Abstract

Background:

It has been shown that cigarette smoking as well as diabetes mellitus can produce cytomorphometric alterations in oral epithelial cells with the significant increase in the nuclear area (NA) and significant decrease in the cytoplasmic/nuclear ratio in comparison to healthy control. However, the synergistic effect of tobacco smoking and diabetes on the morphology of gingival epithelial cells is not been explored until date.

Aim:

This study was carried out to investigate the effects of diabetes and the synergistic effects of smoking and diabetes on the cytomorphometry of gingival epithelium.

Materials and Methods:

Gingival smears were collected from 30 male subjects diagnosed with type 2 diabetes with (n = 10) or without history of smoking habit (n = 10). Healthy subjects with no history of smoking or diabetes served as the control group (n = 10). The smears were stained using Papanicolaou procedure. The cellular (CA) and nuclear areas (NA) were measured using image analysis software. One-way ANOVA and Tukey-HSD procedure (at P = 0.05) were used to analyze all the parametric variables.

Results:

A statistically significant (P < 0.001) increase in NA and N:C ratio in smoker diabetic group was observed compared to the non-smoker diabetic group and the control group. The non-smoker diabetic group also showed significant increase

Conclusions:

There were significant alterations in the cellular pattern of gingival mucosa cells in a non-smoker diabetic, but the alteration was to a greater extent in smoker diabetics demonstrating a synergistic effect of smoking and diabetes on gingival mucosa.

Keywords: Cytomorphometric analysis, exfoliative cytology, gingival epithelium, smoking habit, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common endocrine metabolic disorders, and its prevalence has been increasing worldwide.[1] It was estimated that the prevalence of diabetes for all age-groups worldwide to be 2.8% in 2000 and will increase to 4.4% in 2030. The total number of people with diabetes is projected to rise from 171 million in 2000 to 366 million in 2030.[2] Type 2 diabetes mellitus is the most prevalent form of the disease, occurring in 90-95% of all diabetic patients.[1] Data suggest that the increases in prevalence and morbidity rate are attributed to changes in diet toward a western style eating pattern and to a greater extent with drinking and smoking.[3] The prevalence of smoking among diabetic patients is probably around 25% in the United States and some countries in the Western Europe.[4]

Several experimental studies[5,6,7] have shown that smoking has negative effects on glucose and lipid metabolism in diabetic as well as in non-diabetic subjects. As a consequence, cigarette smoking is associated with worsening of the metabolic control in diabetic patients, as well as an increased risk for development of microvascular as well as macrovascular complications in diabetes.[7]

Moreover, data also suggest that there is a higher incidence of pathology in the oral tissues of diabetic patients with smoking habits, where gingivitis, periodontitis, candidiasis, and other mucosal manifestations have been reported.[8] It has been also shown that cigarette smoking[9] as well as diabetes mellitus[10] can produce cytomorphometric alterations in oral epithelial cells with the significant increase in the nuclear area (NA) and significant decrease in the cytoplasmic/nuclear ratio in comparison to healthy control. However, the synergistic effect of tobacco smoking and diabetes on the morphology of gingival epithelial cells has not been explored until date. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to investigate the effects of diabetes, and the synergistic effects of smoking and diabetes on cytomorphometry of gingival epithelium using the exfoliative cytology technique. The parameters used to measure cytomorphometric changes were nuclear area (NA), cellular area (CA), and nuclear/cellular ratio (N/C). Comparisons were made between type 2 diabetic subjects and type 2 diabetic subjects with smoking habit and normal healthy subjects.

Materials and Methods

The study group consisted of patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes with or without history of smoking. Healthy subjects with no history of smoking or diabetes served as the control group. Thirty male subjects ranging in age from 40 to 60 years were selected randomly from the outpatient department (OPD) presenting to, dental hospital. The subjects were assigned to one of the three groups consisting of ten subjects in each group.

Group A: Subjects were diabetic with no history of smoking.

Group B: Subjects were diabetic with history of smoking.

Group C (control group): Subjects were non-diabetic with no history of smoking.

All the subjects participated in the study after signing an informed consent form. A comprehensive proforma was also completed detailing name, age, occupation, ethnic group, the number of cigarettes consumed, duration of smoking, presence or absence of alcohol ingestion, ingested alcohol dose and frequency of consumption, smoking status (current/ever/never) at time of diagnosis of diabetes, and relevant medical history. Committee of Ethics in Research at Dental College approved the experimental protocol of the present study.

Subjects with anemia, systemic disease, clinically apparent oral mucosal lesions and previous benign or malignant lesions were excluded from this study. In addition, patients who had drunk any alcoholic beverage more than one glass a week for the last 20 years were not included in the study. Each patient underwent hemoglobin and full blood count estimation as an initial test to detect cases in which anemia might be present.

Subjects belonging to experimental group (group A and B) were assessed for their diabetic status by reviewing medical records for glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels. The HbA1c was considered valid when the record was within the past one month. Random blood sugar was also measured to know the current status for each diabetic patient attending the dental clinic. Diabetic subjects who have other systemic diseases or taking medications other than the diabetic medications were excluded.

Diabetic smokers were defined as those individuals who were diagnosed for diabetes and smoked over 20 filtered cigarettes or more per day for at least 15 years. Smokers were selected according to pack years of smoking. One pack year is equal to 20 cigarettes smoked per day per year. Subjects with history of greater than 15 pack years of smoking were included in the study. Cases with history of unfiltered cigarette, cigar, hookah or beedi smoking, naswar intake, and tobacco chewing in any forms were excluded, because of concentration variation, which may affect the gingival mucosal cells with different intensity. Non-smokers were defined as people who have never smoked.

Collection of smears

Before collection of smears, all the included subjects underwent scaling and root-planning for full mouth and were recalled after 2-week intervals. After 2-week interval, the overall oral hygiene and clinical inflammatory status of the gingiva were assessed by one of the investigators (PVP) by the established gingival index.[11] If found satisfactory, then the subjects were instructed to rinse their mouth thoroughly with normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride). The gingival mucosa was dried with gauze swab to remove surface debris and excess saliva. A sterilized disposable proxabrush (STIM® Interprox Brushes, DENT–AIDS, New Delhi, India) was used to scrape the attached gingiva in upper anterior region. Scrapings were smeared on to the slide. A minimum of four smears samples were taken from each subject that would be sufficient to give 200 cells per subject (50 cells per smears). In order to gather cells from all the layers of the epithelium, a moderate pressure was applied while taking the smear. Collected smears were immediately fixed using spray fixative (RAPID PAP® Spray fixative, Biolab Diagnostics (I) Pvt. Ltd., India) to avoid air drying. Papanicolaou technique (RAPID PAP® stain, Biolab Diagnostics (I) Pvt. Ltd., India) was used to stain the smear. Stained smears were examined under a microscope equipped with a 40× objective (Olympus WPlanFL 160/0, Tokyo, Japan) and a 2.25x video projection lens (Nikon CCTV/Microscope Adapter, Yokohama, Japan). The received images were transmitted to a video camera (CCD 72; Dage MTI, Michigan City, IN) for display on a video monitor (Sony Trinitron, Tokyo, Japan). A screen shot of each slides were captured, saved, and transferred to the computer for image analysis.

Cytomorphometric analysis

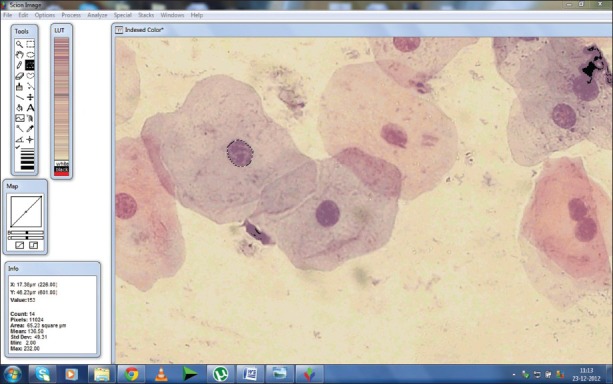

Two hundred cells per subject that were unfolded with clear outline were selected for the study. Cells were analyzed for cellular area (CA), nuclear area (NA), and nucleo-cellular (N/C) ratio using computer software (SCION image for window v. 4.0.3.2, Scion Corporation 82 Worman's Mill Ct., Suite H Frederick, MD 21701). The sampling was done in a stepwise manner, moving the slide from left upper corner to right and then down in order to avoid measuring the same cells again. For measurement, the software was calibrated and scale setting was changed from square pixels to square micrometers (μ2). The instructions were followed as given in the manual of the software for measuring the cell sizes. The nucleus and cell outline was traced using a cursor on the screen, and the software automatically calculated the cell and nuclear area in square micrometers [Figure 1]. The nuclear/cellular ratio (N/C) was calculated then after manually by a digital calculator. Finally, all the recorded data were subjected to statistical analysis.

Figure 1.

Screen-shot demonstrating the measurement of nuclear area using computer image analysis software

Statistical analysis

The study involved multiple groups; therefore, one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) was used for comparing the parameters for multiple groups. Comparison of the mean nuclear, cellular area, and mean nuclear/cellular ratio values between groups was made using multiple comparison tests by Tukey-HSD procedure. The results were reported as mean ± standard deviation. The P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Thirty subjects with age ranging from 40–60 years (mean age 50 ± 6.6 years) years were enrolled in this study. All the subjects were male and shared the common geographic habitat for more than 25 years of their lives. No ethnic/race discrepancy was present between all the included subjects. The diabetic patients either were taking oral hypoglycaemic agents only or combined with insulin. The duration of the diabetes in experimental group ranged from 2 to 14 years; their mean level of random blood sugar (RBS) and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were 170.35 ± 70.43 mg/dL and 8.69 ± 1.48%, respectively. The duration of the smoking habit in the diabetic patients ranged from 15 to 30 years. Four out of ten smoker diabetic patients (group B subjects) started smoking after their diagnosis of diabetic status, whereas remaining six patients were in smoking habits before their diagnosis of diabetes.

The stained gingival epithelial cells were observed for the cellular and nuclear characteristics. The nuclei of epithelial cells of healthy subjects were small and compact with no sign of morphological alterations, whereas the nuclei of epithelial cells of the non-smoker diabetic as well as smoker diabetic were found to be larger and more porous with sign of bi-nucleation and karyorrhexis.

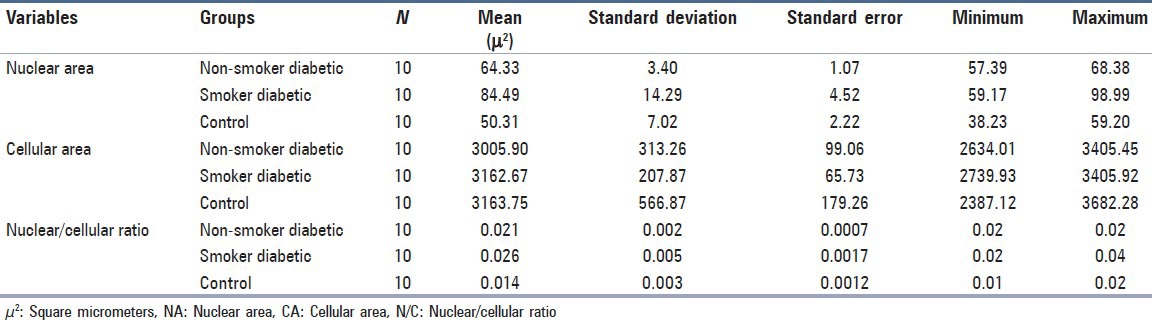

Statistical analysis was carried out to find the difference between measured variables of different groups. The descriptive statistics is shown in Table 1. The result of one-way ANOVA showed that the difference in mean nuclear area F (2, 27) = 33.368, P <0.001 and the difference in mean N/C ratio F (2, 27) = 22.792, P <0.001 between the group were statistically significant, whereas the difference in mean cellular area across all the three groups was not statistically significant, F (2, 27) = 0.535, P = 0.592.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the measured variable of the various groups

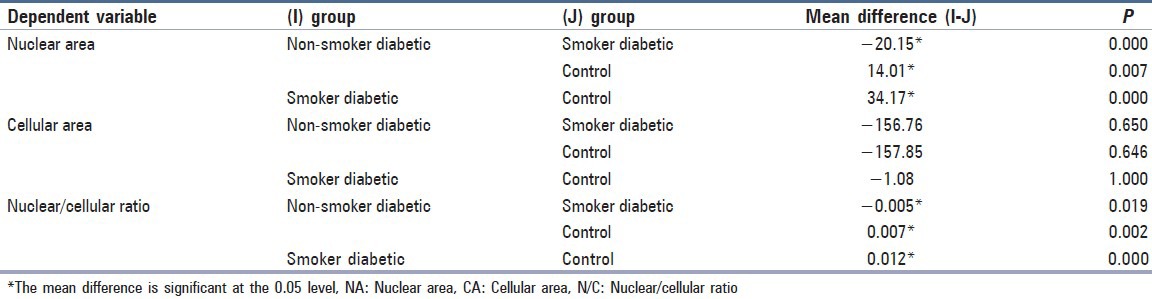

Tukey post-hoc comparisons of the three groups for the difference in nuclear area indicated that the smoker diabetic (M = 84.49, 95% CI 74.26, 94.71) had significantly higher NA than the non-smoker diabetic group (M = 64.33, 95% CI 61.89, 66.76), P < 0.001 and the control group (M = 44.31, 95% CI 39.51, 49.11), P < 0.001, respectively. Comparisons between the non-smoker diabetic group and the control groups also showed statistically significant difference at P < 0.001 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Tukey Post-hoc comparisons of the various groups

Similarly, comparison of the three groups for the difference in nuclear: cellular (N:C) ratio indicated that smoker diabetic group (M = 0.026, 95% CI 0.023, 0.030), P < 0.001 had significantly higher N: C ratio than the non-smoker diabetic group (M = 0.021, 95% CI 0.020, 0.023), P < 0.001 and the control group (M = 0.014, 95% CI 0.0117, 0.0173), P < 0.001, respectively, whereas the comparison of the three groups for the difference in cellular area was not statistically significant at P > 0.05 [Table 2].

Discussion

This study was undertaken to investigate the effects of diabetes, and the synergistic effects of smoking and diabetes on cytomorphometry of gingival epithelium using exfoliative cytology technique. The result showed that the mean nuclear area and mean N/C ratio of keratinocytes was significantly higher in experimental groups (non-smoker diabetics and smoker diabetics) when compared with the control group.

The observed cytomorphometrical changes in the experimental groups can be attributed to the increased cellular age in patients with diabetes. Decreased cellular turnovers might be a secondary reaction to ischemia caused by atherosclerosis in diabetic patients. Thus, as a result of ischemia, cellular turnover would decrease and limited production of young cells would mean that the majority of cells are old or aged.[12] Further, there is one more mechanism as suggested by the Zimmermann and Zimmermann,[13] that is, the difference in cytomorphometry of oral mucosa may be related to difference in recovery rate of keratinizing cells of the oral tissue following systemic endocrine disorder like diabetes.

Nutritional deficiencies have been also associated with changes in oral mucosa, similar to those noted in type 2 diabetic patients. Deficiencies of vitamin B12 and folic acid retard the synthesis of DNA, which is the core substance of cell nuclei, and hence may alter the size of nucleus and cytoplasm.[10,14] Although the qualitative and quantitative changes found in the oral smears of type 2 diabetic patients are features that point to malignancy, it can be differentiated from the latter by the altered N/C ratio and uniformity in the nuclear configuration.

Moreover, previous studies have also suggested that the inflammation is one of the factors that can increase NA and lead to a poorly preserved cytoplasm, but these characteristics are typically found only in young cells and are not representative of cellular atypias.[10,14] In this study, we performed a thorough scaling and root-planning to control the inflammatory factors. Moreover, we took the smears from attached gingiva of upper anterior teeth region to reduce the effect of localized inflammation on our results. We also detected a range of cellular age in the smears, and cytomorphometric alterations were generalized rather than restricted to a certain generation of cells, suggesting that the changes we observed are not just related to inflammation.

On comparing our result with the published results, our result confirms the findings of Alberti et al.[10] and Shareef et al.[15] who investigated the effects of type 2 diabetic mellitus on oral epithelial cells. Both the authors reported a similar nuclear enlargement, karyorrhexis, bi-nucleation and poly-morphonuclear leukocyte infiltration with a significant increase in the nuclear area with no significant difference in cellular area between type 2 diabetics and the control group. There was also a decrease in the cellular/nuclear ratio in type 2 diabetics. Our result is also in agreement in part with Jajarm et al.[16] in terms of NA increase and C/N (cellular/nuclear ratio) decrease in the diabetic group, whereas, opposite to our results Jajarm et al.[16] reported CA increase in the diabetic group when compared to control groups.

Although, in this study, we did not find any sign of candidal infection on any of the smears, the data suggest that the diabetes patients are at high risk of candidal infection due to the immunocompromised state.[17] Moreover, data also suggest that the morphology of non-diabetic candida-infected oral epithelial cells is quite similar to the oral epithelium of the diabetes. In this regard, Loss et al.[18] demonstrated that the cellular area (CA) of the candida-infected epithelial cells was diminished compared to the non-infected controls. In addition, there was an augmentation in nuclear area (NA) and N/C area ratio. Thus, we can assume that diabetic patient with concurrent candidal infection will exhibit more pronounced changes in the size of the oral epithelial cells compared to non-candidal infected diabetic patients.

Our result showed an increase in mean nuclear area and mean N/C ratio of keratinocytes in diabetic with history of smoking but with no significant variation in CA between the groups. Data suggest that the effect of smoking on cytology of the oral tissue is similar to the diabetics. Ogden et al.[19] revealed that the cytomorphometric changes in the buccal mucosal cells of cigarette smokers are similar to those noted in diabetics. This finding is also supported by Ramaesh et al.[9] where quantitative changes found in the buccal mucosa of smokers were attributed to the presence of larger numbers of non-keratinized cells of the parabasal layer. The cells were relatively smaller but have larger nuclei that gave an impression of nuclei enlargement and decreased C/N ratio similar to the changes seen in type 2 diabetic patients.

Our result showed that the cytomorphometric effect was more pronounced in smoker diabetics when compared to the non-smoker diabetics and control groups. However, the synergistic effect has not been explored until date, but the effect of smoking on the cytology of oral cells has been reported by the various authors. Our result is similar to the Ogden et al.[19] who reported that there was a significant elevation in NA for smokers, but no significant variation in CA between smoker and non-smokers. Likewise, our result is also similar to the Ramaesh et al.[9] who reported a significant increase in the NA of cells of smokers compared to non-smokers. Similarly, Einstein and Sivapathasundharam[20] also demonstrated a significant reduction in cell diameter and increase in nuclear diameter in smokers and those with a combined habit of smoking and tobacco chewing, whereas, on the contrary, our result is not in agreement with result of Hillman et al.[21] where they reported an increase in both nucleus size and cell size in smokers with oral carcinoma, but a decrease in cell size in patients who smoked more than 40 cigarettes a day.

Current data suggest that there is a risk of development of malignant or pre-malignant lesion in those patients, who have altered cellular pattern. Several cytomorphometric studies[13,19,20] have demonstrated that CA was highest in normal mucosa, lower in dysplastic lesions and lowest in squamous cell carcinoma (SCCs). By contrast, NA was lowest in normal mucosa, higher in dysplastic lesions and highest in SCCs. These studies[19,20] have suggested that reduced nuclear size/area and increased cytoplasm size/area are useful early indicators of malignant transformation, and thus, exfoliative cytology is of value for monitoring clinically suspect lesions and for early detection of malignancy.

Oral cells for the present study were collected from the gingival tissue of anterior attached gingiva. Most of the published studies[15,16,19,20] have been carried out on the buccal mucosa, palate and tongue, which differ considerably from gingiva both morphologically as well as functionally. Gingiva is a keratinized tissue and is subjected to greater masticatory forces than other parts next to periodontal ligament. It is a region constantly subjected to the deleterious effects of plaque and calculus. The differences seen in gingiva when compared to other regions of oral mucosa may be the result of a cumulative effect of all these factors.[22] Therefore, the cytomorphometrical evaluation of the gingival epithelial cells in the diabetic and/or smoker may provide a varied result from the other anatomic sites in the oral cavity. However, the gingival tissue has been extensively studied for the effect of diabetes when compared to the other oral sites. The biopsy specimen form the gingiva has been reported with the increase in thickness and hyalinization of small capillaries[23] and thickening of the basement membrane[24] in the gingival tissue.

In this study, N:C ratio appeared to be a suitable parameter, which accurately discriminated among the three groups of subjects. Similar observation is also reported by Franklin and Smith[25] where they reported that the N:C ratio has the advantage of relating nuclear volume to cellular volume and possibly represents the significant changes that occur in the cell, more accurately at a morphological level.

Although our result demonstrated a significant cytomorphological changes in the gingival mucosa in diabetics as well as in diabetics with smoking habit, these observed alterations cannot be considered predictive or diagnostic for diabetes, because they are not unique to this disease. Therefore, studies with comparison to other conditions causing similar cytomorphometric changes are needed to determine the predictive value of this method. Moreover, this study is preliminary and the sample size was small, additional studies should be performed to elucidate the actual mechanisms involved in the oral mucosal changes induced by diabetes and/or smoking.

In summary, the results observed in this study might contribute to the general understanding of the alterations in the cellular pattern of gingival mucosa cells in diabetic patients. The result may also provide vital information of synergistic effect of smoking and diabetes to health professionals as well as another diagnostic tool for the verification of clinical diabetes.

Acknowledgment

The present study was financially supported by the Jagadguru Sri Shivarathreeshwara (JSS) University, Mysore, Karnataka (Order Number; REG/EST-l (3) DCH/109/2010-11).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Jagadguru Sri Shivarathreeshwara (JSS) University, Mysore, Karnataka (REG/EST-l (3) DCH/109/2010-11)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH. Global burden of diabetes, 1995-2025: Prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1414–31. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim O, Kim JH, Jung JH. Stress and cigarette smoking in Korean men with diabetes. Addict Behav. 2006;31:901–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Will JC, Galuska DA, Ford ES, Mokdad A, Calle EE. Cigarette smoking and diabetes mellitus: Evidence of a prospective association from a large prospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:540–6. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eliasson B. Cigarette smoking and diabetes. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;45:405–13. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2003.00103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Cornuz J. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;298:2654–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sairenchi T, Iso H, Nishimura A, Hosoda T, Irie F, Saito Y, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus among middle-aged and elderly Japanese men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:158–62. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandberg GE, Sundberg HE, Fjellstrom CA, Wikblad KF. Type 2 diabetes and oral health: A comparison between diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;50:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramaesh T, Mendis BR, Ratnatunga N, Thattil RO. The effect of tobacco smoking and of betel chewing with tobacco on the buccal mucosa: A cytomorphometric analysis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:385–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alberti S, Spadella CT, Francischone TR, Assis GF, Cestari TM, Taveira LA. Exfoliative cytology of the oral mucosa in type II diabetic patients: Morphology and cytomorphometry. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:538–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel PV, Shruthi S, Kumar S. Clinical effect of miswak as an adjunct to tooth brushing on gingivitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:84–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.94611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris HF, Ochi S, Winkler S. Implant survival in patients with type 2 diabetes: Placement to 36 months. Ann Periodontol. 2000;5:157–65. doi: 10.1902/annals.2000.5.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmermann ER, Zimmermann AL. Effects of race, age, smoking habits, oral and systemic disease on oral exfoliative cytology. J Dent Res. 1965;44:627–31. doi: 10.1177/00220345650440040301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koss LG. The oral cavity, larynx, trachea, nasopharynx, and paranasal sinuses. In: Koss LG, editor. Diagnostic cytology and its histopathologic bases. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1992. pp. 865–89. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shareef BT, Ang KT, Naik VR. Qualitative and quantitative exfoliative cytology of normal oral mucosa in type 2 diabetic patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E693–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jajarm HH, Mohtasham N, Moshaverinia M, Rangiani A. Evaluation of oral mucosa epithelium in type II diabetic patients by an exfoliative cytology method. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:335–40. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.50.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill LV, Tan MH, Pereira LH, Embil JA. Association of oral candidiasis with diabetic control. J Clin Pathol. 1989;42:502–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.5.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loss R, Sandrin R, França BH, de Azevedo-Alanis LR, Grégio AM, Machado MÂ, et al. Cytological analysis of the epithelial cells in patients with oral candidiasis. Mycoses. 2011;54:e130–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogden GR, Cowpe JG, Green MW. Quantitative exfoliative cytology of normal buccal mucosa: Effect of smoking. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:53–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1990.tb00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Einstein TB, Sivapathasundharam B. Cytomorphometric analysis of the buccal mucosa of tobacco users. Indian J Dent Res. 2005;16:42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hillman RW, Kissin B. Oral cytologic patterns in relation to smoking habits. Some epithelial, microfloral, and leukocytic characteristics. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;42:366–74. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel PV, Kumar S, Kumar V, Vidya G. Quantitative cytomorphometric analysis of exfoliated normal gingival cells. J Cytol. 2011;28:66–72. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.80745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin JH, Duffy JL, Roginsky MS. Microcirculation in diabetes mellitus: A study of gingival biopsies. Hum Pathol. 1975;6:77–96. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(75)80110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seppala B, Sorsa T, Ainamo J. Morphometric analysis of cellular and vascular changes in gingival connective tissue in long-term insulin-dependent diabetes. J Periodontol. 1997;68:1237–45. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.12.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franklin CD, Smith CJ. Stereological analysis of histological parameters in experimental premalignant hamster cheek pouch epithelium. J Pathol. 1980;130:201–15. doi: 10.1002/path.1711300309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]