Abstract

Deregulation of microRNAs (miRNAs) can drive oncogenesis, tumor progression and metastasis by acting cell-autonomously in cancer cells. However, solid tumors are also infiltrated by large amounts of non-neoplastic stromal cells, including macrophages, which express several active miRNAs. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) enhance angiogenic, immunosuppressive, invasive and metastatic programming of neoplastic tissue and reduce host survival. Here, we review the role of miRNAs (including miR-155, miR-146 and miR-511) in the control of macrophage production and activation, and examine whether reprogramming miRNA activity in TAMs and/or their precursors might be effective for controlling tumor progression.

Keywords: microRNA, inflammation, monocyte, tumor-associated macrophage, cancer

miRNAs in inflammation and cancer

miRNAs are non-coding RNAs that induce gene silencing by modulating gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. The miRNA processing machinery is expressed in most eukaryotic cells, ranging from plants to vertebrates, thereby indicating that miRNA regulation of gene expression is a highly conserved and widespread phenomenon. Indeed, miRNAs participate in virtually all biological processes, most notably cell proliferation, differentiation and metabolism (see also Box 1). Further, it is increasingly clear that many miRNAs display tissue or cell-type specific expression patterns and can be deregulated in pathological conditions, including cancer [1].

Box 1. miRNAs: critical modulators of gene expression?

Immature miRNAs are transcribed from the nucleus as long precursors (pre-miRNAs), which are processed by nuclear and cytosolic enzymes to generate short (21–24 nucleotide long) active miRNAs. miRNAs suppress gene expression by directly binding the 3’-untranslated region (UTR) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs). miRNA/mRNA pairing induces mRNA decay via mRNA deadenylation/uncapping, or inhibition of protein synthesis via translational repression. Metazoan miRNAs target mRNAs containing sequences that complement the miRNA’s “seed” region, which comprises nucleotides 2–7 (of 21–24). The genes that may be negatively regulated by any given miRNA can be predicted in silico using ad hoc algorithms. Such prediction tools generally identify hundreds of candidate target genes that may be under the control of a specific miRNA. In agreement with in silico predictions, gene expression studies have shown that mRNAs containing sequences with perfect complementarity to the seed region of a specific miRNA are globally (albeit not exhaustively) downregulated or upregulated upon miRNA overexpression or knockdown, respectively, in selected cell types. It should be noted that perturbing miRNA activity may affect the abundance of mRNAs that are not direct miRNA targets; this may occur via indirect (mostly transcriptional) effects mediated by changes in the direct target mRNAs.

Although individual miRNAs are predicted to modulate the stability of dozens of mRNAs directly, miRNA knockout, knockdown or overexpression systems typically show modest changes to individual transcript or protein levels, generally below 20% of the baseline value [77,78]. This likely depends on miRNA abundance and other ill-defined features of seed-pair stoichiometry. Thus, each miRNA may provide only a modest contribution to gene regulation. Supporting this notion, most of the individual-miRNA knockout organisms do not display obvious phenotypes, as shown in Caenorabditis elegans [79] and mice [80]. Furthermore, a recent study that used a miRNA reporter (‘sensor’) library to measure the activity of individual miRNAs showed that less than 40% of the miRNAs identified in a cell have detectable activity, indicating that the functional 'miRNAome' of a cell is considerably smaller than currently inferred from miRNA profiling studies [81]. While these observations may suggest redundancy between miRNA family members, it is likely that many miRNA–mRNA interactions mostly function to finely buffer gene expression oscillations in response to exogenous stimuli by modulating selected posttranscriptional checkpoints. Undeniably, the conservation through evolution of miRNA-mRNA interactions suggests that miRNAs play an important role in fine-tuning gene expression networks in both homeostasis and disease [82,83].

High-throughput miRNA profiling studies of human cancer indicate that defined miRNA expression signatures associate with specific tumor types and subtypes, and may have predictive value (Box 2). Nevertheless, most miRNA profiling studies sampled whole-tumor tissues, which comprise not only cancer cells but also variable proportions of cancer-associated fibroblasts, endothelial cells (ECs) and various immune cell types, all of which are known to modulate tumor progression [2] and express miRNAs at variable levels [3–5]. Thus, whole-tumor miRNA signatures and their alterations during tumor progression, or following cancer therapy, may reflect changes within both cancer and stromal cells.

Box 2. miRNAs and cancer.

Expression of several miRNAs is deregulated in tumors when compared to their tissues of origin, and there is increasing evidence that such deregulation can potentially modulate the cell’s gene expression network [84,85]. The first evidence for miRNA deregulation in cancer came from studies by Croce and colleagues, who documented decreased expression of miR-15 and miR-16 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia as a consequence of 13q14.3 chromosomal deletion [86]. Although miRNAs may be globally downregulated in human cancer, possibly as a consequence of acquired genetic deficiencies in the miRNA processing machinery [71], individual miRNAs can be upregulated in cancer through several mechanisms including transcriptional deregulation, DNA mutations, copy number abnormalities and epigenetic alterations. The upregulation of ‘oncomiRs’ such as miR-21, the miR-17~92 cluster and miR-155, or the loss of “tumor-suppressor miRNAs” such as let-7, miR-15/16 and miR-146, have been suggested as drivers of different types of hematological and solid cancers via cell-autonomous gene regulation in cancer cells. Evidence also exists that miRNAs such as miR-10b, miR-31 and miR-103/107 control the invasive and metastatic properties of cancer cells. The mechanisms by which miRNAs promote carcinogenesis and the significance of miRNA deregulation in cancer cells are reviewed elsewhere [84,85,87].

Extensive research over the past decade implicates tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), or large subpopulations thereof, as tumor-supporting cells [6–9]. TAMs promote malignant progression by stimulating angiogenesis; enhancing tumor cell migration; facilitating tumor cell intravasation at the primary site and extravasation at metastatic sites; and suppressing antitumor immunity. TAM precursors [10] may also induce tolerance towards cancer cells before they enter the tumor stroma [11]. Clinical studies have largely validated findings in mice, and the presence of high TAM numbers in several human cancer types, including Hodgkin’s lymphoma, breast, ovarian and non-small cell lung cancer, may correlate with adverse outcome and shorter survival [7].

Recent reports have begun to unravel the significance of miRNA expression in monocytes/macrophages. While studies have largely focused on cultured cells, their results suggest that miRNA activity can modulate macrophage responses to environmental signals. Cancer-related studies also explored how macrophages and their precursors can be co-opted by tumors to generate a supportive stroma. It is increasingly apparent that miRNAs modulate the unfolding macrophage response to cancer by acting on these cells’ precursors, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

Here, we review mechanisms by which miRNAs control macrophage production, differentiation and fate; explore how miRNAs may modulate TAMs’ protumoral functions; and evaluate whether targeting miRNAs to tailor the host’s response to cancer represents a valuable approach in anticancer therapy. We use macrophages as a vantage point from which to consider the role of miRNAs in inflammation and cancer, although other stromal cell types that ostensibly contribute to tumor progression [2] should be also investigated carefully.

miRNA-mediated regulation of macrophage production

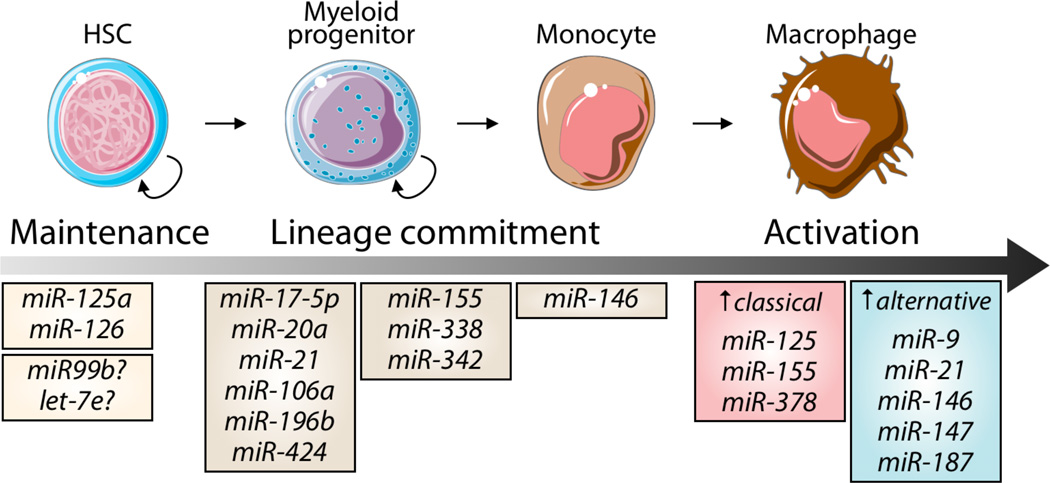

TAMs are typically short-lived and unlikely to proliferate in tumor tissue [10,12], therefore they must be continuously replenished by newly produced precursors throughout cancer growth. Tumors frequently activate a macrophage progenitor response characterized by the sustained amplification of bone marrow (BM)-derived HSCs and myeloid progenitors, followed by the production of monocytes and the recruitment of these monocytes to tumors for local differentiation into macrophages [13]. Below we present evidence that all stages of macrophage production and amplification, even in the absence of cancer, are probably modulated by miRNAs (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of miRNAs implicated in macrophage development and activation.

Defined miRNAs control HSC maintenance, whereas others guide hematopoietic cell commitment toward the mononuclear phagocyte lineage (at steady-state), and/or control macrophage activation. The induction of miRNAs is context-dependent and is triggered and controlled by cell exogenous and endogenous cues (see also Figure 2).

HSC maintenance

Microenvironmental niches in the BM harbor HSCs and regulate their maintenance and clonogenic activity. Several exogenous and endogenous cues guide the decision between HSC self-renewal or differentiation, and recent research identifies miRNAs as important endogenous regulators of HSC fate. Genetically ablating Dicer has revealed that the miRNA processing enzyme is necessary for maintaining long-term repopulation by HSCs in vivo [14]. A miRNA cluster containing miR-125a, miR-99b and let-7e is preferentially expressed by long-term HSCs, and miR-125a alone may regulate HSC survival and engraftment by silencing the proapoptotic factors BCL2-homologous antagonist/killer (BAK1), Krueppel-like factor-13 (KLF13), and BCL2-modifying factor (BMF) [14]. miR-126, a miRNA expressed in HSCs, restrains cell-cycle progression and hematopoietic output by regulating the phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) / AKT pathway, hence limiting signal transduction in response to exogenous cues like stem cell factor (SCF, also known as kit-ligand) [15].

HSC differentiation into monocytes

Several miRNAs appear to influence the commitment of HSCs and their progenitors. For instance, miR-146a, miR-155, miR-342 and miR-338 are upregulated by the transcription factor PU.1 [16,17], which controls myeloid cell development. Ectopic expression of miR-146a is sufficient to direct HSC differentiation to the mononuclear phagocyte lineage in mouse transplantation assays [16].

miR-21 and miR-196b have been shown to promote monocytopoiesis and to antagonize granulopoiesis, respectively [18]. Of note, the growth factor-independent-1-transcription repressor (GFI1), which is required for granulopoiesis, suppresses both miR-21 and miR-196b; this illustrates a cooperative role between GFI1 and miR-21/196b in regulating the balance between monocyto- and granulopoiesis [18]. While broadly expressed in myeloid cells, miR-223 also appears to control specific aspects of granulocyte biology. Indeed, miR-223 was shown to divert myeloid progenitors to the granulocytic lineage [19] in a process that involves downregulation of nuclear factor 1 A-type (NFI-A) [20] and myocyte specific enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C) [21], which are both negative regulators of granulopoiesis.

Commitment toward the mononuclear phagocyte lineage can be instructed by the colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) through its receptor, CSF-1R. Interestingly, miR-17-5p, miR-20a and miR-106a cooperate to suppress monocyte production by targeting Runt-related transcription factor-1 (RUNX1, also known as AML1), which promotes CSF-1R expression [22]. Interestingly, transcription of these miRNAs appears to be regulated through RUNX1-mediated repression [22] or epigenetic silencing [23]. These observations suggest that a negative feedback loop, involving RUNX1 and miR-17-5p/20a/106a, controls monocyte output from common myeloid progenitors. Additionally, miR-424 was shown to stimulate mononuclear phagocyte differentiation by increasing CSF-1R and decreasing NFI-A expression [24].

Monocyte differentiation into macrophages

Monocytes consist of at least two functionally distinct subsets: mouse Ly-6Chi (human CD14hi) cells, which are inflammatory, and mouse Ly-6Clo (human CD14lo/CD16+) cells, which may facilitate the resolution of tissue inflammation [25]. At steady-state, Ly-6Clo monocytes constitutively express miR-146a, which may control their antiinflammatory functions. Following inflammatory challenge, however, Ly-6Chi monocytes selectively induce miR-146a expression, and this process limits the magnitude of the inflammatory response mediated by these cells [26]. miR-146a-mediated gene regulation in monocyte subsets is cell-autonomous and depends on the non-canonical nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) member RELB, which is a direct target of this miRNA. miR-146 is also differentially regulated in human monocyte subsets [26].

miR-146a upregulation controls several biological functions of Ly-6Chi monocytes. First, it suppresses expansion of these cells in the BM [26]. In line with this finding, aging mir146a−/− mice can show chronic BM myeloproliferation and develop myeloid malignancies [27]. Second, in young and healthy mice, miR-146a impairs the expression of the CCL2 receptor, CCR2 [26]. This chemokine receptor is normally expressed by Ly-6Chi monocytes and attracts them to sites of inflammation, including the tumor stroma, where they differentiate into macrophages [7,10,28]. Thus, miR-146a may control the expansion of inflammatory monocyte precursors and their recruitment to inflamed tissues. Other miRNAs, including miR-20b, -29b, -135a, -150, -155, -342, -424 and -702, are also differentially expressed in monocyte subsets [26], but their function in these cells has yet to be investigated.

Whether miRNA-mediated control of macrophage production influences cancer growth and/or progression remains to be tested experimentally. Interestingly, the human miR-146a gene contains the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs2910164, which reduces miRNA-mediated repression of predicted target transcripts. Consequently, the differential ability of miR-146a polymorphisms to silence its natural targets macrophage precursors might, in turn, alter TAM production. Several studies have attempted to associate SNP rs2910164 with disease phenotypes in different cancer types (e.g. ref [29]); however, such investigations have not yet dissected cancer and stromal cell populations. The inclusion of TAM or circulating monocyte SNP profiles in future studies might provide useful information.

Together, the findings outlined above suggest that combinatorial activity of miRNAs controls multiple stages of mononuclear phagocyte development and affects the fate of monocytes/macrophages, both before and after they are recruited to tumors to exert their effector functions.

miRNA-mediated control of macrophage activation

Macrophages residing in distinct tissue microenvironments can display divergent phenotypes and functions [7,30,31]. Such heterogeneity is defined by the identity of the precursor from which the macrophage derives and by these cells’ ability to interact with, and respond to, factors to which they are exposed locally. When engaged, different macrophage receptors activate distinct intracellular molecular pathways and, consequently, activation states in macrophages. Mirroring Th1 and Th2 activation of lymphocytes, macrophages can be either classically (M1) or alternatively (M2) activated (Box 3). Classically activated macrophages respond to intracellular bacteria/viruses, whereas alternatively activated macrophages sense parasites and promote angiogenesis and wound healing [30]. Classic and alternative activation represent extremes of a phenotypic continuum; indeed, intermediate/mixed activation states largely predominate in vivo [32].

Box 3. Classical versus alternative macrophage activation.

Bacterial products (such as the toll-like receptor [TLR] agonist lipopolysaccharide [LPS]), and several proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., interferons [IFNs] and TNF-α) promote the classical (M1) activation of macrophages and induce these cells to produce high levels of proinflammatory (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1) and angiostatic cytokines (e.g., CXCL10, IL-12). On the other hand, the cytokines IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10, glucocorticoids and TGF-β favor the induction of an alternative (M2) activation state that is associated with lower secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and enhanced expression of tissue-remodeling and proangiogenic factors. In the context of M2-like activation, several phenotypes have been described based on in vitro stimulation of macrophages with different cytokines. These include “M2a”, which is induced by IL-4 and IL-13; “M2b”, induced through exposure to immune complexes and TLR or IL-1R agonists; and “M2c”, induced by IL-10 [88].

Classical activation

NF-κB, which consists of p50 and p65 heterodimers, is a key regulator of classical macrophage activation. NF-κB is normally sequestered in the cytoplasm by κB inhibitors (IκBs). Sensing TLR ligands triggers recruitment of the adaptor MyD88, which activates the signaling adaptor molecules IRAK and TRAF6 as well as the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. This induces rapid degradation of IκB proteins, thereby allowing NF-κB to be translocated to the nucleus and activate the transcription of proinflammatory genes. NF-κB is also activated by IL-1 and TNF-α via binding to IL-1R and TNFRs, respectively, and by type I IFNs in a STAT1-dependent manner. Classical macrophage activation also induces negative regulators, such as SOCS1, which promote ubiquitylation and degradation of proinflammatory molecules (e.g., p65 and MyD88-adaptor-like protein MAL, also known as TIRAP). TLR sensing also activates the PI3K pathway, which attenuates the inflammatory response via AKT. In summary, the activation of several inhibitory pathways can prevent hyper-responsiveness to exogenous inflammatory cues.

Alternative activation

IL-4Rα triggering induces STAT6 phosphorylation and dimerization followed by transcriptional activation of genes that are associated with alternative macrophage activation. IL-4Rα activation also triggers the PI3K–AKT pathway, which not only induces expression of alternative activation genes (e.g., Chi3l3 (YM1), Retnla and Arg1) but also phosphorylates the NF-κB negative regulator IKKα. Peritoneal macrophages lacking SHIP1, a negative regulator of the PI3K–AKT pathway, are more prone to alternative activation. SHIP1 can also be downregulated by IL-4. Thus, the PI3K–AKT pathway likely promotes alternative – and attenuates classical – macrophage activation. Two AKT isoforms, AKT1 and AKT2, may differentially contribute to macrophage polarization, with AKT1 promoting alternative activation and AKT2 promoting classical activation [89]. The Histone 3 Lys27 demethylase (JMJD3) also induces the expression of IRF4, a transcription factor that regulates the expression of several M2-associated genes, whereas IL-10 is thought to promote antiinflammatory responses by inhibiting the synthesis of TNFα and IFN-γ in an IL-10R- and STAT3-dependent manner. See also [59,90,91].

Interestingly, several miRNAs are thought to modulate macrophage activation and function in tissues. The majority of these miRNAs are rapidly upregulated in macrophages by Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands. Relevant miRNAs include miR-155, miR-125a/b, miR-146a, miR-21 and let-7e, all of which are conserved among mammalian species. Some of these miRNAs can either suppress (e.g., miR-146a) or promote (e.g., miR-155) proinflammatory responses, and some target key regulatory molecules involved in classical macrophage activation. Recent data also suggest that distinct miRNAs, such as miR-187, miR-378-3p and miR-511-3p, are induced upon alternative macrophage activation.

Multiple cytokines expressed in the tumor microenvironment, such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), CCL2, CSF-1, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and angiopoietin-2 (ANG2), are known to regulate macrophage development, recruitment, differentiation, and/or M1/M2-like activation in cancer [8] (Box 4). Many of these cytokines modulate miRNA expression and activity in different cell types, including cultured monocytes/macrophages, but little is known about their ability to control miRNA function in TAMs (see below). Furthermore, multiple miRNAs (e.g., miR-23, -24, -26, -27, -103, -107, -181, -210 and -213) are induced by hypoxia, which is a hallmark of the tumor microenvironment. However, the expression of such hypoxia-inducible miRNAs [33] in TAMs, and their relevance for TAMs’ effector functions, remain to be investigated.

Box 4. Activation states of tumor–associated macrophages.

TAMs’ protumoral functions may depend on their secretion of i) growth and proangiogenic factors, including members of the epidermal (EGF), fibroblast (FGF) and vascular (VEGF/PlGF) growth factors families; ii) TGF-β, which stimulates cancer-associated fibroblasts to synthesize extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules and cancer cells to acquire a proinvasive phenotype; iii) proteolytic and tissue-remodeling enzymes, such as matrix-metalloproteinases (MMPs) and cathepsins, which facilitate tumor angiogenesis and ECM remodeling; and iv) cytokines, cell surface receptors and other factors that suppress antitumor immunity.

TAMs isolated from mouse tumors often display impaired proinflammatory cytokine production in response to LPS and enhanced expression of alternative activation markers [92,93]. M2-skewing of TAMs may rely on defective NF-κB activation and enhanced PI3K–AKT signaling [89,94]; however, NF-κB activation in TAMs can also stimulate their immunosuppressive functions [95]. Among the cytokines expressed in the tumor microenvironment, IL-4, IL-10, TGF-β and CSF-1 may skew TAMs toward an alternatively activated (M2-like) phenotype [59,96]. TAMs seem to preferentially acquire an alternatively activated phenotype in perivascular areas of the tumor, possibly under the influence of ‘angiocrine’ signals produced by tumor ECs [97]. This is consistent with the previously reported proangiogenic activity of perivascular TAMs [98,99].

While there is experimental evidence that the tumor microenvironment enhances the immunosuppressive and trophic functions of TAMs, it is increasingly appreciated that these cells comprise a heterogeneous assortment of phenotypes, even within individual tumors. For example, gene profiling studies of mouse TAMs fractionated based on their expression of prototypical classic and alternative activation markers has revealed a considerable degree of heterogeneity between these subsets [63,93,100]. In mouse tumors, MRC1+CD163+CD11cloMHCIIlo TAMs represent the most alternatively activated subset; they are mostly perivascular and express high levels of tissue-remodeling enzymes and ECM receptors but low levels of classic proinflammatory cytokines. Instead, MRC1lowCD163lowCD11c+MHCIIhi TAMs, which possibly represent deactivated DCs, bear intermediate features of classically and alternatively activated macrophages, appear markedly more pro-inflammatory, and are essentially found in poorly vascularized or necrotic tumor areas [9,63]. These data point toward the existence of TAM subsets with discrete functional abilities.

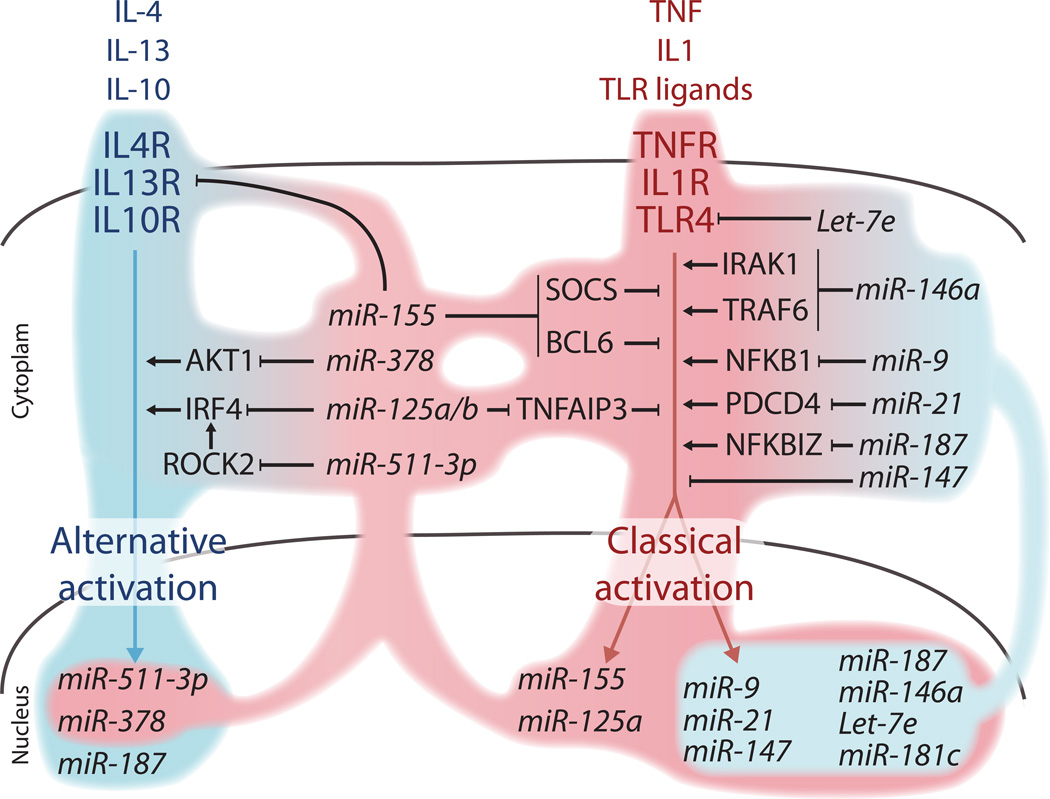

Below we discuss the reported roles of selected miRNAs in the context of macrophage differentiation and activation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Regulation of classical and alternative macrophage activation by miRNAs.

The schematic illustrates prototypical ligand/receptor pairs that stimulate either the alternative (or M2; left, blue) or the classical (or M1; right, pink) activation of macrophages. Several miRNAs are induced upon either type of macrophage activation. These include miRNAs that primarily sustain classical activation (pink-shaded contours) either by enhancing proinflammatory signaling (e.g., miR-155, miR-125a/b) or by attenuating alternative activation (e.g., miR-511-3p, miR-378 and miR-155). Other miRNAs conversely attenuate classical activation (blue-shaded contours) by repressing several positive regulators of proinflammatory signaling (e.g., miR-146a, miR187 and Let-7e). Note that miR-155 may also function as a negative regulator of proinflammatory signaling (not depicted; see main text). Signaling molecules implicated in classical versus alternative activation of macrophages, and related to miRNAs, are discussed in the main text.

miR-155

The gene encoding miR-155 is located in the B-cell integration cluster (BIC), which is a long-intergenic non-coding (linc) RNA. miR-155 is also rapidly upregulated by NF-κB in macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) in response to several TLR ligands and type I interferons (IFNs), the latter probably via TNF-α induction [34]. miR-155 is best characterized as a proinflammatory miRNA because it enhances the production of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages and other immune cell types. Indeed, whereas miRNAs typically destabilize mRNAs upon binding to their 3’-UTR, miR-155 was reported to increase TNF-α production by stabilizing the Tnfa transcript [35,36]. However, the regulation of Tnfa mRNA stability by miR-155 requires further study. It is possible that yet unidentified miR-155 target(s) may directly control Tnfa mRNA production and/or degradation.

miR-155 also promotes classical macrophage activation by down regulating inhibitors of the proinflammatory response, like suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS1) [37,38] and B-cell lymphoma-6 protein (BCL6) [39]. Furthermore, miR-155 targets the IL-13 receptor, IL13RA1 [40], which promotes alternative macrophage activation. Interestingly, a recent gain of function study showed that miR-155 delivery in alternatively activated macrophages is sufficient to reprogram these cells toward a more proinflammatory phenotype [41]. This altered phenotype not only enhances TNF-α production, but also downregulates the alternative activation genes arginase-1 (Arg1), chitinase 3-like 3 (Chi3l3), and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta (C/EBPβ) in the macrophages [42]. These findings are consistent with the observation that tumor growth is enhanced in mir155−/− mice [43].

The aforementioned data suggest that miR-155 induction by inflammatory signaling sustains or even amplifies classical proinflammatory macrophage activation. However, miR-155 may exert more complex functions, as it was shown to also target key molecules involved in proinflammatory signal transduction, including myeloid differentiation primary response-88 (MyD88), TAK1-binding protein (TAB2), and PIP3-5-phosphatase-1 (SHIP1) [44–47]. Since SHIP1 negatively regulates the PI3K/AKT1 pathway, SHIP1 repression by miR-155 may increase AKT1 signaling and promote alternative macrophage activation [47]. AKT may further impair proinflammatory responses by downregulating miR-155 and miR-125b (see below) and by upregulating miR-181c and Let-7e [37]. In summary, while miR-155 appears to primarily enhance proinflammatory activation of macrophages, there is also evidence that it can function as a negative regulator of overwhelming inflammatory responses.

miR-125

The miR-125 family is composed of the miR-125a/b-1/b-2 members, which are the mammalian homologues to Caenorabditis elegans lin-4. The miR-125 members are found in distinct genomic locations, may be transcribed independently, and exhibit different expression profiles and functions. BM-derived macrophages (BMDMs) can express high levels of both miR-125a and miR-125b; however, miR-125a is upregulated [48], whereas miR-125b is downregulated [37,49] by LPS. Recent studies nevertheless suggest that both miRNAs enhance NF-κB signaling by targeting the negative NF-κB regulator, TNFAIP3 [50]. Consistently, macrophages that overexpress miR-125b are highly responsive to IFN-γ and potently activate T-cell responses [51]. miR-125b also binds to the 3’-UTR of Tnfa mRNA to destabilize the transcript; thus, miR-125b downregulation by LPS may unleash TNF-α production [37]. miR-125b can also sustain proinflammatory cell activation by targeting the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor-4 (IRF4) [51], which promotes alternative macrophage activation. These initial observations support the notion that miR-125a/b regulation by proinflammatory stimuli finely tunes TNF-α production, NF-κB activation, and IFN-γ signaling in macrophages.

miR-146

The miR-146 family includes two members, miR-146a/b. Although their genes are located on different chromosomes, these two miRNAs’ high homology (>90%) and identical seed sequence suggest that they repress the same target genes and control similar biological processes. Taganov and colleagues first reported that miR-146 modulates macrophage function and identified this miRNA as a bona fide negative regulator of classical NF-κB activation [52]. They also found that THP-1 cells, a macrophage cell line, upregulate miR-146 in response to LPS. miR-146 expression is induced via TLR-2, -4, and -5 signaling and NF-κB activation. Interestingly, IL1R–associated kinase (IRAK1) and TNFR-associated factor (TRAF6), two key adaptor molecules in the TLR/NF-κB pathway, are direct targets of miR-146. This suggests that TLR/NF-κB activation and miR-146 expression establish a negative regulatory loop: NF-κB activation initiates the production of proinflammatory cytokines and of miR-146, which in turn targets IRAK1 and TRAF6, thus leading to reduced TLR signaling and attenuated proinflammatory cytokine production [52]. Accordingly, targeted deletion of miR-146a in mice results in heightened proinflammatory cytokine production by macrophages [53]. miR-146 is also a dominant regulator of myeloid progenitor cell amplification, as discussed above.

miR-9, -21, and -147

miR-9 [54], miR-21 [55] and miR-147 [56] can all be induced by several TLR agonists in a MyD88 and NF-kB-dependent manner and, like miR-146, are thought to inhibit proinflammatory responses in monocytes/macrophages by suppressing NF-kB activation through a negative feedback loop mechanism. In LPS-treated human monocytes, miR-9 targets the NFKB1 transcript encoding for the NF-kB subunit p50, thus limiting NF-kB activation [54]. However, experimental overexpression of p50 can inhibit NF-kB signaling and M1 activation in TAMs by inducing the formation of inhibitory p50 NF-kB homodimers [57]. Thus, miR-9 could also function as a positive regulator of NF-kB signaling by limiting the formation of inhibitory complexes.

miR-21 is upregulated in various cancers and is known to control the tumor suppressor, programmed cell death protein-4 (PDCD4) [58]. Recent evidence indicates that TLR4 signaling in macrophages suppresses PDCD4 expression through induction of miR-21 [55]; this process may limit excessive inflammation by suppressing NF-kB activation. Decreased levels of PDCD4 also increase IL-10 production in macrophages [55]. It is worth noting that IL-10 inhibits transcriptional elongation of Tnfa; sustains IL-4–induced alternative activation by promoting signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) signaling; and operates as a potent negative regulator of inflammation [59].

miR-223

miR-223 is transcribed from a lincRNA. As mentioned above, it is preferentially expressed in the myeloid lineage, granulocytes in particular. Recent studies have suggested that miR-223 is induced by LPS and may limit inflammatory activation of macrophages [60]. Indeed, miR-223-deficient BMDMs express significantly higher levels of the LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα, than wild-type cells. While Pknox1 was identified as natural target of miR-223, it is currently unknown whether it directly modulates macrophage activation [60].

miR-187

IL-10 signaling induces miR-187 upregulation in human (but not mouse) monocytes, an effect that is augmented by LPS co-stimulation [61]. IL-10 potentiates LPS-induced miR-187 transcription, as shown by the recruitment of Pol-II to the miR-187 locus and increased pre-miR-187 levels observed following LPS/IL-10 stimulation of human monocytes. Both phenotypes can be abolished by treatment with IL-10-blocking antibodies. miR-187 recruits TNFA mRNA directly to the RISC complex, thereby promoting mRNA degradation. Furthermore, miR-187 silencing indirectly enhances the expression of the LPS-induced cytokines IL-6 and IL-12p40. Mechanistically, downregulation of IL-6 and IL12p40 by miR-187 may rely on direct targeting of NFKBIZ, the gene encoding IκBζ (also known as MAIL), which is a positiv transcriptional regulator of IL-6 and IL-12p40 expression [61]. These findings position miR-187 as a novel regulator of IL-10-induced anti-inflammatory responses in human macrophages.

miR-378-3p

The miR-378 gene is located in the first intron of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (Ppargc1b) gene. miR-378-3p expression is upregulated in macrophages by alternative activation stimuli such as IL-4 and the parasitic nematode Brugia malayi [62]. miR-378-3p negatively regulates AKT1 signaling in macrophages, which limits IL-4-induced upregulation of Arg1, resistin like alpha (Retnla) and Chi3l3. Thus, miR-378-3p may operate in a negative-feedback loop to limit the alternative activation of macrophages [62].

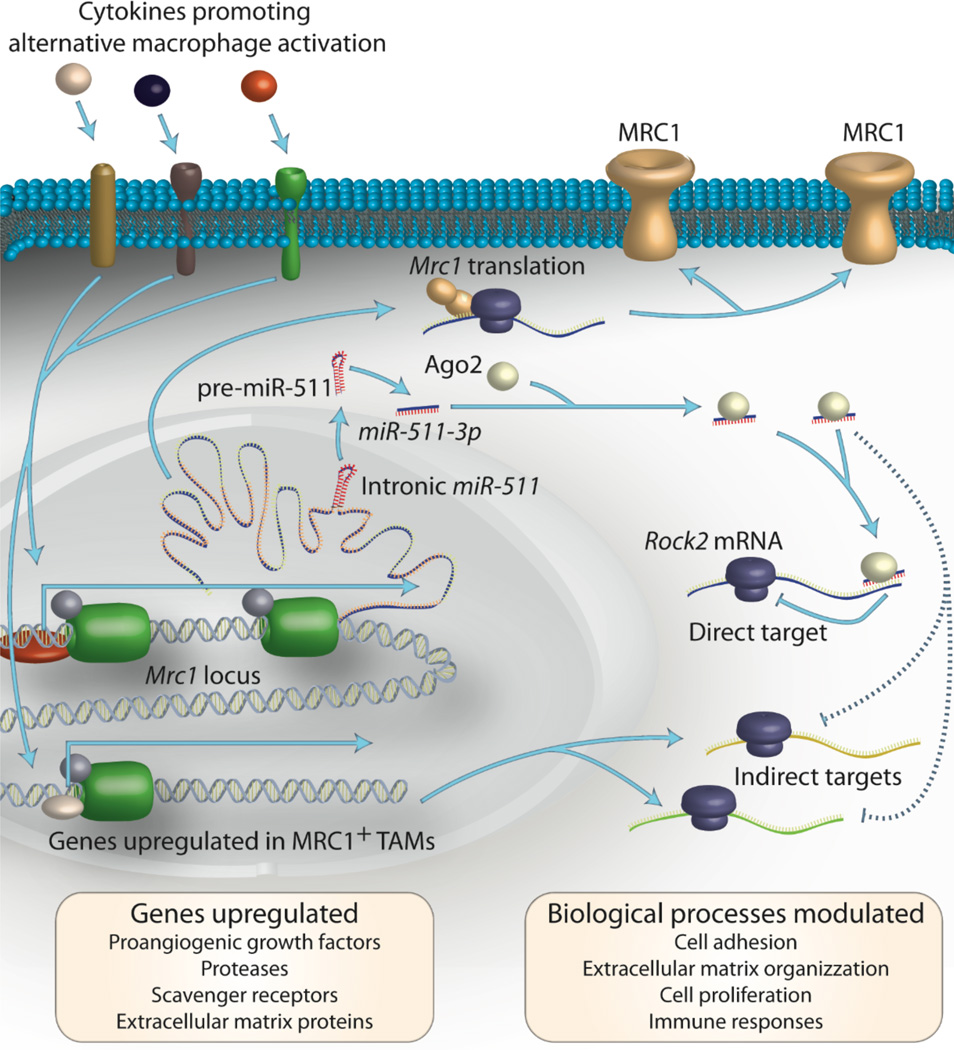

miR-511-3p

miR-511-3p is located in the fifth intron of both mouse and human MRC1 genes [63], which encode the macrophage mannose receptor (also known as CD206) and are potently upregulated in macrophages upon their alternative activation [64]. The expression of miR-511-3p is co-regulated with that of the hosting gene, which makes miR-511-3p a prototypical alternative activation miRNA. To our knowledge, miR-511-3p is the first miRNA whose activity and function were studied directly in TAMs in vivo [63].

The use of miRNA ‘sensor’ lentiviral vectors (LVs) has shown that miR-511-3p is upregulated in multiple populations of alternatively activated macrophages (Figure 3), including IL-4-stimulated BMDMs, MRC1+ adipose-tissue macrophages, and MRC1+ TAMs [63]. miR-511-5p [65], which is the mature strand of pre-miR-511 initially annotated in miRBase, is less abundant and active than the -3p strand [63], as confirmed recently by highthroughput miRNA sequencing [66]. Interestingly, artificial miR-511-3p upregulation can tune down the expression of alternative activation genes in MRC1+ TAMs without altering the gene signature of proinflammatory TAMs; this suggests TAM-subtype-specific miRNA activity [63].

Figure 3. miR-511-3p modulates TAM's phenotype.

Alternatively activated TAMs express the macrophages mannose receptor, MRC1, and upregulate a number of genes that underlie their protumoral functions (yellow box on the bottom left). Together with the coding sequence for MRC1, the Mrc1 gene promoter transcribes the primary miR-511, which is processed by the miRNA machinery to generate the mature miR-511-3p sequence. miR-511-3p directly targets a number of genes, including Rock2, which promotes alternative activation of macrophages by phosphorylating the transcription factor IRF4. miR-511-3p also modulates the expression of several indirect targets, which influence biological processes in the TAMs (yellow box on the bottom right). As a result, miR-511-3p may attenuate the protumoral functions of alternatively activated TAMs [63].

miR-511-3p–induced downregulation of alternative activation genes in TAMs is associated with tumor growth inhibition. These findings are consistent with the observation that miR-511-3p downregulates genes with protumoral effector function, including proteolytic enzymes and other extracellular matrix-remodeling molecules, specifically in MRC1+ TAMs [63]. Furthermore, miR-511-3p directly targets Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 2 (Rock2), a serine-threonine kinase that regulates the cell cytoskeleton contractility, and phosphorylates IRF4, a transcription factor that promotes alternative activation of macrophages. These findings suggest that miR-511-3p functions as an endogenous relay that attenuates the protumoral functions of alternatively activated TAMs [63].

Exogenous miRNAs in cell-to-cell communication

miRNAs can act within the cells in which they are produced but may be also transferred to other cell types. Recent studies suggest that macrophages and DCs produce miRNA-containing microvesicles (MVs) that can be conveyed to ‘acceptor’ cells upon fusing with their plasma membrane. For instance, DCs produce MV-shuttled miRNAs, which may downregulate the expression of target genes in acceptor DCs in vitro [67]. Other in vitro studies suggest that alternatively activated macrophages influence the invasive properties of breast cancer cells via MV-mediated transfer of miR-223. Macrophage-derived miR-223 was reported to downregulate MEF2C expression in cancer cells, leading to increased nuclear localization of β-catenin and increased cancer cell invasion [68].

miRNA communication amongst cells may also target macrophages. A recent study showed that some cancer cells produce MVs that contain miR-21 and miR-29b, which can be transferred to TAMs [69]. These miRNAs do not appear to interact with the 3’-UTR of their target genes, but instead bind to intracellular TLR7 and TLR8 to activate a proinflammatory and ‘prometastatic’ response in TAMs. These initial studies suggest that prometastatic TAM functions [7] can also be regulated by miRNAs that derive from cancer cells.

It should be emphasized, however, that most of the published reports could not rigorously distinguish miRNA transfer from endogenous induction mediated by MV-cell contacts. Furthermore, in vitro cell assays are likely to artificially enforce contacts between MVs and recipient cells, and thus may not fully recapitulate the complex conditions that control MV production, stability and uptake by acceptor cells in vivo [70]. Also, whereas it is experimentally feasible to enforce miRNA expression in MV-producing cells, it must be considered that cancer cells broadly downregulate miRNA expression [71], possibly limiting directional transfer of miRNA to macrophages or other cell types. As the details of MV biogenesis and miRNA loading get to be clarified, new strategies may enable the selective targeting of such MV-derived miRNAs and, consequently, a better understanding of their actual significance in vivo.

Significance of miRNA (de)regulation in macrophages for cancer

Our appreciation of miRNAs’ ability to control macrophage differentiation, activation and function in cancer remains limited. This lack of information may reflect today’s limited availability of genetic models that target individual miRNAs in (subsets of) TAMs. The majority of miRNAs that reportedly modulate macrophage activation in response to exogenous stimuli (e.g., miR-155 and miR-146) are indeed broadly expressed in multiple immune cell types, including T and B cells. Thus, studies using miRNA knockout mice are difficult to interpret. Future work should aim to develop genetic approaches that allow conditional miRNA loss or gain of function specifically in the cells of interest (i.e. TAMs or their circulating precursors). Recently implemented LV-based genetic tools enable (i) measuring miRNA activity in live cells (‘sensor’ vectors); (ii) knocking down individual miRNAs (‘sponge’ vectors); and (iii) overexpressing individual miRNAs (‘overexpressing’ vectors). These tools are revolutionizing the study of miRNA activity and function in live cells and genetically engineered mouse models [72]. Tissue-specific modulation of miRNA expression will enable researchers to get a more precise insight into the role of specific miRNAs in macrophages in vivo, both in homeostasis and in the context of cancer. LV-based genetic tools have already been used to study the activity and function of miR-511-3p in TAMs [63], as discussed above.

Interestingly, initial studies show that interfering with miRNA activity may reprogram the cell activation state by targeting critical molecular checkpoints that tune the balance between pro- and antitumoral macrophage functions. These results should encourage the development of pharmacological formulations that either suppress or enhance the activity of selected miRNAs to reprogram TAMs’ phenotype. Notable examples of such approaches include targeting of miR-155 [41], miR-223 [68], and miR-511-3p [63], among others. Recently, a proof-of-concept study reported effective targeting of CD11c+ TAMs/DCs by systemic delivery of nanoparticles loaded with miR-155 mimics [73]. Consistent with genetic studies [41], uptake and processing of these mimics by the tumor-infiltrating CD11c+ cells downregulated the expression of C/EBPβ and TGF-β signaling pathway members [73]. These nanoparticles are potentially clinically translatable and may serve to reprogram transcriptomic profiles and immunostimulatory properties of tumor-associated host cells. Other examples of miRNA delivery [74] or silencing [75,76] in mice and primates have been reported, and serve as proof-of-principle that miRNA-based therapies may become available to human patients in the near future.

Concluding remarks

This review illustrates that miRNAs tightly regulate the macrophage response to microenvironmental cues and may modulate TAM’s pro- versus antitumoral functions. It is also becoming clear that defined miRNAs regulate the biological properties of hematopoietic cells during the multiple stages of their development. However, it remains to be defined whether miRNAs operate differently as the cells progress along their maturation pathway. Several other considerations warrant investigation. For instance, most of our knowledge of miRNA biology comes from studies that investigated individual miRNAs. However, macrophage differentiation and/or activation in vivo is likely to be modulated by the concerted action of several miRNAs, which together act on key molecular pathways that are co-opted in cancer. It should be useful to define how a combination of deregulated miRNAs controls the expression of gene networks and, eventually, macrophage biology.

The significance of miRNAs for TAM function, both in mouse models and humans, and the relative contributions of cell-endogenous and cell-exogenous miRNAs in vivo, are still poorly understood and hence deserve further attention. Prospective findings in this research area bear scientific and therapeutic importance, because they could reveal novel mechanisms controlling cancer growth and progression and consequently provide new molecular targets for disease treatment.

Highlights.

-

-

miRNAs modulate macrophage activation

-

-

miRNAs modulate all stages of macrophage production and amplification

-

-

miRNAs control macrophage function in tumors

-

-

Altered miRNA expression in macrophages modulates tumor progression Highlights

Acknowledgements

We apologize to the authors whose work we could not cite because of the limit on the number of references. This work was supported in part by the European Research Council (ERC), the National Centres of Competence in Research (Oncology Program), Fonds National Suisse de la Recherche Scientifique (SNSF), and Anna Fuller fund (to M.D.P), and by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01-AI084880, P50-CA086355 and U54-CA126515 (to M.J.P.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsay MA. microRNAs and the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitra AK, Zillhardt M, Hua Y, et al. MicroRNAs Reprogram Normal Fibroblasts into Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:1100–1108. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Connell RM, Rao DS, Baltimore D. microRNA regulation of inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:295–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1155–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruffell B, Affara NI, Coussens LM. Differential macrophage programming in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Squadrito ML, De Palma M. Macrophage regulation of tumor angiogenesis: implications for cancer therapy. Mol Aspects Med. 2011;32:123–145. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Newton A, et al. Origins of tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2491–2496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113744109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ugel S, Peranzoni E, Desantis G, et al. Immune tolerance to tumor antigens occurs in a specialized environment of the spleen. Cell Rep. 2012;2:628–639. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawanobori Y, Ueha S, Kurachi M, et al. Chemokine-mediated rapid turnover of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. Blood. 2008;111:5457–5466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-136895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Pittet MJ. Regulation of macrophage and dendritic cell responses by their lineage precursors. J Innate Immun. 2012;4:411–423. doi: 10.1159/000335733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo S, Lu J, Schlanger R, et al. MicroRNA miR-125a controls hematopoietic stem cell number. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14229–14234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913574107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lechman ER, Gentner B, van Galen P, et al. Attenuation of miR-126 Activity Expands HSC In Vivo without Exhaustion. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghani S, Riemke P, Schonheit J, et al. Macrophage development from HSCs requires PU.1-coordinated microRNA expression. Blood. 2011;118:2275–2284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-335141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jurkin J, Schichl YM, Koeffel R, et al. miR-146a is differentially expressed by myeloid dendritic cell subsets and desensitizes cells to TLR2-dependent activation. J Immunol. 2010;184:4955–4965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velu CS, Baktula AM, Grimes HL. Gfi1 regulates miR-21 and miR-196b to control myelopoiesis. Blood. 2009;113:4720–4728. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazi F, Racanicchi S, Zardo G, et al. Epigenetic silencing of the myelopoiesis regulator microRNA-223 by the AML1/ETO oncoprotein. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starnes LM, Sorrentino A, Pelosi E, et al. NFI-A directs the fate of hematopoietic progenitors to the erythroid or granulocytic lineage and controls beta-globin and G-CSF receptor expression. Blood. 2009;114:1753–1763. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuler A, Schwieger M, Engelmann A, et al. The MADS transcription factor Mef2c is a pivotal modulator of myeloid cell fate. Blood. 2008;111:4532–4541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontana L, Pelosi E, Greco P, et al. MicroRNAs 17-5p-20a-106a control monocytopoiesis through AML1 targeting and M-CSF receptor upregulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:775–787. doi: 10.1038/ncb1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pospisil V, Vargova K, Kokavec J, et al. Epigenetic silencing of the oncogenic miR-17-92 cluster during PU.1-directed macrophage differentiation. EMBO J. 2011;30:4450–4464. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosa A, Ballarino M, Sorrentino A, et al. The interplay between the master transcription factor PU.1 and miR-424 regulates human monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19849–19854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706963104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, et al. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3037–3047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etzrodt M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Newton A, et al. Regulation of monocyte functional heterogeneity by miR-146a and Relb. Cell Rep. 2012;1:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao JL, Rao DS, Boldin MP, Taganov KD, O'Connell RM, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB dysregulation in microRNA-146a–deficient mice drives the development of myeloid malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9184–9189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105398108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Newton A, et al. Angiotensin II Drives the Production of Tumor-Promoting Macrophages. Immunity. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jazdzewski K, Liyanarachchi S, Swierniak M, et al. Polymorphic mature microRNAs from passenger strand of pre-miR-146a contribute to thyroid cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1502–1505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812591106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mantovani A, Biswas SK, Galdiero MR, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J Pathol. 2013;229:176–185. doi: 10.1002/path.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:787–795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulshreshtha R, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, et al. A microRNA signature of hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1859–1867. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01395-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1604–1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610731104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bala S, Marcos M, Kodys K, et al. Up-regulation of microRNA-155 in macrophages contributes to increased tumor necrosis factor {alpha} (TNF{alpha}) production via increased mRNA half-life in alcoholic liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1436–1444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tili E, Croce CM, Michaille JJ. miR-155: on the crosstalk between inflammation and cancer. Int Rev Immunol. 2009;28:264–284. doi: 10.1080/08830180903093796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Androulidaki A, Iliopoulos D, Arranz A, et al. The kinase Akt1 controls macrophage response to lipopolysaccharide by regulating microRNAs. Immunity. 2009;31:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang P, Hou J, Lin L, et al. Inducible microRNA-155 feedback promotes type I IFN signaling in antiviral innate immunity by targeting suppressor of cytokine signaling 1. J Immunol. 2010;185:6226–6233. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nazari-Jahantigh M, Wei Y, Noels H, et al. MicroRNA-155 promotes atherosclerosis by repressing Bcl6 in macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4190–4202. doi: 10.1172/JCI61716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez-Nunez RT, Louafi F, Sanchez-Elsner T. The interleukin 13 (IL-13) pathway in human macrophages is modulated by microRNA-155 via direct targeting of interleukin 13 receptor alpha1 (IL13Ralpha1) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1786–1794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai X, Yin Y, Li N, et al. Re-polarization of tumor-associated macrophages to pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages by microRNA-155. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:341–343. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He M, Xu Z, Ding T, Kuang DM, Zheng L. MicroRNA-155 regulates inflammatory cytokine production in tumor-associated macrophages via targeting C/EBPbeta. Cell Mol Immunol. 2009;6:343–352. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huffaker TB, Hu R, Runtsch MC, et al. Epistasis between MicroRNAs 155 and 146a during T Cell-Mediated Antitumor Immunity. Cell Rep. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ceppi M, Pereira PM, Dunand-Sauthier I, et al. MicroRNA-155 modulates the interleukin-1 signaling pathway in activated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2735–2740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811073106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang B, Xiao B, Liu Z, et al. Identification of MyD88 as a novel target of miR-155, involved in negative regulation of Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1481–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou H, Huang X, Cui H, et al. miR-155 and its star-form partner miR-155* cooperatively regulate type I interferon production by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood. 2010;116:5885–5894. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-280156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7113–7118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graff JW, Dickson AM, Clay G, McCaffrey AP, Wilson ME. Identifying functional microRNAs in macrophages with polarized phenotypes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:21816–21825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tili E, Michaille JJ, Cimino A, et al. Modulation of miR-155 and miR-125b levels following lipopolysaccharide/TNF-alpha stimulation and their possible roles in regulating the response to endotoxin shock. J Immunol. 2007;179:5082–5089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim SW, Ramasamy K, Bouamar H, Lin AP, Jiang D, Aguiar RC. MicroRNAs miR-125a and miR-125b constitutively activate the NF-kappaB pathway by targeting the tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3, A20) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7865–7870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chaudhuri AA, So AY, Sinha N, et al. MicroRNA-125b potentiates macrophage activation. J Immunol. 2011;187:5062–5068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12481–12486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boldin MP, Taganov KD, Rao DS, et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on autoimmunity, myeloproliferation, and cancer in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1189–1201. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bazzoni F, Rossato M, Fabbri M, et al. Induction and regulatory function of miR-9 in human monocytes and neutrophils exposed to proinflammatory signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5282–5287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810909106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheedy FJ, Palsson-McDermott E, Hennessy EJ, et al. Negative regulation of TLR4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor PDCD4 by the microRNA miR-21. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:141–147. doi: 10.1038/ni.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu G, Friggeri A, Yang Y, Park YJ, Tsuruta Y, Abraham E. miR-147, a microRNA that is induced upon Toll-like receptor stimulation, regulates murine macrophage inflammatory responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15819–15824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901216106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saccani A, Schioppa T, Porta C, et al. p50 nuclear factor-kappaB overexpression in tumor-associated macrophages inhibits M1 inflammatory responses and antitumor resistance. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11432–11440. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asangani IA, Rasheed SA, Nikolova DA, et al. MicroRNA-21 (miR-21) post-transcriptionally downregulates tumor suppressor Pdcd4 and stimulates invasion, intravasation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:2128–2136. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhuang G, Meng C, Guo X, et al. A novel regulator of macrophage activation: miR-223 in obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Circulation. 2012;125:2892–2903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rossato M, Curtale G, Tamassia N, et al. IL-10-induced microRNA-187 negatively regulates TNF-alpha, IL-6, and IL-12p40 production in TLR4-stimulated monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E3101–E2110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruckerl D, Jenkins SJ, Laqtom NN, et al. Induction of IL-4Ralpha-dependent microRNAs identifies PI3K/Akt signaling as essential for IL-4-driven murine macrophage proliferation in vivo. Blood. 2012;120:2307–2316. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-408252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Squadrito ML, Pucci F, Magri L, et al. miR-511-3p modulates genetic programs of tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Rep. 2012;1:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martinez-Pomares L. The mannose receptor. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:1177–1186. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0512231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tserel L, Runnel T, Kisand K, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles of human blood monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages reveal miR-511 as putative positive regulator of Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:26487–26495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.213561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang HT, Li SC, Ho MR, et al. Comprehensive analysis of microRNAs in breast cancer. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:S18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-S7-S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Montecalvo A, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood. 2012;119:756–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang M, Chen J, Su F, et al. Microvesicles secreted by macrophages shuttle invasion-potentiating microRNAs into breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:117. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fabbri M, Paone A, Calore F, et al. MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2110–E2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209414109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pucci F, Pittet MJ. Molecular Pathways: Tumor-derived microvesicles and their interactions with immune cells in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0962. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar MS, Lu J, Mercer KL, Golub TR, Jacks T. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:673–677. doi: 10.1038/ng2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brown BD, Naldini L. Exploiting and antagonizing microRNA regulation for therapeutic and experimental applications. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:578–585. doi: 10.1038/nrg2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Baird JR, Tesone AJ, et al. Reprogramming tumor-associated dendritic cells in vivo using miRNA mimetics triggers protective immunity against ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1683–1693. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bader AG, Brown D, Winkler M. The promise of microRNA replacement therapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7027–7030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Elmen J, Lindow M, Schutz S, et al. LNA-mediated microRNA silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2008;452:896–899. doi: 10.1038/nature06783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lanford RE, Hildebrandt-Eriksen ES, Petri A, et al. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2010;327:198–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1178178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Abbott AL, et al. Most Caenorhabditis elegans microRNAs are individually not essential for development or viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Park CY, Jeker LT, Carver-Moore K, et al. A resource for the conditional ablation of microRNAs in the mouse. Cell Rep. 2012;1:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mullokandov G, Baccarini A, Ruzo A, et al. High-throughput assessment of microRNA activity and function using microRNA sensor and decoy libraries. Nat Methods. 2012;9:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pasquinelli AE. MicroRNAs and their targets: recognition, regulation and an emerging reciprocal relationship. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:271–282. doi: 10.1038/nrg3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kasinski AL, Slack FJ. Epigenetics and genetics. MicroRNAs en route to the clinic: progress in validating and targeting microRNAs for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:849–864. doi: 10.1038/nrc3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ryan BM, Robles AI, Harris CC. Genetic variation in microRNA networks: the implications for cancer research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrc2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Arranz A, Doxaki C, Vergadi E, et al. Akt1 and Akt2 protein kinases differentially contribute to macrophage polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9517–9522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119038109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lawrence T, Natoli G. Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: enabling diversity with identity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:750–761. doi: 10.1038/nri3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Biswas SK, Gangi L, Paul S, et al. A distinct and unique transcriptional program expressed by tumor-associated macrophages (defective NF-kappaB and enhanced IRF-3/STAT1 activation) Blood. 2006;107:2112–2122. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pucci F, Venneri MA, Biziato D, et al. A distinguishing gene signature shared by tumor-infiltrating Tie2-expressing monocytes, blood "resident" monocytes, and embryonic macrophages suggests common functions and developmental relationships. Blood. 2009;114:901–914. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-200931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guha M, Mackman N. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway limits lipopolysaccharide activation of signaling pathways and expression of inflammatory mediators in human monocytic cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32124–32132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hagemann T, Lawrence T, McNeish I, et al. "Re-educating" tumor-associated macrophages by targeting NF-kappaB. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1261–1268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.DeNardo DG, Barreto JB, Andreu P, et al. CD4(+) T cells regulate pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.He H, Xu J, Warren CM, et al. Endothelial cells provide an instructive niche for the differentiation and functional polarization of M2-like macrophages. Blood. 2012;120:3152–3162. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-422758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.De Palma M, Venneri MA, Galli R, et al. Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:211–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mazzieri R, Pucci F, Moi D, et al. Targeting the ANG2/TIE2 axis inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by impairing angiogenesis and disabling rebounds of proangiogenic myeloid cells. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:512–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5728–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]