Abstract

Development of chemically stable proton conductors for solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) will solve several issues, including cost associated with expensive inter-connectors, and long-term durability. Best known Y-doped BaCeO3 (YBC) proton conductors-based SOFCs suffer from chemical stability under SOFC by-products including CO2 and H2O. Here, for the first time, we report novel perovskite-type Ba0.5Sr0.5Ce0.6Zr0.2Gd0.1Y0.1O3−δ by substituting Sr for Ba and co-substituting Gd + Zr for Ce in YBC that showed excellent chemical stability under SOFC by-products (e.g., CO2 and H2O) and retained a high proton conductivity, key properties which were lacking since the discovery of YBCs. In situ and ex- situ powder X-ray diffraction and thermo-gravimetric analysis demonstrate superior structural stability of investigated perovskite under SOFC by-products. The electrical measurements reveal pure proton conductivity, as confirmed by an open circuit potential of 1.15 V for H2-air cell at 700°C, and merits as electrolyte for H-SOFCs.

The finite nature of oil resources and the ever-growing energy demand necessitate the finding of an alternative energy conversion technology that is highly efficient and free of greenhouse gas emissions1,2. Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) utilizing oxide-ion conductors (e.g., Y-doped ZrO2 (YSZ)) due to higher efficiency (up to ~80%), fuel flexibility, and combined heat power generation are being considered as alternative over conventional greenhouse gas emission system for stationary and mobile applications3,4. However, high operating temperatures, typically between 800–1000°C, results in material degradation, coking in case of direct hydrocarbon fuels and sulfur poisoning in Ni-based cermet electrodes. The operating temperature of SOFCs is commonly dictated by the choice of electrolytes; hence, efforts have been focused on intermediate temperature (IT) (400–700°C) ceramic proton conductors to reap many benefits especially with economic metal interconnects5,6,7,8. Among the known electrolytes, aliovalent-doped BaCeO3 (BCs) have demonstrated high proton conductivity (~10−2 Scm−1 at 700°C), but, their poor chemical stability to SOFC by-products such as H2O and CO2 restricted them from being considered for proton conducting SOFCs9,10.

Persistent efforts to improve the key features of BCs have shown that dopant with higher ionic size compared to Ce increases their proton conductivity, while higher electronegative dopants increase their chemical stability. Yttrium remains as one of the best candidates for doping Ce in BCs, whereas Yb and Pr co-doping exhibited mixed ionic and electronic conduction11,12. A comparison of the ionic radii and electronegativity (see supplementary Table S1 online) suggests that both Y and Gd seem to be ideal for Ce site doping in BCs, which is further supported by computational studies using a ‘mean field approach' where Gd3+ and Y3+ have showed the lowest solution energy for doping in Ce site13. On the other hand, Sr-doping for Ba is proven to increase the phase stability under water vapor14. In contrast to BCs, BaZrO3–based proton conductors show appreciable chemical stability, but have poor sinter-ability and normally needs very high temperature sintering (>1700°C) that makes them unsuitable for electrode supported SOFCs15,16,17. Here, we demonstrate a novel perovskite-type Ba0.5Sr0.5Ce0.6Zr0.2Gd0.1Y0.1O3−δ (here after called as perovskite I”) with excellent chemical stability under CO2 and water vapor at the desired IT-SOFC operating condition along with high proton conductivity that can be used in practical proton conducting SOFCs.

Results

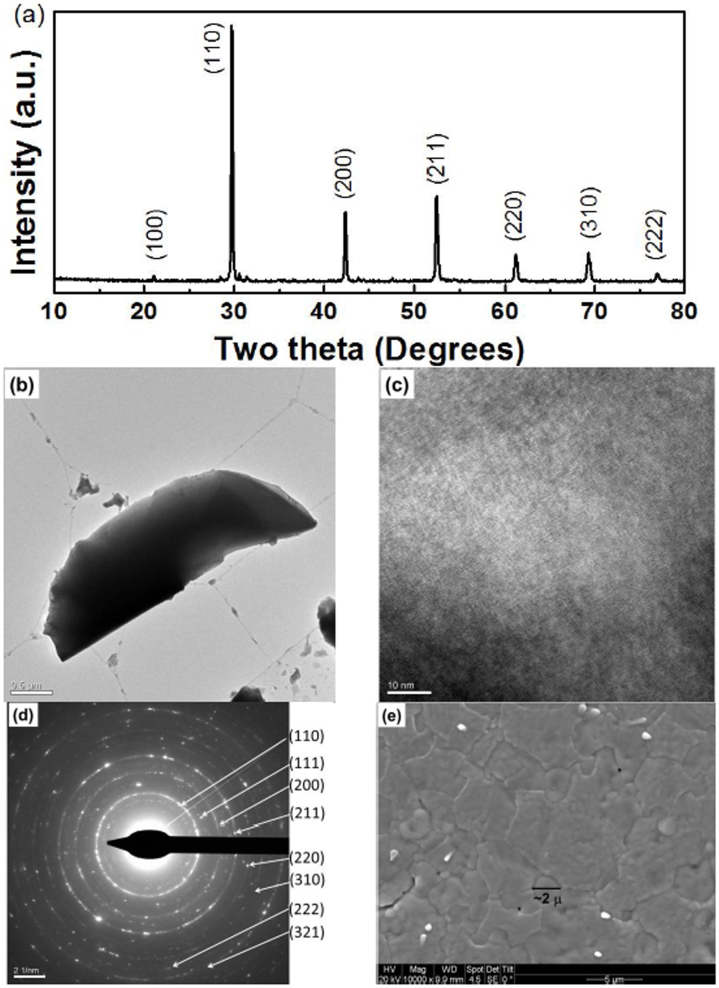

Perovskite I of the nominal formula Ba0.5Sr0.5Ce0.6Zr0.2Gd0.1Y0.1O3−δ was prepared by solid-state (ceramic) method at 1450°C for 24 h. Figure 1a shows the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern of as-prepared sample. Figures 1b–1d show the TEM, HR-TEM and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of the perovskite I, respectively. The crystallite size obtained from TEM image was found to be in the range of 200 nm. Further, crystallite sizes are narrowly distributed and are highly crystalline as seen from the ring intensities in SAED18. SEM image obtained on the polished pellet reveals the highly dense nature of perovskite I pellet and grains in 2–5 microns range as shown in Figure 1e.

Figure 1. Phase characterization and morphological studies.

(a) PXRD pattern obtained for the as-prepared, Ba0.5Sr0.5Ce0.6Zr0.2Gd0.1Y0.1O3−δ (perovskite I) revealing the formation of cubic perovskite structure with a very small impurity peak near 2θ values of 30°, (b) TEM image of perovskite I (c) HR-TEM (d) SAED pattern of perovskite I with their corresponding crystal planes indexed again suggesting the formation of single phase and (e) SEM image of perovskite I showing grains in the range of 2–3 μ and revealing the dense nature of the pellet.

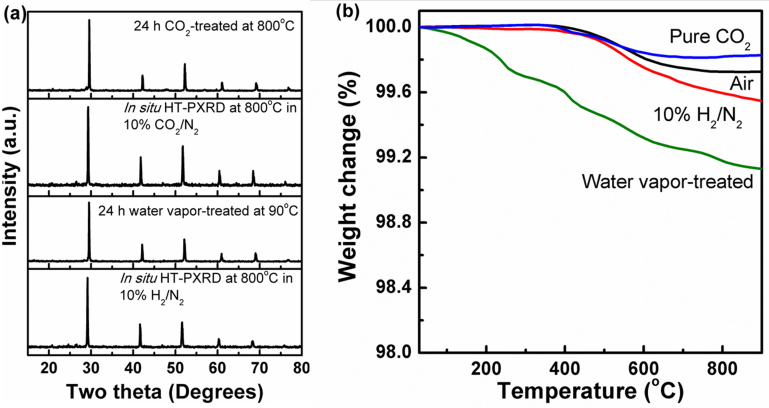

Figures 2a and 2b show the results of PXRD and TGA measurements in various stability studies, respectively. FT-IR measurements on the perovskite I before and after CO2 treatment at 800°C are shown in supplementary Fig. S1. PXRD pattern in Figure 2a after 24 h water vapor treatment of perovskite I do not show any additional peaks corresponding to the formation of Ba(OH)2. We extended the treatment time to 48 and 168 h, but no major change was observed in their PXRD pattern, suggesting significant chemical stability under water vapor (see supplementary Fig. S2 online). TGA curves obtained on these samples suggest a maximum weight loss of <1% up to 900°C after 24 h. However, exposure to water vapor for extended periods (for 48 and 168 h) show a steady increase in weight loss with exposure time (see supplementary Fig. S3 online). Despite the increased water uptake, PXRD do not reveal any additional peaks other than the perovskite-phase lines. FT-IR study on perovskite I before and after water vapor treatment studies show only a minor peak at 855 cm−1 which could be due to Ba-O bond vibrational modes (see supplementary Fig. S4 online)19.

Figure 2. Comparison of chemical stability of Ba0.5Sr0.5Ce0.6Zr0.2Gd0.1Y0.1O3−δ (perovskite I) under various environments.

(a) PXRD pattern of perovskite I after exposure to CO2 at 800°C and H2O vapor at 90°C along with in situ high temperature PXRD patterns obtained under 10% CO2/N2 and 10% H2/N2 at 800°C reveal its chemical stability and (b) TGA curve obtained for perovskite I under air, CO2 and dry H2 all resemble each other closely suggesting no significant change in the chemical composition. TGA of H2O vapor treated sample shows drop in weight from temperatures as low as 100°C suggesting the incorporation of H2O in the crystal lattice.

The ratio between the PXRD diffraction intensities of (I110/I200), (I110/I211) and (I211/I200) remains constant after various stability measurements, further confirming the structural integrity of the perovskite I (see supplementary Table S2 online). An additional indication of perovskite I chemical stability is its appearance before and after exposure to CO2 and H2O vapor as it retains its green color despite the harsh chemical stability tests (see supplementary Fig. S5 online). To understand the role of CO2 partial pressure on chemical stability, we passed a mixture of 1:1 volume mixture of CO2 and N2 with 30% humidification for 140 h at 600°C. The resulting perovskite I's PXRD pattern does not reveal any additional diffraction peaks corresponding to BaCO3 or Ba(OH)2 formation (see supplementary Fig. S6 online).

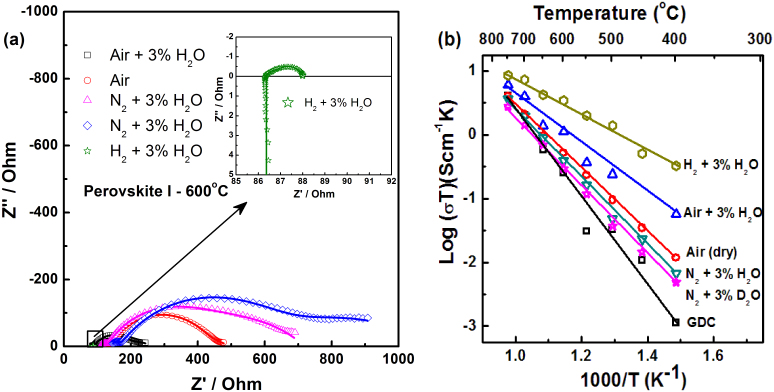

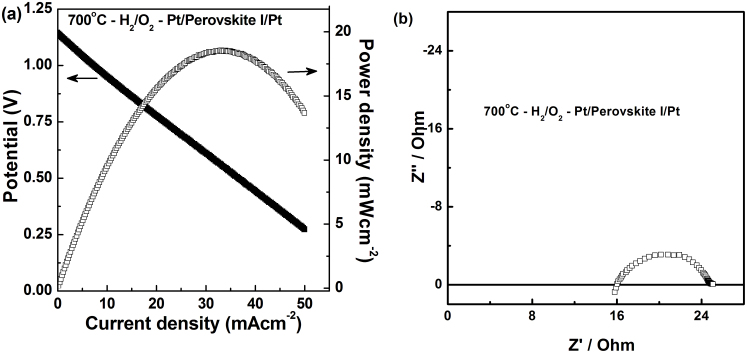

AC impedance plots obtained for the perovskite I under different environments at 600°C are given in Figure 3a, along with the fitting results. Equivalent circuits used for fitting is given in supplementary Fig. S7 and verification of the fitting results were done by Kramers and Kronig (KK) analysis (see supplementary Fig. S8 online)20,21. Further, the calculated capacitance values from equivalent series fitting showed the presence of grain-boundary and bulk contributions at low temperatures, while at higher temperatures the grain-boundary effects disappear as observed from the removal of semi-circle corresponding to capacitance 10−8 F (see supplementary Table S3 online). Arrhenius plots for perovskite I and Gd-doped CeO2 (GDC) (one of the commercial IT-SOFC electrolytes) are shown in Figure 3b. The activation energy obtained under wet hydrogen atmosphere for perovskite I is 55 kJmol−1 significantly lower than the 94 kJmol−1 obtained under air, confirming its proton conducting nature under wet hydrogen. Fuel cell polarization (hydrogen–air cell) plots obtained with the perovskite I as an electrolyte and Pt electrodes by passing humidified hydrogen and air are given in Figure 4a. The open circuit potential (OCP) observed at 700°C was found to be 1.15 V which is close to Nernst potential for water formation.

Figure 3. Conductivity measurement of Ba0.5Sr0.5Ce0.6Zr0.2Gd0.1Y0.1O3−δ (perovskite I).

(a) Nyquist plot obtained for perovskite I under different environments revealing the increase in resistance in the order of H2 + 3% H2O < air + 3% H2O < air < N2 + 3% H2O < N2 + 3% D2O at 600°C. The lines passing through the data points are fitting results. (b) Arrhenius plot of perovskite I in various environments along with that of GDC measured in air revealing increased conductivity for perovskite I against GDC. Activation energy of 55 kJmol−1 is observed under H2 + 3% H2O environments.

Figure 4. Polarization studies on Ba0.5Sr0.5Ce0.6Zr0.2Gd0.1Y0.1O3−δ (Perovskite I).

Fuel cell polarization plot obtained using Pt paste as the cathode and anode and Perovskite I as electrolyte under humidified H2 and dry O2 as the fuel and oxidant at 700°C and (b) Impedance Nyquist plot obtained for this cell under above mentioned conditions in the frequency range of 1 MHz to 0.1 Hz. The high resistance observed in the Nyquist plot is due to thicker electrolyte (~3 mm).

Discussion

PXRD study (Figure 1a) suggests the formation of a single-phase perovskite-type structure in space group Pm3m (no.: 221) with a lattice constant (a) of 4.282(3) Å. The FFT analysis of the HR-TEM image further specifies the formation of cubic crystal lattice (See supplementary Fig. S9 online). This significantly lower lattice constant in comparison with other rare earths and Zr co-doped BCs could be attributed to the incorporation of smaller Sr (118 pm) for Ba (135 pm). For example, Gd, Pr, Sm and Zr-codoped BCs showed lattice constants in the range of 4.387–4.330 Å22,23. The d-spacing obtained from the PXRD measurements are matching well with that of values obtained from SAED pattern (Figure 1d)18. The density of the pellets was found to be about 95% as measured by Archimedes method. In comparison, Y–doped BaZr0.85Y0.15O3−δ prepared by solid state method was reported to have a density in the range of 75–80% and hot pressing was required to obtain densities >95%9,24 which make BZY unsuitable for scalable SOFCs25.

Ex-situ PXRD pattern (Figure 2) obtained after exposure to pure CO2 at 800°C for 24 h reveals that the perovskite I retain the original perovskite-type structure with no additional peaks. Similarly, high temperature in-situ PXRD pattern obtained under 10% CO2/N2 doesn't show any second phase, confirming that the perovskite I remains robust against chemical reaction to CO2. TGA curve obtained under pure CO2 resembles that of the TGA curve obtained in air, further supporting in-situ and ex-situ PXRD studies that CO2 do not react with perovskite I in the whole temperature range despite favorable thermodynamic conditions. However, FT-IR measurements showed a very minor peak due to carbonate. Free energy of BaCO3 formation as a function of CO2 for BaCe1−xZrxO3 suggest about 70 mol% of Zr doping is needed to eliminate the carbonate formation at 800°C5. Hence, it is fair to assume that doping of comparatively higher electronegative elements in both A and B sites of BCs have increased their resistance toward the acidic CO2 and reduced the kinetics of BaCO3 formation significantly. While proton conducting SOFCs may operate normally on external reformed hydrogen that produces lower CO2 partial pressures, we carried out these stability measurements under extreme conditions to prove the superior stability of the perovskite I (Figure 2). Similar studies on YBCs reported to form carbonates at 500°C under CO2 exposure as low as 2%26. It is important to mention that the flow rate of gases and the final sintering temperature of the investigated perovskite seem to be crucial for the observed chemical stability under CO2.

The Gibbs free energy for the reaction between BCs and H2O vapor reaches the value of zero at 403°C and accordingly aliovalent doped BCs are reported to be stable at elevated temperatures (>500°C) under water vapour, while stability at low temperatures remained un-achievable27,28. Our recent work on Sm and Gd + Pr co-doped with Zr in BCs could not achieve chemical stability under water vapor at 90°C even after 30% Zr-substitution for Ce22,23. But in the case of perovskite I, we could achieve water vapor stability even at low temperature of 90°C for extended duration (Figures 2a and b, see supplementary Figs. S2 and S3 online). For 168 h water vapor exposed perovskite I sample, the TGA showed increase in weight loss when compared to 24 h and 48 h water vapor exposed samples (see supplementary Fig. S3 online).

Acceptor-doping in BCs can generate oxide ion vacancy according to the substitution mechanism:

|

where every 1 mole of M3+ doping creates 0.5 mole of oxygen vacancies. On complete filling of these vacancies by H2O, TGA will result in a weight loss of ~0.6%. However, 168 h exposure to H2O vapor at 90°C has resulted in weight loss of 3.5% which suggests excess water may be adsorbed at surfaces or possibly at the grain-boundaries. SEM images of powdered samples after 168 h exposure are shown in Fig. S10 (see supporting information online). A similar study on BaCe0.84Zr0.01Sm0.15O3−δ resulted in a weight loss of >8% and in FT-IR, formation of peaks corresponding to Ba(OH)2 in 24 h (see supplementary Fig. S11 online)22. Sm–doped BCs prepared in our group showed complete decomposition of the powders into amorphous materials in PXRD22. Thus, the increased water uptake upon extended exposure must be due to incorporation of water molecules in the vacancies and adsorption rather than formation of Ba(OH)2 as also confirmed by PXRD measurements. The diffusivity of water in doped perovskites is reported to be slow at low temperature, which could be the reason for the slight increase in weight due to water uptake for 168 h compared to 24 h and 48 h (see supplementary Fig. S3 online)29,30.

Chemical stability under H2 at elevated temperature is another significant factor as Ce based electrolyte materials tend to react under this highly reducing condition and result in lower cell potentials. HT-PXRD under 10% H2/N2 further proves perovskite I's possible utility as electrolyte as original perovskite structure is retained at 800°C. Similarly, TGA curves under pure H2 do not reveal significant weight loss and further proves the structural stability of the perovskite I under reducing conditions. Nevertheless, 0.13% weight loss in excess is observed for TGA in H2 in comparison to that obtained in air at 800°C which would correspond to ~4.5% conversion of Ce4+ to Ce3+. However, at the operating temperature of proton conducting SOFCs typically at 600°C, this conversion will be less than 2%. (see supplementary information for the calculation). Thus, based on the above results, we could conclude that perovskite I is considered to be highly stable under SOFC operating conditions, which is critical for its successful operation.

Perovskite 1 shows the highest conductivity under H2 + 3% H2O (Figs. 3a and 3b), while lowest under N2 + 3% D2O among investigated environments. In air, the conductivity is significantly higher under wet air than dry air suggesting proton conduction under wet conditions. Proton conductivity in doped BCs arises from the filling up of hydroxyl ions in the oxide vacancies (VO):

At low temperatures, the conductivity is dominated by proton transport due to higher H2O uptake. However, as indicated by TGA curves at high temperatures the protons leave the lattice thereby reducing the concentration of hydroxyl protons and contribution from oxide ion increases. Comparison of perovskite I's conductivity against that of oxide ion conducting Gd-doped CeO2 (GDC) made from commercial powders (GDC 10 TC – Fuel Cell Materials) show two orders of magnitude increased conductivity at low temperatures. Nevertheless, GDC is reported to show higher conductivity value in the literature11. A maximum ionic conductivity of 0.4 × 10−2 Scm−1 is observed at 600°C for perovskite I, where the in-house prepared GDC showed a conductivity of 0.3 × 10−3 Scm−1 under similar experimental condition. BaZr0.8Y0.2O3−δ showed a conductivity of 7.9 × 10−3 Scm−1 at this temperature after hot pressing to ensure densification24. A comparison between the reported conductivity values of state of the art YSZ and perovskite I also show the superior conductivity at desired fuel cell operating temperature of below 700°C11.

At higher temperatures, the difference in conductivity obtained for perovskite I between wet H2 and other atmosphere is diminished and could be attributed to proton dissolution from the crystal matrix at elevated temperatures29. An increased activation energy of 77 kJmol−1 observed in 3% humidified air against the 55 kJmol−1 under wet hydrogen suggests possible mixed (protons and oxide ions) ionic conductivity. Similar study on acceptor-doped ortho-niobates showed that at temperatures higher than 700°C, contribution of protons towards total conductivity decreased as observed by the decrease in proton transport numbers31.

The open circuit potential (OCP) observed at 700°C was found to be 1.15 V, which clearly reveals the highly dense nature of the membrane. Furthermore, it also confirms that the perovskite I is a pure ionic conductor. Proton transport number studies on similar perovskites demonstrated pure proton conduction up to 700°C under wet conditions11,31 and we believe the same for the investigated perovskite I. Further, the small amount of Ce4+/Ce3+ conversion observed under TGA has not induced significant electronic conductivity as otherwise the OCP would have reduced due to electronic short circuiting. A maximum power density of 18 mWcm−2 is achieved at 700°C for un-optimized thick perovskite I electrolyte with the use of Pt paste as electrodes. The Nyquist plots obtained with perovskite I in fuel cell mode by passing wet H2 and air are in accordance with the plots obtained in wet H2 (Figure 3). A maximum conductivity of about 1 × 10−2 Scm−1 is achieved at 700°C under fuel cell operating conditions.

Methods

Preparation of Ba0.5Sr0.5Ce0.6Zr0.2Gd0.1Y0.1O3−δ (Perovskite I)

High pure (>99.9%) oxide and carbonate precursors, barium carbonate, strontium carbonate, cerium oxide, zirconium oxide, gadolinium oxide and yttrium oxide (Sigma Aldrich) were mixed in the appropriate ratio and ball milled for 6 h using 2-propanol as the solvent. The mixture was than dried and calcined at 1050°C for 24 h followed by further ball milling for 6 h. Thus, prepared powders were uni-axially pressed into pellets using an isotactic press at 200 MPa for 3 minutes and sintered with their parent powders for 24 h at 1450°C.

Chemical stability measurements

Stability under water vapor at 90°C was performed by hanging perovskite I powder above water in a round bottom flask fitted with a condenser for various time durations. Stability under CO2 gas was measured by placing Perovskite I powder inside a quartz tube and flowing pure CO2 at a flow rate of 10 sccm for 24 h at 800°C. To simulate the SOFC operating conditions, 1:1 ratio of N2 and CO2 was purged through water that was kept at 80°C. PXRD and thermogravimetric (TGA) analysis (Mettler Toledo, TGA/DSC/HT1600) were performed on these samples before and after the stability tests. Heating rate during TGA measurements was 10°C/min. For in-situ TGA under CO2 environment, the heating rate was decreased to 5°C/min and a flow of pure CO2 was maintained. In-situ high temperature (HT) – PXRD measurements under various gas environments were performed in a high temperature reactor chamber (Anton Paar XRK 900) from 2θ 10° and 80° at a count rate of 3 s per step of 0.05°. FT-IR measurements were carried out on a Varian 7000 FT-IR spectrometer.

Conductivity measurements

Sintered pellets were cut into smaller disks and both sides were grounded and polished to obtain the desired thickness and flat and parallel surface to one another. Pt paste was brushed on both side as electrodes and fired at 800°C for 2 h. Conductivity was measured using AC impedance analyzer (Solartron electrochemical impedance spectroscopy; SI 1260) at various temperatures and under various environments. Prior to measurement, samples were held at the temperature of measurement for a minimum of 2 h and maximum of overnight. Single fuel cell polarization measurements were carried out by passing humidified H2 and air on the anode and cathode sides, respectively. During heating 5% H2 was supplied and is increased to pure H2 after reaching the desired temperature.

Author Contributions

R.K., S.G. and V.T. designed this research; R.K., K.S. and T.F. carried out the experiments; R.K. and V.T. wrote the paper. K.S., S.G. and T.F. provided the comments.

Supplementary Material

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

This work was performed by the support of Carbon Management Canada, National Centre of Excellence, and the University of Calgary's Institute for Sustainable Energy, Environment and Economy. One of us V.T. thanks the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada and the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) for their support to establish the facilities for materials research at Department of Chemistry, The University of Calgary.

References

- Chu S. & Majumdar A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 488, 294–303 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell S., Speirs J., Bentley R., Miller R. & Thompson E. Shaping the global oil peak: a review of the evidence on field sizes, reserve growth, decline rates and depletion rates. Energy 37, 709–724 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Tao S. & Irvine J. T. S. A redox-stable efficient anode for solid-oxide fuel cells. Nat Mater 2, 320–323 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele P. et al. High proton conduction in grain-boundary-free yttrium-doped barium zirconate films grown by pulsed laser deposition. Nature Materials 9, 846–852 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuer K. D. Proton-conducting oxides. Annual Review of Materials Research 33, 333–359 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo M., Craig A. J. F. & Islam M. S. Oxide-ion and proton conducting electrolyte materials for clean energy applications: structural and mechanistic features. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 4370–4387 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C. Fuel processing for low-temperature and high-temperature fuel cells Challenges, and opportunities for sustainable development in the 21st century. Catalysis Today. 77, 17–49 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Edwards P. P., Kuznetsov V. L., David W. I. F. & Brandon N. P. Hydrogen and fuel cells: towards a sustainable energy future. Energy Policy 36, 4356–4362 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Ryu K. H. & Haile S. M. Chemical stability and proton conductivity of doped BaCeO3–BaZrO3 solid solutions. Solid State Ionics 125, 355–367 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi N., Hatoh K., Niikura J., Gamo T. & Iwahara H. Proton conductive properties of gadolinium-doped barium cerates at high temperatures. Solid State Ionics. 53, 998–1003 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. et al. Enhanced sulfur and coking tolerance of a mixed ion conductor for SOFCs: BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.2−xYbxO3−δ. Science 326, 126–129 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Davies R. A., Islam M. S. & Haile S. M. Atomistic study of doped BaCeO3: dopant site-selectivity and cation nonstoichiometry. Chemistry of Materials 17, 846–851 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner R., Islam M. S. & Norby T. Protons and other defects in BaCeO3: a computational study. Solid State Ionics 122, 145–156 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Hung I. M., Peng H. W., Zheng S. L., Lin C. P. & Wu J. S. Phase stability and conductivity of Ba1−ySryCe1−xYxO3−δ solid oxide fuel cell electrolyte. Journal of Power Sources 193, 155–159 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri E., D'Epifanio A., Di Bartolomeo E., Licoccia S. & Traversa E. Tailoring the chemical stability of Ba(Ce0.8−xZrx)Y0.2O3−δ protonic conductors for intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells (IT-SOFCs). Solid State Ionics 179, 558–564 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Snijkers F. M. M., Buekenhoudt A., Cooymans J. & Luyten J. J. Proton conductivity and phase composition in BaZr0.9Y0.1O3−δ. Scripta Materialia 50, 655–659 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Guo Y., Ran R. & Shao Z. A new neodymium-doped BaZr0.8Y0.2O3−δ as potential electrolyte for proton-conducting solid oxide fuel. Journal of Membrane Science 415, 391–398 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Pagnier T., Charrier-Cougoulic I., Ritter C. & Lucazeau G. A neutron diffraction study of BaCexZr1−xO3. The European Physical Journal - Applied Physics 9, 1–9 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Roedel E., Urakawa A., Kureti S. & Baiker A. On the local sensitivity of different IR techniques: Ba species relevant in NOx storage-reduction. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 10, 6190–6198 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal P., Moghissi O. C., Orazem M. E. & Garcia-Rubio L. H. Application of measurement models for analysis of impedance spectra. Corrosion 49, 278–289 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Boukamp B. A. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy in solid state ionics: recent advances. Solid State Ionics 169, 65–73 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Kannan R., Gill S., Maffei N. & Thangadurai V. BaCe0.85−xZrxSm0.15O3−δ (0.01 < x < 0.3) (BCZS): effect of Zr content in BCZS on chemical stability in CO2 and H2O vapor, and proton conductivity. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 160, F18–F26 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gill S., Kannan R., Maffei N. & Thangadurai V. Effect of Zr substitution for Ce in BaCe0.8Gd0.15Pr0.05O3−δ on the chemical stability in CO2 and water, and electrical conductivity. RSC Advances 3, 3599–3605 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Babilo P., Uda T. & Haile S. M. Processing of yttrium-doped barium zirconate for high temperature proton conductivity. Journal of Material Research 22, 1322–1330 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Serra J. M. & Meulenberg W. A. Thin-film proton BaZr0.85Y0.15O3 conducting electrolytes: toward intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cell alternative. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 90, 2082–2089 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Zuo C., Zha S., Liu M., Hatano M. & Uchiyama M. Ba(Zr0.1Ce0.7Y0.2)O3−δ as an electrolyte for low-temperature solid-oxide fuel cells. Advanced Materials 18, 3318–3320 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H., Kawasaki Y., Ito N., Enoki M. & Ishihara T. Relation between electrical conductivity and chemical stability of BaCeO3-based proton conductors with different trivalent dopants. Electrochemical and Solid-State Letters 10, B77–B80 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Bhide S. V. & Virkar A. V. Stability of BaCeO3-based proton conductors in water-containing atmospheres. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 146, 2038–2044 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Schober T. & Coors W. G. Entry and exit of water vapor in bulk ceramic proton conductors. Solid State Ionics 176, 357–362 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Schober T., Friedrich J., Triefenbach D. & Tietz F. Dilatometry of the high-temperature proton conductor Ba3Ca1.18Nb1.82O9−δ. Solid State Ionics 100, 173–181 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Haugsrud R. & Norby T. Proton conduction in rare-earth ortho-niobates and ortho-tantalates. Nat Mater 5, 193–196 (2006). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information