Abstract

This research examined the reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility to parents and disclosure to them during early adolescence in the United States and China. Four times over the seventh and eighth grades, 825 American and Chinese youth (mean age = 12.73 years) reported on their sense of responsibility to parents and disclosure of everyday activities to them. Auto-regressive Latent Trajectory (ALT) models revealed that the more youth felt responsible to parents, the more they subsequently disclosed to them in both the United States and China. The reverse was also true: The more youth disclosed to parents, the more responsible they felt to them over time. The strength of these reciprocal pathways increased as youth progressed through early adolescence.

Keywords: Culture, disclosure, parent-child relationships, sense of responsibility

A growing body of research points to the significance of youth's disclosure to parents for their psychological adjustment during adolescence (e.g., Cheung, Pomerantz, & Dong, in press; Keijsers, Branje, VanderValk, & Meeus, 2010; Kerr & Stattin, 2000). Youth's disclosure appears to protect them against adjustment problems over and above parents’ active monitoring attempts – for example, their solicitation of information (e.g., Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Stattin & Kerr, 2000; Kerr, Stattin, & Burk, 2010). Thus, a key issue is that of what leads youth to disclose. The current research focused on the role of youth's sense of responsibility to parents – that is, youth's belief that it is important to assist parents psychologically or materially (e.g., by meeting parents’ expectations in school). The goal was to evaluate whether there are reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents, such that each facilitates the other, thereby mutually maintaining one another. Variations in these reciprocal pathways due to youth's development as well as culture were also examined.

Reciprocal Pathways between Youth's Sense of Responsibility and Disclosure

Because youth may see disclosure as an important way to fulfill their responsibilities to parents, their sense of responsibility to parents may support their disclosure to them. Youth may believe that parents have the right to know about their life, and thus feel they have a duty to tell parents what they are doing (Smetana, Metzger, Gettman, & Campione-Barr, 2006). To show respect to parents youth may tell parents about their lives even when parents do not solicit such information. Youth with a heightened sense of responsibility to parents may also disclose to show parents that they are responsible. For example, they may let parents know that instead of hanging out with friends, they studied. Even if youth are not fulfilling their responsibilities, they may demonstrate their intentions to do so in the future, emphasizing their efforts in this vein, through disclosure.

Youth's disclosure to parents may also contribute to their sense of responsibility, such that the two reciprocally shape one another over time. The conversations that ensue from youth's disclosure may afford parents the opportunity to provide positive feedback when youth have been responsible and negative feedback when they have not; in so doing, parents may communicate what it means to be responsible to parents. For example, when youth voluntarily tell parents that they are having difficulty with schoolwork, parents may take the opportunity to emphasize that being responsible involves heightened efforts to overcome their difficulty. Given that youth initiate the interactions by disclosing, they may be particularly receptive to messages from parents about being responsible.

Thus, reciprocal pathways may exist such that youth's sense of responsibility to parents fosters their disclosure to parents, which in turn shapes youth's sense of responsibility, with the two maintaining one another over time. Although there is no direct evidence for such reciprocal pathways over time, there is some suggestive evidence. In a concurrent study, Yau, Tasopoulos-Chan, and Smetana (2009) found that the more American youth of European, Chinese, and Mexican descent felt obligated to the family, the more they disclosed to parents.

Developmental and Cultural Considerations

The reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents may vary with development as well as culture. As youth mature, they may form a more elaborate understanding of what it means to be responsible to parents, such that they come to view disclosing to parents as one of their responsibilities. This is particularly likely, given that youth's time away from parents increases over adolescence (e.g., Larson & Richards, 1991; Larson, Richards, Moneta, Holmbeck, & Duckett, 1996) and disclosure is the primary source of parents’ knowledge about youth's lives (e.g., Stattin & Kerr, 2000; Masche, 2010). Conversely, parents may deem it more appropriate to cultivate a sense of responsibility among youth as they become more capable of making decisions and putting them into action. Moreover, as youth's involvement in the world outside the family increases, parents may attempt to ensure that youth balance it with fulfilling their responsibilities to them. Hence, over early adolescence, the reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents may become stronger.

Culture may also create variability. American adolescence is generally marked by youth's establishing independence from parents (Collins & Steinberg, 2006). In China, however, given the import of filial piety (Ho, 1996; Wang & Hsueh, 2000), there may be more of a focus on youth's fulfilling their responsibilities to parents (Pomerantz, Qin, Wang, & Chen, 2011). Consequently, it is possible that American (vs. Chinese) youth are less likely to see disclosure as a way of fulfilling their responsibilities to parents given that disclosure may interfere with their independence from parents. When youth do disclose, American parents may not emphasize issues regarding responsibility to parents to the same extent as Chinese parents who may be influenced by filial piety concerns. However, it is also possible that in both countries, once youth have a sense of responsibility to parents, they feel it is their duty to disclose to them, with American and Chinese parents similarly emphasizing responsibility as it is likely an important socialization goal for both.

The Current Research

The aim of the current research was to examine whether there are reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents over time. To this end, we followed American and Chinese youth across four waves of assessment during early adolescence (i.e., the seventh and eighth grades). At each wave, youth reported on two forms of their sense of responsibility to parents: Feelings of obligation to parents (e.g., sense of duty to spend time with parents) and parent-oriented motivation in school (e.g., desire to do well in school to meet parents's expectations). Both revolve around youth's concern with taking parents’ wishes into consideration. Notably, because not all parents see achievement in school as a priority not all youth seek to fulfill their responsibilities to parents academically (Hardway & Fuligni, 2006). Indeed, the two forms overlap, but not to such an extent that they are redundant with one another (Pomerantz et al., 2011).

Youth also reported on their disclosure at each of the four waves. It was anticipated that youth's sense of responsibility to parents would predict their disclosure to them over time, which in turn would predict their sense of responsibility. When examining these reciprocal pathways, we took into account the quality of youths’ relationships with parents given its sizable positive associations with youth's sense of responsibility to parents as well as disclosure to them (e.g., Cheung et al., in press; Pomerantz et al., 2011). The strength of the reciprocal pathways was expected to increase as youth moved through early adolescence.

Method

Participants

Participants were 374 (187 boys) American seventh graders (mean age = 12.78 years, SD = .34, in the fall semester of seventh grade) and 451 (240 boys) Chinese seventh graders (mean age = 12.69 years, SD = .46, in the fall semester of seventh grade) who took part in the University of Illinois US-China Adolescence Study (e.g., Qin, Pomerantz, & Wang, 2009). Youth were from primarily working- and middle-class suburbs of major cities (i.e., Chicago and Beijing). Reflecting the ethnic composition of the areas in which they resided, American youth were primarily European American (88%), with 9% Hispanic American, 2% African American, and 1% Asian American. Over 95% of the residents in the areas in which Chinese youth resided were of the Han ethnicity (Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics, 2005), which is the majority ethnicity in China.

Procedure

Beginning in the fall of seventh grade, youth completed questionnaires every six months until the end of eighth grade. In total, there were four waves of data collection: Fall (Wave 1) and spring (Wave 2) of seventh grade, and fall (Wave 3) and spring (Wave 4) of eighth grade. A trained native research assistant read the instructions and items aloud to youth in their native language in the classroom; youth responded on their own using various rating scales. Attrition over the entire study was 4% (6% in China and 2% in the United States). Ninety-four percent of youth had the data required for all the analyses at three or more waves of the study. At Wave 1, youth with no missing data did not differ from those with missing data in regard to any of the constructs included in this report.

Measures

The measures were initially created in English. To generate the Chinese versions, standard translation and back-translation procedures (Brislin, 1980) were employed with repeated discussions among American and Chinese research team members to modify wording to ensure equivalence in meaning (Erkut, 2010). Equivalence was also established in a series of two-group Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs) conducted in the context of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Given our focus on comparing associations, these analyses evaluated factorial invariance of the measures between the two countries and over the four waves of the study. For each measure, an unconstrained model in which all the parameters were freely estimated was compared with constrained models in which the factor loadings were forced to be equal between the United States and China and over the four waves. In previous analyses of this dataset, the measures used here were found to possess factorial equivalence (Cheung et al., in press; Pomerantz et al., 2011; Pomerantz, Qin, Wang, & Chen, 2009): The models fit well, CFIs > .98, TLIs > .96, RMSEAs < .05, χ2s < 84, with the differences in the TLIs and RMSEAs between the unconstrained and constrained models less than .01, thereby meeting the criteria establish by Chen (2007) and Cheung and Rensvold (2002). The validity of the measures is also similar in the United States and China (e.g., Cheung et al., in press; Pomerantz et al., 2011).

Sense of responsibility to parents

Youth's feelings of obligation to parents were assessed with four items from Fuligni and colleagues’ (1999) measure of family obligation and five from Ng, Loong, Liu, and Weatherall's (2000) measure. For each of the nine items (e.g., “How much do you feel you should spend time at home with your parents?”), youth indicated how much (1 = not at all; 5 = very much) they should engage in the activity described (αs = .85 to .93 in the United States and .81 to .88 in China).

Youth's parent-oriented motivation in school was assessed with six of the items from Dowson and McInerney's (2004) social approval and responsibility scales modified so that they referred to parents; six additional items were also created (Pomerantz et al., 2011). For each of the 12 reasons about why they try to do well at school (e.g., “To show my parents that I am being responsible.”), youth indicated how true it was of them (1 = not at all true, 5 = very true; αs = .92 to .95 in the United States and .90 to .94 in China). As reported by Pomerantz and colleagues (2011), the two forms of youth's sense of responsibility were positively associated within each wave (rs = .21 to .49 in the United States and .34 to .45 in China, ps < .001).

Disclosure to parents

Youth's spontaneous disclosure to parents was assessed with five of the items from Kerr and Stattin's measure (2000; see also Stattin & Kerr, 2000) with slight modifications to make the items more concrete and ensure it was clear that youth initiated the disclosure. We also created five additional items to ensure the assessment of the sharing and withholding of information on a broad range of issues (e.g., friends, whereabouts, and academics). Youth indicated how true (1 = not at all true of me; 5 = very true of me) each of the 10 items (e.g., “I often start a conversation with my parents about what happens in school.”) was of them (αs = .85 to .86 in the United States and .82 to .87 in China).

Parent-child relationship quality

The quality of youth's relationships with parents was assessed with 24 items from the Inventory of Parent Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). The measure asks about the extent to which youth trust parents, feel they can communicate with them, and are alienated from them (e.g., “My parents can tell when I'm upset about something.”). Youth indicated how true (1 = not at all true; 5 = very true) each item was of them (αs = .79 to .82 in the United States and .80 to .82 in China).

Results

Analysis Overview

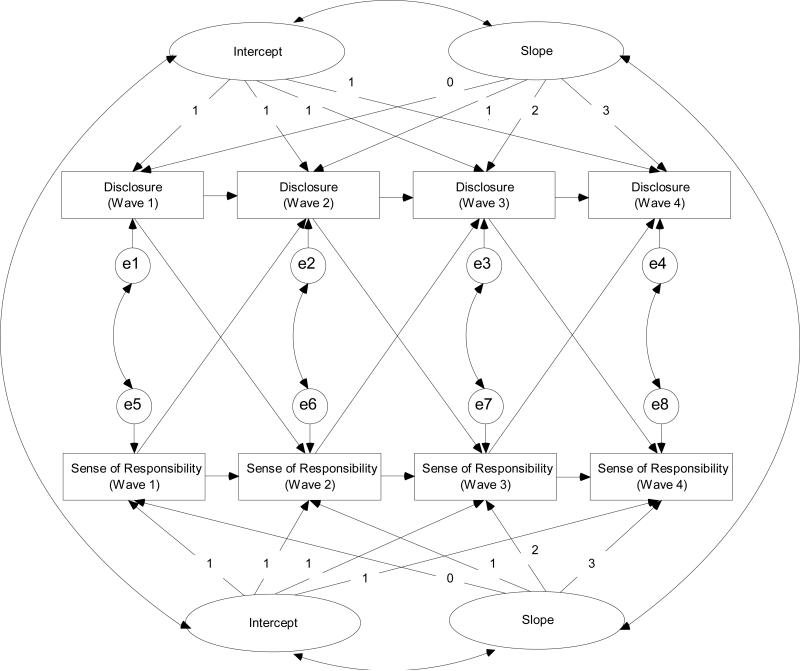

The reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents were examined with Auto-regressive Latent Trajectory (ALT) models (e.g., Bollen & Curran, 2004, 2006; Bollen & Zimmer, 2010) using AMOS 17.0 (Arbuckle, 1995-2008). Missing data was handled with Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimates. As shown in Figure 1, the ALT model combines a bivariate latent trajectory model and an auto-regressive model. The bivariate latent trajectory portion of the model includes latent intercept and slope factors of the growth trajectories of youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents, which are allowed to correlate with one another. The auto-regressive portion of the ALT model includes paths of six-month stability for youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure, within-wave covariance between the two, and cross-lag paths from the fall of seventh grade to the spring of eighth grade with six-month intervals. By such specification, the cross-lag paths capture the reciprocal pathways between responsibility and disclosure, while controlling for the concurrent associations between the two as well as the stability of each. Because the ALT model combines the bivariate latent trajectory and auto-regressive models, it takes into account the underlying shared trajectory of responsibility and disclosure over time. The model thus rules out the possibility that lagged effects are due to associated change that may be driven by third variables. Consequently, the ALT model provides more accurate estimates of the cross-lag associations than does the autoregressive model on its own (Bollen & Zimmer, 2010; Curran & Bollen, 2001).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the Auto-regressive Latent Trajectory (ALT) model examining the reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents. Note. Although correlations between the intercept (slope) of sense of responsibility to parents and the slope (intercept) of disclosure to parents were included in the model, they are not shown here for ease of presentation. The two forms of youth's sense of responsibility to parents (i.e., feelings of obligation to parents and parent-oriented motivation in school) were examined in separate models.

Given the complexity of the ALT model, the three six-month stability paths for each construct in the model were constrained to be equal to one another (e.g., the paths for disclosure from Wave 1 to 2, Wave 2 to 3, and Wave 3 to 4 were forced to be equal to each other) to avoid converging difficulty (Bollen & Curran, 2004; for a similar approach, see Williams & Steinberg, 2011); this model served as the baseline model. The analyses were conducted in two steps. First, the ALT models – one for each form of youth's sense of responsibility to parents – were fit for the whole sample. In examining the reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure, we evaluated whether they became stronger over the four waves by comparing the baseline model in which all the cross-lag paths were freely estimated to constrained models in which adjacent pairs of cross-lag paths in a single direction were constrained to be equal to one another (e.g., the paths for responsibility at Wave 1 to disclosure at Wave 2, responsibility at Wave 2 to disclosure at Wave 3, and responsibility at Wave 3 to disclosure at Wave 4 were forced to be equal to each other).

Second, two-group SEM comparison procedures were used to test for country differences in the strength of each cross-lag path. In addition, some studies have found that youth's disclosure to parents is differentially associated with their connectedness to parents among boys and girls (Daddis & Randolph, 2010; Keijsers, Branje, Frijns, Finkenauer, & Meeus, 2010), whereas others have not (e.g., Keijsers, Branje, VanderValk et al., 2010; Masche, 2010; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, Luyckx, & Goossens, 2006). Thus, we also examined gender differences in the reciprocal pathways. A baseline model in which all the cross-lag paths were freely estimated was compared to constrained models in which the cross-lag paths were specified to be equal one by one between the United States and China or boys and girls.

Are there Reciprocal Pathways between Youth's Sense of Responsibility and Disclosure?

As shown in Table 1, the baseline ALT model for each form of youth's sense of responsibility (i.e., feelings of obligation to parents and parent-oriented motivation in school) and disclosure to parents fit the data well. With the exception of the Wave 1 to 2 paths, consistent with expectations, the more responsible youth felt to parents, the more they disclosed to them six months later (see Table 2). Indicative of reciprocal pathways, it was also the case that, with the exception of the Wave 1 to 2 paths, the more youth disclosed, the greater their subsequent feelings of obligation and parent-oriented motivation.

Table 1.

Model Fit Indexes and Comparisons

| Model Fit Indexes |

Comparison to Baseline Model |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | df | χ 2 | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Δdf | Δ χ 2 |

| Model 1: Feelings of obligation and disclosure | |||||||

| Baseline modela | 10 | 9.09 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .00 | ||

| Obligation → Disclosure paths constrainedb | 12 | 35.66*** | 0.99 | 0.98 | .05 | 2 | 26.58*** |

| Disclosure → Obligation paths constrainedc | 12 | 28.19*** | 1.00 | 0.99 | .04 | 2 | 19.11*** |

| Model 2: Parent-oriented motivation and disclosure | |||||||

| Baseline modela | 10 | 42.28*** | 0.99 | 0.96 | .06 | ||

| Obligation → Disclosure paths constrainedb | 12 | 63.22*** | 0.98 | 0.95 | .07 | 2 | 20.94*** |

| Disclosure → Obligation paths constrainedc | 12 | 54.65*** | 0.99 | 0.96 | .07 | 2 | 12.37** |

Note. N = 825.

The three stability paths for each of the constructs were constrained to be equal to one another, but otherwise there were no constraints (for the full model, see Figure 1).

In addition to the constraints of the baseline model, the three cross-lag paths in which sense of responsibility predicts disclosure six months later were constrained to be equal to one another.

In addition to the constraints of the baseline model, the three cross-lag paths in which disclosure predicts sense of responsibility six months later were constrained to be equal to one another.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 2.

Reciprocal Pathways Between Youth's Sense of Responsibility and Disclosure to Parents

| Model | Wave 1 → Wave 2 |

Wave 2 → Wave 3 |

Wave 3 → Wave 4 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Model 1: Feelings of obligation and disclosure | |||||||||

| Obligation → Disclosure | .02 | .03 | .01 | .15 | .05 | .12*** | .27 | .07 | .21*** |

| Disclosure → Obligation | -.03 | .03 | -.03 | .09 | .04 | .13* | .18 | .07 | .22** |

| Model 2: Parent-oriented motivation and disclosure | |||||||||

| POM → Disclosure | -.02 | .02 | -.02 | .08 | .03 | .09** | .17 | .05 | .18** |

| Disclosure → POM | .03 | .03 | .03 | .16 | .06 | .15** | .26 | .09 | .24** |

The models constraining the three paths (i.e., Wave 1 to 2, Wave 2 to 3, and Wave 3 to 4) from each form of youth's sense of responsibility to their disclosure to parents to be equal to one another over time fit worse than the baseline models (see Table 1), indicating that the strength of these paths was unequal. Further analyses revealed that the effects of feelings of obligation and parent-oriented motivation on disclosure became stronger over time, such that the effects from Wave 1 to 2 were weaker than those from Wave 2 to 3, Δχ2s > 20, ps < .001, which were weaker than those from Wave 3 to 4, Δχ2s > 12, ps < .001. Similarly, the effects of youth's disclosure on their sense of responsibility were not equal over time, as the models constraining these paths to be equal over time fit worse than the baseline models. The effects of youth's disclosure on their feelings of obligation and parent-oriented motivation from Wave 1 to 2 were weaker than those from Wave 2 to 3, Δχ2s > 12, ps < .001, which were weaker than those from Wave 3 to 4, Δχ2s > 8, ps < .01.

By adjusting for associated changes between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents, the ALT model takes a step toward ruling out the possibility that the reciprocal pathways are due to third variables. However, because the quality of youth's relationships with parents is associated with youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents, we took an additional step to exclude it as an alternative explanation. Relationship quality at each of the four waves was added to the ALT models described earlier such that its growth parameters were allowed to correlate with those for sense of responsibility and disclosure. Also included were paths of six-month stability in relationship quality, within-wave covariance, and cross-lag paths between relationship quality and the other two constructs from the fall of seventh grade to the spring of eighth grade with six-month intervals. The effects identified earlier remained with the exception that the effect of disclosure on sense of responsibility from Wave 3 to 4 was no longer reliable (standardized coefficients = .18 for feelings of obligation and .11 for parent-oriented motivation, ns). Notably, at none of the waves was relationship quality predictive of youth's sense of responsibility or disclosure to parents six months later (standardized coefficients = -.07 to .18, ns).

Do the Reciprocal Pathways Vary by Youth's Country or Gender?

Two-group model comparison indicated that the reciprocal pathways were similarly evident in the United States and China, Δχ2s < 1.42, ns. The paths were also similarly evident among girls and boys, Δχ2s < 3.6, ns. Although the path from youth's feelings of obligation at the first wave to their disclosure six months later significantly differed between boys and girls, Δχ2 = 5.51, p < .05, the meaning was unclear given that this path was not reliable for either gender (standardized coefficients = .00, ns).

Discussion

Despite the import of youth's disclosure to parents to their psychological adjustment during adolescence (e.g., Stattin & Kerr, 2000; Keijsers, Branje, VanderValk, et al., 2010; Laird & Marrero, 2010), relatively little is known as to what leads youth to disclose. The goal of the current research was to identify the role of youth's sense of responsibility to parents in their disclosure to them. Following youth four times over two years as they made their way through early adolescence, the current research provided an optimal context for identifying the reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents. In the United States and China, both boys and girls’ sense of responsibility predicted their heightened disclosure over time. Their disclosure also predicted their heightened sense of responsibility over time suggesting a process of mutual maintenance between the two over the initial adolescent years. Notably, these reciprocal pathways were not simply due to the quality of youth's relationships with parents.

The reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents were evident for both forms of sense of responsibility we examined – feelings of obligation to parents and parent-oriented motivation in school. Moreover, when we conducted additional analyses with both forms in a single ALT model, the reciprocal pathways with disclosue remained for both. Thus, it appears that whether youth's sense of responsibility manifests itself in general feelings of obligation to parents or an orientation toward parents in the specific arena of academics, it is likely instrumental in fostering disclosure among youth. Given that the reciprocal pathways became stronger over the early adolescent years, efforts to support youth in developing a sense of responsibility to parents – either in terms of feelings of obligation to parents or parent-oriented motivation in school – as they enter adolescence may protect youth from the common downward trajectory in their disclosure to parents in the two countries (e.g., Cheung et al., in press; Keijsers et al., 2009; Masche, 2010).

Several limitations of the current research necessitate interpreting the findings with caution. For one, parents and youth view youth as more obligated to disclose about prudential than personal issues (Smetana et al., 2006), but our disclosure measure did not distinguish between these two domains – or others such as the conventional and moral that may be important. Consequently, it was not possible to examine if youth's sense of responsibility to parents carries with it the duty to disclose in some domains more than the others. For example, when youth disclose about the prudential domain, parents may make greater efforts to cultivate a sense of responsibility among youth than when they disclose about the personal domain. In addition, our disclosure measure did not distinguish between disclosure and secrecy. Given that the two are differentially predictive of youth's adjustment (e.g, Frijns, Keijsers, Branje, & Meeus, 2010), it would be fruitful for future research to examine whether they have similar reciprocal pathways with youth's sense of responsibility to parents.

Lastly, the samples used in the current research do not represent the diversity of the United States and China. This leaves open questions about variability within the two countries (e.g., ethnic and geographic differences) in the reciprocal pathways between youth's sense of responsibility and disclosure to parents. Given that urban areas in China, such as Beijing where the research was conducted, have been increasingly exposed to Western values in the past few decades, it is unclear to what extent the findings of this research are generalizable to less urban areas in China. Despite these limitations, the current research supports the idea that youth's sense of responsibility to parents maintains their disclosure to them during the early adolescent years when it is often prone to decline.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01 MH57505. We are grateful to the children who participated. We thank Huichang Chen, Scott Litwack, Molly McDonald, and Haimei Wang for their help in collecting and managing the data. We appreciate the constructive comments provided by members of the Center for Parent-Child Studies at University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Contributor Information

Lili Qin, Department of Psychology, National University of Singapore..

Eva M. Pomerantz, Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

References

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 17.0 user's guide. Amos Development Corporation; Chicago: 1995-2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics [August 18, 2008];Beijing statistical yearbook 2005. 2005 from http://www.bjstats.gov.cn/tjnj/2005-tjnj/

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) models: A synthesis of two traditions. Sociological Methods & Research. 2004;32:336–383. DOI: 10.1177/0049124103260222. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models. Wiley; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Zimmer C. An overview of the Autoregressive Latent Trajectory (ALT) model. In: van Montfort K, Oud JHL, Satorra A, editors. Longitudinal research with latent variables. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 2010. pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In: Triandis HC, Berry JW, editors. Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Vol. 2, Methodology. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 1980. pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Chen FF. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:464–504. DOI: 10.1080/10705510701301834. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung S, Pomerantz EM, Dong W. Does adolescents’ disclosure to their parents matter for their academic adjustment? Child Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01853.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. DOI: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Hoboken, NJ: 2006. pp. 1003–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bollen KA. The best of both worlds: Combining autoregressive and latent curve models. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, US: 2001. pp. 107–135. [Google Scholar]

- Daddis C, Randolph D. Dating and disclosure: Adolescent management of information regarding romantic involvement. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.002. DOI: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowson M, McInerney DM. The development and validation of the goal orientation and learning strategies survey (GOALS-S). Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2004;64:290–310. DOI: 10.1177/0013164403251335. [Google Scholar]

- Erkut S. Developing multiple language versions of instruments for intercultural research. Child Development Perspectives. 2010;4:19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00111.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijns T, Keijsers L, Branje S, Meeus W. What parents don't know and how it may affect their children: Qualifying the disclosure-adjustment link. Journal of adolescence. 2010;33:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.010. DOI: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligation among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American family obligation among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European American backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [Google Scholar]

- Ho DYF. Filial piety and its psychological consequences. In: Bond MH, editor. Handbook of Chinese psychology. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Keijsers L, Branje SJT, Frijns T, Finkenauer C, Meeus W. Gender differences in keeping secrets from parents in adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:293–298. doi: 10.1037/a0018115. DOI: 10.1037/a0018115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keijsers L, Branje SJT, VanderValk IE, Meeus W. Reciprocal effects between parental solicitation, parental control, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:88–113. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00631.x. [Google Scholar]

- Keijsers L, Frijns T, Branje SJT, Meeus W. Developmental links of adolescent disclosure, parental solicitation, and control with delinquency: Moderation by parental support. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1314–1327. doi: 10.1037/a0016693. DOI: 10.1037/a0016693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:366–380. DOI: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H, Burk WJ. A reinterpretation of parental monitoring in longitudinal perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:39–64. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00623.x. [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Marrero MD. Information management and behavior problems: Is concealing misbehavior necessarily a sign of trouble? Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.018. DOI: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Richards MH. Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: Changing developmental contexts. Child Development. 1991;62:284–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01531.x. DOI: 10.2307/1131003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Richards MH, Moneta G, Holmbeck G, Duckett E. Changes in adolescents’ daily interactions with their families from ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:744–754. DOI: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.744. [Google Scholar]

- Masche JG. Explanation of normative declines in parents’ knowledge about their adolescent children. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:271–284. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.08.002. DOI: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SH, Loong CSF, Liu JH, Weatherall A. Will the young support the old? An individual- and family-level study of filial obligations in two New Zealand cultures. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;3:163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz EM, Qin L, Wang Q, Chen H. American and Chinese early adolescents’ inclusion of their relationships with their parents in their self-construals. Child Development. 2009;80:792–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01298.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz EM, Qin L, Wang Q, Chen H. Changes in early adolescents’ sense of responsibility to their parents in the United States and China: Implications for their academic functioning. Child Development. 2011;82:1136–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01588.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Pomerantz EM, Wang Q. Are gains in decision-making autonomy during early adolescence beneficial for emotional functioning? The case of the United States and China. Child Development. 2009;80:1705–1721. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01363.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Metzger A, Gettman DC, Campione-Barr N. Disclosure and secrecy in adolescent-parent relationships. Child Development. 2006;77:201–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00865.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Luyckx K, Goossens L. Parenting and adolescent problem behavior: An integrated model with adolescent self-disclosure and perceived parental knowledge as intervening variables. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:305–318. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.305. DOI: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Hsueh Y. Parent-child interdependence in Chinese families: Change and continuity. In: Violato C, Oddone-Paolucci E, Genuis M, editors. The changing family and child development. Ashgate Publishing; Aldershot, England: 2000. pp. 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Williams LR, Steinberg L. Reciprocal relations between parenting and adjustment in a sample of juvenile offenders. Child Development. 2011;82:633–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01523.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau JP, Tasopoulos-Chan M, Smetana JG. Disclosure to parents about everyday activities among American adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 2009;80:1481–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01346.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]