gold nanoparticle layer.

FIGURE 2.

Layer-by-layer surface modifications, and the corresponding wavelengths and wavelength peak shifts. Each modification was monitored and peak shift at the maximum wavelength was recorded using curve fitting analysis method. a) Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) showed a stable peak at 518 nm. Gold nanoparticle binding on 0.05 mg/mL of poly-l-lysine (PLL) modified surface led to a statistically significant peak shift from 518 nm to 546.4 ± 1.6 nm (n=6, p<0.05). 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA), NeutrAvidin (NA), bovine serum albumin (BSA) and biotinylated anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody collectively shifted the maximum wavelength to 551.9 ± 0.5 nm (n=6–216, p<0.05). Addition of control sample (unprocessed whole blood without viruses) did not result in a statistically significant peak shift (1.2 ± 1.1 nm) (n=6–216, p>0.05). Individual p-values for statistical analyses are presented in Tables S2. b) Difference between control (i.e., whole blood without HIV) and HIV spiked whole blood samples was evaluated. Whole blood was spiked with HIV at (6.5 ± 0.6) × 105 copies/mL, (8.3 ± 1.3) × 105 copies/mL, (1.3 ± 0.2) × 106 copies/mL, (3.8 ± 1.2) × 106 copies/mL, (1.3 ± 0.2) × 106 copies/mL, (1.1 ± 0.3) × 106 copies/mL and (2.9 ± 0.5) × 106 copies/mL for subtypes A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel, respectively. We observed statistically significant wavelength shifts of 9.3 ± 1.2 nm, 5.4 ± 1.1 nm, 4.4 ± 0.5 nm, 7.8 ± 1.1 nm, 6.3 ± 0.8 nm, 5.8 ± 0.7 nm and 6.9 ± 1.2 nm for subtypes A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel, respectively (n=6, p<0.05). Individual p-values for statistical analyses are presented in Tables S3. c) Limit-of-detection for each subtype indicating a statistically significant peak shift compared to the control (i.e., whole blood without HIV) was observed as 1,346 ± 257 copies/mL for HIV subtype A, 10,609 ± 2,744 copies/mL for HIV subtype B, 14,942 ± 1,366 copies/mL for HIV subtype C, 98 ± 39 copies/mL for HIV subtype D, 120,159 ± 15,368 copies/mL for HIV subtype E, 404 ± 54 copies/mL for HIV subtype G, and 661 ± 207 copies/mL for HIV subtype panel (Statistical assessment on the results was performed using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance followed by Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance threshold was set at 0.05, p<0.05. Brackets connecting individual groups indicating a statistically significant peak shift. The data for wavelength measurements were presented as wavelength measurements ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Error bars represent SEM.

Antibodies immobilized with a favorable orientation using NeutrAvidin have a higher capture efficiency towards bioagents than those immobilized by physical absorption and chemical binding of antibodies onto a surface.27 To immobilize biotinylated antibodies for HIV capture, surfaces were modified with NeutrAvidin. At the end of NeutrAvidin modification, a statistically significant wavelength peak shift was observed as 4.4 ± 1.1 nm with respect to the MUA step (n=6, p<0.05) (Figure 2a). To prevent nonspecific binding, 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution was used as a blocking agent. This blocking agent did not result in a statistically significant peak shift (n=6, p>0.05) (Figure 2a). Then, biotinylated anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody was incubated on the NeutrAvidin coated surface. We observed that biotinylated anti-gp120 antibody resulted in a statistically significant wavelength peak shift compared to the BSA step (6.8 ± 0.5 nm) (n=216, p<0.05) (Figure 2a).

To evaluate the repeatability of the surface chemistry, we defined the following relation:

| (1) |

where WS is wavelength shift, and SEM is the standard error of the mean. In the literature, repeatability is defined as closeness of the agreement between the results of the measurements in the same experiment carried out under the same conditions.28 Here, repeatability parameter was described as the percent variation in wavelength shift measurements for the surface modifications. The parameter was evaluated for both wavelength and extinction intensity measurements of each surface modification (Figure S2). Overall, the repeatability parameter was observed to be 55 – 98% and 85 – 99% for wavelength and extinction intensity measurements, respectively (Figure S2). These results indicated that the surface chemistry is repeatable enabling a feasible nanoplasmonic platform (Figure S2).

To evaluate potential drift and background signal noise due to potential chemical/physical changes or nonspecific binding on the surface, we assessed the system using whole blood, HIV spiked whole blood, and clinical HIV-infected patient samples. For control measurements, biosensing surfaces functionalized with polyclonal antibody were used. Addition of unprocessed whole blood without viruses did not result in a statistically significant peak shift (1.2 ± 1.1 nm) (n=6–216, p>0.05) (Figures 2a and 2b). The statistical analysis results and p-values obtained using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance followed by Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction were also presented in Table S2. Blood samples were spiked with (6.5 ± 0.6) × 105 copies/mL, (8.3 ± 1.3) × 105 copies/mL, (1.3 ± 0.2) × 106 copies/mL, (3.8 ± 1.2) × 106 copies/mL, (1.3 ± 0.2) × 106 copies/mL, (1.1 ± 0.3) × 106 copies/mL, and (2.9 ± 0.5) × 106 copies/mL with subtypes A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel, respectively. These samples resulted in statistically significant wavelength shifts of 9.3 ± 1.2 nm, 5.4 ± 1.1 nm, 4.4 ± 0.5 nm, 7.8 ± 1.1 nm, 6.3 ± 0.8 nm, 5.8 ± 0.7 nm and 6.9 ± 1.2 nm for subtypes A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel, respectively (n=6, p<0.05) (Figure 2b). Thus, we observed that anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody reproducibly and repeatably captured multiple virus subtypes (A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel) using this platform (Figure 2b). The statistical analysis results and p-values obtained using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance followed by Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction were also presented in Table S3. To evaluate limit of detection, we compared wavelength shift values of control (whole blood without HIV) and low HIV concentrations for different subtypes. Limit of detection was observed, to be 1,346 ± 257 copies/mL for HIV subtype A; 10,609 ± 2,744 copies/mL for HIV subtype B; 14,942 ± 1,366 copies/mL for HIV subtype C; 98 ± 39 copies/mL for HIV subtype D; 120,159 ± 15,368 copies/mL for HIV subtype E; 404 ± 54 copies/mL for HIV subtype G; and 661 ± 207 copies/mL for HIV subtype panel. Thus, the capture of various subtypes using anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody presented different limit-of-detection values (Figure 2c). The limit of detection could be improved by collecting data from a larger active capture and detection area or by increasing the sample volume. We presented the original experimental data and the corresponding curve fits in Figure S3 a–g. After introducing HIV to the nanoplasmonic platform, a representative observed wavelength and extinction intensity shift was presented in Figure S3 h.

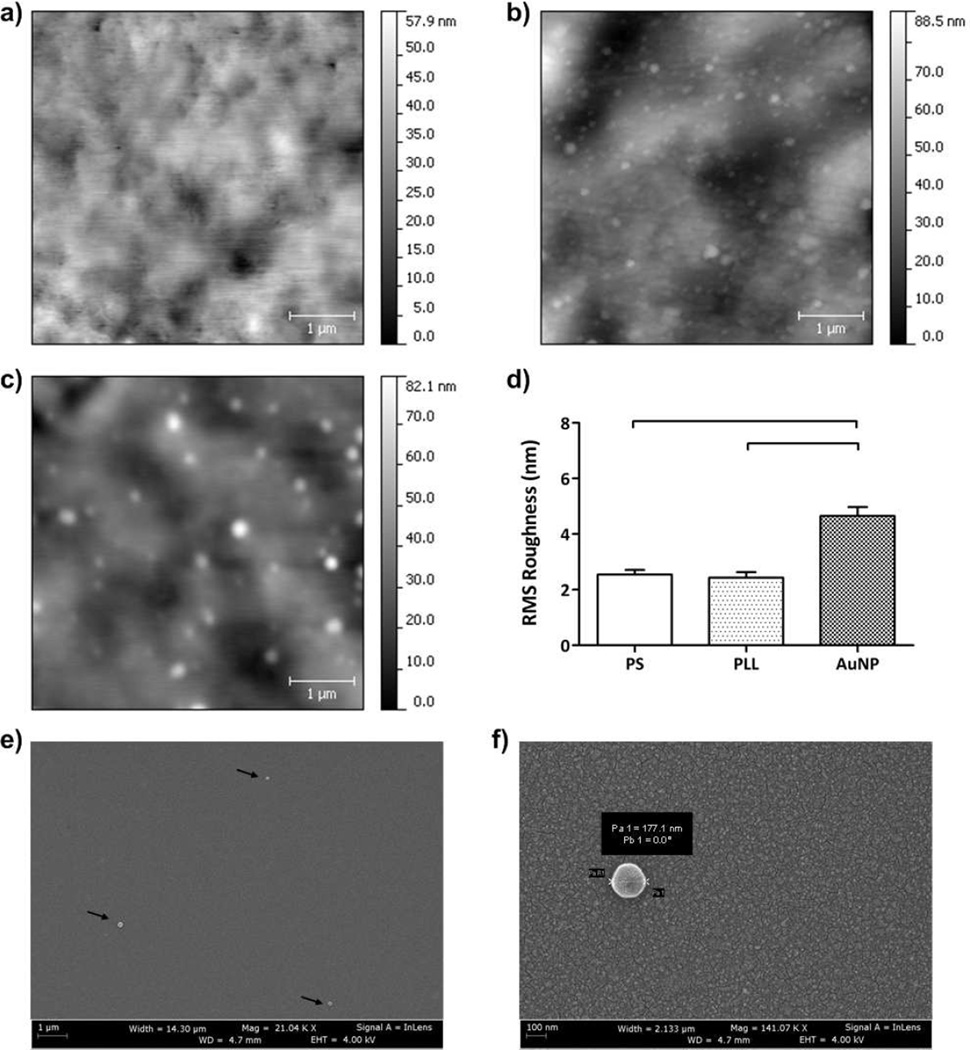

We characterized the polystyrene surfaces using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for each surface modification step. For unmodified polystyrene surface, we observed a roughness of 2.5 ± 0.2 nm expressed as root mean square (RMS) measurements ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (Figures 3a and 3d). After modification of the surface with 0.05 mg/mL of PLL, RMS roughness was observed to be 2.4 ± 0.2 nm (Figures 3b and 3d). Gold nanoparticle immobilization on PLL modified surfaces gave a RMS roughness of 4.7 ± 0.3 nm (Figures 3c and 3d). We observed that there was no statistically significant difference between unmodified and PLL-modified polystyrene surfaces (n=8, p>0.05) (Figure 3d). We also observed that there was a significant difference between gold nanoparticle immobilization and unmodified polystyrene surfaces (n=8, p<0.05) (Figure 3d). Hence, gold nanoparticle immobilized surfaces led to significantly greater changes in RMS roughness compared to PLL modified surfaces (n=8, p<0.05). The statistical analysis results and p-values obtained using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance followed by the Mann-Whitney U test with the Bonferroni correction were presented in Table S4. To quantitatively evaluate the coating uniformity and density of gold nanoparticles, AFM analysis was performed on different areas of the modified surfaces. To assess the coating uniformity of the gold nanoparticles, we followed the previously reported method using the public domain NIH ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).29, 30 The images (5 µm × 5 □ µm) were first converted into 8-bit images using the public domain NIH ImageJ software (version 1.46r). Then, the thresholds were adjusted between 50 a.u. and 200 a.u. to estimate the gold nanoparticle coating. The uniformity was calculated by utilizing this threshold range, and the immobilization of gold nanoparticles presented ~83% uniform coating on the biosensing surface (n=8). Thus, a uniform and densely coated nanoplasmonic platform was produced. The modified surfaces were incubated at 4°C to prevent the evaporation. Thus, we did not observe “coffee ring” effects during gold nanoparticle incubation and surface chemistry. Additionally, we showed that HIV particles were captured on the surface using SEM imaging (Figures 3e and 3f). SEM images at multiple locations on the chip did not show any aggregation of captured viruses. Coating uniformity and density of gold nanoparticles on PLL modified surfaces were also qualitatively evaluated using SEM (Figures 3e and 3f). SEM experiments qualitatively demonstrated that gold nanoparticles were uniformly distributed on the surface as observed in AFM analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Surface characterization of polystyrene (PS) substrates before and after surface modification steps using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). Five random 5µm × 5µm surface areas for each sample group were evaluated. a) PS substrates without surface modification are shown. b) PS substrates after 0.05 mg/mL of PLL treatment are presented. c) Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were immobilized on poly-l-lysine (PLL) treated surfaces. After AuNP immobilization, nanoparticles were observed on surfaces. d) Root mean square (RMS) roughness of surfaces was evaluated and significant difference was observed when AuNPs were immobilized onto the surfaces compared to PS substrates with and without PLL (n=8, p<0.05). e) Scanning electron microscope image (140 µm2) of the captured intact viruses (100 µL at 106 copies/mL concentration) was presented on the antibody immobilized biosensing surface (4 × 106 µm2). From these numbers, on average 3 to 4 viruses are expected to be captured on the SEM image area as observed experimentally. f) Higher magnification of a captured HIV was imaged and virus diameter was measured as 177.1 nm. SEM image was taken at 4.7 mm working distance and 4.00 kV accelerating voltage (Statistical analysis was performed using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance followed by Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons and statistical significance threshold was set at 0.05, p<0.05. Individual p-values for statistical analyses are presented in Table S4. Brackets connecting individual groups indicate statistically significant peak shift. Error bars represent standard error of the mean).

To evaluate the number of gold nanoparticles on the active area interacting with virus particles, we defined the following equation:

| (2) |

where N is the number of gold nanoparticles on active area, V is the volume of virus solution (mL), C is the number of copies of viruses per mL, Ab is the optical beam area (mm2), A is whole surface area (µm2), P is the capture efficiency of viruses, and R2/r2 is the surface area ratios of a virus and gold nanoparticle.

Our earlier results demonstrated 69.7 to 78.3% capture efficiency for HIV spiked in whole blood samples using anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody on glass surfaces.27 Based on these results, here we assumed 70% capture efficiency of viruses in multi-well plates (Supporting Information: Theoretical modeling of capture efficiency section). We plotted the number of gold nanoparticles roughly estimated to be in contact with viruses in an active area (Figure S4). Nanoplasmonic platforms have been used to detect several protein and nucleic acid interactions down to picomolar sensitivity.18–20 In the literature, less than 1 pM of Streptavidin molecules (Molecular Weight: 57–60 kDa) resulted in a ~27 nm wavelength shift, and the limit of detection of this system was also presented as <25 Streptavidin molecules/nanoparticle (~100 nm diameter).31, 32 Here, we captured intact viruses using the gp120 receptor proteins (Molecular Weight: 120 kDa), which are located on the HIV surface.

Additionally, the nanoplasmonic extinction spectra of a nanoparticle can be affected by neighboring nanoparticles.33 This property has been used in measuring the length of flexible single-stranded DNA strands positioned in between nanoparticle pairs.34 It has been shown that short inter-particle distances can amplify the local electromagnetic fields causing an increased localized surface plasmon signal.35, 36 These enhanced fields (or hot-spots) have been recently used in nanoplasmonic detection of Adenovirus particles.37 The exact nature of this enhancement is reported to be a function of the nanoparticle arrangement on the surface and the effective refractive index distribution over nanoparticles.37

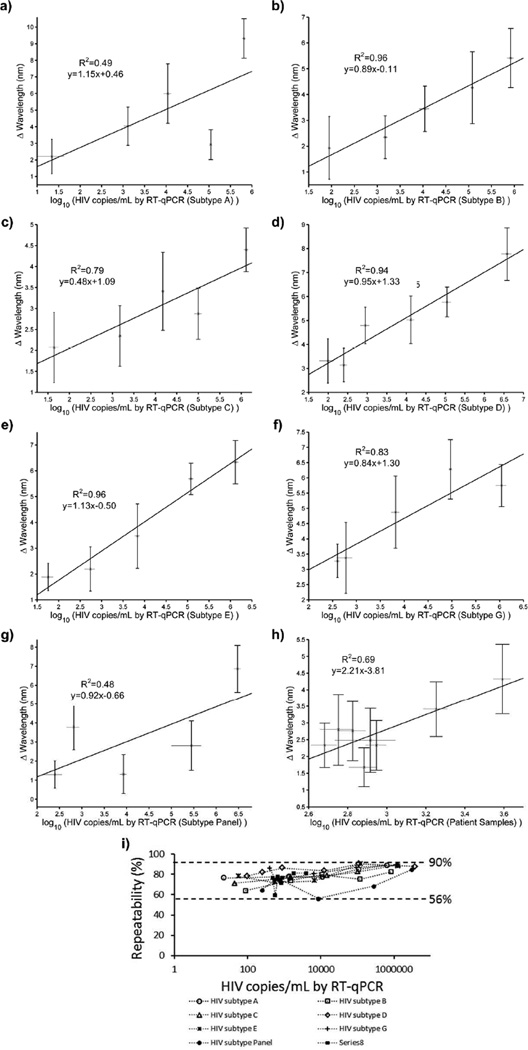

To evaluate the limit of detection and broad applicability of the nanoplasmonic detection platform in biologically relevant systems, we analyzed various concentrations of multiple subtypes spiked in whole blood and phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The biological environment of viruses provides several potential challenging factors including excessive level of albumin, casein, immunoglobulin, and other proteins, which might cause blocking of the antigen-antibody interaction and nonspecific binding. This could increase nonspecific background signals and interfere with the system performance. Hence, directly detecting viruses from biological samples is a crucial test to evaluate the biosensing performance and robustness of the system. We evaluated multiple HIV subtypes, i.e., A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel, spiked in whole blood. A Fourier type curve fitting analysis described in the Materials and Methods section (spectral measurements and data analysis section) was performed for each recorded spectra (i.e., HIV data and the corresponding reference curve) to extract the wavelength shifts of HIV subtypes (A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel) spiked in whole blood. In particular, blood samples were spiked with (6.5 ± 0.6) × 105 copies/mL, (8.3 ± 1.3) × 105 copies/mL, (1.3 ± 0.2) × 106 copies/mL, (3.8 ± 1.2) × 106 copies/mL, (1.3 ± 0.2) × 106 copies/mL, (1.1 ± 0.3) × 106 copies/mL, and (2.9 ± 0.5) × 106 copies/mL with subtypes A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel, respectively. These samples resulted in wavelength shifts of 9.3 ± 1.2 nm, 5.4 ± 1.1 nm, 4.4 ± 0.5 nm, 7.8 ± 1.1 nm, 6.3 ± 0.8 nm, 5.8 ± 0.7 nm and 6.9 ± 1.2 nm for subtypes A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel, respectively (Figure 4a–g). We also validated HIV viral load using 8 HIV-infected anonymous discarded patient whole blood samples using the nanoplasmonic platform. In the presence of discarded patient samples, the highest peak shift was observed to be 4.3 ± 1.0 nm at 3910 ± 400 copies/mL (Figure 4h). The peak shift for 481 ± 73 copies/mL HIV viral load was 2.3 ± 0.7 nm (Figure 4h). In addition to whole blood testing, we evaluated an HIV subtype panel suspension in PBS (Figure S5). We used two data analysis approaches to evaluate the wavelength shift data using (i) curve fitting and (ii) experimental data maximum method, described in the Materials and Methods (spectral measurements and data analysis). The curve fitting analysis results are presented in Figure 4 and the experimental data maximum method results are presented in Figure S6. The two methods gave comparable results. The lower virus concentrations resulted in small wavelength shifts and full spectra is taken into account with the curve fitting method to evaluate these small shifts. We observed that the curve fitting method is better suited for the analysis of smaller wavelength shifts. We analyzed a total of 216 curves for antibody references and 216 curves for their corresponding HIV spiked whole blood samples. Each peak was subtracted from its own reference to obtain a shift. 9 wells out of the 216 reference measurements were more than 1 standard error of the mean (SEM) away from the mean before a sample was introduced for testing. Also, the measurements with these wells gave negative shift results indicating that these wells had variations during preparation steps, and thus, they were not included in the analysis. Four other wells gave negative results below −1 nm when the HIV-spiked whole blood extinction peaks were subtracted from their antibody reference. These wells were not included in the analysis, since these results are inconclusive potentially due to the variations in surface chemistry. Additionally, one well among the 50 copies/mL and 100 copies/mL wells was excluded, since it gave a shift that is larger than that of the same subtype at the highest concentration plus its SEM. Additionally, we observed 10 shifts ranging between 0 and −0.5 nm, which are below the instrumental step size (1 nm), so these values are equivalent to a no-shift. No-shifts may be due to the fact that no viruses were captured in the active area. These data points were included in the analysis to reflect the statistical nature of the capture event as earlier outlined in the capture efficiency calculations (Supporting Information: Theoretical modeling of capture efficiency).

FIGURE 4.

Validation with HIV spiked in whole blood and HIV-infected patient samples using experimental data curve fitting method. Fourier type curve fitting analysis was performed for each recorded spectra to extract the extinction peak of HIV subtypes spiked in whole blood and panel sample (n=4–6, error bars represent standard error of the mean). The results correlated well with the experimental data maximum method presented in Figure S6. The viral load values were obtained by RT-qPCR and repeated at least 3 times each sample for each concentration. a) HIV subtype A in whole blood led to 9.3 ± 1.2 nm wavelength shift at (6.5 ± 0.6) × 105 copies/mL. b) (8.3 ± 1.3) × 105 copies/mL of HIV subtype B spiked in whole blood samples led to a wavelength shift of 5.4 ± 1.1 nm. c) For sampling with HIV subtype C in whole blood, (1.3 ± 0.2) × 106 copies/mL concentration was evaluated and the peak shift was observed to be 4.4 ± 0.5 nm. d) (3.8 ± 1.2) × 106 copies/mL of HIV subtype D in whole blood sample resulted a wavelength shift of 7.8 ± 1.1 nm e) HIV subtype E in whole blood was evaluated and observed that there was 6.3 ± 0.8 nm wavelength shift at (1.3 ± 0.2) × 106 copies/mL. f) For sampling with HIV subtype G in whole blood, (1.1 ± 0.3) × 106 copies/mL concentration was evaluated and the peak shift was observed to be 5.8 ± 0.7 nm. g) HIV subtype panel in whole blood was evaluated and observed that there was 6.9 ± 1.2 nm wavelength shift at (2.9 ± 0.5) × 106 copies/mL. h) Discarded HIV patient samples in whole blood were evaluated and observed that there was 4.3 ± 1.0 nm wavelength shift at 3910 ± 400 copies/mL. The peak shift decreased to 2.3 ± 0.7 nm when the lowest concentration (481 ± 73 copies/mL) sample was evaluated. i) Repeatability parameter was evaluated for the wavelength shifts for multiple HIV subtypes at various concentrations. Overall, the repeatability parameter was observed to be 56 – 90% for a broad range of concentrations for multiple HIV spiked and discarded HIV patient samples. The data for wavelength measurements were presented as wavelength measurements ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n=4–6, error bars represent SEM). The viral load values were obtained by RT-qPCR and repeated at least 3 times each sample for each concentration.

To evaluate the repeatability of the biosensing platform technology, we defined an equation, which was presented in Supporting Information (Repeatability of the biosensing platform). Here, the repeatability parameter was described as the percent variation in wavelength shift measurements for the same virus concentration. The parameter was evaluated for each HIV subtype, and presented at varying spiked sample concentrations (Figure 4i). Overall, the repeatability parameter was observed to be 56 – 90% for a broad range of concentrations for multiple HIV subtypes. These results indicated that the nanoplasmonic biosensing platform is reliable, accurate, repeatable and feasible (Figure 4i). These results also demonstrated that the system performance showed comparable repeatability values for multiple HIV subtypes in whole blood (Figures 4i).

In addition to the wavelength shift, the nanoplasmonic system can measure extinction intensity variations caused by HIV capture events. These capture events cause both wavelength shift and extinction intensity variation, and results were acquired both as wavelength shifts and extinction intensity variations. We evaluated the extinction intensity variations (Figure S7) for the same set of experiments, as in the wavelength shift plots of Figure S6.

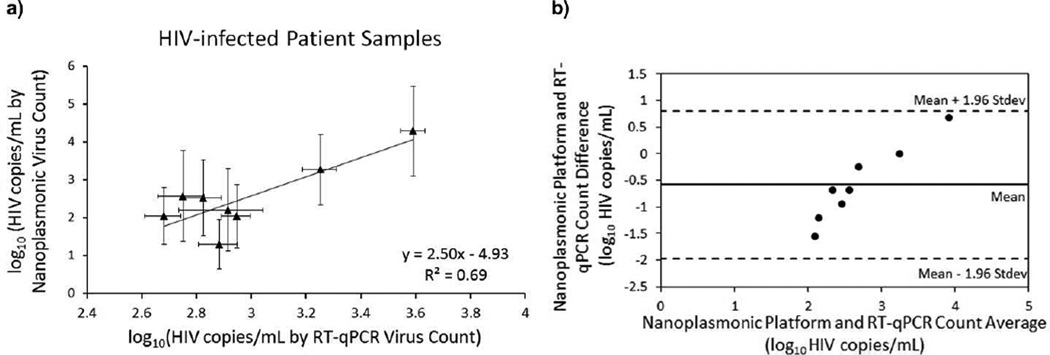

The nanoplasmonic platform measures the signal shift caused by viruses captured on a gold nanoparticle coated surface. The concentration of viruses was quantified by RT-qPCR, which is a bulk detection technique. The overall wavelength shifts resulting from the captured viruses were calculated and presented in the plots. We generated a standard curve by performing a least squares fit to the combined data of all HIV subtypes spiked in whole blood. Then, the bulk HIV concentrations were quantified by translating the shifts using the standard curve that translate the surface detection to bulk detection (Figure 5). In this work, we focused on the global shifts to quantify the bulk concentrations, which were obtained by RT-qPCR. To evaluate quantitative detection, we first obtained the standard curve with HIV spiked whole blood samples, using the wavelength shifts analyzed by curve fitting method, and the HIV viral load obtained by RT-qPCR. After the standard curve is obtained, we presented quantitative detection results using the biosensing platform with HIV-infected patient samples (Figure 5a and Table S6). Nanoplasmonic platform presented a viral load ranging from (1.3 ± 0.7) log10 copies/mL to (4.3 ± 1.2) log10 copies/mL in patient samples. RT-qPCR count presented a viral load ranging from (2.7 ± 0.1) log10 copies/mL to (3.6 ± 0.1) log10 copies/mL in patient samples. These results were presented in Table S6 and were evaluated using Bland-Altman analysis as presented in Figure 5b. Bland-Altman Analysis for the nanoplasmonic platform and RT-qPCR showed that there was no evidence for a systematic bias for HIV viral load from HIV-infected patient blood samples. Additionally, we analyzed extinction intensity measurements of patient data using the curve fitting approach, and presented results in Figure S8a. Nanoplasmonic platform presented a viral load ranging from (2.2 ± 0.9) log10 copies/mL to (3.7 ± 0.5) log10 copies/mL in patient samples. RT-qPCR count presented a viral load ranging from (2.7 ± 0.1) log10 copies/mL to (3.6 ± 0.1) log10 copies/mL in patient samples. These results were also evaluated using Bland-Altman analysis (Figure S8b), and this analysis showed that there was no evidence for a systematic bias for HIV viral load from HIV-infected patient blood samples.

FIGURE 5.

Quantitative detection with HIV-infected patient samples using curve fitting analysis method. a) Discarded HIV-infected patient samples in whole blood were evaluated using nanoplasmonic platform. Correlation was presented between HIV count obtained by RT-qPCR and nanoplasmonic platform. Nanoplasmonic platform presented a viral load ranging from (1.3 ± 0.7) log10 copies/mL to (4.3 ± 1.2) log10 copies/mL in patient samples. RT-qPCR count presented a viral load ranging from (2.7 ± 0.1) log10 copies/mL to (3.6 ± 0.1) log10 copies/mL in patient samples. The data for wavelength measurements were presented as wavelength measurements ± standard error of the mean (SEM). (n=5–6, error bars represent SEM). b) Bland-Altman Analysis between the nanoplasmonic platform and RT-qPCR counts did not display an evidence for a systematic bias for HIV viral load for HIV-infected patient blood samples tested. Quantitative measurements of HIV-infected patient samples using both methods are presented in Table S6.

From a clinical perspective, the limit of detection covered the range of values that include the current World Health Organization (WHO) definition of treatment failure (viral load (VL) >5,000 copies/mL)38, 39 as well as the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) definitions of treatment failure (VL >200 copies/mL).40 It is estimated that annually over 450,000 infants are infected through mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). To reduce morbidity and improve quality of life for persons living with HIV/AIDS, the WHO is rapidly expanding access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in developing countries accounting for over 67% of HIV-1 infections.39, 41 However, this expansion is significantly restricted by the lack of cost-effective POC viral load assays that can effectively reach patients living in rural settings. In the developed countries, HIV-1 viral load is regularly used to closely monitor and assess the patient response to ART, to ensure drug adherence, and to stage disease progression. In contrast, in developing countries, CD4+ T lymphocyte count and clinical symptoms are used to guide ART following the WHO guidelines with the exception of infants, where viral load assays are required.42, 43 Although CD4 testing is a great tool for monitoring patients,44, 45 recent studies have shown that CD4+ cell counting strategy cannot detect early virological failure.42, 43 However, HIV-1 viral load assays are expensive ($50–200 per test), instrument-dependent, and technically complex.

In developing countries, one of the most important issues is to prevent MTCT and extend AIDS care to HIV-1 positive infants. MTCT remains the primary cause of AIDS in children, with approximately 1,500 children infected per day.46 Rapid progression of AIDS in infants causes early death. Combined data from nine clinical trials in Africa showed that 35% of HIV-1 positive infants die by the age of 1 and 52% of HIV-1-infected children die by the age of 2, highlighting the importance of viral load monitoring to prevent MTCT in resource-constrained settings.47 Studies have shown that long-term suppression of HIV-1 replication in infants can be achieved by initiating ART, to reduce AIDS-related morbidity and mortality, and improve the quality of life.47, 48 To provide early AIDS care and ART to HIV-infected infants, early diagnosis is key. However, simple and rapid serological assays cannot detect HIV-infected infants until 18 months after birth.49 The late identification of AIDS children is due to the interference of maternal HIV-1 specific antibodies, which are passively transferred through the placenta and persist in infants for approximately 18 months.50 Thus, a readily available POC viral load test for early detection of HIV-infected infants is urgently needed in resource-constrained settings.

One potential application of this platform technology is in infant testing where HIV status cannot be monitored by white blood cell counting, and nucleic acid amplification assays are required.45, 51, 52 Another potential application is to monitor co-infections of tuberculosis-HIV in the AIDS epidemic regions.53 The presented nanoplasmonic platform technology detected viruses in whole blood of HIV-infected patients, which contain HIV antibodies. Since antibodies in men and women would not be any different, antibodies transferred from women to their infants would not be expected to have any greater effect in interfering with detection (i.e., if antibodies do not interfere with detection in infected adults, passively transferred antibodies will not interfere with detection in infants). In the clinical samples, we have tested so far, we have not observed any interference effects. Additionally, viruses cannot be completely neutralized by antibodies,54 and still expose antigens on the virus surface allowing them to be captured by the biosensing platform. Further, this detection system has multiple advantages over current viral load tests (e.g., RT-qPCR assays) for both infant and adult testing, since it can potentially enable POC testing and significantly increase access to viral load monitoring in resource-constrained settings by (i) reducing the cost of reagents and instrument, (ii) reducing the complexity, sample preparation and amplification steps so that a health worker can perform the testing with minimal training, and (iii) shortening the assay time (1 hour for capture/incubation, 10 minutes for detection and data analysis) as opposed to ~6 hours required by RT-qPCR (e.g., COBAS Ampliprep/COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 Test55). To further decrease the capture/incubation assay time, the nanoplasmonic platform can potentially be integrated with microfluidic technologies as we earlier described.27

Additionally, in our nanoplasmonic detection system, we detected multiple subtypes using a polyclonal antibody that targets multiple epitopes of gp120 enabling the capture of various HIV subtypes. It was previously reported that anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody can be used as a generic capture agent for multiple HIV subtypes.7, 27 Despite the fact that different HIV subtypes have mutations and variations in RNA genome and surface receptors, there are several discontinuous conserved epitopes (V1-V5 loops) in the gp120 surface protein that help HIV enter CD4+ T lymphocytes.56–59 This conservation in the gp120 surface protein allows the capture of various HIV subtypes using a single antibody. Therefore, using this platform technology, other HIV subtypes could also be captured, detected and quantified with comparable efficiency and specificity due to their conserved epitopes as reported.27, 56–59 Here, we tested all HIV subtypes that were available to us through National Institutes of Health (NIH) under AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program including a panel subtype. In contrast, rapid evolution and mutation cause a detection challenge for RNA viruses (e.g., HIV) and the genetic diversity in virus subtypes interferes with the ability of PCR tests to recognize all current subtypes.

The nanoplasmonic biosensing platform has significant potential in clinical applications. The surface chemistry and highly specific antibody immobilization was utilized to minimize the background signal, since the background signal noise that is potentially generated by nonspecific binding of blood cells did not pose a detection challenge at low concentrations especially for the HIV-infected clinical samples. This biosensing technology is potentially sufficient to be used broadly in clinical microbiology and infectious disease laboratories. Moreover, this platform potentially provides a reliable, accurate, inexpensive, time-effective and ease-to-use detection system in global scale of life-threatening infectious diseases including HIV, poxvirus, and herpesvirus. Other viruses (e.g., SARS, H1N1) have different detection methods.60–62 For instance, researchers use nasal swabs, bronchoalveolar lavages, and nasopharyngeal aspirates or exhaled breath in addition to the blood samples for detection methods. In this study, we focused on blood-borne diseases (i.e., HIV). These different types of human samples have different physiological conditions. Detection platforms need to be adapted for handling these different sample types. On the other hand, the presented technology is a versatile platform that can be modified to detect other pathogens by altering the surface chemistry for pathogens having reasonably well-described markers available. The limit of detection of the presented platform demonstrates that low viral concentrations in whole blood (98 ± 39 copies/mL) can be detected. Further, the nanoplasmonic detection technology enables a biosensing platform with a multiplexed format that would have a vital role in biosensor design and engineering to selectively and specifically detect multiple pathogens and their subtypes/strains from patient samples using immobilization of highly specific antibodies at different regions of a sensor area.

CONCLUSIONS

The presented nanoplasmonic technology provides a detection platform that allows a fast, reliable, sensitive, specific, accurate, label and fluorescence-free quantification assay for viruses from whole blood without any sample preparation. We demonstrated that the extraordinary nanoplasmonic properties of nanoparticles can be deployed for multiple pathogen subtype detection. This platform technology utilizes the immobilization of highly specific anti-viral antibodies on the biosensing surface for selective and specific capture and detection of intact viruses from unprocessed clinical samples giving a viral load covering a broad range of clinically relevant concentrations. Here, we show a direct capture, detection and quantification platform technology for multiple HIV subtypes (A, B, C, D, E, G, and panel) and discarded patient samples from whole blood with high sensitivity and specificity. Additionally, detection of viruses from unprocessed whole blood demonstrates that this platform technology is feasible for diagnosis of viruses directly from patient samples. The nanoplasmonic detection platform can detect and quantify intact viruses without damaging the virus structure and characteristics including their capsid structure. Hence, this platform technology enables to rapidly isolate, capture, detect and quantify intact viruses. This biosensing platform can potentially be used for direct multiple pathogen detection using nanoplasmonic properties of nanoparticles taking a significant step towards providing POC tests at resource-constrained settings as well as at the hospital and primary care settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nanoplasmonic surface construction and HIV sampling

Briefly, the surface chemistry was performed in this order: (i) the coating of polystyrene wells with PLL hydrobromide with 70,000–150,000 of molecular weight (Sigma Co., St. Louis, MO), (ii) gold nanoparticle incubation on PLL-coated surface, (iii) surface activation and coupling reaction with MUA and EDC/NHS (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI), (iv) covalently binding of NeutrAvidin (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) using the succinimide ring on the activated surface, (v) blocking of non-specific binding with BSA (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI), (vi) biotinylated anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA) immobilization, and (vii) application of HIV spiked samples (100 µL) in whole blood or PBS by pipetting. Following each surface modification, the surfaces were washed out with 1x PBS three times by pipetting. After introducing virus samples, the nanoplasmonic platform was also rinsed with 1x PBS three times to remove all unbound viruses. The viruses captured inside the detection light beam area of the spectrometer contributed to the nanoplasmonic wavelength or extinction intensity change. Each data was subtracted from its own spectra, which was measured before the sampling (antibody immobilization), and the resulting shift was presented as wavelength or extinction intensity change ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

To prepare biosensing substrates, polystyrene surfaces (~36.9 mm2) were first modified by PLL to generate amine-terminated groups for gold nanoparticle binding. After PLL modification, gold nanoparticle solution (15703, TedPella, Redding, CA) was loaded onto each surface and incubated. The coefficient of variation for nanoparticles was indicated to be less than 8%, and the standard deviation for size variation was indicated as 0.5 nm by the manufacturer. After gold nanoparticle immobilization, MUA, N-Ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride/N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (EDC/NHS) coupling, NeutrAvidin binding, and biotinylated anti-gp120 polyclonal antibody immobilization were utilized on the surface. To minimize nonspecific binding on both inactive and reactive areas of the surface, BSA was used as a blocking agent on each surface and incubated for an hour. HIV culturing steps were briefly explained in Supporting Information (HIV culturing section). To spike HIV in whole blood, HIV subtypes were first quantified by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). In this study, we used a commercial RNA assay (COBAS Ampliprep/COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 Test performed by staff at Brigham and Women’s Hospital) to quantify stock concentration of different HIV subtypes. The samples with a cycle threshold (CT) value greater than that of the lowest standard point (50 copies/mL), which had a CT value of 39–40 (50 PCR cycles were run in total), were reported as below 50 copies/mL. The low copies of HIV viral load were earlier reported using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) systems.63, 64 The amplification profile of negative control remained below the threshold after 50 cycles of amplification; all the samples including the lowest standard displayed CT values (20–40) less than 50 CT values. HIV samples were incubated on the biosensing platform for an hour. Whole blood samples without HIV were used as controls. We also evaluated the nanoplasmonic platform with discarded, anonymous HIV-infected patient whole blood samples. These samples were obtained from Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA) under Institutional Review Board approval. HIV sampling experiments were performed in biosafety level (BSL)2+ laboratories, and the biosensing platform was evaluated in BSL2 laboratories after HIV sample was fixed with a paraformaldehyde-containing solution. We performed 3 replicates for RT-qPCR measurements and 6 replicates for nanoplasmonic measurements for each HIV subtype and patient sample. The standard errors for both RT-qPCR and nanoplasmonic measurements were reported. To minimize dilution inaccuracies, a second set of RT-qPCR was performed three times for each diluted HIV spiked sample. Same HIV RNA quantification protocol was used for discarded HIV patient samples (Supporting Information: Quantification of HIV subtypes by RT-qPCR and sampling section).

Spectral measurements and data analysis

The experiments were performed using HIV subtypes A, B, C, D, E, G, panel, and discarded anonymous HIV-infected patient samples. Each binding study was characterized with a detected shift of the maximum extinction point of gold nanoparticles by Varioskan® Flash Spectral Scanning Multimode Readers, Thermo Scientific. The detection light beam area of the spectrometer was indicated as 3.14 mm2 (maximum). The spectral resolution and intensity accuracy of the instrument with a fixed slit setting was 1 nm and 0.003 a.u. extinction intensity. The measuring mode was set to scan the extinction changes per wavelength from 400 nm to 700 nm over 301 steps.

To analyze the wavelength data, we employed two approaches (i.e., curve fitting and experimental data maximum). In the first method, a MATLAB code was written to find the nanoplasmonic wavelength peak of each recorded spectra from curve fitting. A Fourier type expansion with 8 harmonics (i.e.,

where ω is the fundamental frequency of the signal, an and bn are expansion coefficients) was used to fit to each recorded spectra.65 The R2 values were found to be greater than 0.99 with the MATLAB fit command. The wavelengths at the maximum extinction value for each recorded spectra were extracted from the curve fits and were rounded to the first decimal digit considering the finite resolution of the experiment. Individual reference curve subtraction was performed for each HIV subtype curve at a given virus concentration from the corresponding reference curve. All data for wavelength measurements were presented as the mean of wavelength measurements ± SEM.66 The experimental spectra evaluated by the experimental data maximum method were compared with the Fourier type In the second data analysis method, nanoplasmonic wavelength peak was determined as the wavelength at the maximum extinction value, and all data for wavelength and extinction intensity measurements were presented as the mean of wavelength or extinction intensity measurements ± SEM.66 For each HIV subtype curve at a given virus concentration, individual reference curve subtraction was carried out from the corresponding reference curve. Considering the resolution of the instrument, the data was presented with one decimal digit in the results, and the errors from the finite resolution of the spectrometer were considered in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate each modification on gold nanoparticles, we analyzed the experimental results (n=6–216) using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance followed by the Mann-Whitney U test with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons with statistical significance threshold set at 0.05 (p<0.05). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. To evaluate the repeatability of the nanoplasmonic platform count using residual analysis in comparison to RT-qPCR counts, Bland–Altman comparison analysis was used. The coefficient of repeatability was calculated as 1.96 times the standard deviation of the difference between nanoplasmonic platform and RT-qPCR counts for the same sample. A clinically acceptable range was considered as the interval within which the difference between the measurements from each method would fall with 95% confidence interval. Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab (Release 14, Minitab Inc., State College, PA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. John Carney and Paul Nisson for discussions and feedback. We would like to acknowledge NIH RO1AI093282, NIH RO1AI081534, NIH U54EB15408, NIH R21AI087107, and BRI Translatable Technologies and Care Innovation Grant. This work was made possible by a research grant that was awarded and administered by the U.S. Army Medical Research & Materiel Command (USAMRMC) and the Telemedicine & Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) at Fort Detrick, MD.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION PARAGRAPH

The details of surface modification, antibody immobilization, HIV quantification, atomic force microscopy analysis, and scanning electron microscopy imaging used in this study can be found. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. F.I. and U.D. developed the idea; D.R.K., U.D. collaborated on the paper; F.I. and U.D. designed the experimental approach; F.I., S.W., U.A.G., O.T., S.T., and U.D. performed the experiments; F.I., S.W., U.A.G., O.T., S.T., and U.D. analyzed the data; F.I., S.W., U.A.G., O.T., S.T., and U.D. wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berkley S, Bertram K, Delfraissy J-F, Draghia-Akli R, Fauci A, Hallenbeck C, Kagame MJ, Kim P, Mafubelu D, Makgoba MW, et al. The 2010 Scientific Strategic Plan of The Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise. Nat. Med. 2010;16:981–989. doi: 10.1038/nm0910-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [Accessed May 4, 2013];World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory (GHO) - HIV/AIDS. 2012 Available at: www.who.int/gho/hiv/en/index.html.

- 3.Wang S, Xu F, Demirci U. Advances in Developing HIV-1 Viral Load Assays for Resource-Limited Settings. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010;28:770–781. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karst SM. Pathogenesis of Noroviruses Emerging RNA Viruses. Viruses. 2010;2:748–781. doi: 10.3390/v2030748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulinski MD, Mahalanabis M, Gillers S, Zhang JY, Singh S, Klapperich CM. Sample Preparation Module for Bacterial Lysis and Isolation of DNA From Human Urine. Biomed. Microdevices. 2009;11:671–678. doi: 10.1007/s10544-008-9277-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White RA, Blainey PC, Fan HC, Quake SR. Digital PCR Provides Sensitive and Absolute Calibration for High Throughput Sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2009:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafiee H, Jahangir M, Inci F, Wang S, Willenbrecht RBM, Giguel FF, Tsibris AMN, Kuritzkes DR, Demirci U. Acute On-Chip HIV Detection Through Label-Free Electrical Sensing of Viral Nano-Lysate. Small. 2013 doi: 10.1002/smll.201202195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Y-G, Moon S, Kuritzkes DR, Demirci U. Quantum Dot-based HIV Capture and Imaging In A Microfluidic Channel. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009;25:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurkan UA, Moon S, Geckil H, Xu F, Wang S, Lu TJ, Demirci U. Miniaturized Lensless Imaging Systems for Cell and Microorganism Visualization in Point-of-Care Testing. Biotechnol. J. 2011;6:138–149. doi: 10.1002/biot.201000427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams EH, Schreifels JA, Rao MV, Davydov AV, Oleshko VP, Lin NJ, Steffens KL, Krylyuk S, Bertness KA, Manocchi AK, et al. Selective Streptavidin Bioconjugation on Silicon and Silicon Carbide Nanowires for Biosensor Applications. J. Mater. Res. 2012:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang G-J, Zhang L, Huang MJ, Luo ZHH, Tay GKI, Lim E-JA, Kang TG, Chen Y. Silicon Nanowire Biosensor for Highly Sensitive and Rapid Detection of Dengue Virus. Sens. Actuators, B. 2010;146:138–144. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuzmych O, Allen BL, Star A. Carbon Nanotube Sensors for Exhaled Breath Components. Nanotechnology. 2007:18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barone PW, Strano MS. Single Walled Carbon Nanotubes as Reporters for The Optical Detection of Glucose. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2009;3:242–252. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patolsky F, Zheng G, Lieber CM. Nanowire Sensors for Medicine and the Life Sciences. Nanomedicine (London, U. K.) 2006;1:51–65. doi: 10.2217/17435889.1.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irvine DJ. Drug Delivery One Nanoparticle One Kill. Nat. Mater. 2011;10:342–343. doi: 10.1038/nmat3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larguinho M, Baptista PV. Gold And Silver Nanoparticles For Clinical Diagnostics - From Genomics To Proteomics. J. Proteomics. 2012;75:2811–2823. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willets KA, Van Duyne RP. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Spectroscopy and Sensing. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2007;58:267–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chau L-K, Lin Y-F, Cheng S-F, Lin T-J. Fiber-optic Chemical and Biochemical Probes Based on Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance. Sens. Actuators, B. 2006;113:100–105. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law W-C, Yong K-T, Baev A, Prasad PN. Sensitivity Improved Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for Cancer Biomarker Detection Based on Plasmonic Enhancement. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4858–4864. doi: 10.1021/nn2009485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endo T, Kerman K, Nagatani N, Takamura Y, Tamiya E. Label-Free Detection of Peptide Nucleic Acid-DNA Hybridization Using Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Based Optical Biosensor. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6976–6984. doi: 10.1021/ac0513459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drachev VP, Perminov SV, Rautian SG. Optics of Metal Nanoparticle Aggregates with Light Induced Motion. Opt. Express. 2007;15:8639–8648. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.008639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nair TM, Myszka DG, Davis DR. Surface Plasmon Resonance Kinetic Studies of the HIV TAR RNA Kissing Hairpin Complex and Its Stabilization by 2-Thiouridine Modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1935–1940. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.9.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myszka DG, Sweet RW, Hensley P, Brigham-Burke M, Kwong PD, Hendrickson WA, Wyatt R, Sodroski J, Doyle ML. Energetics of The HIV Gp120-CD4 Binding Reaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:9026–9031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haynes CL, Van Duyne RP. Nanosphere Lithography: A Versatile Nanofabrication Tool for Studies of Size-dependent Nanoparticle Optics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:5599–5611. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer KM, Hafner JH. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:3828–3857. doi: 10.1021/cr100313v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Day ES, Bickford LR, Slater JH, Riggall NS, Drezek RA, West JL. Antibody-conjugated Gold-Gold Sulfide Nanoparticles as Multifunctional Agents for Imaging and Therapy of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010;5:445–454. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S, Esfahani M, Gurkan UA, Inci F, Kuritzkes DR, Demirci U. Efficient On-Chip Isolation of HIV Subtypes. Lab Chip. 2012;12:1508–1515. doi: 10.1039/c2lc20706k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor BN, Kuyatt CE. Guidelines for Evaluating and Expressing the Uncertainty of NIST Measurement Results. [Accessed May 4, 2013];NIST Technical Note 1297. 1994 Available at: http://physics.nist.gov/Pubs/guidelines/TN1297/tn1297s.pdf.

- 29.Wang W, Liang L, Johs A, Gu B. Thin Films of Uniform Hematite Nanoparticles: Control of Surface Hydrophobicity and Self-Assembly. J. Mater. Chem. 2008;18:5770–5775. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinrib H, Meiri A, Duadi H, Fixler D. Uniformly Immobilizing Gold Nanorods on a Glass Substrate. J. At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 2012:6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haes AJ, Van Duyne RP. A Nanoscale Optical Biosensor: Sensitivity and Selectivity of An Approach Based On The Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Spectroscopy of Triangular Silver Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10596–10604. doi: 10.1021/ja020393x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Duyne RP, Haes AJ, McFarland AD. Nanoparticle Optics: Sensing With Nanoparticle Arrays and Single Nanoparticles. In: Lian T, Dai HL, editors. Physical Chemistry of Interfaces and Nanomaterials II. Vol. 5223. 2003. pp. 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei QH, Su KH, Durant S, Zhang X. Plasmon Resonance of Finite One-Dimensional Au Nanoparticle Chains. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1067–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sonnichsen C, Reinhard BM, Liphardt J, Alivisatos AP. A Molecular Ruler Based On Plasmon Coupling Of Single Gold and Silver Nanoparticles. Nat. Biotech. 2005;23:741–745. doi: 10.1038/nbt1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haes AJ, Zou SL, Schatz GC, Van Duyne RP. Nanoscale Optical Biosensor: Short Range Distance Dependence of the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance of Noble Metal Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:6961–6968. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anker JN, Hall WP, Lyandres O, Shah NC, Zhao J, Van Duyne RP. Biosensing with Plasmonic Nanosensors. Nat. Mater. 2008;7:442–453. doi: 10.1038/nmat2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu H, Kim K, Ma K, Lee W, Choi J-W, Yun C-O, Kim D. Enhanced Detection of Virus Particles by Nanoisland-Based Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013;41:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castelnuovo B, Sempa J, Agnes KN, Kamya MR, Manabe YC. Evaluation of WHO Criteria for Viral Failure in Patients on Antiretroviral Treatment in Resource-Limited Settings. AIDS Res. Treat. 2011:736–938. doi: 10.1155/2011/736938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. [Accessed May 4, 2013];World Health Organization, Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents, Recommendations for a public health approach, 2010 revision. 2010 Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf. [PubMed]

- 40. [Accessed May 4, 2013];Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults And Adolescents. 2011 Available at: http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- 41. [Accessed May 4, 2013];World Health Organization, Rapid Advice: Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents. 2009 Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/rapid_advice_art.pdf.

- 42.Mee P, Fielding KL, Charalambous S, Churchyard GJ, Grant AD. Evaluation of The WHO Criteria for Antiretroviral Treatment Failure Among Adults In South Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1971–1977. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e4cd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Oosterhout JJG, Brown L, Weigel R, Kumwenda JJ, Mzinganjira D, Saukila N, Mhango B, Hartung T, Phiri S, Hosseinipour MC. Diagnosis of Antiretroviral Therapy Failure in Malawi: Poor Performance of Clinical and Immunological WHO Criteria. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2009;14:856–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jokerst JV, Floriano PN, Christodoulides N, Simmons GW, McDevitt JT. Integration of Semiconductor Quantum Dots into Nano-bio-chip Systems for Enumeration of CD4+T cell Counts at the Point-of-Need. Lab Chip. 2008;8:2079–2090. doi: 10.1039/b817116e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moon S, Gurkan UA, Blander J, Fawzi WW, Aboud S, Mugusi F, Kuritzkes DR, Demirci U. Enumeration of CD4(+) T-Cells Using a Portable Microchip Count Platform in Tanzanian HIV-Infected Patients. PLoS One. 2011:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. [Accessed May 4, 2013];UNAIDS, 2008 Report On The Global AIDS Epidemic. 2008 Available at: http://data.unaids.org/pub/GlobalReport/2008/JC1510_2008GlobalReport_en.zip.

- 47.Newell ML, Coovadia H, Cortina-Borja M, Rollins N, Gaillard P, Dabis F. Mortality of Infected and Uninfected Infants Born To HIV-Infected Mothers in Africa: A Pooled Analysis. Lancet. 2004;364:1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rouet F, Fassinou P, Inwoley A, Anaky MF, Kouakoussui A, Rouzioux C, Blanche S, Msellati P. Long-Term Survival and Immuno-Virological Response of African HIV-1-Infected Children to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Regimens. AIDS. 2006;20:2315–2319. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328010943b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Busch MP, Satten GA. Time Course of Viremia and Antibody Seroconversion Following Human Immunodeficiency Virus Exposure. Am. J. Med. 1997;102:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lujan-Zilbermann J, Rodriguez CA, Emmanuel PJ. Pediatric HIV Infection: Diagnostic Laboratory Methods. Fetal Pediatr. Pathol. 2006;25:249–260. doi: 10.1080/15513810601123367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ozcan A, Demirci U. Ultra Wide-Field Lens-Free Monitoring of Cells On-Chip. Lab Chip. 2008;8:98–106. doi: 10.1039/b713695a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alyassin MA, Moon S, Keles HO, Manzur F, Lin RL, Haeggstrom E, Kuritzkes DR, Demirci U. Rapid Automated Cell Quantification on HIV Microfluidic Devices. Lab Chip. 2009;9:3364–3369. doi: 10.1039/b911882a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S, Inci F, De Libero G, Singhal A, Demirci U. Point-Of-Care Assays for Tuberculosis: Role of Nanotechnology/Microfluidics. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013;31:438–449. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnston MI, Fauci AS. An HIV Vaccine - Challenges and Prospects. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:888–890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0806162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. [Accessed May 4, 2013];World Health Organization, Technical Brief on HIV Viral Load Technologies (June 2010) 2012 Available at: www.who.int/hiv/topics/treatment/tech_brief_20100601_en.pdf.

- 56.Wyatt R, Kwong PD, Desjardins E, Sweet RW, Robinson J, Hendrickson WA, Sodroski JG. The Antigenic Structure of the HIV Gp120 Envelope Glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y, Migueles SA, Welcher B, Svehla K, Phogat A, Louder MK, Wu X, Shaw GM, Connors M, Wyatt RT, et al. Broad HIV-1 Neutralization Mediated By CD4-Binding Site Antibodies. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1032–1034. doi: 10.1038/nm1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu X, Yang ZY, Li Y, Hogerkorp CM, Schief WR, Seaman MS, Zhou T, Schmidt SD, Wu L, Xu L, et al. Rational Design of Envelope Identifies Broadly Neutralizing Human Monoclonal Antibodies to HIV-1. Science. 2010;329:856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou T, Xu L, Dey B, Hessell AJ, Van Ryk D, Xiang SH, Yang X, Zhang MY, Zwick MB, Arthos J, et al. Structural Definition of a Conserved Neutralization Epitope on HIV-1 gp120. Nature. 2007;445:732–737. doi: 10.1038/nature05580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stohr K World Hlth Org Multicentre, C. A Multicentre Collaboration to Investigate the Cause of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1730–1733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13376-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC, Yee WK, Wang T, Chan-Yeung M, Lam WK, Seto WH, Yam LY, Cheung TM, et al. A Cluster of Cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1977–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ginocchio CC, McAdam AJ. Current Best Practices for Respiratory Virus Testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barletta JM, Edelman DC, Constantine NT. Lowering The Detection Limits of HIV-1 Viral Load Using Real-time Immuno-PCR for HIV-1 p24 Antigen. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004;122:20–27. doi: 10.1309/529T-2WDN-EB6X-8VUN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun R, Ku J, Jayakar H, Kuo JC, Brambilla D, Herman S, Rosenstraus M, Spadoro J. Ultrasensitive Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay for Quantitation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 RNA in Plasma. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998;36:2964–2969. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2964-2969.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Faunt LM, Johnson ML. Analysis of Discrete Time-Sampled Data Using Fourier-Series Method. Methods Enzymol. 1992;210:340–356. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)10017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor JR. An Introduction to Error Analysis: The Study of Uncertainties in Physical Measurements. 2nd Ed. University Science Book; 1996. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.