Abstract

Objective To apply a social ecological model to explore the psychosocial factors prospectively associated with longitudinal adherence to antiretroviral treatment in youth perinatally infected with HIV. Methods Randomly selected youth, age 8 to <19 years old, completed cognitive testing and psychosocial questionnaires at baseline as part of a multisite protocol (N = 138). A validated caregiver-report measure of adherence was completed at baseline and 24 and 48 weeks after baseline. Results In multivariate analysis, youth awareness of HIV status, caregiver not fully responsible for medications, low caregiver well-being, adolescent perceptions of poor caregiver–youth relations, caregiver perceptions of low social support, and African American ethnicity were associated with nonadherence over 48 weeks. Conclusions Interventions focusing on caregivers and their interactions with the individual youth and extrafamilial system should be prioritized for prevention and treatment efforts to address nonadherence during the transition into adolescents.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, children, HIV, patient adherence

Most perinatally HIV-infected youth in the United States (currently an estimated 10,000) are aging into adolescence and young adulthood (Hazra, Siberry, & Mofenson, 2010). However, in HIV and in other chronic conditions, adolescents are at higher risk for poorer adherence compared with younger children (Drotar & Levers, 1994; McQuaid, Kopel, Klein, & Fritz, 2003; Mellins, Brackis-Cott, Dolezal, & Abrams, 2004; Williams et al., 2006). Thus, it is critical to develop theory-driven HIV adherence interventions for youth transitioning into adolescence and young adulthood that take into account the multiple contexts within which they are embedded. Social–ecological theory suggests that poor regimen adherence is driven by risk factors across multiple systems, including individual child factors, family factors, and extrafamilial factors (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Kazak, 1989). Indeed, studies of one or two systems have shown pediatric HIV adherence to be related to factors in each of these domains, including child psychological symptoms and awareness of HIV status, child and caregiver disbelief about the need for medications, lower caregiver well-being regardless of caregiver HIV status, low caregiver self-efficacy, worse parent–child relationships, less responsibility for illness management, and being a biological parent or relative (vs. foster or adoptive parent) (Malee et al., 2009, 2011; Simoni et al., 2007). Extrafamilial factors related to antiretroviral treatment (ART) nonadherence include more stressful life events and less social support (Simoni et al., 2007). Although patient–provider relationships are thought to be an important extrafamilial factor (Beach, Keruly, & Moore, 2006), there are few pediatric HIV studies that have assessed this variable.

The literature on factors associated with adherence to treatment of pediatric HIV is largely atheoretical (Simoni et al., 2007). A social ecological model has been recommended for understanding adherence in pediatric chronic illness (Fuemmeler, 2004; Pontali, 2005), but few studies of pediatric HIV simultaneously assessed factors across multiple systems. Only one study to date used this model (Naar-King, Arfken, Frey, et al., 2006), and results were limited by a small sample size from a single site, data collection only from caregivers, and family measures with low reliability. Furthermore, available adherence studies of pediatric HIV have only addressed associations between adherence and psychosocial factors at a single point in time. However, cross-sectional data are limited in explaining causality, and factors associated with sustained adherence are unknown. Thus, the literature is clearly lacking in longitudinal theory-driven studies that can identify factors across multiple systems causally related to sustained adherence. Findings could identify groups at high risk for nonadherence over time and potentially modifiable factors for intervention.

The goal of this exploratory analysis was to identify social ecological factors, by simultaneously assessing multiple factors across multiple systems, which prospectively predict adherence in a multisite cohort of perinatally infected youth. We hypothesized that factors in the individual youth (lower cognitive and behavioral functioning, unawareness of HIV status), in the family system (biological parent, poor caregiver well-being, poor caregiver–child relationships, low caregiver beliefs about HIV severity, and low caregiver responsibility for medication), and in the extrafamilial system (stressful life events, low social support for caregiver and child, and less engagement with medical team) at baseline would be associated with longitudinal nonadherence over the subsequent 48 weeks.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This longitudinal cohort study (N = 138) was based on the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol (PACTG) 1042s, a substudy of PACTG 219C, a long-term observational study that followed large cohorts of HIV-infected (N = 2,869) children throughout the United States from September 2000 through May 2007. Further details regarding 219C and 1042s are available in other publications (Lee, Gortmaker, McIntosh, Hughes, & Oleske, 2006; Nichols et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2006). For P1042s, perinatally infected youth aged 8 to <19 years were randomly selected from P219C and stratified by age (<12 and ≥12 years). An initial list of 280 subjects was randomly selected (simple random sample without replacement) from the entire subset of P219C subjects still under study when P1042S was opened to enrollment and who on record were anticipated to meet eligibility requirements for P1042S when they enroll. A second list of 140 additional patients was later randomly generated to achieve target enrollment.

Eligibility criteria included on ART regimen during study duration with no planned treatment interruption, primary language of English or Spanish, and actively enrolled in P219C, with an age-appropriate Wechsler test for P219C within 3 months of P1042s study entry, so that this assessment would not have to be repeated. Written informed consent was obtained from youth aged 18 and older and from parents or legal guardians of younger youth, with assent also obtained from younger youth.

From the 420 potential caregiver–youth dyads, 99 declined to enroll (25.6%). Sites completed a form requesting reasons for refusal for 72 of the 99 who declined to enroll. Of these 72, 25 caregivers did not volunteer a reason. For the remaining 47, reasons included lack of time (n = 19), lack of interest in research trials (n = 18), and travel difficulties (n = 10). An additional 91 were deemed ineligible, 62 were never approached before study closure, and no information was available for 9. Among the 159 participants who were enrolled in the study, 138 had adherence data at baseline. No significant differences in gender, race/ethnicity, primary caregiver, CD4 count/percent at study entry, or Centers for Disease Control Class C categorization at/before study entry were observed between those with completed data and those without. Participants with missing data (9%) were older (median = 13.1 vs. 12.3 years, p = .04), had a lower percentage of primary caregivers who did not have a high school diploma (31% vs. 64%, p = .03), and had higher viral loads at study entry (median log[RNA] = 4.20 vs. 2.60, p = .008) compared with those with complete data.

Measures

Research nurses asked parents and youth to complete study questionnaires in separate private rooms. Trained site staff members were available to assist with reading when necessary to ensure questionnaire comprehension and completeness. Twelve caregivers completed measures in Spanish. Licensed psychologists or supervised psychometricians administered the cognitive assessment. Eight youth were tested in Spanish.

In addition to demographic characteristics such as gender, age, and ethnicity, data on markers of HIV disease were taken from the PACTG 219C database to describe subject characteristics on enrollment into P1042S. Baseline data on HIV-1 RNA viral load and CD4 percent were based on the available value closest to and within 3 months before study entry into P1042S. Centers for Disease Control classification of disease severity was the most severe classification of the subject before study entry.

Adherence Measure

Whereas multiple measures of adherence to ART medication regimen were used in P1042s, the caregiver-report measure dichotomized as no missed doses in the past month had the strongest association with viral load compared with child report on the same measure, 3-day recalls, and pill counts (Farley et al., 2008). Thus, this measure, collected at baseline, 24 weeks, and 48 weeks, was used in subsequent analyses.

Social Ecological Factors

Individual Factor: Youth Knowledge of HIV Status

Youth awareness of HIV status was assessed by caregiver report (Aware or Unaware).

Individual Factor: Cognitive Functioning

The P219C protocol included administration, every 3 years, of a standardized measure of general cognitive functioning, either the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition (Wechsler, 1991) for children aged 6–16 years or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition (Wechsler, 1997) for youth aged 17 years and older. The analyses for P1042s included the Index score of the full-scale IQ from the age-appropriate Wechsler test administered within 3 months of entry into P1042s.

Individual Factor: Behavioral Functioning

Four indices of behavioral and social–emotional functioning were assessed with the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004): parent report of internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and youth report of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Because the age range of study participants was 8 through <19 years old, the child version was used if the participant was 10 or 11 and the adolescent version was used if the participant was 12 or older. Use of standardized scores (t-scores) rather than raw scores ensured comparability of the measure across the two versions. Internalizing symptoms were represented by the Internalizing composite of the caregiver questionnaire (BASC-PRS) and the Emotional Symptoms Index from the child or adolescent version (BASC-SRP). The Externalizing composite (caregiver report) and the School Maladjustment composite, which assesses the child’s or adolescent’s report of Attitude toward School, Attitude toward Teachers, and Sensation Seeking, captured externalizing symptoms.

Family Factor: Caregiver Well-Being

Caregiver’s well-being (physical and emotional; range: 1–10) in the past month was evaluated with a single self-report item developed for the study and rated on a 10-point scale from feeling the very worst overall (1) to feeling the very best (10).

Family Factor: Caregivers’ Health Beliefs

Caregivers completed an adaptation of the Beliefs About Medication Scale (Riekert & Drotar, 2002) originally developed for asthma and adapted for pediatric HIV (Naar-King, Arfken, Frey, et al., 2006). Items are rated on a 5-point scale from “Really False” (5) to “Really True” (1). The average response to six items that assessed beliefs about health problems associated with HIV disease was used with higher scores indicating greater belief in the severity of the disease. Examples include “My child’s current infection with HIV can lead to serious long-term health problems” and “My child can become very sick as a result of their infection with HIV.” The computed Cronbach alpha of the six items based on data used in this analysis was 0.66.

Family: Caregiver Responsibility for Medication

Caregivers completed an adaptation of the Diabetes Family Responsibility Questionnaire (Anderson, Auslander, Jung, Miller, & Santiago, 1990). They assigned responsibility for four HIV medication tasks to the caregiver alone, to the youth alone, to the youth and caregiver as a shared responsibility, to someone else in the home, or endorsed “nobody really does this.” Medication responsibility is represented as a dichotomous measure in this study (caregiver fully responsible for all four items vs. caregiver not fully responsible), as this measure has been associated with ART adherence (Naar-King et al., 2009).

Family Factor: Child–Caregiver Relationships

The BASC Relations With Parents subscale was used to represent family relationships. Standard scores from the child and adolescent self-report versions were used. Also, caregiver’s relationship to the participant (biological caregiver or relative vs. foster/adoptive parent) was also included in the model.

Extrafamilial Factor: Social Support

Caregiver and youth satisfaction with social support from extended family and friends was rated with a single 4-point scale item developed for the study, from very dissatisfied (1) to very satisfied (4).

Extrafamilial Factor: Stressful Life Events

Caregivers endorsed up to 18 stressful life events in the past 12 months from the PACTG 219C Quality of Life questionnaire.

Extrafamilial Factor: Engagement With Medical Team

As a proxy for engagement with the medical team, caregiver report of the number of phone calls made to the team in the past 4 weeks was included in analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between P1042S subjects included in this analysis and those who were not were done using Fisher exact test or Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables, and using Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. Comparisons between subjects with adherence data at week 48 and who were lost to follow-up with respect to baseline characteristics were also done using Fisher exact test or Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables, and using Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables.

Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) for repeated binary outcomes were used to assess stability of adherence for the whole group (population averaged model) over 48 weeks. GEEs were also used for both univariate and multiple logistic regression modeling of repeated measures to determine which factors were associated with adherence over time. The exchangeable correlation structure was used in all the models, as it exhibited good fit to the data. Univariate logistic regressions of repeated adherence measures on each of the demographic variables, youth, family, and extrafamilial factors, listed in Table III were performed. Interactions between time and each of the factors were also added in the GEE models and checked for significance. Time was considered either as continuous (in weeks) or categorical (week 24, week 48) variable in the GEE models that were computed. In the end, the continuous representation was used in the final analyses, as it exhibited better fit (smaller QICu) in the models where it was used. Representation of race as either black or other category was used in the final analyses after exploratory analysis showed no difference among the other groups with respect to nonadherence. Factors or variables with associated p < .25 in the univariate repeated measures models were considered as potential predictors in the multiple logistic regression repeated measures modeling of nonadherence. Forward selection with a 10% level of significance for including variables was used to determine the final models.

Table III.

Summary of Baseline Cognitive, Behavioral, and Psychosocial Assessments (N = 138)

| Characteristic | N | Mean (SD) | Median (minimum, maximum) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual child factors | |||

| Full-scale IQ | 124 | 84.7 (17.9) | 86 (42, 140) |

| BASC-PRS internalizing problems composite | 122 | 50.5 (11.1) | 49 (31, 83) |

| BASC-PRS externalizing problems composite | 122 | 50.4 (13.0) | 48.5 (30, 97) |

| BASC-SRP emotional symptoms index | 115 | 48.4 (8.3) | 46 (37, 72) |

| BASC-SRP school maladjustment composite | 116 | 50.7 (9.9) | 48 (33, 85) |

| Family factors | |||

| Caregiver well-being | 138 | 8.0 (1.6) | 8.2 (2.4, 10.0) |

| Caregiver belief about HIV | 134 | 2.1 (0.7) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.2) |

| BASC-SRP relation to parents | 116 | 48.3 (10.9) | 52 (10, 58) |

| Extrafamilial factors | |||

| Caregiver satisfaction with social support | 136 | 3.3 (0.8) | 4.0 (1.0, 4.0) |

| Youth satisfaction with social support | 125 | 3.6 (0.7) | 4.0 (1.0, 4.0) |

| Number of recent stressful life events | 114 | 1.1 (1.6) | 0 (0, 6) |

In an effort to alleviate potential bias that may occur under standard methods of analyses (e.g., by complete case analysis or imputing missing loss to follow-up data by the “last observation carried forward” method), we used multiple imputation with n = 3 imputations for each time point with missing adherence value. Markov Chain Monte Carlo method was used on relevant missing values to attain monotone missingness, and then linear regression was used to impute the remaining missing values. Imputed values were rounded to either 0 or 1, whichever is the closest. The statistical package SAS version 9.2 was used in all analyses.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Tables I and II show summaries of regimen characteristics, patient characteristics, and baseline predictors considered. Table III shows summaries for the baseline cognitive, behavioral, and psychosocial measures being studied. About half of the patients had full-scale IQ scores in either the impaired (<70) or at-risk (70–85) category. The mean and median BASC-SRP or BASC-PRS scores were about the same as the general population mean score of 50.

Table I.

Patient Regimen and Regimen Complexity at Baseline (N = 138)

| Characteristic | Overall n (%) |

|---|---|

| On protease inhibitor | |

| No | 31 (22%) |

| Yes | 107 (78%) |

| Maximum dose per day (for drug with highest number of doses/day) | |

| 1 | 7 (5%) |

| 2 | 125 (91%) |

| 3 | 3 (2%) |

| Missing | 3 (2%) |

| Total number of doses/day (whole regimen) | |

| 2 | 2 (1%) |

| 3 | 10 (7%) |

| 4 | 21 (15%) |

| 5 | 36 (26%) |

| 6 | 38 (28%) |

| 7 | 15 (11%) |

| 8 | 9 (7%) |

| 9 | 4 (3%) |

| Missing | 3 (2%) |

Table II.

Patient Demographic and Selected Baseline Characteristics (N = 138)

| Characteristic | Overall n (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |

| Female | 62 (45%) |

| Age | |

| 8 to <12 years | 57 (41%) |

| 12 to <19 years | 81 (59%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White/others | 21 (15%) |

| African American | 79 (57%) |

| Hispanic | 38 (28%) |

| Primary caregiver | |

| Biological parent/relative | 92 (67%) |

| Other adult/shelter/home | 46 (33%) |

| Education level of primary caregiver | |

| Grade 1-11/other/unknown | 49 (35%) |

| High school graduate | 89 (65%) |

| Individual child factors | |

| Youth knows HIV status | |

| No | 40 (29%) |

| Yes | 98 (71%) |

| Family factors | |

| Caregiver fully responsible for meds (caregiver-reported) | |

| No | 64 (47%) |

| Yes | 72 (53%) |

| Missing | 2 (–) |

| Extrafamilial factors | |

| Number of recent calls to clinic | |

| None | 89 (78%) |

| At least one | 25 (22%) |

| Missing | 24 (–) |

| HIV disease markers | |

| Detectable viral load (HIV-1 RNA > 400 cp/mL) | |

| No | 77 (62%) |

| Yes | 48 (38%) |

| Missing | 13 (–) |

| CD4 percent | |

| <15% | 10 (8%) |

| 15 to <25% | 31 (24%) |

| ≥25% | 86 (68%) |

| Missing | 11 (–) |

| CDC class C | |

| No | 90 (65%) |

| Yes | 48 (35%) |

Adherence data were available for 138 participants at baseline, 112 participants at week 24, and 103 participants at week 48. Of the 138 with baseline adherence data, 38 (25%) did not have adherence data either at week 48 or starting from week 24 and were thus considered lost to follow-up for this analysis. There were 11 participants who had no week 24 adherence data but had week 48 adherence data, and so were not considered lost to follow-up. None of the characteristics listed in Table I were significantly associated with loss to follow-up. Multiple imputation was performed (as described in the statistical section) to replace the missing data at each time point for each subject, and was included in the estimation of the GEE models with repeated measures. Rates of nonadherence were not significantly different across time points, with 36% (50/138), 39% (44/112), and 29% (30/103) at baseline, week 24, and week 48, respectively (GEE model with repeated measures and no other predictors had p = .13).

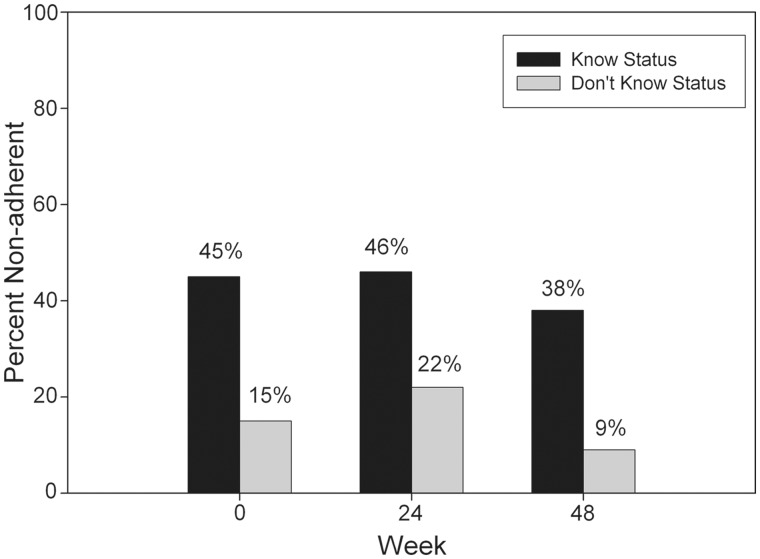

Univariate Associations With Longitudinal Nonadherence

Unadjusted (for other predictors) odds ratios (ORs) of nonadherence for regimen, demographics, individual child, family, and extrafamilial factors, using a GEE model for repeated measures based on adherence data at baseline, week 24, and week 48, are shown in Table IV. Among measures of individual child factors, only Child Knowledge of HIV Status was found to be significantly related to nonadherence (OR = 3.27, p < .001). Among measures of family factors, low Caregiver Well-being (OR = 0.75, p = .007) was significantly related to nonadherence. None of the proposed extrafamilial system factors were significant in univariate analysis. None of the factors had a significant interaction with time. Figure 1 shows observed trends for a baseline factor that significantly predicts longitudinal nonadherence. In this case, the main effect of the baseline predictor (Child Knowledge of HIV Status) was significant, but it had no significant interaction with time. Thus, nonadherence rates appear stable over time for both groups, but the proportion of nonadherents among children who were aware of their HIV status was consistently higher compared with those who did not know their status, by an amount that was about the same over time.

Table IV.

Odds of Caregiver-Reported Nonadherence on Social Ecological Predictors (Based on GEE Model With Repeated Measures Unadjusted for Other Predictors)

| Predictors | Odds ratio | 95% LCI | 95% UCI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regimen and regimen complexity at baseline | ||||

| On PI | 0.91 | 0.44 | 1.88 | .802 |

| Maximum daily dose (of drug with largest dose) | 0.51 | 0.16 | 1.68 | .273 |

| Total number of doses per day (whole regimen) | 0.87 | 0.70 | 1.07 | .195 |

| Individual child factors | ||||

| Youth knows HIV status | 3.27 | 1.70 | 6.28 | <.001 |

| Full-scale IQ | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 | .806 |

| BASC-PRS internalizing problems | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.03 | .979 |

| BASC-PRS externalizing problems | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.04 | .262 |

| BASC-SRP emotional symptoms | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.05 | .494 |

| BASC-SRP school maladjustment | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.03 | .802 |

| Family factors | ||||

| Caregiver well-being | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.92 | .007 |

| Caregiver belief about HIV | 0.92 | 0.60 | 1.40 | .683 |

| Degree of caregiver responsibility | ||||

| Caregiver fully responsible for medication | 0.62 | 0.36 | 1.07 | .089 |

| BASC-SRP relation to parents | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.00 | .054 |

| Caregiver: biological parent/relative | 0.88 | 0.49 | 1.59 | .684 |

| Extrafamilial factors | ||||

| Caregiver satisfaction w/social support | 1.06 | 0.75 | 1.49 | .756 |

| Youth satisfaction w/social support | 1.25 | 0.84 | 1.86 | .267 |

| At least one call to clinic | 1.13 | 0.47 | 2.71 | .790 |

| Number of recent stressful life events | 1.11 | 0.92 | 1.35 | .270 |

Figure 1.

Percentage of nonadherent subject by youth knowledge of HIV status.

Multivariate Repeated Measures Model Predicting Nonadherence

Potential predictors with a p < .25 in the univariate GEE models with repeated measures were entered in the forward model selection process. These were: Child Knowledge of HIV Status, Caregiver Well-being score, Caregiver Fully Responsible for Medication (yes or no), BASC Relation to Parents T-score, and Black Race (yes or no). At each stage of model selection, the variable with smallest p < .10 was entered. All variables with p < .05 were kept in the final model (Table V). The final GEE model with repeated measures contained the following variables: Child Knowledge of HIV (adjusted OR = 3.80, p < .001), low Caregiver Well-being (adjusted OR = 0.76, p = .016), poor BASC Relation to Parents (adjusted OR = 0.97, p = .033), and Black Race (adjusted OR = 2.29, p = .009). The time variable (weeks) was not significant, confirming that the rate of nonadherence in this group was stable over time.

Table V.

Final GEE Model With Repeated Measures: Odds of Caregiver-Reported Nonadherence on Significant Predictors (Forward Selection Method)

| Predictors | Adjusted odds ratioa | 95% LCI | 95% UCI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekb | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | .183 |

| Youth knows HIV status | 3.80 | 1.81 | 7.98 | <.001 |

| Caregiver well-being | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.95 | .016 |

| BASC-SRP relation to parents | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1.00 | .033 |

| Ethnicity: black | 2.29 | 1.24 | 4.26 | .009 |

aAdjusted for other predictors in the model.

bRepresented as continuous variable.

To further understand why some factors were not selected in the final model owing to shared variance and the possibility of indirect effects, relationships between factors significant in the longitudinal model and other system factors were analyzed. Youth Knows HIV Status was significantly associated with Caregiver Fully Responsible, with 71% of children who do not know their status having caregivers fully responsible for medication compared with 46% of those who know their status (Fisher exact test p = .012). Moreover, Youth Knows HIV Status was significantly associated with age at study entry (Kruskal–Wallis p < .001), with youth who knew their HIV status being generally older than children who did not know their status. Caregivers who had higher well-being were more likely to be fully responsible for medication (Kruskal–Wallis test p = .027). Caregiver well-being was negatively correlated with child externalizing behavior (Spearman correlation coefficient = −.23, p = .011) and child internalizing behavior (Spearman correlation coefficient = −.21, p = .020). Caregiver well-being was positively correlated with his/her satisfaction with social support (Spearman correlation coefficient = .27, p = .001). The BASC-SRP Relation to Parents score was positively correlated with the BASC-SRP Emotional Symptoms Index score (Spearman correlation coefficient = .41, p < .001) and negatively associated with the BASC-SRP School Maladjustment Composite score (Spearman correlation coefficient = −.31, p < .001). Finally, black children were found to be significantly older than nonblack children in this cohort (Kruskal–Wallis p = .042).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study of adherence to treatment in perinatally infected youth. More than one-third of the youths’ caregivers reported nonadherence across the 48 weeks, and nonadherence was consistent across this period. Although recent advances in the effectiveness of ART suggest that less-than-perfect adherence may be acceptable for achieving viral suppression (e.g., Müller, Myer, & Jaspan, 2009), this was likely not the case with the regimens available during the study period (2004–2006). Furthermore, because self-report measures tend to overestimate adherence, researchers have considered any reported deviation from 100% adherence as indicative of an adherence concern (Marhefka, Tepper, Brown, & Farley, 2006; Steele & Grauer, 2003).

When simultaneously considering multiple system factors predicting longitudinal adherence, family factors were most pronounced. Few individual child factors independently predicted adherence. Cognitive functioning was unrelated, similar to findings from Malee et al. (2009), although both studies used relatively global measures of cognition and not neuropsychological assessment of more specific cognitive functions. Internalizing and externalizing behaviors also were unrelated to adherence longitudinally. Although Malee et al. (2011) found that conduct problems were associated with nonadherence, that study used a measure of ADHD symptoms versus the broader range of externalizing symptoms, included much younger children, and was cross-sectional.

Within the individual child, only knowledge of HIV status prospectively and independently predicted nonadherence. Simoni and colleagues' (2007) review concluded that studies have shown inconsistent support for this relationship. In this study, knowledge of HIV status was associated with older age, and multiple studies have documented that adherence deteriorates in adolescents (Drotar & Levers, 1994; McQuaid et al., 2003; Mellins et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2006). It is also possible that youth who do not know their status have caregivers who are more involved in illness management, a factor also associated with improved adherence (Ellis, Podolski et al., 2007). Further research is necessary to elucidate these relationships, and these findings do not suggest that adolescents with HIV should not know their diagnosis. Disclosure is ethically mandatory as adolescents become sexually active. However, interventions could focus on maintaining a high degree of caregiver involvement in ART administration during and after the disclosure process.

In fact, children whose caregivers assumed full responsibility were more likely to maintain adherence. Although it is certainly developmentally appropriate for adolescents to engage in self-care, adherence may be best maintained when caregivers believe that they are ultimately responsible (i.e., “the buck stops here”). Of note, caregiver responsibility should occur in the context of youth perceptions of good caregiver–child relationships, as this variable was also independently predictive of nonadherence.

Caregiver well-being also was related to adherence independent of other factors, and appears to be more important to adherence than stressful life events or relationship to child (biological/relative). Whereas others have theorized that children cared for by biological caregivers are more likely to have adherence difficulties owing to poorer caregiver well-being (Simoni et al., 2007), our finding provides evidence to support this assumption. Furthermore, it may not be the direct effect of caregiver stress that affects adherence but the secondary impact of stress on caregivers’ physical and emotional functioning. In fact, caregiver well-being was related to social support, which may buffer against stressful life events.

Surprisingly, extrafamilial factors were not directly predictive of longitudinal nonadherence. However, the study did not include a formal measure of engagement or satisfaction with care, and the proxy variable (number of calls to clinic) may not reflect true engagement. Also, youth of African American descent had significantly higher odds of nonadherence over time. It is possible that ethnicity is a proxy for other extrafamilial factors, as medication adherence is particularly complicated by the disparities in access to health care and other health support services and increased family stress associated with low-income minority status (Marhefka et al., 2006). African American families may be more likely to have lower income and be single-parent families (Page & Stevens, 2005), characteristics that have been associated with nonadherence (Ellis, Yopp et al., 2007; Marhefka et al., 2006), but owing to limitations were not measured in this study.

There are additional limitations. The study was designed as a preliminary study to guide development of intervention trials, and therefore, many variables were considered and multiple statistical tests used. Owing to interest in examining the pattern of results, a significance level of p < .05 for each test was maintained rather than correcting for multiple comparisons. The youth and caregivers who participated in P1042s were randomly selected from P219C, and there were less-than-ideal recruitment and retention rates (approximately 75%). The families willing to participate in P219C, and to devote further time to P1042s, may not be representative of families typically seen in pediatric HIV clinics. Improved measurement of specific aspects of neuropsychological function, social support, and engagement with the medical team, as well as the inclusion of youth report of depression (not directly measured in BASC Emotional Symptoms Index), would further elucidate the role of these factors in predicting adherence.

In summary, this is the first multisite study to simultaneously evaluate factors across multiple systems associated with ART adherence, and it is the first to use longitudinal data to strengthen conclusions about causality. Although measurement limitations require further research to confirm these findings, particularly related to the impact of extrafamilial factors, these data suggest that more family factors are associated with adherence than individual child factors even in a predominantly adolescent sample. Caregiver variables were so prominently predictive of adherence over time that caregiver interventions may be the first line for the prevention or treatment of nonadherence. Indeed, in other areas of pediatric health such as obesity, a caregiver-only intervention was more effective than an intervention that included both parents and their school-aged children (Golan & Crow, 2004; Golan, Weizman, Apter, & Fainaru, 1998). Multisystemic therapy, a home-based family treatment, has been shown to improve ART adherence in a primarily perinatally infected sample of adolescents compared with an individual motivational intervention in a recent pilot clinical trial (Letourneau et al., 2013). Interventions focusing on parental monitoring, such as those in the adolescent risk behavior literature (e.g., Stanton et al., 2004), may also be promising. However, the focus on caregiver must not be at the expense of the youth’s perception of high-quality family relationships and the need to eventually transition responsibility from the caregiver to the emerging adult living with HIV.

Funding

Overall support for the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Group (IMPAACT) was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (U01 AI068632), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (AI068632). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center at Harvard School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement #5 U01 AI41110 with the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) and #1 U01 AI068616 with the IMPAACT Group. Support of the sites was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the NICHD International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Clinical Trials Network funded by NICHD (contract number N01-DK-9-001/HHSN267200800001C). The study was funded by the United States National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. These institutions were involved in the design, data collection, and conduct of protocol P1042S, but were not involved in the present analysis, the interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit for publication. Additional funding was provided by the William T. Grant Foundation. This work was supported by the Statistical and Data Analysis Center (SDAC) of the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group at Harvard School of Public Health, under the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases cooperative agreement No. 5 01 AI41110.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the children and families for their participation in PACTG 1042S, and the individuals and institutions involved in the conduct of P1042S. The following institutions and individuals participated in PACTG Protocol 1042S, by order of enrollment: Children’s Hospital Boston: K. McIntosh, B. Kammerer, S. Burchett; University of Maryland School of Medicine: S. Allison, V. Tepper, C. Hilyard; State University of New York at Stony Brook School of Medicine: S. Nachman, J. Perillo, M. Kelly, D. Ferraro; St. Christopher's Hospital for Children: J. Foster, J. Chen, D. Conway, R. Laguerre; Children’s Memorial Hospital: R. Yogev, E. Chadwick, K. Malee; Jacobi Medical Center: A. Wiznia, Y. Iacovella, M. Burey, R. Auguste; University of California San Francisco School of Medicine: D. Wara, M. Muskat, N. Tilton; St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital: P. Garvie, D. Hopper, M. Donohoe, S. Carr; Tulane Medical School - Charity Hospital Medical Center of Louisiana at New Orleans: R. Van Dyke, P. Sirois, C. Borne, S. Bradford, K. Jacobs, A. Ranftle; Children’s Hospital, University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center: R. McEvoy, S. Paul, E. Barr, M. Abzug; University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, New Jersey Medical School: J. Oleske, L. Bettica, L. Monti, J. Johnson; Texas Children’s Hospital: M. Paul, C. Jackson, L. Noroski, T. Aldape; Baystate Medical Center: B. Stechenberg, D. Fisher, S. McQuiston, M. Toye; University of Miami Miller School of Medicine: G. Scott, C. Mitchell, E. Willen, L. Taybo; University of California San Diego: S. Spector, S. Nichols; State University of New York Downstate Medical Center: H. Moallem, S. Bewley, L. Gogate; San Juan City Hospital: E. Jimenez, J. Gandia, D. Miranda; Duke University School of Medicine: O. Johnson, J. Simonetti, K. Whitfield, F. Wiley; Harlem Hospital Center: E. Abrams, M. Frere, D. Calo, S. Champion; University of Puerto Rico: I. Febo, R. Santos, N. Scalley, L. Lugo; Children’s National Medical Center: D. Dobbins, M. Lyon, V. Amos, H. Spiegel; Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center: E. Stuard, A. Cintron; Johns Hopkins University: N. Hutton, B. Griffith; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine: T. Belhorn, J. McKeeman; New York University School of Medicine: W. Borkowsky, S. Deygoo, E. Frank, S. Akleh; Yale University School of Medicine: W. Andiman, M. Westerveld; State University of New York Upstate Medical University: R. Silverman, J. Schueler-Finlayson; Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center: A. Stek, A. Kovacs; University of Alabama at Birmingham: R. Pass, J. Ackerson, H. Charlton, M. Crain; Medical College of Georgia School of Medicine: C. Mani; North Broward Hospital District, Children’s Diagnostic & Treatment Center: A. Puga, J. Blood, A. Inman; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: S. Douglas, R. Rutstein, C. Vincent, G. Koutsoubis; Long Beach Memorial Medical Center: A. Deveikis, R. Seay, S. Marks; J. Batra; Howard University Hospital: S. Rana, O. Adeyiga, R. Rigor-Mator, S. Wilson; Children’s Hospital and Research Center Oakland: A. Petru T. Courville; Phoenix Children’s Hospital: J. Piatt, M. Lavoie.

References

- Anderson B J, Auslander W F, Jung K C, Miller J P, Santiago J V. Assessing family sharing of diabetes responsibilities. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1990;15:477–492. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach M C, Keruly J, Moore R D. Is the quality of the patient provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by design and nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Drotar D, Levers C. Age differences in parent and child responsibilities for management of cystic fibrosis and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Journal of Development and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1994;15:265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis D A, Podolski C L, Frey M, Naar-King S, Wang B, Moltz K. The role of parental monitoring in adolescent health outcomes: Impact on regimen adherence in youth with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:907–917. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis D A, Yopp J, Templin T, Naar-King S, Frey M A, Cunningham P B, Idalski A, Niec L. Family mediators and moderators of treatment outcomes among youths with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:194–205. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley J J, Montepiedra G, Storm D, Sirois P A, Malee K, Garvie P, Kammerer B, Naar-King S, Nichols S. Assessment of Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in perinatally HIV- infected children and youth using self-report measures and pill counting. Journal of Development and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2008;29:377–384. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181856d22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuemmeler B F. Bridging disciplines: An introduction to the special issue on public health and pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2004;29:405–414. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan M, Crow S. Targeting parents exclusively in the treatment of childhood obesity: Long-term results. Obesity. 2004;12:357–361. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan M, Weizman A, Apter A, Fainaru M. Parents as the exclusive agents of change in the treatment of childhood obesity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1998;67:1130–1135. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazra R, Siberry G K, Mofenson L M. Growing up with HIV: Children, adolescents, and young adults with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Annual Review of Medicine. 2010;61:169–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.050108.151127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A E. Families of chronically ill children: A systems and social-ecological model of adaptation and challenge. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:25–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G M, Gortmaker S L, McIntosh K, Hughes M D, Oleske J M. Quality of life for children and adolescents: Impact of HIV infection and antiretroviral treatment. Pediatrics. 2006;117:273. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau E J, Ellis D A, Naar-King S, Chapman J E, Cunningham P B, Fowler S. Multisystemic therapy for poorly adherent youth with HIV: Results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. AIDS Care. 2013;25:507–514. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.715134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malee K, Williams P, Montepiedra G, McCabe M, Nichols S, Sirois P, Storm D, Farley J, Kammerer B. Medication adherence in children and adolescents with HIV infection: Associations with behavioral impairment. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25:191–200. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0181. doi:10.1089/apc.2010.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malee K, Williams P L, Montepiedra G, Nichols S, Sirois P A, Storm D, Farley J, Kammerer B. The role of cognitive functioning in medication adherence of children and adolescents with HIV infection. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009; 34:164. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhefka S L, Tepper V J, Brown J L, Farley J J. Caregiver psychosocial characterisitics and children's adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care & STDS. 2006;20:429–437. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid E L, Kopel S J, Klein R B, Fritz G K. Medication adherence in pediatric asthma: Reasoning, responsibility, and behavior. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;28:323–333. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins C A, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Abrams E J. The role of psychosocial and family factors in adherence to antiretroviral treatment in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2004;23:1035–1041. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000143646.15240.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A D, Myer L, Jaspan H. Virological suppression achieved with suboptimal adherence levels among South African children receiving boosted protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48:e3–e5. doi: 10.1086/595553. doi:10.1086/595553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Arfken C, Frey M, Harris M, Secord E, Ellis D. Psychosocial factors and treatment adherence in pediatric HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18:621–628. doi: 10.1080/09540120500471895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Montepiedra G, Nichols S, Farley J, Garvie P A, Kammerer B, Malee K, Sirois P A, Storm D. Allocation of family responsibility for illness management in pediatric HIV. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:187–194. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols S L, Montepiedra G, Farley J J, Sirois P A, Malee K, Kammerer B, Garvie P A, Naar-King S. Cognitive, academic, and behavioral correlates of medication adherence in children and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Peditrics. 2012;33:289–308. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31824bef47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M E, Stevens A H. Understanding racial differences in the economic costs of growing up in a single-parent family. Demography. 2005;42:75–90. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontali E. Facilitating adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in children with HIV infection: What are the issues and what can be done? Pediatric Drugs. 2005;7:137–149. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200507030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C R, Kamphaus R W. Manual for the behavior assessment system for children. 2nd ed. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Riekert K A, Drotar D. The beliefs about medication scale: Development, reliability, and validity. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2002;9:177–184. doi:10.1023/a:1014900328444. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni J M, Montgomery A, Martin E, New M, Demas P A, Rana S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIV infection: A qualitative systematic review with recommendations for research and clinical management. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1371–e1383. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B, Cole M, Galbraith J, Li X, Pendelton S, Cottrel L, Marshall S, Wu Y, Kaljee L. Randomized trial of a parent intervention: Parents can make a difference in long-term adolescent risk beahviors, perceptions and knowledge. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:947–955. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.10.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele R G, Grauer D. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIV infection: Review of the literature and recommendations for research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:17–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1022261905640. doi:10.1023/a:1022261905640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Williams P L, Storm D, Montepiedra G, Nichols S, Kammerer B, Sirois P A, Farley J, Malee K PACTG 219C Team. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1745–e1757. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]