Abstract

Background:

The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology represents a major step towards standardization, reproducibility, improved clinical significance, and greater predictive value of thyroid fine needle aspirates (FNAs).

Aims:

To elucidate the utility of the Bethesda system in reporting thyroid FNAs.

Materials and Methods:

We retrospectively reviewed thyroid FNAs between April 2009 and March 2012, classified them using the Bethesda system, found out the distribution of cases in each Bethesda category, and calculated the malignancy risk for each category by follow-up histopathology.

Results:

Of the 1020 FNAs, 1.2% were non-diagnostic, 87.5% were benign, 1% were atypical follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AFLUS), 4.2% were suspicious for follicular neoplasm (SFN), 1.4% were suspicious for malignancy (SM), and 4.7% malignant. Of 69 cases originally interpreted as non-diagnostic, 12 remained non-diagnostic after re-aspiration. In 323 cases, data of follow-up histopathologic examination (HPE) were available. Rates of malignancy reported on follow-up HPE were non-diagnostic 0%, benign 4.5%, AFLUS 20%, SFN 30.6%, SM 75%, and malignant 97.8%.

Conclusions:

Reviewing the thyroid FNAs with the Bethesda system allowed a more specific cytological diagnosis. In this study, the distribution of cases in the Bethesda categories differed from some studies, with the number of benign cases being higher and the number of non-diagnostic and AFLUS cases being lower. The malignancy risk for each category correlated well with other studies. The Bethesda system thus allows standardization in reporting, improves perceptions of diagnostic terminology between cytopathologists and clinicians, and leads to more consistent management approaches.

Keywords: Bethesda system, fine needle aspiration, standardization, thyroid

Introduction

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is the first-line diagnostic test for evaluating thyroid nodules.[1] It is a simple, rapid, and cost-effective test that can effectively distinguish between neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of the thyroid. FNAC can effectively triage patients with neoplastic thyroid nodules as to who require surgery and who do not. However, due to the lack of a standardized system of reporting, pathologists have been using different terminologies and diagnostic criteria, thereby creating confusion amongst referring clinicians in the interpretation of the cytopathology report, ultimately hindering a definitive clinical management.[2,3]

To overcome this issue, multiple organizations have proposed diagnostic guidelines for reporting thyroid FNAC results, including the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology Task Force and the American Thyroid Association, although none have been universally accepted.[4,5]

In the year 2007, the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Bethesda, Maryland, United States, organized the NCI Thyroid Fine Needle Aspiration State-of-the-Science Conference, and an initiative was undertaken to publish an atlas and guidelines using a standardized nomenclature for the interpretation of thyroid fine needle aspirates (FNAs), known as the Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology.[6] The atlas describes six diagnostic categories of lesions: Non-diagnostic/unsatisfactory, benign, atypical follicular lesion of undetermined significance (AFLUS), “suspicious” for follicular neoplasm (SFN), suspicious for malignancy (SM), and malignant.[7] The six diagnostic categories of the Bethesda system have individual implied risks of malignancy that influence management paradigms.[7]

This study was undertaken to elucidate the usefulness of the Bethesda system in reporting thyroid FNAs.

Materials and Methods

In our institute, it is the cytopathologist who performs the procedure of FNAC and procures the aspirate, be it under ultrasound guidance or without guidance. The smears thus prepared are stained by Leishman-Giemsa and Papanicolaou stains and reporting is done within 24 hours.

In the present study, we retrospectively collected thyroid FNAC slides reported in our institute between April 2009 and March 2012 and reviewed them by three cytopathologists as per the current recommended Bethesda nomenclature.

Non-diagnostic or unsatisfactory

A smear was categorized as non-diagnostic if it did not fulfill the adequacy criteria laid down by the Bethesda system.[8] For a solid nodule, a specimen was considered adequate if it contained at least six well-preserved and well-stained follicular groups, containing at least ten cells. In contrast, abundant thick colloid, as found in a colloid nodule, did not have a requirement for a minimum number of follicular cells. Thyroid cysts containing histiocytes but with little or no follicular cells were interpreted as non-diagnostic. An aspirate smear containing significant cytological atypia, was never considered inadequate, regardless of cellularity.

Benign

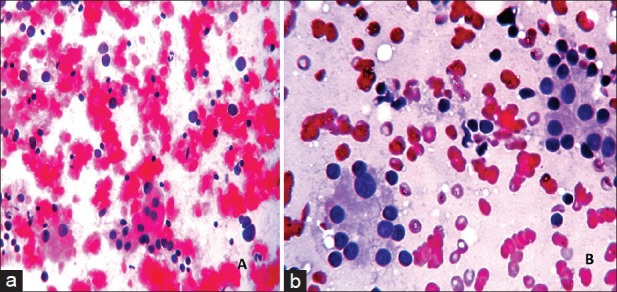

Cases were interpreted as benign if they showed the cytomorphological features of colloid goiter/adenomatoid goiter, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, thyrotoxicosis, de Quervain's thyroiditis, or granulomatous thyroiditis due to Koch's [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

(a) Microphotograph showing Hashimoto's thyroiditis with thyroid follicular cells showing Hurthle cell change and lymphocytes in the background, categorized into the benign category (Pap, ×400), (b) Microphotograph of a smear categorized as AFLUS, showing predominantly benign thyroid follicular cells in sheets, with some cells showing anisonucleosis and forming microfollicles (Pap, ×400)

Atypia of undetermined significance/atypical follicular lesion of undetermined significance

As per the guidelines of the Bethesda System, aspirates which were considered adequate, had some features of atypia but could not be categorized definitely into either of the benign, SFN, SM, or malignancy categories were grouped under this category.[9] For example, a smear that showed cytological features of high cellularity, tiny follicular cells arranged in sheets, clusters or singly, with occasional occurrence of multinucleated giant cells, and focal occurrence of Hurthle cells was described as AFLUS [Figure 1b].

Follicular neoplasm/suspicious for follicular neoplasm

Aspirates with cytomorphologic features of moderate to high cellularity, scant or absent colloid, with predominantly microfollicular or trabecular configuration of follicular cells in repetitive pattern were grouped under this category. Aspirates with cytomorphologic features of Hurthle cell neoplasm were also placed in this category.

Suspicious for malignancy

Aspirates that had cytological features suggestive of, but not definitive of, papillary carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, or lymphoma were placed in this category.[10] For example, an aspirate that had cytological features of high cellularity, comprised elongated oblong cells with occasional plasmacytoid appearance with some cells showing Hurthle cell change and possessed a matrix different from colloid, possibly amyloid, was classified as suspicious for medullary carcinoma.

Malignant

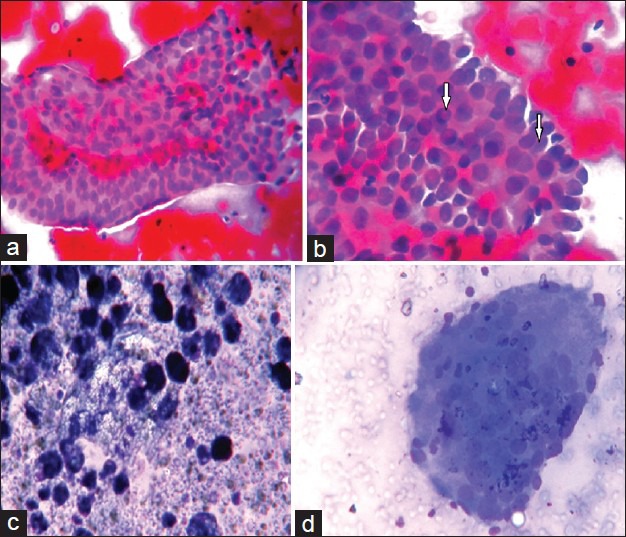

Aspirates that appeared unequivocally malignant were placed in this category [Figure 2].[11]

Figure 2.

Microphotograph of a smear categorized as papillary carcinoma. (a) Thyroid follicular cells arranged in papillae with anatomical borders (Pap, ×400), (b) Nuclear grooving and pseudoinclusion (arrow) (Pap ×400), (c) Cyst macrophages in the background (LG, ×400), (d) Multinucleated giant cells (LG ×400)

Follow-up histology

We could pursue follow-up histology for 323 cases. We compared the diagnoses offered in FNAC in the light of the Bethesda system, with the diagnoses obtained on final histopathologic examination (HPE), for these 323 cases. Thereby, we could calculate the malignancy risk for each category and compared it with that in other studies. Incidental papillary carcinomas (<1 cm) on resection were not considered malignant, except when prior cytologic interpretation was SM or malignant.

Results

Of the 1020 cases who underwent FNAC during the period from April 2009 to March 2012, initially, 69 cases (6.8%) turned out to be non-diagnostic, 847 (83%) benign, 9 (0.9%) AFLUS, 42 (4.1%) SFN, 14 (1.4%) SM, and 39 (3.8%) malignant. Also, 69 cases who were initially non-diagnostic, were re-aspirated, out of which, 39 cases were re-aspirated under ultrasound guidance.[12]

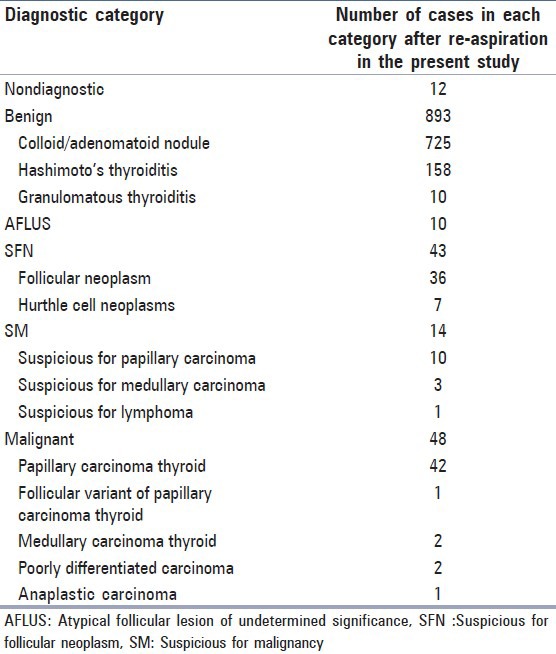

After re-aspiration, 12 cases (1.2%) out of 1020 patients remained non-diagnostic. The distribution of cases in the other Bethesda categories following re-aspiration were benign 893 cases (87.5%), AFLUS 10 cases (1%), SFN 43 cases (4.2%) including 7 Hurthle cell types, SM 14 cases (1.4%), and malignancy 48 cases (4.7%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of cases in the Bethesda categories as per our study (n=1020)

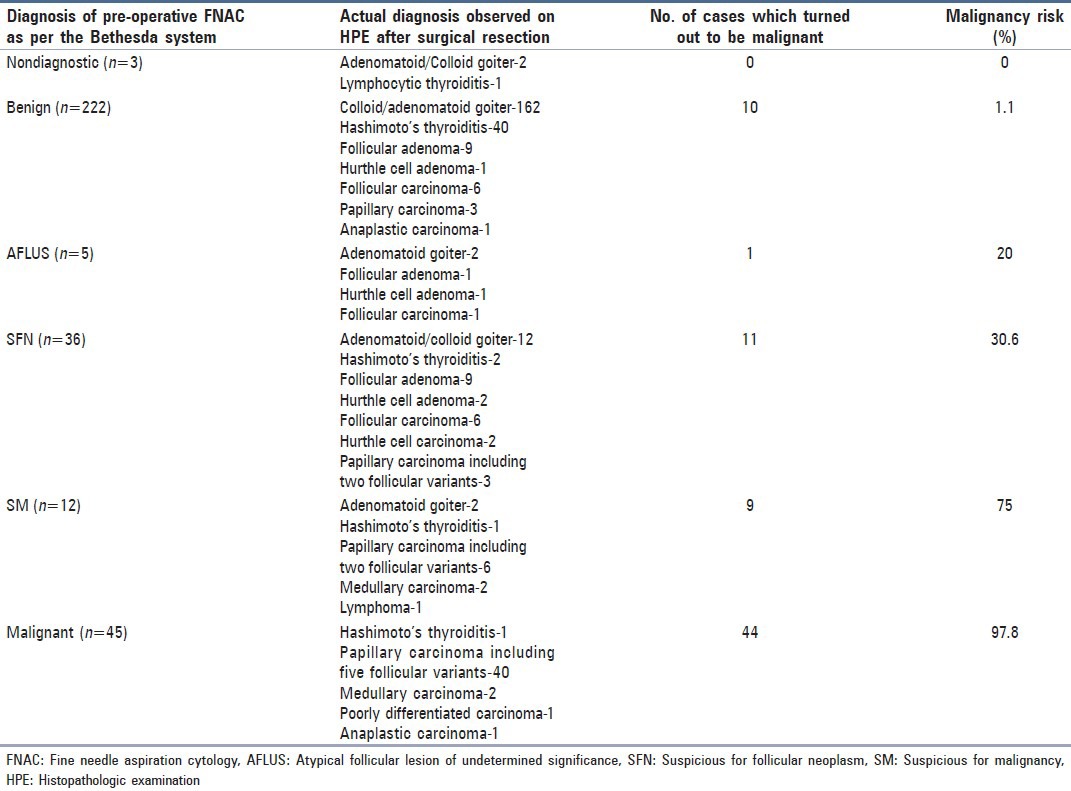

Out of 1020 cases, 323 cases were available for follow-up histopathology. Out of these 323 cases, 3 cases had original FNA diagnoses as non-diagnostic, 222 cases as benign, 5 cases as AFLUS, 36 cases as SFN, 12 cases as SM, and 45 cases as malignant. We compared the original FNA diagnoses of these 323 cases with the diagnoses obtained on HPE and calculated the malignancy risk for each category [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of pre-operative FNAC diagnoses with the diagnoses on HPE after surgical resection, and calculation of malignancy risk for each Bethesda category

Accordingly, none of the three cases who had original FNA diagnoses as non-diagnostic were reported to be malignant on follow-up HPE. Thus, the malignancy risk for this category was 0%.

Out of the 893 benign cases, specimens of 222 cases were available for follow-up HPE, among which, 10 cases were found to be malignant. So the malignancy risk in the benign category in this study was 4.5%.

Five out of the 10 cases reported as AFLUS could be followed-up for HPE. One was found to be malignant, giving a malignancy risk of 20% in this category.

Thirty-six out of the 43 cases of SFN were available for HPE; 11 out of which were found to be malignant, giving a malignancy risk of 30.6% in this category.

Nine out of the 12 surgically resected cases of SM were found to be malignant by HPE in the follow-up period, giving a malignancy risk of 75% in this category.

Forty-five out of the 48 patients in the malignancy category were available for HPE and 44 cases turned out to be actually malignant, giving a malignancy risk of 97.8% in this category.

Discussion

While reviewing the FNACs in our study, it was noted that many of the descriptions and diagnoses that were offered previously seemed like a vague and complicated jargon of pathological terminologies, which would be confusing and of no clinical significance to the clinicians.[2] However, when we recorded the diagnoses as per the criteria laid down in the standardized nomenclature of the Bethesda system, it seemed more simplified, systematic, with greater clarity; thus, it would prove to be more useful in guiding clinicians towards the management of thyroid nodules.[13]

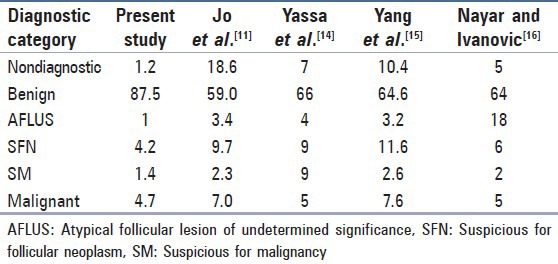

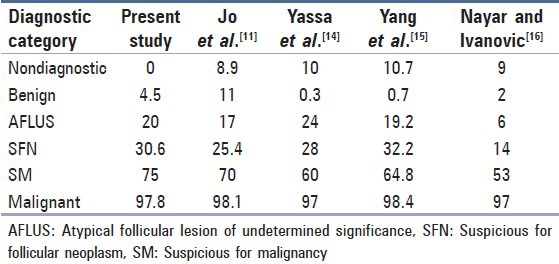

We compared the results obtained in our study with the studies of Jo et al.,[11] Yassa et al.,[14] Yang et al.,[15] and Nayar and Ivanovic[16] [Tables 3 and 4].

Table 3.

Comparison of the percentages of distribution of fine needle aspiration diagnoses of present study with other studies

Table 4.

Comparison of the percentages of follow-up malignancy of present study with other studies

It was seen that the distribution of cases as per the six-tier Bethesda system in our study differed from that in the above mentioned studies, with the percentage of cases in the benign category being higher and that in the non-diagnostic and AFLUS categories being lower.

The reason for the number of cases in the benign category being higher can be attributed to the fact that, our institute, despite being a tertiary care centre, not only caters to the needs of patients on a referral basis, but also patients come here directly without referral. So a large population, representative of the general population, is encountered in our institute. Therefore, the proportion of benign cases that is a lot higher in the general population, is reflected proportionately in our study. According to Jo et al.[11] most of the above mentioned studies have been done in tertiary care centers, where patients come only on a referral basis and, hence, is not exactly representative of the general population. A second reason for our institute serving a large representative population is the fact that the procedure of FNAC is easily accessible to the economically backward sections of the society for whom the test can be performed free of cost.

The reason for the lower percentage in the non-diagnostic and AFLUS categories can be attributed to the fact that, in our institute, usually an ultrasound-guided FNAC is performed for small nodules or nodules that appear heterogeneous on palpation, so that the aspirate can be procured from the exact pathological site.[12,17] Another important point is that, as the cytopathologist himself performs the procedure of FNAC in our institute, a better quality and adequate aspirate can be ensured. These probably have led to a reduction in the non-diagnostic or indeterminate diagnoses, thereby allowing a more specific cytological diagnosis.

The malignancy risk for the different categories in our study, as seen by follow-up HPE, has corroborated well with the implied risks mentioned in the Bethesda System and also with the studies of Jo et al.,[11] Yassa et al.,[14] Yang et al.,[15] and Nayar and Ivanovic[16] though few differences have been noted. First of all, the malignancy risk for the non-diagnostic category is 0% as compared to the higher rates in the other studies. Secondly, the malignancy risk for the AFLUS category is 20% as compared to 6% in the study of Nayar and Ivanovic.[16] Both findings can be explained by the fact that, in our study, we have a smaller denominator population for the non-diagnostic and AFLUS categories, as a result of which the malignancy risk of the non-diagnostic category with other studies and malignancy risk of the AFLUS category with the study of Nayar and Ivanovic[16] cannot be accurately compared.

As we were doing a retrospective study, clinical, biochemical, and radiological correlation was not available for few cases, due to which we faced a slight difficulty in categorizing those aspirates. This is one of the limitations in our study. Secondly, few slides, especially those older than two years, had a faded quality of staining, which even after re-staining did not gain the quality of a freshly stained smear and was thus found difficult to report.

Conclusions

The Bethesda system is very useful for a standardized system of reporting thyroid cytopathology, improving communication between cytopathologists and clinicians, and inter-laboratory agreement, leading to more consistent management approaches.[18] The high malignancy risk for the AFLUS, SM, and malignancy categories reflects the importance of these categories in the six-tier Bethesda system.

However, a prospective study over a larger population would lend more insight into the merits and demerits of the proposed system.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Cibas ES. Fine-needle aspiration in the work-up of thyroid nodules. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43:257–71. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redman R, Yoder BJ, Massoll NA. Perceptions of diagnostic terminology and cytopathologic reporting of fine-needle aspiration biopsies of thyroid nodules: A survey of clinicians and pathologists. Thyroid. 2006;16:1003–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis CM, Chang KP, Pitman M, Faquin WC, Randolph GW. Thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsy: Variability in reporting. Thyroid. 2009;19:717–23. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guidelines of the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology for fine-needle aspiration procedure and reporting. The Papanicolaou society of cytopathology task force on standards of practice. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;17:239–47. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199710)17:4<239::aid-dc1>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, Kloos RT, Lee SL, Mandel SJ, et al. Management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2006;16:109–42. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baloch ZW, LiVolsi VA, Asa SL, Rosai J, Merino MJ, Randolph G, et al. Diagnostic terminology and morphologic criteria for cytologic diagnosis of thyroid lesions: A synopsis of the national cancer institute thyroid fine-needle aspiration state of the science conference. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:425–37. doi: 10.1002/dc.20830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:658–65. doi: 10.1309/AJCPPHLWMI3JV4LA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schinstine M. A brief description of the Bethesda system for reporting thyroid fine needle aspirates. Hawaii Med J. 2010;69:176–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Layfield LJ, Morton MJ, Cramer HM, Hirschowitz S. Implications of the proposed thyroid fine-needle aspiration category of “follicular lesion of undetermined significance”: A five-year multi-institutional analysis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:710–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.21093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung YS, Yoo C, Jung JH, Choi HJ, Suh YJ. Review of atypical cytology of thyroid nodule according to the Bethesda system and its beneficial effect in the surgical treatment of papillary carcinoma. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81:75–84. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2011.81.2.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jo VY, Stelow EB, Dustin SM, Hanley KZ. Malignancy risk for fine-needle aspiration of thyroid lesions according to the Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:450–6. doi: 10.1309/AJCP5N4MTHPAFXFB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MJ, Kim EK, Park SI, Kim BM, Kwak JY, Kim SJ, et al. US-guided fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: Indications, techniques, results. Radiographics. 2008;28:1869–86. doi: 10.1148/rg.287085033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richmond BK, O’Brien BA, Mangano W, Thompson S, Kemper S. The impact of implementation of the bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology on the surgical treatment of thyroid nodules. Am Surg. 2012;78:706–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yassa L, Cibas ES, Benson CB, Frates MC, Doubilet PM, Gawande AA, et al. Long-term assessment of a multidisciplinary approach to thyroid nodule diagnostic evaluation. Cancer. 2007;111:508–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang J, Schnadig V, Logrono R, Wasserman PG. Fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: A study of 4703 patients with histologic and clinical correlations. Cancer. 2007;111:306–15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nayar R, Ivanovic M. The indeterminate thyroid fine-needle aspiration: Experience from an academic center using terminology similar to that proposed in the 2007 national cancer institute thyroid fine needle aspiration state of the science conference. Cancer. 2009;117:195–202. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miseikyte-Kaubriene E, Ulys A, Trakymas M. The frequency of malignant disease in cytological group of suspected cancer (ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of nonpalpable thyroid nodules) Medicina (Kaunas) 2008;44:189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozluk Y, Pehlivan E, Gulluoglu MG, Poyanli A, Salmaslioglu A, Colak N, et al. The use of the Bethesda terminology in thyroid fine-needle aspiration results in a lower rate of surgery for nonmalignant nodules: A report from a reference center in Turkey. Int J Surg Pathol. 2011;19:761–71. doi: 10.1177/1066896911415667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]