Abstract

While the prevalence of smokeless tobacco (ST) is low relative to smoking, the distribution of ST use is highly skewed with consumption concentrated among certain segments of the population (rural residents, males, whites, low-educated individuals). Furthermore, there is suggestive evidence that use has trended upwards recently for groups that have traditionally been at low risk of using ST, and thus started to diffuse across demographics. This study provides the first estimates, at the national level, of the effects of magazine advertising on ST use. The focus on magazine advertising is significant given that ST manufacturers have been banned from using other conventional media since the 1986 Comprehensive ST Act and the 1998 ST Master Settlement Agreement. This study is based on the 2003–2009 waves of the National Consumer Survey (NCS), a unique data source that contains extensive information on the reading habits of individuals, matched with magazine-specific advertising information over the sample period. This allows detailed and salient measures of advertising exposure at the individual level and addresses potential bias due to endogeneity and selective targeting. We find consistent and robust evidence that exposure to ST ads in magazines raises ST use, especially among males, with an estimated elasticity of 0.06. There is suggestive evidence that both ST taxes and cigarette taxes reduce ST use, indicating contemporaneous complementarity between these tobacco products. Sub-analyses point to some differences in the advertising and tax response across segments of the population. The effects from this study inform the debate on the cost and benefits of ST use and its potential to be a tool in overall tobacco harm reduction.

I. Introduction

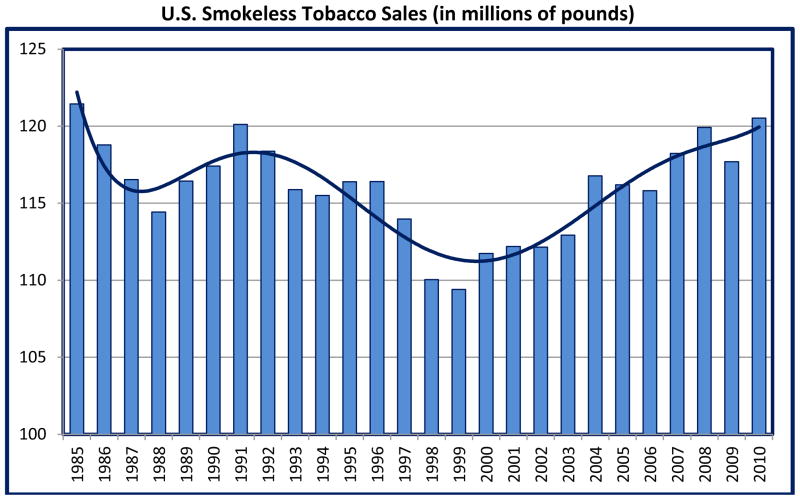

The consumption of smokeless tobacco (ST) in the U.S. underwent a resurgence in the 1970s, following increased public awareness of the hazards of cigarette smoking and consequent declines in smoking prevalence. Production of ST continued to increase through 1985 when two significant events took place (Chaloupka et al. 1997).1 The first was the release in 1986 of the Surgeon General’s report (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services - USDHHS 1986) on the adverse health consequences of using smokeless tobacco. It concluded that ST presents a significant health risk, can cause cancer and a number of non-cancerous oral conditions, can lead to nicotine addiction and dependence, can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease including heart attacks, and is therefore not a safe substitute for cigarette smoking. Also in the same year, Congress passed the Comprehensive Smokeless Tobacco Act, which banned advertising of ST products on broadcast media and required health warnings to be displayed on ST packages. These actions were followed by declining ST sales over the 1990s, though more recently sales have again trended upwards (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Sales (in millions of pounds)

Smokeless tobacco (ST) is not subject to combustion, and generally consumed orally in two forms in the U.S.: chewing tobacco, which is chewed or held in the cheek or lower lip to release flavor and nicotine, and moist snuff, which has a much finer consistency, does not require chewing or spitting, and comprises the vast majority of ST sales (87%) and ST users (79%).2 In 2010, 3.6% of adults reported current use of smokeless tobacco, and while this overall prevalence rate is low relative to cigarette smoking (24.6%), the distribution of ST use has traditionally been highly skewed with use concentrated among certain population subgroups. For instance, as shown in Table 1, in rural counties the prevalence of past-month ST use is 7.1% compared with 2.2% in large metropolitan counties. Among young adult males between the ages of 18–34, 10.4% report using ST in the past month; past year and lifetime prevalence for this group are 15.3% and 36.5% respectively. Use of ST is also significantly higher among low-educated individuals, and among residents in the Midwest and South relative to other areas of the country.3

Table 1.

Prevalence and Trends in Smokeless Tobacco Use by Selected Demographic Groups

| Prevalence of Past Month Smokeless Tobacco Use (%) Adults Ages 18 and older | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1992 | 1998 | 2006 | 2010 |

| All | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

| Male | 7.4 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Female | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Ages 18–25 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 6.4 |

| Ages 26–34 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| Ages 35 + | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.7 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 4.4 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 4.6 |

| Non-Hispanic African-American | 2.2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.4 |

| Non-Hispanic Other Race | 2.2 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.6 |

| Hispanic | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Large Metropolitan Areas | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.2 |

| Small Metropolitan Areas | 3.5 | 3.3 | 4.7 | 4.1 |

| Rural | 7.1 | 6.4 | 8.8 | 7.1 |

| Less than High School Education | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 3.6 |

| High School Graduates | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.6 |

| Some College or above | 3.1 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.0 |

| Observations (All adults) | 21,578 | 18,722 | 36,965 | 39,259 |

Notes: Weighted means are reported based on data from the National Household Surveys of Drug Abuse (NHSDA) and the National Surveys of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

Furthermore, recent waves of the National Surveys of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicate that smokeless tobacco use may be on the rise for certain demographic groups (Table 1). Past month prevalence of ST use declined among adults until the late 1990s, but since then has trended slightly upwards. Among specific sub-groups, the rise is more prominent; for instance, among non-Hispanic white males between the ages of 18 and 34, use has increased from 10.2% in 1998 to 15.7% in 2010. Use has also increased among urban residents, among Hispanics and other races (besides white and black), and among those with higher levels of educational attainment. Since these are groups which traditionally have had low prevalence rates, the recent trends suggest that ST use may be diffusing across demographic segments.

These recent trends in ST use appear even more divergent when compared with past month smoking prevalence, which decreased from 38.3% in 1978, to 28.7% in 1998, to 24.6% in 2010 (NSDUH). As smoking bans are imposed across the nation and cigarette sales continue to decline, new ST products are marketed to smokers for use in situations where they may be unable to smoke.4 Adams et al. (2012) find an increase in ST use among smokers, especially among smokers who also drink or are more likely to frequent bars, following smoking bans in bars. This suggests that some smokers may be using ST to satisfy their nicotine cravings in settings where smoking is not permitted.

While the 1986 Surgeon General’s report pointed to a significant risk of oral cancer, newer-generation ST products have lower levels of recognized carcinogens such as tobacco-specific nitrosamines and may therefore carry a lower cancer risk (Rodu and Jansson 2004). The relative risk of smoking-related cancers and mortality is also found to be significantly lower among ST users compared with both current and former smokers (Lee and Hamling 2009).5 Thus the debate has centered on weighing the costs and benefits of ST consumption, and its potential to serve as a tool that can be used towards reducing tobacco-related harm (Gartner et al. 2007a; 2007b). The evidence on this debate is somewhat mixed. Some critics contend that increased ST use could reduce smoking cessation because smokers who would otherwise quit due to the inconvenience of smoking bans may use ST products when smoking is not allowed and resort back to smoking when permitted. Indeed, some evidence seems to suggest that smokeless tobacco may be a gateway product for subsequent smoking among male youths and may have little beneficial effects on the likelihood of quitting smoking (Tauras et al. 2007; Bask and Melkersson 2003; Tomar 2003). Other studies however have suggested that use of ST products is associated with a higher probability of quitting smoking (Ramström and Foulds 2006; Ault et al. 2004), and that health-adjusted life expectancy is not very different for smokers who are fully tobacco-abstinent versus smokers who switch from cigarettes to ST (Gartner et al. 2007b).

Data from the National Consumer Surveys (described below) suggest that males who have attempted to quit smoking have a significantly higher prevalence of ST use (9.6%) relative to male smokers who have not attempted smoking cessation (4.7%). Thus, smokers may use ST as a path towards quitting. Furthermore, prevalence of ST use also appears to be significantly higher among male smokers with successful quit attempts relative to those whose quit attempts failed.6 Rodu and Phillips (2008), based on the 2000 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS), confirm that, while not as common as other methods such as the Nicotine patch or gum, male smokers do use ST as a smoking cessation aid. They also find that switching to ST had the highest success rate compared to any of the other methods. Furthermore, 54% of those who switched to ST as a smoking cessation aid did not use any tobacco product at the time of the survey, suggesting that switching to ST is not necessarily at odds with a goal of achieving total tobacco abstinence.

Given these considerations, the relevant question for public policy is whether ST, which is significantly safer than smoking though not entirely safe, should be promoted as a harm-reduction measure. The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, signed into law in June 2009, gives the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products. While it requires new and larger health warning labels for smokeless tobacco products, the FDA is also considering whether to allow tobacco companies to market some tobacco products as “modified-risk” or safer alternatives to cigarettes. The manufacturer would need to file an application with the FDA to market its product as a modified-risk tobacco product (MRTP), and in turn the FDA must issue an order for its sale based on evidence that the sale of the MRTP is consistent with promoting public health and that, compared with conventional tobacco products, it has the potential to reduce tobacco-related harms (Institute of Medicine 2011). Given the dearth of credible evidence regarding the impact of MRTPs on individual and public health, a recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report recommended that the FDA adopt a stringent evidentiary burden when evaluating applications to market MRTPs. The FDA in turn has issued a draft guidance on MRTP applications for public comment and is considering how much of an evidentiary burden to impose on manufacturers of ST and other possible MRTPs.

Given the potential for ST to aid in minimizing tobacco-related harm, advertising and marketing are likely to play an integral role in promoting these relative benefits. If safer ST products are available but the FDA adopts a high evidentiary burden and makes it difficult for manufacturers to advertise them, then consumer welfare and public health may be compromised. On the other hand, if shifts in advertising practices are expanding ST use to new population groups that have been at low-risk of using tobacco, then this may counteract some of the relative health benefits associated with smokers switching from cigarettes to ST. Thus, in order to evaluate the full costs and benefits of setting stricter versus more relaxed evidentiary standards on ST manufacturers, it is integral to know how ST advertising affects consumption decisions. This study provides some of the first evidence on this issue.

Specifically, we examine the determinants of smokeless tobacco use, with a particular focus on estimating the impact of magazine advertising. The focus on magazine ads is especially salient given that ST manufacturers are banned from advertising in most other media. Magazines currently comprise the primary form of conventional media advertising for ST products, and their share in total promotion (which includes both media ads and point-of-sale promotion) increased from 19% in 1986 to over 50% in 2004 (Federal Trade Commission - FTC 2012).

Identifying the causal effects of advertising remains a challenge in the literature due to potential bias from simultaneity and the selective targeting of potential users. In addressing these concerns, we adopt the same dataset and the novel identification strategy as set forth by Avery et al. (2007) in their study of the link between smoking cessation product ads and smoking cessation. The empirical analyses are based on the 2003–2009 waves of the National Consumer Survey (NCS), a unique data source that contains extensive information on the reading habits of individuals, allowing detailed and salient measures of magazine advertising exposure at the individual level.7 Models exploit this variation in individual-specific advertising exposure to identify plausibly causal effects on ST use within a fully-specified demand model that also considers the role of ST taxes and cigarette taxes. For instance, two persons reading the same types of magazines (for instance, automobile magazines) may be exposed to different levels of ST ads because one reads Car & Driver and one reads Popular Mechanics. Even readers of the same magazine may be exposed to different levels of ST ads due to variation in their reading frequency and the staggering of ad spending across different months and issues.

These measures of advertising exposure, which vary at the individual level, significantly improve upon much of the tobacco advertising literature that has relied on aggregate measures (Dave and Kelly 2012). The bulk of this literature is confined to cigarettes, and our study provides the first estimates of the effects of ST advertising using national data. Given recent strategic shifts in ST marketing and the suggestive rise in ST use among certain demographic groups, this study also assesses differential responses to advertising and tobacco taxes across various segments of the population, providing the most comprehensive picture of the determinants of ST demand to date.

Owing to the external and internal costs of tobacco use8, the key debate on advertising has understandably centered on whether, and the extent to which, tobacco advertising and promotion impacts primary (market) demand versus selective (brand-specific) demand. The industry maintains the latter viewpoint in contending that their advertising practices are intended only to affect brand-specific sales and market share, whereas the concern for public health centers on the potential for advertising to raise total consumption and expand the size of the overall market. With respect to ST, effects on primary demand are a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for reducing tobacco-related harm. That is, promotion of ST would need to induce current (or future) smokers to consider using ST as a cessation aid or as a substitute for smoking in order to potentially reduce tobacco-related harm, and this would reflect an expansion in overall ST demand. As no prior study has provided evidence on whether ST advertising affects total ST demand, estimates from this study are relevant in informing the debate with respect to the role of ST use in tobacco harm reduction as well as the broader debate with respect to whether advertising for tobacco products is effective in expanding primary demand.

II. Background

Advertising

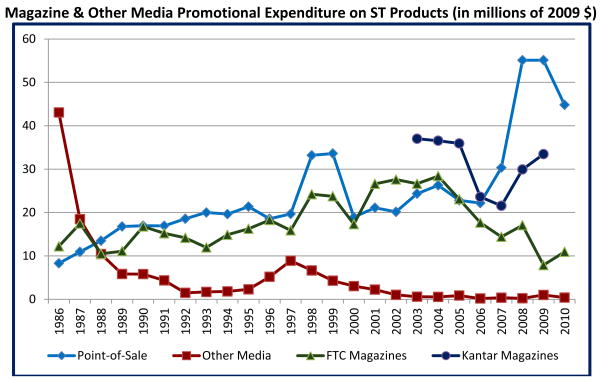

In 2008, total advertising and promotion comprised almost 20% of ST sales, compared to an all-industry average of about 4–5% (Dave and Kelly 2012). Figure 2 shows trends in magazine and other media advertising. Advertising of ST products in the broadcast media has been banned since 1986 by the Comprehensive Smokeless Tobacco Act. Despite this broadcast media ban, there was not a significant decline in total promotional spending due to a shift in marketing towards magazines, outdoors, point-of-sale, public entertainment venues and especially price-based promotion through coupons and direct discounts to retailers for product placement.9 In November of 1998, the Smokeless Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement (STMSA) further eliminated tobacco advertisements on billboards, in arenas, stadiums, shopping malls, video arcades and on private or public transit vehicles or waiting areas. This led to further shifts in promotion towards magazines and point-of-sale displays. In real terms, magazine advertising expenditures increased by 177% over 1988–2004, raising their share of total media spending from 30% to 51% over this period. An absolute and relative decline in magazine ads ensued over the next few years. 10 Part of this trend followed a general decline in print tobacco advertising, as price-based promotion and point-of-sale promotion at the retail locations became more dominant (Institute of Medicine 2007). The amount of tobacco advertising in magazines with a high youth audience has also declined since tobacco companies agreed to avoid targeting youth as a condition of the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (Alpert et al. 2008).11 More recent years indicate resurgence in media ads, however; there was a 60% increase in ST magazine ad spending between 2007 and 2009 (based on the analyses data).

Figure 2.

Magazine & Other Media Promotional Expenditure on ST Products (in millions of 2009 $)

Subsequent to the STMSA, magazines have become the only conventional form of media advertising for ST manufacturers, which underscores the importance of studying the impact of this form of advertising. Since many magazines generally have very specific readership demographics, they can be ideal for targeting advertising messages to various adult groups. A descriptive content analysis by Curry et al. (2011) finds significant differences in magazine ads between 1998–1999 and 2005–2006. Most of the ads (86%) in their sample of 17 national magazines covered the full page, and while the majority of ads appeared in men’s interest magazines (defined as having ≥65% male readership), there was also a shift towards general adult magazines in the latter period. Recent ads, and particularly ads in general adult magazines, were also more likely to emphasize flavored products, “alternative to cigarette” messages, and indoor settings. The authors conclude that, in addition to appealing to traditional user segments, the industry is attempting to expand its audience including the targeting of smokers.12

Table 2 documents trends in exposure to ST advertising in magazines across various population segments over 2003–2009 based on the analyses data. Column 1 shows the percent of adults who have read a magazine issue that carried any ST ad over the past month (see Data section for further details). In 2003, 15.9% of the adult population was potentially exposed to some magazine ST advertising; this proportion decreased to 9.8% in 2007 and then subsequently increased to 13.6% in 2009. This exposure measure roughly tracks the recent trend in magazine advertising expenditure.13 Inflation-adjusted magazine advertising spending (reported by Kantar Media and described in the Data section) decreased from $37 million in 2003 to $21.5 million in 2007 and then increased to $33.5 million. The upward trend over the latter period is partly driven by ad placements in general adult magazines (such as People, Entertainment Weekly, and Rolling Stone), which are more widely read and may also carry higher ad prices. In order to confirm that these trends in ad exposure are not driven by general trends in magazine readership, the next column presents ST ad exposure among adults who read any magazine, showing a virtually similar trend.14

Table 2.

Potential Exposure to ST Advertising in Magazines

| Percent of Sample Exposed to Any Magazine Advertising in Past Month (Read a magazine issue with positive ST advertising expenditures) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | All Adults | Adults who have read any magazine | Males | Females | White | Non-White | Hispanic |

| 2003 | 0.159 | 0.182 | 0.241 | 0.083 | 0.166 | 0.134 | 0.111 |

| 2004 | 0.107 | 0.120 | 0.180 | 0.039 | 0.109 | 0.099 | 0.086 |

| 2005 | 0.099 | 0.113 | 0.133 | 0.066 | 0.105 | 0.074 | 0.056 |

| 2006 | 0.120 | 0.139 | 0.206 | 0.040 | 0.125 | 0.103 | 0.089 |

| 2007 | 0.098 | 0.112 | 0.176 | 0.025 | 0.100 | 0.091 | 0.070 |

| 2008 | 0.107 | 0.123 | 0.184 | 0.035 | 0.113 | 0.087 | 0.081 |

| 2009 | 0.136 | 0.164 | 0.181 | 0.093 | 0.141 | 0.118 | 0.114 |

| Total Observations | 173,029 | 142,605 | 76,616 | 96,413 | 137,267 | 35,762 | 54,328 |

| Sample | Ages 18–34 | Ages 25–44 | Ages 45–64 | Less than High School | High School Graduate | MSA Resident | Non-MSA Resident |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 0.219 | 0.139 | 0.159 | 0.106 | 0.168 | 0.167 | 0.153 |

| 2004 | 0.162 | 0.118 | 0.089 | 0.101 | 0.108 | 0.103 | 0.109 |

| 2005 | 0.107 | 0.091 | 0.102 | 0.060 | 0.105 | 0.111 | 0.090 |

| 2006 | 0.158 | 0.123 | 0.121 | 0.078 | 0.127 | 0.111 | 0.127 |

| 2007 | 0.107 | 0.112 | 0.098 | 0.091 | 0.099 | 0.087 | 0.106 |

| 2008 | 0.156 | 0.113 | 0.100 | 0.094 | 0.109 | 0.103 | 0.110 |

| 2009 | 0.148 | 0.151 | 0.129 | 0.079 | 0.145 | 0.140 | 0.133 |

| Total Observations | 41,232 | 57,605 | 65,141 | 30,335 | 142,694 | 111,097 | 61,932 |

Notes: Calculations based on 2003–2009 NCS data matched with ST advertising expenditures from Kantar Media Intelligence (see text). Weighted means are reported. For “Adults who have read any magazine”, the denominator (percent of adults who have read any magazine) for 2005 (0.871) was interpolated as the magazine reading prevalence between 2004 (0.888) and 2006 (0.853) due to missing values for non-ST ad magazines in 2005.

The remaining columns present ad exposure among various demographic groups, which informs the potential targeting of ST ads. In general, males are more likely to be exposed to ST ads than females, suggestive of male-biased targeting through men’s interest magazines. In 2009, for instance, 18.1% of males were potentially exposed to advertising compared with 9.3% of females. There is also some evidence that ST ads are targeted towards magazines whose audience is relatively more white, educated (more than a high-school education), and younger. Since the focus of this study is on adults ages 18 and older, the analyses data do not permit an examination of magazine advertising exposure among minors. However, the data do indicate that at least in the early part of the sample period, young adults ages 18–24 had a greater exposure to magazine ST ads (21.9% in 2003). The proportion of exposed young adults declined to 10.7% in 2007, but since then has increased to 14.8% in 2009. This is similar to exposure (15.1%) among adults ages 25–44, and higher than exposure among older adults ages 45–64.

While smokeless tobacco advertising continues to be targeted towards conventional user segments, demographic groups that were traditionally at low-risk of using ST products also appear to be increasingly targeted in recent years. For instance, the percent of females who are potentially exposed to ST ads increased from 4% in 2006 to 9.3% in 2009, partly driven by ST ads beginning to appear in women’s interest magazines such as Glamour, Marie Claire, and Vogue and popular magazines such as People. Similarly, exposure among Hispanics and older adults also increased over this period, again driven by increased ad spending in more general interest magazines as well as in more targeted magazines such as Latina, Popular Mechanics, Popular Science, and golf-interest magazines. There is also some suggestive evidence of increased targeting of MSA residents in recent years, as the portion of exposed adults residing in an MSA county increased from 8.7% (2007) to 14% (2009). These trends in exposure are suggestive of a possible shift in the demographic targeting of ST advertising in an effort to expand ST use into new populations.

Related Literature

Studies have consistently found that higher ST taxes reduce ST use, with elasticity estimates ranging from −0.06 to −0.10 (see for instance, Tauras et al. 2007; Ohsfeldt, Boyle, and Capilouto 1997; 1998; and Chaloupka, Tauras, and Grossman 1997). These studies, however, rely on cross-state variation to identify the tax response and do not control for state fixed effects; hence the tax elasticity estimates may be confounded by unobserved cross-state heterogeneity.

Evidence bearing upon the effects of ST advertising, on the other hand, is highly limited. Specifically no prior study has estimated the effects of ST advertising on demand based on national data from the U.S. Choi et al. (1995), for instance, study ST use among adolescent boys sampled in three waves of the California Tobacco Surveys (1990, 1992, and 1993). Using logistic regression models, they find that ST advertisements are positively associated with ST use. Cigarette smokers were also at higher risk of using ST (consistent with a complementary relation between the two tobacco products). The advertising effects, however, are based on recalled exposure to ST ads and thus subject to endogeneity bias; users or potential users are more likely to recall ST ads. Tomar (2007) reviews the literature on ST use relative to smoking in Sweden and Norway, and concludes that increased promotion of ST has contributed to increased sales primarily among adolescents and young adult males.

In contrast to the very sparse literature on ST advertising, there have been many studies that have examined the effects of cigarette advertising. Dave and Kelly (2012) provide a review of this literature. While the evidence on whether cigarette ads expand primary demand is also generally mixed and needs to be interpreted with caution due to endogeneity concerns and lack of statistical variation in the advertising measures, some of the more sophisticated analyses that have addressed these challenges tend to find that advertising in the cigarette market does raise the size of the overall market (see, for instance, Saffer and Chaloupka 2000; Tye, Warner, and Glantz 1987).

We adopt the same identification strategy as Avery et al. (2007), who examine the effects of smoking cessation advertisements. Specifically, they match information on individual magazine-reading habits from the 1995–1999 Simmons National Consumer Survey (NCS) with all print advertisements for smoking cessation products, tobacco products, and smoking-related public service announcements that appeared between January 1985 and May 2002 in 26 consumer magazines. This strategy exploits person-specific variation in ad exposure due to differences in magazine reading habits to bypass endogeneity concerns. They find that smokers who are exposed to more magazine ads are more likely to attempt to quit and are more likely to have successfully quit. They also find that, while some of this effect expectedly operates through the purchase of cessation products, ads can also increase the likelihood of quitting without the use of any cessation product.

Summary and Contributions

A limited set of studies have found consistent evidence that higher ST taxes can reduce participation and consumption, while the evidence on the cross-effects of cigarette taxes and/or prices is quite mixed (Tauras et al. 2007; Bask and Melkersson 2003; Ohsfeldt, Boyle, and Capilouto 1997; 1998). They general rely on aggregate time-series variation or cross-state variation for identification, which may have biased the own- and cross-effects. With the exception of Tauras et al. (2007) (which is based on high school students), all of these studies also utilize pre-STMSA data. Given the recent rising trends in ST use, diffusion of use across demographics, and a shifting tobacco market landscape with respect to advertising and promotion, the results from the reviewed studies may not be reflective of current conditions. Magazine advertising has become a key mode for marketing ST given the bans on other media instituted by the 1986 Comprehensive Smokeless Tobacco Act and 1998 STMSA. However, no prior study has estimated whether, and the extent to which, such advertising impacts the demand for ST in the U.S.

This study addresses these gaps, provides the first national estimates of the effects of magazine advertising on ST use, and updates the estimated elasticities with respect to tobacco taxes based on more credible within-state variation. The analyses follow Avery et al. (2007) and exploit unique individual-level data from the 2003–2009 waves of the NCS to address endogeneity bias and identify plausibly causal effects of advertising, a key challenge that has plagued virtually all non-experimental studies of advertising in cigarette and other markets (Dave and Kelly 2012; Chaloupka and Saffer 2000). Most of the above noted results for ST are based on teens and adolescents, with few studies conducted among young adults and adults – another gap which is addressed by the utilization of the NCS data. Given the rise in ST use among certain demographic groups, suggestive shifts in advertising targeting, and prior evidence of heterogeneous effects in the alcohol and cigarette markets (see Chaloupka and Warner 2000 and Saffer and Dave 2006, for instance), this study also examines differential advertising and tax responses across segments of the population.

III. Analytical Framework

One of the key questions with respect to advertising by firms in the tobacco market is whether advertising raises “selective” or brand-specific demand versus “primary” or industry-wide demand.15 Due to the externalities and internalities associated with tobacco use, the answer to this question has normative implications and relevance for public health. Under the persuasive view, advertising can alter consumers’ tastes and preferences, help firms to differentiate their products, generate an outward shift in firm-level demand, and make demand relatively less elastic. The informative view points to the transfer of information to consumers as to why they may respond to advertising. In markets characterized by imperfect information, advertising can effectively reduce search costs by conveying direct or indirect information to consumers regarding the existence, quality, price and other product attributes.

Nelson (1970) distinguishes between search goods, wherein the consumer can determine quality prior to purchase though perhaps after incurring some search costs, and experience goods, wherein the consumer can assess quality or attributes only after consumption. Advertising addresses an informational imbalance for experience goods by providing indirect information content regarding quality, and advertising intensity is thus predicted to be higher for experience goods. Especially for smokers and new ST users, ST products may have experience attributes, consistent with the high advertising-to-sales ratio for the industry.

A third view of advertising provides a framework under which advertising is complementary to the advertised product, and also bridges back to the informative view. 16 That is, advertising does not need to exert any direct influence on consumer preferences, and it may or may not possess information content. If advertising enables consumers to produce information at lower cost, then consumers can more efficiently convert market goods into valued final commodities (Stigler and Becker 1977). And, even if advertising in uninformative, consumers may value it directly, as assumed in Becker and Murphy (1993).

The upshot of this discussion is that there are elements of each view of advertising that apply to ST products. Recently, tobacco manufacturers have launched a new generation of ST products, adding new brands with different attributes such as flavoring, packaging and nicotine delivery systems to existing brand families, which are designed to appeal to new consumers. New or potential users, including smokers who may be attempting to quit, have limited information about the actual costs and benefits of ST. Advertising, along with other marketing techniques and observations of social norms, provide potential users with information about these costs and benefits. For instance, ST ads often “inform” consumers that ST products can be used as an alternative nicotine delivery system in situations where smoking is not permitted or that one of the benefits of using ST is that it does not produce primary and secondhand smoke (Timberlake et al. 2011). Consistent with the Becker and Murphy (1993) framework, ST advertising is also designed to create positive imagery related to consumption, which can result in more positive expectancies about ST and alter actual or intended consumption behavior. Since ST advertising can therefore affect both selective (brand-centric) as well as primary (market) demand under these views, the question cannot be resolved based on theory alone and empirical evidence needs to bear upon how ST advertising affects consumption decisions.

Methodology

Drawing from the above framework, the following demand function relates ST use to advertising and taxes.

| (1) |

Equation (1) denotes that the use of smokeless tobacco (ST) by the ith individual, residing in state c and interviewed in month m of year t, is a function of the person’s exposure to magazine ST advertising (ADEXP), tax rate for ST products (STTAX), excise tax for cigarettes (CIGTAX), a vector of individual-specific (X) factors such as socio-economic characteristics, and a vector of time-varying state-specific (Z) factors. The parameter μ represents an individual error term.

As a proxy for the cost of ST products and cigarettes, tax rates are utilized for several reasons. First, focusing on the state tax bypasses simultaneity between price and demand. Changes in the state-level tax rate are plausibly exogenous to the individual’s ST use, often changing in response to the state’s budgetary needs. Studies have also confirmed that changes in tobacco taxes are strongly correlated with changes in price. For instance, for the average consumer, cigarette taxes are fully passed on one-to-one with respect to retail prices (DeCicca, Kenkel, and Liu 2010). Second, the focus on taxes provides direct estimates of the effect of an important public policy tool. There remains substantial variation in tobacco taxes across states, leaving considerable room for policy manipulation. Furthermore, the own-price and cross-price elasticity of ST use can be recovered from the estimated tax elasticity based on the percent of the tax represented in the price and the tax pass-through rate.

Given that the outcome variable is a dichotomous measure of current ST use, probit models are estimated in all cases.17 Average marginal effects are reported.18 All models include indicators for month of interview (MONTH), to capture seasonal variation in tobacco use, and year indicators (YEAR), to capture unobserved national trends including variation in other forms of marketing and promotional activities related to ST.

Models specifically address the potential endogeneity of advertising by including indicators for detailed magazine groups and controlling for magazine reading intensity (total number of different magazines read and number of issues read). These specifications exploit variation in ad exposure that occurs due to individual differences in the magazines read within the same magazine group. For instance, two males who decide to read sporting magazines and who have the same overall magazine reading habits (read the same number of different magazines and read the same number of total issues over all magazines) may be exposed to different levels of ST ads because one male reads more Sports Illustrated while another reads more Sporting News.

We extend the baseline model specified in Equation (1) in a number of ways to address specific issues. First, we estimate specifications that include a full vector of magazine fixed effects. This addresses the concern that even within magazine groupings, individuals may differ, based on which magazines they read, in ways that are correlated with their ST use.

Second, we control for an expanded set of individual factors, including attempted smoking cessation, children in the household, and past and present participation in the armed forces, to address residual unobserved person-specific heterogeneity. It is notable that the NCS database is also used by major advertisers, allowing us to observe the same consumer demographic and media usage information, and thus reduces the potential for systematic targeting on further unobservables (Avery et al. 2007; Cawley et al. 2011).19

Third, we estimate models that control for state fixed effects and measures of state-level tobacco control spending to account for unobserved area-specific factors that may be driving targeting decisions and ST use. For instance, as noted earlier, ST use has been traditionally high among males in the Midwest and South, and advertisers also tend to target ads to rural residents. Thus, these area-specific measures capture these systematic differences in the use of ST products and advertising exposure due to the targeting of ads based on geographic residence. Fourth, we assess differential responses to magazine advertising and tobacco taxes through sub-analyses based on gender, age, race, educational attainment, and MSA residence.

Fifth, we assess robustness of the findings to alternative specifications and measures of advertising exposure. According to prior studies in the advertising literature, the impact of advertising may linger beyond the time of its presentation. Thus, alternative models utilize a measure of the advertising exposure stock, constructed to include the current’s month’s exposure and a decay-weighted sum of past advertising, to capture any durable effects of the ads. We also utilize alternate constructs of advertising exposure (defined in the next section) to gauge the consistency of the advertising elasticity estimates under alternative assumptions. Finally, we implement a placebo test to confirm that the results are not driven by residual unobserved heterogeneity.

IV. Data

National Consumer Study

The empirical analyses are based on individual records from the 2003–2009 Simmons National Consumer Survey (NCS). The NCS is nationally-representative of the non-institutional civilian adult population (ages 18+) in the 48 contiguous states plus D.C., and includes about 25,000 adults in each wave.

A dichotomous indicator is defined for whether the respondent currently uses any smokeless tobacco product, including moist snuff, chewing tobacco, or other types of ST. The NCS does not contain information on frequency of ST use. However, this is less of a limitation than it may appear for two reasons. First, the majority of adult ST users are daily or almost-daily users. Data from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) indicate that over 50% of adult males (ages 18 and older) who used ST in the past month did so daily, and almost two-thirds of users consumed ST on at least 20 days in the past month. Second, prior studies have shown that the bulk of the demand response to taxes, for both cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, occurs at the extensive margin (the decision to use) rather than at the intensive margin (intensity of consumption among users) (Colman and Remler 2008; Tauras et al. 2007; Chaloupka and Warner 2000; Chaloupka, Tauras and Grossman 1997). Thus, given that most ST users are high-frequency users and much of the response to policy occurs at the user vs. non-user margin, the focus on participation in ST use is warranted.

The average prevalence of ST use over 2003–2009 in the NCS sample is 2.5%. This figure masks significant gender differences. Prevalence among males is 4.7% compared to only 0.4% among females.20 The main analyses are therefore restricted to males given that very few adult women consume ST products; we estimate and report models for the full sample in the Appendix. The NCS also contains an extensive set of socio-demographic individual characteristics related to age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment, income, smoking behaviors, veteran status, children, and geographic residence, which are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Simmons National Consumer Survey (NCS) 2003–2009 Weighted Means

| Variable | All | Males |

|---|---|---|

| Current Smokeless Tobacco Use | 0.0246 | 0.0470 |

| Current Ad Exposure, adjusted for circulation | 0.0135 | 0.0223 |

| Ad Exposure Stock, adjusted for circulation | 0.0462 | 0.0782 |

| Current Ad Exposure | 28484 | 43938 |

| Ad Exposure Stock | 95159 | 151244 |

| Read any magazines | 0.8013 | 0.7717 |

| Snuff Tax (% of wholesale price) | 0.2974 | 0.2977 |

| Cigarette Tax (in dollars) | 1.4099 | 1.4100 |

| Male | 0.4821 | - |

| Age | 46.2 | 45.6 |

| Age-squared (divided by 1000) | 2.41 | 2.35 |

| White | 0.7835 | 0.7911 |

| Black | 0.1100 | 0.0989 |

| Other Race | 0.1065 | 0.1100 |

| Hispanic | 0.1296 | 0.1364 |

| Less than High School Graduate | 0.1421 | 0.1498 |

| High School Graduate | 0.3307 | 0.3286 |

| Some college | 0.2717 | 0.2584 |

| College Graduate | 0.2555 | 0.2632 |

| Income (in 10,000 $) | 2.69 | 3.49 |

| Employed | 0.6325 | 0.6981 |

| Unemployed | 0.0514 | 0.0576 |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) Resident | 0.4112 | 0.4106 |

| State Tobacco Control Spending (millions $) | 24.8 | 25.0 |

| State Tobacco Control Spending (% of CDC Recommendation) | 0.3474 | 0.3472 |

| State population (millions) | 13.1 | 13.2 |

| Total Magazines Read | 8.1 | 7.0 |

| Frequency of Reading (Total number of issues) | 14.1 | 12.1 |

| Attempt Smoking Cessation (Past Year) | 0.0907 | 0.0879 |

| Armed Forces – Current | 0.0058 | 0.0093 |

| Armed Forces – Past | 0.1371 | 0.2601 |

| Any Children under Age 12 in Household | 0.3264 | 0.3077 |

| Observations | 173,029 | 69,592 |

Notes: Weighted means are presented. Observations represent the maximum sample size; for some variables, the sample size is lower due to missing information.

Magazine Advertising

The NCS data are particularly well-suited to the study of advertising since they measure in-depth media use for each respondent. Specifically relevant for this study, the NCS includes information on the reading habits of each respondent with respect to 198 major magazines that account for virtually all U.S. magazine circulation. For each magazine, the individual reports whether they read or looked into it in the past six months. Respondents further report on the number of issues that they read out of every four issues, on average. This information can be used to construct an individual-specific probability of reading an issue of each of the 198 magazines, ranging from 0 for those who did not read the magazine at all to 1 for those who read all issues of the magazine.21

Information on the advertising of ST products in each magazine is obtained from Kantar Media for the years 2003–2009. Specifically, national advertising expenditures for all ST products are appended to each individual respondent based on the magazines read by the respondent and by month and year of interview.22 As shown in Equation (2) below, total exposure to ST magazine ads (AdExp), for a given respondent iin month m and year t, can be defined as the product of the respondent’s probability of reading an issue of each magazine multiplied by the amount of advertising that took place in that magazine in the given month and year, summed over all 198 magazines (denoted by the subscript j).23

| (2) |

Ideally, we want to capture some measure of the quantity of ads that appear in each magazine, which can be derived by deflating advertising expenditures in each magazine by the magazine-specific unit cost of advertising. While information on magazine-specific ad costs is not available, the single most significant predictor of these advertising rates is the magazine’s audience size or total circulation (Koschat and Putsis Jr. 2002).24 We thus proxy the total number of ST ads in each magazine by dividing the advertising expenditures (Advertising) measured in dollars with the magazine’s annual circulation (Circulation).25 This scales the magazine advertising spending to the dollars-per-issue level and also deflates expenditures with a proxy for the advertising cost.

We note that the advertising exposure measure is probabilistic in nature and represents potential exposure as it is not known whether the individual actually saw the ads. In order to reduce measurement error and improve the measured likelihood of ad exposure, we omit persons who reported that they only read 1 or 2 issues out of the past 4 issues of magazines that carry ST ads. For these individuals, the probability of reading an issue would be 0.25 and 0.5 respectively. Thus, it is unclear whether they have actually read the issue, and exposure for them is likely measured with greater uncertainty. For the remaining individuals (those who read most or all issues of the magazine and those who do not read the magazine at all or read less than a full issue out of the past 4 issues), there is far less uncertainty with respect to readership.26 That the individual’s frequency of reading each magazine is directly observed constitutes a major advantage of the NCS. Most prior studies in the tobacco literature do not observe this person-specific exposure and have instead relied on aggregate national ad expenditures (which potentially confound other national trends) or aggregate local ad expenditures (which potentially confound area differences and capture only a very small portion of total advertising).

The measure defined in Equation (2) represents current ad exposure. An alternative measure of the stock of ad exposure is also constructed in order to assess durable effects of advertising. Empirical studies of consumer goods find that most of the effects of advertising are short-lived and tend to fully depreciate within a few months (Bagwell 2007). Thus, the advertising stock is constructed to include the current month’s advertising and a decay-weighted sum of advertising over the past six months. Specifically, a decay rate (d) of 0.2 was used to construct the advertising stock for each magazine, for month t, defined as: 27

| (3) |

This advertising stock (AdStock) is then used in lieu of the current month’s advertising in Equation (2) multiplied by the probability of reading each magazine, and summed over all 198 magazines to construct the individual-specific stock of ad exposure (below).

| (4) |

The baseline specifications control for detailed indicators for 27 magazine groups and the intensity of the individual’s magazine reading habits, captured by the total number of different magazines read and by the total number of magazine issues read across all magazines. The controls for magazine groups (which are defined by the NCS and observed by the advertisers) accounts for unobserved heterogeneity across individuals based on their reading habits. The controls for reading intensity account for the fact that some individuals may be exposed to more ST ads simply because they read many different magazines or because they read these magazines more intensely. Since this source of variation in ad exposure may be correlated with other person-specific heterogeneity (for instance, related to education or socioeconomic status, opportunity cost of time, other material resources), it is not used for identification.

In these models, there are three sources of variation in person-specific ad exposure. First, within a magazine category, differences in exposure may result from reading different magazines. Two males, for instance, who both choose to read a given type of magazines (for instance, news weeklies), who read the same number of magazines, and who read the same number of issues across all magazines, would be exposed to different levels of ST ads because one person reads (more) Time and the other person reads (more) Newsweek. Second, there is variation in exposure due to differential changes in the placement of ads over time in each magazine. That is, a person reading Time may be exposed to more or less ads due to changes in ad content over time. Finally, individuals differ in their frequency of reading specific magazines. When we include magazine fixed effects in supplementary models, only the last two sources of variation are used for identification. These models focus on differences in ST use among individuals who read the same exact magazines but are exposed to different amounts of advertising based on which month they read the magazine and when the ads appears in that magazine. Conditional on all observed demographics and other factors from the NCS, this variation in advertising exposure is plausibly exogenous across individuals and bypasses bias due to potential simultaneity between advertising and demand.

Other Appended Variables

Based on each respondent’s state of residence and time of interview (month and year for taxes; and year for other measures), tobacco tax and tobacco control policy data were matched to the individual records. Measures of state-level taxes for cigarettes and ST products are obtained from The Tax Burden on Tobacco: Historical Compilation (Orzechowski and Walker 2010). While all states impose excise taxes on cigarettes, very few states impose excise taxes on ST products; instead, ST taxes in virtually all states and periods are expressed as a percentage of the wholesale price. Due to lack of consistent information on wholesale or retail smokeless tobacco prices (at the state-year level), an estimate of the snuff excise tax as a percentage of price could not be constructed for those states that do impose an excise tax. We therefore follow prior studies (for instance, Tauras et al. 2007; Chaloupka, Tauras, and Grossman 1997) and incorporate only the information on the snuff tax rate, and include an indicator for those states and periods that had an excise tax.

States impose separate taxes on snuff and chewing tobacco, both of which are highly collinear across states and over time (correlation of 0.99). In order to bypass this collinearity, all models control for the state tax rate on snuff since the vast majority of males who consume ST in the U.S. use snuff (85% in the NCS and 88% in the NSDUH). The average tax rate on snuff over the sample period is 29.7% of the wholesale price (Table 3). 28

Specifications further control for the state’s spending towards tobacco control activities, the fraction of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) recommendation that is spent on tobacco control, and the state population.29 The average state spends $25 million on tobacco control or only about 35% of the CDC recommended spending levels (Table 3).

V. Results

Main Analyses

Table 4 presents estimates of Equation (2), based on current month ST advertising exposure. Given that ST users are predominantly male (comprising about 88% of all users in 2009), the analyses are restricted to males. Appendix Table A1 presents models for the full sample.30 The baseline specification, presented in Model (1), shows that ST use among males responds positively to advertising exposure. The magnitude of the elasticity estimate of 0.05 is larger relative to the full sample (0.028 in column 1 in Table A1), suggesting that adult males are more responsive to advertising than adult females. A higher tax rate on snuff significantly reduces ST use. The cigarette excise tax is also negatively associated with ST use, suggesting that ST products and cigarettes are economic complements, at least contemporaneously and cross-sectionally. The somewhat higher magnitudes of both tax elasticities (relative to the overall sample) are suggestive of a higher own-tax and cross-tax response among males relative to females.31

Table 4.

Current ST Use & Current Ad Exposure among Males Probit Marginal Effects

| Model | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad Exposure - Current | 0.0617*** (0.0221) ε = 0.050 |

0.0644*** (0.0225) ε = 0.048 |

0.0728*** (0.0260) ε = 0.052 |

0.0635** (0.0319) ε = 0.045 |

| Snuff Tax | −0.0253** (0.0123) ε = −0.191 |

−0.0380 (0.0232) ε = −0.293 |

−0.0542** (0.0238) ε = −0.404 |

−0.0363 (0.0242) ε = −0.302 |

| Cigarette Tax | −0.0088** (0.0037) ε = −0.346 |

−0.0132** (0.0063) ε = −0.527 |

−0.0134** (0.0064) ε = −0.521 |

−0.0133** (0.0063) ε = −0.570 |

| Age | 0.0004 (0.0009) | 0.0005 (0.0009) | 0.0003 (0.0010) | 0.0007 (0.0008) |

| Age-squared (divided by 1000) | −0.0115 (0.0091) | −0.0126 (0.0091) | −0.0066 (0.0109) | −0.0138 (0.0087) |

| Black | −0.0382*** (0.0079) | −0.0359*** (0.0081) | −0.0375*** (0.0083) | −0.0340*** (0.0079) |

| Other Race | −0.0143* (0.0081) | −0.0141* (0.0080) | −0.0094 (0.0096) | −0.0143* (0.0081) |

| Hispanic | −0.0510*** (0.0089) | −0.0519*** (0.0083) | −0.0516*** (0.0104) | −0.0499*** (0.0081) |

| High School Graduate | −0.0038 (0.0057) | −0.0051 (0.0058) | 0.0012 (0.0067) | −0.0043 (0.0056) |

| Some College | −0.0250*** (0.0062) | −0.0260*** (0.0060) | −0.0207*** (0.0071) | −0.0248*** (0.0057) |

| College Graduate | −0.0312*** (0.0066) | −0.0324*** (0.0067) | −0.0240*** (0.0076) | −0.0310*** (0.0067) |

| Income | 0.0004 (0.0005) | 0.0004 (0.0005) | 0.0001 (0.0006) | 0.0003 (0.0005) |

| Employed | 0.0072 (0.0059) | 0.0073 (0.0059) | 0.0122* (0.0065) | 0.0068 (0.0060) |

| Unemployed | −0.0145 (0.0099) | −0.0150 (0.0099) | −0.0005 (0.0112) | −0.0181** (0.0088) |

| MSA County Resident | −0.0241*** (0.0045) | −0.0255*** (0.0049) | −0.0237*** (0.0046) | −0.0247*** (0.0047) |

| Number of Magazines Read | −0.0001 (0.0009) | −0.0001 (0.0009) | −0.0002 (0.0012) | 0.0717*** (0.0237) |

| Frequency of Mag. Reading | −0.0002 (0.0003) | −0.0002 (0.0003) | −0.0003 (0.0003) | −0.0008** (0.0004) |

| Attempt Smoking Cessation | 0.0216*** (0.0073) | |||

| Armed Forces - Current | 0.0260 (0.0182) | |||

| Armed Forces - Past | 0.0025 (0.0048) | |||

| Any Children under Age 12 | 0.0131*** (0.0050) | |||

| Magazine Group Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Magazine Indicators | No | No | No | Yes |

| Census Division Indicators | Yes | No | No | No |

| State Indicators | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Month Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 43983 | 43983 | 32747 | 43476 |

Notes: Average marginal effects from probit models are reported. All models adjust for sampling weights. Standard errors are adjusted for arbitrary correlation within state cells, and reported in parentheses. Elasticity estimates (ε) are computed at the sample means. All models also control for state-level measures including the state population, state tobacco control spending, and the percent of the CDC recommendation that the state spends on tobacco control, and also control for an indicator for state/periods where snuff is taxed as a percent of wholesale price. Statistical significance is denoted as follows:

p-value ≤ 0.01,

0.01 < p-value ≤ 0.05,

0.05 < p-value ≤ 0.10.

Appendix Table A1.

Current ST Use - All Adults Probit Marginal Effects

| Model | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad Exposure - Current | 0.0298*** (0.0103) ε = 0.028 |

0.0309*** (0.0104) ε = 0.029 |

0.0388*** (0.0121) ε = 0.034 |

0.0261 (0.0160) ε = 0.024 |

||||

| Ad Exposure - Stock | 0.0094*** (0.0035) ε = 0.030 |

0.0096*** (0.0036) ε = 0.031 |

0.0129*** (0.0041) ε = 0.040 |

0.0091* (0.0055) ε = 0.029 |

||||

| Snuff Tax | −0.0090 (0.0063) ε = −0.153 |

−0.0159 (0.0123) ε = −0.275 |

−0.0232* (0.0129) ε = −0.373 |

−0.0136 (0.0128) ε = −0.259 |

−0.0094 (0.0063) ε = −0.160 |

−0.0173 (0.0118) ε = −0.298 |

−0.0241* (0.0127) ε = −0.389 |

−0.0140 (0.0121) ε = −0.266 |

| Cigarette Tax | −0.0033* (0.0019) ε = −0.293 |

−0.0038 (0.0036) ε = −0.339 |

−0.0039 (0.0040) ε = −0.327 |

−0.0038 (0.0036) ε = −0.378 |

−0.0030 (0.0019) ε = −0.265 |

−0.0040 (0.0036) ε = −0.360 |

−0.0039 (0.0038) ε = −0.330 |

−0.0043 (0.0035) ε = −0.423 |

| Male | 0.0405*** (0.0031) | 0.0406*** (0.0032) | 0.0422*** (0.0033) | 0.0403*** (0.0032) | 0.0403*** (0.0033) | 0.0404*** (0.0033) | 0.0417*** (0.0034) | 0.0401*** (0.0032) |

| Age | 0.0003 (0.0004) | 0.0004 (0.0004) | 0.0004 (0.0005) | 0.0004 (0.0004) | 0.0004 (0.0004) | 0.0004 (0.0004) | 0.0005 (0.0005) | 0.0004 (0.0004) |

| Age-squared (divided by 1000) | −0.0069 (0.0042) | −0.0074* (0.0042) | −0.0063 (0.0055) | −0.0071* (0.0043) | −0.0069 (0.0042) | −0.0075* (0.0042) | −0.0069 (0.0053) | −0.0071* (0.0043) |

| Black | −0.0033 (0.0043) | −0.0027 (0.0043) | −0.0042 (0.0051) | −0.0043 (0.0035) | −0.0029 (0.0043) | −0.0022 (0.0044) | −0.0035 (0.0051) | −0.0038 (0.0036) |

| Other Race | −0.0067* (0.0039) | −0.0063* (0.0038) | −0.0041 (0.0046) | −0.0067* (0.0038) | −0.0067* (0.0041) | −0.0063 (0.0040) | −0.0044 (0.0050) | −0.0068* (0.0040) |

| Hispanic | −0.0248*** (0.0044) | −0.0252*** (0.0042) | −0.0245*** (0.0052) | −0.0240*** (0.0041) | −0.0247*** (0.0045) | −0.0250*** (0.0043) | −0.0239*** (0.0052) | −0.0238*** (0.0041) |

| High School Graduate | −0.0048 (0.0029) | −0.0053* (0.0029) | −0.0021 (0.0033) | −0.0050* (0.0029) | −0.0042 (0.0029) | −0.0047 (0.0029) | −0.0014 (0.0034) | −0.0044 (0.0028) |

| Some College | −0.0162*** (0.0031) | −0.0164*** (0.0029) | −0.0146*** (0.0034) | −0.0156*** (0.0030) | −0.0160*** (0.0032) | −0.0162*** (0.0030) | −0.0143*** (0.0035) | −0.0154*** (0.0031) |

| College Graduate | −0.0186*** (0.0036) | −0.0188*** (0.0034) | −0.0148*** (0.0038) | −0.0177*** (0.0035) | −0.0185*** (0.0036) | −0.0188*** (0.0034) | −0.0145*** (0.0038) | −0.0176*** (0.0035) |

| Income | 0.0002 (0.0002) | 0.0002 (0.0002) | 0.0001 (0.0003) | 0.0002 (0.0002) | 0.0002 (0.0002) | 0.0002 (0.0002) | 0.0001 (0.0003) | 0.0002 (0.0002) |

| Employed | 0.0034 (0.0024) | 0.0033 (0.0024) | 0.0047* (0.0026) | 0.0039* (0.0022) | 0.0035 (0.0025) | 0.0034 (0.0025) | 0.0047* (0.0027) | 0.0039* (0.0023) |

| Unemployed | −0.0047 (0.0050) | −0.0048 (0.0050) | 0.0005 (0.0055) | −0.0056 (0.0044) | −0.0044 (0.0051) | −0.0047 (0.0051) | 0.0006 (0.0054) | −0.0054 (0.0046) |

| MSA County Resident | −0.0120*** (0.0022) | −0.0133*** (0.0025) | −0.0128*** (0.0024) | −0.0125*** (0.0024) | −0.0121*** (0.0025) | −0.0138*** (0.0027) | −0.0135*** (0.0027) | −0.0129*** (0.0027) |

| Magazine Group Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Magazine Indicators | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Census Division Indicators | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| State Indicators | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Month Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 102992 | 102992 | 73427 | 102387 | 99789 | 99789 | 71522 | 99064 |

Notes: Average marginal effects from probit models are reported. All models adjust for sampling weights. Standard errors are adjusted for arbitrary correlation within state cells, and reported in parentheses. Elasticity estimates (ε) are computed at the sample means. All models also control for the individual’s total number of magazines read and their average magazine reading frequency, and state-level measures including the state population, state tobacco control spending, and the percent of the CDC recommendation that the state spends on tobacco control. Statistical significance is denoted as follows:

p-value ≤ 0.01,

0.01 < p-value ≤ 0.05,

0.05 < p-value ≤ 0.10.

The elasticity of ST use with respect to the snuff tax rate is estimated at −0.19. This tax rate elasticity can also be translated into the price elasticity for comparison. Specifically, by differentiating ST Use with respect to price, the price elasticity of ST can be related to the tax rate elasticity as follows:

| (5) |

Under reasonable assumptions, the adjustment factor above is approximately 2, suggesting a ST participation price elasticity of −0.38.32 This is comparable to the participation-price elasticity for cigarettes, which has been found to range from −0.3 to −0.6 in the literature (Chaloupka and Warner 2000). The elasticity of ST participation with respect to cigarette excise taxes is also negative (−0.35), indicative of complementarity between the two tobacco products.33 This cigarette excise tax elasticity can be translated into a price elasticity as follows:

| (6) |

Under reasonable assumptions, this adjustment factor is approximately 2.2, suggesting a cross-price elasticity of ST participation with respect to cigarette prices of −0.77.34 Given that ST users tend to have lower levels of education, the relatively large elasticity magnitude of ST with respect to cigarette prices is consistent with prior research that suggests a larger own-price response of cigarette use among low income individuals (Colman and Remler 2008).

The effects of the other covariates for both males and the full sample are consistent with the literature and follow patterns of use reflected across socio-economic factors (shown in Table 1). Individuals who are non-white and/or Hispanic are significantly less likely to currently use ST products, relative to whites and Hispanics. ST use also consistently decreases with educational attainment. This is consistent with prior studies which suggest that education makes individuals more allocatively efficient in producing health, and hence educated individuals are less likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as tobacco use (Grossman and Kaestner 1997). There are no significant effects of income on ST use, conditional on education and employment, though unemployed males are less likely to consume ST products (by about 1.5–1.8 percentage points) relative to males who are not in the labor force. This may partly reflect an income effect as well as a reduced demand for ST products if these individuals, who are not working and therefore not constrained by workplace or public smoking bans, have a lower need for ST. While age is insignificant, the coefficients suggest a mostly declining profile of ST use over the life cycle after early adulthood.

As prior studies have generally relied on cross-state variation to estimate the effects of ST and cigarette taxes on ST use, the tax responses may have been confounded by unobserved state-level heterogeneity. Specification (2) addresses this concern by including state fixed effects (instead of the census division indicators in the earlier specification). The tax effects remain negative for both ST and cigarette taxes, and the elasticity magnitudes become somewhat larger; however, the own-tax effect is imprecisely estimated due to the inflated standard error (p-value = 0.11).35 The effect of advertising exposure remains robust.

Model (3) controls for additional individual-level characteristics that are observed in the NCS. If the identifying variation in advertising exposure is plausibly exogenous and orthogonal to residual person-specific heterogeneity, then the advertising effects should not be sensitive to these additional controls. It is validating that the effect indeed remains robust, with an estimated elasticity of 0.052. Based on the marginal effects of the additional covariates, members of the armed forces have a higher likelihood of ST consumption (by about 2.6 percentage points) though the effect is statistically insignificant. Males who have previously attempted (either successfully or unsuccessfully) to quit smoking are significantly more likely to use ST (by about 2.2 percentage points). We note the caveat that ST use and quitting behaviors may be simultaneously determined. Nevertheless, this latter effect is consistent with studies which find that ST products are sometimes used as a path towards smoking cessation (Rodu and Phillips 2008), though whether they increase or decrease the chances of successfully quitting smoking remains unclear in the literature (see for instance, Rodu and Phillips 2008; Ramström and Foulds 2006; Tomar 2003). Males who have young children present in the household are significantly more likely to be ST users, possibly suggesting a substitution of ST for cigarettes in order to reduce children’s exposure to passive smoking.

The estimated marginal effects of magazine advertising exposure in Models 1–3 may potentially confound unobserved heterogeneity across persons based on the specific magazines that they read within a magazine category. That is, even among males who read news weeklies, for instance, there may be unobserved differences between those who read Newsweek and those who read Time, which may be correlated with their ST use. This may be reflective of targeting bias. The final model in Table 4 therefore includes magazine-specific fixed effects.36 These models exploit only the variation in ad exposure among individuals who read the same magazine but do so at different times since there is month-to-month variation in ad placement. The effect of advertising remains robust and statistically significant.

The advertising elasticities presented thus far capture the effects of advertising exposure in the interview month on current ST use. Given that advertising may have durable effects that linger over time, models in Table 5 are based on the stock of advertising exposure defined as the current month’s exposure plus a depreciation-weighted stock of exposure over the past six months. The effects of advertising are significant and robust across all specifications. The elasticity magnitudes are only slightly larger by about 15% (0.052–0.063 compared with 0.045 ~ 0.050), suggesting that, while there are some durable effects of magazine advertising exposure, most of the impact is short-lived.

Table 5.

Current ST Use & Ad Exposure Stock Probit Marginal Effects Males

| Model | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad Exposure - Stock | 0.0191** (0.0076) ε = 0.050 |

0.0199*** (0.0077) ε = 0.052 |

0.0247*** (0.0089) ε = 0.063 |

0.0200* (0.0103) ε = 0.052 |

| Snuff Tax | −0.0270** (0.0124) ε = −0.205 |

−0.0409* (0.0217) ε = −0.316 |

−0.0560** (0.0234) ε = −0.421 |

−0.0391* (0.0226) ε = −0.325 |

| Cigarette Tax | −0.0082** (0.0037) ε = −0.324 |

−0.0137** (0.0062) ε = −0.554 |

−0.0134** (0.0061) ε = −0.529 |

−0.0139** (0.0061) ε = −0.603 |

| Magazine Group Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Magazine Indicators | No | No | No | Yes |

| Census Division Indicators | Yes | No | No | No |

| State Indicators | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Month Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 42537 | 42537 | 31805 | 41872 |

See notes to Table 4.

Appendix Table A2 presents estimates from sub-analyses in order to assess differential responses to advertising and taxes across socio-demographic factors. All models control for the detailed magazine categories and the respondent’s magazine reading habits. The estimates should be interpreted cautiously in the context of reduced statistical power due to more limited sample sizes, though the patterns are suggestive of some systematic differences in the advertising and tax effects.

Appendix Table A2.

Current ST Use & Ad Exposure Stock Probit Marginal Effects Demographic Sub-populations among Males

| Model Sample | (1) Ages 25 & up1 | (2) Ages 18–34 | (3) Ages 35–54 | (4) White2 | (5) Less than College Educated | (6) College Graduate or above | (7) MSA Resident | (8) Non-MSA Resident |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad Exposure - Stock | 0.0221** (0.0091) ε = 0.056 |

0.0372** (0.0163) ε = 0.081 |

0.0380** (0.0150) ε = 0.081 |

0.0185** (0.0075) ε = 0.045 |

0.0250** (0.0106) ε = 0.052 |

0.0145 (0.0095) ε = 0.066 |

0.0070 (0.0055) ε = 0.031 |

0.0306** (0.0130) ε = 0.050 |

| [p = 0.587] | [p = 0.955] | [p = 0.393] | [p = 0.949] | [p = 0.597] | ||||

| Snuff Tax | −0.0481** (0.0243) ε = −0.369 |

0.0280 (0.0670) - |

−0.0235 (0.0336) ε = −0.173 |

−0.0806** (0.0320) ε = −0.525 |

−0.0562** (0.0235) ε = −0.364 |

0.0355 (0.0336) - |

−0.0310** (0.0155) ε = −0.699 |

−0.0413 (0.0415) ε = −0.188 |

| [p = 0.501] | [p = 0.476] | [p = 0.000] | [p = 0.029] | [p = 0.448] | ||||

| Cigarette Tax | −0.0099 (0.0060) ε = −0.395 |

−0.0405** (0.0159) ε = −1.706 |

−0.0052 (0.0091) ε = −0.197 |

−0.0112 (0.0092) ε = −0.387 |

−0.0141** (0.0062) ε = −0.495 |

−0.0081 (0.0109) ε = −0.554 |

−0.0040 (0.0032) ε = −0.447 |

−0.0222** (0.0113) ε = −0.546 |

| [p = 0.081] | [p = 0.064] | [p = 0.004] | [p = 0.957] | [p = 0.433] | ||||

| Magazine Group Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| State Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Month Indicators | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 38350 | 10208 | 16761 | 32962 | 30933 | 10852 | 27448 | 14711 |

See notes to Table 4. P-values for test of the difference in the coefficient between groups are presented in brackets.

P-values test difference relative to the full sample.

P-values test difference relative to non-Whites.

We do not find any statistically significant differences in the advertising response, though the advertising elasticity is suggestively higher (0.081) among adults ages 18–54 relative to older adults. We find that the magnitude of the cross-elasticity of ST use with respect to the cigarette excise tax is significantly higher among younger adults (ages 18–34), suggesting that these tobacco products are stronger economic complements than for older adults. This latter effect is consistent with some studies that also find higher own-tax elasticities for cigarette use among youths (Chaloupka and Warner 2000). Furthermore, the stronger complementarity is also consistent with descriptive evidence from the NCS, which suggests a greater prevalence of concurrent use of both cigarettes and ST among young adult males. A significantly higher fraction of young adult male smokers use ST (8.8%) relative to older adult male smokers (4.4%); use of ST is also significantly higher among young adult males who have tried to quit smoking (16.1%) versus similar older adult males (8.1%). The effect of the snuff tax rate is significantly higher among whites, and higher cigarette excise taxes elicit a significantly smaller decrease in ST use among whites relative to non-whites. The negative own-tax response is significantly larger among low-educated males; this is consistent with studies that also find a larger elasticity of smoking with respect to the cigarette tax among low-income individuals (Colman and Remler 2008).

Robustness Checks

We implement several checks to assess plausibility and verify that the results are not driven by unobserved heterogeneity across individuals.37 Smokeless tobacco ads appeared in 42 magazines at varying points over the sample period. About 32% of males do not read any of these 42 magazines. Omitting them from the analysis sample does not materially change the average marginal effects of advertising exposure.38

We also construct three alternate measures of magazine advertising exposure, which: 1) is based on advertising expenditures rather than expenditure adjusted for audience size; 2) adjusts for the log of the magazine’s circulation (rather than linear circulation) to account for the potential diminishing returns to circulation with respect to advertising rates, consistent with the finding in Koschat and Putsis Jr. (2002); and 3) adjusts for the square of the magazine’s circulation to account for potential increasing returns to circulation on advertising rates. The advertising elasticity and tobacco tax elasticity estimates remain robust and similar to those presented above.

As a placebo test, we follow Avery et al. (2007) and introduce future advertising exposure into the models. If we find that future ads have a significant impact on current ST consumption, then this indicates unobserved heterogeneity across individuals who are reading the same magazines but are being exposed to different levels of ads (based on which issues they read), suggestive of residual targeting bias.39 It is therefore validating that the effects of current ad exposure and the ad exposure stock remain robust (in terms of significance and effect magnitude), and the effects of future ad exposure are insignificant and close to zero. Specifically, the marginal effect of the future month’s ad exposure is −0.01 (compared to 0.08 for contemporaneous ad exposure) and the marginal effect of the stock of future six months’ ad exposure subsequent to the interview month is −0.005; both are statistically insignificant.

One concern with using any ST use as the outcome is that it potentially conflates two separate behaviors, namely initiation into ST use and current participation conditional on initiation. The NCS does not contain any information on the onset age or initiation of ST use. However, data from the NSDUH (2009 and 2010) suggest that the vast majority of male users (90%) initiate the consumption of ST products prior to age 25. Model (1) in Appendix Table A1 therefore restricts the sample to males ages 25 and older in order to bypass initiation effects and to obtain cleaner estimates of the ST participation elasticity with respect to advertising and taxes. The advertising elasticity estimate is not substantially or statistically different from that estimated for all adult males, suggesting that both initiation and participation in ST use are responsive to advertising. The tobacco tax elasticities are also robust to excluding males between the ages of 18–24.

VI. Discussion

While the prevalence of smokeless tobacco (ST) is relatively low compared to smoking, the distribution of ST use is highly skewed with consumption concentrated among certain segments of the population (rural residents, males, whites, low-educated). In addition, there is suggestive evidence that use has trended upwards recently for certain groups, which have traditionally been at low risk of using smokeless tobacco (for instance, Hispanics, females, older adults, urban residents), and thus diffusing across demographics. While these trends may be driven by various factors, they are consistent with a shifting landscape in the tobacco market with ST manufacturers re-allocating promotion towards price-based discounting and magazine advertising as other media (television, radio, billboards, transit vehicles, sports and entertainment venues, malls) were banned from carrying ST ads.

This study is the first to estimate the effects of ST magazine advertising on ST use at the population level. Empirically identifying the causal effects of advertising is a challenge in the literature. We address this challenge by exploiting plausibly exogenous variation in person-specific exposure to ST ads based on the 2003–2009 National Consumer Survey, a novel national dataset that contains in-depth information on individuals’ magazine reading habits. Moreover, no study has investigated the simultaneous effects of ST advertising, ST tax rates, and cigarette taxes on ST use, and most of the estimates of the tax response in the literature are based on cross-state variation and on pre-1998 (pre-STMSA and pre-MSA) data when the tobacco marketplace was different.

We find consistent and robust evidence that exposure to magazine advertising raises the probability of using ST products, especially among males. These effects also inform the broader debate on whether advertising in the tobacco market impacts upon primary demand; the results from this study suggest that advertising is effective in raising the overall market for ST and does not represent solely a brand-shifting process as claimed by the industry (Saffer and Chaloupka 2000). The elasticity of ST use with respect to the stock of ad exposure is estimated to be about 0.06 for the adult male population. This positive market response suggests that advertising of ST products can be an effective tool if the goal is to expand ST use as part of an overall tobacco harm-reduction approach.

At the same time, Healthy People 2020 aims at reducing the overall prevalence of ST use among adults by two percentage points, from 2.3% to 0.3%.40 Since the prevalence rate of ST use among females is currently only 0.5%, most of the decrease would need to be realized for males who have a relatively high prevalence of ST use. Banning advertisements of ST from magazines would reduce the prevalence of ST use among males by about 0.3 percentage point, ceteris paribus, and close about 15% of the gap between current use and the stated Healthy People 2020 objective. However, any policy deliberation aimed at making it difficult for manufacturers to market ST products (for instance, as is being considered by the FDA with respect to MRTP applications) would also need to weigh the potential benefits of ST promotion in reducing tobacco-related harms.

We also find some suggestive evidence that ST taxes may lower the use of ST (estimated own-tax elasticity of −0.32) among males.41 Wisconsin currently imposes the highest tax rate on snuff at 100% of the wholesale price, which compares to a national average (excluding WI) of 31.5%. Raising the ST tax rate to 100% among all states could reduce adult males’ ST use by approximately 2.5 percentage points, ceteris paribus, which would further narrow about 60% of the gap between current use and the target proposed in Healthy People 2020. However, here as well, a proper accounting of any policy aimed at raising the cost of ST would need to consider potential implications for public health given that some smokers who otherwise may have used ST as a path toward smoking cessation may now be discouraged from using ST due to the higher cost.