Abstract

Preclinical studies have shown that hypomethylating agents reverse platinum resistance in ovarian cancer. In this phase II clinical trial, based upon the results of our phase I dose defining study, we tested the clinical and biologic activity of low-dose decitabine administered before carboplatin in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer patients. Among 17 patients with heavily pretreated and platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, the regimen induced a 35% objective response rate (RR) and progression-free survival (PFS) of 10.2 months, with nine patients (53%) free of progression at 6 months. Global and gene-specific DNA demethylation was achieved in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumors. The number of demethylated genes was greater (P < 0.05) in tumor biopsies from patients with PFS more than 6 versus less than 6 months (311 vs. 244 genes). Pathways enriched at baseline in tumors from patients with PFS more than 6 months included cytokine–cytokine receptor interactions, drug transporters, and mitogen-activated protein kinase, toll-like receptor and Jak-STAT signaling pathways, whereas those enriched in demethylated genes after decitabine treatment included pathways involved in cancer, Wnt signaling, and apoptosis (P < 0.01). Demethylation of MLH1, RASSF1A, HOXA10, and HOXA11 in tumors positively correlated with PFS (P < 0.05). Together, the results of this study suggest that low-dose decitabine altered DNA methylation of genes and cancer pathways, restoring sensitivity to carboplatin in patients with heavily pretreated ovarian cancer and resulting in a high RR and prolonged PFS.

Introduction

Women with advanced stage ovarian cancer have a 5-year survival rate of less than 25% (1). Although most patients respond to platinum-based chemotherapy, relapses are common, leading to platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, which is uniformly fatal (2). Similar to other malignancies, ovarian cancer progression is associated with accumulation of aberrant gene promoter methylation (3, 4), leading to transcriptional silencing of tumor suppressor genes (TSG). Like genetic changes that affect TSGs to promote tumorigenesis through deletions or mutations, aberrant epigenetic modifications also act as inactivating “hits” during cancer initiation and/or progression (5). In ovarian cancer, specifically, epigenetic silencing is known to repress the expression of TSGs such as RASSF1A, BRCA1, DAPK, and OPCML, and development-associated transcription factors such as HOXA10 and HOXA11 (4, 6, 7), and such changes are associated with both ovarian cancer initiation and progression to chemotherapy resistance (4, 8).

In-depth characterization of the cancer epigenome during the past decade has shown that DNA hypomethylating or histone deacetylation-inhibiting agents can restore the expression of epigenetically silenced TSGs, resulting in antitumor activity (5, 9). This concept was first validated in hematologic malignancies, for which 2 hypomethylating agents are U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved and clinically active as monotherapy. Although single-agent hypomethylation strategies have proven disappointing in clinical trials of solid tumors (10), preclinical studies strongly support the use of combination regimens, showing the hypomethylating agents azacitadine and decitabine to restore platinum sensitivity in chemoresistant ovarian cancer cell lines and xenografts (11–14). On the basis of this rationale, we conducted a phase I, dose defining study, combining low-dose decitabine with carboplatin (15). Repetitive, low-dose decitabine has shown improved clinical activity over bolus administration in hematologic malignancies (9, 16). We therefore hypothesized that this schedule of administration over 5 days before platinum would more effectively induce DNA hypomethylation and TSG reexpression (9, 16), as compared with bolus administration of higher (and more toxic) doses of decitabine previously tested (17). We further reasoned that the repetitive administration of decitabine (a DNA replication-dependent nucleoside analog) and the time delay to the delivery of the chemotherapeutic would allow cancer cells to undergo several cycles of division, thus permitting greater incorporation of decitabine (and inhibition of DNA methyltransferases) and subsequent activation of chemotherapy response TSGs (18). Our previous trial showed tolerability of decitabine at a dose of 10 mg/m2 daily for 5 days preceding carboplatin administration on day 8 in ovarian cancer patients (15). Pharmacodynamic analyses using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and DNA extracted from plasma showed that the regimen was biologically active, as evidenced by global and gene-specific DNA hypomethylation (15), setting the stage for this phase II trial.

Here, we report the results of a phase II trial measuring the clinical and biologic activity of this regimen in patients with recurrent, platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. We show that low-dose decitabine alters global and gene-specific DNA methylation, yielding a high response rate (RR) and prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) in this patient population. Decitabine-induced hypomethylation of several ovarian cancer–associated TSGs in tumors positively correlated with PFS, indicating convergence of biologic and clinical endpoints.

Materials and Methods

Patient population

Patients with ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal carcinomatosis who progressed during or recurred within 6 months after platinum-based chemotherapy were eligible. Eligibility included both measurable and detectable disease. Measurable disease was defined according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor (RECIST 1.0; ref. 19). For patients with non-measurable disease, clinically or radiographically detectable disease, and a pretreatment serum CA-125 level at least twice the upper limit of normal were required. All patients were at least 18 years old with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 to 1, had a life expectancy of 3 months or more, and were willing to undergo tumor biopsy or ascites collection before and after decitabine treatment. Eligibility allowed unlimited number of prior cytotoxics, required adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function, and the presence of either ascites or tumor implants that could be biopsied using imaging-guided techniques. Two core biopsies were required for each time point. Key exclusion criteria included carboplatin hypersensitivity, brain metastases, grade 2 or more neuropathy, or uncontrolled medical problems. All patients signed informed consent and the protocol was approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board.

Treatment plan

Treatment consisted of the DNA hypomethylating agent decitabine (Eisai) at 10 mg/m2 given intravenously daily for 5 days, and carboplatin (Bristol Meyers Squibb) administered intravenously on day 8 for an area under the curve of 5, based on the results of our phase I trial (15). To prevent prolonged myelosupression (observed during phase I), peg-filgastrim (Amgen) was administered on day 9. Each cycle was 4 weeks and treatment continued until disease progression (PD) or intolerable toxicity.

Efficacy and toxicity assessments

Adverse events (AE) were assessed on day 1 of each cycle and graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for AEs, National Cancer Institute (NCI-CTCAE), v3. Tumor burden was evaluated radiographically at baseline, before each odd cycle, when clinically indicated, and at the end of treatment. Investigator-determined best overall response was defined using RECIST1.0 criteria for patients with measurable tumors. CA-125 measurements were obtained from all patients on day 1 of each cycle and modified Rustin criteria were used to assess response only for those patients with detectable disease (20).

Blood, tumor biopsies, and/or ascites collection

For cycles 1 and 2, blood was collected on EDTA at baseline (pretreatment) and on day 8 (before carboplatin administration), and centrifuged to separate plasma from PBMCs. Ascites fluid or tumor material were obtained through core biopsies under radiographic guidance on days 1 (pretreatment) and 8 (before carboplatin) during cycle 1 from all enrolled patients. After ascites collection, cells were pelleted by centrifugation and snap frozen.

DNA extraction and bisulphite conversion

DNA was extracted from 200 μL of buffy coat, 1 mL of plasma, 25 mg tumor tissue, or 200 μL ascites using QIAmp DNA Blood Mini Kits (Qiagen), as we have previously described (15). Sodium bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA and cleanup were done using EZ DNA Methylation kits (Zymo Research), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Methylation assays by Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadChip hybridization

After bisulfite treatment, each sample was whole-genome amplified, enzymatically fragmented, and then applied to Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadChips (Illumina) using Illumina-supplied reagents and conditions at the Cleveland Clinic Genomics Core (Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland, OH). Details of hybridization and data analysis [including clustering, functional pathway prediction, and gene ontology (GO)] are presented online. The Infinium analysis results are available for download at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) data repository at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the accession number GEO31826.

DNA methylation analysis by pyrosequencing

To validate the Infinium bead array results, methylation levels of candidate-specific genes were determined by PCR amplification of bisulphate-converted DNA with specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). Methylated CpG sites in sequencing reactions were detected using a pyrosequencing system (Qiagen; ref. 21). Pyro Mark Assay Design and Pyro Q-CpG software were used for primer design and data analysis, respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Average methylation levels of individual CpG sites for each DNA sample were calculated.

Statistical analysis

This was an open-label, single-center phase II study. The primary objectives were RR, defined as complete response (CR) or partial response (PR), by either RECIST or modified Rustin criteria. Secondary endpoints were clinical benefit rate, defined as the sum of CRs, PRs, and stable disease (SD) lasting more than 3 months, PFS, safety, and overall survival (OS). Translational objectives included measurement of the regimen’s biologic activity as hypomethylation of target sequences. The optimal 2-stage design was used to test the null hypothesis H0 that RR ≤ 0.050 versus Ha RR ≥ 0.250 with power = 81% and type I error rate = 0.047. The expected sample size was 12 and the probability of early termination of 0.630. The design tested the drug combination on 9 patients in the first stage, with the expectation that stage 1 would be terminated if no response were recorded. If not terminated, additional patients were to be recruited (second stage) to reach a total of 17. H0 would be rejected if more than 2 of 17 patients responded.

Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized using medians (with ranges) for continuous variables, counts, and proportions for categorical variables. Toxicity was measured by the frequency/percentage and severity of AE. Paired t tests were used to compare global or gene-specific methylation levels. To account for the correlation of measurements from the same subject, methylation data were also analyzed using linear random–effect models. Factors included in the model were days and cycle number. Marginal effects were estimated by averaging over other factors. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate PFS for different groups and log-rank test was used to compare the PFS curves of different groups. Pathway and function analysis was carried out using DAVID (22) or Pathway Express (23). Normal approximation with 2-sample Z test was used to compare proportions. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were done using SAS 9.2 (SAS Inc.) and R software.

Results

Patients

Eighteen patients consented and 17 were enrolled and treated, with one woman not meeting the eligibility criteria (see Methods). As shown in Table 1, 16 patients had measurable and one had detectable disease, whereas 15 women had platinum-resistant and 2 had platinum-refractory ovarian cancer. The median age was 60 (range 45–83) and serous papillary carcinoma was the most common histology (15 patients). The group was heavily pretreated with a median of 5 prior regimens (range 1–10).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Patients | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Number | 17 |

| Age (median, range) | 60 (45–83) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 | 16 |

| 1 | 1 |

| Primary site of tumor | |

| Ovary | 17 |

| Primary peritoneal | 0 |

| Histologic subtype | |

| Serous papillary | 15 |

| Other | 2 |

| Number of prior therapies | |

| Median | 5 |

| Range | 1–10 |

| Platinum sensitivity | |

| Refractory | 2 |

| Resistant | 15 |

| Measurable disease (RECIST) | 16 |

Treatment administration and safety

The median number of treatment cycles administered was 6 (range 2–26+). Causes for treatment discontinuation were progressive disease (7) and toxicity (8). One patient is still receiving treatment, 2.5 years after start of therapy. Table 2 lists treatment-related AEs. The most common toxicities were nausea (n = 10), constipation (n = 7), allergic reactions (n = 6), neutropenia, fatigue, anemia (5 patients each), the majority being grades 1–2. Grade 3–4 toxicities affecting more than one patient included neutropenia (n = 4) and thrombocytopenia (n = 2).

Table 2.

Toxicity

| Toxicity (CTCAE v3) | Grade 3, n | Grade 4, n | All grades, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea | — | — | 10 (59) |

| Constipation | — | 1 | 7 (41) |

| Allergic reaction | 1 | — | 6 (35) |

| Neutropenia | 1 | 3 | 5 (29) |

| Fatigue | — | — | 5 (29) |

| Hemoglobin | 2 | — | 5 (29) |

| Anorexia | — | — | 4 (24) |

| Diarrhea | — | — | 4 (24) |

| Vomiting | — | — | 4 (24) |

| Platelets | 1 | 1 | 4 (24) |

| Dizziness | — | — | 3 (18) |

| Fever | — | — | 2 (12) |

| Febrile neutropenia | — | 1 | 1 (6) |

Efficacy

Except for one patient with detectable, recurrent ovarian cancer, the rest had measurable disease and were assessed by RECIST. As shown in the waterfall plot of RECIST-defined tumor responses in Fig. 1A, 5 PRs were observed. One additional GCIC-defined CR (one patient with detectable disease who experienced resolution of ascites and normalization of CA125) was recorded, for a RR of 35% [confidence interval (CI): 14–62, P = 0.0001). Six additional patients had SD as best response lasting more than 3 months, yielding a clinical benefit ratio of 70% (95% CI: 44–90). Five patients experienced progressive disease at first assessment. At 6 months, 9 patients (53%) were without progression. Median PFS was 10.2 months (95% CI: 1.9–14.8 months, Fig. 1B). The median OS was 13.8 months (95% CI: 10.3 months infinity).

Figure 1.

Clinical activity. A, waterfall plot of RECIST defined responses (n = 16 patients with measurable disease). B, Kaplan–Meier curve for PFS. The solid line represents the estimation of the survival function and the dashed lines represent the 95% CIs.

Pharmacodynamic activity

To evaluate biologic effects of the regimen, demethylating activity in vivo was assessed. PBMCs (n = 17), plasma (n = 17), paired (pre-/posttreatment) tumor biopsies (n = 10) or ascites (n = 6) were collected on days 1 and 8 of cycle 1 (tumor biopsies were attempted but could only be obtained from one patient). As a surrogate for decitabine-induced global demethylation, methylation of LINE1 (long interspersed) repetitive elements in PBMCs DNA was assessed by pyrosequencing. PBMCs LINE1 methylation levels of all patients analyzed showed reduced (P < 0.001) DNA methylation on day 8 as compared with day 1 (Fig. 2A), returning to baseline values by end of study (in most instances, coinciding with PD). However, significant global demethylation was not observed in tumor biopsies (Fig. 2B). The data, separated by PFS more than 6 or less than 6 months, are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Global, CpG island DNA methylation was also measured by Infinium bead arrays, with methylation changes defined based on the β value: β greater than 0.5 for patients within a group for gene hypermethylation and β less than 0.5 for hypomethylation (i.e., demethylation). The overall number of demethylated genes, as well as genes that remained hypermethylated in PBMCs and in tumors after decitabine therapy is illustrated using Venn diagrams (Fig. 2C and D) and correlated with duration of PFS (>6 or <6 months). The number of demethylated genes (in all responding patients) was greater in core biopsies obtained from patients with PFS more than 6 versus less than 6 months (311 vs. 244 genes) and also in PBMCs (630 genes vs. 474 genes, PFS > 6 vs. < 6 months). These results, showing a very large number of shared decitabine-induced demethylated genes in responders, suggested that treatment-induced gene hypomethylation contributes to the reversal of platinum resistance.

Figure 2.

Pharmacodynamic activity of decitabine on global DNA demethylation. A, LINE1 methylation measured by pyrosequencing in PBMCs on days 1 and 8 (C1D1, C1D8) of cycles 1 and 2 (C2D1, C2D8), and at end of study. Significant demethylation was found on C1D8 and C2D8 during the treatment. There was no difference between days 1 of both cycles. Bars/error bars represent mean ± SD. *, P < 0.05. B, LINE1 in biopsy samples from patients on days 1 and 8 of cycle 1. Bars/error bars represent mean ± SD. C, Venn diagrams show the numbers of demethylated and remaining hypermethylated genes in PBMCs after decitabine treatment in patients PFS less than 6 months versus PFS more than 6 months. Dotted line divides the demethylated gene numbers and remained hypermethylated gene numbers after first cycle treatment (β value greater than 0.5 is considered as hypermethylated). D, Venn diagrams show the numbers of demethylated genes and remaining hypermethylated genes in biopsies after decitabine treatment in patients achieving PFS less than 6 months versus PFS more than 6 months.

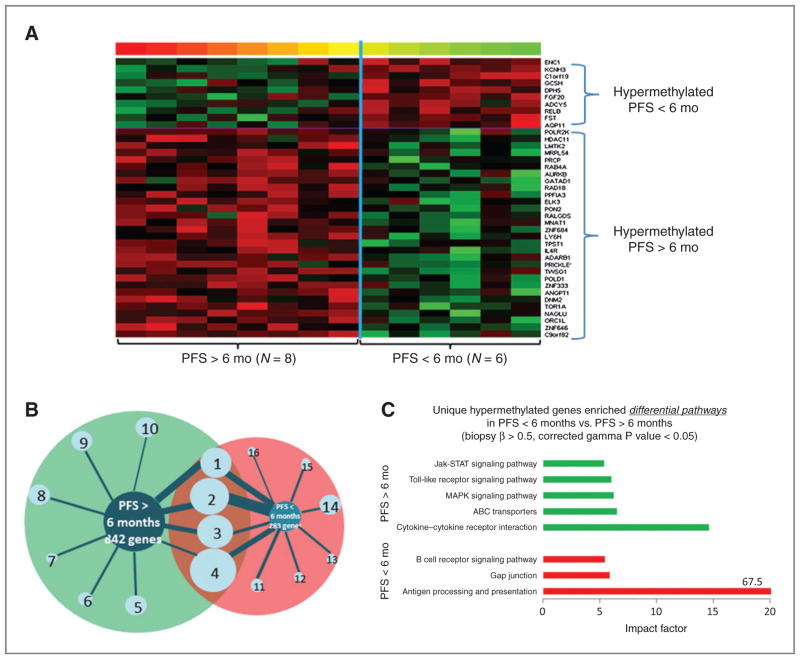

Baseline methylation differences in patients with PFS more than 6 versus less than 6 months are illustrated by heat maps. Before decitabine treatment on day 1, substantial differential methylation was observed between the 2 groups, with 842 genes and 283 hypermethylated genes in PFS more than 6 versus less than 6 months, respectively (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. S2). Functional clustering analysis of each differentially hypermethylated gene cluster in the 2 groups was done by GO term enrichment, using DAVID (22). Enrichment (geometric P values < 0.01) of 10 functional clusters was observed (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Table S2), and 4 clusters were shared between the 2 patient groups. The top-ranked GO biologic processes in PFS more than 6 versus less than 6 months were defense response, inflammatory response, and cytokine–cytokine interaction versus immunoglobulin family, immune response, and cell adhesion (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3.

Differentially hypermethylated genes at baseline for PFS > 6 months versus PFS < 6 months. A, heat map represents the differences in gene methylation levels at baseline (i.e., pretreatment) in tumor biopsies (n = 14). Methylation levels are color coded as red (high β value) to green (low β value). P values less than 0.01, using 2-sample t tests comparing responders to nonresponders, were used for selecting differentially methylated genes. B, a map of enriched functional clusters based on functional clustering, using the online webtool DAVID, for genes that were hypermethylated in biopsies from responders (PFS > 6 months) versus nonresponders (PFS < 6 months), respectively. The size of the bars (wheel spokes) and the circles represent the gene counts and enrichment scores, respectively. Hypermethylation was defined by β values greater than 0.5 for all patients in the same PFS group. See Supplementary Table S3 for lists of specific gene members of each cluster group and enrichment scores. C, the pathways enriched for unique hypermethylated genes in PFS more than 6 months versus PFS less than 6 months, using the online gene functional analysis tool Pathway Express.

To further investigate the potential function of the differentially hypermethylated genes before (day 1) and after (day 8) decitabine administration, as well as their possible relationship to clinical responses, pathway enrichment analyses (Pathway-Express; ref. 23) was done. The most significant pathway in the patients with PFS more than 6 months was cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction (impact factor 14.6; Fig. 3C). Other signaling pathways enriched at baseline in PFS more than 6 months, included ABC transporter, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), toll-like receptor, and Jak-STAT signaling pathways. After decitabine treatment, one cluster (Src homology-3 domain) was enriched (geometric P values < 0.01) in tumors from patients with PFS more than 6 months (of 280 demethylated genes; Supplementary Fig. S3A), compared with 15 enriched clusters in patients with PFS less than 6 months (of 213 genes; Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Fig. S3A). The pathways most enriched with unique demethylated genes after decitabine in PFS more than 6 months were pathways in cancers, Wnt signaling pathway, apoptosis, and MAPK signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

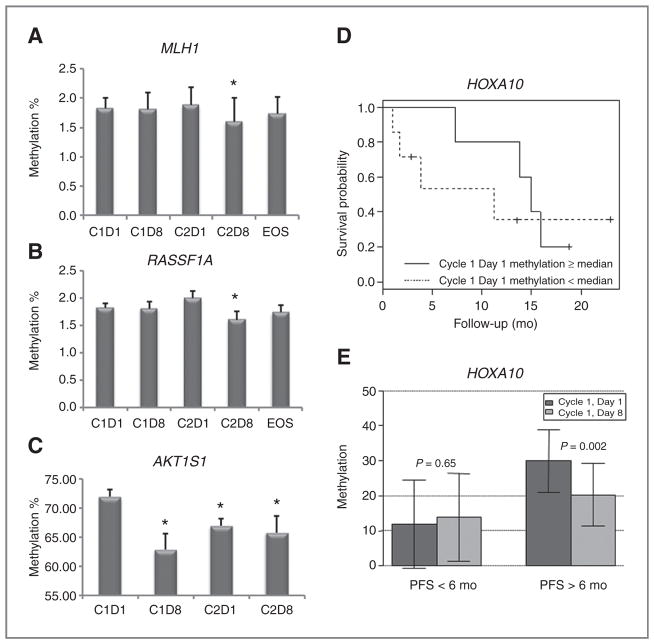

We also used pyrosequencing to assess methylation changes of specific ovarian cancer–associated genes in plasma (cell free) DNA (presumably shed by tumor cells; ref. 24) and tumors. Selection of specific genes was based on the Infinium array results and our previous studies (13–15), in addition to other reports describing their positive contributions to DNA damage–associated apoptosis and/or ovarian cancer prognosis/outcome (7, 25–27). Of the 12 genes examined (see Supplementary Table S2), demethylation of 2 tumor suppressors, MLH1, RASSF1A, was observed on cycle 2, day 8 (Fig. 4A and B). Although the magnitude of demethylation for the 2 genes is small, both reached statistical significance (P < 0.05). In addition, demethylation (P < 0.01) of AKT1S1, a subunit of the mTORC1 that regulates cell growth and survival, was seen on day 8 for both cycles (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, sustained AKT1S1 demethylation was apparent, as methylation levels on cycle 2 day 1 were lower (P < 0.01) compared with cycle 1 day 1.

Figure 4.

Specific ovarian cancer gene methylation levels. A, MLH1, showing plasma DNA demethylation after cycle 2, day 8 (C2D8); B, RASSF1A, similarly demethylated after C2D8; C, AKT1S1, demethylated after cycles 1, day 8 (C1D8), and 2, days 1 (C2D1) and 8 (C2D8), as measured by pyrosequencing on those specific cycles/days, and at end of study. D, baseline (pretreatment) methylation levels of HOXA10 in tumors or ascites, correlates with extended PFS. E, treatment-induced reduction of HOXA10 methylation levels in tumor biopsies, as correlated with patient PFS more than 6 months, versus patient PFS less than 6 months (P < 0.05). In A, B, C, and E, bars/error bars represent mean ± SD. *, P < 0.05.

We also correlated baseline and decitabine-altered tumor methylation levels for 5 genes in patients having a PFS of longer or shorter than 6 months. We observed demethylation of RASSF1A, AKT1S1, and MLH1 (in plasma), in all the patients, while decitabine demethylation of HOXA10 (Fig. 4E) and HOXA11 (Supplementary Fig. S4B) specifically correlated with a PFS more than 6 months (P < 0.05). Moreover, baseline tumor methylation levels for the tumor suppressor RASSF1A and the differentiation-associated genes HOXA10 and HOXA11 (from tumor/ascites) correlated with PFS more than 6 months (P < 0.05, Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. S3). These results pointed to a potential panel of genes that can be further studied as prognostic biomarkers for hypomethylating strategies in ovarian cancer.

Discussion

This phase II trial represents a proof-of-principle for the concept that epigenetic modulation restores sensitivity to platinum in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, resulting in significant clinical activity, as measured by high RR and prolonged PFS. Here, we show that these effects are modulated through DNA hypomethylation and identify candidate genes and methylation profiles correlating with clinical outcome. These findings justify further investigation of the current decitabine/carboplatin combination in ovarian cancer or other rationally designed epigenetic strategies in solid tumors.

Toxicities observed in this trial were mild and consistent with other studies testing hypomethylating agents. More pronounced rates of myelosuppression were recorded in previous trials examining decitabine-based combinations in lung (28), ovarian (29), and cervical cancer (30). We attribute the improved hematopoietic tolerance to the chosen schedule of low-dose decitabine administration (daily for 5 days) and to growth factor support provided in our study. Indeed, in recent studies for malignancies, the repeated low-dose strategy has shown improved tolerability as compared with bolus administration of higher decitabine doses (16, 17).

Consistent with our previous phase I trial, we observed a high rate of carboplatin hypersensitivity (36%). Most events consisted of flushing, rash, and mild respiratory distress, and responded to steroids and antihistaminics. Subsequent retreatment with carboplatin was possible by using slower rates of infusion and steroid premedication (31). Also, the rate of allergic reactions observed here appears higher than previously reported with reexposure to carboplatin (32), suggesting decitabine may elicit an immunologic response. Indeed, one hypothesis of allergy development is a failure to epigenetically silence fetal genes contributing to IgE synthesis and action, thus favoring Th2- over Th1-mediated immune responses (33). It has also been reported that hypomethylating agents could unmask antigens repressed in ovarian cancer (34), thus triggering immune reactions. Interestingly, among the pathways enriched with hypermethylated genes in patients achieving PFS more than 6 months, the toll-like receptor and the Jak-STAT pathways were identified (Fig. 3C). Although toll-like receptors play a critical role in innate immune responses and microbial defense (35), these proteins are potent mediators of inflammatory responses, activating oncogenic pathways such as NF-kB and MAPK (36). The Jak-STAT pathway mediates IFN-regulated events and antiproliferative responses, regulates cytokine signaling, and has been associated with drug resistance (37). Whether immune reactivation plays a role in the clinical activity of this regimen remains speculative.

The high clinical activity observed in our study is consistent with recently published results from a trial using the ribonucleoside analog, 5-azacytidine (Celgene) in combination with platinum. In that study (38), a higher dose (75 mg/m2/d) of the hypomethylating agent was administered, largely necessary because of diminished stability of azacytidine caused by additional incorporation into RNA. That combination induced a RR of 22% and a median PFS of 5.6 months. As treatment with single-agent carboplatin in this patient population induces only a small percentage of objective responses (<10%; ref. 39), which are generally short lived, our study and the recent report from Fu and colleagues (38) advance the concept and show that pretreatment with a hypomethylating agent could reverse platinum resistance in ovarian cancer.

In vivo biologic activity was shown by LINE1 and specific gene hypomethylation. Although LINE1 demethylation was clearly achieved in PBMCs, it did not correlate with tumor LINE1 methylation. We reasoned that tumor sampling may have occurred too early during treatment (cycle 1), with insufficient exposure to decitabine in the tumor milieu, as compared with the exposure of PBMCs. It is also possible that tumor LINE1 elements are less sensitive to demethylation, compared with PBMCs, given the lower percent methylation of LINE1 in the biopsy (Fig. 2A vs. Fig. 2B). Although PBMC DNA methylation may not be a reliable surrogate for tumor methylation (40), for one patient who remained on treatment with a sustained PR more than 2 years, continued hypomethylation of LINE1 was observed in PBMCs and ascites pellet at 2 years compared with baseline and earlier cycles (P < 0.01, not shown), suggesting that PBMC methylation has the potential to provide tumor-related information, in agreement with a previous study showing a distinct PBMC “epigenetic signature” for ovarian cancer (41).

The mechanism underlying restoration of platinum sensitivity by epigenetic intervention is probably linked to a complex signaling program (42). Our global DNA methylation analyses point to several pathways differentially methylated in patients who benefited from the regimen. Platinum response has been hypothesized to involve DNA damage leading to mitochondrial-activated apoptosis pathways. We observed demethylation of several genes associated with mitochondrial apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S2B), whose reexpression may associate with decitabine-mediated platinum resensitization. Another such pathway involves ABC transporters, membrane proteins that efflux chemically diverse compounds across the plasma membrane (43). ABC transporters have been implicated in the development of drug resistance in cancer cells (44). In this study, 6 ABC transporter genes (ABCA8, ABCA9, ABCB5, ABCC10, ABCG1, and ABCG4) were hypermethylated at baseline and after decitabine treatment in patients reaching a PFS more than 6 months, and this pathway was not identified as significantly hypermethylated in patients with PFS less than 6 months. These findings are in agreement with previous observation linking ABCG2 promoter hypomethylation to chemoresistance (45, 46).

Members of the MAPK family play a prominent role in sensitivity to chemotherapy in many cancers, including ovarian cancer (47), and 16 genes in the MAPK signaling pathway were hypermethylated in patients with PFS more than 6 months (Fig. 3). These results concur with previous ovarian cancer studies showing MAPK signaling as an inducer of the apoptosis-initiating Fas ligand, in response to cisplatin and other chemotherapeutics (48, 49). Indeed, we did observe significant demethylation of the FASLG in patients with PFS more than 6 months, in addition to other members of death receptor pathways, and correlations between FASLG expression and ovarian cancer chemoresponse have also been reported (50).

In summary, this study provides strong clinical and biologic evidence supporting further investigation of hypomethylating strategies in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. We identified a panel of decitabine-hypomethylated genes, pathways linked to chemotherapy response, and gene sets whose baseline methylation levels associate with clinical outcome. These data suggest that not one gene but rather complex genetic machinery involved in drug sensitivity/resistance mechanisms needs to be reactivated/deactivated to successfully enable resensitization of tumors to platinum. We show that this can be achieved in vivo by using decitabine, a global DNA hypomethylating agent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eisai Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) for providing decitabine, Mrs. Amber Allen, Carol Kulesavage, Nancy Menning, and Jessica Roy for coordination of clinical trial activities, Dr. C. Balch and S. Perkins for discussion, and Pieter Faber, PhD. (Director, Cleveland Clinic Genomics Core) for expert Infinium array advice.

Grant Support

This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute Awards CA133877, CA113001, CA85289 and the Walther Cancer Foundation, Indianapolis, IN.

Footnotes

This study was presented in part at the 2011 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

D. Matei and K.P. Nephew are consultants and on the advisory board of Supergen (now Astex Pharmaceuticals, Inc.).

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Bukowski RM, Ozols RF, Markman M. The management of recurrent ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:S1–15. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandercock J, Parmar MK, Torri V, Qian W. First-line treatment for advanced ovarian cancer: paclitaxel, platinum and the evidence. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:815–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei SH, Chen CM, Strathdee G, Harnsomburana J, Shyu CR, Rahmatpanah F, et al. Methylation microarray analysis of late-stage ovarian carcinomas distinguishes progression-free survival in patients and identifies candidate epigenetic markers. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2246–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton CA, Hacker NF, Clark SJ, O’Brien PM. DNA methylation changes in ovarian cancer: implications for early diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:129–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibanez de Caceres I, Battagli C, Esteller M, Herman JG, Dulaimi E, Edelson MI, et al. Tumor cell-specific BRCA1 and RASSF1A hypermethylation in serum, plasma, and peritoneal fluid from ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6476–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiegl H, Windbichler G, Mueller-Holzner E, Goebel G, Lechner M, Jacobs IJ, et al. HOXA11 DNA methylation–a novel prognostic biomarker in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:725–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balch C, Fang F, Matei DE, Huang TH, Nephew KP. Minireview: epigenetic changes in ovarian cancer. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4003–11. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabbour E, Issa JP, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H. Evolution of decitabine development: accomplishments, ongoing investigations, and future strategies. Cancer. 2008;112:2341–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samlowski WE, Leachman SA, Wade M, Cassidy P, Porter-Gill P, Busby L, et al. Evaluation of a 7-day continuous intravenous infusion of decitabine: inhibition of promoter-specific and global genomic DNA methylation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3897–905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plumb JA, Strathdee G, Sludden J, Kaye SB, Brown R. Reversal of drug resistance in human tumor xenografts by 2′-deoxy-5-azacytidine-induced demethylation of the hMLH1 gene promoter. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6039–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Hu W, Shen DY, Kavanagh JJ, Fu S. Azacitidine enhances sensitivity of platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cells to carboplatin through induction of apoptosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:177, e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balch C, Yan P, Craft T, Young S, Skalnik DG, Huang TH, et al. Antimitogenic and chemosensitizing effects of the methylation inhibitor zebularine in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1505–14. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Balch C, Montgomery JS, Jeong M, Chung JH, Yan P, et al. Integrated analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression reveals specific signaling pathways associated with platinum resistance in ovarian cancer. BMC Med Genomics. 2009;2:34. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang F, Balch C, Schilder J, Breen T, Zhang S, Shen C, et al. A phase 1 and pharmacodynamic study of decitabine in combination with carboplatin in patients with recurrent, platinum-resistant, epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:4043–53. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarjian H, Oki Y, Garcia-Manero G, Huang X, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Results of a randomized study of 3 schedules of low-dose decitabine in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:52–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appleton K, Mackay HJ, Judson I, Plumb JA, McCormick C, Strathdee G, et al. Phase I and pharmacodynamic trial of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor decitabine and carboplatin in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4603–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matei DE, Nephew KP. Epigenetic therapies for chemoresensitization of epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffy MJ, Bonfrer JM, Kulpa J, Rustin GJ, Soletormos G, Torre GC, et al. CA125 in ovarian cancer: European Group on Tumor Markers guidelines for clinical use. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:679–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tost J, Gut IG. DNA methylation analysis by pyrosequencing. Nat Protocol. 2007;2:2265–75. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Draghici S, Khatri P, Tarca AL, Amin K, Done A, Voichita C, et al. A systems biology approach for pathway level analysis. Genome Res. 2007;17:1537–45. doi: 10.1101/gr.6202607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan KC, Lo YM. Circulating tumour-derived nucleic acids in cancer patients: potential applications as tumour markers. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:681–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton G, Yee KS, Scrace S, O’Neill E. ATM regulates a RASSF1A-dependent DNA damage response. Curr Biol. 2009;19:2020–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin LP, Hamilton TC, Schilder RJ. Platinum resistance: the role of DNA repair pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1291–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bromer JG, Wu J, Zhou Y, Taylor HS. Hypermethylation of homeobox A10 by in utero diethylstilbestrol exposure: an epigenetic mechanism for altered developmental programming. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3376–82. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartsmann G, Schunemann H, Gorini CN, Filho AF, Garbino C, Sabini G, et al. A phase I trial of cisplatin plus decitabine, a new DNA-hypomethylating agent, in patients with advanced solid tumors and a follow-up early phase II evaluation in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2000;18:83–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1006388031954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glasspool RM, Gore M, Rustin G, McNeish I, Wilson R, Pledge S, et al. Randomized phase II study of decitabine in combination with carboplatin compared with carboplatin alone in patients with recurrent advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pohlmann P, DiLeone LP, Cancella AI, Caldas AP, Dal Lago L, Campos O, Jr, et al. Phase II trial of cisplatin plus decitabine, a new DNA hypomethylating agent, in patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:496–501. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200210000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee CW, Matulonis UA, Castells MC. Carboplatin hypersensitivity: a 6-h 12-step protocol effective in 35 desensitizations in patients with gynecological malignancies and mast cell/IgE-mediated reactions. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:370–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gadducci A, Tana R, Teti G, Zanca G, Fanucchi A, Genazzani AR. Analysis of the pattern of hypersensitivity reactions in patients receiving carboplatin retreatment for recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:615–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teitell M, Richardson B. DNA methylation in the immune system. Clin Immunol. 2003;109:2–5. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00224-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woloszynska-Read A, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Yu J, Odunsi K, Karpf AR. Intertumor and intratumor NY-ESO-1 expression heterogeneity is associated with promoter-specific and global DNA methylation status in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3283–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barton GM, Kagan JC. A cell biological view of Toll-like receptor function: regulation through compartmentalization. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:535–42. doi: 10.1038/nri2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrc2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carmo CR, Lyons-Lewis J, Seckl MJ, Costa-Pereira AP. A novel requirement for Janus kinases as mediators of drug resistance induced by fibroblast growth factor-2 in human cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu S, Hu W, Iyer R, Kavanagh JJ, Coleman RL, Levenback CF, et al. Phase 1b-2a study to reverse platinum resistance through use of a hypomethylating agent, azacitidine, in patients with platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1661–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.See HT, Freedman RS, Kudelka AP, Burke TW, Gershenson DM, Tangjitgamol S, et al. Retrospective review: re-treatment of patients with ovarian cancer with carboplatin after platinum resistance. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:209–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.15205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart DJ, Issa JP, Kurzrock R, Nunez MI, Jelinek J, Hong D, et al. Decitabine effect on tumor global DNA methylation and other parameters in a phase I trial in refractory solid tumors and lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3881–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teschendorff AE, Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ramus SJ, Gayther SA, Apostolidou S, et al. An epigenetic signature in peripheral blood predicts active ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glaysher S, Gabriel FG, Johnson P, Polak M, Knight LA, Parker K, et al. Molecular basis of chemosensitivity of platinum pre-treated ovarian cancer to chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:656–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shukla S, Ohnuma S, Ambudkar SV. Improving cancer chemotherapy with modulators of ABC drug transporters. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:621–30. doi: 10.2174/138945011795378540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahadevan D, Shirahatti N. Strategies for targeting the multidrug resistance-1 (MDR1)/P-gp transporter in human malignancies. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5:445–55. doi: 10.2174/1568009054863609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calcagno AM, Fostel JM, To KK, Salcido CD, Martin SE, Chewning KJ, et al. Single-step doxorubicin-selected cancer cells overexpress the ABCG2 drug transporter through epigenetic changes. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1515–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bram EE, Stark M, Raz S, Assaraf YG. Chemotherapeutic drug-induced ABCG2 promoter demethylation as a novel mechanism of acquired multidrug resistance. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1359–70. doi: 10.1593/neo.91314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan JK, Pham H, You XJ, Cloven NG, Burger RA, Rose GS, et al. Suppression of ovarian cancer cell tumorigenicity and evasion of Cisplatin resistance using a truncated epidermal growth factor receptor in a rat model. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3243–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu W, Jin C, Lou X, Han X, Li L, He Y, et al. Global analysis of DNA methylation by Methyl-Capture sequencing reveals epigenetic control of cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cell. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duiker EW, van der Zee AG, de Graeff P, Boersma-van Ek W, Hollema H, de Bock GH, et al. The extrinsic apoptosis pathway and its prognostic impact in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:549–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.