Abstract

Purpose

Endometrioid endometrial cancers (EECs) frequently harbor coexisting mutations in PI3K pathway genes, including PTEN, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, and KRAS. We sought to define the genetic determinants of PI3K pathway inhibitor response in EEC cells, and whether PTEN-mutant EEC cell lines rely on p110β signaling for survival.

Experimental Design

Twenty-four human EEC cell lines were characterized for their mutation profile and activation state of PI3K and MAPK signaling pathway proteins. Cells were treated with pan-class I PI3K, p110α and p110β isoform-specific, allosteric mTOR, mTOR kinase, dual PI3K/mTOR, MEK and RAF inhibitors. RNA interference (RNAi) was employed to assess effects of KRAS silencing in EEC cells.

Results

EEC cell lines harboring PIK3CA and PTEN mutations were selectively sensitive to the pan-class I PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941 and allosteric mTOR inhibitor Temsirolimus, respectively. Subsets of EEC cells with concurrent PIK3CA and/or PTEN and KRAS mutations were sensitive to PI3K pathway inhibition, and only 2/6 KRAS-mutant cell lines showed response to MEK inhibition. KRAS RNAi silencing did not induce apoptosis in KRAS-mutant EEC cells. PTEN-mutant EEC cell lines were resistant to the p110β inhibitors GSK2636771 and AZD6482, and only in combination with the p110α selective inhibitor A66, a decrease in cell viability was observed.

Conclusions

Targeted pan-PI3K and mTOR inhibition in EEC cells may be most effective in PIK3CA-mutant and PTEN-mutant tumors, respectively, even in a subset of EECs concurrently harboring KRAS mutations. Inhibition of p110β alone may not be sufficient to sensitize PTEN-mutant EEC cells and combination with other targeted agents may be required.

Keywords: endometrial cancer, PI3K pathway, KRAS, p110beta

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecological malignancy in the western world with an estimated 49,560 new cases and 8,190 deaths in 2013 in the United States(1). Approximately 80% of endometrial carcinomas are of endometrioid histology and are associated with a hyperestrogenic state(2, 3). Although the outcome of women with early stage EEC is favorable, it remains poor in patients with recurrent or metastatic disease(2). Thus, there is a need to improve our understanding of the disease at the molecular level and to refine current treatment strategies.

EECs have been shown to harbor, amongst other genetic aberrations(4-7), multiple co-occurring mutations in the PI3K pathway, including PTEN, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, and KRAS(4-11). Given the role of the PI3K signaling pathway in cellular growth, survival and endometrial cancer pathogenesis, inhibitors targeting different components of the pathway are currently being evaluated in preclinical and clinical studies (reviewed in(12, 13)). It is important to note, however, that there is considerable inter-tumor genetic heterogeneity and that different combinations of coexisting PI3K pathway mutations can be found in EECs(4-6, 9-11). The functional effect of these distinct mutational patterns affecting different components of the same pathway on activation of the downstream effector PI3K and RAF/MEK/ERK pathways and response to targeted therapies has yet to be fully established.

Preclinical models of cancer have identified KRAS and BRAF mutations to confer resistance to PI3K pathway inhibition (reviewed in(12, 13)). Recent phase I/II clinical trials provided evidence to suggest that colorectal cancer patients whose tumors harbored concomitant PIK3CA and KRAS mutations are resistant to PI3K pathway inhibition(14, 15), whereas subsets of ovarian cancers with coexisting PIK3CA and KRAS/BRAF mutations may be sensitive(14, 16). These data imply that not only the mutational repertoires but also epistatic interactions between different components of the PI3K pathway may be distinct in different tumor types(12).

The most commonly altered gene in EECs is PTEN, and up to 60% of PTEN-mutant tumors also harbor a coexisting PIK3CA gain-of-function mutation(6-11). PTEN-deficient tumors, in particular breast and prostate cancer cells, have been reported to mainly depend on p110β signaling for tumorigenesis, proliferation and survival(17-20), contrary to PIK3CA-mutant tumors which rely on p110α(21). A p110β isoform-specific inhibitor is currently being tested in patients with advanced PTEN-deficient solid tumors, including EECs, prostate, ovarian, breast and colorectal cancer amongst others (NCT01458067).

Given that EECs frequently harbor coexistent mutations in PTEN, PIK3CA, PIK3R1 and KRAS, in this study we sought to determine the genetic predictors of response to small molecule PI3K pathway inhibitors, and whether PTEN-mutant EEC cell lines are reliant on p110β for survival. To address these questions, we investigated the effects of different PI3K and RAF/MEK/ERK pathway inhibitors on cell viability in a panel of 24 EEC cell lines, and found that cells harboring PIK3CA and PTEN mutations were selectively sensitive to pan-PI3K and allosteric mTOR inhibition, respectively. In addition, we observed that subsets of EEC cell lines with concomitant PIK3CA and/or PTEN and KRAS mutations were responsive to PI3K pathway inhibition, and subsets of KRAS-mutant EEC cell lines to RAF/MEK/ERK pathway inhibition. We further found that EEC cell lines were not responsive to single-agent p110β inhibition irrespective of the PTEN status, and a reduction in cell viability was only observed upon combination with a p110α inhibitor.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cell lines

The human endometrioid endometrial cancer (EEC) cell lines ECC-1, HEC-1-A, HEC-1-B, and RL95-2 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD, USA), AN3-CA, EFE-184, MFE-280, EN, and MFE-296 from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ; Braunschweig, Germany), JHUEM-3 from RIKEN Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan), and HEC-59, HEC-265, HEC-251, HEC-116, HEC-108, SNG-II, and SNG-M from the Japanese Health Science Research Resources Bank (Osaka, Japan). Ishikawa were obtained from the Central Cell Services Facility at Cancer Research UK (CRUK). HEC-151, HEC-50B, HEC-6, HHUA, and KLE were kindly provided by Dr F. McCormick (University of California San Francisco, USA), and NOU-1 by Dr R. Zeillinger (Medical University of Vienna, Austria)(Supplementary Table 1). Cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling. As controls for KRAS silencing experiments authenticated NCI-H460 and NCI-H727 lung cancer cell lines were obtained from the CRUK Central Cell Services Facility, for the p110β inhibitor experiments authenticated PC3 prostate cancer cells were obtained from the CRUK Facility and BT549 and HCC70 breast cancer cell lines from ATCC(22).

Mutation analysis

DNA from EEC cell lines was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Crawley, West Sussex, UK) and subjected to mutation screening to detect 238 mutations in 19 known cancer genes using the OncoCarta Panel v1.0 (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) as previously described(23). Identified mutations were validated using Sanger sequencing. In addition, Sanger sequencing of the coding sequences of PTEN, PIK3CA, and PIK3R1 was performed as previously described(22)(see Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 2).

Cell viability assays and small molecule inhibitors

Cells were plated in 96-well microtiter plates at densities ranging from 1,500 to 15,000 cells/well, optimized for untreated control cells to be 80-90% confluent at the endpoint of the experiment. After 24h, cells were treated with serial dilutions (100pM to 10μM) of PI3K and MAPK pathway inhibitors (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 3). Cell viability was assessed after 72h of treatment by incubation with CellTiter Blue (Promega, Southampton, UK) for 1.5h. The drug concentration required for survival of 50% of cells relative to untreated cells (surviving fraction 50, SF50(22, 24); for Temsirolimus SF60, see Supplementary Fig. 1) was determined using GraphPad Prism version 5.0d. Cell lines that failed to achieve the SF50 to a given drug were nominally assigned as the highest concentration screened (i.e. 10μM)(25). At least three independent experiments in triplicate per cell line/targeted drug were performed. Association between a mutation and response to a targeted agent was determined using a Fisher’s exact test and a two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

KRAS silencing

A pool of 4 siRNA duplexes (siGENOME; “SMARTpool”; Thermo Scientific Dharmacon, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to silence KRAS(26). Reverse transfection employing 37.5nM siRNA was performed using Lullaby (OZ Biosciences, Marseille, France) or Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Life Technologies) transfection reagents for EEC cell lines, selected from 25 transfection reagents tested for having the highest gene silencing efficiency but least toxicity, and Dharmafect 1 (Thermo Scientific Dharmacon) for lung cancer cell lines. Non-targeting siRNA pool #2 (“scrambled”), RISC-free, and SMARTpools targeting UBB and PLK1 were used as controls. Cell viability was determined 96h post transfection using CellTiter Blue as described above, and apoptosis induction using the Apo-ONE Caspase-3/7 assay (Promega) by incubation of cells for 5 hours(22, 26, 27).

Western blot analysis and protein quantification

Standard western blotting was performed as previously described(22), using antibodies against PTEN, p110α, p110β, PARP, β-Actin (Cell Signaling Technology; New England Biolabs, Hitchin, UK), KRAS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and α-Tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). For quantitative western blotting, membranes were probed simultaneously with antibodies against i) ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), ii) AKT and phospho-AKT (Ser473), iii) AKT and phospho-AKT (Thr308), or iv) S6 ribosomal protein (rpS6) and phospho-rpS6 (Ser235/236) (all Cell Signaling Technology). Conjugated secondary antibodies (IRDye 680LT; IRDye 800CW; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) were detected using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR)(22).

RESULTS

EEC cell lines harbor multiple mutations in the PI3K pathway

To characterize the panel of EEC cell lines for their mutational patterns, and to assess whether the different combinations of coexisting PI3K pathway mutations observed in primary EECs can be found in EEC cell lines, we employed the OncoCarta Panel v1.0 (Sequenom Inc.) and performed Sanger sequencing of PTEN, PIK3CA, and PIK3R1 coding sequences. The Oncocarta Panel v1.0 screening of 238 common somatic mutations across 19 known cancer genes revealed that none of the EEC cell lines studied harbored mutations in ABL1, AKT1, AKT2, BRAF, CDK4, ERBB2, FGFR1, FGFR3, FLT3, JAK-2, KIT, MET, PDGFA or RET (data not shown) but one EGFR (A389V; HEC-6), NRAS (G12D; HEC-151) and HRAS (Q61H; RL95-2) mutation were found (Table 1). Combined with Sanger sequencing we observed that the prevalence of mutations in PTEN (17/24, 70.8%), PIK3CA (13/24, 54.2%), PIK3R1 (9/13, 37.5%), and KRAS (6/24, 25%) (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2A) in the EEC cell lines was comparable to those reported in primary human EECs(7, 9, 10), as was the high frequency of PIK3CA mutations within exons 1–7(9, 11). In line with previous observations(13), a subset (3/17; 17.6%) of PTEN-mutant EEC cell lines expressed detectable PTEN protein by western blotting (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2B). As observed in primary EECs(6, 9, 10), different components of the PI3K pathway were altered in the same cell line, and included concomitant mutations in PTEN/PIK3CA (5/24; 20.8%), PTEN/PIK3R1 (6/24; 25%), PTEN/PIK3CA/PIK3R1 (2/24; 8%), PTEN/PIK3CA/KRAS (3/24; 12.5%), PIK3CA/KRAS (2/24; 8%), and PIK3R1/KRAS (1/24; 4.2%)(Supplementary Fig. 2A). In EFE-184, JHUEM-3, and KLE cells none of the PI3K pathway mutations assessed were identified (Table 1). For nine and 19 cell lines, mutation profiles are available on the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC; www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic/) and the Broad-Novartis Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE; http://www.broadinstitute.org/ccle/home)(4) websites, respectively, and a high agreement between the results of our analysis and those available online was observed (data not shown). Taken together, the prevalence of the PI3K pathway mutations assessed in our EEC cell line panel mirrors that reported for primary EECs.

Table 1. Mutational profile of EEC cell lines.

Mutations identified in 24 human EEC cell lines using SequenomOncoCarta Panel v1.0 and Sanger sequencing for PTEN, PIK3CA, and PIK3R1 transcripts (amino acid changes shown). For PTEN protein, see Supplementary Figure 2B.

| Cell line | EGFR | KRAS | NRAS | HRAS | PIK3CA | PIK3R1 | PTEN | PTEN protein | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AN3-CA | R557_K561>Q | R130fs | absent | |||||

| 2 | ECC-1 | L570P | V317fs; V290fs | absent | |||||

| 3 | EFE-184 | ||||||||

| 4 | EN | T1025A, T1031A | N260S | K267fs | absent | ||||

| 5 | HEC-1-A | G12D | G1049R | ||||||

| 6 | HEC-1-B | G12D | G1049R | ||||||

| 7 | HEC-108 | A331V | K6fs; E288fs | absent | |||||

| 8 | HEC-116 | R88Q | R55_L70>S; R173C | absent | |||||

| 9 | HEC-151 | G12D | C420R | I33del; Y76fs | weak | ||||

| 10 | HEC-251 | M1043I | S10N; E299X | weak | |||||

| 11 | HEC-265 | H180fs; Q586fs | L318fs | absent | |||||

| 12 | HEC-50B | G12D | E468InsGEYDRLYE | ||||||

| 13 | HEC-59 | R38C | K567E; S460fs | Y46H; R233X; P246L; L265fs | absent | ||||

| 14 | HEC-6 | A289V | R108H; C420fs | V85fs; V290fs | absent | ||||

| 15 | HHUA | G12V | R88Q | K164fs; V290fs | absent | ||||

| 16 | Ishikawa | L570P | V317fs; V290fs | absent | |||||

| 17 | JHUEM-3 | ||||||||

| 18 | KLE | ||||||||

| 19 | MFE-280 | H1047Y; I391M | |||||||

| 20 | MFE-296 | I20M; P539R | R130Q; N323fs | ||||||

| 21 | NOU-1 | G12D | R38H | no mRNA expression | absent | ||||

| 22 | RL95-2 | Q61H | R386G | M134I; R173H; N323fs | absent | ||||

| 23 | SNG-II | K6fs | absent | ||||||

| 24 | SNG-M | G12V | R88Q | K164fs; V290fs | absent |

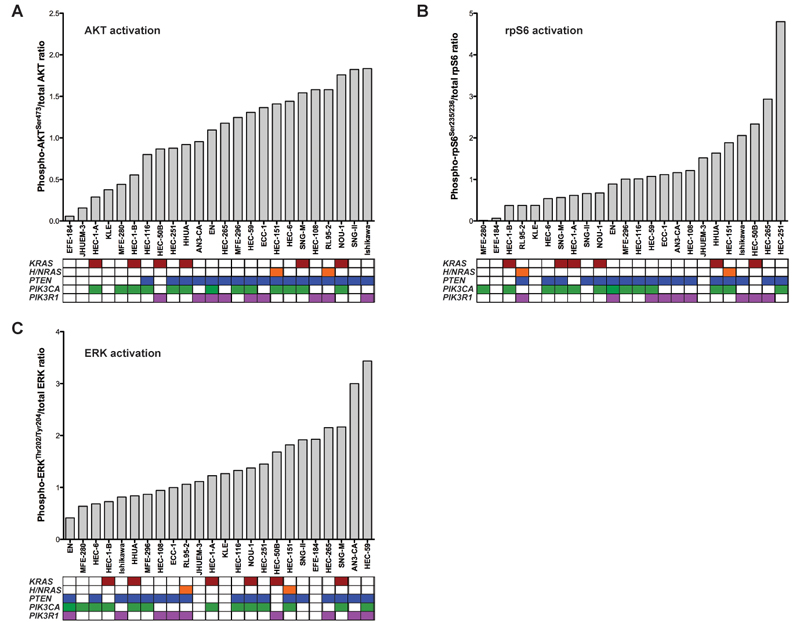

AKT activation is associated with PTEN status

As EEC cells harbor different combinations of concomitant PI3K pathway mutations, we sought to determine the associations between PTEN, PIK3CA, PIK3R1 and RAS mutations and effector pathway activation downstream of these genes. For this, baseline activation of AKT(Ser473), ribosomal protein (rp)-S6(Ser235/236) and ERK(Thr202/Tyr204) was determined by quantitative infrared fluorescent western blotting (LI-COR) (Supplementary Fig. 3). In a way akin to breast cancer cells(28), we observed that in EEC cells PI3K pathway activation as determined by levels of AKT phosphorylation was significantly associated with PTEN mutation status (Mann-Whitney U (MWU) test, two tailed, P<0.001; Fig. 1A), whereas no association between activating PIK3CA mutations and phospho-AKT(Ser473) levels was observed (MWU, P=0.772). The three PTEN-mutant cell lines that retained PTEN protein did not differ in terms of their levels of phospho-AKT expression from those devoid of PTEN protein expression (MWU, P=0.344). The key signaling node mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and one of its downstream targets rpS6 respond to numerous inputs including growth factors, amino acids and energy, and is stimulated by the PI3K and RAF/MEK/ERK pathways(29). We observed that EEC cells with wild-type PTEN had lower levels of rpS6 activation than those with mutant PTEN (Fig. 1B), however this association was no longer statistically significant (MWU, P=0.075). Levels of ERK activation in EEC cell lines were not significantly associated with their PTEN, PIK3CA, PIK3R1 or RAS mutation status (Fig. 1C), and may in part be driven by upstream aberrant growth factor receptor signaling not interrogated here. Of note, neither AKT and rpS6 activation nor ERK activation was associated with the RAS mutation status of the cells (MWU, AKT P=0.665, rpS6 P=0.714, ERK P=0.973). These data provide evidence to suggest that AKT activation is associated with the PTEN status and that PIK3CA gain-of-function and PTEN loss-of-function mutations may have distinct effects on AKT and PI3K pathway activation in EECs.

Figure 1. Associations between PTEN, PIK3CA, PIK3R1 and RAS mutations and AKT, rpS6 and ERK activation in EEC cells.

A, AKT and phospho-AKT(Ser473), B, rpS6 and phosphor-rpS6(Ser235/236), and C, ERK and phospho-ERK(Thr202/Tyr204) were quantified using quantitative infrared western blotting (LI-COR; see Supplementary Fig. 3), and phospho-/total protein ratios ordered by increasing levels of activation. Mutational profiles of each cell line are shown below the graph where columns represent individual cell lines, rows represent genes, and colored boxes the presence of a mutation.

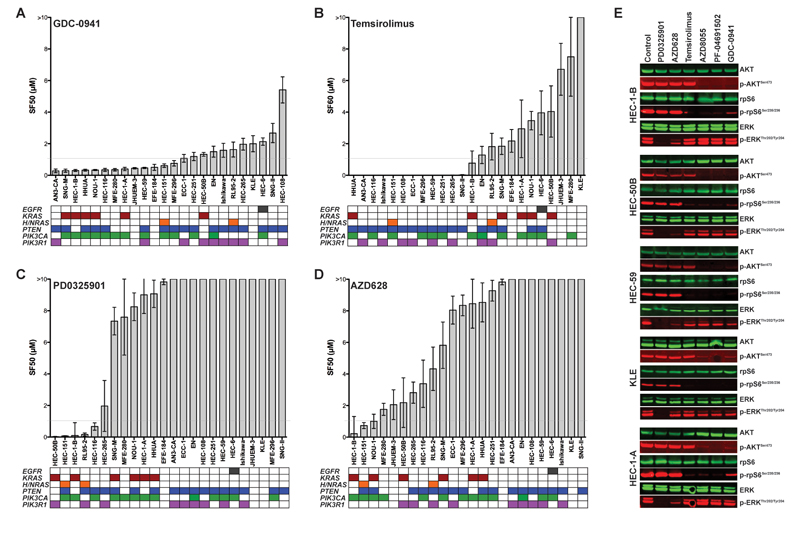

Genetic predictors of response are distinct between different types of PI3K pathway inhibitors

We next tested the response of the 24 EEC cell lines to targeted PI3K pathway inhibitors and determined the association with PTEN, PIK3CA, PIK3R1, and RAS mutations. Using a cell viability assay, we observed a range of responses to the pan-class I PI3K small molecule inhibitor GDC-0941 in our EEC cell line panel after 72h of treatment, with 54% of cells having a SF50 below 1μM (Fig. 2A). Responses were not associated with the cells’ doubling time (mean sensitive 38.84 ± 5.47h, mean resistant 36.96 ± 4.70h, MWU, P=0.724) but cell lines harboring a PIK3CA mutation were significantly more sensitive to GDC-0941 than PIK3CA wild-type cells (Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed, P=0.038). We found no significant association between PTEN status and GDC-0941 response (P=0.386). In addition, a subset of EEC cell lines tested here harboring coexisting PIK3CA/KRAS or PIK3CA/PTEN/KRAS mutations were GDC-0941 responsive (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Response of EEC cells to PI3K and RAF/MEK/ERK pathway inhibitors and association with mutation patterns.

A, surviving fractions of 50% (SF50s) of 24 EEC cell lines treated for 72h with serial dilutions of the pan-class I PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941 relative to untreated cells were determined using the CellTiter-Blue assay, ordered from lowest to highest (mean of at least three independent experiments in triplicate ± SEM). Rows below the chart represent genes, and colored boxes the presence of a mutation. B, SF60s of the allosteric mTOR inhibitor Temsirolimus. C, SF50s of the MEK inhibitor PD0325901. D, SF50s of the RAF inhibitor AZD628. E, EEC cell lines HEC-1-B, HEC-50B, HEC-59, KLE and HEC-1-A were treated for 4h with 1μM of the MEK inhibitor PD0325901, the RAF inhibitor AZD628, the allosteric mTOR inhibitor Temsirolimus, the mTOR kinase inhibitor AZD8055, the PI3K/mTOR inhibitor PF-04691502 and the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting for total and phosphorylated levels of AKT, rpS6, and ERK1/2 on the same membrane, and detected by near infrared two-color detection (LI-COR; Odyssey).

Targeting the PI3K pathway more downstream revealed that PTEN mutations, rather than PIK3CA mutations, were significantly associated with response of EEC cells to the allosteric mTOR inhibitor Temsirolimus (P=0.023; Fig. 2B; doubling time mean Temsirolimus-sensitive 32.98 ± 3.0h, mean -resistant 43.88 ± 6.74h, MWU, P= 0.420). Whilst EEC cell lines harboring RAS mutations were generally less responsive to Temsirolimus, this association was not statistically significant (K/H/NRAS, P=0.391; KRAS, P= 0.357). It should be noted, however, that only three cell lines in our EEC panel had co-existing PTEN and KRAS mutations, of which one was Temsirolimus responsive. In addition, with exception of KLE cells, which are wild-type for PTEN, PIK3CA, PIK3R1 and RAS and show low levels of AKT and rpS6 activation (Fig. 1), all EEC cell lines were sensitive to the ATP-competitive mTOR kinase and dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors AZD8055 and PF-04691502, respectively, irrespective of the RAS mutation status (Supplementary Fig. 4A and 4B).

To test whether EEC cells are responsive to RAF/MEK/ERK pathway inhibition, we treated the cell line panel with serial dilutions of the non-ATP-competitive MEK inhibitors PD0325901 and AZD6244 and the ATP-mimetic CRAF/BRAF inhibitor AZD628. In total, only six cell lines had a SF50 below 1μM and in the vast majority of EEC cells treatment with 10μM of MEK/RAF inhibitors did not result in 50% inhibition of viability compared to the control (Fig. 2C and 2D; Supplementary Fig. 4C). Five cell lines (21%) were sensitive to the MEK inhibitor PD0325901, and response was significantly associated with the presence of KRAS, HRAS or NRAS mutations (P=0.028) but not with the doubling time of cells (mean sensitive 30.76 ± 0.90h, mean resistant 39.88 ± 4.45h, MWU, P= 0.743). Only two out of six KRAS-mutant EEC cells were sensitive to this small molecule inhibitor (P=0.568), which both harbored coexisting PIK3CA or PIK3R1 but not PTEN mutations. Three EEC cells showed SF50s below 1μM when treated with the selective RAF inhibitor AZD628 (Fig. 2D), and the presence of KRAS, HRAS or NRAS mutations was significantly associated with response to this agent (P=0.028), whilst KRAS mutations alone failed to show a statistically significant association (P=0.143). It should be noted, however, that although the associations between mutations in RAS and MEK/RAF inhibitor response was statistically significant and showed a high negative predictive value (i.e. the lack of RAS mutations predicted resistance to these agents), the positive predictive value of a KRAS, HRAS or NRAS mutation to predict response to PD0325901 and AZD628 treatment was only 50% and 37.5%, respectively. As expected, given the absence of BRAFV600E gene mutations in the cell lines tested, none of the cell lines studied was sensitive to the BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032 (data not shown).

We next investigated whether the reduction in cell viability caused by the agents tested was the result of increased apoptosis. In the setting employed, apoptosis induction as determined by poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage could not be observed (Supplementary Fig. 5A), suggesting that the single-agent small molecule inhibitors tested in our cell line panel are likely to elicit preferentially cytostatic effects. The targeted agents used, however, inhibited their respective targets in EEC cells, as treatment with the MEK and RAF inhibitors PD0325901 and AZD628 resulted in a decrease in ERK phosphorylation, whereas the mTORC1 inhibitor Temsirolimus led to a marked reduction in rpS6 phosphorylation, and the PI3K, mTOR kinase, and dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors GDC-0941, AZD8055, and PF-04691502 to a decrease of both AKT and rpS6 phosphorylation compared to untreated control cells (Fig. 2E). In addition, as compared to single-agent treatment, combination treatment with PI3K and MAPK pathway inhibitors resulted in decreased cell viability and/or increased cell death of EEC cells (Supplementary Fig. 5B-D).

Taken together, our results demonstrate that the genetic predictors of response may be distinct between different PI3K pathway inhibitors in EEC cells. Our data further suggest that a subset of EEC cells harboring oncogenic RAS mutations and concomitant PIK3CA or PTEN mutations may still be sensitive to PI3K pathway perturbation. Finally, only a minority of EEC cells harboring KRAS mutations was shown to be sensitive to MEK or RAF inhibition.

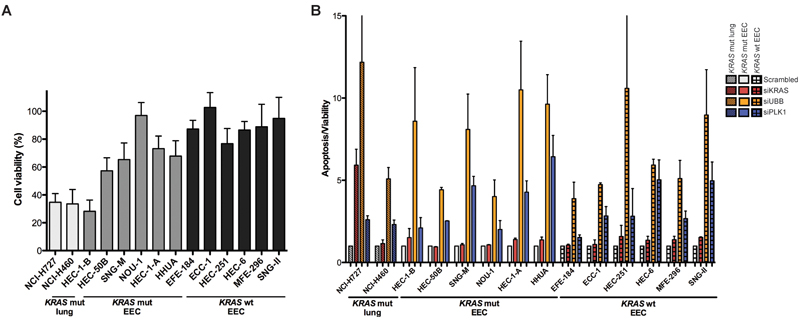

KRAS silencing does not induce apoptosis in EEC cells

We used RNA interference (RNAi) to investigate whether EEC cells harboring KRAS mutations would be dependent of the expression of this mutant oncogene for their survival. We determined the effect of KRAS silencing on cell viability in the six KRAS-mutant cell lines of our EEC cell line panel and six KRAS wild-type cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 6A). In addition, we used two KRAS-mutant lung cancer cell lines, NCI-H727 and NCI-H460 as controls (Supplementary Fig. 6B), in which we previously observed reduced cell viability upon KRAS silencing(26)(30). As expected, cell viability was markedly decreased upon KRAS depletion in the KRAS-mutant lung cancer cell lines as compared to scrambled control (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, only one out of the six KRAS-mutant EEC cells (HEC-1-B cells, a cell line that was sensitive to all PI3K and RAF/MEK/ERK pathway inhibitors tested above) showed a reduction in cell viability following KRAS silencing comparable to the levels seen in the lung cancer cells. The effect of KRAS silencing on cell viability in the other five KRAS-mutant EEC cell lines was significantly lower than that of KRAS-mutant lung cancer cell lines (t-test, two-tailed, P=0.0047) and only marginally but not statistically significantly higher than that in KRAS wild-type EEC cells (KRAS mut: mean 72.13±15.04% (95% confidence interval (CI) 53.45-90.81), KRAS wild-type: mean 89.52±8.71% (95% CI 80.38-98.65), t-test, two-tailed, P=0.06123).

Figure 3. KRAS dependency in lung and EEC cell lines harboring activating KRAS mutations.

A, cell viability was determined 96h post siRNA-mediated KRAS silencing using a pool of four siRNA duplexes targeting KRAS (SMARTpool) in two KRAS-mutant lung, six KRAS-mutant and six KRAS wild-type EEC cell lines. Cell viability is presented for each cell line relative to its non-targeting siRNA pool #2 (“scrambled”) control, set to 100% (mean of at least three independent experiments in triplicate ± SD). B, apoptosis induction assessed 96h post transfection, depicted as ratio of Caspase-3/7 activation determined using the Apo-ONE assay over cell viability determined using CellTiter-Blue in KRAS-mutant lung cancer (striped bars), KRAS-mutant (open bars) and KRAS wild-type (checked bars) EEC cell lines (mean of at least two independent experiments in triplicate ± SEM). Apoptosis induction following siRNA-mediated silencing of KRAS ablation (red bars), and of the positive controls UBB (yellow bars) and PLK1 (blue bars) is presented for each cell line relative to its non-targeting siRNA pool #2 (i.e. scrambled) control (set to 1). Mut: mutant, wt: wild-type.

Previous work(31) has demonstrated that the KRAS-mutant NCI-H727 lung cancer cells are ‘KRAS-dependent’, given that Caspase-3 cleavage was observed following KRAS ablation, whereas the KRAS-mutant NCI-H460 cells were classified as KRAS-independent, as KRAS silencing did not result in increased apoptosis. These observations were confirmed here using a fluorescent Caspase 3/7 assay, and strong KRAS siRNA silencing-induced apoptosis was seen in NCI-H727 but not NCI-H460 cells (Fig. 3B). Irrespective of their KRAS status, some EEC cells showed a slight increase in Caspase 3/7 activation compared to scrambled control upon KRAS silencing, however there was no statistically significant difference in apoptosis induction between KRAS-mutant and KRAS wild-type EEC cells (MWU test, P=0.485). Also the increase in Caspase 3/7 activation observed in the KRAS-mutant HEC-1-B cells, which showed marked reduction in cell viability similar to that in lung cancer cells (Fig. 3A), was only modest (scrambled: 1.0, KRASsi: 1.51) as compared to the KRAS-dependent NCI-H727 cells (scambled: 1.0, KRASsi: 5.92, Fig.3B). These data provide additional evidence to suggest that a subset of EEC cell lines with activating KRAS mutations may not be necessarily dependent on KRAS signaling for their survival, and that KRAS silencing-induced apoptosis, a feature previously used to determine ‘KRAS addiction’ in lung and pancreas adenocarcinoma cell lines(31), was not observed in KRAS-mutant EEC cells.

p110β inhibition alone is not sufficient to sensitize EEC cells harboring PTEN mutations

Selective targeting of p110β is currently being assessed in patients with advanced PTEN-deficient cancers, including EECs. Given that i) PTEN and PIK3CA mutations frequently coexist in EECs, ii) that PIK3CA-mutant tumors have been shown to rely on p110α (21), and iii) that here we demonstrated that both p110α and p110β are expressed in EECs irrespective of the PTEN status (Fig. 4A), we sought to define whether inhibition of p110β alone would indeed be sufficient to sensitize PTEN-mutant EEC cells. Contrary to GDC-0941, which inhibits all class I PI3K isoforms (i.e. p110α, p110β, p110δ and p110γ), treatment with the p110β isoform-specific inhibitors GSK2636771, AZD6482 and TGX-221 or the p110α isoform-specific inhibitor A66 revealed that the EEC cell lines tested were resistant to these agents (SF50 above 1μM; Supplementary Fig. 7A-D). In addition, upon 72h treatment with the p110β inhibitors GSK2636771 and AZD6482, cell viability was significantly more decreased in the control cells (i.e. previously described p110β-reliant PTEN-deficient PC3 prostate and BT549 and HCC70 breast cancer cell lines(17, 18)) than in PTEN-mutant and PTEN wild-type EEC cells (Fig. 4B). No significant difference in cell viability following p110β inhibition between PTEN-mutant and PTEN wild-type EEC cell lines was found (1μM/10μM GSK2636771: PTEN wt vs PTEN mut EECs, MWU P=0.128/P=0.341; 1μM/10μM AZD6482: PTEN wt vs PTEN mut EECs, MWU P=0.849/P=0.485; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. p110α and p110β expression, and p110β dependency in EEC cells.

A, whole-cell lysates of two PTEN wild-type and six PTEN-mutant EEC cell lines were analyzed by western blotting for p110α and p110β, and α-Tubulin as loading control. B, cell viability was determined after 72h of treatment with indicated concentrations of the p110β selective inhibitors GSK2636771 (left) and AZD6482 (right) in three p110β-reliant breast and prostate cancer cell lines (black circles), seven PTEN wild-type EEC cells (gray boxes), and 17 PTEN-mutant EEC cells (black triangles). Mann-Whitney U, two-tailed, *P<0.05. C, PTEN-deficient p110β-reliant HCC70 breast and PC3 prostate cancer cell lines were treated for 4h with indicated concentrations of the pan-class I PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941, p110α inhibitor A66, p110β inhibitor GSK2636771 and the p110β inhibitor AZD6482. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting for total and phosphorylated levels of AKT(Ser473) and AKT(Thr308), and detected by near infrared two-color detection (LI-COR; Odyssey); D, EEC cell lines HEC-50B (PTEN wt) and HEC-116 (PTEN mut) were treated for 4h with indicated concentrations of the pan-class I PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941, p110α inhibitor A66, p110β inhibitor GSK2636771 and the p110β inhibitor AZD6482, alone or in combination. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting for total and phosphorylated levels of AKT(Ser473) and AKT(Thr308), and detected by near infrared two-color detection. E, cell viability was determined after 72h of treatment with indicated concentration of the p110β selective inhibitors GSK2636771 (left) and AZD6482 (right), alone (blue) or in combination with the p110α inhibitor A66 (red), in three p110β-reliant breast and prostate cancer cell lines (black), and five PTEN-mutant EEC cells. Mut: mutant, wt: wild-type.

Western blot analysis of activated AKT in PC3, BT549 and HCC70 controls and in EEC cell lines revealed a strong effect of pan-class I PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941 treatment on both AKT phosphorylation sites (i.e. AKT(Ser473) and AKT(Thr308)), in contrast to treatment with the p110α selective inhibitor A66 (Fig. 4C and 4D; Supplementary Fig. 8A and 8B). Inhibition of p110β by GSK2636771 or AZD6482 led to a marked decrease of AKT phosphorylation only in the control prostate and breast cancer cell lines, whereas only marginal effects on AKT activation were observed in EEC cells (Fig. 4C and 4D; Supplementary Fig. 8A-8C). In fact, combination of the p110β inhibitors with the p110α inhibitor A66 at relatively high concentrations was required to decrease levels of AKT phosphorylation comparable to those seen following treatment with the pan-class I PI3K inhibitor GDC-0841 (Fig. 4D; Supplementary Fig. 8A and 8C), and to decrease cell viability in both PTEN-mutant and PTEN wild-type EEC cells to levels similar to those observed in the p110β-dependent PC3, BT549 and HCC70 cells (Fig. 4E; Supplementary Fig. 8D). Taken together, our data provide evidence to suggest that p110β inhibition alone is not sufficient to induce a marked reduction in viability of PTEN-mutant EEC cells, and that this is only obtained upon concurrent targeting of p110β and other p110 isoforms.

DISCUSSION

The PI3K pathway is activated in >80% of EECs(9, 10), and understanding the biological implications of mutations affecting genes in this pathway holds great promise for novel treatment strategies for the disease. Unlike in breast cancer(32), co-occurrence of mutations targeting different PI3K pathway components downstream of growth factor receptors in EECs is common. Using EEC cell lines as a model, we here demonstrate that PI3K pathway activation in EEC cells as assessed by AKT(Ser473) phosphorylation is associated with the presence of PTEN mutations, irrespective of the PIK3CA, PIK3R1 or RAS mutation status. These observations imply that the functional impact of mutations affecting different genes pertaining to the PI3K pathway (e.g. PTEN, PIK3CA, and PIK3R1) on AKT phosphorylation and PI3K pathway activation may be distinct(28). In addition, no associations between ERK activation and mutations in the PI3K pathway and RAS were found, suggesting that other aberrations, including those affecting growth factor receptors, may play a role in activation of the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in EECs.

We further demonstrate that in EEC cell lines distinct genetic predictors are associated with response to different modalities of PI3K pathway inhibitors. In a way akin to breast cancer cell lines(25), PIK3CA mutations were predictive of response to the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941. At variance with breast cancer cells, where PTEN-deficiency has been shown to be associated resistance to PI3K pathway inhibition(12, 22, 33, 34), response to the allosteric mTOR inhibitor Temsirolimus was found to be associated with PTEN mutations in EEC cells. These observations provide evidence to suggest that mutations in different components of the PI3K pathway may have distinct functional effects depending on the tumor type, their overall genetic landscape and epistatic interactions, and that a predictive biomarker identified in one cancer type may not necessarily be a predictor in another type. In fact, the interactions between oncogenic RAS mutations and resistance to PI3K pathway inhibition (reviewed in(12, 13)) lend further credence to this notion, as their impact appear to be context- and tumor type-dependent. In recent early clinical trials, colorectal cancers harboring concomitant PIK3CA and KRAS mutations were found to be resistant to PI3K pathway inhibitor treatment(14, 15), whereas a subset of ovarian cancers with coexisting PIK3CA and KRAS/BRAF mutations were sensitive(14, 16). In line with previous in vitro studies(9, 35) and clinical trials(36), we did observe that EEC cells harboring KRAS mutations showed decreased sensitivity to allosteric mTOR inhibition; however, we did not find significant associations between the presence of KRAS mutations and PI3K pathway inhibitor response. In particular, subsets of EEC cell lines with coexistent PIK3CA/KRAS and PTEN/KRAS mutations were sensitive to GDC-0941 and Temsirolimus treatment, respectively. It should be noted, however, that contrary to our in vitro findings, two recent phase II clinical trials testing allosteric mTOR inhibitors in patients with advanced or metastatic endometrial cancer did not identify PTEN status or any other marker assessed to be associated with response or clinical outcome(36, 37). Unlike in our cell line-based study, both clinical trials included patients not only with EEC but also with serous, adenosquamous, and clear cell cancers, which are known to harbor genetic aberrations distinct from those of EECs(38), which may in part be accountable for the disparate results. In addition, the clinical trials by Tredan et al(41) and Oza et al(42) were not sufficiently powered to perform subgroup analyses of EEC patients only, and results from ongoing clinical studies testing mTOR inhibitors in women with EEC are eagerly awaited.

One aspect that is germane for the translation of genetic information into clinical useful tests is the identification of driver mutations(39). Here, only a subset of KRAS-mutant EEC cells was responsive to MEK inhibition, and siRNA-mediated silencing of KRAS resulted in a decrease of cell viability to levels seen in KRAS-mutant lung cancer cells in only one out of the 6 KRAS-mutant EEC cell lines tested. In fact, apoptosis induction was only observed in the ‘KRAS-addicted’ lung cancer cell line NCI-H727(31) but not in KRAS-mutant EEC cells upon KRAS siRNA-mediated silencing. Although larger panels of KRAS-mutant EEC cell lines may be required to increase the statistical power for the study of KRAS dependency in EECs and targeted drug response, our findings suggest that there may be subsets of KRAS-mutant EEC cells, where the activity of KRAS mutations proven to be oncogenic in other cancer types may not be required for their survival. This emphasizes the notion that driver mutations in one tumor type may not necessarily constitute drivers in another tumor type(39, 40). One could hypothesize that in these EECs, epistatic interactions between the numerous mutations identified in this disease(4, 6) are such that loss of oncogenic KRAS signaling may be compensated for by activation of alternative signaling pathways. Further studies to determine the biological and clinical importance of these epistatic interactions are warranted.

There are several lines of evidence from mouse models and other preclinical studies(17-20) to suggest that p110β activation may be required for tumorigenesis driven by PTEN loss-of-function in different cancer types. Analysis of hundreds of cell lines of different tumor types revealed selectivity for PTEN-mutant cells for TGX-221 and AZD6482 p110β inhibitor response but also for CDKN2A- and PIK3CA-mutant cells, respectively (Release 3, November 2012; http://www.cancerrxgene.org/; (5)(41)). In particular, however, PTEN-deficient prostate cancer, breast cancer and glioblastoma cell lines have been shown to be responsive to PIK3CB silencing and p110β inhibitor treatment in vitro and in vivo(17, 18). Our results fail to corroborate these observations in EEC cell lines, as single-agent treatment with the three different p110β selective inhibitors tested (i.e. GSK2636771, AZD6482 and TGX-221) and the p110α inhibitor A66 did not sensitize EEC cells. This is not entirely unexpected and may be the resultant of the epistatic interactions between PTEN loss-of-function and PIK3CA gain-of-function mutations, which are frequently observed concurrently in EECs, and that the EEC cell lines studied here expressed both p110α and p110β at protein levels. Our results are consistent with the findings that sustained inhibition of selected p110 isoforms allows for functional redundancy of class IA PI3K isoforms(42), that inactivation of either p110α or p110β may counteract the impact of PTEN loss(43), and that inhibition of p110α/p110δ (PI3Ki-A/D) isoforms do exert effects on cell viability in subsets of PTEN-deficient cell lines and xenografts (non-EEC)(44). Given that activating genetic alterations targeting the PI3K pathway frequently co-occur with PTEN loss-of-function in EECs and that here we demonstrate that p110β inhibition alone may not be sufficient to sensitize PTEN-mutant EEC cells, our results suggest that combination of p110β inhibitors with other targeted agents may be required to increase efficacy. On the other hand, it is plausible that p110α inhibition may increase sensitivity of PIK3CA-mutant EEC cells to other agents targeting different components of the PI3K pathway or parallel pathways.

The limitations of this study include the analysis of cancer cell lines in vitro only, and the focus on the most commonly mutated PI3K pathway genes for their association with targeted therapy response in the EEC cell lines. With the ongoing next generation sequencing efforts unraveling the entire mutational repertoire of primary endometrial cancers, additional genetic alterations may be identified in subgroups of the disease that may play a role determining response to PI3K pathway inhibitors. In summary, we observed that targeted pan-PI3K and mTOR inhibition in EEC cell lines may be most effective in PIK3CA and PTEN-mutant cells, respectively, and that these PI3K inhibitors may even be effective in a subset of EEC cells concurrently harboring KRAS mutations. In addition, our data suggest that benefit from p110β inhibitors in PTEN-deficient EEC may be limited given the frequent coexistence of activating PIK3CA mutations. As other p110 isoform-specific inhibitors, in particular p110δ inhibitors, showed unexpected clinical efficacy due to effects on the tumor microenvironment(45), results from clinical trials are eagerly awaited.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

The PI3K pathway is activated in the majority of endometrioid endometrial cancers (EECs) and its inhibition is of great therapeutic interest. Incorporation of predictive biomarkers in clinical trial design is likely to play an important role in the successful development of targeted therapeutics. Our study provides support for the potential use of PIK3CA and PTEN mutation profiling in clinical trials to guide selection of EEC patients likely to benefit from pan-PI3K and allosteric mTOR inhibition, respectively. Our data further suggest that the presence of activating KRAS mutations in EECs harboring PIK3CA and/ or PTEN mutations does not necessarily result in resistance to PI3K pathway inhibition. p110β-specific inhibitors are in clinical development for PTEN-deficient tumors, including EECs. Our data provide evidence to suggest that p110β inhibition alone may not be sufficient to mediate growth-inhibition in PTEN-mutant EECs, as, contrary to breast cancer, activating PI3K pathway mutations often coexist.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Equipment Park (CRUK LRI) and Lucy Hill (Queen Mary University of London) for Sanger sequencing assistance, Cell Services Facility (CRUK Clare Hall) for STR profiling of cell lines, and Ming Jiang (HTS laboratory, CRUK LRI) for transfection reagent testing. We thank Miriam Molinas Arcas (CRUK LRI) for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Financial support: This work was funded by Cancer Research UK.

Footnotes

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS: Concept and design: B. Weigelt, J.S. Reis-Filho, J. Downward

Development of methodology: B. Weigelt, P.H. Warne, M.B. Lambros

Acquisition of data: B. Weigelt, P.H. Warne, M.B. Lambros

Analysis and interpretation of data: B. Weigelt, P.H. Warne, M.B. Lambros, J.S. Reis-Filho, J. Downward

Writing and review of the manuscript: B. Weigelt, J.S. Reis-Filho, J. Downward

Study supervision: J. Downward

Conflict of interest: the authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creasman WT, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Quinn MA, Beller U, Benedet JL, et al. Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(Suppl 1):S105–43. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983;15:10–7. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(83)90111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garnett MJ, Edelman EJ, Heidorn SJ, Greenman CD, Dastur A, Lau KW, et al. Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature. 2012;483:570–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang H, Cheung LW, Li J, Ju Z, Yu S, Stemke-Hale K, et al. Whole-exome sequencing combined with functional genomics reveals novel candidate driver cancer genes in endometrial cancer. Genome Res. 2012 doi: 10.1101/gr.137596.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McConechy MK, Ding J, Cheang MC, Wiegand KC, Senz J, Tone AA, et al. Use of mutation profiles to refine the classification of endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol. 2012;228:20–30. doi: 10.1002/path.4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oda K, Stokoe D, Taketani Y, McCormick F. High frequency of coexistent mutations of PIK3CA and PTEN genes in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10669–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung LW, Hennessy BT, Li J, Yu S, Myers AP, Djordjevic B, et al. High frequency of PIK3R1 and PIK3R2 mutations in endometrial cancer elucidates a novel mechanism for regulation of PTEN protein stability. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:170–85. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urick ME, Rudd ML, Godwin AK, Sgroi D, Merino M, Bell DW. PIK3R1 (p85alpha) is somatically mutated at high frequency in primary endometrial cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4061–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudd ML, Price JC, Fogoros S, Godwin AK, Sgroi DC, Merino MJ, et al. A unique spectrum of somatic PIK3CA (p110alpha) mutations within primary endometrial carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1331–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weigelt B, Downward J. Genomic Determinants of PI3K Pathway Inhibitor Response in Cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:109. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slomovitz BM, Coleman RL. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway as a Therapeutic Target in Endometrial Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5856–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janku F, Tsimberidou AM, Garrido-Laguna I, Wang X, Luthra R, Hong DS, et al. PIK3CA mutations in patients with advanced cancers treated with PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:558–65. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Nicolantonio F, Arena S, Tabernero J, Grosso S, Molinari F, Macarulla T, et al. Deregulation of the PI3K and KRAS signaling pathways in human cancer cells determines their response to everolimus. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2858–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI37539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janku F, Wheler JJ, Westin SN, Moulder SL, Naing A, Tsimberidou AM, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors in patients with breast and gynecologic malignancies harboring PIK3CA mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:777–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wee S, Wiederschain D, Maira SM, Loo A, Miller C, deBeaumont R, et al. PTEN-deficient cancers depend on PIK3CB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13057–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802655105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ni J, Liu Q, Xie S, Carlson C, Von T, Vogel K, et al. Functional characterization of an isoform-selective inhibitor of PI3K-p110beta as a potential anticancer agent. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:425–33. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia S, Liu Z, Zhang S, Liu P, Zhang L, Lee SH, et al. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110beta in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2008;454:776–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SH, Poulogiannis G, Pyne S, Jia S, Zou L, Signoretti S, et al. A constitutively activated form of the p110beta isoform of PI3-kinase induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11002–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005642107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samuels Y, Diaz LA, Jr., Schmidt-Kittler O, Cummins JM, Delong L, Cheong I, et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:561–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weigelt B, Warne PH, Downward J. PIK3CA mutation, but not PTEN loss of function, determines the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to mTOR inhibitory drugs. Oncogene. 2011;30:3222–33. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambros MB, Wilkerson PM, Natrajan R, Patani N, Pawar V, Vatcheva R, et al. High-throughput detection of fusion genes in cancer using the Sequenom MassARRAY platform. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1491–501. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner N, Lambros MB, Horlings HM, Pearson A, Sharpe R, Natrajan R, et al. Integrative molecular profiling of triple negative breast cancers identifies amplicon drivers and potential therapeutic targets. Oncogene. 2010;29:2013–23. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Brien C, Wallin JJ, Sampath D, GuhaThakurta D, Savage H, Punnoose EA, et al. Predictive biomarkers of sensitivity to the phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase inhibitor GDC-0941 in breast cancer preclinical models. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3670–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molina-Arcas M, Hancock DC, Sheridan C, Kumar MS, Downward J. Coordinate direct input of both KRAS and IGF1 receptor to activation of PI 3-kinase in KRAS mutant lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0446. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steckel M, Molina-Arcas M, Weigelt B, Marani M, Warne PH, Kuznetsov H, et al. Determination of synthetic lethal interactions in KRAS oncogene-dependent cancer cells reveals novel therapeutic targeting strategies. Cell Res. 2012;22:1227–45. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stemke-Hale K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lluch A, Neve RM, Kuo WL, Davies M, et al. An integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of PIK3CA, PTEN, and AKT mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6084–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar MS, Hancock DC, Molina-Arcas M, Steckel M, East P, Diefenbacher M, et al. The GATA2 transcriptional network is requisite for RAS oncogene-driven non-small cell lung cancer. Cell. 2012;149:642–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh A, Greninger P, Rhodes D, Koopman L, Violette S, Bardeesy N, et al. A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens PJ, Tarpey PS, Davies H, Van Loo P, Greenman C, Wedge DC, et al. The landscape of cancer genes and mutational processes in breast cancer. Nature. 2012;486:400–4. doi: 10.1038/nature11017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brachmann SM, Hofmann I, Schnell C, Fritsch C, Wee S, Lane H, et al. Specific apoptosis induction by the dual PI3K/mTor inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 in HER2 amplified and PIK3CA mutant breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22299–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905152106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka H, Yoshida M, Tanimura H, Fujii T, Sakata K, Tachibana Y, et al. The selective class I PI3K inhibitor CH5132799 targets human cancers harboring oncogenic PIK3CA mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3272–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoji K, Oda K, Kashiyama T, Ikeda Y, Nakagawa S, Sone K, et al. Genotype-dependent efficacy of a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, NVP-BEZ235, and an mTOR inhibitor, RAD001, in endometrial carcinomas. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tredan O, Treilleux I, Wang Q, Gane N, Pissaloux D, Bonnin N, et al. Predicting everolimus treatment efficacy in patients with advanced endometrial carcinoma: a GINECO group study. Target Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11523-012-0242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oza AM, Elit L, Tsao MS, Kamel-Reid S, Biagi J, Provencher DM, et al. Phase II study of temsirolimus in women with recurrent or metastatic endometrial cancer: a trial of the NCIC Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3278–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Hara AJ, Bell DW. The genomics and genetics of endometrial cancer. Adv Genomics Genet. 2012;2012:33–47. doi: 10.2147/AGG.S28953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashworth A, Lord CJ, Reis-Filho JS. Genetic interactions in cancer progression and treatment. Cell. 2011;145:30–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–3. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang W, Soares J, Greninger P, Edelman EJ, Lightfoot H, Forbes S, et al. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D955–61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foukas LC, Berenjeno IM, Gray A, Khwaja A, Vanhaesebroeck B. Activity of any class IA PI3K isoform can sustain cell proliferation and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11381–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906461107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berenjeno IM, Guillermet-Guibert J, Pearce W, Gray A, Fleming S, Vanhaesebroeck B. Both p110alpha and p110beta isoforms of PI3K can modulate the impact of loss-of-function of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Biochem J. 2012;442:151–9. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edgar KA, Wallin JJ, Berry M, Lee LB, Prior WW, Sampath D, et al. Isoform-specific phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors exert distinct effects in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1164–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fruman DA, Rommel C. PI3Kdelta inhibitors in cancer: rationale and serendipity merge in the clinic. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:562–72. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.