R-spondins (RSPO1–RSPO4) function in development and stem cell growth by enhancing Wnt pathway activation. Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptors 4–6 (LGR4–6) are receptors for RSPOs. Wang et al. reveal the complex structure of the LGR4 extracellular domain with a RSPO1 N-terminal fragment containing two adjacent furin-like cysteine-rich domains (FU-CRDs). Both the FU-CRD1 and FU-CRD2 domains of RSPO1 contribute to LGR4 binding, and binding and cellular assays identify critical RSPO1 residues for its biological activities. These results provide the structural basis for how LGR4/5/6 receptors recognize RSPOs.

Keywords: Wnt signal, complex, ligand/receptor interaction

Abstract

The R-spondin (RSPO) family of secreted proteins (RSPO1–RSPO4) has pleiotropic functions in development and stem cell growth by strongly enhancing Wnt pathway activation. Recently, leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 4 (LGR4), LGR5, and LGR6 have been identified as receptors for RSPOs. Here we report the complex structure of the LGR4 extracellular domain (ECD) with the RSPO1 N-terminal fragment (RSPO1-2F) containing two adjacent furin-like cysteine-rich domains (FU-CRDs). The LGR4-ECD adopts the anticipated TLR horseshoe structure and uses its concave surface close to the N termini to bind RSPO1-2F. Both the FU-CRD1 and FU-CRD2 domains of RSPO1 contribute to LGR4 interaction, and binding and cellular assays identified critical RSPO1 residues for its biological activities. Our results define the molecular mechanism by which the LGR4/5/6 receptors recognize RSPOs and also provide structural insights into the signaling difference between the LGR4/5/6 receptors and other members in the LGR family.

The R-spondin (RSPO) family is a small group of four secreted proteins (RSPO1–RSPO4) that are widely expressed in vertebrate embryos and the adult (Kim et al. 2006; Yoon and Lee 2011; Cruciat and Niehrs 2012; de Lau et al. 2012; Jin and Yoon 2012). They have pleiotropic functions in development and stem cell growth by strongly enhancing Wnt pathway activation (Kim et al. 2006; Yoon and Lee 2011; Cruciat and Niehrs 2012; de Lau et al. 2012; Jin and Yoon 2012). The functional link between RSPOs and Wnt signaling was established by the identification of Xenopus RSPO2 as a novel activator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Kazanskaya et al. 2004). Other RSPOs from different species have a similar capacity to enhance β-catenin signaling (Yoon and Lee 2011; Jin and Yoon 2012). Mammalian RSPO1–RSPO4 share 40%–60% amino acid sequence identities and consist of a signal peptide, two adjacent furin-like cysteine-rich domains (FU-CRDs) followed by a thrombospondin type I repeat (TSR) domain, and a positively charged C-terminal region (Kamata et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2006). The two FU-CRDs are essential and sufficient to promote Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Kazanskaya et al. 2004; Nam et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2008).

It has been conclusively determined that LGR4 (leucine-rich repeat [LRR]-containing G-protein-coupled receptor [GPCR] 4), LGR5, and LGR6 (Hsu et al. 1998, 2000) are receptors for RSPOs (Carmon et al. 2011; de Lau et al. 2011; Glinka et al. 2011; Liebner et al. 2012; Ruffner et al. 2012). A common feature of the LGR4/5/6 receptors is their expression in distinct types of adult stem cells. LGR5 has already been described as a marker for resident stem cells in Wnt-dependent compartments, including the small intestine, colon, stomach, and hair follicle (Barker and Clevers 2010). LGR6 also serves as a marker of multipotent stem cells in the epidermis (Snippert et al. 2010). LGR4 is widely expressed in proliferating cells (Van Schoore et al. 2005), and its knockout mice show developmental defects in many organs, including bone, kidney, testis, skin, and gall bladder (Mustata et al. 2011). LGR4/5/6 receptors have a central array of 17 LRRs flanked by cysteine-rich sequences at both the N and C termini in the extracellular domain before seven transmembrane helices, and the extracellular domain is essential and sufficient for high-affinity binding with RSPOs (de Lau et al. 2011).

LGR4/5/6 receptors may physically interact with low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6) after RSPO recognition, and thereby RSPOs and Wnt ligands work together to activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling (de Lau et al. 2011; Carmon et al. 2012). RSPOs are also able to promote Wnt/β-catenin signaling by stabilizing the Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors (Hao et al. 2012). Zinc and RING finger 3 (ZNRF3) and its homolog, RING finger 43 (RNF43), are two recently discovered transmembrane E3 ubiquitin ligases that promote turnover of the Frizzled and LRP6 receptors on the cell surface (Hao et al. 2012; Koo et al. 2012). RSPO1 was demonstrated to induce clearance of ZNRF3 from the membrane by interacting with the extracellular domains of LGR4 and ZNRF3, which stabilizes the Frizzled and LRP6 receptors to enhance Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Hao et al. 2012). The RSPO recognition by LGR4/5/6 is critical for Wnt signal enhancement by RSPOs, but its structural basis is still elusive. Here we report the complex structure of the LGR4 extracellular domain (ECD) with the RSPO1 N-terminal fragment (RSPO1-2F) containing FU-CRD1 and FU-CRD2 at a resolution of 2.5 Å.

Results and Discussion

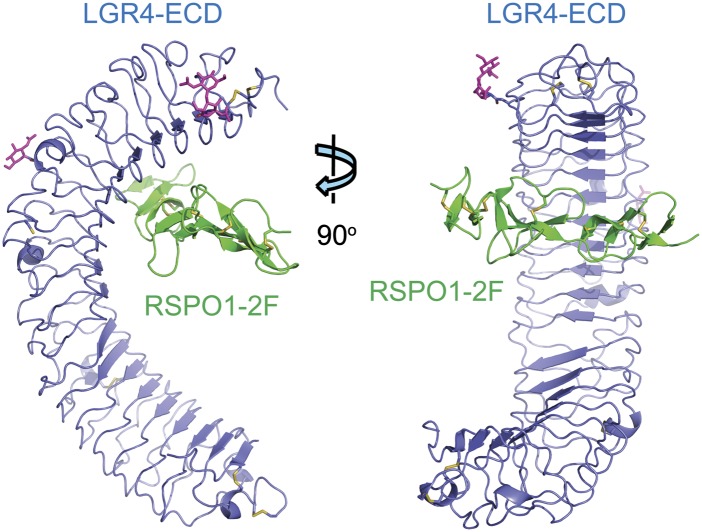

Overall structure of the complex

Sequence annotation of full-length human RSPO1 in the UnitProtKB database (entry code Q2MKA7) shows that the FU-CRD1 and FU-CRD2 domains consist of residues Ala34–Asp85 and Met91–Ala135, respectively. Therefore, we expressed and purified human a RSPO1 fragment (Ala34–Ala135) in baculovirus-infected insect cells and named it RSPO-2F. It bound to the human LGR4-ECD (Ala25–Gly527) with an affinity of 56.5 nM (Supplemental Fig. 1A). It also exhibited a level of activity similar to the full-length RSPO1 in enhancing Wnt3a-induced SuperTopFlash (STF) activation (Supplemental Fig. 1B). The complex of RSPO1-2F with the LGR4-ECD was reconstituted in insect cells by coinfection of two recombinant baculoviruses (Supplemental Fig. 1C), and its crystal structure was determined to be 2.5 Å by molecular replacement method (Supplemental Table 1; Supplemental Fig. 2). The LGR4-ECD adopts the anticipated TLR horseshoe structure (Fig. 1). It uses its concave surface close to the N termini to bind RSPO1-2F, and these two molecules are aligned perpendicularly like a cross in the complex (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overall structure of RSPO1-2F (green) in complex with the LGR4-ECD (blue). Disulfide bonds are drawn as yellow sticks, and N-linked glycans are drawn as violet sticks.

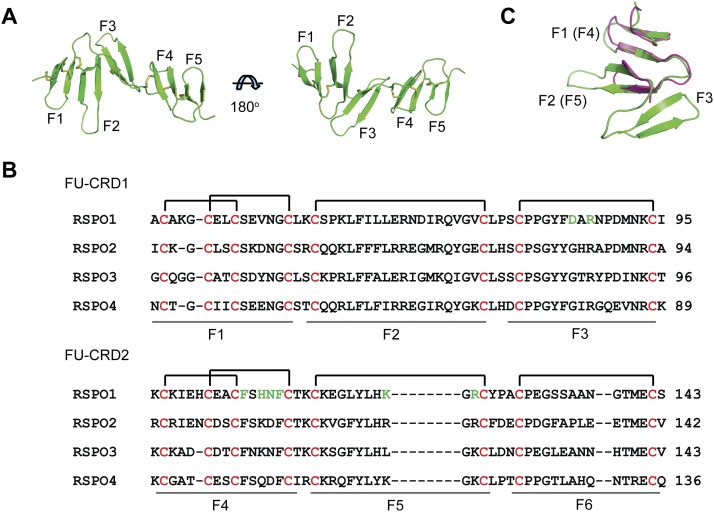

Structure of RSPO1-2F

The final RSPO1-2F model consists of residues Ala39 to Ala128, and the N-terminal Ala34 to Gln38 and C-terminal Cys129 to Ala135 residues were not built due to weak electron densities. It is composed of five adjacent and nearly parallel aligned “fingers” (F1–F5), each finger consisting of two anti-parallel β strands and connecting loops fixed by disulfide bonds (Fig. 2A). These fingers can be grouped into two types based on different disulfide bond links. In one type (C2), adopted by F1 and F4, two disulfide bonds link four cysteines in the pattern of Cys1–Cys3 and Cys2–Cys4 (Fig. 2A,B). In the other type (C1), adopted by F2, F3, and F5, a single disulfide bond contributes to the conformation constraint by linking the N and C termini of the finger (Fig. 2A,B). The RSPO1-2F model and sequence alignment show that sequence annotation of FU-CRDs in the UnitProtKB database is not accurate. The FU-CRD1 and FU-CRD2 domains should consist of residues Ala34–Ile95 and Lys96–Ser143 (Fig. 2B), respectively. They adopt the same C2–C1–C1 architecture (F1, F2, and F3 in FU-CRD1, and F4, F5, and F6 in FU-CRD2) (Fig. 2B). The F6 finger (Cys129–Ser143) is not included in the model due to truncation in protein expression construct design (Ala34–Ala135) and weak electron densities at the C terminus (Cys129–Ala135). Structural alignment also shows that FU-CRD1 and FU-CRD2 are structurally similar (Fig. 2C). The cysteines in the FU-CRDs are strictly conserved in all human RSPOs (Fig. 2B), indicating their importance in fixing the conformation of this region for receptor binding. Consistently, most of the missense mutations in human RSPO4 (Blaydon et al. 2006) resulting in developmental defects occur at the cysteine position in the FU-CRDs.

Figure 2.

Structure of RSPO1-2F. (A) Ribbon model of RSPO1-2F, consisting of five “fingers” (F1–F5). (B) Sequence alignments show that cysteines in FU-CRD1 and FU-CRD2 are strictly conserved in RSPO1–RSPO4, and these two domains have the same disulfide bond pattern. RSPO1 residues involved in the interaction with the LGR4-ECD are colored green. (C) Consistent with the same disulfide bond pattern, structural superimposition shows that FU-CRD1 (green) and FU-CRD2 (violet) have similar overall folds, although the F6 finger is missing in the RSPO1-2F model due to protein expression truncation and weak electron densities.

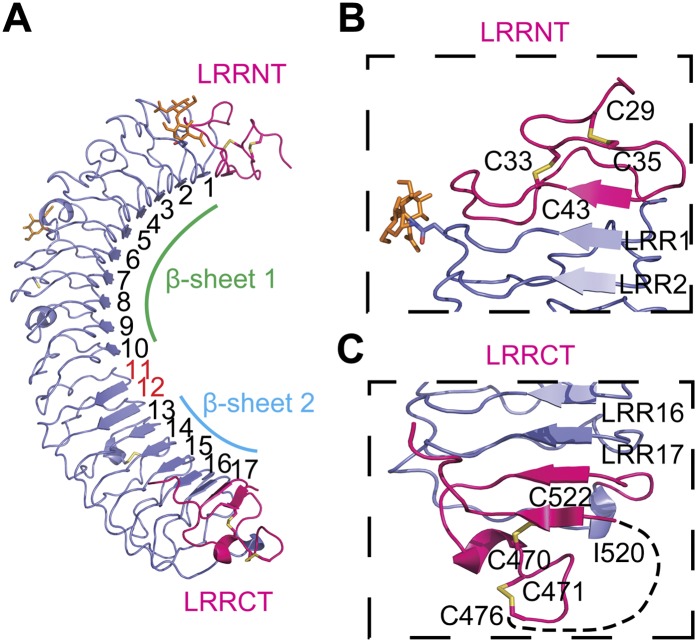

Structure of the LGR4-ECD

The final LGR4-ECD model adopts the anticipated TLR horseshoe structure and is composed of 17 complete LRR modules flanked by disulfide-bonded cap-like structures at the LRR N-terminal end (LRRNT) and LRR C-terminal end (LRRCT) (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. 3). In the signature “LxxLxLxxNxL” motif of the LRR module (Bella et al. 2008), the “N” position is replaced with alanine and threonine in LRR11 and LRR12, respectively, whereas it is strictly conserved as asparagine in other LRR modules (Supplemental Fig. 3). Therefore, the asparagine ladder that helps maintain the smooth curved β sheet in the concave surface of continuous LRR modules is disrupted in LRR11 and LRR12, resulting in the formation of two separate smooth β sheets (LRR1 to LRR10 in β sheet 1, and LRR13 to LRR17 in β sheet 2) (Fig. 3A). LGR5 and LGR6 also have 17 complete LRR modules, including noncanonical LRR11 and LRR12 with alanine in the “N” position, and these LRR modules are also capped by LRRNT and LRRCT (Supplemental Fig. 3). This suggests that LGR5 and LGR6 adopt an extracellular architecture similar to that of the LGR4-ECD.

Figure 3.

Structure of the LGR4-ECD. (A) Ribbon model of the LGR4-ECD, consisting of LRRNT (red), 17 LRR modules (blue), and LRRCT (red). Disulfide bonds and N-linked glycans are represented by yellow and orange sticks, respectively. Two smooth curved β sheets in the concave surface, LRR1–LRR10 (β sheet1) and LRR13–LRR17 (β sheet 2), are separated by LRR11 and LRR12 modules. Zoomed views of LRRNT and LRRCT are shown in B and C, respectively. The disordered Asp477–Ile519 region in the LRRCT is represented by a dashed line.

The LRRNT (Ala25–Ala57) of the LGR4-ECD is a typical β-hairpin capping structure in which a β strand parallel to LRR1 participates in the formation of β sheet 1. The four cysteines, forming Cys29–Cys35 and Cys33–Cys43 disulfide bonds, are conserved in LGR5 and LGR6 (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. 3). The LRRCT of the LGR4-ECD is composed of two ordered structural motifs (Phe456–Cys476 and Ile520–Gly527), and the disordered Asp477–Ile519 region between them is not built into the final model due to weak electron densities (Fig. 3C). Major secondary structure elements in the first motif (Phe456–Cys476) include a β strand parallel to LRR17 and a subsequent short helix (Fig. 3C). Primary sequence analysis shows that it can be regarded as a noncanonical CF3 (C-terminal cysteine-containing flanking domain) motif of LRRs (Kajava 1998). The previously reported canonical CF3 motif containing three cysteines is GPCR-specific (Supplemental Fig. 4A; Kajava 1998). However, the amino acid distance between the third Cys476 and the front two consecutive Cys470 and Cys471 in LGR4/5/6 is shorter than in the canonical CF3 motif (Supplemental Fig. 4A). The second motif (Ile520–Gly527) is at the C-terminal end of the LGR4-ECD and also contains a β strand parallel to the one in the first motif (Fig. 3C). These two parallel β strands in the LRRCT form an extension of β sheet 2 of the LRR region (Fig. 3C). There are five conserved cysteines the LRRCT of LGR4/5/6 (Supplemental Fig. 4A). The last Cys532 was truncated in the expressed and purified LGR4-ECD, the resting four cysteines form two disulfide bonds (Cys470–Cys522 and Cys471–Cys476), and the first one couples two structural elements together (Fig. 3C).

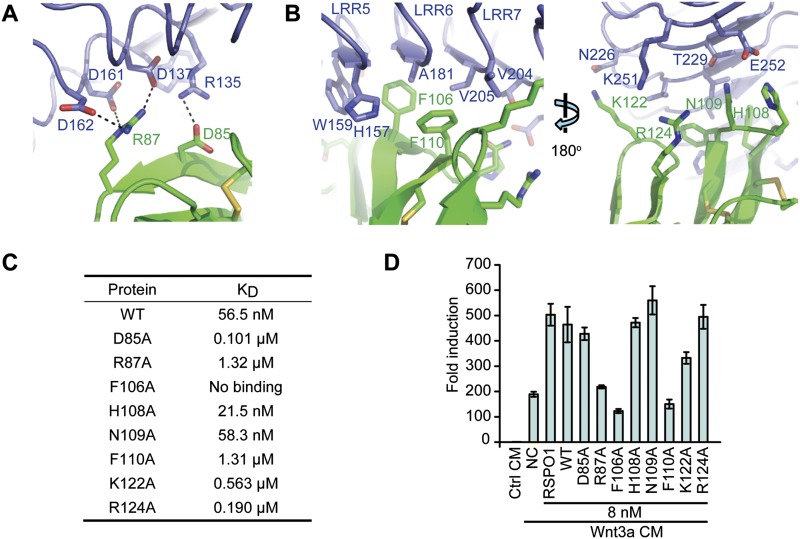

RSPO1–LGR4 interaction

The LGR4-ECD uses the concave surface of the first β sheet to interact with both FU-CRD1 and FU-CRD2 of RSPO1-2F (Fig. 1). The interacting residues of the LGR4-ECD are from the LRR3–9 modules, while interacting residues of RSPO1-2F are from fingers F3, F4, and F5 (Supplemental Table 2). The binding interface can be divided into two subinterfaces based on the involvement of either FU-CRD1 or FU-CRD2 in the binding and their difference in chemical nature. Subinterface I, involving FU-CRD1, primarily consists of salt bridge interactions (Fig. 4A). Acidic Asp85 from the FU-CRD1 F3 finger has salt bridge interactions with basic Arg135 from the LRR4 module of the LGR4-ECD, and basic Arg87 from the same finger has salt bridge interactions with three aspartic acid residues of the LGR4-ECD (Asp137 from LRR4, and Asp161 and Asp162 from LRR5) (Fig. 4A). Subinterface II, involving FU-CRD2, is much more hydrophobic than subinterface I in chemical nature. Phe106 and Phe110 from the F4 finger of FU-CRD2 form a hydrophobic cluster with His157 and Trp159 from LRR5, Ala181 from LRR6, and Val204 and Val205 from LRR7 of the LGR4-ECD (Fig. 4B). His108, Asn109, Lys122, and Arg124 of RSPO1-2F and Glu252, Thr229, Asn226, and Lys251 of the LGR4-ECD are involved in the hydrophilic interactions surrounding the hydrophobic cluster at subinterface II (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Binding interface and effects of single-point mutations of RSPO1-2F at the interface for binding the LGR4-ECD and enhancing Wnt/β-catenin signaling. (A) Subinterface I between FU-CRD1 of RSPO1-2F and LGR4-ECD. Charged RSPO1 residues Asp85 and Arg87 and LGR4 residues Arg135, Asp137, Asp161, and Asp162 form salt bridge interactions that are represented by dashed lines. (B) Subinterface II between FU-CRD2 of RSPO1-2F and the LGR4-ECD. (Left panel) Hydrophobic interactions of RSPO1 residues Phe106 and Phe110 with LGR4 residues His157, Trp159, Ala181, Val204, and Val205. (Right panel) Hydrophilic interactions of RSPO1 residues His108, Asn109, Lys122, and Arg124 with LGR4 residues Asn226, Thr229, Lys251, and Glu252. (C) Binding affinities (KD) of wild-type RSPO1-2F and its mutants with the LGR4-ECD. Sensograms with sample concentrations are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1A. (D) Wnt3a-induced STF reporter assay. STF reporter assays were carried out in HEK293T cells. Plasmids used per well were 15 ng of SuperTopFlash and 0.5 ng of pRL-TK. Protein samples were added with triplicates as indicated. The error bar indicates the SEM of three independent measurements. Full-length human RSPO1 (RSPO1) was used as control. (CM) Conditioned medium; (NC) stands for negative control; (WT) wild-type RSPO1-2F.

RSPO1 critical residues for receptor binding and biological activities

Previous results have shown that both FU-CRD1 and FU-CRD2 are necessary for the biological functions of RSPOs (Kazanskaya et al. 2004). We further explored the roles of specific RSPO1-2F-interacting residues in the abilities of LGR4 binding and Wnt/β-catenin signaling enhancement. In subinterface I, both Asp85 and Arg87 of RSPO1-2F have salt bridge interactions with the LGR4-ECD (Fig. 4A). Mutation of Arg87 (R87A) decreased the binding affinity of RSPO1-2F with the LGR4-ECD by ∼24-fold, from 56.5 nM to 1.32 μM (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. 1A). The RSPO1-2F R87A mutant also lost nearly all of the ability to increase Wnt3a-induced STF activation (Fig. 4D). On the other hand, mutation of Asp85 (D85A) only brought minor changes in both binding affinity and Wnt3a-induced STF activation (Fig. 4C,D; Supplemental Fig. 1A). The more critical role of Arg87 compared with Asp85 in receptor binding and biological activities is also supported by sequence alignment showing that Asp85 is replaced with alanine in RSPO2–RSPO4, whereas Arg87 is strictly conserved in all RSPOs (Fig. 2B). Hydrophobic interactions play more critical roles than hydrophilic interactions at subinterface II. The binding of the RSPO1-2F Phe106Ala mutant (F106A) with the LGR4-ECD was too low to be measured in a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay (Fig. 4C; Supplemental Fig. 1A), and this mutant lost all of the ability to increase Wnt3a-induced STF activation (Fig. 4D). The Phe110Ala mutant (F110A) also bound the LGR4-ECD with low affinity (1.31 μM) and did not increase Wnt3a-induced STF activation (Fig. 4C,D; Supplemental Fig. 1A). His108, Asn109, and Arg124, involved in the hydrophilic interactions, are not critical because their mutants exhibited activities very similar to the wild type in both assays (Fig. 4C,D; Supplemental Fig. 1A). The only exception is Lys122, whose mutation decreased the abilities to bind the LGR4-ECD (0.563 μM) and enhance Wnt3a-induced STF activation (Fig. 4C,D; Supplemental Fig. 1A). These results together elucidate the specific contributions of FU-CRD1 (salt bridge interactions) and FU-CRD2 (hydrophobic interactions) in LGR4/5/6 receptor binding and the critical roles of conserved Arg87, Phe106, and Phe110 for biological activities of RSPOs (Fig. 2B).

Structural insights into signaling differences between LGR4/5/6 and other members of the LGR family

The closely related LGR4/5/6 receptors constitute a distinct group (B) in the LGR family, and two other groups (A and C) in the same family contain receptors follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR; LGR1), LHR (LGR2), and TSHR (LGR3) for glycoprotein hormones and LGR7 and LGR8 receptors for relaxin family of ligands, respectively (Hsu et al. 2000; Kong et al. 2010). The ligand recognition and signaling of FSHR, a representative member in group A of the LGR family, have been extensively studied (Fan and Hendrickson 2005; Ulloa-Aguirre et al. 2007), and the complex structure of the FSHR-ECD with its ligand, FSH, has also been determined (Fan and Hendrickson 2005; Jiang et al. 2012). The LGR4-ECD has an architecture similiar to the FSHR-ECD, including similiar LRRNT, multiple LRR modules (17 in LGR4 and nine in FSHR), and LRRCT. The most significant structure similarity between them exists in the LRRCT region. The LRRCT of the LGR4-ECD consists of two structural motifs (Fig. 3C), and the first one contains a noncanonical CF3 motif (Supplemental Fig. 4A). Similarly, one canonical CF3 motif and one rhodopsin-like extracellular loop in front of the first transmembrane helix have also been observed in the LRRCT (also called a hinge region or signal-specific domain) of FSHR, and their structural arrangement is similar to the two structural elements in the LRRCT of the LGR4-ECD (Supplemental Fig. 4A,B; Jiang et al. 2012). A difference between them resides in the disulfide bond pattern. In the LRRCT of FSHR, there are six cysteines that form three disulfide bonds to couple the two structural motifs (Supplemental Fig. 4A,B), whereas there is only one disulfide bond coupling the structural motifs in the LRRCT of LGR4 (Fig. 3C; Supplemental Fig. 4A).

The LGR4-ECD and FSHR-ECD are structurally similar, and both use the concave surface of continuous LRR modules (LRR3–9 in LGR4 and LRR1–8 in FSHR) to bind their respective ligands. However, the signal transduction pathways after ligand recognition and receptor activation are different between them. Current experimental evidence indicates that the RSPO signaling mediated by the LGR4/5/6 receptors are not through canonical GPCR signaling pathways (Carmon et al. 2011; de Lau et al. 2011; Ruffner et al. 2012); i.e., as cAMP alteration, Ca2+ mobilization, or β-arrestin translocation. This is in contrast to FSHR (LGR1), LHR (LGR2), and TSHR (LGR3), which signal through canonical GPCR signaling pathways upon ligand binding (Birchmeier 2011). Structural and functional studies indicate that full ligand recognition and signaling of FSHR requires a second step interaction of its LRRCT with FSH (Costagliola et al. 2002; Jiang et al. 2012). The initial binding with the LRR region of FSHR reshapes the conformation of FSH to form a pocket. FSHR then inserts its sulfotyrosines from the LRRCT into the FSH nascent pockets, eventually leading to receptor activation and subsequent canonical GPCR signaling pathways (Jiang et al. 2012). The C-terminal part of the LGR4-ECD, including β sheet 2 and the LRRCT, does not interact with RSPO-2F in the complex structure (Fig. 1). Previous functional studies have also shown that deleting the LRRCT region of LGR4 had little effect on RSPO1 activity (Ruffner et al. 2012), and antibodies targeting the C-terminal LRR9-11 modules and LRRCT of LGR5 did not block RSPO1 activity (de Lau et al. 2011). We also know that the TSR domain and the following positively charged C-terminal tails of RSPOs are dispensable for Wnt/β-catenin signaling enhancement (Kazanskaya et al. 2004; Nam et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2008). These structural and functional results together suggest that the binding site observed in the complex structure of RSPO1-2F with the LGR4-ECD is the sole one for RSPO recognition by the LGR4/5/6 receptors. The high-affinity one-site binding of RSPOs with the LGR4/5/6 receptors is expected to form a composite platform for interacting with LRP5/6 to direct potential Wnt/β-catenin signaling or with ZNRF3 to inhibit degradation of the Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors (Supplemental Fig. 5). The second ligand-binding site involving the LRRCT close to the seven-transmembrane domain of FSHR is necessary for its activation and subsequent signaling through coupled heterotrimeric G proteins. The absence of this site in RSPO recognition by the LGR4/5/6 receptors is likely consistent with their noncoupling of heterotrimeric G proteins, at least when stimulated by RSPOs.

Materials and methods

Protein purification and crystallization

Recombinant proteins were expressed using the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system (Invitrogen). In brief, the ORFs of RSPO1-2F, the LGR4-ECD, and the ZNRF3-ECD with an N-terminal gp67 signal peptide to facilitate secretion and a C-terminal 6-His tag were cloned into the pFastBac Dual vector (Invitrogen). After transfection and virus amplification, the high-titer viruses were used to infect Sf9 cells, and the secreted proteins were purified from the medium using Ni-NTA column and gel filtration chromatography. Baculoviruses encoding RSPO1-2F and the LGR4-ECD were coinfected into Sf9 cells to obtain the complex. The crystals were grown using sitting-drop vapor diffusion at 291 K by mixing equal volumes of protein and reservoir solution containing 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 6.0) and 10% (w/v) PEG 6000.

Data collection and structural determination

Crystals were cryo-protected in reservoir solution supplemented with 20% (v/v) glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at the BL17U beam line of the Shanghai Synchrotron Research Facility (SSRF). Diffraction data were indexed, integrated, and scaled with the program HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor 1997). The structure was determined by molecular replacement with PHASER (1994) (McCoy et al. 2007) and refined with PHENIX (Adams et al. 2002). Structure validation was performed with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993).

More detailed procedures, including affinity measurements by SPR and STF reporter assays, are described in the Supplemental Material.

Protein Data Bank (PDB) deposition

The coordinates and diffraction data have been deposited in the PDB with accession code 4KT1.

Acknowledgments

We thank J.W. Wang for assistance with structure determination, and J.H. He and other staff members at the Shanghai Synchrotron Research Facility (SSRF) beam line BL17U for help with data collection. We also thank Y.G. Chen for helpful discussion. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (2010CB912402 and 2011CB910502), the Ministry of Health (2012ZX10001009), and the Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation to X.W., and the Ministry of Science and Technology (2011CB943803) to W.W.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.219360.113.

References

- Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC 2002. PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 58: 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Clevers H 2010. Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptors as markers of adult stem cells. Gastroenterology 138: 1681–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bella J, Hindle KL, McEwan PA, Lovell SC 2008. The leucine-rich repeat structure. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 2307–2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchmeier W 2011. Stem cells: Orphan receptors find a home. Nature 476: 287–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaydon D, Ishii Y, O'Toole E, Unsworth H, Teh M, Ruschendorf F, Sinclair C, Hopsu-Havu V, Tidman N, Moss C, et al. 2006. The gene encoding R-spondin 4 (RSPO4), a secreted protein implicated in Wnt signaling, is mutated in inherited anonychia. Nat Genet 38: 1245–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmon K, Gong X, Lin Q, Thomas A, Liu Q 2011. R-spondins function as ligands of the orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5 to regulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 11452–11457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmon K, Lin Q, Gong X, Thomas A, Liu Q 2012. LGR5 interacts and cointernalizes with Wnt receptors to modulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Mol Cell Biol 32: 2054–2064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costagliola S, Panneels V, Bonomi M, Koch J, Many MC, Smits G, Vassart G 2002. Tyrosine sulfation is required for agonist recognition by glycoprotein hormone receptors. EMBO J 21: 504–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruciat C, Niehrs C 2012. Secreted and transmembrane Wnt inhibitors and activators. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5: a015081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau W, Barker N, Low T, Koo B, Li S, Teunissen H, Kujala P, Haegebarth A, Peters P, van de Wetering M, et al. 2011. Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature 476: 293–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau W, Snel B, Clevers HC 2012. The R-spondin protein family. Genome Biol 13: 242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q, Hendrickson W 2005. Structure of human follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with its receptor. Nature 433: 269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinka A, Dolde C, Kirsch N, Huang Y, Kazanskaya O, Ingelfinger D, Boutros M, Cruciat C, Niehrs C 2011. LGR4 and LGR5 are R-spondin receptors mediating Wnt/β-catenin and Wnt/PCP signalling. EMBO Rep 12: 1055–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao H, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Charlat O, Oster E, Avello M, Lei H, Mickanin C, Liu D, Ruffner H, et al. 2012. ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature 485: 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S, Liang SG, Hsueh AJ 1998. Characterization of two LGR genes homologous to gonadotropin and thyrotropin receptors with extracellular leucine-rich repeats and a G protein-coupled, seven-transmembrane region. Mol Endocrinol 12: 1830–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S, Kudo M, Chen T, Nakabayashi K, Bhalla A, van der Spek P, van Duin M, Hsueh A 2000. The three subfamilies of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptors (LGR): Identification of LGR6 and LGR7 and the signaling mechanism for LGR7. Mol Endocrinol 14: 1257–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Liu H, Chen X, Chen P, Fischer D, Sriraman V, Yu H, Arkinstall S, He X 2012. Structure of follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with the entire ectodomain of its receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 12491–12496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Yoon J 2012. The R-spondin family of proteins: Emerging regulators of WNT signaling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44: 2278–2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajava A 1998. Structural diversity of leucine-rich repeat proteins. J Mol Biol 277: 519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata T, Katsube K, Michikawa M, Yamada M, Takada S, Mizusawa H 2004. R-spondin, a novel gene with thrombospondin type 1 domain, was expressed in the dorsal neural tube and affected in Wnts mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1676: 51–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazanskaya O, Glinka A, del Barco Barrantes I, Stannek P, Niehrs C, Wu W 2004. R-Spondin2 is a secreted activator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and is required for Xenopus myogenesis. Dev Cell 7: 525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Zhao J, Andarmani S, Kakitani M, Oshima T, Binnerts M, Abo A, Tomizuka K, Funk W 2006. R-Spondin proteins: A novel link to β-catenin activation. Cell Cycle 5: 23–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Wagle M, Tran K, Zhan X, Dixon M, Liu S, Gros D, Korver W, Yonkovich S, Tomasevic N, et al. 2008. R-Spondin family members regulate the Wnt pathway by a common mechanism. Mol Biol Cell 19: 2588–2596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong C, Shilling P, Lobb D, Gooley P, Bathgate A 2010. Membrane receptors: Structure and function of the relaxin family peptide receptors. Mol Cell Endocrinol 320: 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo B, Spit M, Jordens I, Low T, Stange D, van de Wetering M, van Es J, Mohammed S, Heck A, Maurice M, et al. 2012. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature 488: 665–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM 1993. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr 26: 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- Liebner S, Gong X, Carmon K, Lin Q, Thomas A, Yi J, Liu Q 2012. LGR6 is a high affinity receptor of R-spondins and potentially functions as a tumor suppressor. PLoS ONE 7: e37137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A, Grosse-Kunstleve R, Adams P, Winn M, Storoni L, Read R 2007. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr 40: 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustata R, Van Loy T, Lefort A, Libert F, Strollo S, Vassart G, Garcia M 2011. Lgr4 is required for Paneth cell differentiation and maintenance of intestinal stem cells ex vivo. EMBO Rep 12: 558–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam J, Turcotte TJ, Smith PF, Choi S, Yoon JK 2006. Mouse cristin/R-spondin family proteins are novel ligands for the Frizzled 8 and LRP6 receptors and activate β-catenin-dependent gene expression. J Biol Chem 281: 13247–13257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276: 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffner H, Sprunger J, Charlat O, Leighton-Davies J, Grosshans B, Salathe A, Zietzling S, Beck V, Therier M, Isken A, et al. 2012. R-spondin potentiates Wnt/β-catenin signaling through orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5. PLoS ONE 7: e40976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert H, Haegebarth A, Kasper M, Jaks V, van Es J, Barker N, van de Wetering M, van den Born M, Begthel H, Vries R, et al. 2010. Lgr6 marks stem cells in the hair follicle that generate all cell lineages of the skin. Science 327: 1385–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa-Aguirre A, Zarinan T, Pasapera AM, Casas-Gonzalez P, Dias JA 2007. Multiple facets of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor function. Endocrine 32: 251–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schoore G, Mendive F, Pochet R, Vassart G 2005. Expression pattern of the orphan receptor LGR4/GPR48 gene in the mouse. Histochem Cell Biol 124: 35–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J, Lee J 2011. Cellular signaling and biological functions of R-spondins. Cell Signal 24: 369–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]