Abstract

Acute graft versus host disease (GVHD) has been, and continues to compromise the benefits associated with allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation to cure malignant and non-malignant diseases. Pharmacologic interventions to prevent GVHD have emerged as a major objective of research in the immunology and transplantation fields. A better understanding of the pathobiology behind the GVHD process has led the way to novel approaches and medications. Here we review the present arsenal of medications used to prevent GVHD, focusing on the past experience and the current evidence, and discussing future potential targets.

Keywords: GVHD, allogeneic transplantation, prophylaxis

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is an important therapeutic option for a variety of Hematological disorders. The therapeutic potential of allogeneic HCT relies on the graft-versus-leukemia effect, which eradicates malignant cells by immunologic mechanisms [1]; However, graft versus host disease (GVHD) remains the most frequent and serious complication following allogeneic HCT and limits the broader application of this important modality. Up to 80% of the patients given HLA-identical allografts will develop acute GVHD [2], while 50% will develop clinically significant (grade 2–4) acute GVHD [3]. The incidence is slightly lower in patients given a reduced intensity conditioning [4]. Severe acute GVHD occurs in up to 20% of patients given allografts derived from related donors [3]. GVHD can be quite effectively prevented by graft manipulation, particularly in vitro and in vivo T-cell depletion, but potentially at the cost of an increased risk of relapse and rejection. Other methods to prevent GVHD have also discordant effects on the two important outcome measures, non-relapse mortality and relapse[1, 5]. Thus, a complete abrogation of GVHD can reduce early non-relapse mortality, but it does so at the expense of a higher rate of relapse [6]. Preventing GVHD without interfering with the graft vs. leukemia effect is a major challenge.

Currently there is no standard of care in the prevention of GVHD and indeed a recent survey done by the European Group of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) showed a marked variability between the different transplantation centers in term of GVHD prophylaxis [6]. In this article we aimed to review the current medications commonly used as GVHD prophylaxis, focusing on the rational and on the evidence standing behind the various regimens. Future directions and novel medications based on the increased current understanding of the pathobiology of GVHD will be subsequently discussed.

Overview on GVHD

GVHD results from the detection of host disparate antigen presentation by the donor T-cells. There are several basic steps involve in the pathogenesis - First, the preparative conditioning causes tissue damage and the release of numerous cytokines which in term activates host antigen presenting cells. These cells stimulate the donor’s T cells (first signal) that promote the costimulation of different molecules with their associated ligands on the antigen presenting cells (second signal). The result of these processes is a robust proliferation of the T cells (third signal), migration of the effector T cells to different target tissues and further activation of other leukocytes subsets. The destruction of the cells in the target tissues further amplifies this process.

GVHD has been firstly described during the early attempts to use allografts in the late 1950s. In those patients in whom engraftment was achieved, diarrhea and skin rash developed. This syndrome was named the secondary syndrome (to distinguish it from the primary disease caused by the conditioning regimens) [7]. In the initial studies in the dog model, it was shown that the degree of the lymphocytotoxic antihero matching between canine littermate donor-recipient pairs was predictive for early mortality from GVHD [8, 9]. Further observation of matched dogs showed subsequent development of fatal sub-acute GVHD or chronic GVHD in majority of the recipients. This was likely due to minor histocompatibility antigen disparities and emphasized the need, even in a presumed “compatible” setting, for post-grafting immunosuppression [10]. The first attempts to utilize methotrexate in the canine model, starting on the day of transplantation and continued up to 100 days, essentially controlled GVHD and most dogs achieved prolonged survival [11]. Attempts to use daily cyclophosphamide and other alkylating agents instead of methotrexate failed [12]. These preliminary results of utilizing post grafting immunosupression paved the way for the incorporation of methotrexate as part of the standard protocols [13–15].

Numerous factors have been recognized to be associated with increased incidence or severity of acute GVHD. HLA disparity between the hematopoietic cell donor and recipient is the most important factor for severity and kinetics of GVHD occurrence. In the HLA-identical setting, the minor histocompatibility antigen disparity plays an important role in the initiation of GVHD[16]. Age, of both the patient and donor, has been reported as another factor associated with the development of GVHD[17]. The source of allogeneic hematopoietic cells may also impact the development of GVHD. Recipients of peripheral blood stem cell grafts, compared to bone marrow grafts, may have a higher incidence of chronic GVHD [18]. A higher infused CD34 cell dose (>6.3x106/kg) was also found to be associated with a higher incidence of GVHD [19], although this finding has not been universal. A recent study comparing risk factor profiles for acute and chronic GVHD found that mismatch and unrelated donor grafts had a greater effect on the risk of acute GVHD than on chronic GVHD[20]. Conversely allografts derived from female donors to male-recipents had a greater effect on the risk of chronic GVHD than on acute GVHD. Total body irradiation was strongly associated only with acute GVHD, while grafting with mobilized blood cells and older patient age were both strongly associated only with chronic GVHD. Importantly, the above mentioned risk factors associated with chronic GVHD remained statistically significant even after, adjustment for prior acute GVHD. Several gut and systemic pathogens have been also found to be associated with higher incidence of acute GVHD [21–23]. The diagnosis of acute GVHD relies almost entirely on the presence of clinical symptoms and, preferably, also on typical histopathological findings in the involved target organs. In the last several years, many groups have focused on identifying serum markers that can both predict the onset of GVHD as well as the prognosis and severity of GVHD. Examples for the serum markers include serum C reactive protein, serum albumin, IL-2 receptor, IL-6, HGF, etc. (reviewed in [24]).

Prevention of Acute GVHD

There is no unanimity in the transplantation community with regard to a standard regimen recommended for the prophylaxis GVHD. A recent survey of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) concluded that there was a marked variability between the different centers in the general prophylaxis regimens for GVHD [6]. However, in patients given myeloablative conditioning, the majority of centers used the combination of cyclosporine and a short course of methotrexate.

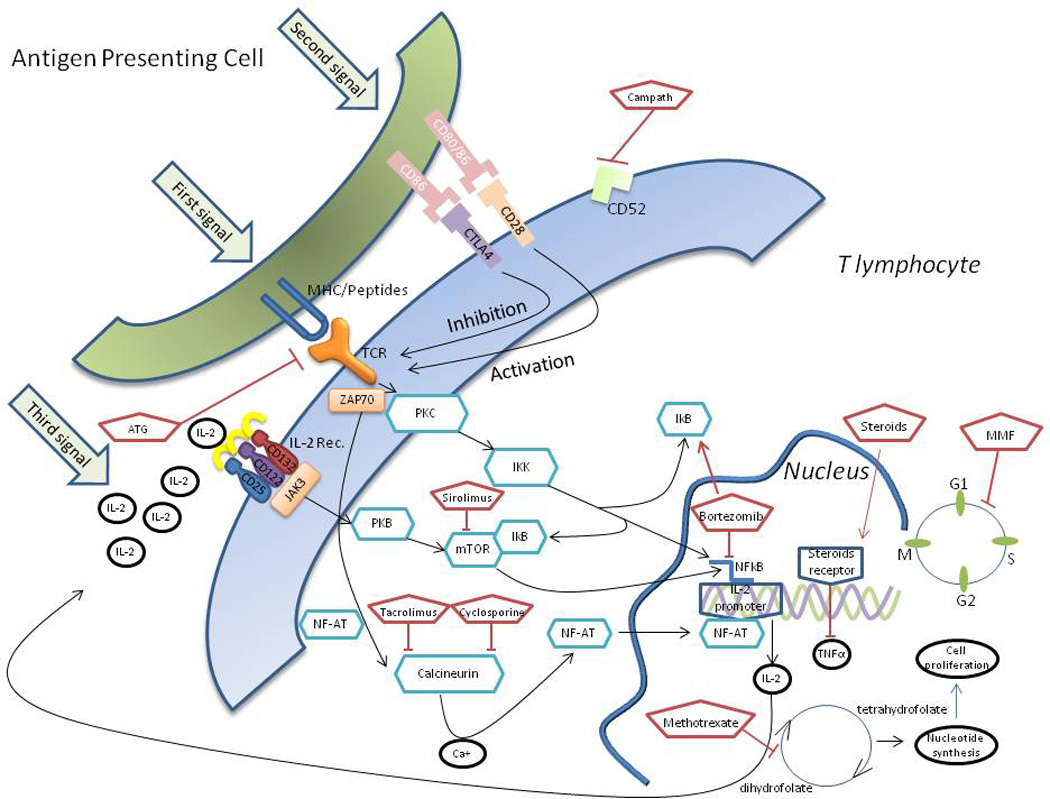

In the following paragraphs we will focus on the main drugs given today for GVHD prophylaxis. Figure 1 depicts the common medications used and their targets. Table 1 shows the common various regimens used for these drugs, as well as their way of action and the major side effects..

Figure 1.

Common medications used and their targets in pathways of GVHD

Table 1.

Some common GVHD prophylaxis medications with associated regimens and their way of action

| Drug | Common regimen | Way of action | Major side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steroids | Methylprednisolone or prednisone 1–2 mg/kg/d | Binding to cytosolic receptor, translocation into nucleus and activating glucocorticoid response elements that regulates certain messenger RNA expression. By this, steroids have a direct lymphocytotoxic effect and down regulation of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF α) | Hyperglycemia, hypertension, cataract, osteoporosis, high incidence of bacterial infections. |

| Methotrexate | Day +1 IV 15 mg/m2, +3 and +6 IV 10 mg/m2. In some institutes also +11 IV 10 mg/m2. Adjust dose to creatinine andbilirubin | Inhibits cellular growth and division, thus the proliferation of antigen activating T cells is inhibited. The cytotoxic effect is by inhibiting dihydrofolate reductaseand by this it inhibits purine and thymidylate synthesis | Delayed hematologic recovery, nephrotoxicity, hapetic toxicity, gastrointestinal mucosal toxicity. |

| Cyclosporine | A loading IV dose of 3–5 mg/kg/d starting on day -3 to day -1. Adjust dose according to blood concentrations. Switch to PO form when the patient s able to tolerate food. | Block the calcium dependent signal transduction pathway downstream to the T cell receptor and consequently inhibits the production of IL-2 | Renal insufficiency, elevation of bilirubin levels, hypertension, hirsutism, headaches, hyperglycemia |

| Tacrolimus | A loading IV dose of 0.02 mg/kg/d starting on day -3 to day -1. Adjust dose according to blood concentrations. Switch to PO form when the patient s able to tolerate food. | Block the calcium dependent signal transduction pathway downstream to the T cell receptor and consequently inhibits the production of IL-2 | Renal insufficiency, elevation of bilirubin levels, hypertension, hyperglycemia, neurotoxicity |

| Sirolimus | A loading PO dose of 12 mg on day -3. Adjust dose according to blood concentrations | Specific inhibition of the progression of cells from G1 to the S phase and preventing part of the secondary signals via the CD28-mediated pathway | Elevation of liver enzymes test, diarrhea, hypertriglyceridemia, thrombocytopenia |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Start after cell infusion at 2–3 grams daily. | Direct inhibition of lymphocytes proliferation through a relative specific intra cellular purine depletion pathway | Thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, high incidence of viral infections, gastrointestinal upset |

| Anti thymocyte globulin | During preparative regimen, given in various dosages | In vivo depletion of T lymphocytes | Infusion-related events, high incidence of infections, mainly virals |

| Alemtuzumab |

Methotrexate

Methotrexate is an analog of aminopterin, the folic acid antagonist. The precise mechanism by which methotrexate prevents GVHD is not understood; however it is likely related to the drug’s antiproliferative functions. Therefore, antigen activated T-cells that are rapidly proliferating, would be particularly sensitive to this antimetabolite. Early results in animal models showed that methotrexate had a potential in preventing GVHD [11, 25, 26]. Thereafter, monotherapy with methotrexate was used as the standard GVHD prophylaxis in humans with the best results achieved when given the first dose at least 24 hours after hematopoietic cell infusion and when spacing additional doses of methotrexate in order to decrease the associated gastrointestinal toxicity [27, 28]; However GVHD incidence and severity were relatively high and only later, with the addition of cyclosporine to the methotrexate regimen, results of GVHD prophylaxis, have significantly improved.

The main concern with the administration of methotrexate is its side effects, mainly in the form of hepatic, renal and mucous membrane toxicities. These toxicities mandate dose reductions in some patients. Completely holding the dose of methotrexate is suggested in cases of bilirubin >5 mg/dL or creatinine >2 mg/dL. Indeed, 2 large randomized trials showed that only two thirds of the patients are given the full methotrexate total dose [29, 30]. The effect of methotrexate dose reduction in patients given the methotrexate-cyclosporine prophyalxis regimen was analyzed by the Seattle group [31]. Among patients receiving a reduced dose of methotrexate on day 6, 16% developed early acute GVHD with the onset between days 7 and 11, whereas only 6% of those administered at least 80% of the protocol dose developed acute GVHD during that time period (P = .003). Beyond day 11, the risk was similar in both cohorts. Similar results were demonstrated regarding the day 11 dose. There was no significant effect of day 6 or 11 of methotrexate on the incidence of grade 3–4 acute GVHD [31]. A Canadian study found similar trends and showed that survival at 3 months in patients with optimal GVHD prophylaxis was superior to patients with suboptimal GVHD control [32]. The survival advantage was attributed to a lower incidence of early deaths from acute GVHD and infectious episodes.

A recent EBMT survey found that four doses of methotrexate, 15 mg/m2 on day +1 and 10 mg/m2 on days +3, +6 and +11, combined with a calcineurin inhibitor, were administered in 61% of the participating centers, and 3 sequential doses, in 24% of the centers [6]. Folinic acid rescue after methotrexate administration was given in 49% of the centers. The doses and timing of folinic acid rescue were highly variable. A recent study suggested, however, inferior survival of patients given folinic acid and allografts from donors exhibiting a specific (1298AC) methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphisms [33]. Oral cryotherapy has not shown to benefit patients in term of mucositis prevention [34].

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine, a calcineurin inhibitor, was extracted in the late 1960s from fungi and was initially tested as an antifungal medication showing only modest efficacy. It was first used as a treatment for GVHD in the late 1970s [35]. The main action of cyclosporine is to block the calcium dependent signal transduction downstream to the T-cell receptor activation. This results in inhibition of the IL-2 gene activation. Cyclosporine has numerous metabolites that play a central role in the clinical efficacy and interactions between cyclosporine and other drugs. After the initial observations showing cyclosporine could be incorporate as an immunosuppressive drug, non randomized trials of GVHD prevention suggested cyclosporine to be more efficacious when compared to the standard methotrexate regimen [36]. This was partially confirmed in a randomized controlled trial comparing a dose of 1.5 mg/kg of cyclosporine twice daily, started from day -1 to methotrexate 15 mg/rn2 IV on day 1 and 10 mg/rn2 on days 3, 6, 11, 18, and 25, and then every two weeks until day 95 [37]. A subsequent study, showed a comparable incidence of GVHD among patients given methotrexate and cyclosporine [38]. The question when before transplant cyclosporine should be initiated was studied by Barrett et al. They showed that there was no benefit in GVHD prevention when cyclosporine was started before day -1 (e.g. at -4); however, beginning the cyclosporine taper on day 100 was better than beginning the taper on day 50 [39]. The addition of cyclosporine to methotrexate was first tested in the canine model and showed benefit in term of engraftment and GVHD prevention [40]. In this study, several GVHD prophylaxis regimens were tested and of the various regimens, the only long term survivors were among dogs given methotrexate on days 1, 3, 6 and 11 and cyclosporine from days 0 through 100. This observation paved the way for two pivotal randomized controlled trials comparing the cyclosporine-methotrexate combination to either cyclosporine or methotrexate alone [41, 42]. These studies showed that patients given monotherapy with either methotrexate or cyclosporine were at significantly higher risk of developing acute GVHD than patients given the two drugs combined. Both studies showed improved survival among patients given the drug combination, with follow-up of >20 years after transplantation[43, 44]. Since these studies were reported, 5 other phase 3 clinical studies were published that tested the addition of MTX to a cyclosporine containing regimens. A meta-analysis, summarizing the results of these studies, showed that the combination of methotrexate and cyclosporine significantly decreased the incidence of acute GVHD (Relative risk=0.49, 95% confidence interval=0.38–0.65), however with no statistically significant impact on overall survival [45].

In an EBMT survey, the typical duration of cyclosporine prophylaxis reported by different centers was 6 months (42% of the centers), with a majority of the centers adjusting the duration of prophylaxis based on the estimated relapse risk of the underlying diseases [6].

As opposed to methotrexate, cyclosporine dosing is typically adjusted both to maintain whole blood concentrations within a therapeutic range in order to avoid toxicities, especially renal [46]. Early studies in the myeloablative setting showed that higher doses of cyclosporine were associated with decreased incidence of acute GVHD albeit with increased incidence of relapse [5]. This phenomenon has been also recently demonstrated in patients given alemtuzumab as in-vivo T-cell depletion strategy followed by reduced intensity conditioning [47]. We have shown, in patients given T-repleted allografts, that in patients given a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, higher cyclosporine concentrations were associated with decreased incidence and severity of acute GVHD as well as decreased non-relapse mortality and overall mortality. No such correlations were found in patients given myeloablative conditioning [48]. This study suggests that in the nonmyeloablative setting, cyclosporine concentrations above 345 ng/mL provide incremental protection against grades 2–4 and grades 3–4 GVHD. Importantly, higher cyclosporine levels were not associated with increased risk of renal dysfunction [48]. Normally, in patients not experiencing acute GVHD we suggest slow tapering of cyclosporine starting at 3 months post transplantation and completely discontinuation of the medication at 6 months post transplantation. In this group of GVHD naiive patients, early discontinuation of cyclosporine has been shown to be associated with lower incidence of early relapse [49]. Individualizing the tapering schedule is necessary in cases GVHD occurs during the tapering off period.

Tacrolimus

Tacrolimus (FK506) is a macrolide lactone discovered in 1984 from the fermentation of Streptomyces tsukubensis [50]. Tacrolimus has potent inhibitory effects on T cell activation through down-regulation of IL-2 gene expression [51]. It binds to an immunophilin, FKbinding protein (FK-BP12), to form a complex which inhibits the phosphatase activity of calcineurin [52]. Inhibition of calcineurin directly blocks the translocation of a nuclear transcription factor (NFAT) essential for IL-2 gene expression. Tacrolimus was first introduced and tested in the prevention and treatment of graft rejection in solid organ transplantation [53]. The efficacy of tacrolimus for the prevention of acute GVHD was first shown in both canine and murine models [54, 55] and subsequently in several human phase 2 trials [56, 57].

Although tacrolimus binds to an immunophilin similar to cyclosporine, its immunosuppressive activity is 50- to 100 times higher that of cyclosporine. While tacrolimus abrogates the conversion of precursor helper T lymphocytes to activated helper T lymphocytes, cyclosporine at 20-fold higher concentration failed to exert this effect [51]; However this does not necessarily translate into improved clinical results, and there is an ongoing debate in the scientific community whether the two calcineurin drugs are comparable or tacrolimus is superior to cyclosporine. So far, 3 randomized controlled trials have been published and showed heterogeneous results [29, 30, 58]. A meta analysis summarizing those 3 studies showed comparable overall mortality when tacrolimus was compared to cyclosporine, however a lower incidence of grade 3–4 acute GVHD in patients given tacrolimus [45]. A recent large retrospective study, nevertheless, showed comparable outcomes between the two calcineurin inhibitors [59]. Similar to cyclosporine, high tactolimus blood concentrations were correlated with a lower incidence of grade 3–4 acute GVHD in the nonmyeloablative setting, while no correlation was found in patients given myeloablative preparative regimen [48].

Corticosteroids

The utility of corticosteroids in GVHD is thought to be related to their lympholytic activity [60]. They also decrease the levels of a number of cytokines associated with inflammation and when used for the therapy of GVHD, suppress the levels of TNF-α [61]. Steroids have been mainly used for the treatment of acute GVHD, rather than prophyalaxis.

Deeg et al. showed that the addition of steroids to cyclosporine as GVHD prophylaxis significantly decreased the overall incidence of GVHD, however with no effect on the incidence of grade 3–4 acute GVHD nor on survival [62]. Another study suggested that in patients given methotrexate and cyclosporine, the addition of steroids increased the incidence of GVHD, presumably because of interference with the immunosuppressive effect of methotrexate [63]. A meta analysis, summarizing 5 randmoized controlled trials (all in patients given myeloablative conditioning) [64] showed that the addition of corticosteroids to the GVHD prophylaxis regimen significantly decreased the incidence of acute GVHD; However, according to the recent EBMT survey only minority of the centers (7%) included corticosteroid in the prophylaxis regimen [6], this might be due to the steroid-induced profound immunosupression and the higher incidence of infections associated with the use of corticosteroids [65].

Mycophenolate Mofetil

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) inhibits the proliferation of T and B cells and the production of antibodies [66]. Its main action is through the inhibition of the de novo purine metabolism, which is essential to lymphocytes proliferation.

The early HCT studies in the late 1990s, showed the effectiveness of the combination of cyclosporine and MMF after nonmyeloablative conditioning in the canine model. MMF and cyclosporine were also effective in preventing acute GVHD in dogs [67]. Thereafter, MMF has been largely employed mainly for patients given either reduced intensity or nonmyeloablative conditioning [68]. In fact, in patients given reduced intensity conditioning, according to an EBMT survey, the most common GVHD prophylaxis regimen in 69% of the centers was a combination of a calcineurin inhibitor with MMF [6]. In the cord blood setting, 58% of the centres used an MMF-based regimen. Most centers administer MMF for durations of 4 weeks to 3 months. The MMF dose was calculated in different ways, but the total dose was usually between 1 and 3 g per day. Most centers used fixed doses and not doses based on MMF levels. Of note, higher blood concentrations of MMF were found to be associated with less graft rejection, however with no effect on the incidence of GVHD [69].

Three prospective trials compared MMF to methotrexate (both in combination with a calcineurin inhibitor) and all reported a similar overall incidence of acute GVHD with both regimens [70–72], however in one of the studied the incidence of grade 3–4 GVHD was higher in patients given MMF [70]. Other non randomized trials showed conflicting results regarding severe acute GVHD [73, 74]. Thus, it is difficult to draw a conclusion whether MMF is comparable to methotrexate. Well designed clinical trials comparing MMF and methotrexate in different setting of transplantation (myeloablative and reduced intensity regimens) are needed to identify which group of patients will benefit the most from MMF.

Anti thymocyte globulin (ATG)

The role of antithymocyte globulin (ATG) in preventing acute GVHD has been explored in the past decades and is still controversial. Based on canine studies, the Seattle group has pioneered the use of ATG to treat acute GVHD in the early 1970s [75]. They postulated that ATG might exert its immunomudulatory function primarily by in vivo depletion of T-lymphocytes. In their study batches of ATG were produced in rabbits and goats by injecting thymocytes obtained from children undergoing open-heart surgery [75]. The immunosuppressive effect of each ATG batch was tested in rhesus monkeys given skin grafts from unrelated donors. Twelve of the 19 patients with GVHD had significant improvement in their condition and, for the first time, patients with established severe GVHD achieved long-term survival. Today there are 3 main different sources of ATG, (a) horse ATG, namely Atgam (Pharmacia & Upjohn Company, Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) and (b) two types of rabbit ATG, namely Thymoglobulin (Genzyme Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA) and ATG-Fresenius (ATG-F; Fresenius Biothech, Graefelfing, Germany).

The first randomized controlled trial showed that the incorporation of rabbit-ATG in the standard GVHD prophylaxis regimen significantly decreased the incidence of grade 3–4 acute GVHD, however with no change in the incidence of non-relapse mortality due to a higher rate of infections probably because of a delay in T-cell recovery [76]. Another randomized controlled trial showed that patients given ATG-F after myeloablative conditioning and unrelated donor grafts had reduce incidence of both acute chronic GVHD, compared to patients no given ATG, with no impact on the relapse risk [77, 78]. A recent published meta-analysis analyzing 6 clinical trials suggested that ATG reduced the incidence of grade 3–4 acute GVHD, however without an impact on overall survival [79]. In this meta-analysis there was also no increase in relapse risk in patients given ATG.

Of note, a recent trial examining the impact of the different ATG products given as part of the preparative regimen, suggested that the efficacy in GVHD prevention depends on the source of the ATG [80]. Importantly, this study showed that rabbit ATG was more protective than horse ATG in term of grade 2–4 acute GVHD and chronic GVHD, however this was counterbalanced by a higher incidence of infections and increased incidence of mixed chimersim with the net result of similar overall survival. Conversely, in the non transplant setting of treatment, patients with aplastic anemia given horse ATG had superior hematologic response and overall survival, compared to patients given rabbit ATG [81, 82]. This is a very important point and we suggest caution when basing recommendations for use of one ATG on studies performed with another ATG. Moreover, in patients given reduced intensity conditioning, in which the success of the transplantation relies on antitumor alloreactivity, ATG might significantly hinder such an effect. This was shown in a large retrospective trial published by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) showing that in patients given reduced intensity conditioning, grade II-IV acute GVHD was not impacted by ATG (38% versus 40%), however, relapse was more frequent with ATG compared with T cell–replete regimens (51% versus 38%, respectively, P <.001) [83].

Nevertheless, 75% of the EBMT centers reported that ATG was included in the routine prophylaxis for recipients of grafts from unrelated donors [6]. Most (45%) of the centers used Thymoglobulin. The median total dose of Thymoglobulin was 7.5 mg/kg (range, 4-- 32 mg/kg), given over 2–4 days between days -8 and -1. The most commonly used total doses of ATG-F were 30 mg/kg (30%) (range, 1.5 –75 mg/kg). The infusions were mostly given over 3 days (68%, range 1--5 days), between days -5 and -1. Of note, higher doses of ATG were associated with reduced incidence of grade 3–4 acute GVHD when compared to lower doses [84].

We suggest utilizing ATG as part of the preparative regimen in patients with nonmalignant diseases. Patients with malignant diseases given reduced intensity conditioning preferably should not be given ATG outside of a clinical study. In patients given myeloablative conditioning randomized trials with longer follow up are needed to demonstrate whether the lower incidence of GVHD translates into better overall survival.

Sirolimus

Sirolimus is a lipophilic macrocytic lactone which is successfully used for the prevention of solid organ graft rejection [85]. It is presumed that sirolimus inhibits cytotoxic T-cells while the CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T-cells (T-regs), a T cell population involved in the graft vs. leukemia effect, remain intact. Sirolimus also inhibits antigen presentation and dendritic cell maturation [86]. Sirolimus binds to the family of intracellular FK-506 binding proteins (FKBP) but at a distinct site. It forms complexes that inhibit the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a protein kinase that regulates mRNA translation and protein synthesis, which is an essential step in cell division and proliferation. It also inhibits cell cycle entry in response to interleukin-2 (IL-2), leading to T-cell apoptosis [86, 87]. In a phase 2 study, the overall incidence of grade 3–4 acute GVHD in patients given GVHD prophylaxis regimen consisted on sirolimus and tacrolimus was only 4.8% [88]. Rossenback et al. compared treatment with sirolimus and tacrolimus to historical patients given CNI and methotrexate [89]. The incidences of overall GVHD and of severe acute GVHD were lower in patients given sirolimus tacrolimus (18.6% vs. 48.9%, p=.001 and 5.1% vs. 17% p=.45, respectively). The reduction in acute GVHD incidence in the sirolimus group was offset by the high rates of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome and viral infection, resulting in no significant survival difference. A prospective randomized study comparing sirolimus-tacrolimus and methotrexate-tacrolimus showed a statistically significant decrease in the overall incidence of GVHD in patients given sirolimus (43% vs, 89%, p<.0001), while grade 3–4 were comparable (16% vs. 13%, p=.16) [90]. The fact that sirolimus, in addition to its role in GVHD prophylaxis, might also have a specific anti lymphoma activity, merit further evaluation of this drug in the transplantation field [91]. A smaller prospective trial failed to show superiority of a regimen containing sirolimus, methotrexate and a calcineurin inhibitor, over regimen containing only methotrexate and a calcineurin inhibitor [92]. Additional prospective randomized trials are needed to further investigate if sirolimus is superior to other common used GVHD prophylaxis combinations, specifically in lymphoma patients.

Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody of the IgG1 subtype that is directed against the human CD52 antigen, presented on the surface of both B and T lymphocytes. Following cell surface binding of alemtuzumab , the antibody exhibits cytotoxicity via antibody-dependent cellular-mediated lysis. Alemtuzumab was initially developed as a T-cell depleting agent, and earlier studies have demonstrated considerable efficacy in preventing both GVHD and graft rejection in patients undergoing HCT [93, 94]. In single-arm studies alemtuzumab has been shown to prevent both acute and chronic GVHD, although some of these studies have also shown an increased risk of relapse. Comparing to other regimens given for GVHD prophylaxis in patients given reduced intensity conditioning, the incidence of grade 2–4 acute GVHD was only 10 to 20% with a similar non relapse mortality [95, 96]. A recent EBMT analysis suggested that T cell depletion with alemtuzumab, though decreasing the incidence of chronic extensive GVHD was associated with an inferior survival (HR=0.65; P=0.001) [6]. An exception is the group of patients with aplastic anemia, in which the incorporation of alemtuzumab to the conditioning regimen has almost completely ameliorated GVHD [97] with also a very low incidence of acute GVHD. In this group, as well as in other non-malignant hematologic diseases, in which patients do not benefit from chronic GVHD and its correlation with a lower relapse rate, alemtuzumab is an attractive option. The second group who might benefit from alemtuzumab is of patients allografts from a mismatch donor. In this group alemtuzumab may overcome the disparity associated toxicity and may be a reasonable option in this setting [98].

Cyclophosphamide

The Johns Hopkins group [99] developed a novel approach of GVHD prophylaxis with high-dose cyclophosphamide given on days 3 and 4 after HCT at a dose of 50 mg/kg/day, based on the drug’s effectiveness against activated donor T cells. In this study bone marrow allografts were administered with cyclophosphamide as sole posttransplant prophylaxis. Only 10% of the patients developed grade 3–4 acute GVHD. Similar results in patients given HLA-hapolidentical bone marrow grafts were reported by an Italian group and a Johns Hopkins/Seattle consortium [100, 101].

Future potential targets

In contrast to the typical medications summarized above, novel strategies and treatments are based on our growing knowledge on the pathobiologic pathways of acute GVHD [1]. There are several major players in this process - the first are the antigen presenting cells. The second are the effectors, or alloreactive donor T cells and their cytotoxic responses against the tissues and organs of the recipients. The third are the mediators – these are cell surface and secreted factors that initiate and propagate the GVHD process.

Agents that target the antigen presenting cells (B cells)

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody specific against the CD20 receptor. It has been suggested that rituximab reduced the incidence and severity of acute GVHD when incorporated to the preparative regimen prior to transplant [102]. A small retrospective study showed that patients given rituximab up to 3 months before transplantation had lower incidences of both grade 2–4 and grade 3–4 acute GVHD [103]. Other drugs that target the maturation of the B cell are currently being investigated in autoimmune diseases, e.g., the BAFF-specific antibody belimumab and the germinal-center differentiation blocker baminsercept, These agents may enter clinical studies in the future.

Agents that target subsets of T cells

Both donor CD4+ and donor CD8+ T cells have crucial roles in the pathogenesis of GVHD, mainly the naive T cells. The CD4+ T cells are able to differentiate into several subclasses, namely TH1 TH2 and TH 17, and all of these have different roles in the GVHD pathogenesis. So far attempts to target the TH1 and TH2 cells and the corresponding cytokines have failed to result in conclusive and reproducible prevention of GVHD. In the last several years TH 17 and the associated cytokines have been investigated as potential targets [104]. Although there is evidence that these cells have a major role, they are not required for the induction of GVHD [105, 106]. A variety of specific antibodies targeting T cells (e.g. anti CD3, anti IL6 receptor and anti CD7) are currently investigated both for the prevention and the treatment of GVHD.

Natural Treg cells — which are defined by their expression of CD4, CD25 and the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) — suppress autoreactive lymphocytes and control innate and adaptive immune responses [107, 108]. The cytokine IL-2 has a crucial role in the proliferation of Treg cells and the effector T cells. It has been shown that sirolimus synergize with IL-2 and results in improved survival and a reduction in acute GVHD severity with a decreased production of IFN-γ and TNF [109]. Azacitidine, a hypomethylating agent, was shown to increase the number of Tregs within the first 3 months after transplantation when administered monthly to patients given reduced intensity conditioning [110, 111]. Interesetingly, azacitidine administration also induced a cytotoxic CD8(+) T-cell response to several tumor peptides [111]. Thus, it might serve as a GVHD prophylactic agent that preserves, or even enhances, the graft vs. leukemia activity. Future trials should further investigate azacitidine in the as both GVHD prophylaxis and prevention of post transplantation leukemia relapse, specifically in patients with high risk disease.

Agents that target costimulatory molecules

The major role of the costimulation pathways is to propagate the T cell responses [112]. As such, these pathways induce T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion. The most extensively studied pathways involve interactions between CD28 (and the associate cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4, CTLA-4) and the B7 molecules, CD80 and CD86. Signals through CTLA-4 counteract the CD28-B7 stimulation pathway by inhibiting T-cell alloreactivity. Once T-cells are activated, CTLA-4 is upregulated and binds to B7 proteins (CD80 and CD86) with higher affinity than CD28, therefore resulting in inhibition of T-cell activation [113]. Thus, there is a complex relationship between these molecules. One murine study showed that complete blocking of this pathway was associated with shortening of Treg cell survival thus compromising tolerance and the net effect was an increase in the incidence and severity of acute GVHD [114]. In another murine GVHD study, brief treatment with CTLA4Ig prolonged recipient survival [115]. Two murine HCT studies using grafts from CD28−/− donors gave contradictory results, which were attributed to different strain combinations used in the respective studies[116, 117]. A canine study in DLA-nonidentical CTLA4Ig-treated recipients showed modest improvement in survival over controls[118]. Current efforts focus in the selective inhibition of the CD28-B7 pathway with only mild effect on CTLA4 function [119]. Other co-stimulatory molecules whose inhibition might be associated with modulation of GVHD are CD40 and the TNF family molecules.

Agents that target T cell signal transduction

T-cell Signal transduction pathways are attractive targets for prevention of GVHD. The Janus kinase (JAKs) family initiates cytokine-triggered signaling events by activating the STAT proteins. Results of JAK2 inhibition in vitro suggest potential benefit for decreasing GVHD [120]. Proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib, have inhibitory effects on cytokine signaling and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation. Bortezomib, even at very low doses, can specifically deplete alloreactive T cells, promote Treg cells survival and attenuate IL-6-mediated T cell differentiation [121]. Bortezomib also affects the antigen-presenting cell activity. Interestingly, administration of bortezomib early in course of HCT prevents GVHD, while it exacerbates GVHD when administered later after HCT [121, 122]. Histone deacetilase inhibitors have been shown in preclinical models to negatively regulate the antigen presenting cells (mainly dendritic cells), reduce the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, increase the numbers and function of Tregs, and activate NK cell–mediated activity [123, 124]. This has led to a clinical trial that preliminarily demonstrated abrogation of grade 3–4 acute GVHD [125].

Agents that target cytokines

Several cytokines have been associated with GVHD initiation and propagation, IL-2, as shown in Figure 1 has a major role in the signal propagating GVHD. Basiliximab and daclizumab are IL-2 receptor antagonists that prevent graft failure in renal transplantation. Preliminary results show these drugs have a role in GVHD prevention [126], however prospective trials are needed to confirm their safety, as IL-receptor is also expressed in regulatory T cells. Higher serum Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) α level are typically found in patients developing GVHD, Infliximab and etanercept are 2 monoclonal antibodies that showed remarkable efficacy in inflammatory bowel diseases and in rheumatoid arthritis. However when tested in prospective trials The addition of the TNFα monoclonal antibodies showed conflicting results in term of GVHD prevention, but was associated with an increased risk of bacterial and invasive fungal infections [127, 128]. Additional studies are needed to define which subgroup of patients might benefit, if at all, from TNF α monoclonal antibodies [128]. Blockade of other monoclonal antibodies, like IL-1 and IL-6, have been studied in the past, however results were suboptimal. It is reasonable to believe that blockade of GVHD-associated cytokines will potential decrease the propagation of GVHD, however this might also hamper the graft vs leukemia effect and the development of tolerance.

Summary

Despite advanced both in immunosuppressive agents and in the understanding of the immunobiology of GVHD, graft-vs.-host disease can occur after allogeneic HCT. In the future, we would like to see targeted interventions that prevent the tissue injuries that are clinically recognized as GVHD while not preventing graft-vs.-tumor effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD grants CA 78902, CA 18029 and CA 15704.

Bibliography

- 1.Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E. Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet. 2009;373:1550–1561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60237-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolfrey A, Lee SJ, Gooley TA, Malkki M, Martin PJ, Pagel JM, Hansen JA, Petersdorf E. HLA-allele matched unrelated donors compared to HLA-matched sibling donors: role of cell source and disease risk category. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:1382–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Champlin RE, Schmitz N, Horowitz MM, Chapuis B, Chopra R, Cornelissen JJ, Gale RP, Goldman JM, Loberiza FR, Jr, Hertenstein B, et al. Blood stem cells compared with bone marrow as a source of hematopoietic cells for allogeneic transplantation. IBMTR Histocompatibility and Stem Cell Sources Working Committee and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Blood. 2000;95:3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mielcarek M, Martin PJ, Leisenring W, Flowers ME, Maloney DG, Sandmaier BM, Maris MB, Storb R. Graft-versus-host disease after nonmyeloablative versus conventional hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;102:756–762. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacigalupo A, Van Lint MT, Occhini D, Gualandi F, Lamparelli T, Sogno G, Tedone E, Frassoni F, Tong J, Marmont AM. Increased risk of leukemia relapse with high-dose cyclosporine A after allogeneic marrow transplantation for acute leukemia. Blood. 1991;77:1423–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruutu T, van Biezen A, Hertenstein B, Henseler A, Garderet L, Passweg J, Mohty M, Sureda A, Niederwieser D, Gratwohl A, et al. Prophylaxis and treatment of GVHD after allogeneic haematopoietic SCT: a survey of centre strategies by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.45. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathe G, Amiel JL, Schwarzenberg L, Cattan A, Schneider M. Haematopoietic Chimera in Man after Allogenic (Homologous) Bone-Marrow Transplantation. (Control of the Secondary Syndrome. Specific Tolerance Due to the Chimerism) Br Med J. 1963;2:1633–1635. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5373.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein RB, Storb R, Ragde H, Thomas ED. Cytotoxic typing antisera for marrow grafting in littermate dogs. Transplantation. 1968;6:45–58. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196801000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storb R, Epstein RB, Bryant J, Ragde H, Thomas ED. Marrow grafts by combined marrow and leukocyte infusions in unrelated dogs selected by histocompatibility typing. Transplantation. 1968;6:587–593. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196807000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storb R, Rudolph RH, Thomas ED. Marrow grafts between canine siblings matched by serotyping and mixed leukocyte culture. J Clin Invest. 1971;50:1272–1275. doi: 10.1172/JCI106605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storb R, Epstein RB, Graham TC, Thomas ED. Methotrexate regimens for control of graft-versus-host disease in dogs with allogeneic marrow grafts. Transplantation. 1970;9:240–246. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storb R, Graham TC, Shiurba R, Thomas ED. Treatment of canine graft-versus-host disease with methotrexate and cyclo-phosphamide following bone marrow transplantation from histoincompatible donors. Transplantation. 1970;10:165–172. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathe G, Amiel JL, Schwarzenberg L, Choay J, Trolard P, Schneider M, Hayat M, Schlumberger JR, Jasmin C. Bone marrow graft in man after conditioning by antilymphocytic serum. Br Med J. 1970;2:131–136. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5702.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckner CD, Epstein RB, Rudolph RH, Clift RA, Storb R, Thomas ED. Allogeneic marrow engraftment following whole body irradiation in a patient with leukemia. Blood. 1970;35:741–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas ED, Buckner CD, Rudolph RH, Fefer A, Storb R, Neiman PE, Bryant JI, Chard RL, Clift RA, Epstein RB, et al. Allogeneic marrow grafting for hematologic malignancy using HL-A matched donor-recipient sibling pairs. Blood. 1971;38:267–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.den Haan JM, Sherman NE, Blokland E, Huczko E, Koning F, Drijfhout JW, Skipper J, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH, et al. Identification of a graft versus host disease-associated human minor histocompatibility antigen. Science. 1995;268:1476–1480. doi: 10.1126/science.7539551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisdorf D, Hakke R, Blazar B, Miller W, McGlave P, Ramsay N, Kersey J, Filipovich A. Risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease in histocompatible donor bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1991;51:1197–1203. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199106000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cutler C, Giri S, Jeyapalan S, Paniagua D, Viswanathan A, Antin JH. Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic peripheral-blood stem-cell and bone marrow transplantation: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3685–3691. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Przepiorka D, Smith TL, Folloder J, Khouri I, Ueno NT, Mehra R, Korbling M, Huh YO, Giralt S, Gajewski J, et al. Risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1999;94:1465–1470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flowers ME, Inamoto Y, Carpenter PA, Lee SJ, Kiem HP, Petersdorf EW, Pereira SE, Nash RA, Mielcarek M, Fero ML, et al. Comparative analysis of risk factors for acute graft-versus-host disease and for chronic graft-versus-host disease according to National Institutes of Health consensus criteria. Blood. 2011;117:3214–3219. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Velden WJ, Netea MG, de Haan AF, Huls GA, Donnelly JP, Blijlevens NM. The role of the mycobiome in human acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonso CD, Treadway SB, Hanna DB, Huff CA, Neofytos D, Carroll KC, Marr KA. Epidemiology and outcomes of Clostridium difficile infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1053–1063. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantoni N, Hirsch HH, Khanna N, Gerull S, Buser A, Bucher C, Halter J, Heim D, Tichelli A, Gratwohl A, et al. Evidence for a bidirectional relationship between cytomegalovirus replication and acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:1309–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paczesny S. Discovery and validation of graft-versus-host disease biomarkers. Blood. 2012 doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-355990. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uphoff DE. Alteration of homograft reaction by A-methopterin in lethally irradiated mice treated with homologous marrow. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1958;99:651–653. doi: 10.3181/00379727-99-24450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lochte HL, Jr, Levy AS, Guenther DM, Thomas ED, Ferrebee JW. Prevention of delayed foreign marrow reaction in lethally irradiated mice by early administration of methotrexate. Nature. 1962;196:1110–1111. doi: 10.1038/1961110a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas E, Storb R, Clift RA, Fefer A, Johnson FL, Neiman PE, Lerner KG, Glucksberg H, Buckner CD. Bone-marrow transplantation (first of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1975;292:832–843. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197504172921605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storb R, Antin JH, Cutler C. Should methotrexate plus calcineurin inhibitors be considered standard of care for prophylaxis of acute graft-versus-host disease? Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:S18–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratanatharathorn V, Nash RA, Przepiorka D, Devine SM, Klein JL, Weisdorf D, Fay JW, Nademanee A, Antin JH, Christiansen NP, et al. Phase III study comparing methotrexate and tacrolimus (prograf, FK506) with methotrexate and cyclosporine for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1998;92:2303–2314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nash RA, Antin JH, Karanes C, Fay JW, Avalos BR, Yeager AM, Przepiorka D, Davies S, Petersen FB, Bartels P, et al. Phase 3 study comparing methotrexate and tacrolimus with methotrexate and cyclosporine for prophylaxis of acute graft-versus-host disease after marrow transplantation from unrelated donors. Blood. 2000;96:2062–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nash RA, Pepe MS, Storb R, Longton G, Pettinger M, Anasetti C, Appelbaum FR, Bowden RA, Deeg HJ, Doney K, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease: analysis of risk factors after allogeneic marrow transplantation and prophylaxis with cyclosporine and methotrexate. Blood. 1992;80:1838–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Bueltzingsloewen A, Belanger R, Perreault C, Bonny Y, Roy DC, Lalonde Y, Boileau J, Kassis J, Lavallee R, Lacombe M, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with methotrexate and cyclosporine after busulfan and cyclophosphamide in patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 1993;81:849–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy NM, Diviney M, Szer J, Bardy P, Grigg A, Hoyt R, King-Kallimanis B, Holdsworth R, McCluskey J, Tait BD. The effect of folinic acid on methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms in methotrexate-treated allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:722–730. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gori E, Arpinati M, Bonifazi F, Errico A, Mega A, Alberani F, Sabbi V, Costazza G, Leanza S, Borrelli C, et al. Cryotherapy in the prevention of oral mucositis in patients receiving low-dose methotrexate following myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a prospective randomized study of the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo nurses group. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:347–352. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powles RL, Barrett AJ, Clink H, Kay HE, Sloane J, McElwain TJ. Cyclosporin A for the treatment of graft-versus-host disease in man. Lancet. 1978;2:1327–1331. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91971-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hows JM, Chipping PM, Fairhead S, Smith J, Baughan A, Gordon-Smith EC. Nephrotoxicity in bone marrow transplant recipients treated with cyclosporin A. Br J Haematol. 1983;54:69–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1983.tb02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deeg HJ, Storb R, Thomas ED, Flournoy N, Kennedy MS, Banaji M, Appelbaum FR, Bensinger WI, Buckner CD, Clift RA, et al. Cyclosporine as prophylaxis for graft-versus-host disease: a randomized study in patients undergoing marrow transplantation for acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1985;65:1325–1334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Storb R, Deeg HJ, Thomas ED, Appelbaum FR, Buckner CD, Cheever MA, Clift RA, Doney KC, Flournoy N, Kennedy MS, et al. Marrow transplantation for chronic myelocytic leukemia: a controlled trial of cyclosporine versus methotrexate for prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1985;66:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrett AJ, Kendra JR, Lucas CF, Joss DV, Joshi R, Pendharkar P, Hugh-Jones K. Cyclosporin A as prophylaxis against graft-versus-host disease in 36 patients. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:162–166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6336.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deeg HJ, Storb R, Weiden PL, Raff RF, Sale GE, Atkinson K, Graham TC, Thomas ED. Cyclosporin A and methotrexate in canine marrow transplantation: engraftment, graft-versus-host disease, and induction of intolerance. Transplantation. 1982;34:30–35. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storb R, Deeg HJ, Whitehead J, Appelbaum F, Beatty P, Bensinger W, Buckner CD, Clift R, Doney K, Farewell V, et al. Methotrexate and cyclosporine compared with cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of acute graft versus host disease after marrow transplantation for leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:729–735. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603203141201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storb R, Deeg HJ, Farewell V, Doney K, Appelbaum F, Beatty P, Bensinger W, Buckner CD, Clift R, Hansen J, et al. Marrow transplantation for severe aplastic anemia: methotrexate alone compared with a combination of methotrexate and cyclosporine for prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1986;68:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sorror ML, Leisenring W, Deeg HJ, Martin PJ, Storb R. Twenty-year follow-up of a controlled trial comparing a combination of methotrexate plus cyclosporine with cyclosporine alone for prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease in patients administered HLA-identical marrow grafts for leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:814–815. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorror ML, Leisenring W, Deeg HJ, Martin PJ, Storb R. Re: Twenty-year follow-up in patients with aplastic anemia given marrow grafts from HLA-identical siblings and randomized to receive methotrexate/cyclosporine or methotrexate alone for prevention of graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:567–568. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ram R, Gafter-Gvili A, Yeshurun M, Paul M, Raanani P, Shpilberg O. Prophylaxis regimens for GVHD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:643–653. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armstrong VW, Oellerich M. New developments in the immunosuppressive drug monitoring of cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and azathioprine. Clin Biochem. 2001;34:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(00)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Craddock C, Nagra S, Peniket A, Brookes C, Buckley L, Nikolousis E, Duncan N, Tauro S, Yin J, Liakopoulou E, et al. Factors predicting long-term survival after T-cell depleted reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2010;95:989–995. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.013920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ram R, Storer B, Mielcarek M, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, Martin PJ, Flowers ME, Chua BK, Rotta M, Storb R. Association between calcineurin inhibitor blood concentrations and outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Inamoto Y, Flowers ME, Lee SJ, Carpenter PA, Warren EH, Deeg HJ, Storb RF, Appelbaum FR, Storer BE, Martin PJ. Influence of immunosuppressive treatment on risk of recurrent malignancy after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:456–463. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kino T, Hatanaka H, Hashimoto M, Nishiyama M, Goto T, Okuhara M, Kohsaka M, Aoki H, Imanaka H. FK-506, a novel immunosuppressant isolated from a Streptomyces. I. Fermentation, isolation, and physico-chemical and biological characteristics. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1987;40:1249–1255. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bishop DK, Li W. Cyclosporin A and FK506 mediate differential effects on T cell activation in vivo. J Immunol. 1992;148:1049–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaw KT, Ho AM, Raghavan A, Kim J, Jain J, Park J, Sharma S, Rao A, Hogan PG. Immunosuppressive drugs prevent a rapid dephosphorylation of transcription factor NFAT1 in stimulated immune cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11205–11209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peters DH, Fitton A, Plosker GL, Faulds D. Tacrolimus. A review of its pharmacology, and therapeutic potential in hepatic and renal transplantation. Drugs. 1993;46:746–794. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199346040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blazar BR, Taylor PA, Fitzsimmons WE, Vallera DA. FK506 inhibits graft-versus-host disease and bone marrow graft rejection in murine recipients of MHC disparate donor grafts by interfering with mature peripheral T cell expansion post-transplantation. J Immunol. 1994;153:1836–1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Storb R, Raff RF, Appelbaum FR, Deeg HJ, Fitzsimmons W, Graham TC, Pepe M, Pettinger M, Sale G, van der Jagt R, et al. FK-506 and methotrexate prevent graft-versus-host disease in dogs given 9.2 Gy total body irradiation and marrow grafts from unrelated dog leukocyte antigen-nonidentical donors. Transplantation. 1993;56:800–807. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199310000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nash RA, Etzioni R, Storb R, Furlong T, Gooley T, Anasetti C, Appelbaum FR, Doney K, Martin P, Slattery J, et al. Tacrolimus (FK506) alone or in combination with methotrexate or methylprednisolone for the prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease after marrow transplantation from HLA-matched siblings: a single-center study. Blood. 1995;85:3746–3753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uberti JP, Silver SM, Adams PT, Jacobson P, Scalzo A, Ratanatharathorn V. Tacrolimus and methotrexate for the prophylaxis of acute graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:1233–1238. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hiraoka A, Ohashi Y, Okamoto S, Moriyama Y, Nagao T, Kodera Y, Kanamaru A, Dohy H, Masaoka T. Phase III study comparing tacrolimus (FK506) with cyclosporine for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:181–185. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Inamoto Y, Flowers ME, Appelbaum FR, Carpenter PA, Deeg HJ, Furlong T, Kiem HP, Mielcarek M, Nash RA, Storb RF, et al. A retrospective comparison of tacrolimus versus cyclosporine with methotrexate for immunosuppression after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with mobilized blood cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;17:1088–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohen JJ, Fschbach M, Claman HN. Hydrocortisne resistance of graft vs host activity in mouse thymus, spleen and bone marrow. J Immunol. 1970;105:1146–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holler E, Kolb HJ, Wilmanns W. Treatment of GVHD--TNF-antibodies and related antagonists. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1993;12(Suppl 3):S29–S31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Deeg HJ, Lin D, Leisenring W, Boeckh M, Anasetti C, Appelbaum FR, Chauncey TR, Doney K, Flowers M, Martin P, et al. Cyclosporine or cyclosporine plus methylprednisolone for prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease: a prospective, randomized trial. Blood. 1997;89:3880–3887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Storb R, Pepe M, Anasetti C, Appelbaum FR, Beatty P, Doney K, Martin P, Stewart P, Sullivan KM, Witherspoon R, et al. What role for prednisone in prevention of acute graft-versus-host disease in patients undergoing marrow transplants? Blood. 1990;76:1037–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Quellmann S, Schwarzer G, Hubel K, Engert A, Bohlius J. Corticosteroids in the prevention of graft-vs-host disease after allogeneic myeloablative stem cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leukemia. 2008;22:1801–1803. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sayer HG, Longton G, Bowden R, Pepe M, Storb R. Increased risk of infection in marrow transplant patients receiving methylprednisolone for graft-versus-host disease prevention. Blood. 1994;84:1328–1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Halloran P, Mathew T, Tomlanovich S, Groth C, Hooftman L, Barker C. Mycophenolate mofetil in renal allograft recipients: a pooled efficacy analysis of three randomized, double-blind, clinical studies in prevention of rejection. The International Mycophenolate Mofetil Renal Transplant Study Groups. Transplantation. 1997;63:39–47. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199701150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu C, Seidel K, Nash RA, Deeg HJ, Sandmaier BM, Barsoukov A, Santos E, Storb R. Synergism between mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine in preventing graft-versus-host disease among lethally irradiated dogs given DLA-nonidentical unrelated marrow grafts. Blood. 1998;91:2581–2587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McSweeney PA, Niederwieser D, Shizuru JA, Sandmaier BM, Molina AJ, Maloney DG, Chauncey TR, Gooley TA, Hegenbart U, Nash RA, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with hematologic malignancies: replacing high-dose cytotoxic therapy with graft-versus-tumor effects. Blood. 2001;97:3390–3400. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giaccone L, McCune JS, Maris MB, Gooley TA, Sandmaier BM, Slattery JT, Cole S, Nash RA, Storb RF, Georges GE. Pharmacodynamics of mycophenolate mofetil after nonmyeloablative conditioning and unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2005;106:4381–4388. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perkins J, Field T, Kim J, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Fernandez H, Ayala E, Perez L, Xu M, Alsina M, Ochoa L, et al. A randomized phase II trial comparing tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil to tacrolimus and methotrexate for acute graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:937–947. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bolwell B, Sobecks R, Pohlman B, Andresen S, Rybicki L, Kuczkowski E, Kalaycio M. A prospective randomized trial comparing cyclosporine and short course methotrexate with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil for GVHD prophylaxis in myeloablative allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34:621–625. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kiehl MG, Schafer-Eckart K, Kroger M, Bornhauser M, Basara N, Blau IW, Kienast J, Fauser AA, Ehninger G, Armstrong VW, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil for the prophylaxis of acute graft-versus-host disease in stem cell transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:2922–2924. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dean R, Rybicki L, Sobecks R, Copelan E, Kalaycio M, Andresen S, Sungren S, Serafin M, Bolwell BJ. Comparison of Cyclosporine and Methotrexate with Cyclosporine and Mycophenolate Mofetil for Gvhd Prophylaxis in Myeloablative Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplantation. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2008:2240. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Srinivasan R, Geller N, Chakrabarti S, Espinoza-Delgado I, Donohue T, Leitman S, Bolan CD, Read EJ, Barrett JA, Childs RW. Evaluation of Three Different Cyclosporine-Based Graft Versus Host Disease (GVHD) Prophylaxis Regimens Following Nonmyeloablative Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2004:1236. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Storb R, Gluckman E, Thomas ED, Buckner CD, Clift RA, Fefer A, Glucksberg H, Graham TC, Johnson FL, Lerner KG, et al. Treatment of established human graft-versus-host disease by antithymocyte globulin. Blood. 1974;44:56–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mohty M. Mechanisms of action of antithymocyte globulin: T-cell depletion and beyond. Leukemia. 2007;21:1387–1394. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Finke J, Bethge WA, Schmoor C, Ottinger HD, Stelljes M, Zander AR, Volin L, Ruutu T, Heim DA, Schwerdtfeger R, et al. Standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin in haematopoietic cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors: a randomised, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:855–864. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Socie G, Schmoor C, Bethge WA, Ottinger HD, Stelljes M, Zander AR, Volin L, Ruutu T, Heim DA, Schwerdtfeger R, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease: long-term results from a randomized trial on graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin ATG-Fresenius. Blood. 2011;117:6375–6382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kumar A, Mhaskar AR, Reljic T, Mhaskar RS, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Anasetti C, Mohty M, Djulbegovic B. Antithymocyte globulin for acute-graft-versus-host-disease prophylaxis in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a systematic review. Leukemia. 2012;26:582–588. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Atta EH, de Sousa AM, Schirmer MR, Bouzas LF, Nucci M, Abdelhay E. Different Outcomes between Cyclophosphamide Plus Horse or Rabbit Antithymocyte Globulin for HLA-Identical Sibling Bone Marrow Transplant in Severe Aplastic Anemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Scheinberg P, Nunez O, Weinstein B, Scheinberg P, Biancotto A, Wu CO, Young NS. Horse versus rabbit antithymocyte globulin in acquired aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:430–438. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Atta EH, Dias DS, Marra VL, de Azevedo AM. Comparison between horse and rabbit antithymocyte globulin as first-line treatment for patients with severe aplastic anemia: a single-center retrospective study. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:851–859. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-0944-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Soiffer RJ, Lerademacher J, Ho V, Kan F, Artz A, Champlin RE, Devine S, Isola L, Lazarus HM, Marks DI, et al. Impact of immune modulation with anti-T-cell antibodies on the outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2011;117:6963–6970. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bacigalupo A, Lamparelli T, Bruzzi P, Guidi S, Alessandrino PE, di Bartolomeo P, Oneto R, Bruno B, Barbanti M, Sacchi N, et al. Antithymocyte globulin for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in transplants from unrelated donors: 2 randomized studies from Gruppo Italiano Trapianti Midollo Osseo (GITMO) Blood. 2001;98:2942–2947. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Johnson RW. Sirolimus (Rapamune) in renal transplantation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2002;11:603–607. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200211000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Abouelnasr A, Cohen S, Kiss T, Roy J, Lachance S. Defining the Role of Sirolimus in the Management of Graft-versus-Host Disease: From Prophylaxis to Treatment. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sehgal SN. Rapamune (RAPA, rapamycin, sirolimus): mechanism of action immunosuppressive effect results from blockade of signal transduction and inhibition of cell cycle progression. Clin Biochem. 1998;31:335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(98)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cutler C, Stevenson K, Kim HT, Richardson P, Ho VT, Linden E, Revta C, Ebert R, Warren D, Choi S, et al. Sirolimus is associated with veno-occlusive disease of the liver after myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2008;112:4425–4431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-169342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rosenbeck LL, Kiel PJ, Kalsekar I, Vargo C, Baute J, Sullivan CK, Wood L, Abdelqader S, Schwartz J, Srivastava S, et al. Prophylaxis with sirolimus and tacrolimus +/− antithymocyte globulin reduces the risk of acute graft-versus-host disease without an overall survival benefit following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:916–922. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pidala J, Kim J, Jim H, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Nishihori T, Fernandez H, Tomblyn M, Perez L, Perkins J, Xu M, et al. A randomized phase II study to evaluate tacrolimus in combination with sirolimus or methotrexate after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2012 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.067140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Armand P, Gannamaneni S, Kim HT, Cutler CS, Ho VT, Koreth J, Alyea EP, LaCasce AS, Jacobsen ED, Fisher DC, et al. Improved survival in lymphoma patients receiving sirolimus for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5767–5774. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Furlong T, Kiem HP, Appelbaum FR, Carpenter PA, Deeg HJ, Doney K, Flowers ME, Mielcarek M, Nash RA, Storb R, et al. Sirolimus in combination with cyclosporine or tacrolimus plus methotrexate for prevention of graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic cell transplantation from unrelated donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hale G, Waldmann H. Control of graft-versus-host disease and graft rejection by T cell depletion of donor and recipient with Campath-1 antibodies. Results of matched sibling transplants for malignant diseases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;13:597–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hamblin M, Marsh JC, Lawler M, McCann SR, Wickham N, Dunlop L, Ball S, Davies EG, Hale G, Waldmann H, et al. Campath-1G in vivo confers a low incidence of graft-versus-host disease associated with a high incidence of mixed chimaerism after bone marrow transplantation for severe aplastic anaemia using HLA-identical sibling donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:819–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Perez-Simon JA, Kottaridis PD, Martino R, Craddock C, Caballero D, Chopra R, Garcia-Conde J, Milligan DW, Schey S, Urbano-Ispizua A, et al. Nonmyeloablative transplantation with or without alemtuzumab: comparison between 2 prospective studies in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2002;100:3121–3127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chakraverty R, Peggs K, Chopra R, Milligan DW, Kottaridis PD, Verfuerth S, Geary J, Thuraisundaram D, Branson K, Chakrabarti S, et al. Limiting transplantation-related mortality following unrelated donor stem cell transplantation by using a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen. Blood. 2002;99:1071–1078. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Marsh JC, Gupta V, Lim Z, Ho AY, Ireland RM, Hayden J, Potter V, Koh MB, Islam MS, Russell N, et al. Alemtuzumab with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide reduces chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2011;118:2351–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mead AJ, Thomson KJ, Morris EC, Mohamedbhai S, Denovan S, Orti G, Fielding AK, Kottaridis PD, Hough R, Chakraverty R, et al. HLA-mismatched unrelated donors are a viable alternate graft source for allogeneic transplantation following alemtuzumab-based reduced-intensity conditioning. Blood. 2011;115:5147–5153. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-265413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Luznik L, Bolanos-Meade J, Zahurak M, Chen AR, Smith BD, Brodsky R, Huff CA, Borrello I, Matsui W, Powell JD, et al. High-dose cyclophosphamide as single-agent, short-course prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2010;115:3224–3230. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Raiola AM, Dominietto A, Ghiso A, Di Grazia C, Lamparelli T, Gualandi F, Bregante S, Van Lint MT, Geroldi S, Luchetti S, et al. Unmanipulated Haploidentical Bone Marrow Transplant and Posttransplantation Cyclophosphamide for Hematologic Malignancies after Myeloablative Conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Luznik L, O'Donnell PV, Symons HJ, Chen AR, Leffell MS, Zahurak M, Gooley TA, Piantadosi S, Kaup M, Ambinder RF, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation for hematologic malignancies using nonmyeloablative conditioning and high-dose, posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Hallek MJ, Storb RF, von Bergwelt-Baildon MS. The role of B cells in the pathogenesis of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;114:4919–4927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-161638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Crocchiolo R, Castagna L, El-Cheikh J, Helvig A, Furst S, Faucher C, Vazquez A, Granata A, Coso D, Bouabdallah R, et al. Prior rituximab administration is associated with reduced rate of acute GVHD after in vivo T-cell depleted transplantation in lymphoma patients. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:892–896. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Weaver CT. Expanding the effector CD4 T-cell repertoire: the Th17 lineage. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kappel LW, Goldberg GL, King CG, Suh DY, Smith OM, Ligh C, Holland AM, Grubin J, Mark NM, Liu C, et al. IL-17 contributes to CD4-mediated graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:945–952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Iclozan C, Yu Y, Liu C, Liang Y, Yi T, Anasetti C, Yu XZ. T helper17 cells are sufficient but not necessary to induce acute graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Teshima T, Maeda Y, Ozaki K. Regulatory T cells and IL-17-producing cells in graft-versus-host disease. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:833–852. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Beres AJ, Haribhai D, Chadwick AC, Gonyo PJ, Williams CB, Drobyski WR. CD8+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are induced during graft-versus-host disease and mitigate disease severity. J Immunol. 2012;189:464–474. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shin HJ, Baker J, Leveson-Gower DB, Smith AT, Sega EI, Negrin RS. Rapamycin and IL-2 reduce lethal acute graft-versus-host disease associated with increased expansion of donor type CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Blood. 2011;118:2342–2350. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-313684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Choi J, Ritchey J, Prior JL, Holt M, Shannon WD, Deych E, Piwnica-Worms DR, DiPersio JF. In vivo administration of hypomethylating agents mitigate graft-versus-host disease without sacrificing graft-versus-leukemia. Blood. 2011;116:129–139. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Goodyear OC, Dennis M, Jilani NY, Loke J, Siddique S, Ryan G, Nunnick J, Khanum R, Raghavan M, Cook M, et al. Azacitidine augments expansion of regulatory T cells after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2012;119:3361–3369. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Briones J, Novelli S, Sierra J. T-cell costimulatory molecules in acute-graft-versus host disease: therapeutic implications. Bone Marrow Res. 2011;2011:976793. doi: 10.1155/2011/976793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Alegre ML, Frauwirth KA, Thompson CB. T-cell regulation by CD28 and CTLA-4. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:220–228. doi: 10.1038/35105024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Saito K, Sakurai J, Ohata J, Kohsaka T, Hashimoto H, Okumura K, Abe R, Azuma M. Involvement of CD40 ligand-CD40 and CTLA4-B7 pathways in murine acute graft-versus-host disease induced by allogeneic T cells lacking CD28. J Immunol. 1998;160:4225–4231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wallace PM, Johnson JS, MacMaster JF, Kennedy KA, Gladstone P, Linsley PS. CTLA4Ig treatment ameliorates the lethality of murine graft-versus-host disease across major histocompatibility complex barriers. Transplantation. 1994;58:602–610. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199409150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Speiser DE, Bachmann MF, Shahinian A, Mak TW, Ohashi PS. Acute graft-versus-host disease without costimulation via CD28. Transplantation. 1997;63:1042–1044. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199704150-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yu XZ, Martin PJ, Anasetti C. Role of CD28 in acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1998;92:2963–2970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yu C, Linsley P, Seidel K, Sale G, Deeg HJ, Nash RA, Storb R. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4-immunoglobulin fusion protein combined with methotrexate/cyclosporine as graft-versus-host disease prevention in a canine dog leukocyte antigen-nonidentical marrow transplant model. Transplantation. 2000;69:450–454. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002150-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Poirier N, Mary C, Dilek N, Hervouet J, Minault D, Blancho G, Vanhove B. Preclinical Efficacy and Immunological Safety of FR104, an Antagonist Anti-CD28 Monovalent Fab' Antibody. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:2630–2640. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]