Abstract

Cortical sensorimotor (SM) maps are a useful readout for providing a global view of the underlying status of evoked brain function, as well as a gross overview of ongoing mechanisms of plasticity. Recent evidence in the rat controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury model shows that the ipsilesional (injured) hemisphere is temporarily permissive for axon sprouting. This would predict that size and spatial alterations in cortical maps may occur much earlier than previously tested and that they might be useful as potential markers of the postinjury plasticity period as well as indicators of outcome. We investigated the evolution of changes in brain activation evoked by affected hindlimb electrical stimulation at 4, 7, and 30 days following CCI or sham injury over the hindlimb cortical region of adult rats. [14C]-iodoantipyrine autoradiography was used to quantitatively examine the local cerebral blood flow changes in response to hindlimb stimulation as a marker for neuronal activity. The results show that although ipsilesional hindlimb SM activity was persistently depressed from 4 days, additional novel regions of ipsilesional activity appeared concurrently within SM barrel and S2 regions as well as posterior auditory cortex. Simultaneously with this was the appearance of evoked activity within the intact, contralesional cortex that was maximal at 4 and 7 days, compared to stimulated sham-injured rats, where activation was solely unilateral. By 30 days, however, contralesional activation had greatly subsided and existing ipsilesional activity was enhanced within the same novel cortical regions that were identified acutely. These data indicate that significant reorganization of the cortical SM maps occurs after injury that evolves with a particular postinjury time course. We discuss these data in terms of the known mechanisms of plasticity that are likely to underlie these map changes, with particular reference to the differences and similarities that exist between rodent models of stroke and traumatic brain injury.

Key words: autoradiography, blood flow, cortical contusion injury, plasticity

Introduction

In addition to the well-known cognitive deficits that result from traumatic brain injury (TBI), motor weakness in limb or trunk is a major problem in both adult and young patients,1,2 even after mild concussive trauma.3 Motor deficits can persist for many years, despite neurorehabilitative interventions.4 Although the prolonged time course of recovery holds promising opportunities for therapeutic intervention, the spontaneous restorative processes occurring in the brain after TBI are not completely understood. Mechanisms for the partial motor recovery that occurs after TBI are complex, but are likely to include behavioral compensation as well as anatomical and functional reorganization of the remaining intact brain. These cellular and molecular mechanisms of plasticity underlie changes in somatosensory and motor cortical map representations that occur after injury. Though much of our understanding of these map changes comes from stroke and experimental lesion models, comparatively little progress has been made in the TBI field. Much of this stems from the disparities in injury location between the diseases; TBI is primarily a disparate white matter disease where, instead of functional deficits arising from focal injury sites as occurs in stroke, whole networks can be affected,5 making it difficult to study systematically. The pathology of TBI is heterogeneous and complex, involving multi-faceted pathologies that reflect the diverse effects of the initial mechanical injury as well as subsequent secondary events. Indeed, the cascade of pathophysiological changes often lasts longer after a diffuse TBI than after focal ischemia.6 As a result, the known patterns and mechanisms of plasticity that occur after stroke or lesioning may not be entirely transferable to the TBI field. Though neuronal sprouting and synapse formation occur around focal cortical infarcts and in sensorimotor cortex of the unaffected hemisphere,7–10 axon sprouting is limited to the pericontused region after experimental TBI and none occurs in the intact cortex.11 Both experimental and clinical neuroimaging studies after unilateral stroke have shown functional reorganization in both the ipsilesional (injured) and the contralesional (intact) hemisphere in parallel with recovery.12,13 After TBI, although chronic time-point ipsilesional cortical somatosensory map changes occur after experimental contusion injury and may be related to functional recovery,14–16 activation in the contralesional hemisphere has only been shown chronically after very severe contusion injury17 and its role in recovery is unknown. Occurrence of spontaneous, ipsilesional axonal plasticity within the first 2 weeks after TBI,11 as well as temporary expression of indirect markers of new neuronal connections, such as growth-associated protein 43, microtubule-associated proteins, and polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule,18 imply the existence of an earlier, temporary post-traumatic reorganizational state within the brain. This altered state would predict that important cortical map changes occur earlier than previously studied. The eventual postinjury accumulation of growth-inhibitory proteins that mark the end of the growth-promoting period19 would also predict that further map changes may be stymied, reflecting a reassertion of the normal growth-inhibitory environment of the brain. A determination of how these map changes evolve after TBI is important to determine how future interventional studies may be used to either stimulate or inhibit brain function to promote functional recovery.

In the current study, we have used the controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury rat model, as implemented by us,20 to investigate the evolution of changes in brain activation after injury over the hindlimb cortical area. 14C iodoantipyrine (IAP) autoradiography was used to examine the relative local cerebral blood flow (LCBF) changes in response to hindlimb stimulation as a marker for neuronal activity. Here, we present novel findings on temporospatial mappings of the reorganizational response, a hitherto under-reported phenomenon after brain trauma, given the importance of the brain's endogenous regenerative potential as a therapeutic target for further enhancement.

Methods

Experimental protocol

Mild electrical stimulation of the affected (right) hindlimb was used to evoke cerebral activation and was detected by the autoradiographic analysis of the increased LCBF at 4, 7, and 30 days after CCI injury over the left hindlimb, sensory motor cortex (n=5/group), or after sham injury (n=3) of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–300 g body weight). An additional sham group that was not stimulated (n=3) served as a control group to determine a brain region in stimulated animals, where LCBF remained unaffected by stimulation, for use as a normalization region for determining a threshold for increased LCBF. A pilot laser Doppler (LD) cerebral blood flow study was performed in naïve rats (n=3) to determine optimal stimulation parameters for brain activation. All study protocols were approved by the UK Animals Scientific Procedures Act (1986).

Pilot study for determining optimal stimulation parameters

Naïve rats were anaesthetised with 3% isoflurane vaporized in 70% nitrous oxide/30% oxygen and then maintained with 2% isoflurane during surgery. Rats were positioned in a stereotaxic frame, after which a dental trephine drill was used to make a 5-mm craniotomy over the left parietal cortex, 0.5 mm posterior to the coronal suture and 3 mm lateral to the sagittal suture. Using the same α-chloralose sedation anesthesia protocol as used for functional activation (see below), mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was continuously monitored through the femoral artery, and an LD flowmetry probe (needle-shaped, 0.8 mm), mounted on a micromanipulator and connected to an LD blood-perfusion monitor, was used to monitor LCBF. Care was taken to obtain flow readings only from areas free of large pial vessels. LCBF changes were calculated relative to baseline, defined as the average flow for 3 sec before stimulation. Then, stimulation intensity applied to the hindlimb (see below) was increased from 2 V in steps of 2 V for 1 min and 30 sec. Between each stimulation intensity run, a rest period of 3 min was allowed, during which time the LCBF returns to baseline. Blood gases were measured 20 min after administration of α-chloralose and during the period of stimulation.

Brain injury

Rats were placed under surgical isoflurane anesthesia as described above. The method for induction of CCI injury was performed in the manner described previously.20–22 Briefly, after reduction of anesthesia to 1.0–1.5% isoflurane and 0.8/0.4 L/min of N2O/O2, a 2.5-mm-diameter piston was advanced through a 5-mm craniotomy at −0.5 mm posterior to Bregma and 3 mm left-lateral to the sagittal suture and onto the brain at 4 m/sec to a deformation depth of 2 mm below the dura. The bone flap was immediately replaced and sealed, and the scalp was sutured-closed. Rats were placed in a heated cage to maintain body temperature while recovering from anesthesia and soluble paracetamol (1 mg/mL; Cox Pharmaceuticals, Barnstaple, UK) was administered in the drinking water postoperatively.

Functional autoradiography

Under surgical isoflurane anesthesia as before, rats were tracheotomized and then artificially ventilated (Harvard Apparatus, Maidstone, UK) with 1.5% isoflurane in 70% nitrous oxygen/30% oxygen. The left femoral artery was cannulated for monitoring of arterial blood gases and periodic plasma sampling, and the right femoral vein was cannulated for administration of anesthetic agents and isotope infusion. A small-needle electrode was inserted subcutaneously (s.c.) on the right hindpaw, from the medial globular pads extending distally toward the limb. The indifferent electrodes were inserted s.c. at the chest. Tidal volume and ventilation rate were adjusted to maintain normal blood chemistry, and body temperature was kept constant at 37±0.5°C with a homeothermic-controlled heating pad (Harvard Apparatus). Rats were paralyzed by an intravenous (i.v.) bolus of pancuronium (0.6 mg/kg; Organon International, Newhouse, UK), followed by continuous i.v. infusion (0.6 mg/kg/h). Isofluorane anesthsesia was replaced with α-chloralose sedation (50 mg/kg, bolus i.v. infusion; Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) to prevent the blunting effect of isoflurane on brain activation. Continuous affected (right) hindlimb stimulation was initiated for a 20-min period after discontinuing isoflurane to allow the effects of the isofluorane to dissipate. An optimal stimulation intensity of 8 V (Fig. 1A,B; see Results) with a frequency of 5 Hz and stimulation duration of 0.5 sec was given. Stimulation was begun 30 sec before the beginning of isotope infusion for LCBF autoradiography and continued throughout the measurement of blood samples until the brain was frozen. Autoradiography was performed as described previously21,22; briefly, 925 KBq of IAP (Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK) was infused i.v. over 60 sec using a ramped infusion, and arterial blood samples were collected onto a filter paper every 3 sec. After decapitation, the brain was rapidly excised, frozen in dry ice-cooled isopentane, and subsequently sectioned at 20 μm in a cryostat. Brain and plasma IAP concentration were determined using a phosphor imager (Cyclone; PerkinElmer Life Sciences Ltd., Cambridge, UK) and calibrated 14C standards (Amersham PLC, Little Chalfont, UK), as described previously.21,22 Blood gases were measured 20 min after administration of α-chloralose, during the period of stimulation.

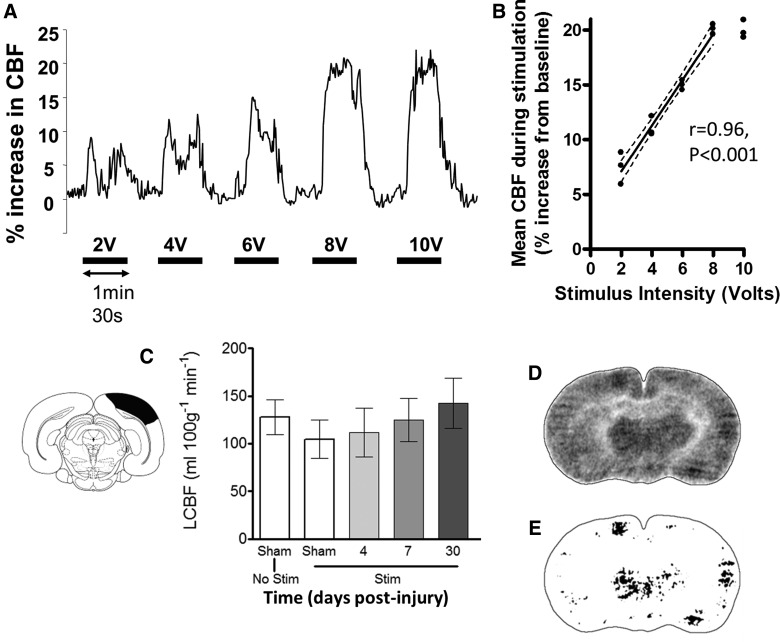

FIG. 1.

(A) Representative laser Doppler flowmetry trace of cerebral blood flow (CBF) from the left hindlimb sensorimotor cortex of a naïve rat showing recorded increases in CBF during periods of electrical stimulation of the contralateral (right) hindlimb. (B) CBF increased linearly with stimulus intensity from 2 V to a maximum of 20% above baseline at 8 V (filled circles are individual values from 3 naïve rats; dotted lines represent 95% confidence limits). There was no further increase in CBF at 10 V, compared to 8 V (p>0.05), and so 8 V was used in all autoradiographic experiments. (C) Local CBF (LCBF) values obtained by autoradiography did not vary significantly with stimulation in a cortical region at −6.8 mm posterior to Bregma, as indicated graphically by the absence of LCBF changes between sham-injured unstimulated (No Stim; n=3), sham-injured stimulated (Stim; n=3), and stimulated brain-injured rats (p>0.05; n=5/group). This region was used as a baseline from which to interrogate images for LCBF changes >2 standard deviations (SDs) for assessment of regions of brain activation (see Methods). (D) A representative LCBF image from a sham-injured rat analyzed for regions of cortical activation and (E) the result of applying a threshold LCBF that is 2 SDs above baseline values in cortex unaffected by stimulation at −6.8mm from Bregma. Data are plotted as means±standard error of the mean.

Image analysis

Brain tissue and plasma isotope concentration images of IAP were used to calculate parametric images of LCBF, as described previously.21,22 To systematically define the region of brain exhibiting increased LCBF as an indicator of brain activation within each brain, the number of pixels was determined with LCBF values greater than 2 standard deviations (SDs) above posterior cortical mean LCBF values at −6.80 mm from Bregma and ipsilateral to the stimulated limb (Fig. 1C), a region where LCBF remains unaffected by the stimulation (see Results). The analysis was performed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD),23 which was also used to calibrate and scale the images and convert the “activated” pixel numbers to area measurements. Three coronal sections corresponding to Bregma −1.30, −2.3, and −5.8 mm were analyzed per brain, and the sum of each activated brain region for ipsi- and contralesional hemispheres was computed. The rationale for the choice of section levels was based upon the two anterior sections containing hindlimb S1 cortex as well as the likelihood of observing new activations within the posterior cortex, as indicated by initial pilot autoradiographic data. Mean LCBF was obtained from each activated region to test for differences in degree of LCBF enhancement. The ratio of bilateral hemispheric activation was calculated and expressed as a laterality index for each section by computing the following equation: ipsilesional area−contralesional area/ipsilesional area+contralesional area.

Statistical analysis

Kolmogorov-Smirnov's test with Lillie's correction and Levene's median test were used to describe distribution of data and determine equality of variances, respectively. Having passed these normality tests, group numerical data were expressed as the means±standard error of the mean. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare physiology data. A two way-way ANOVA (group×region) was used to compare sham- and trauma-group autoradiographic data. Because there were no differences among the different levels of region (anteroposterior level) for any group data, a one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by a Student's/Newman-Keuls' post-hoc method to test for any significant differences among the groups. The laterality index data failed the normality test, and so an ANOVA on ranks was performed, followed by Dunn's method for pairwise multiple comparison procedure. As a result, laterality data are plotted as medians, 25th and 75th percentiles, and minimum/maximum values in a box-and-whiskers plot. Difference between the means were assessed at the probability levels p<0.05, 0.01, and 0.001.

Results

A pilot experiment using LD flowmetry in 3 naïve rats was initially performed to determine the optimal stimulation parameters for the autoradiographic experiment. There was a linear increase in cerebral blood flow with increasing hindlimb stimulation intensity from 2 V to a maximal 20% change from baseline at 8 V intensity (r=0.96; p<0.001; Fig. 1A,B). No further significant increase was noted at 10 V, and therefore an 8 V stimulus was taken as the optimal intensity and was used for all further experiments. Plasma chemistry values were within normal limits both before and after stimulation, and there was no significant increase in MAP above baseline during the stimulation (Table 1), indicating that the stimulus was not perceived as noxious.24

Table 1.

Physiological Data in Naïve Rats

| Before stimulation | During stimulation | |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.43±0.04 | 7.42±0.01 |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 136.5±6.5 | 130.8±4.5 |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 40.3±2.3 | 41.1±2.8 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 111±1.5 | 113±1.4 |

Values are expressed as the mean±standard error of the mean.

MAP, mean arterial pressure.

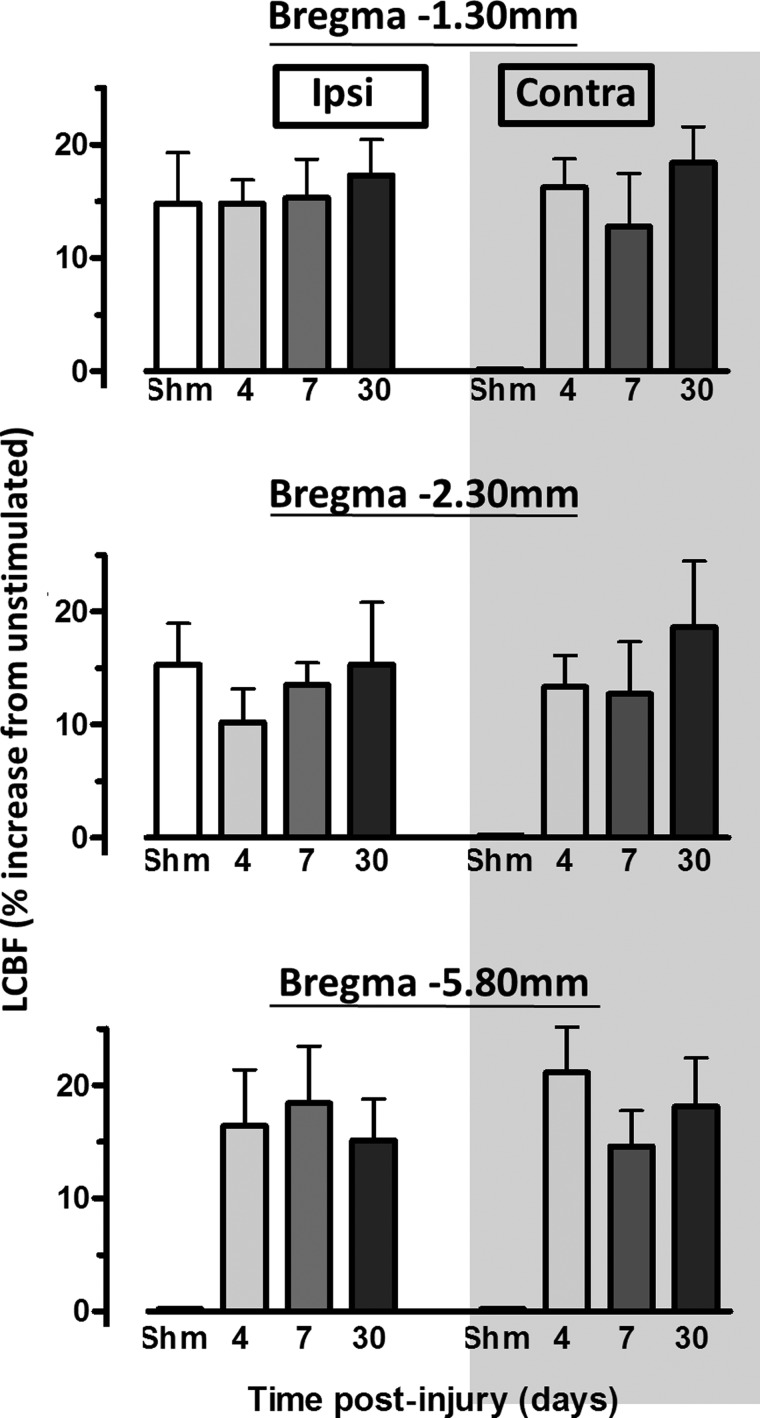

Injured and sham control rats exhibited stable physiological variables, and there was no significant difference between these groups (Table 2). Analysis of LCBF values in a cortical region of interest within the contralesional (opposite to the injury) visual cortex at Bregma −6.80 mm in nonstimulated and hindlimb-stimulated rats showed that the region LCBF remained unaffected by the stimulation paradigm in all groups, compared to unstimulated sham animals (p>0.05; Fig. 1C). As a result, this region was used within each brain to determine the global cortical LCBF threshold, which was greater than 2 SDs above mean baseline LCBF, to systematically determine the region of activation within each cortex (Fig. 1D,E). The mean LCBF within the activated regions was generally between 10 and 20% above baseline LCBF values (Fig. 2). Detectable increases in LCBF above baseline were only observed in sham-injured brains within left cortical regions at Bregma −1.30 and 2.30 mm opposite to the stimulated limb and not in posterior regions at Bregma −5.80 mm, or in right cortical regions ipsilateral to the stimulated limb. In injured brain, the amplitude of the LCBF change at 2 SDs above baseline was not significantly different to sham values or among any other region with raised LCBF in injured brain. However, as indicated below, although LCBF remained unaltered in brain regions normally activated in sham-injured rats (Fig. 3), LCBF increased within additional cortical areas, in posterior ipsilesional regions, at all anteroposterior levels on the contralesional cortex, and at all times examined after injury. These values are plotted against LCBF values obtained from more anterior-activated regions in sham animals (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Physiological Data During Hindlimb Stimulation in Rats After TBI or Sham Injury

| |

|

TBI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham control | Day 4 | Day 7 | Day 28 | |

| pH | 7.43±0.07 | 7.42±0.03 | 7.42±0.05 | 7.55±0.03 |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 153.5±21.5 | 136.8±12.5 | 135.8±20.4 | 140.0.8±22.9 |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 40.3±6.7 | 44.0±2.8 | 39.8±8.7 | 36.7±2.5 |

Values are expressed as the mean±standard error of the mean.

TBI, traumatic brain injury.

FIG. 2.

Plots of percent increases in local cerebral blood flow (LCBF) above baseline, unstimulated cortex from activated brain regions that were obtained by image analysis of autoradiographic section images at three anteroposterio levels (see Methods). Cortical LCBF increases were consistently between 10 and 20% above baseline and this did not differ significantly across section levels or between sham (shm) and injured groups (p>0.05). However, in injured rats, detectable increases in evoked LCBF occurred in cortical regions that were not observed in sham animals, in all contralesional regions as well as bilateral posterior regions at Bregma −5.80 mm.

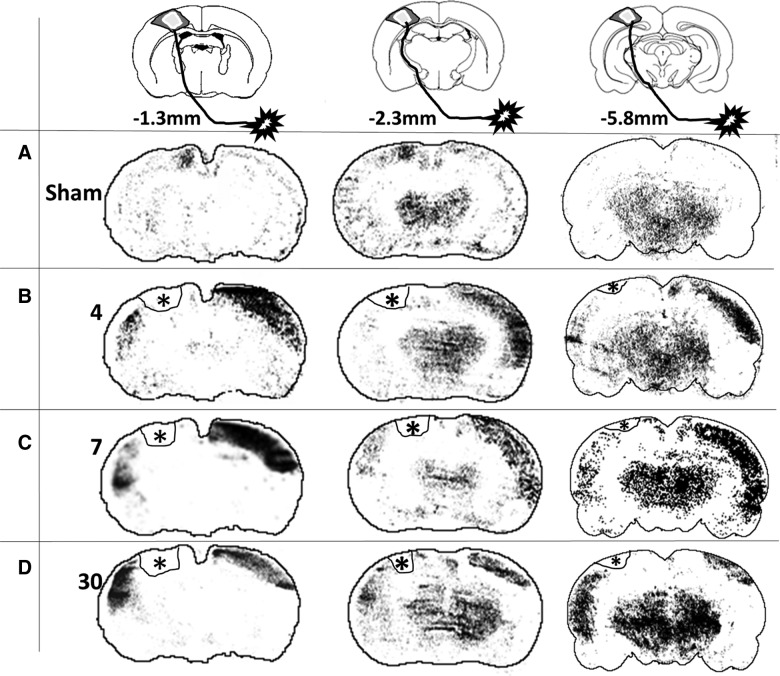

FIG. 3.

Representative images of local cerebral blood flow (LCBF) autoradiographic coronal sections at three different anteroposterior levels that were acquired during electrical stimulation of the affected (right) hindlimb in (A) a sham-injured rat and injured rats at (B) 4, (C) 7, and (D) 30 days after injury. Images were systematically processed (see Methods) to determine the region of increased LCBF corresponding to brain activation (above an unaffected posterior baseline region) and superimposed on the approximate outline of the corresponding atlas section. Hyperintense areas represent LCBF values that are >2 standard deviations above a posterior cortical region unaffected by the stimulation. Asterisk represents the location of the impact injury, which has been outlined on these images.

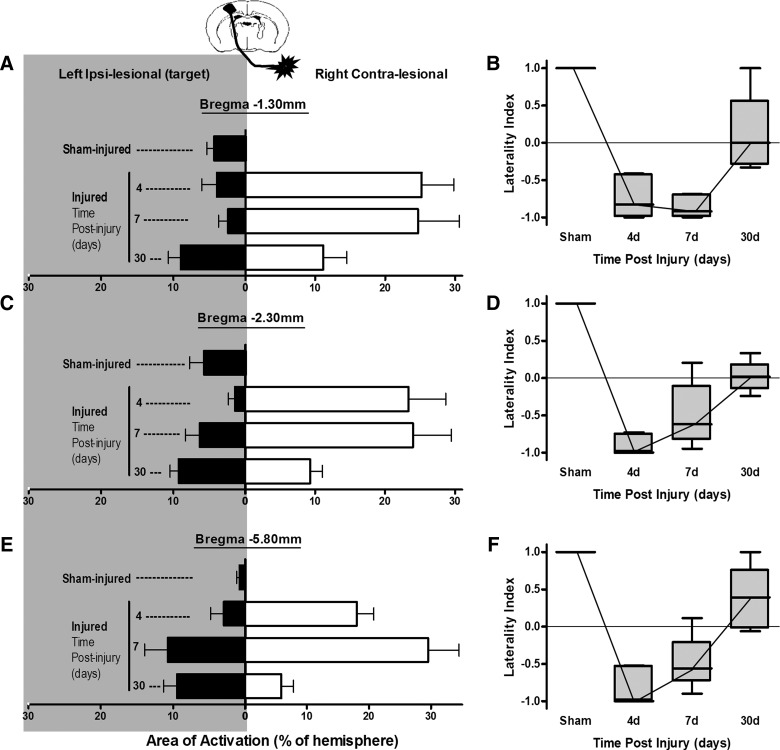

As expected, stimulation of the right hindlimb in sham-injured animals resulted in activation within the hindlimb region of the left sensory-motor/primary motor cortex (S1HL/M1) contralateral to the stimulated hindlimb at −1.3 and −2.3 mm from Bregma (Fig. 3A). No activation was observed in the opposite, right hemisphere and none was present in either hemisphere at −5.8 mm, which is outside of the hindlimb sensorimotor representation. As a result of this unilateral activation, sham-group laterality index values, a measure of the degree of bilateral activation, were +1 in all regions examined (Fig. 4B,D,F). Stimulation of the right (affected) hindlimb at 4 days after injury did not result in left, ipsilesional S1HL/M1 cortical activation (Fig. 2B). This pattern of decreased volume of activation was noted not only in the contusion core over the S1HL region, but also in the cortical areas posterior to the injury site at −2.3 mm from Bregma. Despite this, however, there were new areas of ipsilesional cortex activation, which were primarily located lateral and ventral to the S1HL sensorimotor cortex within the whisker barrel and S2 cortical regions, so that the total summed areas of ipsilesional activation were not different from sham-injured animals at any anteroposterior level at 4 days (p>0.05; Fig. 4A,C,E). Clear activation responses were also detected in the opposite, contralesional hemisphere (i.e., ipsilateral to the stimulated paw) that were similar among all anteroposterior levels examined (p>0.05 effect of region; two-way ANOVA), compared to stimulated sham-injured rats, where no contralesional activation was present (Figs. 3B and 4A,C,E). These areas of activation involved various cortical regions, including areas that are not normally involved in sensorimotor function of the hindlimb (e.g., barrel field, forelimb, and auditory cortex regions). As a result, the laterality index was significantly decreased and negative at all anteroposterior levels analyzed, compared to sham (p<0.05, ANOVA on ranks; Fig. 4B,D,F). Although subcortical regions also appeared to be activated, the regions were not delineated robustly and reproducibly enough among animals, indicating that the baseline cortical LCBF values used to determine a significant increase in LCBF were not appropriate for determining activation in other brain regions.

FIG. 4.

Plots of right (affected) hindlimb evoked, ipsilesional (closed bars), and contralesional (open bars) cortical activation areas (A, C, and E) and the corresponding laterality index (B, D, and F] quantified on local cerebral blood flow autoradiographic images at three anteroposterior levels from Bregma (A and B) −1.30 (C and D), −2.30, and (E and F) −5.80 mm in sham- and brain-injured rats at 4, 7, and 30 days after injury. There was no effect of anteroposterior region examined for any parameter (p>0.05; two-way ANOVA), and so group comparison statistics are pooled and are therefore not shown on the individual region plots for clarity. (A, C, and E) Activation area data are plotted as mean±standard error of the mean. There was a significant increase in both ipsilesional activation area at 30 days versus sham (p<0.01) and contralesional area at 4, 7, and 30 days versus sham (p<0.05). (B, D, and F) Laterality index, non-normally distributed data are plotted as median, 25th and 75th percentiles, and minimum/maximum values. A group analysis for pooled regions with a one-way ANOVA on ranks showed a significantly decreased laterality index at 4 and 7 days versus sham (p<0.05), but a significant rise at 30 days, compared to 4 and 7 days (p<0.05), that was overall not different from sham (p>0.05).

The regions of new ipsilesional activation (whisker barrel and S2 cortex) that were present at 4 days postinjury remained activated at 7 days (Fig. 3C) and did not differ among region examined (p>0.05, two-way ANOVA, region effect). Although the areas of ipsilesional activation were larger and approached significance, compared to 4 days (p=0.054, two-way ANOVA, group effect; Fig. 4A,C,E), there was no effect on the laterality index, compared to 4 days (p>0.05), and it remained significantly decreased and negative, compared to the sham-injured group, at all anteroposterior levels (p<0.05, ANOVA on ranks; Fig. 4B,D,F).

Novel areas of ipsilesional activation remained within whisker barrel, S2 cortex (−1.3 and −2.3 mm Bregma), and auditory cortex (−5.8 mm Bregma; Fig. 3D) at 30 days after injury, and these were significantly greater in size, compared to either sham or the 4-day injured groups (p<0.01; Fig. 4A,C,E). However, although contralesional activation remained, it was significantly smaller in size, compared to at 4 and 7 days postinjury (p<0.001), although it was still larger, compared to sham-injured values, where only unilateral activation was present (p<0.05; Fig. 4A,C,E). As a result, the laterality index at 30 days postinjury was positive or at zero in all regions examined, which, over all regions combined, was not significantly different from sham levels (p>0.05, ANOVA on ranks; Fig. 4B,D,F). Clearly, however, the continued presence of some contralesional activation among some rats at 30 days postinjury resulted in variation in the laterality index, indicating that it was not yet completely normalized.

Discussion

Cortical contusion injury resulting in a lesion over the ipsilateral M1/S1HL sensorimotor cortex was associated with loss of brain activity in these areas. The most novel finding from this study is that there was a shift in brain activation response from its normal position within the lesioned hemisphere to the opposite, contralesional hemisphere. At later times after trauma, this was followed by a shift back to the perilesional cortex, albeit to a different brain region, and some contralesional activation remained.

We measured activation responses by use of IAP autoradiography, which enables us to assess changes in neuronal activity through the measurement of cerebral blood flow (CBF) variations. The use of CBF as an index of neuronal activity is based on the presupposed tight coupling between neuronal activity, metabolism, and CBF.25 Indeed, several experimental studies have reported a positive linear correlation between electrophysiological and CBF responses.26,27 The presence of increased LCBF that was limited to hindlimb regions contralateral to the stimulated limb in sham rats in the current study suggests that the protocol used in the experiments was responsive to intact coupling neurovascular coupling.

Ipsilesional M1/S1HL cortical activation is depressed acutely

The absence of activation from within the normal injured M1/S1HL sensorimotor region at Bregma −1.30 mm at 4 days persisted at all times after injury, and this has been reported at even more chronic times after severe CCI injury.17 The mid-line/anterior region containing motor and at least some S1 cortex remains intact, despite the nearby cavity (Fig. 2), as we have shown previously in the same model using histology,20 indicating it is not the merely the destruction of tissue that results in inactivation. The status of neurovascular uncoupling in this model is not known, but sensory-evoked potentials are initially absent after acceleration concussion in the rat, after which they are present, but much reduced,28 so that coupling is likely to be intact by 4 days postinjury in this study. However, there are early perturbations in metabolism and CBF that result in metabolic uncoupling after CCI injury,21,29 so that the brain may be unable to respond to limb stimulation. Further, there is ample evidence of ionic and/or neurotransmitter perturbations after brain injury in the rodent,30,31 which are also likely to have contributed to the depressed activation in this study. Therefore, at least acutely, the failure of LCBF increase within the ipsilesional cortex might be the result of altered neurovascular coupling after TBI.

The persistent absence of ipsilesional M1/S1HL activation at more chronic postinjury times is similar to the failure to observe whisker-deflected cortical activation for almost 2 months after fluid percussion injury.16 The absence of activation after CCI injury occurs when cerebral glucose metabolism has normalized in this model,32 which suggests that either the region has become irreversibly damaged from ensuing tissue atrophy or other local injury mechanisms, or that the region has become chronically disconnected. Disconnection is more likely, because the injured ipsilesional cortex can, in fact, be locally activated by direct stimulation after fluid percussion injury.33 Ongoing intra- and intercortical and corticothalamic denervation has been shown to be rather more widespread than merely affecting the contused region after rodent CCI injury,34,35 and axonal damage and disconnection underlying the contusion and mid-line region is evident at this level of injury in this model.22 Even after more mild CCI injury, there is a persistent reduction in both callosal,36 as well corticospinal, fiber tracks, as assessed by diffusion tensor imaging,37 suggesting that ongoing inactivation of gray matter is consistent with deficits in connectivity to other relay centers within the central nervous system (CNS).

Ipsilesional activation increases in novel regions chronically

Despite the disappearance of activation within S1HL regions, ipsilesional activation was clearly evident very soon postinjury within lateral S2 and barrel cortical regions as well as more remote ipsilesional auditory regions at −5.80 mm from Bregma. This is different from rodent stroke models of middle cerebral artery occlusion, where ipsilesional activation is reduced or absent until more chronic times,13 and more similar to changes observed after targeted ministrokes.38 The sudden appearance of these new regions of activation largely negates the idea that any structural changes are responsible. However, representative autoradiograms (Fig. 3) do show that these regions persist and even enlarge over time, implying that immediate ipsilesional map reorganization is not simply the result of mechanisms governing short-term plasticity, such as temporary changes in receptor densities and/or long-term potentiation- and depression-type mechanisms. Map changes occur even within the first hour after stroke,38 presumably the result of unmasking of existing horizontal circuits.39 We have observed similar activation patterns as those described herein using forelimb-evoked blood-oxygen-level–dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging before and after rat CCI injury40 and with functional micropositron tomography of fluordeoxyglucose uptake (N.G. Harris, unpublished observations, November 2012), so that they cannot be simply regarded as methodological artefacts. Spontaneous axonal sprouting does occur within the ipsilesional cortex in this model over the first 3 weeks,11 which may well aid in stabilization of the cortical map changes consolidating the circuit rearrangements. The stimulation protocol employed here is likely to have activated most of the nerves contained within the proximal hindpaw and their branches, so that both sensory and motor representations are observed, as reported for forelimb.41 Therefore, the new ipsilesional activation may equally represent changes in both afferent (sensory) input as well as efferent (motor) output, because the latter activation will occur through antidromic nerve conduction.42 In fact, motor control by sensory cortex has been shown to occur in rodent sensory barrel cortex,43 so that it is plausible that the novel activations do represent both systems and are crucial for the spontaneous behavioral recovery of limb use that occurs in this model.14,44

“Wrong side” contralesional activation occurs early after TBI

We observed extensive cortical activation within the contralesional hemisphere as early as 4 days after injury that persisted, in some regions, until 30 days. Similar observations have been made in the rat after suction ablation cortical lesions,45 middle cerebral artery occlusion stroke,13 and at 2 months after CCI injury,17 as well as after clinical stroke.12,46,47 Though the mechanism for this remapping is uncertain, the short timescale precludes the idea of structural remodeling occurring to reshape the map because, unlike in stroke or lesioning studies,10,48–51 compensatory structural neuronal plasticity does not occur in the contralesional cortex after CCI injury.52 However, this does not necessarily rule out that compensatory motor learning associated with over-reliance of the unaffected limb49,53 might occur to activate contralesional circuits without any major structural remodeling. The extreme asymmetry of limb use early after brain injury44,52 and the finding that the maladaptive effects of nonparetic limb use depend upon the contralesional cortex54 would support this as a potential mechanism. It is also plausible that the mechanism of cortical plasticity is driven partly or even solely by CNS-related changes. Past studies have shown that silencing primary somatosensory cortex by cooling results in an immediate expansion of contralateral receptive fields55 and, after stroke, wrong-sided, contralesional response resulting from affected limb stimulation occurs within 30 min of infarct.38 There is now increasing evidence for the cooperative, functional interdependence of bilaterally connected cortical regions,56 so that alteration in output from one cortex significantly alters the other.57,58 Loss of anatomical connectivity after CCI injury, either by destruction of cortical gray matter or damage to underlying white matter circuitry, results in significant down-regulation of contralesional gamma-aminobutyric acid–mediated alpha-1 receptors.59 This is consistent with the idea of a loss of transhemispheric inhibition within the contralesional hemisphere from the injured side, and this may be one mechanism that underlies the contralesional activation observed, especially because the near complete normalization of receptors at 4 weeks59 coincides with the reduction in the size of the contralesional map shown in the present study.

The obvious question that arises from this contralesional activation data is, what is the relevance to outcome? At least after experimental ischemia, this is dependent on the severity or size of the infarct, because subsequent to recovery of forelimb deficits, silencing or lesioning the contralesional cortex reinstates the deficits, but only in rats with the largest strokes,60,61 indicating the functional importance of the contralesional cortex in motor recovery only in the most severe cases. Similar conclusions are arrived at after CCI injury, where involvement of the contralesional cortex in affected limb control is related to the size of the contusion40 (Harris and colleagues, submitted). Clinical stroke evidence shows that restoration of the cortical map back to newly reorganized, adjacent motor-associated regions within the ipsilesional hemisphere is required for good outcome.62–64 We observed a shift of activation back to the ipsilesional hemisphere between 7 and 30 days after trauma to perilesional sites, indicating the injury was not severe enough to prolong wrong-side activation. It remains to be determined whether wrong-side, contralesional activation influences ipsilesional plasticity acutely; whether it is beneficial or detrimental for plasticity. Given the temporal similarities between the postinjury time window in which the ipsilesional hemisphere remains permissive for plasticity,11,19 and the time when wrong-side activity occurs, further studies are warranted to investigate this.

In conclusion, we have shown that alterations in the cortical hindlimb somatosensory map size and location occur spontaneously after CCI injury. Ensuing novel regions of ipsilesional activity occur in the face of decreasing wrong-sided contralesional involvement, concordant with the known improvement in functional deficits that occur in this model.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke award (#NS055910) and the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Katz D.I. Alexander M.P. Klein R.B. Recovery of arm function in patients with paresis after traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1998;79:488–493. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gagnon I. Forget R. Sullivan S.J. Friedman D. Motor performance following a mild traumatic brain injury in children: an exploratory study. Brain Inj. 1998;12:843–853. doi: 10.1080/026990598122070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tremblay S. de Beaumont L. Lassonde M. Théoret H. Evidence for the specificity of intracortical inhibitory dysfunction in asymptomatic concussed athletes. J. Neurotrauma. 2011;28:493–502. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hillier S.L. Sharpe M.H. Metzer J. Outcomes 5 years post-traumatic brain injury (with further reference to neurophysical impairment and disability) Brain Inj. 1997;11:661–675. doi: 10.1080/026990597123214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasahara M. Menon D.K. Salmond C.H. Outtrim J.G. Taylor Tavares J.V. Carpenter T.A. Pickard J. D. Sahakian B.J. Stamatakis E.A. Altered functional connectivity in the motor network after traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 2010;75:168–176. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e7ca58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teasdale G.M. Graham D.I. Craniocerebral trauma: protection and retrieval of the neuronal population after injury. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:723–737. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199810000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroemer R.P. Kent T.A. Hulsebosch C.E. Neocortical neural sprouting, synaptogenesis, and behavioral recovery after neocortical infarction in rats. Stroke. 1995;26:2135–2144. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.11.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y.Y. Jiang N. Powers C. Chopp M. Johansson B.B. Neuronal damage and plasticity identified by microtubule-associated protein 2, growth-associated protein 43, and cyclin D1 immunoreactivity after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 1998;29:1972–1980. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.9.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmichael S.T. Archibeque I. Luke L. Nolan T. Momiy J. Li S. Growth-associated gene expression after stroke: evidence for a growth-promoting region in peri-infarct cortex. Exp. Neurol. 2005;193:291–311. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adkins D.L. Voorhies A.C. Jones T.A. Behavioral and neuroplastic effects of focal endothelin-1 induced sensorimotor cortex lesions. Neuroscience. 2004;128:473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris N.G. Mironova Y.A. Hovda D.A. Sutton R.L. Pericontusion axon sprouting is spatially and temporally consistent with a growth-permissive environment after traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010;69:139–154. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181cb5bee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer S.C. Nelles G. Benson R.R. Kaplan J.D. Parker R.A. Kwong K.K. Kennedy D.N. Finklestein S.P. Rosen B.R. A functional MRI study of subjects recovered from hemiparetic stroke. Stroke. 1997;28:2518–2527. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.12.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dijkhuizen R.M. Ren J. Mandeville J.B. Wu O. Ozdag F.M. Moskowitz M.A. Rosen B.R. Finklestein S.P. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of reorganization in rat brain after stroke. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:12766–12771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231235598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishibe M. Barbay S. Guggenmos D. Nudo R. J. Reorganization of motor cortex after controlled cortical impact in rats and implications for functional recovery. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:2221–2232. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall K.D. Lifshitz J. Diffuse traumatic brain injury initially attenuates and later expands activation of the rat somatosensory whisker circuit concomitant with neuroplastic responses. Brain Res. 2010;1323C:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passineau M.J. Zhao W. Busto R. Dietrich W.D. Alonso O. Loor J.Y. Bramlett H.M. Ginsberg M.D. Chronic metabolic sequelae of traumatic brain injury: prolonged suppression of somatosensory activation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2000;279:H924–H931. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn-Meynell A.A. Levin B.E. Lateralized effect of unilateral somatosensory cortex contusion on behavior and cortical reorganization. Brain Res. 1995;675:143–156. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00050-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emery D.L. Raghupathi R. Saatman K.E. Fischer I. Grady M.S. McIntosh T.K. Bilateral growth-related protein expression suggests a transient increase in regenerative potential following brain trauma. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;424:521–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris N.G. Carmichael S.T. Hovda D.A. Sutton R.L. Traumatic brain injury results in disparate regions of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan expression that are temporally limited. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009;87:2937–2950. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen S. Pickard J.D. Harris N.G. Time course of cellular pathology after controlled cortical impact injury. Exp. Neurol. 2003;182:87–102. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen S.F. Richards H.K. Smielewski P. Johnstrom P. Salvador R. Pickard J.D. Harris N.G. Relationship between flow-metabolism uncoupling and evolving axonal injury after experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:1025–1036. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000129415.34520.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris N.G. Mironova Y.A. Chen S.-F. Richards H.K. Pickard J.D. Preventing flow-metabolism uncoupling acutely reduces axonal injury after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1469–1482. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasband W.S. ImageJ, U.S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2008. pp. 1997–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nordin M. Fagius J. Effect of noxious stimulation on sympathetic vasoconstrictor outflow to human muscles. J. Physiol. 1995;489:885–894. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy C.S. Sherrington C.S. On the regulation of the blood-supply of the brain. J. Physiol. 1890;11:85–108. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1890.sp000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathiesen C. Caesar K. Akgören N. Lauritzen M. Modification of activity-dependent increases of cerebral blood flow by excitatory synaptic activity and spikes in rat cerebellar cortex. J. Physiol. 1998;512:555–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.555be.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngai A.C. Jolley M.A. D'Ambrosio R. Meno J.R. Winn H.R. Frequency-dependent changes in cerebral blood flow and evoked potentials during somatosensory stimulation in the rat. Brain Res. 1999;837:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw N.A. Somatosensory evoked potentials after experimental head injury in the awake rat. J. Neurol. Sci. 1986;74:257–270. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(86)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards H.K. Simac S. Piechnik S. Pickard J.D. Uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and metabolism after cerebral contusion in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:779–781. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katayama Y. Becker D.P. Tamura T. Hovda D.A. Massive increases in extracellular potassium and the indiscriminate release of glutamate following concussive brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 1990;73:889–900. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.6.0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nilsson P. Hillered L. Olsson Y. Sheardown M.J. Hansen A.J. Regional changes in interstitial K+ and Ca2+ levels following cortical compression contusion trauma in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:183–192. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moro N. Ghavim S.S. Hovda D.A. Sutton R.L. Delayed sodium pyruvate treatment improves working memory following experimental traumatic brain injury. Neurosci. Lett. 2011;491:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ip E.Y. Zanier E.R. Moore A.H. Lee S.M. Hovda D.A. Metabolic, neurochemical, and histologic responses to vibrissa motor cortex stimulation after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:900–910. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000076702.71231.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall E.D. Sullivan P.G. Gibson T.R. Pavel K.M. Thompson B.M. Scheff S.W. Spatial and temporal characteristics of neurodegeneration after controlled cortical impact in mice: more than a focal brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2005;22:252–265. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthews M.A. Carey M.E. Soblosky J.S. Davidson J.F. Tabor S.L. Focal brain injury and its effects on cerebral mantle, neurons, and fiber tracks. Brain Res. 1998;794:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris N. Hovda D. Sutton R. Acute deficits in transcallosal connectivity endure chronically after experimental brain injury in the rat: a DTI tractography study. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:A37. (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris N.G. Verley D. Hovda D.A. Sutton R.L. Cyclosporin-a reduces grey matter atrophy and stabilizes axonal integrity, but fails to reinstate brain activation after experimental traumatic brain injury. #1204 XXVth International Symposium on Cerebral Blood Flow, Metabolism, and Function; Barcelona, Spain. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohajerani M.H. Aminoltejari K. Murphy T.H. Targeted mini-strokes produce changes in interhemispheric sensory signal processing that are indicative of disinhibition within minutes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:E183–E191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101914108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs K.M. Donoghue J.P. Reshaping the cortical motor map by unmasking latent intracortical connections. Science. 1991;251:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.2000496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verley D. Hovda D.A. Sutton R.L. Harris N.G. Time-course of sensorimotor brain activation after traumatic brain injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma. 2011;28(A–81):P220. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho Y.R. Pawela C.P. Li R. Kao D. Schulte M.L. Runquist M.L. Yan J.-G. Matloub H.S. Jaradeh S.S. Hudetz A.G. Hyde J.S. Refining the sensory and motor ratunculus of the rat upper extremity using fMRI and direct nerve stimulation. Magn. Reson. Med. 2007;58:901–909. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohta M. Saeki K. Corticotrigeminal motor pathway in the rat—I. Antidromic activation. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Comp. Physiol. 1989;94:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(89)90791-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matyas F. Sreenivasan V. Marbach F. Wacongne C. Barsy B. Mateo C. Aronoff R. Petersen C. C.H. Motor control by sensory cortex. Science. 2010;330:1240–1243. doi: 10.1126/science.1195797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris N. Mironova Y.A. Hovda D. Sutton R.L. Chondroitinase ABC enhances pericontusion axonal sprouting but does not confer robust improvements in behavioral recovery. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1–12. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castro-Alamancos M.A. Borrell J. Functional recovery of forelimb response capacity after forelimb primary motor cortex damage in the rat is due to the reorganization of adjacent areas of cortex. Neuroscience. 1995;68:793–805. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00178-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chollet F. DiPiero V. Wise R.J. Brooks D.J. Dolan R.J. Frackowiak R.S. The functional anatomy of motor recovery after stroke in humans: a study with positron emission tomography. Ann. Neurol. 1991;29:63–71. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiller C. Chollet F. Friston K.J. Wise R.J. Frackowiak R.S. Functional reorganization of the brain in recovery from striatocapsular infarction in man. Ann. Neurol. 1992;31:463–472. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luke L.M. Allred R.P. Jones T.A. Unilateral ischemic sensorimotor cortical damage induces contralesional synaptogenesis and enhances skilled reaching with the ipsilateral forelimb in adult male rats. Synapse. 2004;54:187–199. doi: 10.1002/syn.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones T.A. Schallert T. Use-dependent growth of pyramidal neurons after neocortical damage. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:2140–2152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02140.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keyvani K. Schallert T. Plasticity-associated molecular and structural events in the injured brain. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2002;61:831–840. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.10.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones T.A. Schallert T. Overgrowth and pruning of dendrites in adult rats recovering from neocortical damage. Brain Res. 1992;581:156–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90356-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones T.A. Liput D.J. Maresh E.L. Donlan N. Parikh T.J. Marlowe D. Kozlowski D.A. Use-dependent dendritic regrowth is limited after unilateral controlled cortical impact to the forelimb sensorimotor cortex. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1455–1468. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kozlowski D.A. Schallert T. Relationship between dendritic pruning and behavioral recovery following sensorimotor cortex lesions. Behav. Brain Res. 1998;97:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allred R.P. Cappellini C.H. Jones T.A. The “good” limb makes the “bad” limb worse:experience-dependent interhemispheric disruption of functional outcome after cortical infarcts in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 2010;124:124–132. doi: 10.1037/a0018457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarey J.C. Tweedale R. Calford M.B. Interhemispheric modulation of somatosensory receptive fields: evidence for plasticity in primary somatosensory cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 1991;6:196–206. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shuler M.G. Krupa D.J. Nicolelis M.A. Bilateral integration of whisker information in the primary somatosensory cortex of rats. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5251–5261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05251.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rema V. Ebner F.F. Lesions of mature barrel field cortex interfere with sensory processing and plasticity in connected areas of the contralateral hemisphere. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:10378–10387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10378.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maggiolini E. Viaro R. Franchi G. Suppression of activity in the forelimb motor cortex temporarily enlarges forelimb representation in the homotopic cortex in adult rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008;27:2733–2746. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee S. Ueno M. Yamashita T. Axonal remodeling for motor recovery after traumatic brain injury requires downregulation of γ-aminobutyric acid signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e133. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Biernaskie J. Szymanska A. Windle V. Corbett D. Bi-hemispheric contribution to functional motor recovery of the affected forelimb following focal ischemic brain injury in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;21:989–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shanina E.V. Schallert T. Witte O.W. Redecker C. Behavioral recovery from unilateral photothrombotic infarcts of the forelimb sensorimotor cortex in rats: role of the contralateral cortex. Neuroscience. 2006;139:1495–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seitz R.J. Höflich P. Binkofski F. Tellmann L. Herzog H. Freund H.J. Role of the premotor cortex in recovery from middle cerebral artery infarction. Arch. Neurol. 1998;55:1081–1088. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.8.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ward N.S. Functional reorganization of the cerebral motor system after stroke. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2004;17:725–730. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200412000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marshall R.S. Perera G.M. Lazar R.M. Krakauer J.W. Constantine R.C. DeLaPaz R.L. Evolution of cortical activation during recovery from corticospinal tract infarction. Stroke. 2000;31:656–661. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]