Abstract

Background

During late prenatal and early postnatal life, the reproductive system in males undergoes an extensive series of physiological and morphological changes. Prenatal ethanol exposure has marked effects on the development of the reproductive system, with long-term effects on function in adulthood. The present study tested the hypothesis that prenatal ethanol exposure will delay the onset of spermatogenesis.

Methods

Development of the seminiferous tubules and the onset of spermatogenesis were examined utilizing a rat model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). Male offspring from ad libitum-fed control (C), pair-fed (PF) and ethanol-fed (prenatal alcohol exposure, PAE) dams were terminated on postnatal (PN) days 5, 15, 18, 20, 25, 35, 45 and 55, to investigate morphological changes through morphometric analysis of the testes from early neonatal life through young adulthood.

Results

PAE males had lower relative (adjusted for body weight) testis weights compared to PF and/or C males from PN15 through puberty (PN45). In addition, fewer gonocytes (primordial germ cells) were located on the basal lamina on PN5, while more of those touching the basal lamina were dividing in PAE compared to PF and C males, suggesting delayed cell division and migration processes. As well, the percentage of tubules with open lumena was lower in PAE compared to PF and C males on PN18 and PN20, and PAE males had fewer primary spermatocyte per tubule on PN18 and round spermatids per tubule on PN25 compared to C males. Finally, the percentage of tubules at stages VII and VIII, when mature spermatids move to the apex of the epithelium and are released, was lower in PAE compared to PF and/or C males in young adulthood (PN55).

Conclusions

Maternal ethanol consumption appears to delay both reproductive development and the onset of spermatogenesis in male offspring, with effects persisting at least until young adulthood.

Keywords: Prenatal Ethanol Exposure, Spermatogenesis, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Reproductive Development

INTRODUCTION

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is an umbrella term that refers to the wide range of abnormalities or deficits that can occur in children born to women who drink alcohol during pregnancy (Manning and Eugene Hoyme, 2007; Riley and McGee, 2005). At the most severe end of the spectrum is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which can occur with chronic consumption of high doses of alcohol (Jones and Smith, 1973). The key diagnostic criteria for FAS include growth deficits, central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities, both physical and functional, and a characteristic facial dysmorphology, including small palpebral fissures, flattened philtrum and thin upper lip. Physical, physiological, cognitive, and behavioral abnormalities compromise the individual’s ability to adapt to and function in his/her environment. Alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND) refers to the range of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological abnormalities that can occur in individuals exposed to ethanol at levels lower than those necessary to produce FAS. Day to day function of these individuals is also often severely imparied.

Features similar to those observed in human FASD are observed in rodent models of prenatal ethanol exposure (e.g. retarded pre- and postnatal growth and development, physical malformations, CNS abnormalities, and cognitive and behavioral problems) (Abel and Dintcheff, 1978; Caldwell et al., 2008; Hausknecht et al., 2005; Hellemans et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 2009; Weinberg, 1993). Of particular relevance to the present study, studies utilizing rodent models have shown that prenatal alcohol (ethanol) exposure (PAE) has marked adverse effects on development and activity of the reproductive system, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Ethanol readily crosses the placenta, thus directly affecting developing fetal endocrine and reproductive organs. Both pre- and postnatal testosterone surges are suppressed in PAE fetuses/neonates (McGivern et al., 1993; McGivern et al., 1988; Ward et al., 2003). At birth, PAE pups exhibit decreased brain and plasma testosterone levels (Kakihana et al., 1980), and deficits in testicular steroidogenic enzyme activity (Kelce et al., 1990; Kelce et al., 1989), as well as decreased anogenital distance compared to controls (Udani et al., 1985). The developmental pattern of luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion also is altered in PAE males, which could contribute to later changes in reproductive function (Handa et al., 1985), such as deficits in spermatogenesis and sexual behavior. In adulthood, PAE males have a significantly reduced volume of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (Barron et al., 1988; Rudeen, 1986) and may show decreased testicular weight, reduced weights of prostate and seminal vesicles, decreased serum testosterone and LH levels, and altered neurotransmitter responses to testosterone, suggesting central dysregulation of HPG activity (Handa et al., 1985; Jungkuntz-Burgett et al., 1990; Parker et al., 1984). Altered morphology of the seminiferous tubules has also been reported, eg. absence of reticulin fibers in the peritubular tissue of seminiferous tubules at PN 42 (Fakoya and Caxton-Martins, 2004). On the other hand, some studies have shown no adverse effects of prenatal ethanol on anogenital distance (McGivern et al., 1992; McGivern et al., 1988), higher testis weight indexed to body weight (McGivern et al., 1992) and normal LH and testosterone levels in adulthood (Udani et al., 1985; Ward et al., 1996). Further studies are needed to resolve these discrepancies in the literature. In addition, the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on development of the seminiferous tubules and the onset of spermatogenesis, critical aspects of reproductive development, have not been examined to date.

During postnatal development, seminiferous tubules undergo a series of physiological and morphological changes, including establishment of the blood-testis barrier, formation of tubular lumena, production of seminiferous fluid, and “maturation” of cytoskeletal elements in Sertoli and myoid cells (Malkov et al., 1998; Russell et al., 1989). In the present study, we terminated animals at different developmental stages in order to assess effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on the course of reproductive development. Termination days early in development (PN5, 15, 18, 20 and 25) were chosen based on the ages reported in the literature showing the typical morphological changes described above. At PN5, gonocytes have moved from the center to the periphery of the tubules. The blood-testis barrier typically forms on PN15–16 and lumena are formed by PN18. PN20 and 25 represent pre- and early post-weaning ages. The late developmental termination days (PN35, 45 and 55) were chosen to represent prepubertal, pubertal, and postpubertal (or young adulthood) stages, respectively (Korenbrot et al., 1977; Udani et al., 1985). We measured testis weights, cell (gonocytes [primordial germ cells], spermatocytes, spermatids) counts per seminiferous tubule, location and proliferative status of gonocytes, percentage of tubules with open lumena, and percentage of tubules in stages VII and VIII (when mature spermatids move to the apex of the epithelium and are released). The objective of the present study was to test the hypothesis that prenatal ethanol exposure delays the onset of spermatogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Breeding

Male (275 – 300 g, n=15) and female (230 – 275 g, n=35) Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (St. Constant, PQ, Canada). Rats were group-housed by sex until breeding and maintained on a 12:12 hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 06:00 hr), with controlled temperature (21 – 22 °C), and ad libitum access to standard laboratory chow and water. Animals were bred one to two weeks following arrival. All animal use and care procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the University of British Columbia Animal Care Committee.

Diets and Feeding

On gestation day (GD) 1, females were singly housed and randomly assigned to one of three treatment groups: 1) Ethanol (PAE), liquid ethanol diet (36% ethanol-derived calories) and water, ad libitum, (n=12); 2) Pair-fed (PF), liquid control diet, with maltose-dextrin isocalorically substituted for ethanol, and intake matched to the amount consumed by an PAE partner (g/kg body weight/gestation d), and water ad libitum; (n=12); 3) Control (C): standard lab chow and water, ad libitum, (n=11). PAE females were gradually introduced to the ethanol diet by providing 1/3 ethanol : 2/3 control diet on GD1, 2/3 ethanol : 1/3 control diet on GD2, and full ethanol diet on GD3. The liquid diets were prepared by Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA, and formulated in our laboratory to provide adequate nutrition to pregnant rats regardless of ethanol intake. PAE and PF dams were provided with fresh liquid diet daily within 1.5 hr prior of lights off, and the previous night’s bottle was weighed to determine the amount consumed. Experimental diets were continued through GD21, and beginning on GD22 animals were provided ad libitum access to standard laboratory chow and water, which they received throughout lactation. Pregnant dams were handled only on GD1, GD7, GD14 and GD21 for cage changing and weighing. On PN1, pups were weighed and litters were randomly culled to 10 (5 males and 5 females when possible). If necessary, pups from the same prenatal treatment group born on the same day were fostered into a litter to maintain the litter size. Animals remained with their natural mothers until weaning. Dams were weighed on lactation day (LD) 1 and 8. On PN 22, pups were weaned, and group-housed by litter and sex.

Serum testosterone levels

Male offspring from C, PF and PAE dams were weighed and terminated by decapitation on PN5, 15, 18, 20, 25, 35, 45 and 55 (n=6 for each prenatal treatment group and postnatal day). Trunk blood was collected at termination. Samples were centrifuged at 2200X g for 10 min at 0 °C. Serum was transferred into 600 µl Eppendorf tubes and stored at − 80 °C until assayed.

Testosterone levels were measured using an adaptation of the testosterone RIA kit of MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH) with[125I] testosterone as the tracer and all reagent volumes halved. The testosterone antibody (solid phase) cross-reacts slightly with 5α-DHT (3.4 %), 5α-androstane-3β, 17β-diol (2.2 %) and 11-oxotestosterone (2 %) but does not cross-react with progesterone, estrogen, or the glucocorticoids (all < 0.01 %). An aliquot of 25 µl plasma was used to determine testosterone concentrations. The minimum detectable testosterone concentration was 0.1 ng/ml and the intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 4.6 % and 7.5 % respectively.

Morphometric Analysis

Right testes were removed and weighed at the time of termination, then fixed, processed and embedded in plastic.

The capsule of each testis was gently punctured (taking care not to apply pressure to the organ or tubules) in 3 or 4 areas with a 26G syringe needle and testes were immersion fixed in 1.5% paraformaldehyde and 1.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) for 1 hr at room temperature. Each testis was then cut into small blocks (1 mm3) with two razor blades. The blocks were fixed by immersion for another 1.5 hr. Tissue was washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) and left overnight.

The next day, all material was washed twice with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.3) and post-fixed on ice for 1 hour in buffered 1% OsO4. Tissue was washed with distilled water and then treated for 1 hour with 1% aqueous uranyl acetate. Tissue blocks were sectioned (1 µm thick), stained with toluidine blue, and the structure of seminiferous tubules was evaluated and photographed using a Zeiss Axiophot microscope. When applicable, samples were processed further using standard techniques for electron microscopy. Staining was evaluated and photographed on a Philips 300 electron microscope operated at 60 kV.

All morphometric measurements were performed with observers blind to prenatal treatment conditions.

Statistical Analyses

For analysis of body and testis weights, and serum testosterone levels, early (PN5–25) and late (PN35–55) developmental stages were analyzed separately using 2-way ANOVAs for the factors of prenatal group (C, PF and PAE) and postnatal day (5, 15, 18, 20, 25) or (PN35, 45, and 55). This was necessary because body weights ranged from 10 g at PN5 to over 300 g at PN55, and in parallel, testis weight and testosterone levels varied greatly with age. Therefore, possible differences among groups would be completely overshadowed by sheer differences in weight and hormone levels if a single analyses with all ages included were to be performed. Furthermore, for cell (spermatocytes, spermatids) counts per tubule across groups, we found that variance (standard errors) was proportional to the means (i.e., as means increased, SEMs increased proportionately), therefore, data were subjected to a logarithmic transformation and analyzed using one-way ANOVAs. Data for location and proliferative status of gonocytes, the percentage of tubules with open lumena, and the percentage of tubules in stages VII and VIII were analyzed with Chi-square tests. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05, and p values of 0.05 – 0.10 were identified as trends.

RESULTS

Maternal Body Weight, Offspring Body and Relative Testis Weight

Separate analyses of maternal body weights during gestation (GD1, 7, 14, 21) and following parturition (LD1 and 8) indicate significant main effects of group (F(2, 66) = 18.03, p < 0.001 and F(2, 20) = 5.93, p < 0.01, respectively) and group X day interactions (F(6, 66) = 17.44, p < 0.001 and F(1, 20) = 46.82, p < 0.001, respectively) during both gestation and lactation. PAE and PF dams have lower body weights than C dams from GD7 to 21. Immediately following parturition (LD1), body weights in PAE and PF dams remain lower than those of C dams, but catch-up weight gain occurs, and groups are no longer different by LD8.

Analysis of male offspring body weights during early developmental stages (PN5–25) indicates a trend for a prenatal group effect (F(2, 76) = 2.42, p = 0.096) and a significant main effect of postnatal day (F(4, 76) = 556.77, p < 0.001). Animals from all prenatal groups gained weight over days, but overall, PAE males weigh less than C males (PAE < C, p < 0.05). Inspection of Table 1 suggests that this overall effect is driven primarily by a difference in weights on PN25. During late developmental stages (PN35–55), we found significant main effect of prenatal group (F(2, 45) = 4.21, p < 0.05) and postnatal day (F(2, 45) = 762.53, p < 0.001), and a trend for a group X day interaction (F(4, 45) = 2.20, p = 0.08). While males do not differ significantly in weight on PN35–45, on PN55, both PAE and PF males weigh less than C males (PAE = PF < C, p < 0.01) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body Weights (BW) and Relative Testis Weights (TW/BW ratio) (Mean±SEM)

| BW (g) | TW/BW (mg/g) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | C | PF | PAE | C | PF | PAE |

| PN5 | 10.8±0.4 | 10.1±0.2 | 10.2±0.4 | |||

| PN15 | 35.6±0.8 | 35.2±0.8 | 35.8±1.5 | 1.3±0.1 | 1.2±0.2 | 1.2±0.1 |

| PN18 | 42.2±1.2 | 42.1±2.0 | 41.6±2.6 | 1.8±0.1 | 1.9±0.3 | 1.5±0.1 |

| PN20 | 49.0±1.1 | 46.9±1.4 | 47.2±2.1 | 2.2±0.1 | 2.0±0.1 | 1.8±0.1 |

| PN25 | 77.5±2.7 | 75.6±1.9 | 68.9±2.7 | 2.9±0.1 | 2.7±0.2 | 2.5±0.1 |

| PN35 | 155.5±4.0 | 152.9±3.2 | 156.9±3.3 | 3.8±0.1 | 4.0±0.1 | 3.5±0.1^ |

| PN45 | 240.7±4.5 | 231.0±6.8 | 240.5±5.5 | 4.6±0.1 | 4.7±0.1 | 4.2±0.1^ |

| PN55 | 336.8±3.8 | 312.7±6.3# | 312.4±7.6# | 4.1±0.2 | 4.2±0.3 | 4.5±0.2 |

BW: For the early developmental period (PN5–25): Overall (collapsed across days), PAE < PF, p = 0.09; PAE < C, p < 0.05; For the late developmental period (PN35–55): #PAE = PF < C, p < 0.01 on PN55.

TW/BW ratio: For the early developmental period (PN15–25): Overall, PAE < PF = C, p < 0.01; For the late developmental period (PN35–55), ^PAE < PF, p < 0.05 on PN35 and 45; PAE < C, p = 0.08 on PN45.

Analysis of relative (adjusted for body weight) testis weights indicate significant main effects of prenatal group (F(2, 49) = 6.05, p < 0.005) and postnatal day (F(3, 49) = 58.21, p < 0.001) during early developmental stages, Overall, all animals have increasing testis:body weight ratios, but relative testis weights are lower in PAE compared to PF and C males during PN15–25. During later developmental stages, analysis shows significant main effects of postnatal day (F(2, 44) = 17.04, p < 0.001) and a trend for a group × day interaction (F(4, 44) = 2.34, p = 0.07). PAE males have lower relative testis weights than PF males on PN 35 and 45 (PAE < PF, p < 0.05), and show a trend for lower relative weights than C males on PN45 (PAE < C, p = 0.08) (Table 1).

Serum testosterone levels

There were no significant effects of group (p = 0.12) or day (p = 0.16) for testosterone levels in the early developmental stage. Mean testosterone levels ranged from 0.01–0.26 ng/ml. For the late developmental stage, once again, there were no differences among prenatal groups, p = 0.79, but there was a significant main effect of day, F(2,44) = 19.79, p < 0.001. Testosterone levels increased from PN 35–55, with means of 0.20 ng/ml at PN35, 0.91 ng/ml at PN45 and 1.40 ng/ml at PN55.

Morphology of Seminiferous Tubule during Development

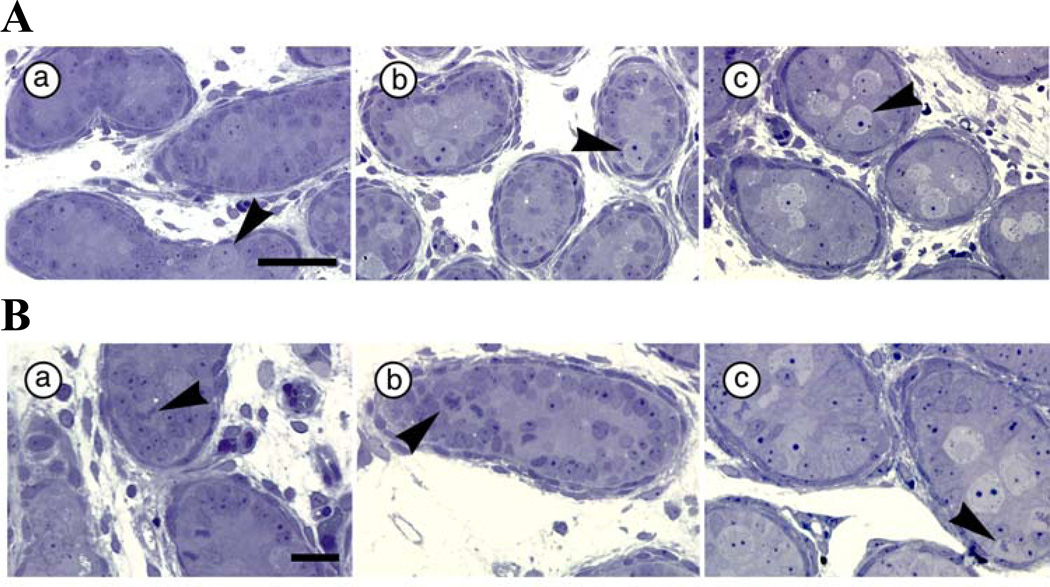

Chi-square analysis of seminiferous cords on PN5 indicates that significantly fewer gonocytes touch the basal lamina in PAE (10.2%) compared to PF (22.7%) and C (19.4%) males (Figure 1A) (χ2 [2, N = 3021] = 60.13, p < 0.001), and that there are fewer dividing gonocytes in PAE (22.9%) and PF (21.1%) compared to C (29.0%) males (χ2 [2, N = 3021] = 18.63, p < 0.001). However, more of the gonocytes that touch the basal lamina are dividing in PAE (74.5%) compared to PF (38.1%) and C (50.0%) males (Figure 1B) (χ2 [2, N = 524] = 38.41, p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

A. Gonocyte location in C (a), PF (b) and PAE (c) males at PN5 (N=6 for each prenatal treatment group). Scale bar = 50 µm Arrowhead points to gonocytes (touching the basal lamina in PF and C groups); B. Gonocyte proliferation status in C (a), PF (b) and PAE (c) males at PN5 (N=6 for each prenatal treatment group). Scale bar = 20 µm. Arrowhead points to dividing gonocytes (attached to the basal lamina in PAE, and located in the center in PF and C, males).

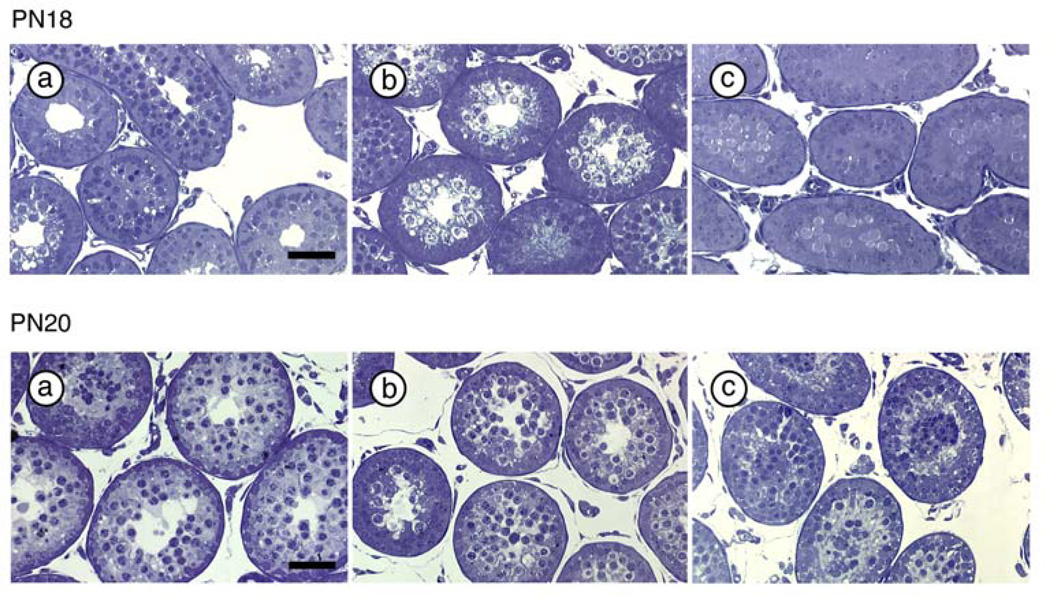

On PN18 and PN20, the percentage of tubules with open lumena was lower in PAE (7.5% and 16.0%, respectively) compared to PF (16.7% and 34.5%) and C (17.9% and 31.3%) males (Figure 2, Table 2) (χ2 [2, N = 982] = 20.43, p < 0.001 on PN18; χ2 [2, N = 590] = 16.94, p < 0.001 on PN20).

Figure 2.

Seminiferous tubules with open lumena in C (a), PF (b) and PAE (c) males on PN18 (upper panel) and PN20 (lower panel) (N=6 for each prenatal treatment group at each age). Scale bar = 100 µm.

Table 2.

Developmental markers of seminiferous tubules around weaning (Mean or Mean ±SEM)

| C | PF | PAE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open lumena (%) | |||

| (PN18) | 17.9 | 16.7 | 7.5* |

| Open lumena (%) | |||

| (PN20) | 31.3 | 34.5 | 16.0* |

| Spermatocytes per tubule | |||

| (PN18) | 21.0±8.2 | 9.6±2.5 | 5.0±1.0# |

| Round spermatids per tubule | |||

| (PN25) | 3.2±0.7 | 2.9±0.4 | 1.9±0.3 |

PAE < PF = C, p < 0.001;

PAE < C, p < 0.05; PAE < C on PN25, p = 0.07

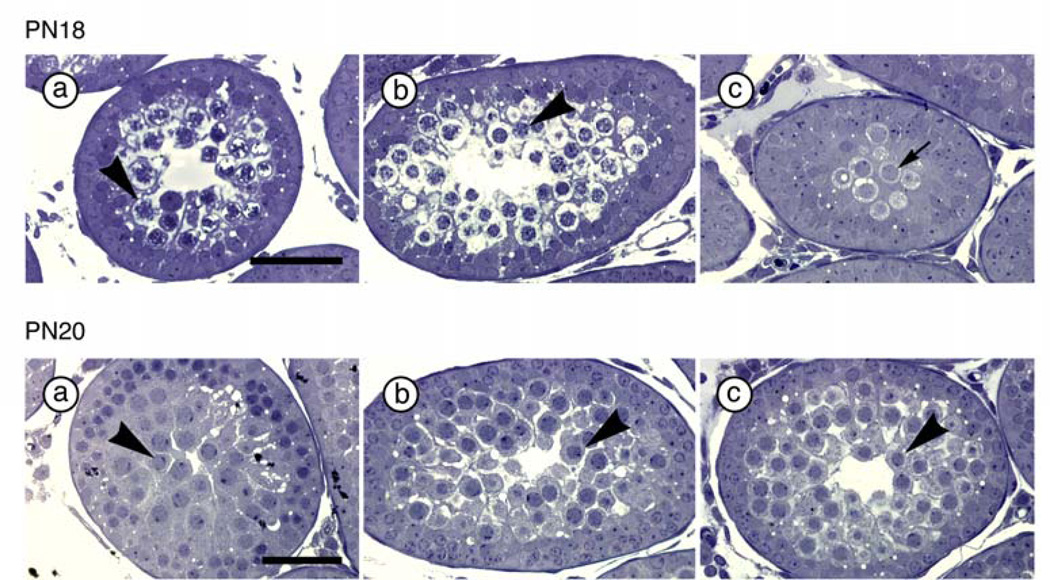

ANOVAs on logarithmic transformed values for numbers of spermatocytes per tubule on PN18, (F(2, 11) = 4.02, p < 0.05), and numbers of round spermatids per tubule on PN25, (F(2, 12) = 2.22, p = 0.15), indicate that PAE males have fewer primary spermatocytes per tubule (p < 0.05) and show only a marginal reduction in number of round spermatids per tubule (p = 0.07) compared to C males (Figure 3, Table 2).

Figure 3.

Primary spermatocytes on PN18 (upper panel) and round spermatids on PN25 (lower panel) in C (a), PF (b) and PAE (c) males (N=6 for each prenatal treatment group at each age). Scale bar = 50 µm. Upper panel: Arrow points to spermatogonia (in PAE males) that do not have condensed chromatin. Arrowhead points to primary spermatocytes (in PF and C males) that have condensed chromatin. Lower panel: Arrowhead points to round spermatids.

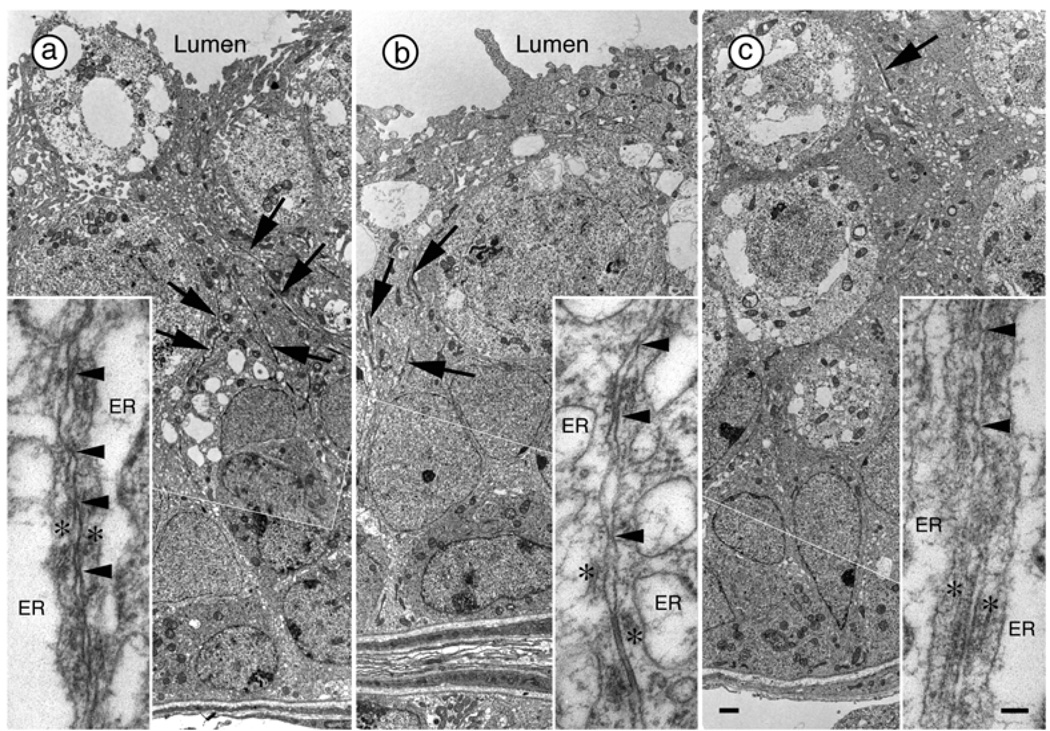

Electron Microscopy (EM) analysis of seminiferous tubules reveals that junction complexes in the testes of PAE males on PN18 were situated near the center of the solid tubules and were short (Figure 4). By contrast, junction complexes in males from PF and C groups were numerous and formed long linear tracts near the middle of the developing epithelium, which in these animals surrounds a lumen (Figure 4). Moreover, there was a lower percentage of tubules in stages VII (PAE < PF, p < 0.05; PAE < C, p = 0.057) and VIII (PAE < C, p < 0.05) in PAE compared to PF and/or C males on PN55 (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Junction complexes between Sertoli cells in the testes of C (a), PF (b) and PAE (c) males at PN18. Each of these low magnification images is a collage of two images joined at the thin white line. Junction complexes are identified by the presence of ectoplasmic specializations consisting of a layer of actin filaments (asterisks in insets) sandwiched between the plasma membrane and cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum (ER, in insets). Adhesion junctions often contain tight junctions identified by membrane “kisses” (arrowheads in insets) and gap junctions. When present, Junction complexes in the testes of PAE rats are situated near the center of the solid tubules and are short [arrow in (c)]. Junction complexes in C (a) and PF (b) males are numerous and form long linear tracts (arrows) near the middle of the developing epithelium, which now surrounds a lumen. Although membranes ‘kisses’ are occasionally observed within the Junction complexes in PAE rats, numerous tight junctions are obvious in PF and C rats. Scale bar = 1.0 µm. Scale bar in inset = 0.1 µm.

Table 3.

Percentage of seminiferous tubules in Stages VII and/or VIII (Mean ± SEM)

| PN45 | PN55 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | PF | PAE | C | PF | PAE | |

| Stage VII | 16.8±5.7 | 23.2±4.6 | 17.1±8.0 | 23.3±2.1 | 25.1±4.4 | 13.9±1.7* |

| Stage VIII | 7.2±3.6 | 7.2±3.0 | 3.5±1.7 | 9.1±2.7 | 3.1±1.6 | 3.5±2.2 |

| Stage VII & VIII | 24.0±6.5 | 30.4±4.2 | 20.6±7.7 | 32.4±3.1 | 28.2±5.7 | 17.3±0.8# |

StageVII, PAE < PF, p < 0.05; PAE < C, p = 0.057;

StageVII&VIII, PAE < C, p < 0.05

DISCUSSION

In this study we show that prenatal ethanol exposure delays multiple aspects of reproductive development in male offspring, and ultimately, the onset of spermatogenesis.

Ethanol intake of the pregnant females was at amounts shown previously to result in peak blood ethanol levels of 150–190 mg/dl (Lan et al., 2006), which is approximately twice the drunk driving standard (80–100 mg/dl) in many jurisdictions. Consistent with previous studies (Abel, 1978; Taylor et al., 1981; Tritt et al., 1993; Weinberg, 1985; Weinberg et al., 1995), females consuming ethanol and their pair-fed control counterparts both had lower body weights throughout gestation and immediately following parturition (LD1) compared to ad libitum-fed control dams, but there was fairly rapid catch-up weight gain and these differences no longer exist by the end of the first week of lactation. These reductions in body weight are the result of reduced food intake in ethanol-consuming dams (below what they would consume if given the same diet without ethanol), and the fact that PF dams receive a reduced ration matched to that of the ethanol-consuming dams. Ethanol-derived calories are often referred to as “empty calories” in that they replace the calories supplied by food, which has associated nutrients. Thus, consumption of ethanol-containing diets results in suboptimal nutrition. Pair-feeding is typically employed as a standard control for the nutritional effects of ethanol intake. However, pair-feeding only controls for the reduced intake of the ethanol-consuming dam, and can never control for ethanol-induced effects on nutrient absorption and utilization, or other effects of ethanol on the gastrointestinal system, physiological function, and metabolism. Furthermore, because PF dams receive a reduced ration of food they are hungry, and typically consume their entire ration within a few hours of feeding, remaining deprived until feeding the next day. PF dams therefore experience mild stress due to the hunger that accompanies a restricted ration, and the pair-feeding paradigm likely comprises a mild prenatal stress that is superimposed on the nutritional aspect of reduced food intake. Pair-feeding is thus a treatment in itself (Gallo and Weinberg, 1981; Weinberg, 1984), and the finding that pair-feeding has effects on body weights and other developmental outcomes is not entirely surprising.

Offspring body weights and testis weights were also adversely affected by prenatal exposure to ethanol, both in early and late developmental stages. Male offspring in all prenatal groups gained weight over the course of development, and there were no differences among groups in the preweaning period. Shortly after weaning (PN25), however, PAE males showed slower weight gain and had significantly lower body weights than PF and C males. Interestingly, following some catch-up growth during early adolescence, both PAE and PF weighed less than C males in young adulthood. In addition, relative (corrected for body weight) testis weights were lower in PAE compared to PF and/or C males from PN15 through puberty (PN45).

At birth, the seminiferous cords contain only two cell types, Sertoli cells and primordial germ cells, or gonocytes. Movement of gonocytes from the center to the periphery of the seminiferous cord, attachment to the basal lamina, and resumption of mitosis by these previously quiescent cells, are likely to be critically important in establishing spermatogenesis in neonatal rats (McGuinness and Orth, 1992). During the first week of postnatal life, gonocytes first make contact with the basal lamina on PN4, but re-initiate cell division one day earlier. In our study, examination of the seminiferous cords on PN5 indicated that significantly fewer gonocytes touched the basal lamina in PAE compared to PF and C males, and that there were fewer dividing gonocytes present in PAE and PF compared to C males. However, more of the gonocytes that touched the basal lamina were dividing in PAE compared to PF and C males, suggesting delayed cell division and migration processes in offspring exposed to ethanol prenatally. However, we make this conclusion with caution, as we cannot conclusively rule out the possibility that the changes in gonocytes of PAE offspring were due to increased apoptosis (Li and Kim, 2003). Further studies are needed to determine the mechanisms underlying the changes we observed.

Another developmental marker for reproductive maturation is the formation of lumena in the solid seminiferous tubule. It is reported that the blood-testis barrier forms in the majority of tubules on PN15 and 16, and that lumena within the tubules are typically evident by PN18 (Russell et al., 1989). We found, as expected, that none of the tubules had lumena on PN5 or 15. Importantly, the percentage of tubules with open lumena was lower in PAE compared to PF and C males on PN18 and PN20, supporting the suggestion that prenatal exposure to alcohol delays development of the reproductive system.

The blood-testis barrier (also known as the seminiferous epithelial barrier), is formed by tight junctions within junction complexes located in the basal third of the seminiferous epithelium (Russell et al., 1989) between neighboring Sertoli cells. In the present study, EM analysis shows that junction complexes in the testes of PAE males on PN18 are situated near the center of the solid tubules and are short. By contrast, junction complexes in animals from the PF and C groups are numerous and form long linear tracts near the middle of the developing epithelium, which in these animals surrounds a lumen. Furthermore, although membrane ‘kisses’ are occasionally observed within the junction complexes in the PAE group, numerous tight junctions are obvious in the PF and C groups. These qualitative observations on junctions are consistent with quantitative differences noted in the development of lumena and indicate that there is a delay in seminiferous epithelial maturation in PAE males.

During the prepubertal period, the seminiferous cords form seminiferous tubules, which become populated with spermatogonia. Development does not proceed beyond this phase until puberty, when the production of mature spermatozoa is initiated. When immature spermatogonia undergo mitosis, some daughter cells lose contact with the basement membrane of the seminiferous tubule, undergo specific developmental changes, and differentiate into primary spermatocytes, which enter meiosis. These cells are characterized by having copious cytoplasm and large nuclei containing coarse clumps or thin threads of chromatin. The smaller secondary spermatocytes rapidly undergo the second meiotic division and are therefore much less commonly seen. The gametes are produced after the second meiosis and are called spermatids (Malkov et al., 1998). As yet another marker of delayed maturation, we find that numbers of primary spermatocytes per tubule on PN18 and numbers of round spermatids per tubule on PN25 are lower in PAE compared to C males.

In rats, the spermatogenic cells in a cross section of a seminiferous tubule can be categorized into 14 different cellular associations (Franca et al., 1998). Each cellular association defines a stage of spermatogenesis. Stages may be recognized based on appearance of the acrosome, meiotic divisions, the shape of the spermatid nucleus, or release of the spermatozoa (Ulvik et al., 1982). Mature spermatids occur at the apex of the epithelium at stages VII and VIII, and are released from the epithelium at the end of stage VIII. The next generation of elongate spermatids all orient towards the tubule wall in Stage VIII. In the present study, we found a lower percentage of tubules in stages VII and VIII in PAE compared to PF and/or C males on PN55, which is consistent with a delay in the onset of spermatogenesis in PAE males.

As noted, several previous studies have examined long-term effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on aspects of testis and reproductive development. PAE was shown to reduce testis, prostate, and seminal vesicle weights, and to decrease serum levels of testosterone and LH (Handa et al., 1985; Parker et al., 1984). As well, pulse amplitude and frequency of LH secretion (Handa et al., 1985), and an altered hypothalamic catecholaminergic neuron response to testosterone (Jungkuntz-Burgett et al., 1990) have been reported. In addition, a significantly reduced volume of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (Barron et al., 1988; Rudeen, 1986), and feminization of both sexual and non-sexual sexually dimorphic behaviors (McGivern et al., 1984; McGivern et al., 1987; Parker et al., 1984; Udani et al., 1985) have been reported. Our data support and extend these previous findings, demonstrating adverse effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on multiple markers of reproductive development from neonatal life through young adulthood.

One of the only previous studies to examine testis development (Fakoya and Caxton-Martins, 2004) utilized Wistar rats and administered ethanol by intragastric intubation at a dose of 5.8 g/kg/day, from gestation day 9–12. Examination of offspring at puberty (PN42) revealed that this ethanol exposure regimen induced persistent growth retardation and a 13% reduction in relative testis weight. In addition, the data indicated reductions in the cross-sectional area of the tubules by 18% and of the germinal epithelium thickness by 21%, as well as an inhibition of spermatogenesis. Of note, while blood alcohol levels (BALs) are not reported by Fakoya et al (Fakoya and Caxton-Martins, 2004), it is likely that their BALs were significantly higher than ours. Previous studies utilizing intragastric intubation of ethanol at doses of 4.5 – 6.0 mg/dl report BALs ranging from 200–500 mg/dl. For example, Marino et al. (Marino et al., 2002) and Lugo et al (Lugo et al., 2006) intubated a dose of 4.5 g/kg once daily throughout gestation, and found peak BALs of 300–310 mg/dl at 2 hr post-intubation. Du & Hamre intubated doses of 3.0, 4.5 or 5.5 g/kg and found BALs averaging 250, 420, and 550 mg/dl, respectively, at 2 hr post intubation (Du and Hamre, 2001). Similarly, Maier & West gave intragastric alcohol doses of 2.5, 4.5 or 6.5 g/kg daily throughout gestation, and found mean peak BALs of 136, 290, and 422 mg/dl (Maier and West, 2001). These latter two studies reported dose-dependent increases in cell death in various different brain regions. These differences in timing and dose of ethanol administration likely account for the more severe outcomes in the Fakoya et al study compared to ours.

In summary, we are the first group to explore an extensive developmental time course of prenatal ethanol effects on testicular development and onset of spermatogenesis in Sprague-Dawley rats under conditions of moderate to moderately high levels of ethanol exposure (BALs approximately 150 mg/dl). Our data provide an important extension of previous studies on the male reproductive system by demonstrating a developmental time course of adverse effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on multiple markers of reproductive development from neonatal life through young adulthood. Effects on body weight, relative testis weight, gonocyte location and proliferation, the percentage of tubules with open lumena, development of junction complexes, number of primary spermatocytes and round spermatids in seminiferous tubules in the late preweaning period, as well as the percentage of tubules in stages VII and VIII support our hypothesis that prenatal ethanol exposure delays onset of spermatogenesis in male rats. Moreover, we show that these marked adverse effects of in utero ethanol exposure on reproductive development persist beyond puberty and into young adulthood. Importantly, our finding that testosterone levels did not differ among prenatal groups suggests that the effects of ethanol were direct and not due to indirect effects of altered testosterone levels.

Alterations such as those observed in the present study could underlie changes in reproductive function or other adverse effects of prenatal ethanol exposure that have been reported in the literature, and thus have important implications. For example, cryptorchidism (undescended testis), one of the most common abnormalities in newborn boys, has been reported to be associated with an adverse intrauterine environment (Virtanen and Toppari, 2008). However, a link between maternal alcohol consumption and increased risk of cryptorchidism remains controversial (Damgaard et al., 2007; Jensen et al., 2007; Strandberg-Larsen et al., 2009). Damgarrd and coworkers (2007) conducted a follow-up study on 2496 subjects with assessment of cryptorchidism at birth and at 3 months of age. They reported an association between average maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and transient cryptorchidism. Jensen et al (2007) examined older cohorts, assessing the association between persisting cryptorchidism and alcohol exposure at levels higher than those that reported in the Damgarrd study. Strandberg-Larsen et al. studied a larger cohort (n=41,268) including both transient and persisting cryptorchidism cases. Both of the latter studies failed to corroborate an increased risk of cryptorchidism with weekly alcohol consumption. It is possible that the controversy in the data is due, at least partly, to differential effects of alcohol on transient or persisting cryptorchidism. Alterntively, the frequency and timing of alcohol exposure in some studies may not have fallen into the window for programming of male reproductive function.

In this study we provide evidence that maternal ethanol consumption has a direct adverse effect on testis development in an animal model of FASD. Our results provide insight into mechanisms underlying ethanol’s actions, and support a possible role for ethanol exposure in clinical conditions involving reproductive alterations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Paxton Bach, Stephanie Westendorp, Devon O’Rourke, Linda Ellis and Wayne Yu for their expert technical assistance on the experiments.

This research was supported by NIH/NIAAA R37 AA007789 to JW, NSERC RGPIN 155397-08 to AWV, and NSERC CGS to NL.

REFERENCES

- Abel EL. Effects of ethanol on pregnant rats and their offspring. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1978;57:5–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00426950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel EL, Dintcheff BA. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on growth and development in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;207:916–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron S, Gagnon WA, Mattson SN, Kotch LE, Meyer LS, Riley EP. The effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on odor associative learning in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1988;10:333–339. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(88)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell KK, Sheema S, Paz RD, Samudio-Ruiz SL, Laughlin MH, Spence NE, Roehlk MJ, Alcon SN, Allan AM. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder-associated depression: evidence for reductions in the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in a mouse model. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:614–624. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damgaard IN, Jensen TK, Petersen JH, Skakkebaek NE, Toppari J, Main KM. Cryptorchidism and maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:272–277. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Hamre KM. Increased cell death in the developing vestibulocochlear ganglion complex of the mouse after prenatal ethanol exposure. Teratology. 2001;64:301–310. doi: 10.1002/tera.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakoya FA, Caxton-Martins EA. Morphological alterations in the seminiferous tubules of adult Wistar rats: the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2004;63:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franca LR, Ogawa T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL, Russell LD. Germ cell genotype controls cell cycle during spermatogenesis in the rat. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:1371–1377. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.6.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo PV, Weinberg J. Corticosterone rhythmicity in the rat: interactive effects of dietary restriction and schedule of feeding. J Nutr. 1981;111:208–218. doi: 10.1093/jn/111.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa RJ, McGivern RF, Noble ES, Gorski RA. Exposure to alcohol in utero alters the adult patterns of luteinizing hormone secretion in male and female rats. Life Sci. 1985;37:1683–1690. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausknecht KA, Acheson A, Farrar AM, Kieres AK, Shen RY, Richards JB, Sabol KE. Prenatal alcohol exposure causes attention deficits in male rats. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:302–310. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans KG, Verma P, Yoon E, Yu W, Weinberg J. Prenatal alcohol exposure increases vulnerability to stress and anxiety-like disorders in adulthood. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1144:154–175. doi: 10.1196/annals.1418.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MS, Bonde JP, Olsen J. Prenatal alcohol exposure and cryptorchidism. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:1681–1685. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Smith DW. Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet. 1973;302:999–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungkuntz-Burgett L, Paredez S, Rudeen PK. Reduced sensitivity of hypothalamic-preoptic area norepinephrine and dopamine to testosterone feedback in adult fetal ethanol-exposed male rats. Alcohol. 1990;7:513–516. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(90)90041-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakihana R, Butte JC, Moore JA. Endocrine effects of meternal alcoholization: plasma and brain testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, estradiol, and corticosterone. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1980;4:57–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1980.tb04792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelce WR, Ganjam VK, Rudeen PK. Effects of fetal alcohol exposure on brain 5 alpha-reductase/aromatase activity. J Steroid Biochem. 1990;35:103–106. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(90)90152-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelce WR, Rudeen PK, Ganjam VK. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters steroidogenic enzyme activity in newborn rat testes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1989;13:617–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SJ, Goodlett CR, Hannigan JH. Animal models of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: impact of the social environment. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:200–208. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenbrot CC, Huhtaniemi IT, Weiner RI. Preputial separation as an external sign of pubertal development in the male rat. Biol Reprod. 1977;17:298–303. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod17.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan N, Yamashita F, Halpert AG, Ellis L, Yu WK, Viau V, Weinberg J. Prenatal ethanol exposure alters the effects of gonadectomy on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in male rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18:672–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Kim KH. Effects of ethanol on embryonic and neonatal rat testes in organ cultures. J Androl. 2003;24:653–660. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo JN, Jr, Marino MD, Gass JT, Wilson MA, Kelly SJ. Ethanol exposure during development reduces resident aggression and testosterone in rats. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SE, West JR. Drinking patterns and alcohol-related birth defects. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:168–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkov M, Fisher Y, Don J. Developmental schedule of the postnatal rat testis determined by flow cytometry. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:84–92. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning MA, Eugene Hoyme H. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a practical clinical approach to diagnosis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino MD, Cronise K, Lugo JN, Jr, Kelly SJ. Ultrasonic vocalizations and maternal-infant interactions in a rat model of fetal alcohol syndrome. Dev Psychobiol. 2002;41:341–351. doi: 10.1002/dev.10077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Clancy AN, Hill MA, Noble EP. Prenatal alcohol exposure alters adult expression of sexually dimorphic behavior in the rat. Science. 1984;224:896–898. doi: 10.1126/science.6719121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Handa RJ, Redei E. Decreased postnatal testosterone surge in male rats exposed to ethanol during the last week of gestation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:1215–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Holcomb C, Poland RE. Effects of prenatal testosterone propionate treatment on saccharin preference of adult rats exposed to ethanol in utero. Physiol Behav. 1987;39:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Raum WJ, Handa RJ, Sokol RZ. Comparison of two weeks versus one week of prenatal ethanol exposure in the rat on gonadal organ weights, sperm count, and onset of puberty. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1992;14:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(92)90042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGivern RF, Raum WJ, Salido E, Redei E. Lack of prenatal testosterone surge in fetal rats exposed to alcohol: alterations in testicular morphology and physiology. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1988;12:243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness MP, Orth JM. Reinitiation of gonocyte mitosis and movement of gonocytes to the basement membrane in testes of newborn rats in vivo and in vitro. Anat Rec. 1992;233(4):527–537. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092330406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker S, Udani M, Gavaler JS, Van Thiel DH. Adverse effects of ethanol upon the adult sexual behavior of male rats exposed in utero. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1984;6:289–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley EP, McGee CL. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: an overview with emphasis on changes in brain and behavior. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:357–365. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudeen PK. Reduction of the volume of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area by in utero ethanol exposure in male rats. Neurosci Lett. 1986;72:363–368. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90542-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell LD, Bartke A, Goh JC. Postnatal development of the Sertoli cell barrier, tubular lumen, and cytoskeleton of Sertoli and myoid cells in the rat, their relationship to tubular fluid secretion and flow. Am J Anat. 1989;184:179–189. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001840302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandberg-Larsen K, Jensen MS, Ramlau-Hansen CH, Gronbaek M, Olsen J. Alcohol binge drinking during pregnancy and cryptorchidism. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:3211–3219. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AN, Branch BJ, Liu SH, Wiechmann AF, Hill MA, Kokka N. Fetal exposure to ethanol enhances pituitary-adrenal and temperature responses to ethanol in adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1981;5:237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1981.tb04895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritt SH, Tio DL, Brammer GL, Taylor AN. Adrenalectomy but not adrenal demedullation during pregnancy prevents the growth-retarding effects of fetal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:1281–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udani M, Parker S, Gavaler J, Van Thiel DH. Effects of in utero exposure to alcohol upon male rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1985;9:355–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1985.tb05559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulvik NM, Dahl E, Hars R. Classification of plastic-embedded rat seminiferous epithelium prior to electron microscopy. Int J Androl. 1982;5:27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1982.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen HE, Toppari J. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of cryptorchidism. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:49–58. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward IL, Ward OB, Affuso JD, Long WD, 3rd, French JA, Hendricks SE. Fetal testosterone surge: specific modulations induced in male rats by maternal stress and/or alcohol consumption. Horm Behav. 2003;43:531–539. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward IL, Ward OB, French JA, Hendricks SE, Mehan D, Winn RJ. Prenatal alcohol and stress interact to attenuate ejaculatory behavior, but not serum testosterone or LH in adult male rats. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:1469–1477. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.6.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. Nutritional issues in perinatal alcohol exposure. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1984;6:261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. Effects of ethanol and maternal nutritional status on fetal development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1985;9:49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1985.tb05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J. Neuroendocrine effects of prenatal alcohol exposure. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;697:86–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J, Kim CK, Yu W. Early handling can attenuate adverse effects of fetal ethanol exposure. Alcohol. 1995;12:317–327. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)00005-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]