Abstract

Lanthanide ions luminescence has long life time enabling highly sensitive detection in time-gated mode. The synthesis of reactive lanthanide probes for covalent labeling of the objects of interest is cumbersome task due to the large size of the probes, complex multi-step procedures and the presence of sensitive groups, which often prevents introduction of reactive cross-linking functions optimal for conjugation. We suggest simple synthetic protocol for luminescent europium chelates based on serendipitous reaction yielding acylating compounds, whose reactivity is comparable to that of commonly used N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters. The probes react with proteins at pH 7.0 within several minutes at ambient temperature displaying high coupling efficiency. The resulting conjugates survive electrophoretic separation under denaturing conditions, which makes the labels useful in proteomic studies that rely on high detection sensitivity.

Keywords: Lanthanide, luminescence, chelate, amine-reactive, labeling, synthesis

1. Introduction

Unusually long emission time for lanthanide ion luminescence (from microseconds to milliseconds range) allows time-gated detection mode, which greatly increases detection sensitivity compared to conventional fluorophores, whose light emission is short-lived (1–9). Also, lanthanide ion emission has sharply spiked fingerprint-like spectra facilitating discrimination from the background fluorescence. Large Stokes shift (the spectral distance between the excitation and emission maxima) provides excellent spectral discrimination between the excitation and emission light further contributing to detection sensitivity, which is about 1000 times higher in comparison with regular fluorescent labels. Due to small molar extinction of a lanthanide ion it has to be sensitized, which is achieved by tethering (through a chelating group) to an antenna (organic fluorophore) that absorbs excitation light and transfers excitation energy to the lanthanide ion. The excited lanthanide ion emits the light, which can be sensitively detected. In addition to keeping a lanthanide ion close to the antenna fluorophore, the chelating group prevents coordination of water by the ion, strongly increasing the quantum yield of the emission. A luminescent probe also contains cross-linking group for conjugation of the label to a biomolecule of interest. The necessity to combine these three functional units in the same probe and the presence of chemically sensitive groups in the synthetic intermediates complicates the synthetic procedure, thereby preventing introduction of optimal cross-linking groups, active under physiological conditions. In the present study we describe a simple protocol to obtain amine-reactive acylating Eu3+ luminescent chelates (shown in Fig. 1), which does not require chromatographic purification steps and can be achieved in one, or two working days. These reactive chelates are highly soluble in water and conjugate to proteins in neutral media at ambient temperature within 1–2 min. The probes are especially useful for labeling sensitive biological materials which are not stable at elevated pH or temperature.

Fig. 1.

The structure of reactive luminescent Eu3+ chelates.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis

The following reagents were purchased from Aldrich: Avidin, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid dianhydride (DTPA), triethylamine, 1,3-phenylenediamine, ethyl 4,4,4-trifluoroacetoacetate, 1,3- dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), ethylenedianime, methylbromacetate, anhydrous sodium sulfate, dimethylformamide (DMF) and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), 1-butanol, ethylacetate, chloroform, acetonitrile, ethanol, sodium and potassium hydroxide, EuCl3, silicagel TLC plates on aluminum foil (200 µm layer thick with a fluorescent indicator). Ethyl-3-bromopropionate was from TCI America. Distilled and deionized water (18 MΩ cm−1) was used. All experiments including lanthanide complexes preparation and using thereof were performed either in glassware washed with mixed acid solution and rinsed with metal-free water, or in metal-free plasticware purchased from Biorad. All chemicals were the purest grade available.

2.1 Probe 5

2.1.1. 7-Amino-4-trifluoromethyl-3-carboxymethyl-2(H) quinolone (cs124CF3-CH2COOH, Compound III of Fig. 2A), improved protocol

Fig. 2.

Synthetic route for probe 5 (A) and reactions for model compounds (B).

To a mixture of 2.2 ml (15 mmol) of 4,4,4- trifluoroacetoacetate and 1.5 ml (15 mmol) of methylbromoacetate in 5 ml of DMF 0.86 g (15 mmol) of powdered KOH was slowly added under vigorous agitation. The agitation was continued for 30 min and the mixture kept for 1 h at 60 °C, followed by addition of 50 ml of water and extraction with chloroform. Organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and evaporated in vacuo first at room temperature and then at 80 °C until the remaining 4,4,4-trifluoroacetoacetate was completely removed leaving ca. 2 g of crude trifluoroacetylmethylethylsuccinate (compound II of Fig. 2A). This residue was dissolved in 5 ml of DMSO and supplemented with 0.8 g (7.5 mmol) of 1,3-phenylenediamine and 200 mg (1.5 mmol) of anhydrous ZnCl2. The mixture was heated for 1 h at 110 °C, combined with 1.5 ml of 10 M KOH and incubation continued at 80 °C for another 15–20 min under agitation. The residue was separated by centrifugation, and the resulting solution mixed with 70 ml of water, followed by extracted with ethylacetate (2×100 ml). Water layer was acidified by 8 ml of 1 M citric acid to pH 3 and re-extracted with ethylacetate (3×100 ml). Organic layers were combined and after drying over Na2SO4 evaporated in vacuo. The residue was washed with hot acetonitrile (3×7 ml) and dried under reduced pressure. The yield was 420 mg.

2.1.2. Probe 5

DTPA dianhydride (25 mg, 70 µmol) was dissolved in 0.2 ml of DMSO under heating (80 °C). This solution was supplemented with 11.8 mg (45 µmol) of compound III and the mixture agitated to dissolve the compound. After incubation for 10 min at 70 °C the mixture was poured into 4 ml of ether. The residue was suspended in 0.3 ml of dioxane followed by addition of 0.2 ml of water. After 10 min incubation at room temperature 10 ml of butanol and 4 ml of water were subsequently added to the solution. After extraction the organic layer was collected and titrated under agitation with 0.1 M aqueous solution of EuCl3 until the maximum level of luminescence at 615 nm was achieved under excitation at 347 nm. Butanol phase was collected and evaporated in vacuo to the volume about 1 ml and the solution left for 20 min at 4 °C. The precipitate was collected, subsequently washed with butanol and ether and dried in vacuo to afford 6 mg of the product IV of Fig. 2A. The residue was dissolved in 0.1 ml of DMSO/DMF mixture (1:1) and supplemented with 30 mg of DCC. After 2 h incubation at 0 °C the reaction was nearly complete as judged by treatment of an aliquot with 10 mM ethylenedianime pH 8.0 and subsequent TLC analysis in acetonitrile – water (3:1) developing mixture. The residue (dicyclohexylurea) was removed by centrifugation and the solution was poured in 1 ml of ether. The product was collected by centrifugation, washed by ether (3×1 ml), re-dissolved in 0.1 ml of DMSO, precipitated and washed by ether and dried in vacuo yielding 4.5 mg of probe 5. MS: Compound IV (Eu-DTPA-cs124-CF3CH2COOH) (−1) 809.1 (found, traces), (809 calcd); -Eu, +4H+ 662.2 (found, main signal), 662.0 (calculated). Probe 5 after reaction with butylamine (Eu-DTPA-cs124-CF3CH2CO)- NHBu) (−1) 864.01 (found, traces), 864.0 (calcd); -Eu, +4H+ 716.12 (found, main signal), 716.0 (calcd).

2.2. Probe 6

2.2.1. 7-Amino-4-trifluoromethyl-3-carboxyethyl-2(H) quinolone (cs124CF3-CH2CH2COOH, Compound XI of Fig. 3A

Fig. 3.

Synthetic route for probe 6 (A) and reactions of model compound (B).

To 2.2 ml (15 mmol) of 4,4,4-trifluoroacetoacetate 0.86 g (15 mmol) of powdered KOH was slowly added under rigorous agitation and refrigeration by ice. To this mixture 1.9 ml (15 mmol) of ethyl-3-bromopropionate was added and incubation continued for 3 h at 60 °C. The residue (KBr) was removed by centrifugation, followed by addition of another 0.5 g of KOH and 0.9 ml of ethyl-3-bromopropionate. After overnight incubation at 60 °C the mixture was supplemented with 5 ml of water and extracted with chloroform. Organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure to remove volatile and unreacted components affording 1 g of crude trifluoroacetyldiethylglutarate (compound X of Fig. 3A). This residue was dissolved in 2 ml of DMSO and supplemented with 0.4 g (3.7 mmol) of 1,3-phenylenediamine (compound I) and 100 mg (0.75 mmol) of anhydrous ZnCl2. The mixture was heated for 1.5 h at 110 °C, combined with 0.75 ml of 10 M KOH and incubation continued at 60 °C for another 30 min under agitation. The precipitated zinc hydroxide was separated by centrifugation, and the resulting solution mixed with 20 ml of water, followed by extraction with ethylacetate (2×40 ml). Water layer was acidified by 4 ml of 1 M citric acid to pH 3 and re-extracted with ether (3×50 ml). Organic layers were combined and after drying over Na2SO4 evaporated in vacuo. The residue was suspended in 3–4 ml of hot acetonitrile under agitation and left at 4 °C. The precipitate was collected, washed with hot acetonitrile (3×1 ml) and dried in vacuo. Yield 90 mg. 1H NMR chemical shifts (d) in DMSO were as follows: 2.31 (t 2H, - CH2COOH, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.91 (2H broad, -CH2CH2COOH), 6.02 (s 2H broad, 7NH2), 6.42 (1H, 8H), 6.53 (dd 1H, 6H, J1= 9 Hz, J2 = 2.4 Hz). 7.40 (m 1H, 5H).

2.2.2. Probe 6

DTPA acylation of compound XI and the synthesis of corresponding Eu3+ chelate were performed as in the case of probe 5 starting from 20 mg of compound XI and yielding 20 mg of compound XII. Subsequent reaction of the compound XII with DCC was performed in the mixture (1:1) of anhydrous DMF and DMSO (2 mg, ~3 µmol of the compound in 0.1 ml of the solvents mixture) at 0 °C in the presence of 25 mg (0.12 mmol) of DCC and 10 µmol of pyridine hydrochloride. After 30 min incubation the precipitated dicyclohexylurea was separated by centrifugation, the residue washed with DMSO, and combined solution mixed with 1 ml of ether. After centrifugation the precipitate was washed with ether (3×1 ml), dried over P2O5, dissolved in desired volume of DMSO and stored at −80 °C. MS: Compound XII (Eu-DTPA-cs124-CF3CH2CH2COOH) (−1) 823.1 (found, traces), 823.0 (calcd); -Eu, +4H+ 676.2 (found, main signal), 676.0 (calculated). Probe 6 after reaction with butylamine (Eu-DTPA-cs124-CF3CH2CH2C(O)- NHBu) (−1) 878.2 (found, traces), 864.0 (calcd); -Eu, +4H+ 731.12 (found, main signal), 731.0 (calcd).

2.3. Reaction of probes 5 and 6 with amines

One – two microliters of 20–40 mM solution of a probe was mixed with 9 µl of 0.1 M butylamine –HCl pH 10.5, or 0.1 M ethylenediamine-HCl pH 8.0. After 5 min incubation at ambient temperature the mixtures were analyzed by TLC in acetonitrile – water (3:1) developing system. Reaction products with butylamine were purified in the same system and used for MS analysis.

2.4. Compounds VIa and VIIIa of Fig. 2B

Suspension of 12 mg (45 µmol) of compound IIIa in 1 ml of THF was supplemented with 25 mg (140 µmol) of DCC. After 30 min incubation at ambient temperature under rigorous agitation the TLC analysis in the system chloroform- ethanol (2:1) revealed fluorescent reaction product with Rf = 0.8 (compound VIa). A small portion of the reaction mixture was applied on silicagel plate and compound VIa was purified in the system hexane – acetone (2:1). The product was eluted by acetonitrile and the solution kept at −20 °C. The rest of the reaction mixture was supplemented with two-fold molar excess of butylamine and the reaction product VIIIa purified by silicagel column chromatography in hexane-acetone (1:1) solvent system. Yield 10 mg.

2.5. Compound IIIb of Fig. 2B

The solution of 20 mg (74 µmol) of compound III in 0.2 ml of DMF was supplemented with 20 µl (200 µmol) of acetic anhydride and the mixture kept at 37 °C. After 2 h incubation the acylation product (deep blue fluorescence) was purified by TLC in ethylacetete developing system. Yield 15 mg.

2.6. Compounds VIb and VIIIb of Fig. 2B

They were obtained as described above for non-acylated compounds VIa and VIIIa of Fig. 2B.

2.7. Compound XIII of Fig. 3B

This was obtained essentially as compound VIa, but at 0 °C. The reaction time course was monitored by TLC in hexane – acetone (2:1 developing system). The compound was purified by preparative TLC in the same solvent system.

2.8. Compound XIV of Fig. 3B

It was obtained as described above for compound VIIIa.

2.9. Time course for hydrolysis of compounds VIa,b and XIII

The reactions were performed in fused silica cells in water buffered solutions as indicated in the Figs 5 and 6 legends. UV spectra of the reaction mixtures were recorded at time intervals indicated in the legends.

Fig. 5.

Light absorbance spectra recorded upon hydrolysis of model compound VIb at indicated time intervals in 10 mM H3BO3-Na2B4O7 pH 9.0 (A) and 10 mM NaAc pH 5.0 (B).

Fig. 6.

Change in light absorption spectra accompanying hydrolysis of compound VIa (A) and compound XIII (B) in 10 mM NaAc pH 5.0.

2.10. Modification of avidin, BSA, E.coli RNA polymerase, and whole cell lysate by probes 15, and 6

The reaction cocktails (10–16 μl) were composed by mixing of 7 µl of avidin (20 mg/ml), or BSA (10 mg/ml), or E.coli RNAP (5 mg/ml), 1 µl of 1 M buffer of desired pH (indicated in the legend to Fig. 8), and 1–8 µl of a reactive probe DMSO solution to provide final probe concentrations specified in Figs. 7–9 and their legends. After incubation for 1–20 min at 20 °C the mixtures were diluted to 100 µl by water and subjected to size-exclusion chromatography on Sephadex G-50 “medium” in 10 mM Hepes-HCl buffer pH 8.0 containing 50 mM NaCl. In the case of probe 1 the coupling was performed at pH 10.0, 56 °C during 4 h. The fractions corresponding to modified protein were collected by visual detection using UV monitor (365 nm light). In some cases precipitation of the modified protein was observed during gel-filtration due to change of the protein’s isoelectric point. To avoid precipitation the separation of these samples was performed at pH 10.0 For labeling of E.coli lysate K12 bacterial cells were grown to the density ca. 109 cfu/ml in 500 ml of LB culture medium, harvested by centrifugation and re-suspended in 5 ml of 10 mM tris- HCl buffer containing 0.2 M NaCl, and PMSF (25 mg/l). The cells were disrupted using French Pressure device, followed by centrifugation (8000 rpm for 30 min at 0 °C) and desalting of the lysate on Sephadex G-50 column as described above. A portion of the size-exclusion fraction (100 µl) was supplemented with 11 µl of 1 M sodium borate buffer pH 8.0 and probe 6, or 1 DMSO solution (final concentration 3–10 mM). After10 min incubation at 20 °C the sample was subjected to size-exclusion chromatography and analyzed as described below.

Fig. 8.

Absorbance of BSA modified by probes 5 and 6 at various pH at concentration of the probes 8 mM. The following 0.1 M buffers were used: PIPES pH 7.0, HEPES pH 8.0, H3BO3-Na2B4O7 pH 9.0, and 10.0.

Fig. 7.

(A) Dependence of the number of the attached probes on the probes concentration in the reaction of BSA modification carried in 0.1M H3BO3-Na2B4O7 at pH 9.0. (B) Dependence of the BSA luminescence on the number of attached probes.

Fig. 9.

Time course for modification of BSA by probe 6 [8 mM] at pH 7.0.

2.11. Electrophoretic separation of the modified proteins

The modified proteins were denatured by addition of SDS to final concentration 1 % and subjected to separation by DISC electrophoresis in Laemmly system (10) using 10 % resolving polyacrylamide gel.

2.12. Physical Methods

Continuous excitation and emission fluorescence spectra were recorded using QuantaMaster 1 (Photon Technology International) digital fluorimeter at ambient temperature. UV absorption spectra were recorded on Cary 300 Bio UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Varian). Mass spectra were obtained at the Center for Advanced Proteomics Research (UMDNJ) using MALDI-TOF detection mode. NMR spectra were recorded by Process NMR Associates on Varian Mercury-300 superconducting NMR spectrometer operating at 300 MHz.

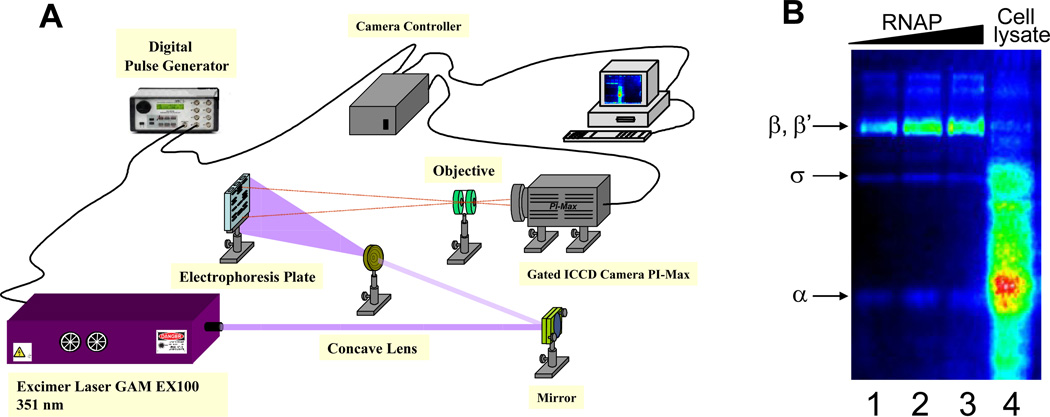

2.12.1. Time-resolved proteins imaging after SDS PAGE separation

The scheme of the imaging device is shown in Fig. 11A. The excitation light from an eximer laser driven by a pulse generator was directed to the gel slab using a concave lens. The light emitted from the gel was collected (after 50 µs delay) by an objective and focused on the photocathode of an ICCD camera. The signal was accumulated from 1000 frames and displayed on the computer screen.

Fig. 11.

(A) The scheme of home-built device for time-resolved imaging of protein slab gels. (B) Time-resolved gel image after SDS PAGE separation of the samples containing E. coli RNA polymerase subunits (lanes 1–3) and whole cell E.coli lysate (lane 4) labeled by probe 1.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The synthesis and properties of the reactive probes, synthetic intermediates, and model compounds

Lanthanide chelates of carbostyril fluorophores (cs124 and cs124CF3) represent attractive luminescent labels due to high quantum yield and high solubility in water (11–17). In our previous study (18) we improved the existed probes by increasing retention of coordinated lanthanide, which also enhanced the probes brightness by elimination of water from the metal coordination sphere (19). However, our probes required elevated temperature and/or prolonged incubation for coupling, which could complicate the labeling of unstable proteins or their complexes. This problem can be addressed by using more reactive probes. However, the synthesis of such probes is problematic due to possible side reactions and due to specifics of currently used synthetic strategy in which the cross-linking group is introduced before DTPA acylation reaction. This restricts the possible choice of the crosslinking groups by those able to survive the conditions of DTPA acylation and subsequent purification procedures. Introduction of the crosslinking group after DTPA acylation is complicated by the presence of reactive DTPA carboxylate groups. The solution suggested in the previous study (20) takes advantage of cs124 antenna-fluorophore acylation by one of the reactive group of DTPA dianhydride, while the second highly reactive anhydride function is reserved for the attachment to an object of interest. However, this approach suffers some major deficiencies, which are: i) reduction of Ln3+ retention in the probe due to elimination of one chelating carboxylate group; ii) reduction of Ln3+ quantum yield due to coordination of additional water molecule (caused by elimination of a chelating carboxylate group), and iii) the necessity to add a lanthanide after attachment of the probe (which can cause undesirable lanthanide chelation to other sites of biomolecule). In the present study we synthesized reactive lanthanide probes free of the above shortcomings. The strategy takes advantage of previously described by us intermediate compound IIIa (Fig. 2A). Using fortuitous catalytic effect of strong base on the reaction producing compound IIIa from the precursor (21) we significantly improved the yield and simplified the synthesis of this compound. Further we noticed that treatment of compound IIIa with DCC yields an active acylating intermediate. In the present research we examined this reaction in more details. It was found that reaction of IIIa with DCC yields reactive product VIa (Fig. 2B) through intramolecular attack of the fluorophore’s 2-oxo group on activated carbon of intermediate acylisourea derivative Va. The same reaction was observed with a model compound IIIb in which 7-aminogroup was acetylated (as in the lanthanide chelate). The corresponding reaction product (VIb) possessed distinctive UV absorption spectrum (Fig. 4), which was strongly pH dependent, suggesting tautomeric equilibrium with enole form (structure VIIb of Fig. 2B), capable of ionization. Apparent pKa value inferred from the UV spectra recorded at various pH was 7.9, which is expected for this compound. Compound VIb reacted with water with half-reaction time of 4 min at pH 9.0 (Fig. 5A) and 15 min at 20 °C at pH 5.0 (Fig. 5B), producing the original product IIIb as judged by the characteristic transition of the UV absorption spectrum and by TLC analysis. Compound VIa displayed the same spectral behavior upon reaction with water with half-life time equal to 20 min at pH 5.0 (Fig. 6A). Incubation of compounds VIa,b with amines yielded acylation products, corresponding amides VIIIa,b. Next, we investigated whether analogous cyclization reaction can proceed with DTPA-acylated derivative of compound III chelated with lanthanide (compound IV). We reasoned that chelation would protect carboxylate groups of DTPA residue from reaction with DCC, while 3-carboxymethyl group of quinolone moiety (not involved in chelation) should retain reactivity. Indeed, incubation of Eu3+ chelate IV with DCC in DMSO yielded expected compound, probe 5 (Fig. 2A). The probe numbering continues from our previous publications (18, 22). The best yield of the reactive compound was achieved by carrying the reaction at low temperature (0 °C) and adding a half equivalent of a base, triethylamine. Like model compound VIb probe 5 displayed characteristic changes in light absorption spectrum upon hydrolysis with nearly the same conversion rate (not shown).

Fig. 4.

Light absorbance spectra for model compound VIb at various pH. The following 10 mM buffers were used: MES pH 6.0, PIPES pH 7.0, HEPES pH 8.0, H3BO3-Na2B4O7 pH 9.0, and 10.0

For the synthesis of probe 6 we used the same strategy. We alkylated 4,4,4- trifluoroacetoacetate by ethyl-3-bromopropionate in the presence of a base to obtain trifluoroacetyldiethylglutarate (compound X of Fig. 3A). The yield of the compound was lower than for corresponding synthetic intermediate for probe 5, compound II) due to lower reactivity of alkylating agent and due to its side reaction leading to ethylacrylate. As expected, incubation of compound X with 1,3-phenylenediamine afforded reaction intermediate, which rapidly converted to desired fluorophore XI upon subsequent treatment with KOH. By analogy with compound IIIa, incubation of product XI with DCC resulted in accumulation of the cyclic derivative XIII (Fig. 3B) with increased mobility on TLC. At pH 5.0 the product XIII had UV absorption spectrum similar to that of VIa (compare Figs 6A and B). Like compound VIa this product reacted with water displaying similar reactivity (half-reaction time 40–45 min at 20 °C) and yielding the original compound XI (Fig. 3B), or with butylamine, producing corresponding amide (compound XIV). As expected, in contrast to compound VIa, light absorption spectrum for compound XIII was pH-independent indicating the absence of the tautomeric form.

DTPA acylation of compound XI followed by EuCl3 addition produced corresponding chelate XII with high yield. Reaction of XII with DCC resulted in cyclization (Fig. 3A) by analogy with the synthesis of probe 5 producing probe 6. The reaction was strongly accelerated (~10–20 fold) in the presence of acid catalyst, pyridine hydrochloride allowing nearly quantitative yield of the probe. Notably, an attempt to use the catalyst in the case of probe 5 was not successful.

3.2. Conjugation of probes 5 and 6 to avidin and BSA

The reactivity of the synthesized probes was tested in conjugation reaction with avidin and BSA. Changing the probes concentration from 1 to 16 mM resulted in progressive increase of the number of the attached luminescent chelates (Fig. 7). Specifically, about 23–24 luminescent residues could be attached to BSA at 16 mM probes concentration, which is close to the number of accessible Lys residues in the protein. The dependence of the conjugation efficiency of probes 5 and 6 to BSA on the reaction mixture pH is shown in Fig. 8. Remarkably, the coupling efficiency for the probes was the same both at elevated and neutral pH (at the conditions where most of Lys residues are reversibly protonated and therefore non-reactive). This suggests high reactivity of the probes towards BSA lysine residues compared to the probes hydrolysis rate. As seen from the conjugation time course for probe 6 (Fig. 9) the reaction was complete in 5 min, reflecting high acylation rate. Essentially the same conjugation efficiency was observed for avidin.

3.3. Fluorescent properties of the reactive probes and their conjugates

The luminescence spectra for the non-reactive forms of the probes (compounds IV and XII) were identical to those published previously (18) for this class of compounds. Close distance of the coordinated Eu3+ ion to the antenna fluorophore revealed by X-ray analysis (23) provides efficient energy transfer resulting in bright emission. The dependence of the BSA conjugate light emission intensity on the number of the attached probes 5 and 6 displayed beneficial non-linear enhancement (Fig. 7B), suggesting synergistic effect (22, 24). As follows from the emission spectra (Fig. 10) this was due to improved antenna-to-lanthanide energy transfer in heavily labeled BSA conjugates as evidenced by increased lanthanide-to-antenna emission ratio in BSA conjugated probe compared to non-conjugated chelate. Lanthanide emission of the labeled protein increased two-fold in deuterium oxide due to suppression of the non-radiative energy dissipation (19) caused by coordinated water.

Fig. 10.

Light emission of the hydrolyzed probe 6 (compound XII) and of the same probe attached to BSA at the labeling density equal to 24 probes/BSA. In the last case the cumulative emission signal was normalized to the number of the attached probes to infer the emission intensity for single attached probe.

3.4. Time-resolved imaging of the proteins labeled by the luminescent probes after electrophoretic separation in denaturing conditions

Strong retention of the lanthanide ion in the labeled biomolecules is a necessary pre-requisite for using the probes in some biological applications (e.g. proteomic studies), which include electrophoretic separation or incubation of the labeled proteins in highly chelating media. To this end we examined light emitting properties of protein conjugates at the conditions of electrophoretic separation. Specifically we incubated BSA – probe 6 conjugate in separation buffer for discelectrophoresis containing 0.125 M Tris, 0.4 M glycine and 0.1 % SDS. As indicated by the light emission measurements, prolonged incubation (80 min) only slightly reduced the brightness of the conjugate (by ca. 15%), reflecting high stability of our luminescent probes. This was further confirmed by separation of purified E.coli RNA polymerase and the proteins of E.coli whole cell lysate labeled by luminescent Eu3+ chelates (Fig. 11B). In these experiments probes 5 and 6 were used along with previously synthesized probe 1. Even though the labeling efficiency was nearly the same for all probes the coupling of probe 1 required drastic incubation conditions (see experimental section). After separation the labeled proteins were imaged in time-resolved mode by acquisition of the signal from multiple pulsed excitations using the device shown in Fig. 11A. In this setup the excitation light from eximer laser was directed to the gel using concave lens. The emitted light from the gel was collected (after small delay) through an objective to the entrance of imaging spectrograph and further enhanced by ICCD camera. As expected, the image was highly contrast.

4.DISCUSSION

In the present research we developed simple synthetic protocol for highly reactive luminescent Eu3+ chelates. The strategy takes advantage of intramolecular reaction of pre-formed lanthanide complex with DCC in non-aqueous medium, which is accompanied by quinolone-to-quinoline conversion of the antenna fluorophore thereby yielding highly reactive acylating derivative. This reaction involves exclusively carboxylate group in position 3 of fluorophore ring, while DTPA carboxylates are protected by coordination with the lanthanide. Resulting compounds represent cyclic esters and display acylating activity comparable to that of widely used N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters, which is evident from their hydrolysis rates. Indeed, half-hydrolysis times at ambient temperature were about 10 min for Probe 5 and about 40 min for probe 6, while for NHS esters it is 6 min at the same conditions. Both synthesized probes can be coupled to biomolecules with high efficiency at physiological conditions, as exemplified by modification of avidin and BSA. Generally, upon conjugation probe 6 displayed more reproducible strong emission signal, while the signal for probe 5 conjugates was sensitive to slight changes in reaction conditions. Particularly, in some cases less efficient energy transfer from antenna to lanthanide was observed for probe 5 conjugates. Also, the emission maximum for antenna fluorophore in such conjugates displayed detectable red shift. Most likely this was due to competing oxidation of the reactive fluorophore form at the conjugation conditions. Indeed, isomeric enole form of the fluorophore (compound VII of Fig. 2B) is expected to be prone to oxidation, especially in ionized state IX. This was confirmed by studies of model compound, N-7-acetyl derivative of fluorophore VIb (VIIb), whose solution quickly turned dark at the conditions of conjugation reaction due to oxidation. This side reaction can likely be suppressed by addition of oxygen scavengers (e.g. pyrogallol). Remarkably, probe 6 always displayed stable reproducible signal upon conjugation, since the probe does not exist in oxygen-sensitive enolic form.

The suggested protocols for probes 5 and 6 are simple, since they do not include chromatographic purification steps and can be accomplished in 1–2 days. The probes react under exceptionally mild conditions (pH 7.0, 20 °C, 1–2 min), which makes them especially valuable for labeling of sensitive biological molecules.

Stability of the synthesized luminescent chelates under the conditions of denaturing electrophoretic separation allows using the probes in proteomic studies, especially in cases when sensitive detection is required. High detection sensitivity for labeled SDS PAGE separated proteins was demonstrated by using a home-built device for time-resolved gel imaging.

Finally, the developed synthetic protocols may be used to obtain analogous reactive chelates of cs124 antenna fluorophore (containing methyl instead of trifluoromethyl group in position 4 of quinolone ring), which are highly luminescent when complexed with Tb3+ (18, 19).

5. CONCLUSION

We synthesized new amine-reactive luminescent Eu3+ chelates able to couple to proteins at neutral pH at room temperature with high efficiency. The probes can find wide applications in assay development, imaging, and tracing analysis as well as in proteomic and intracellular studies that require high detection sensitivity.

Highlights.

-

●

Amine-reactive luminescent Eu3+ chelates were synthesized using simple no-chromatography procedure.

-

●

he obtained chelates displayed high reactivity coupling to avidin at physiological conditions with high efficiency within a few minutes.

-

●

The probes can find wide applications in assay development, imaging, as well as in proteomic studies that require high detection sensitivity.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by NIH grant RO1 GM-307-17-21 to AM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature cited

- 1.Eliseeva S, Bünzli JC. Lanthanide luminescence for functional materials and biosciences. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:189–227. doi: 10.1039/b905604c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagan AK, Zuchner T. Lanthanide-based time-resolved luminescence immunoassays. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011;400:2847–2864. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunzli JC. Benefiting from the unique properties of lanthanide ions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:53–61. doi: 10.1021/ar0400894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson EF, Pollak A, Diamandis EP. Time-resolved detection of lanthanide luminescence for ultrasensitive bioanalytical assays. J Photochem. Photobiol. B. 1995;27:3–19. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(94)07086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickson EF, Pollak A, Diamandis EP. Ultrasensitive bioanalytical assays using time-resolved fluorescence detection. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995;66:207–235. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00078-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemmila I, Laitala V. Progress in lanthanides as luminescent probes. J. Fluoresc. 2005;15:529–42. doi: 10.1007/s10895-005-2826-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker D. Excitement in f block: structure, dynamics and function of nine-coordinate chiral lanthanide complexes in aqueous media. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004;33:156–165. doi: 10.1039/b311001j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selvin PR. Principles and biophysical applications of lanthanide-based probes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2002;31:275–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.101101.140927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werts MH. Making sense of lanthanide luminescence. Sci. Prog. 2005;88:101–131. doi: 10.3184/003685005783238435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge P, Selvin PR. Thiol-reactive luminescent lanthanide chelates: part 2. Bioconjug Chem. 2003;14:870–876. doi: 10.1021/bc034029e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ge P, Selvin PR. New 9- or 10-dentate luminescent lanthanide chelates. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1105–1111. doi: 10.1021/bc800030z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Selvin PR. Thiol-reactive luminescent chelates of terbium and europium. Bioconjug Chem. 1999;10:311–315. doi: 10.1021/bc980113w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J, Selvin PR. Synthesis of 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl-2-(1H)-quinolinone and its use as an antenna molecule for luminescent europium polyaminocarboxylates chelates. J Photochem Photobiol A. 2000;135:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge P, Selvin PR. Carbostyril derivatives as antenna molecules for luminescent lanthanide chelates. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:1088–1094. doi: 10.1021/bc049915j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selvin PR, Hearst JE. Luminescence energy transfer using a terbium chelate: improvements on fluorescence energy transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10024–10028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heyduk E, Heyduk T. Thiol-reactive, luminescent Europium chelates: luminescence probes for resonance energy transfer distance measurements in biomolecules. Anal Biochem. 1997;248:216–227. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krasnoperov LN, Marras SAE, Kozlov M, Wirpsza L, Mustaev A. Luminescent probes for ultrasensitive detection of nucleic acids. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21:319–327. doi: 10.1021/bc900403n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M, Selvin PR. Luminescent polyaminocarboxylate chelates of Terbium and Europium: The effect of Chelate Structure. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8132–8138. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, Selvin PR. Amine-reactive forms of a luminescent diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid chelate of terbium and europium: attachment to DNA and energy transfer measurements. Bioconjug Chem. 1997;8:127–132. doi: 10.1021/bc960085m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pillai S, Kozlov M, Marras SAE, Krasnoperov L, Mustaev A. New Cross-linking Quinoline and Quinolone Derivatives for Sensitive Fluorescent Labeling. J. Fluorescence. 2012;22:1021–1032. doi: 10.1007/s10895-012-1039-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wirpsza L, Pillai S, Batish M, Marras SAE, Krasnoperov L, Mustaev A. Highly Bright Avidin-based Affinity Probes Carrying Multiple Lanthanide Chelates. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2012;116:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selvin PR, Jancarik J, Min Li M, Hung LW. Crystal Structure and Spectroscopic Characterization of a Luminescent Europium Chelate. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:700–705. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamandis E. Multiple labeling and time-resolvable fluorophores. Clin. Chem. 1991:1486–1491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]