Abstract

Context:

Animal studies indicate that osteocalcin (OC), particularly the undercarboxylated isoform (unOC), affects insulin sensitivity and secretion, but definitive data from humans are lacking.

Objective:

The objectives of the study were to determine whether total OC and unOC are independently associated with insulin sensitivity and β-cell response in overweight/obese adults; whether glucose tolerance status affects these associations; and whether the associations are independent of bone formation, as reflected in procollagen type 1 amino propeptide (P1NP).

Design, Setting, and Participants:

This was a cross-sectional study conducted at a university research center involving 63 overweight/obese adults with normal (n = 39) or impaired fasting glucose (IFG; n = 24).

Main outcome measures:

Serum concentrations of total/undercarboxylated OC and P1NP were assessed by RIA; insulin sensitivity was determined by iv glucose tolerance test (SI-IVGTT), liquid meal test (SI meal), and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; β-cell response to glucose [basal β-cell response to glucose; dynamic β-cell response to glucose; static β-cell response to glucose; and total β-cell response to glucose] was derived using C-peptide modeling of meal test data; and intraabdominal adipose tissue was measured using computed tomography scanning.

Results:

Multiple linear regression, adjusting for intraabdominal adipose tissue and P1NP, revealed that total OC was positively associated with SI-iv glucose tolerance test (P < .01) in the total sample. OC was not associated with SI meal or homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. In participants with IFG, unOC was positively associated with static β-cell response to glucose and total β-cell response to glucose (P < .05), independent of insulin sensitivity.

Conclusions:

In overweight/obese individuals, total OC may be associated with skeletal muscle but not hepatic insulin sensitivity. unOC is uniquely associated with β-cell function only in individuals with IFG. Further research is needed to probe the causal inference of these relationships and to determine whether indirect nutrient sensing pathways underlie these associations.

The osteoblast-secreted protein osteocalcin (OC) undergoes a vitamin K-dependent carboxylation during synthesis, incorporating up to 3 γ-glutamic acid residues (1). Only the fully carboxylated protein is incorporated into the bone matrix. Both undercarboxylated (unOC) and fully carboxylated forms of the protein can be detected in the circulation.

Over the past 5 years, experimental studies largely conducted in mouse models have suggested that the physiological role of OC extends beyond that of a bone matrix protein and includes the regulation of energy metabolism via effects on insulin secretion and action (2, 3). In particular, the proportion of unOC relative to the carboxylated fraction secreted has been implicated as a metabolic signal, with relatively greater percentage unOC associated with relatively greater insulin sensitivity and secretion. However, concordance in humans has not been definitively established.

Clinical data variably support an association of OC with insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and risk for type 2 diabetes (4–17). In contrast to animal studies, in humans total OC or fully carboxylated OC, rather than unOC, generally have been associated with insulin sensitivity. However, most human investigations to date have used indirect methodologies to determine insulin sensitivity [ie, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)]. HOMA-IR is a surrogate measure of insulin sensitivity based on fasting insulin and glucose that primarily reflects hepatic insulin resistance (18, 19). OGTT-based whole-body measures capture both hepatic and skeletal muscle metabolism (20). In studies in which more sophisticated techniques for determination of insulin sensitivity were used [ie, iv glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) or clamp], an association between OC and insulin sensitivity was observed in lean but not overweight/obese individuals (8, 21). It is possible that the various measures of insulin sensitivity reflect different processes in lean and obese individuals. Given that overweight and obese individuals generally have greater hepatic lipid deposition and hepatic insulin resistance than their lean counterparts (22), it is plausible that indirect or surrogate measures of insulin sensitivity in overweight and obese individuals reflect proportionately greater hepatic than skeletal muscle insulin action. Whether OC is related specifically to hepatic or skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity is not known. A tissue-specific action of OC may explain in part the discrepancies across studies investigating the association between OC and insulin sensitivity; however, this proposition remains to be determined.

In contrast to insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion in humans has been associated with unOC (4, 5). However, these studies used fasting values or postchallenge insulin values, neither of which is considered a robust measure of β-cell function. Fasting insulin values are not relevant for understanding insulin secretory capacity in response to a meal challenge. More importantly, insulin as an outcome measure is confounded by the substantial yet variable extraction of insulin by the liver, which occurs prior to entry into the peripheral circulation. β-Cell response is best assessed under postchallenge conditions by examining the C-peptide response to glucose (23, 24). C-peptide is secreted in equimolar amounts with insulin but is not cleared by the liver. Thus, C-peptide dynamics are a more appropriate measure of insulin secretion and may better reflect the role of OC in energy metabolism.

Human studies concerning OC and insulin action/secretion are challenging to interpret due to difficulty in determining cause vs effect. OC may simply serve as a marker for bone metabolism; it is difficult to dissociate specific effects of OC from more general effects of bone turnover/formation. Insulin may stimulate bone turnover, which could lead to an increased secretion of OC. Inclusion of a marker specific to bone formation, such as procollagen type 1 amino propeptide (P1NP), may help clarify the extent to which observed associations between OC and insulin secretion/action are specific to OC vs simply reflecting bone formation in general.

The objective of this study was to determine associations of total OC and unOC with insulin sensitivity and β-cell response in overweight/obese adults. Three insulin sensitivity tests, having a variable specificity for skeletal muscle vs hepatic insulin action, were used to begin to identify the tissue site with which OC is associated. In addition, we evaluated P1NP as a marker of bone formation to isolate the specific effect of OC from bone formation in general.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Sixty-nine individuals were recruited. Inclusion criteria were body mass index (BMI) of 25–45 kg/m2, weight less than 136 kg, age 21–50 years, not having diabetes, no weight change greater than 2.3 kg over the past 6 months, and successful completion of insulin sensitivity testing. All women were required to be premenopausal, as evidenced by regular menstrual cycles. Exclusion criteria included diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome, regular exercise more than 2 hours per week, pregnancy, current breast-feeding, any disorders of glucose or lipid metabolism, the use of medication that could affect body composition or glucose metabolism [including oral contraceptives, cholesterol medications, and blood pressure medications], current use of tobacco, use of illegal drugs in the last 6 months, a history of hypoglycemic episodes, and a medical history that contraindicated inclusion in the study. None of the participants was taking warfarin or other drugs that may interfere with vitamin K action. Participants were evaluated for glucose tolerance using a 2-hour OGTT, and only those who had 2-hour glucose in the normal or mildly impaired range (≤155 mg/dL) were eligible for the study. However, 24 participants had impaired fasting glucose, as determined by a fasting glucose concentration of 100 mg/dL or greater. Participants were informed of the experimental design, and oral and written consents were obtained. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Use at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB).

Protocol

For 3 days prior to baseline testing, all participants were provided with a standardized diet (55% carbohydrate, 18% protein, 27% fat) calculated to maintain energy balance using the Harris-Benedict formula (25) with an activity factor of 1.35 for females and 1.5 for males. The liquid meal tolerance test and the iv glucose tolerance test were conducted on 2 consecutive days.

Liquid meal tolerance test

Insulin sensitivity and β-cell response to glucose were determined using glucose, insulin, and C-peptide data obtained during a liquid meal tolerance test. Participants were required to fast for 12 hours prior to the test, which was performed starting at between 7:00 and 8:00 am. To perform the test, a flexible iv catheter was placed in the antecubital space of 1 arm. At time zero, a liquid meal was provided [Carnation Instant Breakfast (Nestlé Healthcare Nutrition, Inc, Florham Park, New Jersey) and whole milk)]. The meal was calculated to provide 7 kcal/kg of body weight as 24% fat, 58.6% carbohydrate, and 17.4% protein. Participants were required to consume the meal within 5 minutes. Blood was drawn at −15 and −5 minutes before the initiation of meal consumption (time zero); every 5 minutes from time zero to 30 minutes; every 10 minutes from 30 to 180 minutes; and at 210 and 240 minutes. Sera were stored at −85°C.

The insulin sensitivity index (SI meal) was calculated using a formula based on the insulin and glucose values over the course of the meal test (26) and reflects both insulin inhibition of hepatic glucose production and insulin stimulation of glucose disposal. Because oral glucose does not completely suppress hepatic glucose production (20), oral SI measures are likely to reflect hepatic metabolism to a greater extent than measures that involve iv administration of glucose (eg, the euglycemic clamp or the iv glucose tolerance test), which more effectively suppress hepatic glucose production.

Glucose and C-peptide values were analyzed for measures of β-cell response. Model output from this procedure includes basal (PhiB), dynamic (PhiD), static (PhiS), and total (PhiTOT) β-cell response to glucose. A detailed description of these processes has been published (23). Briefly, PhiB reflects the amount of insulin secreted for a given amount of glucose during basal (fasted) conditions, PhiD the amount of insulin secreted in response to an increase in blood glucose, and PhiS the amount of insulin secreted for a given amount of glucose during nonfasted (above basal) conditions. PhiTOT represents the β-cell response integrated over the entire test.

Intravenous glucose tolerance test

Insulin sensitivity also was determined using an IVGTT. Flexible catheters were placed in the antecubital spaces of both arms. Three blood samples were taken over a 15-minute period to determine basal glucose and insulin (the average of the values was used for basal concentrations). At time zero, glucose (50% dextrose, 300 mg/kg) was given iv. Insulin (0.02 U/kg) was injected at minute 20 after the glucose administration. Blood samples (2.0 mL) were collected at the following times (minutes) relative to glucose administration: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 70, 80, 100, 120, 140, 180, 210, and 240. Sere were stored at −85°C until the analysis. Insulin sensitivity (SI-IVGTT) was derived from glucose and insulin values using minimal modeling (27). SI-IVGTT is correlated with insulin sensitivity as assessed with the euglycemic clamp (r = 0.84, P < .002) (28). Because the iv administration of a large bolus of glucose suppresses the hepatic glucose production in healthy individuals, SI-IVGTT is likely to represent insulin-stimulated glucose disposal to a greater extent than would SI measures based on oral glucose administration.

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

Fasting values of glucose and insulin were used to calculate HOMA-IR, a commonly used surrogate for insulin resistance (19). Because HOMA-IR is based on fasting concentrations of glucose and insulin, it reflects hepatic insulin resistance (29).

Analysis of glucose and hormones

Analyses of glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and P1NP were conducted in the Core Laboratory of UAB's General Clinical Research Center, Diabetes Research and Training Center, and Nutrition Obesity Research Center. Glucose was measured in 3 μL sera using the glucose oxidase method (SIRRUS analyzer; Stanbio Laboratory, Boerne, Texas). This analysis had an intraassay coefficient of variation (CV) of 1.2% and an interassay CV of 3.1%. Insulin was assayed in 50-μL aliquots using immunofluorescence technology on a TOSOH AIA-II analyzer (TOSOH Corp, South San Francisco, California). This analysis had an intraassay CV of 1.5% and an interassay CV of 4.4%. Hemolyzed samples were omitted, which rendered several insulin sensitivity tests unreliable; these tests were not used. C-peptide was assayed in 20-μL aliquots using the TOSOH analyzer (intraassay CV of 1.7% and interassay CV of 2.6%). Intact N terminal P1NP was determined by RIA using reagents obtained from Immunodiagnostic Systems, Inc (Scottsdale, Arizona). The intraassay CV was 2.9% and the interassay CV was 2.4%. Hemolyzed samples were omitted. Analyses of serum total and unOC were conducted at Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut) as described previously (30). This method uses a hydroxyapatite binding step to separate fully carboxylated from unOC prior to RIA. The assay uses a polyclonal antibody that recognizes primarily the intact protein and the 1–43 fragment. Concentrations of carboxylated OC were calculated by subtracting unOC from total OC. Data from 6 individuals were omitted due to hemolysis and subsequent unreliable OC concentrations.

Bone mineral content (BMC)

BMC was determined using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (software version 12.3; GE-Lunar Prodigy, Madison, Wisconsin). Because many of the participants were too large to be accommodated, a half-body scan procedure was used (31), the output from which reports BMC but not bone mineral density.

Body fat distribution

Intraabdominal adipose tissue (IAAT) was analyzed by computed tomography scanning (32) with a HiLight/Advantage scanner (General Electric, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) located in the UAB Department of Radiology. Subjects were scanned in the supine position with arms stretched above their heads. A 5-mm scan at the level of the umbilicus (approximately the L4-L5 intervertebral space) was taken. Scans were analyzed for cross-sectional area (square centimeters) of adipose tissue using the density contour program with Hounsfield units for adipose tissue set at −190 to −30. All scans were analyzed by the same individual. The CV for repeat cross-section analysis of scans among 40 subjects in our laboratory is less than 2%.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables of interest. Means and SD were determined for all subjects combined and within each glucose tolerance subgroup. All outcome measures and covariates were log-10 transformed. Distributions were examined, and data from 1 participant were eliminated due to being an outlier for both insulin sensitivity and total OC.

Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to examine associations of OC and P1NP with measures of insulin sensitivity and β-cell response. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to examine independent associations of all bone markers with insulin sensitivity and β-cell function, adjusting for potentially confounding factors. The models for insulin sensitivity included IAAT as a covariate, whereas those for β-cell function included SI-meal. For the insulin sensitivity models, OC and P1NP were included simultaneously to attempt to isolate unique associations with OC from nonspecific effects of bone metabolism. Analyses were conducted within all participants combined and by glucose tolerance status. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Of the 69 participants who started the protocol, data from 6 were not available for SI-IVGTT and P1NP. Thus, this study included all participants upon whom complete data were available for insulin sensitivity and P1NP (n = 63). Descriptive information on these participants is shown in Table 1. OC data from 6 of those 63 participants were not available yielding a final number of 57 for all analyses involving OC. By design, all subjects were overweight or moderately obese (mean BMI was 33 ± 4 kg/m2). 38% of the sample (n = 24) had impaired fasting glucose (≥100 mg/dL). Normal glucose tolerance (NGT) and impaired fasting glucose (IFG) differed regarding age (P < .05), fasting glucose (P < .001), fasting insulin (P < .01), HOMA-IR (P < .001), IAAT (P < .01), SI-meal (P < .001), PhiB (P < .05), total OC (<0.05), carboxylated OC (P < .01), and P1NP (P = .05). After adjusting for gender, between-group differences in age, fasting glucose, HOMA-IR, IAAT, SI-meal, and PhiB remained significant.

Table 1.

Characteristics (Mean ± SD) of the Study Participants: All Combined and by Glucose Tolerance Status

| All Participants Combined (n = 63) | NGT (n = 39) | IFG (n = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, M/F | 29/34 | 12/27 | 17/7 |

| Ethnicity, EA/AA | 31/32 | 18/21 | 13/11 |

| Age, y | 34.9 ± 8.3 | 33.0 ± 8.4 | 38.1 ± 7.1a |

| Weight, kg | 100.3 ± 19.1 | 95.4 ± 18.4 | 108.2 ± 17.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32.7 ± 4.2 | 31.9 ± 4.2 | 34.0 ± 4.1 |

| IAAT, cm2 | 118.4 ± 52.6 | 105.3 ± 55.8 | 140.8 ± 38.3b |

| BMC, g | 3165.7 ± 603.9 | 3096.7 ± 614.3 | 3270.3 ± 583.5 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 98.4 ± 9.8 | 92.0 ± 5.2 | 108.8 ± 5.8c |

| Fasting insulin, μIU/mL | 12.5 ± 6.6 | 10.7 ± 5.1 | 15.4 ± 7.8b |

| Total OC, ng/mLd | 4.08 ± 1.89 | 3.66 ± 1.86 | 4.70 ± 1.79a |

| Carboxylated OC, ng/mLd | 3.10 ± 1.3 | 2.73 ± 1.29 | 3.64 ± 1.25b |

| unOC, ng/mLd | 0.98 ± 0.76 | 0.93 ± 0.74 | 1.06 ± 0.79 |

| %unOCd | 22.9 ± 10.7 | 23.47 ± 10.94 | 22.06 ± 10.51 |

| P1NP, μg/L | 45.4 ± 15.6 | 42.82 ± 15.57 | 49.59 ± 15.11a |

| SI-meal | 4.09 ± 3.53 | 5.06 ± 3.98 | 2.51 ± 1.78c |

| SI-IVGTT | 2.18 ± 1.66 | 2.22 ± 1.73 | 2.11 ± 1.58 |

| HOMA-IR | 3.09 ± 1.80 | 2.44 ± 1.20 | 4.14 ± 2.11c |

| PhiB, 109 min−1 | 10.4 ± 4.3 | 9.3 ± 3.6 | 12.1 ± 4.8a |

| PhiD, 109 | 527.9 ± 246.2 | 560.0 ± 247.7 | 475.6 ± 239.8 |

| PhiS, 109 min−1 | 72.4 ± 35.8 | 71.2 ± 36.2 | 74.5 ± 35.9 |

| PhiTOT, 109 min−1 | 67.2 ± 33.1 | 68.0 ± 33.6 | 65.8 ± 32.9 |

Abbreviations: AA, African American; EA, European American; F, female; M, male.

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001 for NGT vs IFG.

n = 57 for all OC variables.

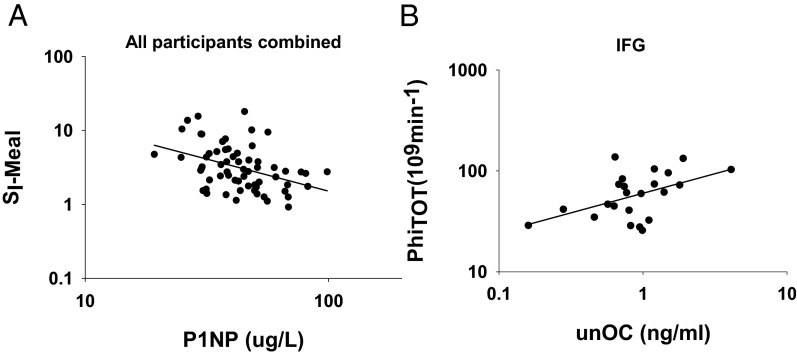

At baseline, among all subjects combined, P1NP was inversely associated with SI-meal, and positively associated with HOMA-IR, PhiB, PhiD, and PhiTOT (Table 2 and Figure 1A). Carboxylated and total OC were inversely associated with SI-meal, and carboxylated OC was positively associated with PhiB. Neither unOC nor percentage of unOC (%unOC) was associated with any measure of insulin sensitivity or β-cell function. In addition, P1NP was positively associated with fasting insulin (r = 0.32, P < .05). When data were examined by glucose tolerance status, the association of P1NP with SI-meal was observed only within the NGT (Table 2), whereas associations of unOC/%unOC with PhiS and PhiTOT were observed only within the IFG (Table 2 and Figure 1B). In most cases, adjustment for gender did not substantially alter the simple correlation results. The only exceptions were the associations between total and carboxylated OC with SI-meal in the combined cohort, which became nonsignificant.

Table 2.

Simple Correlations of Markers of Bone Turnover/Formation With Insulin Sensitivity and β-Cell Function in All Subjects Combined and Within Subjects With Normal and Impaired Fasting Glucose

| P1NP | Carboxylated OC | unOC | %unOC | Total OC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | (n = 63) | (n = 57) | (n = 57) | (n = 57) | (n = 57) |

| SI-meal | −0.40a | −0.28b | −0.22 | −0.08 | −0.30b |

| SI-IVGTT | −0.17 | 0.13 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.12 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.32b | 0.25c | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.26c |

| PhiB | 0.29b | 0.27b | 0.10 | −0.06 | 0.25c |

| PhiD | 0.28b | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.10 |

| PhiS | 0.23c | 0.24c | 0.14 | −0.03 | 0.22 |

| PhiTOT | 0.26b | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| NGT | (n = 39) | (n = 34) | (n = 34) | (n = 34) | (n = 34) |

| SI-meal | −0.41a | −0.16 | −0.22 | −0.13 | −0.19 |

| SI-IVGTT | −0.18 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.27 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| PhiB | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.12 |

| PhiD | 0.41a | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.16 |

| PhiS | 0.20 | 0.25 | −0.02 | −0.24 | 0.17 |

| PhiTOT | 0.22 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.15 | 0.02 |

| IFG | (n = 24) | (n = 23) | (n = 23) | (n = 23) | (n = 23) |

| SI-meal | −0.18 | −0.12 | −0.10 | −0.08 | −0.17 |

| SI-IVGTT | −0.16 | −0.11 | −0.24 | −0.20 | −0.21 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.38c | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.36c |

| PhiB | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.27 |

| PhiD | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| PhiS | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.45b | 0.37c | 0.30 |

| PhiTOT | 0.39c | 0.10 | 0.49b | 0.45b | 0.30 |

P < .01.

P < .05.

.05<P < .10.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted associations between P1NP and SI-meal in all participants combined (NGT and IFG) (r = −0.40, P < .01) (A) and unOC and PhiTOT in participants with IFG (r = 0.49, P < .05) (B).

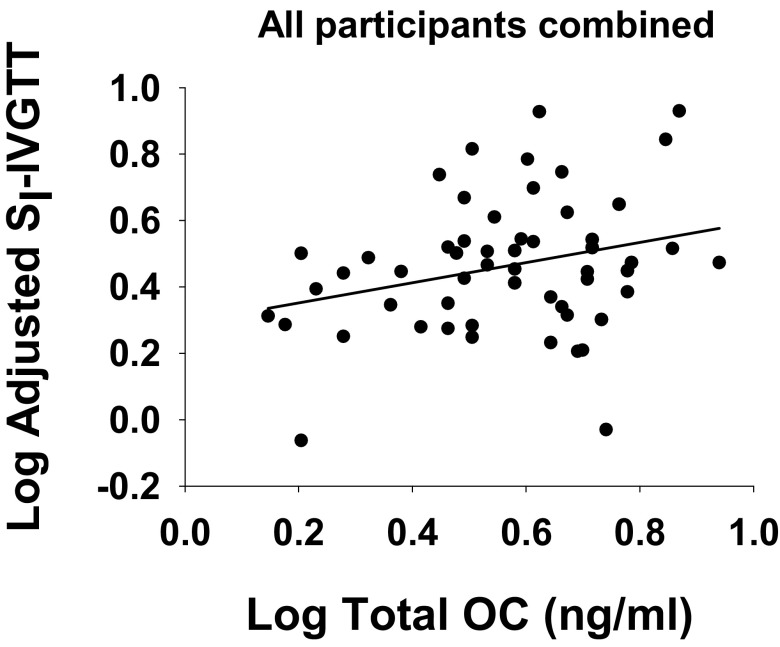

Multiple linear regression analyses were used to examine significant independent associations of OC with each measure of insulin sensitivity, adjusting for P1NP and IAAT (Table 3). SI-meal and HOMA-IR were independently associated with P1NP (inverse) but not with any measure of OC. SI-IVGTT was associated with both P1NP (inverse) and total OC (positive, Figure 2). In all models, addition of gender or race did not alter the results.

Table 3.

Multiple Linear Regression Results for the SI-meal, the SI-IVGTT, and HOMA-IR

| Parameter Estimate | SE | Standardized β | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log SI-meal | ||||

| Intercept | 3.48 | 0.48 | <.001 | |

| Log P1NP | −0.81 | 0.28 | −0.35 | .006 |

| Log total OC | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.07 | .60 |

| Log IAAT | −0.85 | 0.15 | −0.58 | <.001 |

| Log SI-IVGTT | ||||

| Intercept | 1.69 | 0.42 | <.001 | |

| Log P1NP | −0.66 | 0.25 | −0.41 | .011 |

| Log total OC | 0.50 | 0.18 | 0.45 | .006 |

| Log IAAT | −0.22 | 0.13 | −0.22 | .106 |

| Log HOMA-IR | ||||

| Intercept | −1.46 | 0.28 | <.001 | |

| Log P1NP | 0.51 | 0.16 | 0.35 | .004 |

| Log total OC | −0.13 | 0.12 | −0.13 | .261 |

| Log IAAT | 0.61 | 0.09 | 0.66 | <.001 |

Figure 2.

Partial correlation between total OC and SI-IVGTT in all participants combined (NGT and IFG); data are adjusted for IAAT and P1NP (r = 0.28, P < .01).

Likewise, multiple linear regression analyses were used to examine significant independent determinants of PhiS and PhiTOT, adjusting for SI-meal. Analyses were conducted within each glucose tolerance subgroup (Table 4). Only within IFG were significant associations with unOC observed. Among IFG participants, unOC was positively associated with both PhiS (data not shown) and PhiTOT (Table 4). The results were similar for both dependent variables; thus, only data for PhiTOT are shown.

Table 4.

Multiple Linear Regression Results for PhiTOT in NGT and IFG

| Parameter Estimate | SE | Standardized β | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGT | ||||

| Intercept | 1.98 | 0.08 | <.001 | |

| Log SI | −0.32 | 0.10 | −0.48 | .004 |

| Log unOC | −0.10 | 0.18 | −0.09 | .563 |

| IFG | ||||

| Intercept | 1.77 | 0.09 | <.001 | |

| Log SI | −0.50 | 0.15 | −0.52 | .003 |

| Log unOC | 0.67 | 0.24 | 0.44 | .011 |

Discussion

Data from animal models have provided evidence that unOC has unique effects on insulin secretion and action and suggest that bone turnover may participate in the regulation of global energy homeostasis. However, results using human research participants have been inconsistent and often have implicated total or carboxylated OC rather than unOC as being associated with insulin sensitivity. The human studies were limited in many cases by the use of indirect measures of insulin sensitivity and β-cell function. Furthermore, associations of OC with aspects of glucose metabolism may be confounded by nonspecific effects of bone metabolism. The objective of this study was to examine, in healthy overweight/obese humans under energy balance conditions, independent associations of OC with robust measures of insulin sensitivity and β-cell function.

In concordance with the findings of others, we did not observe a relationship between unOC and any measure of insulin sensitivity, suggesting that species differences exist between mouse and humans in this relationship. Rather, we observed that total OC was independently and positively associated with insulin sensitivity as assessed with IVGTT, a measure that likely reflects peripheral (ie, skeletal muscle) insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. This observation is in agreement with 1 previous clinical study that also used the IVGTT (8) and with several studies that used surrogate indices of insulin sensitivity (5, 9, 12, 14). We did not observe an association between OC and HOMA-IR, a fasting measure that reflects hepatic metabolism (18), or with SI-meal, which reflects both hepatic and peripheral insulin action. These observations suggest that any potential effect of OC on insulin sensitivity may occur at skeletal muscle rather than liver. This hypothesis could be tested using tracer-based clamp methods.

In contrast to OC, P1NP was inversely associated with insulin sensitivity and positively associated with HOMA-IR. Serum concentrations of OC and P1NP were correlated (r = 0.62, P < .001 in this sample), yet they appeared to be uniquely associated with measures of insulin sensitivity/resistance. Although both OC and P1NP are produced by bone, P1NP also is produced by the liver (33). It is possible that P1NP of hepatic origin is responsible for the association of circulating concentrations of P1NP with insulin sensitivity/resistance. In addition, without a marker of bone resorption, it is difficult to interpret the P1NP data in the context of bone remodeling. However it is possible that the results indicated that greater bone formation was associated with lower insulin sensitivity and greater fasting insulin. These associations might be mediated by insulin concentration, which is elevated in insulin resistance and stimulates bone formation (3, 34). Furthermore, in other published studies, the bone resorption marker C terminal telopeptide was positively associated with insulin sensitivity (21); insulin sensitivity was inversely associated with bone density (35); and in mice, the enhancement of osteoclast activity increased glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity (36). Thus, whereas lower insulin sensitivity and hyperinsulinemia may promote bone formation, higher insulin sensitivity appears more closely associated with bone resorption than formation. Bone resorption is hypothesized to enhance insulin sensitivity as well as stimulate insulin secretion by way of liberating unOC into the circulation (37). We did not assess bone resorption in this study and therefore could not test this hypothesis. It will be important in future clinical studies to assess the relationships among insulin secretion/action, bone formation/resorption, and all OC isoforms.

The association of bone metabolism with insulin secretion has not been extensively examined in human subjects, particularly using robust measures of β-cell response. We demonstrated a positive association of unOC with measures of postprandial β-cell response to glucose, independent of insulin sensitivity. However, these relationships were observed only in subjects with IFG, suggesting that associations with unOC are evident only during metabolic dysregulation. Similarly, Pollock et al (5) observed that unOC, but not total or carboxylated OC, was related to glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, but not fasting insulin, in a group of children with prediabetes. This association was not observed in NGT children. Thus, in both this study and that of Pollock et al, the association was specific for unOC, for postchallenge insulin secretion, and for participants with impaired fasting or 2-hour glucose. unOC is thought to be released from bone during resorption, in response to insulin signaling (37). Thus, higher insulin in participants with IFG may have been coupled to secretion of unOC via resorption. Markers of bone resorption were not available in this study but might be useful in addressing this possibility in future studies. The pancreatic β-cell has an orphan receptor that is capable of binding OC and mediating signaling events and that is reported to sense nutrient availability (38). However, causal inference cannot be drawn from cross-sectional observation, and investigations into the possibilities that insulin anabolic action at bone elicits secretion of unOC (34) and that indirect nutrient sensing pathways mediate observed associations are warranted.

Strengths of this study were the robust and comprehensive measures of insulin sensitivity and β-cell function as well as assessment of IAAT, a major determinant of insulin sensitivity. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the association between markers of bone formation with measures of β-cell function. Limitations were the use of only overweight/obese study participants; sample heterogeneity regarding race and gender, both of which affect insulin sensitivity and bone metabolism; and the absence of markers of bone resorption. Use of clamp methodology in future studies is needed to verify hypotheses regarding the tissue specificity of the association of total OC with insulin sensitivity.

In conclusion, by using 3 different methods of assessing insulin sensitivity, we were able to determine that OC may be associated specifically with skeletal muscle insulin action, as opposed to hepatic metabolism. We observed an inverse association between P1NP and insulin sensitivity, which implies that bone formation occurs concurrently with insulin resistance, perhaps due to elevated insulin. In this sample, unOC was positively associated with postchallenge β-cell response among subjects with IFG but not NGT. Further study is needed to determine whether this association reflects a cause-and-effect relationship, whether it is associated with bone resorption, and why metabolic health affects the association. Future studies examining tissue-specific associations of OC with insulin sensitivity may help clarify inconsistencies across clinical studies and between clinical and animal model studies.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the help of Caren Gundberg (Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut) for the measurement of osteocalcin. Maryellen Williams and Cindy Zeng (University of Alabama at Birmingham Core Laboratory, Nutrition Obesity Research Center, Diabetes Research and Training Center, Center for Clinical and Translational Science) conducted all other laboratory analyses. This study is registered with clinical trials (NCT00726908).

This work was supported by Grants R01DK67538, M01-RR-00032, UL1RR025777, P30-DK56336, P60DK079626, and R01HL87923-03S1 and a pilot grant from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Center for Metabolic Bone Disease (P30-AR46031).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMC

- bone mineral content

- BMI

- body mass index

- CV

- coefficient of variation

- HOMA-IR

- homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- IAAT

- intraabdominal adipose tissue

- IFG

- impaired fasting glucose

- IVGTT

- iv glucose tolerance test

- NGT

- normal glucose tolerance

- OC

- osteocalcin

- OGTT

- oral glucose tolerance test

- PhiB

- basal β-cell response to glucose

- PhiD

- dynamic β-cell response to glucose

- PhiS

- static β-cell response to glucose

- PhiTOT

- total β-cell response to glucose

- P1NP

- procollagen type 1 amino propeptide

- SI

- insulin sensitivity

- SI meal

- liquid meal test

- UAB

- University of Alabama at Birmingham

- unOC

- undercarboxylated OC

- %unOC

- percentage of unOC.

References

- 1. Hauschka PV, Lian JB, Cole DE, Gundberg CM. Osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein: vitamin K-dependent proteins in bone. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:990–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ducy P. The role of osteocalcin in the endocrine cross-talk between bone remodelling and energy metabolism. Diabetologia. 2011;54:1291–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clemens TL, Karsenty G. The osteoblast: an insulin target cell controlling glucose homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:677–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hwang YC, Jeong IK, Ahn KJ, Chung HY. The uncarboxylated form of osteocalcin is associated with improved glucose tolerance and enhanced β-cell function in middle-aged male subjects. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25:768–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pollock NK, Bernard PJ, Gower BA, et al. Lower uncarboxylated osteocalcin concentrations in children with prediabetes is associated with β-cell function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1092–E1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kindblom JM, Ohlsson C, Ljunggren O, et al. Plasma osteocalcin is inversely related to fat mass and plasma glucose in elderly Swedish men. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:785–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pittas AG, Harris SS, Eliades M, Stark P, Dawson-Hughes B. Association between serum osteocalcin and markers of metabolic phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:827–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fernandez-Real JM, Izquierdo M, Ortega F, et al. The relationship of serum osteocalcin concentration to insulin secretion, sensitivity, and disposal with hypocaloric diet and resistance training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reinehr T, Roth CL. A new link between skeleton, obesity and insulin resistance: relationships between osteocalcin, leptin and insulin resistance in obese children before and after weight loss. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34:852–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shea MK, Gundberg CM, Meigs JB, et al. γ-Carboxylation of osteocalcin and insulin resistance in older men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1230–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kanazawa I, Yamaguchi T, Yamamoto M, et al. Serum osteocalcin level is associated with glucose metabolism and atherosclerosis parameters in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:45–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kanazawa I, Yamaguchi T, Tada Y, Yamauchi M, Yano S, Sugimoto T. Serum osteocalcin level is positively associated with insulin sensitivity and secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes. Bone. 2011;48:720–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hwang YC, Jee JH, Jeong IK, Ahn KJ, Chung HY, Lee MK. Circulating osteocalcin level is not associated with incident type 2 diabetes in middle-aged male subjects: mean 8.4-year retrospective follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1919–1924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hwang YC, Jeong IK, Ahn KJ, Chung HY. Circulating osteocalcin level is associated with improved glucose tolerance, insulin secretion and sensitivity independent of the plasma adiponectin level. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:1337–1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ngarmukos C, Chailurkit LO, Chanprasertyothin S, Hengprasith B, Sritara P, Ongphiphadhanakul B. A reduced serum level of total osteocalcin in men predicts the development of diabetes in a long-term follow-up cohort. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77:42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Livadas S, Katsikis I, et al. Serum concentrations of carboxylated osteocalcin are increased and associated with several components of the polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Bone Miner Metab. 2011;29:201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bullo M, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Fernandez-Real JM, Salas-Salvado J. Total and undercarboxylated osteocalcin predict changes in insulin sensitivity and β cell function in elderly men at high cardiovascular risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:249–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abdul-Ghani MA, Matsuda M, Balas B, DeFronzo R. Muscle and liver insulin resistance indexes derived from the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsuda M, DeFronzo R. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1462–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Basu R, Peterson J, Rizza R, Khosla S. Effects of physiological variations in circulating insulin levels on bone turnover in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1450–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fabbrini E, Magkos F, Mohammed BS, et al. Intrahepatic fat, not visceral fat, is linked with metabolic complications of obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15430–15435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cobelli C, Toffolo G, Dalla Man C, et al. Assessment of β-cell function in humans, simultaneously with insulin sensitivity and hepatic extraction, from intravenous and oral glucose tests. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1–E15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Polonsky KS, Rubenstein AH. C-Peptide as a measure of the secretion and hepatic extraction of insulin. Pitfalls and limitations. Diabetes. 1984;33:486–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harris JA, Benedict FG. A Biometric Study of Basal Metabolism in Man. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution; 1919 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Breda E, Cavaghan MK, Toffolo G, Polonsky KS, Cobelli C. Oral glucose tolerance test minimal model indexes of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2001;50:150–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bergman RN, Ider YZ, Bowden CR, Cobelli C. Quantitative estimation of insulin sensitivity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1979;236:E667–E677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beard JC, Bergman RN, Ward WK, Porte D., Jr The insulin sensitivity index in nondiabetic man. Correlation between clamp-derived and IVGTT-derived values. Diabetes. 1986;35:362–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gundberg CM, Nieman SD, Abrams S, Rosen H. Vitamin K status and bone health: an analysis of methods for determination of undercarboxylated osteocalcin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3258–3266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wilson CP, Petri RM, Gower BA. Half-body scans are a valid alternative to whole-body scans when estimating body composition by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Int J Body Compos Res. 2006;4:75–80 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kekes-Szabo T, Hunter GR, Nyikos I, Nicholson C, Snyder S, Berland L. Development and validation of computed tomography derived anthropometric regression equations for estimating abdominal adipose tissue distribution. Obes Res. 1994;2:450–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Veidal SS, Vassiliadis E, Bay-Jensen AC, Tougas G, Vainer B, Karsdal MA. Procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (PINP) is a marker for fibrogenesis in bile duct ligation-induced fibrosis in rats. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2010;3:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fulzele K, Riddle RC, DiGirolamo DJ, et al. Insulin receptor signaling in osteoblasts regulates postnatal bone acquisition and body composition. Cell. 2010;142:309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abrahamsen B, Rohold A, Henriksen JE, Beck-Nielsen H. Correlations between insulin sensitivity and bone mineral density in non-diabetic men. Diabet Med. 2000;17:124–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ferron M, Karsenty G. Contribution of bone resorption to the control of glucose metabolism. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27 (Suppl 1). Available at http://www.asbmr.org/Meetings/AnnualMeeting/AbstractDetail.aspx?aid=0f58446f-2af4-4360-ade4-4670cd3409ad Accessed April 26, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ferron M, Wei J, Yoshizawa T, et al. Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and energy metabolism. Cell. 2010;142:296–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pi M, Wu Y, Quarles LD. GPRC6A mediates responses to osteocalcin in β-cells in vitro and pancreas in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1680–1683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]