Abstract

Patient: Female, 40

Final Diagnosis: Esophageal lipoma

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Laparoscopic enucleation

Specialty: Surgery

Objective: Rare disease

Background:

Benign tumors of the esophagus are very rare, constituting only 0.5% to 0.8% of all esophageal neoplasms. Approximately 60% of benign esophageal neoplasms are leiomyomas, 20% are cysts, 5% are polyps, and less than 1% are lipomas.

Case Report:

A 40-year-old woman was referred to our department with dysphagia that had progressively worsened during the previous 2 years. Physical examination on admission produced normal findings. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a submucosal space-occupying mass in the posterior wall of the lower esophagus, with normal mucosa. The mass was yellowish and soft. A computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a submucosal esophageal lesion in the posterior wall, with luminal narrowing of the distal esophagus. Thus, a submucosal tumor was identified in this region and esophageal submucosal lipoma was considered the most likely diagnosis. A laparoscopic operation was performed. The tumor was completely enucleated, and measured 10×7×2.5 cm. The pathology showed lipoma. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged 4 days after the operation.

Conclusions:

Benign tumors of the esophagus are very rare. Laparoscopic transhiatal enucleation of lower esophageal lipomas and other benign tumors is a safe and effective operation.

Keywords: esophageal lipoma, laparoscopic, enucleation

Background

Benign tumors of the esophagus are very rare constituting only 0.5 to 0.8% of all esophageal neoplasms. Approximately 60% of benign esophageal neoplasms are leiomyomas, 20% are cysts, 5% are polyps and less than 1% are lipomas. Indeed Mayo et al reported 4.000 clinical cases of benign neoplasms of the digestive tract. Lipomas accounted for only 4.1% of all cases, and esophageal lipomas for only 0.4% [1].

Lipomas have been found in all segments of the alimentary tract. Lesions in the colon occur most frequently, followed in decreased order, by lesions in the small intestine, stomach and esophagus [2]. Most esophageal lipomas are small, they cause no symptoms and may be found incidentally during imaging studies [3]. Rarely, lipomas become large and cause symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, and surgical excision is required. Herein we report a rare case of esophageal lipoma which was enucleated laparoscopically and we review the literature.

Case Report

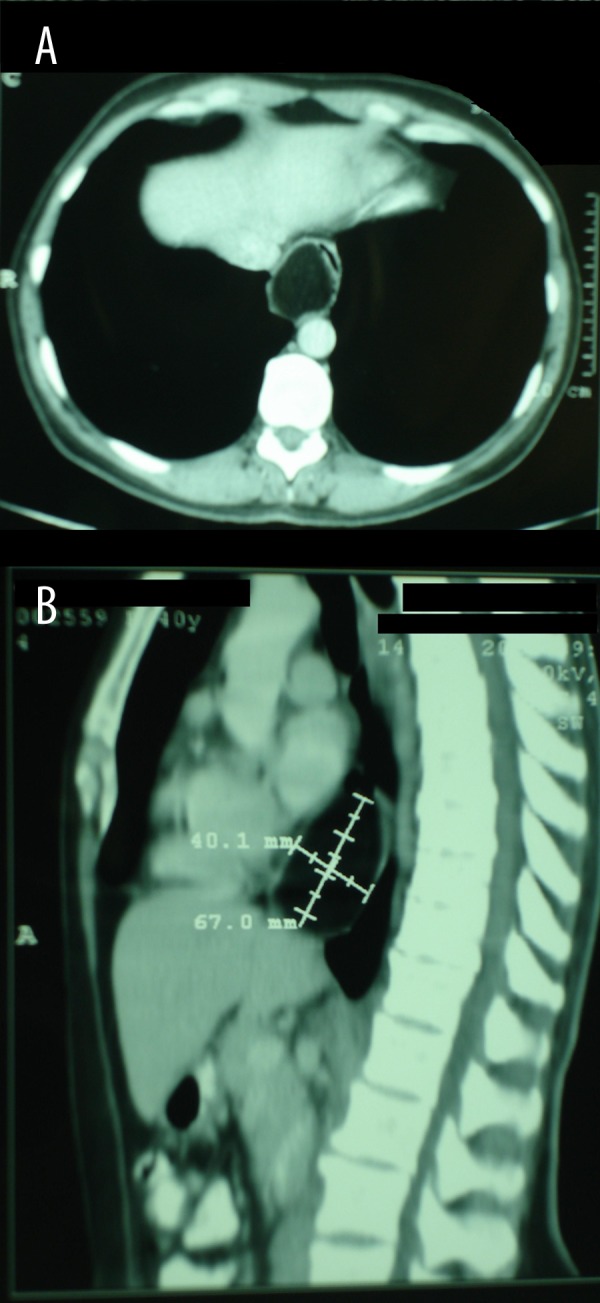

A 40-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with a progressively worsened dysphagia over the past 2 years. The clinical interview disclose nothing. Physical examination on admission revealed normal findings. The patient’s hemoglobin concentration was 12.6 g/dL white blood cell count was 5,800/mm3, and tumor markers (CEA, CA19-9) were within normal limits. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a submucosal space-occupying mass with normal mucosa, arising from the posterior wall of the lower third of the thoracic esophagus (Figure 1). The mass was yellowish in color and soft in consistency. Besides that the patient had a sliding hiatal hernia with esophagitis LA class C. Computed tomography (CT) study of the chest revealed a low-density tissue absorption submucosal lesion measured 40×67 mm and covered by normal mucosa of the lower third of the thoracic esophagus (Figure 2A, 2B). Thus, a submucosal tumor was identified in this region, and esophageal submucosal lipoma was considered the most likely diagnosis. No lymph node, lung or liver metastasis was evident.

Figure 1.

Esophagoscopy: Submucosal tumor yellowish in color with normal mucosa arising from the posterior wall of the lower third of the thoracic esophagus.

Figure 2.

CT study of the chest and uper abdomen revealed a 40×60mm submucosal lesion of the lower third of the thoracic esophagus.

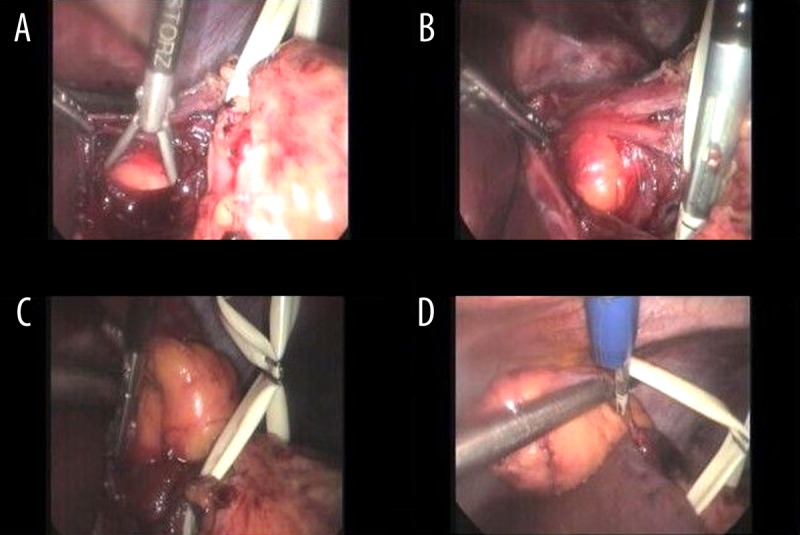

Laparoscopic enucleation of the esophageal lipoma was performed. The patient was placed in a low lithotomy position. Five 10 mm trocars were used as in Nissen fundoplication. A 30-degree telescope was used for this step of dissection. The portion of gastrohepatic omentum overlying the caudate lobe of the liver was incised using Ligasure Atlas 5 mm. The intra-abdominal esophagus was dissected circumferentially and a penrose drain was passed around the esophagus to use this as an esophageal retractor for the remainder of the procedure. After dissecting the hiatus the short gastric vessels were taken to mobilize the fundus of the stomach. Then a posterior 2 cm longitudinal esophagomyotomy of the lower esophageal wall was performed. The submucosal lipoma finally started to rise. A carerful enucleation was performed and the lipoma was placed in a specimen bug (Figure 3A–3D). The crura were reapproximated with two figure – of-eight 2/0 silk sutures. Finally a Nissen fundoplication was performed over a 60-French bugie using three 2/0 silk sutures. The giant lipoma was extracted through the videoscopy port and it measured 10×7×2.5 cm (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Enucleation of the esophageal tumor after longitudinal incision of the posterior wall of the lower esophagus.

Figure 4.

Macroscopic findings of the esophageal tumor: Yellowish in color adipose tissue-like appearance. 10×7×2.5 cm in size.

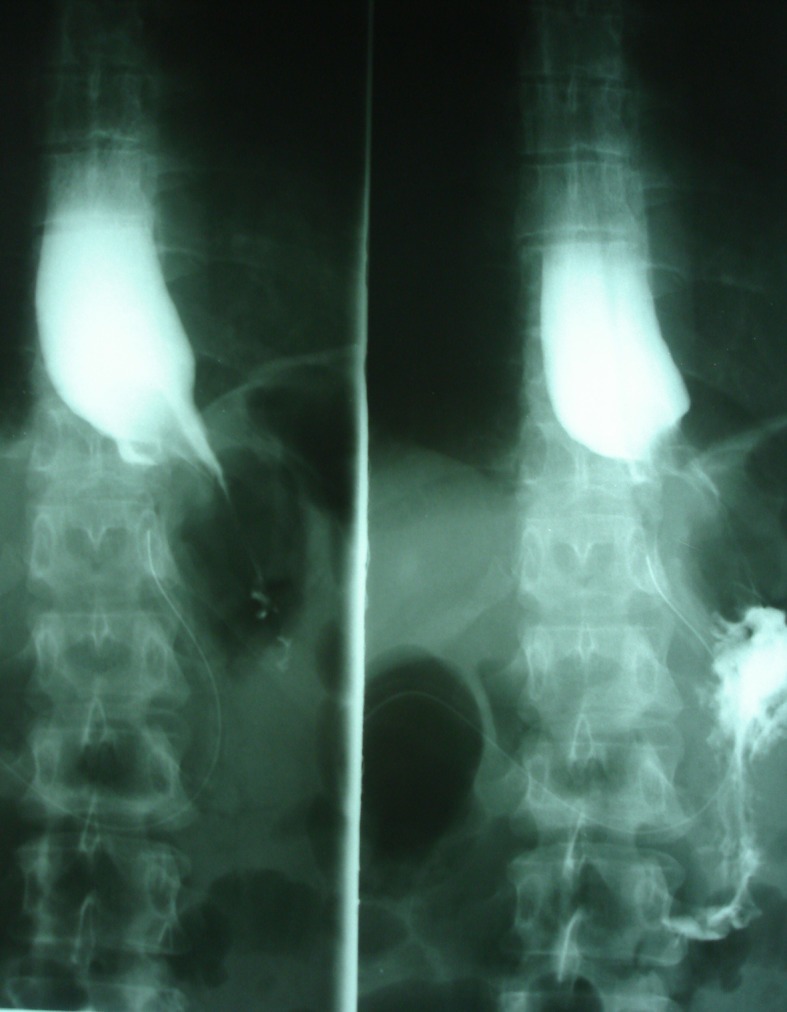

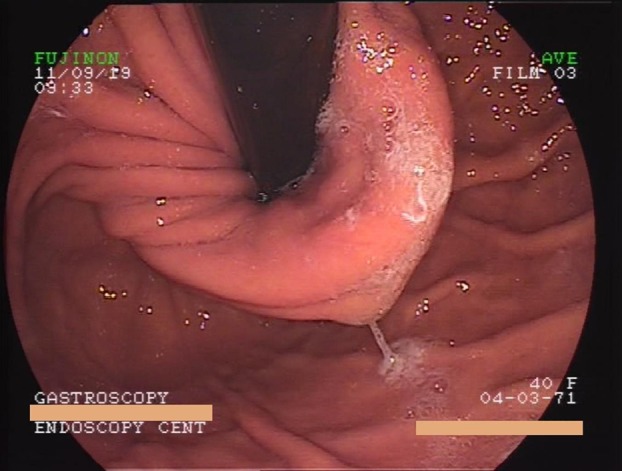

The pathology showed lipoma comprising of a collection of mature adipose tissue. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the 4th postoperative day after a gastrogafin pass to assess the integrity of the esophageal wall (Figure 5). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy three months after the operation showed a normal esophageal mucosa with good antireflux valve (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Postoperative esophageal x- ray using gastrografin swallow.

Figure 6.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy three months after the operation showed a normal esophageal mucosa with good antireflux valve.

Discussion

Benign tumors of the esophagus are very rare. Indeed, tumors including adenoma, fibroma, hemangioma, leiomyoma, rhabdomyoma, lipoma, and lymphangioma, account for less than 1% of all esophageal neoplasms. Esophageal lipomas account for only 0.4% of benign tumors of the alimentary tract and as most have been identified at autopsy, fewer than 20 surgical cases of esophageal lipoma have been reported in the literature (Table 1). The largest series reported to date is that by Akiyama et al. [4], who documented 10 esophageal lipomas (7 cervical esophagus; 3 thoracic esophagus). Most esophageal lipomas are small and occur singly; they do not cause symptoms and do not have to be removed. However, Hosokawa et al. [5] reported that a tumor may grow 2.5 times over 3.75 years, and that multiple growths may occur in the same segment or widely separated. Such multiple growths may be ovoid, round, spherical or lobulated, and gray or grayish-yellow in color. Generally, lipomas over 2cm in diameter appear capable of producing symptoms [5,6]. Various management options are available, depending on tumor size and location, and include excision by cervical esophagotomy, mini-thoracotomy, or endoscopy. Surgical excision (enucleation) is recommended for symptomatic benign tumors and those greater than 5 cm. Traditionally, tumors in the distal third of the esophagus are resected through a left thoracotomy, with all its associated morbidity. In our case the tumor was located in the posterior wall of the lower esophagus, and was removed via laparoscopic operation as described previously. Jesic et al. [7] proposed the transhiatal approach for lower esophageal tumors. The lower esophagus can easily be mobilized so that at least 5 cm of esophagus lies in the abdomen. For our case, the hiatus was widened to provide adequate access into the mediastinum. Using this method, these tumors could be quite easily removed. After removal of the tumor the diaphragmatic crura were approximated using two 2/0 silk sutures. Then a Nissen fundoplication was performed in order to reinforce the esophageal wall and to avoid GERD.

Table 1.

Esophageal lipoma case reports.

| Author | Age | Location | Symptoms | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinnear (1955) | 44 | L | Epigastric pain | Thoracotomy |

| Schmidt et al. (1961) | 47 | NA | Irritation on swallowing | Thoracotomy |

| Mayo et al. (1963) [1] | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nora (1964) [7] | 70 | L | Dysphagia | Thoraco-abdominal |

| Tolis & Shields (1967) [8] | 51 | MI | Epigastralgia | Thoracotomy |

| Sekiya & Ida [9] | 69 | C | Dysphagia | Cervical resection |

| Tasaka et al. (1982) [10] | 54 | C | Dysphagia | Cervical resection |

| Hosokawa et al. (1985) [11] | 43 | U | Dysphagia | Endoscopic resection |

| Oyamada et al. (1987) [12] | 75 | L | Dysphagia | Endoscopic resection |

| Akiyama et al. (1990) [3] | 75 | U | Dysphagia | Thoracotomy |

| Zschiedrich (1990) [13] | 64 | U | Dysphagia | Thoracotomy |

| Hasan & Mandhan (1994) [14] | 4 | C | Wheezing | Cervical resection |

| Sossai et al. (1996) [15] | 46 | L | Epigastralgia | Diathermic snare |

| Samad et al. (1999) [16] | 6 | U | Respiratory distress | Thoracotomy |

| Chien-Ying Wang et al. (2005) [17] | 71 | U | Dysphagia | Video-assisted thoracoscopic enucleation |

| C. Algin & E. Ihtiyar (2006) [18] | 55 | U | Dysphagia | Thoracotomy |

| Ryan L. Kau et al. (2011) [19] | 38 | U | Odynophagia | Laryngopharyngoscopy |

| K.Tsalis et al. (2012) | 40 | L | Dysphagia | Laparoscopic enucleation |

L – lower third; U – upper third; Mi – middle third; C – cervical esophagus; NA – not available.

Laparoscopic transhiatal enucleation of lower esophageal lipomas and other benign tumors is a safe and effective operation. When combined with intraoperative esophagoscopy, localising the tumor is easier [8]. It has the advantage of avoiding thoracotomy or laparotomy and its associated morbidity. Compared to open surgery, the minimally invasive approach reduced pulmonary complications, hospital stay, and postoperative wound related pain. The operating time was the same for both approaches

References:

- 1.Mayo CW, Pagutalunan PJG, Brown DJ. Lipoma of the alimentary tract. Surgery. 1963;53:598–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman M. An appraisal of associated conditions occurring in autopsied cases of lipoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 1961;36:413–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nora PF. Lipoma of the esophagus. Am J Surg. 1964;108:353–56. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(64)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiyama S, Kataoka M, Horisawa M, et al. Lipoma of the esophagus – report of a case and review of the literature. Jpn J Surg. 1990;20:458–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02470832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hosokawa O, Shirasaki I, Sandou N. Endoscopic removal of esophageal lipoma. Gastroenterological Endoscopy. 1985;27:738–43. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tolis GA, Shields TW. Intramural lipoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1967;3:60–62. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)66689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jesic R, Randjelovic T, Gerzic Z, et al. [Leiomyoma of the esophagus: case report] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oyamada H, Kishi T, Yoshie S, et al. A case of esophageal lipoma resected endoscopically. Shindan to Chiryo. 1987;75:2747–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinnear JS. Report of a case of intramural lipoma of the esophagus. Br J Surg. 1955;42:439–41. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004217418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt HW, Clagett OT, Harrison EG., Jr Benign tumors and cysts of the esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1961;41:717–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sekiya T, Ida M. Giant fibrolipoma of the esophagus. Jibiinkoka. 1972;44:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tasaka Y, Makimato K, Yamauchi M, Haebara H. Benign pedunculated intraluminal tumor of the esophagus. J Otolaryngol. 1982;11:111–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zschiedrich M, Neuhaus P. Pedunculated giant lipoma of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1614–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasan N, Mandhan P. Respiratory obstruction caused by lipoma of the esophagus. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1565–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sossai P, De Bernardin M, Bissoli E, Barbazza R. Lipomas of the esophagus: a new case. Digestion. 1996;57:210–12. doi: 10.1159/000201342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samad L, Ali M, Ramzi H, Akbani Y. Respiratory distress in achild caused by lipoma of the esophagus. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;34:1537–38. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C-Y, Hsu H-S, Wu Y-C, et al. Intramural lipoma of the esophagus. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005;68(5):240–43. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Algin C, Hacioğu A, Aydin T, Ihtiyar E. Esophagectomy in esophageal lipoma: report of a case. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2006;17(2):110–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kau RL, Patel AB, Hinni ML. Giant Fibrolipoma of the Esophagus. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2012;2012:406167. doi: 10.1155/2012/406167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]