Abstract

Plant ARGONAUTE7 (AGO7) assembles RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) specifically with miR390 and regulates the auxin-signalling pathway via production of TAS3 trans-acting siRNAs (tasiRNAs). However, how AGO7 discerns miR390 among other miRNAs remains unclear. Here, we show that the 5′ adenosine of miR390 and the central region of miR390/miR390* duplex are critical for the specific interaction with AGO7. Furthermore, despite the existence of mismatches in the seed and central regions of the duplex, cleavage of the miR390* strand is required for maturation of AGO7–RISC. These findings suggest that AGO7 uses multiple checkpoints to select miR390, thereby circumventing promiscuous tasiRNA production.

Keywords: Argonaute, microRNA, RISC

Introduction

Small RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), have important roles in spatiotemporal regulation of diverse biological processes [1–4]. Small RNAs act via the effector ribonucleoprotein complex called RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), at the core of which lies Argonaute (AGO) protein. Although mature RISC contains a single-stranded small RNA (the guide strand or miRNA strand), both siRNAs and miRNAs are generated as double-stranded RNAs by RNase III enzymes such as Drosha and Dicer in animals and Dicer-like proteins in plants [1–3]. These small RNA duplexes, called siRNA duplexes and miRNA/miRNA* duplexes, are first loaded into AGO to form pre-RISC. Duplex loading requires the activity of the Hsp70/Hsp90 chaperone machinery [5–9], which is proposed to mediate a conformational change in AGO so that it can incorporate bulky small RNA duplexes [5, 7, 10]. Pre-RISC is then matured into RISC by separation of the two strands and ejection of one strand (the passenger strand or miRNA* strand) from AGO. Passenger ejection proceeds through two distinct pathways depending on the complementarity of small RNA duplexes. siRNA-like duplexes with extensive complementarity require cleavage of the passenger strand at the phosphodiester bond between positions 9 and 10 of the passenger strand (across from positions 10 and 11 of the guide strand) for passenger ejection [11–14]. In contrast, miRNA-like duplexes bearing mismatches in the central region are not subject to passenger-strand cleavage but instead undergo slicer-independent passenger ejection [11, 12, 15, 16], which is boosted by mismatches or G–U wobbles in the seed region (positions 2–7 or 8 of the guide strand) or the 3′-supplementary region (positions 12–15 of the guide strand) [12, 15, 16].

Many eukaryotes possess multiple AGOs with specialized functions, and small RNA duplexes are often sorted into different AGOs. In Drosophila, miRNA/miRNA* duplexes and siRNA duplexes are actively sorted into Ago1 and Ago2, respectively, according to their intrinsic structures and the identity of the 5′ nucleotide of the guide strand [10, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20]. The model plant Arabidopsis thaliana has 10 AGO proteins (AGO1–10), each of which has distinct roles in a diverse array of biological processes [21]. For many Arabidopsis AGOs, the identity of the 5′ nucleotide governs sorting of small RNAs; for example, AGO1 prefers 5′ uridine (U), while AGO2 and AGO4 favours 5′ adenosine (A) [22–24]. The identity of the 5′ nucleotide is directly sensed by the nucleotide specificity loop in the MID domain of AGOs [25, 26]. However, not all Arabidopsis AGOs obey this rule. For example, AGO7 specifically binds to miR390, which triggers TAS3 trans-acting siRNA biogenesis and regulates expression of auxin response factors (ARF3 and ARF4) [23, 27], and the sequence of the miR390 is proposed to be required for the specific interaction between AGO7 and miR390 [23]. However, how AGO7 selectively loads miR390/miR390* duplex among other miRNAs and how AGO7 ejects the miR390* strand remain obscure.

Here, by using in vitro RISC assembly system, we demonstrate that the 5′ A of the miR390 strand and the central 3-nucleotide (nt) region of miR390/miR390* duplex are crucial for the interaction with AGO7. Furthermore, despite the existence of mismatches in the central and seed regions, cleavage of the miR390* strand is required for maturation of AGO7–RISC. Thus, assembly of plant AGO7–RISC utilizes multiple checkpoints and a unique passenger ejection mechanism to select miR390 and exclude other miRNAs.

Results and Discussion

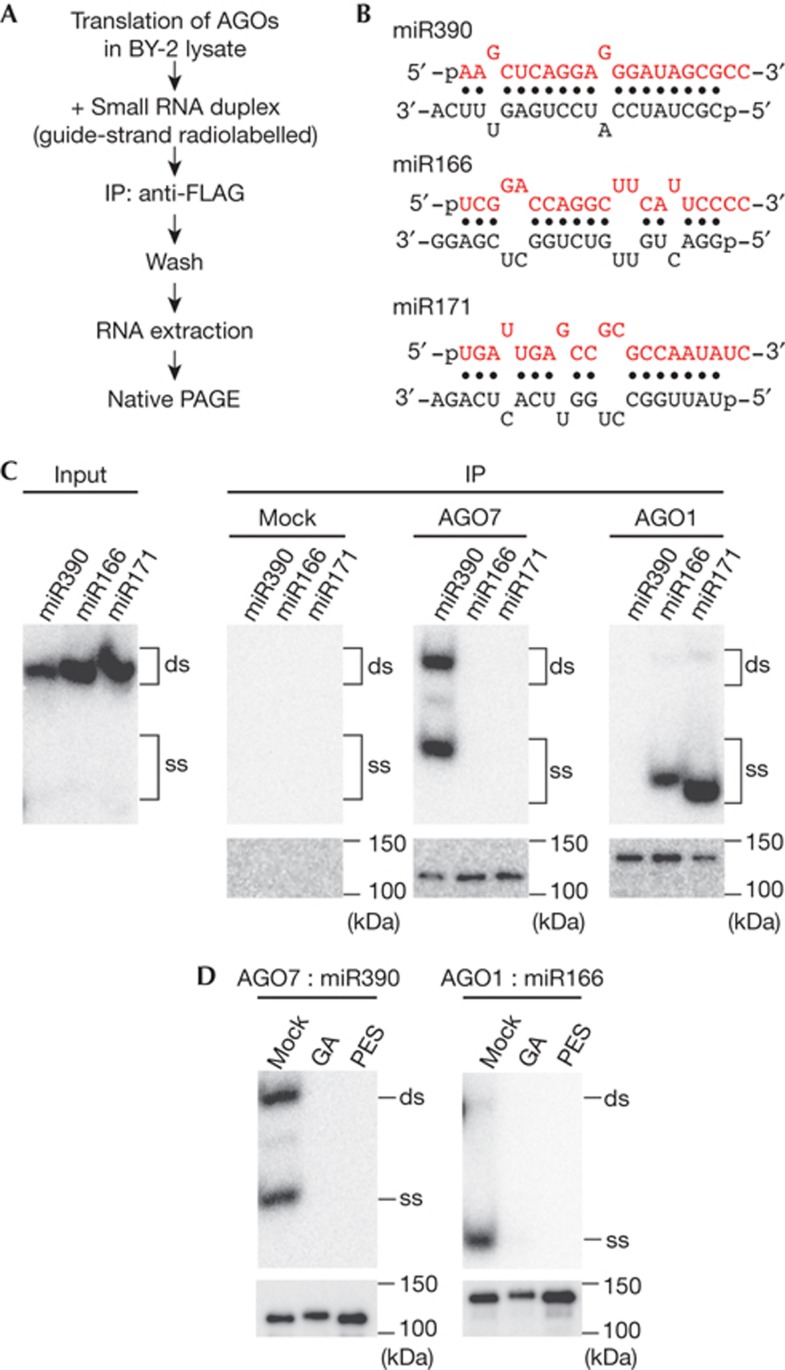

AGO7 specifically associates with miR390 in vitro

To investigate the mechanism of AGO7–RISC assembly, we utilized translationally active lysate from evacuolated protoplasts of tobacco BY-2 cultured cells [5]. First, FLAG-tagged Arabidopsis AGO1 and AGO7 mRNAs were translated in the BY-2 lysate, and subsequently incubated with a series of chemically synthesized small RNA duplexes, of which the guide strands were radiolabelled with 32P (Fig 1A,B). AGO proteins were then immunoprecipitated and the bound double-stranded and single-stranded RNAs were isolated and analysed by native PAGE (Fig 1A,C). No RNAs were detected in the precipitate without AGO translation (Fig 1C). Both double-stranded RNAs (corresponding to pre-AGO7–RISC) and single-stranded RNAs (corresponding to mature AGO7–RISC) were immunoprecipitated with AGO7 for miR390/miR390* duplex, but neither for miR171/miR171* nor miR166/miR166* duplex (Fig 1C). In contrast, AGO1 specifically associated with miR166/miR166* and miR171/miR171* duplexes but not with miR390/miR390* duplex (Fig 1C). These results are consistent with previous in vivo studies showing that AGO1 forms RISC predominantly with small RNAs bearing 5′ U on the guide strand, while AGO7 specifically associates with miR390 [22–24]. Geldanamycin (GA) and 2-phenylethynesulphonamide (PES), which are specific inhibitors of Hsp90 and Hsp70, respectively, blocked loading of miR390/miR390* duplex into AGO7 (Fig 1D), suggesting that AGO7–RISC assembly requires the activity of the Hsp70/Hsp90 chaperone machinery, as is the case for Arabidopsis AGO1, AGO4 and animal AGO proteins [5, 7, 9, 28]. Taken together, we concluded that the plant cell-free system faithfully recapitulates the specificity of AGO7–RISC assembly and decided to use this system for further analyses.

Figure 1.

AGO7 specifically associates with miR390. (A) Scheme for the RISC assembly in BY-2 lysate. (B) The structures of miR390/miR390*, miR166/miR166* and miR171/miR171* duplexes. Red and black strands represent the guide and passenger strands, respectively. The 5′ end of the guide strand was radiolabelled with 32P. (C) RISC assembly in BY-2 lysate. AGO7 specifically associates with miR390/miR390* duplex. In contrast, AGO1 interacts with miR166/miR166* and miR171/miR171* duplex both bearing 5′ U. ‘ds’ and ‘ss’ denote double-stranded miRNAs (pre-RISC) and single-stranded miRNAs (mature RISC), respectively. Western blotting of immunoprecipitated AGO proteins is shown at the bottom. (D) Hsp90 and Hsp70 inhibitors block both AGO1– and AGO7–RISC assembly. RISC was assembled in the presence of an Hsp70 inhibitor (PES), an Hsp90 inhibitor (GA) or DMSO (mock). AGO, ARGONAUTE; DMSO, dimethylsulphoxide; GA, geldanamycin; IP, immunoprecipitation; PES, phenylethynesulphonamide; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex.

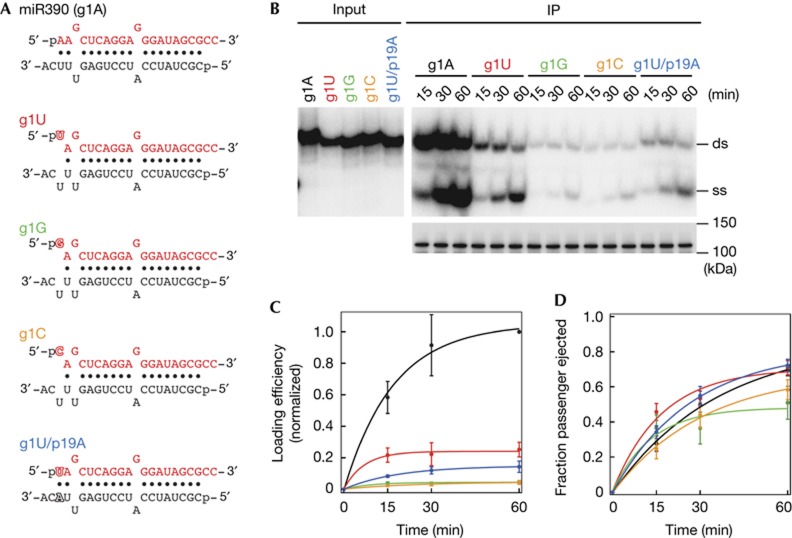

AGO7 prefers 5′ A

The guide strand of miR390 starts with 5′ A. It was previously reported that AGO7 tolerates the conversion of 5′ A to 5′ U for association with miR390 [23]. To quantitatively examine the effect of the 5′ nucleotide in the assembly of AGO7–RISC, we prepared a series of miR390/miR390* variants that bear U, G or C at the 5′ end of the miR390 strand (Fig 2A; g1U, g1G and g1C), and measured the time course of pre-AGO7–RISC and mature AGO7–RISC formation. The duplex loading efficiency was calculated as the sum of pre-AGO7–RISC and mature AGO7–RISC, whereas the passenger ejection rate was calculated as the fraction of mature AGO7–RISC in the sum of pre- and mature AGO7–RISC. Compared with the wild type (g1A), all the mutants showed a marked reduction in duplex loading with the order being A>U>G∼C (Fig 2B,C). In contrast, passenger ejection was comparable among the four 5′ nucleotides (Fig 2B,D). These results indicate that AGO7 inspects the 5′ nucleotide on loading of miR390/mi390* duplex and the preference for 5′ A is maintained during RISC maturation. To rule out the possibility that the 5′ mismatch introduced in the mutants accounts for the reduced duplex loading, we closed the 5′ mismatch of the g1U duplex by introducing A at position 19 of the passenger (miR390*) strand (Fig 2A, g1U/p19A). Much as the mismatched mutant (g1U), the base-paired mutant (g1U/p19A) also showed a strong defect in duplex loading but not in passenger ejection (Fig 2B–D), indicating that AGO7 senses the nucleotide identity, but not the base-paring status, of the 5′ end.

Figure 2.

AGO7 prefers 5′ adenosine. (A) The structures of wild-type miR390/miR390* and its variants bearing the substituted 5′ nucleotide. The mutated nucleotides are outlined. (B) AGO7–RISC assembly using miR390 variants bearing the substituted 5′ nucleotide. The experiment was performed as in Fig 1A. Western blotting of immunoprecipitated AGO7 is shown at the bottom. (C,D) Quantification of duplex loading and unwinding efficiency in (B). The duplex loading efficiency was calculated as the sum of the signal intensity of double-stranded small RNA (pre-AGO7–RISC) and single-stranded small RNA (mature AGO7–RISC), and normalized to the signal of the wild type at 60 min, whereas the rate of passenger ejection was calculated by dividing mature AGO7–RISC by the sum of pre- and mature AGO7–RISC. Substitution of the 5′ nucleotide of the miR390 strand significantly decreased the loading efficiency. The mean values±s.d. from three independent experiments are shown. AGO7, ARGONAUTE7; IP, immunoprecipitation; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex.

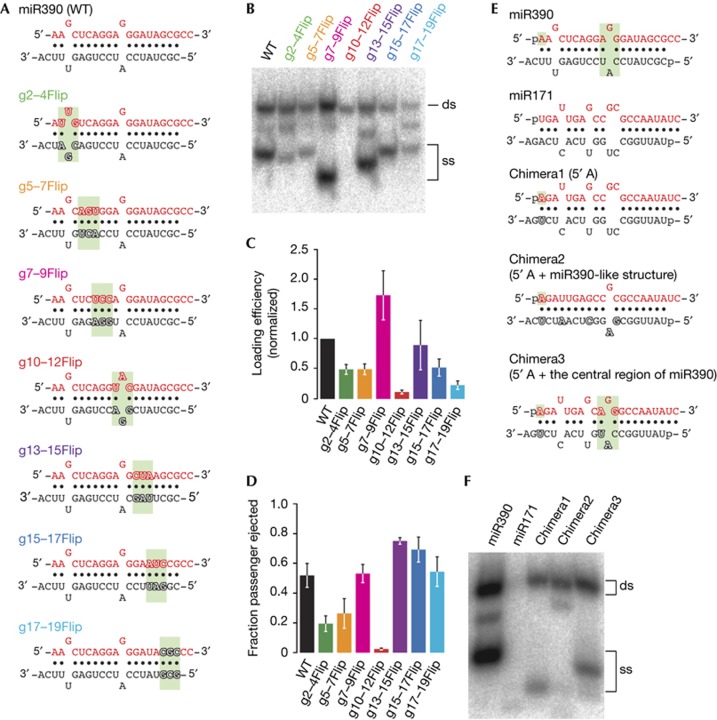

AGO7 inspects the central region of miR390 duplex

Besides miR390, plants have many other miRNAs that bear 5′ A on the guide strand. Thus, AGO7 must also recognize other features of miR390/miR390* duplex for its high selectivity. To investigate what region(s) of miR390/miR390* duplex is inspected by AGO7, we prepared a series of ‘flipped’ mutants of miR390/miR390* duplex, where corresponding parts of the guide and passenger sequences within sliding 3-nt windows were swapped without altering the base-paring status (Fig 3A). Mutations in the seed, central and 3′ regions caused various degrees of defects in RISC assembly (Fig 3B–D). In particular, both duplex loading and passenger ejection were severely compromised by swapping the central 3-nt region (Fig 3B–D, lane 5). Thus, the central region of miR390/miR390* duplex is critical for assembly of AGO7–RISC. In contrast to AGO7, AGO2 efficiently incorporated the miR390/miR390* mutant with the flipped central 3-nt (Supplementary Fig S1 online), suggesting that AGO2 does not inspect the central region for RISC assembly. This is consistent with the previous finding that AGO2 incorporates a wide variety of 5′-A small RNAs including viral siRNAs [22–24].

Figure 3.

The central region of miR390/miR390* is critical for AGO7–RISC assembly. (A) The structures of wild-type and flipped mutants of miR390/miR390* duplex. The flipped 3-nt regions are highlighted in green. The mutated nucleotides are outlined. (B–D) AGO7–RISC assembly using miR390 variants bearing flipped 3-nt sequences. The experiment was performed as in Fig 1A. (C,D) Quantification of duplex loading and passenger ejection efficiency in (B). The mean values±s.d. from three independent experiments are shown. (E) The structure of miR390/miR390*, miR171/miR171* and the chimeras between them. The 5′ A and the 3-nt central region of miR390/miR390* duplex are highlighted in green. The mutated nucleotides are outlined. (F) Introducing 5′ A to miR171/miR171* partially rescued duplex loading into AGO7, and the substitution of the central 3-nt region with that of miR390/miR390* produced mature AGO7–RISC. A, adenosine; AGO7, ARGONAUTE7; ds, double-stranded; nt, nucleotide; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex; ss, single-stranded; WT, wild type.

miR390/miR390* duplex has two mismatches: a G–U wobble in the seed region (guide position 3) and a G–A mismatch in the central region (guide position 11). Intriguingly, the central mismatch is perfectly conserved in monocot and eudicot miR390 family (Supplementary Fig S2 online). To investigate the importance of the seed wobble and the central mismatch, we closed one or both of them by introducing base substitutions in the passenger strand (Supplementary Fig S3A online; p17C, p9C, p9C17C), and analysed the formation of pre- and mature AGO7–RISC. Both duplex loading and passenger ejection were hardly affected by removing the seed wobble, but were dramatically impaired by closing the central mismatch (Supplementary Fig S3 B–D online), suggesting that the conserved central G–A mismatch is crucial for AGO7–RISC assembly. We then shifted the position of the G–A mismatch by one nucleotide backward (Supplementary Fig S3E online, g10G/p9C10A; G–A at position 10) or forward (Supplementary Fig S3E online, p8A9C; G–A at position 12) relative to the 3′ end of the guide strand. Compared with the wild-type miR390/miR390* duplex, both g10G/p9C10A and p8A9C duplexes were markedly defective in duplex loading. In addition, g10G/p9C10A duplex was slow in passenger ejection (Supplementary Fig S3F–H online). Thus the G–A mismatch at position 11 of miR390/miR390* duplex is important for AGO7–RISC assembly. Notably, among 299 Arabidopsis miRNA precursors registered in miRBase [29], only miR390/miR390* duplex bears both 5′ A and the G–A mismatch at position 11. Taken together, we conclude that AGO7 recognizes miR390/miR390* duplex primarily by the 5′ A and the 3-nt central region that contains the conserved G–A mismatch at position 11. To confirm this, we created three chimeras between miR171 and miR390: chimera1 bearing 5′ A instead of U, chimera2 that has 5′ A and miR390-like secondary structure, and chimera3 with 5′ A and the central 3-nt region substituted with that of miR390/miR390* duplex (Fig 3E). In contrast to the wild-type miR171/miR171* duplex that does not interact with AGO7, replacing the 5′ U to A partially restored duplex loading (Fig 3F, chimera1). Introducing the miR390-like secondary structure showed no improvement in RISC assembly (Fig 3F, chimera2). However, substitution of the central 3-nt region of miR171/miR171* with that of miR390/miR390* efficiently produced mature AGO7–RISC (Fig 3F, chimera3), supporting the importance of the above-mentioned two primary features. Yet, RISC assembly of the wild-type miR390/miR390* duplex was still more efficient than chimera3, suggesting that other features, presumably in the seed and 3′ regions of miR390/miR90* duplex (Fig 3A–D), are also required for maximum AGO7–RISC assembly.

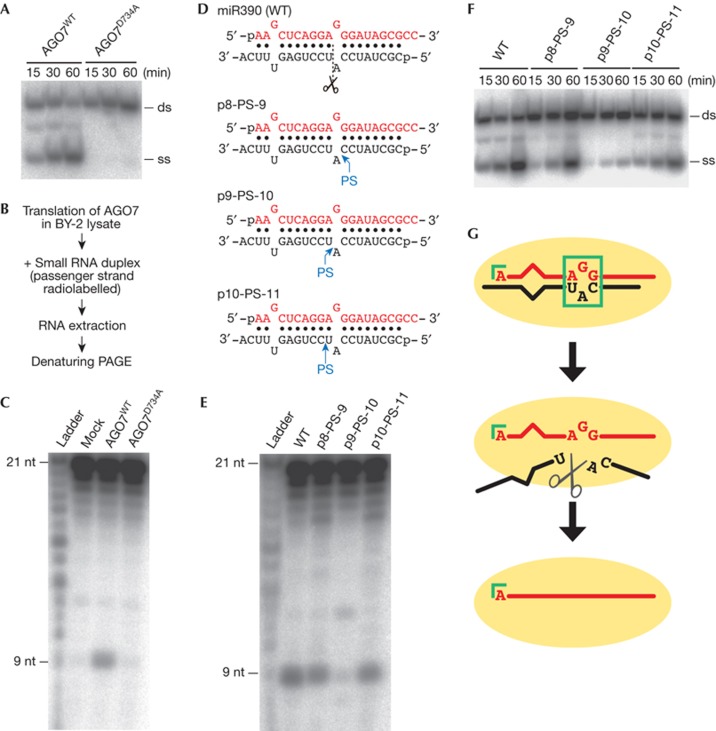

AGO7–RISC maturation requires miR390* cleavage

In general, mismatches in the central region of small RNA duplexes prevent passenger strand cleavage, and mismatches in the seed or 3′-supplementary region accelerate slicer-independent passenger ejection [5, 11, 15, 16]. This is also the case for Nicotiana tabacum AGO1 [5]. Given that miR390/miR390* duplex has a mismatch at position 11 adjacent to the scissile phosphate and an extra mismatch in the seed region, AGO7 is expected to separate the miR390 and miR390* strands independently of cleavage. To test this idea, we constructed a cleavage-incompetent mutant of AGO7 bearing a D734A mutation in the catalytic site in the PIWI domain (AGO7D734A, Supplementary Fig S4 online) and examined in vitro RISC assembly. Contrary to expectation, miR390/miR390* duplex could not be separated in AGO7D734A (Fig 4A), raising a possibility that cleavage of the miR390* strand is required for its ejection by AGO7. To address this, we sought to detect the cleavage product of the miR390* strand by radiolabelling its 5′ end (Fig 4B). Indeed, a 9-nt fragment of miR390* was detected in the BY-2 lysate expressing AGO7WT but not AGO7D734A (Fig 4C), indicating that the miR390* strand was cleaved at the expected position facing positions 10 and 11 of the miR390 strand. Moreover, when a phosphorothioate modification, which blocks cleavage by AGO proteins [12, 30], was introduced between positions 9 and 10 of the miR390* strand (Fig 4D, p9-PS-10), accumulation of the 9-nt fragment was decreased and mature RISC formation was severely inhibited (Fig 4E,F). In contrast, when the position of the phosphorothioate modification was shifted by one nucleotide backward (Fig 4E, p8-PS-9) and forward (Fig 4E, p10-PS-11) relative to the 3′ end of the miR390* strand, miR390* strand cleavage and passenger ejection were comparable to the wild-type miR390/miR390* duplex (Fig 4E,F). Together we conclude that, unlike any known AGOs in animals and plants, cleavage of the miR390* strand is essential for AGO7–RISC maturation, despite the existence of the seed and central mismatches (Fig 4G). We speculate that the local structure around the catalytic site in the PIWI domain of AGO7 adopts a conformation that selectively accommodates the central mismatch of miR390/miR390* duplex and yet is capable of cleaving the miR390* strand at the mismatched nucleotide. This particular conformation, together with the 5′ A-specific specificity loop in the MID domain, might act for AGO7 to reject other miRNAs and specifically assemble RISC with miR390. Clearly, this idea awaits structural studies in the future.

Figure 4.

AGO7 separates miR390/miR390* duplex in a slicer-dependent manner. (A) RISC assembly using catalytic mutant of AGO7 (AGO7D734A). The experiment was performed as in Fig 1A. AGO7D734A was deficient in separating miR390/miR390* duplex. (B) Scheme for the detection of cleaved fragment of the miR390* strand. (C) A 9-nt 5′-cleavage fragment of miR390* was accumulated in BY-2 lysate expressing AGO7WT but not in the lysate expressing AGO7D734A. (D) The structure of wild-type miR390/miR390* and its variants. The dash line in the wild type indicates the scissile phosphate position of miR390*, and ‘PS’ in the variants denotes the phosphorothioate linkage. (E) Phosphorothioate linkage at the scissile phosphate of the miR390* strand decreased accumulation of 9-nt 5′-cleavage fragment of miR390*. (F) Phosphorothioate linkage inhibited ejection of the miR390* strand only when introduced at the scissile phosphate. The experiment was performed as in Fig 1A. (G) A model for AGO7–RISC assembly. The 5′ A of miR390 strand and the central region of miR390/miR390* duplex are important for the interaction with AGO7. Despite the existence of mismatches in the seed and central regions of the duplex, cleavage of the miR390* strand is required for maturation of AGO7–RISC. A, adenosine; AGO7, ARGONAUTE7; ds, double-stranded; nt, nucleotide; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex; ss, single-stranded; WT, wild type.

Methods

Plasmid construction and RNA preparation. Plasmid construction and RNA preparation are described in Supplementary Information online.

Preparation of plant lysates. The BY-2 lysate was prepared as described previously [31].

Preparation of miRNA duplexes. Synthetic RNA oligonucleotides (GeneDesign Inc.) were phosphorylated by T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (Takara) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP or non-radioactive ATP and gel purified. After annealing, radiolabelled miRNA duplexes were quantified using phosphorimager, and the concentrations were normalized by appropriate dilution before used for in vitro RISC assembly assays.

In vitro RISC assembly. Two point five microlitres of the BY-2 lysate, 1.25 μl of substrate mixture (3 mM ATP, 0.4 mM GTP, 100 mM creatine phosphate, 200 nM each of 20 amino acids, 320 nM spermine, 0.4 U/μl creatine phosphokinase (Calbiochem)) and 0.25 μl of 930 nM mRNAs carrying 3 × FLAG-tagged Arabidopsis AGO proteins were incubated for 120 min at 25 °C. Translation was terminated by adding 1 mM cycloheximide. Then the mixture was incubated with 10 nM radiolabelled miRNA duplex. The reaction was mixed with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) immobilized on 1.25 μl of Dynabeads protein G (Invitrogen) and incubated for 30 min on ice. After incubation, the beads were washed three times with lysis buffer (30 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 100 mM KOAc and 2 mM Mg(OAc)2) containing 1% Triton X-100 and 800 mM NaCl and treated with proteinase K. After ethanol precipitation, the samples were resuspended in 6 μl of native loading dye (25% glycerol, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 0.01% xylene cyanol, 0.02% tartrazine and 0.5 × TBE), and 3 μl aliquots were separated on a 12% acrylamide native gel at 4 °C. Gels were analysed by PhosphorImager (FLA-7000, Fujifilm Life Sciences) and quantified using Image Gauge software (Fujifilm Life Sciences). Equimolar amounts of non-radiolabelled miRNA duplexes were used for western blotting of immunoprecipitated AGO proteins in Figs 1C,D, 2B. In Fig 1D, RISCs were assembled in the presence of 1 mM PES, 1 mM GA or 1% dimethylsulphoxide alone. In Fig 3B, lysate was treated with 1 U/μl micrococcal nuclease (Takara) in the presence of 0.5 mM Ca(OAc)2 before adding miRNA duplex. Then, 2 mM EGTA was added to quench the calcium-dependent micrococcal nuclease activity.

Western blotting. Anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) was used at 1:5,000 dilution. Chemiluminescence was measured using Luminata Forte Western HRP Substrate (Millipore), and the signals were detected with LAS-3000 (Fujifilm Life Sciences).

Target cleavage assay. BY-2 lysate containing overexpressed AGO7 was incubated with 10 nM small RNA duplexes and 1 nM cap-radiolabelled target mRNA at 25 °C. At each time point, 3 μl aliquot was taken. After proteinase K treatment and ethanol precipitation, samples were resuspended in 6 μl of Formamide dye (49% Formamide, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% xylene cyanol and 0.01% bromophenol blue), and 3 μl aliquots were separated on an 8% denaturing acrylamide gel. Gels were analysed by PhosphorImager (FLA-7000, Fujifilm Life Sciences).

Passenger-strand cleavage assay. BY-2 lysate containing overexpressed AGO7 was incubated with 10 nM miRNA duplexes containing radiolabelled passenger strands for 30 min at 25 °C. After proteinase K treatment and precipitation, samples were resuspended in 6 μl of Formamide dye, and 3 μl aliquots were separated on a 15% denaturing acrylamide gel. Gels were analysed by PhosphorImager (FLA-7000, Fujifilm Life Sciences). The RNA ladder was prepared by digesting 10 nM radiolabelled miR390* with 1.8 U S1 nuclease (Takara) in the 1 × S1 nuclease buffer (Takara) containing 0.25 μg baker’s yeast tRNA (Sigma) for 5 min at 25 °C. The reaction was quenched by adding 20 mM EDTA.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tetsuro Okuno for providing pBYL2, BY-2 and MM2d cells, and Yuichiro Watanabe and Atsushi Takeda for pCRHA-AGO1L, AGO2 and AGO7. We thank all the members of the Tomari Laboratory for discussion and critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (Functional machinery for non-coding RNAs), a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) from Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. H.I. is a recipient of a JSPS Research Fellowship.

Author contributions: Y.E., H.-o.I. and Y.T. conceived and designed the experiments. Y.E. performed most of the experiments with the help from H.-o.I. Y.E., H.-o.I. and Y.T. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ (2009) Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136: 642–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD (2009) Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet 10: 94–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC (2009) Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 126–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O (2009) Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant microRNAs. Cell 136: 669–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iki T, Yoshikawa M, Nishikiori M, Jaudal MC, Matsumoto-Yokoyama E, Mitsuhara I, Meshi T, Ishikawa M (2010) In vitro assembly of plant RNA-induced silencing complexes facilitated by molecular chaperone HSP90. Mol Cell 39: 282–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iki T, Yoshikawa M, Meshi T, Ishikawa M (2012) Cyclophilin 40 facilitates HSP90-mediated RISC assembly in plants. EMBO J 31: 267–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S, Kobayashi M, Yoda M, Sakaguchi Y, Katsuma S, Suzuki T, Tomari Y (2010) Hsc70/Hsp90 chaperone machinery mediates ATP-dependent RISC loading of small RNA duplexes. Mol Cell 39: 292–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M, Geoffroy MC, Sobala A, Hay R, Hutvagner G (2010) HSP90 protein stabilizes unloaded argonaute complexes and microscopic P-bodies in human cells. Mol Biol Cell 21: 1462–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi T, Takeuchi A, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2010) A direct role for Hsp90 in pre-RISC formation in Drosophila. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 1024–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata T, Tomari Y (2010) Making RISC. Trends Biochem Sci 35: 368–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner PJ, Ameres SL, Kueng S, Martinez J (2006) Cleavage of the siRNA passenger strand during RISC assembly in human cells. EMBO Rep 7: 314–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matranga C, Tomari Y, Shin C, Bartel DP, Zamore PD (2005) Passenger-strand cleavage facilitates assembly of siRNA into Ago2-containing RNAi enzyme complexes. Cell 123: 607–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Tsukumo H, Nagami T, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2005) Slicer function of Drosophila Argonautes and its involvement in RISC formation. Genes Dev 19: 2837–2848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand TA, Petersen S, Du F, Wang X (2005) Argonaute2 cleaves the anti-guide strand of siRNA during RISC activation. Cell 123: 621–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata T, Seitz H, Tomari Y (2009) Structural determinants of miRNAs for RISC loading and slicer-independent unwinding. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16: 953–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoda M, Kawamata T, Paroo Z, Ye X, Iwasaki S, Liu Q, Tomari Y (2010) ATP-dependent human RISC assembly pathways. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 17–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomari Y, Du T, Zamore PD (2007) Sorting of Drosophila small silencing RNAs. Cell 130: 299–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Zhou R, Erlich Y, Brennecke J, Binari R, Villalta C, Gordon A, Perrimon N, Hannon GJ (2009) Hierarchical rules for Argonaute loading in Drosophila. Mol Cell 36: 445–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M, Xu J, Seitz H, Weng Z, Zamore PD (2010) Sorting of Drosophila small silencing RNAs partitions microRNA* strands into the RNA interference pathway. RNA 16: 43–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Liu N, Lai EC (2009) Distinct mechanisms for microRNA strand selection by Drosophila Argonautes. Mol Cell 36: 431–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaucheret H (2008) Plant ARGONAUTES. Trends Plant Sci 13: 350–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S et al. (2008) Sorting of small RNAs into Arabidopsis argonaute complexes is directed by the 5' terminal nucleotide. Cell 133: 116–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery TA, Howell MD, Cuperus JT, Li D, Hansen JE, Alexander AL, Chapman EJ, Fahlgren N, Allen E, Carrington JC (2008) Specificity of ARGONAUTE7-miR390 interaction and dual functionality in TAS3 trans-acting siRNA formation. Cell 133: 128–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda A, Iwasaki S, Watanabe T, Utsumi M, Watanabe Y (2008) The mechanism selecting the guide strand from small RNA duplexes is different among Argonaute proteins. Plant Cell Physiol 49: 493–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank F, Hauver J, Sonenberg N, Nagar B (2012) Arabidopsis Argonaute MID domains use their nucleotide specificity loop to sort small RNAs. EMBO J 31: 3588–3595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank F, Sonenberg N, Nagar B (2010) Structural basis for 5'-nucleotide base-specific recognition of guide RNA by human AGO2. Nature 465: 818–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ, Jan C, Rajagopalan R, Bartel DP (2006) A two-hit trigger for siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell 127: 565–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye R, Wang W, Iki T, Liu C, Wu Y, Ishikawa M, Zhou X, Qi Y (2012) Cytoplasmic assembly and selective nuclear import of Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE4/siRNA complexes. Mol Cell 46: 859–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S (2011) miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D152–D157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz DS, Tomari Y, Zamore PD (2004) The RNA-induced silencing complex is a Mg2+-dependent endonuclease. Curr Biol 14: 787–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komoda K, Naito S, Ishikawa M (2004) Replication of plant RNA virus genomes in a cell-free extract of evacuolated plant protoplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 1863–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.